Abstract

Objectives

This study is set up to explore the factors associated with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) testing among women and men in Nepal.

Study design

Nepal Demographic and Health Survey, 2016 adopts a cross-sectional design.

Setting

Nepal.

Participants

Women and men of age 15–49 years.

Primary outcome measures

Our primary outcome was ever tested for HIV. We used multivariable analysis at a 95% level of significance to measure the effect in outcome variables.

Results

About one in 10 women (10.8%) and one in five men (20.5%) ever tested for HIV. Women who had media exposure at least once a week ((adjusted odds ratio (aOR)=2.8; 95% CI: 1.4 to 5.3) were more likely to get tested for HIV compared with those who had no media exposure at all. Similarly, those who had their recent delivery in the health facility (aOR=3.9; 95% CI: 2.4 to 6.3) were more likely to get tests for HIV compared with those delivered elsewhere. Likewise, among men, compared with adolescents (15–19 years), those from older age groups were more likely to get tested for HIV. Compared with no education, secondary (aOR=2.3; 95% CI: 1.4 to 3.6) and higher education (aOR=1.7; 95% CI: 1.0 to 2.8) had higher odds of getting tested for HIV. Similarly, wealth quintiles in richer and richest groups were more likely to get tested for HIV compared with the poorest quintile. Other characteristics like media exposure, paid sex and 2+ sexual partners were positively associated with being tested for HIV.

Conclusions

HIV testing is not widespread and more men than women are accessing HIV services. More than two-thirds of women who delivered at health facilities never tested for HIV. It is imperative to reach out to people engaging in risky sexual behaviour, people with lower educational attainment, and those in the lower wealth quintile for achieving 95–95–95 targets by 2030.

Keywords: HIV & AIDS, public health, epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This analysis is based on the most recent nationally representative survey.

One of the major limitations of the cross-sectional study is that the causal association could not be established.

Behavioural desirability bias might have some effect on under reporting of sexual behaviours.

Introduction

Globally, Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) is a public health issue with a disproportionate distribution of the epidemics.1 Worldwide 37.7 million (30.2–45.1 million) people are estimated to have HIV. As of 2020, of all estimated people living with HIV (PLHIV), 84% (67% to >98%) knew their status, 73% (56%–88%) were accessing treatment and 66% (53%–79%) were virally suppressed in 2020.2 The Joint United Nations Program on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS) has a global treatment goals of 90–90–90 by 2020 and Nepal has also committed to the global goal. The treatment goal of 90–90–90 aims that 90% of all PLHIV will know their HIV status, 90% of all people with diagnosed HIV infection will receive sustained antiretroviral therapy (ART) and 90% of all people receiving ART will achieve viral suppression.3 As part of sustainable development goals (SDGs), UNAIDS aims to reach 95–95–95 targets by 2030 for epidemic control. The achievement of these targets is largely based on the effective, efficient and targeted coverage and uptake of HIV testing and counselling (HTC) with innovative approaches. Nepal commits to this global goal as set out in the National HIV Strategic Plan 2016–2021.4

Nepal is steadily facing a concentrated HIV epidemic among certain key populations (KPs) such as people who inject drugs, men who have sex with men (MSM)/male sex workers and transgender people in selected epidemic clusters. Nepal’s HIV estimation undertaken in 2019 shows that approximately 29 503 PLHIV are in Nepal, with an adult prevalence rate of 0.13%.5 In Nepal, about 22% of the estimated PLHIV do not know their HIV status. Hence, it is crucial to scale up HTC service to subgroups and among people with the highest need through innovative approaches to attain a global treatment goal of 90–90–90 by 2020 as knowing one’s HIV status is the entry point for HIV treatment, care, support and viral suppression and ending AIDS by 2030.

HTC is the first step and gateway to HIV diagnosis, treatment and prevention of new infections. HTC prevents transmission of HIV by combining tailored counselling with understanding of one’s HIV status, and to persuade people to change their behaviours.6 As an important and cost-effective HIV prevention strategy, HTC services have been widely promoted in developing countries, as part of their primary healthcare package.7 8

Few authors in past have examined the correlates of HIV testing in Nepal. Some of the reported factors that affect HIV testing are age, knowledge, non-use of condom and sociocultural factors such as physical assault, experience of forced sex, stigma and discrimination.9–11 However, either these studies used the previous round of Nepal Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) data set11 or were limited to certain geographical regions9 or KPs10 and lacked population level estimates of HIV testing and its correlates. Therefore, it is imperative to conduct further analysis to explore the utilisation of HTC among the general population with most recent data. Additionally, this analysis will also be useful in recommending strategies to improve the utilisation of HTC services in Nepal.

