Abstract

There has been no unequivocal demonstration that the activator binding targets identified in vitro play a key role in transcriptional activation in vivo. To examine whether activator-Mediator interactions are required for gene transcription under physiological conditions, we performed functional analyses with Mediator components that interact specifically with natural yeast activators. Different activators interact with Mediator via distinct binding targets. Deletion of a distinct activator binding region of Mediator completely compromised gene activation in vivo by some, but not all, transcriptional activators. These demonstrate that the activator-specific targets in Mediator are essential for transcriptional activation in living cells, but their requirement was affected by the nature of the activator-DNA interaction and the existence of a postrecruitment activation process.

A set of proteins required for accurate initiation of RNA polymerase II (Pol II) transcription have been isolated, and their mode of action has been studied extensively (30). In addition to these so-called basal transcription factors, another group of proteins (collectively termed coactivators) have been shown to stimulate Pol II transcription in response to gene-specific enhancer DNA-bound activator proteins. Certain coactivators, such as histone acetyltransferases and ATP-dependent nucleosome-remodeling factors, function in the context of chromatin by covalently modifying or repositioning nucleosomes (3, 43). Others transduce activation signals from enhancer-bound activators to the basal transcription machinery. TATA-binding protein-associated factors (TAFs) and Mediator complexes are two representative members of this class of coactivators (2, 10).

TAFs were identified initially in Drosophila and human cells as integral components of TFIID and shown to possess coactivator activity in vitro (5, 42). However, depletion of various TFIID-specific TAFs does not have a significant effect on transcriptional activation of most genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (15, 25, 45). More importantly, TAF-independent transcriptional activation has been reported in several in vitro systems (19, 21, 29, 46), suggesting the existence of another activator target that plays a more dominant role in transcriptional activation.

Mediator, a multiprotein complex containing Srb/Med and several other transcriptional regulatory proteins, is tightly associated with the Pol II holoenzyme (designated hpol II) in the yeast S. cerevisiae (19, 21) and plays a pivotal role in transcriptional regulation. Even though the Mediator complex as a whole is required in general for Pol II transcription, some of its subunits function in an activator-specific manner to modulate the expression of a distinct subset of genes (13, 15, 23). In addition, genetic evidence suggests that a subset of the Mediator proteins are involved in transcriptional repression (4, 8, 17, 35). Differential dissociation of the Mediator components by high-urea treatment (22) and compositional analysis of mutant hpol II complexes (23, 24, 26) revealed that Mediator subunits with similar genetic properties form distinct modular subassemblies.

Because purified hpol II in conjunction with basal transcription factors can support activated transcription in a well-defined yeast transcription system (19, 21), it was conceived that gene-specific activators communicate either directly or indirectly with Mediator to recruit Pol II to the promoter. This idea was substantiated by findings that hpol II interacts with the functional activation domain of VP16 and Gcn4 (6, 14, 23). Furthermore, so-called artificial recruitment experiments demonstrated that transcriptional activation can occur independently of an activation domain when hpol II is recruited to promoters either by physically tethering a Mediator component to an enhancer-bound protein or by introducing into a Mediator protein a gain-of-function mutation that endows the protein with synthetic activator-binding capability (1, 7).

Using the model activator VP16, we demonstrated previously that a distinct module of Mediator is required for activator binding (23). However, it remains to be determined whether natural yeast activators, including Gal4 and Gcn4, also utilize the same Mediator module for their interaction with hpol II. Moreover, there has been no unequivocal demonstration to date that the physical interaction between transcriptional coactivators and activator proteins identified in vitro does in fact play a critical role in activated transcription in living cells.

In order to decipher more precisely the in vivo function of the activator-binding target(s) in the Mediator complex, we have determined systematically the Mediator subunits that serve as direct binding targets for VP16, Gal4, and Gcn4 and localized the binding domain in each of the target subunits. Next, we generated mutant Mediator proteins from which the activator-binding region was removed and tested their ability to support activated transcription under physiological conditions. Our results show that Mediator has distinct interacting surfaces for each activator protein and these surfaces are required for gene activation in vivo. In addition, we find that hpol II recruitment to promoters in yeast cells requires the interaction of gene-specific transcriptional activators with their target-binding domains in the Mediator complex. However, with some activators this interaction does not necessarily result in activated transcription. Hence, each transcriptional activator may utilize diverse but distinct activation mechanisms, including chromatin remodeling and hpol II recruitment, to achieve higher transcriptional efficiency.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains.

The hrs1 null strain JMP9 (MATα ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 hrs1::LEU2) was constructed by crossing SSAB-2CF (37) to YPH499 (38). Diploids were sporulated, and a segregant containing the correct set of markers was selected.

Plasmid constructs.

In order to construct pGEX-mini-Gal4 and pET-mini-Gal4, the XhoI-BamHI fragment from pRJR113 (blunted for pGEX-mini-Gal4) that encodes a part of the Gal4 activation domain (32) was inserted into XhoI- and NotI (blunted)-digested pGEX-4T2 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and XhoI- and BamHI-digested pEh-Gal4VP16, respectively. Glutathione-S-transferase (GST) fusion plasmid vectors that encode a fragment of Gal11 and Hrs1 were constructed by inserting a PCR-amplified or restriction enzyme-digested protein-coding DNA fragment into the appropriate pGEX vectors. The parental plasmids that contain the GAL11 gene and some of the GST-Gal11 fusion plasmids were provided by Hiroshi Sakurai and have been described previously (36).

Low-copy-number plasmids that encode GAL11 and its internal deletion mutants were constructed by excising the entire Gal11 protein-coding sequences (by KpnI and PstI digestion) from high-copy-number plasmids containing the GAL11 derivatives (36) and cloning them into the TRP1-marked plasmid pRS314 (38). A plasmid encoding the gal11Δ(176-262) mutation was provided by Masafumi Nishizawa and has been described previously (28).

The low-copy-number plasmids encoding HRS1 were prepared in a sequential manner. The KpnI-NotI fragment from pRS316-HRS1 (37) that encodes the promoter region and an amino-terminal part of HRS1 was inserted into KpnI- and NotI-digested pRS314 to construct pRS314-HRS1N. The NotI fragment from pGEX-Hrs1(83-432), which carries the rest of the Hrs1 coding sequence, was subsequently cloned at the NotI site of pRS314-HRS1N. pRS314-hrs1Δ(180-343) was constructed by cloning a PCR-amplified sequence encoding amino acids 344 to 432 of Hrs1 into the NotI site of pRS314-HRS1N. In order to construct pRS314-hrs1Δ(2-82), the XhoI (blunted)-EcoRI fragment from pGEX-Hrs1(83-432), which encodes the Hrs1 coding sequence lacking the amino-terminal 82 amino acids, was inserted into SmaI- and EcoRI-digested pRS314 to construct pRS314-HRS1C. PCR-amplified sequence encoding the HRS1 promoter was then digested with KpnI and SmaI and inserted into KpnI- and EcoRI (blunted)-digested pRS314-HRS1C.

