Abstract

Despite the important role that family members can play in dementia care, little is known about the association between the availability of family members and the type of care, informal (unpaid) or formal (paid), that is actually delivered to older adults with dementia. After examining persons with dementia using the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), we found significantly lower spousal availability but greater adult child availability among women vs. men, non-Hispanic blacks vs. non-Hispanic whites, and those with lower vs. higher socioeconomic status. Adults with dementia and disability who have greater family availability are significantly more likely to receive informal care and less likely to use formal care. In particular, the predicted probability of a community-dwelling adult moving to a nursing home over the subsequent two years is substantially lower for those who had a coresident adult child (11%), compared to those who didn’t have a coresident adult child but had at least one adult child living close (20%) and to all children living far (23%). Health care policies on dementia should consider potential family availability in predicting the type of care persons with dementia will use and the potential disparities in consequences for persons with dementia and their families.

INTRODUCTION

About 6 million adults age 65 and older in the United States have dementia, with the number projected to more than double by 2050. 1,2 Total costs for paid care services used by individuals with dementia were estimated at $355 billion in 2021.2 However, more than 11 million family members and other unpaid caregivers provided care to people with dementia in 2020.2 The value of informal care (i.e., care from family members and other unpaid helpers) may be comparable to the total costs of care purchased from the market.3

People with dementia usually prefer to reside in their own homes as long as possible,4 an option that is often less costly than alternative types of care. 5 Spouses and adult children, especially daughters, play a major role in providing care for older adults who live in their homes. 6,7 However, not all older adults have access to family members who live nearby and are able to devote the time and energy required to provide care that meets changing care needs. 8,9 Lower marriage and birth rates in recent decades 10,11 may substantially reduce the potential pool of family caregivers for the aging population. Individuals with dementia who have little family availability (no spouse or no adult child nearby) need to depend largely on paid in-home care service, adult day care, and nursing home care to help with daily activities of living, or they may go without necessary care. Most older adults with dementia lack sufficient financial resources to cover the costs of long-term care; many depend on Medicaid for partial or full coverage of such services. 12,13

Despite the importance of knowledge about potential family availability in predicting care use and related costs, there is little evidence on this, especially specific to dementia care. Several studies, some of which focus on dementia caregivers, suggest the significant influence of active family caregiving on health care use and cost 14–18. While providing valuable insights into the relationship between informal and formal (paid) care utilization, these studies focusing on active family caregiving do not address the influence of the potential availability of family members (e.g., spatial proximity to an adult child), which is likely to affect the amount of family caregiving that is actually provided.

In some studies, family availability (e.g., having a daughter) was used as an instrumental variable to reduce endogeneity in assessing the effect of informal care on formal care use 15,18, but not as the primary predictor nor specific to dementia. Other studies examined more explicitly the potential effect of family structure and availability on care utilization and transitions, 19,20 but not specific to dementia.

A better understanding of the effect that a potential pool of family caregivers might have on care utilization specific to people with dementia is critically important -- for predicting care utilization, care transitions, and care costs associated with dementia. There may also be significant heterogeneity in family availability among individuals with dementia. Understanding differences across gender, racial, ethnic, and economic groups could help identify individuals who are vulnerable to going without necessary dementia care.

The study provides important new evidence on dementia care resources and care utilization by examining disparities in potential family care availability and the association between the family availability and the informal and formal care used by individuals with dementia, which should inform policies and interventions aimed at improving dementia care overall.

The specific research questions are: What is the status of spouse and adult child availability among adults with dementia? And to what extent is the availability of a spouse or adult child associated with informal care and formal care used by older adults with dementia?

STUDY DATA AND METHODS

To answer the first question, we provide descriptive statistics of the availability of spouses and adult children for adults with dementia – for overall sample and each demographic and socioeconomic subgroup. To address the second question about the potential influence of family availability on care utilization, we use multivariable analyses to reduce endogeneity in predicting their informal and formal care utilization.

DATA AND SAMPLE

We created three analysis samples based on data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally representative longitudinal dataset of older adults.

First, we created a dementia sample using the Langa--Weir approach to select a sample of adults 55 or older who had dementia,21 as described in Appendix Method A1.22 We use the HRS Core data surveyed over the years of 2002–2014 (biennial) to have all key information for the study. For example, prior to 2002, we cannot distinguish caregivers who help with activities of daily living (ADL) from caregivers who help with instrumental activities of daily living (IADL). And the RAND HRS Family File which includes information to identify adult children (e.g., age of each child) is currently not available beyond the survey year of 2014. We did not include the HRS Exit interview data in the main analysis sample because the sample person’s ADL status at the time of care utilization (e.g., formal and informal care) is not available in the Exit interview. The minimum age of 55 was chosen because, with a refreshment sample every six years, the HRS is representative of adults 55 and older for all survey waves during the study period. Also, about 13.4 % of our dementia sample was 55–64, which is not trivial. The dementia sample for this study includes 4,955 persons and 9,365 person- year observations. This sample is used to provide estimates of family availability for persons with dementia – overall and for each demographic and socioeconomic group.

Second, to assess the care provided by informal caregivers and formal helpers in relation to family availability, we restricted the dementia sample further to those who had a limitation with at least one ADL (walking across a room, dressing, bathing, eating, getting in and out of bed, and using the toilet) at the time of interview. In this sub-sample, there were 3,390 persons and 5,686 person-year observations.

Third, we restricted the sample further to those who were community-dwelling in the previous interview (2,852 persons and 4,259 person-year observations) to examine the likelihood that adults with and without available family members would transition to a nursing facility over the subsequent two years. This sample was also used to estimate the predicted probability and amount of informal and formal care used that are associated with family availability.

MEASURES

We selected family availability variables that were previously identified as potentially important factors associated with caregiving. 9,15,20,23–25 For spouse availability, we included the presence of spouse (married or partnered); spouse’s disability condition (i.e., having limitation in any ADLs or Instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs)); and employment status of spouse (working full time or not). For potential availability of adult children, we included the number of adult children (1–2, 3+ adult children); the presence of at least one adult daughter; the employment status of adult children (having at least one child not working full time); and geographic distance to the closest adult child (at least one adult child coresident; at least one adult child who isn’t a coresident but lives within 10 miles; all adult children living 10+ miles).

We created an outcome measure that indicates whether older adults with dementia received ADL help from each of the following helper types: spouse; adult biological or adopted child (adult child henceforth); informal helpers (i.e., family member helpers or unpaid helpers); formal helpers (i.e., non-family, paid helper); and nursing home employee. We also created a measure of total hours provided by an ADL helper during the last month.

Covariates include the following: gender; age (55–64, 65–74, 75–84, 85+); race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic others, Hispanic); education (<12, 12, 13– 15, and 16+ years); wealth quartile (defined based on the distribution of household-size-adjusted wealth at each age in each year); the number of ADL limitations; survey design features such as interview mode (face-to-face or not) and proxy interview status; and survey year.

ANALYTIC APPROACH

We first estimated the percentage in each status of spouse and adult child availability for the overall sample (adults 55+ with dementia) and for each demographic and socioeconomic subgroup. Second, we summarized unadjusted estimates of informal and formal ADL help received by adults 55+ with dementia who also had an ADL limitation, specific to the care receipt from each active helper type (informal, spouse, adult child, formal, nursing home employee). Third, to assess the extent to which family availability influenced the probability of care received over the subsequent two years, we estimated the adjusted probability of ADL help received associated with each family availability measure, using multivariable logistic regression. We also estimated the adjusted predicted total hours of care received by adults with dementia for each family availability status using a two-part model 26: logit model for the first part (i.e., helped or not) and generalized linear model with gamma distribution and log-link for the second part (i.e., positive hours). We calculated the adjusted probabilities and hours by holding all control variables at their mean values.

Our base controls, which were included for all multivariable analyses, contain survey year indicators, the number of ADL limitations, interview mode, the status of proxy interview, demographic and socioeconomic variables that were surveyed two years prior to the outcome measure. Additional variables were added to some analyses to control for confounding effects specific for each analysis. See Appendix Exhibit A2 and A3 for specific adjustment variables for each model. 22

We conducted sensitivity and auxiliary analyses. First, we re-estimated family availability using recent surveys (2010– 2014) to check if the results from recent data substantively differ from results using all available survey years (2002– 2014). Second, for the main analyses, we imputed family availability for all main analyses (0.1% to 3.4% missing values depending on variables in the study sample). To check whether the imputation potentially changed results, we replicated the summary statistics of family availability status using data without imputation. Third, there were some mismatched cases between the respondents’ report and actual data record in terms of the number of children. We repeated our analyses by dropping sample persons who did not have consistent information between the reported total number of children vs. counts of all child records in the child-level data file. Fourth, we re-estimated the multivariable analyses by including the HRS Exit data as well as the HRS Core data.

Population weights were applied for all analyses, and a complex survey design including stratification and cluster (i.e., primary sampling unit) was incorporated to adjust variances in estimates.

Limitations

Several study limitations should be noted. First, the primary study design was cross-sectional, which allowed us to provide national estimates of family care availability and care use for the general population of dementia. We incorporated some longitudinal features of the data to assess possible transitions to a nursing home by linking family availability with care outcomes measured in the subsequent survey year. However, our data cannot provide causal implications nor the level of detail to describe how families make decisions over time about the care they can provide. A rigorous longitudinal approach is recommended to provide further insights into family availability and care dynamics over the course of dementia.

Second, because the study population of interest was persons with dementia, we had to rely on information provided by a proxy for those who could not provide the information themselves. While we controlled for the sample person’s proxy status in all multivariable analyses, the bias in the estimates may not be fully addressed.

Third, a variable to assess whether adult children have a minor child (e.g., age <18) was not available in HRS. Because having a minor child at home is a competing demand of care, it may affect the availability of adult children to provide dementia care for their parents.

RESULTS

Spouse and Adult Child Availability for Older Adults with Dementia

This section summarizes spouse and adult child availability among adults 55+ with dementia – for the overall sample and for each demographic and socioeconomic subgroup.

Spouse availability:

As summarized in Exhibit 1, the majority of adults 55+ with dementia did not have a spouse (62%) and about a quarter of the adults with dementia had a spouse without a disability; the rate was lower for women vs. men (16% vs. 38%), for non-Hispanic blacks vs. other racial/ethnic groups (19% vs. 25–27%), for the lowest vs. the highest education group (22% vs. 36%), and for the lowest vs. the highest wealth group (9% vs. 41%). Overall, the rate of having a spouse working full- time is low (3.6%), although the rate is relatively higher for men (6%), those in younger ages (15% ages 55–64), with higher education (6% with 16 or more years of schooling) and greater wealth (6% among the top 25% of the wealth distribution).

EXHIBIT 1.

