Abstract

Inflammatory cytokines augment humoral responses by stimulating antibody production and inducing class-switching. In women, genital inflammation (GI) significantly modifies HIV risk. However, the impact of GI on mucosal antibodies remains undefined. We investigated the impact of GI, pre-HIV infection, on antibody isotypes and IgG subclasses in the female genital tract. Immunoglobulin (Ig) isotypes, IgG subclasses and 48 cytokines were measured prior to HIV infection in cervicovaginal lavages (CVL) from 66 HIV seroconverters (cases) and 66 matched HIV-uninfected women (controls) enrolled in the CAPRISA 004 and 008 1% tenofovir gel trials. Pre-HIV infection, cases had significantly higher genital IgM (4.13; IQR, 4.04–4.19) compared to controls (4.06; IQR, 3.90–4.20; p = 0.042). More than one-quarter of cases (27%) had GI compared to just over one-tenth (12%) in controls. Significantly higher IgG1, IgG3, IgG4 and IgM (all p < 0.05) were found in women stratified for GI compared to women without. Adjusted linear mixed models showed several pro-inflammatory, chemotactic, growth factors, and adaptive cytokines significantly correlated with higher titers of IgM, IgA and IgG subclasses (p < 0.05). The strong and significant positive correlations between mucosal antibodies and markers of GI suggest that GI may impact mucosal antibody profiles. These findings require further investigation to establish a plausible biological link between the local inflammatory milieu and its consequence on these genital antibodies.

Subject terms: Immunology, Diseases

Introduction

Women and girls account for approximately half of all new HIV infections globally. In sub-Saharan Africa, young women aged 15–24 years are twice as likely to be HIV infected than similarly aged men and account for 24% of all new HIV infections1. Understanding the biology underlying the vulnerability of the female genital tract (FGT), the predominant site of heterosexual HIV transmission, is thus a major focus for HIV prevention efforts.

Genital inflammation (GI) defined as elevated levels of five of nine key pro-inflammatory cytokines in the FGT confers a three-fold higher-risk of HIV acquisition2. While the causes of GI remain mostly undefined, attributable factors for pre-existing GI include sexually transmitted infections (STIs)3, vaginal microbial dysbiosis3, hormonal contraceptive use4 and various sexual practices5. GI was previously established as a significant predictor of HIV acquisition in women from the CAP004 tenofovir gel trial2. Further cohort analyses showed that women without GI had 75% protection from HIV infection compared to − 10% in women with GI, despite a similarly high tenofovir gel adherence6. In HIV-uninfected women, elevated genital cytokines were significantly associated with increased mucosal target CD4+T cells and markers for epithelial barrier disruption7 supporting the plausible link between GI and enhanced HIV risk.

Antibodies in the FGT may play an important role in protection against mucosal transmission of HIV8. In addition to viral neutralization, antibodies can confer non-neutralizing effector functions such as antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP) and antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC)9,10. Among the immunoglobulins, IgM is the first to appear in response to any infection, followed by cytokine-mediated class switching to IgG and IgA11–13. Despite relatively high IgA, IgG predominates in the FGT14,15. Several studies have attributed the presence of genital tract HIV-specific IgA as a correlate of protection in highly exposed persistently seronegative (HEPS) women16–18. In the RV144 trial vaccinees, circulating Env V1-V2 IgG correlated with lower HIV-1 risk through enhanced ADCC, ADCP and complement activation19,20. Whether these antibodies transduced from the circulation to the mucosal compartment to confer protection remains undefined. Collectively these findings underscore the importance of both locally and/or transduced antibody responses which may help to mitigate HIV infections.

Inflammatory cytokines and chemokines influence B cell functions, including antibody production, isotype and IgG subclass switching21,22. Previously, cytokines were shown to influence effector functions of antibodies in the HIV-infected individuals23. Elevated inflammatory cytokines in the FGT were also associated with increased levels of protease expression leading to loss of antibody functions through proteolytic cleavage7,24. Our group showed significant associations between antibodies and pro-inflammatory cytokines in the semen of HIV-infected men25 shedding light on the profile of mucosal antibodies in relation to local cytokines. Less well defined is the relationship between local cytokines and humoral immunity in the FGT. In this study we measured the antibody isotype and subclasses in the FGT of women from the CAPRISA 004 and CAPRISA 008 1% tenofovir gel trials26,27 in relation to the mucosal cytokines that are used to gauge GI. Understanding the relationship between pre-existing GI and antibody isotypes and subclasses in the FGT are also important to the design of more effective prevention strategies.

