Abstract

This article investigates the situation of Swedish upper secondary school students who have been subject to distance education during the COVID‐19 pandemic crisis. We understand the transition from onsite education to distance education as a recontextualization of pedagogical practice, our framing follows loosely concepts from Bernstein. Given that the field of upper secondary education is highly socially structured it is relevant to enquire into the social dimensions of distance education. For this purpose, we have analysed answers to an open‐ended question in a survey answered by 3,726 students, and related them to a cluster analysis distinguishing three main clusters of students: urban upper‐middle‐class, immigrant working‐class, and rural working‐class. The urban upper‐middle‐class students experienced problems decoding new requirements and were troubled by blurred boundaries between school and home. This group invests the most in schooling, and therefore expresses comparatively more anxiety for reaching anticipated achievements. Immigrant working‐class students were comparatively more discontented by a lack of school support and request clearer instructions. In this new educational situation, characterized by a weak framing, they have difficulties decoding the requirements. The rural working‐class students appear comparatively more disconnected from the school situation. Unlike urban upper‐middle‐class students, for whom the school invades the home and private sphere, the rural working‐class students seldom experienced that the school intruded their home; accordingly, their studies collapsed into sleep‐in‐mornings and a holiday feeling.

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. A divergent case in a divergent country

In March 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared that the world was facing a COVID‐19 disease pandemic. The situation was by then no longer merely local but global. Several countries introduced severe restrictions. Lockdown became the common term for societies shut down with closed workplaces, shops, schools, restaurants, cafés, pubs, gyms, etc. During this first wave of the pandemic, however, Sweden adopted a different strategy. Shopping malls, shops, restaurants and cafés were kept open, but with recommendations to keep distance. Preschools, primary and lower secondary schools also stayed open, but with strict orders for everyone to stay at home at the slightest symptoms of illness. The Swedish coronavirus strategy was thus mainly based on recommendations. Your own responsibility, keep your distance and stay at home if you are ill, were recurring slogans. In addition to general recommendations, travel abroad was halted since many countries closed their borders, and travel within the country was severely restricted. Everyone who could was recommended to work from home. However, the heaviest restrictions were placed on the younger part of the population: upper secondary schools and higher education institutions were obliged to move to distance education (Bergdahl & Nouri, 2021; Bettinger et al., 2017; Olofsson et al., 2020; Skolinspektionen, 2020). This article focuses on the experience of upper secondary students in this context.

Other Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway) introduced stricter restrictions than Sweden. Norway, Denmark and Finland were resorting to regional shutdowns where the spread of infection was particularly strong. Overall, during the course of the pandemic, the Swedish coronavirus strategy has deviated in relation not only to the Nordic, but also to other European countries. These differences were especially clear in the spring of 2020. One reason for this initially different Swedish strategy was that the Swedish expert agency that supported the government with information, analyses and recommendations—the Public Health Agency of Sweden (Folkhälsomyndigheten, FHM)—was guided by the conviction that in combatting the virus, trust was more efficient than threats and legal regulations. To appeal to people's judgment, sense of responsibility and solidarity was considered as a more long‐lasting strategy.

While most of Sweden stayed open, upper secondary schools and universities closed. For just over a year, from March 2020 to at least May 2021, all upper secondary education was to be carried out mostly as distance education. In March 2020, suddenly and without preparation, all of Sweden's upper secondary schools were urged to switch to distance education. Even though digital tools have long been used in teaching and homework, almost all courses and their elements, both in higher education and in university preparing and vocational upper secondary school programmes, were now to be carried out as distance education. Teachers as well as students had to adapt quickly to digital teaching. Thereby, upper secondary students in Sweden became a divergent case in a divergent country.

The role of upper secondary education in the Swedish education system is contradictory. Even if completion of upper secondary education has become quasi‐mandatory for entering the labour market, as a form of study it is voluntary. No sanctions affect the student who does not follow the proposed curriculum or meet the expectations of attendance. Theoretically, upper secondary education is based on individual responsibility, as is following a course in distance education. This has led to questions such as: How should everyone be persuaded and able to transform the home into a school? Not just to physically arrange space for peaceful study, but in order for shared school experiences to take place in the private sphere? Devices such as computers, Ipads, and even smartphones—otherwise personal connections to social media—are now suddenly and unexpectedly used for instructions from teachers and for testing. Most studies show that distance education has been a problem for many, especially less school‐motivated students who have had difficulties in finding study motivation (Fitzpatrick et al., 2020; Engzell et al., 2021; Henning Loeb & Windsor, 2020; Sjögren, 2021). This is explained not only in practical terms—by the lack of digital tools, a functioning internet connection, etc.—but also by difficulties experienced in the actual change from school to home.

In this article we use students' answers to an open‐ended question about their situation during the pandemic to understand the components and variations in experiences. Furthermore, we strive to better understand the diverse critique in relation to the social differences among the students and their education programmes. The aim of the article can thus be summarised as to increase our understanding of the situation of upper secondary students in Sweden, who have been subject to distance education for a long time during the COVID‐19 pandemic crisis.

