Abstract

Background

Platelet activation and thrombotic events characterizes COVID‐19.

Objectives

To characterize platelet activation and determine if SARS‐CoV‐2 induces platelet activation.

Patients/Methods

We investigated platelet activation in 119 COVID‐19 patients at admission in a university hospital in Milan, Italy, between March 18 and May 5, 2020. Sixty‐nine subjects (36 healthy donors, 26 patients with coronary artery disease, coronary artery disease, and seven patients with sepsis) served as controls.

Results

COVID‐19 patients had activated platelets, as assessed by the expression and distribution of HMGB1 and von Willebrand factor, and by the accumulation of platelet‐derived (plt) extracellular vesicles (EVs) and HMGB1+ plt‐EVs in the plasma. P‐selectin upregulation was not detectable on the platelet surface in a fraction of patients (55%) and the concentration of soluble P‐selectin in the plasma was conversely increased. The plasma concentration of HMGB1+ plt‐EVs of patients at hospital admission remained in a multivariate analysis an independent predictor of the clinical outcome, as assessed using a 6‐point ordinal scale (from 1 = discharged to 6 = death). Platelets interacting in vitro with SARS‐CoV‐2 underwent activation, which was replicated using SARS‐CoV‐2 pseudo‐viral particles and purified recombinant SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein S1 subunits. Human platelets express CD147, a putative coreceptor for SARS‐CoV‐2, and Spike‐dependent platelet activation, aggregation and granule release, release of soluble P‐selectin and HMGB1+ plt‐EVs abated in the presence of anti‐CD147 antibodies.

Conclusions

Hence, an early and intense platelet activation, which is reproduced by stimulating platelets in vitro with SARS‐CoV‐2, characterizes COVID‐19 and could contribute to the inflammatory and hemostatic manifestations of the disease.

Keywords: COVID‐19, HMGB1, platelets, P‐selectin, SARS‐CoV‐2

ESSENTIALS

-

•

Activation of platelets in COVID‐19 is heterogeneous.

-

•

Platelets challenged with SARS‐CoV‐2 undergo activation, dependent on the CD147 receptor.

-

•

Activated platelets release soluble P‐selectin and HMGB1+ extracellular vesicles.

-

•

Early accumulation of platelet HMGB1+ extracellular vesicles predicts worse clinical outcomes.

Alt-text: Unlabelled Box

1. INTRODUCTION

Endothelial activation in various organs with the recruitment of inflammatory cells and activation of the coagulation system with venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism and microvascular angiopathy/thrombosis are hallmarks of COVID‐19. These events contribute to organ dysfunction in critically ill patients with SARS‐CoV‐21., 2., 3. and thrombocytopenia. The main function of platelets is indeed hemostatic. They patrol the vasculature and guard its integrity, undergoing activation in response to damaged endothelia. Moreover, platelets express surface receptors that directly interact with microbes4 and contribute to the host response at various levels, via the release of microbicidal agents from granules and via the recruitment of cellular and humoral innate immunity. Megakaryocytes and platelets are a preferential target of selected microbes, flaviviruses in particular,5 and thrombocytopenia is common in acute viral infections.

A decrease in platelet counts, more frequent in patients with worse clinical outcomes, has been described in COVID‐19.6., 7. However, platelet counts per se may not be sufficiently informative in an ongoing infection, as thrombocytopenia may reflect a decrease in platelet production in the bone marrow, an increase in peripheral destruction and clearance of platelets or a combination of the two events. Conversely, platelet activation could result in the generation of bioactive extracellular vesicles (EVs) that reach distant sites through the circulatory system and perpetuate damage and inflammation in various organs, including the lung.8., 9., 10. Recently, platelet activation in patients with COVID‐19 has been independently described in various cohorts.11., 12., 13., 14., 15. Differential gene expression profile of platelets of COVID‐19 patients was associated with enhanced ability to aggregate and to form aggregates with leukocytes11 and platelet activation was prominent in patients with severe disease.12., 14. Additionally, a major platelet response to SARS‐CoV‐2 has recently been described, which included massive release of granule content, generation of microparticles, and eventual death by apoptosis or necroptosis.16 ACE2, the only primary receptor identified so far, appears to be dispensable for the interaction between platelets and SARS‐CoV‐2.16., 17., 18. Here, we have identified platelet‐derived extracellular vesicles expressing the DAMP, HMGB1 as surrogate markers of platelet activation that predict the outcome of COVID‐19, and the CD147 receptor as a critical player in the activation of host platelets following interaction with SARS‐CoV‐2.

2. PATIENTS AND METHODS

2.1. Patients

Patients ≥18 years old diagnosed with COVID‐19 at the IRCCS San Raffaele Hospital, a 1350‐bed tertiary care University Hospital in Milan, Italy, between March 18 and May 5, 2020, were enrolled. All patients belonged to the COVID‐19 San Raffaele clinical‐biological cohort (Covid‐BioB, ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04318366). The study conforms to the Declaration of Helsinki and obtained ethical approval from the institutional review board (protocol number 34/int/2020). Written informed consent was obtained by all patients. Characteristics of the cohort have been described.1 All patients with COVID‐19 with a positive SARS‐CoV‐2 real‐time RT‐PCR from a nasal and/or throat swab and for which we were able to timely obtain and process blood were studied. Data collected from chart review and patient interview were entered in a dedicated electronic case record form. Twenty‐six patients with coronary artery disease (CAD), seven patients with severe sepsis, and 36 healthy donors served as controls (Table 1 ).

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics and main clinical and laboratory findings of patients at time of blood sampling

| COVID‐19 patients | Sepsis | HD | CAD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 119 | 7 | 36 | 26 |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 60 (50–72) | 79 (67–82) * | 58 (51–69) | 62 (57–69) |

| Female, n (%) | 50 (42) | 5 (71.4) | 19 (52.8) | 3 (11.5) |

| BMI (kg/cm2), median (IQR) | 27 (25–30) | ‐ | 24 (23–25) * | 26 (24–29) |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| HTN, n (%) | 41 (34.5) | 2 (28.6) | 0*** | 18 (69.2)** |

| CAD, n (%) | 10 (8.4) | 3 (42.9)* | 0 | 26 (100)*** |

| DM, n (%) | 18 (15.1) | 3 (42.9) | 0* | 2 (7.7) |

| COPD, n (%) | 6 (5.0) | 2 (28.6) | 0 | 0 |

| CKD, n (%) | 8 (6.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Neoplasia, n (%) | 7 (5.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Autoimmune disease, n (%) | 9 (7.6) | 1 (14.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Treatment at time of sampling | ||||

| LMWH, n (%) | 20 (16.8) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Hydroxychloroquine, n (%) | 42 (35.3) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Aspirin, n (%) | 26 (21.8) | 3 (42.9) | 0** | 23 (88.5)*** |

| At admission | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| PaO2/FiO2, median (IQR) | 305 (231–357) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| ARDS, n (%) | 47 (39.5) | 2 (28.6) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Platelet count (×103/µl), median (IQR) | 215 (171–283) | 96 (35–165)*** | 180 (163–230) | 217 (178–234) |

| CRP (mg/dl), median (IQR) | 57 (17–138) | 220 (141–277)** | ‐ | ‐ |

| LDH (U/L), median (IQR) | 331 (247–437) | 723 (348–854)** | ‐ | ‐ |

| D‐dimer (µg/ml), median (IQR) | 0.9 (0.5–1.9) | 12 (9.0–25.0)*** | ‐ | ‐ |

| Hospitalization | ||||

| Hospitalized, n (%) | 97 (81.5) | 7 (100) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Length of stay (days)‡, median (IQR) | 10 (5–22) | 15 (5–20) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Transfer to ICU, n (%) | 13 (10.9) | 5 (71.4)*** | ‐ | ‐ |

| Death, n (%) | 23 (19.3) | 3 (42.9) | ‐ | ‐ |

Note

*p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001. Each control group (sepsis, HD, and CAD) was compared with the COVID‐19 cohort. ‡Calculated as the time from hospital admission to death, discharge, or time of statistical analysis for patients still hospitalized.

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; BMI, body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRP, C‐reactive protein; DM, diabetes mellitus; HD, healthy donor; HTN, arterial hypertension; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; ; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; LMWH, low‐molecular weight heparin; PaO2/FiO2, arterial oxygen partial pressure/fractional inspired oxygen.

