Abstract

We developed a new enzyme immunoassay (rpEIA) for use in determining the seroprevalence of chancroid. Three highly conserved outer membrane proteins from Haemophilus ducreyi strain 35000 were cloned, overexpressed, and purified from Escherichia coli for use as antigens in the rpEIA. Serum specimens from patients with and without chancroid were assayed to determine optimum sensitivity and specificity and to establish cutoff values. On the basis of these data, rpEIA was found to be both sensitive and specific when used to test a variety of serum specimens from patients with genital ulcers and urethritis and from healthy blood donors.

The sexually transmitted disease (STD) chancroid is caused by Haemophilus ducreyi. H. ducreyi is a fastidious, slow-growing gram-negative rod, which is known for its inability to synthesize heme. Recent reviews of chancroid and H. ducreyi are available (1, 21, 37). The incubation period for chancroid is between 4 and 7 days, when a small inflammatory papule or pustule containing polymorphonuclear leukocytes may be seen. The pustule soon ruptures, resulting in the loss of the epidermis, exposure of the dermis, and formation of an ulcer containing large numbers of organisms and inflammatory cells. Noticeably absent is the dissemination of H. ducreyi, which may be due, in part, to the lowered optimum growth temperature of H. ducreyi, 33°C. This may explain its predilection for the skin.

Recent epidemiologic evidence from Africa clearly demonstrates that chancroid is a risk factor for the spread of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) among heterosexuals (13, 14, 25), and several biological factors have been proposed to account for this. The ulcers of chancroid contain CD4+ T cells, and the virus has been isolated from chancroidal ulcers (17, 26), establishing these lesions as a portal of entry for HIV. HIV-infected patients may also have greater numbers of ulcers than non-HIV-infected patients. The semen from HIV-positive patients coinfected with chancroid contains higher levels of HIV than semen from HIV-positive patients without chancroid (4). The resolution of treated chancroid lesions is prolonged in HIV-infected patients relative to the resolution of those in HIV-uninfected patients (4). Thus, antibiotic-treated HIV-infected patients with chancroid may be infectious for a longer period of time for both etiologic agents. Taken together, all of these factors may contribute to the observed cotransmission and prevalence of these two diseases in sub-Saharan Africa (29); the term “infectious synergy” was coined to describe this phenomenon (38).

The clinical diagnosis of chancroid is inaccurate (6, 33). In addition, isolation of H. ducreyi from ulcer specimens is insensitive (21). However, the detection of H. ducreyi DNA in ulcer specimens by PCR has been shown to be significantly more sensitive than detection by culture (16, 39). Unfortunately, neither of these methods is readily available in areas of the world where chancroid is endemic, such as Africa and Asia.

Several studies have used enzyme immunoassays (EIA) that employ complex antigens to determine the seroprevalence of chancroid in different populations (2, 8, 24, 30). In some of these studies, cross-reacting antibodies present in serum specimens from control patients made interpretation of the results difficult (3, 28) and led to the requirement for adsorbing the serum to remove these cross-reactive antibodies (adEIA). To circumvent this problem, we have expressed the genes encoding three outer membrane proteins of H. ducreyi strain 35000 and have purified the proteins to use them as antigens. Serum specimens from patients with chancroid, other genital ulcerative diseases (GUD) (including possible syphilis), and urethritis and specimens from healthy blood donors in the United States were tested for the presence of antibodies to these three proteins using an EIA. We have termed this method rpEIA. The recombinant proteins used in this study were the hemoglobin receptor (HgbA) (9, 10), the heme receptor (TdhA) (34), and the H. ducreyi D15 homolog (D15) (11, 18; K. Thomas, B. Olsen, C. E. Thomas, and C. Elkins, unpublished data). Antibodies to the three outer membrane proteins were detected in serum specimens from all groups, but the prevalence was highest in specimens from patients with chancroid. To date, no reliable serologic test which can differentiate between persons who have had chancroid and those who have not exists. The results presented in this study suggest the possibility that these purified recombinant proteins or other as yet undescribed proteins may be useful for studies on the seroprevalence of chancroid.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

Bacterial strains used in this study are shown in Table 1. For routine growth, H. ducreyi was maintained on chocolate agar plates (9). Large-volume cultures of H. ducreyi and outer membrane isolation were performed as previously described (9).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or phenotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli K-12 | ||

| DH5αMCR | recA gyrB | Bethesda Research Laboratories |

| BL21(DE3) pLysS | F−ompT hsDs(rBmB−) gal dcm(DE3) pLysS (Cmr) | Novagen |

| Nova Blue (DE3) | endA1 hsdR17(rK12 mK12) supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 lac [F′ proA+B+ lacIqZΔM15::Tn10(Tcr)](DE3) | Novagen |

| H. ducreyi 35000 | Wild type | Stanley Spinolaa |

| Plasmids | ||

| pET30a | T7 expression vector; Kanr | Novagen |

| pUNCH 671 | tdhA; in pET30a | This work |

| pUNCH 672 | hgbA; in pET30a | This work |

| pUNCH 1235 | D15; in pET30a | This work |

| pCRII | PCR cloning vector; Kanr Ampr | In vitrogen |

Indiana University. Originally obtained from William Schalla, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Escherichia coli strains were maintained on Luria-Bertani agar plates with antibiotic selection where appropriate. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations for E. coli: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 30 μg/ml; kanamycin, 30 μg/ml.

