Abstract

The Spemann and Mangold Organizer (SMO) is of fundamental importance for dorsal ventral body axis formation during vertebrate embryogenesis. Maternal Huluwa (Hwa) has been identified as the dorsal determinant that is both necessary and sufficient for SMO formation. However, it remains unclear how Hwa is regulated. Here, we report that the E3 ubiquitin ligase zinc and ring finger 3 (ZNRF3) is essential for restricting the spatial activity of Hwa and therefore correct SMO formation in Xenopus laevis. ZNRF3 interacts with and ubiquitinates Hwa, thereby regulating its lysosomal trafficking and protein stability. Perturbation of ZNRF3 leads to the accumulation of Hwa and induction of an ectopic axis in embryos. Ectopic expression of ZNRF3 promotes Hwa degradation and dampens the axis‐inducing activity of Hwa. Thus, our findings identify a substrate of ZNRF3, but also highlight the importance of the regulation of Hwa temporospatial activity in body axis formation in vertebrate embryos.

Keywords: Hwa, Spemann and Mangold organizer, ubiquitination, ZNRF3

Subject Categories: Development, Post-translational Modifications & Proteolysis, Signal Transduction

The transmembrane E3 ubiquitin ligases ZNRF3 ubiquitinates and promotes the lysosomal degradation of the dorsal determinant Huluwa (Hwa), and ultimately safeguards dorsal body axis formation during vertebrate embryogenesis.

Introduction

Formation of the Spemann‐Mangold Organizer (SMO) during the early vertebrate embryogenesis is a nodal event essential for transforming the spherical fertilized egg into a tadpole with obvious three‐dimensional structures (Harland & Gerhart, 1997; De Robertis et al, 2000; Niehrs, 2004; Heasman, 2006). Extensive studies in model vertebrate organisms have revealed common themes of the molecular function of SMO. The SMO secrets multiple antagonists of the BMP signaling to coordinate cell fate diversification along the dorsoventral body axis, and a panel of Wnt antagonists to promote the anteroposterior body axis formation (De Robertis et al, 2000; Heasman, 2006). That how the SMO is induced to form has been a long‐standing problem in the field of developmental study.

Elegant experimental studies traced the SMO inducing activities from the fertilized egg back to the full‐grown oocytes, thus the term of the maternal dorsal determinant(s) (Scharf & Gerhart, 1980; Ubbels et al, 1983; Vincent et al, 1986; Vincent & Gerhart, 1987; Kageura, 1997). The findings in Xenopus laevis that depletion of maternal β‐catenin causes failure of SMO formation and ventralized development put forward the hypothesis that Wnt/β‐catenin signaling pathway is involved in the SMO induction (Heasman et al, 1994, 2000). Consistently, ectopic expression of β‐catenin stabilizing reagents such as the canonical Wnt ligand and/or GSK3β inhibitors exhibited equivalent effects of the SMO transplantation, i.e., causing duplication of the dorsal body axis (He et al, 1995, 1997). As the effector of the Wnt signaling (Nusse & Clevers, 2017; Zhan et al, 2017), β‐catenin together with transcriptional factors in the TCF3/LEF1 family activates the SMO specific genes (Molenaar et al, 1996; Brannon et al, 1997; Heasman et al, 2000; Kelly et al, 2000; Yang et al, 2002; Bellipanni et al, 2006; Heasman, 2006; Blythe et al, 2009; Fuentes et al, 2020). While the enrichment of β‐catenin in one side of the cleavage and blastula stage embryos has been observed in Xenopus laevis and zebrafish (Schneider et al, 1996; Larabell et al, 1997; Rowning et al, 1997), β‐catenin has been appreciated as the indispensable effector of the maternal dorsal determinant(s) but not the latter per se. Loss‐of‐function studies had ascribed the maternally localized Wnt11b as a necessary component for the SMO induction and the dorsal body axis development in Xenopus laevis (Tao et al, 2005; Kofron et al, 2007; Cha et al, 2008). However, ectopic expression of Wnt11b in cleavage stage Xenopus embryos is unable to cause duplication of the dorsal axis, suggesting it is tightly regulated during the dorsal determining process (Kofron et al, 2007; Huang et al, 2015). In addition, multiple lines of evidence from studies in zebrafish indicate the maternal dorsal determining activities do not seem to involve a Wnt ligand or Disheveled proteins (Xing et al, 2018; Shi, 2020). The molecular identity of a conserved maternal dorsal determinant had remained mysterious.

Our recent study has identified a novel membrane protein dubbed Huluwa (Hwa) that is both necessary and sufficient for the SMO induction and the dorsal body axis development in Xenopus laevis and zebrafish (Yan et al, 2018). Evidence from loss‐ and gain‐of‐function analyses together its characteristic expression patterns in the oocytes and fertilized eggs strongly support the notion that Hwa is a conserved component of the maternal dorsal determinant in Xenopus and zebrafish. Hwa promotes tankyrase‐mediated degradation of Axin and consequently the stabilization of β‐catenin (Yan et al, 2018). Ectopic expression of Hwa rescues the loss of the dorsal body axis in embryos depleted of maternal Wnt11b or Lrp6 (Yan et al, 2018). It is therefore of great significance to investigate the regulation of Hwa during early embryonic development and how to restrict the spatiotemporal activity of Hwa.

ZNRF3 as a single trans‐membrane E3 ubiquitin ligase has been identified to regulate many developmental processes in model vertebrates. In mammalians, ZNRF3 has been implicated in sex determination (Harris et al, 2018) and limb development (Szenker‐Ravi et al, 2018). Znrf3‐deficient mouse died around birth (Hao et al, 2012), preventing a detailed assessment of ZNRF3 function in early mammalian development. Interestingly, perturbation of ZNRF3 in zebrafish embryos produced phenotypes characteristic of convergent extension defects, such as a shortened body axis and disordered somites (Hao et al, 2012). Overexpression of a ZNRF3‐dominant negative mutant (ZNRF3ΔRING) results in the loss of anterior neural structures in zebrafish embryos and axis duplication in Xenopus embryos (Hao et al, 2012). Biochemically, ZNRF3 functions as a negative regulator of the Wnt signaling through selectively ubiquitinating frizzled receptors for degradation (Hao et al, 2012; Koo et al, 2012).

Here, we identify ZNRF3 as an E3 ligase of Hwa ubiquitination from a Hwa‐interactome screen. We provide evidence that ZNRF3 plays pivotal roles in SMO and dorsal axis formation through promoting the lysosomal degradation of Hwa. These results reveal an important missing piece in the dynamic molecular network governing Hwa stability and the Spemann‐Mangold organizer formation.

Results

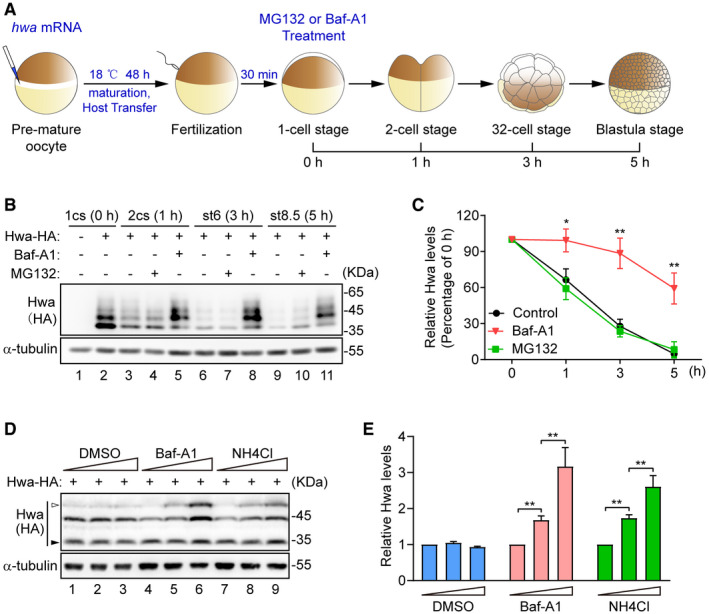

Hwa degrades through the lysosomal degradation pathway

To investigate the degradation of Hwa protein, we developed an assay using Xenopus oocytes and embryos as expression systems. Briefly, manually defolliculated full‐grown oocytes were cultured for 48 h followed by the host transfer assisted fertilization. During the in vitro culture period, oocytes were injected with synthetic mRNA encoding HA‐tagged Huluwa (Hwa‐HA). Hwa‐expressing and control (un‐ injected) embryos were dejellied 30 min postfertilization and then cultured in buffered salt with or without proteasome inhibitor MG132 or lysosome inhibitor bafilomycin‐A1 (Baf‐A1). The embryos were then collected at 1, 3, and 5 h postinhibitor application for immunoblotting analyses (Fig 1A). In untreated embryos, Hwa protein underwent rapid degradation (Fig 1B, lanes 2, 3, 6, 9; and C). Baf‐A1 treatment efficiently prevented the fast degradation of Hwa during the time period of observation (Fig 1B, lanes 5, 8, 11 versus lanes 3, 6, 9; and C), while MG132 had little effect on this process (Fig 1B, lanes 4, 7, 10 versus lanes 3, 6, 9; and C). Consistent results were obtained in HEK293T cells transfected with Hwa‐HA. In the presence of lysosome inhibitors Baf‐A1 or NH4Cl, Hwa levels were apparently increased in a dose‐dependent manner (Fig 1D and E). These data suggest that Hwa rapidly degrades through lysosomal pathway during embryonic development.

Figure 1. Hwa degraded through lysosomal pathway.

- Illustration of experiment design. hwa mRNA (100 pg) was injected into oocytes at stage VI. Embryos were treated with 100 nM Baf‐A1 or 20 µM MG132 at 1‐cell stage and collected at indicated stages.

- Western blot analysis for Hwa performed with lysates from embryos treated as indicated in (A). 1cs, 1‐cell stage; 2cs, 2‐cell stage; st6, 32‐cell stage; st8.5, blastula stage. Blots are representative of three independent experiments.

- Densitometry analysis of Hwa bands from the Western blot in (B) for corresponding lanes normalized to α‐tubulin. n = 3 independent experiments, mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by unpaired t test.

