Abstract

Background

Since the first reports of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, there have been 198 million confirmed cases worldwide as of August 2021. The scientific community has joined efforts to gain knowledge of the newly emerged virus named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), the immunopathological mechanisms leading to COVID‐19, and its significance for patients with allergies and asthma.

Methods

Based on the current literature, recent advances and developments in COVID‐19 in the context of allergic diseases were reviewed.

Results and Conclusions

In this review, we discuss the prevalence of COVID‐19 in subjects with asthma, attacks of hereditary angioedema, and other allergic diseases during COVID‐19. Underlying mechanisms suggest a protective role of allergy in COVID‐19, involving eosinophilia, SARS‐CoV‐2 receptors expression, interferon responses, and other immunological events, but further studies are needed to fully understand those associations. There has been significant progress in disease evaluation and management of COVID‐19, and allergy care should continue during the COVID‐19 pandemic. The European Academy of Allergy & Clinical Immunology (EAACI) launched a series of statements and position papers providing recommendations on the organization of the allergy clinic, handling of allergen immunotherapy, asthma, drug hypersensitivity, allergic rhinitis, and other allergic diseases. Treatment of allergies using biologics during the COVID‐19 pandemic has also been discussed. Allergic reactions to the COVID‐19 vaccines, including severe anaphylaxis, have been reported. Vaccination is a prophylactic strategy that can lead to a significant reduction in the mortality and morbidity associated with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, and in this review, we discuss the proposed culprit components causing rare adverse reactions and recommendations to mitigate the risk of anaphylactic events during the administration of the vaccines.

Keywords: allergy, COVID‐19, mechanism, treatment, vaccination

1. PREVALENCE OF ALLERGY AND ASTHMA IN COVID‐19 PATIENTS

As the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) primarily affects the respiratory tract, a preliminary hypothesis based on knowledge from common airway viruses proposed that asthma and other respiratory comorbidities might aggravate susceptibility to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and lead to a more severe clinical outcome. 1 However, early data from Wuhan reported a lower prevalence of asthma among COVID‐19 cases. 2 Similar findings were observed in Italy, Brazil, and Russia, 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 even in severe asthma patients. 7 , 8 Other studies also suggested that asthma was not associated with delayed viral clearance, 9 poor clinical outcome, 4 , 10 , 11 , 12 and mortality rate. 8 Moreover, allergic status in children did not increase COVID‐19 incidence and its severity. 13 , 14 In contrast, published data in the United States and United Kingdom (UK) indicated an increased prevalence of COVID‐19 in patients with asthma. 15 , 16 , 17 Severe asthma treated with a high dose of inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) + long‐acting beta 2‐agonist (LABA) presented a higher Intensive Care Unit admission rate due to COVID‐19. 18 , 19 Moreover, epidemiologic data from Korean disease Control and Prevention showed asthma was associated with an increased risk of mortality and worse clinical outcomes of COVID‐19. 20 Skevaki et al. also suggested a complex relationship between prevalence and severity of COVID‐19 and allergy/asthma by reviewing more comprehensive epidemiologic data from different countries. 21 , 22

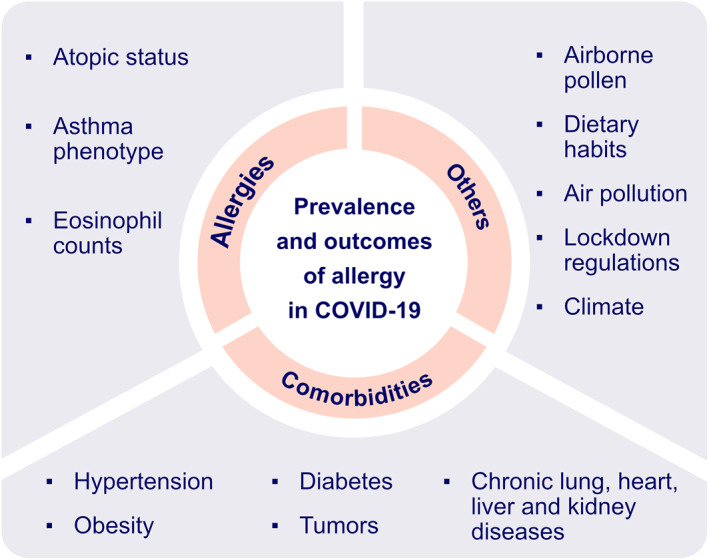

There are multiple factors that can account for these inconsistent findings including atopic status, 23 asthma phenotype, 24 , 25 eosinophil counts, 24 lockdown regulations, 12 , 26 dietary habits, 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 airborne pollen concentrations, 32 , 33 air pollution, 34 climate, 35 and comorbidities 12 (Figure 1). Respiratory atopy was suggested to have a protective role against severe lung disease in COVID‐19 patients with viral pneumonia. 23 However, in contrast to patients with concomitant allergic rhinitis and asthma, allergic rhinitis alone was not regarded as a comorbidity that could modify susceptibility to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection as there was no significant difference in ACE2 gene expression between allergic rhinitis subjects and controls. 36

FIGURE 1.

Potential factors associated with the prevalence and outcome of allergy in COVID‐19 patients. Atopic status is suggested to be associated with lower risk of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Asthma phenotype is found to be a strong determinant of disease severity in COVID‐19 with preexisting asthma. Lower eosinophil count is considered as predictive biomarker of severe COVID‐19. Airborne pollen concentration, dietary habits, lockdown regulations, climate and comorbidities might be responsible for inconsistent findings of prevalence of allergy in COVID‐19 patients

The asthma phenotype was found to be a strong determinant of disease severity. In a study from Stanford University, allergic asthma was found to mitigate the risk of hospitalization for COVID‐19 compared to patients with non‐allergic asthma (OR, 0.52). 24 In addition, patients with non‐allergic asthma were more susceptible to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and unfavorable clinical outcomes than patients with allergic asthma in a South Korean study. 25 Lower eosinophil counts were a predictive biomarker of severe disease progression independent of asthma phenotype. 24

Intriguingly, the prevalence of allergic diseases showed heterogeneous patterns during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Childhood asthma presented better outcomes with fewer asthma exacerbations leading to a reduced number of emergency visits and hospitalizations. Moreover, 66% of pediatric asthma patients had improved asthma control as measured by the improved forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and the peak expiratory flow (PEF). 37 In contrast, the number of hereditary angioedema attacks was notably increased due to restriction measures‐related anxiety, depression, stress and fear of COVID‐19. 38 , 39

