Abstract

Whether alterations in the microtubule cytoskeleton affect the ability of endothelial cells (ECs) to sprout and form branching networks of tubes was investigated in this study. Bioassays of human EC tubulogenesis, where both sprouting behavior and lumen formation can be rigorously evaluated, were used to demonstrate that addition of the microtubule-stabilizing drugs, paclitaxel, docetaxel, ixabepilone, and epothilone B, completely interferes with EC tip cells and sprouting behavior, while allowing for EC lumen formation. In bioassays mimicking vasculogenesis using single or aggregated ECs, these drugs induce ring-like lumens from single cells or cyst-like spherical lumens from multicellular aggregates with no evidence of EC sprouting behavior. Remarkably, treatment of these cultures with a low dose of the microtubule-destabilizing drug, vinblastine, led to an identical result, with complete blockade of EC sprouting, but allowing for EC lumen formation. Administration of paclitaxel in vivo markedly interfered with angiogenic sprouting behavior in developing mouse retina, providing corroboration. These findings reveal novel biological activities for pharmacologic agents that are widely utilized in multidrug chemotherapeutic regimens for the treatment of human malignant cancers. Overall, this work demonstrates that manipulation of microtubule stability selectively interferes with the ability of ECs to sprout, a necessary step to initiate and form branched capillary tube networks.

The molecular basis for how endothelial cells (ECs) form branched networks of tubes has gradually been elucidated over the past several decades.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 EC branching morphogenesis requires coordinated sprouting behavior and lumen formation. EC sprouts are led by tip cells, which serve as an invading front to initiate and stimulate EC tube branching behavior.3,14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 A critical tool to investigate the details of these processes has been the development of sophisticated in vitro model systems that allow for investigations of the molecular and signaling requirements for each of the steps in vascular morphogenesis.18,23, 24, 25, 26, 27

Serum-free defined models of EC sprouting behavior and EC tubulogenesis from ECs seeded in three-dimensional (3D) matrices as individual cells have been developed from ECs seeded on a monolayer surface, or as EC-EC aggregates.18,26, 27, 28 These models have allowed us to define molecule, signaling, and growth factor requirements for these processes. Five growth factors (ie, factors: stem cell factor, IL-3, stromal-derived factor-1α, fibroblast growth factor-2, and insulin), when added in combination, allow human ECs to form branched networks of tubes.26,27 These EC-lined tubes markedly attract pericytes, which leads to tube maturation events, including extended and narrow tubes with an abluminally deposited basement membrane matrix.29, 30, 31 These assembled EC-pericyte tube networks strongly mimic what is observed in vivo as capillary networks.

A key regulator of vascular morphogenesis is the EC cytoskeleton, with known major roles for actin, tubulin, and intermediate filaments.32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 Over the years, a variety of studies have highlighted important roles for microtubules in EC function and have also implicated their function in controlling the ability of ECs to both form and stabilize tube networks.34,37,42 For example, addition of microtubule depolymerizing agents, such as vinblastine or colchicine, can collapse EC-lined tubes in a manner dependent on RhoA-mediated cell contractility.34,35 Post-translational modifications, including acetylation and detyrosination, which stabilize microtubules, increase in abundance when ECs form lumens and tubes.27,35 In addition, acetylated tubulin was found to be subapically polarized during EC lumen formation and to direct the membrane trafficking of vacuoles to fuse at the developing apical membrane surface.36,37 In fact, acetylated tubulin tracks were found to be in close contact with these trafficking vacuoles as they approach the apical membrane domain.36,37 These studies suggest that more stabilized microtubules were necessary to control both the formation and maintenance of EC tubes by supporting the apical membrane surface. These observations are supported by the addition of colchicine or proinflammatory mediators that cause EC tube collapse and regression leading to a marked reduction in the levels of acetylated tubulin.35,44

A major utility of pharmacologic agents that stimulate microtubule instability (eg, vinblastine and vincristine) or microtubule stability (ie, paclitaxel and docetaxel) is the ability of both classes of agents to interfere with cell proliferation because of the critical role of tubulin in the assembly and function of the mitotic spindle. Thus, these agents are a major part of successful chemotherapeutic regimens that have been thought to primarily target malignant tumor cell proliferation and survival.45, 46, 47, 48, 49 However, it is possible that these agents may be effective anti-cancer agents for other reasons, such as their potential effects on the supporting vasculature. Support for this concept can be seen in the literature, including studies showing that microtubule-depolymerizing agents can disrupt the vasculature in the cancer microenvironment.34,50,51 There has been much less emphasis on potential effects of these agents on vascular morphogenesis, a major focus of this study.

This study addressed this latter issue by investigating the influence of both stabilizing and destabilizing drugs for microtubules and made the novel observation that both classes of drugs can markedly and selectively inhibit EC sprouting behavior and can prevent EC tip cells from invading during EC morphogenic events. Paclitaxel, docetaxel, ixabepilone, epothilone B, and vinblastine completely blocked EC tip cell behavior and prevented EC branching tube morphogenesis in assays that mimic either vasculogenesis or angiogenesis. Interestingly, paclitaxel, docetaxel, ixabepilone, and epothilone B, at doses of 100 and 10 nmol/L, blocked EC sprouting behavior, while having no inhibitory effect on EC lumen formation. Vinblastine, at a 10 nmol/L dose, blocked EC sprouting, but not EC lumen formation, whereas a 100 nmol/L dose blocked both sprouting and lumen formation (accompanied by reduced acetylated tubulin levels). Furthermore, 100 nmol/L vinblastine induced marked collapse and regression of pre-existing tube networks. Interestingly, addition of paclitaxel (100 or 10 nmol/L) or 10 nmol/L vinblastine induced collapse of forming and branched tube networks, suggesting that dynamic microtubules are necessary to form and maintain EC-lined tube networks. Finally, the ability of these microtubule regulatory drugs to block EC sprouting behavior correlated with an increased expression ratio of acetylated/tyrosinated tubulin, which represented stable versus unstable tubulin forms, respectively. Overall, this novel work demonstrated a fundamental influence of increased microtubule stabilization that selectively interferes with EC sprouting behavior and tip cells to block EC branching morphogenesis, a critical process that is necessary to vascularize tissues.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Morphogenic Assays

Human umbilical vein ECs were from Lonza (Basel, Switzerland) (passages 3 to 6) and were grown and cultured as previously described.23 Vascular morphogenic assays consisted of the following: i) vasculogenesis assays, where individual ECs were seeded as single cells within 3D collagen matrices; ii) EC-EC aggregate assays, where aggregates were seeded in 3D collagen gels; and iii) EC sprouting assays, where ECs invade from a monolayer surface. The detailed methods to perform these assays have been described previously.18,23,28,52 In all cases, the bioassays were performed in serum-free defined media consisting of Medium 199, reduced serum supplement II (that contains insulin), 50 μg/mL of ascorbic acid, as well as recombinant stem cell factor, IL-3, stromal-derived factor-1α, and fibroblast growth factor-2, which were added at a final concentration of 40 ng/ml.26 The recombinant growth factors were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Under these conditions, EC survival occurs in all cases, and dramatic morphogenesis is observed, including EC sprouting behavior, lumen formation, and the formation of branched networks of EC-lined tubes within 3D collagen matrices (collagen gels are made up at 2.5 mg/mL of rat tail collagen type I). Cultures were fixed with 3% glutaraldehyde and were stained with 0.1% toluidine blue. Assays were quantitated for EC tube area, tip cell number, and EC invasion using MetaMorph software version 7.10.2.240 (MetaMorph Inc., San Jose, CA), as described previously.18,23

Bioassays with Pharmacologic Agents

In most of the assays, pharmacologic agents were added into the defined growth factor–containing culture media at the onset of the culture using the vasculogenic, aggregate, or invasion assay systems. In several cases, EC tube formation was allowed to proceed for various times, the culture medium was removed, and then replaced with medium containing the defined growth factors, but also varying doses of the pharmacologic agents, such as paclitaxel or vinblastine. In these latter assays, cultures were fixed and stained in the same manner as described above. Paclitaxel, docetaxel, vinblastine, GM6001, DBZ, DAPT, forskolin, and tubacin were from Tocris (Minneapolis, MN). Epothilone B and ixabepilone were from MedChemExpress (Monmouth Junction, NJ), whereas PP2 was from Calbiochem (Burlington, MA) and 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) was from Biomol (Hamburg, Germany).

In Vivo Paclitaxel Treatments and Retina Studies

All animal experiments were approved by and performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation (protocol number20 to 15). Animal studies were conducted at Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation and followed the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines. C57Bl/6J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and were mated to generate pups. On postnatal day 2, pups were injected subcutaneously under their back skin with vehicle [5% dimethyl sulfoxide in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)] or with paclitaxel resuspended to 500 nmol/L or 1 μmol/L concentrations. For the paclitaxel 500 nmol/L injections, 30 μL of paclitaxel or vehicle was injected in littermate pups; for the paclitaxel 1μmol/L injections, 60 μL of paclitaxel or vehicle was injected. At the time of injections, one toe was clipped from each pup to encode which treatment it received, and pups were returned to their dams for further rearing. Whole eyes from postnatal day 6 pups were enucleated and placed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes and then washed with PBS. Retina cups were dissected out, and hyaloid vessels were carefully removed. Retinas were washed in PBS and blocked in block/permeabilization buffer (0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 1 hour at room temperature. Retinas were then washed three times in PBS and were incubated in goat anti-mouse CD31 overnight at 4°C. The next day, retinas were washed three times in PBS and were incubated in fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated donkey–anti-goat IgG for 1 hour at room temperature. After staining, retinas were washed three times in wash buffer (PBS/0.3% Triton X-100) at room temperature, then two times in PBS only, then flat mounted by cutting four radial slits in the retina to generate a flower petal arrangement. Retinas were then mounted with ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA), and images were captured on a Nikon Eclipse Ti-E epifluorescence microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY) with NIS-Elements software version 4.60.00 (Nikon). For retina studies, all annotations were blinded, and fields were chosen at random throughout the entire retina. Fiji ImageJ software version 1.53k (NIH, Bethesda, MD; https://imagej.nih.gov/ij, last accessed June 28, 2021) was used to measure the distance between the vascular front and the edge of each retina. MATLAB R2020a software, from MathWorks (Natick, MA), was used to measure total retinal vessel area and to count vascular branches. A minimum of four measurements from a single eye were averaged together and represented as a single dot on the graphs. All graphs for retinal studies were generated, and statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Statistical tests, sample sizes, and error bars are described in the figure legends.

Western Blot Analysis

Lysates were prepared from 3D gels, and Western blot analyses were run and probed with various antibodies. Antibodies directed to acetylated tubulin, tyrosinated tubulin, and α-tubulin were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Phosphorylated histone H3, histone H3, and procaspase 3 antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA), and an actin antibody was from Calbiochem. Phalloidin conjugated with AlexaFluor 488 was from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR).

Acetylated and Tyrosinated Tubulin Ratio Analysis

Bio-Rad Gel Doc XR+ Image System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) was used for imaging after applying horseradish peroxidase–linked antibody and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) chemiluminescent substrate to the membranes. The image before overexposure of either one of the bands was chosen, and band intensity was quantitated using ImageJ version Java 1.8.0_172. Background signal was subtracted before acquiring the expression ratio of acetylated tubulin/tyrosinated tubulin. The ratio from each repeat of the experiments was normalized to its control. t-test was used to compare means between two conditions, while statistical significance was set at a minimum of P < 0.05. All analyses were obtained using a minimum of n = 3 per experiment.

Immunostaining of Cultures

The 24-hour EC aggregate assays were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde. Gels were subjected, in sequence, to Tris-glycine buffer solution (1 hour), Triton X-100 solution (1 hour), blocking solution (1 hour), primary antibody (overnight), and secondary antibody (2 hours), as previously described.35,36

Imaging and Microscopy

Stained in vitro cultures from the various assays were imaged using an inverted microscope with imaging DP Controller software version 3.2.1.276 (Olympus, Center Valley, PA). Video time-lapse microscopy of living cells was performed using a DMI6000B microscope from Leica (Wetzlar, Germany) and MetaMorph software version 7.8 (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA). Confocal images were obtained using a Leica SP8 LIGHTNING White light laser confocal laser scanning microscope as well as LAS software version LAS X (Leica). All images were obtained using a 20× objective lens. Confocal images were generated using Fiji ImageJ.