The lacZ reporter plasmid 2XGCN4-CYC1-lacZ was constructed by inserting the PvuII fragment from pSPGCN4CG (9), which contained two consecutive Gcn4 binding sites, into SmaI- and XhoI (blunted)-digested pLGSD5 (12). pRS313-Gal4DBD-Gcn4 was constructed by inserting the EcoRI fragment from pLY235 (47) into the EcoRI site of pRS313-Gal4VP16. pRS313-Gal4VP16 was prepared by inserting the ScaI-XbaI fragment with the Gal4VP16 expression cassette from pMA540 (34) into the EcoRV and XbaI sites of the HIS3-based low-copy-number plasmid pRS313.

Analysis of activator-Mediator interactions.

GST pulldown assays and far-Western blot analyses were carried out as described previously (23). The GST and hexahistidine fusion proteins used in the in vitro binding assays were expressed in and purified from Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) using glutathione-Sepharose (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech) and Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (Qiagen), respectively. Hemagglutinin (HA) fusion proteins were purified from Sf9 insect cells infected with recombinant FASTBAC baculovirus (Gibco-BRL) with anti-HA monoclonal antibody (BAbCo) and HA peptide (Roche) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The wild-type and Δhrs1 hpol II used in the experiments shown in Fig. 1A were purified from yeast cells using Bio-Rex 70, DEAE-Sephacel, Bio-gel HTP, and Mono Q chromatography as described (19). The hpol II used in compositional analyses (Fig. 3B, 4D, and 6C) was immunoprecipitated from Bio-Rex 70 fractions with anti-Rgr1 antibody.

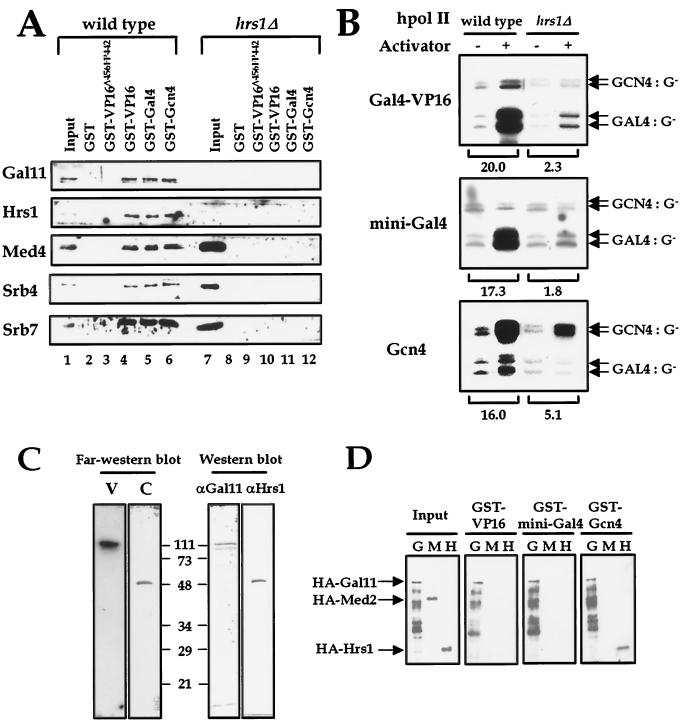

FIG. 1.

Gal11 module of Mediator is required for activator binding and transcriptional activation. (A) GST pulldown assay of wild-type hpol II (lanes 1 to 6) and hrs1Δ hpol II (lanes 7 to 12). Purified hpol II in the Mono-Q fraction (19) was incubated with GST beads containing the GST-activator fusion proteins indicated at the top of each lane. As controls, GST alone (lanes 2 and 8) and GST fused to an activation-defective version of VP16 (VP16Δ456FP442; lanes 3 and 9) were used. Bead-bound proteins, along with the proteins used in the binding reactions (input; lanes 1 and 7), were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and subsequent immunoblotting with the Mediator antibodies indicated at the left of the panel. (B) The transcriptional activity of wild-type and hrs1 null (hrs1Δ) hpol II were analyzed in an in vitro transcription system reconstituted with purified transcription factors. The presence (+) or absence (−) of activator proteins is indicated at the top of the panel. The transcripts from the G-less templates containing either the Gal4 (Gal4:G−) or Gcn4 (Gcn4:G−) DNA-binding sites are indicated by arrows at the right of the panel. The fold activation of hpol II by each activator is shown at the bottom of the panel. (C) Far-Western blot analysis of activator-binding targets. Affinity-purified hpol II blotted on nitrocellulose membrane after resolution by SDS-PAGE was probed with radiolabeled VP16 (V) or Gcn4 (C) protein (left panel). The labeled protein bands were visualized by reprobing the same blot with anti-Gal11 and anti-Hrs1 antibodies (right panel). The apparent molecular sizes (in kilodaltons) are shown in the middle. (D) GST pulldown assay of Gal11 module proteins. Purified HA-Gal11 (G), HA-Med2 (M), and HA-Hrs1 (H) proteins were incubated with the bead-bound GST-activator fusion proteins indicated at the top of the panel. After washing away the unbound proteins, the proteins that remained bound to the beads were visualized by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody. The protein bands are indicated with arrows at the left of the panel. The largest band in the G lanes is the full-length HA-Gal11 fusion protein, and the smaller bands are degradation products of the parent protein.

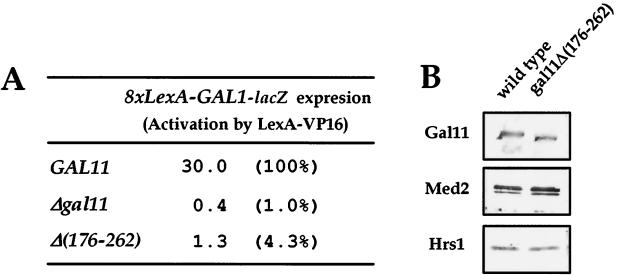

FIG. 3.

Requirement for the VP16-interacting region of Gal11 for transcriptional activation in vivo. (A) In vivo analysis of gal11 mutants for VP16 activation. The GAL11 derivatives introduced into the gal11 null strain are labeled [wild type, null, and Δ(176-262)]. Transcriptional activation of the lacZ reporter gene containing LexA-binding sites by LexA-VP16 in each strain is shown at the right of each allele. In this and the other figures in this paper, reporter gene expression level is given in units of β-galactosidase activity. The percent transcriptional activation in mutants compared to that in the wild type is shown in parentheses. (B) Composition of hpol II purified from the gal11Δ(176-262) mutant. Shown are the immunoblot analyses of hpol II immunopurified from wild-type and gal11Δ(176-262) mutant cells with the antibodies indicated at the left.