A survey based on 14 member countries commissioned by the Asia Pacific Association of Allergy Asthma and Clinical Immunology (APAAACI) indicated an increased prevalence of allergic diseases among healthcare workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic, for example, ocular and airway allergy with extended use of surgical masks and eye protection; skin allergy due to prolonged use of gloves, protective equipment and frequent handwashing. 40

Systemic allergic reactions during the pandemic seemed to be drastically reduced as indicated by the number of patients attending an Emergency Department Unit in the UK, from 62 in the first half of pre‐pandemic 2019 to 10 in the same period of 2020. The clinical manifestations presented before the pandemic by 52% of patients were classified as mild, according to the Brown grading system, whilst during the pandemic the majority of patients (80%) experienced moderate systemic allergic reactions. 41

2. UNDERLYING MECHANISMS SUGGESTING A POTENTIAL PROTECTIVE ROLE OF ALLERGY IN COVID‐19

Allergy or atopy is characterized by a type 2 (T2) immune response against external antigens in individuals, in which genetic predisposition plays a major role. 42 Mendelian randomization analysis of 136 uncorrelated single nucleotide polymorphisms with a broad allergic disease phenotype demonstrated a positive association between genetic predisposition to any allergic disease and lower risk of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. 43 ACE2 is the major receptor for SARS‐CoV‐2 entry into the cells. ACE2 expression was reduced in differentiated airway epithelial cells treated with interleukin‐13 (IL‐13) or after exposure to cat allergen. Its expression was negatively correlated with allergic sensitization in nasal epithelium and Immunoglobulin E (IgE), IL‐13, fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) and other type 2 signatures. Similarly, transcriptomic data analysis suggested decreased ACE2 expression in the nasal epithelium of children with allergic asthma and allergic sensitization or with asthma and/or allergic rhinitis. 44 , 45 The transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2) cleaves the viral spike protein and regulates the interferon (IFN) response together with ACE2. 46 Increased TMPRSS2 expression was found in ex vivo airway epithelial cells in respiratory allergic subjects and was positively correlated with type 2 cytokines. 45 T2 inflammation could also induce its expression in the metaplastic mucus secretory cells via IL‐13 signaling. 46 Further studies were still needed to elucidate what atopy and asthma might render in the state of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection.

ACE2 gene expression was downregulated in the airway epithelial cells, including in the nasal polys, and the olfactory neuroepithelium. Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) was characterized by a type 2 immune signature with increased eosinophil counts in the olfactory mucosa. Moreover, ACE2 expression was negatively correlated with the number of eosinophils. 47 Pre‐existing eosinophilia was found to have a protective role as observed by a reduction in hospitalization with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. 48 In contrast, eosinopenia was predictive of poor disease outcome 49 and was usually found in deceased COVID‐19 patients. 50 , 51 , 52 A higher eosinophil count is a biomarker of allergic inflammation, and allergic subjects with eosinophilia were less susceptible to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. 50 Eosinophils were demonstrated to promote antiviral immunity in animal models. 53 They are known to induce secretion of Th1 cytokines, generation of superoxide and nitric oxide (NO), and recruitment of CD8+ T cells against respiratory virus infection. Eosinophil‐derived enzymes have been proposed to neutralize the virus via a ribonuclease‐dependent mechanism. 54 A lower eosinophil count was associated with CD8+ T cell depletion, which might be related to a Th17 inflammatory pattern in severe COVID‐19 patients. 55 , 56 , 57 Further studies are warranted to confirm these findings.

Although type I and III interferons (IFN‐ α/β and ‐λ respectively) are essential to abrogate viral infection, 3 , 58 , 59 excessive or prolonged type I IFN production promotes the release of proinflammatory chemokines that contribute to poor disease outcome by disrupting lung epithelial regeneration. 60 , 61 , 62 In contrast, early or low type I IFN production has a protective effect against SARS‐CoV‐1 infection via regulation of monocyte/macrophage lung infiltration, vascular leakage, cytokine storm and T‐cell responses in SARS‐CoV‐1‐infected mice. 63 Atopy has been reported to play a negative role in type I and III IFN production 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 by plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) with impaired toll‐like receptor (TLR) expression and signaling cross‐linked by IgE and histamine H2 receptors 64 (Figure 2). Since timing and robustness of type I IFN production is determinant for virus infection, more studies are furtherly demanded to explore the role of type I IFN in allergy and COVID‐19. Adaptive immune responses are also involved in allergy and modulate susceptibility to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, 68 for example, increased lymphocytes, notably T cells, were found in COVID‐19 patients with allergic comorbidities, suggesting milder SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in allergic patients. 69

FIGURE 2.

Immune responses to SARS‐CoV‐2. SARS‐CoV‐2 infection can cause epithelial cell lysis and directly destroy epithelium integrity. Subsequent to virus antigen presentation by dendritic cells, CD8+ T cells and natural killer cells induce cytotoxicity to infected epithelial cells and lead to apoptosis by releasing perforin and granzymes; CD4+ T cells differentiate into memory Th1, Th17 and memory T follicular helper (TFH). With the help of TFH, B cells develop into plasma cells (PC), contributing to virus‐specific antibodies production. In atopic subjects, IgE released by PC might play a negative role in the IFN‐α/β pathway regulation

Various skin manifestations have been reported in SARS‐CoV‐2 positive patients, 70 , 71 there are emerging studies indicating a relationship between skin allergy and COVID‐19. Transcriptomic analysis showed that AD patients had a higher expression of TMPRSS2 (encoding TMPRSS2), PPIA (encoding cyclophilin A), SLC7A5 (encoding CD98), and other molecules involved in COVID‐19 pathophysiological mechanisms, both in lesional and non‐lesional skin. 72 Moreover, based on the Proteomic Olink Proseek multiplex assay, a similar ACE2 expression pattern was found in healthy and AD subjects among adults and infant/toddlers, but elevated levels in the serum of adults with AD compared to infant/toddlers with AD. Cathepsin L/CTSL1 is a protein involved in the cleavage and priming of the SARS‐CoV‐1 spike protein and has been suggested to play a similar role in SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Elevated levels of CTSL1 were found in the serum and were positively correlated with ACE2 protein expression. 73

Treatment of allergic and non‐allergic asthma with ICS might also have an impact on the susceptibility to infection and COVID‐19 severity.

Even though the preliminary mechanistic data might suggest the protective role of type 2 inflammation against SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and COVID‐19 severity, further studies are urgently needed to evaluate these observations and to understand in detail these mechanisms in humans. This might also lead to the further development of new targets for pharmacological interventions against COVID‐19.