2.2. Reagents and antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against CD61 (SZ21), CD62P (Thromb‐6), irrelevant IgG isotype control, Flow‐Count Fluorospheres, and Thrombofix were obtained from Beckman Coulter (Italy). mAbs against HMGB1 (clone 3E8) was from Biolegend (Italy). PGE1, thrombin receptor agonist peptide‐6 (TRAP‐6), and thrombin were obtained from Sigma (Italy). mAbs against CD147 clone HIM6 (Santa Cruz) was used for flow cytometry and clone 8D6 (GeneTex) in blocking experiments. Polyclonal blocking Abs against ACE2 was from Cell Signaling Technology. Polyclonal Abs against SARS‐CoV‐2 Nucleoprotein Antibody (40143‐R019) and against SARS‐CoV‐2 Spike antibody (40150‐R007) were obtained from Sino Biological (Italy). Recombinant SARS‐CoV‐2 Spike protein full‐length S1 subunit (aa Val16‐Gln690) (230–01101), the Arg319‐Phe541 S1 subunit fragment (230–20405), and the appropriate negative control (i.e., the culture supernatant of cells transfected with the empty expression vector) (230–20001) were from RayBiotech. SARS‐CoV‐2 pseudoviral particles (#MBS434275), SARS‐CoV‐2 pseudoviral particles, 614G (#MBS434278), and negative control pseudoviral particles (#MBS434280) were from MyBiosource. Vero E6 cells (Vero C1008; clone E6‐CRL‐1586) were from American Type Culture Collection (Italy). QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit was obtained from Qiagen. SuperScript First‐Strand Synthesis System, SYBR Green PCR Master Mix, and goat anti‐rabbit antibody Alexa Fluor 488 (A‐11008) were from Thermo Fisher (Italy). ELISA kit for soluble P‐selectin was obtained from Invitrogen (Italy).

2.3. Blood sampling and platelet analysis

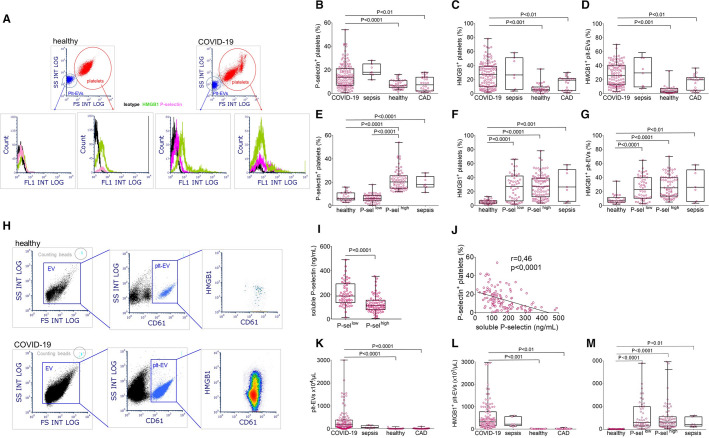

Venous blood were immediately fixed, stored at 4°C and platelet activation markers (P‐selectin, HMGB1, and von Willebrand factor [VWF] expression) were analyzed on a daily aligned Navios flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Milan, Italy).9., 10., 19. Quantification of platelet‐derived EVs (plt‐EVs) and assessment of HMGB1 expression were performed in platelet‐free plasma, as previously described.9., 10. The gating strategy is depicted in Figure 1 A, H.

FIGURE 1.

Platelet activation in patients with COVID‐19. Whole blood (A‐G) and platelet‐free plasma (H‐M) of COVID‐19 patients, patients with severe sepsis, sex‐ and age‐ matched healthy donors, and sex‐ and age‐matched patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) were analyzed. Platelets and platelet‐derived extracellular vesicles (plt‐EVs) were identified in the blood within the CD61+ population (threshold of acquisition) by their side scatter (y axis) and forward scatter (x axis) characteristics (A, gating strategy). Plt‐EVs were identified within the CD61+ population in platelet‐free plasma (H, gating strategy). Representative dot plots of a healthy donor and a patient with COVID‐19 are shown A and H). Panels B‐D depict the fraction of platelets expressing P‐selectin, expressing HMGB1 and the fraction of HMGB1+ plt‐EVs respectively. P‐sellow and P‐selhigh platelets were identified as those with a percentage of activated platelets within or higher than the confidential range observed in healthy donors. High or low P‐selectin expression is independent of the fraction of HMGB1+ platelets (F) or HMGB1+ plt‐EVs (G). In contrast, the plasma concentration of soluble P‐selectin was significantly higher in patients with P‐sellow platelets (I) and correlated with platelet P‐selectin surface expression (J). The concentration of plt‐EVs and of HMGB1+ plt‐EVs were both significantly higher in patients with COVID‐19 than in healthy volunteers or patients with CAD (K, L) and was independent of P‐selectin expression (M). Symbols depict individual observations in each subject and whiskies median, minimum, and maximum values. Statistical differences were determined by Kruskal‐Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple comparison test.

2.4. Cells and virus

Vero E6 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with nonessential amino acids, penicillin/streptomycin, Hepes buffer, and 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (FBS). A clinical isolate of SARS‐CoV‐2 (hCoV‐19/Italy/UniSR1/2020; GISAID accession n. EPI_ISL_413489) was obtained and propagated in Vero E6 cells.

2.5. Platelets

Venous blood was obtained from healthy volunteers who had not received any pharmacological treatment in the previous 10 days. Venous blood was drawn through a 19‐gauge butterfly needle. After discarding the first 3–5 ml, blood was carefully collected in tubes containing Na2EDTA. Samples were centrifuged at 150g, 10 min at 20°C, to obtain platelet‐rich plasma (PRP) to be used to isolate platelets as described.9., 10., 19., 20., 21. Briefly, the upper 2/3 of PRP was recovered and PGE1 (2.5 µM) was added before centrifugation at 800g for 15 min at 18° C (without break). Platelet pellets were washed twice with Hepes Tyrode buffer (129 mmol/L NaCl, 9.9 mmol/L NaHCO3, 2.8 mmol/L KCl, 0.8 mmol/L KH2PO4, 5.6 mmol/L dextrose, 10 mmol/L HEPES, MgCl2 1 mM, pH 7.4) containing Na EDTA (5 mM) and in the first wash PGE1 (2.5 µM) and resuspended with Hepes Tyrode buffer containing CaCl2 (1 mM). Platelets were counted with an automated blood cell counter (Sysmex). Contaminating leukocytes were consistently absent. The purity of the platelet preparations was routinely confirmed by flow cytometry using anti‐CD45 and anti‐CD61 mAbs (<1 CD45+ event out of 107 CD61+ events).

2.6. Invitro platelet response to SARS‐COV‐2

Platelets were stimulated with TRAP‐6 (25 µM) or thrombin (0.5 U/ml) as positive controls. Purified platelets (1 × 106/µl) from three healthy donors were incubated (1:1) for 1 h at 37°C in static conditions with clarified supernatants of Vero E6 cells (Vero C1008; clone E6–CRL‐1586; American Type Culture Collection) infected with a SARS‐COV‐2 clinical isolate (hCoV‐19/Italy/UniSR1/2020; GISAID accession no. EPI_ISL_413489) (3 × 106 50% tissue culture infective dose). The supernatant of uninfected Vero E6 cells was used as negative control. To determine platelet activation, samples were immediately fixed and analyzed by flow cytometry. To assess the virus platelet interaction, after centrifugation to remove unbound virus, platelets were washed twice with phosphate buffered saline‐EDTA and resuspended in complete medium supplemented with 2% FBS. At 24 and 48 h after infection, the platelets were centrifuged. The pellet was fixed using PFA, whereas the supernatants were stored at −80°C. Platelets were incubated with SARS‐CoV‐2 614D pseudoviral particles (PP), SARS‐CoV‐2 614G PP or negative control PP (1 × 106/µl, 1:1 platelet: PP ratio) for 1 h at 37°C in static conditions. Recombinant SARS‐CoV‐2 Spike protein S1 subunit (Val16‐Gln690) or the Spike S1 subunit fragment (Arg319‐Phe541) were used at a final concentration of 30 ng/µl. When indicated. platelets were challenged with the previous stimuli in the presence of an irrelevant antibody, of mAbs against CD147, or against ACE2, fixed with Thrombofix and analyzed by flow cytometry. The concentration of soluble P‐selectin was assessed by ELISA in supernatants that had been cleared by centrifugation at 10,000g for 3 min. Experiments were performed 3–6 times with different donors.