- Western blot analysis of exogenous Hwa in HEK293T cells. Treatment of cells with lysosome inhibitors bafilomycin A1 (Baf‐A1) and NH4Cl for 24 h, DMSO was used as control. Dosage of Baf‐A1: 10, 50, 100 nM; dosage of NH4Cl: 2.5, 5, 10 mM. Hwa with modification is indicated by white arrow; degraded Hwa is indicated by black arrow. Blots are representative of three independent experiments.

- Densitometry analysis of Hwa bands from the Western blot in (D) for corresponding lanes normalized to α‐tubulin. n = 3 independent experiments, mean ± SEM, **P < 0.01 by unpaired t test.

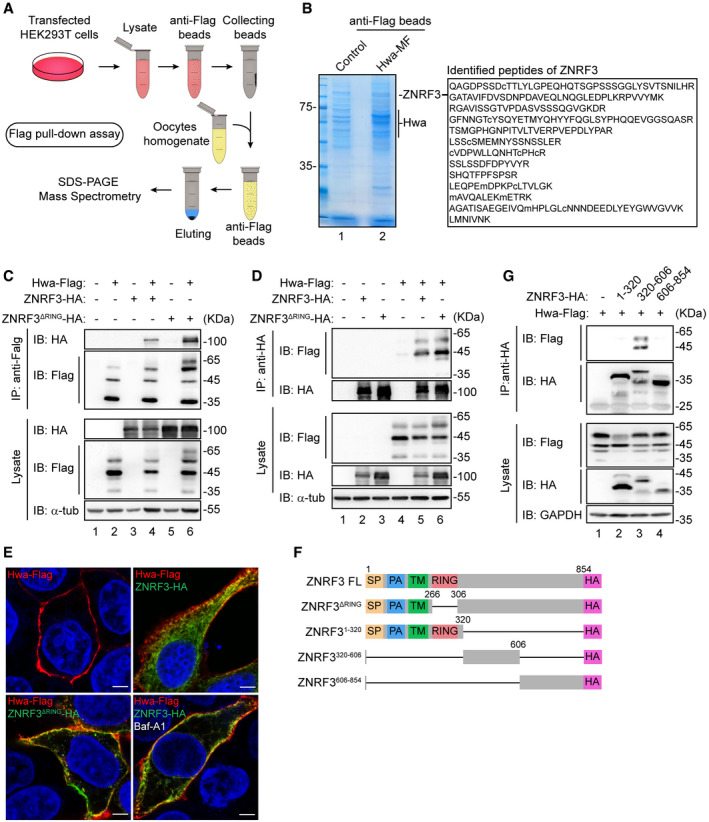

Hwa interacts with ZNRF3

To uncover regulators of Hwa protein, we used affinity isolation combined with mass spectrometry (MS) to identify Hwa‐associated proteins. The C‐terminally Myc‐Flag‐tagged Hwa (Hwa‐MF for short) purified from HEK293T cells was incubated with homogenates prepared from the Xenopus full‐grown oocytes. The purified immunoprecipitants were then subjected to MS analysis (Fig 2A). Notably, the peptides of ZNRF3, a membrane‐associated RING‐type E3 ubiquitin ligase, were identified in Hwa‐MF immunoprecipitants but not in control (Fig 2B), indicating ZNRF3 possibly interacts with Hwa. Subsequent co‐immunoprecipitation assays using lysates from HEK239T cells co‐transfected with Flag‐tagged Hwa (Hwa‐Flag) and HA‐tagged ZNRF3 (ZNRF3‐HA) further confirmed the ZNRF3 and Hwa interaction. ZNRF3 was detected in an anti‐Flag immunoprecipitated HEK293T cell lysate (Fig 2C, lane 4 versus lane 3) and, conversely, Hwa was detected in an anti‐HA immunoprecipitated cell lysate (Fig 2D, lane 5 versus lane 4). ZNRF3 mutant lacking the RING domain (ZNRF3ΔRING) is an enzymatic activity dead form of ZNRF3 (Hao et al, 2012). Under the same experimental conditions, ZNRF3ΔRING also showed strong interaction with Hwa (Fig 2C, lane 6 versus lane 5; and D, lane 6 versus lane 4), indicating the RING domain of ZNRF3 is dispensable for this interaction. Moreover, indirect immunofluorescence analysis showed colocalization of Hwa‐Flag and ZNRF3‐HA/ZNRF3ΔRING‐HA in Hela cells (Fig 2E).

Figure 2. Hwa interacts with ZNRF3.

- Schematic illustration of Flag pull‐down assay. The empty vector (Flag‐control) and Hwa‐Flag were purified from HEK293T cells with anti‐Flag beads and incubated with oocytes homogenate; associated proteins were identified by mass spectrometry.

- Coomassie brilliant blue staining and MS analysis of Hwa‐associated proteins after immunoprecipitation (Flag pull‐down). Right (outlined text), thirteen matched peptide sequences that correspond to ZNRF3. Hwa‐MF, Myc‐Flag‐tagged Hwa.

- Co‐IP with HEK293T cells co‐transfected with plasmids encoding Hwa‐Flag and ZNRF3‐HA or ZNRF3ΔRING. Lysates immunoprecipitated with anti‐Flag were immunoblotted with HA and Flag antibodies. Blots are representative of three independent experiments.

- Co‐IP with HEK293T cells co‐transfected with plasmids encoding Hwa‐Flag and ZNRF3‐HA or ZNRF3ΔRING. Lysates immunoprecipitated with anti‐HA were immunoblotted with Flag and HA antibodies. Blots are representative of three independent experiments.

- Colocalization of Hwa‐Flag (red) and ZNRF3‐HA (green) or ZNRF3ΔRING‐HA (green) in Hela cells is indicated by yellow dots. Baf‐A1, 50 nM, 12 h. Magnification: 100×; scale bar: 10 µm.

- Schematic diagram of ZNRF3 truncations. ZNRF3FL, full‐length ZNRF3; ZNRF3ΔRING, ZNRF3 lacking the RING domain; ZNRF31–320, amino acids 1–320 of ZNRF3; ZNRF3320–606, amino acids 320–606 of ZNRF3; ZNRF3606–854, amino acids 606–854 of ZNRF3.

- Co‐IP of HEK293T cells transfected to express Hwa‐Flag and vector only or plasmids encoding ZNRF3 truncation mutants as indicated in (F). Lysates immunoprecipitated with anti‐HA were analyzed by immunoblotting with Flag and HA antibodies. Blots are representative of three independent experiments.

We constructed several ZNRF3 truncations to further characterize the region involved in the interaction with Hwa (Fig 2F). These truncations were co‐transfected with Haw‐Flag into HEK293T cells followed by HA co‐immunoprecipitation. Only the truncation ZNRF3320–606 showed interaction with Hwa (Fig 2G, lane 3 versus lanes 2, 4), indicating the amino acids 320‐606 region of ZNRF3 is essential for this interaction.

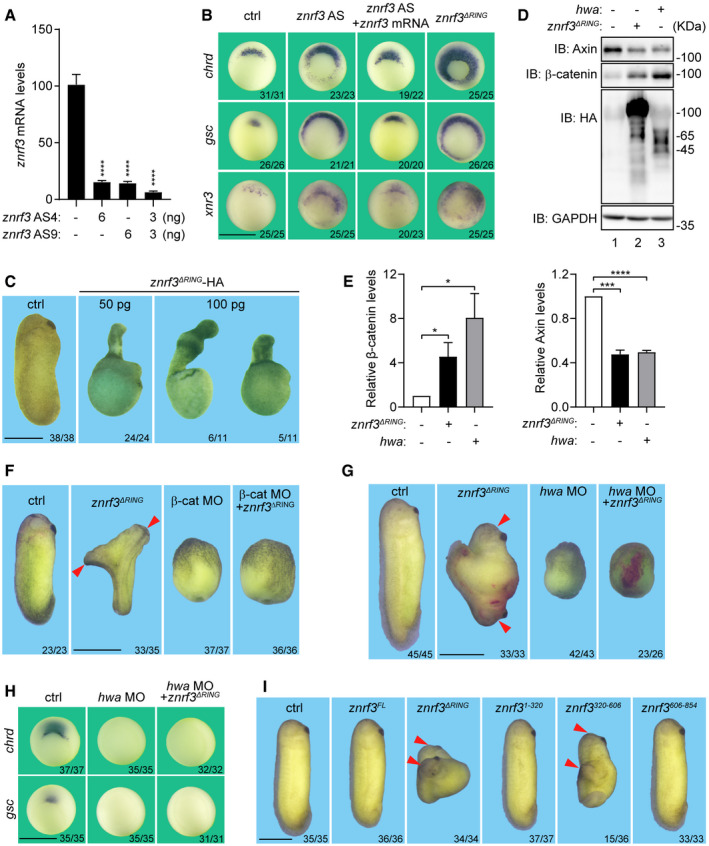

Maternal ZNRF3 is essential for the dorsal ventral axis formation in Xenopus laevis

The identification of ZNRF3 from the oocyte homogenates using Hwa as a bait is consistent with a previous finding from others that ZNRF3 is a maternal gene in Xenopus laevis (Chang et al, 2020). In contrast to the restricted localization of Hwa mRNA in oocytes and blastula stage embryos (Yan et al, 2018), ZNRF3 mRNA is ubiquitously expressed (Chang et al, 2020) (Fig EV1A). To determine the function of maternal ZNRF3 in Xenopus laevis, we carried out antisense oligo (ASO)‐mediated maternal mRNA depletion experiments (Hulstrand et al, 2010). Candidate antisense oligos (ASOs) were designed to specifically target the coding region of znrf3 mRNA. Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT–PCR) assay indicated that microinjection of selected znrf3 ASOs (AS4 and AS9) efficiently depleted znrf3 in Xenopus oocytes (Fig 3A). The embryos depleted of the maternal znrf3 were obtained through the host transfer technique and subjected to gene expression analyses. Whole‐mount in situ hybridization (WISH) showed that the expression ranges of the organizer makers gsc and chordin were expanded in ZNRF3‐depleted embryos as compared to those in uninjected control embryos (Fig 3B, column 2 versus column 1). Re‐injection of an ASO‐insensitive znrf3 mRNA into ZNRF3‐depleted embryos could efficiently restore the expression ranges of the examined marker genes (Fig 3B, column 3 versus column 2), indicating that the maternal ZNRF3 is specifically required for controlling the expression ranges of organizer genes. Of note, the maternal ZNRF3‐depleted embryos appeared normal during the cleavage and blastula stages but failed to pass gastrulation and eventually died. This precluded a thorough assessment of the post‐gastrula phenotypic effects of the maternal ZNRF3 depletion.