3. ALLERGY CARE DOES NOT STOP DURING COVID‐19

Although the COVID‐19 pandemic significantly impaired health care, management of allergic diseases was still ongoing by adhering to preventive measures. For example, there has been a shift of chronic urticaria consultation from face‐to‐face (decreased by 62%) towards telemedicine (increased by over 600%). 74 Telecommunication tools have been implemented during the COVID‐19 pandemic, 75 , 76 , 77 facilitating communication between doctors and patients whilst maintain social distancing. During the pandemic, mild‐to‐moderate or well‐controlled asthma patients were recommended to seek consultation online. 78 Outpatient service was more appropriate for patients whose symptoms were not resolved or worsened with the escalation of medication. 78 , 79

Based on a European Academy of Allergy & Clinical Immunology (EAACI) survey, nearly half of newly referred asthma patients received face‐to‐face consultation with telemedicine follow‐ups. The majority of lung function tests were temporarily postponed. Initial asthma diagnosis and therapy were largely based only on clinical manifestations. All these factors contributed to the lower quality of healthcare during the lockdown. In general, the performance of lung function tests together with efficient remote monitoring presented the biggest challenges for asthma management in both children and adults. 80

The small droplets (classically ≤5 microns) generated during pulmonary function tests contain SARS‐CoV‐2 and pose a significant risk of viral transmission in a healthcare setting. 81 , 82 Greening et al. quantified the mass of the aerosol particles emitted in different breathing maneuvers used to measure lung function. The mass of the exhaled particles was lowest during tidal breathing (TV), slow vital capacity following inspiration from functional residual capacity (sVC‐FRC) and forced expiratory volume (FEV). Coughing at total lung capacity generated the highest mass of exhaled particles. This data indicated that in the absence of coughing, spirometry did not pose a significant risk for viral transmission, which might be potentially beneficial for asthma diagnosis and follow‐up management. 82

Telemedicine ensures the safety of both patients and healthcare professionals during the COVID‐19 pandemic, for example, quantitative measuring of olfactory dysfunction using psychophysical analyses were remotely performed. 83 , 84 , 85 However, sputum induction, which is a widely used technique to evaluate airway inflammation and specially to classify the inflammatory phenotype of asthma can only be conducted in a hospital setting. As sputum induction generates aerosols it presents a high risk of viral transmission. In this case, the medical protocols were adapted to guarantee the safety of the patients and healthcare professionals, such as the use of personal protection equipment, and alternative sampling and processing procedures. 86

EAACI launched a series of statements and position papers providing official recommendations for the treatment of drug hypersensitivity, allergic rhinitis, asthma, and other allergic diseases during the COVID‐19 pandemic (Table 1) 14 , 87 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 . It also offered practical considerations on the organization of allergic clinics. 93 In summary, atopic diseases should be treated following current guidelines even among patients at risk or with active SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. These guidelines should be continuously updated as we gain knowledge of this evolving coronavirus.

TABLE 1.

The European Academy of Allergy & Clinical Immunology (EAACI) recommendations for the treatment of allergic diseases

| Atopic disease | Key messages | References |

|---|---|---|

| Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) | Intranasal corticosteroids are recommended for CRS patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, but systemic corticosteroids should be avoided. Surgery stays optional only with local complications or non‐responsive therapies. | [87] |

| Ocular allergy (OA) | Current EAACI recommendations for the management of OA 88 remain the same during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Corticosteroids and immunomodulators should be used with caution especially for patients with active SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. | [89] |

| Drug hypersensitivity reactions (DHRs) | DHRs occurred rarely and most were nonimmediate cutaneous reactions. Disease‐related exanthems were the most characteristic differential diagnosis of DHRs. | [90] |

| Asthma | Inhaled corticosteroids or prescribed long‐term oral corticosteroids should continue. Spacers of large capacity are suggested to replace nebulization in patients with active SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. | [91] |

| Allergic rhinitis | Use of intranasal corticosteroids (including spray) should be continued. | [92] |

4. ALLERGEN IMMUNOTHERAPY (AIT) AND BIOLOGICAL THERAPY FOR ALLERGY TREATMENT DURING COVID‐19

An APAAACI survey reported a decrease in AIT (46.1%) and immunosuppressive therapies (23.1%) in allergic patients during the COVID‐19 pandemic. 40 Unfortunately, patients with non‐adherent subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) for house dust mite allergy (≥2‐month delay) had higher median medication scores, visual analogue scale for quality of life, and total symptom scores. 94 On the other hand, venom‐specific immunotherapy was safely administered in Spanish clinics following a strict sanitary protocol. 95 Additionally, there was no reduced tolerability even among patients combined with early COVID‐19 symptoms and/or with positive SARS‐CoV‐2 results. 96 Therefore, patients should be encouraged to adhere to treatment during the pandemic to ensure a successful outcome of immunotherapy. 94 , 97 , 98

Biological therapeutics targeting type 2 inflammation pathways have been adopted in a wide range of allergic diseases. 99 , 100 , 101 The safety of biologicals during the pandemic has come into question as these are known to interact with T2 cytokines and may interfere with eosinophil‐mediated antiviral activity. Reduced production of IgG and IgM and absence of IgA antibodies were observed in a severe asthmatic patient undergoing dupilumab treatment. 102 Overall, a decreased (30.8%) use of biologicals in severe asthma was reported in an APAAACI survey. 40 An Italian national registry of teledermatology services during the COVID‐19 pandemic showed that 1580 patients (86.3%) among 1831 patients continued therapy, in which 86.1% of patients continued dupilumab with a withdrawal rate of only 9.9%, albeit a higher interruption rate with systemic immunosuppressive agents. Discontinuation of treatment was mainly due to fear of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection from patients (39.9%), general practitioners (5.6%), and dermatologists (30.1%). 103

Anti‐IgE antibody omalizumab has been reported to enhance the anti‐viral immune response by downregulating the high‐affinity IgE receptor on pDC. 44 , 104 Treatment of severe allergic asthma with omalizumab did not affect asthma control during symptomatic COVID‐19 disease. 8 , 105 The Italian Registry of Severe Asthma network showed no increased occurrence of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection among severe asthmatics treated with biologicals (omalizumab, mepolizumab, or benralizumab) compared to ICS + LABA alone. 7 Moreover, compared to age and geography matched non‐asthmatic subjects, severe asthma patients with ongoing biological therapy did not show any increased incidence of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. 106

