Abstract

Background

Medical professionals routinely carry out surgical hand antisepsis before undertaking invasive procedures to destroy transient micro‐organisms and inhibit the growth of resident micro‐organisms. Antisepsis may reduce the risk of surgical site infections (SSIs) in patients.

Objectives

To assess the effects of surgical hand antisepsis on preventing surgical site infections (SSIs) in patients treated in any setting. The secondary objective is to determine the effects of surgical hand antisepsis on the numbers of colony‐forming units (CFUs) of bacteria on the hands of the surgical team.

Search methods

In June 2015 for this update, we searched: The Cochrane Wounds Group Specialized Register; The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library); Ovid MEDLINE; Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations) and EBSCO CINAHL. There were no restrictions with respect to language, date of publication or study setting.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials comparing surgical hand antisepsis of varying duration, methods and antiseptic solutions.

Data collection and analysis

Three authors independently assessed studies for inclusion and trial quality and extracted data.

Main results

Fourteen trials were included in the updated review. Four trials reported the primary outcome, rates of SSIs, while 10 trials reported number of CFUs but not SSI rates. In general studies were small, and some did not present data or analyses that could be easily interpreted or related to clinical outcomes. These factors reduced the quality of the evidence.

SSIs

One study randomised 3317 participants to basic hand hygiene (soap and water) versus an alcohol rub plus additional hydrogen peroxide. There was no clear evidence of a difference in the risk of SSI (risk ratio (RR) 0.97, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.23, moderate quality evidence downgraded for imprecision).

One study (500 participants) compared alcohol‐only rub versus an aqueous scrub and found no clear evidence of a difference in the risk of SSI (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.23 to 1.34, very low quality evidence downgraded for imprecision and risk of bias).

One study (4387 participants) compared alcohol rubs with additional active ingredients versus aqueous scrubs and found no clear evidence of a difference in SSI (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.48, low quality evidence downgraded for imprecision and risk of bias).

One study (100 participants) compared an alcohol rub with an additional ingredient versus an aqueous scrub with a brush and found no evidence of a difference in SSI (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.05 to 5.34, low quality evidence downgraded for imprecision).

CFUs

The review presents results for a number of comparisons; key findings include the following.

Four studies compared different aqueous scrubs in reducing CFUs on hands.Three studies found chlorhexidine gluconate scrubs resulted in fewer CFUs than povidone iodine scrubs immediately after scrubbing, 2 hours after the initial scrub and 2 hours after subsequent scrubbing. All evidence was low or very low quality, with downgrading typically for imprecision and indirectness of outcome. One trial comparing a chlorhexidine gluconate scrub versus a povidone iodine plus triclosan scrub found no clear evidence of a difference—this was very low quality evidence (downgraded for risk of bias, imprecision and indirectness of outcome).

Four studies compared aqueous scrubs versus alcohol rubs containing additional active ingredients and reported CFUs. In three comparisons there was evidence of fewer CFUs after using alcohol rubs with additional active ingredients (moderate or very low quality evidence downgraded for imprecision and indirectness of outcome). Evidence from one study suggested that an aqueous scrub was more effective in reducing CFUs than an alcohol rub containing additional ingredients, but this was very low quality evidence downgraded for imprecision and indirectness of outcome.

Evidence for the effectiveness of different scrub durations varied. Four studies compared the effect of different durations of scrubs and rubs on the number of CFUs on hands. There was evidence that a 3 minute scrub reduced the number of CFUs compared with a 2 minute scrub (very low quality evidence downgraded for imprecision and indirectness of outcome). Data on other comparisons were not consistent, and interpretation was difficult. All further evidence was low or very low quality (typically downgraded for imprecision and indirectness).

One study compared the effectiveness of using nail brushes and nail picks under running water prior to a chlorhexidine scrub on the number of CFUs on hands. It was unclear whether there was a difference in the effectiveness of these different techniques in terms of the number of CFUs remaining on hands (very low quality evidence downgraded due to imprecision and indirectness).

Authors' conclusions

There is no firm evidence that one type of hand antisepsis is better than another in reducing SSIs. Chlorhexidine gluconate scrubs may reduce the number of CFUs on hands compared with povidone iodine scrubs; however, the clinical relevance of this surrogate outcome is unclear. Alcohol rubs with additional antiseptic ingredients may reduce CFUs compared with aqueous scrubs. With regard to duration of hand antisepsis, a 3 minute initial scrub reduced CFUs on the hand compared with a 2 minute scrub, but this was very low quality evidence, and findings about a longer initial scrub and subsequent scrub durations are not consistent. It is unclear whether nail picks and brushes have a differential impact on the number of CFUs remaining on the hand. Generally, almost all evidence available to inform decisions about hand antisepsis approaches that were explored here were informed by low or very low quality evidence.

Keywords: Humans; General Surgery; Anti‐Infective Agents, Local; Anti‐Infective Agents, Local/administration & dosage; Antisepsis; Antisepsis/methods; Colony Count, Microbial; Hand; Hand/microbiology; Hand Disinfection; Hand Disinfection/methods; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Surgical Wound Infection; Surgical Wound Infection/epidemiology; Surgical Wound Infection/prevention & control

Plain language summary

Surgical hand antisepsis to reduce surgical site infection

What are surgical site infections and who is at risk?

The inadvertent transfer of micro‐organisms such as bacteria to a patient's wound site during surgery can result in a wound infection that is commonly called a surgical site infection (SSI). SSIs are one of the most common forms of health care‐associated infections for surgical patients. Around 1 in 20 surgical patients develop an SSI in hospital, and this proportion rises when people go home. SSIs result in delayed wound healing, increased hospital stays, increased use of antibiotics, unnecessary pain and, in extreme cases, the death of the patient, so their prevention is a key aim for health services.

Why use hand antisepsis prior to surgery?

There are many different points in the care pathway where prevention of SSIs can take place. This includes antiseptic cleansing of the hands for those who are operating on the patient. Surgical hand antisepsis is the focus of this review. The two most common forms of hand antisepsis involve aqueous scrubs and alcohol rubs. Aqueous scrubs are water‐based solutions containing antiseptic ingredients such as chlorhexidine gluconate or povidone iodine. Scrubbing involves wetting the hands and forearms with water, systematically applying an aqueous scrub solution using either hands or sponges, rinsing under running water and then repeating this process. Alcohol solutions containing additional active ingredients are used to perform an 'alcohol rub'. Surgical teams systematically apply the alcohol rub solutions to their hands and allow it to evaporate. Alcohol is effective against a wide range of bacteria and other micro‐organisms. Following hand antisepsis, operating staff then put on gloves, which provide an important barrier between operating staff and the patient; however, because gloves can become perforated during surgery, it is necessary to have hands as germ‐free as possible.

What we found

In June 2015 we searched for as many relevant studies that had a robust design (randomised controlled trials) as we could find and compared different types of hand antisepsis before surgery. We included 14 studies that compared a range of methods for performing surgical hand antisepsis. The two measures used to assess the effectiveness of treatments were the number of cases of SSIs in patients (presented in four included studies) and the number of viable bacteria or fungal cells (known as colony‐forming units, or CFUs) on the hand of the person operating before surgery and after surgery (which is a way of counting the bacteria present on the skin surface). It is not clear whether the method of hand antisepsis influences the risk of SSI, as most of the studies were too small and had flaws. There was some evidence that hand antisepsis with chlorhexidine may reduce the number of bacteria on the hands of health professionals compared with povidone iodine. Importantly, we do not know what the number of CFUs on the hands tells us about the likelihood of patients developing SSIs. There was also some evidence that alcohol rubs with additional antiseptic ingredients may reduce CFUs compared with aqueous scrubs.

Up‐to‐date June 2015

Background

The inadvertent transfer of micro‐organisms to patients' wound sites during surgery can result in postoperative surgical site infections (SSIs). SSIs are one of the most common forms of healthcare‐associated infections for surgical patients (NICE 2008). Around 5% of surgical patients develop an SSI (NICE 2008), though this incidence can double when surveillance includes active postdischarge follow‐up (Leaper 2015). SSIs result in delayed wound healing, increased hospital stays, increased use of antibiotics, unnecessary pain and, in extreme cases, the death of the patient (Plowman 2000).

Micro‐organisms that cause SSIs come from a variety of sources within the operating room, including the hands of the surgical team. Members of the surgical team wear sterile gloves to prevent transferring bacteria from their hands to patients. However, gloves can become perforated during surgery, so it is necessary to have hands as germ‐free as possible. This is achieved by conducting surgical hand antisepsis immediately before donning sterile gloves prior to commencing surgical or invasive procedures. While handwashing removes transient micro‐organisms, surgical hand antisepsis goes a step further to inhibit the growth of resident microorganisms, thereby minimising the risk of a patient developing an SSI (WHO 2009).This is achieved using antiseptic agents that kill and inhibit bacteria, fungi, protozoa and bacterial spores. An ideal antiseptic agent would be fast‐acting, persistent (effective for a number of hours), cumulative (repeated exposure inhibits bacterial growth for a number of days), have a broad spectrum of activity and be safe to use.There are several individual components of surgical hand antisepsis, including the pre‐wash; the application technique; the use of sponges, brushes or nail picks; the choice of antiseptic solution and the duration of the antisepsis.

Defining terms ‐ scrub and rubs

Several different terms are used when describing surgical hand antisepsis. Antisepsis with running water and an aqueous solution is referred to as a surgical or a traditional scrub. Antisepsis with an alcohol solution is referred to as an alcohol rub or a waterless scrub. In this review, we understand surgical hand antisepsis to encompass both methods of surgical antisepsis: scrubbing and rubbing. The very first antisepsis of the day is referred to as the initial antisepsis. Scrubs or rubs performed thereafter but on the same day are referred to as subsequent antisepses.