Figure EV1. ZNRF3ΔRING rescues defects caused by maternal lrp6 knockdown in Xenopus embryos.

- Whole‐mount in situ hybridization of znrf3 and hwa in embryos at blastula stage. Scale bars: 1 mm.

- Representative phenotypes of Xenopus laevis embryos at tailbud stage. 6 ng lrp6 antisense‐oligo (lrp6 AS) was injected into oocytes at stage VI, and embryos were obtained through host transfer technology. znrf3ΔRING mRNA (20 pg) was injected at one ventral blastomere of 4‐cell stage embryos. Scale bars: 1 mm.

- Whole‐mount in situ hybridization of organizer markers chrd and gsc in gastrula embryos (stage 10.5). Embryos were injected and obtained as descripted in B. Scale bars: 1 mm.

Figure 3. Maternal ZNRF3 is essential for the dorsal ventral axis formation in Xenopus .

- qRT–PCR analysis of the efficacies of znrf3 AS normalized to odc. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. n = 3 biological replicates; ****P < 0.0001 by unpaired t test.

- Whole‐mount in situ hybridization of Spemann organizer markers chrd, gsc, and xnr3 in gastrula embryos (stage 10.5). Oocytes were injected with AS or mRNAs as indicated, Dosage: znrf3 AS (3 ng AS4 + 3 ng AS9), znrf3 mRNA 100 pg, znrf3ΔRING mRNA 50 pg. Embryos were obtained through Host transfer technology. Scale bars: 1 mm.

- Representative phenotypes of tailbud stage Xenopus leavis embryos injected with ctrl or znrf3ΔRING mRNAs as indicated. mRNAs were injected in pre‐mature oocytes and embryos were obtained through Host transfer technology. Scale bars: 1 mm.

- Western blot analysis of Axin and β‐catenin in blastula stage (st7‐8) embryos injected with 500 pg znrf3ΔRING or 500 pg hwa at 1‐cell stage. Lysates were immunoblotted with Axin, β‐catenin, HA, and GAPDH. Blots are representative of three independent experiments.

- Relative levels of β‐catenin (left) and Axin (right) in (D) normalized to GAPDH. n = 3 independent experiments, mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.005, ****P < 0.0001 by unpaired t test.

- Representative phenotypes of Xenopus embryos at tailbud stage. Embryos were injected with ctrl (20 pg gfp mRNA), 20 pg znrf3ΔRing mRNA at one ventral blastomere of 4‐cell stage embryos, or 20 ng β‐catenin morpholino (β‐cat MO) at 1‐cell stage as indicated. Duplicated axes (red arrowhead). Scale bars: 1 mm.

- Representative phenotypes of Xenopus laevis embryos at tailbud stage. 20 ng hwa morpholino (hwa MO) was injected in oocytes at stage VI, embryos were obtained through Host transfer technology. znrf3ΔRING mRNA (20 pg) was injected at one ventral blastomere of 4‐cell stage embryos. β‐gal mRNA 200 pg was co‐injected with znrf3ΔRING mRNA as lineage tracer. Duplicated axes (red arrowhead). Scale bars: 1 mm.

- Whole‐mount in situ hybridization of Spemann organizer markers chrd and gsc in gastrula embryos (stage 10.5). Embryos were injected and obtained as descripted in (G). Scale bars: 1 mm.

- Representative phenotypes of tailbud stage Xenopus leavis embryos injected with 500 pg mRNAs of ctrl (gfp mRNA), znrf3FL , and znrf3 truncations as indicated at 4‐cell stage. Duplicated axes (red arrowhead). znrf3FL , full‐length znrf3; znrf3ΔRING , znrf3 lacking the RING domain; znrf3 1–320, amino acids 1–320 of znrf3; znrf3 320‐606, amino acids 320–606 of znrf3; znrf3 606–854, amino acids 606–854 of znrf3. Scale bars: 1 mm.

To facilitate assessment of ZNRF3 function in early Xenopus development, we took advantage of ZNRF3ΔRING, a well‐characterized dominant negative form of ZNRF3 (Hao et al, 2012). We microinjected the synthetic znrf3ΔRING RNA into oocytes to interfere the functions of endogenous ZNRF3. Overexpression of ZNRF3ΔRING expanded the expansion ranges of gsc and chordin, recapitulating the effect of maternal ZNRF3 depletion (Fig 3B, column 4 versus column 2) and further affirming that ZNRF3 is a negative regulator of the organizer formation and dorsal development. Developmental arrest during gastrulation was also observed from most ZNRF3ΔRING‐expressing embryos. However, a small fraction (50 pg group: 24%, 24/102; 100 pg group: 12%, 11/91) survived to tail bud stages, allowing for phenotype recording. Embryos receiving the low‐dose injection of znrf3ΔRING showed a dorsalized phenotype with radial proboscis and outward elongated notochord (Fig 3C, column 2 versus column 1); while those with the high‐dose injection of znrf3ΔRING exhibited hyperdorsalization with concomitant defects in convergent extension movements (Fig 3C, column 3 versus column 1). Based on these loss‐of‐function analyses, we conclude that the maternal ZNRF3 is necessary for the normal body pattern formation by restraining the maternal dorsalizing activity.

To determine whether β‐catenin is involved in dorsalization by ectopic ZNRF3ΔRING, levels of β‐catenin were examined through immunoblotting. Overexpression of ZNRF3ΔRING, resembling overexpression of Hwa, increased the expression level of β‐catenin and concurrently decreased the expression level of axin (Fig 3D and E). These observations predict that β‐catenin would be required for the dorsalizing activity of ZNRF3ΔRING. To test this prediction, we employed the secondary axis induction assay. Injection of znrf3ΔRING mRNA into four‐cell stage wild‐type embryos induced a secondary (2nd) axis (Fig 3F, column 2 versus column 1), but failed to do so in embryos received β‐catenin morpholino (MO) (Fig 3F, columns 3, 4 versus column 1), indicating that β‐catenin is absolutely required for ZNRF3ΔRING to elicit the dorsal axis formation.

Hwa stabilizes β‐catenin through potentiating Axin degradation (Yan et al, 2018). Consistently, overexpression of ZNRF3ΔRING in Xenopus embryos also resulted in a decrease of Axin level as Hwa did (Fig 3D, lanes 2, 3 versus lane 1; and E, right). We then asked whether Hwa is required for ZNRF3 function. To answer this question, we evaluated the body axis‐inducing activity of ZNRF3ΔRING when the maternal Hwa was depleted. Injection of Hwa MO into Xenopus oocytes caused completely ventralized embryos at the tailbud stage (Fig 3G, column 3 versus column 1) and eliminated the SMO markers chrd and gsc at the mid‐gastrula stage (Fig 3H, column 2 versus column 1). In the absence of endogenous Hwa, injection of znrf3ΔRING mRNA into one blastomere at four‐cell stage failed to induce the body axis (Fig 3G, column 4 versus column 2), or to expand the organizer markers chrd and gsc (Fig 3H, column 3 versus column 2). The functional importance of ZNRF3/Hwa interaction was further examined through the secondary axis induction assay. The mRNAs encoding full‐length ZNRF3FL and its truncations were separately injected into one ventral blastomere of the four‐cell stage Xenopus embryos. We found that only ZNRF3320‐606 was able to induce a secondary axis (Fig 3I, columns 3, 5 versus column 1), suggesting ZNRF3320‐606 might function as a dominant negative mutant with a lesser potency in comparison to ZNRF3ΔRING. These observations together support the notion that the dorsalizing activity of ZNRF3ΔRING depends on the presence of Hwa. In other words, ZNRF3 is a negative regulator of Hwa during the dorsal body axis formation in Xenopus laevis.

ZNRF3 has also been shown to negatively regulate the Wnt receptors Frizzled and LRP5/6 (Hao et al, 2012, 2016; Koo et al, 2012). Previous studies have implicated the maternal Lrp6 into the dorsal development depending on the presence of β‐catenin in Xenopus (Zeng et al, 2005; Kofron et al, 2007), pointing to a possibility that the observed dorsalizing effects from ZNRF3 depletion could also be explained by an excess Lrp6 signaling in addition to an excess Hwa. To test this possibility, we obtained embryos depleted of the maternal Lrp6 using a previously characterized antisense oligodeoxynucleotide (Kofron et al, 2007; Yan et al, 2018). Depletion of the maternal Lrp6 caused ventralization (Fig EV1B) and diminished the expression of organizer genes chrd and gsc (Fig EV1C). Both aspects of defects from Lrp6 depletion could be readily rescued by the ectopic ZNRF3ΔRING (Fig EV1B and C), suggesting that Lrp6 is dispensable for the ZNRF3 deficiency‐caused dorsalization.

Taken together, our observations highlight that ZNRF3 is an essential regulator of Hwa in addition to other component(s) of the maternal dorsal determination pathway.