Data and Statistical Analysis

Statistical data analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel from Microsoft (Seattle, WA) and Prism 8 (GraphPad Software). Data were analyzed for normality, equal variances were obtained, and t-tests were used to compare means between two conditions while statistical significance was set at a minimum of P < 0.05. All analyses were obtained using a minimum of n = 12 fields per experiment, and ≥3 validating experimental replicates in total.

Results

Paclitaxel Selectively Inhibits EC Tip Cell Behavior and Thereby Blocks EC Branching Tube Morphogenesis

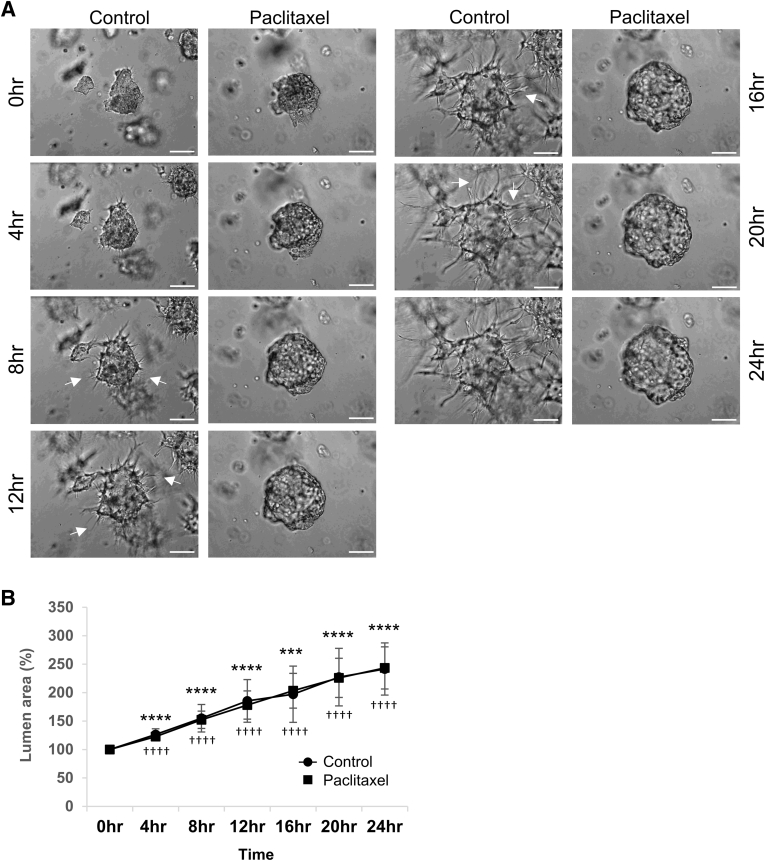

Microtubule cytoskeleton has been implicated in promoting EC tube formation and stabilization.34,35 Post-translational modifications of tubulin, including acetylated and detyrosinated tubulins, show increased accumulation during EC tubulogenesis.27,35 Interestingly, acetylated tubulins show a strong subapical distribution and surround vacuoles and vesicles that deliver membranes to the developing apical membrane surface.36,37 Herein, pharmacologic agents known to increase the levels of these post-translationally modified tubulins were added and their impact on EC tubulogenesis and sprouting behavior were assessed (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4). One such drug is paclitaxel, which strongly increases both tubulin acetylation and detyrosination in cells and is known to be a proliferation inhibitor for malignant cancers in chemotherapeutic regimens. The experiments were performed in three different ways, whereby individual ECs were seeded i) as single cells in 3D collagen matrices in assays mimicking vasculogenesis, ii) as part of multicellular EC-EC aggregates, and iii) as sprouting assays from an EC monolayer surface. The EC aggregate assays were used to visualize both lumen formation and sprouting behavior from a multicellular EC structure (Supplemental Figure S1A). Remarkably, the addition of paclitaxel at different doses markedly blocked the ability of ECs to sprout during EC tubulogenic events (Figure 1), from a monolayer surface (Figure 1, E and F, and Figure 3C), or from EC-EC aggregates (Figures 1, B–D, and 2). In contrast, addition of paclitaxel did not block the ability of ECs to form lumens, whether they were seeded as single cells or aggregated cells (Figures 1 and 2). Measurements of lumen area over time using real-time movies and EC aggregate assays (Figure 2A) demonstrate that paclitaxel did not interfere with the rate of lumen formation over time compared with controls (Figure 2B), despite its strong ability to block EC sprouting behavior (Figure 2A).

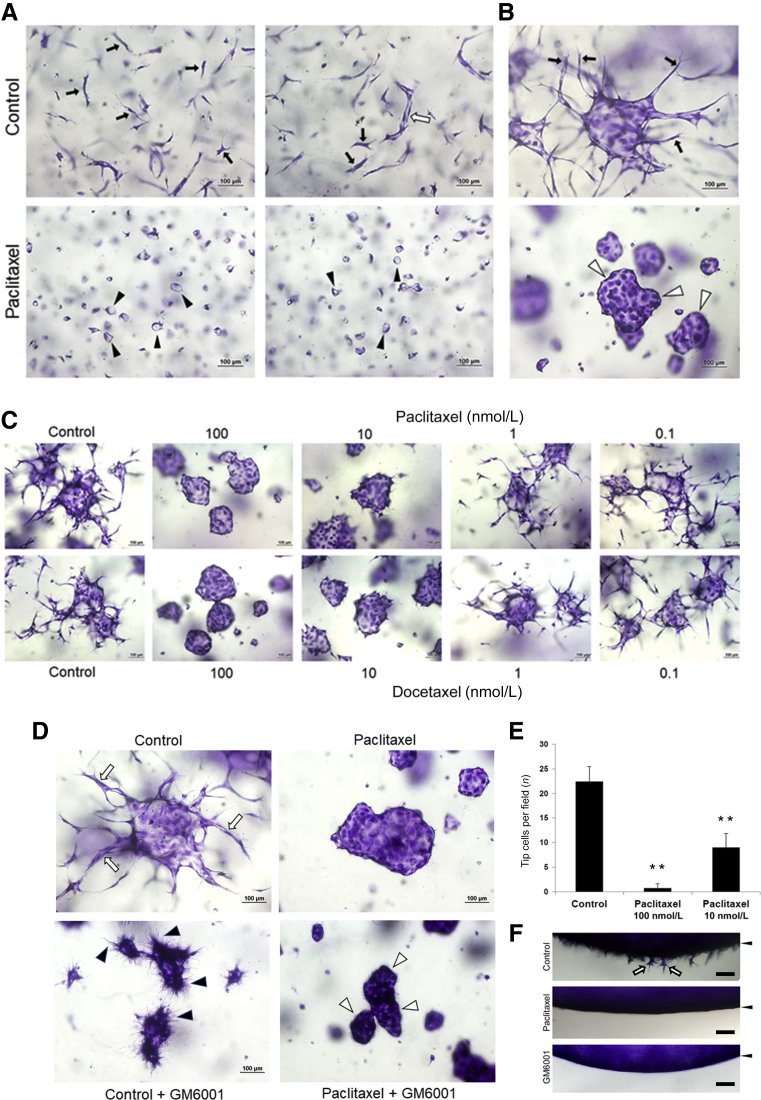

Figure 1.

The microtubule-stabilizing agents, paclitaxel and docetaxel, markedly block endothelial cell (EC) sprouting behavior and EC tip cell formation during EC tubulogenesis. A: Cultures were established using ECs seeded as single cells in the presence of control media or media containing paclitaxel at 100 nmol/L and were fixed, stained, and imaged at 24 hours. Black arrows indicate EC tip cells; white arrow, an EC tube with a defined lumen; and arrowheads, single EC rings, which are lumen structures. B: EC-EC aggregate cultures were established in the absence or presence of 100 nmol/L paclitaxel and were fixed and stained at 24 hours. Arrows indicate EC tip cells leading EC sprouts; and arrowheads indicate the borders of EC aggregates, which have a central lumen structure with no evident sprouts. C: EC aggregates were cultured in the absence or presence of the indicated (and varying) doses of paclitaxel and docetaxel. After 24 hours, cultures were fixed and stained. D: EC aggregate cultures were established in the absence or absence of paclitaxel at 100 nmol/L or the matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor, GM6001, at 10 μmol/L. Cultures were fixed, stained, and imaged after 24 hours. Arrows indicate EC sprouts with evident lumens; black arrowheads, filopodia-like processes that are absent from the paclitaxel + GM6001 cultures; and white arrowheads, the border of EC aggregates, which have no lumen or filopodia-like processes. E and F: EC invasion assays from a monolayer surface were performed in the presence of the indicated drugs and were fixed, stained, imaged, and quantitated at 16 hours. F: After 16 hours, cultures were cross-sectioned to visualize EC invasion from a monolayer surface (arrowheads); arrows indicate invading EC tip cells. ∗∗P < 0.01 versus control. Scale bars = 100 μm (A–D and F).

Figure 2.

Endothelial cell (EC) lumen formation as well as the rate of lumen expansion are unaffected by paclitaxel compared with controls using EC aggregate assays, whereas sprouting behavior is completely inhibited. A: Representative images from control (left panels) versus 10 nmol/L paclitaxel (right panels) treated EC aggregate movies at 0, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 hours. Arrows denote tip cell sprouts. B: Quantitative analysis of EC aggregate lumen area over time, comparing control versus paclitaxel-treated cultures. EC lumen area per field was determined by tracing EC lumens using MetaMorph software version 7.8 from time-lapse images at the indicated time points. All time points of control and 10 nmol/L paclitaxel aggregate lumen area were normalized to 0 hours control and 10 nmol/L paclitaxel, respectively. n = 7 fields per time point for control cultures (A, left panels); n = 6 fields per time point for 10 nmol/L paclitaxel-treated cultures (A, right panels). ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001 versus control at 0 hours; ††††P < 0.0001 versus paclitaxel at 0 hours. Scale bars = 100 μm (A).

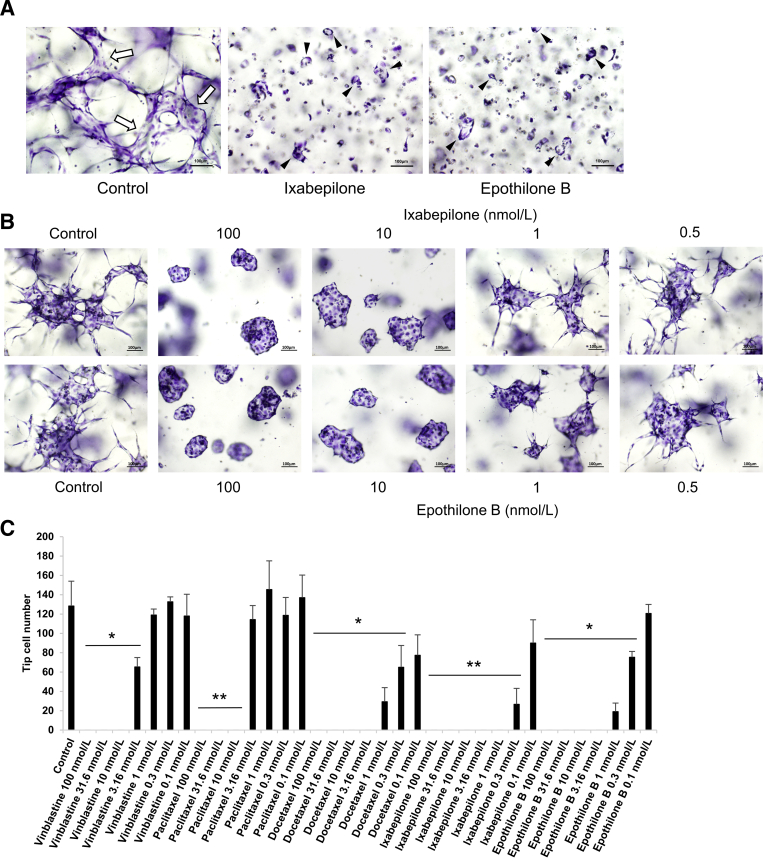

Figure 3.

The microtubule-stabilizing agents, ixabepilone and epothilone B, markedly block endothelial cell (EC) sprouting behavior and EC tip cell formation during EC tubulogenesis. A: Cultures were established using ECs seeded as single cells in the presence of control media or media containing ixabepilone or epothilone B at 7.5 nmol/L and were fixed, stained, and imaged at 72 hours. Arrows indicate an EC tube with a defined lumen; and arrowheads indicate EC rings, which are lumen structures. B: EC aggregates were cultured in the absence or presence of the indicated (and varying) doses of ixabepilone and epothilone B. After 24 hours, cultures were fixed and stained. C: Dose-response curves of the indicated pharmacologic agents, and doses are shown when added during EC sprouting assays. ECs were seeded as a monolayer on top of the collagen and were allowed to sprout downwards for 16 hours. Cultures were fixed, stained, and imaged, and tip cell number was quantitated. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 versus control. Scale bars = 100 μm (A and B).