Methods

Study participants and sample collection

This is a retrospective sub-study of N = 132 women from the CAPRISA 004 and CAPRISA 008 clinical trial studies. CAPRISA 004 was a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial assessing the effectiveness of tenofovir gel to prevent HIV27. CAPRISA 008 was a two-arm, open-label, randomized controlled, non-inferiority implementation trial assessing whether tenofovir gel provision could be effectively integrated into family planning clinics26. All participants provided written informed consent for study participation and the sub-study was approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of University of KwaZulu-Natal (BE0207/17). All the experimental procedures are in accordance with the relevant ethical guidelines and regulations.

Cervico-vaginal lavage (CVL) samples were obtained at the pre-infection timepoint from women who subsequently became HIV-infected (cases, n = 66) and women who remained uninfected (controls, n = 66). Pre-infection CVLs for each of the cases were the last HIV negative samples before testing HIV positive by PCR. The cases and controls were matched by time in study and tenofovir use. In controls, their timepoint was matched to the pre-infection timepoint for the cases. All the samples were chosen according to a 1:1 ratio of cases to controls. CVL samples were collected and stored from each woman according to the method described by Bebell et al28, CVL sample collection was deferred if women were menstruating.

IgG subclasses and Ig isotype quantification in CVL

IgG subclasses (IgG1, IgG2, IgG3 and IgG4) and isotypes IgA and IgM in CVL were quantified using the Bio-Plex Pro™ Human Isotyping Panel kit (Bio-Rad, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The Bio-Plex 200 multiplex system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) was used to determine the levels of immunoglobulins. Mean Fluorescent Intensity (MFI) were determined by 4-PL logistic regression using the Bioplex Manager 6.0 software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). CVL samples were diluted at 1:10 in sterile PBS to ensure that the MFI for the IgG subclasses and isotypes were detected in the linear range of the standard curve.

Genital cytokine measurement by multiplex ELISA

Concentrations of 48 cytokines involved in different immunological functions were measured using Bio-Plex Pro™ Human Cytokine Group I 27-Plex Panel and Group II 21-Plex Panel (Bio-Rad, USA) and Single-plex Human Magnetic Luminex Assay (R&D systems, USA) in the CVLs. The cytokine panel included: interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-1Rα, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-12p40, IL-16, IL-18, IL-1α, IL-2RA, IL-3, IL-13, IL-15, IL-17, basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF), cutaneous T-cell attracting chemokine (CTACK), eotaxin, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM–CSF), growth regulated (GRO)-α, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), interferon (IFN)-γ, IFN-α2, interferon gamma-induced protein (IP)-10, leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP)-1, MCP-3, macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), monokine induced by gamma-Interferon (MIG), macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF), macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α, MIP-1β, nerve growth factor (NGF)-β, platelet derived growth factor (PDGF)-ββ, regulated upon activation normal T cell expressed and presumably secreted (RANTES), stem cell factor (SCF), stem Cell Growth Factor (SCGF)-β, stromal derived factor (SDF)-1α, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, TNF-β, TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand (TRAIL), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). The sensitivity of these kits ranged between 0.2 and 45.2 pg/ml for each of the 48 cytokines measured. Data was collected using Bio-Plex Manager software version 6.1, and a 5 PL regression formula was used to calculate sample concentrations from the standard curves. Cytokine levels below the lower limit of detection (LLOD) of the assay were reported as the mid-point between zero and the lowest concentration measured for that given cytokine. To control for inter-plate variability, CVL samples from the same participant were analyzed on separate plates.

Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics were summarized using medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables and frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. Proportions were compared using the McNemar test and Bowkers test. The Wilcoxon signed rank test and paired t-tests were used to compare concentrations of isotypes and IgG subclasses for case-matched-control analyses. Multivariable linear mixed models with a random effect of the matched pairs were used to determine associations between cytokines and Ig isotypes and IgG subclasses. The models were adjusted for age, tenofovir use, HSV-2, the number of vaginal sex acts, contraceptives, male condom use and HIV infection status. GI was defined as having at least 5 of 9 elevated cytokines in the 75th upper quartile using previously published scoring criteria2. Mann–Whitney U test and unpaired t-test were performed to compare isotype and IgG subclasses between women with GI versus women without GI within cases and controls. Similar tests were also used for the stratified analyses based on tenofovir use within cases and controls to compare isotype and IgG subclasses (supplementary data). Cytokine concentrations were log transformed to ensure normality. P-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini–Hochberg method. All statistical analysis were performed using GraphPad Prism Version 8.4.3 and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary NC, USA).

Results

Study participants

In this case–control sub-study, a total of 132 mucosal specimens of women from CAPRISA 004 (N = 90) and CAPRISA 008 (N = 42) trials were analyzed. Of these, cases represent women (n = 66) at their pre-HIV infection timepoint who subsequently became HIV-infected. Controls represent women (n = 66) who remained HIV-uninfected and were matched to cases by time in study. No significant differences were found between cases and controls with respect to age, education, relationship status, condom use, lifetime number of partners, HSV-2 positivity at time of study enrolment (Table 1). The majority of women (91.7%) reported being in a stable relationship. Age of sexual debut was significantly lower in cases [median 17 years; interquartile range (IQR), 16–18 years] compared to controls and (18; IQR, 16–19; p = 0.008). Depo-Provera (DMPA) was the most common contraceptive method used in both groups. Herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2) seropositivity was observed in 74% of the cases and 65% of the controls. Active sexually transmitted infections (STIs) such as Chlamydia, Gonorrhoea and Trichomonas tests were performed in 42 women from CAPRISA 008 only. Of these, six cases and one control had STIs.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of case and controls included in this study.

| Demographics | Cases (N = 66) | Controls (N = 66) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 23 (21–27) | 24 (21–28) | 0.310 |

| Highest level of education completed: | 0.446 | ||

| Less than primary, % (n) | 19.7 (13) | 7.6 (5) | |

| Primary Complete, % (n) | 34.8 (23) | 43.9 (29) | |

| High school complete, % (n) | 42.4 (28) | 47 (31) | |

| Tertiary complete, % (n) | 3.0 (2) | 1.5 (1) | |

| Relationship status: | 0.704 | ||

| Married, % (n) | 4.5 (3) | 9.1 (6) | |

| Stable partner, % (n) | 84.8 (56) | 84.8 (56) | |

| Casual partner, % (n) | 6.1 (4) | 1.5 (1) | |

| Other, % (n) | 4.5 (3) | 4.5 (3) | |

| Sexual behaviour: | |||

| Age (years) of sexual debut, median (IQR) | 17 (16–18) | 18 (16–19) | 0.008 |

| Number of lifetime sexual partners, median (IQR) | 2 (1.5–4) | 2 (1–3) | 0.323 |

| Number of vaginal sex acts in the last 30 days Median (IQR) | 4 (3–8) | 6 (3–10) | 0.060 |

| Contraceptive use: | * | ||

| Depo-Provera, % (n) | 71.2 (47) | 71.2 (47) | |

| Oral contraceptive, % (n) | 10.6 (7) | 13.6 (9) | |

| Nur-isterate, % (n) | 18.2 (12) | 7.6 (5) | |

| Tubal Ligation, % (n) | 0 | 7.6 (5) | |

| Condom use: | 0.481 | ||

| Always % (n) | 34.8 (23) | 31.8 (21) | |

| Sometimes % (n) | 59.1 (39) | 65.2 (43) | |

| Never % (n) | 6.1 (4) | 3.0 (2) | |

| STI Testing | |||

| Proportion HSV-2 positive % (n) | 75.4 (49) | 64.6 (42) | 0.26 |

IQR, interquartile range. HSV-2, Herpes simplex virus-2. A p-value of < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

*The Bowker test of symmetry failed as there were no events hence the p-value could not be computed.