Construction of plasmids for expression of H. ducreyi outer membrane proteins.

Previously, it had been shown that high-level expression of gonococcal outer membrane protein I (Por) was possible without toxicity when the por gene lacking a leader sequence was cloned behind a T7-inducible promoter (27). Expression of Por without a leader sequence resulted in the accumulation of large quantities of protein in cytoplasmic inclusion bodies. A similar strategy was used to construct recombinant clones expressing the full-length, mature H. ducreyi genes for HgbA, TdhA, and D15.

In the first step, each gene was amplified by PCR using the primers shown in Table 2. These primers were designed with unique restriction sites for in-frame fusion to the coding sequence for the hexahistidine leader of the expression plasmid pET30a; the first amino acid of each H. ducreyi sequence was the N terminus of the mature protein. PCR products were ligated into plasmid pCRII and transformed into E. coli DH5αMCR. White colonies were analyzed by restriction, and at least four containing the appropriately sized insert were selected. Inserts were removed following digestion with the appropriate restriction endonucleases and ligated into pET30a plasmids that had been cut with the same enzymes (Table 2). After transformation into E. coli [BL21(DE3) pLysS or Nova Blue (DE3)] and induction of recombinant protein synthesis with isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (IPTG), several transformants were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blotting. These blots were probed with individual affinity-purified antipeptide sera to identify clones expressing the full-length product (9, 34; Thomas et al., unpublished data).

TABLE 2.

Primers used for PCR

| Primer | Sequencea | Size of PCR product (bp) (length of protein product [amino acids])b | Restriction site |

|---|---|---|---|

| HgbA 5′ | CCGGATCCGAAAGCAATATGCAAACA | 2,868 (992) | BamHI |

| HgbA 3′ | GCGGCCGCTTAGAAAGTGATCTCTGC | NotI | |

| TdhA 5′ | GATGGATCCGAGGATAATCCCAAAAAT | 2,180 (780) | BamHI |

| TdhA 3′ | GCGGCCGCGTCGTTTTATGAAGTCAA | NotI | |

| D15 5′ | GGATCCGAATTCGCACCATTTGTAGTAAAAGAT | 2,361 (819) | BamHI |

| D15 3′ | CAGTTGGCAGCACATTCTAATTCGAACGCCGGCG | NotI |

H. ducreyi sequence is shown in boldface, and restriction sites are underlined.

Each protein product includes an N-terminal hexahistidine leader encoded by the vector. The vector leader sequence is fused to the first mature amino acid of each H. ducreyi protein, and all three proteins end with the native terminal phenylalanine. The vector leader adds 40, 40, and 42 amino acids to the mature protein sequences of H. ducreyi HgbA, TdhA, and D15, respectively.

Expression and purification of recombinant H. ducreyi outer membrane proteins.

Gene expression was induced by the method of Qi et al. (27). Briefly, 1-liter Luria-Bertani broth cultures were grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5 and IPTG was added to 2 mM. After 30 min, rifampin (200 μg/ml) was added, and incubation continued for two additional hours. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, and the inclusion bodies containing the recombinant proteins were isolated as previously described (27) with the following modifications. The cell pellet was resuspended into 20 ml of 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) and frozen. After being thawed, the cells were ruptured by passage through a French press twice and then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 min. The resulting pellet containing the inclusion bodies was resuspended in binding buffer (Novagen) and centrifuged several times until the orange color of the pellet (residual rifampin) was removed. The recombinant protein, which was the predominant protein in the inclusion bodies (generally >90% pure) was further purified on Ni chelate columns under denaturing conditions (6 M urea) as described by Novagen. Following purification, urea was removed by gradual dialysis at 4°C to a concentration of 2 M. Zwittergent 3,14 was then added to the retentate to 5%, and dialysis was continued to remove the urea and putatively renature the proteins. During each step of the procedure, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (2 mM) was added, and the protein was kept at 4°C.

Miscellaneous procedures.

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting (immunoblotting) were performed as previously described (9). The antisera used were affinity-purified antipeptide sera to HgbA, TdhA, and D15 (9, 34; Thomas et al., unpublished data).

Specimens.

A total of 330 serum specimens were obtained and stored at −70°C until tested. Serum specimens from STD clinic patients residing in areas of high chancroid endemicity in South Africa were obtained from Ronald C. Ballard (South African Institute for Medical Research, Johannesburg, South Africa). These specimens were from (i) patients with PCR-confirmed chancroid (n = 40), (ii) patients with genital ulcers due to syphilis or genital herpes as determined by PCR (n = 29), and (iii) patients with urethritis (n = 126) of whom 52% were HIV infected. All serum specimens were initially obtained for routine diagnostic purposes from men presenting to STD clinics in Carletonville, Durban, and Johannesburg, South Africa, between October 1993 and January 1994. Serum specimens (n = 45) used as negative controls were obtained from healthy blood donors in Atlanta, Georgia. Additional serum specimens consisting of 45 Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL)-positive and 45 VDRL-negative sera were selected from among those submitted to the Georgia State Health Department for syphilis serology.