Spousal availability by demographic and socioeconomic status among adults with dementia

| Spouse present |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spouse’s ADL/IADL status |

Spouse’s working status |

|||||

| N. of obs | No spouse present (%) | No limitation (%) | At least one limitation (%) | Not working full-time (%) | Working full-time (%) | |

|

| ||||||

| Overall | 9,365 | 62.3 | 24.2 | 13.4 | 34.1 | 3.6 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Men | 3,507 | 41.3 | 38.3 | 20.4 | 52.8 | 6.0 |

| Women | 5,858 | 75.2 | 15.6 | 9.1 | 22.6 | 2.1 |

| Age | ||||||

| 55–64 | 981 | 49.8 | 36.3 | 13.8 | 35.2 | 15.0 |

| 65–74 | 1,844 | 49.3 | 36.1 | 14.6 | 44.2 | 6.5 |

| 75–84 | 3,186 | 58.0 | 27.5 | 14.5 | 41.0 | 1.0 |

| 85+ | 3,354 | 78.7 | 9.8 | 11.5 | 21.2 | 0.1 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| NH White | 5,233 | 60.9 | 25.3 | 13.8 | 36.0 | 3.1 |

| NH Black | 2,499 | 70.6 | 18.5 | 10.9 | 25.0 | 4.4 |

| NH Others | 232 | 61.2 | 26.0 | 12.8 | 33.2 | 5.6 |

| Hispanic | 1,392 | 57.8 | 26.8 | 15.4 | 37.9 | 4.3 |

|

| ||||||

| Education | ||||||

| <12 years | 5,348 | 65.5 | 21.5 | 13.1 | 31.8 | 2.7 |

| 12 | 2,328 | 62.8 | 24.8 | 12.4 | 33.4 | 3.8 |

| 13–15 | 995 | 57.7 | 27.8 | 14.5 | 36.7 | 5.6 |

| 16+ | 680 | 46.3 | 36.1 | 17.6 | 47.9 | 5.8 |

| Total wealth | ||||||

| Bottom 25% | 2,880 | 83.2 | 8.5 | 8.3 | 15.2 | 1.6 |

| 25–50% | 2,284 | 65.2 | 21.2 | 13.6 | 31.9 | 2.9 |

| 50–75% | 2,254 | 52.6 | 30.5 | 16.9 | 42.9 | 4.5 |

| Top 25% | 1,947 | 43.3 | 40.8 | 15.9 | 50.8 | 5.9 |

Source. Author’s analysis of data from the 2002–2014 Health and Retirement Study.

Notes. Sample: Adults aged 55+ with dementia; 4,955 persons and 9,365 person-year observations. The estimates of percentages add up to 100% if the percentage of no spouse is added to the sum of all percentages under each panel of spouse availability on each row. Due to rounding, not all proportions add up to 100% (e.g., among women, 75.2+15.6+9.1=99.9 and 75.2+22.6+2.1=99.9)

Adult Child availability:

Most adults with dementia had at least one adult child (88% in Exhibit 2), and about half (51%) had three or more adult children; 73% of adults 55+ with dementia had at least one daughter (in Appendix Exhibit A4). The majority of the sample had at least one adult child who was not employed full-time (and hence assumed to have more time available for caregiving). This rate was substantially higher for those with less than 12 years of schooling (65%) compared to those with 16 or more years of schooling (46%). About one- quarter of adults with dementia had at least one adult child coresident, but a similar share (23%) had no adult child living nearby. There are substantial differences in the availability of adult children. The percentage of Hispanic adults with dementia having a coresident adult child was 40%, substantially greater than non-Hispanic whites with dementia (18%). Adults with dementia in the lowest education and wealth group had a greater rate of having an adult child coresident than the highest by large. Overall, results from sensitivity analyses were consistent with those from the main analyses (as shown in Appendix Exhibit A5–A10). 22

EXHIBIT 2.

Adult child availability by demographic and socioeconomic status among adults with dementia

| Adult child present |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N. of adult children |

Have a non-full-time-working adult child |

Proximity to adult children |

|||||||

| N. of obs | No adult child (%) | One or two (%) | Three or more (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | None within 10 miles (%) | At least one within 10 miles (%) | At least one coresident (%) | |

|

| |||||||||

| Overall | 9,365 | 11.8 | 37.5 | 50.7 | 29.5 | 58.7 | 22.6 | 41.5 | 24.2 |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Men | 3,507 | 13.6 | 35.5 | 50.9 | 34.4 | 52.0 | 28.4 | 38.8 | 19.2 |

| Women | 5,858 | 10.6 | 38.7 | 50.6 | 26.5 | 62.8 | 19.0 | 43.1 | 27.2 |

| Age | |||||||||

| 55–64 | 981 | 18.0 | 35.8 | 46.2 | 29.1 | 52.9 | 21.3 | 33.7 | 27.0 |

| 65–74 | 1,844 | 9.7 | 36.0 | 54.3 | 37.3 | 53.0 | 27.0 | 38.2 | 25.2 |

| 75–84 | 3,186 | 9.4 | 34.9 | 55.7 | 34.6 | 56.0 | 21.7 | 44.7 | 24.2 |

| 85+ | 3,354 | 12.8 | 41.6 | 45.6 | 20.4 | 66.8 | 21.6 | 43.2 | 22.5 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||||

| NH White | 5,233 | 11.2 | 41.9 | 46.9 | 32.8 | 56.0 | 25.3 | 45.2 | 18.3 |

| NH Black | 2,499 | 14.5 | 30.4 | 55.0 | 23.0 | 62.4 | 18.6 | 35.4 | 31.4 |

| NH Others | 232 | 11.4 | 42.0 | 46.6 | 29.3 | 59.3 | 19.4 | 34.9 | 34.3 |

| Hispanic | 1,392 | 10.6 | 25.8 | 63.6 | 23.3 | 66.1 | 15.6 | 34.0 | 39.8 |

| Education | |||||||||

| <12 years | 5,348 | 11.2 | 31.5 | 57.3 | 23.8 | 65.0 | 20.8 | 40.5 | 27.5 |

| 12 | 2,328 | 12.1 | 45.4 | 42.5 | 35.1 | 52.8 | 22.1 | 44.8 | 21.0 |

| 13–15 | 995 | 11.7 | 41.8 | 46.5 | 35.9 | 52.3 | 25.1 | 42.7 | 20.5 |

| 16+ | 680 | 12.6 | 46.6 | 40.8 | 41.0 | 46.3 | 32.6 | 36.3 | 18.4 |

| Total wealth | |||||||||

| Bottom 25% | 2,880 | 15.2 | 35.1 | 49.7 | 25.5 | 59.3 | 21.5 | 37.8 | 25.6 |

| 25–50% | 2,284 | 11.1 | 33.3 | 55.6 | 25.7 | 63.2 | 20.8 | 37.6 | 30.6 |

| 50–75% | 2,254 | 10.2 | 37.1 | 52.6 | 31.4 | 58.3 | 21.6 | 43.1 | 25.0 |

| Top 25% | 1,947 | 9.8 | 45.6 | 44.6 | 36.7 | 53.5 | 27.0 | 48.6 | 14.6 |

Source. Author’s analysis of data from the 2002–2014 Health and Retirement Study.

Notes. Sample: Adults aged 55+ with dementia; 4,955 persons and 9,365 person-year observations. The estimates of percentages add up to 100% if the percentage of no adult child is added to the sum of all percentages under each panel of child availability on each row. Due to rounding, not all proportions add up to 100% (e.g., 10.6+19.0+43.1+27.2=99.9 for proximity among women).

Overview of Informal and Formal Help Received by Adults with Dementia Who Have at Least One ADL limitation

Among those 55+ with dementia, about 60% have some limitation in activities of daily living (ADL). In this section, we provide an overview of the rate and amount of ADL care received from family members and other informal and formal helpers among adults 55+ with dementia who also have an ADL limitation.

Overall, about 81% of these adults received care from an ADL helper (see Exhibit 3); 50% from an informal helper, and 44% from a formal helper. About 18% of the sample received care from their spouse and 27% from an adult child. Considering only those who received care from an ADL helper during the last month, the total hours of help received from a spouse was substantially higher than the total hours of help received from adult children: 245 hours vs. 157 hours. However, because many more adults with dementia and an ADL limitation received care from an adult child than from a spouse, unconditional average total hours of help received during the last month (i.e., including cases of zero hours as well as cases of positive hours) was comparable between total hours of care from a spouse and from adult children (43 hours vs. 42 hours). Results from sensitivity analyses conducted by dropping adults with mismatched information on the number of children were consistent with those from the main analyses, as shown in Appendix Exhibit A11. 22

EXHIBIT 3.

Informal and formal ADL help received by adults with dementia, unadjusted

| Average total hours of help |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of those who received care from the given helper type |

including zero hour as well as positive hours | including positive hours only | |||||||

| N. of obs | % | 95% CI | N | Mean | 95% CI | N | Mean | 95% CI | |

|

| |||||||||

| ADL care received from: | |||||||||

| Informal/formal helper | 5,471 | 80.5 | (79.2,81.7) | ||||||

| Informal helper | 5,496 | 50.2 | (48.5,51.9) | 5,496 | 120.5 | (114.4,126.6) | 2,732 | 240.2 | (230.9,249.5) |

| - Spouse | 5,627 | 17.7 | (16.2,19.3) | 5,627 | 43.3 | (38.3,48.3) | 931 | 244.5 | (230.6,258.3) |

| - Adult child | 5,607 | 26.6 | (25.0,28.1) | 5,607 | 41.6 | (38.1,45.1) | 1,503 | 156.7 | (146.6,166.8) |

| Formal helper | 5,657 | 44.3 | (42.3,46.4) | ||||||

| - Nursing home employee | 5,683 | 33.9 | (31.9,35.9) | ||||||

Source. Author’s analysis of data from the 2002–2014 Health and Retirement Study.

Notes. Sample: adults 55+ with dementia and at least one ADL limitation; 3,390 persons and 5,686 person-year observations. Hours from an ADL helper might include hours spent with an IADL help if the ADL helper provided IADL help as well. Hours of help from the nursing home employee were not available; accordingly, numbers related to the hours of help from a formal helper were not estimated and left blank.

Implications of Family Availability for Informal and Formal ADL Care Used by Adults with Dementia

In this section, we report estimates of the extent to which informal and formal care differ by family availability. Using the same analysis sample of age 55+ with dementia and an ADL limitation, we summarized spouse and adult child availability (See Appendix Exhibit A12 and Appendix Exhibit A13) 22 and unadjusted estimates on the care receipt by the spouse and adult child availability (See Appendix Exhibit A14 for care outcomes stratified by spouse availability and Appendix Exhibit A15 for care outcomes stratified by adult child availability).22

To reduce potential endogeneity in predicting the risk of transition to a nursing home over the subsequent two years, we used a more restrictive sample that focuses on those community- dwelling two years before the survey of care utilization outcomes. See Appendix Exhibit A16 and Appendix Exhibit A17 22 for estimates on family availability using this sample. We report those results below when they show a significant difference in the predicted care outcomes of any informal care receipt or any formal care receipt, based on the adjusted models. See Appendix Exhibit A2 and Appendix Exhibit A3 22 for details about samples, outcomes, main predictors, and covariates. Full results including all family availability predictors are summarized in Appendix Exhibit A18–A20. 22

