Abstract

Oxygen plays an important role in diverse biological processes. However, since quantitation of the partial pressure of cellular oxygen in vivo is challenging, the extent of oxygen perturbation in situ and its cellular response remains underexplored. Using two‐photon phosphorescence lifetime imaging microscopy, we determine the physiological range of oxygen tension in osteoclasts of live mice. We find that oxygen tension ranges from 17.4 to 36.4 mmHg, under hypoxic and normoxic conditions, respectively. Physiological normoxia thus corresponds to 5% and hypoxia to 2% oxygen in osteoclasts. Hypoxia in this range severely limits osteoclastogenesis, independent of energy metabolism and hypoxia‐inducible factor activity. We observe that hypoxia decreases ten‐eleven translocation (TET) activity. Tet2/3 cooperatively induces Prdm1 expression via oxygen‐dependent DNA demethylation, which in turn activates NFATc1 required for osteoclastogenesis. Taken together, our results reveal that TET enzymes, acting as functional oxygen sensors, regulate osteoclastogenesis within the physiological range of oxygen tension, thus opening new avenues for research on in vivo response to oxygen perturbation.

Keywords: bone metabolism, epigenetic regulation, intravital imaging, osteoclast, oxygen

Subject Categories: Chromatin, Transcription & Genomics; Musculoskeletal System

Within the physiological range of oxygen tension, ten‐eleven translocation (TET) enzymes act as functional oxygen sensors involved in osteoclastogenesis.

Introduction

Oxygen plays an essential role in serving as the final electron acceptor for aerobic respiration and is also a substrate in reactions that generate metabolites and structural macromolecules. Since a reduction in oxygen availability (hypoxia) has physiological and pathophysiological implications (Semenza, 2002; Palazon et al, 2014), aerobic organisms such as animals and land plants adopt alternative solutions to direct their primary hypoxia responses (Hammarlund et al, 2020). A major breakthrough in understanding such hypoxia responses in animals came through the discovery of the prolyl hydroxylase (PHD)/hypoxia‐inducible factor (HIF) axis (Wang & Semenza, 1993; Maxwell et al, 1999; Ohh et al, 2000; Jaakkola et al, 2001). PHD enzymes are members of the 2‐oxoglutarate (2‐OG)‐dependent dioxygenase enzyme family and act as oxygen sensors to catalyze the oxidation of specific prolyl residues in HIF‐α proteins that enable their recognition by ubiquitin ligase complexes and their subsequent degradation by the proteasome. A decrease in oxygen availability results in the attenuation of PHD‐mediated hydroxylation to enable HIF‐α stabilization. The stabilized HIF‐α can then heterodimerize with aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT) to trigger a genetic program that controls angiogenesis, cell growth, and a switch to a glycolytic cell metabolism, thereby enabling cellular adaptation to hypoxia (Semenza, 2002; Wilson et al, 2020).

Moreover, recent research on the hypoxia response machinery revealed the importance of other 2‐OG‐dependent dioxygenases whose activities also depend on oxygen availability. The DNA demethylases—ten‐eleven translocation (TET) methylcytosine dioxygenases—catalyze the oxidation of 5‐methylcytosine, but their activity is inhibited in severe hypoxic conditions of the tumor microenvironment, resulting in DNA hypermethylation (Laukka et al, 2016; Thienpont et al, 2016). The Jumonji‐C (JmJC) domain‐containing histone lysine demethylases (KDMs) also belong to the dioxygenase family of enzymes, which catalyze the oxidation of methyl groups on histones. Consequently, the hypoxia‐induced decrease in the activity of KDMs leads to an altered histone methylation status, with implications for tumorigenesis (Batie et al, 2019; Chakraborty et al, 2019). These observations have raised intriguing questions as to which enzyme(s) play a pivotal role in oxygen sensing.

On the basis of the Michaelis–Menten constant (KM) for oxygen, since each of the dioxygenases has a different affinity for oxygen [e.g., KDM5A and KDM6A have a KM of 117 and 260 mmHg, respectively (Batie et al, 2019; Chakraborty et al, 2019), TET2 has a KM of 39 mmHg (Laukka et al, 2016), and PHD1 has a KM ranging from 87 to 299 mmHg (Wilson et al, 2020)], the degree of changes in the reactions catalyzed by the dioxygenases largely depends on the factors that define hypoxia, which are in turn dependent on the tissue and intracellular concentration of oxygen in a given cell type. However, the extent of oxygen tension that a specific cell experiences in vivo still remains ambiguous.

Bone homeostasis depends on the intimate coupling of bone resorption by osteoclasts and bone formation by osteoblasts (Takayanagi, 2007; Lorenzo et al, 2008). Bone remodeling imbalance arising because of increased osteoclast activity and/or decreased osteoblast activity leads to bone‐wasting states in diseases such as osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and periodontitis (Boyle et al, 2003; Teitelbaum & Ross, 2003; Zaidi, 2007). Glycolysis is the major metabolic pathway that regulates osteoblast differentiation, which is coordinated by the HIF‐α proteins (Guntur et al, 2014; Regan et al, 2014; Dirckx et al, 2018). Indeed, hypoxia affects osteogenesis at a variety of levels ranging from direct action to indirect regulation via the stimulation of angiogenesis (Wang et al, 2007; Ramasamy et al, 2014; Xie et al, 2014). Thus, hypoxia is thought to provide a favorable environment for osteoblastogenesis (Lee et al, 2017). In contrast, oxidative metabolism is an oxygen‐dependent energy‐producing process that is essential for osteoclast differentiation (Ishii et al, 2009; Nishikawa et al, 2015). Of note, since bone resorption driven by the massive secretion of acids and specialized proteinases is an energy‐consuming process, osteoclasts require substantial oxygen to support their energy demands with respect to both differentiation and function. Thus, oxygen is likely to be an important environmental factor for osteoclast regulation; however, the in vivo oxygen tension in osteoclasts and the effect of its perturbation on osteoclastogenesis remain unclear.

Several methods to assess oxygen perturbation in different tissues are available. Immunohistochemistry for pimonidazole adducts and HIF‐α accumulation is widely used for analyzing hypoxia within tissue (Varia et al, 1998; Ramasamy et al, 2014), but it is neither quantitative nor indicative of oxygen tension. Electrochemical electrodes are used to measure oxygen tension in real time; e.g., the tip of micro‐electrode is positioned directly in the target tissue, and the electrode in the gas analyzer measures oxygen using the collected blood. However, these invasive procedures are not suitable for the measurement of oxygen tension in hard tissue. On the other hand, non‐invasive methods to quantitatively assess oxygen tension in vivo have been developed based on phosphorescence quenching (Vanderkooi et al, 1987; Rumsey et al, 1988) and magnetic resonance techniques including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) (Roussakis et al, 2015). These methods have both advantages and limitations in terms of applicable targets, spatial resolution, tissue permeability, convenience, and reversibility. Of these methods, optical imaging utilizing a phosphorescence probe has great advantages in determining the spatio‐temporal dynamics of oxygen in both soft and hard tissues (Spencer et al, 2014; Hirakawa et al, 2015; Yoshihara et al, 2015). Here, using two‐photon phosphorescence lifetime imaging microscopy with a cell‐penetrating phosphorescent probe that we originally developed, we first succeeded in determining the physiological range of oxygen tension in the bone marrow at the single‐cell resolution. Furthermore, we show that TET enzymes play a pivotal role in oxygen sensing and are involved in osteoclastogenesis via an epigenetic regulation mechanism within the physiological range of oxygen tension.

Results

Definition of physiological normoxia and hypoxia for osteoclasts in the local bone marrow environment of live mice

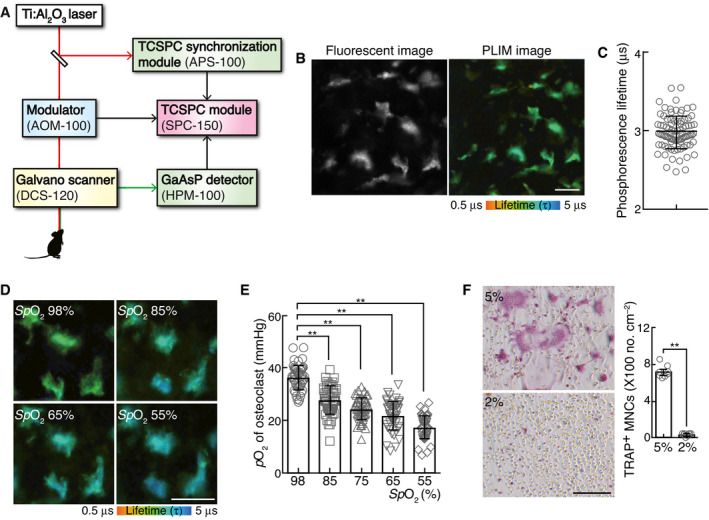

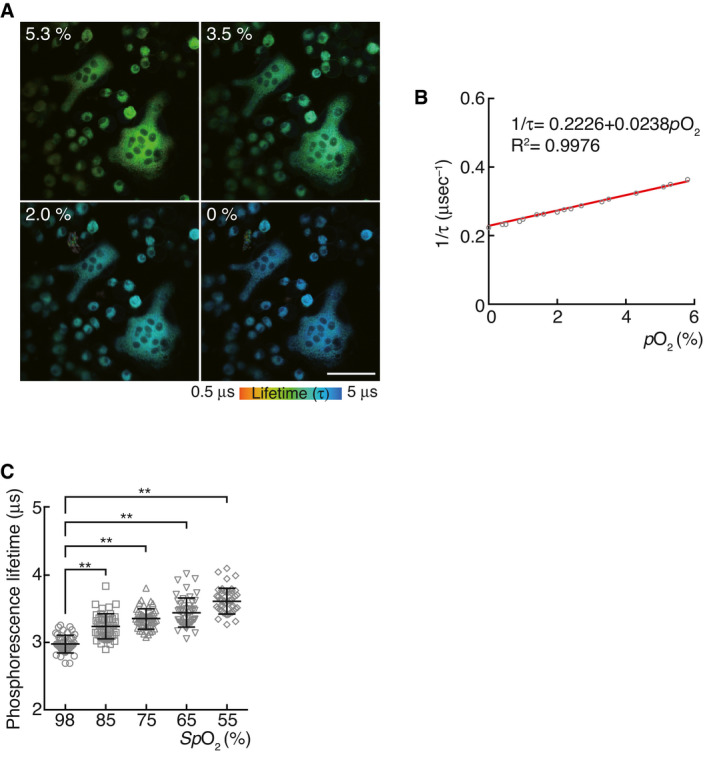

Phosphorescence quenching by oxygen is a standard method for the sequential monitoring and non‐invasive measurement of oxygen concentration (Vanderkooi et al, 1987; Rumsey et al, 1988). We recently developed a method to assess intracellular oxygen tension using a cell‐penetrating phosphorescent probe (BTPDM1) based on the Ir (III) complex and a bifurcated fiber system (Hirakawa et al, 2015). The current study used a two‐photon laser scanning microscope (TPLSM) equipped with time‐correlated single‐photon counting (TCSPC) system, to assess combined intensity‐lifetime imaging of phosphorescence in live mice. This technique was named two‐photon phosphorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (2PLIM). Prior to imaging, BTPDM1 was injected into TcirgGFP/+ mice, their osteoclast lineage cells of which express green fluorescence protein (GFP) (Sun‐Wada et al, 2009). GFP fluorescence enabled osteoclasts to be visualized while the phosphorescence lifetime was simultaneously measured using the TCSPC system (Fig 1A and B). The phosphorescence lifetime of mice osteoclasts during air inhalation was 2.98 ± 0.02 μs (Fig 1C). In order to calculate oxygen tension of osteoclasts via phosphorescence lifetime, we prepared a calibration curve showing the relationship between phosphorescence lifetime and oxygen concentration (Fig EV1A and B). We cultured primary osteoclasts treated with BTPDM1 and measured phosphorescence lifetime under various oxygen concentrations. The results indicated that the in vivo oxygen tension of osteoclasts was 36.4 ± 0.7 mmHg (4.8 ± 0.1%; Figs 1D and EV1C). Next, in order to determine the physiological range of oxygen tension in osteoclasts, we measured the oxygen tension of osteoclasts in mice during hypoxic air inhalation (approximately 14% oxygen to reduce arterial oxygen saturation [spO2] to 55%). As a result, phosphorescence lifetime of osteoclasts in these mice was prolonged to 3.62 ± 0.03 μs, which in turn was estimated as 17.4 ± 0.6 mmHg (2.3 ± 0.1%) of oxygen tension (Figs 1E and EV1C). These results enabled us to introduce a physiological context to oxygen tension of osteoclasts in vivo, i.e., ca. 5% as physiological normoxia (referred to as physioxia) in the mice whose spO2 is 98% during air inhalation and ca. 2% as physiological hypoxia in the mice whose spO2 reduced to 55% during inhalation of hypoxic air containing 14% oxygen.