Methods

Data sources

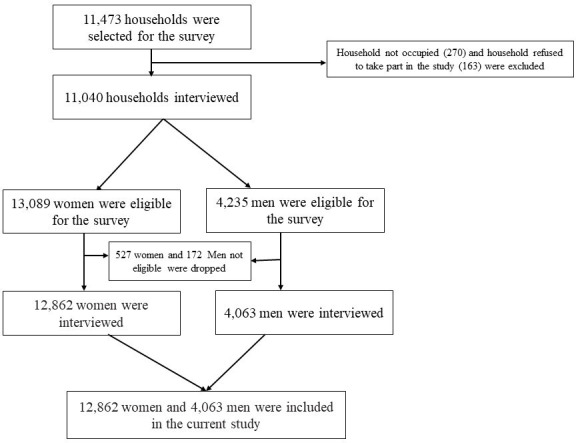

We used data from the recent NDHS conducted in 2016, a nationally representative cross-sectional study. The survey was implemented by New ERA under the leadership of the Ministry of Health and Population, with technical support from the United States Agency for International Development’s demographic and health survey programme. Personal interviews of eligible women and men aged 15–49 years in the sampled households were conducted using structured questionnaires. This study used data collected through two of six questionnaires administered, that is, the woman’s questionnaire and the man’s questionnaire. The woman’s questionnaire was administered to all women aged 15–49 years and, included topics related to background characteristics, reproductive history and child mortality, family planning methods, fertility preferences, delivery care, child health, women’s work, husband’s characteristics, domestic violence, HIV and AIDS and other health issues. Similarly, man’s questionnaire was administered to all men aged 15–49 years in the subsample of households selected for the male survey. The man’s questionnaire collected information that was similar to the woman’s questionnaire, although it was shorter because it did not include a detailed reproductive history or questions on maternal and child health. A total of 12 862 women and 4063 men from 11 040 households were interviewed in the survey (figure 1). The survey involved the use of a three-stage stratified sampling technique and stratification was done by separating each province into urban and rural areas, that is, stratified and selected in two stages in rural areas and three stages in urban areas. Details of survey methodology and sampling procedure can be found in the final report published elsewhere.12

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing the sampling of study.

Definition of variable

The outcome variable for the study was ‘ever been HIV-tested’, based on a question: ‘I don’t want to know the results, but have you ever been tested for HIV?’ The indicator was defined as having accessed HIV testing services at least once in their lifetime prior to this survey. This question was asked to both women and men individually.

The independent variables like age, ethnicity, education, place of residence, province, wealth quintile, marital status, occupation, comprehensive knowledge on HIV, HIV discriminatory behaviour, media exposure, recent sexual activity, ever paid for sex, knowledge for treatment for HIV, age at first sexual intercourse, number of lifetime sexual partners are included for both sexes. While variables like ever experienced sexual violence, received all four antenatal care (ANC), partner’s education level and place of delivery are included for the analysis of women only. The list of the variables and their operational definitions are provided in the online supplemental table 1.

bmjopen-2021-049415supp001.pdf (131.8KB, pdf)

Data analysis

Frequencies and percentages were calculated for women and men separately. Chi-square (χ2) test was used to show the association of ever tested HIV and other covariates. Bivariable and multivariable binary logistic regression analyses were used to obtain the adjusted effects of ever tested HIV for both men and women separately. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratio (ORs) were presented in the results, which express the magnitude in relation to the reference category in the odds (OR >1.00 or OR <1.00) of the variables of interest occurring for a given value of the explanatory variable. Level of significance was set at p value <0.05 and a 95% confidence interval (CI) was used for the statistical significance of the results. Multicollinearity of the independent variable was checked before running multivariate models. We used sampling weights (provided in datasets) separately for women and men to adjust for variations in the selection probabilities and interviews. The ‘svyset’ command was used in weighting the data and to account for complex survey design and to provide unbiased estimate. Data analysis was conducted with STATA V.15.0 (Stata Corp).

Patient and public involvement statement

Patients and publics were not involved in this study. We analysed the publicly accessible secondary data.

Results

Background characteristics

This analysis is limited to 12 862 women and 4063 men among the total interviewed in NDHS 2016. The background characteristics and proportion of ever tested HIV by women and men is presented below.

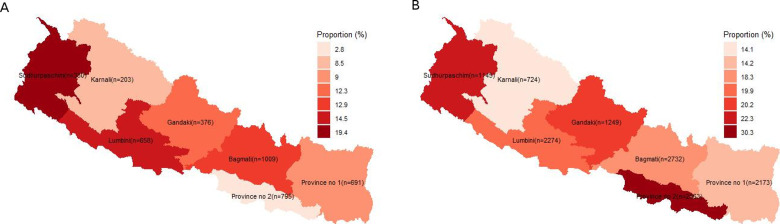

Women

The mean age of the women aged 15–49 years was 29 years. Most of them were Janajatis (35.8%) followed by Hill Brahmin/Chhetri (30%) and less than 20% were Dalit/muslim/other (17.7%) and Terai caste (16.5%). More than one-third (35.1%) of the women had secondary level education whereas 33.3% did not have any formal education. Less than one-fifth (16.7%) had a primary education and 14.9% had higher education. The majority of women (62.8%) resided in urban areas. Nearly one-fifth of the women lived in Bagmati province (21.2%) followed by Province no. 2 (19.9%) (figure 2). Most of the women (76.8%) were married/living together and about half (46.7%) of women were engaged in agricultural activities as main occupation. Only about one-third (32.4%) of the women had any media exposure of at least once a week (table 1).

Figure 2.