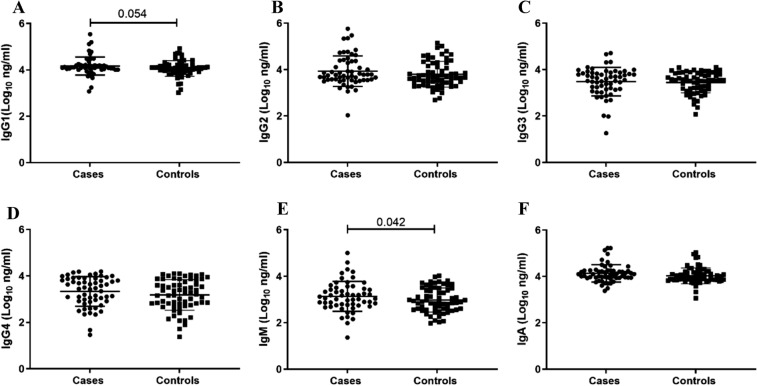

Higher mucosal IgM in cases at pre-HIV infection timepoint

We investigated mucosal IgG subclasses and isotypes in the FGT to determine their differences in the women who become HIV-infected compared women who remained uninfected (Fig. 1). IgM was significantly higher in cases (4.13; IQR, 4.04–4.19) compared to controls (4.06; IQR, 3.90–4.20; p = 0.042) (Fig. 1E). IgG1 trended higher in cases (3.05; IQR, 2.76–3.48) than for controls (2.90; IQR, 2.57–3.46; p = 0.054) (Fig. 1A). IgG2, IgG3, IgG4 and IgA were similar between cases and controls (Fig. 1B–D and F).

Figure 1.

Comparison of mucosal immunoglobulin IgG subclasses and isotypes (Log10 ng/ml) between matched controls and cases pre-HIV infection. Each data point represents an individual sample. Cases represent women who subsequently became HIV-infected, and controls represent women who remained HIV-uninfected. The scatter dot plot includes the medians and interquartile ranges. Wilcoxon signed rank test and paired t-tests were used to compare between the case-matched-control groups and p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

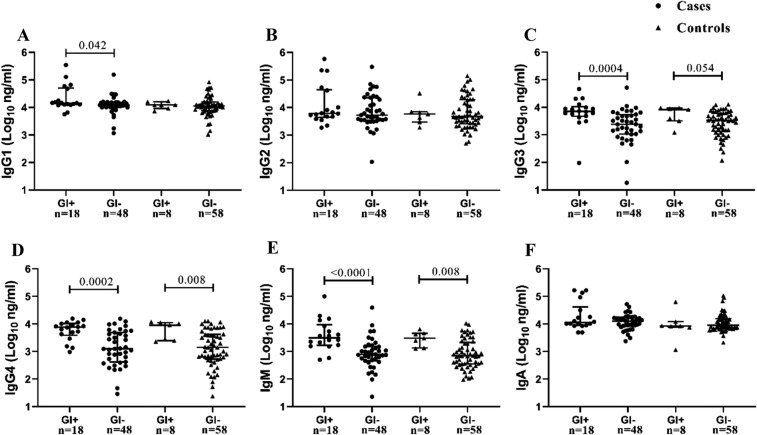

Mucosal IgG and IgM significantly increases with genital inflammation

We next determined the effects of GI on antibodies by further stratifying women according to the presence (GI+) or absence (GI−) of GI irrespective of HIV infection. Among cases, women with GI had significantly higher IgG1 (p = 0.042), IgG3 (p = 0.0004), IgG4 (p = 0.0002) and IgM (p < 0.0001) compared to women without GI (Fig. 2A and C–E). We found no significant difference for IgG2 and IgA among GI+ and GI− women (Fig. 2B and F). IgG3, IgG4 and IgM remained significant even after multiple comparisons adjustment. Similarly, in controls, women with GI had significantly higher concentrations of IgG4 (p = 0.008), IgM (p = 0.008) (Fig. 2D and E) and IgG3 trended higher (p = 0.054) (Fig. 2C) compared to women without GI, with IgG4 and IgM remaining significantly higher after multiple comparisons adjustment. This finding highlights the differential profile of antibodies in the presence of inflammation. In order to understand the effect of tenofovir in modifying genital antibodies we further stratified cases and controls by tenofovir use (tenofovir and placebo). Within the cases, and irrespective of the treatment arm, whether women used tenofovir or placebo, concentrations of IgG2 (p = 0.019), IgG3 (p = 0.002), IgG4 (p = 0.0001) and IgM (p = 0.004) were significantly higher in women with GI compared to women without GI (Supplementary Fig. S1B–E). Similarly, among the controls, significantly higher IgG3 (p = 0.045) and IgM (p = 0.008) were observed in women with GI compared to women without GI (Supplementary Fig. S2C and E).