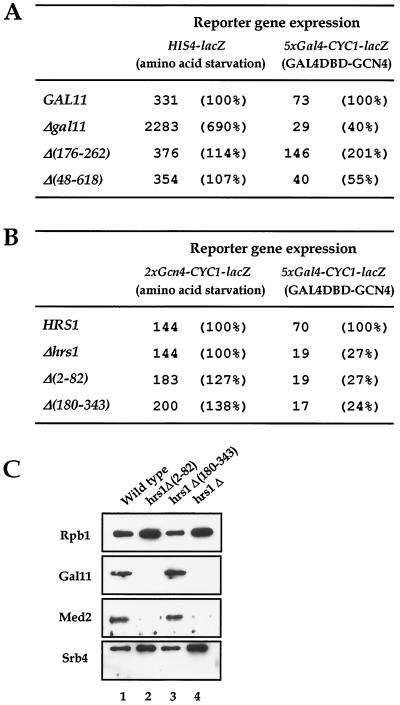

FIG. 4.

Requirement for the Gal4-interacting regions of Gal11 for transcriptional activation in vivo. (A) Growth of wild-type and gal11 mutant yeast strains on galactose medium. Wild-type (GAL11), gal11 null (gal11Δ), and two internal deletion [Δ(48-618) and Δ(176-262)] mutant yeast strains grown on YP-galactose at 30°C for 72 h are shown. (B) Transcriptional activity of gal11 mutants under Gal4 induction conditions. The GAL11 derivatives introduced into the gal11 null strain are labeled, and the transcriptional activation of the lacZ reporter gene containing Gal4 binding sites in each strain is shown as in Fig. 3A. (C) Comparison of the transcriptional activation abilities and activator-binding efficiencies of wild-type GAL11 (1 to 1081) and a series of internal deletion mutants [Δ(176-262), Δ(48-326), and Δ(48-618)]. (D) Composition of wild-type hpol II and hpol II purified from the gal11Δ(48-618) mutant yeast strains. hpol II was immunopurified from wild-type and gal11Δ(48-618) mutant yeast strains, and their compositions were compared by immunoblot analysis with the antibodies indicated at the left. The internal deletion mutant of gal11 produced a smaller Gal11 protein derivative than did wild-type GAL11. Sizes are shown in kilodaltons.

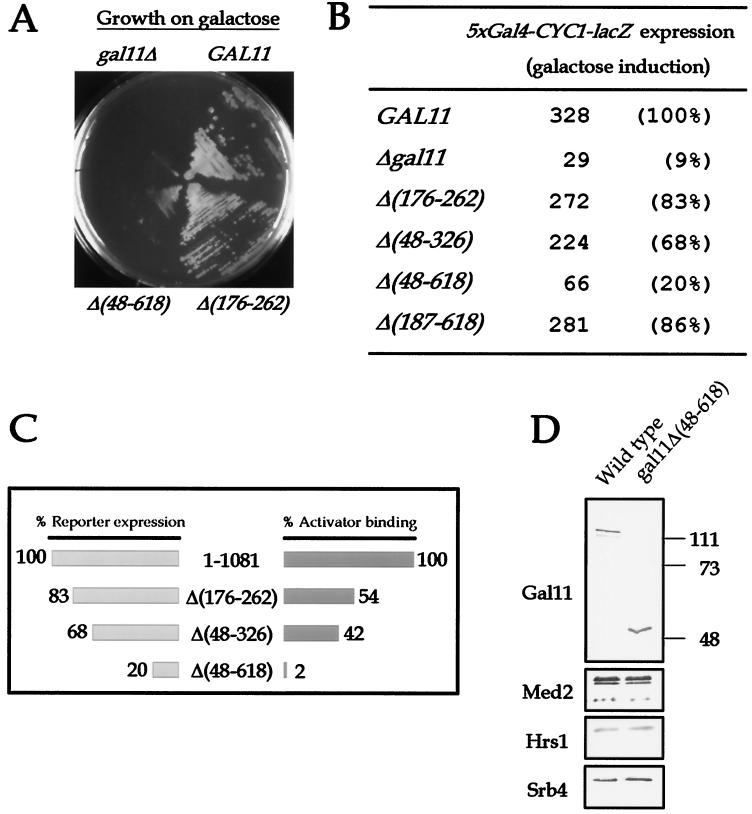

FIG. 6.

Requirement for Gcn4-interacting regions of Mediator for transcriptional activation in vivo. (A) In vivo analysis of the gal11 mutants for Gcn4 activation. Transcriptional activation of the lacZ reporter gene controlled by a natural HIS4 promoter or a synthetic promoter containing Gal4 binding sites under the respective activation conditions is shown; amino acid starvation or expression of exogenous Gcn4 protein fused to a Gal4 DNA-binding domain (Gal4DBD-Gcn4) is used for transcriptional activation of each reporter gene. The percent transcriptional activation in mutants compared to the wild type is shown in parentheses. (B) In vivo analysis of the effects of hrs1 mutations on transcriptional activation by Gcn4. The HRS1 derivatives and their transcriptional activities are shown as described for panel A except that a synthetic promoter containing Gcn4-binding sites was used instead of the natural HIS4 promoter. (C) Composition of hpol II purified from hrs1 deletion mutants. Immunoblot analysis of hpol II purified from wild-type, hrs1 null mutant (hrs1Δ), hrs1Δ(2-82) (deletion of H1-A), and hrs1Δ(180-343) (deletion of H1-B) strains was carried out with antibodies against the hpol II subunits indicated at the left.

Transcriptional analysis.

Reconstituted in vitro transcription reactions were performed as described (19). For the analysis of reporter gene expression in yeast cells, episomal reporter plasmids were introduced into yeast cells by transformation, and the transformed cells were grown in selective synthetic complete medium to the mid-log phase. Galactose induction and amino acid starvation were conducted as described (13). β-Galactosidase activity in cells was measured in triplicate by the permeabilized-cell method (12).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation.

Yeast cells were subjected to formaldehyde cross-linking, and the soluble chromatin was fragmented by sonication and immunoprecipitated with anti-Rgr1 antibody as described previously (39). PCR primers were used to amplify the following regions (coordinates relative to the ATG at +1): the −160/−13 region of GAL1; the −357/−79 region of HIS4; and the −298/−38 region of the actin gene.

RESULTS

Gal11 module of yeast hpol II serves as an activator-specific binding target.

We showed previously that the VP16 activation domain (amino acids 412 to 490) interacts directly with yeast hpol II in an in vitro assay (23). One or more of the Mediator subunits in the Gal11 module of hpol II (Gal11, Hrs1, and Med2) function in this interaction, as gal11 and hrs1 null versions of hpol II (which lack all three constituents of the Gal11 module) are severely defective for VP16 activator binding. In order to test whether the natural yeast activator proteins Gcn4 and Gal4 also interact with the Gal11 module of Mediator, we measured the affinity of wild-type and mutant (hrs1Δ) hpol II binding to each activator protein with a GST pulldown assay. For convenience, we used a minimized Gal4 protein that contained the Gal4 DNA-binding domain (Gal4DBD; amino acids 1 to 93) fused to the carboxyl-terminal activation domain (amino acids 768 to 881) (designated mini-Gal4 in this study). Wild-type hpol II bound specifically to GST-activator fusion proteins, whereas hrs1Δ hpol II, which lacks the Gal11 module, did not bind to any of the activator proteins tested (Fig. 1A). Therefore, Gal4, Gcn4, and VP16 all contact hpol II via the Gal11 module proteins.