Surgical hand antisepsis ‐ current practice

The Association for Perioperative Practice (AfPP) recommends a pre‐wash prior to the first antisepsis of the day, when hands are washed with soap or an antimicrobial solution under running water (AfPP 2011). The function of the pre‐wash is to remove dirt (organic material). AfPP 2011 then recommends cleaning nails using a pick under running water. Clinicians can then perform antisepsis using either an antimicrobial solution with running water, referred to as a traditional scrub, or an alcoholic rub without water. AfPP 2011 suggests alcohol rubs are more effective in reducing bacteria on the skin but should not be used if there is visible dirt present. The AfPP does not cite any specific antimicrobial solution as being the most effective, but, like many other organisations, recommends that the solution chosen meets the ideal properties for an antimicrobial solution (ACORN 2012; AORN 2010; WHO 2009). These properties are identified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as the solution being:

fast‐acting;

persistent (effective for a number of hours);

cumulative (repeated exposure inhibits bacterial growth for a number of days);

having a broad spectrum of activity; and

safe to use (CDC 2002).

AfPP 2011 recommends a duration of 2 to 5 minutes (depending on manufacturers instructions) for a traditional scrub, but does not provide details on the recommended duration of an alcoholic rub. There is some discrepancy regarding aspects of hand antisepsis between different organisations. For example, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Australian College of Operating Room Nurses (ACORN) only recommend a pre‐wash if hands are visibly dirty (ACORN 2012; WHO 2009), and ACORN 2012 recommends that the first scrub of the day last 5 minutes while subsequent scrubs last 3 minutes. Nail brushes no longer appear to be recommended as these can damage skin (ACORN 2012; AfPP 2011; AORN 2010; WHO 2009).

Guidelines for surgical antisepsis also cover topics such as rings, artificial nails and nail polish (AORN 2010; ACORN 2012; AfPP 2011; HIS 2001; Mangram 1999). The impact of these factors on SSI is the focus of another Cochrane review (Arrowsmith 2014). There are concerns that hand antisepsis causes skin damage to staff hands and that some products are more abrasive than others (Larson 1986b). This topic is outside the remit of this review.

Surgical hand antisepsis solutions

Solutions for hand antisepsis are either aqueous (water) based or alcohol based.

Aqueous scrubs

Aqueous scrubs are water based solutions containing active ingredients that are used during traditional handscrubs. The most common solutions contain chlorhexidine gluconate or povidone iodine (see below). Scrubbing involves wetting the hands and forearms with water, systematically applying an aqueous scrub solution using either hands or sponges, rinsing under running water and then repeating the process.

Alcohol rubs

Alcohol‐based solutions are used to perform an 'alcohol rub'. Health professionals apply the solution to dry hands and then rub them together systematically before allowing the solution to evaporate. Alcohol rubs do not require water for their application. Some alcohol rub solutions contain additional active antiseptic agents.

Antiseptic agents

Alcohol

Alcohols have little or no residual effect, and the concentration rather than the type of alcohol is thought to be most important in determining its effectiveness (Larson 1995). Alcohol rubs are usually available in preparations of 60% to 90% strength and are effective against a wide range of gram‐positive and gram negative bacteria, mycobacterium tuberculosis, and many fungi and viruses. The three main alcohols used are ethanol, isopropanol and n‐propanol, and some rubs may contain a mixture of these. Compared with other common antiseptic products, alcohol is associated with the most rapid and greatest reduction in microbial counts (Lowbury 1974a), but it does not remove surface dirt as it does not contain surfactants or have a foaming action (Hobson 1998). Alcohol‐based solutions usually (but not always) contain additional active ingredients to combine the rapid bacteriocidal effect of alcohol with more persistent chemical activity.

Iodine and iodophors

Iodine has mostly been replaced by iodophors, as iodine often causes irritation and discolouring of skin. Iodophors are composed of elemental iodine, iodide or triiodide, and a polymer carrier of high molecular weight (WHO 2009). Combining iodine with various polymers increases the solubility of iodine, promotes sustained release of iodine and reduces skin irritation. Iodophors are effective against a wide range of gram‐positive and gram negative bacteria, mycobacterium tuberculosis, fungi and viruses (Joress 1962). Iodophors contain iodine with a carrier such as polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP). PVP, also known as povidone, is a polymer that detoxifies and prolongs the activities of drugs. PVP prolongs the activity of iodine by releasing it slowly. A combination of PVP and iodine, known as povidone iodine (PI), is less irritating than earlier solutions of iodine tincture (Joress 1962). Iodophors rapidly reduce transient and colonising bacteria but have little or no residual effect (Larson 1990).

Chlorhexidine

Chlorhexidine is a biguanide. It is effective against a wide range of gram‐positive and gram‐negative bacteria, lipophilic viruses and yeasts (Hibbard 2002a). It is not sporicidal. Although its immediate antimicrobial activity is slower than that of alcohols, it is more persistent because it binds to the outermost layer of skin, the stratum corneum (Larson 1990). Over time, repeated exposure can lead to a cumulative effect where both transient and resident organisms are reduced (Larson 1990). Chlorhexidine gluconate is effective in the presence of blood and other protein‐rich biological materials (Hibbard 2002a).

Quaternary ammonium compounds

Quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs) are composed of a nitrogen atom linked to four alkyl groups. Alkyl benzalkonium chlorides are the most widely used as antiseptics, though other compounds include benzethonium chloride, cetrimide and cetylpyridium chloride. QACs are primarily bacteriostatic and fungistatic, although they are microbicidal against some organisms at high concentrations.They are more active against gram‐positive bacteria than against gram‐negative bacilli. QACs have relatively weak activity against mycobacteria and fungi and greater activity against lipophilic viruses. Their antimicrobial activity is adversely affected by the presence of organic material, and they are not compatible with anionic detergents. In 1994, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Tentative Final Monograph (TFM) tentatively classified benzalkonium chloride and benzethonium chloride as having insufficient data to classify as safe and effective for use as an antiseptic handwash (WHO 2009).

Hexachlorophene

Hexachlorophene is a halophenol compound. It is a slow‐acting antiseptic that forms a film over the skin (Crowder 1967). The film retains bacteriostatic properties and is effective against gram‐positive bacteria but is less effective with gram‐negative bacteria and fungi (Crowder 1967). A report of toxicity in neonates led to restricted usage (Kimborough 1973), and today, hexachlorophene has mostly been replaced by triclosan.

Triclosan

Triclosan (2,4,4'–trichloro‐2'‐hydroxydiphenyl ether) has been incorporated in detergents (0.4% to 1%) and alcohols (0.2% to 0.5%) used for hygienic and surgical hand antisepsis or preoperative skin disinfection. It inhibits staphylococci, coliforms, enterobacteria and a wide range of gram‐negative intestinal and skin flora (Bartzokas 1983). Most strains of pseudomonas are resistant, and triclosan has only fair activity against mycobacterium tuberculosis and poor activity against fungi (Faoagali 1995).

Chloroxylenol

Chloroxylenol, also known as para‐chloro‐meta‐xylenol (PCMX), is a halogen‐substituted phenolic compound. It is not as quick‐acting as chlorhexidine or iodophors, and its residual activity is less pronounced than that observed with chlorhexidine gluconate (McDonnell 1999). In 1994, the FDA TFM tentatively classified chloroxylenol as having insufficient data to classify as safe and effective (WHO 2009).

Objectives

To assess the effects of surgical hand antisepsis on preventing surgical site infections (SSIs) in patients treated in any setting. The secondary objective is to determine the effects of surgical hand antisepsis on the number of bacteria colony‐forming units (CFUs) present on the hands of the surgical team.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All published and unpublished randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of surgical hand antiseptic techniques were included. Controlled clinical trials were to be considered in the absence of RCTs. Two possible units of randomisation were considered: the scrub team or individual members of the scrub team.

Types of participants

All members of the scrub team or personnel working within the operating theatre or day case setting. The SSI outcome is measured in participants who have undergone surgery.

Types of interventions

This review included comparisons of the following with each other and/or placebo and/or no antisepsis:

Surgical hand antisepsis;

Aqueous scrub solutions.

Alcohol rubs.

Alcohol rubs containing additional active ingredients.

Surgical hand antisepsis of different durations.

Surgical hand antisepsis using different equipment (e.g. brush, sponge, nail pick).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Occurrence of postoperative SSI, as defined by the CDC (Mangram 1999) or the study authors. We did not differentiate between superficial and deep‐incisional infection.

Secondary outcomes

Number of bacterial CFUs found on the hands of the surgical team.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We describe the search methods of the original version and first update of this review in Appendix 1.

For this first update we searched:

The Cochrane Wounds Group Specialized Register (searched 10 June 2015); The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2015, Issue 6); Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to 9 June 2015); Ovid MEDLINE ‐ In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations (9 June 2015); Ovid EMBASE (1974 to 9 June 2015); EBSCO CINAHL (1982 to 10 June 2015).