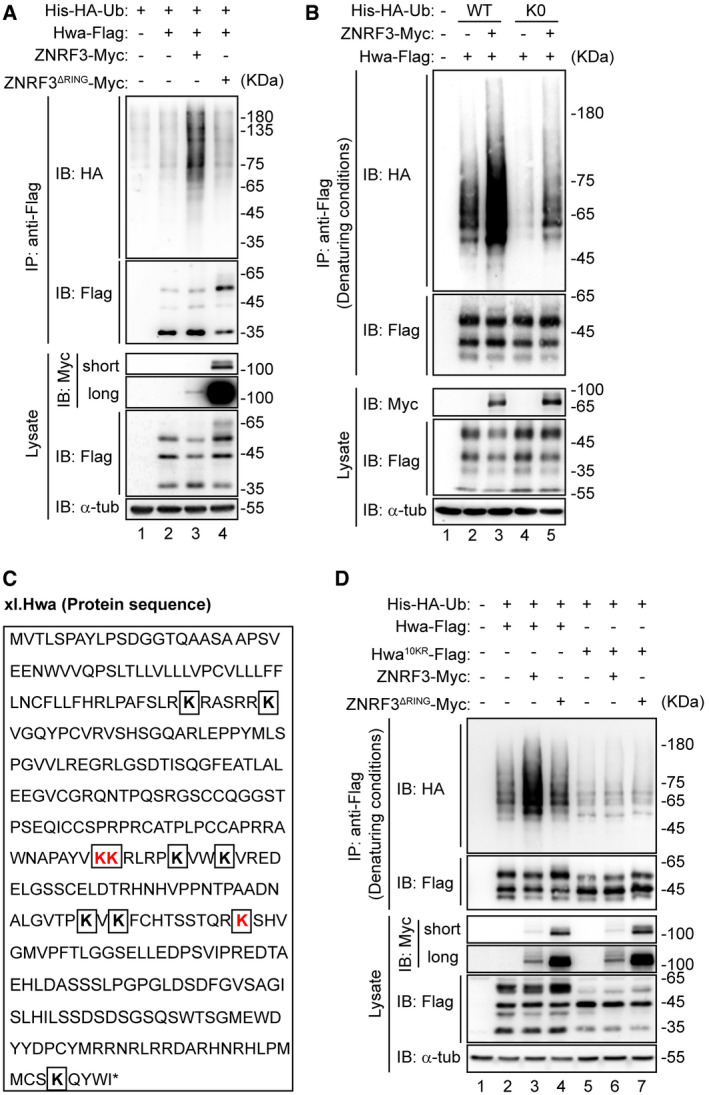

ZNRF3 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase for Hwa

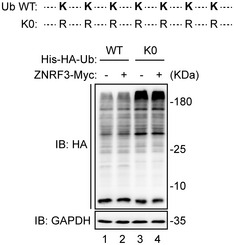

Our observation that ZNRF3 interacts with Hwa via its amino acids 320‐606 region (Fig 2G) is consistent with the notion that ZNRF3 generally binds to substrates with its intracellular domain (Jiang et al, 2015). We went on to examine whether ZNRF3 ubiquitylates Hwa. In the presence of His‐HA‐Ub, Hwa‐Flag was co‐transfected with ZNRF3 or ZNRF3ΔRING into HEK293T cells followed by ubiquitination assays. As previously reported, ZNRF3ΔRING is expressed much more than the WT (Hao et al, 2012). We found that in the absence of ZNRF3, ubiquitinated Hwa was in very low abundance (Fig 4A, lane 2). Co‐expression of ZNRF3 resulted in a higher level of ubiquitinated Hwa (Fig 4A, lane 3 versus lane 2), whereas ZNRF3ΔRING was unable to increase the levels of ubiquitinated Hwa (Fig 4A, lane 4 versus lane 3). Interestingly, when the ubiquitin mutant Ub K0 in which all 7 lysine residues were mutated into arginines (Fig EV2) was co‐transfected, ZNRF3 could still promote ubiquitination of Hwa (Fig 4B, lane 5 versus lane 4), suggesting that ZNRF3 is able to incorporate mono‐ubiquitin moiety on to Hwa.

Figure 4. Hwa undergoes multi‐monoubiquitination.

- Hwa is ubiquitinated by ZNRF3, but not ZNRF3ΔRING. HEK293T cells were co‐transfected with Hwa‐Flag and ZNRF3 or ZNRF3ΔRING. The lysates were immunoblotted with Myc, Flag, and α‐tubulin antibodies. Lysates immunoprecipitated with anti‐Flag were immunoblotted with HA and Flag antibodies. Blots are representative of three independent experiments.

- Hwa ubiquitination was analyzed under denaturing conditions. HEK293T cells co‐transfected with wild‐type His‐HA‐Ubiquitin (His‐HA‐Ub WT) or lysine‐less mutant (K0), Hwa‐Flag, and ZNRF3‐Myc. The lysates were immunoblotted with Myc, Flag, and α‐tub (α‐tubulin). Lysates immunoprecipitated with anti‐Flag were immunoblotted with HA and Flag antibodies. K0, all lysine sites on ubiquitin were mutated. Blots are representative of 3 independent experiments.

- Lysine sites (K) in Hwa protein sequence. Three ubiquitination lysine sites (K178, K179, and K234) identified by MS were indicated in red. Other seven lysine sites were indicated in bold.

- Screen of ZNRF3‐mediated Hwa ubiquitination sites under denaturing conditions. HEK293T cells were co‐transfected with His‐HA‐Ub, Hwa‐Flag or Hwa10KR‐Flag, and ZNRF3 or ZNRF3ΔRING. The lysate was immunoblotted with Myc, Flag, and α‐tub (α‐tubulin). Lysates immunoprecipitated with anti‐Flag were immunoblotted with HA and Flag antibodies. Hwa10KR‐Flag mutant, all lysine sites in Hwa sequence were replaced with arginine. Denaturing conditions: before immunoprecipitation, lysates were denatured by adding SDS to a final concentration at 1% and boiling at 95°C for 15 min. Blots are representative of three independent experiments.

Figure EV2. Schematic illustration and expression of Ub WT and K0.

Schematic illustration of Ub single‐lysine mutants (Up). K0, all lysine (K) residues of Ub were mutated to arginine (R). The expression of His‐HA‐Ub WT and K0 in HEK293T cells (Down). Lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis with HA antibody.

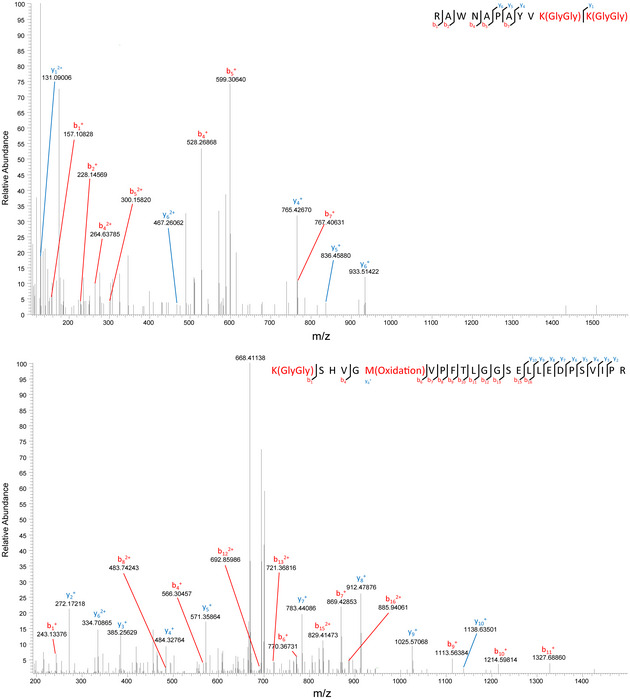

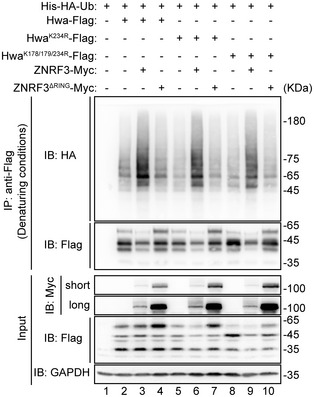

The observed complex smearing banding patterns of Hwa in the ubiquitination assays prompted us to identify the essential lysine site(s) on Hwa ubiquitinated by ZNRF3. Ubiquitination assay followed by MS identified three potential ubiquitinated sites K178/179 and K234 (Fig EV3 and Fig 4C marked in red). To confirm results from the MS analyses, we mutated K178/179 and K234 to arginine (HwaK178/179/234R and HwaK234R) for additional ubiquitination assays. We found that these mutants remained to be ubiquitinated with much reduced efficiency though as compared to the wild‐type Hwa by ZNRF3 (Fig EV4), implying that Hwa may be ubiquitinated by ZNRF3 through other lysines in addition to those detected by MS. To test this, we generated a Hwa10KR mutant in which all lysine residues were substituted with arginine. This mutant completely prevented ZNRF3‐mediated Hwa ubiquitination (Fig 4D, lane 6 versus lane 5), indicating all lysine sites on Hwa could potentially be ubiquitylated by ZNRF3.

Figure EV3. Identification of ubiquitination sites in Hwa.

MS analysis of the ubiquitination of Hwa K178/179 (top) and K234 (bottom) in a mixture of proteins purified from HEK293T cells ectopically expressing Hwa‐3×Flag with or without ZNRF3‐HA. Proteins were purified with anti‐Flag beads; bound proteins were eluted and subjected to SDS–PAGE.

Figure EV4. HwaK243R and HwaK178/179/234R mutants could not completely prevent ZNRF3‐mediated ubiquitination.

Ubiquitination analysis of Hwa and its mutants under denaturing conditions. HEK293T cells were co‐transfected with His‐HA‐Ub, Hwa‐Flag or Hwa mutants, and ZNRF3 or ZNRF3ΔRING. The lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies, respectively, against Myc, Flag, and/or GAPDH. Lysates immunoprecipitated with anti‐Flag were immunoblotted with HA and Flag antibodies. HwaK234R‐Flag mutant, lysine site (K234) was substituted with arginine (R); HwaK178/179/234R‐Flag mutant, lysine sites (K178, K179, K234) were all replaced with arginine (R). Denaturing conditions: before immunoprecipitation, lysates were denatured by adding SDS to a final concentration at 1% and boiling at 95°C for 15 min. Blots are representative of three independent experiments.