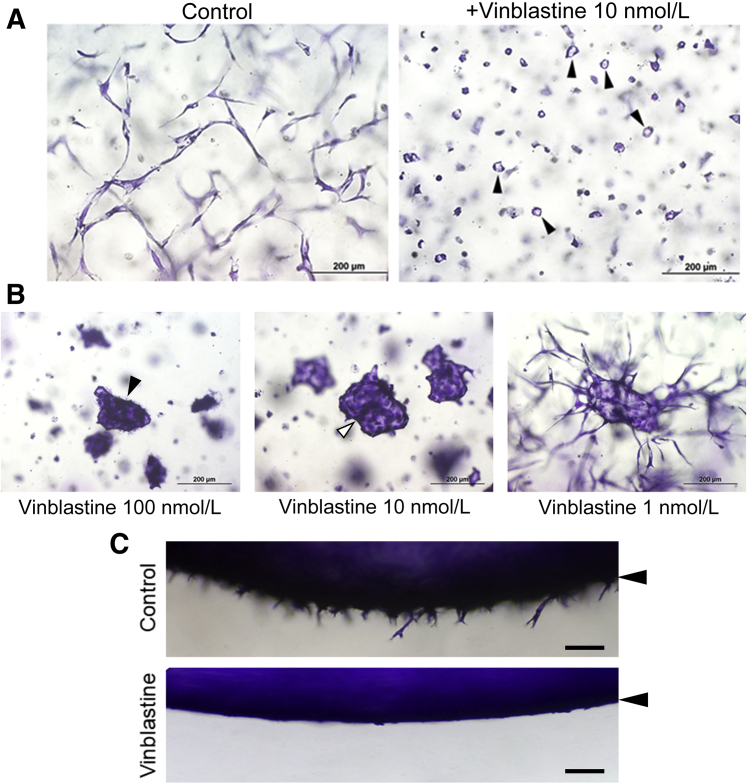

Figure 4.

The microtubule-depolymerizing agent, vinblastine, selectively inhibits endothelial cell (EC) sprouting behavior and EC tip cells, while allowing for EC lumen formation at low doses. A: ECs were seeded as single cells and were either left untreated or treated with 10 nmol/L vinblastine, and then fixed and stained after 24 hours. Arrowheads indicate EC rings, which are circular lumens. B: EC aggregates were treated with varying indicated doses of vinblastine. Black arrowhead indicates EC aggregate with no luminal space; and white arrowhead indicates EC aggregate with an open luminal space. C: EC sprouting assays were performed for 16 hours under control conditions versus vinblastine addition at 10 nmol/L. After fixation, cultures were stained and cross-sectioned. Arrowheads indicate the position of the EC monolayer surface. Scale bars: 200 μm (A and B); 100 μm (C).

In the aggregate assay, the ability of ECs to sprout or form multicellular lumens is completely dependent on matrix metalloproteinases, such as membrane-type (MT)1–matrix metalloproteinase, as the addition of GM6001 markedly blocks both lumen formation and sprouting (Figure 1, D and F). GM6001 also completely inhibits multicellular EC lumen formation after paclitaxel addition (Figure 1D). ECs resembling elongated tip cells were abundantly observed in the control vasculogenesis assays, but their extended morphology was completely inhibited by paclitaxel addition. Instead, the ECs had small lumens and appeared as rings (Figure 1A). A pharmacologic drug combination called FIST (ie, abbreviation for the drug combination, forskolin, IBMX, SB239063, and tubacin) that strongly accelerates the formation of EC lumens and branched tube networks has recently been identified.44 The addition of FIST stimulated EC tubulogenesis, but in the presence of paclitaxel, the branching pattern of tubes was completely inhibited and the elongated tip-like cells and instead, much larger EC rings were observed compared with control conditions (Supplemental Figure S2A).

Other Microtubule-Stabilizing Drugs, including Docetaxel, Epothilone B, and Ixabepilone, also Selectively Block EC Sprouting

EC-EC aggregate assays were performed to further support these findings and conclusions, and extensive EC sprouting was observed under control conditions. Addition of paclitaxel completely inhibited this sprouting response (Figure 1B), and dose-response experiments revealed marked blocking effects at both 100 and 10 nmol/L, but not at 1 nmol/L or 100 pmol/L (Figure 1, C and E). The related microtubule-stabilizing drug, docetaxel, induced the same marked blocking effect on EC sprouting behavior in similar dose ranges as paclitaxel (Figure 1C). To analyze these drugs further, the sprouting blocking effects of paclitaxel and docetaxel were quantitated using the invasion assay from an EC monolayer surface (Figure 3C). Docetaxel showed greater potency, but both drugs blocked completely at ≥10 nmol/L levels and their inhibitory influence titrated out at lower levels (Figure 3C).

The role of two other microtubule-stabilizing drugs, epothilone B and ixabepilone, that act through a similar mechanism by binding to a competitive tubulin binding site common with paclitaxel was assessed. These drugs have improved clinical efficacy in anti-tumor treatments due to less overall toxicity and are less prone to the development of drug resistance compared with the taxane drugs. They are also comparatively more potent as anti-mitotic agents.45,46,53, 54, 55, 56 The current study corroborated these results, whereby these drugs markedly blocked sprouting behavior by evaluating EC sprouting ability in vasculogenesis assays (Figure 3A), from EC-EC aggregates (Figure 3B), or from a monolayer surface (Figure 3C). Interestingly, epothilone B and ixabepilone could still strongly block sprouting at 1 nmol/L, showing greater potency than either paclitaxel or docetaxel (Figure 3). In contrast, lumen formation in the aggregates occurred normally, just like with paclitaxel and docetaxel (Figure 3, A and B). Overall, these data demonstrate that pharmacologic agents that are known to stabilize tubulin selectively interfere with EC sprouting behavior, but not the ability of ECs to form lumens (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3).

Real-Time Video Analysis Demonstrates Marked Blockade of EC Tip Cells and Sprouting Behavior from EC-EC Aggregates Treated with Paclitaxel, Docetaxel, Epothilone B, or Ixabepilone

Real-time videos were used to visualize the blocking influence of paclitaxel on EC sprouting, but not lumen formation, from EC-EC aggregate cultures (Supplemental Videos S1–S4 and Figure 1, B and C). Control EC-EC aggregates demonstrated marked lumen expansion over time, with concomitant EC sprouts emanating from multiple places within each aggregate (Supplemental Videos S1 and S2). Note that lumen formation was visualized behind the control EC tip cells over time. In marked contrast, paclitaxel addition at 100 nmol/L completely inhibited EC sprouting from these aggregates (Supplemental Videos S3 and S4 and Figure 1, B and C). However, over time, EC lumen formation and expansion occured in the multicellular EC-EC aggregates treated with paclitaxel. Similarly, real-time videos show that the addition of docetaxel at either 100 or 10 nmol/L to aggregates led to the inhibition of sprouting but is accompanied by marked EC lumen expansion (Supplemental Videos S5 and S6 and Figure 1C). Addition of epothilone B and ixabepilone at 100, 10, or 1 nmol/L also led to the marked inhibition of EC sprouting from aggregates while lumen expansion was observed (Supplemental Videos S7–S12 and Figure 3B) compared with control (Supplemental Video S13 and Figure 3B). Interestingly, at the 10 or 1 nmol/L dose, but particularly observed at 1 nmol/L, tip cells were seen emerging from aggregates, but they retracted and returned to the EC-EC aggregates that were expanding as multicellular EC lumens (Supplemental Videos S8–S12). These results suggest that the ability to dynamically regulate microtubule stability appears to be necessary to sustain EC sprouting behavior and maintain the ability of EC tip cells to invade forward.

In contrast, addition of a matrix metalloproteinases inhibitor, GM6001, completely inhibited EC sprouting behavior, but also EC lumen formation from the aggregates (Supplemental Video S14 and Figure 1D). Filopodia-like processes were observed emanating from the ECs in the aggregate, but the EC tip cells did not leave the EC-EC aggregates. These data, coupled with that shown and discussed above, demonstrate a selective ability of paclitaxel, docetaxel, epothilone B, and ixabepilone to block EC tip cells and sprouting behavior, without interfering with the ability of single or groups of ECs to form lumens.

The Microtubule-Depolymerizing Agent Vinblastine Can also Selectively Block EC Tip Cells and Sprouting Behavior when Added at Low Doses

Addition of the microtubule depolymerization agent vinblastine to pre-existing networks of tubes results in collapse and regression of these networks.34 Though, in the prior studies,34 vinblastine was used at 100 nmol/L, the current study tested the effect of adding varying doses of vinblastine on EC sprouting behavior and lumen formation (Figure 4). Remarkably, vinblastine added at 10 nmol/L to ECs seeded as single cells or EC-EC aggregates resulted in marked blockade of EC tip cells and sprouting behavior. In fact, the phenotype observed strongly resembled what occurs when paclitaxel is added at either 100 or 10 nmol/L. When added to single ECs, vinblastine at 10 nmol/L induced small EC rings (ie, single-cell lumens) and interfered with EC tip cell formation, such that there was no branching pattern of developing tubes (Figure 4A). Using an EC sprouting assay from a monolayer surface also revealed complete blockade of sprouting following vinblastine treatment (Figure 4C). In EC-EC aggregate assays, addition of 100 or 10 nmol/L, but not 1 nmol/L, vinblastine led to complete inhibition of sprouting. Note the similarity of the EC aggregate response to vinblastine at 10 nmol/L compared with paclitaxel at 100 or 10 nmol/L (Figure 4B). However, addition of 100 nmol/L vinblastine also resulted in a lack of lumen formation in EC-EC aggregates (Figure 4B). A real-time video of this response is shown to demonstrate this lack of lumen formation in response to this higher dose of vinblastine at 100 nmol/L (Supplemental Video S15). In contrast, the sprouting response from EC-EC aggregates was completely inhibited, but lumen formation and expansion occurred normally when vinblastine was added at 10 nmol/L (Supplemental Video S16), compared with control aggregates (Supplemental Video S17).