2. THEORETICAL POINTS OF DEPARTURE

2.1. Framing, educational space and capital

In this article, we combine two theoretical approaches that are complementary, and which can support an understanding of the specific situation that distance education has created. In order to understand the abrupt and radical shift in teaching and learning that the shift from school to home created, we draw on the work of the British sociologist and education researcher Basil Bernstein and his concept of framing. Our analysis highlights the importance of the strength or weakness in the demarcation between different tasks, and in the extension between different kinds of activities, lessons, breaks, etc. In the now classic article On the Classification and Framing of Educational Knowledge, Bernstein develops the definitions of visible and invisible pedagogy, which are especially relevant for our material. In a pedagogical practice characterised by strong classification and framing, where things must be kept apart, there is a clear demarcation between people, actions, things and communication. The pedagogy is visible. When the opposite prevails, in the invisible pedagogy, where things must be put together, the demarcation between people, actions, etc. is weakened (Bernstein, 1971). The transition from on‐site to distance education can be described as a change from a previously strong(‐er) framing to a weak(‐er) one and where the ability to read the classification becomes crucial. According to Bernstein, the students' successes or failures fall back on their ability to interpret the underlying code, the task, the purpose, etc.; that is, to decode the grammar in the school's classification (Bernstein, 1996).

In order to account for how the shift to distance learning relates to the social structure of upper secondary education, we rely on the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu's notions of field, space and capital, where the first two denote a structured conception of the social world, with hierarchies, oppositions and polarities, and the latter denotes assets of different sorts that are recognised as valuable within certain fields or spaces, and which form the basis for the structures of these fields or spaces (Bourdieu, 1989). The notions of space and distribution of capitals within the space, form the framework for the design of the investigation and the analysis of the open‐ended question for student reflections on distance education.

3. INCREASING SOCIAL INEQUALITY IN UPPER SECONDARY SCHOOLS

There is a tension within the Swedish education system, arguably most visible in upper secondary school. Social equality is stressed on a policy level but the marketization of the Swedish education system since the 1990s has increased social differences. This is especially apparent in the upper secondary segment, where differences have increased both between schools and between study programmes (Forsberg, 2018; Lundahl, 2016).

We have in a series of studies analysed Swedish upper secondary education as an educational field, based on the distribution of students of different social origin and gender, over national programmes and orientations (Börjesson et al., 2016; Forsberg, 2018; Lidegran et al., 2019). Our results show that the students' choice of programme and orientation is clearly linked to the social position of the parents and the students' gender. The field has a triangular structure where gender differences are most pronounced in the working‐class and least visible among upper‐middle‐class students. The Natural Science Programme has the most socially exclusive position in the top of the triangle and gathers the most resource‐rich girls and boys as students. Other study programmes such as the Social Science Programme and the Business Management and Economics Programme recruit students from the middle‐class and are placed in the middle of the triangle. The vocational programmes are found in the base of the triangle, where the working‐class daughters and sons choose very different vocational programmes. This general pattern has been very stable over the years and has even been reinforced further since the latest reform in 2011. Given the current situation, it is interesting and relevant to pose questions such as: How do students in different social positions in the field of upper secondary school experience the change to distance education and the fact that they are not allowed to go to school? Does it strengthen or weaken social differences?

4. METHODS AND DATA

The results are based on the analysis of a survey sent out to Swedish upper secondary students concerning distance education during the COVID‐19 pandemic in 2020. In a previous study, a social space of upper secondary students was constructed drawing on a survey with 3,726 respondents and the following ten variables: Highest education of parents; Immigrant background; Family situation; Number of siblings; Geographic origin; House type; Number of books at home; Visits to the library during lockdown; Books read in the last three months and Study programme divided by gender (Lidegran et al., in press). We have now used the social space we constructed to perform a hierarchical cluster analysis (using the Wards' method, see Le Roux & Rouanet, 2004, pp. 106–107) and the clusters obtained were used to analyse the answers to an open‐ended question in the survey. The aim of the cluster analysis was to obtain groups of individuals that are as internally homogeneous as possible, and as heterogeneous as possible between clusters. Since the clustering is based on a multiple correspondence analysis, the clustering is based on the coordinates of the individuals in the social space, which in turn are based on the students' responses to questions (the ten active variables in the analysis).

The opportunity to provide an answer to the open‐ended question, placed at the end of the survey, is rarely given much attention by respondents. However, in this case almost 1,700 of the students replied (ca. 46%) and out of those 1,519 were, after a read‐through, deemed as relating to the question of studying from home and therefore included in the analysis. We made a qualitative content analysis, and systematically compared the answers to the open questions in relation to the three clusters.