To evaluate the requirement of the activator-Gal11 module interaction for transcriptional activation, we measured the transcriptional activity of the hrs1Δ hpol II in a reconstituted transcription system. The lack of the Gal11 module in hrs1Δ hpol II did not affect basal transcription activity (Fig. 1B). However, transcriptional activation of hrs1Δ hpol II by Gal4-VP16, mini-Gal4, and Gcn4 was either completely defective or partially compromised (Fig. 1B). These results suggest that the direct interactions between the activator proteins and the Gal11 module play an important role in transcriptional activation in vitro. However, it was still unclear which of the components of the Gal11 module is a direct binding target for the activator proteins. Therefore, we aimed to identify the Mediator subunit(s) that interacts directly with each activator protein.

When a membrane blotted with purified wild-type hpol II was probed with radiolabeled VP16 protein using a far-Western analysis, only the Gal11 polypeptide gave a strong binding signal (Fig. 1C) (23). However, when the same blot was probed with radiolabeled Gcn4, the Hrs1 polypeptide gave a strong signal (Fig. 1C). This result hinted at the presence of activator-specific binding targets within the Mediator. To confirm this result, we used a GST pulldown assay to examine the direct interactions between each of the purified Gal11 module proteins (HA-tagged proteins HA-Gal11, HA-Hrs1 and HA-Med2) and GST-activator fusion proteins GST-VP16, GST-mini-Gal4, and GST-Gcn4. All of the activator proteins tested bound tightly to Gal11, whereas none bound to Med2. In addition, Gcn4 interacted with both Hrs1 and Gal11 (Fig. 1D). The discrepancy between the results of the far-Western and GST pulldown assays may have resulted from the differential sensitivities of the two assays in detecting protein binding affinity. Nevertheless, Gal11 appears to be a common activator binding target, whereas Hrs1 acts as a Gcn4-specific target. Med2, on the other hand, may function as an auxiliary factor rather than as a direct activator-binding target, or could serve as a binding site for a different type of activator protein.

VP16-interacting domain of Gal11 Is essential for transcriptional activation in vivo.

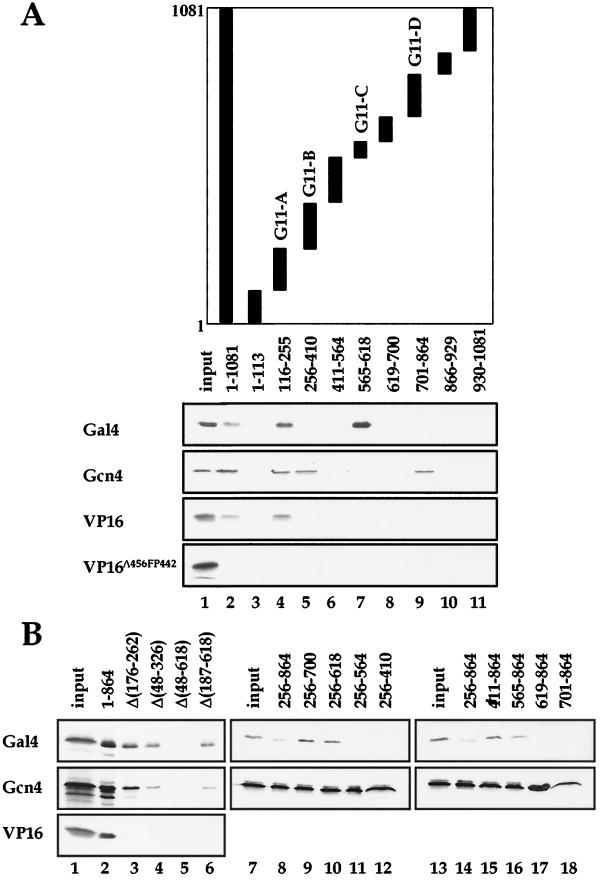

Although the in vitro binding analysis identified Gal11 as a common binding target of the activator proteins tested, the role of this interacting domain under physiological conditions remains to be determined. In order to address this question, we sought to examine the function of a version of yeast hpol II that lacked only the specific activator-binding region of the Mediator. To this end, we first mapped more precisely the VP16-binding region within Gal11. We prepared a series of GST fusion proteins, each containing a fragment that spans a different region of Gal11 (Fig. 2). The various GST-Gal11 fusion proteins were incubated individually with 35S-labeled VP16, and their physical interactions were monitored by GST pulldown assays. This analysis identified residues 116 to 255 (G11-A in Fig. 2A) of Gal11 as the sole VP16-binding region (Fig. 2, lane 4). The interaction required a functional VP16 activation domain, as no such physical interaction was observed with the activation-defective VP16 mutant protein Δ456FP442 (Fig. 2A). A Gal11 protein derivative [1-864Δ(176-262)] from which only a portion of G11-A was deleted did not interact with VP16 (Fig. 2B, lane 3), although it was able to interact with Gal4 and Gcn4. These findings suggest that G11-A is both necessary and sufficient for VP16 binding.

FIG. 2.

GST-Gal11 pulldown assay with activator proteins Gal4, Gcn4, and VP16. (A) Radiolabeled activators indicated at the left-hand side of the panel were incubated with GST beads containing the Gal11 fragments indicated at the top of each lane. Fragments of Gal11 polypeptide fused to GST are represented as solid bars, and the Gal11 amino acid residues contained in each fragment are indicated. The proteins bound to the beads were visualized by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. The regions identified to interact with activator proteins are labeled G11-A to G11-D. (B) GST pulldown assays with GST beads fused to a series of Gal11 derivatives that contained various internal deletions or with GST beads fused to the Gal11 fragments indicated at the top of each lane as in panel A. The parts of the amino acid residues deleted from the Gal11(1-864) fragment (lanes 3 to 6) are indicated by numbers in parentheses following the Δ.

In order to examine the in vivo requirement of G11-A for transcriptional activation by VP16, we constructed the gal11Δ(176-262) mutant strain and tested its ability to support reporter gene activation by LexA-VP16 in vivo. The GAL11 wild-type strain supported activation of reporter gene expression by LexA-VP16, but deletion of G11-A completely abolished this expression (Fig. 3A). To confirm that the transcriptional defect results solely from the deletion of G11-A rather than from a loss of other Mediator subunits, the gal11Δ(176-262) mutant hpol II was purified, and its composition was analyzed by immunoblot. The protein composition of gal11Δ(176-262) mutant hpol II was indistinguishable from that of the wild type, and both Med2 and Hrs1 were tightly associated with the hpol II (Fig. 3B). Besides, all of the deletion mutants used in this study retained the other activities of Mediator, such as stimulation of basal transcription and phosphorylation of the largest subunit of Pol II (data not shown). These results suggest that the transcriptional defects of the Gal11 module mutants did not result from a conformational distortion of the Mediator complex by the deletions. Therefore, G11-A plays a specific role in transcriptional activation via direct interaction with VP16 in yeast cells.

Gal4 activator requires an additional region of Gal11 for its binding and transcriptional activation in vivo.

