Abstract

The cellular fatty acid compositions of 29 strains of Yersinia pestis representing the global diversity of this species have been analyzed by gas-liquid chromatography to investigate the extent of fatty acid polymorphism in this microorganism. After culture standardization, all Y. pestis strains studied displayed some major fatty acids, namely, the 12:0, 14:0, 3-OH-14:0, 16:0, 16:1ω9cis, 17:0-cyc, and 18:1ω9trans compounds. The fatty acid composition of the various isolates studied was extremely homogeneous (average Bousfield's coefficient, 0.94) and the subtle variations observed did not correlate with epidemiological and genetic characteristics of the strains. Y. pestis major fatty acid compounds were analogous to those found in other Yersinia species. However, when the ratios for the 12:0/16:0 and 14:0/16:0 fatty acids were plotted together, the genus Yersinia could be separated into three clusters corresponding to (i) nonpathogenic strains and species of Yersinia, (ii) pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica isolates, and (iii) Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and Y. pestis strains. The grouping of the two latter species into the same cluster was also demonstrated by their high Bousfield's coefficients (average, 0.89). Therefore, our results indicate that the fatty acid composition of Y. pestis is highly homogeneous and very close to that of Y. pseudotuberculosis.

Plague, one of the most devastating infectious diseases in human history, will not be soon eradicated despite the major advances made in the knowledge of its causative agent (Yersinia pestis), its reservoir (wild rodents), its vector (fleas), and the advent of antibiotic therapy (35). This gram-negative bacillus was initially classified in the genus Pasteurella before being taxonomically reclassified in the genus Yersinia, a member of the family Enterobacteriaceae. The genus Yersinia includes eleven species (6), three of which are human and animal pathogens: Y. pestis, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, and Yersinia enterocolitica.

Despite the wide variety of animal hosts and insect vectors and the capacity to survive in the environment (29), Y. pestis forms a phenotypically highly homogeneous species which contains only one serotype, one phage type, and three biotypes (varieties). Based on historical records and on the persistence of ancient plague foci, Devignat (15) suggested that each biotype of Y. pestis was responsible for a different pandemic: biotype Antiqua (glycerol positive, nitrate positive) for the first pandemic, biotype Medievalis (glycerol positive, nitrate negative) for the second pandemic, and biotype Orientalis (glycerol negative, nitrate positive) for the third pandemic. Recent results obtained with different molecular typing methods such as rRNA gene restriction pattern analysis (ribotyping) (18) and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (27) argued for Devignat's hypothesis. A relationship was established between biotypes and ribotypes (18). Moreover, several ribotypes were distinguished within each biotype, indicating a higher genotypic than phenotypic diversity in this species.

Determination of fatty acid composition by gas chromatography (GC) has been shown to be a simple method of identification and classification of different bacterial species (1) and could represent a useful alternative for further investigating the phenotypic diversity of Y. pestis. GC was previously used to study some strains of this species (2, 21), but this technique was applied to a small number of isolates, most often from the same geographical origin and/or biotype. It was thus not possible from the results of these works to evaluate the extent of fatty acid diversity in Y. pestis.

In the present study, after standardization of the different parameters of the technique, the fatty acid composition of 29 strains of Y. pestis isolated at different times from various geographical areas and having different biotypes and ribotypes were analyzed. We demonstrate a high homogeneity of the fatty acid composition of this species. We also show that the subtle differences observed in fatty acid patterns among Y. pestis strains do not correlate with their biotypes, ribotypes, and epidemiological characteristics. Finally, we demonstrate that based on the analysis of the fatty acid composition of various isolates, the genus Yersinia can be separated into three distinct clusters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

A total of 29 strains of Y. pestis from the collection of the French Reference Laboratory and World Health Organization Collaborating Center for Yersinia (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France) were used. The characteristics of these strains are given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the 29 strains of Y. pestis used for cellular fatty acid analysis

| Strain no. | Pasteur Institut no. | Geographic origina | Year of isolation | Host | Biotype | Ribotypeb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 613 | 548 | Burma | 1970 | UNc | Orientalis | G |

| 579 | 195 | Bombay | 1908 | Human | Orientalis | B |

| 569 | EXU 56 | Brazil | 1967 | Rodent | Orientalis | B |

| 1049 | 197 | Dalat | 1965 | Human | Orientalis | G |

| 685 | H.10 | Hamburg | 1952 | UN | Orientalis | B |

| 696 | H.26 | Hamburg | 1952 | UN | Orientalis | B |

| 544 | Keny. MMI | Kenya | UNc | Human | Antiqua | F |

| 552 | Margar | Kenya | UN | Human | Antiqua | M |

| 520 | PKR VIII | Kurdistan | 1947 | Rodent | Medievalis | O |

| 304 | 6/69+ | Madagascar | 1969 | Human | Orientalis | B |

| 529 | 112 | Madagascar | 1951 | Human | Orientalis | B |

| 1511 | 197/96 | Madagascar | 1996 | Human | Orientalis | B |

| 1491 | 167/96 | Madagascar | 1996 | Human | Orientalis | B |

| 643 | 4/83 | Madagascar | 1983 | Human | Orientalis | Q |

| 649 | 12/85 | Madagascar | 1985 | Human | Orientalis | Q |

| 1512 | 198/96 | Madagascar | 1996 | Rodent | Orientalis | Q |

| 666 | 100-92 | Madagascar | 1992 | Human | Orientalis | R |

| 635 | 11/85 | Madagascar | 1985 | Human | Orientalis | R |

| 668 | 41/93 | Madagascar | 1993 | Human | Orientalis | R |

| 1484 | 61/94 | Madagascar | 1994 | Human | Orientalis | T |

| 1482 | 57/94 | Madagascar | 1994 | Human | Orientalis | T |

| 28 | EV76 | Madagascar | 1926 | Human | Orientalis | UN |

| 1537 | 254 | Namibia | 1984 | Human | Orientalis | V |

| 940 | 65-30 | Nha Trang | 1965 | UN | Orientalis | G |

| 513 | 64-65 | Nha Trang | 1964 | UN | Orientalis | G |

| 507 | 55.720 | Saigon | 1955 | UN | Orientalis | E |

| 532 | 55.801 | Saigon | 1955 | UN | Orientalis | E |

| 524 | Fay. Sy | Senegal | 1944 | Human | Orientalis | D |

| 572 | A1122 | United States | <1942 | Human | Orientalis | B |

The names of the countries or towns are those used at the time of the strain isolation and have been kept for strain designation.