Figure 1. Measurement of passive physiological range of oxygen tension (pO2) of osteoclasts.

-

ASchematic diagram of the two‐photon intravital imaging and 2PLIM.

-

BRepresentative intravital image of calvarial bone marrow of Tcirg1EGFP/+ male mice treated with BTPDM1 showing osteoclasts (left, EGFP fluorescence) and 2PLIM image for pO2 changes (right, phosphorescence lifetime of BTPDM1). Scale bar, 20 μm.

-

CPhosphorescence lifetime in each osteoclast of calvarial bone marrow of mice upon exposure to ambient air (n = 91 from six mice). Data denote mean ± s.e.m.

-

D, EChange in pO2 of osteoclasts in the mice upon exposure to various concentrations of oxygen from 21% to 14% pO2. Magnified PLIM images of osteoclasts under different peripheral oxygen saturations (SpO2, D). The pO2 of each osteoclast in these mice was plotted (E, n = 47 from three mice for each SpO2). Scale bar, 20 μm. Data denote mean ± s.e.m. **P < 0.01 (ANOVA).

-

FEffect of physioxia (5% pO2) or physiological hypoxia (2% pO2) on osteoclastogenesis. TRAP‐stained cells (left panel) and the number of TRAP‐positive cells with more than three nuclei (right). Scale bar, 100 μm. Data denote mean ± s.e.m. **P < 0.01 (n = 8 biological replicates; t‐test).

Figure EV1. Reciprocal plot of phosphorescence lifetime and oxygen concentration.

-

APLIM images of in vitro‐cultured osteoclasts under different conditions of oxygen concentration. Scale, 50 μm.

-

BThe phosphorescence quenching due to dissolved oxygen in solution can be examined by the Stern–Volmer equation. The approximate line was constructed by a straight‐line approximation, and an approximation formula and the coefficient of determination are shown.

-

CPhosphorescence lifetime in each osteoclast of the calvarial bone marrow of mice upon inhalation of normal (21% pO2) and hypoxic (14% pO2) air. The phosphorescence lifetime of each osteoclast was plotted (right, n = 47 from three mice for each SpO2). Data denote mean ± s.e.m. **P < 0.01 (ANOVA).

Studies that have been conducted so far on the effect of hypoxia on osteoclast differentiation indicate that oxygen is a negative regulator of osteoclast differentiation (Arnett et al, 2003; Fukuoka et al, 2005; Murata et al, 2017). Osteoclast differentiation was evaluated in vitro by counting multinucleated cells (MNCs) positive for the osteoclast marker, tartrate‐resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP), following stimulation of bone marrow‐derived monocyte/macrophage precursor cells (BMMs) with receptor activator of nuclear factor‐κB ligand (RANKL), and in the presence of macrophage colony‐stimulating factor (M‐CSF)(Nishikawa et al, 2010; Hayashi et al, 2012). We confirmed that the formation of TRAP‐positive MNCs was significantly enhanced when they were cultured in hypoxic conditions of 10% oxygen, compared with that under atmospheric air conditions (Appendix Fig S1A). However, our 2PLIM revealed that these culture conditions do not reflect in vivo oxygen levels. In order to mimic in vivo oxygen tension, we investigated the effect of hypoxia on osteoclast differentiation by performing an in vitro experiment either in 5% oxygen (physioxia) or 2% oxygen (hypoxia). The experiment produced results contrary to those of previous results. The formation of TRAP‐positive MNCs was severely impaired under 2% oxygen compared with that under 5% oxygen (Fig 1F and Appendix Fig S1B). Nevertheless, neither the number of proliferative BMMs nor the apoptotic activities of BMMs were affected in both 5% and 2% oxygen (Appendix Fig S1C and D). These results suggest that oxygen is a positive regulator of osteoclast differentiation.

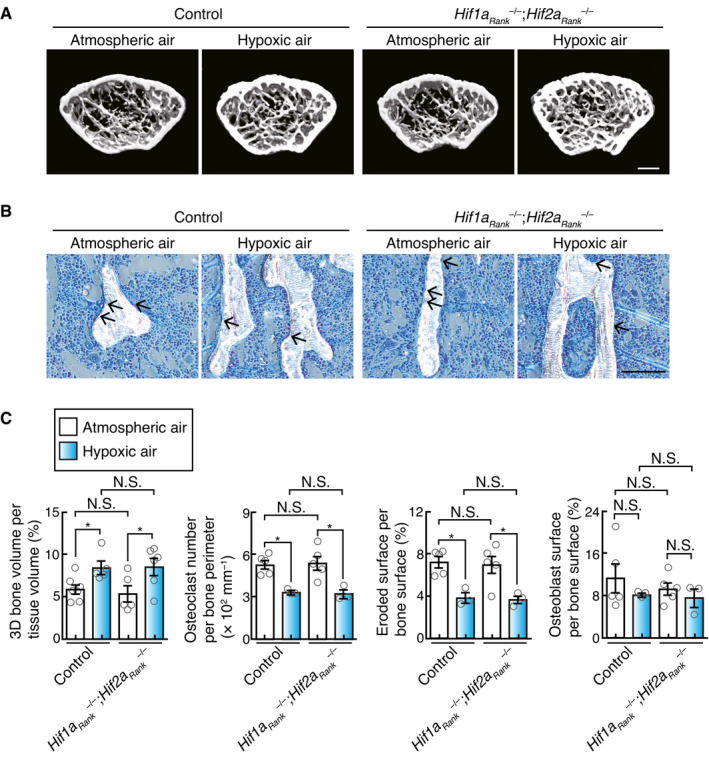

The effect of hypoxia on bone metabolism was studied in vivo by studying an experimental mouse hypoxia models generated under acute (oxygen inhalation at a low concentration) conditions. Mice exposed to hypoxia displayed high bone mass phenotypes with low numbers of osteoclasts, while no obvious difference in the number of osteoblasts was observed (Fig 2A–C). Although the hypoxia signaling pathway is involved in the promotion of osteoblastogenesis (Wang et al, 2007), our experimental conditions, wherein the mice were exposed to 14% oxygen for 10 days, did not affect osteoblastogenesis. Taken together, these results suggest that hypoxia causes high bone mass due to defective osteoclast differentiation.

Figure 2. Effect of oxygen deprivation on bone metabolism.

-

AμCT analysis of the femurs of 10‐week‐old male mice upon exposure to low oxygen concentration (14% pO2, n = 5) or ambient air (n = 7), and of 10‐week‐old Hif1aRank –/–; Hif2aRank –/– male mice upon exposure to low oxygen concentration (14% pO2, n = 6) or ambient air (n = 5) for 10 days (axial view of the metaphyseal region). Scale, 0.5 mm.

-

BHistological analysis of the proximal tibias of 10‐week‐old male mice upon exposure to low oxygen concentration (14% pO2) or ambient air for 10 days, and of 10‐week‐old Hif1aRank –/–; Hif2aRank –/– male mice upon exposure to low oxygen concentration (14% pO2) or ambient air (toluidine blue staining [arrow, osteoclasts]). Scale, 100 μm.

-

CParameters for osteoclasts and osteoblasts during bone morphometric analysis of 10‐week‐old male mice under low oxygen concentration (n = 3) or ambient air (n = 5), and 10‐week‐old Hif1aRank –/–; Hif2aRank –/– male under low oxygen concentration (n = 3) or ambient air (n = 5) for 10 days. Data denote mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05; NS, not significant (t‐test).

HIF‐α is dispensable for the osteoclast response to physioxia perturbation

The above‐stated findings raised the necessity for elucidating the mechanism(s) underlying oxygen‐induced regulation of osteoclast differentiation. Hypoxia‐inducible transcription factors, HIF‐1α and HIF‐2α, are the key mediators of cellular adaptation to oxygen deprivation (Wang et al, 1995). PHDs, members of the 2‐oxoglutarate‐dependent dioxygenase family, play a well‐established role as oxygen sensors during the hydroxylation of specific proline residues on HIFs. This leads to their destabilization via ubiquitination induced by von‐Hippel Lindau (VHL) ubiquitin ligase and subsequent proteasomal degradation under oxygen‐rich conditions (Majmundar et al, 2010). Both osteoclast precursors and mature osteoclasts expressed HIF‐related molecules (Appendix Fig S2A). In addition, protein expression of HIF‐1α and HIF‐2α under 2% oxygen was compared with that under 5% oxygen (Fig 3A). Therefore, we hypothesized that HIFs may be involved in the impairment of osteoclast differentiation under physiological hypoxia. We crossed Hif1aflox/flox and Hif2aflox/flox mice (Ryan et al, 1998, 2000; Semba et al, 2016) with RankCre/+ (Maeda et al, 2012) mice to specifically disrupt Hif1a and Hif2a in the osteoclast lineage (Hif1aRank –/– ; Hif2aRank –/– ). However, no obvious difference in RANKL‐induced formation of TRAP‐positive MNCs and the expression of osteoclast‐related genes was observed between the wild‐type and Hif1aRank –/– ; Hif2aRank –/– cells under both 2% and 5% oxygen, although the expression of HIF‐target genes was severely decreased in Hif1aRank –/– ; Hif2aRank –/– cells (Fig 3A–C). Furthermore, Hif1aRank –/– ; Hif2aRank –/– mice exposed to hypoxia displayed high bone mass phenotypes with a decreased number of osteoclasts, similar to that of the wild‐type mice (Fig 2). These results suggested that HIFs were not involved in hypoxia‐induced inhibition of osteoclast differentiation.