The observed requirement for a specific interaction between VP16 and Gal11 for transcriptional activation in S. cerevisiae raises the possibility that G11-A may serve as a general binding site for natural yeast activators such as Gal4. In order to test this idea, 35S-labeled mini-Gal4 protein was incubated with the series of GST-Gal11 fusion proteins that were used in the above experiments. Mini-Gal4 bound G11-A as did VP16, but in addition it interacted strongly with G11-C (amino acids 565 to 618; Fig. 2A, lanes 4 and 7). The presence of two binding sites for mini-Gal4 in Gal11 was confirmed with GST pulldown assays using in-frame, internal deletion mutant versions of Gal11. A Gal11 protein derivative that harbored a deletion of a portion of G11-A [1-866Δ(176-262)] completely lost its affinity for VP16, but was still able to bind mini-Gal4 protein (Fig. 2B, lane 3). Only when both of the binding regions for mini-Gal4 (G11-A and G11-C) were deleted [1-866Δ(48-618)] was the protein unable to bind mini-Gal4 (lane 5). These binding specificities were also confirmed by using a series of deletion mutants in which terminal amino acid residues in Gal11 from 256 to 864 are removed to various extents (lanes 7 to 18).

In order to assess the physiological requirement for these Gal4-binding sites for transcriptional activation, we examined the growth of the gal11 internal-deletion mutant strains on galactose medium. Although G11-A was essential for VP16 activation in vivo, the gal11Δ(176-262) mutant grew well on galactose medium (Fig. 4A). However, when both of the Gal4-interacting regions (G11-A and G11-C) were deleted, the gal11Δ(48-618) mutant, like the gal11 null mutant, was not able to grow on galactose medium (Fig. 4A). In order to confirm that the growth defect of the mutants resulted from a Gal11 transcriptional defect, we examined the effect of the gal11 mutations on the expression in yeast cells of a lacZ reporter gene bearing the gal4 enhancer. Consistent with the above results, the gal11Δ(176-262) strain was capable of responding to galactose induction efficiently (Fig. 4B). However, in the gal11Δ(48-618) strain, Gal4 activation was reduced to 20% of that in the wild-type strain under the same conditions (Fig. 4B). In particular, the transcriptional activity of the GAL11 internal deletion mutants was in proportion with their relative activator binding strength (Fig. 4C), which demonstrates the direct relationship between the two properties of Mediator. Immunoblot analysis of gal11Δ(48-618) hpol II, which showed the association of all the Mediator components (Fig. 4D and data not shown), confirmed that the transcriptional defect was caused by deletion of Gal4-binding sites within Gal11 rather than from the dissociation of other Mediator subunits. Therefore, the multiple activator-binding sites of Gal11 appear to have an essential function in the mediation of the Gal4 activation signal in vivo.

Different transcriptional activator proteins utilize distinct subunits of Mediator as their binding targets.

The in vitro binding assays shown in Fig. 1 demonstrated that different activators have different requirements for interaction with Mediator, and at least for VP16 and Gal4, these interactions are essential for transcriptional activation in vivo. Even though the effect was not as complete as with VP16 and Gal4, transcriptional activation by Gcn4 was also reduced more than threefold in an in vitro transcription system when all of the Gcn4-interacting Mediator subunits were absent from hpol II (Fig. 1B). Therefore, to examine further the generality of activator-Mediator interactions in transcriptional regulation in yeast cells, we deciphered the protein domains required for Gcn4 binding to Mediator and evaluated their physiological function.

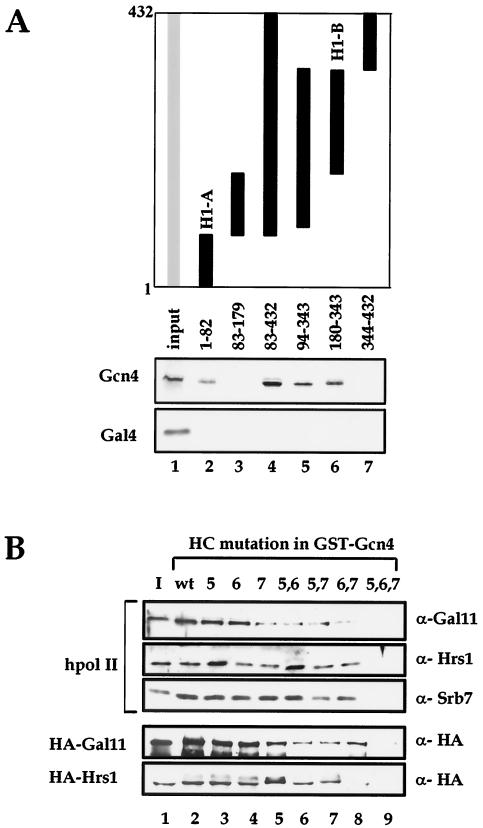

Because Gcn4 binds to both Gal11 and Hrs1, we narrowed down the binding regions in each protein using the GST pulldown assay. Gcn4 bound to G11-A, as did VP16 and mini-Gal4 (Fig. 2A, lane 4). However, two additional regions of Gal11 (G11-B and G11-D), which were distinct from mini-Gal4-binding region G11-C, interacted strongly with Gcn4 (lanes 5 and 9). We next examined the Gcn4-binding regions within Hrs1 by creating a series of GST fusion proteins that contained various fragments of Hrs1 and tested them in GST pulldown experiments (Fig. 5A). The GST pulldown assays revealed that Gcn4 bound to an N-terminal fragment (amino acids 1 to 82; H1-A) and a central region (amino acids 146 to 315; H1-B) of Hrs1 (lanes 2, 4, 5, and 6). However, the mini-Gal4 protein, which has a similar acidic activation domain, did not interact with any of the GST-Hrs1 fusion proteins (Fig. 5A). These results demonstrate that Gcn4, Gal4, and VP16 each utilize distinct regions of Mediator as their hpol II binding targets.

FIG. 5.

Mediator-binding specificity of Gcn4. (A) Mapping of Gcn4-binding regions within Hrs1. Radiolabeled Gcn4 or Gal4 proteins were incubated with GST beads containing the GST-Hrs1 fragments indicated at the top of each lane. Fragments of Hrs1 polypeptide fused to GST are represented as solid bars, and the Hrs1 amino acid residues contained in each fragment are indicated. The proteins bound to the beads were visualized by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. The regions identified to interact with the transcriptional activator proteins Gcn4 and Gal4 are labeled H1-A and H1-B. (B) Correlation between Mediator binding affinity and transcriptional activation potency of Gcn4 derivatives. Purified hpol II or recombinant HA-Gal11 or HA-Hrs1 proteins were analyzed by GST pulldown assays with GST beads fused to a series of Gcn4 mutant protein derivatives that contained single (lanes 3 to 5), double (lanes 6 to 8), or triple (lane 9) mutations in the hydrophobic clusters (HC) (16). Immunoblot analysis of the bound proteins with the antibodies indicated at the right of the panel is shown.