The following search strategy was used in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL):

#1 MeSH descriptor Surgical Wound Infection explode all trees #2 MeSH descriptor Surgical Wound Dehiscence explode all trees #3 surg* NEAR/5 infect*:ti,ab,kw #4 surg* NEAR/5 wound*:ti,ab,kw #5 surg* NEAR/5 site*:ti,ab,kw #6 surg* NEAR/5 incision*:ti,ab,kw #7 surg* NEAR/5 dehiscen*:ti,ab,kw #8 ((post‐operative or postoperative) NEAR/5 (wound NEXT infection*)):ti,ab,kw #9 MeSH descriptor Preoperative Care explode all trees #10 MeSH descriptor Perioperative Care explode all trees #11 ((preoperative or pre‐operative) NEXT care):ti,ab,kw #12 (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11) #13 MeSH descriptor Skin explode all trees #14 MeSH descriptor Antisepsis explode all trees #15 (#13 AND #14) #16 antisepsis:ti,ab,kw #17 MeSH descriptor Anti‐Infective Agents, Local explode all trees #18 MeSH descriptor Soaps explode all trees #19 MeSH descriptor Povidone‐Iodine explode all trees #20 MeSH descriptor Iodophors explode all trees #21 MeSH descriptor Chlorhexidine explode all trees #22 MeSH descriptor Alcohols explode all trees #23 MeSH descriptor Detergents explode all trees #24 (iodophor* or povidone‐iodine or betadine or chlorhexidine or triclosan or hexachlorophene or benzalkonium or alcohol or alcohols or antiseptic* or soap* or detergent*):ti,ab,kw #25 MeSH descriptor Disinfection explode all trees #26 MeSH descriptor Disinfectants explode all trees #27 (#25 OR #26) #28 (#13 AND #27) #29 (skin NEAR/5 disinfect*):ti,ab,kw #30 (#15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24 OR #28 OR #29) #31 MeSH descriptor Handwashing explode all trees #32 MeSH descriptor Hand explode all trees #33 ("hand" or "hands" or handwash* or (hand NEXT wash*) or (surgical NEXT scrub*)):ti,ab,kw #34 (#31 OR #32 OR #33) #35 (#12 AND #30 AND #34)

The search strategies for Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE and EBSCO CINAHL are available in Appendix 2, Appendix 3 and Appendix 4, respectively. We combined the Ovid MEDLINE search with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomised trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐ and precision‐maximising version (2008 revision) (Lefebvre 2011). We combined the EMBASE search with the Ovid EMBASE filter terms developed by the UK Cochrane Centre (Lefebvre 2011). We combined the CINAHL search with the trial filters developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (SIGN 2011). There were no restrictions with respect to language, date of publication or study setting.

Searching other resources

We handsearched the bibliographies of all retrieved and relevant publications identified by these strategies for further studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For the original review, three authors independently assessed the titles and abstracts of potentially relevant studies identified through the search strategy, retrieving the full text of all studies that potentially met the criteria. If it was unclear from the title or abstract whether a study met the criteria or there was a disagreement over the eligibility, we retrieved the full text of the study. The three authors then decided independently whether or not to include the studies. There were no disagreements among authors regarding which studies to include.

For the update, two authors independently assessed all titles and abstracts using the same methods, seeking assistance from translators where necessary. Again, there were no disagreements among authors about which studies to include.

Data extraction and management

We piloted a standardised data extraction form, and two authors independently used the finalised version to extract the following data from studies:

Trial data extracted

Duration of surgical antisepsis

Antiseptic solution used

Equipment used (e.g. brush, sponge, nail pick)

Role of the person carrying out the hand antisepsis, for example, scrub nurse or surgeon

Scrub history of the person scrubbing, for example, initial or subsequent scrub

Surgical specialty, for example, orthopaedics, ophthalmics, urology, etc.

Type of surgical procedure: elective or emergency

Duration of surgical procedure

Surgical glove material

Size of groups

Method of SSI detection

Duration of follow‐up

Trial outcomes

Number of SSIs

Number of CFUs (bacteria) on hands of surgical team

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the included studies using the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011). This tool addresses six specific domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete data, selective outcome reporting and other issues (Appendix 5). In this review we recorded issues with unit of analysis, for example where a cluster trial had been undertaken but analysed at the individual level in the study report. We assessed blinding of outcome assessment and completeness of outcome data for each of the review outcomes separately. For this review, we anticipated that blinding of participants (surgical staff) may not be possible. For this reason the assessment of the risk of detection bias focused on whether trials reported blinded outcome assessment (because wound infection can be a subjective outcome, it can be at high risk of measurement bias when outcome assessment is not blinded).

We presented our assessment of risk of bias using two 'Risk of bias' summary figures; one which is a summary of bias for each item across all studies, and a second which shows a cross‐tabulation of each trial by all of the risk of bias items. We summarised a study's risk of selection bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias and other bias.

Data synthesis

Data were entered into Review Manager software (RevMan 2014). Continuous outcomes (i.e. CFUs) were reported as mean differences (MDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Dichotomous outcomes (i.e. SSIs) were presented as risks ratio (RR) with 95% CI. We reported findings narratively and considered pooling of data after exploring clinical and statistical heterogeneity. We examined clinical heterogeneity by looking at the type of intervention, the participant population and the type of surgery. For assessment of statistical and related heterogeneity we used I2 values (Higgins 2003). I2 examines the percentage of total variation across RCTs that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance (Higgins 2003). Very broadly, we considered that I2 values of 25%, or less, may mean a low level of heterogeneity Higgins 2003, and values of more than 75%, or more, indicate very high heterogeneity.

Handling of data where the appropriateness of the analysis reported in the paper was unclear.

Where the trial had a cross‐over design or was cluster‐randomised but the analysis did not appear to take this into account, we reported the available raw data (e.g. mean values) as well as the effect estimate calculated in the paper and discussed the likely effect of an incorrect analysis on the effect estimate.

'Summary of findings' tables

In the update, in line with current Cochrane methods, we planned to present the main results of the review in ’Summary of findings’ tables where we had pooled data. These tables present key information concerning the quality of the evidence, the magnitude of the effects of the interventions examined and the sum of available data for the main outcomes (Schünemann 2011a). The 'Summary of findings' tables also include an overall grading of the evidence related to each of the main outcomes using the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach. The GRADE approach defines the quality of a body of evidence as the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the true quantity of specific interest. The quality of a body of evidence involves consideration of within‐trial risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias (Schünemann 2011b). We planned to present the following outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' tables for each comparison.

SSI events

Number of CFUs

Where we did not pool data, we decided to conduct the GRADE assessment for each comparison and present this narratively within the Results section without the presentation of separate 'Summary of findings' tables.

Results

Description of studies

Also see Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

The search for this update took place in June 2015 and yielded 274 abstracts. We obtained 18 of these as full‐text records for further assessment, subsequently excluding 14 (see Excluded studies) and including four (Al‐Naami 2009; Nthumba 2010; Tanner 2009; Vergara‐Fernandez 2010). The addition of these four new studies to the 10 studies in the previous version of the review brought the total number of studies included in this update to 14.

Over the life of the review, we have made attempts to contact seven authors to obtain further information (Gupta 2007, Hajipour 2006; Herruzo 2000; Kappstein 1993; Pereira 1997; Pietsch 2001; Sensoz 2003). Five authors responded (Hajipour 2006; Herruzo 2000; Kappstein 1993; Pereira 1997; Sensoz 2003). We included Hajipour 2006, Herruzo 2000, Kappstein 1993, Pereira 1997 and Pietsch 2001 in the review. We also included Gupta 2007 , although we have not carried out any independent analyses on their findings. The update identified one study (from a bibliographic search) that is awaiting assessment pending further information (Chen 2012).

Included studies

We present an overview of included studies and comparisons in Table 1.

1. Overview of included studies.

| Trial arms | |||||||||

| Study | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Country | Trial involved Surgery | SSI | CFU |

|

Al‐Naami 2009 n = 600 patients (data on 500) |

Aqueous scrub | Alcohol rub | NA | NA | NA | Saudi Arabia | ✓ Clean and clean‐contaminated operations. Mainly abdominal. |

✓ CDC guidelines |

✕ |

|

Furukawa 2005 n = 22 operating nurses |

Aqueous scrub | Aqueous scrub | NA | NA | NA | Japan | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ Iimmediately after antisepsis; glove juice method |

|

Gupta 2007 n = 22 operating staff |

Aqueous scrub | Alcohol rub + active ingredient | NA | NA | NA | USA | ✓ Ophthalmic, podiatric and general surgery |

✕ | ✓ Before antisepsis and immediately after antisepsis on day 1, after 6 hours on days 2 and 5; glove juice method |

|

Hajipour 2006 n = 4 surgeons (randomised and tested 53 times) |

Aqueous scrub | Alcohol rub + active ingredient | alcohol rub + active ingredient | NA | NA | UK | ✕ Trauma |

✕ | ✓ At the end of the surgical procedure; glove juice method |

|

Herruzo 2000 n = 154 surgical staff |

Aqueous scrub | Aqueous scrub | NA | NA | NA | Spain | ✓ Plastic surgery and traumatology |

✕ | ✓ Before antisepsis, immediately after antisepsis and at the end of the surgical procedure; finger press testing with agar plates |

|

Kappstein 1993* n = 24 surgeons |

Aqueous scrub 1 (duration1) | Aqueous scrub 2 (duration 2) | NA | NA | NA | Germany | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ Before antisepsis and immediately after antisepsis; glove juice method |

|

Nthumba 2010 n = 66 surgical staff and 3317 patients |

Alcohol rub + active ingredient | Standard hand hygiene | NA | NA | NA | Kenya | ✓ Clean and clean‐contaminated operations. Mixed surgery types. |

✓ Modified CDC guidelines |

✕ |

|

Parienti 2002 n = 4387 patients |

Aqueous scrub | Alcohol rub + active ingredient | NA | NA | NA | France | ✓ Mix of procedures |