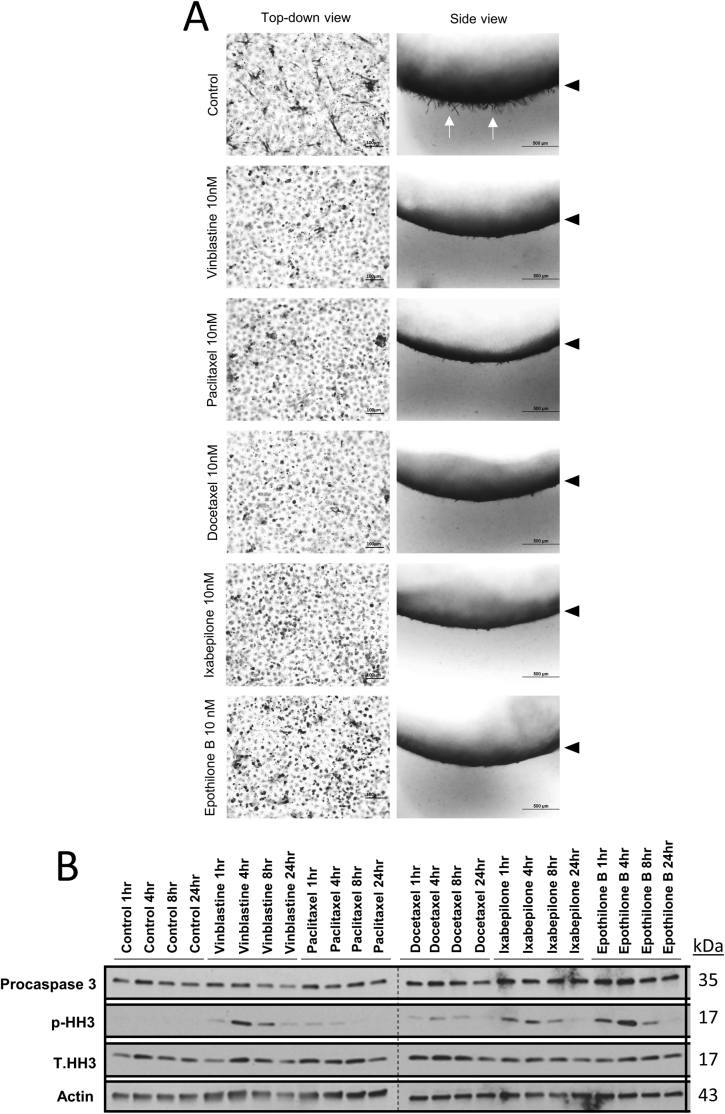

Both the microtubule-stabilizing agents (paclitaxel, docetaxel, ixabepilone, and epothilone B) and the microtubule-destabilizing agents (vinblastine) are known to negatively impact cell proliferation and survival as part of their therapeutic efficacy against malignant tumor cells.45, 46, 47, 48, 49 Additional experiments and analyses were performed to address whether such effects could account for the observed inhibitory effects on EC sprouting behavior. Though sprouting behavior was strongly inhibited, EC lumen did not form during the time frame of the assays (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4). In fact, EC lumen expansion (and lumen area measurements) from aggregates occured at the same rate following paclitaxel treatment compared with controls (Figure 2). If EC survival was significantly impacted, this result would not occur. To address this issue further, invasion assays were performed for 24 hours using the downward monolayer assay, comparing each of the microtubule modulatory drugs (Supplemental Figure S3). In each case, these drugs inhibited sprouting behavior, as visualized from a cross-sectional side view or from the top down (Supplemental Figure S3A). In the latter case, the drug-treated monolayers appeared intact despite the lack of sprouting observed with each of them. Lysates were prepared at 24 hours, and Western blot analyses were examined for total levels of procaspase 3 (as another measure of cell survival) and for phosphorylated histone H3, to examine whether EC proliferation was affected or could account for the findings. A modest decrease in procaspase 3 levels was observed with vinblastine treatment, whereas the other treatments showed little to no effect compared with controls (Supplemental Figure S3B). In addition, there was no evidence for EC proliferation in the control cultures, with no changes in phosphorylated histone 3 levels (Supplemental Figure S3B). There were some increases in EC proliferation in the vinblastine-, ixabepilone-, and epothilone B–treated cultures, particularly seen at 4 hours of culture. However, it was strongly down-regulated by 24 hours. Down-regulation of EC proliferation during tube morphogenic events in 3D matrices31,57 is consistent with that reported during vascular development.58 Overall, these data indicate that neither survival nor proliferative effects of these pharmacologic agents directed at microtubules can account for their strong inhibitory influence on EC sprouting behavior.

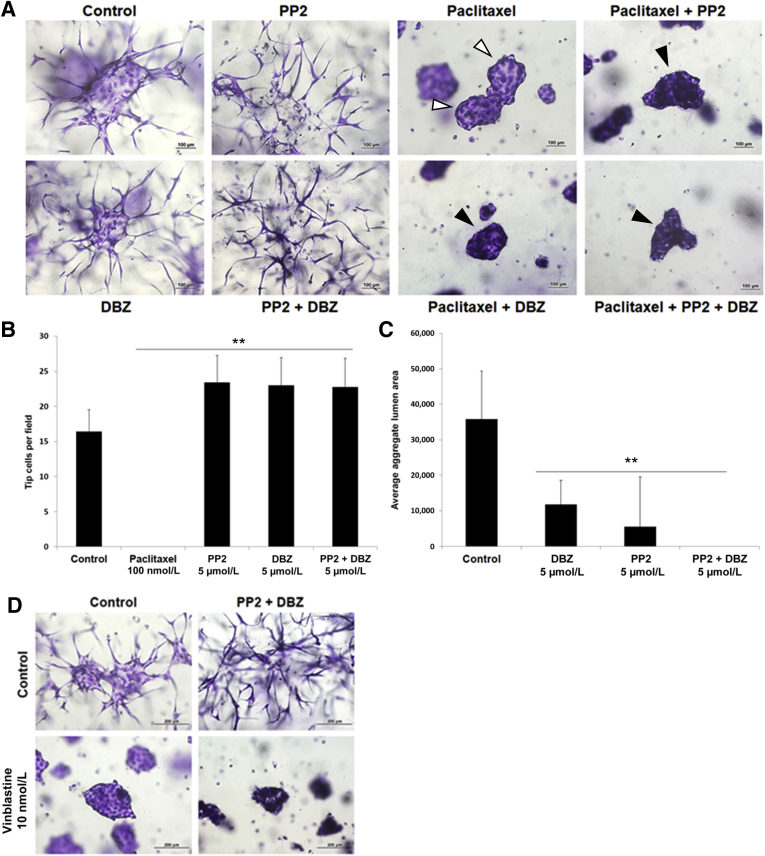

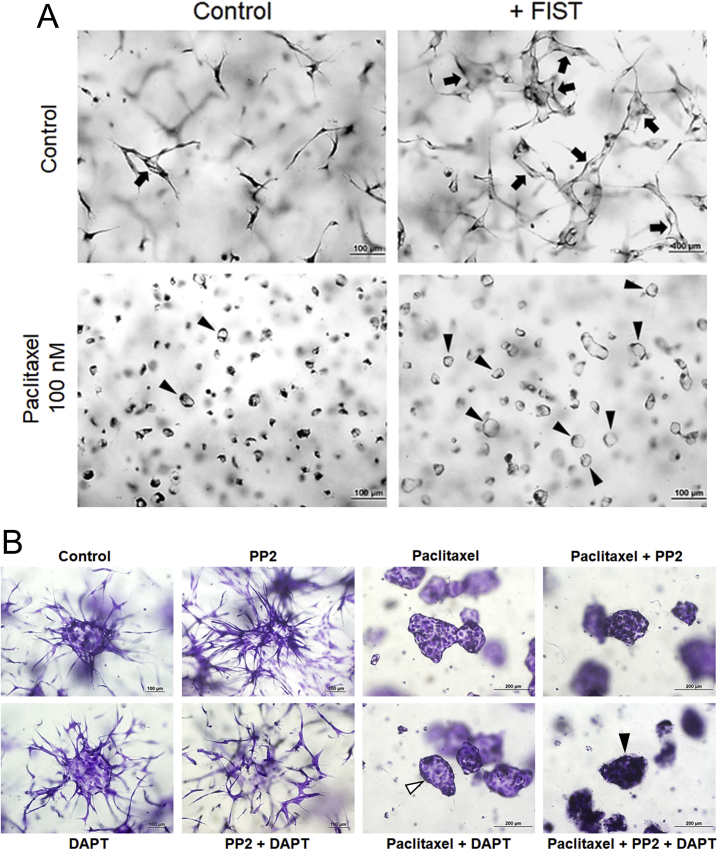

SFK and Notch Signaling Blockade Leads to Marked Increases in EC Sprouting Behavior, which Is Completely Inhibited by Paclitaxel or Vinblastine

Blockade of Src family kinases (SFKs) leads to marked inhibition of EC lumen formation.36 An interesting consequence of this inhibition of lumen formation is a concomitant increase in the number of EC tip-like cells.18,36 Herein, addition of inhibitors of SFKs (PP2), Notch (DBZ), or both led to marked increases in tip-like cells and EC sprouting behavior in EC-EC aggregates (Figure 5, A and B, and Supplemental Videos S18–S20). In contrast, lumen formation was markedly suppressed by these treatments compared with control (Figure 5, B and C). Paclitaxel completely inhibited the marked EC tip cell and sprouting increases observed following blockade of SFK with PP2 or Notch signaling with DBZ (Figure 5A). Experiments using a second Notch inhibitor, DAPT, provided results identical to those with DBZ (Supplemental Figure S2B). Interestingly, although paclitaxel did not block EC lumen formation in control aggregates, it was not able to rescue the lumen inhibiting influence of SFK or Notch inhibition, individually, or in combination (Figure 5A and Supplemental Figure S2B). A key reason that SFK and Notch blockade leads to markedly increased EC tip-like cells is that these inhibitors strongly interfere with lumen formation. The results demonstrate that paclitaxel has a selective and marked ability to block EC tip cells and EC sprouting behavior, even in cases where dramatic EC sprouting should be occurring following inhibition of SFK and Notch signaling (Figure 5, Supplemental Videos S18–S20, and Supplemental Figure S2B).

Figure 5.

Src family kinase and Notch blockade markedly increases endothelial cell (EC) sprouting behavior and tip cells, which are completely inhibited by paclitaxel or vinblastine. A: EC aggregates were treated with the indicated drugs; and after 24 hours, cultures were fixed, stained, and imaged. White arrowheads indicate aggregates with an open central lumen; and black arrowheads indicate aggregates with no sprouts or lumen. B: Quantification of EC tip cells from A. C: Quantification of EC lumen area from the aggregates from A. D: EC aggregates were treated with the indicated drugs; and after 24 hours, cultures were fixed, stained, and imaged. ∗∗P < 0.01 versus control. Scale bars: 100 μm (A); 200 μm (D).

The effect of vinblastine at 10 nmol/L in EC sprouting occurring in response to combined SFK and Notch blockade was assessed. Vinblastine completely inhibited this response and, interestingly, the combination of this blockade with SFK and Notch blockade resulted in complete inhibition of EC-EC aggregate lumen formation compared to that with vinblastine alone at 10 nmol/L (Figure 5D).

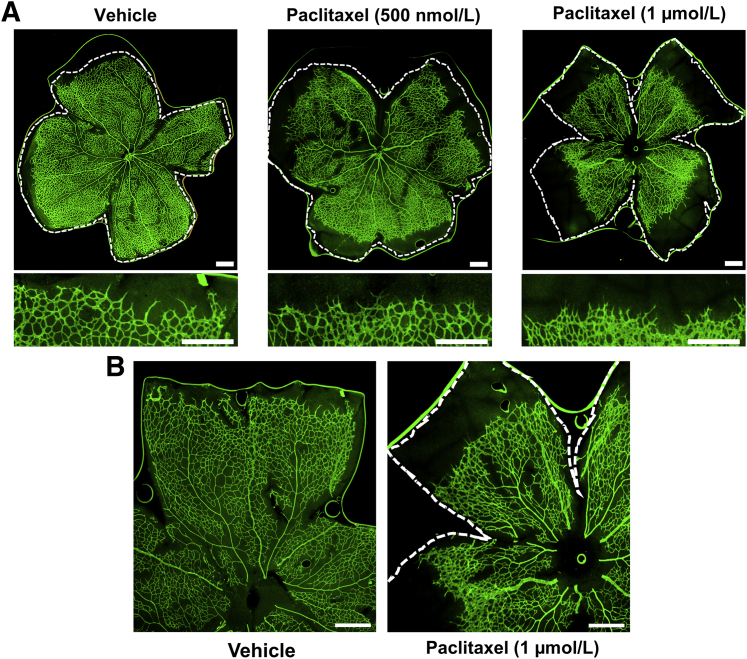

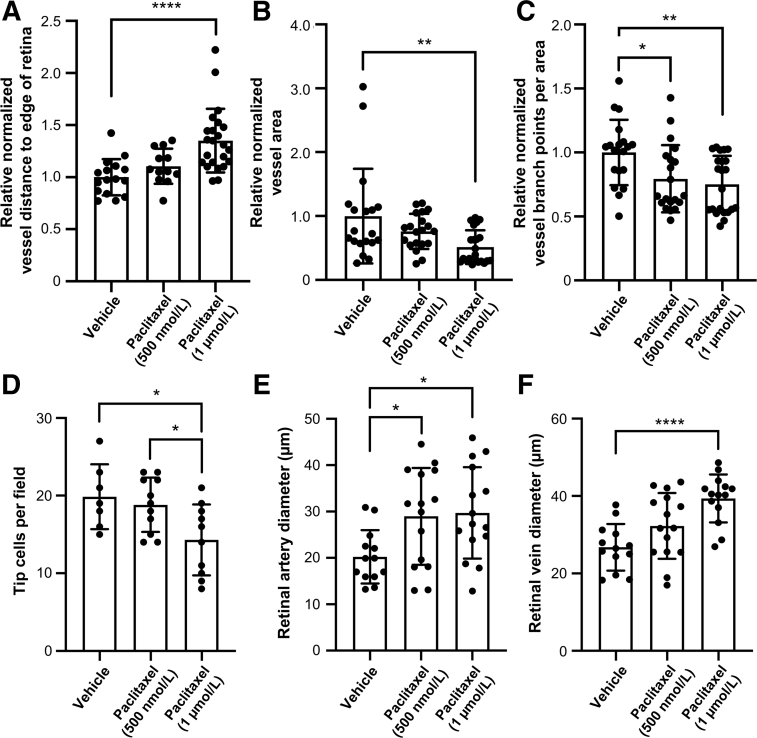

Paclitaxel Blocks Angiogenic Sprouting Behavior in Vivo during Mouse Retinal Development