Figure 2.

Comparison of mucosal IgG subclasses and isotypes in women stratified for presence of genital inflammation (GI+) or absence of genital inflammation (GI−) within cases [GI+ (n = 18) and GI− (n = 48)] and controls [GI+ (n = 8) and GI− (n = 58)] pre-HIV infection. Each data point represents an individual sample, the line-bars represents medians and interquartile ranges. Mann–Whitney U test and unpaired t-tests were used to compare between groups and p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Black circle represents cases and black triangle represents controls.

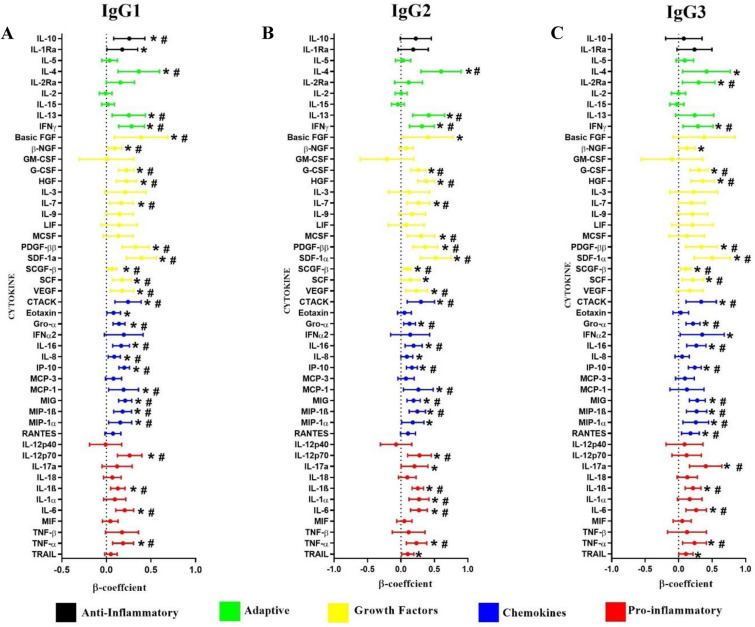

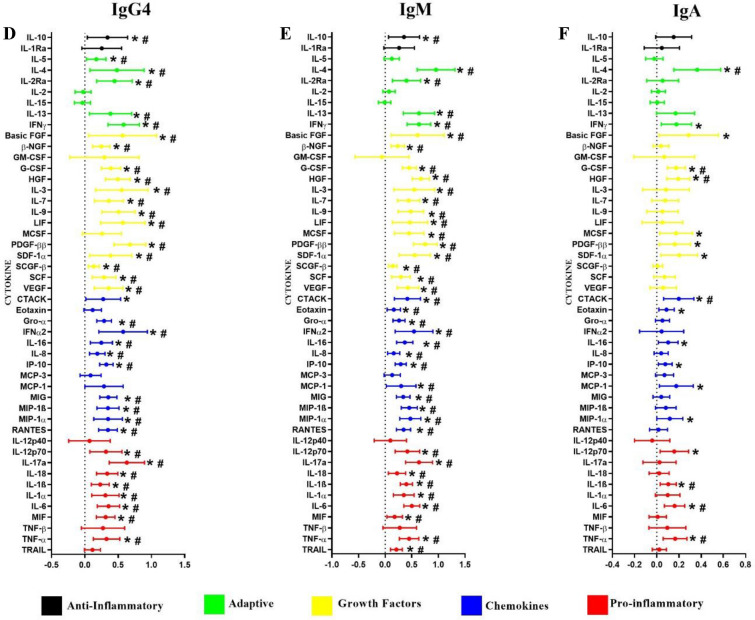

Genital inflammatory cytokines significantly associated with IgG subclasses, IgM and IgA isotype