Proportion of ever tested HIV by men (A), by women (B).

Table 1.

Proportion of HIV testing by sociodemographic characteristics among women and men

| Characteristics | Women | Men | ||

| Total, n (%) | Ever tested HIV (%) | Total, n (%) | Ever tested HIV (%) | |

| 12 862 | 10.8 | 4063 | 20.5 | |

| Age | ||||

| 15–19 | 2598 (20.2) | 4.0*** | 931 (22.9) | 5.3*** |

| 20–24 | 2251 (17.5) | 14.5 | 649 (16.0) | 20.1 |

| 25–29 | 2135 (16.6) | 19.1 | 525 (12.9) | 31.4 |

| 30–39 | 3378 (26.3) | 12.0 | 1079 (26.5) | 29.9 |

| 40–49 | 2500 (19.4) | 5.6 | 879 (21.6) | 19.0 |

| Mean (SD) | 29.3 (9.7) | 29.6 (10.2) | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hill Brahmin/Chhetri | 3855 (30.0) | 16.0*** | 1144 (28.2) | 20.4 |

| Terai caste | 2126 (16.5) | 4.1 | 683 (16.8) | 24.8 |

| Janajatis | 4600 (35.8) | 11.1 | 1546 (38.1) | 18.4 |

| Dalit/muslim/other | 2281 (17.7) | 7.5 | 689 (17.0) | 21.1 |

| Education | ||||

| No education | 4281 (33.3) | 5.2*** | 391 (9.6) | 13.1* |

| Primary | 2150 (16.7) | 8.9 | 789 (19.4) | 18.6 |

| Secondary | 4516 (35.1) | 11.5 | 1990 (49.0) | 22.1 |

| Higher | 1915 (14.9) | 23.5 | 893 (22.0) | 22.0 |

| Place of residence | ||||

| Urban | 8072 (62.8) | 12.3** | 2647 (65.2) | 20.7 |

| Rural | 4790 (37.2) | 8.2 | 1416 (34.8) | 20.2 |

| Wealth quintile | ||||

| Poorest | 2176 (16.9) | 8.2*** | 623 (15.3) | 14.1*** |

| Poorer | 2525 (19.6) | 8.3 | 706 (17.4) | 13.4 |

| Middle | 2594 (20.2) | 8.0 | 758 (18.7) | 22.0 |

| Richer | 2765 (21.5) | 10.1 | 982 (24.2) | 24.9 |

| Richest | 2801 (21.8) | 18.3 | 994 (24.5) | 24.0 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Never married | 2669 (20.7) | 2.9 | 1355 (33.4) | 9.1*** |

| Married/living together | 9875 (76.8) | 12.9 | 2675 (65.8) | 26.3 |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 318 (2.5) | 9.7 | 33 (0.8) | 20.7 |

| Occupation | ||||

| Did not work | 4259 (33.1) | 10.5*** | 581 (14.3) | 12.2*** |

| Agricultural | 6011 (46.7) | 8.6 | 1144 (28.2) | 18.2 |

| Professional/clerical | 659 (5.1) | 22.4 | 547 (13.5) | 23.7 |

| Manual labour | 1933 (15.0) | 14.1 | 1786 (44.0) | 23.7 |

| Comprehensive knowledge on HIV | ||||

| No | 10 357 (80.5) | 8.6*** | 2921 (71.9) | 18.6*** |

| Yes | 2505 (19.5) | 19.5 | 1142 (28.1) | 25.3 |

| HIV discriminatory behaviour | (n=10 348) | (n=3965) | ||

| No | 6214 (60.0) | 16.2 | 2663 (67.2) | 21.4 |

| Yes | 4135 (40.0) | 9.2 | 1302 (32.8) | 20.2 |

| Any media exposure | ||||

| Not at all | 2062 (16.0) | 4.1*** | 255 (6.3) | 11.5** |

| At least once a week | 4166 (32.4) | 11.7 | 1144 (28.1) | 24.1 |

| Less than once a week | 6634 (51.6) | 12.3 | 2664 (65.6) | 19.8 |

| Recent risky sexual activity | ||||

| No | 12 846 (99.9) | 10.8 | 3709 (91.3) | 20.4 |

| Yes | 16 (0.1) | 22.4 | 354 (8.7) | 22.0 |

| Ever paid for sex | ||||

| No | 12 861 (99.9) | 10.8 | 3911 (96.3) | 19.6*** |

| Yes | 1 (0.01) | 0.0 | 152 (3.7) | 44.7 |

| Knowledge for treatment for HIV | (n=10 348) | (n=3965) | ||

| No/don’t know | 5390 (52.1) | 12.8 | 2729 (68.8) | 20.2 |

| Yes | 4959 (47.9) | 14.0 | 1236 (31.2) | 22.8 |

| Age at first sexual intercourse | (n=10 157) | (n=3083) | ||

| <15 years | 1161 (11.4) | 8.2*** | 136 (4.4) | 21.1 |

| 15–19 years | 6574 (64.7) | 11.6 | 1515 (49.1) | 24.4 |

| 20–24 years | 2052 (20.2) | 19.5 | 1022 (33.1) | 25.2 |

| 25 and above years | 370 (3.7) | 22.7 | 410 (13.3) | 28.5 |

| Mean (SD) | 14.0 (7.7) | 15.1 (9.1) | ||

| Number of lifetime sexual partners | (n=10 207) | (n=3097) | ||

| 1 | 9877 (96.8) | 12.9 | 1857 (60.0) | 22.1** |

| 2+ | 330 (3.2) | 12.0 | 1240 (40.0) | 29.4 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.04 (0.46) | 2.36 (4.83) | ||