2.7. Electron microscopy

Platelets were isolated and stimulated as described previously and fixed in two steps: first with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 125 mM cacodylate buffer at 4°C for 30 min and then with 2% OsO4 in 125 mM cacodylate buffer for 1 h. Samples were then washed, dehydrated, and embedded in Epon. Conventional thin sections were collected on uncoated grids, stained with uranil and lead citrate, and examined on a Leo912 electron microscope.

2.8. Platelet aggregation and dense granules release

Platelet aggregation and dense granule release assays were performed by Lumi‐aggregometry (Chrono‐Log, Mascia Brunelli, Milan).22 PRP samples were challenged with recombinant SARS‐CoV‐2 Spike protein S1 subunit (Val16‐Gln690) or with the Spike S1 subunit Arg319‐Phe541 fragment at a final concentration of 30 ng/µl each. When indicated, challenge with the previous stimuli or with the platelet agonist, TRAP‐6 was carried out in the presence of an irrelevant antibody, of mAbs against CD147 or of mAbs against ACE2 (Table S1).

2.9. Infectivity assay and virus back titration

Vero E6 cells (4 × 105/well) were seeded into 96–96 good plates and infected with base 10 dilutions of the supernatants. After 1 h of adsorption at 37°C, the cell‐free virus was removed by centrifugation, and complete medium supplemented with 2% FBS was added to cells. After 72 h, cytopathic effect (CPE) was assessed using a scoring system (0 = uninfected; 0.5–2.5 = increasing number/area of plaques; 3 = all cells infected). Infection control (score 3) was set as 100% infection, uninfected cells (score 0) as 0% infection. The whole surface of the wells was considered for the analysis (5× magnification). All conditions were tested in triplicate. To verify the infectivity of the viral stock and the binding of SARS‐CoV‐2 to platelets, end‐point dilution (median tissue culture infective dose per milliliter) assays was performed using the unbound virus.

2.10. Viral RNA extraction and quantitative RT‐PCR

The viral RNA was purified from 50 µl of cell‐free culture supernatant (previously inactivated at 56°C for 30 min), using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit. The purified RNA was subsequently used to perform the synthesis of first‐strand complementary DNA, using the SuperScript First‐Strand Synthesis System for RT‐PCR (Thermo Fisher Scientific), following the manufacturer's instructions. RT‐PCR was performed to detect the complementary DNA. SYBR Green PCR Master Mix with the forward primer N2F (TTA CAA ACA TTG GCC GCA AA), the reverse primer N2R (GCG CGA CAT TCC GAA GAA) were used, at the following PCR conditions: 95°C for 2 min, 45 cycles of 95°C for 20 s, annealing at 55°C for 20 s, and elongation at 72°C for 30 s, followed by a final elongation at 72°C for 10 min. RT‐PCR was performed using the ABI‐PRISM 7900HT Fast Real Time instrument (Applied Biosystems) and optical‐grade 96‐well plates. Samples were run in duplicate, with a total volume of 20 µl.

2.11. Nucleic acid extraction, cDNA synthesis, and detection of SARS‐CoV‐2 subgenomic mRNA

The nucleic acid extraction, cDNA synthesis, and detection of SARS‐CoV‐2 subgenomic mRNA were performed by adapting described protocols.23 Briefly, 24 h after virus inoculation, platelets were collected and washed twice with phosphate buffered saline. Nucleic acids were extracted using Trizol following the manufacturer's instructions and purified RNA was reverse‐transcribed by using SuperScript IV and a SARS‐CoV‐2 specific primer (WHSA‐29950R: 5′ ‐TCTCCTAAGAAGCTATTAAAAT‐3′ ). The amplification was performed using Platinum Taq Polymerase with SARS‐CoV‐2 specific primer (WHSA‐0025F: 5′‐CCAACCAACTTTCGATCTCTTGTA‐3′ and WHSA‐29925R: 5′‐ATGGGGATAGCACTACTAAAATTA‐3′). The PCR products were then analyzed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and sequenced. Experiments were performed using platelets derived from three to five independent donors in duplicate. Platelets derived from the same donors not exposed to SARS‐CoV‐2 served as a negative control.

2.12. Immunofluorescence

Fixed platelets were introduced to Shandon Cytospin II (Shandon, Pittsburgh, PA, USA), permeabilized with Triton X‐100 (0.5%) and stained with anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 Nucleoprotein Antibody (40143‐R019, Sino Biological) or anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 Spike Antibody (40150‐R007, Sino Biological). A goat anti‐rabbit antibody Alexa Fluor 488 (A‐11008, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used as second step reagent.

2.13. Statistics

Dichotomous variables were expressed as absolute frequencies (percentages), and continuous variables as medians (interquartile range). When indicated, continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD. Comparisons for categorical variables between groups were performed using the chi‐squared test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. Kruskal‐Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple comparison test or Mann‐Whitney U was used to compare continuous variables between groups. Length of stay was calculated as the time from hospital admission to death, discharge, or time of statistical analysis for still hospitalized patients. Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) was defined according to Berlin definition.24 The previously described25 6‐point ordinal scale for clinical status was used as a marker of COVID‐19 severity. The worst category reached from hospital admission to discharge or death of the 6‐point scale was used as the primary outcome.26 Univariate and multivariate log‐linear Poisson regression analysis was used to estimate the impact of individual variables on the primary outcome. Variables that emerged as significant (with a p value < 0.01) predictors of the primary outcome at univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis. Missing data were not imputed. For the virus/platelet interactions, CPE observed were normalized to corresponding virus infection control. Quantitative RT‐PCR results were analyzed using cycle threshold values obtained for experimental settings. Then, two‐way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple comparisons test or Sidak's multiple comparisons test were performed for the evaluation of CPE scoring and cycle threshold differences, respectively (GraphPad Prism 8). R statistical package (version 4.0.0, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was used, with a two‐sided significance level set at p < 0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Widespread activation of platelets in the blood of COVID‐19 patients

Blood was retrieved from 119 patients with COVID‐19 admitted at the emergency department of a university hospital in Milan, Italy, between March 18 and May 5, 2020. To assess markers of platelet activation, samples were immediately fixed and analyzed. Table 1 summarizes the main clinical and laboratory features of patients and controls. Compared with control populations, such as healthy subjects and patients with CAD, platelets of COVID‐19 patients expressed significantly higher levels of P‐selectin (Figure 1B) and of the prototype endogenous inflammatory signal, HMGB1 (Figure 1C), markers that reflect platelet activation regardless of the original stimulus (Table S2). After activation, platelets generate and release EVs (Table S2).

Plt‐EVs accumulated in the plasma of patients with COVID‐19. Plt‐EVs and the fraction of plt‐EVs expressing HMGB1, which play a direct role in pulmonary microvascular activation and inflammation,9., 10. were significantly more concentrated in the blood of COVID‐19 patients than in the blood of control subjects (Figure 1D, M). Therefore, three independent markers, which are associated with platelet activation in patients with sepsis (Figure 1B‐D), revealed platelet activation in the blood of COVID‐19 patients.

Of interest, P‐selectin expression was bimodal and 53 (45%) patients had a level of P‐selectin on activated platelets similar to that of controls (Figure 1, E) regardless of the fact that they quantitatively expressed high levels of HMGB1 and had high levels of plt‐EVs expressing HMGB1 (Figure 1E,G,M). This feature could be specific for COVID‐19 because activated platelets expressing low levels of P‐selectin were not detectable in patients with severe sepsis (Figure 1E), a condition in which different pathways are involved in platelet activation.

Defective release of the content of α granules, where P‐selectin is stored in platelets at rest, or accelerated shedding of P‐selectin could contribute. The first event is unlikely, as other α granule components such as VWF were depleted in platelets of COVID‐19 patients regardless of the extent of P‐selectin membrane expression (Table 2 ). In support of the second mechanism, various proteases cleave P‐selectin, which is for example released as a soluble molecule from activated platelets.27., 28. In agreement, the concentration of soluble P‐selectin was significantly higher in the plasma of patients with activated platelets expressing low levels of P‐selectin (Figure 1I,J).

TABLE 2.