5. THREE CLUSTERS OF STUDENTS

Our upper secondary school survey was conducted in the spring of 2020, during the first wave of COVID‐19 in Sweden. The upper secondary students had had distance learning for about three months. By then, no one knew that the pandemic would last for many months to come. In the light of this, it is worth noting that already after three months, the overall experience of distance learning was negative and fraught with a feeling of dissatisfaction and problems among the students. However, there were differences between student groups. We have sought to deepen our understanding of how the students perceived their situation, and how this can be understood in relation to their objective conditions and their study programmes.

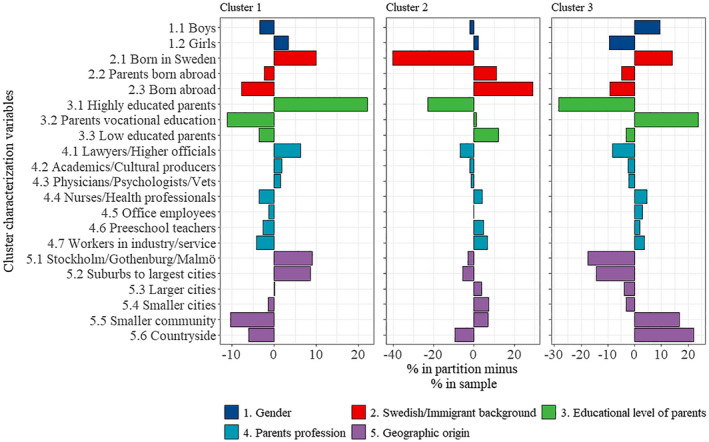

We performed a cluster analysis of student responses based on their positions in the social space of conditions and experiences among Swedish upper secondary students during COVID‐19 distance education. This made it possible to link open‐ended responses from students to their position in the social space and include ten active variables for distinguishing groups of students (Le Roux & Rouanet, 2010). Three clusters have been considered. Cluster 1 consists of 2,005 students, Cluster 2 of 824 and Cluster 3 of 897. To obtain a better understanding of the three student clusters, we characterise them by socio‐demographic variables (Figure 1). The plus side shows that there is an over‐representation in each cluster in comparison with the entire survey population, and the minus side that there is an under‐representation.

FIGURE 1.

Descriptions of the three clusters of students, over‐ and under‐representation. Source: Authors' survey [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

As Figure 1 illustrates, Cluster 1 is characterised by an over‐representation of students who have parents with a high level of education, and who are working in upper‐middle‐class occupations such as lawyers, higher officials, academics, cultural producers and physicians; who were born in Sweden; are girls; and live in large cities. We have chosen to name the cluster Urban upper‐middle‐class students. Cluster 2 is characterised by an over‐representation of students who were born abroad, have parents who were born abroad, have a low level of education, and work in working‐class and lower‐middle‐class service occupations. Based on these characteristics, we have chosen to name this cluster Immigrant working‐class students. Cluster 3 is characterised by students who comparatively often have parents who have completed a vocational upper secondary education, and work in working‐class and lower‐middle‐class occupations, live in the countryside, attend vocational upper secondary programmes, and are boys. We have named this cluster Rural working‐class students.

In the following, we analyse student responses to the open‐ended question where they were given the opportunity to freely describe their situations during distance education. As mentioned, approximately 1,700 of the students responded—roughly 45%. Within the Urban upper‐middle‐class student cluster 47% answered the open‐ended question, within the Immigrant working‐class student cluster 39%, and within the Rural working‐class student cluster 46 percent.

6. URBAN UPPER‐MIDDLE‐CLASS STUDENTS EXPERIENCES WERE MARKED BY INSECURITY

Urban upper‐middle‐class students have a large amount of inherited educational capital, and they predominantly attend study programmes, which also indicates extensive acquired educational capital. These educational resources manifested in long and elaborate responses to the open‐ended question. Students highlight both the pros and the cons of studying at home, although the disadvantages in most cases weigh heaviest. There are also several examples of students seeing the situation from different perspectives, and reflecting beyond their own situations, as in the following example. “Many times, the teachers are forgotten. For sure, they get paid, but the situation has required much more of them than we/they could have anticipated” (survey response, Student, Social Science Programme, Sweden, 2020). In several cases, they related their situation to other students who have worse conditions for coping with distance education, and they see the consequences of distance education from both an individual and a societal perspective. “Society has not had time to think of all students and many see the school as their only security. Some upper secondary school students have bad family relationships and then maybe the school is the only relief that many students have” (survey response, Student, Social Science Programme, Sweden, 2020). Or, as another student put it: “And I think those who are already having a hard time in school get it even worse now, while for those for whom it is going well it continues to work fine” (survey response, Student, Natural Science Programme, Sweden, 2020).