***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05 (χ2 test).

Men

The mean age of the men aged 15–49 years was 29.6 years. Similar to women, most of them were also Janajatis (38.1%) followed by Hill Brahmin/Chhetri (28.2%). About half of the men had higher education while about 10% did not have any formal education. Nearly two-third (65.2%) lived in urban areas and about one-fourth lived in Bagmati Province (24.8%). About two-third of the men were married and more than two-fifth were engaged in manual labour. The media exposure of at least once a week among men is lower than that of women (table 1)

HIV and sexual behaviors among women and men

Comprehensive knowledge among women and men about HIV is not widespread, that is, about 20% of women and 28% of men have comprehensive knowledge on HIV. Two-fifth (40%) of women and about one-third (32.8%) of men expressed discriminatory attitudes towards PLHIV. Less than 1% of women (0.1%) and nearly 10% of men (8.7%) had recent sexual activity, that is, having sexual intercourse with a person that is not their spouse and does not live with them in the past 12 months. A negligible per cent of women and less than 5% of men (3.7%) had ever paid for sexual intercourse. The knowledge regarding treatment for HIV is higher among women (48%) than men (31%). The mean age of first sexual intercourse among women and men is 14 years and 15 years, respectively. Less than 5% of women (3.2%) and 40% (4.8 in average) of men reported having multiple sexual partners in their lifetime (table 1).

Proportion of HIV testing and the pattern by different characteristics among women and men

About one in 10 women (10.8%) and one in five men (20.5%) ever tested for HIV. HIV testing differed significantly by age, ethnicity, education, place of residence, province, wealth quintile, occupation, comprehensive knowledge on HIV, media exposure, age at first sexual intercourse, received all four ANC, partner’s education level and place of delivery among women and among men, by age, education, province, wealth quintile, marital status, occupation, comprehensive knowledge on HIV, media exposure, ever paid for sex and number of lifetime partners (table 1, figure 2).

Characteristics of women related to maternal, sexual violence and others

Around 7.8% of women aged 15–49 years ever experienced sexual violence. More than two-fifth of their partners achieved secondary education (44%) followed by primary (21.9%) and higher education (18.1%). Nearly 60% received all four focused ANC visits and 63.5% of them delivered their most recent baby in the health facility (table 2).

Table 2.

Proportion of HIV testing by characteristics related to violence among women, pregnancy and delivery-related services

| Characteristics | Women | |

| Total, n (%) | Ever tested HIV (%) | |

| Ever experienced sexual violence | (n=4421) | |

| Not experienced | 4075 (92.2) | 11.9 |

| Experienced | 346 (7.8) | 10.1 |

| Received all four ANC | (n=3762) | |

| Not received | 1550 (41.2) | 11.2*** |

| Received | 2212 (58.8) | 28.0 |

| Partner’s education level | (n=9852) | |

| No education | 1575 (16.0) | 4.1*** |

| Primary | 2158 (21.9) | 7.8 |

| Secondary | 4337 (44.0) | 13.7 |

| Higher | 1782 (18.1) | 25.2 |

| Place of recent delivery | (n=3997) | |

| Elsewhere | 1459 (36.5) | 6.3*** |

| Health facility | 2539 (63.5) | 28.2 |

*** p<0.001, ** p<0.01, * p<0.05 (t-statistic).

ANC, antenatal care.

Factors associated with HIV testing among women and men

Table 3 presents the unadjusted and adjusted ORs from the binary logistic regression analysis that illustrates the odds of women and men who had ever tested for HIV. An adjusted model was used to adjust the effects of independent characteristics. All the variables were used in the multivariable model but only the variable that turned significant in the adjusted analysis are presented in the table. The result with all the variables is provided in the online supplemental table 2.

Table 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted OR of HIV testing among women and men

| Characteristics | Women | Men | ||

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

| Age | ||||

| 15–19 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| 20–24 | 4.0*** (3.1 to 5.2) | 1.4 (0.6 to 3.2) | 4.5*** (3.0 to 6.7) | 3.9*** (2.1 to 7.2) |

| 25–29 | 5.6*** (4.3 to 7.3) | 1.7 (0.8 to 3.6) | 8.2** (5.1 to 13.2) | 6.4*** (3.3 to 12.1) |

| 30–39 | 3.2*** (2.5 to 4.2) | 1.9 (0.8 to 4.5) | 7.6*** (5.1 to 11.3) | 5.5*** (3.0 to 10.2) |

| 40–49 | 1.4 (0.9 to 1.9) | 0.2 (0.01 to 1.9) | 4.2*** (2.6 to 6.6) | 3.0*** (1.6 to 5.7) |