Characteristics on sampling of patients with different expression of platelet P‐selectin

| COVID‐19 patients |

Sepsis | HD | CAD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P‐selectinlow | P‐selectinhigh | ||||

| N | 53 | 66 | 7 | 36 | 26 |

| Platelet VWF content, mean ± SD | 326.0 ± 15.9 | 330.0 ± 5.9 | 396.4 ± 130.9 | 585.0 ± 50.0 | 543.1 ± 51.6 |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 62 (53–76) | 58 (49–68) | 79 (67–82) | 54 (47–59) | 62 (57–69) |

| Female, n (%) | 22 (41.5) | 28 (42.4) | 5 (71.4) | 19 (52.8) | 3 (11.5) |

| BMI (kg/cm2), median (IQR) | 26 (25–30) | 28 (25–31) | ‐ | 24 (23–25) | 26 (24–29) |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| HTN, n (%) | 22 (41.5) | 19 (28.8) | 2 (28.6) | 0 | 18 (69.2) |

| CAD, n (%) | 6 (11.3) | 4 (6.1) | 3 (42.9) | 0 | 26 (100) |

| DM, n (%) | 11 (20.8) | 7 (10.6) | 3 (42.9) | 0 | 2 (7.7) |

| COPD, n (%) | 4 (7.5) | 2 (3.0) | 2 (28.6) | 0 | 0 |

| CKD, n (%) | 5 (9.4) | 3 (4.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Active neoplasia, n (%) | 4 (7.5) | 3 (4.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Autoimmune disease, n (%) | 6 (11.3) | 3 (4.5) | 1 (14.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Treatment at time of sampling | |||||

| LMWH, n (%) | 8 (15.1) | 12 (18.2) | 0 | ‐ | ‐ |

| Hydroxychloroquine, n (%) | 16 (30.2) | 26 (39.4) | 0 | ‐ | ‐ |

| Aspirin, n (%) | 14 (26.4) | 12 (18.2) | 3 (43) | 0 | 23 (88.5) |

| At admission | |||||

| PaO2/FiO2, median (IQR) | 302 (168–394) | 308 (234–346) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| ARDS at admission, n (%) | 20 (30.7) | 27 (40.9) | 1 (14.3) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Platelet count (×103/µl), | |||||

| median (IQR) | 198 (162–241) | 230 (181–316) *† | 96 (35–165) | 180 (163–230) | 217 (178–234) |

| CRP (mg/dL), median (IQR) | 49 (17–155) | 58 (18–132) | 220 (141–277) | ‐ | ‐ |

| LDH (U/L), median (IQR) | 344 (241–479) | 317 (256–415) | 723 (348–854) | ‐ | ‐ |

| D‐dimer (µg/ml), median (IQR) | 1.1 (0.5–3.2) | 0.7 (0.4–1.6) | 12 (9.0–25.0) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Hospitalization | |||||

| Hospitalized, n (%) | 41 (77.4) | 56 (84.8) | 7 (100) | ||

| Length of stay (days)a, * | |||||

| median (IQR) | 10 (5–30) | 11 (5–21) | 15 (5–20) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Transfer to ICU, n (%) | 7 (13.2) | 6 (9.1) | 5 (71.4) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Death, n (%) | 12 (22.6) | 11 (16.7) | 3 (42.9) | ‐ | ‐ |

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; BMI, body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRP, C‐reactive protein; DM, diabetes mellitus; HD, healthy donors; HTN, arterial hypertension; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; LMWH, low‐molecular weight heparin; PaO2/FiO2, arterial oxygen partial pressure/fractional inspired oxygen; VWF, von Willebrand factor.

b Compared with P‐selectin low COVID‐19 patients. von Willebrand factor (VWF) was expressed as mean ± SD of arbitrary units of mean fluorescence intensity.

Calculated as the time from hospital admission to death: discharge or time of statistical analysis for still hospitalized patients.

p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001.

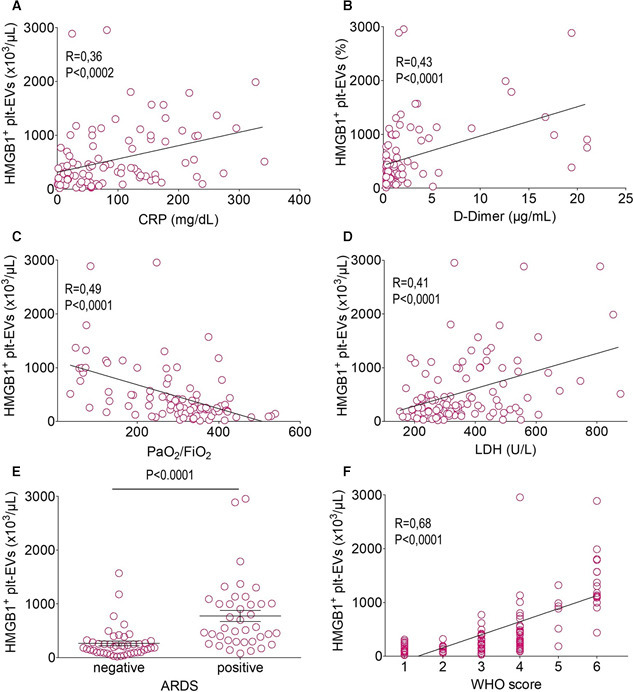

HMGB1+ plt‐EVs concentration was significantly correlated with that of CRP (Figure 2 A), D‐dimer (Figure 2B), with the extent of hypoxia (Figure 2C), and with lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (Figure 2D). Moreover, they were at admission more abundant in the plasma of patients that eventually developed ARDS (Figure 2E). To verify whether HMGB1+ plt‐EVs level at hospital admission could inform on the eventual clinical course, we relied on an ordinal scale that measures the severity of COVID‐19 over time, considering the worst category reached by each patient. The concentration of HMGB1+ plt‐EVs, but not the concentration of plt‐EVs per se, emerged as a strong predictor of clinical outcome on univariate analysis (p < 0.001, Table 3 , Figure 2F) along with age, comorbidities, extent of hypoxia and concentrations of CRP, LDH, and D‐dimer at hospital admission (Table 3). When adjusted for the previously mentioned predictors, the concentration of HMGB1+ plt‐EVs survived as independent predictor of the clinical outcome on multivariate analysis (p < 0.001, Table 3 and Figure 2F).

FIGURE 2.

HMGB1+ plt‐EVs concentration is associated with COVID‐19 severity and predicts clinical outcomes. The concentration of HMGB1+ plt‐EVs correlates with the concentration of C‐reactive protein (CRP; A), of D‐dimer (B), with hypoxia as reflected by the arterial oxygen partial pressure/fractional inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2, C) and with the concentration of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH, D) while being significantly higher in patients who will develop acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (E) and who will experience more severe disease, as reflected by the maximum score achieved using the World Health Organization ordinal scale as a surrogate for clinical deterioration (F). Symbols depict individual observations in each subject. Statistical differences were determined as described in the Methods.

TABLE 3.

Parameters predicting the worst World Health Organization score reached during COVID‐19 (n = 119)

| Univariate |

Multivariate |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| coefficient | SE | p value | coefficient | SE | p value | |

| Age (years) | 0.017 | 0.0026 | <0.001 | 0.0092 | 0.00025 | <0.001 |

| Female | −0.071 | 0.089 | 0.42 | |||

| BMI (kg/cm2) | 0.0066 | 0.011 | 0.54 | |||

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| HTN | 0.31 | 0.084 | <0.001 | −0.043 | −0.071 | 0.54 |

| CAD | 0.30 | 0.14 | 0.030 | |||

| DM | 0.41 | 0.10 | <0.001 | −0.060 | −0.092 | 0.52 |

| COPD | 0.34 | 0.17 | 0.047 | |||

| CKD | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.28 | |||

| Active neoplasia | 0.47 | 0.15 | 0.0017 | 0.37 | 0.11 | <0.001 |

| Autoimmune disease | −0.032 | 0.16 | 0.85 | |||

| At admission | ||||||

| PaO2/FiO2 | −0.0025 | 0.00030 | <0.001 | −0.0011 | 0.00035 | 0.0022 |

| CRP (mg/dl) | 0.0027 | 0.00039 | <0.001 | 0.00072 | 0.00037 | 0.054 |

| LDH (U/L) | 0.0014 | 0.00022 | <0.001 | 0.00024 | 0.00022 | 0.29 |

| D‐dimer (µg/ml) | 0.027 | 0.0072 | <0.001 | −0.0099 | 0.0062 | 0.11 |

| P selectin+ platelets (%) | 0.0041 | 0.0041 | 0.32 | |||

| Soluble P‐selectin (ng/ml) | 0.000013 | 0.00046 | 0.97 | |||

| HMGB1+ platelets (%) | 0.0014 | 0.0024 | 0.56 | |||

| HMGB1+ plt‐EV (%) | 0.0020 | 0.0026 | 0.45 | |||

| HMGB1+ plt‐EV (x103/µl) | 0.00039 | 0.000047 | <0.001 | 0.00017 | 0.000048 | <0.001 |

BMI, body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease;

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRP, C‐reactive protein; DM, diabetes mellitus; HMGB1, high mobility group box 1; HTN, arterial hypertension; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PaO2/FiO2, arterial oxygen partial pressure/fractional inspired oxygen; plt‐EV, platelet extracellular vesicles; SE, standard error.