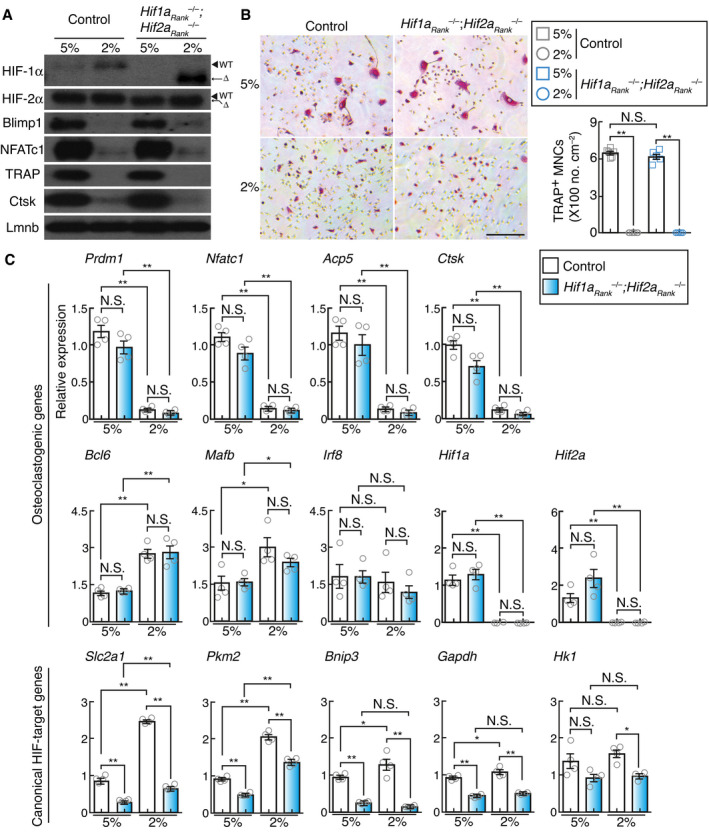

Figure 3. Effect of physiological hypoxia on hypoxia‐inducible factor activity.

-

AProtein expression of HIF‐1α, HIF‐2α, Blimp1, NFATc1, Ctsk, and TRAP in control and Hif1aRank –/–; Hif2aRank –/– BMMs stimulated with RANKL and cultured under different conditions of oxygen concentration for 2 days.

-

BEffect of physioxia (5% pO2) or physiological hypoxia (2% pO2) on the formation of osteoclast from control and Hif1aRank –/–; Hif2aRank –/– BMMs. TRAP‐stained cells (left panel) and the number of TRAP‐positive cells with more than three nuclei (right). Scale bar, 100 μm. Data denote mean ± s.e.m. **P < 0.01; NS, not significant (n = 6 (control) and n = 6 (Hif1aRank –/–; Hif2aRank –/– ) biological replicates; ANOVA).

-

CExpression of osteoclastogenic and canonical HIF‐target genes in wild‐type control and Hif1aRank –/–; Hif2aRank –/– BMMs under conditions of 5% or 2% oxygen. Data denote mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; NS, not significant (n = 4 biological replicates; ANOVA).

Energy metabolism in osteoclasts is not affected by physioxia perturbation

It has also been proposed that mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation acts as an oxygen sensor to produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP) by transferring electrons to oxygen (Solaini et al, 2010). Indeed, intracellular ATP levels in osteoclasts are heavily dependent on mitochondrial activity (Nishikawa et al, 2015). We therefore hypothesized that hypoxia may perturb energy metabolism, leading to the inhibition of osteoclast differentiation. In order to examine the effect of hypoxia on ATP generation in osteoclasts in vivo, we used a genetically encoded ATP biosensor, GO‐ATeam2 (Nakano et al, 2011; Yamamoto et al, 2019), to visualize ATP levels in osteoclasts. As GO‐ATeam2 is composed of a bacteria‐derived ATP binding domain sandwiched between EGFP and orange fluorescent protein (OFP), as the Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) pair, specific binding of ATP to the GO‐ATeam2 domain induces a conformational change that leads to FRET between the two fluorophores. As a quantitative FRET readout, we measured the fluorescence lifetime of EGFP from GO‐ATeam2 in live mice using a TPLSM with TCSPC imaging technique (two‐photon fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy, 2FLIM) and calculated the FRET efficiency of GO‐ATeam2 based on the fluorescence lifetime measurement. We generated mice expressing GO‐ATeam2 and tdTomato proteins in osteoclast lineage cells by crossing ROSA26 GO‐ATeam2/+ (Yamamoto et al, 2019) mice with Tg(Acp5‐tdTomato) mice (Kikuta et al, 2013). The fluorescence of the tdTomato protein enabled the visualization of osteoclasts, while fluorescence lifetime was simultaneously measured using the TCSPC system. The FRET efficiency of GO‐ATeam2 in mouse osteoclasts during air inhalation was 0.40 ± 0.02 (Fig 4A). Next, to determine the effect of hypoxia on osteoclast ATP levels, we performed fluorescence lifetime measurements in mice during hypoxic air inhalation. The FRET efficiency of GO‐ATeam2 in mouse osteoclasts was almost comparable to that of mice during air inhalation, suggesting that ATP metabolism in osteoclasts remains unaffected within the physiological range of oxygen in vivo.

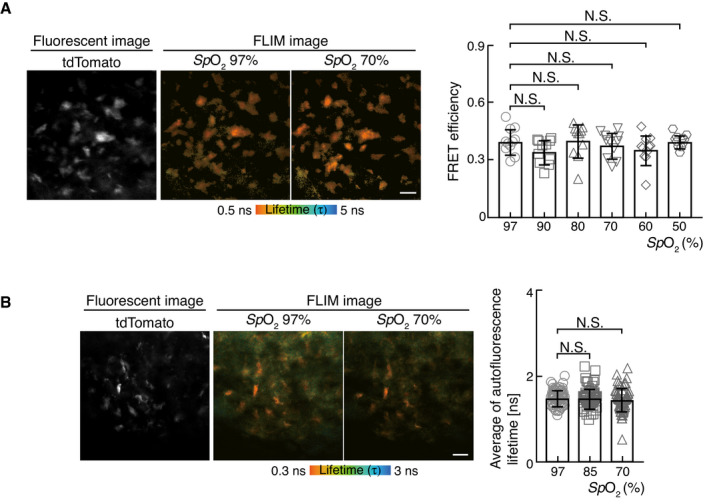

Figure 4. Effect of oxygen deprivation on energy metabolism in vivo .

-

ARepresentative intravital image of calvarial bone marrow of Rosa26GO‐ATeam/+ ; Tg(Acp5‐tdTomato) male mice showing osteoclasts (left, tdTomato fluorescence) and FLIM image for ATP changes (middle and right, fluorescence lifetime of EGFP). The FRET efficiencies of each osteoclast were plotted from the mice upon exposure to low oxygen atmosphere (14% pO2) or ambient air (right, n = 11 from three mice for each SpO2). Scale bar, 20 μm. Data denote mean ± s.e.m. not significant (ANOVA).

-

BRepresentative intravital image of calvarial bone marrow of Tg(Acp5‐tdTomato) male mice showing osteoclasts (left, tdTomato fluorescence) and NAD(P)H autofluorescence lifetime images (middle and right). Average of autofluorescence lifetime of each osteoclast was plotted from the mice upon exposure to low oxygen concentration (14% pO2) or ambient air (right, n = 64 from three mice for each SpO2). Scale bar, 20 μm. Data denote mean ± s.e.m. NS, not significant (ANOVA).

Nicotinamide adenosine dinucleotide (NAD+) is a key determinant of cellular energy metabolism, while NADP+, its phosphorylated form, plays a central role in biosynthetic pathways and redox regulation. Both are reduced to form NAD(P)H and have identical spectral properties and emit autofluorescence upon excitation. NAD(P)H has both short and long autofluorescence lifetimes, depending on whether it is in a free or protein‐bound state. In general, free and protein‐bound states of NAD(P)H reflect glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation, respectively. Therefore, the decrease in autofluorescence lifetime of NAD(P)H is attributed to a shift from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis (Kalinina et al, 2016). In order to further investigate the role of hypoxia on energy metabolism in osteoclasts in vivo, we employed autofluorescence lifetime imaging of NAD(P)H in Tg(Acp5‐tdTomato) mice. The fluorescence of tdTomato protein enabled osteoclasts to be visualized while autofluorescence lifetime was being simultaneously measured using the TCSPC system. The average autofluorescence lifetime of osteoclasts in mice during air inhalation was 1.49 ± 0.02 ns (Fig 4B). Next, to determine the effect of hypoxia on osteoclast energy metabolism, we measured autofluorescence lifetime during hypoxic air inhalation by mice. The average autofluorescence lifetime in hypoxic mouse osteoclasts was almost comparable to that of mice during air inhalation. These results indicated that cellular energy metabolism in osteoclasts was not affected within the physiological range of oxygen tension in vivo.

TETs play a pivotal role in oxygen sensing and are involved in osteoclastogenesis