EIA. (i) rpEIA.

Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid HisSorb plates (Qiagen, Santa Clarita, Calif.) were selected after evaluating various microtiter plates from several manufacturers. Wells were coated with the recombinant H. ducreyi proteins according to the manufacturer's instructions. Each recombinant protein was diluted in coating buffer (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS], pH 7.4, containing 1 M urea) to a concentration of 1 μg/ml, and 100 μl of the diluted protein was added to each well. After incubation for 2 h at room temperature, wells were washed three times with PBS, pH 7.4, containing 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (plate wash buffer). Serum specimens were diluted 1:200 in PBS, pH 7.4, containing 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20 and 1% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum; 100 μl was added to each of two wells. Plates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature and then washed three times with plate wash buffer. One hundred microliters of a 1:1,000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human immunoglobulin G (IgG) (EIA grade; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) was added to each well. Bound conjugate was detected spectrophotometrically at 405 nm after the addition of 100 μl ABTS (2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazolinesulfonic acid) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions (1 μg/ml in ABTS buffer solution) (Calbiochem, La Jolla, Calif.) and incubation for 15 min at room temperature. EIA were optimized by the use of receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves (20, 39), which were constructed by plotting the sensitivity versus the false-positive rate at increments of 0.05 sensitivity. A cutoff value for each antigen-specific assay was selected based on optimal performance.

(ii) adEIA.

The adEIA was performed as described previously (5).

RESULTS

Cloning, expression, and purification of recombinant H. ducreyi outer membrane proteins.

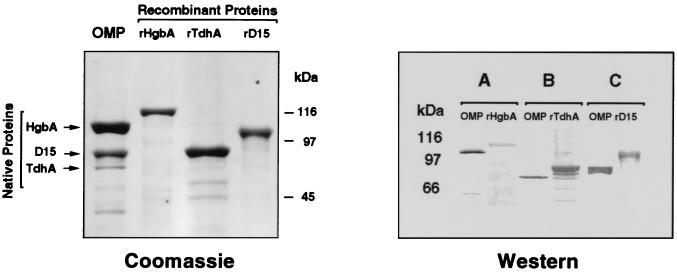

The coding sequences for mature forms of HgbA, TdhA, and D15 were amplified by PCR and cloned into pCRII using the primers shown in Table 2. Inserts were directionally subcloned in frame into the pET30a expression vector, and E. coli strains containing the λ lysogen DE3 were transformed. Induction of gene expression in E. coli with IPTG followed by inhibition of RNA polymerase with rifampin (27) resulted in the expression of each recombinant protein such that it was the predominant protein observed on SDS-PAGE gels of whole-cell extracts (data not shown). Inclusion bodies containing the recombinant protein were isolated and purified under denaturing conditions by metal chelate chromatography. SDS-PAGE followed by staining with Coomassie blue was used to compare the relative mobilities of native H. ducreyi outer membrane proteins with those of the purified recombinant proteins (Fig. 1). SDS-PAGE was also used to assess the relative purity of the recombinant proteins.

FIG. 1.

(Left panel) SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining of H. ducreyi outer membrane proteins and purified recombinant proteins. H. ducreyi strain 35000 was grown under heme-limiting conditions to induce synthesis of HgbA and TdhA. Recombinant His-tagged proteins were purified from E. coli as described in the text. Lanes: OMP, H. ducreyi outer membrane proteins (30 μg); rHgbA, rTdhA, rD15, purified recombinant proteins (2 μg each). Note the larger sizes of the hexahistidine leader-containing recombinant proteins compared to their respective native proteins. (Right panel) Western blots of H. ducreyi outer membrane proteins and recombinant proteins. Blots A, B, and C were probed with affinity-purified antipeptide IgG to HgbA, TdhA, or D15, respectively. In blot A, only 5 μg of outer membrane protein was loaded to visualize the abundant HgbA protein. In blots B and C, 30 μg of outer membrane protein was loaded to visualize the less abundant TdhA and D15 proteins. Each lane of recombinant protein contained 200 to 400 ng of protein.

To confirm that the purified recombinant proteins contained peptide sequences derived from the N-terminal Edman degradation amino acid sequence data (HgbA and D15) or the deduced amino acid sequence (TdhA) of these proteins, Western blots were probed with the relevant affinity-purified IgG from rabbits which had been immunized with synthetic peptides. The results (Fig. 1) demonstrate that the affinity-purified IgG recognized both the native and recombinant forms of each protein. Several smaller immunoreactive bands were also observed in preparations of purified recombinant proteins. These bands could be the result of proteolysis, alternative start sites for transcription, or premature termination (transcription or translation) due to the high AT content of H. ducreyi DNA. These immunoreactive bands were not observed in preparations prepared from E. coli containing pET30a alone, suggesting that they were not contaminants. Others (27) have observed these smaller proteins in similar preparations from a variety of recombinant proteins. The H. ducreyi outer membrane proteins HgbA, TdhA, and D15 are very basic and relatively large. These proteins are made still more basic by the addition of the hexahistidine leader sequence (10, 26, 27). Examination of SDS-PAGE gels stained with Coomassie blue after electrotransfer to nitrocellulose revealed that the majority of the recombinant protein (especially recombinant HgbA [rHgbA]) remained in the gel, whereas the smaller proteins were transferred to the nitrocellulose (data not shown). Thus, the smaller proteins are overrepresented in the Western blots (compare left and right panels in Fig. 1).