In summary, according to an evidence‐based EACCI statement, treatment with biologicals should be maintained in noninfected cases with continuous evaluation of atopic disease progression. In the case of active SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, biologicals need to be postponed until clinical resolution is established. 91 , 107 , 108

5. VACCINATION OF COVID‐19 AND ALLERGY

Novel COVID‐19 vaccines are being developed as an indispensable prophylactic strategy to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with COVID‐19. 109 , 110 , 111 , 112 , 113 , 114 , 115 Classical signs of immediate allergic reactions have been reported within minutes of administration of SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines in susceptible individuals, such as conjunctivitis, rhinorrhea, bronchoconstriction, generalized urticaria and/or angioedema. A few rare cases of anaphylaxis have been reported after vaccine administration. 116 , 117 , 118 , 119 The scientific community has made great efforts to understand the immunopathological mechanisms underlying allergic reactions to COVID‐19 vaccines and their culprit component. 120 , 121 , 122 , 123

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) has been identified as a potential trigger of allergic reactions. PEGs are found in many daily products and are an integral part of the micellar delivery system of the Pfizer‐BioNTech BNT162b2 and the Moderna mRNA‐1273 vaccines containing mRNA coding the spike protein of SARS‐CoV‐2. 120 , 124 , 125 The pathological mechanisms underlying allergic reactions are not fully understood. Several studies suggest an IgE‐mediated reaction, 121 , 126 , 127 whilst others have proposed a complement activation‐related pseudoallergy (CARPA) mediated by anaphylatoxins C3a and C5a together with anti‐PEG IgM and IgG antibodies induced by PEGyated nanobodies. 121 , 127 , 128 Mast cell release might be associated with hyperreactivity to the vaccine in children with cutaneous mastocytosis. 127 , 129 , 130 AstraZeneca AZD1222 vaccine contains polysorbate 80 which has been demonstrated to have cross‐reactivity with PEGs as they share the ether moiety –(CH2CH2O) n, which has been suspected as a causal excipient of hypersensitivity reaction to human papillomavirus vaccine. 131 , 132

There are also other potential culprit agents such as distearoylphosphatidylcholine (DSPC) in the Pfizer‐BioNTech and Moderna vaccines, formerly attributed to hypersensitivity to pollen. Trometamol is added as a buffer in the Moderna vaccine and there has been a case report of anaphylaxis to this excipient in an intravenously administered radiocontrast agent. 133 Beta‐propiolactone (BPL), used to inactivate the virus, might induce an immune complex‐like reaction after vaccination, 121 which might cause an adverse reaction after a booster dose injection of the rabies human diploid cell vaccine. 134 , 135 Similar immunological mechanisms might be implicated in the adverse reactions associated with two widely used COVID‐19 vaccines in China, BBIBP‐CorV (Sinopharm) and Sinovac‐CoronaVac (Sinovac Life Sciences), which also contain BPL to inactivate SARS‐CoV‐2. 121

It is worth noting that allergic patients without a previous history to the vaccine components are not contraindicated for COVID‐19 vaccination. 136 An allergological work‐up for patients with a possible risk of severe hypersensitivity reactions is recommended. 137 The patients should be evaluated with skin tests for the vaccine and its excipients. Alternative vaccines that do not contain the suspected components could be considered in case of a positive skin result. In all cases, the vaccination should be followed with a minimum 15‐min observation. The vaccine should be administered in escalated doses for patients at a high risk of severe hypersensitivity reactions. An adrenaline (epinephrine) injector should be readily available to treat any anaphylactic event. 120 , 133 , 136 , 138

In conclusion, current evidence shows that allergy might play a protective role in COVID‐19 with the involvement of eosinophilia, SARS‐CoV‐2 related receptors expressions, and IFN responses, and other immunological events. Further research is warranted to improve our understanding of the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms. Allergy care has continued during the COVID‐19 pandemic and official recommendations from EAACI have been developed to inform healthcare professionals on the management and treatment of allergies during this time. Patients with a previous history of allergic reactions to a component of the COVID‐19 vaccines should be referred to an allergy clinic for a diagnostic workup.

There is a current need to improve our understanding of the underlying mechanisms involved in the vaccines adverse reactions and their culprit components to ensure their safety and public compliance.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None of the authors has any conflicts of interest to declare.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

None.

Ding M, Dong X, Sun Y‐l, et al. Recent advances and developments in COVID‐19 in the context of allergic diseases. Clin Transl Allergy. 2021;e12065. doi: 10.1002/clt2.12065

Contributor Information

Cezmi A. Akdis, Email: akdisac@siaf.uzh.ch.

Ya‐dong Gao, Email: gaoyadong@whu.edu.cn, Email: akdisac@siaf.uzh.ch.