In order to assess the specificity of the Gcn4-Hrs1 interactions, we made use of a series of Gcn4 mutants that manifest differential transcriptional activation potency. The Gcn4 activation domain contains multiple clusters of hydrophobic residues that make redundant contributions to transcriptional activation (16). When amino acid substitutions are introduced into these clusters, their effects on transcriptional activation by Gcn4 are cumulative, with a reduction of activation potency in vivo that is proportional to the number of mutated clusters. Therefore, we used GST pulldown assays to examine whether the additive effects of these mutations on transcriptional activation correlated with their effects on the binding of Gcn4 to Gal11 and Hrs1. Purified hpol II was incubated with GST-Gcn4 beads that retained either wild-type GST-Gcn4 or mutant GST-Gcn4 proteins with single, double, or triple hydrophobic cluster substitutions. The single-cluster mutations had little effect on hpol II binding (Fig. B, lanes 3 to 5), while double-cluster substitutions resulted in a moderate reduction in hpol II binding (lanes 6 to 8). With the triple-cluster substitutions, virtually no bound hpol II was detected (lane 9). Therefore, the additive effects of Gcn4 mutations on transcriptional activation correlated with their effects on binding to Mediator. A similar correlation was observed when the same experiments were repeated with recombinant Gal11 or Hrs1 polypeptides (Fig. 5B). We thus conclude that the interaction between Gcn4 and hpol II depends on a functional Gcn4 activation domain and the Gal11 module in which Gal11 and Hrs1 make independent contributions to Gcn4 binding.

Recruitment of hpol II through direct interaction with Gcn4 does not limit the level of gene activation in vivo.

In order to test the effect of the Gcn4-interacting domains within Gal11 and Hrs1 on transcriptional activation under physiological conditions, various gal11 and hrs1 mutants were checked for growth on minimal medium containing 30 mM 3-aminotriazole (this growth condition is required for activation of the HIS3 gene by Gcn4). Contrary to our previous observations, where the activator-interacting domains of Mediator were strictly required for transcriptional activation by VP16 and Gal4 in vivo, the physical interactions of Gcn4 with Gal11 and Hrs1 did not show any notable physiological relevance. In fact, the gal11 and hrs1 null mutants also grew as well as the wild-type yeast strain in the presence of 3-aminotriazole (data not shown). Therefore, the Gal11 module of the Mediator is dispensable for growth under conditions that require induction of Gcn4-regulated genes, or at least the HIS3 gene. Likewise, the expression of Gcn4-responsive reporter genes in the gal11 and hrs1 mutant strains was equivalent to that of the wild-type yeast strain. The transcriptional activation of HIS4-lacZ (which contains the natural HIS4 promoter; assayed for gal11 mutants) or 2XGCN4-CYC1-lacZ (which contains a synthetic promoter with two Gcn4-binding sites; assayed for hrs1 mutants) under amino acid starvation conditions was not reduced in any of the mutants tested compared to a wild-type yeast strain (Fig. 6A and B).

The lack of an effect of mutations in the activator-binding target for Gcn4 transcriptional activation appears to be related to the distinct mode of DNA binding of Gcn4 rather than to the uniqueness of the Gcn4 activation domain. When the Gcn4 protein was fused to the Gal4 DBD (Gal4DBD-Gcn4) and assayed for its ability to activate the reporter gene 5xGal4-CYC1-lacZ (synthetic promoter containing five Gal4 binding sites), transcriptional activation was rendered dependent on Gcn4-Mediator interaction (Fig. 6A and B). The deletion of Gcn4-interacting domains in Gal11 or Hrs1 caused a two- to fourfold reduction in reporter gene expression. Although the transcriptional defect observed with hrs1Δ(2-82) hpol II may be attributed to the concurrent loss of the Gal11 module proteins (Fig. 6C, lane 2), the reduced level of activation in response to Gal4DBD-Gcn4 by the hrs1Δ(180-343) hpol II is not related to the loss of other Gal11 module components (lane 3). These results indicate that H1-B indeed acts as a functional Gcn4-binding target in vivo under certain conditions (see Discussion).

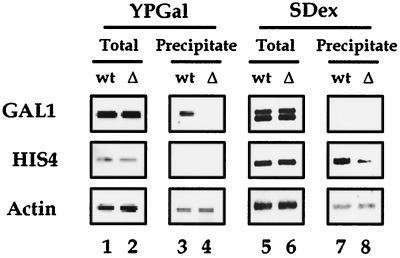

Gal11 module is required for hpol II recruitment to promoters in vivo.

In order to examine whether the interaction between activators and the Gal11 module is indeed required for hpol II recruitment to promoters in vivo, we performed a chromatin immunoprecipitation using a Mediator (Rgr1)-specific antibody. Occupancy of hpol II at the HIS4, GAL1, and Actin promoters was analyzed in wild-type and gal11 null mutant strains under the specified growth conditions (Fig. 7). In wild-type cells, hpol II was recruited to the GAL1 and HIS4 promoters only under Gal4-inducing (growth on galactose) or Gcn4-inducing (amino acid starvation) conditions, respectively (lanes 3 and 7). In gal11 null cells, hpol II occupancy at the GAL1 promoter was reduced below a detectable level under galactose induction conditions (lane 4). However, we observed only a threefold reduction in hpol II occupancy at the HIS4 promoter under amino acid starvation conditions (lane 8). This shows that the Gcn4-Mediator interaction contributes to some extent to hpol II recruitment in vivo, but its requirement is not as absolute as it is in the case of Gal4-Mediator activation. In conclusion, hpol II recruitment to the promoter is the main transcriptional activation mechanism for the Gal4 activator, whereas it is only partially required for transcriptional activation by Gcn4.

FIG. 7.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis of the Gal11 module-deficient mutant. The occupancy of wild-type (wt) and Gal11 module-deficient (Δ) hpol II at active or inactive promoters is shown by assay with antibodies to Rgr1. Growth of cells on rich medium containing galactose (YPGal) induces GAL1 transcription but represses the HIS4 promoter. On the other hand, growth of yeast cells on synthetic medium containing dextrose and limited amino acids (SDex) activates HIS4 transcription but represses the GAL1 promoter. As a control, hpol II occupancy at the constitutively active actin promoter was analyzed in parallel. PCR amplification of the promoter regions before (Total; lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7) and after (Precipitate; lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8) the immunoprecipitation is shown.

DISCUSSION

In eukaryotes, several basal transcription factors and coactivators have been reported to interact with gene-specific transcriptional activator proteins in vitro. However, efforts to delineate the molecular mechanisms of transcriptional activation from the observed activator-target interactions have been hampered primarily by the lack of experimental analyses that evaluate the physiological relevance of the in vitro interaction. Here we report on complementary biochemical and genetic analyses that show the essential requirement for the yeast Mediator Gal11 module for activator-specific transcriptional activation in vivo.

Activator-specific binding targets in the Mediator.