However, responses in this cluster were characterised by a frustration over a perceived increase in requirements, that many more tasks have been added, and that assessments and tests are not as easy to decode in relation to knowledge requirements and grades. Many students expressed that they were getting too many and too difficult tasks. We understand this pedagogic situation as invisible—students had difficulties to decode and find out the borders between different tasks. The severity or scope of the requirements was not adjusted for the time allotted. Time is central to students' assessments of their situation and is understood by them in relation to their ability to achieve good grades.

It has been a bit complicated handling tests in different subjects and I get a little worried that certain parts of the teaching will not be carried out, which means that the teachers do not have all the material they need to set correct grades. (survey response, Student, Social Science Programme, Sweden, 2020)

The problem with the assessment of performance in distance education is presented in the answers in various ways. Students felt that the assessment of performance took place on unclear grounds, that tests were difficult to carry out at home (a concern that certain students were cheating was also expressed), and that the examinations are generally more difficult to carry out both technically and in terms of content because the teaching is not adapted sufficiently. The students expressed a sense of injustice in being graded on a looser basis, and with ambiguities about how the difficult circumstances were taken into consideration. “In addition, you do not know how important each task is. If there is only one thing to do in the lesson or if it is judged [graded]” (survey response, Student, Business Management and Economics Programme, Sweden, 2020). Particularly upset were those in their final year of upper secondary school who risked not getting into the higher education programmes they wanted due to insufficient grades. It is to the assessment of performance—above all—that the increased stress and poorer mood was ascribed: “Distance education has led to increased mental illness, unmotivated school days […], and an over‐abundance of information” (survey response, Student, Business Management and Economics Programme, Sweden, 2020). In some cases, students considered dropping out of school if distance education did not cease, as the pressure to cope with its demands were felt to be too heavy.

6.1. “A thousand times more work just because we are at home”

Within the cluster of Urban upper‐middle‐class students, reflections on the transition to distance education are rich in content, and they deliver precise descriptions of what works and what does not. The students were especially dissatisfied with the teachers' inability to recontextualise the school's pedagogical practice into a functioning distance learning system. Their dissatisfaction was chiefly about teachers' shortcomings in terms of technical competence, which reflects negatively on their ability to give meaningful lectures, assignments, instruction and feedback. The students were also concerned about differences between subjects. Practical subjects such as sports and music were perceived as particularly difficult to transfer to distance education, but some theoretical subjects such as mathematics and physics also involved greater difficulties compared with other subjects. Students suspected that they received assignments only because the teachers wanted to make sure that they were studying at home. The status of the teaching content was unclear to the students and they doubted that it formed the basis for assessment. As teamwork and more oral elements in teaching almost disappeared, most assignments involved handing in written text. For many students, the amount of written assignments constantly required in all subjects became a great burden. A student condemned distance education as useless. “In school we got everything served… and easily got answers to questions” (survey response, Student, Business Management and Economics Programme, Sweden, 2020). She had a hard time getting things in order, adjusting the time, dealing with the demands of solving many tasks at the same time all alone. Another student described:

I get up at 7:00 and go to bed at 23:00, otherwise I do not have time for what needs to be done. I get several tasks on the same subject, which makes it difficult to have time to perform at the level you want. (survey response, Student, Business Management and Economics Programme, Sweden, 2020)

Students in this cluster also considered that even if one manages the studies, the quality of teaching has deteriorated as a result of distance education.

6.2. “I cannot distinguish between school and leisure time”

A recurring problem in the student responses related to time. The days become blurred and indistinguishable. It is also difficult to see the difference between school and leisure. Boundaries between how devices such as computer, Ipad and mobile phones are used for schoolwork and leisure activities become fluid.

Studying at home has become difficult now because you cannot distinguish between school time or leisure time. It is also hurting the body because we sit/lie in front of the computer when it is school time but we also do that in our free time when we watch comics, movies, etc. (survey response, Student, Natural Science Programme, Sweden, 2020)

Being constantly reminded of tasks to be done at home is too stressful for many and there were a large number of complaints about the stress that arises when the school is constantly present in the home. Responses indicate that it becomes more difficult over time:

I feel that at first, I had very good discipline with the school and the tasks, but over time it has gotten worse. For me, there is no longer any major difference between private life and schoolwork because the environment is the same all the time and if you have not had time to finish school during the day, it will be part of the evenings and weekends as well. (survey response, Student, Business Management and Economics Programme, Sweden, 2020)

With distance education, schoolwork has pushed private life out of the home. Schoolwork is expanding its territory, which means that the home is less and less associated with leisure time and more and more related to schooling. The difficulties within this cluster with separating schoolwork from leisure must be considered in relation to the fact that this is a group of students who in ordinary times have been used to studying at home, since they attend programmes in which homework is a natural element. Many of them have set their sights on high grades and hope to attend university studies at prestigious programmes in the future (Lidegran, 2017). In the transition to distance education, there is a risk that the habit of studying at home will result in schoolwork easily expanding in time and space and displacing everyday life. At the same time, studying at home is understood as requiring self‐discipline and the need for establishing sustainable routines, and the ability to work at home efficiently, productively and in a concentrated way is important in the evaluation of whether studying at home works well or poorly. Clearly, students who have a habit of working at home have an advantage over other students when all teaching is transferred to distance education (Delès, 2021).