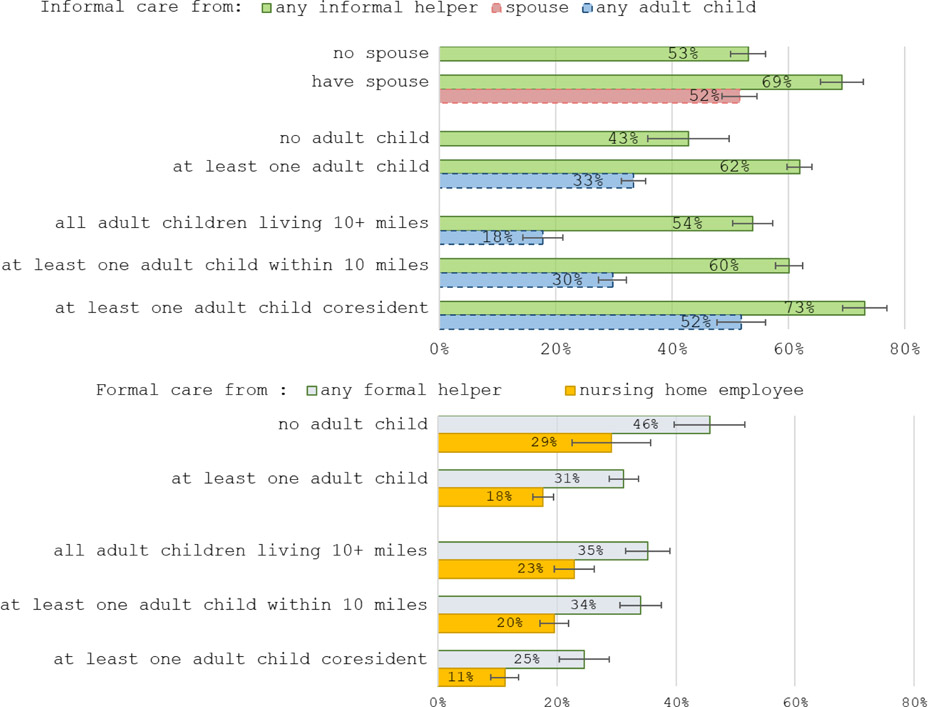

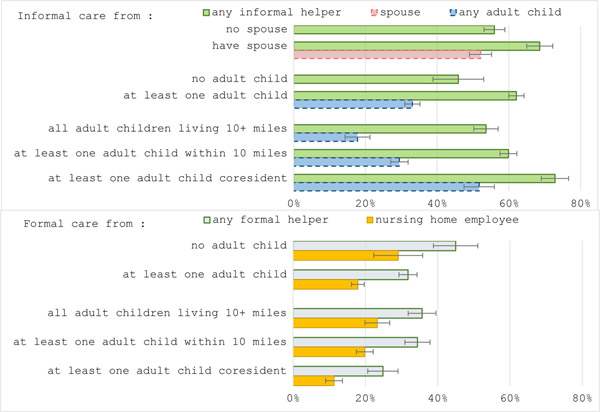

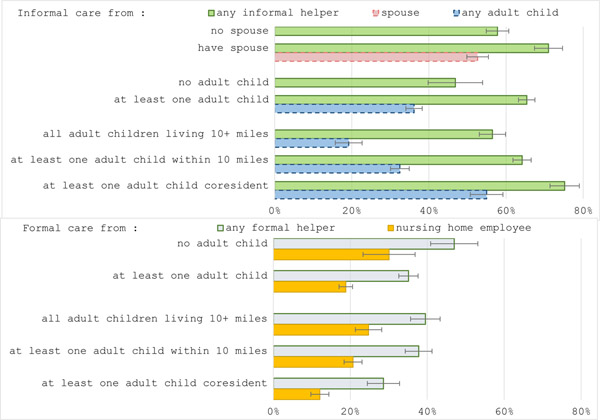

Informal care

Spouse availability:

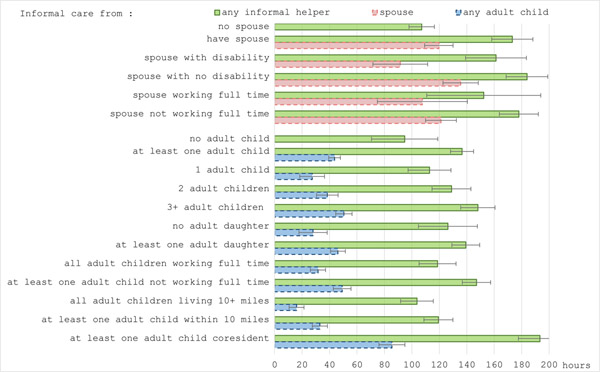

As demonstrated in the top panel of Exhibit 4, the adjusted probability of adults with dementia receiving any informal help with ADLs was significantly lower for those who did not have a spouse two years before the survey of care receipt outcome: 53% vs. 69%. Likewise, the adjusted total hours of help received from all informal ADL helpers were significantly lower in the case of not having a spouse vs. having a spouse: 107 hours vs. 173 hours, as shown in Appendix Exhibit A19. 22

EXHIBIT 4.

Adjusted probability of receiving informal and formal care from ADL helper over the subsequent two years, by spousal and adult child availability

Adult child availability:

Having no adult child compared to having at least one adult child is associated with a substantially lower probability of receiving any informal care: 43% vs. 62%, respectively (Exhibit 4). The adjusted probability of receiving ADL care from an adult child was 33%. The predicted total monthly hours from all ADL informal helpers is substantially lower if one does not have any adult child: 95 hours vs. 137 hours, as in Appendix Exhibit A19. 22

The adjusted probability of any informal ADL care received by older adults with dementia was substantially higher if they had a coresident adult child (73% vs. 54% if they did not have an adult child within ten miles and 60% if they had at least one adult child within ten miles. The adjusted probability of receiving ADL care from an adult child among those who have a coresident child is 52%, which is similar to that from a spouse (53%). Predicted total monthly hours from all informal ADL helpers are substantially greater if they had a coresident adult child: 193 hours with a coresident adult child vs. 104 hours with no adult child living nearby and 119 hours with at least one adult child living nearby but not coresident. See Appendix Exhibit A19. 22

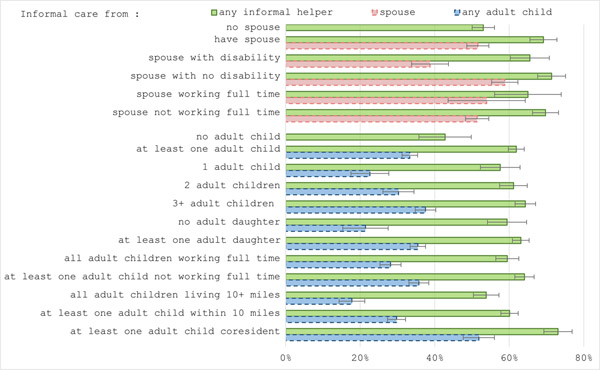

Other family factors:

Other family availability factors, including disability status of a spouse, working status of a spouse, having a daughter, and having an adult child not working full time, were not significantly associated with the incidence and amount of any informal ADL care received by adults with dementia. However, all these factors except the working status of a spouse were significantly associated with ADL care provided by the specific helper. See Appendix Exhibit A18–A19 for details.22 For example, spousal disability status was not associated with the difference in overall informal care received, but adults with dementia and ADL limitation were likely to receive more hours of spousal care if their spouse did not have any disability (136 hours) than if their spouse had a disability (92 hours) as shown in Appendix Exhibit A19. 22

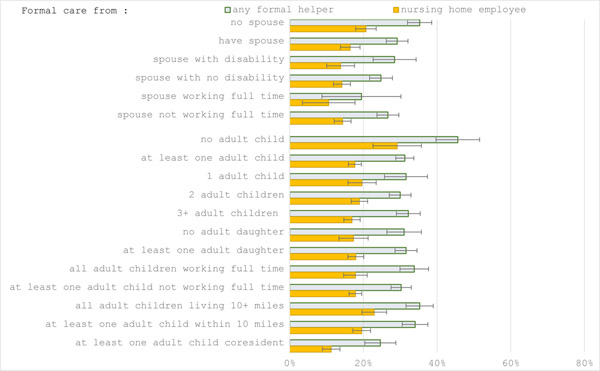

Formal care

As presented in the bottom panel of Exhibit 4, having an adult child is significantly associated with a lower, adjusted probability of receiving any formal ADL care -- 31% if at least one adult child vs. 46% if no adult child. The adjusted probability of receiving help from an employee of a nursing home also differed significantly by the status of having an adult child: 29% if no adult child; 18% if at least one adult child.

Conditional on those who had at least one adult child, the adjusted probability of receiving institutional care was significantly lower if adults with dementia and ADL who had a coresident adult child two years before the survey of care outcomes (11%) compared to those whose adult children all lived farther than 10 miles (23%) and those who had an adult child within 10 miles but not coresident (20%). Other family availability factors (e.g., spouse availability, the number of children, having a daughter, having a child not working full time) were not significantly associated with the probability of using formal care over the subsequent two years. For details, see Appendix Exhibit A20.22

Results from the sensitivity analyses based on dropping the respondents with mismatched information on the number of children were consistent with those from the main analyses, as shown in Appendix Exhibit A21. 22 Results from analysis including the sample from the HRS EXIT data were consistent with the finding from the main data (i.e., using HRS Core data only), as shown in Appendix Exhibit A22.

DISCUSSION

This study provides national estimates of family availability for adults with dementia and assesses the potential influence of spouse and adult child availability on informal and formal care used by the adults with dementia. The paper extends the dementia care literature in significant ways. Most previous studies focused on active family caregivers, which is important for assessing the caregivers’ burden. However, it is essential to understand the potential care pool available to older adults with dementia in order to predict the type of care they will utilize, transitions to institutional care, and the associated care costs to the older adults, their families, and the public. For example, a spouse who is an active caregiver provides substantially more hours of care than an adult child who is an active caregiver. However, the majority of adults with dementia do not have a spouse. Spousal availability is especially limited among Non-Hispanic blacks and those with lower socioeconomic status, which may lead to a greater dependence on adult children for ADL care among these groups. In other words, there may be an unequal, intergenerational spillover effect in that children of some vulnerable groups defined by race, ethnicity, and economic status may incur more care responsibility and (opportunity) costs than other groups.

Our findings from the multivariable models suggest that having a coresident child reduces the likelihood of using formal care and transitioning to a nursing home among adults with cognitive and physical limitations. Despite the substantial care contribution of a spouse, spousal availability was not independently associated with the likelihood of subsequent formal ADL care use by adults with dementia. Primary responsibility for ADL care may be assigned sequentially, first to a spouse (if physically and cognitively able) followed by an available adult child (if a spouse is unavailable), and then by other informal helpers (e.g., sibling, other relatives, and friends) or paid caregivers if a spouse or adult child is not available.27 In other words, for those without a spouse, adult children may step in until they are no longer able to provide the needed level of care. Therefore, the availability of adult children may be more directly linked with the need to use formal care than the availability of a spouse.

A substantial share of informal care received by adults with dementia was unaccounted for by care provided by either a spouse or adult child acting alone. This implies that there are multiple informal caregivers and combinations of caregivers (e.g., spouse together with an adult child; or an adult child together with other relatives and friends) who may provide help for adults with dementia over the course of their illness. Future research is needed to examine how care is shared across the full spectrum of dementia progression.

Conclusion

This study provides significant evidence about family care availability for adults with dementia and its potential influence on informal and formal care use. The development of a care system that integrates informal with formal care has been considered essential for a sustainable health care system, especially one providing dementia care.28,29 To develop such a system, policymakers should understand how the availability of spouses and adult children translates into actual care for adults with dementia.

The study also provides important insights into the potential vulnerability of individuals with dementia who have limited family availability and are thus at greater risk of needing a long-term care facility. It also suggests that a reliance on spouse and adult children as primary caregivers is likely to have differential consequences for caregivers across racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups. Policies and interventions that promote family care involvement should also consider substantial heterogeneity in potential family care resources.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Health and Retirement Study is funded by the National Institute on Aging (U01 AG009740) and performed at the Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan.

Dr. Choi was supported by National Institute on Aging K01AG057820.

Dr. Langa was supported by National Institute on Aging grant R01 AG053972.

Appendix Method A1.