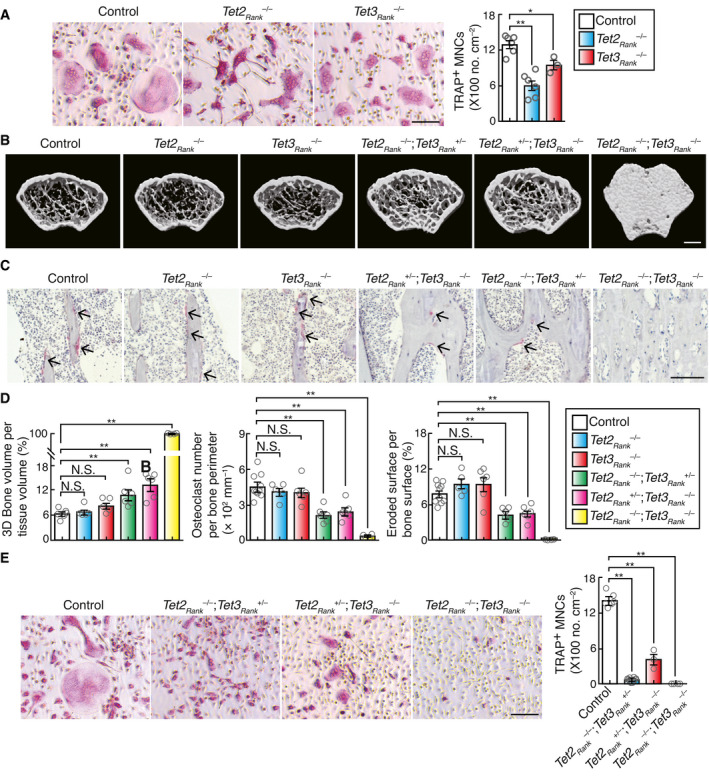

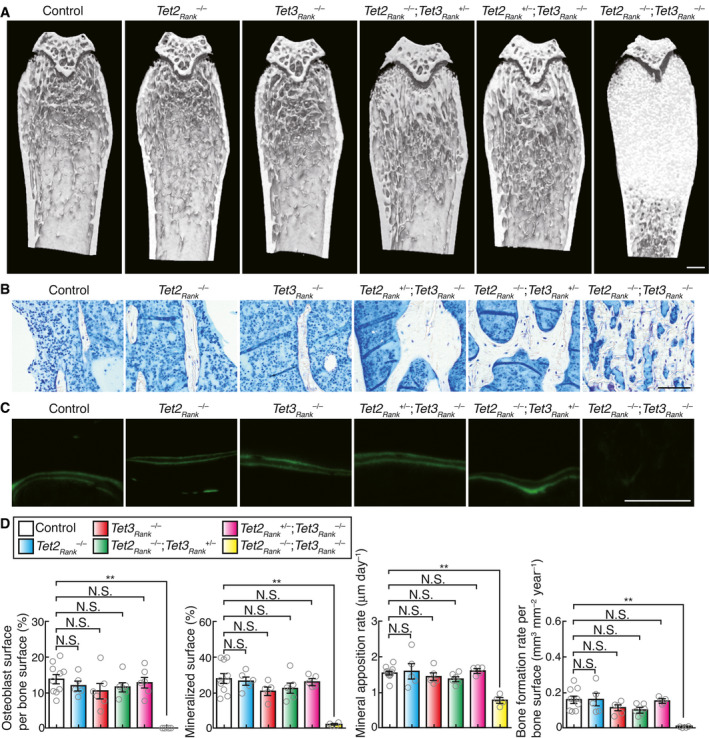

To determine whether physiological hypoxia could affect cellular metabolic activities in osteoclasts, we assayed metabolites in osteoclast precursors using ion‐chromatography (IC)‐MS. The levels of TCA cycle metabolites, but not of glycolytic metabolites, were significantly changed in BMMs under 2% oxygen compared with those under 5% oxygen (Fig EV2A and B). In particular, 2‐OG level in BMMs under 2% oxygen was significantly increased, predicting that physiological hypoxia may impair the activity of 2‐OG‐consuming enzyme. 2‐OG‐dependent dioxygenases catalyze hydroxylation reaction, which is inherently dependent on ambient oxygen tension, providing a molecular basis for the oxygen‐sensing function of these enzymes. Physiological oxygen concentration in osteoclasts was found to be far below the Km values of PHDs for oxygen (Hirsila et al, 2003). Of the dioxygenases, TET and KDM proteins were highly expressed in both osteoclast precursors as well as mature osteoclasts (Figs EV3A–E, and EV4A and B, and Appendix Fig S2B) and showed a high affinity for oxygen (Appendix Fig S3), allowing optimal hydroxylation reaction under the physiological oxygen levels in osteoclasts. Furthermore, the activity of an enzyme whose Km value for oxygen was ca. 40 μM was predicted to be dramatically decreased in mice during hypoxic air inhalation under physiological hypoxia (Appendix Fig S4). It was recently shown that some KDMs (KDM5A and 6A) directly modulate the methylation status of chromatin dependent on oxygen availability (Batie et al, 2019; Chakraborty et al, 2019). However, no obvious difference in methylation status of histone H3 was observed between 2% and 5% oxygen (Appendix Fig S5A). In contrast, since hypoxia induced DNA hypermethylation (Appendix Fig S5B), we hypothesized that TET proteins may serve as oxygen sensors in osteoclasts. In mammals, the TET protein family consists of three members, i.e., Tet1, Tet2, and Tet3. Although Tet2 has been found to be involved in the regulation of osteoclast differentiation, the role of Tet3 remains unclear (Chu et al, 2018). The role of Tet2 and Tet3 in osteoclasts was evaluated by generating osteoclast‐specific Tet2 and Tet3 knockout mice by crossing Tet2flox/flox and Tet3flox/flox mice (Tanaka et al, 2020) with RankCre/+ mice to specifically disrupt Tet2 and Tet3 in osteoclast lineage cells (Tet2Rank –/– and Tet3aRank –/– , respectively). RANKL‐induced formation of TRAP‐positive MNCs in both Tet2Rank –/– and Tet3aRank –/– BMMs was lower than that in wild‐type BMMs (Fig 5A). However, we observed no obvious bone phenotype in either Tet2Rank –/– or Tet3aRank –/– mice (Figs 5B–D and EV5A). Although it has been previously reported that Tet2 global knockout mice display high bone mass (Chu et al, 2018), this phenotype may have been caused by an abnormality in non‐osteoclast lineage cells. Next, to explore the possibility that Tet3 may compensate for the loss of Tet2 and vice versa, we created osteoclast‐specific Tet2 and Tet3 compound knockout mice (Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/–, Tet2Rank +/–; Tet3aRank –/– and Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank –/– , respectively). Bone volume of Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– and Tet2Rank +/–; Tet3aRank –/– mice was greatly enhanced (Fig 5B). Bone morphometric analysis revealed that osteoclast numbers as well as indicators of osteoclastic bone resorption in Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– and Tet2Rank +/–; Tet3aRank –/– mice were lower than those of wild‐type control mice, whereas the parameters for bone formation in these mice were normal (Figs 5C and D, and EV5B–D). In addition, Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank –/– mice exhibited an osteopetrotic phenotype characterized by an absence of osteoclasts, which was also observed in another type of osteoclast‐specific Tet2 and Tet3 knockout mice generated by crossing CX3CR1Cre/+ mice (Appendix Fig S6). Consistent with these findings, deficiency in both Tet2 and Tet3 led to a decrease in RANKL‐induced formation of TRAP‐positive MNCs as well as the expression of osteoclast‐related genes in a gene dose‐dependent manner even under physioxia (Figs 5E and EV4C, and Appendix Fig S7A). In contrast, neither proliferative nor apoptotic activities of Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– BMMs were affected (Fig EV3D and E), similar to those of BMMs under 5% and 2% oxygen (Fig 1F and Appendix Fig S1C and D). In addition, overexpression of either of the Tet members tended to restore the impaired formation of TRAP‐positive MNCs caused by a deficiency in both Tet2 and Tet3 (Appendix Fig S7B). These results collectively suggest that cooperation between Tet2 and Tet3 was important for osteoclast differentiation.

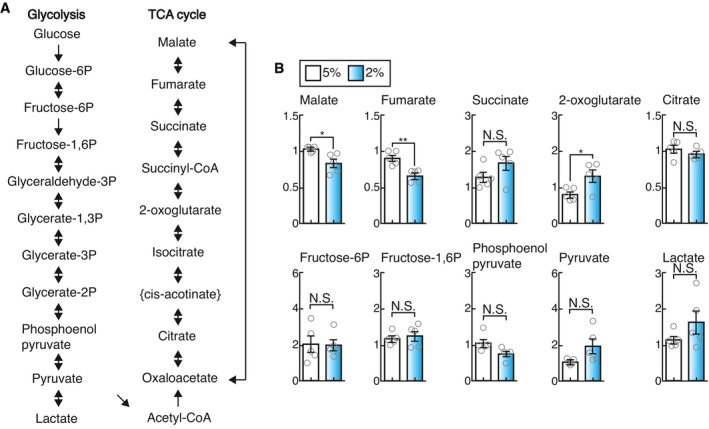

Figure EV2. Effect of physioxia and hypoxia on the levels of metabolites.

-

AMetabolites involved in glycolysis and the TCA cycle.

-

BLevels of metabolites involved in glycolysis and the TCA cycle. BMMs were cultured with 50 ng/ml RANKL in the presence of 10 ng/ml M‐CSF for 2 days under 5% and 2% oxygen. Data denote mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; NS, not significant (n = 5 biological replicates; t‐test).

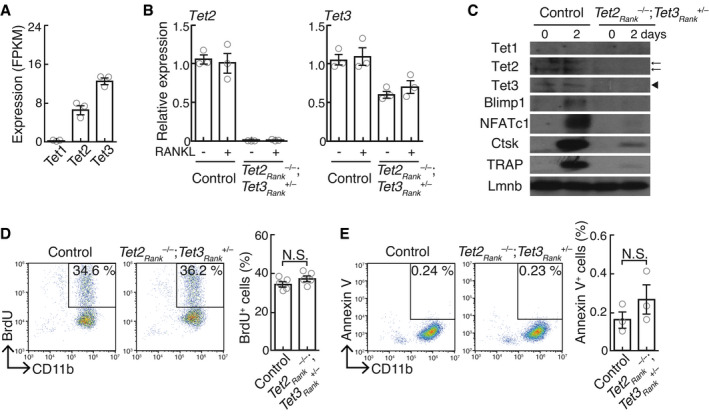

Figure EV3. Loss‐of‐function effect of Tet2 and Tet3 on cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation.

-

AmRNA expression of Tet1, Tet2, and Tet3 in BMMs stimulated with RANKL for 0 and 2 days (RNA‐seq analysis; n = 3 biological replicates). Data denote mean ± s.e.m.

-

BmRNA expression of Tet2 and Tet3 in control‐ and Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– ‐derived BMMs cultured in the absence and presence of RANKL for 2 days (quantitative RT–PCR analysis; n = 3 biological replicates). Data denote mean ± s.e.m.

-

CProtein expression in control‐ and Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– ‐derived BMMs cultured in the absence and presence of RANKL for 2 days. Arrows and arrowhead indicate Tet2 and Tet3 proteins, respectively.

-

D, EPercentage of BrdU‐labeled CD11b+ BMMs (D) and Annexin V+ CD11b+ BMMs (E) derived from control‐ and Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– mice. Data denote mean ± s.e.m. NS, not significant (n = 5 (D) and n = 3 (E) biological replicates; t‐test).

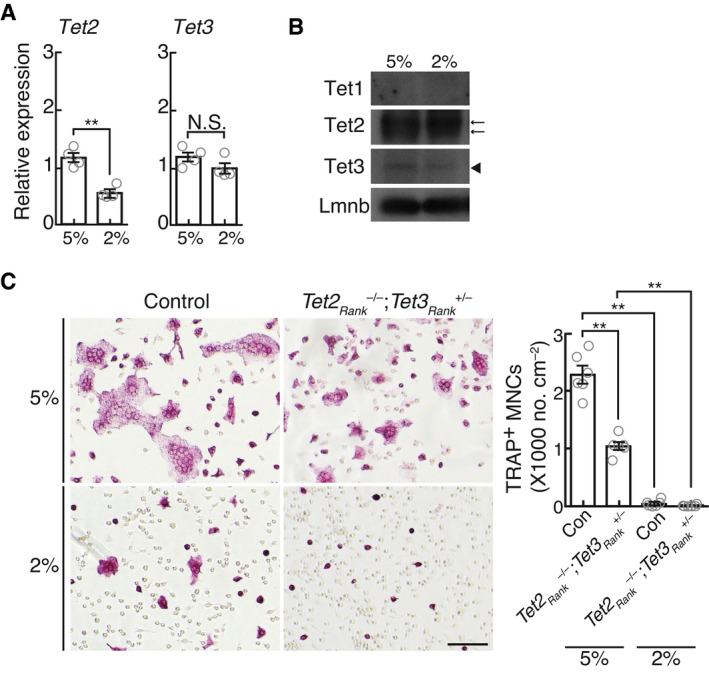

Figure EV4. Effect of hypoxia on the expression of Tet2 and Tet3, and osteoclast differentiation.

-

AmRNA expression of Tet2 and Tet3 in BMMs stimulated with RANKL for 2 days under 5% and 2% oxygen. Data denote mean ± s.e.m. **P < 0.01; NS, not significant (n = 4 biological replicates; t‐test).

-

BProtein expression of Tet1, Tet2, and Tet3 in BMMs stimulated with RANKL for 2 days under 5% and 2% oxygen. Arrows and arrowhead indicate Tet2 and Tet3 proteins, respectively.

-

CEffect of hypoxia on osteoclastogenesis. TRAP‐stained cells (left panel) and the number of TRAP‐positive cells with more than three nuclei (right). Scale bar, 100 μm. Data denote mean ± s.e.m. **P < 0.01 (n = 6 biological replicates; ANOVA).

Figure 5. Osteoclast‐specific Tet2‐ and Tet3‐deficient mice exhibit a high bone mass phenotype.

-

AEffect of Tet2 and Tet3 single deficiency on osteoclastogenesis. TRAP‐stained cells (left panel) and the number of TRAP‐positive cells with more than three nuclei (right). Scale bar, 100 μm. Data denote mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 (n = 6 (control and Tet2Rank –/– ) and n = 3 (Tet3aRank –/– ) biological replicates; ANOVA).

-

BμCT analysis of the femurs of 10‐week‐old control (n = 6), Tet2Rank –/– (n = 5), Tet3Rank –/– (n = 5), Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– (n = 6), Tet2Rank +/–; Tet3aRank –/– (n = 6), and Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank –/– (n = 4) male mice (axial view of the metaphyseal region). Scale, 0.5 mm.

-

CHistological analysis of the proximal tibias of 10‐week‐old control, Tet2Rank –/– , Tet3Rank –/– , Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– , Tet2Rank +/–; Tet3aRank –/– and Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank –/– male mice (TRAP staining [red, osteoclasts]). Scale, 100 μm.