Optimization of EIA.

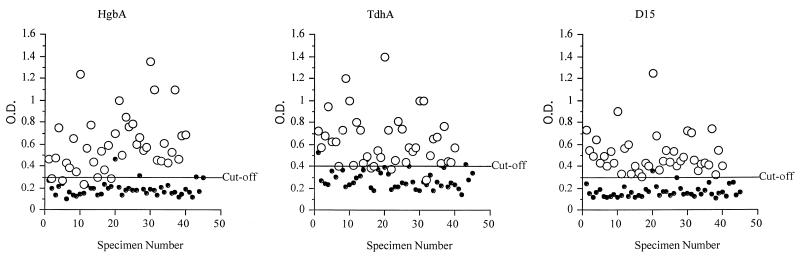

Serum specimens from patients with PCR-confirmed chancroid (n = 40) and from healthy U.S. blood donors (n = 45) were employed to optimize the performance characteristics of the assays. Healthy U.S. blood donor sera were used as negative controls instead of South African PCR-negative sera because chancroid is highly endemic in South Africa compared to the United States. A negative PCR result indicates only the lack of current chancroid infection and does not indicate if prior infection had occurred in an individual. Since the possibility of prior chancroid infection in South African individuals was relatively high compared to that for U.S. individuals, we concluded that the use of U.S. sera was appropriate and proper. Using ROC plots, cutoff values which maximized the sensitivity and specificity of each recombinant antigen-specific assay were selected. The ratios of the mean OD405 of the serum specimens from patients with chancroid to the mean OD405 of the serum specimens from healthy blood donors were 3.16, 2.21, and 3.00 for HgbA, TdhA, and D15, respectively. The cutoff values (OD405) for each antigen-specific assay, based on optimal performance, were 0.30 (HgbA), 0.40 (TdhA), and 0.30 (D15). The OD values for the 40 serum specimens from patients with chancroid and the 45 serum specimens from healthy blood donors are shown in Fig. 2. Serum specimens from 35 of 40 (88%) patients with chancroid had antibodies to all three recombinant antigens. Serum specimens that exhibited a high OD reading against one antigen consistently had high OD readings against the other two antigens. The five remaining chancroid patients had antibodies to only two of the recombinant antigens (three patients had antibodies to TdhA and D15, and two patients had antibodies to HgbA and D15). All of the patients with PCR-confirmed chancroid had antibody levels to D15 that were above the cutoff; however, 4 of 40 (10%) and 3 of 40 (7.5%) lacked antibodies to HgbA and TdhA, respectively. The prevalence of antibodies to these recombinant proteins was relatively uncommon among healthy blood donors; only one individual had antibodies to D15 while three and four donors, respectively, had antibodies to HgbA and TdhA. Thus, to enhance the specificity of these assays, only seroreactivity to HgbA and D15 was used for some comparisons (Table 3).

FIG. 2.

Serum specimens from 40 patients with lesions positive for H. ducreyi by M-PCR (open circles) and 45 normal human sera (solid circles) were tested in rpEIA using rHgbA, rTdhA, and rD15 protein antigens. O.D., OD405. The cutoff value for each antigen was established by ROC analysis (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Prevalence of antibodies to H. ducreyi HgbA and D15 among South African and U.S. populations with different levels of risk for chancroid

| Presence of antibody to:

|

No. (%) of specimens positive or antibody in:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-risk South African populations

|

U.S. populations

|

|||||||

| HgbA | D15 | Hda (n = 40) | Other GUDb (n = 29) | Urethritis

|

High risk (VDRL+) (n = 45) | Medium risk (VDRL−) (n = 45) | Low risk (healthy blood donors) (n = 45) | |

| HIV+ (n = 66) | HIV− (n = 60) | |||||||

| + | + | 37 (93) | 5 (17) | 13 (20) | 11 (19) | 2 (4) | 3 (7) | 1 (2) |

| + | − | 0 | 4 (14) | 4 (6) | 6 (10) | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | 0 |

| − | + | 3 (7) | 2 (7) | 3 (5) | 4 (7) | 8 (18) | 1 (2) | 0 |

| − | − | 0 | 18 (62) | 46 (70) | 38 (64) | 33 (73) | 40 (89) | 44 (98) |

Hd, patients with PCR-confirmed chancroid.

Other GUD, patients with PCR-confirmed genital herpes or syphilis.

The mean OD405 for each antigen using serum specimens from patients with PCR-confirmed chancroid was significantly higher (P < 0.0001) than the mean OD405 for serum specimens from any of the other patient groups examined (Table 4). Thus, the mean OD was related to the prevalence and likelihood of having chancroid.