Ribotypes according to Guiyoule and collaborators (18).

UN, unknown.

Growth conditions.

Bacterial growth conditions (temperature, aeration, and incubation time) were standardized and adjusted as closely as possible to optimal growth conditions. The growth medium was a mixture of casein-peptone and soymeal-peptone broth (Caso medium; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). For each strain, a 9-ml bacterial preculture at the late exponential growth phase (incubation at 28°C for 24 h with no shaking) was used to inoculate a 50-ml liquid growth medium with a concentration of 5 × 107 CFU/ml calculated from the optical density at 600 nm. These cultures were incubated for a further 24 h at 28°C with no shaking, allowing the population to reach the early stationary growth phase where the fatty acid composition is rather stable (14, 30, 41). It was important to use the same growth temperature of 28°C to be able to compare the fatty acids patterns of Y. pestis with those of other Yersinia species computerized in our data base. The cultures were autoclaved for 1 h at 121°C (37) and cooled at room temperature. The bacterial suspensions were centrifuged at 1,800 × g for 30 min, and pellets were washed twice with 5 ml of Ringer solution (Merck). The saline-washed cells were suspended in the Ringer solution and immediately stored at 3°C until fatty acid extraction.

Chemical procedures and GC.

Cellular fatty acids were extracted and transformed into fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) as described by Miller and Berger (28) and Moss (32). The principle of this technique is equivalent to that used in the MIDI system (Hewlett-Packard, Avondale, Pa.). The hydrolysis procedure used was critical for extraction, since acid hydrolysis degrades cyclopropane acids while base hydrolysis fails to liberate all the amine-linked hydroxy acids (24). Vulliet and collaborators (44) noted that acid hydrolysis of the cyclopropane fatty acids of the genus Yersinia produces methoxyester artifacts. Because hydroxy and cyclopropane fatty acids have been shown to be relevant chemotaxonomic markers of bacteria (25) and since cyclopropane acids were shown to be among the major fatty acids of Y. pestis, a base hydrolysis was chosen in this work. GC analyses for FAMEs were carried out on a Delsi DI 200 gas chromatograph equipped with a split-splitless injector, a flame ionization detector, and a 50-m CP-SIL-5 capillary column (0.32-mm inner diameter and 0.13-mm film thickness; Chrompack, Middleburgh, The Netherlands), which allows the recovery of hydroxy acids and the resolution of most isomers. Actual analysis conditions were as follows: injection temperature, 235°C; detector temperature, 250°C; column temperature, 45°C for 1 min 30 s, then increased by 39.9°C/min to 140°C for 2 min, held at 140°C for 2 min, and then increased to 235°C at a rate of 3°C/min. Nitrogen was used as a carrier gas (methane retention time, 2.715 min).

Numerical methods.

Peak areas and percentages of each FAME were calculated with a model C-R4A integrator (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The major fatty acids were identified from a comparison of their peak retention times to those of known standards with the Bacterial Acid Methyl Esters CP Mix 1114 (Supelco, Bellefonte, Pa.), which consists of a quantitative mixture of odd- and even-chain saturated FAMEs ranging from 9 to 20 carbons in length as well as a homologous series of hydroxy FAMEs with a free hydroxyl group at the second or third carbon atom. Identifications were also based on calculation of the equivalent chain length value for each fatty acid, by using its elution time in relation to the elution times of straight-chain saturated fatty acid standards (38). The SO overlap coefficient, also termed Bousfield's coefficient (7), was applied to compare fatty acid composition between strains. A high SO value between two strains indicates that their fatty acid compositions display a high degree of identity. This value is based on the degree of overlapping between two superimposed traces, both scaled to have the same total area of 100, and is calculated as SO(i,j) = 100 − 0.5Σ|xik − xjk|, where xik and xjk are the percentages of the fatty acid k for the and organisms i and j, respectively (12). SO coefficients calculated between each Y. pestis strain were converted to dendrogram form by the unweighted pair-group method for arithmetic averages (UPGMA) statistical method (12) with version 3.56c of the Neighbor-Joining–UPGMA software. In this distance method, the level of the branch which links two strains determines the correlation between the strains.

RESULTS

Reproducibility of the method.

By using these conditions, the reproducibility of GC analysis and extraction was expected to be high, with a SO value of 0.96 (14). Five strains of Y. pestis (613, 520, 507, 569, and 1357) were extracted twice to evaluate the reproducibility of our technique. The mean reproducibility value of the GC analysis and extraction procedure corresponded to an SO value of 0.97, indicating a high degree of reproducibility with our extraction procedure. The slight differences observed between different experiments could be attributed to minor components (representing less than 0.5% of the total fatty acids) which did not always appear in the chromatograms. Under the GC conditions applied in this work, the minimum chromatographic area had to be higher than 100,000 μV/s to avoid SO lowering. At the extraction level, the nonquantitative liberation of some hydroxy fatty acids by saponification and the possible degradation of cyclic fatty acids could also lead to a decrease in the SO value (24). We noted that the Y. pestis biomass was less important than that of other Yersinia species, most probably because this species grows more slowly.

Fatty acid composition of Y. pestis.

The fatty acid compositions of the 29 Y. pestis strains studied are presented in Table 2, and the computed SO values between each strains are given in Table 3.

TABLE 2.