To identify people with dementia, we followed the Langa--Weir approach 1 that used the total score of cognitive functioning ranges from 0 to 27 points (higher value means better cognitive functioning). This score is the sum based on immediate word recall (0–10 points), delayed word recall (0–10 points), serial 7s (0–5 points), and backwards counting from 20 (0–2 points). A total score of 0–6 points was classified as dementia.1 The cognitive functioning assessments were not available for sample persons with a proxy interview (44% out of aged 55+ with dementia). Therefore, the Langa-Weir approach based on information from the proxy and informant was used for sample persons with a proxy interview. The total score ranges 0 to 11 (higher value means poorer cognitive functioning) by summing scores based on: i) a direct assessment of memory ranging from excellent to poor (Score 0–4); ii) an assessment of limitations in five instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), including managing money, taking medication, preparing hot meals, using phones, and doing groceries (Score 0–5); and iii) the interviewer assessment of difficulty completing the interview because of cognitive limitation (Score 0–2 indicating none, some, and prevents completion). A total score of 6–11 were classified as dementia for the sample persons with a proxy interview based on Langa—Weir classificaiton.1

- 1.Crimmins EM, Kim JK, Langa KM, Weir DR. Assessment of cognition using surveys and neuropsychological assessment: the health and retirement study and the aging, demographics, and memory study. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2011;66(suppl 1):i162–i171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Appendix Exhibit A2.

Description of prediction models for informal care - Samples, outcomes, main predictors, and covariates

| Main predictor: Family availability | Model | Outcome: Informal care from (incident & amount) | Control variables | Sample restrictions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spouse availability | presence of spouse | 1 | Any type | Base controlb | Base sample restrictiona (N=4,259) |

| 2 | Spouse | Base sample restrictiona + spouse present (N=1,783) | |||

| disability status of spouse | 3 | Any type | |||

| 4 | Spouse | ||||

| working status of spouse | 5 | Any type | Base controlb + spouse disability (IADL/ADL) | ||

| 6 | Spouse | ||||

| Child availability | presence of adult children | 7 | Any type | Base controlb + marital status of respondent | Base sample restrictiona (N=4,259) |

| 8 | Adult children | Base sample restrictiona + adult child present (N=3,795) | |||

| number of adult children | 9 | Any type | |||

| 10 | Adult children | ||||

| presence of daughter | 11 | Any type | Base controlb + marital status of respondent + number of adult biological children | ||

| 12 | Adult children | ||||

| working status of adult children | 13 | Any type | |||

| 14 | Adult children | ||||

| distance to adult child | 15 | Any type | |||

| 16 | Adult children | ||||

Base sample restriction is to include adults 55+ with dementia and at least one ADL limitation in interview year T (T=2002–2014) and community-dwelling in year T-2.

Base control includes year, interview mode, proxy status, age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, wealth in quartile, and the number of ADL limitations in interview year T-2.

Appendix Exhibit A3.

Description of prediction models for formal care - Samples, outcomes, main predictors, and covariates

| Main predictor: Family Availability | Model | Outcome: Formal care from | Control variables | Sample restrictions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spouse availability | presence of spouse | 1 | Any type | Base controlb | Base sample restrictiona (N=4,259) |

| 2 | Nursing home employee | ||||

| disability status of spouse | 3 | Any type | Base sample restrictiona + spouse present (N=1,783) | ||

| 4 | Nursing home employee | ||||

| working status of spouse | 5 | Any type | Base controlb + spouse disability (IADL/ADL) | ||

| 6 | Nursing home employee | ||||

| Child availability | presence of adult children | 7 | Any type | Base controlb + marital status of respondent | Base sample restrictiona (N=4,259) |

| 8 | Nursing home employee | ||||

| number of adult children | 9 | Any type | Base sample restrictiona + adult child present (N=3,795) | ||

| 10 | Nursing home employee | ||||

| presence of daughter | 11 | Any type | Base controlb + marital status of respondent + number of adult biological children | ||

| 12 | Nursing home employee | ||||

| working status of adult children | 13 | Any type | |||

| 14 | Nursing home employee | ||||

| distance to adult child | 15 | Any type | |||

| 16 | Nursing home employee | ||||

Base sample restriction is to include adults 55+ with dementia and at least one ADL limitation in interview year T (T=2002–2014) and community-dwelling in year T-2.

Base control includes year, interview mode, proxy status, age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, wealth in quartile, and the number of ADL limitations in interview year T-2.

Appendix Exhibit A4.

Adult child availability by the status of having a daughter among adults 55+ with dementia (Sample: Adults aged 55+ with dementia; 4,955 persons and 9,365 person-year observations)

| Adult child present |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have an adult daughter |

||||

| N. of obs | No adult child (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | |

|

| ||||

| Overall | 9,365 | 11.8 | 15.3 | 72.9 |

| Gender | ||||

| Men | 3,507 | 13.6 | 16.4 | 70.0 |

| Women | 5,858 | 10.6 | 14.7 | 74.7 |

| Age | ||||

| 55–64 | 981 | 18.0 | 18.9 | 63.1 |

| 65–74 | 1,844 | 9.7 | 14.4 | 75.9 |

| 75–84 | 3,186 | 9.4 | 13.8 | 76.8 |

| 85+ | 3,354 | 12.8 | 16.0 | 71.2 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| NH White | 5,233 | 11.2 | 16.5 | 72.3 |

| NH Black | 2,499 | 14.5 | 13.1 | 72.4 |

| NH Others | 232 | 11.4 | 21.1 | 67.5 |

| Hispanic | 1,392 | 10.6 | 11.7 | 77.7 |

| Education | ||||

| <12 | 5,348 | 11.2 | 14.3 | 74.5 |

| 12 | 2,328 | 12.1 | 15.8 | 72.0 |

| 13–15 | 995 | 11.7 | 18.1 | 70.2 |

| 16+ | 680 | 12.6 | 17.3 | 70.1 |

| Total wealth | ||||

| Bottom 25% | 2,880 | 15.2 | 15.5 | 69.3 |

| 25–50% | 2,284 | 11.1 | 13.2 | 75.7 |

| 50–75% | 2,254 | 10.2 | 14.9 | 74.9 |

| Top 25% | 1,947 | 9.8 | 17.9 | 72.3 |

Source. Author’s analysis of data from the 2002–2014 Health and Retirement Study. Notes. The estimates of percentages add up to 100% if the percentage of no adult child is added to the sum of percentages under the panel of “Have an adult daughter” (e.g.,10.6+14.7+74.7=100.0 for women)

Appendix Exhibit A5.

Spousal availability by demographic and socioeconomic status among adults with dementia, using 2010–2014 data (Sample: Adults 55+ with dementia; 2,746 persons and 4,155 person-year observations)

| Spouse present |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spouse’s ADL/IADL status |

Spouse’s working status |

|||||

| N. of obs | No spouse (%) | No limitation (%) | At least one limitation (%) | Not working full-time (%) | Working full-time (%) | |

|

| ||||||

| Overall | 4,155 | 63.8 | 23.1 | 13.1 | 32.7 | 3.5 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Men | 1,564 | 41.9 | 38.3 | 19.8 | 53.0 | 5.2 |

| Women | 2,591 | 77.4 | 13.6 | 9.0 | 20.1 | 2.4 |

| Age | ||||||

| 55–64 | 553 | 52.7 | 34.7 | 12.7 | 35.1 | 12.2 |

| 65–74 | 680 | 52.3 | 34.6 | 13.1 | 40.5 | 7.3 |

| 75–84 | 1,426 | 59.3 | 26.2 | 14.5 | 39.5 | 1.2 |

| 85+ | 1,496 | 77.6 | 10.2 | 12.1 | 22.2 | 0.2 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| NH White | 2,220 | 61.6 | 24.6 | 13.8 | 35.7 | 2.7 |

| NH Black | 1,118 | 72.8 | 16.9 | 10.3 | 23.1 | 4.1 |

| NH Others | 95 | 58.6 | 27.9 | 13.5 | 35.4 | 6.0 |

| Hispanic | 714 | 62.7 | 23.6 | 13.8 | 32.5 | 4.9 |

|

| ||||||

| Education | ||||||

| <12 | 2,156 | 67.6 | 19.9 | 12.6 | 30.0 | 2.5 |

| 12 | 1,137 | 67.0 | 21.4 | 11.7 | 30.4 | 2.7 |

| 13–15 | 497 | 55.7 | 29.9 | 14.4 | 37.2 | 7.1 |

| 16+ | 353 | 46.6 | 35.1 | 18.3 | 47.2 | 6.2 |

| Total wealth | ||||||

| Bottom 25% | 1,305 | 83.8 | 7.6 | 8.6 | 14.8 | 1.4 |

| 25–50% | 1,007 | 67.0 | 19.9 | 13.1 | 29.8 | 3.2 |

| 50–75% | 978 | 54.0 | 29.0 | 17.0 | 41.8 | 4.2 |

| Top 25% | 865 | 45.4 | 40.0 | 14.7 | 49.0 | 5.6 |

Source. Author’s analysis of data from the 2002–2014 Health and Retirement Study.

Appendix Exhibit A6.

Adult child availability by demographic and socioeconomic status among adults 55+ with dementia, using 2010–2014 data (Sample: Adults 55+ with dementia; 2,746 persons and 4,155 person-year observations)

| Adult child present |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N. of adult children |

Have an adult daughter |

Have a non-full-time-working adult child |

Proximity to adult children |

|||||||||

| N. of obs | No adult child (%) | One (%) | Two (%) | Three or more (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | None within 10 miles (%) | At least one within 10 miles (%) | At least one coresident (%) | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Overall | 4,155 | 11.5 | 12.4 | 25.7 | 50.4 | 15.1 | 73.4 | 27.6 | 60.9 | 22.8 | 40.3 | 25.5 |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Men | 1,564 | 13.8 | 11.8 | 25.7 | 48.8 | 16.6 | 69.6 | 33.3 | 52.9 | 29.3 | 37.3 | 19.6 |

| Women | 2,591 | 10.1 | 12.9 | 25.7 | 51.3 | 14.2 | 75.7 | 24.1 | 65.9 | 18.7 | 42.2 | 29.1 |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 55–64 | 553 | 22.1 | 14.0 | 22.4 | 41.6 | 16.9 | 61.0 | 27.1 | 50.8 | 20.5 | 30.5 | 27.0 |

| 65–74 | 680 | 10.0 | 10.3 | 29.1 | 50.6 | 14.4 | 75.6 | 36.7 | 53.3 | 28.4 | 35.5 | 26.2 |

| 75–84 | 1,426 | 7.3 | 9.7 | 24.9 | 58.1 | 14.1 | 78.6 | 31.5 | 61.2 | 23.3 | 43.7 | 25.7 |

| 85+ | 1,496 | 11.5 | 15.2 | 26.1 | 47.1 | 15.7 | 72.8 | 20.1 | 68.3 | 20.5 | 43.7 | 24.3 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| NH White | 2,220 | 10.9 | 12.3 | 30.7 | 46.2 | 17.1 | 72.1 | 32.4 | 56.7 | 25.8 | 44.3 | 19.0 |

| NH Black | 1,118 | 13.2 | 14.9 | 16.7 | 55.2 | 12.3 | 74.6 | 19.8 | 67.0 | 18.9 | 35.6 | 32.3 |

| NH Others | 95 | 13.6 | 14.7 | 24.8 | 46.8 | 17.1 | 69.2 | 20.7 | 65.7 | 17.4 | 29.4 | 39.6 |

| Hispanic | 714 | 11.4 | 9.6 | 17.7 | 61.2 | 10.9 | 77.7 | 19.8 | 68.8 | 16.4 | 32.7 | 39.4 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Education | ||||||||||||

| <12 | 2,156 | 10.5 | 12.3 | 19.6 | 57.6 | 14.6 | 74.9 | 20.9 | 68.7 | 21.4 | 38.2 | 29.9 |

| 12 | 1,137 | 11.6 | 14.6 | 29.9 | 43.9 | 15.1 | 73.3 | 32.2 | 56.2 | 20.6 | 44.3 | 23.5 |

| 13–15 | 497 | 12.9 | 10.2 | 29.7 | 47.2 | 16.1 | 71.1 | 34.3 | 52.8 | 24.8 | 42.5 | 19.8 |

| 16+ | 353 | 12.4 | 10.4 | 39.5 | 37.7 | 17.3 | 70.4 | 40.4 | 47.3 | 33.3 | 36.8 | 17.6 |

| Total wealth | ||||||||||||

| Bottom 25% | 1,305 | 14.6 | 14.1 | 20.4 | 50.9 | 13.9 | 71.5 | 21.2 | 64.2 | 21.9 | 37.7 | 25.8 |

| 25–50% | 1,007 | 11.0 | 13.7 | 21.2 | 54.0 | 13.4 | 75.6 | 22.8 | 66.1 | 20.8 | 35.7 | 32.5 |

| 50–75% | 978 | 10.1 | 9.5 | 27.7 | 52.6 | 14.9 | 75.0 | 31.4 | 58.5 | 22.3 | 40.7 | 26.9 |

| Top 25% | 865 | 9.4 | 12.1 | 35.2 | 43.3 | 18.9 | 71.7 | 36.8 | 53.8 | 26.5 | 48.1 | 16.0 |

Source. Author’s analysis of data from the 2002–2014 Health and Retirement Study.