6.3. “It's hard not to be able to get help from your friends as easily as before”

The importance of the school as a social environment is clear in the student responses. The students missed their normal context: friends, teachers, the structure of the school day. They were eager to describe this situation. Recurring features are feelings of loneliness, and the difficulty of maintaining motivation. The students in the cluster Urban upper‐middle‐class students often say that they still manage the studies themselves okay but that they missed the social contact with classmates. A distinctive feature of this student cluster is that it also links the social interaction with friends to learning and school assignments: “The disadvantages are precisely the social part. I miss sitting with my classmates and discussing, helping each other and studying together” (survey response, Student, Natural Science Programme, Sweden, 2020). It is not only the social activity in general that they missed, but also an interaction with friends linked to their studies and learning, and to the social: that is, meeting and studying together.

7. IMMIGRANT WORKING‐CLASS STUDENTS LACKED SUPPORT FROM SCHOOL

The Immigrant working‐class student cluster is characterised by poorer circumstances for distance education. Their households are crowded, the students have little private physical space and the technical equipment is inferior. They spend less time at home and choose other places to study to a greater extent than others (Lidegran et al., in press). Their personal responsibility is linked to finding a reasonable work environment outside the school, environment and is often expressed as a lack of support from the teachers, which must be understood in relation to the fact that they do not have the same support at home as the students in the urban upper‐middle‐class cluster. (“It is bad for those who have too slow internet. I often have to go to friends to study”—Student, Social Science Programme, Sweden, 2020).

7.1. “Teachers should motivate one more—Help one to get the motivation up”

Many students in this cluster attended programmes that prepare students for higher education, which in fact require graduating with grades that allow them to enter a university education. The students testified to a challenging situation where it is difficult for them to study at home, they risk lower grades, and the road to a future higher education thereby can be blocked. The transition to distance education has in many cases led to students losing motivation, and wishing that there was more support from teachers to cope with the situation. “It is very stressful because you have to take responsibility for your studies and it is also difficult to get help from teachers online, which makes it more difficult to understand certain subjects” (survey response, Student, Natural Science Programme, Sweden, 2020). Several students testified that they lacked support for their learning, and that they feel left alone with the full responsibility for their schoolwork. “[it is] much more difficult to learn without teachers nearby and without someone who lectures on the subject” (survey response, Student, Natural Science Programme, Sweden, 2020). “All guidance disappears and teaching is minimized, and there is far too much responsibility put on the student” (survey response, Student, Electricity and Energy Programme, Sweden, 2020).

Some schools have opened up for groups of students to come to school on certain days:

Studying at home does not work at all. That is why I now go to school three days a week and try to participate in the lessons […]. It helped a lot to sit in a school environment even if the teachers are not there. (survey response, Student, Natural Science Programme, Sweden, 2020)

The school environment itself stands for security by creating a framework for help and support, even when the teachers are not there. The difficulties of studying at home often lead to a plea that you want to go back to school as soon as possible, since that is the only place where you can get help in your studies. “It is very difficult to study from home, I cannot get direct help and would very much like to go back to school!” (survey response, Student, Social Science Programme, Sweden, 2020). Separating the home from the school is an important basic prerequisite for Immigrant working‐class students, and when this opportunity is severely limited, the students feel that they are left alone in their situation, and that they lack proper support.

7.2. “Grades drop, future plans and goals are gone”

In many cases, the home does not work well as a study environment for the students. This in combination with the fact that they expressed that they need more support in everything from finding motivation to coping with the tasks and the studies as a whole, produces a stress which is further accentuated by the fact that their grades drop. The frustration of not being able to keep their grades is apparent.

The country should just have ended primary and secondary education and given us all a pass on all our courses, the grades may be based on performance in the previous months. Take a hold of this and solve it, we're all tired. (survey response, Student, Technology Programme, Sweden, 2020)

Poorer grades mean poorer opportunities to get into a university, where many attractive programmes require high grades from upper secondary school. Many students stated that the situation has not worked and the grades have gotten worse. Two examples: “I do not like distance education at all as it affects my grades drastically negatively” (survey response, Student, Electricity and Energy Programme Sweden, 2020), and “Very bad! All my grades have been lowered, want to go back to school NOW” (survey response, Student, Natural Science Programme, Sweden, 2020). Students also expressed a desolate view of their future, showing an awareness that not being able to study efficiently at home will have far‐reaching consequences. They have no plan for the future, they have no aces up their sleeves to pick out.