-

DParameters for osteoclastic bone resorption during bone morphometric analysis of 10‐week‐old control (n = 10), Tet2Rank –/– (n = 5), Tet3Rank –/– (n = 6), Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– (n = 6), Tet2Rank +/–; Tet3aRank –/– (n = 6) and Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank –/– (n = 4) male mice. Data denote mean ± s.e.m. **P < 0.01; NS, not significant (ANOVA).

-

EEffect of Tet2 and Tet3 double deficiency on osteoclastogenesis. TRAP‐stained cells (left panel) and the number of TRAP‐positive cells with more than three nuclei (right). Scale bar, 100 μm. Data denote mean ± s.e.m. **P < 0.01 (n = 6 (control), n = 10 (Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– ), n = 3 (Tet2Rank +/–; Tet3aRank –/– ), and n = 4 (Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank –/– ) biological replicates; ANOVA).

Figure EV5. Bone phenotype of osteoclast‐specific Tet2‐ and Tet3‐deficient mice.

-

AμCT analysis of the femurs from 10‐week‐old control, Tet2Rank –/– , Tet3Rank –/– , Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– , Tet2Rank +/–; Tet3aRank –/– and Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank –/– male mice (longitudinal view of the metaphyseal region). Scale, 0.5 mm.

-

B, CHistological analysis of the proximal tibias of 10‐week‐old control, Tet2Rank –/– , Tet3Rank –/– , Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– , Tet2Rank +/–; Tet3aRank –/– and Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank –/– male mice (C, toluidine blue staining; D, calcein labeling). Scale, 100 μm.

-

DOsteoblastic parameters of osteoclast‐specific Tet2‐ and Tet3‐deficient mice. Bone morphometric analysis of 10‐week‐old control (n = 10), Tet2Rank –/– (n = 5), Tet3Rank –/– (n = 6), Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– (n = 6), Tet2Rank +/–; Tet3aRank –/– (n = 6), and Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank –/– (n = 4) male mice was performed. Data denote mean ± s.e.m. **P < 0.01; NS, not significant (ANOVA).

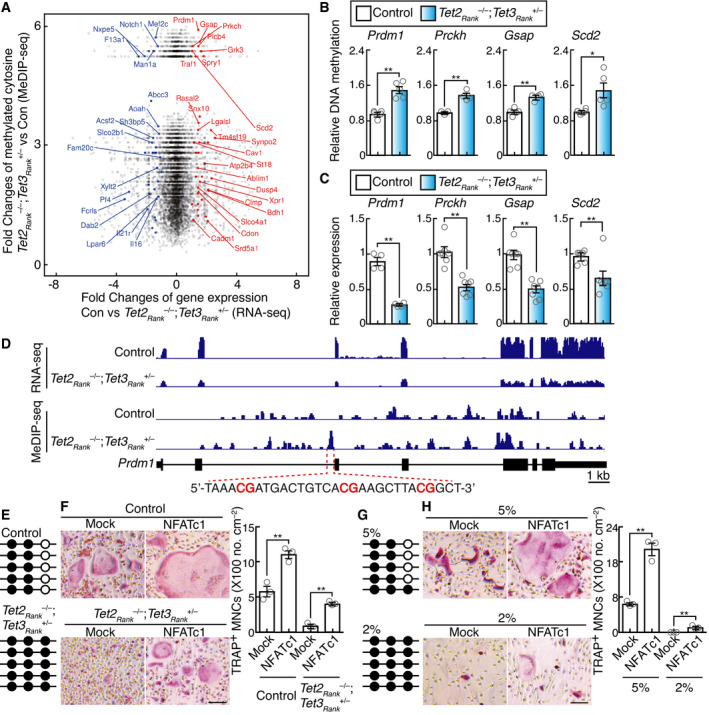

Next, to investigate the role of TET enzymes in osteoclastogenesis, we used a broad‐spectrum inhibitor of 2‐OG‐dependent oxygenase (Hopkinson et al, 2013), IOX1, and a TET‐specific inhibitor, octyl‐2‐hydroxyglutarate (2HG) (Figueroa et al, 2010). Treatment with IOX1 or 2HG impaired the formation of TRAP‐positive MNCs as well as the expression of osteoclast‐related genes (Appendix Fig S8A and B). Nevertheless, neither proliferative nor apoptotic activities of BMMs were affected by IOX1 or 2HG (Appendix Fig S8C and D). Therefore, it is likely that the effects of 2HG and IOX1 are likely to mimic the effects of hypoxia (Fig 1F and Appendix Fig S1C and D). These findings, in turn, led to queries regarding the mechanism(s) underlying the regulation of osteoclast differentiation by TET enzymes. Tet2 and Tet3 catalyze active DNA demethylation and function as transcription regulators (Ito et al, 2010; Tsagaratou & Rao, 2013), which led us to assess the target(s) of Tet2‐ and Tet3‐mediated regulation in osteoclastogenesis. To identify putative Tet2‐ and Tet3‐regulated genes, we performed genome‐wide screening of mRNA expression and methylated DNA regions in wild‐type and Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– BMMs, following RANKL treatment. We initially selected gene loci that showed fewer methylation sites in wild‐type cells than in Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– BMMs, following RANKL treatment, revealing that DNA methylation levels had been significantly changed in specific loci of 43 genes (Fig 6A; blue and red). We further selected the genes with significantly changed expression levels in Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– BMMs, compared with those of wild‐type cells. This revealed that the expression levels of 25 genes, including osteoclast‐related genes, were significantly decreased in Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– BMMs, where 6 genes were validated via quantitative RT–PCR and methylated DNA immunoprecipitation (MeDIP)‐qPCR analysis (Fig 6A, red; Fig 6B and C, and Appendix Fig S9A and B). As Blimp1 (encoded by Prdm1) indirectly activates the master regulator of osteoclastogenesis, NFATc1, by downregulating anti‐osteoclastogenic genes, such as Bcl6 and Mafb (Kim et al, 2007; Miyauchi et al, 2010; Nishikawa et al, 2010), we hypothesized that a deficiency of Tet2 and Tet3 may disrupt the Blimp1‐NFATc1 regulatory axis. Bisulfate sequencing showed that a region in the second intron of Prdm1 was hypermethylated in Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– BMMs compared to that in the corresponding wild‐type cells (Fig 6D and E). Furthermore, the expression of both Prdm1 and Nfatc1 in Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– BMMs was lower than that in the corresponding wild‐type cells, while Bcl6 and Mafb were highly expressed in Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– BMMs (Figs 6B and EV3C, and Appendix Fig S7A). In order to examine whether impaired osteoclastogenesis in Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– BMMs was caused by a loss of NFATc1 expression, we used a retroviral vector expressing NFATc1. Impaired osteoclast formation in Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– BMMs following RANKL treatment was significantly restored by NFATc1 overexpression (Fig 6F and Appendix Fig S9C). Furthermore, impaired osteoclast formation by IOX1 and 2HG was also restored by NFATc1 overexpression (Appendix Fig S9D). These results suggested that the Blimp1‐NFATc1 axis was a crucial step for Tet2‐ and Tet3‐mediated osteoclast regulation.

Figure 6. Tet2‐ and Tet3‐mediated DNA demethylation is required for the activation of Blimp1‐NFATc1 axis.

-

AScatter plot of fold changes in RNA‐seq data and MeDIP‐seq data. The log2 fold changes in RNA‐seq expression between wild‐type control and Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– BMMs stimulated with RANKL for 2 days are shown on the x‐axis, and log2 fold changes in MeDIP‐seq expression (> 0) are shown on the y‐axis. The names of significant genes are labeled (FDR of differential expression analysis < 0.01, p‐value of differential methylated region analysis < 0.01).

-

BMeDIP‐qPCR analysis to validate regions that are hypermethylated in Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– BMMs stimulated with RANKL for 2 days. Data denote mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 (n = 3–5 biological replicates; t‐test).

-

CGene expression of TET target candidates in BMMs stimulated with RANKL for 2 days. Data denote mean ± s.e.m. **P < 0.01 (n = 4–7 biological replicates; t‐test).

-

DGenome browser view of the expression and the methylation site distribution in the Prdm1 gene locus of control and Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– BMMs stimulated with RANKL for 2 days.

-

EBisulfate sequencing analysis of selected region of the second intron of the Prdm1 gene in control and Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– BMMs stimulated with RANKL for 2 days.

-

FEffect of retroviral NFATc1 expression on osteoclastogenesis of control and Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– BMMs stimulated with RANKL for 3 days. TRAP‐stained cells (left panel) and the number of TRAP‐positive cells with more than three nuclei (right). Scale bars, 100 μm. Data denote mean ± s.e.m. **P < 0.01 (n = 3 biological replicates; ANOVA).

-

GBisulfate sequencing analysis of the selected region of the second intron of the Prdm1 gene in BMMs stimulated with RANKL and culture under 5% and 2% oxygen for 3 days.

-

HEffect of retroviral NFATc1 expression on osteoclastogenesis of BMMs stimulated with RANKL and culture under 5% and 2% oxygen for 5 days. Control and Tet2Rank –/–; Tet3aRank +/– BMMs stimulated with RANKL for 3 days. TRAP‐stained cells (left panel) and the number of TRAP‐positive cells with more than three nuclei (right). Scale bars, 100 μm. Data denote mean ± s.e.m. **P < 0.01 (n = 3 biological replicates; ANOVA).

In order to determine whether Tet2‐ and Tet3‐mediated DNA demethylation is affected by physiological hypoxia and serves as an oxygen sensor in osteoclasts, we investigated DNA methylation levels at the Prdm1 locus in osteoclasts, under conditions of physioxia and physiological hypoxia. A significant difference in DNA methylation was observed between 5% and 2% oxygen, suggesting that Tet2‐ and Tet3‐mediated DNA demethylation was severely impaired by physiological hypoxia (Fig 6G). Furthermore, the expression of both Prdm1 and Nfatc1 under 2% oxygen was lower than that under 5% oxygen, while that of Bcl6 and Mafb was high (Fig 3A and C). NFATc1 overexpression restored osteoclast formation even under 2% oxygen (Fig 6H and Appendix Fig S9E). However, since the extent of the recovery was low, it is conceivable that physiological hypoxia may inhibit osteoclastogenesis by reducing the activity of other oxygen‐dependent dioxygenases as well as TETs. Taken together, these results suggested that the Tet2‐ and Tet3‐mediated Blimp1–NFATc1 axis was crucial step in osteoclastic adaptation to physioxia perturbation.

Discussion

The oxygen tension of the endosteal region wherein the osteoclasts reside was previously determined to be 13.5 mmHg outside the vessels and 21.9 mmHg inside the vessels (Spencer et al, 2014). The widely used 2PLIM method with a cell‐impermeable phosphorescent probe enables the measurement of only extracellular oxygen tension. However, oxygen is mainly stored intracellularly through the function of oxygen storage proteins such as hemoglobin, myoglobin, cytoglobin, and neuroglobin, whereas the dissolved oxygen level in the extracellular fluid is reduced in accordance with Henry’s law. Therefore, the previous method may underestimate the actual cellular oxygen tension in vivo. Here, using an updated 2PLIM method with our newly developed cell‐penetrating phosphorescent probe, we succeeded in determining the physiological range of oxygen tension in the bone marrow at the single‐cell resolution, revealing that the precise oxygen tension experienced by osteoclasts in vivo ranged from 17.4 to 36.4 mmHg. We further demonstrated that energy metabolism in osteoclasts remains unaffected within the physiological range of oxygen tension in vivo. Although cytochrome c oxidase is one of the key enzymes for the respiratory function of mitochondria, the KM for oxygen of cytochrome c oxidase is extremely low (< 0.77 mmHg) (Krab et al, 2011). Therefore, energy metabolism is likely to provide robustness to osteoclasts against hypoxia, at least under both physioxia and physiological hypoxia conditions.