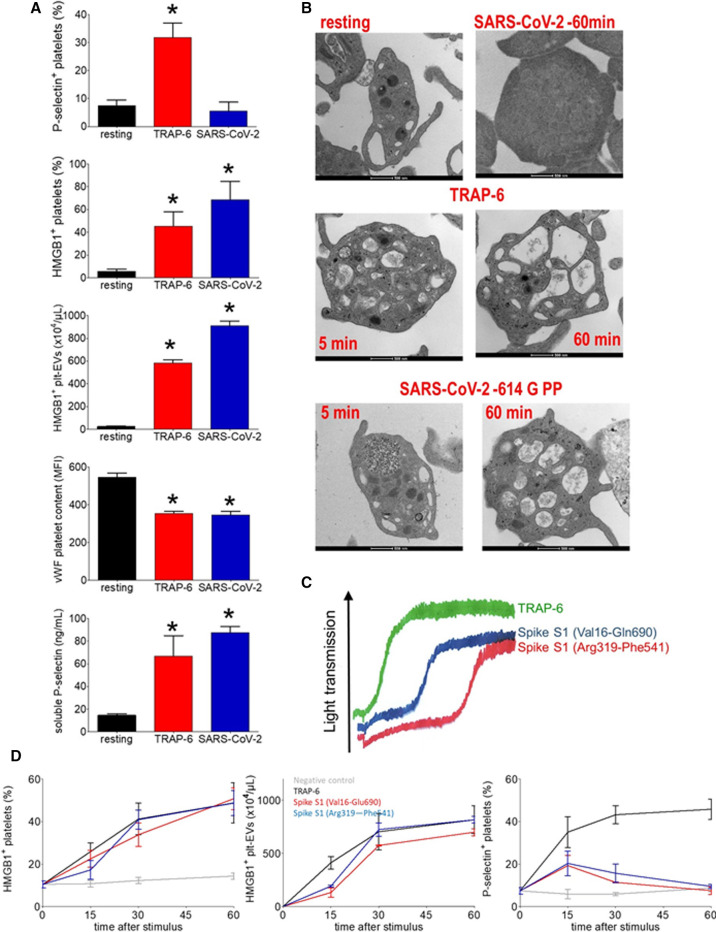

3.2. SARS‐CoV‐2 activates human platelets

We combined SARS‐CoV‐2 and human platelets (106/µl) for an hour at 37°C. Platelets challenged with SARS‐CoV‐2 underwent activation, as demonstrated by HMGB1 expression, generation of HMGB1+ plt‐EVs, depletion of platelet VWF (Figure 3 A). Electron microscopy confirmed the activation of platelets, which acquired an approximately spherical shape and lost α and dense granules. This was associated with the fusion of the open canalicular and dense tubular systems, the centralization of the organelles and the peripheral arrangement of the mitochondria (Figure 3B). Platelet activation was replicated using pseudoviral particles (PP) expressing SARS‐CoV‐2 Spike protein (Figure 3B). Platelets were activated to a similar extent by Spike expressing pseudovirions, by the full‐length Spike S1 subunit protein (Val16‐Gln690) or by the S1 fragment containing the receptor‐binding domain (Arg319‐Phe541). Recombinant S1 proteins also effectively induced platelet aggregation and release reaction, with a lag‐time of approximatively 5 min (5.1 ± 0.8 min for Spike S1 Val16‐Glu690 and 4.3 ± 1.0 min for Spike S1 Arg319‐Phe541) (Figure 3C and Figure 4 B).

FIGURE 3.

SARS‐CoV‐2 activates platelets. Purified platelets underwent activation after challenge with SARS‐CoV‐2 clinical isolates (SARS‐CoV‐2) or TRAP‐6, as reflected by platelet HMGB1 expression, the concentration of released HMGB1+ plt‐EVs, the VWF platelet content, the P‐selectin expression, and the concentration of released soluble P‐selectin in the supernatant (A). Representative morphological electron microscopies of platelet challenged with TRAP‐6, with SARS‐CoV‐2 or with SARS‐CoV‐2 614G pseudovirus particles (B). Platelet aggregation after challenge with TRAP‐6, recombinant Spike S1 proteins Val16‐Glu 690, and Arg 319‐Phe 541 (C). Time course (x axis, minutes) of platelet response as reflected by HMGB1 expression, concentration of released HMGB1+ plt‐EVs, and platelet P‐selectin expression after challenge with TRAP‐6, with recombinant Spike S1 proteins Val16‐Glu690 and Arg319‐Phe541 or with the culture supernatant of cells transfected with the empty expression vector as negative control (D). *p< 0.0001, significantly different from resting platelets. Statistical differences were determined as described in the Methods.

FIGURE 4.

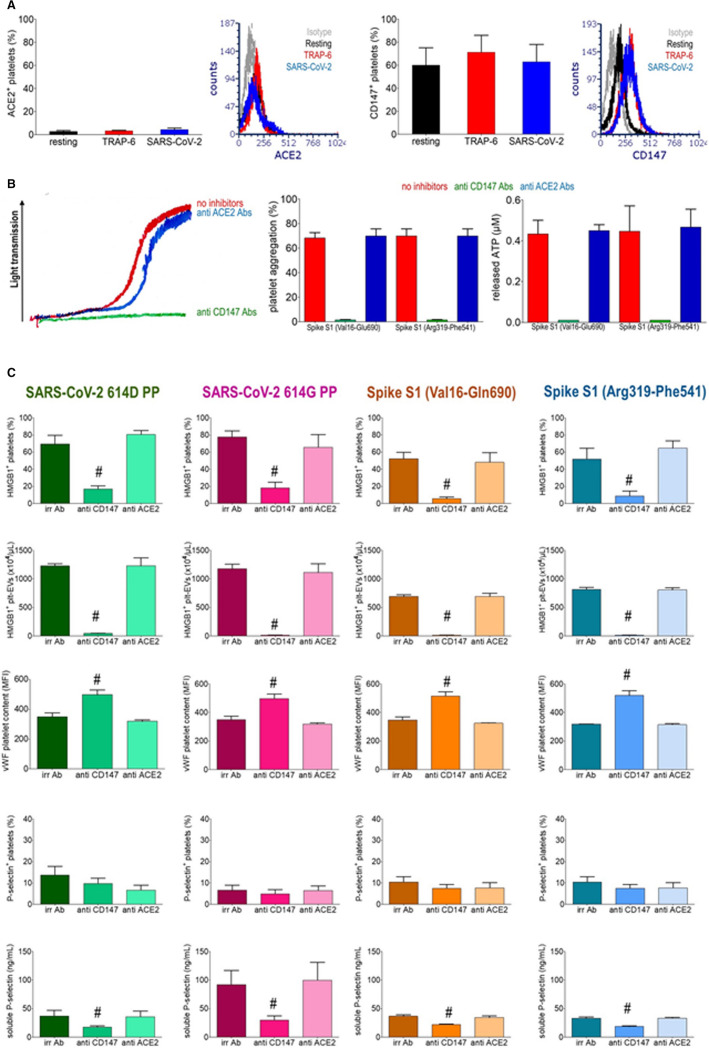

SARS‐CoV‐2 activates platelets via CD147. Human platelets surface expression of ACE2 and CD147 at rest or after challenge with TRAP‐6 or a SARS‐CoV‐2 clinical isolate (SARS‐CoV‐2). Histograms represent the % of platelets resting or stimulated with TRAP‐6 or with SARS‐CoV‐2 expressing ACE2 or CD147 (mean ± SD) (A). ATP aggregation and release from dense granules monitored by lumi‐aggregometry in platelet‐rich plasma after challenge with TRAP‐6, Spike S1 Val16‐Glu690, or Arg319‐Phe541 recombinant proteins in the presence of an irrelevant mAbs (no inhibitors), of anti‐CD147 or of anti‐ACE2 Abs. Representative traces and quantification of maximal aggregation and ATP release are reported (B). Activation of platelets, as reflected by platelet HMGB1 expression, the concentration of released HMGB1+ plt‐EVs, the VWF platelet content, the P‐selectin expression and by the concentration of released soluble P‐selectin were assessed after challenge with SARS‐CoV‐2 614D pseudoviral particles (PP), SARS‐CoV‐2 614G PP, Spike S1 Val16‐Glu690, or Spike S1 Arg319‐Phe541 recombinant proteins for 1 hr in the presence of irrelevant Abs (irr ab), of anti‐CD147 or anti‐ACE2 Abs. #p< 0.001, significantly different from platelets stimulated in the presence of irrelevant Abs or of anti‐ACE2 Abs, determined by Kruskal‐Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple comparison test.