✓ CDC guidelines |

✕ |

|

Pereira 1990a n = 34 nurses |

Aqueous scrub 1 Duration 1 |

Aqueous scrub 2 Duration 1 |

Aqueous scrub 1 Duration 2 |

Aqueous scrub 2 Duration 2 |

NA | Australia | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ Immediately after antisepsis, 2 hours after initial antisepsis, 2 hours after subsequent antisepsis; glove juice method |

|

Pereira 1997 n = 34 operating room nurses |

Aqueous scrub 1 (duration1) | Aqueous scrub 2 (duration 2) | Aqueous scrub 3 (duration 2) | Alcohol rub + active ingredient 1 | Alcohol rub + active ingredient 2 | Australia | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ Immediately after antisepsis, 2 hours after initial antisepsis, 2 hours after subsequent antisepsis; glove juice method |

|

Pietsch 2001 n= 75 surgeons |

Aqueous scrub | Alcohol rub + active ingredient | NA | NA | NA | Germany | ✓ No detail |

✕ | ✓ Immediately after antisepsis and after surgical procedure completed; glove juice method |

|

Tanner 2009 n= 164 staff |

Aqueous scrub | Aqueous scrub +nail pick | Aqueous scrub +nail brush | NA | NA | UK | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ 1 hour after antisepsis; modified glove juice method |

|

Vergara‐Fernandez 2010 n = 100 patients |

Aqueous scrub | Alcohol rub + active ingredient | NA | NA | NA | Mexico | ✓ Clean and clean‐contaminated operations. Mixed surgery types. |

✓ CDC guidelines |

✕ Only 20% of the 400 enrolled staff were assessed for bacteria on hands; data not included |

|

Wheelock 1997 n = 25 operating theatre nurses and surgical technologists |

Aqueous scrub 1 (duration 1) | Aqueous scrub 2 (duration 2) | NA | NA | NA | USA | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ 1 hour after antisepsis; glove juice method |

NA: not applicable

We identified and included 14 eligible trials in this review. Four trials reported the primary outcome, namely SSI (Al‐Naami 2009; Nthumba 2010; Parienti 2002; Vergara‐Fernandez 2010). The remaining 10 trials reported the number of CFUs (on the hands of the surgical team), which is a surrogate outcome that is thought to give an impression of the likelihood of infection. All 14 trials took place in operating departments, with 8 studies involving surgery and 6 testing interventions in surgical staff but without surgery taking place. Of the included studies, four compared different durations of scrubs or rubs (Kappstein 1993; Pereira 1990; Pereira 1997; Wheelock 1997).

Some of the included studies had complicated designs: Parienti 2002 was an equivalence, cluster, cross‐over trial where the unit of randomisation was the surgical service. Each surgical service carried out one intervention for one month and then switched to the alternative intervention the following month. Nthumba 2010 also used a cluster, cross‐over design, whereby operating theatres were allocated to an intervention with cross‐over every two months. We also considered Hajipour 2006 to be a cluster trial, as it randomised four surgeons to different antisepsis methods which they used prior to surgery on multiple participants. Seven other studies (Gupta 2007, Herruzo 2000, Kappstein 1993, Pereira 1990; Pereira 1997; Pietsch 2001; Wheelock 1997) were also cross‐over trials.

Definition of scrub procedure

Six trials gave detailed protocols for their antisepsis techniques (Furukawa 2005; Parienti 2002; Pereira 1990; Pereira 1997; Tanner 2009; Wheelock 1997). Authors from eight trials reported using a brush or sponge (Gupta 2007; Furukawa 2005; Herruzo 2000; Parienti 2002; Pereira 1990; Pereira 1997; Vergara‐Fernandez 2010), while Tanner 2009 compared a nail brush and nail pick. Parienti 2002 and Wheelock 1997 stated that antisepsis protocols met with national guidelines. Seven of the trials employed a 'supervisor' to observe compliance with the antisepsis protocol (Furukawa 2005; Nthumba 2010; Parienti 2002; Pereira 1990; Pereira 1997; Tanner 2009; Wheelock 1997). Three trials presented minimal details of the antisepsis protocol (Gupta 2007; Hajipour 2006; Nthumba 2010), and the remaining five trials did not comment on antisepsis techniques (Al‐Naami 2009; Herruzo 2000; Kappstein 1993; Pietsch 2001; Vergara‐Fernandez 2010).

Excluded studies

Risk of bias in included studies

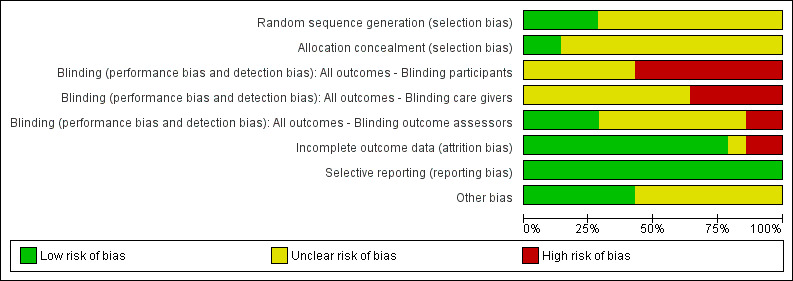

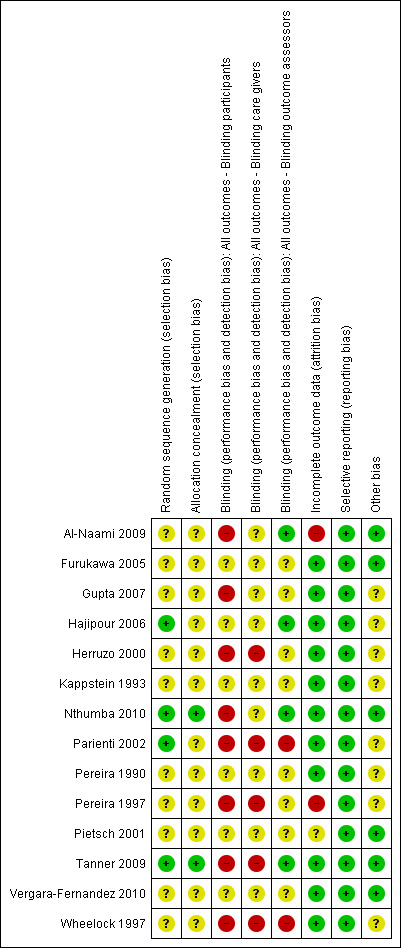

We summarise our 'Risk of bias' assessment in Figure 1, Figure 2 and in the 'Risk of bias' assessment tables. Overall, most studies were at unclear risk or high risk of bias for one of the following: selection bias, detection bias and attrition bias. Only two studies were at low risk of bias for all these (Nthumba 2010; Tanner 2009).

1.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

We considered four studies to be at low risk of detection bias, as they blinded outcome assessors (Al‐Naami 2009; Nthumba 2010; Hajipour 2006; Tanner 2009). We considered two studies to be at high risk of detection bias (Parienti 2002; Wheelock 1997).

We also judged two studies to be at high risk of attrition bias. Pereira 1997 reported that 9/32 randomised members of staff failed to complete with no reasons given for withdrawal. Al‐Naami 2009 excluded 100 of 600 patients from the analysis for reasons such as their condition was revised on subsequent histopathological examination, they had incomplete forms, or they "failed follow‐up".

We judged several studies to be at unclear risk of other bias due to uncertainty as to whether a cluster‐randomised or cross‐over design had been taken into account in the analysis. Parienti 2002 and Hajipour 2006 were at unclear risk of other bias as a cluster design was detected but it did not seem that clustering had been taken into account in the analyses. Herruzo 2000, Kappstein 1993, Pereira 1990, Pereira 1997; Wheelock 1997 were at unclear risk because it appeared that the crossover designs had not been taken into consideration in the analyses.

Effects of interventions

We included 14 trials in this review. In total, the trials evaluated nine basic comparisons related to the type (i.e. scrub or rub, active ingredients), duration and tools used for surgical hand antisepsis.

Comparison 1: basic hand hygiene versus alcohol rub containing additional active ingredients (Nthumba 2010).

Comparison 2: different aqueous scrub solutions: chlorhexidine gluconate versus povidone iodine (Furukawa 2005; Herruzo 2000; Pereira 1990; Pereira 1997).

Comparison 3: comparison of different alcohol rubs containing additional active ingredients (Gupta 2007; Pereira 1997).

Comparison 4: aqueous scrubs versus alcohol‐only rubs (Al‐Naami 2009).

Comparison 5: aqueous scrubs versus alcohol rubs containing additional active ingredients (Gupta 2007; Hajipour 2006; Herruzo 2000; Parienti 2002; Pietsch 2001; Vergara‐Fernandez 2010).

Comparison 6: duration of surgical antisepsis (Kappstein 1993; Pereira 1990; Pereira 1997; Wheelock 1997).

Comparison 7: surgical hand antisepsis using a nail pick versus surgical hand antisepsis not using a nail pick (Tanner 2009).

Comparison 8: surgical hand antisepsis using a brush versus surgical hand antisepsis not using a brush (Tanner 2009).

Comparison 9: surgical hand antisepsis using a nail pick versus surgical hand antisepsis using a brush (Tanner 2009).