We demonstrated that HIF‐α is induced in osteoclasts and activates the expression of hypoxia‐related genes, but is not dispensable for osteoclastogenesis under both physioxia and physiological hypoxia conditions. Considering that PHDs have a high KM for oxygen, ranging from 87 to 299 mmHg (Wilson et al, 2020), it seems that the HIF–PHD axis is constitutively activated in osteoclasts even under physioxia, and may not be directly involved in mediating the hypoxia response. In contrast, oxygen tension in the cortical tubules of the kidney has been estimated to be 60 mmHg in live mice under conditions of room air inhalation and to be 35 mmHg under conditions of 15% oxygen inhalation (Hirakawa et al, 2015), which is a markedly higher level than that determined in osteoclasts. It is thus reasonable to speculate that PHDs act as key regulators for oxygen sensing and are involved in the regulation of HIF‐target genes such as Epo under changing oxygen conditions in vivo.

Accumulating evidence shows that dioxygenase family members with different affinities for oxygen could be potential oxygen sensors. Indeed, KDM5A‐ or KDM6A‐mediated histone demethylation is severely inhibited by hypoxia, with implications for tumorigenesis (Batie et al, 2019; Chakraborty et al, 2019). However, given their extremely high KM values for oxygen (117 and 260 mmHg, respectively), histone hypermethylation in osteoclasts is likely to be significantly promoted. This may explain why we did not observe an effect of physioxia or physiological hypoxia on the histone methylation status of osteoclasts in this study. Alternatively, we demonstrated that TETs play a pivotal oxygen‐sensing role in osteoclasts. Considering TETs with a KM of 39 mmHg (Laukka et al, 2016), the enzymatic activity of TETs could be markedly attenuated by changing the oxygen tension from 36.9 to 17.4 mmHg. Thus, our findings provide a rational molecular basis for the hypoxia response within the physiological range of oxygen tension in vivo.

Although the effect of hypoxia on osteoclast differentiation has been extensively studied to date (Arnett et al, 2003; Fukuoka et al, 2005; Murata et al, 2017), the conclusion of our analysis was contrary to the conclusion reported in a few previous studies, namely, that oxygen acts as a positive regulator for osteoclast differentiation. The previous studies showed that osteoclast differentiation was promoted by a decrease in oxygen tension in comparison with that in room air condition (18% oxygen as a control). Since such cell culture experiments are performed under supra‐physiological oxygen tension, these results may be misleading, which could be the main cause of discrepancy between the previous data and our present in vivo/in vitro results. Although routine cell culture in room air is one of the mainstays of life science research, primary cell‐based in vitro analysis under physioxia condition may have made our experiments more robust and increased the likelihood that these findings have in vivo relevance.

Materials and Methods

Mice and bone analysis

We generated and genotyped Tet2flox/flox , Tet3flox/flox , Hif1flox/flox , Hif2flox/flox , RANK Cre/+, CX3CR1 Cre/+, Tg(Acp5‐tdTomato), Epo–/– ;Tg(3.3K‐Epo), TcirgGFP/+, and Rosa26GO‐ATeam2/+ mice as previously described (Sun‐Wada et al, 2009; Maeda et al, 2012; Kikuta et al, 2013; Yamazaki et al, 2013; Yona et al, 2013; Semba et al, 2016; Yamamoto et al, 2019; Tanaka et al, 2020). Hif1+/+ ;Hif2+/+ , Hif1flox or +/flox or + ;Hif2flox or +/flox or + , Tet2+/+ ;Tet3+/+ and Tet2flox or +/flox or + ;Tet3flox or +/flox or + littermate mice that did not carry the Cre recombinase were used as control (referred to as control, wild‐type, or wild‐type control). There are no differences in bone phenotype among them. All mice were born and maintained under specific pathogen‐free conditions, and all animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of both Doshisha University and Osaka University. All strains were on the C57BL/6 background. Ten‐week‐old sex‐matched mice were used for experiments unless otherwise mentioned. Animals were randomly included in the experiments according to genotyping results. Animal experiments were conducted in a blinded fashion with respect to the investigator. The numbers of animals used per experiment are stated in the figure legends. Three‐dimensional microcomputed tomography (µCT) analyses and bone morphometric analyses were performed as described previously (Nishikawa et al, 2015; Baba et al, 2018; Suzuki et al, 2020).

To investigate acute hypoxic effect in vivo, we attempted to examine the in vivo effect of hypoxia using the mice under 10% or less oxygen concentration; however as the mice were exposed to these conditions for 10 days, they did not consume food and displayed hypoactivity and lean mass with less bone mass. Therefore, we exposed the mice to 14% oxygen concentration. Oxygen was diluted with more than 97% nitrogen generated by N2 generator (TAITEC) using rotameters to deliver a hypoxic gas mixture into the breathing chamber (Natsume). The oxygen concentration was continuously monitored inside the chamber using gas analyzer (Astec). All of the mice were killed and subjected to µCT and bone morphometric analyses 10 days after exposure.

Two‐photon phosphorescence lifetime and fluorescence lifetime imaging

Intravital microscopy of mouse calvaria bone tissues was performed as described previously (Morimoto et al, 2021). Ten‐ to sixteen‐week‐old mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, the frontoparietal regions of the skull bones were exposed, and then, the internal surfaces of bones adjacent to bone marrow cavity were observed by using two‐photon excitation microscopy. The imaging systems consisted of an upright two‐photon microscope (FVMPE‐RS, Olympus) equipped with a × 25 water‐immersion objective (XLPLN 25XWMP2, N.A. 1.05; Olympus) driven by laser (Mai Tai DeepSee, Ti:Sapphire; Spectra‐Physics) tuned to 750–850 nm. An acousto‐optic modulator (AOM) was placed in the excitation path of two‐photon microscope, enabling fast repetitive on–off switching of the laser excitation. For phosphorescence measurement, the mice were intravenously injected with 8.4 mg/kg BTPDM1 (Yoshihara et al, 2015) before imaging. It has been previously demonstrated that BTPDM1 distributes to most tissues in the body within 2 h after injection and accumulates in the cells of these tissues for at least 24 h. Furthermore, phosphorescence imaging using BTPDM1 determined that oxygen level in hypoxic tumors, renal cortex, and hepatic lobules in live animals ranged from 0.8 to 60 mmHg (Hirakawa et al, 2015; Yoshihara et al, 2015; Mizukami et al, 2020), showing that BTPDM1 has high sensitivity with a wide dynamic range. Phosphorescent and fluorescent and images were collected at a depth of 100–150 μm below the skull bone surface and detected through band‐pass emission filters at 450/50 nm (for NAD(P)H autofluorescence), 525/50 nm (for GFP and EGFP), and 620/60 nm (for tdTomato and BTPDM1). To perform inhalation exposure of mice to low oxygen, oxygen was diluted with more than 97% nitrogen using rotameters (KOFLOC) to deliver gas mixtures, from 21 to 14% oxygen, into the breathing apparatus. To monitor the degree of hypoxia in vivo, a probe attached to the thigh of the mice was used to measure the heart rate, peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2), and breath rate using MOUSEOX PLUS (STARR LifeSciences).

Phosphorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (PLIM) and fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) images were acquired by TCSPC method using DCS‐120 confocal scanning system (Becker & Hickl GmbH/Tokyo Instruments). Single‐photon emission signals were collected through emission filters (450/50 nm for NAD(P)H autofluorescence, 525/50 nm for EGFP of GO‐ATeam2, and 620/60 nm for BTPDM1). SPCImage software (Becker & Hickl GmbH) was used to fit the signal of each pixel to a single‐exponential decay for the phosphorescence of BTPDM1, a double‐exponential decay for the fluorescence of EGFP, and a triple‐exponential decay for the autofluorescence of NAD(P)H according to the following equations:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where x and y are the pixel coordinates, N is the measured counts, A is the amplitude, and t is the lifetime. Chi‐square contains the squared difference between all measured data points and the modeled decay, each of which is weighted according to the expected standard deviation of the measured intensity and (for the reduced chi‐square) the total number of data points:

| (4) |

Here, N(tk ) is the measured counts at time tk , N c(tk ) is the modeled number of counts at time tk , and n is the number of data points. A good fit was characterized by a value of chi‐square close to 1 (at least, less than 1.34). We extracted both best‐fit amplitudes and lifetimes from the region of interests (ROIs) corresponding to osteoclasts. The average lifetime for each ROIs can then be calculated using the following equations:

| (5) |

where n is 0, 1, and 2 for a single‐exponential, a double‐exponential, and a triple‐exponential decay, respectively.

The FRET efficiency of GO‐ATeam2 is defined as the proportion of the donor protein, EGFP, that have transferred excitation state energy to the acceptor protein, OFP. It can be expressed in terms of measurable quantities as 1−τ FRET/τ d. τ d is the amplitude‐weighted average lifetime of the donor.

For in vitro analysis to generate a calibration curve of phosphorescence lifetime vs. oxygen tension, BMMs stimulated with RANKL for 2 days were treated with 10 μM BTPDM1 and then were observed by using two‐photon excitation microscopy equipped with cell culture incubator (Stage top incubator, Tokai Hit). While diluting oxygen concentration in the culture media with more than 97% nitrogen using rotameters (KOFLOC), phosphorescent images were collected through band‐pass emission filters at 620/60 nm (BTPDM1) at each concentration of oxygen in the culture media (from 6 to 0% oxygen, which was monitored using Microx 4 [TAITEC]). PLIM images were acquired by TCSPC method using DCS‐120 confocal scanning system (Becker & Hickl GmbH/Tokyo Instruments). Single‐photon emission signals were collected through emission filters (620/60 nm). SPCImage software (Becker & Hickl GmbH) was used to fit the signal of each pixel to a single‐exponential decay according to the equation (1). The phosphorescence quenching due to dissolved oxygen in solution can be examined by the following Stern–Volmer equation:

| (6) |

in which τp is the phosphorescence lifetime and kq is a bimolecular quenching rate constant.

Cell culture

In vitro osteoclast differentiation was described previously (Nishikawa et al, 2010, 2013, 2015). Briefly, for in vitro differentiation, bone marrow‐derived cells cultured with 10 ng/ml M‐CSF (Miltenyi Biotec) for 2 days were used as osteoclast precursor cells and bone marrow‐derived monocyte/macrophage precursor cells (BMMs) and were further cultured with 50 ng/ml RANKL (PeproTech) in the presence of 10 ng/ml M‐CSF for 3 days. Tartrate‐resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP)‐positive multinucleated cells (MNCs; TRAP+MNCs, more than three nuclei) were counted. Exposure of cell cultures to physioxia (5% oxygen) and physiological hypoxia (2% oxygen) was undertaken in the hypoxia workstation IN VIVO 300 (Ruskinn) and multi‐gas incubator (Astec).

Quantitative RT–PCR analysis

Quantitative RT–PCR analysis was performed as described previously (Sakaguchi et al, 2018). Briefly, total RNA and cDNA were prepared using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), respectively, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real‐time PCR was performed with a Thermal Cycler Dice Real Time System (TaKaRa Bio) using SYBR Premix EX Taq (TaKaRa Bio). The primer sequences are listed in Appendix Table S1.