The time course of HMGB1 expression and of HMGB1+ Plt‐EVs release indicates that full platelet response occurs after 60 min (Figure 3D). The kinetics of P‐selectin expression is different because it increases in the first phase of the incubation to subsequently abate (Figure 3D), a pattern that might be compatible with eventual shedding of the molecule. In support, platelets challenged with purified SARS‐COV‐2 expressed relatively low amounts of P‐selectin on the plasma membrane after 60 min, but soluble P‐selectin accumulated at that time in the extracellular environment (Figure 3A).

ACE2, the best characterized receptor for SARS‐CoV‐2, is expressed in a fraction of human platelets only (2.7 ± 1.5% in platelets at rest, 3.3 ± 0.6% in activated platelets, Figure 4A). CD147, a SARS‐CoV‐2 putative coreceptor,26 is constitutively expressed on a large fraction of platelets from healthy donors (60 ± 18.5% in platelets at rest, 71.3 ± 18.1% in activated platelets, Figure 4A). Platelet activation induced by SARS‐CoV‐2 PPs or Spike S1 recombinant proteins, assessed by measuring platelet expression of HMGB1, release of EVs and depletion of VWF, aggregation and release reaction abated in the presence of antibodies blocking the CD147 receptor, while antibodies that block ACE2 were ineffective (Figure 4,B, C). The effect was specific, since CD147 blockade did not influence TRAP‐6‐elicited platelet activation (Table S1). The fraction of platelets expressing P‐selectin in this system did not reflect the extent of activation in response to viral stimuli, despite the effective depletion of the alpha granules reflected by the VWF content. This discrepancy was probably due to the release of the soluble molecule into the environment. In agreement, the concentration of soluble P selectin in the supernatant of Spike‐stimulated platelets was increased (Figure 4C). This event was significantly inhibited by blocking the CD147 receptor (Figure 4C).

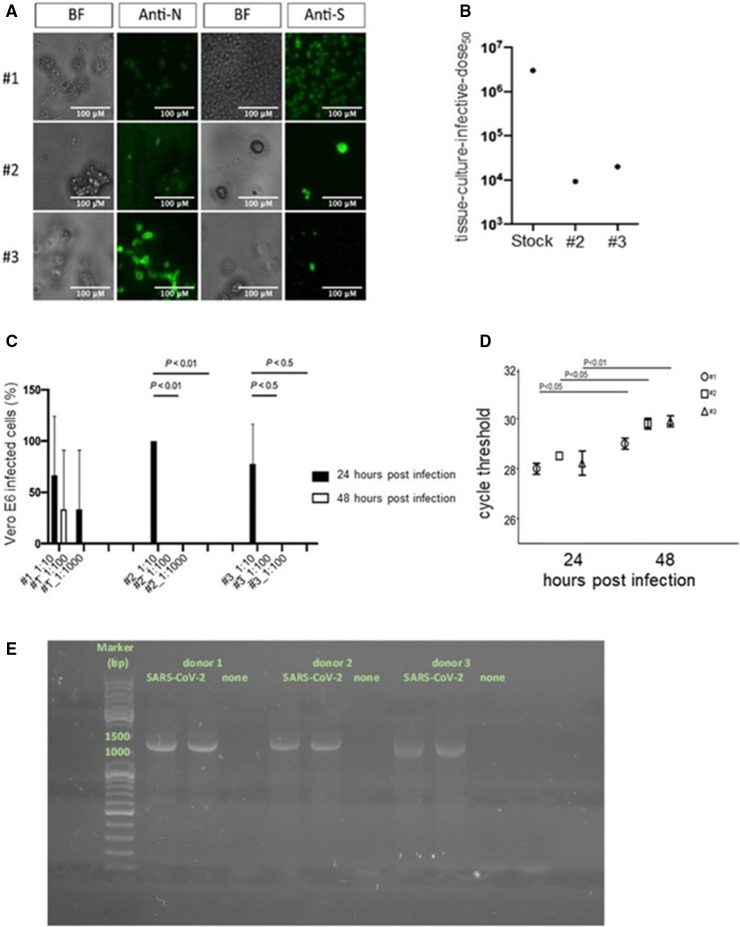

3.3. SARS‐CoV‐2 does not replicate in human platelets

The interaction between the SARS‐CoV‐2 protein Spike and platelets suggests the possibility that the virus infects them, even if we did not detect virus‐like particles within platelets exposed to virus at analysis by electron microscopy (Figure 3B). Back‐titration assays of unbound virus, performed by infecting Vero E6 cells with supernatants retrieved after 1h of coincubation of platelets with a definite amount of SARS‐CoV‐2, revealed that unbound virus titers were significantly lower compared to virus control, supporting the physical interaction of the virus with the platelets (Figure 5 A). To assess the possible replication of SARS‐CoV‐2, platelets were washed after virus adsorption and incubated up to 48 h. Supernatants were collected and assessed for their ability to infect Vero E6 cells. Low levels of infectious virions were detected at 24 h and no infection of Vero E6 cells was revealed at 48 h (Figure 5B). Virus‐specific RT‐PCR analysis revealed increased cycle threshold values at 48 h compared with 24 h, thus underlining that no increase of viral RNA occurs during virus/platelets coincubation (Figure 5C). The subgenomic mRNA of SARS‐CoV‐2 was evaluated 24 h after challenge. The PCR products of agarose gel electrophoresis of the platelets exposed to SARS‐CoV‐2 revealed a single band of approximately 1200 bp, corresponding to the length of the nucleoprotein transcript (Figure 5D). Sanger sequencing analysis confirmed that the PCR products correspond to SARS‐CoV‐2 N. The results confirm that SARS‐CoV‐2 enters platelets. However, no viral progeny was detected, as reflected by the lack of other subgenomic mRNAs, thus confirming the absence of productive SARS‐CoV‐2 infection on platelets in these experimental conditions (Figure 5E).

FIGURE 5.

SARS‐CoV‐2 interacts with but does not productively infect platelets. Bright‐field (BF) microscopy and immunofluorescence of platelets 48 h after challenge with a SARS‐CoV‐2 clinical isolate (SARS‐CoV‐2) stained with anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 Nucleoprotein Abs (Anti‐N) or anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 Spike Abs (Anti‐S). 20× magnification, scale bar 100 µm (A). Back‐titration performed on the unbound virus from donors 2 and 3, compared with viral stock used for the infection protocol (B). Cytopathic effect was assessed on Vero E6 cells using a scoring system to evaluate infectivity of platelets supernatants collected at 24 and 48 h postchallenge. Mean values for all experimental replicates and SD are reported with error bars (C). Quantitative RT‐PCR on supernatants collected from platelets challenged with the virus of the three donors, at 24 and 48 h. Cycle threshold levels, represented on the y axis, are inversely proportional to the amount of target nucleic acid in the sample (the lower the cycle threshold level the greater the amount of virus within the supernatant). Mean values for all experimental replicates, tested each one in duplicate in quantitative RT‐PCR, and SD are reported with error bars (D). Agarose gel electrophoresis PCR products of platelets treated with the clarified supernatants of infected (SARS‐CoV‐2) or uninfected Vero E6 cells (none) (E). [Correction added on November 25, 2021, after first online publication: Figure 5 has been updated in this version.]