Cellular fatty acid composition of Yersinia pestis strains: major components

| Strain of Y. pestis | Ribotype | Amounta of indicated compoundb

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12:0 | 3-OH- 12:0 | 2-OH- 12:0 | 14:0 | a15:1 | 15:0 | 3-OH- 14:0 | 16:1ω9c | 16:0 | 17:0-cyc | 17:0 | 18:2ω9,12 | 18:1ω9c | 18:1ω9t | 18:0 | 19:0-cyc | ||

| 304 | B | 1.25 | 0.19 | — | 1.32 | 0.49 | 0.14 | 6.40 | 30.40 | 35.03 | 8.61 | — | 0.78 | 0.80 | 11.16 | 1.47 | — |

| 529 | B | 2.19 | — | — | 1.09 | 0.39 | 0.26 | 11.84 | 33.49 | 29.60 | 7.20 | — | 0.97 | 0.84 | 9.90 | 1.24 | — |

| 569 | B | 1.18 | 0.38 | — | 0.63 | 0.48 | — | 7.58 | 34.42 | 32.95 | 5.64 | — | 0.87 | 1.04 | 11.79 | 1.42 | — |

| 572 | B | 2.09 | — | — | 1.64 | 0.39 | — | 10.23 | 32.94 | 31.86 | 8.45 | — | 0.68 | — | 10.08 | 1.01 | — |

| 579 | B | 1.69 | — | — | 1.96 | 0.51 | 0.20 | 7.81 | 32.19 | 34.87 | 9.26 | — | 1.10 | 0.81 | 7.69 | 0.92 | — |

| 685 | B | 2.35 | — | — | 3.22 | 0.37 | 0.14 | 8.16 | 39.40 | 35.23 | 5.49 | — | 0.31 | 0.20 | 3.38 | 0.58 | — |

| 696 | B | 3.15 | 0.08 | — | 2.10 | 0.39 | 0.16 | 13.08 | 31.40 | 33.69 | 7.03 | — | 0.75 | 0.59 | 4.88 | 1.81 | — |

| 1491 | B | 1.07 | — | — | 1.38 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 10.12 | 28.44 | 35.50 | 8.23 | — | 0.76 | 0.74 | 10.93 | 1.76 | — |

| 1511 | B | 1.30 | — | — | 1.65 | 0.22 | 0.15 | 10.63 | 32.37 | 34.37 | 7.00 | — | 0.56 | 0.10 | 9.62 | 1.62 | — |

| 524 | D | 1.22 | — | 0.15 | 0.71 | 0.45 | — | 5.67 | 34.78 | 31.74 | 3.60 | — | 0.91 | 0.75 | 17.07 | 1.86 | — |

| 507 | E | 2.18 | — | — | 1.57 | 0.47 | 0.13 | 8.55 | 31.31 | 34.54 | 8.40 | — | 0.93 | 0.90 | 8.68 | 1.47 | — |

| 532 | E | 2.96 | — | — | 1.94 | 0.45 | 0.17 | 11.49 | 40.20 | 32.62 | 1.88 | — | 0.56 | — | 6.10 | 0.92 | — |

| 544 | F | 1.23 | — | — | 1.75 | 0.43 | — | 8.60 | 35.62 | 34.23 | 8.22 | — | 0.36 | 0.54 | 7.00 | 0.71 | — |

| 513 | G | 2.74 | — | 0.09 | 1.75 | 0.47 | 0.16 | 13.98 | 35.91 | 30.29 | 5.25 | — | 0.46 | — | 7.25 | 0.79 | — |

| 613 | G | 2.70 | — | — | 1.51 | 0.39 | 0.10 | 11.30 | 36.19 | 31.02 | 5.18 | — | 0.58 | 0.55 | 8.71 | 1.33 | — |

| 940 | G | 1.82 | — | — | 1.62 | 0.39 | 0.21 | 11.30 | 30.89 | 33.58 | 8.26 | — | 0.64 | 0.46 | 8.32 | 1.24 | — |

| 1049 | G | 1.15 | — | 0.39 | 1.07 | 0.48 | 0.11 | 8.45 | 34.24 | 32.77 | 5.47 | — | 0.89 | 0.97 | 11.80 | 1.43 | — |

| 552 | M | 3.25 | — | — | 1.51 | 0.59 | 0.19 | 10.90 | 18.24 | 34.21 | 17.77 | — | 0.83 | 0.68 | 8.48 | 1.30 | 0.44 |

| 520 | O | 1.73 | — | 0.37 | 2.51 | 0.48 | 0.21 | 8.47 | 27.02 | 37.86 | 11.07 | — | 0.65 | 0.79 | 7.24 | 1.20 | — |

| 643 | Q | 2.65 | — | 0.07 | 2.00 | 0.40 | 0.14 | 12.57 | 37.14 | 28.01 | 5.21 | — | 0.60 | 0.43 | 8.46 | 1.08 | — |

| 649 | Q | 2.14 | — | — | 2.29 | 0.43 | 0.14 | 11.37 | 32.58 | 36.52 | 8.06 | — | 0.66 | 0.23 | 3.91 | 0.95 | — |

| 1512 | Q | 1.07 | — | — | 1.39 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 11.02 | 30.99 | 34.08 | 7.46 | — | 0.62 | 0.49 | 10.19 | 1.48 | — |

| 635 | R | 1.56 | — | — | 1.40 | 0.31 | 0.15 | 12.48 | 31.82 | 33.83 | 6.75 | — | 0.54 | 0.43 | 9.04 | 1.15 | — |

| 666 | R | 1.89 | — | — | 1.69 | 0.29 | 0.14 | 11.85 | 32.81 | 32.84 | 6.87 | — | 0.54 | 0.44 | 8.90 | 1.18 | — |

| 668 | R | 1.04 | — | — | 1.18 | 0.22 | 0.15 | 10.73 | 29.14 | 33.33 | 7.26 | 0.13 | 0.89 | 0.81 | 12.46 | 1.73 | — |

| 1482 | T | 1.11 | — | — | 1.38 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 10.72 | 29.09 | 33.24 | 8.01 | — | 0.27 | 0.95 | 10.48 | 2.79 | — |

| 1484 | T | 1.11 | — | — | 1.38 | 0.25 | 0.11 | 11.74 | 29.35 | 34.40 | 7.99 | — | 0.80 | 0.71 | 9.99 | 1.29 | — |

| 1537 | V | 1.84 | — | — | 1.59 | 0.34 | 0.20 | 11.17 | 31.84 | 32.37 | 6.93 | 0.13 | 0.67 | 0.55 | 9.83 | 1.53 | — |

| 28 | UNc | 2.54 | — | — | 1.80 | 0.43 | — | 12.19 | 30.82 | 31.93 | 9.27 | — | 0.57 | 0.58 | 7.96 | 1.00 | — |

Values are percentages of total fatty acids and are arithmetic means; —, unintegrated or nonexistent peak.