Multivariable linear mixed models with a random effect of the matched pairs were performed to determine the associations between the genital cytokines and immunoglobulin isotypes and IgG subclasses. This model was adjusted for age, HSV-2 status, the number of vaginal sex acts, contraceptive method, condom use, tenofovir use and HIV infection status. Most notably, subclass IgG2 and isotype IgM were significantly and positively associated with all the nine cytokines that defined GI (IL-6, IL-8, IP-10, IL-1α, IL-1β, TNF-α, MCP-1, MIP-1α and MIP-1β) (p < 0.05), all except MIP-1α remained significant after multiple comparison adjustment (Fig. 3B and E). In addition, IgG1 and IgG3 significantly and positively associated with eight (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, IP-10, IL-1β, MCP-1, MIP-1α and MIP-1β) and six (IL-6, IP-10, IL-1β, TNF-α, MIP-1α and MIP-1β) cytokines (p < 0.05) respectively (Fig. 3A and C). IgG4 also showed positive and significant associations with all eight cytokines that fits the definition of GI, excluding MCP-1 (p < 0.05) and remained significant after multiple comparison adjustment (Fig. 3D). IgA was positively associated with six of nine genital inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IP-10, IL-1β, TNF-α, MCP-1, MIP-1α) (Fig. 3F) and TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β remained significant after multiple comparison adjustment. Besides the nine key pro-inflammatory cytokines, subclasses IgG1-IgG4 and isotype IgM and IgA were significantly and positively associated with several anti-inflammatory, adaptive, growth factors and chemotactic cytokines (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3). Together, these data underscore the compartment-specific associations between cytokines and antibody subclasses and isotypes.

Figure 3.

Associations between genital cytokines and mucosal IgG1 (A), IgG2 (B), IgG3 (C), IgG4 (D), IgM (E) and IgA (F). β-coefficients and p-values were determined using multivariable linear mixed models with a random effect of the matched pairs (N = 132). The multivariable models were adjusted for age, HSV-2 status, the number of vaginal sex acts, contraceptive method, condom use, tenofovir use and HIV infection status. β-coefficients are indicated by shaded circles and error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. P-values < 0.05 are represented by *, and those p-values that are significant after multiple comparisons adjustment are represented by #.

Discussion

The majority of HIV infections in women are acquired during sexual intercourse, making it imperative to understand the immune microenvironment of the FGT for developing strategies to prevent infections. A significant effort has been made to understand if and how antibodies can confer protection in the FGT. Given the significant evidence of GI and increased HIV risk, very little is known about how GI can impact the profile and functions of antibodies in the genital tract. Here, we detected that in the presence of pre-existing GI, mucosal IgG subclasses and isotypes were significantly increased in both women who became HIV-infected and in those who remained uninfected.

In this case–control analyses we found significantly higher IgM in cases compared to controls which may indicate that mucosal IgM can be an early marker of pathogen exposure. Circulating IgM are elicited during the early stage in response to any infection including HIV29. Moreover, HIV-specific IgM were functionally effective in neutralizing and reducing HIV infections in cervicovaginal tissue models30. Natural IgM can limit HIV infection by modulating inflammation and T cell activation31,32. In addition, IgM can directly bind to CD4+T cells and chemokine receptors CCR5, hindering HIV entry33. Together, these data highlight the varied functional capability of pentameric IgM to effectively crosslink and capture virus thereby reducing HIV infection. Upon class switching from IgM, IgG1 predominates during acute and chronic HIV infection11. We also found higher IgG1 in cases compared to controls. HIV-specific IgG1 have been associated with viral control and slower progression to HIV infection34,35. These data suggest that in the cases, at the pre-HIV infection stage, sexual exposure to HIV or other pathogens may have elicited increased mucosal IgG1 and IgM titres. However, whether these antibodies are functionally competent and HIV-specific IgG or IgM, remains undefined.