To determine the impact of paclitaxel on sprouting angiogenesis in vivo, the drug was administered to mouse pups and vascular development in newborn retinas was assessed. Specifically, C57Bl/6J littermate pups were injected subcutaneously with paclitaxel (500 nmol/L or 1 μmol/L) or with vehicle on postnatal day 2 and were returned to their dams for further rearing. On postnatal day 6, retinas were dissected, whole mount immunostained with anti–platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 for blood vessel detection, flat mounted, and imaged. Retinal vessels grow outward in mice during the first week of life, extending from the center of the retina to the outer periphery. Significantly compromised retinal vessel growth, as indicated by an increased distance from the vascular front to the outer edge of the retina, was observed in eyes harvested from pups injected with 1 μmol/L paclitaxel (Figure 6). Vascular outgrowth was also blunted in pups treated with paclitaxel, 500 nmol/L, although not to the same extent as those treated with paclitaxel, 1 μmol/L (Figures 6 and 7A). These outgrowth defects translated into significantly less total retinal vessel area in pups treated with paclitaxel, 1 μmol/L, and a downward trend in vessel area in pups treated with paclitaxel, 500 nmol/L, compared with vehicle-treated pups (Figure 7B). Finally, pups treated with paclitaxel, both 500 nmol/L and 1 μmol/L, showed significantly fewer retinal vascular branches than littermate pups treated with vehicle (Figure 7C). Altogether, these data indicate that paclitaxel has a dose-dependent and negative impact on vascular branching and outgrowth in newborn mouse retinas in vivo, thereby validating the inhibitory effects of the drug on sprouting angiogenesis in our in vitro assays. In further support of these findings and conclusions, EC tip cell numbers were quantitated using a double-staining technique with anti-CD31 and anti-Ets–related gene (Ets) antibodies (Supplemental Figure S1B). Paclitaxel was seen to significantly reduce the number of EC tip cells during retinal angiogenesis (Figure 7D). Finally, artery and vein diameter were evaluated in these samples and paclitaxel treatment at both doses was shown to increase the luminal width of arteries and veins (Figure 7, E and F). This indicated that paclitaxel treatment is compatible with lumen formation in vivo, just like in vitro, while markedly interfering with EC sprouting behavior.

Figure 6.

Paclitaxel treatment inhibits retinal angiogenesis in mouse pups. C57Bl/6J littermate pups were injected subcutaneously on postnatal day 2 with vehicle or paclitaxel at the indicated doses. Retinas were dissected and analyzed on postnatal day 6. A: Top panels: Representative images of flat mount retinas that were immunostained with anti–platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 (green) for blood vessel visualization. The dashed white lines indicate the edge of the retina. Bottom panels: Higher-power images of the invasion front are shown for each condition. B: Higher-power images are shown from control versus paclitaxel treatment. The dashed white line indicates the edge of the retinal tissue. Scale bars = 500 μm (A and B).

Figure 7.

Blockade of retinal vascular sprouting with paclitaxel, which also increases retinal arterial and vein diameters. C57Bl/6J littermate pups were injected subcutaneously on postnatal day 2 (P2) with vehicle or paclitaxel; retinas were dissected and analyzed on postnatal day 6 (P6). A: The average distance from the vascular front to the edge of the retina was measured for individual eyes (12 measurements per eye) and normalized to vehicle-treated eyes. B: The retinal vascular area was measured for individual eyes and normalized to vehicle-treated eyes. C: The number of vessel branch points was measured for individual eyes and normalized to vehicle-treated eyes. A–C: Statistics were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett multiple-comparisons correction. D: Endothelial cell tip cells were counted in multiple fields of comparably magnified images (×20 each, as in A) from animals treated with vehicle (two pups), 500 nmol/L paclitaxel (three pups), and 1 μmol/L paclitaxel (three pups). Statistics were performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple-comparisons correction. E and F: Paclitaxel treatment increases artery and vein diameters in mouse pup retinas. C57Bl/6J littermate pups were injected subcutaneously on P2 with vehicle or paclitaxel; retinas were dissected and analyzed on P6. Retinal vessels were immunostained with anti–platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 for visualization, and arteries and veins were distinguished in flat-mounted retinas by the stereotypical capillary clearance immediately adjacent to the arteries. E and F: To calculate artery (E) and vein (F) diameters, the outer edge of the vascular front was outlined and then digitally shrunk by 50%, and the diameter of first-order vessels crossing the shrunken line was measured with Fiji ImageJ software version 1.53k. Each dot represents an individual vessel diameter; at least six eyes were analyzed per treatment group. Statistics were performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple-comparisons correction. Error bars indicate SD (A–F). n = 16 eyes (A, vehicle); n = 12 eyes (A, paclitaxel at 500 nmol/L); n = 23 eyes (A, paclitaxel at 1 μmol/L); n = 19 eyes (D and E, vehicle); n = 20 eyes (D and E, paclitaxel at 500 nmol/L); n = 22 eyes (D and E, paclitaxel at 1 μmol/L). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

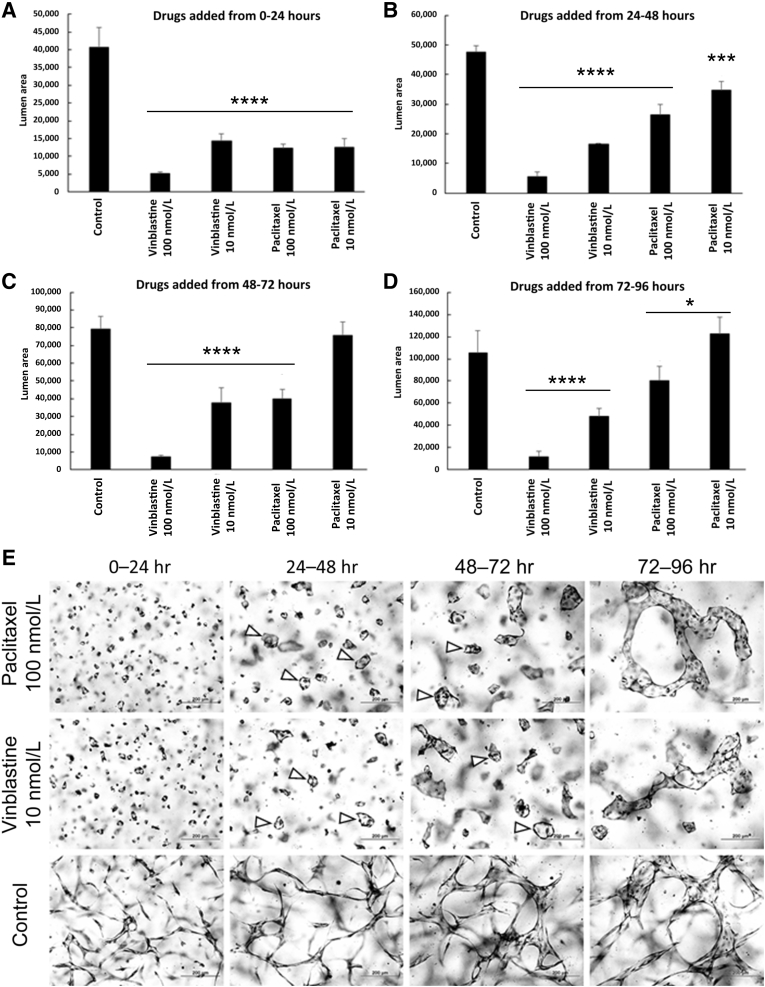

Maintenance of a Branched Pattern of EC Tube Networks Depends on a Dynamic Microtubule Cytoskeleton

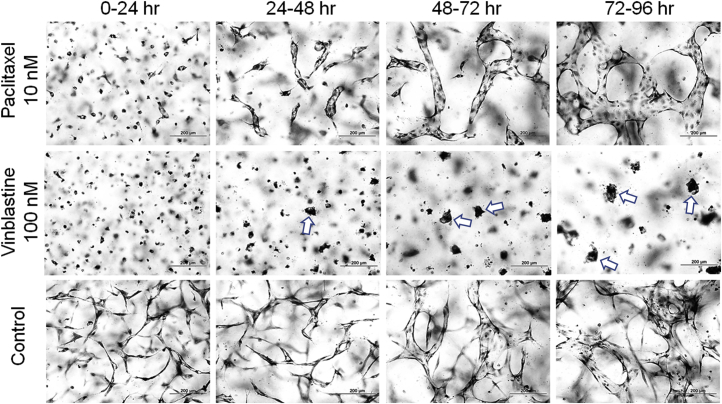

To address whether the microtubule cytoskeleton plays a role in maintaining an established branched network of EC-lined tubes, different doses of vinblastine and paclitaxel were administered at 0, 24, 48, or 72 hours, and the cultures were examined 24 hours later (Figure 8 and Supplemental Figure S4). Remarkably, addition of these drugs after EC tip cells and branching patterns had formed for 24, 48, or 72 hours markedly reversed the branching patterns, leading to full collapse of EC tubes at 100 nmol/L vinblastine (Figure 8 and Supplemental Figure S4). On the other hand, with 10 nmol/L vinblastine or 100 nmol/L paclitaxel, branching tubes retracted and rounded up into EC luminal cysts (particularly seen from 24 to 48 or 48 to 72 hours) (Figure 8). The rounded-up cysts were less apparent at 72 to 96 hours; however, clear retraction of the branching patterns of tubes was observed with both 10 nmol/L vinblastine and 100 nmol/L paclitaxel doses. The influence of vinblastine and paclitaxel at these two doses was similar in spite of thier opposite effects of either destabilizing or stabilizing the tubulin cytoskeleton, respectively. Reductions in EC tube area following these treatments were observed in all cases, except for the addition of 10 nmol/L paclitaxel from 48 to 72 or 72 to 96 hours compared with controls (Figure 8 and Supplemental Figure S4).

Figure 8.

Paclitaxel and low-dose vinblastine induce collapse of forming and branched endothelial cell (EC)–lined tubes into EC cyst-like luminal structures. Paclitaxel (100 nmol/L) and vinblastine (10 nmol/L) were added in the indicated time intervals versus control treated cultures. At the end of the 24-hour treatment period, cultures were fixed, stained, and imaged (E), and quantitated for EC lumen area (A–D). Arrowheads indicate the EC cyst-like structures that result from collapse of the branched tube networks. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, and ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001. Scale bars = 200 μm (E).

Modulation of EC-EC Aggregate Lumen Formation and Post-Translational Tubulin Modifications by Paclitaxel, Vinblastine, and Other Agents

The ability of different doses of paclitaxel and vinblastine to affect lumen formation in EC-EC aggregates was compared and the degree of post-translational tubulin modifications and their relationship to the lumen formation response was analyzed (Supplemental Figure S5). Addition of paclitaxel at 100 or 10 nmol/L resulted in increased lumen formation relative to control (Supplemental Figure S5A), and Western blot analyses revealed markedly increased levels of acetylated and detyrosinated tubulin compared with control (Supplemental Figure S5B). Vinblastine added at 100 nmol/L resulted in blockade of lumen formation, whereas lower doses, including 10 nmol/L, did not interfere with lumen formation from the EC-EC aggregates (Supplemental Figure S5A). Treatment of ECs with 100 nmol/L vinblastine markedly decreased the levels of acetylated tubulin, whereas it did not affect the levels of detyrosinated tubulin (Supplemental Figure S5B). Thus, the inhibition of lumen formation by 100 nmol/L vinblastine addition correlated with the loss of acetylated tubulin. In support of this conclusion are previous findings showing that vacuoles and vesicles that control lumen formation are decorated with acetylated tubulin (which is located subapically) as they deliver membranes to the developing apical surface.36,37 In addition, a marked decrease in the acetylation of tubulin is observed during capillary tube regression.44

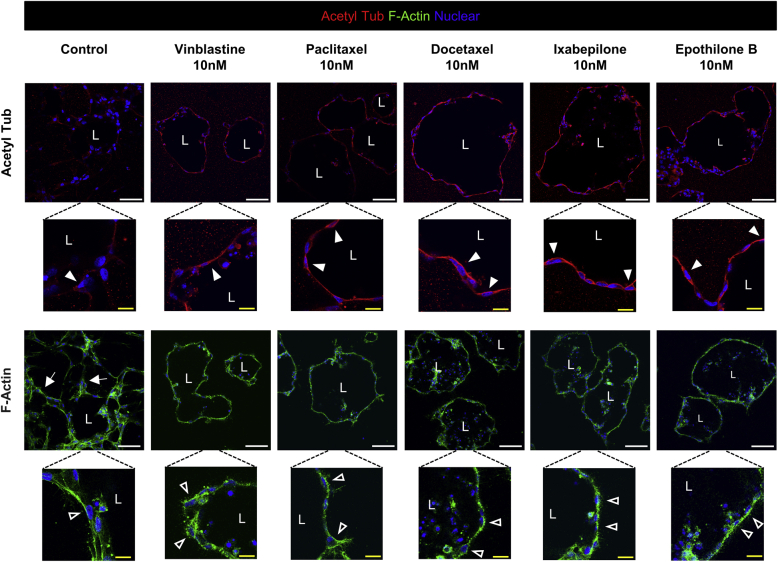

To address whether we could visualize cytoskeletal changes in response to the microtubule modulatory agents, the study examined the distribution of acetylated tubulin or filamentous actin using confocal microscopy in the treated versus control EC aggregate cultures (Supplemental Figure S6). Each of the agents added at 10 nmol/L increased the levels of acetylated tubulin compared with the control and, furthermore, its distribution was polarized in a subapical manner (Supplemental Figure S6). It is possible that this increased acetylated tubulin, present in a subapical region, stabilizes the apical membrane surface and plays a direct role in preventing these ECs from invading as single cells, a prerequisite to initiate a sprouting response. In contrast, staining for filamentous actin revealed a predominant basal distribution in the lumen-forming ECs (Supplemental Figure S6).