Comparison 1: basic hand hygiene versus alcohol rub containing additional active ingredients (1 study)

Basic hand hygiene (soap and water) compared with 75% isopropyl alcohol plus 0.125% hydrogen peroxide

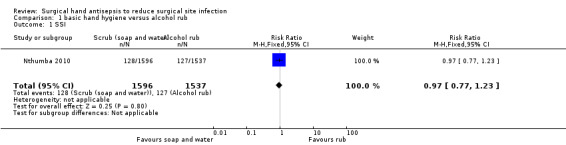

Nthumba 2010 compared soap and water with an alcohol rub which contained hydrogen peroxide as an additional active ingredient. Surgeons in both groups scrubbed with soap and water for 4 to 5 minutes before the first procedure of the day and subsequently if there was visible soiling. For subsequent procedures, surgeons were randomised in clusters based on operating theatre to soap and water or 7 to 10 ml of a locally produced hand rub based on isopropyl alcohol with hydrogen peroxide, which they applied for 3 minutes and kept wet. The trial used a total of 10 clusters, each defined by six operating theatres, across five two‐month intervals, with cross‐over after each two‐month period. The trial included 3317 patients undergoing clean and clean‐contaminated surgery and assessed SSI at 30 days using modified CDC definitions. There appeared to be a low risk of bias for all domains except the blinding of participants and personnel, which would have been difficult to achieve. Trialists accounted for both the clustering and cross‐over in the power calculation and in the analyses.

Outcomes

Surgical site infection (SSI)

Nthumba 2010 collected SSI data for 30 days after discharge. There was no clear difference in the number of SSIs between groups. In total, 8% (128/1596) of participants developed SSI in the soap and water scrub group compared with 8.3% (127/1537) in the alcohol rub group (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.23). This was based on a complete case analysis; data were unavailable for 5.5% (184/3317) of participants and were not imputed. Losses to follow‐up were comparable between the two arms, at 5.1% (86/1682) for soap and water scrub versus 6.0% (98/1635) for alcohol rub (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 basic hand hygiene versus alcohol rub, Outcome 1 SSI.

Moderate quality evidence, downgraded once for imprecision. A GRADE assessment of moderate quality evidence means that further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

Number of colony forming units (CFUs)

Not reported

Comparison 1 Summary: Basic hand hygiene compared to alcohol rubs containing additional active ingredients

It is not clear whether hand antisepsis with soap and water is more or less effective in preventing subsequent SSI than antisepsis with an alcohol rub containing hydrogen peroxide (moderate quality evidence).

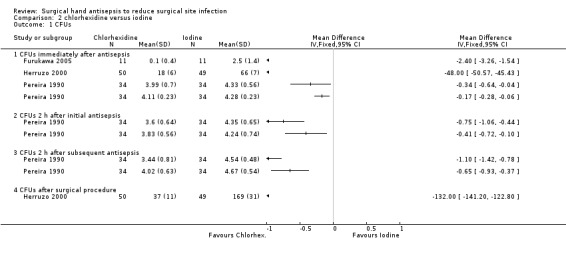

Comparison 2: different aqueous scrub solutions: chlorhexidine gluconate versus povidone iodine (4 trials)

Four studies compared chlorhexidine gluconate versus povidone iodine but used different regimens.

Pereira 1990 randomly assigned 34 participants (operating room nurses) to one of four groups. The four interventions (which were used for 1 week) were 4% chlorhexidine gluconate (Hibiclens) or 7.5% povidone iodine (Betadine), using a 5 minute initial and 3 minute subsequent scrub; and 4% chlorhexidine gluconate (Hibiclens) or 7.5% povidone iodine (Betadine) using a 3 minute initial and 30 second subsequent scrub. Control of the order of interventions was through a Latin square design. Investigators took hand bacterial samples immediately after the initial scrub, 2 hours after the initial scrub and 2 hours after the subsequent scrub. Although the study had a cross‐over design, it did not appear that this was taken into consideration in the analysis, thus 95% CIs may be overestimated.

Furukawa 2005 compared 4% chlorhexidine gluconate (Hibiscrub) with 7.5% povidone iodine (Isodine) using a 3 minute scrub. Twenty‐two operating room nurses were randomised to one of the two intervention groups. Each nurse took part only once. The nurses did not take part in any actual surgery.

Herruzo 2000 randomised 154 members of surgical teams and compared three intervention groups: relevant to this comparison was a 3 minute scrub of either aqueous chlorhexidine gluconate 4% or aqueous povidone iodine 7.5%. The study had a cross‐over design, which appears to have been accounted for. The study also reports repeated measures which does not appear to have been accounted for in the analysis.

Pereira 1997 compared 4% chlorhexidine gluconate (Hibiclens) with 5% povidone iodine plus 1% triclosan (Microshield PVP) using a 3 minute initial and 2.5 minute subsequent scrub. Twenty‐three operating room nurses were randomised to carry out each of five interventions for one week each. The order of interventions was controlled through a Latin square design. Participants did not take part in any actual surgery. Investigators took hand bacterial samples immediately after the first antisepsis, 2 hours after the first antisepsis and 2 hours after the subsequent antisepsis. Although the study had a cross‐over design, it did not appear that trialists took this into consideration in the analysis, thus the 95% CI may be overestimated.

Outcomes

Surgical site infection

Not reported

Number of colony forming units (CFUs)

Chlorhexidine gluconate compared with povidone iodine

Pereira 1990 compared 4% chlorhexidine gluconate (Hibiclens) with 7.5% povidone iodine (Betadine) using a 5 minute initial and 3 minute subsequent scrub. There was some evidence that scrubbing with chlorhexidine might be more effective than with povidone iodine in reducing the number of CFUs on the hand immediately after scrubbing (MD − 0.34, 95% CI − 0.64 to − 0.04; ), 2 hours after the initial scrub (MD − 0.75, 95% CI − 1.06 to − 0.44) and 2 hours after the subsequent scrub (MD − 1.10, 95% CI −1.42 to − 0.78; Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 chlorhexidine versus iodine, Outcome 1 CFUs.

Because the analysis did not account for the effects of paired data resulting from the cross‐over design, the study may have overestimated the uncertainty of the effect estimate; the correct 95% CIs for the estimate may be narrower than those reported here. However, the study also used a repeated measures design which the analysis did not account for; this could lead to an underestimation of the uncertainty. The interaction of these two factors makes the true confidence intervals unclear, so we have downgraded the evidence twice due to imprecision.

Very low quality evidence due to imprecision and indirectness of outcome. Downgraded twice for imprecision due to two analytical issues which mean precision estimates may change upon correct analysis of data, and downgraded twice for indirectness as CFU is a surrogate outcome and because the intervention was used in the absence of surgery being conducted. A GRADE assessment of very low quality evidence means any estimate of effect is very uncertain. Pereira 1990 compared 4% chlorhexidine gluconate (Hibiclens) with 7.5% povidone iodine (Betadine) using a 3 minute initial and 30 second subsequent scrub. There was evidence that chlorhexidine may be more effective than povidone iodine in reducing the number of CFUs immediately post scrubbing (MD − 0.17, 95% CI − 0.28 to − 0.06), 2 hours after the initial scrub (MD − 0.41, 95% CI − 0.72 to − 0.10) and 2 hours after the subsequent scrub (MD − 0.65, 95% CI − 0.93 to − 0.37 Analysis 2.1).

Very low quality evidence due to imprecision and indirectness of outcome (as above).

In Furukawa 2005, there were fewer CFUs in the chlorhexidine gluconate group after scrubbing (MD − 2.40, 95% CI − 3.26 to − 1.54; Analysis 2.1).

Low quality evidence: downgraded twice for indirectness as CFU is a surrogate outcome and because the intervention was used in the absence of surgery being conducted.

In Herruzo 2000, there was evidence that a 3 minute aqueous scrub using chlorhexidine gluconate was more effective in reducing CFUs on hands than a 3 minute aqueous scrub using povidone iodine, both immediately after antisepsis (MD − 48.00, 95% CI − 50.57 to − 45.4) and at the end of a surgical procedure (MD − 132.0, 95% CI − 141.20 to − 122.80; Analysis 2.1). Because the analysis did not account for the repeated measures, the study may have underestimated uncertainty around the effect estimate: the true confidence intervals for the estimate may be wider than those reported here.

Low quality evidence; downgraded once as precision estimates may change upon correct analysis of data and downgraded once due to indirectness as CFU is a surrogate outcome.

We considered pooling the three studies (four comparisons) (Furukawa 2005; Herruzo 2000; Pereira 1990); however, in light of the high degree of statistical heterogeneity for each possible comparison (ranging from 100% to 56%) and the differences in interventions noted, we did not undertake this.

Chlorhexidine gluconate compared with povidone iodine plus triclosan

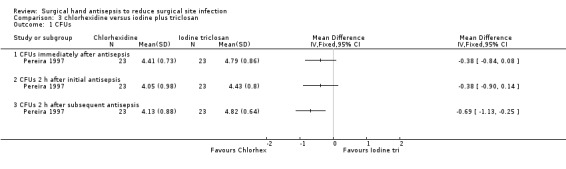

Pereira 1997 reported no evidence of a difference in CFUs immediately after the first antisepsis (MD − 0.38, 95% CI − 0.84 to 0.08) (Analysis 3.1) and 2 hours after the first antisepsis (MD − 0.38, 95% CI − 0.90 to 0.14) (Analysis 3.2). The trial found a difference in favour of chlorhexidine 2 hours after the subsequent antisepsis (MD − 0.69, 95% CI − 1.13 to − 0.25) (Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 chlorhexidine versus iodine plus triclosan, Outcome 1 CFUs.

Because the analysis did not account for the effects of paired data resulting from the cross‐over design or for the effect of using repeated measures, the true confidence intervals for the estimate are uncertain.

Very low quality evidence downgraded once for risk of attrition bias; twice for imprecision and twice for indirectness ‐ once for indirectness of outcome and once because the intervention was used in the absence of surgery being conducted.