To determine genital antibody profiles in the presence of GI, women were stratified for the presence or absence of GI. IgM, IgG1, IgG3 and IgG4 were significantly higher in women with GI compared to women without GI. We previously reported higher titer of HIV-specific IgG and IgA in the genital tracts of women with breakthrough HIV infections who used tenofovir gel from the CAPRISA 004 trial36. However, in this study we found that irrespective of tenofovir use there was significantly increased IgG2, IgG3, IgM and IgG4 in the presence of GI. Together these data infer that tenofovir gel use was less likely than GI to modify genital antibodies. However, we cannot over interpret these data and the limited sample size in each sub-category precludes accurate conclusions. Both in vivo and in vitro studies suggested that IgM increases as a compensatory drive to resolve inflammation32,37. Therefore, increased mucosal IgM among women with GI may be in response to the inflammation. Studies have demonstrated cytokine-induced enhancement of IgG subclasses and isotypes38,39 explaining in part the increased antibodies with GI. Alternatively, compromised barrier integrity may also account for the increased antibody transudate in the presence of GI. Inflammation is strongly associated with the glycosylation of the fragment crystallizable (Fc) region of IgG subclasses particularly40. This reduces antibody affinities for Fcγ receptors decreasing functional activities41,42. Besides glycosylation, increased proteases have been associated with elevated inflammatory cytokines in the FGT7 which can lead to non-specific proteolytic antibody degradation compromising the function of the antibodies24. Therefore, the impact of GI on antibody functions in the genital tract need to be investigated in future studies. Nevertheless, the findings suggest that inflammatory environment in the FGT may be responsible for maintaining specific antibody responses, but this needs further investigation in large cohort studies.

Cytokines have been shown to influence Ig class switching and subclass synthesis39,43. In this study we demonstrated a link between genital inflammatory cytokines and mucosal antibodies. We found that prior to HIV infection, mucosal IgG subclasses and isotypes were positively and significantly associated with several inflammatory cytokines: TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-10 and IL-6; adaptive cytokines: IL-13, IL-4 and IFN-γ and chemotactic and growth factors: MIP-1α, MIP-1β, MCP-1, IL-8, CTACK and MIG after adjusting for potential confounders. Positive associations were observed between IL-13 and IgG4 and IgM. These data corroborate previous findings of IL-13 induced synthesis of IgM and IgG4 in human B cells in the presence of activated T cells44. Furthermore, IL-6 along with IFN-γ can inhibit IgG1 and enhance IgG2 production in stimulated PBMCs demonstrating the differential regulation of cytokines on human IgG subclass production39. The significantly direct association between IL-7 and IgG4 is also supported by a study showing IL-7 driven class switching to IgG445. Collectively, these preliminary findings suggest that the local isotypes and IgG subclasses may be influenced, in part, by pre-existing GI.

The strength of the study is the evaluation of rare pre-HIV infection mucosal samples from high-risk South African women in two clinical trials investigating mucosal Ig isotype/subclasses in relation to cytokines. Mucosal antibody profiling may be an additional predictor of pre-existing GI. However, these studies would indeed require large cohorts evaluating both mucosal cytokines and antibodies longitudinally and in parallel to establish their validity as an additional surrogate for GI. Understanding the association between GI and antibodies can provide further insight for developing effective HIV prevention strategies for at risk populations with underlying susceptibilities to GI. This study however has several limitations. We did not measure pathogen-specific antibodies, an important surrogate indicator of bacterial and viral pathogen exposure. All the participants were on some form of hormonal contraceptives, a mandatory inclusion criterion for trial participation. Therefore, we could not account for phase of the menstrual cycle, which is known to affect inflammatory cytokines and antibodies46,47. A previous study of women on DMPA showed significantly increased IgG1, IgG2 and IgA and IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, MIP-1β, IP-10, IL-8 and TGF-β cytokines in the FGT48. These data affirm the local impact of exogenous hormones on immune responses in the FGT. In this study we adjusted for hormonal contraceptive use as one of the potential confounders in the linear mixed model. However, further studies are needed to understand the impact of endogenous and exogenous hormones on GI and mucosal antibodies.