REFERENCES

- 1. Johnston SL. Asthma and COVID‐19: is asthma a risk factor for severe outcomes? Allergy. 2020;75:1543‐1545. doi: 10.1111/all.14348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhang JJ, Dong X, Cao YY, et al. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS‐CoV‐2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy. 2020;75:1730‐1741. doi: 10.1111/all.14238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carli G, Cecchi L, Stebbing J, Parronchi P, Farsi A. Is asthma protective against COVID‐19? Allergy. 2021;76:866‐868. doi: 10.1111/all.14426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alberca RW, Yendo T, Aoki V, Sato MN. Asthmatic patients and COVID‐19: different disease course? Allergy. 2021;76:963‐965. doi: 10.1111/all.14601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Avdeev S, Moiseev S, Brovko M, et al. Low prevalence of bronchial asthma and chronic obstructive lung disease among intensive care unit patients with COVID‐19. Allergy. 2020;75:2703‐2704. doi: 10.1111/all.14420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carli G, Cecchi L, Stebbing J, Parronchi P, Farsi A. Asthma phenotypes, comorbidities, and disease activity in COVID‐19: the need of risk stratification. Allergy. 2021;76:955‐956. doi: 10.1111/all.14537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Antonicelli L, Tontini C, Manzotti G, et al. Severe asthma in adults does not significantly affect the outcome of COVID‐19 disease: results from the Italian Severe Asthma Registry. Allergy. 2021;76:902‐905. doi: 10.1111/all.14558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Heffler E, Detoraki A, Contoli M, et al. COVID‐19 in Severe Asthma Network in Italy (SANI) patients: clinical features, impact of comorbidities and treatments. Allergy. 2021;76:887‐892. doi: 10.1111/all.14532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kim S, Jung CG, Lee JY, et al. Characterization of asthma and risk factors for delayed SARS‐CoV‐2 clearance in adult COVID‐19 inpatients in Daegu. Allergy. 2021;76:918‐921. doi: 10.1111/all.14609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lovinsky‐Desir S, Deshpande DR, De A, et al. Asthma among hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 and related outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:1027‐1034. e1024. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.07.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lombardi C, Roca E, Bigni B, Cottini M, Passalacqua G. Clinical course and outcomes of patients with asthma hospitalized for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 pneumonia: a single‐center, retrospective study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;125:707‐709. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2020.07.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Heffler E, Detoraki A, Contoli M, et al. Reply to: Kow CS et al. Are severe asthma patients at higher risk of developing severe outcomes from COVID‐19? Allergy. 2021;76:961‐962. doi: 10.1111/all.14593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dong X, Cao YY, Lu XX, et al. Eleven faces of coronavirus disease 2019. Allergy. 2020;75:1699‐1709. doi: 10.1111/all.14289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pfaar O, Torres MJ, Akdis CA. COVID‐19: a series of important recent clinical and laboratory reports in immunology and pathogenesis of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and care of allergy patients. Allergy. 2021;76:622‐625. doi: 10.1111/all.14472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Garg S, Kim L, Whitaker M, et al. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory‐confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 ‐ COVID‐NET, 14 states, March 1–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:458‐464. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Khawaja AP, Warwick AN, Hysi PG, et al. Associations with Covid‐19 hospitalisation amongst 406,793 adults: the UK Biobank prospective cohort study. medRxiv. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.05.06.20092957 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Morais‐Almeida M, Barbosa MT, Sousa CS, Aguiar R, Bousquet J. Update on asthma prevalence in severe COVID‐19 patients. Allergy. 2021;76:953‐954. doi: 10.1111/all.14482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chhiba KD, Patel GB, Vu THT, et al. Prevalence and characterization of asthma in hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients with COVID‐19. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:307‐314. e304. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kow CS, Capstick T, Hasan SS. Are severe asthma patients at higher risk of developing severe outcomes from COVID‐19? Allergy. 2021;76:959‐960. doi: 10.1111/all.14589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Choi HG, Wee JH, Kim SY, et al. Association between asthma and clinical mortality/morbidity in COVID‐19 patients using clinical epidemiologic data from Korean Disease Control and Prevention. Allergy. 2021;76:921‐924. doi: 10.1111/all.14675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Skevaki C, Karsonova A, Karaulov A, Xie M, Renz H. Asthma‐associated risk for COVID‐19 development. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:1295‐1301. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.09.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Skevaki C, Karsonova A, Karaulov A, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and COVID‐19 in asthmatics: a complex relationship. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21:202‐203. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00516-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Scala E, Abeni D, Tedeschi A, et al. Atopic status protects from severe complications of COVID‐19. Allergy. 2021;76:899‐902. doi: 10.1111/all.14551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Eggert LE, He Z, Collins W, et al. Asthma phenotypes, associated comorbidities, and long‐term symptoms in COVID‐19. Allergy. 2021. doi: 10.1111/all.14972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yang JM, Koh HY, Moon SY, et al. Allergic disorders and susceptibility to and severity of COVID‐19: a nationwide cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:790‐798. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kraemer MUG, Yang CH, Gutierrez B, et al. The effect of human mobility and control measures on the COVID‐19 epidemic in China. Science. 2020;368:493‐497. doi: 10.1126/science.abb4218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Anto JM, Bousquet J. Reply to “cabbage and COVID‐19”. Allergy. 2021;76:968‐968. doi: 10.1111/all.14653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Soriano JB, Ancochea J. Cabbage and COVID‐19. Allergy. 2021;76:966‐967. doi: 10.1111/all.14654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bousquet J, Anto JM, Czarlewski W, et al. Cabbage and fermented vegetables: from death rate heterogeneity in countries to candidates for mitigation strategies of severe COVID‐19. Allergy. 2021;76:735‐750. doi: 10.1111/all.14549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bousquet J, Anto JM, Iaccarino G, et al. Is diet partly responsible for differences in COVID‐19 death rates between and within countries? Clin Transl Allergy. 2020;10:16. doi: 10.1186/s13601-020-00323-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bousquet J, Cristol JP, Czarlewski W, et al. Nrf2‐interacting nutrients and COVID‐19: time for research to develop adaptation strategies. Clin Transl Allergy. 2020;10:58. doi: 10.1186/s13601-020-00362-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Damialis A, Gilles S, Sofiev M, et al. Higher airborne pollen concentrations correlated with increased SARS‐CoV‐2 infection rates, as evidenced from 31 countries across the globe. Proc Natl Acad Sci U. S. A. 2021;118:118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2019034118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Damialis A, Gilles S, Traidl‐Hoffmann C. Adding the variable of environmental complexity into the COVID‐19 pandemic equation. Allergy. 2021. doi: 10.1111/all.14966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Annesi‐Maesano I, Maesano CN, D'Amato M, D'Amato G. Pros and cons for the role of air pollution on COVID‐19 development. Allergy. 2021;76:2647‐2649. doi: 10.1111/all.14818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. The L. Climate and COVID‐19: converging crises. Lancet. 