| Education | ||||

| No education | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Primary | 1.8*** (1.4 to 2.3) | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.6) | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.3) | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.3) |

| Secondary | 2.3*** (1.9 to 2.9) | 1.4 (0.7 to 2.6) | 1.9** (1.2 to 2.8) | 2.3*** (1.4 to 3.6) |

| Higher | 5.6*** (4.4 to 7.0) | 2.1 (0.9 to 4.2) | 1.9** (1.2 to 2.9) | 1.7* (1.0 to 2.8) |

| Province | ||||

| Province no. 1 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Province no. 2 | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.4) | 0.8 (0.3 to 1.8) | 2.6*** (1.7 to 4.1) | 3.5*** (2.0 to 6.2) |

| Bagmati | 1.5* (1.0 to 2.2) | 2.0* (1.1 to 3.8) | 1.3 (0.9 to 2.0) | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.8) |

| Gandaki | 1.4 (0.9 to 2.0) | 1.4 (0.8 to 2.8) | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.4) | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.4) |

| Lumbini | 1.7* (1.1 to 2.6) | 2.3* (1.1 to 4.8) | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.4) | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.5) |

| Karnali | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.4) | 1.9 (0.9 to 4.0) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.6) | 1.1 (0.6 to 1.8) |

| Sudurpaschim | 2.4*** (1.6 to 3.6) | 3.3** (1.5 to 7.0) | 1.7* (1.1 to 2.7) | 1.6* (1.0 to 2.4) |

| Wealth quintile | ||||

| Poorest | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Poorer | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.3) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.7) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.3) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.3) |

| Middle | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.3) | 1.0 (0.5 to 1.9) | 1.7** (1.2 to 2.5) | 1.3 (0.9 to 2.0) |

| Richer | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.7) | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.6) | 2.0*** (1.4 to 2.9) | 1.6* (1.1 to 2.4) |

| Richest | 2.5*** (1.8 to 3.4) | 1.5 (0.7 to 3.1) | 1.9*** (1.3 to 2.8) | 1.7* (1.1 to 2.6) |

| Comprehensive knowledge on HIV | ||||

| No | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 2.6*** (2.2 to 2.9) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.5) | 1.5*** (1.2 to 1.8) | 1.4* (1.1 to 1.8) |

| Any media exposure | ||||

| Not at all | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| At least once a week | 3.1*** (2.3 to 4.1) | 2.8** (1.4 to 5.3) | 2.4*** (1.5 to 3.9) | 1.7* (1.0 to 3.1) |

| Less than once a week | 3.3*** (2.5 to 4.3) | 1.4 (0.7 to 2.6) | 1.9** (1.2 to 3.0) | 1.3 (0.8 to 2.3) |

| Ever paid for sex | ||||

| No | – | – | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | – | – | 3.3*** (2.1 to 5.2) | 2.1** (1.3 to 3.4) |

| Number of lifetime sexual partners | ||||

| 1 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| 2+ | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.5) | 0.9 (0.2 to 3.0) | 1.5** (1.2 to 1.8) | 1.6*** (1.2 to 2.0) |

| Place of recent delivery | ||||

| Elsewhere | Ref. | Ref. | – | – |

| Health facility | 5.7*** (4.9 to 6.5) | 3.9*** (2.4 to 6.3) | ||

***P<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05 (t-statistic).

Women from Bagmati province (adjusted odds ratio (aOR)=2.0; 95% CI=1.1 to 3.8), Lumbini province (aOR=2.3; 95% CI=1.1 to 4.8) and Sudurpaschim province (aOR=3.3, 95% CI=1.5 to 7.0) were more likely to have tested for HIV compared with the women from Province no. 1. Women who had a media exposure at least once a week had 2.8 times (aOR=2.8; 95% CI=1.4 to 5.3) higher odds of having HIV testing compared with those who had not been exposed to media at all. Those women who had their recent delivery at a health facility were more likely (aOR=3.9; 95% CI=2.4 to 6.3) to have HIV testing compared with those who had delivered their recent babies somewhere other than the health facility (table 3).

Men aged 20 years and above were more likely to have HIV testing compared with those between age 15 and 19 years of age. Similarly, compared with no education, men with secondary and higher education were more likely to have HIV testing. Men from Province no. 2 (aOR=3.5; 95% CI=2.0 to 6.2) and Sudurpaschim province (aOR=1.6; 95% CI=1.0 to 2.4) had higher odds of having HIV testing compared with the Province no. 1. Men with richer (aOR=1.6; 95% CI=1.1 to 2.4) and richest (aOR=1.6; 95% CI=1.0 to 2.4) quintiles were also more likely to have HIV testing compared with the poorest quintile of wealth. Men who had comprehensive knowledge of HIV had higher odds (aOR=1.4; 95% CI=1.1 to 1.8) of having HIV testing compared with those who do not have a comprehensive knowledge. Similar to the women, men with media exposure at least once a week were more likely (aOR=1.7; 95% CI=1.0 to 3.1) to have HIV testing compared with those who had not been exposed to media at all. Further, men who ever paid for sex (aOR=2.1, 95% CI=1.3 to 3.4) and had 2+ sexual partners (aOR=1.6; 95% CI=1.2 to 2.0) in their lifetime were more likely to have HIV testing compared with the men who had not paid for sex and had only one sex partner, respectively (table 3).