Number before the colon, number of carbon atoms; number after the colon, number of double bonds; ω9cis, double-bond position from hydrocarbon end of cis isomer; ω9t, double-bond position from hydrocarbon end of trans isomer; cyc, cyclopropane fatty acid; 2-OH or 3-OH, hydroxy group at carbon 2 or 3.

UN, unknown.

TABLE 3.

Bousfield's coefficient SO values between Y. pestis strains

| Strain |

SO valuesa for Y. pestis strain

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 304 | 529 | 569 | 572 | 579 | 685 | 696 | 1491 | 1511 | 524 | 507 | 532 | 544 | 513 | 613 | 940 | 1049 | 552 | 520 | 643 | 649 | 1512 | 635 | 666 | 668 | 1482 | 1484 | 1537 | 28 | |

| 304 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 529 | 0.902 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 569 | 0.936 | 0.927 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 572 | 0.925 | 0.958 | 0.931 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 579 | 0.936 | 0.911 | 0.908 | 0.867 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 685 | 0.857 | 0.858 | 0.884 | 0.874 | 0.884 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 696 | 0.891 | 0.919 | 0.887 | 0.918 | 0.917 | 0.890 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1491 | 0.953 | 0.908 | 0.910 | 0.932 | 0.932 | 0.847 | 0.902 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1511 | 0.932 | 0.943 | 0.931 | 0.962 | 0.946 | 0.885 | 0.936 | 0.947 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 524 | 0.889 | 0.880 | 0.934 | 0.885 | 0.853 | 0.831 | 0.834 | 0.859 | 0.878 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 507 | 0.933 | 0.914 | 0.894 | 0.934 | 0.963 | 0.863 | 0.928 | 0.954 | 0.951 | 0.841 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 532 | 0.827 | 0.886 | 0.874 | 0.891 | 0.867 | 0.918 | 0.898 | 0.836 | 0.888 | 0.845 | 0.863 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||||||

| 544 | 0.914 | 0.908 | 0.925 | 0.938 | 0.952 | 0.918 | 0.910 | 0.907 | 0.940 | 0.872 | 0.924 | 0.901 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||||

| 513 | 0.911 | 0.929 | 0.930 | 0.966 | 0.937 | 0.883 | 0.946 | 0.922 | 0.971 | 0.875 | 0.940 | 0.909 | 0.931 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||||

| 613 | 0.899 | 0.950 | 0.943 | 0.953 | 0.886 | 0.896 | 0.903 | 0.863 | 0.907 | 0.868 | 0.889 | 0.934 | 0.908 | 0.929 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||

| 940 | 0.934 | 0.942 | 0.913 | 0.957 | 0.955 | 0.875 | 0.948 | 0.941 | 0.960 | 0.855 | 0.963 | 0.890 | 0.936 | 0.968 | 0.912 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| 1049 | 0.930 | 0.933 | 0.990 | 0.936 | 0.914 | 0.885 | 0.891 | 0.915 | 0.937 | 0.930 | 0.900 | 0.882 | 0.928 | 0.937 | 0.908 | 0.916 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| 552 | 0.827 | 0.818 | 0.791 | 0.834 | 0.848 | 0.755 | 0.832 | 0.851 | 0.841 | 0.735 | 0.870 | 0.768 | 0.814 | 0.837 | 0.797 | 0.863 | 0.795 | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| 520 | 0.916 | 0.847 | 0.864 | 0.877 | 0.917 | 0.840 | 0.865 | 0.905 | 0.883 | 0.824 | 0.918 | 0.805 | 0.883 | 0.877 | 0.827 | 0.899 | 0.861 | 0.837 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| 643 | 0.845 | 0.937 | 0.892 | 0.912 | 0.875 | 0.886 | 0.902 | 0.853 | 0.902 | 0.856 | 0.874 | 0.918 | 0.896 | 0.930 | 0.962 | 0.907 | 0.899 | 0.783 | 0.816 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| 649 | 0.895 | 0.910 | 0.879 | 0.930 | 0.929 | 0.916 | 0.947 | 0.908 | 0.936 | 0.823 | 0.927 | 0.891 | 0.927 | 0.939 | 0.889 | 0.942 | 0.884 | 0.819 | 0.890 | 0.882 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| 1512 | 0.938 | 0.936 | 0.921 | 0.946 | 0.936 | 0.861 | 0.927 | 0.951 | 0.969 | 0.863 | 0.944 | 0.868 | 0.919 | 0.953 | 0.891 | 0.964 | 0.927 | 0.841 | 0.877 | 0.883 | 0.918 | 1.000 | |||||||

| 635 | 0.921 | 0.948 | 0.922 | 0.950 | 0.942 | 0.877 | 0.953 | 0.932 | 0.973 | 0.866 | 0.944 | 0.893 | 0.927 | 0.982 | 0.915 | 0.969 | 0.929 | 0.841 | 0.880 | 0.920 | 0.933 | 0.963 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 666 | 0.844 | 0.929 | 0.892 | 0.916 | 0.883 | 0.889 | 0.917 | 0.855 | 0.905 | 0.856 | 0.882 | 0.923 | 0.915 | 0.929 | 0.957 | 0.907 | 0.898 | 0.785 | 0.821 | 0.958 | 0.894 | 0.883 | 0.919 | 1.000 | |||||

| 668 | 0.934 | 0.922 | 0.927 | 0.929 | 0.916 | 0.834 | 0.910 | 0.964 | 0.947 | 0.883 | 0.944 | 0.846 | 0.895 | 0.933 | 0.874 | 0.939 | 0.933 | 0.836 | 0.873 | 0.864 | 0.890 | 0.951 | 0.938 | 0.867 | 1.000 | ||||