ZNRF3‐mediated ubiquitination affects the lysosomal degradation of Hwa

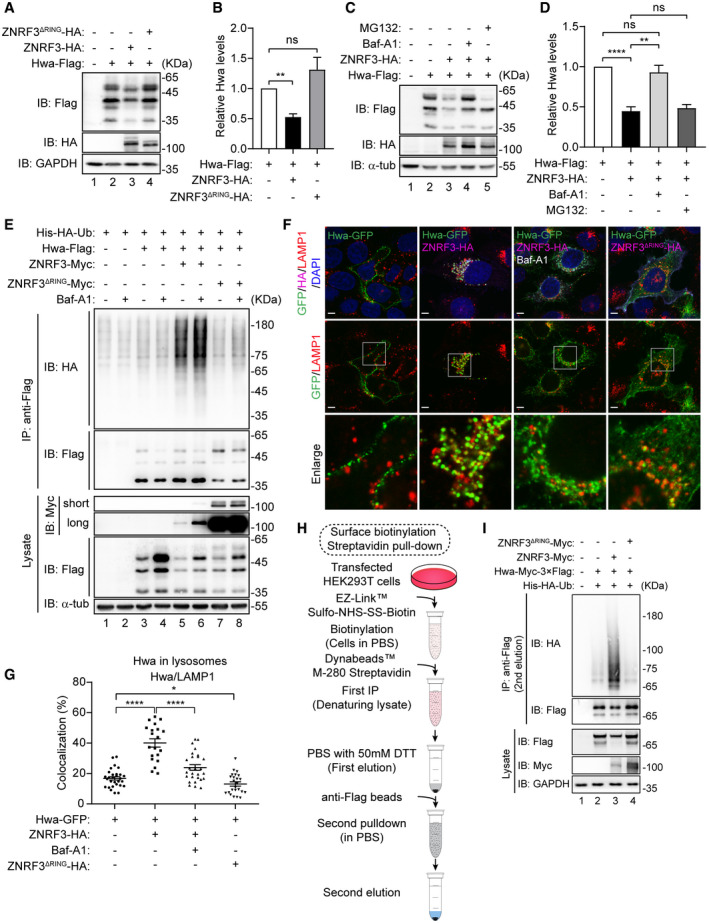

To interrogate how ZNRF3 regulates Hwa degradation through ubiquitination, we transfected Hwa‐Flag along with ZNRF3 (5 μg) or ZNRF3ΔRING (2.5 µg) into HEK293T cells and the expression levels of Hwa were assessed by immunoblotting. The result showed ZNRF3 but not ZNRF3ΔRING markedly reduced Hwa protein levels (Fig 5A, lanes 3, 4 versus lane 2; and B), indicating the E3 ligase activity is required for ZNRF3 to promote Hwa degradation. Application of Baf‐A1 but not MG132 efficiently blocked ZNRF3‐indcued degradation of Hwa (Fig 5C and D), supporting the notion that ZNRF3 promotes Hwa degradation through the lysosomal pathway (Fig 1). This was further corroborated by the observation that Baf‐A1 treatment additionally enhanced the Hwa ubiquitination by ZNRF3 (Fig 5E).

Figure 5. ZNRF3 promotes ubiquitin‐mediated lysosome trafficking and degradation of Hwa.

- Western blot analysis of Hwa in HEK293T cells co‐transfected with Hwa‐Flag, and ZNRF3‐HA (5 µg) or ZNRF3ΔRING (2.5 µg). Lysate was immunoblotted with Flag, HA, and GAPDH antibodies. Blots are representative of three independent experiments.

- Densitometry analysis of Hwa bands from the Western blot in (A) for corresponding lanes normalized to GAPDH. n = 3 independent experiments, mean ± SEM, ns P > 0.05, **P < 0.01 by unpaired t test.

- Western blot analysis of Hwa in HEK293T cells co‐transfected with Hwa‐Flag and ZNRF3‐HA. Cells were treated with or without Baf‐A1 (50 nM) or MG132 (20 µM) for about 12 h. Lysates were immunoblotted with Flag, HA, and α‐tub (α‐tubulin) antibodies. Blots are representative of 3 independent experiments.

- Densitometry analysis of Hwa bands from the Western blot in (C) for corresponding lanes normalized to α‐tubulin. n = 3 independent experiments, mean ± SEM, ns P > 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001 by unpaired t test.

- Ubiquitination analysis of Hwa with or without Baf‐A1 (50 nM, 12 h). HEK293T cells were co‐transfected with Hwa‐Flag, and ZNRF3‐HA or ZNRF3ΔRING‐HA. Lysate was immunoblotted with Myc, Flag, and α‐tub (α‐tubulin) antibodies. Lysates immunoprecipitated with anti‐Flag were immunoblotted with HA and Flag antibodies. Blots are representative of three independent experiments.

- Colocalization by immunofluorescence of Hwa (green signals) with lysosome (LAMP1, red signals) in Hela cells. Cells were co‐transfected with Hwa‐Flag, and ZNRF3‐HA or ZNRF3ΔRING‐HA. Magnification, 100×; scale bars: 10 µm.

- Colocalization analysis of Hwa‐Flag and lysosome by ImageJ software. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; n > 20 cells from each group. *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001 by unpaired t test.

- Flow chart of surface biotinylation and streptavidin pull‐down.

- Surface biotinylation and streptavidin pull‐down of Hwa‐Myc‐Flag. HEK293T cells were co‐transfected with Hwa‐MF (Hwa‐Myc‐Flag), and ZNRF3‐Myc or ZNRF3ΔRING‐Myc. Lysate was immunoblotted with Myc, Flag, and GAPDH antibodies. Lysates immunoprecipitated with anti‐Flag (2nd elution) were immunoblotted with Flag and HA antibodies.

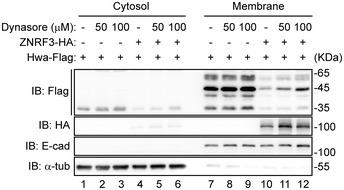

To provide evidence that ZNRF3 could interact with Hwa in the lysosomal pathway, we performed the indirect immunofluorescence analyses. Hwa‐GFP together with ZNRF3‐HA or ZNRF3ΔRING‐HA were transfected into Hela cells followed by immunofluorescent analysis of the lysosome maker LAMP1 (red) and Hwa‐GFP (green) (Fig 5F). In cells receiving Hwa alone, Hwa was mainly detected on the plasma membrane and barely overlapped with LAMP1 signals (Fig 5F, column 1; and Fig 5G for quantitative comparison). In the cells positive for both ZNRF3 (mauve) and Hwa (green), the numbers of puncta representing overlap of Hwa and LAPM1 was apparently increased (Fig 5F, column 2 versus column 1; and Fig 5G), indicating ZNRF3 enhanced lysosomal recruitment of Hwa. Application of Baf‐A1 reduced the incidence of LAMP1/Hwa colocalization regardless of the presence of ZNRF3 (Fig 5F, column 3 versus column 2; and Fig 5G). Interestingly, ZNRF3ΔRING failed to increase the colocalization of Hwa with LAMP1 (Fig 5F, column 4 versus column 2; and Fig 5G). Furthermore, we found that application of the cell‐permeable dynamin GTPase inhibitor dynasore (Macia et al, 2006) inhibited ZNRF3‐mediated degradation of Hwa (Fig EV5, lanes 11, 12 versus lane 10). Taken together, these results suggest that ZNRF3 facilitates the trafficking and degradation of Hwa through the endosomal/lysosomal pathways.

Figure EV5. Dynasore inhibits ZNRF3‐mediated Hwa degradation.

Immunoblot analysis of Hwa in cytosolic and membrane fractions of HEK293T cells treated with or without dynasore as indicated for 12 h. Cells were co‐transfected with Hwa‐Flag, and control‐vector or ZNRF3‐HA. Lysates were immunoblotted with Flag, HA, E‐cad (E‐cadherin), and α‐tub (α‐tubulin). Blots are representative of three independent experiments.

To additionally demonstrate that ZNRF3 clears Hwa expression from the plasma membrane, we performed surface biotinylation and Streptavidin pull‐down assay (Fig 5H). Cells transfected with the desired constructs were surface‐labeled with biotin 24 h after transfection. Cell homogenates were immunoprecipitated with Streptavidin‐beads to enrich plasma membrane proteins. PBS with 50 mM DTT was used to elute the enriched proteins, which were further precipitated with anti‐Flag beads to enrich plasma membrane tethered Hwa‐MF. After the second‐step co‐IP with anti‐Flag beads, Hwa‐MF was detected and reduced by ZNRF3 but not ZNRF3ΔRING, in contrast, ubiquitination levels of Hwa‐MF were increased by ZNRF3 but not ZNRF3ΔRING (Fig 5I, lane 3 versus lane 2, 2nd elution). These data collectively suggest that Hwa is ubiquitinated by ZNRF3 at plasma membrane.

ZNRF3 prevents the ectopic organizer inducing activity of Hwa

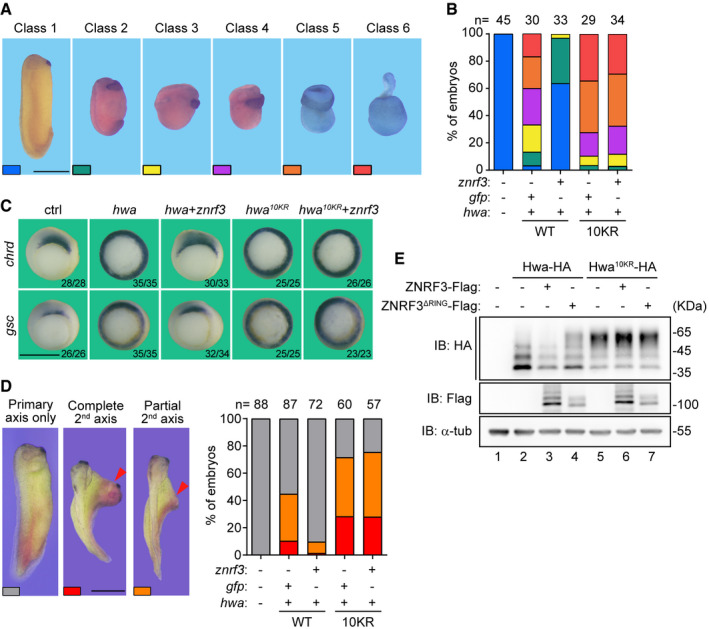

To further elaborate on the functional significance of ubiquitination of Hwa by ZNRF3, we compared the dorsalizing activities of Hwa WT and Hwa10KR when coinjected with ZNRF3. Overexpression of Hwa alone in oocytes resulted in severe dorsalization phenotype during later stages of development (Fig 6A and B). The severity of dorsalization caused by Hwa WT overexpression could be drastically relieved by coinjection of ZNRF3 (Fig 6A and B). Coinjection of ZNRF3 could also restrict the expansion of organizer markers gsc and chrd caused by Hwa WT overexpression (Fig 6C). By contrast, Hwa10KR seemed to be resistant to the coinjected ZNRF3 in causing severe dosalization (Fig 6A and B) and/or expanding the expression domains of organizer genes (Fig 6C), confirming that Hwa is negatively controlled by ZNRF3 through ubiquitination.