2021;397:71. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)32579-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang H, Song J, Yao Y, et al. Angiotensin‐converting enzyme II expression and its implication in the association between COVID‐19 and allergic rhinitis. Allergy. 2021;76:906‐910. doi: 10.1111/all.14569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Papadopoulos NG, Mathioudakis AG, Custovic A, et al. Childhood asthma outcomes during the COVID‐19 pandemic: findings from the PeARL multi‐national cohort. Allergy. 2021;76:1765‐1775. doi: 10.1111/all.14787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. McGinty EE, Presskreischer R, Anderson KE, Han H, Barry CL. Psychological distress and COVID‐19‐related stressors reported in a longitudinal cohort of US adults in April and July 2020. Jama. 2020;324:2555‐2557. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.21231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Eyice Karabacak D, Demir S, Yeğit OO, et al. Impact of anxiety, stress and depression related to COVID‐19 pandemic on the course of hereditary angioedema with C1‐inhibitor deficiency. Allergy. 2021;76:2535‐2543. doi: 10.1111/all.14796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pawankar R, Thong BY, Tiongco‐Recto M, et al. Asia‐Pacific perspectives on the COVID‐19 pandemic. Allergy. 2021;76:2998‐2901. doi: 10.1111/all.14894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pur Ozyigit L, Khalil G, Choudhry T, Williams M, Khan N. Anaphylaxis in the emergency department unit: before and during COVID‐19. Allergy. 2021;76:2624‐2626. doi: 10.1111/all.14873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wynn TA. Type 2 cytokines: mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:271‐282. doi: 10.1038/nri3831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Larsson SC, Gill D. Genetic predisposition to allergic diseases is inversely associated with risk of COVID‐19. Allergy. 2021;76:1911‐1913. doi: 10.1111/all.14728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jackson DJ, Busse WW, Bacharier LB, et al. Association of respiratory allergy, asthma, and expression of the SARS‐CoV‐2 receptor ACE2. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:203‐206. e203. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kimura H, Francisco D, Conway M, et al. Type 2 inflammation modulates ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in airway epithelial cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:80‐88. e88. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sajuthi SP, DeFord P, Li Y, et al. Type 2 and interferon inflammation regulate SARS‐CoV‐2 entry factor expression in the airway epithelium. Nat Commun. 2020;11:5139. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18781-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Marin C, Tubita V, Langdon C, et al. ACE2 downregulation in olfactory mucosa: eosinophilic rhinosinusitis as COVID‐19 protective factor? Allergy. 2021;76:2904‐2907. doi: 10.1111/all.14904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ferastraoaru D, Hudes G, Jerschow E, et al. Eosinophilia in asthma patients is protective against severe COVID‐19 illness. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:1152‐1162. e1153. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.12.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Li Q, Ding X, Xia G, et al. Eosinopenia and elevated C‐reactive protein facilitate triage of COVID‐19 patients in fever clinic: a retrospective case‐control study. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;23:100375. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Du Y, Tu L, Zhu P, et al. Clinical features of 85 fatal cases of COVID‐19 from Wuhan. A retrospective observational study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:1372‐1379. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0543OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Glickman JW, Pavel AB, Guttman‐Yassky E, Miller RL. The role of circulating eosinophils on COVID‐19 mortality varies by race/ethnicity. Allergy. 2021;76:925‐927. doi: 10.1111/all.14708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhao L, Zhang YP, Yang X, Liu X. Eosinopenia is associated with greater severity in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Allergy. 2021;76:562‐564. doi: 10.1111/all.14455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Samarasinghe AE, Melo RC, Duan S, et al. Eosinophils promote antiviral immunity in mice infected with influenza A virus. J Immunol. 2017;198:3214‐3226. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lindsley AW, Schwartz JT, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophil responses during COVID‐19 infections and coronavirus vaccination. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:1‐7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wu D, Yang XO. TH17 responses in cytokine storm of COVID‐19: an emerging target of JAK2 inhibitor Fedratinib. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53:368‐370. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Jacobsen EA, Zellner KR, Colbert D, Lee NA, Lee JJ. Eosinophils regulate dendritic cells and Th2 pulmonary immune responses following allergen provocation. J Immunol. 2011;187:6059‐6068. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Jesenak M, Banovcin P, Diamant Z. COVID‐19, chronic inflammatory respiratory diseases and eosinophils‐Observations from reported clinical case series. Allergy. 2020;75:1819‐1822. doi: 10.1111/all.14353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hadjadj J, Yatim N, Barnabei L, et al. Impaired type I interferon activity and inflammatory responses in severe COVID‐19 patients. Science. 2020;369:718‐724. doi: 10.1126/science.abc6027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Combes AJ, Courau T, Kuhn NF, et al. Global absence and targeting of protective immune states in severe COVID‐19. Nature. 2021;591:124‐130. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03234-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Richardson PJ, Corbellino M, Stebbing J. Baricitinib for COVID‐19: a suitable treatment?–Authors' reply. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:1013‐1014. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30270-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Major J, Crotta S, Llorian M, et al. Type I and III interferons disrupt lung epithelial repair during recovery from viral infection. Science. 2020;369:712‐717. doi: 10.1126/science.abc2061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kim MH, Salloum S, Wang JY, et al. Type I, II, and III interferon signatures correspond to COVID‐19 disease severity. J Infect Dis. 2021;224:777‐782. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Channappanavar R, Fehr AR, Vijay R, et al. Dysregulated type I interferon and inflammatory monocyte‐macrophage responses cause lethal pneumonia in SARS‐CoV‐infected mice. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19:181‐193. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Gonzales‐van Horn SR, Farrar JD. Interferon at the crossroads of allergy and viral infections. J Leukoc Biol. 2015;98:185‐194. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3RU0315-099R [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lebre MC, van Capel TM, Bos JD, Knol EF, Kapsenberg ML, de Jong EC. Aberrant function of peripheral blood myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells in atopic dermatitis patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:969‐976. e965. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Maggi E, Parronchi P, Manetti R, et al. Reciprocal regulatory effects of IFN‐gamma and IL‐4 on the in vitro development of human Th1 and Th2 clones. J Immunol. 1992;148:2142‐2147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Contoli M, Ito K, Padovani A, et al. Th2 cytokines impair innate immune responses to rhinovirus in respiratory epithelial cells. Allergy. 2015;70:910‐920. doi: 10.1111/all.12627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sokolowska M, Lukasik ZM, Agache I, et al. Immunology of COVID‐19: mechanisms, clinical outcome, diagnostics, and perspectives‐A report of the European Academy of allergy and clinical immunology (EAACI). Allergy. 2020;75:2445‐2476. doi: 10.1111/all.14462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Shi W, Gao Z, Ding Y, Zhu T, Zhang W, Xu Y. Clinical characteristics of COVID‐19 patients combined with allergy. Allergy. 