| 1482 | 0.938 | 0.928 | 0.919 | 0.941 | 0.928 | 0.839 | 0.914 | 0.966 | 0.951 | 0.864 | 0.953 | 0.853 | 0.908 | 0.938 | 0.877 | 0.953 | 0.925 | 0.848 | 0.884 | 0.869 | 0.901 | 0.960 | 0.942 | 0.868 | 0.970 | 1.000 | |||

| 1484 | 0.945 | 0.939 | 0.915 | 0.943 | 0.940 | 0.854 | 0.927 | 0.967 | 0.961 | 0.856 | 0.962 | 0.863 | 0.921 | 0.952 | 0.887 | 0.966 | 0.920 | 0.860 | 0.895 | 0.882 | 0.922 | 0.970 | 0.962 | 0.881 | 0.959 | 0.973 | 1.000 | ||

| 1537 | 0.930 | 0.930 | 0.910 | 0.948 | 0.910 | 0.856 | 0.923 | 0.923 | 0.949 | 0.897 | 0.917 | 0.883 | 0.896 | 0.957 | 0.926 | 0.941 | 0.944 | 0.816 | 0.847 | 0.920 | 0.907 | 0.941 | 0.951 | 0.919 | 0.942 | 0.939 | 0.936 | 1.000 | |

| 28 | 0.913 | 0.941 | 0.895 | 0.956 | 0.949 | 0.863 | 0.946 | 0.917 | 0.937 | 0.849 | 0.954 | 0.892 | 0.918 | 0.960 | 0.917 | 0.970 | 0.901 | 0.857 | 0.895 | 0.918 | 0.931 | 0.938 | 0.956 | 0.923 | 0.919 | 0.931 | 0.945 | 0.937 | 1.000 |

The values were calculated by the method of Bousfield (7).

All Y. pestis isolates displayed some major fatty acids, namely the 12:0, 14:0, 3-OH-14:0, 16:0, 16:1ω9cis, 17:0-cyc, and 18:1ω9trans compounds. The composition of these fatty acids is in general agreement with the data previously reported for Y. pestis by Asselineau (4) and Tornabene (41), although no β-hydroxypalmitate (β-OH-16:0) was found in the present work. We also noted that the 17:0-cyc fatty acid and its precursor 16:1 were the most important fatty acid compounds of Y. pestis. Our results are in agreement with those reported for other Yersinia species (3, 10, 21, 26) but differ from those of Samygin et al. (37), who found the same major components but in different proportions in Y. pestis. However, as pointed out by Jantzen and Lassen (21), the biosynthesis of cyclopropane fatty acids is much dependent on the growth stage of the bacterial populations. Differences in the bacterial growth phases could probably explain the discrepancies observed between the two studies in the amount of 17:0-cyc and 16:1 fatty acids, emphasizing the need of strictly standardized growth conditions. Using the values of these two acids for taxonomic purposes is therefore questionable, even though a standard error of less than 5% was obtained when they were computed together.

The minor fatty acids detected in the different strains of Y. pestis studied here, i.e., 3-OH-12:0, a15:1, 15:0, 17:0, 18:0, 18:2ω9,12, 18:1ω9cis, and 19:0-cyc were similar to those reported in other works (4, 34, 37). However, the 20:0, 20:4, and the unidentified fatty acid (multibranched 20:0, OH-14:0, OH-18:0, 10:0, 13:0, or 14:1) reported by Sheremet et al. (39) were not detected in our study.

Lipopolysaccharide fatty acid composition.

Characterization of the lipopolysaccharide fatty acid composition of EV-derived vaccine strains of Y. pestis by Alimova and Boikova (3) and by Vasyurenko and Znamenskii (43) indicated that these vaccine strains have a more complex pattern of normal, branched, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated chains in the range 11:0 to 24:0, inclusively, than wild strains. Samygin et al. (36) reported that this difference could be at least partly attributable to the presence of laurinic acid in the attenuated EV-derived vaccine strains, a component absent from the virulent Y. pestis. Dalla Venezia et al. (13) and Frolov et al. (17) also reported that the concentration of 3-OH-14:0 was higher in the EV-derived vaccine strain than in other Y. pestis isolates. In this study, we did not notice major differences in the fatty acid composition of the EV76 vaccine strain compared to other Y. pestis strains, except for a higher content of 3-hydroxytetradecanoic acid, as previously reported (36).

Fatty acid pattern comparisons.

Comparison of the fatty acid patterns of the 29 isolates of Y. pestis showed that most of the SO overlapping coefficients were greater than 0.90 (Table 3), with an average of 0.94. These data indicate a very high degree of fatty acid conservation in Y. pestis.

We used our laboratory bacterial FAME composition library, which includes more than 120 species belonging mostly to food-borne bacteria (45), to compare the FAME composition of Y. pestis with that of other bacteria. It was previously demonstrated that, by using similarly standardized conditions, Bousfield's coefficients of less than 0.85 are indicative of two different species (14). Bousfield's coefficient values between Y. pestis and Y. pseudotuberculosis were too high (average SO, 0.89) to discriminate between these two species if unknown strains were to be tested against our laboratory database. Fatty acid compositions of Y. pestis and Y. pseudotuberculosis (12:0, 14:0, 16:0, 16:1ω9cis, 17:0-cyc, 18:1, and 19:0-cyc compounds) were found to be highly similar. The slight differences observed between the two species corresponded to the relative amounts of the major phospholipids and the presence of additional minor components in Y. pseudotuberculosis. A lower level of 12:0 and 14:0 fatty acids and a higher level of 16:0 fatty acid were found in Y. pseudotuberculosis lipopolysaccharide, while the lipopolysaccharide of Y. pestis was constituted mainly of 3-OH-14:0, 16:1ω9cis, and 16:0 compounds and, to a lesser extent, of 12:0 and 14:0 compounds (13 and 17 and this study). In contrast, Y. pestis could easily be distinguished from Y. enterocolitica and related species by FAME pattern comparisons (average SO, 0.75). One exception was Yersinia bercovieri, which had high Bousfield's coefficient values (SO, 0.88 in some cases). Compared to Y. pestis, Y. enterocolitica and related species exhibited higher concentrations of 12:0 and 14:0 fatty acids, lower concentrations of 17:0-cyc and its precursor 16:1ω9cis, and 18:0, and a presence of 19:0-cyc compounds (26). When comparing the fatty acid composition of Y. pestis with those of other gram-negative bacterial species present in our database, the highest Bousfield's coefficient found was 0.81 for Pantoea agglomerans and Aeromonas hydrophila.