Figure 6. ZNRF3 prevents the secondary axis‐inducing activity of Hwa.

- Morphology of classified embryos at tailbud stage. Scale bars: 1 mm.

- Ratios of embryos in different classes. Oocytes were injected with 5 pg hwa mRNA or hwa10KR mRNA and 100 pg znrf3 mRNA as indicated. Embryos were obtained through host transfer technology.

- Whole‐mount in situ hybridization of Spemann organizer markers chrd and gsc in gastrula embryos. Embryos were obtained as descripted in (B). Scale bars: 1 mm.

- Induction of the secondary (2nd) axis by hwa or znrf3 as indicated in Xenopus embryos. One ventral blastomere of 4‐cell stage embryos was injected with hwa mRNA (5 pg) or hwa10KR mRNA (5 pg) and znrf3 mRNA (100 pg). Up: Classes of embryos. Down: Ratio of classified embryos. The 2nd axis (red arrowhead). Scale bars: 1 mm.

- Western blot analysis of Hwa or Hwa10KR in embryos at blastula stage. 1‐cell stage embryos were co‐injected with hwa (100 pg) or hwa10KR (100 pg) and znrf3 (1 ng) or znrf3ΔRING (100 pg) as indicated. Lysates were immunoblotted with HA, Flag, and α‐tub (α‐tubulin).

The dorsalizing activities of Hwa and Hwa10KR were further assessed through the secondary axis induction assay. Injection of hwa mRNA into one ventral blastomere of the four‐cell stage Xenopus embryos induced a secondary (2nd) axis (Fig 6D). Coinjection of znrf3 mRNA largely reduced the proportion and completeness of the secondary axis induced by ectopic Hwa (Fig 6D). Under the similar experimental design, Hwa10KR appeared to be more potent in the induction of the secondary axis as compared to wild‐type Hwa (Fig 6D). Co‐expression of ZNRF3 seemed unable to inhibit the activity of Hwa10KR (Fig 6D). Consistently, immunoblotting analysis indicated that coinjection of ZNRF3 could readily inhibit the expression of Hwa WT but not that of Hwa10KR (Fig 6E), further highlighting the functional relevance of ubiquitination and consequently degradation of Hwa by ZNRF3 in the organizer induction and the dorsal axis formation.

Discussion

In this report, we provide evidence that the membrane associated E3 ubiquitin ligase ZNRF3 is an essential regulator of the maternal dorsal determinant Hwa in Xenopus laevis. ZNRF3 promotes rapid lysosomal degradation of Hwa. ZNRF3 deficiency results in exaggerated organizer induction depending on the presence of Hwa. Overexpression of ZNRF3 abolishes the axis duplication activity of ectopic Hwa. ZNRF3‐mediated Hwa degradation is therefore essential for the proper Spemann‐Mangold organizer (SMO) formation.

The Xenopus oocyte is radially symmetrical along its apparent animal–vegetal axis. Fertilization breaks this symmetry, causing a readily observable effect that the SMO and the dorsal axis predictably arise from the side of embryo opposite to the sperm entry point (Ubbels et al, 1983; Vincent et al, 1986; Vincent & Gerhart, 1987; Kageura, 1997; Weaver et al, 2003). Accompanying this symmetry breaking process, the Hwa encoding mRNA is asymmetrically distributed across the presumptive dorsal ventral axis (Yan et al, 2018). We found that oocytes expressing excessive Hwa exhibit expanded SMO, and ultimately result in a dorsalization phenotype. However, overexpression of ZNRF3 sufficiently blocks the dorsalizing activity of Hwa. In addition, Hwa is required for the SMO expansion caused by maternal ZNRF3 depletion and ectopic ZNRF3 dominant negative mutant. Biochemically, ZNRF3 negatively regulates Hwa‐stimulated stabilization of β‐catenin to prevent exaggerated SMO induction. These findings collectively support the hypothesis that ubiquitously expressed ZNRF3 can be considered a necessary component of the radial symmetricity of the unfertilized egg, rendering the fertilization triggered symmetry breaking a robust process.

ZNRF3 and its close relative RNF43 have been identified as antagonist for Wnt and BMP signaling in various physiological and pathological processes through promoting degradation of Wnt receptor(s) and/or BMPR1A (Hao et al, 2012, 2016; Koo et al, 2012; Harris et al, 2018; Lee et al, 2020). Our results showed that depletion of maternal ZNRF3 results in an extended SMO, raising the possibility that this effect may be related to the regulation of Wnt and BMP signaling. However, our data showed that overexpression of ZNRF3 dominant negative mutant leads to a similar defect as caused by ZNRF3 depletion. Moreover, depletion of Hwa is sufficient, and by contrast depletion of Lrp6 is insufficient, to abrogate the dorsal axis‐inducing activity of ZNRF3 dominant negative mutant. Previous studies from others have also demonstrated that the dorsal SMO expressed PTPRK facilitates ZNRF3 internalization to promote the degradation of Wnt receptors (Chang et al, 2020). RSPO2, which is distributed in the ventral side of blastopore, has been reported to inhibit ZNRF3‐mediated degradation of Wnt receptors (Hao et al, 2012). These studies together suggest that the activity of ZNRF3 is critically regulated in the formation of SMO during early gastrulation. Without ruling out the importance of ZNRF3 in controlling other important signaling pathways, we propose that the maternal dorsal determinant Hwa is a principal target of ZNRF3 during the SMO induction and dorsal body axis formation.

Overexpression of ZNRF3 could abolish the dorsalization activity of ectopic Hwa, but exhibited limited effects on the endogenous dorsal axis formation (Fig 6A). This is understandable, as the fertilization triggered cortical rotation is a complex process involving microtubule remodeling and kinesin‐mediated cargo transport (Gerhart et al, 1984; Moon & Kimelman, 1998; Cha & Gard, 1999; Cuykendall & Houston, 2009; Mei et al, 2013; Colozza & De Robertis, 2014). Interestingly, the interacting region of ZNRF3 (320–606 aa) covers the DIR domain, which has been unveiled by several studies as a key region modulating ZNRF3/RNF43 activity, including via interaction with DVL (Jiang et al, 2015; Spit et al, 2020; Tsukiyama et al, 2020; Giebel et al, 2021). The role of DVL in the dorsal determination process remains elusive and perplexing (Shi, 2020). Intriguingly, DVL has been shown to facilitate the ZNRF3‐mediated turnover of FZD (Jiang et al, 2015). However, our preliminary results indicate that overexpressed Dvl2 exhibited no obvious effects on the ZNRF3 promoted degradation of Hwa. Furthermore, the DIR region of RNF43, a close relative of ZNRF3, has been shown to interact with CK1 and Axin (Spit et al, 2020; Tsukiyama et al, 2020), both of which are critical components of the destruction complex of β‐catenin. Last but not least, the maternally supplied Wnt11b together with its cognate receptor Lrp6 has been shown to keep Axin level low in oocytes during the hormone stimulated maturation (Kofron et al, 2007). How would Hwa fit in this process? It would be interesting to consider the possibility that ZNRF3‐Hwa‐Axin signaling axis may be subjected to regulation by CK1 or other components of the Wnt signaling pathway. Moreover, ectopically expressed Hwa consistently appeared with complex banding patterns in the SDS–PAGE, raising the possibility that these bands might be Hwa with different modifications, such as glycosylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, or partial degradation. Further investigations are surely needed to better understand the modifications of Hwa and the relevant functions in embryo development.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid, Morpholino, antisense oligodeoxynucleotides, and mRNA synthesis

Full‐length coding sequence of Hwa (XM_698288.8) or ZNRF3.L (XM_018263896.1) was amplified, linearized using restriction enzymes EcoRI/XhoI (NEB, R3101L and R0146S), and cloned into the pcs107 vector with desired tags using M5 SuperFast Seamless Cloning mix (Mei5bio, MF017). Plasmids used for further experiments were extracted and purified using M5 Plasmid Miniprep plus Kit (Mei5bio, MF031‐plus‐01). Sequences of znrf3 antisense oligodeoxynucleotides are:

znrf3‐AS4: 5’‐T*T*C*ATATAAACCACA*G*G*C‐3’;

znrf3‐AS9: 5’‐A*C*C*TCCCTCCCCTCC*A*C*T‐3’,

(* indicates thioate substitution of phosphorus in the three phosphorodiester bonds at either end of the ODN, targeting both znrf3.L and znrf3.S homeolog). Morpholino oligos were designed and synthesized by GeneTools. Sequences of MO oligos are:

hwa MO: 5’‐CACGGCTATTTGGCAATCAGGAGAC‐3’;

β‐catenin MO: 5’‐TTCAACCGTTTCCAAAGAACCAGG‐3’ (Heasman et al, 2000). Capped mRNAs were synthesized with the mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion, AM1340) and injected into the oocytes or embryos at the desired stage as elucidated in the main text.