TABLE 4.

Mean OD values for antigen-specific rpEIA for serum specimens from South African and U.S. patient populations with different levels of risk for chancroid

| Group | Mean OD405 ± SD for:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| HgbA | TdhA | D15 | |

| South Africa | |||

| Chancroid (n = 40) | 0.61 ± 0.26 | 0.64 ± 0.24 | 0.51 ± 0.18 |

| Other (n = 29) | 0.34 ± 0.16 | 0.34 ± 0.16 | 0.27 ± 0.11 |

| Urethritis | |||

| HIV+(n = 66) | 0.27 ± 0.20 | 0.29 ± 0.17 | 0.25 ± 0.15 |

| HIV−(n = 60) | 0.28 ± 0.18 | 0.27 ± 0.14 | 0.24 ± 0.12 |

| United States | |||

| VDRL+(n = 45) | 0.20 ± 0.10 | 0.32 ± 0.18 | 0.25 ± 0.14 |

| VDRL−(n = 45) | 0.21 ± 0.19 | 0.23 ± 0.17 | 0.24 ± 0.20 |

| Blood donors (n = 45) | 0.19 ± 0.06 | 0.29 ± 0.09 | 0.17 ± 0.05 |

Serum specimens from South African GUD patients (n = 29) with PCR-confirmed genital herpes or syphilis were also tested to determine the prevalence of antibodies to H. ducreyi HgbA and D15; 19 of 29 (66%) of these patients were also infected with HIV (Table 3). Among these patients, 11 of 29 (38%) had antibodies to at least one of the antigens, and of these, 9 of 11 had antibodies to HgbA (5 had antibodies to HgbA and D15, and 4 had antibodies to HgbA) and 2 of 11 had antibodies to only D15. There was no significant effect of HIV infection status on seroreactivity to these antigens (data not shown). Compared to the results obtained from GUD patients with chancroid, the mean OD405 of the serum specimens from those with genital herpes or syphilis was 40 to 50% lower for each antigen (Table 4). Among all GUD patients, rpEIA for the presence of antibodies to HgbA and D15 had a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 62% compared with multiplex PCR (M-PCR) for H. ducreyi.

Serum specimens from South African STD clinic patients with urethritis or GUD were also tested for the presence of antibodies to HgbA and D15 (Table 3). The mean OD405s for the antigens were similar and were less than the mean OD405s for patients with chancroid or for those with genital herpes or syphilis (Table 4). There was no significant effect of HIV infection status on the seroreactivity to these antigens. Most of the patients with urethritis 84 of 126 (67%) lacked antibodies to these proteins as measured by EIA. Of those with antibodies, 24 of 126 (19%) had antibodies to HgbA and D15; 10 of 126 (7.9%) had antibodies to HgbA, and 7 of 126 (5.6%) had antibodies to D15.

Chancroid is endemic in Georgia and is responsible for a small percentage of GUD in patients attending STD clinics (36). Thus, serum specimens randomly selected from among those submitted to the Georgia State Health Department laboratory for syphilis serology (45 VDRL positive and 45 VDRL negative) were tested for the presence of antibodies to HgbA and D15. The results (Table 3) showed that patients with VDRL-positive sera were significantly more likely to have antibodies to HgbA and D15 than those with VDRL-negative sera (12 of 45 [26%] versus 5 of 45 [11%]; P <0.001). Overall, 17 of 90 (18.9%) of these randomly selected specimens that were submitted for syphilis serology had antibodies to either HgbA or D15.

Comparison of rpEIA and adEIA.