Comparison 2 Summary : Comparison of different aqueous scrub solutions ‐ chlorhexidine gluconate compared with povidone iodine

Data from four trials (five comparisons) of chlorhexidine‐containing aqueous scrub solutions with povidone iodine containing solutions (all having initial longer duration of use followed by shorter subsequent use) suggest that chlorhexidine containing agents may reduce the numbers of CFU on the hands to a greater extent than povidone iodine containing solutions. However, overall this is low or very low quality evidence, and the number of CFUs is a surrogate outcome for SSI. Some of the studies included appeared to have been incorrectly analysed and one was at high risk of attrition bias. No trials reported SSI events so there is no evidence to link the number of CFUs to clinical outcomes.

Comparison 3: comparison of different alcohol rubs containing additional active ingredients (2 trials)

Two trials compared alcohol rubs containing additional active ingredients (Gupta 2007; Pereira 1997).

Gupta 2007 compared three 2 ml aliquots of 1% chlorhexidine gluconate in 61% ethyl alcohol (Avagard) against a 3 minute application of zinc pyrithione in 70% ethyl alcohol (Triseptin). The 61% alcohol solution is a waterless product, and the 70% alcohol solution is a water aided product which requires rinsing with water. Eighteen operating room staff used each product for five consecutive days. Testing was carried out immediately before and after antisepsis on day one, and at the end of days two and five.

Pereira 1997 compared 0.5% chlorhexidine gluconate in isopropanol compared with 0.5% chlorhexidine gluconate in ethanol. The alcohol rubs were used immediately after an aqueous scrub (with 4% chlorhexidine gluconate) and also as the subsequent antiseptic agent. The active ingredient in both alcohol rubs was the same (i.e. 0.5% chlorhexidine gluconate), and both preparations had 70% strength alcohol, the only difference being the alcohol (isopropanol versus ethanol). Scrubs lasted for 2 minutes, and the initial and subsequent applications of alcohol rubs lasted for 30 seconds.

Outcomes

Surgical site infection

Not reported

Number of colony forming units (CFUs)

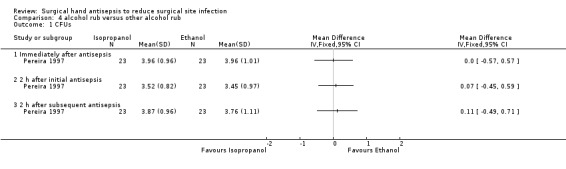

Pereira 1997 did not find a difference in the number of CFUs between the isopropanol‐ and ethanol‐based rubs immediately after the first antisepsis (MD 0.00, 95% CI − 0.57 to 0.57), 2 hours after the first antisepsis (MD 0.07, 95% CI ‐0.45 to 0.59) or 2 hours after the subsequent antisepsis (MD 0.11, 95% CI − 0.49 to 0.71); see Analysis 4.1. Differences between groups were consistently small and imprecise. As previously noted, the true confidence intervals for the effect estimates is uncertain because of the issues with the analysis.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 alcohol rub versus other alcohol rub, Outcome 1 CFUs.

Very low quality evidence due to risk of bias of attrition bias; imprecision and indirectness of outcome.

Gupta 2007 did not present sufficient raw data in the trial report to allow us to conduct independent statistical analyses, so we have contacted the author for further information. In the interim, we present Gupta 2007's own analysis. Although the trial used a cross‐over design, we could not determine if this was accounted for in the analysis. When the CFUs were compared over the duration of the study, Gupta 2007 found no statistically significant difference between the solutions (P = 0.21). It must be noted that this analysis has not been independently verified.

Very low quality evidence downgraded due to indirectness of aggregate data that has not be checked or verified by review authors; also downgraded due to indirectness of outcome and imprecision as no CIs available.

Comparison 3 Summary: Comparison of different alcohol rubs containing additional active ingredients.

The comparative effects of different alcohol rubs (each containing additional active ingredients) on number of CFUs are unclear, as the existing evidence is very sparse and of very low quality.

Comparison 4: aqueous scrubs versus alcohol‐only rubs (1 trial)

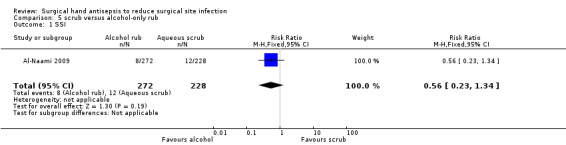

Al‐Naami 2009 compared a traditional 3 to 5 minute scrub with either chlorhexidine or povidone iodine versus 10 ml of a 62% ethyl alcohol handrub, which was allowed to dry. Surgeons in both groups scrubbed with the aqueous solution for the first procedure of the day. The study was described as an equivalence trial. Six hundred patients undergoing clean and clean‐contaminated surgery were randomised to the two arms; investigators reported data for 500 patients. Reasons for participants being excluded from the analysis included a revised assessment of their condition on subsequent histopathological examination, incomplete forms or failed follow‐up. More patients in the traditional scrub arm (24%, 72/300) were excluded from the analysis than in the alcohol rub arm (9%, 28/300).

Outcomes

Surgical site infection (SSI)

Al‐Naami 2009 collected SSI data over 30 days from surgery. There was no clear evidence of a difference in number of SSIs, with 2.9% (8/272) of participants in the alcohol rub arm having an SSI compared with 5.2% (12/228) in the aqueous scrub group (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.23 to 1.34) (Analysis 5.1). This trial was considered to be at high risk of attrition bias.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 scrub versus alcohol‐only rub, Outcome 1 SSI.

Very low quality evidence; downgraded once due to risk of attrition bias and twice for imprecision.

Number of colony forming units

Not reported

Comparison 4 Summary: Aqueous scrubs compared with alcohol only rubs

It is unclear whether there is a difference in SSIs between aqueous handscrubs and alcohol‐only rubs (very low quality evidence from one study).

Comparison 5: aqueous scrubs versus alcohol rubs containing additional active ingredients (6 trials)

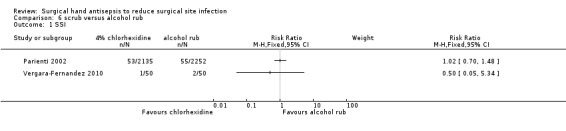

Six studies compared traditional scrubs with alcohol rubs containing additional active ingredients (Gupta 2007; Hajipour 2006; Herruzo 2000; Parienti 2002; Pietsch 2001; Vergara‐Fernandez 2010). The six trials used different antiseptic solutions, therefore it was not appropriate to perform a meta‐analysis. Each trial is considered separately.

Parienti 2002 compared a 5 minute scrub using either 4% povidone iodine (Betadine) or 4% chlorhexidine gluconate (Hibiscrub) versus a 5 minute handrub using 75% propanol‐1, propanol‐2 with mecetronium ethylsulphate (Sterillium). Participants in the aqueous scrub group could choose between chlorhexidine gluconate or povidone iodine solutions. Participants in the handrubbing group carried out a single handwash for 1 minute with non‐antiseptic soap at the start of each day. The entire scrub team in each of six hospitals took part. The trial included 4387 consecutive patients undergoing clean and clean‐contaminated surgery and assessed SSI at 30 d using the CDC definition. The study was an equivalence, cluster cross‐over trial but did not appear to have accounted for the clustering in the analysis.

Vergara‐Fernandez 2010 compared an aqueous scrub with 4% chlorhexidine gluconate (which involved the use of a brush and a sponge) versus a handrub using 61% ethyl alcohol plus 1% chlorhexidine gluconate. Mean duration of the aqueous scrub was 3.9 minutes (SD 1.07), and mean duration of the alcohol rub was 2.0 minutes (SD 0.47). This trial took place in a single institution and involved 400 staff operating on 100 patients undergoing clean and clean‐contaminated surgery, who were randomised to the two hand antisepsis groups. Investigators assessed SSI at one month using the CDC definition. Twenty per cent of the included staff had hand samples sent for microbiological examination, and samples were assessed as positive or negative for hand cultures.

Herruzo 2000 compared three intervention groups: chlorhexidine gluconate scrub versus povidone iodine scrub versus an alcohol rub with N‐duopropenide. Each scrub or rub lasted 3 minutes. We successfully contacted Herruzo 2000 for additional information regarding sample size. 154 members of the surgical team were randomised for 55 operations. Investigators measured CFUs before antisepsis, immediately after antisepsis and at the end of the surgical procedure.

Pietsch 2001 compared scrubbing using 4% chlorhexidine gluconate (Hibiscrub) with hand rubbing using an alcoholic solution of 45% propanol‐2, 30% propanol‐1 plus 0.2% ethylhexadecyldimethyl ammonium ethylsulphate (Sterillium). Seventy‐five surgeons from one hospital participated in this randomised cross‐over trial, using one product for four weeks then changing to the alternative product following a rest week. CFUs were measured before antisepsis, immediately after antisepsis and after the surgical procedure.

Hajipour 2006 compared a 3 minute 4% chlorhexidine gluconate scrub versus a 3 minute chlorhexidine in alcohol rub (Hydrex). We contacted the trial authors, who provided additional study details. Following an aqueous chlorhexidine scrub at the start of each day, four surgeons were randomised to one or other intervention and were evaluated repeatedly in that condition. Testing was carried out using the finger press method at the end of each surgical procedure.

Gupta 2007 compared 7.5% povidone iodine aqueous scrub against two alcohol rubs: three 2 ml aliquots of 1% chlorhexidine gluconate in 61% ethyl alcohol (Avagard) and a 3 minute application of zinc pyrithione in 70% ethyl alcohol (Triseptin). The paper does not provide further details regarding the application of the products. Eighteen operating room staff used each of the three products for five consecutive days. Testing was carried out immediately before and after antisepsis on day one, and at the end of days two and five.