Host transfer technique

Xenopus embryos maternal depletion or overexpression was obtained through host transfer technique as previously described (Hulstrand et al, 2010). Briefly, meiosis I (G2/M)‐arrested oocytes were isolated through manual defolliculation using watchmaker’s forceps from surgically acquired ovary and cultured in oocyte culture medium (OCM, glutamine plus 60% L15 supplemented with 4% BSA supplemented with 1% penicillin and streptomycin). Isolated oocytes injected with antisense oligos or mRNA were cultured for 24–48 h and then matured with 2 mM progesterone for 12 h at 18°C. Mature oocytes were labeled with vital dyes (neutral red, Bismarck brown, Nile blue) and then transferred into the body cavity of an egg‐laying female. The female lay jellied colorful eggs. Eggs were then fertilized with sperm suspension. Fertilized eggs were dejellied using 2% cysteine in 0.1 × MMR (Marc’s Modified Ringers (Ubbels et al, 1983), containing 0.1 M NaCl, 2.0 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 2 mM CaCl2, 5 mM HEPES pH 7.8, 0.1 mM EDTA) followed by thorough wash with 0.1 × MMR. For microinjection after fertilization, eggs were cultured in 0.5 × MMR plus 2% Ficoll400. Microinjected embryos were transferred into fresh 0.3 × MMR and cultured to the desired stages.

Whole‐mount in situ hybridization (WISH) and Quantitative RT–PCR

In situ probe synthesis using T7 polymerase (Promega, P2075) incorporation of DIG‐UTP (Roche, 11209256910). Whole‐mount in situ hybridization was processed through standard procedures as previously described (Zhu et al, 2015). Quantitative RT–PCR was conducted with Taq Pro Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme, Q712‐02). The sequences of primers for qPCR used in this study are:

odc forward: 5′‐GCCATTGTGAAGACTCTCTCCATTC‐3′;

odc reverse: 5′‐TTCGGGTGATTCCTTGCCAC‐3′.

znrf3 forward: 5′‐GGATGGGTTGGAGTAGTAAAG‐3′;

znrf3 reverse: 5′‐CCCTGATTCAGCTGTTCAAC‐3′.

Cell culture, antibodies, and drugs

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells and Hela Cells were maintained in DMEM (Macgene, CM10013) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (PAN, P30‐3302) and 1 × penicillin‐streptomycin solution (Leagene, CA0075) in a 37°C incubator with 5% (v/v) CO2. Transfection with plasmids was performed using polyethylenimine (Polysciences, 23966) or Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, L3000015) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

The following antibodies and drugs were used in this study: anti‐HA (Santa Cruz, sc‐53516; MBL, 561, M180‐3S), anti‐Flag (Sigma, F3165; MBL, PM020), anti‐Myc (Santa Cruz, sc‐40; MBL, 562), anti‐E‐cadherin (BD Biosciences, 610182), anti‐LAMP1 (Cell Signaling Technology, 15665T), anti‐GAPDH (ZSGB‐Bio, TA‐08), anti‐α‐tubulin (Santa Cruz, sc‐5286), Anti‐Flag‐tag mAb‐Magnetic Agarose (MBL, M185‐10), Anti‐HA‐tag mAb‐Magnetic Agarose (Bimake, B26201; MBL, M180‐10), NH4Cl (Sigma‐Aldrich, 09718). Flag peptides (B23111), Bafilomycin A1 (S1413), Dynasore (S8047), and MG132 (S2619) were purchased from Selleck. Protease inhibitor cocktail (LABLEAD, C0101), Phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Bimake, B15002).

Immunoblotting and Immunoprecipitation

For immunoblotting analysis, transfected HEK293T cells were lysed in TNE lysis buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP40, 1 × protease inhibitor cocktail, 1 × phosphatase inhibitor cocktail). Xenopus embryos were lysed with RIPA lysis buffer (25 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 × protease inhibitor cocktail, 1 × phosphatase inhibitor cocktail). Supernatants were collected after centrifugation at 13,680 g 4°C 15 min and then subjected to Western blot directly.

For immunoprecipitation analysis, cell lysates were incubated with anti‐Flag‐tag mAb‐magnetic agarose (Flag beads) or anti‐HA‐tag mAb‐magnetic agarose (HA beads) at 4°C for ≥ 5 h or overnight. After washing with lysis buffer three times, protein‐beads complexes were eluted using 1 mg/ml Flag peptides or by boiling with 1 × SDS–PAGE loading buffer, and then subjected to immunoblotting. Proteins were detected by appropriate antibodies.

Flag pull‐down assay

HEK293T cells were transfected with Flag‐vector or Hwa‐3×Flag and harvested at 24 h after transfection. Cells were lysed in TNE lysis buffer and then subjected to affinity purification with Flag beads. After washing with TNE lysis buffer for five times, beads were further incubated with homogenate extracting from Xenopus embryos at one‐cell stage. Protein‐bead complexes were washed with TNE lysis buffer for three times followed by Flag peptide (1 mg/ml) elution. Proteins were loaded onto NuPAGE 10% Bis‐Tris gels (Life technologies, NP0316BOX) and visualized with Coomassie blue fast staining solution (Biodragan, BF06152). The potential interacting proteins in specific bands were analyzed with mass spectrum analysis (Center of Biomedical Analysis, Tsinghua University).

Ubiquitination assays

To perform the ubiquitination assays in cells, HEK293T cells were transfected with Hwa‐Flag, HA‐his‐Ub, ZNRF3, or ZNRF3ΔRING for 24 h. Cells were lysed with TNE lysis buffer and the supernatant was collected after centrifuging at 12,000× rpm 4°C for 15 min. Then, 10% supernatant was subjected to immunoblotting analysis. For ubiquitination assay under normal condition, the rest of supernatant was directly incubated with Flag beads followed by immunoprecipitation. For ubiquitination assay under denaturing condition, supernatant was denatured by adding SDS to a final concentration at 1% and boiling at 95°C for 15 min, then incubated with Flag beads followed by immunoprecipitation. The binding components were eluted using 1 mg/ml Flag peptide and were analyzed by immunoblotting.

Immunofluorescence

Hela cells were cultured on glass slides about 24 h prior to the experimental procedure. Transfected cells were rinsed thrice with 1 × PBS and fixed in cold acetone for 15 min, followed by permeabilization in 1 × PBS containing 0.5% Triton X‐100 (Promega, H5142) at room temperature (RT) for 20 min, then blocking with 1 × PBS containing 1% BSA (Sigma‐Aldrich, A4919) at RT for 1 h. Flag antibody (1:200), HA antibody (1:100) or LAMP1 antibody (1:100) was incubated with slides overnight at 4°C. Slides were washed with 1 × PBS and then incubated with secondary antibodies (1:1,000) and DAPI (1:1,000) for nuclei at 37°C for 1 h. After mounting with fluorescence decay resistant medium (Leagene, IH0252), images were photographed using a Nikon A1 confocal microscope and analyzed with ImageJ software.

Surface biotinylation and Streptavidin pull‐down

Surface proteins from transfected HEK293T cells were labeled with EZ‐LinkTM Sulfo‐NHS‐SS‐Biotin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 21331) according to manufacturer’s protocol. After biotinylation, cells were lysed in TNE lysis buffer supplied with protease inhibitors. Cell homogenates were denatured and incubated with Dynabeads™ M‐280 Streptavidin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 60210) at 4°C for about 12 h. Streptavidin‐bound complexes were eluted by 50 mM DTT (in 100 µl PBS) and then subjected to Flag pull‐down. After washing with PBS containing 0.1% Triton X‐100 for three times, protein‐beads complexes were eluted by Flag peptides and then subjected to immunoblot analysis. Proteins were detected by appropriate antibodies.

Statistical analysis

Densitometric quantification of immunoblotting levels was performed using ImageJ software. Statistical analysis was performed with Prism GraphPad software v8.0.1. The statistical significance of differences between groups was calculated with the two‐tailed unpaired t test unless otherwise stated. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM). P‐values of 0.05 or less were considered statistically significant. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005, and ****P < 0.0001.

Author contributions

QT, XZ and PW conceived the study and designed the major experiments. XZ and YL performed experiments and data analysis in embryos. PW and JW performed experiments and data analysis in cells. JZ and TZ assisted with experiments. QT, XZ and PW wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Review Process File

Expanded View Figures PDF

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Anming Meng and Yeguang Chen for critical reading of manuscript. We thank Dingfei Yan and Dr. Haiteng Deng in Center of Protein Analysis Technology, Tsinghua University, for MS analysis. This work was supported by grants to Q. Tao, the grants were shown as follows: National Key Research and Development Program of China 2019YFA0801403 (Q. Tao), National Natural Science Foundation of China 31970756 (Q. Tao), Beijing Advanced Innovation Center for Structural Biology.

EMBO reports (2021) 22: e53185.

Data availability

The datasets produced in this study are available in the following database: http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/projects/PXD027207. Project PXD027207; Title: Xenopus Hwa IP‐MS in 1 cell stage embryos.