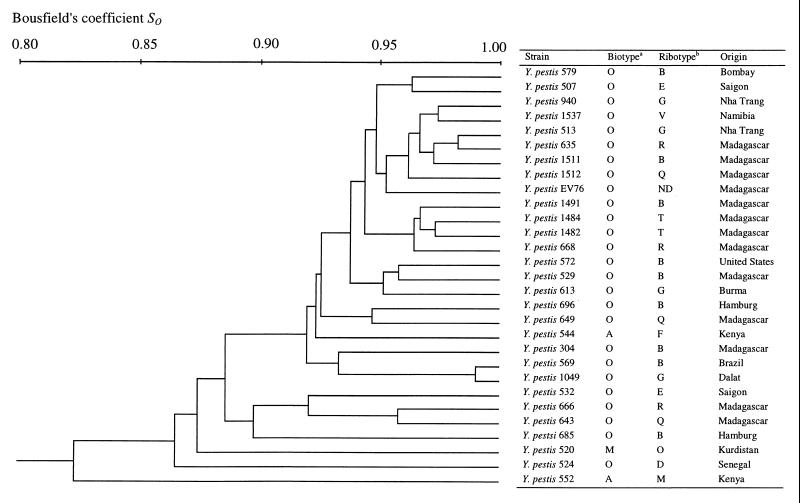

In order to determine whether fatty acid composition could serve to establish a phylogenetic linkage between the different Y. pestis strains, the SO values obtained between pairs of strains were used to construct a dendrogram by the UPGMA method (Fig. 1). No correlation between fatty acid patterns and other characteristics of the Y. pestis strains analyzed (biotype, geographical origin, host, and ribotype) could be drawn.

FIG. 1.

Dendrogram based on Bousfield's coefficient values (SO) between the 29 strains of Y. pestis studied and generated by cluster analysis (UPGMA). (a) O, Orientalis; M, Medievalis; A, Antiqua. (b) Ribotypes previously determined by Guiyoule and collaborators (19). ND, not determined.

DISCUSSION

Although determination of fatty acid composition by GC has proven to be a highly useful tool for analyzing different bacterial species (1), one of the major problems encountered with this technique is the difficulty in comparing results obtained by different laboratories. This was also the case for this study. Although a very high conservation of the fatty acid composition was noted among the 29 Y. pestis isolates studied here, differences in the presence of some major and minor compounds and in their relative proportions were found with previous studies. It is unlikely that these differences are due to strain variations, since the variety of the Y. pestis isolates studied here was large and since at least four laboratories, including our own, analyzed similar EV-derived strains. Most likely, the discrepancies observed result from the use of different experimental conditions. Accurate comparisons of fatty acid patterns of different bacteria can only be performed if the extraction procedure has been strictly standardized to optimize fatty acid stability and to get reproducible results. One of the most important parameters to control is the bacterial growth phase. For instance, high amounts of 16:1 and 18:1 fatty acids were found in exponentially growing cells of Y. pestis, while the proportion of cyclopropanoic acid increased corresponding to a decrease in the amount of olefinic acids in older cultures (5, 14, 22, 40). Another crucial parameter is the growth temperature which regulates the fatty acid composition and acts directly on the physical state and fluidity of the bacterial membrane (16, 21, 33, 40). An increase in temperature results in a higher proportion of saturated long-chain and cyclopropane fatty acids incorporated into the lipid membrane with a subsequent decrease in the proportions of unsaturated branched-chain and/or saturated short-chain fatty acids (11, 42). Bacteria change their fatty acid composition to maintain a degree of fluidity in their lipid membrane compatible with cellular growth and function (32). Since a highly reproducible technique is essential to allow inter- and intralaboratory comparisons of bacterial fatty acids by GC, it is essential to use extraction conditions that minimize variations in fatty acid composition. We found that fatty acid extraction done on unshaken bacterial populations harvested at the early stationary growth phase gave reproducible results because fatty acid composition is stable under such conditions (4, 14, 41). We also selected Caso broth as the growth medium because it did not produce artifacts due to the presence of fatty acids in the medium (45). In the particular case of Yersinia spp., a growth temperature of 28°C was found to be optimal for fatty acid comparison.

This study represents the first analysis of the fatty acid composition of a large number of Y. pestis strains with various epidemiological, phenotypic, and genotypic characteristics. This fatty acid composition was found to be highly conserved among the various isolates (Table 3), indicating that, as for other phenotypic markers such as phage type, serotype, and biotype, very little phenotypic heterogeneity is observed in Y. pestis, suggesting a high degree of clonality of this species. To determine whether the subtle fatty acid variations observed between strains reflected the evolution of this species, a phylogenetic tree based on the SO values was constructed. No correlation could be established between the fatty acid composition of these strains and their biotype, ribotype, host, year of isolation, or geographic origin (Fig. 1). These results suggest that the minor variations observed between strains may not reflect true differences in fatty acid composition but, rather, insignificant modifications occurring during bacterial growth or fatty acid extraction. Our data also indicate that determination of the fatty acid composition is not an appropriate typing method for Y. pestis and that techniques based on genetic markers such as ribotyping or pulsed-field gel electrophoresis are much more suitable to achieve this goal (18, 19, 27).