Appendix Exhibit A7.

Spousal availability by demographic and socioeconomic status among adults with dementia, without imputation for family availability measures (Sample: Adults 55+ with dementia; 4,955 persons and 9,365 person-year observations)

| Spouse present |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spouse’s ADL/IADL status |

Spouse’s working status |

|||||

| N. of obs | No spouse (%) | No limitation (%) | At least one limitation (%) | Not working full-time (%) | Working full-time (%) | |

|

| ||||||

| Overall | 9,359 | 62.3 | 23.3 | 12.9 | 33.7 | 3.5 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Men | 3,506 | 41.2 | 37.7 | 20.1 | 52.6 | 5.8 |

| Women | 5,853 | 75.2 | 14.4 | 8.4 | 22.2 | 2.1 |

| Age | ||||||

| 55–64 | 981 | 49.8 | 34.9 | 13.9 | 34.8 | 14.6 |

| 65–74 | 1,843 | 49.3 | 35.2 | 13.8 | 43.8 | 6.4 |

| 75–84 | 3,182 | 58.0 | 26.4 | 13.9 | 40.6 | 1.0 |

| 85+ | 3,353 | 78.7 | 9.2 | 10.9 | 20.9 | 0.1 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| NH White | 5,233 | 60.9 | 24.4 | 13.3 | 35.7 | 3.1 |

| NH Black | 2,498 | 70.6 | 17.8 | 10.2 | 24.4 | 4.2 |

| NH Others | 231 | 61.0 | 23.9 | 11.7 | 32.8 | 4.7 |

| Hispanic | 1,388 | 57.7 | 25.5 | 14.9 | 37.5 | 4.2 |

|

| ||||||

| Education | ||||||

| <12 | 5,343 | 65.5 | 20.6 | 12.6 | 31.4 | 2.6 |

| 12 | 2,328 | 62.8 | 23.7 | 11.7 | 33.0 | 3.8 |

| 13–15 | 995 | 57.7 | 26.8 | 13.7 | 36.4 | 5.6 |

| 16+ | 679 | 46.2 | 35.2 | 17.3 | 47.4 | 5.9 |

| Total wealth | ||||||

| Bottom 25% | 2,876 | 83.2 | 8.0 | 7.8 | 14.8 | 1.6 |

| 25–50% | 2,284 | 65.2 | 20.1 | 13.4 | 31.7 | 2.7 |

| 50–75% | 2,253 | 52.6 | 29.7 | 16.2 | 42.6 | 4.4 |

| Top 25% | 1,946 | 43.3 | 39.6 | 15.2 | 50.3 | 5.9 |

Source. Author’s analysis of data from the 2002–2014 Health and Retirement Study.

Appendix Exhibit A8.

Adult child availability by demographic and socioeconomic status among adults 55+ with dementia, without imputation for family availability measures (Sample: Adults 55+ with dementia; 4,955 persons and 9,365 person-year observations)

| Adult child present |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N. of adult children |

Have an adult daughter |

Have a non-full-time-working adult child |

Proximity to adult children |

|||||||||

| N. of obs | No adult child (%) | One (%) | Two (%) | Three or more (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | None within miles (%) | At least 10 one within 10 miles (%) | At least one coresident (%) | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Overall | 9,307 | 11.6 | 13.6 | 24.0 | 50.8 | 15.2 | 73.2 | 29.2 | 58.8 | 22.4 | 41.7 | 24.2 |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Men | 3,476 | 13.3 | 12.2 | 23.6 | 50.9 | 16.1 | 70.5 | 34.1 | 52.2 | 28.5 | 39.0 | 19.0 |

| Women | 5,831 | 10.6 | 14.4 | 24.3 | 50.6 | 14.6 | 74.8 | 26.3 | 62.9 | 18.6 | 43.3 | 27.3 |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 55–64 | 959 | 17.7 | 13.7 | 22.4 | 46.2 | 18.6 | 63.7 | 28.6 | 53.2 | 21.2 | 34.1 | 26.9 |

| 65–74 | 1,832 | 9.5 | 10.4 | 25.7 | 54.4 | 14.3 | 76.3 | 36.5 | 53.7 | 26.6 | 38.5 | 25.3 |

| 75–84 | 3,180 | 9.4 | 12.4 | 22.5 | 55.7 | 13.6 | 77.0 | 34.5 | 55.9 | 21.6 | 44.7 | 24.2 |

| 85+ | 3,336 | 12.7 | 16.4 | 25.3 | 45.6 | 15.9 | 71.4 | 20.1 | 66.8 | 21.4 | 43.3 | 22.3 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| NH White | 5,212 | 11.0 | 13.9 | 28.1 | 47.0 | 16.4 | 72.6 | 32.5 | 56.3 | 25.2 | 45.4 | 18.2 |

| NH Black | 2,476 | 14.6 | 14.5 | 15.9 | 55.0 | 12.4 | 73.0 | 22.3 | 62.3 | 18.3 | 35.3 | 31.5 |

| NH Others | 228 | 11.6 | 17.1 | 25.0 | 46.2 | 21.2 | 67.1 | 29.3 | 58.8 | 20.0 | 35.0 | 33.4 |

| Hispanic | 1,382 | 10.5 | 9.7 | 16.2 | 63.6 | 11.6 | 78.0 | 22.8 | 66.5 | 15.1 | 34.1 | 40.2 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Education | ||||||||||||

| <12 | 5,316 | 11.1 | 13.1 | 18.5 | 57.3 | 14.2 | 74.7 | 23.3 | 65.2 | 20.5 | 40.7 | 27.5 |

| 12 | 2,316 | 12.1 | 15.4 | 30.1 | 42.4 | 15.5 | 72.4 | 34.7 | 52.9 | 22.0 | 44.9 | 20.8 |

| 13–15 | 987 | 11.6 | 13.3 | 28.5 | 46.6 | 17.8 | 70.6 | 36.1 | 52.2 | 25.0 | 42.8 | 20.4 |

| 16+ | 675 | 11.7 | 11.6 | 35.6 | 41.1 | 17.3 | 71.0 | 41.4 | 46.7 | 32.7 | 36.7 | 18.7 |

| Total wealth | ||||||||||||

| Bottom 25% | 2,855 | 15.1 | 15.4 | 19.8 | 49.8 | 15.3 | 69.7 | 25.3 | 59.1 | 21.1 | 38.0 | 25.5 |

| 25–50% | 2,266 | 10.8 | 12.8 | 20.7 | 55.7 | 13.2 | 76.0 | 25.0 | 63.9 | 20.9 | 37.8 | 30.4 |

| 50–75% | 2,244 | 10.2 | 11.6 | 25.7 | 52.6 | 14.6 | 75.2 | 31.1 | 58.5 | 21.2 | 43.2 | 25.3 |

| Top 25% | 1,942 | 9.8 | 14.3 | 31.3 | 44.7 | 17.7 | 72.5 | 36.5 | 53.5 | 26.8 | 48.7 | 14.6 |

Source. Author’s analysis of data from the 2002–2014 Health and Retirement Study.

Appendix Exhibit A9.

Spousal availability by demographic and socioeconomic status among adults with dementia (Sample: Adults 55+ with dementia, dropping the adults with mismatched information on the number of children; 4,397 persons and 8,269 person-year observations)

| Spouse present |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spouse’s ADL/IADL status |

Spouse’s working status |

|||||

| N. of obs | No spouse (%) | No limitation (%) | At least one limitation (%) | Not working full-time (%) | Working full-time (%) | |

|

| ||||||

| Overall | 8,269 | 60.1 | 25.8 | 14.1 | 36.0 | 3.9 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Men | 3,082 | 37.3 | 41.2 | 21.5 | 56.2 | 6.5 |

| Women | 5,187 | 73.8 | 16.6 | 9.6 | 23.9 | 2.3 |

| Age | ||||||

| 55–64 | 837 | 43.1 | 41.3 | 15.7 | 39.7 | 17.2 |

| 65–74 | 1,641 | 47.3 | 38.0 | 14.7 | 45.7 | 7.0 |

| 75–84 | 2,883 | 56.7 | 28.5 | 14.8 | 42.3 | 1.0 |

| 85+ | 2,908 | 77.2 | 10.4 | 12.4 | 22.7 | 0.2 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| NH White | 4,692 | 58.4 | 27.1 | 14.5 | 38.2 | 3.4 |

| NH Black | 2,123 | 69.0 | 19.8 | 11.2 | 26.4 | 4.6 |

| NH Others | 203 | 58.6 | 27.4 | 14.0 | 35.3 | 6.1 |

| Hispanic | 1,242 | 56.7 | 27.4 | 15.9 | 38.7 | 4.6 |

|

| ||||||

| Education | ||||||

| <12 | 4,669 | 63.9 | 22.6 | 13.5 | 33.3 | 2.8 |

| 12 | 2,075 | 60.1 | 26.9 | 13.0 | 35.6 | 4.3 |

| 13–15 | 894 | 55.7 | 29.2 | 15.1 | 38.1 | 6.2 |

| 16+ | 626 | 43.3 | 37.7 | 19.0 | 50.3 | 6.4 |

| Total wealth | ||||||

| Bottom 25% | 2,455 | 81.7 | 9.4 | 8.9 | 16.5 | 1.8 |

| 25–50% | 2,023 | 63.3 | 22.5 | 14.2 | 33.7 | 3.0 |

| 50–75% | 2,029 | 50.6 | 31.9 | 17.6 | 44.7 | 4.7 |

| Top 25% | 1,762 | 41.3 | 42.4 | 16.3 | 52.2 | 6.4 |

Source. Author’s analysis of data from the 2002–2014 Health and Retirement Study.

Appendix Exhibit A10.