2020;75:2405‐2408. doi: 10.1111/all.14434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Novak N, Peng W, Naegeli MC, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2, COVID‐19, skin and immunology ‐ what do we know so far? Allergy. 2021;76:698‐713. doi: 10.1111/all.14498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Shinkai K, Bruckner AL. Dermatology and COVID‐19. Jama. 2020;324:1133‐1134. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.15276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Radzikowska U, Ding M, Tan G, et al. Distribution of ACE2, CD147, CD26, and other SARS‐CoV‐2 associated molecules in tissues and immune cells in health and in asthma, COPD, obesity, hypertension, and COVID‐19 risk factors. Allergy. 2020;75:2829‐2845. doi: 10.1111/all.14429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Pavel AB, Wu J, Renert‐Yuval Y, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 receptor ACE2 protein expression in serum is significantly associated with age. Allergy. 2021;76:875‐878. doi: 10.1111/all.14522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kocatürk E, Salman A, Cherrez‐Ojeda I, et al. The global impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on the management and course of chronic urticaria. Allergy. 2021;76:816‐830. doi: 10.1111/all.14687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Keesara S, Jonas A, Schulman K. Covid‐19 and health care's digital revolution. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2005835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid‐19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1679‐1681. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2003539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Webster P. Virtual health care in the era of COVID‐19. Lancet. 2020;395:1180‐1181. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30818-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Chang C, Zhang L, Dong F, et al. Asthma control, self‐management, and healthcare access during the COVID‐19 epidemic in Beijing. Allergy. 2021;76:586‐588. doi: 10.1111/all.14591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Shaker MS, Oppenheimer J, Grayson M, et al. COVID‐19: pandemic contingency planning for the allergy and immunology clinic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:1477‐1488. e1475. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Eguiluz‐Gracia I, van den Berge M, Boccabella C, et al. Real‐life impact of COVID‐19 pandemic lockdown on the management of pediatric and adult asthma: a survey by the EAACI Asthma Section. Allergy. 2021;76:2776‐2784. doi: 10.1111/all.14831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Bahl P, Doolan C, de Silva C, Chughtai AA, Bourouiba L, MacIntyre CR. Airborne or droplet precautions for health workers treating COVID‐19? J Infect Dis. 2020. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Greening NJ, Larsson P, Ljungström E, Siddiqui S, Olin AC. Small droplet emission in exhaled breath during different breathing manoeuvres: implications for clinical lung function testing during COVID‐19. Allergy. 2021;76:915‐917. doi: 10.1111/all.14596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Klimek L, Hagemann J, Alali A, et al. Telemedicine allows quantitative measuring of olfactory dysfunction in COVID‐19. Allergy. 2021;76:868‐870. doi: 10.1111/all.14467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Whitcroft KL, Hummel T. Olfactory dysfunction in COVID‐19: diagnosis and management. J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323:2512‐2514. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Hopkins C, Smith B. Widespread smell testing for COVID‐19 has limited application. Lancet. 2020;396:1630. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)32317-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Crespo‐Lessmann A, Plaza V, Almonacid C, et al. Multidisciplinary consensus on sputum induction biosafety during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Allergy. 2021;76:2407‐2419. doi: 10.1111/all.14697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Klimek L, Jutel M, Bousquet J, et al. Management of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis during the COVID‐19 pandemic‐An EAACI position paper. Allergy. 2021;76:677‐688. doi: 10.1111/all.14629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Leonardi A, Silva D, Perez Formigo D, et al. Management of ocular allergy. Allergy. 2019;74:1611‐1630. doi: 10.1111/all.13786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Leonardi A, Fauquert JL, Doan S, et al. Managing ocular allergy in the time of COVID‐19. Allergy. 2020;75:2399‐2402. doi: 10.1111/all.14361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Gelincik A, Brockow K, Çelik GE, et al. Diagnosis and management of the drug hypersensitivity reactions in Coronavirus disease 19: an EAACI Position Paper. Allergy. 2020;75:2775‐2793. doi: 10.1111/all.14439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Bousquet J, Jutel M, Akdis CA, et al. ARIA‐EAACI statement on asthma and COVID‐19 (June 2, 2020). Allergy. 2021;76:689‐697. doi: 10.1111/all.14471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Bousquet J, Akdis C, Jutel M, et al. Intranasal corticosteroids in allergic rhinitis in COVID‐19 infected patients: an ARIA‐EAACI statement. Allergy. 2020;75:2440‐2444. doi: 10.1111/all.14302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Pfaar O, Klimek L, Jutel M, et al. COVID‐19 pandemic: practical considerations on the organization of an allergy clinic‐An EAACI/ARIA Position Paper. Allergy. 2021;76:648‐676. doi: 10.1111/all.14453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Yeğit OO, Demir S, Ünal D, et al. Adherence to subcutaneous immunotherapy with aeroallergens in real‐life practice during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Allergy. 2021. doi: 10.1111/all.14876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Martínez‐Lourido E, Otero A, Armisén M, Vidal C. Comment on: Bilò MB, Pravettoni V, Mauro M, Bonadonna P. Treating venom allergy during COVID‐19 pandemic: management of venom allergen immunotherapy during the COVID‐19 outbreak in Spain. Allergy. 2021;76:951‐952. doi: 10.1111/all.14567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Pfaar O, Agache I, Bonini M, et al. COVID‐19 pandemic and allergen immunotherapy ‐ an EAACI survey. Allergy. 2021. doi: 10.1111/all.14793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Bilò MB, Pravettoni V, Mauro M, Bonadonna P. Treating venom allergy during COVID‐19 pandemic. Allergy. 2021;76:949‐950. doi: 10.1111/all.14473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Klimek L, Jutel M, Akdis C, et al. Handling of allergen immunotherapy in the COVID‐19 pandemic: an ARIA‐EAACI statement. Allergy. 2020;75:1546‐1554. doi: 10.1111/all.14336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Holgate S, Casale T, Wenzel S, Bousquet J, Deniz Y, Reisner C. The anti‐inflammatory effects of omalizumab confirm the central role of IgE in allergic inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:459‐465. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.11.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Guttman‐Yassky E, Bissonnette R, Ungar B, et al. Dupilumab progressively improves systemic and cutaneous abnormalities in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143:155‐172. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Weinstein SF, Katial R, Jayawardena S, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in perennial allergic rhinitis and comorbid asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142:171‐177. e171. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.11.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Bhalla A, Mukherjee M, Radford K, et al. Dupilumab, severe asthma airway responses, and SARS‐CoV‐2 serology. Allergy. 2021;76:957‐958. doi: 10.1111/all.14534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Chiricozzi A, Talamonti M, De Simone C, et al. Management of patients with atopic dermatitis undergoing systemic therapy during COVID‐19 pandemic in Italy: data from the DA‐COVID‐19 registry. Allergy. 2021;76:1813‐1824. doi: 10.1111/all.14767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Fidel PL, Jr. , Noverr MC. Could an unrelated live attenuated vaccine serve as a preventive measure to dampen septic inflammation associated with COVID‐19 infection? mBio. 2020;11:11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00907-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Lommatzsch M, Stoll P, Virchow JC. COVID‐19 in a patient with severe asthma treated with Omalizumab. Allergy. 