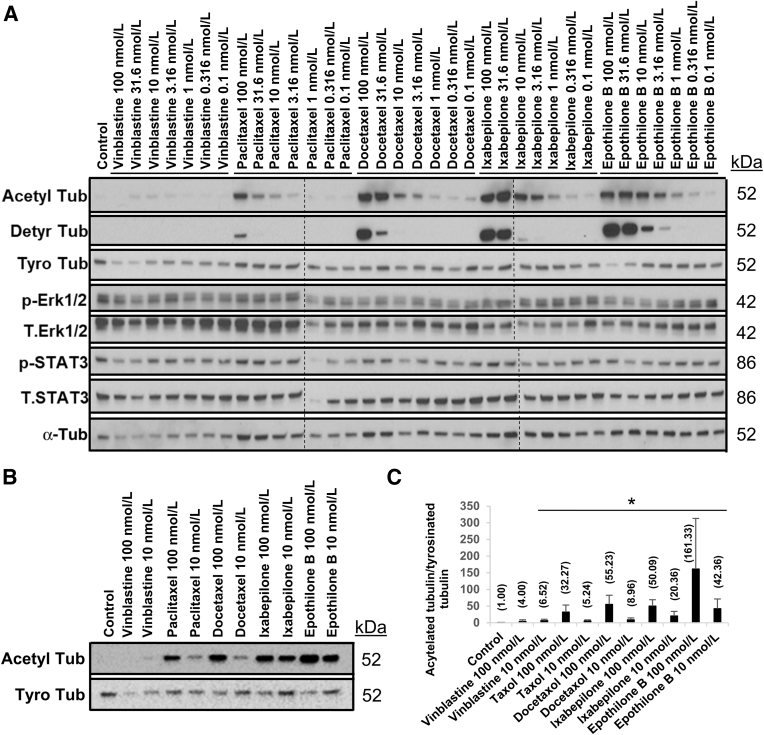

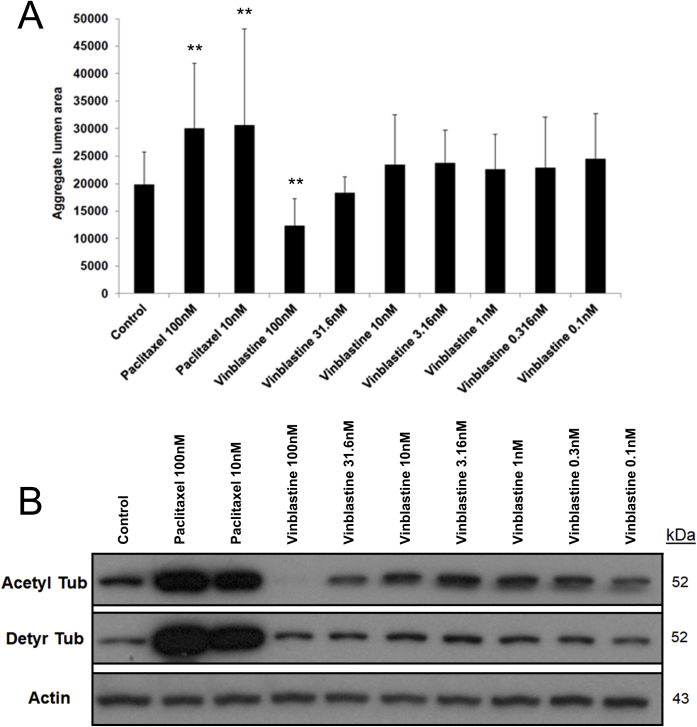

A Dynamic Microtubule Cytoskeleton May Be Necessary to Induce and Sustain EC Tip Cells and Sprouting Behavior

As a rule, dynamic microtubules that are rapidly turned over are tyrosinated, whereas acetylated and detyrosinated microtubules are more stable. To address how the above tubulin-targeting drugs affect tubulin dynamics and the levels of post-translational tubulin modifications, varying doses of vinblastine, paclitaxel, docetaxel, ixabepilone, and epothilone B were added to EC sprouting assays. Because of their distinct potencies in blocking EC sprouting behavior (Figure 3C), the study sought to correlate their pharmacologic functional effects with their influence on tubulin modifications, including acetylation, detyrosination, and tyrosination (Figure 9A). Other potential signaling events that may play a role in EC sprouting behavior were assessed, including Janus kinase (JAS)-Stat and extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling. Lysates were collected at 16 hours, and Western blot analyses were performed (Figure 9A). Vinblastine reduced acetylated tubulin expression at 100 nmol/L and increased acetylated tubulin expression from 31.6 to 0.1 nmol/L in a dose-dependent manner, whereas detyrosinated tubulin expression was not observed. Paclitaxel, docetaxel, ixabepilone, and epothilone B all increased acetylated and detyrosinated tubulin levels in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 9A). Notably, ixabepilone and epothilone B, which act through a mechanism similar to that of paclitaxel, were able to induce greater acetylated tubulin and detyrosinated tubulin expression levels, even at low doses (Figure 9A), which correlated with the drugs' increased potency in blocking EC tip cell invasion compared with paclitaxel (Figures 3C and 9A). Whether other major signals contribute to the observed sprouting defects with these drugs was assessed next. Activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and STAT3 expression showed no correlation with either tip cell inhibition or the effects of the different drug doses on the observed tubulin modifications (Figure 9A). Interestingly, an increase of acetylated tubulin expression correlated best with inhibition of tip cell sprouting behavior seen in the dose-response experiments (Figure 3C).

Figure 9.

Dose-response influence of microtubule regulatory drugs on post-translational tubulin (Tub) modifications that affect endothelial cell (EC) sprouting behavior. A: Vinblastine, paclitaxel, docetaxel, ixabepilone, and epothilone B were added at doses ranging from 100 to 0.1 nmol/L during sprouting assays. Lysates were collected at 16 hours, and Western blot analysis was performed to assess the indicated Tub modifications and signaling molecules. Tubulin acetylation (Acetyl Tub), tubulin detyrosination (Detyr Tub), and tubulin tyrosination (Tyro Tub) were examined. Dashed lines indicate the borders of the different blots that were compiled for the figure. B: Vinblastine, paclitaxel, docetaxel, ixabepilone, and epothilone B were added at 100 and 10 nmol/L. Lysates were collected at 16 hours, and Western blot analyses were probed for acetylated and tyrosinated tubulin. C: Immunoblot quantification of the acetylated tubulin/tyrosinated tubulin ratio. Average values for each condition are shown in parentheses. n = 3 (C). ∗P < 0.05. p-Erk1/2, phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2; p-STAT3, phosphorylated STAT3; T.Erk1/2, total extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2; T.STAT3, total STAT3.

An exception to this appeared to be vinblastine, which only slightly increased acetylated tubulin expression at inhibitory doses (particularly observed at 10 nmol/L). However, vinblastine reduced tyrosinated tubulin expression levels (a less stable form of tubulin), suggesting that the overall net effect might still shift to more stable tubulin, leading to interference with EC sprouting behavior. This led to the possibility that quantitative measurements of the ratio of acetylated tubulin/tyrosinated tubulin might be predictive for whether EC sprouting is inhibited by these pharmaceutical agents (Figure 9). To address this question further, the five tubulin modification drugs were added at either 100 or 10 nmol/L during sprouting assays, and lysates were collected after 16 hours. All tubulin modifiers completely inhibited tip cell sprouting behavior at both doses (Figure 3C). Western blot analyses were performed to evaluate the levels of acetylated versus tyrosinated tubulin (Figure 9B). Strong increases in tubulin acetylation were observed with the tubulin-stabilizing agents, whereas a weaker increase was seen with 10 nmol/L vinblastine. Interestingly, this increase in acetylation by low-dose vinblastine was accompanied by a decrease in tyrosinated tubulin. Next, the ratio of acetylated tubulin/tyrosinated tubulin was quantitated in each of these samples (Figure 9C). This analysis revealed that all tubulin-stabilizing drugs at either 10 or 100 nmol/L and vinblastine at 10 nmol/L showed a significantly higher acetylated/tyrosinated tubulin ratio (Figure 9C) that correlated with inhibition of EC sprouting behavior (Figure 3C).

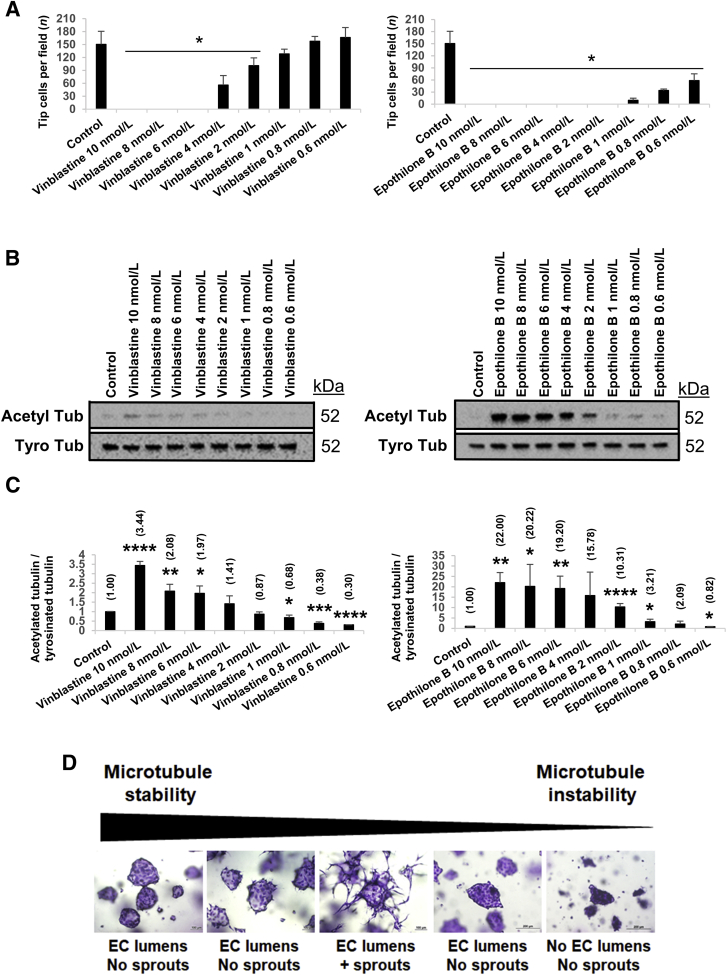

An Elevated Ratio of Acetylated to Tyrosinated Tubulin, Induced by Microtubule-Modifying Pharmacologic Agents, Correlates with an Inability of ECs to Sprout

The effect of vinblastine versus epothilone B, the most potent tubulin stabilizer were studied to assess the relationship between the ratio of acetylated/tyrosinated tubulin and EC sprouting behavior (Figure 10). Dose-response curves of the two drugs ranged from 10 to 0.6 nmol/L. EC cultures were fixed, stained, and quantitated for tip cell numbers after 16 hours (Figure 10A). Lysates were collected from these sprouting assays at 16 hours. While vinblastine completely inhibited tip cell sprouting at 6 to 10 nmol/L, it began to titrate out at lower doses (Figure 10A). Epothilone B completely inhibited tip cell sprouting at doses from 2 to 10 nmol/L, and at lower doses, its inhibitory activity titrated out (Figure 10A). Western blot analysis showed that both drugs induce tubulin acetylation in the dose ranges that block EC sprouting, whereas there was a modest decrease in tyrosinated tubulin in the 6 to 10 nmol/L range with vinblastine (Figure 10B). Quantitative measurements of the ratio of acetylated/tyrosinated tubulin revealed a clear dose-response curve in the dose ranges of both vinblastine and epothilone B that blocked EC sprouting (Figure 10C). There was a strong correlation between an increasing acetylated/tyrosinated ratio, which led to blockade of EC sprouting. A ratio of two or above correlated with marked reductions in EC sprouting, whereas below that, sprouting behavior resumed and the inhibitory effects of the drugs titrated out (Figure 10, A and C). Overall, these novel findings demonstrate that a dynamic microtubule cytoskeleton (ie, with optimized levels of stable versus unstable tubulin forms) is necessary for EC sprouting ability and the ability to assemble branched networks of EC-lined tubes (Figure 10D). In addition, this dynamic microtubule cytoskeleton is also necessary to maintain the elongated and branched pattern of such networks once they have formed (Figure 8 and Supplemental Figure S4). Finally, increasing microtubule stabilization, although inhibiting EC tip cells and sprouting behavior, is compatible with the ability of ECs to form lumens, and furthermore, may enhance the formation and maintenance of EC luminal spaces (Figure 10D).