Transcriptome analysis

For RNA‐seq analysis, library preparation was performed using a TruSeq Stranded mRNA Sample Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform in a 75‐base single‐end mode. Illumina Casava1.8.2 software was used for basecalling. Sequenced reads were mapped to the mouse reference genome sequences (mm10) using TopHat v2.0.13 in combination with Bowtie2 ver. 2.2.3 and SAMtools ver. 0.1.19. Gene expression quantification was performed by htseq‐count (Anders et al, 2015). Differential expression analysis was performed using the Bioconductor package, edgeR (Robinson et al, 2010).

GeneChip analysis was performed as described previously (Nishikawa et al, 2010). Briefly, total RNA was converted into cDNA by reverse transcription. Biotinylated cRNA was then synthesized by in vitro transcription. After cRNA fragmentation, hybridization with the mouse genome 430 2.0 array (Affymetrix) was performed. The core data set has been deposited in the Genome Network Platform (http://genomenetwork.nig.ac.jp/).

Metabolome analyses by ion‐chromatography mass spectrometry

Metabolites of central metabolic pathways were extracted from the cultured cells for metabolome analyses as described previously (Semba et al, 2016). Briefly, the cells were scraped with methanol containing an internal standard, followed by the addition of chloroform and ultrapure water (Wako) to the aqueous phase to obtain the extracted hydrophilic metabolites. The aqueous phase was subjected to centrifugal filtration through a 5‐kDa‐cutoff filter tube (Human Metabolome Technologies), concentrated in a vacuum concentrator, and then dissolved in ultrapure water for IC‐MS analysis (Hu et al, 2015). For metabolome analysis, metabolites were measured using an Orbitrap‐type MS (Q‐Exactive Focus; Thermo Fisher Scientific) connected to a high‐performance IC system (ICS‐5000+, Thermo Fisher Scientific), as previously described (Semba et al, 2016; Okuno et al, 2020).

DNA methylation analysis

We prepared genomic DNA from cultured cells using the GenElute Mammalian Genomic DNA Miniprep Kit (Sigma‐Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For bisulfate genomic sequencing, genomic DNA was subjected to bisulfate conversion with the EpiTect Bisulfate Kit (Qiagen). Following bisulfate PCR, the products were cloned into the pGEM‐T Easy vector (Promega) and subjected to sequencing. The primer sequences are listed in Appendix Table S1.

Before carrying out methylated DNA immunoprecipitation (MeDIP)‐seq and MeDIP‐quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis, we sonicated genomic DNA to produce random fragments ranging in size up to 150 bp using DNA shearing system (Covaris). Methylated DNA was enriched from the fragmented genomic DNA using the MEDIP Kit (Active Motif). For MeDIP‐seq analysis, the Illumina libraries were prepared using KAPA Hyper Prep Kit (Kapa Biosystems) and TruSeq DNA UD Indexes (Illumina) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Paired‐end sequencing (100 bp × 2) was performed using HiSeq3000 (Illumina). Sequenced reads were trimmed with Trim Galore and mapped to the mouse genome (mm10) with Bowtie2 (Langmead & Salzberg, 2012). For the analysis of differentially methylated regions, peak calling and significance tests were performed with the R/Bioconductor package MEDIPS (Lienhard et al, 2014). BedGraph and BigWig files were generated and viewed using the UCSC Genome Browser.

For MeDIP‐qPCR analysis, we carried out real‐time PCRs with input DNA and the immunoprecipitated methylated DNA using SYBR Premix EX Taq (TaKaRa Bio). To evaluate the relative enrichment of target sequences after MeDIP‐qPCR, we calculated the ratios of the signals for immunoprecipitated DNA versus input DNA. The primer sequences are listed in Appendix Table S1.

Gene transfer

The retroviral vector pMX‐NFATc1‐IRES‐GFP was constructed by inserting DNA fragments encoding NFATc1 into pMX‐IRES‐GFP (Morita et al, 2000). Retroviral packaging was performed by transfecting the plasmids into Plat‐E cells using FuGENE6 as described previously (Morita et al, 2000). Ten hours after inoculation with retroviruses, BMMs were stimulated with RANKL.

RNA transfection experiment was performed as described previously (Nishikawa & Ishii, 2021). Briefly, synthetic capped RNA was made with the mMESSAGE mMACHINE T7 ULTRA Transcription Kit (Thermo) using linearized DNA of the pcDNA3‐TET derivatives and then purified by RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). RNA transfections were performed with the Lipofectamine MessengerMAX (Thermo). Two hours after transfection with RNA, BMMs were stimulated with RANKL.

Immunoblot analysis

Cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis using antibodies specific for Tet1 (Active Motif, 614444), Tet2 (Abcam, ab124297), Tet3 (GeneTex, GTX121453), Blimp1 (Novus, NB600‐235), NFATc1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc‐7294), TRAP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc‐30833), Ctsk (Daiichi Finechemical, F‐95), HIF‐1α (CST, #36169), HIF‐2α (Abcam, ab199), H3K9me3 (FUJIFILM, MABI0308), H3K27me3 (FUJIFILM, MABI0323), H3K36me3 (FUJIFILM, MABI0333), H3 (CST, #4499), 5mC (Active Motif, 39649), and Lmnb (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc‐6217). Whole‐cell extracts were prepared by lysis in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Iwamoto et al, 2016).

Flow cytometry analysis

Single‐cell suspensions were incubated with anti‐CD16/CD32 for 10 min and then stained with phycoerythrin‐conjugated anti‐CD11b (M1/70; eBioscience) in flow cytometry (FACS) buffer (1× phosphate‐buffered saline [PBS], 4% heat‐inactivated fetal calf serum, and 2 mM EDTA) for 15 min.

For BrdU detection, CD11b‐stained cells were fixed and permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (BD Biosciences) for 15 min and then washed with 1×Perm/Wash buffer (BD Biosciences). The cells were further permeabilized in Cytoperm plus buffer (BD Biosciences) for 10 min and then washed with 1×Perm/Wash buffer. The washed cells were resuspended in Cytofix/Cytoperm solution for 5 min and then washed with 1XPerm/Wash buffer; they were treated with DNase I and incubated at 37°C for 1 h and then washed aging with 1×Perm/Wash buffer. The cells were then stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate‐conjugated anti‐BrdU (3D4; BioLegend) for 15 min.

For Annexin V detection, CD11b‐stained cells were stained with allophycoerythrin‐conjugated anti‐Annexin V (BD Biosciences) in 1×Annexin V binding buffer (BD Biosciences) for 20 min.

The stained cells were analyzed on a CytoFLEX (Beckman Coulter). FACS data were statistically analyzed with FlowJo software (BD Biosciences).

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. Statistical analysis was performed using the unpaired two‐tailed Student’s t‐test for comparisons between two groups and analysis of variance with the Bonferroni post hoc test for comparisons among three or more groups (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; NS, not significant, throughout the paper). All data met the assumption of statistical tests and had a normal distribution, and variance was similar between groups that were statistically compared. Replicates used were biological replicates. The results are representative examples of more than three independent experiments. We estimated the sample size considering the variation and mean of the samples. We tried to reach the conclusion using as small a size of samples as possible. We usually excluded samples if we observed any abnormality in terms of size, weight, or apparent disease symptoms in mice before performing experiments. However, we did not exclude animals here, as we did not observe any abnormalities in the present study.

Author contributions

KN conceptualized the study; KN, TY, AN, JK, YS, RS, MS, ST, YM, MI investigated the study; SS, DO, DM, and HM involved in formal analysis; NS, NT, HS, MY, YK, HK, and MY contributed to methodology; KN wrote—original draft.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict interest.

Supporting information

Appendix

Expanded View Figures PDF

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Grants‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research (B) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) (18H02614 to KN); Grants‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas from the JSPS (17H05530 to KN); CREST, Japan Science and Technology Agency (to MI); Grants‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research (S) from the JSPS (19H05657 to MI); Grants‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas from the JSPS (26111001 and 26111004 to YM); grants from the Takeda Science Foundation (to KN and MI); Toray Science Foundation (to KN); the Nakatani Foundation (to KN); Yamada Science Foundation (to KN); LOTTE Foundation (to KN); Suzuken Memorial Foundation (to KN); Terumo Life Science Foundation (to KN); and infrastructure of metabolomics was partly supported by JST ERATO Suematsu Gas Biology Project (to MS).

EMBO reports (2021) 22: e53035.

Contributor Information

Keizo Nishikawa, Email: kenishik@mail.doshisha.ac.jp.

Yasuo Mori, Email: mori@sbchem.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Masaru Ishii, Email: mishii@icd.med.osaka-u.ac.jp.

Data availability

The RNA‐seq and MBD‐seq data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession code GSE156130 [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE156130]). GeneChip data have been deposited in the Genome Network Platform (http://genomenetwork.nig.ac.jp/).