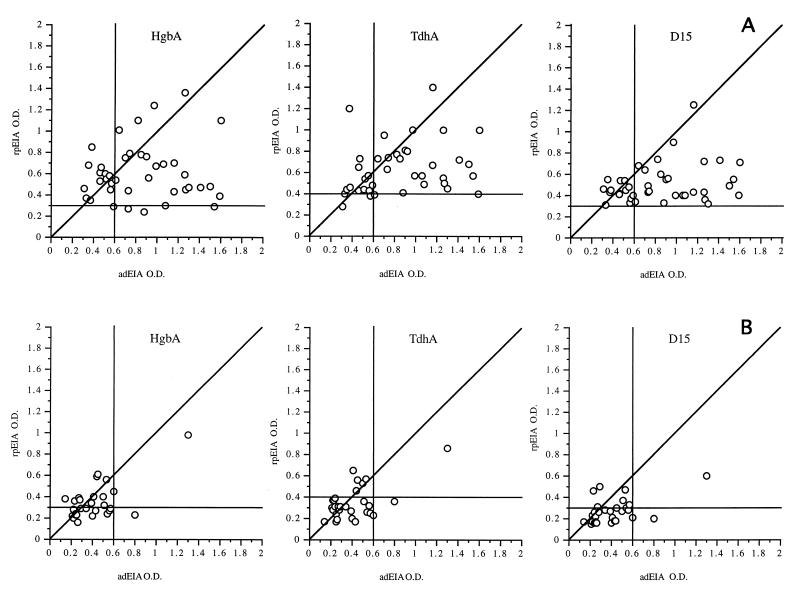

Serum specimens positive for H. ducreyi (n = 40) and for herpes simplex virus or Treponema pallidum (n = 29) by PCR from patients who attended STD clinics in South Africa were assayed by both the rpEIA and adEIA. A comparison of the assay results is shown in Fig. 3A and B. There was little correlation between the results of these assays when serum specimens from patients with chancroid were used. The correlation coefficients (r) were 0.07, 0.24, and 0.25 for HgbA, TdhA, and D15, respectively. The rpEIA was more sensitive than the adEIA in identifying GUD patients with chancroid. However, among patients with chancroid, the OD from the adEIA was generally greater than that from the rpEIA. This difference is likely due to the detection of antibodies to multiple antigens. In contrast, the rpEIA detected the presence of low levels of antibodies to HgbA, D15, and TdhA in several specimens from South African patients with genital herpes or syphilis. These antibodies may reflect past infection with H. ducreyi. There was a higher, but not significant, correlation between the two assays with specimens from this group of African patients (r = 0.66, 0.60, and 0.50 for HgbA, TdhA, and D15, respectively).

FIG. 3.

Correlation between adEIA and rpEIA. Forty M-PCR-positive (A) and 29 M-PCR-negative (B) specimens were subjected to adEIA or rpEIA.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we sought to develop an improved serological assay (rpEIA) for use in seroprevalence studies of chancroid. The adEIA, which has been used in most seroprevalence studies, is cumbersome and difficult to standardize, and its results may be difficult to interpret. In the adEIA, serum specimens are adsorbed with a mixture of antigens (sorbent) prepared from a variety of related and unrelated bacterial species. Some of the bacteria used as the sorbent (e.g., Haemophilus influenzae) have been recently shown to have certain genes encoding outer membrane proteins that are similar in structure and function to those of H. ducreyi. These genes from other bacteria encode proteins related structurally to HgbA (19, 22), TdhA (12), D15, OmpA1 and OmpA2 (23), P6 lipoprotein (7, 31), and the LspA proteins (32) from H. ducreyi. Undoubtedly, additional H. ducreyi antigens whose homologs are also present in other members of the Pasteurellaceae will be identified. Thus, the adsorption step may actually remove important antibodies. In addition, the antigen used in the adEIA is a crude extract of H. ducreyi. Since microtiter plate wells have a limited binding capacity, the amount of each antigen bound in a crude extract is small relative to the amount bound using a homogenous protein antigen. In addition, two of the three proteins used in rpEIA are heme regulated (HgbA and TdhA). Since the adEIA whole-cell antigen used was prepared from H. ducreyi grown under high-heme conditions, HgbA and TdhA are either not present or are present in reduced amounts. It is likely that a combination of these factors was responsible for the differences observed when rpEIA and adEIA results were compared (Fig. 3). The rpEIA detected a higher proportion of patients with current chancroid and a higher proportion of patients who were likely to have had chancroid in the past.

Based on a limited number of published studies, the sensitivity of the rpEIA was greater than that of either the adEIA or the lipooligosaccharide (LOS) EIA among patients with M-PCR-confirmed chancroid in Mississippi (53 versus 48%, respectively) (5) or in Dakar, Senegal (71 versus 59%, respectively) (35). Differences in the apparent sensitivity and specificity may be due, in part, to different patient populations, the prevalence of chancroid in those populations, and the availability of health care. Likewise, the relatively low specificity of the rpEIA may reflect the high prevalence of prior chancroid infection among STD clinic patients in South Africa. Relatively high specificities of adEIA (71%) and LOS EIA (89%) were observed among GUD patients from Mississippi, where previous chancroid incidence was low. The relatively high LOS EIA sensitivity may be due to a relatively short half-life for anti-LOS IgG.

The rpEIA is a method that can be standardized and used to directly compare populations from different geographic areas and risk groups. Moreover, the use of purified recombinant protein antigens offers several technical advantages. Tens of milligrams of recombinant protein can be obtained from 1 liter of bacterial culture. We have found that 1 mg of the protein is sufficient to coat 5,000 wells. Thus, a single laboratory can serve as a repository for purified proteins or precoated microtiter plates for use by distant laboratories. If additional antigens are later found to be useful, their addition to this assay would represent a trivial modification.

Results obtained using serum specimens from patient populations residing in areas of high and low chancroid endemicity provide strong evidence for the high sensitivity and specificity of the rpEIA. In this limited study, the antibody response to HgbA and D15 was found to correlate with the risk for chancroid (Tables 3 and 4). Although H. influenzae possesses homologs of HgbA, TdhA, and D15 and although humans are often exposed to this bacterium, we did not observe significant reactivity to these proteins among a group of healthy blood donors. There are several explanations for this finding. Using a variety of polyclonal antisera, we were unable to detect significant cross-reactivity between the H. ducreyi HgbA and its homolog in H. influenzae (9, 15; unpublished data). In addition, polyclonal antisera to H. influenzae D15 reacted poorly with H. ducreyi D15 (unpublished data). Alternatively, antibodies to H. influenzae proteins are acquired during childhood and are below detectable levels in most adults. H. ducreyi TdhA is poorly expressed in vitro (34). However, significant levels of antibody to TdhA are present in the serum of patients with chancroid, suggesting that this protein is antigenic and expressed in vivo. The low levels of antibodies to TdhA that were found in serum from a few healthy individuals suggests that this antigen may be less useful in discriminating between individuals who were previously infected and those who were never infected with H. ducreyi.