We first determined which Mediator subunit(s) interacts directly with VP16 and the natural yeast activators Gal4 and Gcn4. All three activators interact with hpol II in a manner that absolutely requires the Gal11 module. Srb4 was reported previously to bind to Gal4 (20). However, hrs1Δ hpol II, which contains stoichiometric amounts of Srb4 (Fig. 6C), did not display the ability to interact with Gal4 (Fig. 1A). Therefore, Srb4 is likely to contribute to Gal4-Mediator interaction to a lesser extent than the Gal11 module proteins. Nonetheless, it may serve as an alternative Gal4-binding target, especially when it is taken into account that, in the gal11Δ(48-618) strain, Gal4 activation still occurs, even at a much reduced level (Fig. 4B).

Analysis of the interaction between each activator with individual constituents of the Gal11 module revealed that all three activators bind to Gal11, and in the case of Gcn4, additional contacts are made with Hrs1. These interactions involve activator-specific regions of the Gal11 and Hrs1 polypeptides. Our results show that deletion of the VP16- and Gal4-binding regions within Gal11 blocks transcriptional activation by VP16 and Gal4 in vivo, illustrating the prime importance of Gal11 in VP16 and Gal4 transcriptional activation in vivo. Others have reported that Gal4 activation is also impaired in hrs1 and med2 yeast strains (26, 31), but such defects might result from the concurrent loss of the Gal11 protein from the mutant hpol II complex (23, 26).

A mutation in Gal11 protein that potentiates the activities of certain weak Gal4 derivatives (designated Gal11P) maps to a distinct location (position 342) from the G11-A and G11-C regions that interact with the Gal4 activation domain (1). As Gal11P was shown to gain the ability to interact with a portion of the Gal4 protein (amino acids 58 to 97) distinct from the activation domain, transcriptional activation in Gal11P cells appears to depend on the Gal4-Gal11 interaction in an alternative manner that requires a nonnatural binding interface.

With respect to Gcn4, which interacts with both Gal11 and Hrs1, several mutations in other Mediator proteins have been identified that affect transcription of Gcn4-responsive genes. These include the sin4 null mutation (18), transposon insertion at MED2 (27), and the temperature-sensitive med10 mutation (13). Parts of the effects of the sin4 and med2 mutations on Gcn4 activation may be contributed by the loss of Gal11 module proteins, as both Sin4 and Med2 are necessary for the stable association of Hrs1 and Gal11 with the Mediator complex (23, 24, 26). Depletion of functional Med10 almost completely blocks HIS4 induction by Gcn4 without affecting GAL1 induction by Gal4 (13). Given that Med10 is retained in the hrs1Δ hpol II (23) and that hpol II recruitment to the HIS4 promoter is not impaired in a temperature-sensitive med10 mutant at the nonpermissive temperature (S. J. Han and Y.-J. Kim, unpublished data), Med10 does not appear to function as a direct Gcn4-binding target for hpol II recruitment. Med10 may, however, play a critical role in the postrecruitment step of transcriptional activation by Gcn4. Besides Med10, Srb5 was shown to act at a step subsequent to or at least different from that of the recruitment of Pol II holoenzyme. Artificial recruitment of the Pol II holoenzyme to a reporter gene promoter in srb5 null yeast cells does not lead to transcriptional activation, whereas in gal11 null cells it results in activated transcription at a level comparable to that observed in wild-type cells (23). Based on these findings, it is suggested that facilitated recruitment of hpol II via activator binding cannot entirely account for the requirement for Mediator proteins in gene transcription.

Multiple and redundant mechanisms for Gcn4 transcriptional activation.

The partial defects of Gal11 module-deficient hpol II in the transcription reaction (Fig. 1B) and promoter binding (Fig. 7) suggest the involvement of the Gal11 module in HIS4 transcription. However, Gcn4-mediated hpol II recruitment itself does not appear to be a major determinant of Gcn4 transcriptional activation in vivo (Fig. 6). hpol II could be recruited to the HIS4 promoter through interaction with other activators, such as Bas1, Bas2, and Rap1. These activators may interact with hpol II via a different module of Mediator. In fact, activation by Bas2 was shown to require Med9 (13), which belongs to a different module of the Mediator.

In HIS4 transcription, recruitment of hpol II via interaction with an alternative activator could be one way of overcoming defects in the Gal11 module. However, expression of a reporter gene controlled exclusively by Gcn4 still remains insensitive to the hrs1 null mutation (Fig. 6). Only when Gcn4 is brought to the promoter by a heterologous DNA-binding domain does it require the Gal11 module for reporter gene activation. These results raise the possibility that Gcn4 bound to the promoter via its own DNA-binding domain may be able to utilize an alternative activation pathway that bypasses the requirement for the Gal11 module. In this regard, several proteins, such as MBF1 (40) and BEF/ALY (44), interact directly with Gcn4 through its bZIP domain and can act as coactivators for Gcn4 or other members of the bZIP family activators. Such proteins have the potential to constitute alternative Gcn4 activation pathways that circumvent the mechanism whereby the Gcn4 activation domain interacts directly with the Gal11 module proteins.

It is noteworthy that Gcn4 activation has a differential requirement for Ada2 (a component of the Spt-Ada-Gcn5 acetyltransferase [SAGA] complex) that is dependent on the DNA target sequence (41). This implies that a coactivator requirement can be influenced by the composition of target DNA sequences that bind Gcn4. In this regard, the Gcn4 bound to the enhancer element of HIS4 promoter and the reporter gene promoters that we utilized may depend on other, more determinant regulatory pathways that do not require interactions with Gal11 module proteins. Nucleosome remodeling by the SAGA complex may play a more predominant role in HIS4 expression than does Mediator recruitment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Alan Hinnebusch, Randall Morse, Toshio Fukasawa, Hiroshi Sakurai, Masafumi Nishizawa, Richard Reese, Richard Young, Andrés Aguilera, and Roger Kornberg for yeast strains, plasmids, and antibodies; Kelly LaMarco for careful reading of the manuscript; and our colleagues in the Kim lab for helpful discussion.