Adult child availability by demographic and socioeconomic status among adults 55+ with dementia, (Sample: Adults 55+ with dementia, dropping the adults with mismatched information on the number of children; 4,397 persons and 8,269 person-year observations)

| Adult child present |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N. of adult children |

Have an adult daughter |

Have a non-full-time-working adult child |

Proximity to adult children |

|||||||||

| N. of obs | No adult child (%) | One (%) | Two (%) | Three or more (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | None within 10 miles (%) | At least one within 10 miles (%) | At least one coresident (%) | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Overall | 8,269 | 3.3 | 14.8 | 26.5 | 55.4 | 16.8 | 79.9 | 32.4 | 64.4 | 24.6 | 45.9 | 26.2 |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Men | 3,082 | 4.9 | 13.0 | 26.3 | 55.8 | 18.0 | 77.1 | 37.8 | 57.3 | 31.1 | 43.1 | 20.8 |

| Women | 5,187 | 2.3 | 15.9 | 26.6 | 55.2 | 16.1 | 81.7 | 29.1 | 68.6 | 20.7 | 47.5 | 29.4 |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 55–64 | 837 | 4.7 | 15.9 | 25.8 | 53.6 | 21.9 | 73.4 | 33.4 | 61.8 | 24.8 | 39.0 | 31.4 |

| 65–74 | 1,641 | 2.9 | 10.7 | 27.5 | 58.9 | 15.1 | 82.0 | 39.4 | 57.7 | 28.6 | 41.7 | 26.8 |

| 75–84 | 2,883 | 2.8 | 13.2 | 24.5 | 59.5 | 14.8 | 82.5 | 37.4 | 59.9 | 23.1 | 48.5 | 25.7 |

| 85 + | 2,908 | 3.5 | 18.3 | 28.3 | 50.0 | 17.9 | 78.6 | 22.9 | 73.7 | 23.9 | 48.1 | 24.5 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| NH White | 4,692 | 2.9 | 15.0 | 31.0 | 51.1 | 18.1 | 79.0 | 35.8 | 61.3 | 27.4 | 49.7 | 19.9 |

| NH Black | 2,123 | 5.1 | 16.1 | 17.8 | 61.1 | 13.8 | 81.1 | 25.6 | 69.3 | 21.0 | 39.8 | 34.1 |

| NH Others | 203 | 1.1 | 20.1 | 28.1 | 50.6 | 24.3 | 74.6 | 33.6 | 65.2 | 21.8 | 37.7 | 39.4 |

| Hispanic | 1,242 | 3.1 | 10.7 | 16.5 | 69.7 | 12.9 | 84.0 | 24.7 | 72.1 | 16.7 | 37.5 | 42.7 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Education | ||||||||||||

| <12 | 4,669 | 2.7 | 14.2 | 20.3 | 62.8 | 15.4 | 81.8 | 25.9 | 71.3 | 22.5 | 44.9 | 29.9 |

| 12 | 2,075 | 3.3 | 16.9 | 33.4 | 46.5 | 17.7 | 79.0 | 38.5 | 58.2 | 24.5 | 49.7 | 22.5 |

| 13–15 | 894 | 4.0 | 14.7 | 31.3 | 50.1 | 19.7 | 76.3 | 39.1 | 56.9 | 26.9 | 46.4 | 22.7 |

| 16+ | 626 | 5.5 | 12.4 | 37.5 | 44.5 | 18.7 | 75.8 | 44.5 | 50.0 | 35.5 | 39.3 | 19.6 |

| Total wealth | ||||||||||||

| Bottom 25% | 2,455 | 4.2 | 17.2 | 22.6 | 56.0 | 17.4 | 78.5 | 29.0 | 66.9 | 24.3 | 42.8 | 28.7 |

| 25–50% | 2,023 | 3.0 | 13.9 | 22.6 | 60.5 | 14.2 | 82.8 | 27.9 | 69.1 | 22.4 | 41.3 | 33.2 |

| 50–75% | 2,029 | 3.0 | 12.6 | 27.8 | 56.7 | 16.4 | 80.7 | 33.9 | 63.1 | 23.2 | 47.2 | 26.6 |

| Top 25% | 1,762 | 2.8 | 15.2 | 33.9 | 48.2 | 19.3 | 77.9 | 39.4 | 57.9 | 28.9 | 52.8 | 15.5 |

Source. Author’s analysis of data from the 2002–2014 Health and Retirement Study.

Appendix Exhibit A11.

Informal and formal ADL help received by adults with dementia, unadjusted (Sample: adults 55+ with dementia and at least one ADL limitation, dropping the adults with mismatched information on the number of children in 2002–2014; 3,005 persons and 5,014 person-year observations)

| Average total hours of help |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of those received care from the given helper type |

including zero hour as well as positive hours |

including positive hours only |

|||||||

| N. of obs | % | 95% CI | N | Mean | 95% CI | N | Mean | 95% CI | |

|

| |||||||||

| ADL care received from: | |||||||||

| Any helper | 4,818 | 80.8 | (79.6, 82.1) | ||||||

| Informal helper | 4,839 | 52.0 | (50.2, 53.7) | 4,839 | 124.5 | (117.6, 131.5) | 2,467 | 239.7 | (229.5, 249.8) |

| - Spouse | 4,960 | 18.9 | (17.3, 20.6) | 4,960 | 46.3 | (40.9, 51.6) | 869 | 244.5 | (230.3, 258.7) |

| - Adult child | 4,939 | 29.0 | (27.3, 30.7) | 4,939 | 44.9 | (41.2, 48.6) | 1,432 | 155.0 | (145.2, 164.9) |

| Formal helper | 4,990 | 43.3 | (41.0, 45.6) | ||||||

| - Nursing home employee | 5,012 | 32.8 | (30.6, 35.0) | ||||||

Source. Author’s analysis of data from the 2002–2014 Health and Retirement Study. Note. Hours from ADL helpers may include IADL help if the ADL helper provide IADL help as well. Hours of help from nursing home employees were not available; accordingly, numbers related to the hours of help from a formal helper were not estimated.

Appendix Exhibit A12.

Spousal availability by demographic and socioeconomic status among adults with dementia (Sample: Adults 55+ with dementia and at least one ADL limitation; 3,390 persons and 5,686 person-year observations)

| Spouse present |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spouse’s ADL/IADL status |

Spouse’s working status |

|||||

| N. of obs | No spouse (%) | No limitation (%) | At least one limitation (%) | Not working full-time (%) | Working full-time (%) | |

|

| ||||||

| Overall | 5,686 | 66.2 | 20.4 | 13.4 | 31.4 | 2.5 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Men | 1,889 | 42.4 | 35.4 | 22.2 | 52.7 | 4.9 |

| Women | 3,797 | 78.2 | 12.8 | 9.0 | 20.5 | 1.3 |

| Age | ||||||

| 55–64 | 403 | 48.2 | 38.0 | 13.8 | 40.2 | 11.7 |

| 65–74 | 954 | 50.0 | 34.0 | 16.0 | 43.8 | 6.2 |

| 75–84 | 1,834 | 60.8 | 23.7 | 15.5 | 38.3 | 0.9 |

| 85+ | 2,495 | 81.2 | 8.1 | 10.7 | 18.7 | 0.1 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| NH White | 3,447 | 65.8 | 20.9 | 13.2 | 32.0 | 2.1 |

| NH Black | 1,324 | 73.1 | 14.8 | 12.1 | 23.8 | 3.1 |

| NH Others | 148 | 61.0 | 23.9 | 15.1 | 36.1 | 3.0 |

| Hispanic | 765 | 59.6 | 24.3 | 16.1 | 36.9 | 3.6 |

|

| ||||||

| Education | ||||||

| <12 | 3,132 | 69.5 | 17.1 | 13.4 | 28.7 | 1.8 |

| 12 | 1,420 | 66.4 | 21.7 | 11.9 | 30.7 | 2.9 |

| 13–15 | 663 | 62.8 | 22.6 | 14.6 | 33.2 | 4.0 |

| 16+ | 468 | 51.1 | 32.6 | 16.3 | 45.8 | 3.1 |

| Total wealth | ||||||

| Bottom 25% | 1,970 | 85.4 | 6.4 | 8.2 | 13.5 | 1.1 |

| 25–50% | 1,362 | 68.5 | 17.4 | 14.1 | 30.0 | 1.5 |

| 50–75% | 1,252 | 54.5 | 28.8 | 16.7 | 42.0 | 3.5 |

| Top 25% | 1,102 | 47.0 | 35.9 | 17.1 | 48.5 | 4.6 |

Source. Author’s analysis of data from the 2002–2014 Health and Retirement Study.

Appendix Exhibit A13.

Adult child availability by demographic and socioeconomic status among adults 55+ with dementia (Sample: Adults 55+ with dementia and at least one ADL limitation; 3,390 persons and 5,686 person-year observations)

| Adult child present |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N. of adult children |

Have an adult daughter |

Have a non-full-time-working adult child |

Proximity to adult children |

|||||||||

| N. of obs | No adult child (%) | One (%) | Two (%) | Three or more (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | None within miles (%) | At least 10 one within 10 miles (%) | At least one coresident (%) | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Overall | 5,686 | 11.0 | 13.8 | 24.8 | 50.5 | 15.3 | 73.6 | 28.0 | 61.0 | 22.4 | 43.0 | 23.6 |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Men | 1,889 | 11.8 | 11.9 | 23.5 | 52.7 | 16.4 | 71.7 | 34.2 | 53.9 | 28.1 | 41.2 | 18.8 |

| Women | 3,797 | 10.6 | 14.7 | 25.4 | 49.3 | 14.8 | 74.6 | 24.8 | 64.6 | 19.4 | 44.0 | 26.0 |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 55–64 | 403 | 13.7 | 12.5 | 23.8 | 50.0 | 18.5 | 67.7 | 30.9 | 55.4 | 21.2 | 41.9 | 23.2 |

| 65–74 | 954 | 9.5 | 11.1 | 25.8 | 53.5 | 14.7 | 75.8 | 35.6 | 54.9 | 28.4 | 37.4 | 24.6 |

| 75–84 | 1,834 | 8.8 | 12.5 | 22.9 | 55.7 | 13.8 | 77.5 | 34.2 | 57.0 | 21.4 | 44.9 | 24.9 |

| 85+ | 2,495 | 12.7 | 16.1 | 26.0 | 45.1 | 16.1 | 71.2 | 19.3 | 68.0 | 20.9 | 44.1 | 22.3 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| NH White | 3,447 | 10.1 | 14.8 | 28.2 | 46.9 | 16.0 | 73.9 | 30.9 | 59.0 | 25.2 | 46.3 | 18.4 |

| NH Black | 1,324 | 14.3 | 12.8 | 16.5 | 56.3 | 13.9 | 71.8 | 19.6 | 66.1 | 17.0 | 36.5 | 32.2 |

| NH Others | 148 | 11.0 | 15.7 | 23.0 | 50.3 | 21.1 | 67.9 | 26.9 | 62.1 | 17.6 | 36.5 | 34.9 |

| Hispanic | 765 | 11.4 | 8.8 | 17.6 | 62.2 | 12.2 | 76.4 | 23.8 | 64.8 | 15.3 | 35.4 | 37.9 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Education | ||||||||||||

| <12 | 3,132 | 11.1 | 12.6 | 19.1 | 57.2 | 14.5 | 74.4 | 21.9 | 67.0 | 21.0 | 41.3 | 26.6 |

| 12 | 1,420 | 11.1 | 16.2 | 30.9 | 41.8 | 14.5 | 74.4 | 33.6 | 55.3 | 22.3 | 45.3 | 21.3 |

| 13–15 | 663 | 11.3 | 15.0 | 26.8 | 46.9 | 19.2 | 69.5 | 34.5 | 54.2 | 20.3 | 48.0 | 20.4 |

| 16+ | 468 | 9.4 | 11.8 | 36.5 | 42.3 | 17.5 | 73.1 | 37.8 | 52.7 | 33.2 | 39.6 | 17.8 |

| Total wealth | ||||||||||||

| Bottom 25% | 1,970 | 14.3 | 15.8 | 20.8 | 49.2 | 15.8 | 70.0 | 25.8 | 59.9 | 22.3 | 39.3 | 24.2 |

| 25–50% | 1,362 | 9.3 | 12.2 | 21.9 | 56.7 | 13.1 | 77.6 | 25.1 | 65.7 | 21.3 | 40.3 | 29.1 |

| 50–75% | 1,252 | 9.8 | 11.5 | 27.4 | 51.3 | 14.5 | 75.7 | 29.0 | 61.2 | 20.0 | 43.3 | 26.9 |

| Top 25% | 1,102 | 9.2 | 14.9 | 31.2 | 44.7 | 18.1 | 72.7 | 33.5 | 57.3 | 26.2 | 51.5 | 13.1 |

Source. Author’s analysis of data from the 2002–2014 Health and Retirement Study.