4. DISCUSSION

Platelets are guardians of vascular integrity. They vastly outnumber leukocytes in the blood and constantly patrol the vasculature for the integrity of the endothelial layer and the presence of infectious agents. Platelets express receptors specialized in microbe recognition.29 Some of these receptors have been implicated in the recognition and interaction of platelets with viruses they encounter in the circulation, including DC‐SIGN, platelet glycoprotein VI, and C‐type lectin‐like receptor 2 CLEC‐2, GPVI.5

The cause of the activation of platelets in vivo in patients with COVID‐19 remains to be determined. The generation of thrombin associated to the coagulopathy, the production of cytokines and the activation of endothelial linings, in particular at the level of the lung microvasculature30 could all play a role. The results of this study suggest that platelets interact and undergo activation when challenged with SARS‐CoV‐2, even if they are not productively infected by the virus. Such an interaction could contribute to the vast activation of platelets found by us and others in patients with COVID‐19.11., 12., 13., 14., 15., 31.

The best characterized receptor for SARS‐CoV‐2 is the ACE2, which is required for the infection of most nucleated cells. However, the extent of the expression and the physiological relevance of ACE2 in human platelets are controversial.11., 17., 18., 32. CD147, a receptor constitutively expressed on a large fraction of human platelets, has been described as a coreceptor involved in SARS‐CoV‐2 infection of epithelial cells in vitro and in vivo.26 However, other groups failed to identify a direct role of CD147 in Spike‐mediated infection of epithelial cells,33., 34. suggesting that it may act more as an attachment cofactor than as a bona fide receptor needed for virus entry.35 Our results indicate that platelet preparations that have been exposed to SARS‐CoV‐2 contain only traces of the virus, which has not actively replicated, suggesting that the receptor is not sufficient for platelet infection. In support, a limited presence of SARS‐CoV‐2 in platelets of patients with COVID‐19 has been reported by others11., 13., 16., 36. and microvesicles generated by virus‐activated platelets might per se represent the Trojan horse the virus relies on to enter bystander platelets.16

CD147 is a multifunctional membrane glycoprotein with various binding partners.37 In addition to being expressed by human platelets, it is up‐regulated in activated platelets and in turn contributes, after involvement, to platelet degranulation,38., 39. at least in part via phosphoinositid‐3‐kinase/Akt‐signaling events. Interestingly, ERK1/2, p38, and eIF4E phosphorylation is significantly upregulated in platelets from patients with severe COVID‐19.11 Further studies are necessary to dissect the intracellular signaling events associated with the SARS‐CoV‐2 elicited, CD147‐mediated platelet activation. Overall, CD147 represents a strong candidate as a moiety necessary for the platelet activation caused by the interaction of SARS‐CoV‐2.18

The role of platelets in intravascular immunity includes, on meeting a microbe in the circulation, the deployment of mechanisms to prevent its dissemination, including its containment within thrombi. The process, referred to as immunothrombosis, depends on the ability of platelets to trigger the generation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs),29 via presentation of their own HMGB1.19., 40. Strongly supporting the role of immunothrombosis in COVID‐19, the presence of thrombi containing NETs associated with platelets and fibrin in the pulmonary, renal, and cardiac microcirculation of patients with COVID‐19 has been reported.41., 42., 43., 44. Microthrombosis was related to the extent of neutrophil and platelet activation and interaction pattern in the blood, and to both ARDS and systemic hypercoagulability.41., 42., 43., 44.

Respiratory tract epithelial cells are a primary target of SARS‐CoV‐2 and the main clinical syndrome of COVID‐19 is one of the upper and lower respiratory tract infections. Although viremia in the early stages of COVID‐19's natural history is limited,45 systemic spread of the virus through the bloodstream to extrapulmonary sites occurs and SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA has been detected in the blood of hospitalized patients, most frequently in patients in intensive care units.46., 47. SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA levels consistently correlated with COVID‐19 severity46., 47. and with the presence of intact SARS‐CoV‐2 virions.48 Therefore, the blood and possibly the pulmonary microcirculation could represent a privileged meeting point for the virus and platelets.

Platelets undergo early activation in the context of other infections in which the viral load in the blood is limited, such as human influenza. In these patients, platelet activation has been associated with lung involvement.49 In the case of human influenza, Koupenova et al. have shown influenza virus engulfment by platelets, which results in the activation of neutrophils via a pathway that involves the complement cascade.50 We did not find phagocytosis of SARS‐CoV‐2, possibly highlighting the different systems used by platelets to recognize the two viruses. In both cases, platelets undergo substantial activation and a role for complement in COVID‐19 has been convincingly proposed.41., 51. Further studies are warranted to verify whether platelet and neutrophil activation and complement involvement are causally related in COVID‐19.

In this study, we observe widespread activation of platelets in patients with COVID‐19, which correlates with activation of the coagulation cascade, with exposure of HMGB1 on the platelet membrane and with generation of HMGB1+ plt‐EVs, which are bioactive elements that activate endothelial cells, favor the generation of NETs and cause lung inflammation.9., 10. Our data support the rising COVID‐19 model depicting platelet activation and coagulopathy as interconnected events via the recruitment of inflammatory leukocytes. Of importance, there is a significant association between the extent of platelet activation at admission and disease outcomes (this report and previous work11., 12., 13., 14., 15., 31.), suggesting that platelet activation might be a target for molecular intervention in COVID‐19.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Norma Maugeri and Angelo A. Manfredi defined the experimental strategy, carried out experiments, analyzed the results, and wrote the manuscript. Rebecca De Lorenzo organized the clinical database, carried out statistical analyses, and discussed the manuscript. Nicola Clementi, Roberta A. Diotti, Elena Criscuolo, Massimo Clementi, and Nicasio Mancini designed and carried out the SARS‐CoV‐2/platelet interaction experiments, analyzed the results, and corrected the manuscript. Cosmo Godino contributed to the definition and recruitment of control groups. Cristina Tresoldi organized the patients sample processing and biobanking. Chiara Bonini and Fabio Ciceri discussed the experimental strategy and corrected the manuscript. Patrizia Rovere‐Querini supervised the patients recruitment and clinical data collection at hospitalization and after discharge, discussed the experimental strategy, and corrected the manuscript. Bio Angels for COVID‐BioB Study Group: Nicola Farina, Luigi De Filippo, Marco Battista, Domenico Grosso, Francesca Gorgoni, Carlo Di Biase, Alessio Grazioli Moretti, Lucio Granata, Filippo Bonaldi, Giulia Bettinelli, Elena Delmastro, Damiano Salvato, Chiara Maggioni, Giulia Magni, Monica Avino, Paolo Betti, Romina Bucci, Iulia Dumoa, Simona Bossolasco, and Federica Morselli.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a COVID‐19 program project grant from the IRCCS San Raffaele Hospital, grant COVID‐2020‐12371617 from the Italian Ministero della Salute Cellnex (ACT4Covid), and the EHA grant on COVID‐19. The authors thank Dr. Mariangela Scavone for her kind support to the aggregation studies, Dr. Gabriella Scarlatti and Lucia Lopalco for generously providing key reagents, Dr. Maria Carla Panzeri for the excellent electron microscopy studies that have been carried out in ALEMBIC, an advanced microscopy laboratory established by the San Raffaele Scientific Institute and the Vita‐Salute San Raffaele University; FRACTAL, the flow cytometry facility of the San Raffaele Institute; the Institutional Biobank, whose support made it possible to carry out these studies in a very difficult situation for the Institution and for the country. [Correction added on November 25, 2021, after first online publication: The grant `Cellnex (ACT4Covid)' has been included in the first sentence of the Acknowledgments section.]