Discussion

More men than woman ever tested for HIV. The findings from this study are in contrast to the testing behaviour in Nairobi,13 where women were more likely to get tested than men. This could be explained partly by men’s engagement in high-risk behaviour and high rate of seasonal migration among male in Nepal;14 high-risk perception and better health-seeking behaviour and access to HTC services. The National HIV Strategic Plan 2016–2021 identifies clients of female sex workers (FSWs), and migrants as high-risk populations and various HIV-related programmes are targeted at improving HIV testing behaviour among migrants.4 In the integrated bio-behavioural surveillance (IBBS) survey conducted among male labour migrants,15 reported practising high-risk sexual behaviour resulting in heightened risk among their spouses. Similarly, IBBS survey conducted among FSWs and MSM and transgender people reported 50% of HIV testing coverage,10 Moreover, IBBS survey among labour migrant and their spouses depicts HTC service utilisation of 18.6% and 35%, respectively.16 17

One of the reasons for more women being tested for HIV in Nairobi is mainly due to the increased testing among women in prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) programmes. In countries such as India18 and Seirra Leone,19 HIV testing was found higher among women who had given birth in the last 5 years and majority of those women who reported testing as part of the ANC services. This reinforces the importance of ANC services for HIV testing among women of reproductive age. Despite the Government of Nepal strategy to expand HIV testing services as part of PMTCT services, not all women who received all four ANC were tested for HIV.

Similarly, other critical area is the HIV services for those surviving sexual violence. Further, women experiencing sexual violence are also being missed from the recommended HIV counselling and testing services; only 10% of total women who reported experiencing sexual violence in the recent years had tested for HIV. It is unclear if they even received post exposure prophylaxis services as per WHO recommendation.20 Our findings suggest the need for additional efforts to promote HIV testing among women who experience sexual violence.

Consistent with the findings of Zambia,21 our study showed health facility delivery is correlated with HIV testing. This provides an opportunity to scale up HIV testing among women as more women are now delivering at heath facility in recent years.22 Special efforts needs to be designed to promote HIV testing as part of ANC and institutional delivery services. Further, expansion of HIV testing facilities is critical as only a quarter of government and 30% of private hospital currently provide HIV testing services.23

Men who were in the age group (20–24 years) were more likely to get tested. Some other studies also reported similar findings.24 25 The potential reason for this age-group to be tested could also be tied with the prime age of migration.11 Education was also found to be a determining factor for HIV testing, the most possible explanation could be higher understanding and awareness about the testing services and its benefits. Higher education was also a determining factor for utilisation of HIV testing in different counties.24–27 In addition to education, HIV-related knowledge was the significant correlates of being tested for HIV among men. This is confirmed by studies conducted in Kenya,28 Canada20 and sub-Saharan Africa.29 As reported in various studies undertaken at the global and regional level,30–33 being in a higher economic quintile was associated with HIV testing. It is to be noted that HIV testing is free in Nepal but higher testing among participants at higher economic quintile may be related to the higher risk behaviour and involvement in risky sex behaviour among these groups.11

HIV testing services varied by provinces23 which is explained by the disproportionate distribution of HIV in the country. Province no. 2 is one of the most affected provinces as it borders India and is one of the provinces with migrants to India.34 Lumbini province and Sudurpaschim province has the highest case finding rate (1.6% and 1.5%, respectively).35 Based on the HIV size estimation, Province no. 2, Lumbini province and Sudurpaschim province have a higher number of migrants living with HIV.36 Major occupation in the province is through labour migration to India. There is evidence of engagement of the migrant population in higher risky behaviours in India.37 This could be linked with the variation of HIV testing among migrant populations in each province. Service availability and readiness is also a key indicator for the HIV testing among men and women. Authors report persistent gaps in staff, guidelines and medicine and commodities for HIV testing and treatment in Nepal which could also potentially impact the HIV service uptake.29 Further comprehensive knowledge on HIV and media exposure was among the determinants for HIV testing, thus, indicating the need to continue or upscale such programme.

The HIV estimates in 2019 show that there are 29 503 PLHIV in the country, however, about only two-third are currently on ART which falls short of the UNAIDS goal of 90–90–90 by 2020.38 It is evident that even the high-risk groups (those having paid sex or those reporting recent sexual behaviour with person other than their spouse or regular partner) are not receiving HIV testing services.39

These findings clearly indicate the need to reach populations in lower economic quintile and illiterate populations as they were less likely to get tested. Considering the KPs such as FSWs or migrants; nearly one-fourth (37%) were illiterate or had no formal schooling.40 HIV testing coverage can be improved with the innovative and targeted approaches including engagement of community lay providers as well as targeting the sexual, injecting or social network partners of PLHIV.38

Our study used the most recent nationally representative data and assessed gender disaggregated HTC service uptake and correlates among general population. Our study has some limitations. This analysis used the data from cross sectional study so that the causal association could not be established. Behavioural desirability bias might have some effect on under reporting of sexual behaviours. The analysis was limited to the available variables included in the NDHS.