Appendix Exhibit A14.

Unadjusted informal and formal ADL help received by adults with dementia, stratified by spouse availability (Sample: adults 55+ with dementia and at least one ADL limitation; 3,390 persons and 5,686 person-year observations)

| Average total hours of help |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of those received care from the given helper type |

including zero hour as well as positive hours |

including positive hours only |

||||||||

| By spouse availability | ADL care received from: | N. of obs | % | 95% CI | N | Mean | 95% CI | N | Mean | 95% CI |

|

| ||||||||||

| No spouse | Any helper | 3,671 | 79.7 | (78.0,81.4) | ||||||

| Informal helper | 3,692 | 43.4 | (41.3,45.4) | 3,692 | 95.3 | (88.4,102.3) | 1,616 | 219.8 | (207.6,231.9) | |

| - Spouse | 3,800 | |||||||||

| - Adult child | 3,738 | 30.5 | (28.6,32.4) | 3,738 | 51.9 | (46.4,57.4) | 1,155 | 170.1 | (157.4,182.9) | |

| Formal helper | 3,777 | 51.1 | (48.5,53.8) | |||||||

| - Nursing home employee | 3,799 | 40.5 | (38.1,42.8) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| With spouse | Any helper | 1,800 | 82.0 | (79.7,84.3) | ||||||

| Informal helper | 1,804 | 63.7 | (61.2,66.2) | 1,804 | 170.5 | (157.7,183.3) | 1,116 | 267.7 | (251.8,283.6) | |

| - Spouse | 1,827 | 53.4 | (50.4,56.4) | 1,827 | 130.5 | (118.0,143.0) | 931 | 244.5 | (230.6,258.3) | |

| - Adult child | 1,869 | 18.9 | (16.5,21.3) | 1,869 | 21.6 | (17.3,26.0) | 348 | 114.5 | (95.6,133.4) | |

| Formal helper | 1,880 | 31.1 | (28.4,33.8) | |||||||

| - Nursing home employee | 1,884 | 21.0 | (18.4,23.6) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| No limitation | Any helper | 1,065 | 82.4 | (79.4,85.5) | ||||||

| Informal helper | 1,068 | 67.2 | (63.6,70.9) | 1,068 | 185.5 | (166.9,204.1) | 700 | 276.0 | (254.9,297.1) | |

| - Spouse | 1,077 | 62.4 | (58.8,66.0) | 1,077 | 156.4 | (139.5,173.2) | 652 | 250.7 | (233.8,267.5) | |

| - Adult child | 1,106 | 16.9 | (13.6,20.3) | 1,106 | 16.3 | (10.7,21.9) | 182 | 96.3 | (66.9,125.7) | |

| Formal helper | 1,108 | 27.3 | (24.0,30.6) | |||||||

| - Nursing home employee | 1,111 | 19.1 | (15.6,22.7) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| At least one limitation | Any helper | 735 | 81.3 | (77.3,85.3) | ||||||

| Informal helper | 736 | 58.3 | (54.7,61.9) | 736 | 147.5 | (128.3,166.7) | 416 | 253.0 | (226.3,279.7) | |

| - Spouse | 750 | 39.7 | (35.2,44.3) | 750 | 91.3 | (74.5,108.1) | 279 | 229.8 | (207.5,252.0) | |

| - Adult child | 763 | 22.0 | (19.1,24.9) | 763 | 29.9 | (21.9,37.9) | 166 | 136.0 | (115.2,156.9) | |

| Formal helper | 772 | 36.9 | (31.8,42.0) | |||||||

| - Nursing home employee | 773 | 23.9 | (18.9,28.8) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Not working full-time | Any helper | 1,687 | 83.2 | (80.7,85.8) | ||||||

| Informal helper | 1,691 | 64.0 | (61.3,66.6) | 1,691 | 172.1 | (158.7,185.4) | 1,054 | 269.0 | (252.0,286.0) | |

| - Spouse | 1,712 | 53.4 | (50.3,56.4) | 1,712 | 131.4 | (118.6,144.2) | 873 | 246.3 | (231.9,260.6) | |

| - Adult child | 1,748 | 18.7 | (16.5,21.0) | 1,748 | 21.7 | (17.1,26.2) | 326 | 115.7 | (94.5,137.0) | |

| Formal helper | 1,758 | 32.3 | (29.6,34.9) | |||||||

| - Nursing home employee | 1,762 | 21.9 | (19.2,24.5) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Working full-time | Any helper | 113 | 65.5 | (56.5,74.5) | ||||||

| Informal helper | 113 | 60.2 | (50.4,70.0) | 113 | 149.7 | (96.1,203.4) | 62 | 248.8 | (229.3,268.3) | |

| - Spouse | 115 | 53.5 | (41.3,65.8) | 115 | 118.4 | (69.0,167.9) | 58 | 221.3 | (202.5,240.1) | |

| - Adult child | 121 | 21.3 | (9.3,33.2) | 121 | 21.5 | (8.7,34.3) | 22 | 101.1 | (58.6,143.7) | |

| Formal helper | 122 | 16.6 | (8.9,24.4) | |||||||

| - Nursing home employee | 122 | 10.0 | (4.0,16.1) | |||||||

Source. Author’s analysis of data from the 2002–2014 Health and Retirement Study. Note. Hours from ADL helpers may include IADL help if the ADL helper provide IADL help as well. Hours of help from nursing home employee were not available; accordingly, numbers related to the hours of help from a formal helper were not estimated.

Appendix Exhibit A15.

Unadjusted informal and formal ADL help received by adults with dementia, stratified by adult child availability (Sample: adults 55+ with dementia and at least one ADL limitation; 3,390 persons and 5,686 person-year observations)

| Average total hours of help |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of those received care from the given helper type |

including zero hour as well as positive hours |

including positive hours only |

||||||||

| By child availability | ADL care received from: | N. of obs | % | 95% CI | N | Mean | 95% CI | N | Mean | 95% CI |

|

| ||||||||||

| No adult bio child | Any helper | 625 | 76.6 | (72.4,80.9) | ||||||

| Informal helper | 629 | 31.0 | (25.5,36.4) | 629 | 69.2 | (51.4,87.0) | 212 | 223.4 | (204.6,242.2) | |

| - Spouse | 639 | 7.1 | (4.1,10.0) | 639 | 15.5 | (6.6,24.5) | 51 | 220.0 | (193.0,247.0) | |

| - Adult child | 642 | |||||||||

| Formal helper | 637 | 58.3 | (53.6,63.0) | |||||||

| - Nursing home employee | 641 | 47.2 | (41.1,53.3) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Have at least one adult bio child | Any helper | 4,846 | 81.0 | (79.6,82.3) | ||||||

| Informal helper | 4,867 | 52.6 | (50.9,54.3) | 4,867 | 127.0 | (120.3,133.7) | 2,520 | 241.4 | (231.3,251.5) | |

| - Spouse | 4,988 | 19.0 | (17.4,20.7) | 4,988 | 46.8 | (41.4,52.1) | 880 | 245.6 | (231.5,259.7) | |

| - Adult child | 4,965 | 29.9 | (28.2,31.6) | 4,965 | 46.8 | (42.9,50.7) | 1,503 | 156.7 | (146.6,166.8) | |

| Formal helper | 5,020 | 42.6 | (40.4,44.9) | |||||||

| - Nursing home employee | 5,042 | 32.2 | (30.1,34.3) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 1 adult bio child | Any helper | 764 | 80.2 | (75.2,85.2) | ||||||

| Informal helper | 769 | 46.8 | (42.4,51.2) | 769 | 106.1 | (87.8,124.4) | 343 | 226.8 | (198.5,255.0) | |

| - Spouse | 784 | 14.1 | (10.6,17.6) | 784 | 32.5 | (23.6,41.4) | 95 | 230.2 | (190.4,270.1) | |

| - Adult child | 784 | 21.0 | (17.1,24.9) | 784 | 29.0 | (21.1,36.9) | 164 | 138.1 | (113.6,162.6) | |

| Formal helper | 785 | 46.3 | (40.7,51.9) | |||||||

| - Nursing home employee | 789 | 38.1 | (33.7,42.4) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 2 adult bio children | Any helper | 1,292 | 81.0 | (78.4,83.6) | ||||||

| Informal helper | 1,296 | 50.9 | (47.7,54.1) | 1,296 | 114.3 | (100.8,127.8) | 635 | 224.7 | (205.1,244.3) | |

| - Spouse | 1,327 | 19.7 | (16.7,22.7) | 1,327 | 50.0 | (39.4,60.6) | 232 | 253.6 | (221.3,285.9) | |

| - Adult child | 1,329 | 26.8 | (23.6,30.0) | 1,329 | 35.4 | (29.6,41.2) | 357 | 131.9 | (118.3,145.6) | |

| Formal helper | 1,339 | 43.6 | (40.5,46.8) | |||||||

| - Nursing home employee | 1,344 | 35.7 | (32.5,39.0) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 3+ adult bio children | Any helper | 2,790 | 81.1 | (79.4,82.9) | ||||||

| Informal helper | 2,802 | 55.1 | (52.7,57.4) | 2,802 | 139.0 | (128.6,149.4) | 1,542 | 252.4 | (237.6,267.2) | |

| - Spouse | 2,877 | 20.1 | (18.0,22.2) | 2,877 | 49.1 | (42.2,56.0) | 553 | 244.7 | (225.3,264.2) | |

| - Adult child | 2,852 | 33.9 | (31.5,36.2) | 2,852 | 57.4 | (51.6,63.3) | 982 | 169.5 | (156.1,182.9) | |

| Formal helper | 2,896 | 41.1 | (38.1,44.2) | |||||||

| - Nursing home employee | 2,909 | 28.9 | (26.1,31.8) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| No adult bio daughter | Any helper | 853 | 81.1 | (78.3,83.9) | ||||||

| Informal helper | 855 | 48.7 | (44.0,53.4) | 855 | 109.3 | (93.0,125.6) | 382 | 224.5 | (201.4,247.7) | |

| - Spouse | 876 | 19.6 | (14.6,24.6) | 876 | 43.4 | (30.6,56.3) | 147 | 222.1 | (206.1,238.1) | |

| - Adult child | 877 | 17.8 | (13.7,21.8) | 877 | 24.1 | (14.2,34.0) | 148 | 135.9 | (100.0,171.7) | |

| Formal helper | 883 | 43.8 | (39.7,47.8) | |||||||

| - Nursing home employee | 885 | 34.5 | (30.3,38.6) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Have at least one adult bio daughter | Any helper | 3,993 | 80.9 | (79.3,82.6) | ||||||

| Informal helper | 4,012 | 53.4 | (51.3,55.5) | 4,012 | 130.6 | (121.9,139.4) | 2,138 | 244.6 | (232.2,257.0) | |

| - Spouse | 4,112 | 18.9 | (17.2,20.7) | 4,112 | 47.5 | (41.6,53.4) | 733 | 250.7 | (234.0,267.3) | |

| - Adult child | 4,088 | 32.4 | (30.6,34.3) | 4,088 | 51.6 | (46.9,56.3) | 1,355 | 159.1 | (148.4,169.7) | |