References

- Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W (2015) HTSeq–a Python framework to work with high‐throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31: 166–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett TR, Gibbons DC, Utting JC, Orriss IR, Hoebertz A, Rosendaal M, Meghji S (2003) Hypoxia is a major stimulator of osteoclast formation and bone resorption. J Cell Physiol 196: 2–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba M, Endoh M, Ma W, Toyama H, Hirayama A, Nishikawa K, Takubo K, Hano H, Hasumi H, Umemoto T et al (2018) Folliculin regulates osteoclastogenesis through metabolic regulation. J Bone Miner Res 33: 1785–1798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batie M, Frost J, Frost M, Wilson JW, Schofield P, Rocha S (2019) Hypoxia induces rapid changes to histone methylation and reprograms chromatin. Science 363: 1222–1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle WJ, Simonet WS, Lacey DL (2003) Osteoclast differentiation and activation. Nature 423: 337–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty AA, Laukka T, Myllykoski M, Ringel AE, Booker MA, Tolstorukov MY, Meng YJ, Meier SR, Jennings RB, Creech AL et al (2019) Histone demethylase KDM6A directly senses oxygen to control chromatin and cell fate. Science 363: 1217–1222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Y, Zhao Z, Sant DW, Zhu G, Greenblatt SM, Liu L, Wang J, Cao Z, Tho JC, Chen S et al (2018) Tet2 regulates osteoclast differentiation by interacting with Runx1 and maintaining genomic 5‐Hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC). Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 16: 172–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirckx N, Tower RJ, Mercken EM, Vangoitsenhoven R, Moreau‐Triby C, Breugelmans T, Nefyodova E, Cardoen R, Mathieu C, Van der Schueren B et al (2018) Vhl deletion in osteoblasts boosts cellular glycolysis and improves global glucose metabolism. J Clin Invest 128: 1087–1105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa ME, Abdel‐Wahab O, Lu C, Ward PS, Patel J, Shih A, Li Y, Bhagwat N, Vasanthakumar A, Fernandez HF et al (2010) Leukemic IDH1 and IDH2 mutations result in a hypermethylation phenotype, disrupt TET2 function, and impair hematopoietic differentiation. Cancer Cell 18: 553–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuoka H, Aoyama M, Miyazawa K, Asai K, Goto S (2005) Hypoxic stress enhances osteoclast differentiation via increasing IGF2 production by non‐osteoclastic cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 328: 885–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guntur AR, Le PT, Farber CR, Rosen CJ (2014) Bioenergetics during calvarial osteoblast differentiation reflect strain differences in bone mass. Endocrinology 155: 1589–1595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammarlund EU, Flashman E, Mohlin S, Licausi F (2020) Oxygen‐sensing mechanisms across eukaryotic kingdoms and their roles in complex multicellularity. Science 370: eaba3512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi M, Nakashima T, Taniguchi M, Kodama T, Kumanogoh A, Takayanagi H (2012) Osteoprotection by semaphorin 3A. Nature 485: 69–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa Y, Yoshihara T, Kamiya M, Mimura I, Fujikura D, Masuda T, Kikuchi R, Takahashi I, Urano Y, Tobita S et al (2015) Quantitating intracellular oxygen tension in vivo by phosphorescence lifetime measurement. Sci Rep 5: 17838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsila M, Koivunen P, Gunzler V, Kivirikko KI, Myllyharju J (2003) Characterization of the human prolyl 4‐hydroxylases that modify the hypoxia‐inducible factor. J Biol Chem 278: 30772–30780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkinson RJ, Tumber A, Yapp C, Chowdhury R, Aik W, Che KH, Li XS, Kristensen JBL, King ONF, Chan MC et al (2013) 5‐Carboxy‐8‐hydroxyquinoline is a broad spectrum 2‐oxoglutarate oxygenase inhibitor which causes iron translocation. Chem Sci 4: 3110–3117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S, Wang J, Ji EH, Christison T, Lopez L, Huang Y (2015) Targeted metabolomic analysis of head and neck cancer cells using high performance ion chromatography coupled with a Q exactive HF mass spectrometer. Anal Chem 87: 6371–6379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii KA, Fumoto T, Iwai K, Takeshita S, Ito M, Shimohata N, Aburatani H, Taketani S, Lelliott CJ, Vidal‐Puig A et al (2009) Coordination of PGC‐1beta and iron uptake in mitochondrial biogenesis and osteoclast activation. Nat Med 15: 259–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S, D'Alessio AC, Taranova OV, Hong K, Sowers LC, Zhang Y (2010) Role of Tet proteins in 5mC to 5hmC conversion, ES‐cell self‐renewal and inner cell mass specification. Nature 466: 1129–1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto Y, Nishikawa K, Imai R, Furuya M, Uenaka M, Ohta Y, Morihana T, Itoi‐Ochi S, Penninger JM, Katayama I et al (2016) Intercellular communication between keratinocytes and fibroblasts induces local osteoclast differentiation: a Mechanism underlying cholesteatoma‐induced bone destruction. Mol Cell Biol 36: 1610–1620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaakkola P, Mole DR, Tian Y‐M, Wilson MI, Gielbert J, Gaskell SJ, Kriegsheim AV, Hebestreit HF, Mukherji M, Schofield CJ et al (2001) Targeting of HIF‐alpha to the von Hippel‐Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2‐regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science 292: 468–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinina S, Breymayer J, Schafer P, Calzia E, Shcheslavskiy V, Becker W, Ruck A (2016) Correlative NAD(P)H‐FLIM and oxygen sensing‐PLIM for metabolic mapping. J Biophotonics 9: 800–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuta J, Wada Y, Kowada T, Wang ZE, Sun‐Wada G‐H, Nishiyama I, Mizukami S, Maiya N, Yasuda H, Kumanogoh A et al (2013) Dynamic visualization of RANKL and Th17‐mediated osteoclast function. J Clin Invest 123: 866–873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Kim JH, Lee J, Jin HM, Kook H, Kim KK, Lee SY, Kim N (2007) MafB negatively regulates RANKL‐mediated osteoclast differentiation. Blood 109: 3253–3259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krab K, Kempe H, Wikstrom M (2011) Explaining the enigmatic K(M) for oxygen in cytochrome c oxidase: a kinetic model. Biochim Biophys Acta 1807: 348–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Salzberg SL (2012) Fast gapped‐read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9: 357–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laukka T, Mariani CJ, Ihantola T, Cao JZ, Hokkanen J, Kaelin WG Jr, Godley LA, Koivunen P (2016) Fumarate and succinate regulate expression of hypoxia‐inducible genes via TET enzymes. J Biol Chem 291: 4256–4265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WC, Guntur AR, Long F, Rosen CJ (2017) Energy metabolism of the osteoblast: implications for osteoporosis. Endocr Rev 38: 255–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lienhard M, Grimm C, Morkel M, Herwig R, Chavez L (2014) MEDIPS: genome‐wide differential coverage analysis of sequencing data derived from DNA enrichment experiments. Bioinformatics 30: 284–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo J, Horowitz M, Choi Y (2008) Osteoimmunology: interactions of the bone and immune system. Endocr Rev 29: 403–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda K, Kobayashi Y, Udagawa N, Uehara S, Ishihara A, Mizoguchi T, Kikuchi Y, Takada I, Kato S, Kani S et al (2012) Wnt5a‐Ror2 signaling between osteoblast‐lineage cells and osteoclast precursors enhances osteoclastogenesis. Nat Med 18: 405–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majmundar AJ, Wong WJ, Simon MC (2010) Hypoxia‐inducible factors and the response to hypoxic stress. Mol Cell 40: 294–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell PH, Wiesener MS, Chang GW, Clifford SC, Vaux EC, Cockman ME, Wykoff CC, Pugh CW, Maher ER, Ratcliffe PJ (1999) The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia‐inducible factors for oxygen‐dependent proteolysis. Nature 399: 271–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyauchi Y, Ninomiya K, Miyamoto H, Sakamoto A, Iwasaki R, Hoshi H, Miyamoto K, Hao W, Yoshida S, Morioka H et al (2010) The Blimp1‐Bcl6 axis is critical to regulate osteoclast differentiation and bone homeostasis. J Exp Med 207: 751–762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizukami K, Katano A, Shiozaki S, Yoshihara T, Goda N, Tobita S (2020) In vivo O2 imaging in hepatic tissues by phosphorescence lifetime imaging microscopy using Ir(III) complexes as intracellular probes. Sci Rep 10: 21053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto A, Kikuta J, Nishikawa K, Sudo T, Uenaka M, Furuya M, Hasegawa T, Hashimoto K, Tsukazaki H, Seno S et al (2021) SLPI is a critical mediator that controls PTH‐induced bone formation. Nat Commun 12: 2136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita S, Kojima T, Kitamura T (2000) Plat‐E: an efficient and stable system for transient packaging of retroviruses. Gene Ther 7: 1063–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata K, Fang C, Terao C, Giannopoulou EG, Lee YJ, Lee MJ, Mun SH, Bae S, Qiao Y, Yuan R et al (2017) Hypoxia‐sensitive COMMD1 integrates signaling and cellular metabolism in human macrophages and suppresses osteoclastogenesis. Immunity 47: 66–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano M, Imamura H, Nagai T, Noji H (2011) Ca(2)(+) regulation of mitochondrial ATP synthesis visualized at the single cell level. ACS Chem Biol 6: 709–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa K, Nakashima T, Hayashi M, Fukunaga T, Kato S, Kodama T, Takahashi S, Calame K, Takayanagi H (2010) Blimp1‐mediated repression of negative regulators is required for osteoclast differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 3117–3122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa K, Iwamoto Y, Ishii M (2013) Development of an in vitro culture method for stepwise differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells into mature osteoclasts. J Bone Miner Metab 32: 331–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa K, Iwamoto Y, Kobayashi Y, Katsuoka F, Kawaguchi S, Tsujita T, Nakamura T, Kato S, Yamamoto M, Takayanagi H et al (2015) DNA methyltransferase 3a regulates osteoclast differentiation by coupling to an S‐adenosylmethionine‐producing metabolic pathway. Nat Med 21: 281–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa K, Ishii M (2021) Novel method for gain‐of‐function analyses in primary osteoclasts using a non‐viral gene delivery system. J Bone Miner Metab 39: 353–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohh M, Park CW, Ivan M, Hoffman MA, Kim TY, Huang LE, Pavletich N, Chau V, Kaelin WG (2000) Ubiquitination of hypoxia‐inducible factor requires direct binding to the beta‐domain of the von Hippel‐Lindau protein. Nat Cell Biol 2: 423–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuno D, Sugiura Y, Sakamoto N, Tagod MSO, Iwasaki M, Noda S, Tamura A, Senju H, Umeyama Y, Yamaguchi H et al (2020) Comparison of a novel bisphosphonate prodrug and zoledronic acid in the induction of cytotoxicity in human Vgamma2Vdelta2 T cells. Front Immunol 11: 1405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palazon A, Goldrath AW, Nizet V, Johnson RS (2014) HIF transcription factors, inflammation, and immunity. Immunity 41: 518–528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramasamy SK, Kusumbe AP, Wang L, Adams RH (2014) Endothelial Notch activity promotes angiogenesis and osteogenesis in bone. Nature 507: 376–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan JN, Lim J, Shi Y, Joeng KS, Arbeit JM, Shohet RV, Long F (2014) Up‐regulation of glycolytic metabolism is required for HIF1alpha‐driven bone formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 8673–8678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK (2010) edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26: 139–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussakis E, Li Z, Nichols AJ, Evans CL (2015) Oxygen‐sensing methods in biomedicine from the macroscale to the microscale. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 54: 8340–8362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumsey WL, Vanderkooi JM, Wilson DF (1988) Imaging of phosphorescence: a novel method for measuring oxygen distribution in perfused tissue. Science 241: 1649–1651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan HE, Lo J, Johnson RS (1998) HIF‐1 alpha is required for solid tumor formation and embryonic vascularization. EMBO J 17: 3005–3015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan HE, Poloni M, McNulty W, Elson D, Gassmann M, Arbeit JM, Johnson RS (2000) Hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1alpha is a positive factor in solid tumor growth. Cancer Res 60: 4010–4015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi Y, Nishikawa K, Seno S, Matsuda H, Takayanagi H, Ishii M (2018) Roles of enhancer RNAs in RANKL‐induced osteoclast differentiation identified by genome‐wide cap‐analysis of gene expression using CRISPR/Cas9. Sci Rep 8: 7504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semba H, Takeda N, Isagawa T, Sugiura Y, Honda K, Wake M, Miyazawa H, Yamaguchi Y, Miura M, Jenkins DM et al (2016) HIF‐1alpha‐PDK1 axis‐induced active glycolysis plays an essential role in macrophage migratory capacity. Nat Commun 7: 11635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza GL (2002) HIF‐1 and tumor progression: pathophysiology and therapeutics. Trends Mol Med 8: S62–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solaini G, Baracca A, Lenaz G, Sgarbi G (2010) Hypoxia and mitochondrial oxidative metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta 1797: 1171–1177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer JA, Ferraro F, Roussakis E, Klein A, Wu J, Runnels JM, Zaher W, Mortensen LJ, Alt C, Turcotte R et al (2014) Direct measurement of local oxygen concentration in the bone marrow of live animals. Nature 508: 269–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun‐Wada GH, Tabata H, Kawamura N, Aoyama M, Wada Y (2009) Direct recruitment of H+‐ATPase from lysosomes for phagosomal acidification. J Cell Sci 122: 2504–2513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Uruno A, Yumoto A, Taguchi K, Suzuki M, Harada N, Ryoke R, Naganuma E, Osanai N, Goto A et al (2020) Nrf2 contributes to the weight gain of mice during space travel. Commun Biol 3: 496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayanagi H (2007) Osteoimmunology: shared mechanisms and crosstalk between the immune and bone systems. Nat Rev Immunol 7: 292–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S, Ise W, Inoue T, Ito A, Ono C, Shima Y, Sakakibara S, Nakayama M, Fujii K, Miura I et al (2020) Tet2 and Tet3 in B cells are required to repress CD86 and prevent autoimmunity. Nat Immunol 21: 950–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitelbaum SL, Ross FP (2003) Genetic regulation of osteoclast development and function. Nat Rev Genet 4: 638–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thienpont B, Steinbacher J, Zhao H, D'Anna F, Kuchnio A, Ploumakis A, Ghesquiere B, Van Dyck L, Boeckx B, Schoonjans L et al (2016) Tumour hypoxia causes DNA hypermethylation by reducing TET activity. Nature 537: 63–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsagaratou A, Rao A (2013) TET proteins and 5‐methylcytosine oxidation in the immune system. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 78: 1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]