Conclusion

HIV testing is not widespread and more men than women are accessing HIV services. More than two-third of women who delivered at health facilities never tested for HIV. HTC services are a critical service for women experiencing sexual violence. However, only 1 in 10 women experiencing sexual based violence received HIV testing. Media exposure and comprehensive knowledge on HIV are critical determinants for HIV testing, therefore, the National HIV programme should focus on strengthening social behaviour change communication interventions, strengthening PMTCT programme. It is imperative to reach out to people engaging in risky sex behaviour, people with lower educational attainment and those in the lower wealth quintile for achieving 95–95–95 targets by 2030 as a part of SDGs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the DHS program for allowing us to get access to the data sets. Thanks to Ms Kate Killberg; a Public Health Professional active in the field of HIV for reviewing and editing this manuscript.

Footnotes

NB, KB and KA contributed equally.

Contributors: NB and KB were involved in the design and conception of the study. KA and NB were involved in the analysis and interpretation of the findings; KA, NB, RT and KB were involved in the write-up of the manuscript. BS supervised, reviewed and edited the manuscript. NB, KB and KA have access to the data and are responsible for the overall content as the guarantor. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Map disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on the map(s) in this article does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. The map(s) are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Data are available in a public, open access repository. The datasets generated during the current study are available from within the Demographic and Health Survey Program repository (https://dhsprogram.com/data/ available-datasets.cfm).

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

NDHS 2016 was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board Nepal Health Research Council and the institutional review board of ICF Macro International. Written consent was obtained from all the participants before interviewing during the survey. We used de-identified data publicly available from the DHS website (http://www.dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm), and thus did not require ethical approval for this study. Permission was obtained from the DHS program to use the data for further analysis.

References

- 1.GBD 2017 HIV collaborators . Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and mortality of HIV, 1980-2017, and forecasts to 2030, for 195 countries and territories: a systematic analysis for the global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors study 2017. Lancet HIV 2019;6:e831–59. 10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30196-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS . Global HIV & AIDS statistics — Fact sheet. Available: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet [Accessed 17 Sep 2021].

- 3.UNAIDS . Global AIDS Update. UNAIDS, 2019. Available: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2019/2019-global-AIDS-update [Accessed 2 Apr 2020].

- 4.Government of Nepal . National HIV Strategic Plan 2016-2021. National Centre for AIDS and STD Control, Ministry of Health, Government of Nepal. Available: https://www.aidsdatahub.org/sites/default/files/resource/nepal-national-hiv-strategic-english-2016-2021-second-edition.pdf

- 5.Government of Nepal . Factsheet 1: HIV Epidemic Update of Nepal 2019. National Centre for AIDS and STD Control, Ministry of Health and Population, Government of Nepal. Available: http://www.ncasc.gov.np/WAD2019/Factsheet2019.pdf

- 6.Denison JA, O'Reilly KR, Schmid GP, et al. HIV voluntary counseling and testing and behavioral risk reduction in developing countries: a meta-analysis, 1990--2005. AIDS Behav 2008;12:363–73. 10.1007/s10461-007-9349-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holtgrave D, McGuire J. Impact of counseling in voluntary counseling and testing programs for persons at risk for or living with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis 2007;45 Suppl 4:S240–3. 10.1086/522544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coovadia HM. Access to voluntary counseling and testing for HIV in developing countries. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2000;918:57–63. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05474.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khatoon S, Budhathoki SS, Bam K, et al. Socio-Demographic characteristics and the utilization of HIV testing and counselling services among the key populations at the Bhutanese refugees camps in eastern Nepal. BMC Res Notes 2018;11:535. 10.1186/s13104-018-3657-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shrestha R, Philip S, Shewade HD, et al. Why don't key populations access HIV testing and counselling centres in Nepal? Findings based on national surveillance survey. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017408. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma B, Nam EW. Role of knowledge, sociodemographic, and behavioral factors on lifetime HIV testing among adult population in Nepal: evidence from a cross-sectional national survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16. 10.3390/ijerph16183311. [Epub ahead of print: 09 09 2019]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ministry of Health, Nepal; New ERA, Nepal; Nepal Health Sector Support Program (NHSSP); and ICF . Nepal health facility survey 2015. Ministry of Health, Nepal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ziraba AK, Madise NJ, Kimani JK, et al. Determinants for HIV testing and counselling in Nairobi urban informal settlements. BMC Public Health 2011;11:663. 10.1186/1471-2458-11-663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bam K, Thapa R, Newman MS, et al. Sexual behavior and condom use among seasonal Dalit migrant laborers to India from far West, Nepal: a qualitative study. PLoS One 2013;8:e74903. 10.1371/journal.pone.0074903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NCASC . Integrated biological and behavioral surveillance (IBBS) survey among male labor migrants in Western and mid to far Western region of Nepal round VI-2017. National centre for AIDS and STD control, Ministry of health and population, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16.NCASC . Integrated biological and behavioral surveillance survey among male labour migrants (MLM) in six eastern districts of Nepal, 2018 round I. Ministry of health and population, National centre for AIDS and STD control, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.NCASC . Integrated biological and behavioral surveillance (IBBS) survey among wives of migrants in four districts of far-western Nepal round III. National centre for AIDS and STD control, Ministry of health and population, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18.International Institute for Population Sciences - IIPS/India, ICF . India national family health survey NFHS-4 2015-16. IIPS and ICF, 2017. Available: http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR339/FR339.pdf