EHA grant on COVID‐19

Ministero della SaluteCOVID‐2020‐12371617

COVID‐19 program project grant from the IRCCS San Raffaele Hospital

Supporting Information

Table S1‐S2

REFERENCES

- 1.Ciceri F., Castagna A., Rovere‐Querini P., et al. Early predictors of clinical outcomes of COVID‐19 outbreak in Milan, Italy. Clin Immunol. 2020;217:108509. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levi M., Thachil J., Iba T., Levy J.H. Coagulation abnormalities and thrombosis in patients with COVID‐19. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7:e438–e440. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30145-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al‐Samkari H., Karp Leaf R.S., Dzik W.H., et al. COVID and coagulation: bleeding and thrombotic manifestations of SARS‐CoV2 infection. Blood. 2020;136(4):489–500. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020006520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banerjee M., Huang Y., Joshi S., et al. Platelets endocytose viral particles and are activated via TLR (toll‐like receptor) signaling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40(7):1635–1650. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.314180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simon A.Y., Sutherland M.R., Pryzdial E.L. Dengue virus binding and replication by platelets. Blood. 2015;126:378–385. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-09-598029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen L., Yu J., He W., et al. subjects with COVID‐19. Leukemia. 2020;34(8):2173–2183. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-0911-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liao D., Zhou F., Luo L., et al. Haematological characteristics and risk factors in the classification and prognosis evaluation of COVID‐19: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(9):e671–e678. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30217-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boudreau L.H., Duchez A.C., Cloutier N., et al. Platelets release mitochondria serving as substrate for bactericidal group IIA‐secreted phospholipase A2 to promote inflammation. Blood. 2014;124:2173–2183. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-573543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maugeri N., Capobianco A., Rovere‐Querini P., et al. Platelet microparticles sustain autophagy‐associated activation of neutrophils in systemic sclerosis. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10(451):eaao3089. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aao3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manfredi A.A., Ramirez G.A., Godino C., et al. Platelet phagocytosis via PSGL1 and accumulation of microparticles in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021 doi: 10.1002/art.41926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manne B.K., Denorme F., Middleton E.A., et al. Platelet gene expression and function in COVID‐19 patients. Blood. 2020;136(11):1317–1329. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020007214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hottz E.D., Azevedo‐Quintanilha I.G., Palhinha L., et al. Platelet activation and platelet‐monocyte aggregates formation trigger tissue factor expression in severe COVID‐19 patients. Blood. 2020;136(11):1330–1341. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020007252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zaid Y., Puhm F., Allaeys I., et al. Platelets can associate with SARS‐Cov‐2 RNA and are hyperactivated in COVID‐19. Circ Res. 2020;127(11):1404–1418. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langnau C., Rohlfing A.K., Gekeler S., et al. Platelet activation and plasma levels of furin are associated with prognosis of patients with coronary artery disease and COVID‐19. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2021;41:2080–2096. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.315698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taus F., Salvagno G., Cane S., et al. Platelets promote thromboinflammation in SARS‐CoV‐2 pneumonia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40:2975–2989. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.315175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koupenova M., Corkrey H.A., Vitseva O., et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 initiates programmed cell death in platelets. Circ Res. 2021;129:631–646. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.319117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen S., Zhang J., Fang Y., et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 interacts with platelets and megakaryocytes via ACE2‐independent mechanism. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14:72. doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01082-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell R.A., Boilard E., Rondina M.T. Is there a role for the ACE2 receptor in SARS‐CoV‐2 interactions with platelets? J Thromb Haemost. 2021;19:46–50. doi: 10.1111/jth.15156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maugeri N., Campana L., Gavina M., et al. Activated platelets present high mobility group box 1 to neutrophils, inducing autophagy and promoting the extrusion of neutrophil extracellular traps. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12:2074–2088. doi: 10.1111/jth.12710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maugeri N., Malato S., Femia E.A., et al. Clearance of circulating activated platelets in polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia. Blood. 2011;118:3359–3366. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-337337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maugeri N., Rovere‐Querini P., Baldini M., et al. Oxidative stress elicits platelet/leukocyte inflammatory interactions via HMGB1: a candidate for microvessel injury in sytemic sclerosis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:1060–1074. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cattaneo M. Light transmission aggregometry and ATP release for the diagnostic assessment of platelet function. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2009;35:158–167. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1220324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alexandersen S., Chamings A., Bhatta T.R. SARS‐CoV‐2 genomic and subgenomic RNAs in diagnostic samples are not an indicator of active replication. Nat Commun. 2020;11:6059. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19883-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Force A.D.T., Ranieri V.M., Rubenfeld G.D., et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y., Zhang D., Du G., et al. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID‐19: a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1569–1578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31022-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang K., Chen W., Zhang Z., et al. CD147‐spike protein is a novel route for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection to host cells. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:283. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00426-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Panicker S.R., Mehta‐D'souza P., Zhang N., Klopocki A.G., Shao B., McEver R.P. Circulating soluble P‐selectin must dimerize to promote inflammation and coagulation in mice. Blood. 2017;130:181–191. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-02-770479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berger G., Hartwell D.W., Wagner D.D. P‐selectin and platelet clearance. Blood. 1998;92:4446–4452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clark S.R., Ma A.C., Tavener S.A., et al. Platelet TLR4 activates neutrophil extracellular traps to ensnare bacteria in septic blood. Nat Med. 2007;13:463–469. doi: 10.1038/nm1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goshua G., Pine A.B., Meizlish M.L., et al. Endotheliopathy in COVID‐19‐associated coagulopathy: evidence from a single‐centre, cross‐sectional study. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(8):e575–e582. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30216-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bongiovanni M., Savino R., Bini F. Clinical features and outcome of COVID‐19 pneumonia in haemodialysis patients. Infect Dis. 2021;53:76–77. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2020.1820569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang D., Guo R., Lei L., et al. COVID‐19 infection induces readily detectable morphological and inflammation‐related phenotypic changes in peripheral blood monocytes, the severity of which correlate with patient outcome. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.24.20042655. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ragotte R.J., Pulido D., Donnellan F.R., et al. Human basigin (CD147) does not directly interact with SARS‐CoV‐2 spike glycoprotein. mSphere. 2021;6 doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00647-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shilts J., Crozier T.W.M., Greenwood E.J.D., Lehner P.J., Wright G.J. No evidence for basigin/CD147 as a direct SARS‐CoV‐2 spike binding receptor. Sci Rep. 2021;11:413. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-80464-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Evans J.P., Liu S.L. Role of host factors in SARS‐CoV‐2 entry. J Biol Chem. 2021;297:100847. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bury L., Camilloni B., Castronari R., et al. Search for SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA in platelets from COVID‐19 patients. Platelets. 2021;32:284–287. doi: 10.1080/09537104.2020.1859104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muramatsu T. Basigin (CD147), a multifunctional transmembrane glycoprotein with various binding partners. J Biochem. 2016;159:481–490. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvv127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pennings G.J., Yong A.S., Kritharides L. Expression of EMMPRIN (CD147) on circulating platelets in vivo. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:472–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seizer P., Ungern‐Sternberg S.N., Schonberger T., et al. Extracellular cyclophilin A activates platelets via EMMPRIN (CD147) and PI3K/Akt signaling, which promotes platelet adhesion and thrombus formation in vitro and in vivo. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:655–663. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.305112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stark K., Philippi V., Stockhausen S., et al. Disulfide HMGB1 derived from platelets coordinates venous thrombosis in mice. Blood. 2016;128:2435–2449. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-04-710632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Middleton E.A., He X.Y., Denorme F., et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) contribute to immunothrombosis in COVID‐19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. Blood. 2020;36(10):1169–1179. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020007008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leppkes M., Knopf J., Naschberger E., et al. Vascular occlusion by neutrophil extracellular traps in COVID‐19. EBioMedicine. 2020;58:102925. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nicolai L., Leunig A., Brambs S., et al. Immunothrombotic dysregulation in COVID‐19 pneumonia is associated with respiratory failure and coagulopathy. Circulation. 2020;142:1176–1189. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.048488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ackermann M., Anders H.J., Bilyy R., et al. Patients with COVID‐19: in the dark‐NETs of neutrophils. Cell Death Differ. 2021;28(11):3125–3139. doi: 10.1038/s41418-021-00805-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wolfel R., Corman V.M., Guggemos W., et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID‐2019. Nature. 2020;581:465–469. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bermejo‐Martin J.F., Gonzalez‐Rivera M., Almansa R., et al. Viral RNA load in plasma is associated with critical illness and a dysregulated host response in COVID‐19. Crit Care. 2020;24:691. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03398-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hogan C.A., Stevens B.A., Sahoo M.K., et al. High frequency of SARS‐CoV‐2 RNAemia and association with severe disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72:e291–e295. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jacobs J.L., Bain W., Naqvi A., et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 Viremia is associated with COVID‐19 severity and predicts clinical outcomes. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rondina M.T., Brewster B., Grissom C.K., et al. In vivo platelet activation in critically ill patients with primary 2009 influenza A(H1N1) Chest. 2012;141:1490–1495. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koupenova M., Corkrey H.A., Vitseva O., et al. The role of platelets in mediating a response to human influenza infection. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1780. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09607-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zuo Y., Yalavarthi S., Shi H., et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) as markers of disease severity in COVID‐19. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.09.20059626. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1‐S2