The major fatty acid components of Y. pestis (3-OH-14:0, 16:0, 16:1ω9cis, 17:0-cyc, and 18:ω9trans) were similar to those found in gram-negative bacteria and more specifically in Escherichia coli (4, 23, 41, 42). However, the fatty acid composition of Y. pestis differed from those of other Enterobacteriaceae by the absence of 19:0-cyc fatty acid (except for Y. pestis 552) and the presence, in small amounts, of 16:0 and 18:1ω9trans acids. We also found, in agreement with other reports (21, 43), a higher proportion of 16:1ω9cis and 3-OH-14:0 compounds in Y. pestis and only trace amounts of fatty acids with odd carbon numbers (i.e., 15:0 but not 17:0). 3-Hydroxytetradecanoic acid (3-OH-14:0) is the major component of the lipid A of the lipopolysaccharide of the genus Yersinia, and its high concentration differentiates this genus from other Enterobacteriaceae (17, 20). Thus, comparison of the FAME composition of Y. pestis with those of other bacterial genera clearly differentiated these two groups of bacteria.

Within the genus Yersinia, the relatively low proportions of 12:0 and 14:0 fatty acids were characteristic of the fatty acid spectrum of the Y. pestis lipopolysaccharide and differed from those of other Yersinia species. Determination of the amount of these two compounds may thus discriminate this species from other Yersinia. The cellular fatty acid composition of Y. pestis was also distinguishable from that of Y. enterocolitica and related species. In contrast, fatty acid compositions of Y. pestis and Y. pseudotuberculosis were very similar, and the FAME analysis method could not differentiate the two species. This similarity correlates with the close genetic relatedness of these species which have a GC content of 46 to 46.5%, as compared with 48 to 48.5% in other Yersinia, and which share a high degree of DNA relatedness (>90%) as determined by DNA-DNA hybridization (6, 8, 31). Therefore, our results indicate that FAME analysis can separate Y. pestis from Y. enterocolitica and related species but not from Y. pseudotuberculosis.

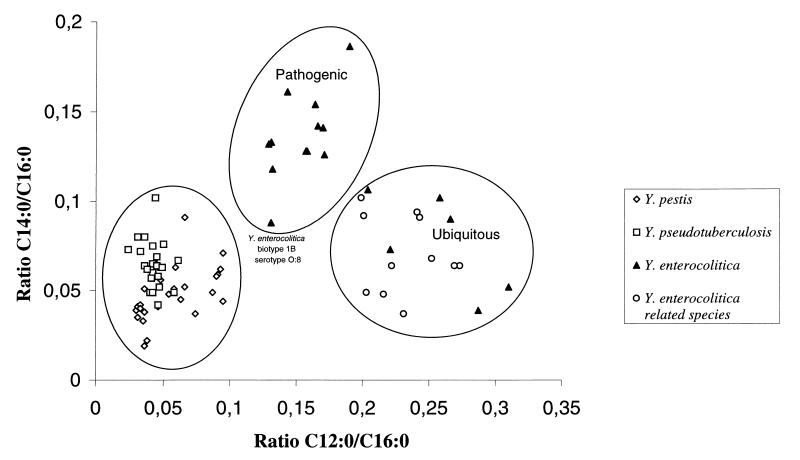

In a previous study of Y. pseudotuberculosis, Y. enterocolitica, and related species (9, 26), we demonstrated that by correcting the 12:0 and 14:0 fatty acid concentrations with the use of the 16:0 fatty acid concentration, which is one of the major fatty acids of Yersinia, two new ratios, namely the 12:0/16:0 and 14:0/16:0 values, could be used. In this work, by plotting these two ratios together, three clusters were observed within the genus Yersinia (Fig. 2). The first cluster contained the nonpathogenic strains of Y. enterocolitica (biotype 1A) and related species, the second cluster included pathogenic Y. enterocolitica strains (biotypes 1B and 2 to 5), and the third cluster was composed of Y. pseudotuberculosis and Y. pestis strains. Therefore, GC separates Yersinia strains based on their pathogenicity. These results also confirm the close genetic linkage of the two latter species. Nonetheless, although Y. pestis and Y. pseudotuberculosis belonged to the same cluster, they formed two close but not mixed subgroups that reflect their recent divergence.

FIG. 2.

Comparison of Y. pestis with other Yersinia species by plotting the ratios of 12:0 and 16:0 and 14:0 and 16:0 fatty acids. The ratios for the species other than Y. pestis were obtained from a previous study (26).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Catholic University of Louvain for financial support.