The proportion of patients with antibodies to HgbA and D15 was related to the prevalence as well as the risk for chancroid. All of the men who presented to STD clinics in South Africa with chancroid had antibody levels to HgbA or D15 that were above the cutoff value. In contrast, only 2% (1 of 45) of healthy blood donors from Atlanta, Georgia, had antibodies to these proteins. During the same time period, South African men presenting to these STD clinics with genital herpes, primary syphilis, or urethritis had a 30 to 40% prevalence of antibodies to HgbA and D15. The level of antibodies in this group of patients was less than that observed in patients with chancroid, suggesting that chanroid may have been acquired at an earlier date. Serum specimens from individuals in the United States were divided into groups based on their risk for GUD. Among serum specimens submitted to the Georgia State Public Health Laboratory for syphilis serology, those that were VDRL positive had a 2.5-fold higher prevalence of antibodies than those that were VDRL negative. Overall, individuals with VDRL-negative serum specimens were considered to be at medium risk for GUD, as an undetermined number of these specimens were obtained for legal screening requirements and were from individuals who were likely to be at low risk for syphilis.

While the presence of antibodies to HgbA, TdhA, and D15 is strongly correlated with current infection with H. ducreyi, we wish to emphasize that this test was designed to be used for seroprevalence studies and not for the diagnosis of current infection. The limitations of this study are that we were unable to obtain a reliable history of prior chancroid from these patients and thus can only assign a relative risk for prior chancroid. Additionally, studies are needed to determine the persistence of these antibodies after treatment and the effect of reinfection on antibody level.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ronald Ballard and Felicity Flack for the generous gift of antibodies. We thank Annice Rountree for her expert technical assistance.