Outcomes

Surgical site infection (SSI)

Aqueous povidone iodine or chlorhexidine gluconate versus 75% propanol‐1, propanol‐2 plus mecetronium ethylsulphate

Parienti 2002 collected data for 30 days following surgery. There was no clear evidence of a difference in the rates of SSI between aqueous scrub and alcohol rub: 2.5% (53/2135) of participants developed an SSI in the scrub group compared with 2.4% (55/2252) in the handrub group (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.48) (Analysis 6.1).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 scrub versus alcohol rub, Outcome 1 SSI.

Low quality evidence downgraded once due to risk of detection bias and once due to imprecision.

Aqueous chlorhexidine gluconate compared with 61% ethyl alcohol plus 1% chlorhexidine gluconate

Vergara‐Fernandez 2010 found no clear evidence of a difference in SSI rates between groups. In total 2% of participants (1/50) had a SSI in the aqueous scrub group compared with 4% (2/50) in the alcohol handrub group (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.05 to 5.34). The study was small and the resulting 95% CI intervals wide, ranging from a 95% reduction in risk of SSI to a 400% increased risk of SSI (Analysis 6.1).

Low quality evidence downgraded twice due to imprecision.

Number of colony‐forming units

Aqueous chlorhexidine gluconate versus N‐duopropenide

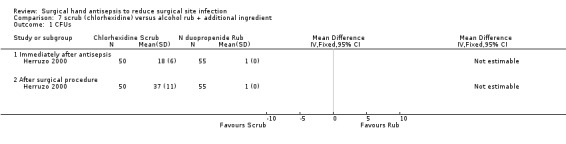

Herruzo 2000 reported CFU data (log10) after antisepsis and after surgery (Analysis 7.1). We were unable to produce an estimate of treatment effect for the review. Using bivariate analysis, Herruzo 2000 reports that N‐duopropenide is more effective than chlorhexidine in reducing the number of CFUs on participants' hands immediately after antisepsis (P value < 0.01) and at the end of a surgical procedure (P value < 0.01); the paper did not provide any further information on estimates.

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 scrub (chlorhexidine) versus alcohol rub + additional ingredient, Outcome 1 CFUs.

Very low quality evidence downgraded twice as precision estimates are not available and once due to indirectness of outcome.

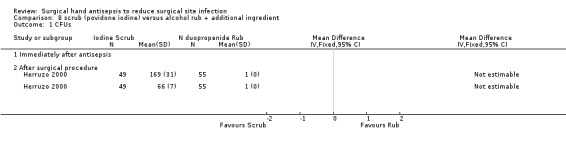

Aqueous povidone iodine versus N‐duopropenide

Herruzo 2000 reported CFU data (log10) after antisepsis and after surgery (Analysis 8.1). We were unable to produce an estimate of treatment effect for the review. Using bivariate analysis, Herruzo 2000 reports that N‐duopropenide was statistically significantly more effective than povidone iodine in reducing the number of CFUs on participants hands immediately after antisepsis (P value <0.01) and at the end of a surgical procedure (P value <0.01).

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 scrub (povidone iodine) versus alcohol rub + additional ingredient, Outcome 1 CFUs.

Very low quality evidence downgraded twice as precision estimates are not available and once due to indirectness of outcome.

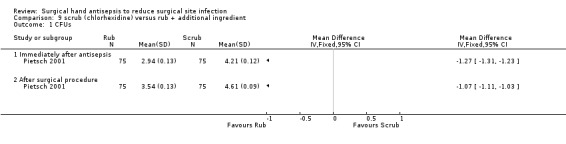

Aqueous chlorhexidine gluconate versus 45% propanol‐2, 30% propanol‐1 plus 0.2% ethylhexadecyldimethyl ammonium ethylsulphate (Sterillium)

Pietsch 2001 reported that rubbing using 45% propanol‐2, 30% propanol‐1 plus 0.2% ethylhexadecyldimethyl ammonium ethylsulphate (Sterillium) was more effective in reducing CFUs on participants' hands than scrubbing using 4% chlorhexidine gluconate, both immediately after antisepsis (MD − 1.27, 95% CI − 1.23 to − 1.31) and at the end of the surgical procedure (MD − 1.07, 95% CI − 1.03 to − 1.11); Analysis 9.1.

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 scrub (chlorhexidine) versus rub + additional ingredient, Outcome 1 CFUs.

Moderate quality evidence downgraded once due to indirectness of outcome.

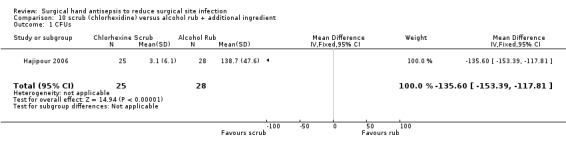

Aqueous 4% chlorhexidine gluconate versus 0.5% chlorhexidine gluconate in 70% alcohol

Hajipour 2006 reported finding fewer CFUs following an aqueous scrub than after an alcohol rub (MD − 135.60, 95% CI − 153.39 to − 117.81; Analysis 10.1).

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 scrub (chlorhexidine) versus alcohol rub + additional ingredient, Outcome 1 CFUs.

This study had a cluster design, in which each surgeon constituted a cluster, giving two clusters in each trial arm. However, the analysis did not take this into consideration, so the reliability of the effect estimate reported by the authors is uncertain and could be wider than reported.

Very low quality evidence downgraded twice due to potential imprecision as re‐analysis of data could increase the confidences intervals and change study conclusions and once due to indirectness of outcome.

Aqueous povidone iodine versus 61% ethyl alcohol and 70% ethyl alcohol

Gupta 2007 did not present sufficient raw data for us to be able to conduct independent statistical analysis, so we contacted the author to request additional data. In the interim we present Gupta 2007's own analysis. When CFUs were compared collectively from all the sample times, Gupta 2007 reports 'no statistically significant difference' between the solutions (P = 0.21). It must be noted that this analysis has not been independently verified and it is unclear if investigators adjusted this analysis to account for the cross‐over design.

Very low quality evidence downgraded twice for imprecision as CIs not available and twice for indirectness as we were unable to assess the actual results and the analysis undertaken and because the outcome is a surrogate outcome.

Comparison 5 summary: Aqueous scrubs compared with alcohol rubs containing additional active ingredients

It is unclear if there is a difference in numbers of SSIs between aqueous scrubs and alcohol rubs. The CFU outcome data were varied with two studies finding in favour of the alcohol rubs (moderate and very low quality evidence), one favouring the scrub arm (very low quality evidence) and one study reporting a 'non‐statistically significant difference' with no other data (very low quality evidence).

Comparison 6: duration of surgical antisepsis (4 trials)

Four trials compared surgical antisepsis of different durations but used different antiseptic agents, which prevented us from pooling results (Kappstein 1993; Pereira 1990; Pereira 1997; Wheelock 1997).

Wheelock 1997 randomised 25 operating room nurses and surgical technologists to either a 2 minute or a 3 minute scrub. After carrying out the trial scrub, and following a one‐week washout period in which they continued to undertake scrubbing as part of their usual work, the participants switched to the other intervention. Though the intention of the trial authors was for participants to use aqueous 4% chlorhexidine gluconate (Hibiclens), participants with a history of skin irritation (15/25 participants) used either 2% chlorhexidine gluconate or parachlorometaxylenol (PCMX). CFUs were measured 1 hour after the surgical scrub.

Kappstein 1993 compared a five minute rub with a three minute rub using alcoholic disinfectant. The disinfectant is not identified. Both rubs followed 1 minute handwashes using soap and water. Twenty‐four surgeons carried out each of three intervention groups once in a random order. Samples were taken before and immediately after antisepsis.

Pereira 1990 compared a 5 minute initial and 3 minute subsequent scrub with a 3 minute initial and 30 second subsequent scrub using chlorhexidine gluconate. Thirty‐four participants were randomly assigned to one of four groups, and each group was assigned to one of four interventions, each lasting one week.

Pereira 1990 also compared a 5 minute initial and 3 minute subsequent scrub with a 3 minute initial and 30 second subsequent scrub using povidone iodine.

Pereira 1997 compared a 5 minute initial and a 3.5 minute subsequent scrub with a 3 minute initial and a 2.5 minute subsequent scrub using 4% chlorhexidine gluconate. Twenty‐three operating room nurses were randomised to carry out each of five interventions for one week each.

Outcomes

Surgical site infection (SSI)

Not reported

Number of colony forming units (CFUs)

Three minute scrub versus two minute scrub

Wheelock 1997 presented paired data, which the review authors re‐analysed but did not present. There were fewer CFUs on hands immediately after a 3 minute scrub compared with a 2 minute scrub (MD − 0.29, 95% CI − 0.06 to − 0.52).

Very low quality evidence downgraded once due to risk of detection bias and twice due to indirectness, once due to indirectness of outcome and once because the intervention was used in the absence of surgery being conducted.

Five minute rub versus three minute rub (Analysis 11.1)

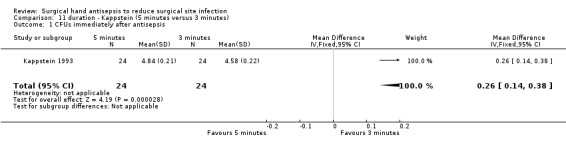

Kappstein 1993 favoured the 3 minute scrub over the 5 minute scrub when assessed immediately after antisepsis (MD 0.26, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.38; Analysis 11.1). Because the use of a cross‐over design was not accounted for in the analysis the true confidence intervals may be narrower than those reported here.

11.1. Analysis.

Comparison 11 duration ‐ Kappstein (5 minutes versus 3 minutes), Outcome 1 CFUs immediately after antisepsis.

Low quality evidence: downgraded once due to imprecision and once due to indirectness.