| Formal helper | 4,137 | 42.4 | (39.7,45.1) | |||||||

| - Nursing home employee | 4,157 | 31.8 | (29.3,34.3) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| No non-full-time-working adult child | Any helper | 1,464 | 79.3 | (76.2,82.4) | ||||||

| Informal helper | 1,472 | 50.1 | (47.1,53.1) | 1,472 | 110.3 | (99.0,121.7) | 729 | 220.2 | (203.7,236.6) | |

| - Spouse | 1,500 | 24.0 | (21.0,26.9) | 1,500 | 54.6 | (47.5,61.7) | 349 | 228.0 | (207.1,248.8) | |

| - Adult child | 1,506 | 21.8 | (18.8,24.8) | 1,506 | 23.5 | (19.0,28.0) | 333 | 107.9 | (91.5,124.3) | |

| Formal helper | 1,514 | 43.6 | (40.1,47.1) | |||||||

| - Nursing home employee | 1,522 | 33.9 | (31.0,36.7) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Have at least one non-full-time-working adult child | Any helper | 3,382 | 81.7 | (79.8,83.7) | ||||||

| Informal helper | 3,395 | 53.7 | (51.2,56.3) | 3,395 | 134.6 | (125.5,143.7) | 1,791 | 250.5 | (237.1,263.9) | |

| - Spouse | 3,488 | 16.8 | (14.8,18.8) | 3,488 | 43.2 | (36.4,50.0) | 531 | 257.1 | (237.1,277.1) | |

| - Adult child | 3,459 | 33.6 | (31.3,35.9) | 3,459 | 57.6 | (52.4,62.9) | 1,170 | 171.3 | (160.4,182.1) | |

| Formal helper | 3,506 | 42.2 | (39.5,44.9) | |||||||

| - Nursing home employee | 3,520 | 31.5 | (28.9,34.1) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| No adult child living within 10 miles | Any helper | 1,222 | 79.1 | (75.6,82.6) | ||||||

| Informal helper | 1,232 | 43.2 | (40.1,46.3) | 1,232 | 87.3 | (76.0,98.5) | 504 | 202.1 | (183.8,220.4) | |

| - Spouse | 1,240 | 22.9 | (20.1,25.6) | 1,240 | 53.1 | (44.3,61.8) | 264 | 232.2 | (212.4,252.0) | |

| - Adult child | 1,245 | 10.8 | (8.6,13.0) | 1,245 | 7.0 | (4.8,9.1) | 131 | 64.3 | (48.9,79.7) | |

| Formal helper | 1,238 | 49.5 | (44.7,54.2) | |||||||

| - Nursing home employee | 1,248 | 41.9 | (37.2,46.6) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| No adult child coresident but at least one within 10 miles | Any helper | 2,253 | 81.5 | (79.6,83.4) | ||||||

| Informal helper | 2,262 | 47.9 | (45.3,50.6) | 2,262 | 103.6 | (91.8,115.5) | 1,064 | 216.3 | (194.8,237.7) | |

| - Spouse | 2,306 | 19.3 | (16.8,21.8) | 2,306 | 48.4 | (40.4,56.5) | 418 | 251.2 | (227.6,274.8) | |

| - Adult child | 2,312 | 25.7 | (23.5,28.0) | 2,312 | 26.1 | (22.0,30.3) | 582 | 101.6 | (87.5,115.7) | |

| Formal helper | 2,327 | 48.9 | (46.0,51.9) | |||||||

| - Nursing home employee | 2,336 | 39.1 | (36.3,41.8) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| At least one adult child coresident | Any helper | 1,371 | 81.7 | (78.8,84.6) | ||||||

| Informal helper | 1,373 | 70.7 | (67.3,74.0) | 1,373 | 210.0 | (194.8,225.1) | 952 | 297.0 | (279.8,314.2) | |

| - Spouse | 1,442 | 15.0 | (12.1,17.9) | 1,442 | 37.8 | (29.4,46.2) | 198 | 252.0 | (228.6,275.3) | |

| - Adult child | 1,408 | 56.3 | (53.0,59.7) | 1,408 | 124.5 | (112.6,136.4) | 790 | 221.0 | (204.1,237.9) | |

| Formal helper | 1,455 | 24.7 | (21.7,27.7) | |||||||

| - Nursing home employee | 1,458 | 10.7 | (8.8,12.6) | |||||||

Source. Author’s analysis of data from the 2002–2014 Health and Retirement Study. Note. Hours from ADL helpers may include IADL help if the ADL helper provide IADL help as well. Hours of help from nursing home employee were not available; accordingly, numbers related to the hours of help from a formal helper were not estimated.

Appendix Exhibit A16.

Spousal availability by demographic and socioeconomic status among adults with dementia (Sample: Adults 55+ with dementia and at least one ADL limitation who were community-dwelling at the previous interview; 2,852 persons and 4,259 person-year observations)

| Spouse present |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spouse’s ADL/IADL status |

Spouse’s working status |

|||||

| N. of obs | No spouse (%) | No limitation (%) | At least one limitation (%) | Not working full-time (%) | Working full-time (%) | |

|

| ||||||

| Overall | 4,259 | 62.0 | 23.5 | 14.5 | 35.2 | 2.8 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Men | 1,525 | 37.5 | 39.2 | 23.3 | 57.4 | 5.2 |

| Women | 2,734 | 75.7 | 14.7 | 9.6 | 22.8 | 1.5 |

| Age | ||||||

| 55–64 | 328 | 46.7 | 40.0 | 13.3 | 41.1 | 12.1 |

| 65–74 | 765 | 46.0 | 37.2 | 16.9 | 47.3 | 6.8 |

| 75–84 | 1,462 | 56.7 | 26.8 | 16.5 | 42.3 | 0.9 |

| 85+ | 1,704 | 78.0 | 10.0 | 12.0 | 21.9 | 0.1 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| NH White | 2,447 | 60.0 | 25.5 | 14.4 | 37.4 | 2.5 |

| NH Black | 1,063 | 71.7 | 15.8 | 12.5 | 25.3 | 3.0 |

| NH Others | 114 | 62.1 | 22.4 | 15.6 | 34.0 | 3.9 |

| Hispanic | 634 | 58.5 | 24.2 | 17.3 | 37.9 | 3.6 |

|

| ||||||

| Education | ||||||

| <12 | 2,469 | 66.2 | 19.0 | 14.9 | 31.9 | 1.9 |

| 12 | 978 | 61.3 | 26.3 | 12.4 | 35.1 | 3.5 |

| 13–15 | 472 | 56.6 | 27.1 | 16.3 | 38.8 | 4.6 |

| 16+ | 338 | 45.2 | 39.1 | 15.7 | 51.0 | 3.7 |

| Total wealth | ||||||

| Bottom 25% | 1,321 | 81.1 | 8.4 | 10.5 | 17.5 | 1.5 |

| 25–50% | 1,045 | 65.3 | 19.0 | 15.7 | 33.1 | 1.5 |

| 50–75% | 1,022 | 53.2 | 30.9 | 15.9 | 43.1 | 3.7 |

| Top 25% | 871 | 43.5 | 39.6 | 16.9 | 51.6 | 4.9 |

Source. Author’s analysis of data from the 2002–2014 Health and Retirement Study.

Appendix Exhibit A17.

Adult child availability by demographic and socioeconomic status among adults 55+ with dementia (Sample: Adults 55+ with dementia and at least one ADL limitation who were community-dwelling at the previous interview; 2,852 persons and 4,259 person-year observations)

| Adult child present |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N. of adult children |

Have an adult daughter |

Have a non-full-time-working adult child |

Proximity to adult children |

|||||||||

| N. of obs | No adult child (%) | One (%) | Two(%) | Three or more (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | None within 10 miles (%) | At least one within 10 miles (%) | At least one coresident (%) | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Overall | 4,259 | 9.4 | 13.2 | 24.4 | 53.0 | 14.8 | 75.8 | 28.2 | 62.4 | 20.9 | 41.7 | 28.0 |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Men | 1,525 | 10.1 | 11.6 | 23.5 | 54.7 | 15.7 | 74.2 | 34.5 | 55.4 | 27.1 | 42.0 | 20.7 |

| Women | 2,734 | 9.0 | 14.1 | 24.9 | 52.0 | 14.4 | 76.6 | 24.6 | 66.4 | 17.5 | 41.5 | 32.1 |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 55–64 | 328 | 12.3 | 12.2 | 23.5 | 51.9 | 18.1 | 69.6 | 33.4 | 54.2 | 22.3 | 40.6 | 24.7 |

| 65–74 | 765 | 7.9 | 10.2 | 25.3 | 56.6 | 14.3 | 77.8 | 33.5 | 58.6 | 27.8 | 37.4 | 27.0 |

| 75–84 | 1,462 | 8.2 | 12.0 | 23.3 | 56.4 | 13.4 | 78.3 | 33.7 | 58.0 | 19.9 | 43.1 | 28.8 |

| 85+ | 1,704 | 10.3 | 15.8 | 25.3 | 48.6 | 15.4 | 74.3 | 19.4 | 70.3 | 18.4 | 42.6 | 28.6 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| NH White | 2,447 | 8.7 | 13.9 | 28.3 | 49.0 | 15.5 | 75.8 | 31.4 | 59.9 | 23.6 | 45.1 | 22.5 |

| NH Black | 1,063 | 11.4 | 13.0 | 15.6 | 59.9 | 12.7 | 75.9 | 20.2 | 68.4 | 15.3 | 36.4 | 36.9 |

| NH Others | 114 | 10.2 | 17.5 | 22.4 | 49.9 | 20.0 | 69.8 | 27.1 | 62.7 | 21.5 | 32.0 | 36.3 |

| Hispanic | 634 | 9.9 | 8.9 | 17.5 | 63.6 | 13.1 | 77.0 | 23.6 | 66.5 | 15.3 | 34.4 | 40.4 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Education | ||||||||||||

| <12 | 2,469 | 9.8 | 11.7 | 18.9 | 59.6 | 14.3 | 75.9 | 21.9 | 68.2 | 18.6 | 40.6 | 31.0 |

| 12 | 978 | 8.9 | 17.1 | 31.9 | 42.1 | 13.6 | 77.5 | 34.0 | 57.1 | 21.6 | 42.6 | 26.8 |

| 13–15 | 472 | 8.1 | 14.2 | 27.1 | 50.7 | 18.8 | 73.1 | 36.6 | 55.3 | 20.2 | 47.2 | 24.5 |

| 16+ | 338 | 9.1 | 10.3 | 34.7 | 45.9 | 16.6 | 74.3 | 39.5 | 51.4 | 35.0 | 38.3 | 17.6 |

| Total wealth | ||||||||||||

| Bottom 25% | 1,321 | 11.8 | 14.9 | 19.8 | 53.6 | 14.7 | 73.5 | 24.3 | 63.9 | 18.8 | 36.8 | 32.7 |

| 25–50% | 1,045 | 7.9 | 11.5 | 21.1 | 59.5 | 13.9 | 78.2 | 25.0 | 67.1 | 20.1 | 37.6 | 34.4 |

| 50–75% | 1,022 | 9.2 | 11.9 | 27.3 | 51.6 | 14.2 | 76.5 | 30.1 | 60.7 | 19.1 | 42.7 | 29.0 |

| Top 25% | 871 | 8.2 | 14.3 | 30.7 | 46.8 | 16.6 | 75.2 | 34.3 | 57.6 | 26.7 | 51.1 | 14.0 |

Source. Author’s analysis of data from the 2002–2014 Health and Retirement Study.

Appendix Exhibit A18.