This period has been the worst in my life. Open upper secondary schools if you do not want the mental illness to increase significantly among teenagers in upper secondary school. Otherwise, this will have devastating consequences that we will not be able to retract. For the future! (survey response, Student, Arts Programme, Sweden, 2020)

To conclude, for this group of students the individual responsibility has become especially troublesome since the conditions for distance education are strikingly poor, together with the students' high ambitions and stakes, leaving them to struggle on their own, managing a future where they risk being without sufficient qualifications from upper secondary school in order to enter desired tracks.

8. RURAL WORKING‐CLASS STUDENTS EXPRESS NEGATIVE FEELINGS OVERALL

Within the cluster Rural working‐class students (where especially boys who attend vocational programmes are over‐represented), the situation at home during distance education was not discussed in relation to school performance in the same way as in the cases of the other two student clusters. Many students in this cluster attend vocational programmes that in practice prepare them for jobs immediately after upper secondary school. This applies in particular to programmes with predominantly boys and means that the students are not as dependent of school assessments as students in the other two clusters. A greater independence from school appears, in the open‐ended responses, in a frequent decoupling of school and the social part of school—meaning that students above all lacked the company of friends.

8.1. “Can't take it anymore”, “nice” and “boring”

In contrast to responses from the two other clusters, three different students in the working‐class cluster expressed in general terms the situation by expressions such as “I can't take it anymore”; “nice”; and “boring”. The answers to the open‐ended question were often quite concise and contained emotionally charged words such as, “[I] want to die” (survey response, Student, Electricity and Energy Programme, Sweden, 2020) and “Shit, go to hell” (survey response, Student, Industrial Technology Programme, Sweden, 2020). The situation is described as a general feeling and fewer references to the school situation were made compared to the other two clusters. Frequently a broad description of the situation that lacked precision or connection to specific situations was articulated. The situation was summed up as “Very sad” (survey response, Student, Natural Resource Use Programme, Sweden, 2020) and feeling restless: “[I] hope the shit is over by the autumn because you get restless from going home all day” (survey response, Student, Electricity and Energy Programme, Sweden, 2020). Positively value‐laden words also occurred in descriptions that it was generally “nice” with longer mornings and a calmer time socially.

8.2. “It's hard to get something done”

As for the demarcation between school and leisure, it seemed that distance education in the students’ home environments resulted in leisure time pushing out school time: “It is boring to sit at home and not meet friends and it can easily happen when you are bored that you do something else” (survey response, Student, Industrial Technology Programme, Sweden, 2020). Another student described how easy it is to slip from the lesson into watching Netflix or doing other leisure activities.

It is easy to lose interest in the studies and to instead watch Youtube or Netflix or something else that seems more interesting than schoolwork, which means that you finish lessons much earlier than if you would have if you had been to school. This is because it is so easy now to just pop up a new window or tab and do what you want to do instead of what you should do if anyone would have told you. (survey response, Student, Arts Programme, Sweden, 2020)

Another student responded “It is not good to study at home as there are a lot of distractions. You often say that you will do things the next day” (survey response, Student, Technology Programme, Sweden, 2020). Many students also highlighted positive aspects of home school such as being able to sleep longer in the mornings and to avoid travel to and from school. Having the opportunity to sleep can, however, cause problems when people are tempted to sleep instead of participating in learning.

It's not good with home study, you are tired all the time and you do not have time to cook and eat the food or go out for a while during breaks to perk up. You do not have time for anything during the breaks, so you get tired day in and day out. I slept in all my lessons because I could not concentrate at all so I went back to bed and started sleeping again. (survey response, Student, Building and Construction Programme, Sweden, 2020)

The more relaxed feeling that dominates in the home can become an obstacle for schoolwork. A student says that he: “experiences that you become too relaxed when you are at home, so that it is more difficult for me to keep track of what to do, etc.” (survey response, Student, Industrial Engineering Programme, Sweden, 2020). In some cases, studies at home have turned into a feeling of an earlier summer vacation. “I think you lose your discipline now after these weeks. I think you have entered the summer holiday feeling.” (survey response, Student, Social Science Programme, Sweden, 2020). Another student also referred to the fact that it is difficult to maintain schoolwork and that leisure time is taking over. “It's a bit like having a summer vacation, the only difference is that you feel serious anxiety about schoolwork” (survey response, Student, Electricity and Energy Programme, Sweden, 2020). Rural working‐class students expressed difficulties in blocking out the free time and activities that the home usually is associated with and fully making room for school activities.

8.3. “The only thing that is fun about school, i.e., the social aspect, is gone”

The importance of school as a social environment is clear in the student responses. Above all, the students missed their friends, and they separated the social interaction from the schoolwork itself. Classmates were regarded as something else than schoolwork and the social part of education was associated with positive values. “It's hard when the only thing that is fun about school, i.e., the social, is gone. While the studies, which are the boring thing in school, are still there” (survey response, Student, Arts Programme, Sweden, 2020). As the social dimension disappears, what is seen as fun about school is lost. “Sad not to meet friends, that's what makes school fun” (survey response, Student, Social Science Programme, Sweden, 2020). Expectations for the time in upper secondary school were closely linked to getting to know new people and cultivating friendships.