Five minute initial and three minute subsequent scrub versus three minute initial and 30 second subsequent scrub using chlorhexidine (Analysis 12.1)

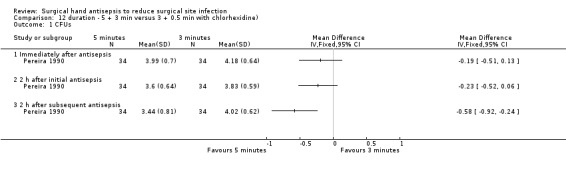

Pereira 1990 reported no clear difference between groups in the number of CFUs immediately after the initial scrub (MD − 0.19, 95% CI − 0.51 to 0.13) or 2 hours after the initial scrub (MD − 0.23, 95% CI − 0.52 to 0.06). There was evidence of a difference in CFUs favouring the 5 minute arm 2 hours after the subsequent scrub (MD − 0.58, 95% CI − 0.92 to − 0.24); see Analysis 12.1.

12.1. Analysis.

Comparison 12 duration ‐ 5 + 3 min versus 3 + 0.5 min with chlorhexidine), Outcome 1 CFUs.

Very low quality evidence down graded twice due to imprecision and once due to indirectness of outcome.

Five minute initial and three minute subsequent scrub compared with a three minute initial and 30 second subsequent scrub using povidone iodine (Analysis 13.1)

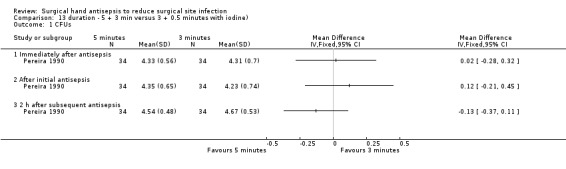

In Pereira 1990, there was no clear difference in the number of CFUs at any time point, whether immediately after the initial scrub (MD 0.02, 95% CI − 0.28 to 0.32), 2 hours after the initial scrub (MD 0.12, 95% CI − 0.21 to 0.45) or 2 hours after the subsequent scrub (MD − 0.13, 95% CI − 0.37 to 0.11); see Analysis 13.1.

13.1. Analysis.

Comparison 13 duration ‐ 5 + 3 min versus 3 + 0.5 minutes with iodine), Outcome 1 CFUs.

Very low quality evidence downgraded due to imprecision and indirectness of outcome.

Five minute initial and three and 30 second subsequent scrub compared with a three minute initial and two and a half minute subsequent scrub using chlorhexidine (Analysis 14.1)

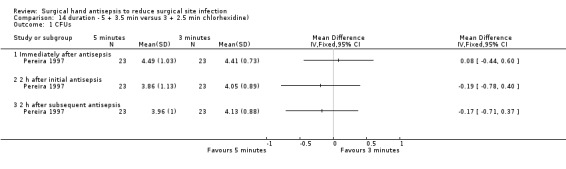

In Pereira 1997, there was no clear difference in the number of CFUs at any time point reported, whether immediately after the initial antisepsis (MD 0.08, 95% CI − 0.44 to 0.60), 2 hours after the initial antisepsis (MD − 0.19, 95% CI − 0.78 to 0.40) or 2 hours after subsequent antisepsis (MD − 0.17, 95% CI − 0.71 to 0.37); see Analysis 14.1.

14.1. Analysis.

Comparison 14 duration ‐ 5 + 3.5 min versus 3 + 2.5 min chlorhexidine), Outcome 1 CFUs.

Very low quality evidence due to risk of bias of attrition bias; imprecision and indirectness of outcome.

Comparison 6 summary: duration of surgical antisepsis

Outcome data were only available for CFUs. One study reported evidence of fewer CFUs on hands after using a 3 minute rather than 2 minute chlorhexidine scrub. Another study reported fewer CFUs after a 3 minute alcohol rub compared with a 5 minute alcohol rub; evidence was low quality in both cases. One study reported that 3 minute subsequent scrubs with aqueous chlorhexidine (following initial scrubs) were more effective in reducing the number of CFUs on hands than 30 second subsequent scrubs; this difference was not observed with povidone iodine treatments used in the same way: estimates from this study was classed as being of very low quality. Other comparisons reported no clear differences in number of CFUs.

Comparison 7: surgical hand antisepsis using a nail pick versus surgical hand antisepsis not using a nail pick (1 trial)

One three‐arm trial compared the effect of surgical hand antisepsis using a nail pick with surgical hand antisepsis alone (Tanner 2009). The study randomised 164 participants to one of three groups. All groups scrubbed with two measured doses of 2 ml aqueous chlorhexidine gluconate 4% (Hibiscrub) for 1 minute per dose; the total scrub time, which was observed and timed, was 2 minutes. One group performed only this surgical hand antisepsis. A second group used a disposable nail pick to clean their nails under running water before the hand antisepsis procedure. The third group used a disposable nail brush to clean their nails under running water before the hand antisepsis procedure. Participants then undertook circulating duties in the operating room for one hour but did not participate in any surgeries.

Outcomes

Surgical site infection

Not reported

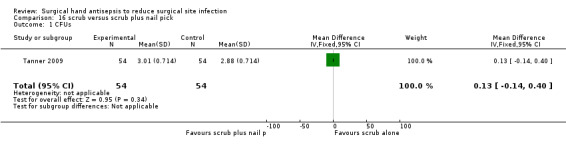

Number of colony forming units (CFUs)

There was no clear evidence of a difference between nail pick and no nail pick in the number of CFU detected after one hour on the dominant hands of participants (MD 0.13, 95% CI − 0.14 to 0.40; Analysis 15.1).

15.1. Analysis.

Comparison 15 scrub versus scrub plus brush, Outcome 1 CFUS.

Very low quality evidence ‐ downgraded once due to imprecision and once due to indirectness of outcome and further again for indirectness as no surgery was performed.

Comparison 8 surgical hand antisepsis using a brush versus surgical hand antisepsis not using a brush (1 trial)

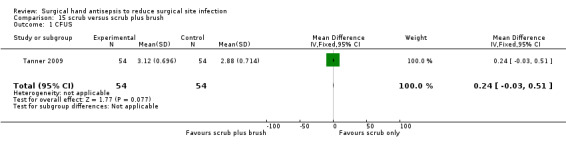

In the same three‐arm trial (Tanner 2009) compared the effect of surgical hand antisepsis and using a brush with surgical hand antisepsis alone. Participants were allocated to groups as described above. There was no clear evidence of a difference between using and not using a brush during hand antisepsis on the number of CFUs (MD 0.24, 95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.51; Analysis 16.1).

16.1. Analysis.

Comparison 16 scrub versus scrub plus nail pick, Outcome 1 CFUs.

Very low quality evidence; downgraded once due to imprecision and once due to indirectness of outcome and further again for indirectness as no surgery was performed.

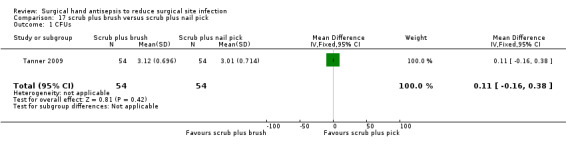

Comparison 9: surgical hand antisepsis using a nail pick versus surgical hand antisepsis using a brush (1 trial)

In the same three‐arm trial (Tanner 2009) compared the effect of surgical hand antisepsis using a nail pick with surgical hand antisepsis using a brush. There was no difference in the number of CFUs detected after 1 hour on the dominant hands of participants who used a brush before hand antisepsis compared with those who used a nail pick before hand antisepsis (MD 0.10, 95% CI ‐0.17 to 0.37; Analysis 17.1).

17.1. Analysis.

Comparison 17 scrub plus brush versus scrub plus nail pick, Outcome 1 CFUs.

Very low quality evidence ‐ downgraded once due to imprecision and once due to indirectness of outcome and further again for indirectness as no surgery was performed.

Summary of Comparisons 7 to 9: Surgical hand antisepsis using a nail pick and brush

There was no clear evidence of a difference in CFUs when a nail pick was compared with a brush or with no pick or brush.

Brief overview of findings

| Comparison | Evidence | SSI | GRADE ASSESSMENT | CFUs (on hands) | GRADE ASSESSMENT |

|

Comparison 1: basic hand hygiene versus alcohol rub containing additional active ingredients |

1 study | There was no clear evidence of a difference between treatments: RR 0.97 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.23) (Nthumba 2010) | Moderate quality evidence | Not reported | — |

| Comparison 2:different aqueous scrub solutions: chlorhexidine gluconate versus povidone iodine | 4 studies | Not reported | — | In 4 comparisons (3 studies: Furukawa 2005; Herruzo 2000; Pereira 1990), there was evidence of lower CFU counts immediately following scrubs with chlorhexidine, and in Pereira 1990, also after subsequent scrubbing. In 1 comparison (1 study) there was no evidence of a difference in the CFU count between an aqueous scrub of chlorhexidine gluconate and an aqueous scrub of povidone iodine plus triclosan (Pereira 1997). |

Low quality evidence for Furukawa 2005 and Herruzo 2000 and very low quality evidence for Pereira 1990 and Pereira 1997 |

| Comparison 3: comparison of different alcohol rubs containing additional active ingredients | 2 studies | Not reported | — | 1 study reported small mean difference values with imprecision around estimates at the 3 time points reported (Pereira 1997). We could not verify the findings of 1 study, which study authors reported as not statistically significant (Gupta 2007). | Very low quality evidence |

| Comparison 4: aqueous scrubs versus alcohol‐only rubs | 1 study | RR 0.56 (95% CI 0.23 to 1.34) (Al‐Naami 2009) The estimates was imprecise, and it was not possible to rule out an effect in either direction. |

Very low quality evidence | Not reported | — |