The work presented was supported by a R29-AI 40263 and a AI 31496 to C.E.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albritton W L. Biology of Haemophilus ducreyi. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:377–389. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.4.377-389.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alfa M J, Olson N, Degagne P, Plummer F, Namaara W, MaClean I, Ronald A R. Humoral immune response of humans to lipooligosaccharide and outer membrane proteins of Haemophilus ducreyi. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:1206–1210. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.5.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alfa M J, Olson N, Degagne P, Slaney L, Plummer F, Namaara W, Ronald A R. Use of an adsorption enzyme immunoassay to evaluate the Haemophilus ducreyi specific and cross-reactive humoral immune response of humans. Sex Transm Dis. 1992;19:309–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behets F M T, Liomba G, Lule G, Dalabetta G, Hoffman I F, Hamilton H A, Moeng S, Cohen M S. Sexually transmitted diseases and human immunodeficiency virus control in Malawi: a field study of genital ulcer disease. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:451–454. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.2.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen C Y, Mertz K J, Spinola S M, Morse S A. Comparison of enzyme immunoassays for antibodies to Haemophilus ducreyi in a community outbreak of chancroid in the United States. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:1390–1395. doi: 10.1086/516471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dangor Y, Ballard R C, Exposto F L, Fehler G, Miller S D, Koornhof H J. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of genital ulcer disease. Sex Transm Dis. 1990;17:184–189. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199010000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deich R A, Metcalf B J, Finn C W, Farley J E, Green B A. Cloning of genes encoding a 15,000-dalton peptidoglycan-associated outer membrane lipoprotein and an antigenically related 15,000-dalton protein from Haemophilus influenzae. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:489–498. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.2.489-498.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desjardins M, Thompson C E, Filion L G, Ndinya A J O, Plummer F A, Ronald A R, Piot P, Cameron D W. Standardization of an enzyme immunoassay for human antibody to Haemophilus ducreyi. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2019–2024. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.8.2019-2024.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elkins C. Identification and purification of a conserved heme-regulated hemoglobin-binding outer membrane protein from Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1241–1245. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1241-1245.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elkins C, Chen C J, Thomas C E. Characterization of the hgbA locus of Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2194–2200. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.6.2194-2200.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flack F S, Loosmore S, Chong P, Thomas W R. The sequencing of the 80-kDa D15 protective surface antigen of Haemophilus influenzae. Gene. 1995;156:97–99. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00049-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fleischmann R, Adams M, White O, et al. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science. 1995;269:496–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenblatt R M, Lukehart S A, Plummer F A, Quinn T C, Critchlow C W, Ashley R L, D'Costa L J, Ndinya A J O, Corey L, Ronald A R, et al. Genital ulceration as a risk factor for human immunodeficiency virus infection. AIDS. 1988;2:47–50. doi: 10.1097/00002030-198802000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jessamine P G, Ronald A R. Chancroid and the role of genital ulcer disease in the spread of human retroviruses. Med Clin N Am. 1990;74:1417–1431. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30488-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin H, Ren Z, Pozsgay J M, Elkins C, Whitby P W, Morton D J, Stull T L. Cloning of a DNA fragment encoding a heme-repressible hemoglobin-binding outer membrane protein from Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3134–3141. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3134-3141.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson S R, Martin D H, Cammarata C, Morse S A. Alterations in sample preparation increase sensitivity of PCR assay for diagnosis of chancroid. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1036–1038. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.4.1036-1038.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kreiss J K, Coombs R, Plummer F, Holmes K K, Nikora B, Cameron W, Ngugi E, Ndinya-Achola J O, Corey L. Isolation of the human immunodeficiency virus from genital ulcers in Nairobi prostitutes. J Infect Dis. 1989;160:380–384. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.3.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loosmore S M, Yang Y P, Coleman D C, Shortreed J M, England D M, Klein M H. Outer membrane protein D15 is conserved among Haemophilus influenzae species and may represent a universal protective antigen against invasive disease. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3701–3707. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3701-3707.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maciver I, Latimer J L, Heim H H, Muller-Eberhard U, Hrkal Z, Hansen E J. Identification of an outer membrane protein involved in utilization of hemoglobin-haptoglobin complexes by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3703–3712. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3703-3712.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Metz C E. Basic principles of RDC analysis. Semin Nucl Med. 1978;8:283–298. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2998(78)80014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morse S A. Chancroid and Haemophilus ducreyi. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1989;2:137–157. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morton D J, Whitby P W, Jin H, Ren Z, Stull T L. Effect of multiple mutations in the hemoglobin- and hemoglobin-haptoglobin-binding proteins, HgpA, HgpB, and HgpC, of Haemophilus influenzae type b. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2729–2739. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2729-2739.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Munson R S, Jr, Grass S, West R. Molecular cloning and sequence of the gene for outer membrane protein P5 of Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4017–4020. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.9.4017-4020.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Museyi K, Van D E, Vervoort T, Taylor D, Hoge C, Piot P. Use of an enzyme immunoassay to detect serum IgG antibodies to Haemophilus ducreyi. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:1039–1043. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.5.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plummer F A, Simonsen J N, Cameron D W, Ndinya-Achola J O, Kreiss J K, Gakinya M N, Waiyaki P, Cheang M, Piot P, Ronald A R, Ngugi E N. Cofactors in male-female sexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:233–239. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plummer F A, Wainberg M A, Plourde P, Jessamine P, D'Costa L J, Wamola I A, Ronald A R. Detection of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) in genital ulcer exudate of HIV-1-infected men by culture and gene amplification. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:810–811. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.4.810. . (Letter.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qi H L, Tai J Y, Blake M S. Expression of large amounts of neisserial porin proteins in Escherichia coli and refolding of the proteins into native trimers. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2432–2439. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.6.2432-2439.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roggen E L, Piot P. Haemophilus ducreyi and other etiological agents of non-treponemal genital ulcer disease. Ups J Med Sci. 1991;50(Suppl.):52–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ronald A R, Albritton W. Chancroid and Haemophilus ducreyi. In: Holmes K K, Mardh P-A, Sparling P F, Wiesner P J, editors. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: McGraw-Hill; 1990. pp. 263–272. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schalla W O, Sanders L L, Schmid G P, Tam M R, Morse S A. Use of dot-immunobinding and immunofluorescence assays to investigate clinically suspected cases of chancroid. J Infect Dis. 1986;153:879–887. doi: 10.1093/infdis/153.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spinola S, Hiltke T, Fortney K, Shanks K. The conserved 18,000-molecular-weight outer membrane protein of Haemophilus ducreyi has homology to PAL. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1950–1955. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.1950-1955.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.St. Geme J W, III, Kumar V V, Cutter D, Barenkamp S J. Prevalence and distribution of the hmw and hia genes and the HMW and Hia adhesins among genetically diverse strains of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1998;66:364–368. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.364-368.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sturm A W, Stolting G J, Cormane R H, Zanen H C. Clinical and microbiological evaluation of 46 episodes of genital ulceration. Genitourin Med. 1987;63:98–101. doi: 10.1136/sti.63.2.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas C E, Olsen B, Elkins C. Cloning and characterization of tdhA, a locus encoding a TonB-dependent heme receptor from Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4254–4262. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4254-4262.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trees D L, Morse S A. Chancroid and Haemophilus ducreyi: an update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:357–375. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.3.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wasserheit J N. Interrelationships between human immunodeficiency virus infection and other sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Dis. 1991;19:61–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.West B, Wilson S M, Changalucha J, Patel S, Mayaud P, Ballard R C, Mabey D. Simplified PCR for detection of Haemophilus ducreyi and diagnosis of chancroid. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:787–790. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.4.787-790.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang Y, Thomas W R, Chong P, Loosmore S M, Klein M H. A 20-kilodalton N-terminal fragment of the D15 protein contains a protective epitope(s) against Haemophilus influenzae type a and type b. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3349–3354. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3349-3354.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zweig M, Ashwood E, Galen R, Plous R, Rabinowitz M. Assessment of the clinical accuracy of laboratory tests using received operating characteristics (ROC) plots; approved guideline. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1995. [Google Scholar]