Figure 10.

Increasing the ratio of acetylated tubulin (Acetyl Tub)/tyrosinated tubulin (Tyro Tub) by microtubule-modifying agents markedly decreases endothelial cell (EC) sprouting behavior. Vinblastine and epothilone B were added at doses ranging from 10 to 0.6 nmol/L during sprouting assays. A: Cultures were fixed at 16 hours, stained, imaged, and quantitated. B: Lysates were collected at 16 hours, and Western blot analysis was performed to assess the levels of Acetyl Tub versus Tyro Tub as a measure of more stable versus less stable tubulin forms, respectively. C: Immunoblot quantification of the ratio between acetylated tubulin/tyrosinated tubulin expression. D: Schematic illustrating that an optimal level of stable versus unstable tubulin isoforms is necessary for EC sprouting to occur during vascular morphogenesis. Increasing the levels of stable tubulin blocks EC sprouting, whereas EC lumen formation occurs normally. In contrast, decreasing tubulin stability below a certain level fails to support EC sprouting or lumen formation. n = 5 (C). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, and ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001 versus control. Scale bars: 100 μm (D, left three images); 200 μm (D, right two images).

Discussion

This study presents novel insights into how the microtubule cytoskeleton plays a central role in regulating a major step in vascular morphogenesis (namely, EC sprouting behavior), which is essential in the ability of ECs to form branched and interconnected networks of tubes in 3D matrices. It identified both microtubule stabilizing and depolymerizing pharmacologic agents and doses that can selectively inhibit EC sprouting and tip cell invasion, a necessary step required for EC branching tube morphogenesis. These agents include paclitaxel, docetaxel, ixabepilone, and epothilone B, which stabilize microtubules, and vinblastine, which depolymerizes microtubules. For example, using a 10 nmol/L dose for each of these drugs led to remarkable blockade of EC tip cell function that completely abolished sprouting behavior without affecting the ability of ECs to form lumens. In fact, application of these drugs to individual ECs led to small circular luminal rings, whereas addition to EC-EC aggregates led to the expansion of a multicellular luminal structure, which is predominantly spherical without any evidence of sprouting. Addition of these drugs to ECs seeded on a monolayer surface completely inhibited the ability of EC tip cells to invade into collagen matrices. This novel data set illustrates how dramatically blood vessel morphogenesis can be manipulated in a pharmacologic manner, resulting in dramatic vessel remodeling and patterning. In addition, this work demonstrates why it is essential to perform highly defined in vitro studies to uncover novel information concerning the ability and requirements of ECs to form and maintain tube networks (ie, their essential functional role). A key point is that the microtubule targeted drugs investigated (ie, paclitaxel, docetaxel, ixabepilone, epothilone B, and vinblastine) are major elements of successful chemotherapeutic regimens for malignant cancers in humans.

This novel study demonstrates that these agents have important biological effects that extend far beyond their known inhibitory influence on tumor cell proliferation and cell cycle progression. The detailed in vitro serum-free defined approach and analysis allows for ready screening of pharmacologic agents for effects on distinct steps in vascular morphogenesis. This approach allows for the development of strategic therapeutic regimens to stimulate or inhibit blood vessel assembly in specific ways, such as to selectively interfere with EC sprouting behavior, as shown in this study. Furthermore, the systematic screening indicated that ixabepilone and epothilone B, which act through a similar mechanism as paclitaxel, show greater potency and significantly inhibit tip cell sprouting, even at doses as low as 1 nmol/L. Addition of paclitaxel at 1 nmol/L was ineffective at blocking EC tip cell sprouting.

The work described herein, demonstrating a key role for microtubule dynamics in EC sprouting and branching tubulogenesis, further extends information demonstrating major roles for tubulin and its post-translationally modified forms (ie, acetylation and detyrosination) in the molecular control of EC morphogenesis and function. There is an increasing appreciation for the role of microtubules and tubulin modifications in other key cellular events, such as myocardial contractility, neuronal process extension and morphogenesis, and mechanosensory functions.59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67 Previous studies have demonstrated a role for microtubule assembly and tubulin modifications in EC lumen and tube formation.35 Remarkably, both acetylated and detyrosinated tubulins were shown to accumulate in ECs undergoing tube formation, with increases in acetylation occurring first, followed by detyrosination.35 Of great interest is the observation that acetylated tubulin is highly enriched subapically and observed to be in close contact with vacuoles and vesicles being trafficked apically, suggesting that these modified tubulin tracks are guiding vesicles to migrate, fuse, and generate the apical membrane.36,37 In support of this work, a recent study reported that reduced tubulin detyrosination (a marker of tubulin stabilization) was observed in the compromised vasculature of placentas from preeclamptic patients compared with control patients.68 This interesting finding suggests that reduced tubulin stability in the vasculature of these patients might contribute to reduced vascular integrity and placental vessel density in this disease context.

A key finding in the work presented herein is the differences identified in tubulin requirements controlling the ability of ECs to sprout as tip cells versus the ability of ECs to form lumens. Remarkably, increasing tubulin stability with paclitaxel, docetaxel, ixabepilone, and epothilone B or decreasing tubulin stability with vinblastine led to a similar outcome of EC sprouting inhibition, whereas lumen formation proceeded normally. The lack of sprouting behavior under these circumstances led to the formation of EC rings (ie, small circular lumens) from single ECs or EC cysts from multicellular EC aggregates. These findings suggest that formation of EC tip cells and the generation of branched EC tube networks requires dynamic microtubule properties. In contrast, EC lumen formation appears to require more microtubule stability. When high-dose vinblastine (100 nmol/L) is added to preformed EC tubes, marked decreases in tubulin acetylation occur, which correlates with tube collapse and regression. Moreover, when high-dose vinblastine is added to ECs from the beginning of morphogenesis, they show no ability to form lumens or tubes. Thus, at particular doses, microtubule-stabilizing or microtubule-destabilizing agents can completely abrogate the ability of ECs to make branching networks of tubes through selective interference with EC sprouting. Also, the ratio of acetylated tubulin/tyrosinated tubulin was shown to representing more stable tubulin versus unstable tubulin, respectively, was predictive in determining whether tip cell–regulated EC sprouting occurs. Markedly decreased sprouting was observed as the ratio of acetylated/tyrosinated tubulin increased (above a level of two). Thus, invading EC tip cells required dynamic microtubules containing optimal levels of both acetylated tubulin and tyrosinated tubulin. Overall, these findings add to a growing body of literature demonstrating why it is essential to investigate and elucidate the underlying biology (ie, molecule and signaling requirements) of EC sprouting and tubulogenesis, because the formation of branched networks of EC-lined tubes was required for tissue vascularization. This understanding is also necessary to be able to manipulate the vasculature in the context of disease states, such as malignant cancers, vascular malformations, and diabetes or to promote and stabilize the vasculature of bioengineered tissues.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grants HL136139 (G.E.D.), HL126518 (G.E.D.), HL149748 (G.E.D.), and HL144505 (C.T.G.).

P.K.L. and J.S. contributed equally to this work.

Disclosures: None declared.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2021.08.017.

Author Contributions

P.K.L., J.S., J.X., K.N.A., G.M.K., and S.S.K. performed experiments; P.K.L., J.S., J.X., K.N.A., G.M.K., S.S.K., C.T.G. and G.E.D. designed experiments, analyzed data, and generated figures; P.K.L., J.S., C.T.G., and G.E.D. wrote the manuscript; all authors reviewed the manuscript. G.E.D. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Supplemental Data

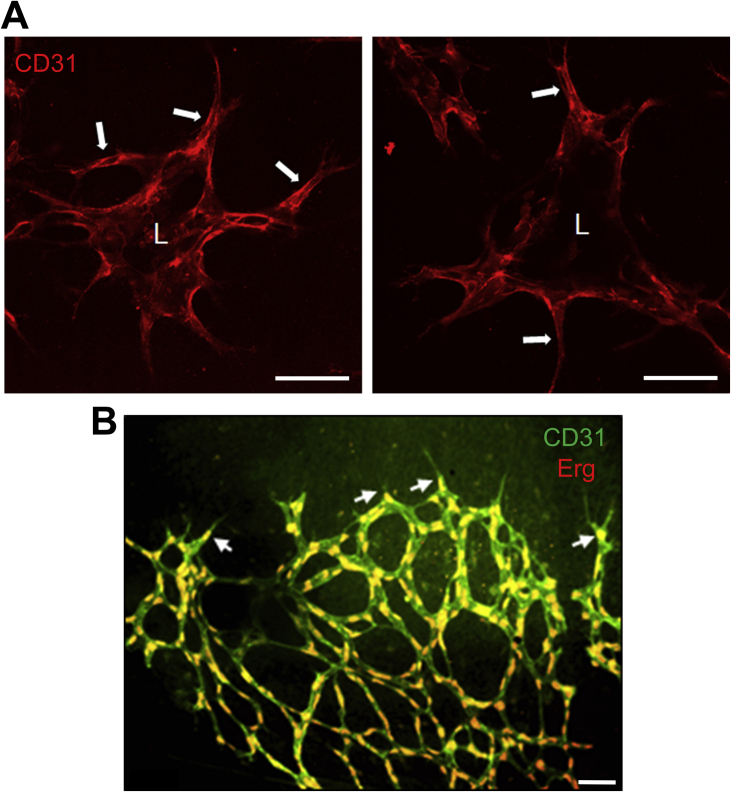

Supplemental Figure S1.

Endothelial cell (EC) aggregate assay system allows for the evaluation of lumen formation and sprouting behavior, and EC tip cell visualization and analysis during mouse retinal angiogenesis. A: EC aggregates were seeded in collagen matrices for 24 hours, and, after fixation, were stained with antibodies directed to CD31. Confocal microscopy reveals a central luminal compartment (L) as well as EC sprouts and tip cells (arrows). B: Retinal vessels were immunostained with anti–platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 (green) for visualization of endothelial cell membranes and with anti-Ets–related gene (Erg) (red) for visualization of endothelial cell nuclei. Tip cells (arrows) were distinguished in flat-mounted retinas by their localization at the vascular front, their filopodia extensions, and their association with a single nucleus. Scale bars = 100 μm (A and B).

Supplemental Figure S2.

Endothelial cell (EC) sprouting behavior is markedly reduced by the tubulin-modifying drug, paclitaxel. A: ECs were seeded as single cells for 24 hours in the absence or presence of paclitaxel at 100 nmol/L or the drug combination FIST, which stimulates EC lumen formation. FIST consists of forskolin (10 μmol/L), IBMX (100 μmol/L), SB239063 (10 μmol/L), and tubacin (10 μmol/L). Arrows indicate sprouting EC tubes with evident lumens; arrowheads indicate EC rings with circular lumens. B: EC aggregates were treated with the indicated drugs, including the Src family kinase inhibitor, PP2 (5 μmol/L), the Notch pathway inhibitor, DAPT (5 μmol/L), or both and then in the presence or absence of paclitaxel (100 nmol/L). After 24 hours, cultures were fixed, stained, and imaged. White arrowhead indicates aggregate with an open central lumen; black arrowhead indicates aggregate with no sprouts or lumen. Scale bars: 100 μm (A and B, left four panels); 200 μm (B, right four panels).

Supplemental Figure S3.