2020;75:2705‐2708. doi: 10.1111/all.14456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Matucci A, Caminati M, Vivarelli E, et al. COVID‐19 in severe asthmatic patients during ongoing treatment with biologicals targeting type 2 inflammation: results from a multicenter Italian survey. Allergy. 2021;76:871‐874. doi: 10.1111/all.14516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Riggioni C, Comberiati P, Giovannini M, et al. A compendium answering 150 questions on COVID‐19 and SARS‐CoV‐2. Allergy. 2020;75:2503‐2541. doi: 10.1111/all.14449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Vultaggio A, Agache I, Akdis CA, et al. Considerations on biologicals for patients with allergic disease in times of the COVID‐19 pandemic: an EAACI statement. Allergy. 2020;75:2764‐2774. doi: 10.1111/all.14407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Benenson S, Oster Y, Cohen MJ, Nir‐Paz R. BNT162b2 mRNA covid‐19 vaccine effectiveness among health care workers. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1775‐1777. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2101951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Shimabukuro TT, Kim SY, Myers TR, et al. Preliminary findings of mRNA covid‐19 vaccine safety in pregnant persons. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2273‐2282. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2104983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Sadoff J, Gray G, Vandebosch A, et al. Safety and efficacy of single‐dose Ad26.COV2.S vaccine against covid‐19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2187‐2201. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2101544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Heath PT, Galiza EP, Baxter DN, et al. Safety and efficacy of NVX‐CoV2373 covid‐19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Lopez Bernal J, Andrews N, Gower C, et al. Effectiveness of COVID‐19 vaccines against the B.1.617.2 (delta) variant. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:585‐594. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2108891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Thompson MG, Burgess JL, Naleway AL, et al. Prevention and attenuation of COVID‐19 with the BNT162b2 and mRNA‐1273 vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:320‐329. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Knoll MD, Wonodi C. Oxford‐AstraZeneca COVID‐19 vaccine efficacy. Lancet. 2021;397:72‐74. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)32623-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Frenck RW, Jr. , Klein NP, Kitchin N, et al. Safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of the BNT162b2 COVID‐19 vaccine in adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:239‐250. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Walsh EE, Frenck RW, Jr. , Falsey AR, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of two RNA‐based COVID‐19 vaccine candidates. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2439‐2450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2027906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID‐19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603‐2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Shimabukuro T, Nair N. Allergic reactions including anaphylaxis After receipt of the first dose of pfizer‐BioNTech COVID‐19 vaccine. Jama. 2021;325:780‐781. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.0600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Klimek L, Jutel M, Akdis CA, et al. ARIA‐EAACI statement on severe allergic reactions to COVID‐19 vaccines ‐ an EAACI‐ARIA Position Paper. Allergy. 2021;76:1624‐1628. doi: 10.1111/all.14726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Sampath V, Rabinowitz G, Shah M, et al. Vaccines and allergic reactions: the past, the current COVID‐19 pandemic, and future perspectives. Allergy. 2021;76:1640‐1660. doi: 10.1111/all.14840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Schaffer DeRoo S, Pudalov NJ, Fu LY. Planning for a COVID‐19 vaccination program. Jama. 2020;323:2458‐2459. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Amit S, Regev‐Yochay G, Afek A, Kreiss Y, Leshem E. Early rate reductions of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and COVID‐19 in BNT162b2 vaccine recipients. Lancet. 2021;397:875‐877. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00448-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Cabanillas B, Akdis CA, Novak N. Allergic reactions to the first COVID‐19 vaccine: a potential role of polyethylene glycol? Allergy. 2021;76:1617‐1618. doi: 10.1111/all.14711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Pfaar O, Mahler V. Allergic reactions to COVID‐19 vaccinations‐unveiling the secret(s). Allergy. 2021;76:1621‐1623. doi: 10.1111/all.14734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Krantz MS, Liu Y, Phillips EJ, Stone CA, Jr. COVID‐19 vaccine anaphylaxis: PEG or not? Allergy. 2021;76:1934‐1937. doi: 10.1111/all.14722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Cabanillas B, Akdis CA, Novak N. COVID‐19 vaccine anaphylaxis: IgE, complement or what else? A reply to: COVID‐19 vaccine anaphylaxis: PEG or not? Allergy. 2021;76:1938‐1940. doi: 10.1111/all.14725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Klimek L, Novak N, Cabanillas B, Jutel M, Bousquet J, Akdis CA. Allergenic components of the mRNA‐1273 vaccine for COVID‐19: possible involvement of polyethylene glycol and IgG‐mediated complement activation. Allergy. 2021. doi: 10.1111/all.14794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Zanoni G, Zanotti R, Schena D, Sabbadini C, Opri R, Bonadonna P. Vaccination management in children and adults with mastocytosis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2017;47:593‐596. doi: 10.1111/cea.12882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Matito A, Carter M. Cutaneous and systemic mastocytosis in children: a risk factor for anaphylaxis? Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015;15:22. doi: 10.1007/s11882-015-0525-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Cabanillas B, Akdis CA, Novak N. COVID‐19 vaccines and the role of other potential allergenic components different from PEG. A reply to: “Other excipients than PEG might cause serious hypersensitivity reactions in COVID‐19 vaccines”. Allergy. 2021;76:1943‐1944. doi: 10.1111/all.14761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Badiu I, Geuna M, Heffler E, Rolla G. Hypersensitivity reaction to human papillomavirus vaccine due to polysorbate 80. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;bcr0220125797. doi: 10.1136/bcr.02.2012.5797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Borgsteede SD, Geersing TH, Tempels‐Pavlica Ž. Other excipients than PEG might cause serious hypersensitivity reactions in COVID‐19 vaccines. Allergy. 2021;76:1941‐1942. doi: 10.1111/all.14774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Systemic allergic reactions following immunization with human diploid cell rabies vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1984;33, 185‐187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Huang DB, Wu JJ, Tyring SK. A review of licensed viral vaccines, some of their safety concerns, and the advances in the development of investigational viral vaccines. J Infect. 2004;49:179‐209. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.05.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Sokolowska M, Eiwegger T, Ollert M, et al. EAACI statement on the diagnosis, management and prevention of severe allergic reactions to COVID‐19 vaccines. Allergy. 2021;76:1629‐1639. doi: 10.1111/all.14739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Rasmussen TH, Mortz CG, Georgsen TK, Rasmussen HM, Kjaer HF, Bindslev‐Jensen C. Patients with suspected allergic reactions to COVID‐19 vaccines can be safely revaccinated after diagnostic work‐up. Clin Transl Allergy. 2021;11:e12044. doi: 10.1002/clt2.12044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Bousquet J, Agache I, Blain H, et al. Management of anaphylaxis due to COVID‐19 vaccines in the elderly. Allergy. 2021. doi: 10.1111/all.14838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]