- 19.Brima N, Burns F, Fakoya I, et al. Factors associated with HIV prevalence and HIV testing in Sierra Leone: findings from the 2008 demographic health survey. PLoS One 2015;10:e0137055. 10.1371/journal.pone.0137055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaai S, Bullock S, Burchell AN, et al. Factors that affect HIV testing and counseling services among heterosexuals in Canada and the United Kingdom: an integrated review. Patient Educ Couns 2012;88:4–15. 10.1016/j.pec.2011.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muyunda B, Musonda P, Mee P, et al. Educational attainment as a predictor of HIV testing uptake among women of child-bearing age: analysis of 2014 demographic and health survey in Zambia. Front Public Health 2018;6:192. 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ministry of Health, Nepal; New ERA; and ICF . Nepal demographic and health survey. Ministry of Health, Nepal, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Acharya K, Thapa R, Bhattarai N, et al. Availability and readiness to provide sexually transmitted infections and HIV testing and counselling services in Nepal: evidence from comprehensive health facility survey. BMJ Open 2020;10:e040918. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Narin P, Yamamoto E, Saw YM, et al. Factors associated with HIV testing among the general male population in Cambodia: a secondary data analysis of the demographic health survey in 2005, 2010, and 2014. PLoS One 2019;14:e0219820. 10.1371/journal.pone.0219820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacPhail C, Pettifor A, Moyo W, et al. Factors associated with HIV testing among sexually active South African youth aged 15-24 years. AIDS Care 2009;21:456–67. 10.1080/09540120802282586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghosh P, Arah OA, Talukdar A, et al. Factors associated with HIV infection among Indian women. Int J STD AIDS 2011;22:140–5. 10.1258/ijsa.2010.010127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agegnehu CD, Geremew BM, Sisay MM, et al. Determinants of comprehensive knowledge of HIV/AIDS among reproductive age (15-49 years) women in Ethiopia: further analysis of 2016 Ethiopian demographic and health survey. AIDS Res Ther 2020;17:51. 10.1186/s12981-020-00305-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nall A, Chenneville T, Rodriguez LM, et al. Factors affecting HIV testing among youth in Kenya. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16. 10.3390/ijerph16081450. [Epub ahead of print: 24 04 2019]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang W, Alva S, Wang S. HIV-Related knowledge and behaviors among people living with HIV in eight high HIV prevalence countries in sub-Saharan Africa. ICF International, 2012. http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/AS29/AS29.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim SW, Skordis-Worrall J, Haghparast-Bidgoli H, et al. Socio-Economic inequity in HIV testing in Malawi. Glob Health Action 2016;9:31730. 10.3402/gha.v9.31730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wabiri N, Taffa N. Socio-economic inequality and HIV in South Africa. BMC Public Health 2013;13:1037. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Larose A, Moore S, Harper S, et al. Global income-related inequalities in HIV testing. J Public Health 2011;33:345–52. 10.1093/pubmed/fdr001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Erena AN, Shen G, Lei P. Factors affecting HIV counselling and testing among Ethiopian women aged 15-49. BMC Infect Dis 2019;19:1076. 10.1186/s12879-019-4701-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Department of Health Service . Annual report 2074/75, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Centre for AIDS and STD Control . HIV Factsheet. National Centre for AIDS and STD Control, 2019. Available: http://www.ncasc.gov.np/WAD2019/Factsheet2019.pdf

- 36.NCASC . Subnational HIV estimates of Nepal, 2018. National Centre for AIDS and STD control, Ministry of health and population, 2018. Available: https://l.facebook.com/l.php?u=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.ncasc.gov.np%2FWAD2019%2Fsubnational-estimates-nepal-2018.pdf [Accessed 13 Sep 2020].

- 37.Thapa S, Thapa DK, Buve A, et al. Hiv-Related risk behaviors among labor migrants, their wives and the general population in Nepal. J Community Health 2017;42:260–8. 10.1007/s10900-016-0251-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.UNAIDS . Global AIDS monitoring online reporting tool 2019. UNAIDS, 2020. Available: http://ncasc.gov.np/uploaded/GAM/1-GAM-Report-Nepal-2019.pdf [Accessed 27 Aug 2020].

- 39.Yadav SN. Risk of HIV among the seasonal labour migrants of Nepal. Online J Public Health Inform 2018;10. 10.5210/ojphi.v10i1.8960 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.NCASC . Integrated biological and behavioral surveillance (IBBS) survey among female sex workers in the 22 Terai highway districts of Nepal, round 7, Nepal. Ministry of health and population, National centre for AIDS and STD control, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-049415supp001.pdf (131.8KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Data are available in a public, open access repository. The datasets generated during the current study are available from within the Demographic and Health Survey Program repository (https://dhsprogram.com/data/ available-datasets.cfm).