The endothelial cell (EC) sprouting inhibitory influence of tubulin-modifying agents does not correlate with inhibitory influences on either EC survival or proliferation over a 24-hour time frame. A: ECs were seeded on top of collagen gels and allowed to sprout downward for 24 hours in the presence or absence of the indicated tubulin-modifying drugs. Cultures were fixed with 3% glutaraldehyde and stained with 0.1% toluidine blue. Left column: Top-down views of the EC monolayers. Right column: Cross-sectional side views of collagen gels. Arrowheads indicate the monolayer surface, whereas arrows indicate tip cell sprouts. B: ECs were seeded on top of collagen gels and allowed to sprout for 24 hours in the absence or presence of the indicated drugs at 10 nmol/L. Lysates were collected from triplicate cultures at 1-, 4-, 8-, and 24-hour time points. Western blot analyses were performed using the indicated antibodies. n = 3 for all conditions (A). Scale bars: 100 μm (A, left column); 500 μm (A, right column). p-HH3 indicates phospho-histone H3; T.HH3, total histone H3.

Supplemental Figure S4.

Key role for microtubules in controlling the branched pattern of forming endothelial cell tube networks. Paclitaxel (10 nmol/L) and vinblastine (100 nmol/L) were added in the indicated time intervals versus control-treated cultures. At the end of the 24-hour treatment period, cultures were fixed, stained, and imaged. Arrows indicate the marked tube collapse and regression caused by 100 nmol/L vinblastine. Scale bars = 200 μm.

Supplemental Figure S5.

Analysis of tubulin post-translational modifications following treatment with paclitaxel and vinblastine: Reduced tubulin acetylation correlates with the ability of high-dose vinblastine to block endothelial cell (EC) lumen formation. A: EC aggregates were treated with the indicated varying doses of paclitaxel and vinblastine, and after 24 hours, were fixed, stained, and quantitated for EC luminal area. B: The cultures in A were lysed in sample buffer, and Western blot analyses were performed to assess post-translational modifications of tubulin. ∗∗P < 0.01 versus control. Acetyl Tub, acetylated tubulin; Detyr Tub, detyrosinated tubulin.

Supplemental Figure S6.

Blockade of endothelial cell (EC) sprouting behavior using tubulin-modifying agents increases tubulin acetylation, which is concentrated in a subapical region in ECs forming lumens. EC aggregates were suspended in three-dimensional collagen gels and were either left untreated or treated with the indicated tubulin-modifying drugs (each added at 10 nmol/L). They were allowed to undergo morphogenesis for 24 hours before fixing them with 3% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline. Cultures were immunostained with antibodies directed to acetylated tubulin (Acetyl Tub) or were stained with phalloidin conjugated with AlexaFluor 488 to stain for filamentous actin (F-Actin). White arrowheads indicate subapical acetylated tubulin labeling; open arrowheads, the predominant basal distribution of F-Actin staining; and arrows, tip cell sprouts. Scale bars: 100 μm (top panels); 25 μm (bottom panels). L, EC luminal space.

Endothelial cell (EC) aggregate assay under control conditions, where marked EC sprouting and aggregate lumen formation are observed. The video is shown over a 24-hour period at 9.6 frames per second.

Separate endothelial cell (EC) aggregate assay under control conditions, where marked EC sprouting and aggregate lumen formation are observed. The video is shown over a 24-hour period at 9.6 frames per second.

Endothelial cell (EC) aggregate assay following the addition of paclitaxel at 100 nmol/L, showing EC aggregate lumen formation and expansion, but no EC sprouting behavior. Note that initial filopodia-like processes are retracted over the time frame. The video is shown over a 24-hour period at 9.6 frames per second.

Separate endothelial cell (EC) aggregate assay following the addition of paclitaxel at 100 nmol/L, showing EC aggregate lumen formation and expansion, but no EC sprouting behavior. Note that initial filopodia-like processes are retracted over the time frame. The video is shown over a 24-hour period at 9.6 frames per second.

Endothelial cell (EC) aggregate assay following the addition of docetaxel at 100 nmol/L, showing EC aggregate lumen formation and expansion, but no EC sprouting behavior. Note that initial filopodia-like processes are retracted over the time frame. The video is shown over a 24-hour period at 9.6 frames per second.

Endothelial cell (EC) aggregate assay following the addition of docetaxel at 10 nmol/L, showing EC aggregate lumen formation and expansion, but no EC sprouting behavior. Note that initial filopodia-like processes are retracted, but taking longer than that observed with 100 nmol/L docetaxel over the time frame. The video is shown over a 24-hour period at 9.6 frames per second.

Endothelial cell (EC) aggregate assay following the addition of epothilone B at 100 nmol/L, showing EC aggregate lumen formation and expansion, but no EC sprouting behavior. Note that initial filopodia-like processes are retracted, whereas the multicellular lumen expands without EC sprouting or tip cells. The video is shown over a 24-hour period at 7.6 frames per second.

Endothelial cell (EC) aggregate assay following the addition of epothilone B at 10 nmol/L, showing EC aggregate lumen formation and expansion, but no EC sprouting behavior. Note that initial filopodia-like processes are retracted, whereas the multicellular lumen expands without EC sprouting. The video is shown over a 24-hour period at 7.6 frames per second.

Endothelial cell (EC) aggregate assay following the addition of epothilone B at 1 nmol/L, showing EC aggregate lumen formation and expansion, with minimal EC sprouting behavior that is not sustained. Note that initial filopodia-like processes are retracted, whereas occasional tip cells begin to emerge, but then move back into the aggregate. Overall, the multicellular lumens expand with minimal EC sprouting behavior that is not sustained over time. The video is shown over a 24-hour period at 7.6 frames per second.

Endothelial cell (EC) aggregate assay following the addition of ixabepilone at 100 nmol/L, showing EC aggregate lumen formation and expansion, but no EC sprouting behavior. Note that initial filopodia-like processes are retracted, whereas the multicellular lumen expands without EC sprouting or tip cells. The video is shown over a 24-hour period at 7.6 frames per second.

Endothelial cell (EC) aggregate assay following the addition of ixabepilone at 10 nmol/L, showing EC aggregate lumen formation and expansion, but no EC sprouting behavior. Note that initial filopodia-like processes are retracted, whereas the multicellular lumen expands with minimal EC sprouting behavior that can be sustained. The video is shown over a 24-hour period at 7.6 frames per second.

Endothelial cell (EC) aggregate assay following the addition of ixabepilone at 1 nmol/L, showing EC aggregate lumen formation and expansion, with minimal EC sprouting behavior that is not sustained. Note that initial filopodia-like processes are retracted, whereas occasional tip cells begin to emerge, but then move back into the aggregate. Overall, the multicellular lumens expand with minimal EC sprouting behavior that is not sustained over time. The video is shown over a 24-hour period at 7.6 frames per second.

Endothelial cell (EC) aggregate assay under control conditions, where marked EC sprouting and aggregate lumen formation are observed. Marked EC sprouting is observed, which is sustained, and lumen formation is observed in the EC aggregate, but is also observed in some sprouts. The video is shown over a 24-hour period at 7.6 frames per second.

Endothelial cell (EC) aggregate assay following addition of the matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibitor, GM6001, demonstrating complete blockade of both EC aggregate lumen and EC sprouting behavior. GM6001 was added at 10 μmol/L. Note that filopodia-like processes are observed throughout the time frame. The video is shown over a 24-hour period at 9.6 frames per second.

Endothelial cell (EC) aggregate assay following addition of vinblastine at 100 nmol/L, showing combined blockade of EC sprouting behavior and EC aggregate lumen formation. Note the lack of EC sprouting and lumen formation in the aggregates shown. The video is shown over a 24-hour period at 7.6 frames per second.

Endothelial cell (EC) aggregate assay following addition of vinblastine at 10 nmol/L, showing EC aggregate lumen formation and expansion, but no EC sprouting behavior. Note that initial filopodia-like processes are retracted over the time frame, and EC aggregate lumen expansion is observed with no EC sprouting. The video is shown over a 24-hour period at 7.6 frames per second.

Control endothelial cell (EC) aggregate assay, where marked EC sprouting with invading tip cells and aggregate lumen formation are observed. The video is shown over a 24-hour period at 7.6 frames per second.

Endothelial cell (EC) aggregate assay following addition of the Src inhibitor, PP2, showing marked increases in EC sprouting behavior and invading EC tip cells. PP2 was added at 5 μmol/L. The video is shown over a 24-hour period at 9.6 frames per second.

Endothelial cell (EC) aggregate assay following addition of the Notch signaling inhibitor, DBZ, showing increases in EC sprouting behavior and invading EC tip cells. DBZ was added at 5 μmol/L. The video is shown over a 24-hours period at 9.6 frames per second.

Endothelial cell (EC) aggregate assay following combined blockade of Src and Notch signaling using PP2 and DBZ, showing marked increases in EC sprouting behavior with invading EC tip cells and reduced EC aggregate lumen formation. PP2 and DBZ were both added at 5 μmol/L. The video is shown over a 24-hour period at 9.6 frames per second.

References

- 1.Adams R.H., Alitalo K. Molecular regulation of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:464–478. doi: 10.1038/nrm2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horowitz A., Simons M. Branching morphogenesis. Circ Res. 2008;103:784–795. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.181818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carmeliet P., De Smet F., Loges S., Mazzone M. Branching morphogenesis and antiangiogenesis candidates: tip cells lead the way. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6:315–326. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iruela-Arispe M.L., Davis G.E. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of vascular lumen formation. Dev Cell. 2009;16:222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Majesky M.W. Vascular development. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38:e17–e24. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.310223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meadows S.M., Cleaver O. Vascular patterning: coordinated signals keep blood vessels on track. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2015;32:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Red-Horse K., Siekmann A.F. Veins and arteries build hierarchical branching patterns differently: bottom-up versus top-down. Bioessays. 2019;41:e1800198. doi: 10.1002/bies.201800198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simons M., Eichmann A. Molecular controls of arterial morphogenesis. Circ Res. 2015;116:1712–1724. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.302953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herbert S.P., Stainier D.Y. Molecular control of endothelial cell behaviour during blood vessel morphogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:551–564. doi: 10.1038/nrm3176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang J., Hirschi K. Molecular regulation of arteriovenous endothelial cell specification. F1000Res. 2019;8 doi: 10.12688/f1000research.16701.1. F1000 Faculty Rev-1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis G.E., Norden P.R., Bowers S.L. Molecular control of capillary morphogenesis and maturation by recognition and remodeling of the extracellular matrix: functional roles of endothelial cells and pericytes in health and disease. Connect Tissue Res. 2015;56:392–402. doi: 10.3109/03008207.2015.1066781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sacharidou A., Stratman A.N., Davis G.E. Molecular mechanisms controlling vascular lumen formation in three-dimensional extracellular matrices. Cells Tissues Organs. 2012;195:122–143. doi: 10.1159/000331410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stratman A.N., Saunders W.B., Sacharidou A., Koh W., Fisher K.E., Zawieja D.C., Davis M.J., Davis G.E. Endothelial cell lumen and vascular guidance tunnel formation requires MT1-MMP-dependent proteolysis in 3-dimensional collagen matrices. Blood. 2009;114:237–247. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-196451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bayless K.J., Davis G.E. Sphingosine-1-phosphate markedly induces matrix metalloproteinase and integrin-dependent human endothelial cell invasion and lumen formation in three-dimensional collagen and fibrin matrices. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;312:903–913. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duran C.L., Howell D.W., Dave J.M., Smith R.L., Torrie M.E., Essner J.J., Bayless K.J. Molecular regulation of sprouting angiogenesis. Compr Physiol. 2017;8:153–235. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c160048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holderfield M.T., Hughes C.C. Crosstalk between vascular endothelial growth factor, notch, and transforming growth factor-beta in vascular morphogenesis. Circ Res. 2008;102:637–652. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.167171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larrivee B., Freitas C., Suchting S., Brunet I., Eichmann A. Guidance of vascular development: lessons from the nervous system. Circ Res. 2009;104:428–441. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.188144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salvador J., Davis G.E. Evaluation and characterization of endothelial cell invasion and sprouting behavior. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1846:249–259. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8712-2_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tung J.J., Tattersall I.W., Kitajewski J. Tips, stalks, tubes: notch-mediated cell fate determination and mechanisms of tubulogenesis during angiogenesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a006601. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herbert S.P., Cheung J.Y., Stainier D.Y. Determination of endothelial stalk versus tip cell potential during angiogenesis by H2.0-like homeobox-1. Curr Biol. 2012;22:1789–1794. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]