References

- Bellipanni G, Varga M, Maegawa S, Imai Y, Kelly C, Myers AP, Chu F, Talbot WS, Weinberg ES (2006) Essential and opposing roles of zebrafish beta‐catenins in the formation of dorsal axial structures and neurectoderm. Development 133: 1299–1309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blythe SA, Reid CD, Kessler DS, Klein PS (2009) Chromatin immunoprecipitation in early Xenopus laevis embryos. Dev Dyn 238: 1422–1432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannon M, Gomperts M, Sumoy L, Moon RT, Kimelman D (1997) A beta‐catenin/XTcf‐3 complex binds to the siamois promoter to regulate dorsal axis specification in Xenopus . Genes Dev 11: 2359–2370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha BJ, Gard DL (1999) XMAP230 is required for the organization of cortical microtubules and patterning of the dorsoventral axis in fertilized Xenopus eggs. Dev Biol 205: 275–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha SW, Tadjuidje E, Tao Q, Wylie C, Heasman J (2008) Wnt5a and Wnt11 interact in a maternal Dkk1‐regulated fashion to activate both canonical and non‐canonical signaling in Xenopus axis formation. Development 135: 3719–3729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang LS, Kim M, Glinka A, Reinhard C, Niehrs C (2020) The tumor suppressor PTPRK promotes ZNRF3 internalization and is required for Wnt inhibition in the Spemann organizer. Elife 9: e51248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colozza G, De Robertis EM (2014) Maternal syntabulin is required for dorsal axis formation and is a germ plasm component in Xenopus . Differentiation 88: 17–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuykendall TN, Houston DW (2009) Vegetally localized Xenopus trim36 regulates cortical rotation and dorsal axis formation. Development 136: 3057–3065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes R, Tajer B, Kobayashi M, Pelliccia JL, Langdon Y, Abrams EW, Mullins MC (2020) The maternal coordinate system: molecular‐genetics of embryonic axis formation and patterning in the zebrafish. Curr Top Dev Biol 140: 341–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhart JC, Vincent JP, Scharf SR, Black SD, Gimlich RL, Danilchik M (1984) Localization and induction in early development of Xenopus . Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 307: 319–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giebel N, de Jaime‐Soguero A, García Del Arco A, Landry JJM, Tietje M, Villacorta L, Benes V, Fernández‐Sáiz V, Acebrón SP (2021) USP42 protects ZNRF3/RNF43 from R‐spondin‐dependent clearance and inhibits Wnt signalling. EMBO Rep 22: e51415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao HX, Jiang X, Cong F (2016) Control of Wnt receptor turnover by R‐spondin‐ZNRF3/RNF43 signaling module and Its dysregulation in cancer. Cancers 8: 54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao H‐X, Xie Y, Zhang Y, Charlat O, Oster E, Avello M, Lei H, Mickanin C, Liu D, Ruffner H et al (2012) ZNRF3 promotes Wnt receptor turnover in an R‐spondin‐sensitive manner. Nature 485: 195–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harland R, Gerhart J (1997) Formation and function of Spemann's organizer. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 13: 611–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A, Siggers P, Corrochano S, Warr N, Sagar D, Grimes DT, Suzuki M, Burdine RD, Cong F, Koo B‐K et al (2018) ZNRF3 functions in mammalian sex determination by inhibiting canonical WNT signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115: 5474–5479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Saint‐Jeannet JP, Woodgett JR, Varmus HE, Dawid IB (1995) Glycogen synthase kinase‐3 and dorsoventral patterning in Xenopus embryos. Nature 374: 617–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Saint‐Jeannet JP, Wang Y, Nathans J, Dawid I, Varmus H (1997) A member of the Frizzled protein family mediating axis induction by Wnt‐5A. Science 275: 1652–1654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heasman J (2006) Patterning the early Xenopus embryo. Development 133: 1205–1217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heasman J, Crawford A, Goldstone K, Garner‐Hamrick P, Gumbiner B, McCrea P, Kintner C, Noro CY, Wylie C (1994) Overexpression of cadherins and underexpression of beta‐catenin inhibit dorsal mesoderm induction in early Xenopus embryos. Cell 79: 791–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heasman J, Kofron M, Wylie C (2000) Beta‐catenin signaling activity dissected in the early Xenopus embryo: a novel antisense approach. Dev Biol 222: 124–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YL, Anvarian Z, Döderlein G, Acebron SP, Niehrs C (2015) Maternal Wnt/STOP signaling promotes cell division during early Xenopus embryogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 5732–5737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulstrand AM, Schneider PN, Houston DW (2010) The use of antisense oligonucleotides in Xenopus oocytes. Methods 51: 75–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Charlat O, Zamponi R, Yang Y, Cong F (2015) Dishevelled promotes Wnt receptor degradation through recruitment of ZNRF3/RNF43 E3 ubiquitin ligases. Mol Cell 58: 522–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kageura H (1997) Activation of dorsal development by contact between the cortical dorsal determinant and the equatorial core cytoplasm in eggs of Xenopus laevis . Development 124: 1543–1551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly C, Chin AJ, Leatherman JL, Kozlowski DJ, Weinberg ES (2000) Maternally controlled (beta)‐catenin‐mediated signaling is required for organizer formation in the zebrafish. Development 127: 3899–3911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofron M, Birsoy B, Houston D, Tao Q, Wylie C, Heasman J (2007) Wnt11/beta‐catenin signaling in both oocytes and early embryos acts through LRP6‐mediated regulation of axin. Development 134: 503–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo B‐K, Spit M, Jordens I, Low TY, Stange DE, van de Wetering M, van Es JH, Mohammed S, Heck AJR, Maurice MM et al (2012) Tumour suppressor RNF43 is a stem‐cell E3 ligase that induces endocytosis of Wnt receptors. Nature 488: 665–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larabell CA, Torres M, Rowning BA, Yost C, Miller JR, Wu M, Kimelman D, Moon RT (1997) Establishment of the dorso‐ventral axis in Xenopus embryos is presaged by early asymmetries in beta‐catenin that are modulated by the Wnt signaling pathway. J Cell Biol 136: 1123–1136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Seidl C, Sun R, Glinka A, Niehrs C (2020) R‐spondins are BMP receptor antagonists in Xenopus early embryonic development. Nat Commun 11: 5570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macia E, Ehrlich M, Massol R, Boucrot E, Brunner C, Kirchhausen T (2006) Dynasore, a cell‐permeable inhibitor of dynamin. Dev Cell 10: 839–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei W, Jin Z, Lai F, Schwend T, Houston DW, King ML, Yang J (2013) Maternal dead‐End1 is required for vegetal cortical microtubule assembly during Xenopus axis specification. Development 140: 2334–2344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molenaar M, van de Wetering M, Oosterwegel M, Peterson‐Maduro J, Godsave S, Korinek V, Roose J, Destrée O, Clevers H (1996) XTcf‐3 transcription factor mediates beta‐catenin‐induced axis formation in Xenopus embryos. Cell 86: 391–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon RT, Kimelman D (1998) From cortical rotation to organizer gene expression: toward a molecular explanation of axis specification in Xenopus . BioEssays 20: 536–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niehrs C (2004) Regionally specific induction by the Spemann‐Mangold organizer. Nat Rev Genet 5: 425–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusse R, Clevers H (2017) Wnt/β‐catenin signaling, disease, and emerging therapeutic modalities. Cell 169: 985–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Robertis EM, Larraín J, Oelgeschläger M, Wessely O (2000) The establishment of Spemann's organizer and patterning of the vertebrate embryo. Nat Rev Genet 1: 171–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowning BA, Wells J, Wu M, Gerhart JC, Moon RT, Larabell CA (1997) Microtubule‐mediated transport of organelles and localization of beta‐catenin to the future dorsal side of Xenopus eggs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 1224–1229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf SR, Gerhart JC (1980) Determination of the dorsal‐ventral axis in eggs of Xenopus laevis: complete rescue of uv‐impaired eggs by oblique orientation before first cleavage. Dev Biol 79: 181–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider S, Steinbeisser H, Warga RM, Hausen P (1996) Beta‐catenin translocation into nuclei demarcates the dorsalizing centers in frog and fish embryos. Mech Dev 57: 191–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi DL (2020) Decoding dishevelled‐mediated Wnt signaling in vertebrate early development. Front Cell Dev Biol 8: 588370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spit M, Fenderico N, Jordens I, Radaszkiewicz T, Lindeboom RG, Bugter JM, Cristobal A, Ootes L, van Osch M, Janssen E et al (2020) RNF43 truncations trap CK1 to drive niche‐independent self‐renewal in cancer. EMBO J 39: e103932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szenker‐Ravi E, Altunoglu U, Leushacke M, Bosso‐Lefèvre C, Khatoo M, Thi Tran H, Naert T, Noelanders R, Hajamohideen A, Beneteau C et al (2018) RSPO2 inhibition of RNF43 and ZNRF3 governs limb development independently of LGR4/5/6. Nature 557: 564–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Q, Yokota C, Puck H, Kofron M, Birsoy B, Yan D, Asashima M, Wylie CC, Lin X, Heasman J (2005) Maternal wnt11 activates the canonical wnt signaling pathway required for axis formation in Xenopus embryos. Cell 120: 857–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukiyama T, Zou J, Kim J, Ogamino S, Shino Y, Masuda T, Merenda A, Matsumoto M, Fujioka Y, Hirose T et al (2020) A phospho‐switch controls RNF43‐mediated degradation of Wnt receptors to suppress tumorigenesis. Nat Commun 11: 4586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubbels GA, Hara K, Koster CH, Kirschner MW (1983) Evidence for a functional role of the cytoskeleton in determination of the dorsoventral axis in Xenopus laevis eggs. J Embryol Exp Morphol 77: 15–37 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent JP, Gerhart JC (1987) Subcortical rotation in Xenopus eggs: an early step in embryonic axis specification. Dev Biol 123: 526–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent JP, Oster GF, Gerhart JC (1986) Kinematics of gray crescent formation in Xenopus eggs: the displacement of subcortical cytoplasm relative to the egg surface. Dev Biol 113: 484–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver C, Farr GH 3rd, Pan W, Rowning BA, Wang J, Mao J, Wu D, Li L, Larabell CA, Kimelman D (2003) GBP binds kinesin light chain and translocates during cortical rotation in Xenopus eggs. Development 130: 5425–5436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing YY, Cheng XN, Li YL, Zhang C, Saquet A, Liu YY, Shao M, Shi DL (2018) Mutational analysis of dishevelled genes in zebrafish reveals distinct functions in embryonic patterning and gastrulation cell movements. PLoS Genet 14: e1007551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L, Chen J, Zhu X, Sun J, Wu X, Shen W, Zhang W, Tao Q, Meng A (2018) Maternal Huluwa dictates the embryonic body axis through β‐catenin in vertebrates. Science 362: eaat1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Tan C, Darken RS, Wilson PA, Klein PS (2002) Beta‐catenin/Tcf‐regulated transcription prior to the midblastula transition. Development 129: 5743–5752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X, Tamai K, Doble B, Li S, Huang H, Habas R, Okamura H, Woodgett J, He X (2005) A dual‐kinase mechanism for Wnt co‐receptor phosphorylation and activation. Nature 438: 873–877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan T, Rindtorff N, Boutros M (2017) Wnt signaling in cancer. Oncogene 36: 1461–1473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Min Z, Tan R, Tao Q (2015) NF2/Merlin is required for the axial pattern formation in the Xenopus laevis embryo. Mech Dev 138(Pt 3): 305–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Review Process File

Expanded View Figures PDF

Data Availability Statement

The datasets produced in this study are available in the following database: http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/projects/PXD027207. Project PXD027207; Title: Xenopus Hwa IP‐MS in 1 cell stage embryos.