This work was supported by the Creative Research Initiatives Program and the Molecular Medicine Research Group Program (98-J03-01-01-A-05) from the Korean Ministry of Science and Technology to Y.-J.K.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barberis A, Pearlberg J, Simkovich N, Farrell S, Reinagel P, Bamdad C, Sigal G, Ptashne M. Contact with a component of the polymerase II holoenzyme suffices for gene activation. Cell. 1995;81:359–368. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90389-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Björklund S, Kim Y-J. Mediator of transcriptional regulation. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:335–337. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(96)10051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown C E, Lechner T, Howe L, Workman J L. The many HATs of transcription coactivators. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:15–19. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01516-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown T A, Evangelista C, Trumpower B L. Regulation of nuclear genes encoding mitochondrial proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6836–6843. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.23.6836-6843.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burley S K, Roeder R G. Biochemistry and structural biology of transcription factor IID (TFIID) Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:769–799. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.004005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drysdale C M, Jackson B M, McVeigh R, Klebanow E R, Bai Y, Kokubo T, Swanson M, Nakatani Y, Weil P A, Hinnebusch A G. The Gcn4p activation domain interacts specifically in vitro with RNA polymerase II holoenzyme, TFIID, and the Adap-Gcn5p coactivator complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1711–1724. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.3.1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farrell S, Simkovich N, Wu Y, Barberis A, Ptashne M. Gene activation by recruitment of the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2359–2367. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.18.2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fassler J S, Winston F. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae SPT13/GAL11 gene has both positive and negative regulatory roles in transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:5602–5609. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.12.5602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flanagan P M, Kelleher III R J, Sayre M H, Tschochner H, Kornberg R D. A mediator required for activation of RNA polymerase II transcription in vitro. Nature. 1991;350:436–438. doi: 10.1038/350436a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green M R. TBP-associated factors (TAFIIs): multiple, selective transcriptional mediators in common complexes. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:59–63. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guarente L, Yocum R R, Gifford P. A GAL10-GAL1 hybrid yeast promoter identifies the GAL4 regulatory region as an upstream site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:7410–7414. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.23.7410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guarente L. Yeast promoter and lacZ fusions designed to study expression of cloned genes in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1983;101:181–191. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han S J, Lee Y C, Gim B S, Ryu G-H, Park S J, Lane W S, Kim Y-J. Activator-specific requirement of yeast Mediator proteins for RNA polymerase II transcriptional activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:979–988. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hengartner C J, Thompson C M, Zhang J, Chao D M, Liao S-M, Koleske A J, Okamura S, Young R A. Association of an activator with an RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Genes Dev. 1995;9:897–910. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.8.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holstege F C P, Jennings E G, Wyrick J J, Lee T I, Hengartner C J, Green M R, Golub T R, Lander E S, Young R A. Dissecting the regulatory circuitry of a eukaryotic genome. Cell. 1998;95:717–728. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81641-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson B M, Drysdale C M, Natarajan K, Hinnebusch A G. Identification of seven hydrophobic clusters in GCN4 making redundant contributions to transcriptional activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5557–5571. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang Y W, Stillman D J. Involvement of the SIN4 global transcriptional regulator in the chromatin structure of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:4503–4514. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.10.4503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang Y W, Stillman D J. Regulation of HIS4 expression by the Saccharomyces cerevisiae SIN4 transcriptional regulator. Genetics. 1995;140:103–114. doi: 10.1093/genetics/140.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim Y-J, Björklund S, Li Y, Sayre M H, Kornberg R D. A multiprotein Mediator of transcriptional activation and its interaction with the C-terminal repeat domain of RNA polymerase II. Cell. 1994;77:599–608. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90221-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koh S S, Ansari A Z, Ptashne M, Young R A. An activator target in the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Mol Cell. 1998;1:895–904. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80088-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koleske A J, Young R A. An RNA polymerase II holoenzyme responsive to activators. Nature. 1994;368:466–469. doi: 10.1038/368466a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee Y C, Kim Y-J. Requirement of a functional interaction between Mediator components Med6 and Srb4 in RNA polymerase II transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5364–5370. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee Y C, Park J M, Min S, Han S J, Kim Y-J. An activator binding module of yeast RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2967–2976. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Y, Björklund S, Jiang Y W, Kim Y-J, Lane W S, Stillman D J, Kornberg R D. Yeast global transcriptional regulators Sin4 and Rgr1 are components of mediator complex/RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10864–10868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.10864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moqtaderi Z, Bai Y, Poon D, Weil P A, Struhl K. TBP-associated factors are not generally required for transcriptional activation in yeast. Nature. 1996;383:188–191. doi: 10.1038/383188a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Myers L C, Gustafsson C M, Hayashibara K C, Brown P O, Kornberg R D. Mediator protein mutations that selectively abolish activated transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:67–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Natarajan K, Jackson B M, Zhou H, Winston F, Hinnebusch A G. Transcriptional activation by Gcn4p involves independent interactions with the SWI/SNF complex and the Srb/Mediator. Mol Cell. 1999;4:657–664. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nishizawa M, Taga S, Matsubara A. Positive and negative transcriptional regulation by the yeast GAL11 protein depends on the structure of the promoter and a combination of cis elements. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;245:301–312. doi: 10.1007/BF00290110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oelgeschläger T, Tao Y, Kang Y K, Roeder R G. Transcription activation via enhanced preinitiation complex assembly in a human cell-free system lacking TAFIIs. Mol Cell. 1998;1:925–931. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orphanides G, Lagrange T, Reinberg D. The general transcription factors of RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2657–2683. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.21.2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piruat J I, Chávez S, Aguilera A. The yeast HRS1 gene is involved in positive and negative regulation of transcription and shows genetic characteristics similar to SIN4 and GAL11. Genetics. 1997;147:1585–1594. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.4.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Platt A, Reece R J. The yeast galactose genetic switch is mediated by the formation of a Gal4p-Gal80p-Gal3p complex. EMBO J. 1998;17:4086–4091. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.4086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roeder R G. The role of general initiation factors in transcription by RNA polymerase II. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:327–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sadowski I, Ma J, Triezenberg S, Ptashne M. Gal4-VP16 is an unusually potent transcriptional activator. Nature. 1988;335:563–564. doi: 10.1038/335563a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sakai A, Shimizu Y, Kondou S, Chibazakura T, Hishinuma F. Structure and molecular analysis of RGR1, a gene required for glucose repression of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:4130–4138. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.8.4130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sakurai H, Kim Y-J, Ohishi T, Kornberg R D, Fukasawa T. The yeast GAL11 protein binds to the transcription factor IIE through Gal11 regions essential for its in vivo function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9488–9492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santos-Rosa H, Clever B, Heyer W-D, Aguilera A. The yeast HRS1 gene encodes a polyglutamine-rich nuclear protein required for spontaneous and hpr1-induced deletions between direct repeats. Genetics. 1996;142:705–716. doi: 10.1093/genetics/142.3.705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sikorski R S, Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strahl-Bolsinger S, Hecht A, Luo K, Grunstein M. SIR2 and SIR4 interactions differ in core and extended telomeric heterochromatin in yeast. Genes Dev. 1997;11:83–93. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takemaru K-I, Harashima S, Ueda H, Hirose, S. S. Yeast coactivator MBF1 mediates GCN4-dependent transcriptional activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4971–4976. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.4971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tavernarakis N, Thireos G. The DNA target sequence influences the dependence of the yeast transcriptional activator Gcn4 on cofactors. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;253:766–769. doi: 10.1007/s004380050382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verrijzer C P, Tjian R. TAFs mediate transcriptional activation and promoter selectivity. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:338–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vignali M, Hassan A H, Neely K E, Workman J L. ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1899–1910. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.6.1899-1910.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Virbasius C-M A, Wagner S, Green M R. A human nuclear-localized chaperone that regulates dimerization, DNA binding, and transcriptional activity of bZIP proteins. Mol Cell. 1999;4:219–228. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80369-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walker S S, Reese J C, Apone L M, Green M R. Transcription activation in cells lacking TAFIIs. Nature. 1996;383:185–188. doi: 10.1038/383185a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu S-Y, Kershnar E, Chiang C-M. TAFII-independent activation mediated by human TBP in the presence of the positive cofactor PC4. EMBO J. 1998;17:4478–4490. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.15.4478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu L, Morse R H. Chromatin opening and transactivator potentiation by RAP1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5279–5288. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]