I find this situation with distance education really boring and sad. You cannot meet your friends daily and you do not get the social situation in everyday life that I feel I need. I think the upper secondary school period should take place in school to meet new people. In my opinion, school does not only mean work and studying but also a safe and wonderful place to be in. I miss school very much and want to go back as soon as is possible. (survey response, Student, Technology Programme, Sweden, 2020)

Unlike for students in the other two clusters, a clear dividing line was drawn between school and what was fun and the social interaction. Not being allowed to go to school meant that the part that was perceived as stimulating and giving meaning in life was removed. What remained was studying, which does not give energy and meaning.

9. CONCLUSION

The aim of the study on which this article reports was to understand the situation for the divergent case of the upper secondary students. Specifically, students who have been subject to distance education during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Sweden—a country that has remained comparatively open during the pandemic and thereby represents a divergent COVID‐19 policy response—have been focused. We have analysed a broad range of responses and critique from upper secondary students regarding their situation, to understand its components and its variations. The research materials analysed consisted of responses to an open‐ended question in a student survey, collected in the late spring of 2020 when upper secondary schools in Sweden had been closed for three months.

The difficulties of the transition from ordinary teaching in school to home teaching and distance education can be understood with concepts from Bernstein. A pedagogical practice similar to that of distance education is described by Bernstein as an invisible pedagogy where the demarcation between content has been weakened: in this case between what is school and what is home. In other words, the school context does not always take place in a well‐defined place, but where there is space, at the kitchen table, the sofa or in some cases, in the bed. The time, the pace, the scope of tasks all change and students criticise the fact that the amount of tasks is not adapted to the lessons, the schedule, and the amount of time they have for schoolwork at home. It is thus relevant to see the framing of distance education as weakened. Students see difficulties in organising distance education on their own and figuring out a structure. They are instructed to be responsible in the task of recontextualising and strengthening the framing.

The main contribution of this article is that we show that the difficulties associated with the weakening of the demarcation of what is school and what is home, what is work time and what is leisure time, differ between various groups of students. Three different student clusters were identified through a cluster analysis: i.e., Urban upper‐middle‐class students, Immigrant working‐class students and Rural working‐class students. These three clusters occupy three different positions in a social space of circumstances and experiences among Swedish upper secondary students during COVID‐19 distance education; three clusters that hold different amounts and compositions of capital in Bourdieu's sense.

The cluster of students with large amounts of inherited resources, primarily in programmes that prepare students for higher education (Urban upper‐middle‐class students), is characterised by experiences of insecurity. Students expressed concerns that they will not be able to decode the new requirements caused by distance education, and that their efforts will not be rewarded as before. For these students, the boundary between school and home has been dissolved and the school threatens to take over more and more. In the cluster of Immigrant working‐class students we also found many who attended programmes that prepare students for higher education. These students had poorer circumstances for distance education in terms of technical equipment, support and workspace in the home. The students expressed a lack of support from teachers and from the school as an institution. They felt betrayed and did not manage to cope with their tasks without the support of the school. They were especially concerned that their grades will fall, and that their future plans will thereby be threatened and evaporate. The third cluster, Rural working‐class students, of which many attended vocational programmes, is characterised by answers to the open‐ended question that were comparatively decoupled from the school situation. Overall, students in this cluster expressed feelings about the situation comparatively often. For students in this cluster, it was difficult to get started with school assignments at home. Unlike Urban upper‐middle‐class students, for whom the school displaced the home, the school for the Rural working‐class students never took hold at home, and so their studies collapsed into sleep‐in‐mornings and a holiday feeling. These students also differentiated between school and social life; with distance education, the fun of the social dimension disappeared, while the boring school remained.

The three student clusters must be understood in relation not only to the different assets they possess and positions they hold, but also the different educational programmes and the career paths they prepare for. For Urban upper‐middle‐class students, prestigious higher education programmes that require high grades from upper secondary school are sought after, which explains the concern these students feel about not understanding or coping with the new unclear requirements and conditions for the assessment of their performance (Lidegran, 2017). For Immigrant working‐class students, the path also aims for higher education, since many of them have chosen to study upper secondary programmes that prepare students for higher education. The frustration of not getting the support they need from the school in order to be able to get a grade or a degree that allows them to pursue higher education characterises this cluster. The students in the cluster Rural working‐class students mainly attended vocational programmes that prepare for a labour market entry after completing upper secondary education. The dependence on the education system is thus weaker and the experience of distance education is characterised by a feeling that leisure time takes over for better or worse.

Our study thus shows that studies at home, which became the new normal for Swedish upper secondary students in the spring of 2020, are related to different circumstances, conceptions and content. These differences are mainly explained by student positions in the context of education, heavily dependent on students' social origin, and the different educational and vocational paths that the various positions prepare for. To turn back to the question of whether distance education has strengthened or diminished social differences, we find that differences have not diminished. Most of the students have suffered severely during the pandemic, but in different ways, and it remains an open question what the long‐term effects will be.