We thank G. Wauters for his scientific help and A. Zakharkevitch for translation of Russian articles.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abel K, De Schmertzing H, Peterson J I. Classification of microorganisms by analysis of chemical composition. I. Feasibility of utilizing gas chromatography. J Bacteriol. 1963;85:1039–1044. doi: 10.1128/jb.85.5.1039-1044.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alimova E K, Boikova E A. Fatty acid composition of the lipids from plague microbe. Biokhimiya. 1967;32:210–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alimova E K, Astvasatur'ian A T. Biosynthesis and oxidation of fatty acids of normal structure with an uneven number of carbon atoms, branched and cyclopropane. Usp Sovrem Biol. 1973;76:34–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asselineau J. Sur quelques applications de la chromatographie en phase gazeuse a l'étude d'acides gras bactériens. Ann Inst Pasteur. 1961;100:109–119. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bercovier H, Carlier J P. Chromatographie en phase gazeuse des acides gras produits par Yersinia enterocolitica dans divers milieux liquides. Ann Microbiol. 1979;130:37–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bercovier H, Mollaret H H. Yersinia. In: Krieg N R, Holt J G, editors. Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 1. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Wilkins Co.; 1984. pp. 498–506. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bousfield I J, Smith G L, Dando T R, Hobbs G. Numerical analysis of total fatty acid profiles in the identification of coryneform, nocardioform and some other bacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1983;129:375–94. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brenner D J, Steigerwalt A G, Falcao D P, Weaver R E, Fanning G R. Characterization of Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis by deoxyribonucleic acid hybridization and by chemical reactions. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1976;26:180–194. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Catteau M, Ringle P. Identification de Yersinia enterocolitica par Chromatographie des acides gras. Sci Aliments. 1987;95:2054–61. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cronan J E., Jr Phospholipid alterations during growth of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1968;95:2054–2061. doi: 10.1128/jb.95.6.2054-2061.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cronan J E, Jr, Vangelos P R. Metabolism and function of the membrane phospholipids of Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1972;265:25–60. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(72)90018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dagnelie P. Analyse statisque à plusieurs variables. Gembloux, Belgium: Les Presses Agronomiques de Gembloux; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dalla Venezia V M, Minka S, Bruneteau M, Mayer H, Michel G. Lipopolysaccharide from Yersinia pestis. Studies on lipid A of lipopolysaccharides I and II. Eur J Biochem. 1985;151:399–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1985.tb09115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Decallonne J, Delmée M, Wauthoz P, El Lioui M, Lambert R. A rapid procedure for the identification of lactic acid bacteria based on the gas chromatographic analysis of the cellular fatty acids. J Food Prot. 1991;54:217–224. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-54.3.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devignat R. Variétés de l'espèce Pasteurella pestis. Nouvelle hypothèse. Bull Org Mond Sante. 1951;4:247–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Esser A F, Souza K A. Correlation between death and membrane fluidity in Bacillus stearothermophilus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:4111–4115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.10.4111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frolov A F, Ruban N M, Vasyurenko Z P. Fatty acid composition of lipopolysaccharides of the strains of different species of Yersinia. J Hyg Epidemiol Microbiol Immunol. 1989;33:55–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guiyoule A, Grimont F, Iteman I, Grimont P A D, Lefevre M, Carniel E. Plague pandemics investigated by ribotyping of Yersinia pestis strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:634–641. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.3.634-641.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guiyoule A, Rasoamanana B, Buchrieser C, Michel P, Chanteau S, Carniel E. Recent emergence of new variants of Yersinia pestis in Madagascar. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2826–2833. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.11.2826-2833.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hartley J L, Adams G A, Tornabene T G. Chemical and physical properties of lipopolysaccharide of Yersinia pestis. J Bacteriol. 1974;118:848–854. doi: 10.1128/jb.118.3.848-854.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jantzen E, Lassen J. Characterization of Yersinia species by analysis of whole-cell fatty acids. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1980;30:421–428. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaneda T. Iso and anteiso fatty acids in bacteria: biosynthesis, function and taxonomic significance. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:288–302. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.2.288-302.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kates M. Bacterial lipids. Adv Lipid Res. 1964;2:17–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lambert M A, Moss C W. Comparison of the effects of acid and base hydrolysis on hydroxy and cyclopropane fatty acids in bacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;18:1370–1377. doi: 10.1128/jcm.18.6.1370-1377.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lechevalier M P. Lipids in bacterial taxonomy—a taxonomist's view. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1977;5:109–210. doi: 10.3109/10408417709102311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leclercq A, Wauters G, Decallonne J, El Lioui M, Vivegnis J. Usefulness of cellular fatty acid patterns for identification and pathogenicity of Yersinia species. Med Microbiol Lett. 1996;5:182–194. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lucier T S, Brubaker R R. Determination of genome size, macrorestriction pattern polymorphism, and nonpigmentation-specific deletion in Yersinia pestis by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2078–2086. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.7.2078-2086.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller L, Berger T. Bacteria identification by gas chromatography of whole cell fatty acids. Application note 228–41. Newark, Del: Hewlett Packard and MIDI Co.; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mollaret H H. Conservation expérimentale de la peste dans le sol. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Fil. 1963;6:1183–1186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moncla B J. Constitutive uptake and degradation of fatty acids by Yersinia pestis. J Bacteriol. 1983;153:340–344. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.1.340-344.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore R L, Brubaker R R. Hybridization of deoxyribonucleic sequences of Yersinia enterocolitica and other selected members of Enterobacteriaceae. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1975;25:336–339. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moss C W. The use of cellular fatty acids for identification of microorganisms. In: Fox A, et al., editors. Analytical microbiology methods, chromatography and mass spectrometry. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1990. pp. 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nozawa Y, Kasai R. Mechanism of thermal adaptation of membrane lipids in Tetrahymena pyriformis NT-1. Possible evidence for temperature-mediated induction of palmitoyl-CoA desaturase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978;529:54–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parilla Santos E, Soriano F, Aguilar L. Perfil cromatografico de los generas Yersinia enterocolitica y pseudotuberculosis. Rev Clin Esp. 1981;163:87–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pollitzer R. Plague. WHO Monograph Series 22. 1954. Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Samygin V M, Zykin L F, Stepanov V M, Stepin A A, Korsakova I I. The fatty acid composition of the cellular structures of Yersinia pestis. Zh Mik Epid Imm. 1993;55:16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Samygin V M, Zykin L F, Stepanov V M, Stepin A A, Korsako I I. A gas chromatographic analysis of the fatty acid composition of Yersinia pestis. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol. 1994;4:10–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sasser M. Identification of bacteria by gas chromatography of cellular fatty acids. Technical note 101. Newark, Del: Hewlett Packard and MIDI Co.; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sheremet O V, Boshnakov R B, Kharabadzhakhian G D, Milanova A N, Kartasheva L D, Tomov A T, Kosovskii V K. The fatty acid composition of Yersinia pestis grown on different nutrient media at 28 and 37 degrees C. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol. 1994;6:16–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skriwer L, Thompson G A., Jr Temperature-induced changes in fatty acid unsaturation of Tetrahymena membranes do not require induced fatty acid desaturase synthesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;572:376–381. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(79)90054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tornabene T G. Lipid composition of selected strains of Yersinia pestis and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1973;306:173–185. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(73)90223-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Toubiana R, Asselineau J. Identification de l'acide cis-méthylène-9.10 hexadécanoïque comme constituant de certains lipides bactériens. C R Acad Sci. 1962;254:369–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vasyurenko Z P, Znamenskii V A. Fatty acid makeup of bacteria in the genus Yersinia. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol. 1980;42:462–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vulliet P, Markey S P, Tornabene T G. Identification of methoxyester artifacts produced by methanolic-HCl solvolysis of the cyclopropane fatty acids of the genus Yersinia. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1974;348:299–301. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(74)90241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wauthoz P. Caractérisation et identification de la microflore bactérienne des aliments par analyse chromatographique des acides gras cellulaires. Ph.D. thesis. Louvain-La-Neuve, Belgium: Catholic University of Louvain; 1992. [Google Scholar]