Lidegran, I. , Hultqvist, E. , Bertilsson, E. , & Börjesson, M. (2021). Insecurity, lack of support, and frustration: A sociological analysis of how three groups of students reflect on their distance education during the pandemic in Sweden. European Journal of Education, 56, 550–563. 10.1111/ejed.12477

REFERENCES

- Bergdahl, N. , & Nouri, J. (2021). Covid‐19 and crisis‐prompted distance education in Sweden. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 26, 443–459. 10.1007/s10758-020-09470-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, B. (1971). On classification and framing of educational knowledge. In Young M. F. D. (Ed.), Knowledge and control. New directions for the sociology of education (pp. 47–69). Collier‐Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, B. (1996). Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Bettinger, E. P. , Fox, L. , Loeb, S. , & Taylor, E. S. (2017). Virtual classrooms: How online college courses affect student success. American Economic Review, 107(9), 2855–2875. 10.1257/aer.20151193 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Börjesson, M. , Broady, D. , Dalberg, T. , & Lidegran, I. (2016). Elite education in Sweden. A contradiction in terms? In Maxwell I. C. & Aggleton P. (Eds.), Elite education—International perspectives (pp. 92–103). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. (1989). La Noblesse d’État. Grandes écoles et esprit de corps. Les Éditions de Minuit. [Google Scholar]

- Delès, R. (2021). Parents for whom school “is not that big a deal”. Parental support in home schooling during lockdown in France. European Educational Research Journal, 20(5), 684–702. 10.1177/14749041211030064 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Engzell, P. , Frey, A. , & Verhagen, M. (2021). Learning inequality during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Online article. https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/ve4z7/. 10.31219/osf.io/ve4z7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, B. R. , Berends, M. , Ferrare, J. J. , & Waddington, R. J. (2020). Virtual illusion: Comparing student achievement and teacher and classroom characteristics in online and brick‐and‐mortar charter schools. Educational Researcher, 49(3), 161–175. 10.3102/0013189X20909814 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg, H. (2018). School competition and social stratification in the deregulated upper secondary school market in Stockholm. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 39(6), 891–907. 10.1080/01425692.2018.1426441 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henning Loeb, I. , & Windsor, S. (2020). Online‐and‐alone (och ofta i sängen). Elevers berättelser om gymnasietidens sista månader våren 2020. Paideia, 20, 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Le Roux, B. , & Rouanet, H. (2004). Geometric data analysis. From correspondence analysis to structured data analysis. Kluwer. [Google Scholar]

- Le Roux, B. , & Rouanet, H. (2010). Multiple correspondence analysis. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lidegran, I. (2017). The royal road of schooling in Sweden. The relationship between the natural science programme in upper secondary school and higher education. Rassegna Italiana di Sociologica, 63(2), 419–447. 10.1423/87314 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lidegran, I. , Börjesson, M. , Broady, D. , & Bergström, Y. (2019). High‐octane educational capital. The space of study orientations of upper secondary school pupils in Uppsala. In Blasius J., Lebaron F., Le Roux B., & Schmitz A. (Eds.), Empirical investigations of social space (pp. 23–41). Springer. 10.1007/978-3-030-15387-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lidegran, I. , Hultqvist, E. , & Bertilsson, E . (in press). The space of conditions and experiences among Swedish upper secondary students during Covid‐19 distant schooling. Éducation compare. [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl, L. (2016). Equality, inclusion and marketization of Nordic education: Introductory notes. Research in Comparative & International Education, 11(1), 3–12. 10.1177/1745499916631059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson, A. D. , Fransson, G. , & Lindberg, J. O. (2020). A study of the use of digital technology and its conditions with a view to understanding what “adequate digital competence” may mean in a national policy initiative. Educational Studies, 46(6), 727–743. 10.1080/03055698.2019.1651694 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sjögren, A. (Ed.). (2021). Barn och unga under coronapandemin. Lärdomar från forskning om uppväxtmiljö, skolgång, utbildning och arbetsmarknadsinträde. Institutet för arbetsmarknads‐och utbildningspolitisk utvärdering [The Institute for Evaluation of Labour Market and Education Policy], Sweden. https://www.ifau.se/globalassets/pdf/se/2021/r‐2021‐02‐barn‐och‐unga‐under‐coronapandemin.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Skolinspektionen . (2020). Gymnasieskolors distansundervisning under covid‐19‐pandemin: Skolinspektionens centrala iakttagelser efter intervjuer med rektorer. Rapport 2020‐06‐25, Skolinspektionen [Swedish national school inspection], Sweden. https://www.skolinspektionen.se/beslut‐rapporter‐statistik/publikationer/ovriga‐publikationer/2020/gymnasieskolors‐distansundervisning‐under‐covid‐19/ [Google Scholar]