Another caveat to the present study is the lack of data for STIs and BV in the CAPRISA 004 trial which precluded the ability to establish significant associations of GI with STIs and BV. Previous studies have shown that both STIs and BV can induce inflammation in the genital tract impacting the mucosal immune responses49,50. Inflammatory cytokines in the FGT were similar in women with symptomatic and asymptomatic STIs51. In addition, women with asymptomatic STIs had significantly elevated cytokines compared to women with no STIs or BV51. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) recognize pathogens including STIs inducing specific T-cell and antibody response52,53. In addition, TLRs recognize pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) of bacterial STIs inducing NF-κB driven immune response resulting in inflammatory cytokine production 54,55. Therefore, to exclude the bias of GI due to STIs and BV, these two factors should be adjusted for as confounders. Future studies would, therefore, require large sample sizes to account for the selection bias and confounding of GI secondary to STIs and BV. Despite these shortcomings, our data provides an enhanced dissection of how GI can affect the quantities of mucosal antibodies and, potentially impact their functions through the predominance of certain isotypes or subclasses over the other. Our findings suggest that GI can shape or reconfigure the mucosal Ig subclass and isotype signature. However, further investigation is required to verify a plausible link between the local inflammatory milieu and the effect on genital antibodies and their functions. These data may be important for future HIV vaccine efficacy studies.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank CAPRISA 004 and CAPRISA 008 participants for their personal contribution to the research. We also acknowledge the CAPRISA study and protocol teams for coordinating the collection, processing, and storage of the samples. The CAPRISA 004 trial was funded by USAID through FHI360 and CONRAD with additional support provided by the South African Department of Science and Technology (DST). The CAPRISA 008 Trial was funded by USAID through CONRAD under a Cooperative Agreement (GPO-A-00-08-00005-00), PEPFAR, DST through the Technology Innovation Agency and the MACAIDS Fund through the Tides Foundation (Grant # TFR11-01545). P.S., T.P., J.S.P., L.R.M. and D.A. received support from the Department of Science and Innovation (DSI)-National Research Foundation (NRF) Centre of Excellence in HIV Prevention (Grant No. 96354). P.S. received support from the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC) Special Initiative (Grant no. 96151) and S&F Scarce Skills Postdoctoral Fellowships (Grant no.132714). L.J.P.L. received funding from the NRF Research Career Advancement Fellowship award, a SANTHE Path to Independence award, and a FLAIR Fellowship supported by the African Academy of Sciences and the Royal Society. A.S. is supported by EDCTP Career Development Fellowship (TMA2016CDF-1582). J.S.P., L.R.M. and D.A. were funded by NIH (5R01AI111936). D.A. was also funded through the SAMRC Self-Initiated Grant and the NRF of South Africa Thuthuka (grant#TTK160517165310), the NRF Research Career Advancement Fellowship (grant#RCA13101656388), the Polio Research Foundation of South Africa (PRF 17/02) and an EDCTP Senior Fellowship (grant#TMA2017SF-1960).

Author contributions

P.S. performed experiments, analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript writing, proof reading and final approval. T.P. performed experiments, analysis, and interpretation of data. L.J.P.L performed part experiments and analysis of cytokine data. A.S. participated in the analyses of all data. L.M. contributed to the data collection and editing of the manuscript. F.O. contributed to the statistical analysis plan. D.A. carried out the conception, designed, received funds to carry out the study, interpreted and analysed the data, wrote, and approved the manuscript. J.S.P., Q.A.K., S.A.K., C.B., L.R.M., contributed to the editing of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-02954-0.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. Global HIV and AIDS statistics—2020 fact sheet. (2020).

- 2.Masson L, et al. Genital inflammation and the risk of HIV acquisition in women. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:260–269. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masson L, et al. Defining genital tract cytokine signatures of sexually transmitted infections and bacterial vaginosis in women at high risk of HIV infection: a cross-sectional study. Sex Transm Infect. 2014;90:580–587. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2014-051601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghanem KG, et al. Influence of sex hormones, HIV status, and concomitant sexually transmitted infection on cervicovaginal inflammation. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:358–366. doi: 10.1086/427190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scholes D, et al. Vaginal douching as a risk factor for acute pelvic inflammatory disease. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:601–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKinnon LR, et al. Genital inflammation undermines the effectiveness of tenofovir gel in preventing HIV acquisition in women. Nat Med. 2018;24:491–496. doi: 10.1038/nm.4506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnold KB, et al. Increased levels of inflammatory cytokines in the female reproductive tract are associated with altered expression of proteases, mucosal barrier proteins, and an influx of HIV-susceptible target cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2016;9:194–205. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruprecht RM, Marasini B, Thippeshappa R. Mucosal antibodies: defending epithelial barriers against HIV-1 invasion. Vaccines (Basel) 2019;7:194. doi: 10.3390/vaccines7040194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alpert MD, et al. ADCC develops over time during persistent infection with live-attenuated SIV and is associated with complete protection against SIV(mac)251 challenge. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002890. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boesch AW, Brown EP, Ackerman ME. The role of Fc receptors in HIV prevention and therapy. Immunol Rev. 2015;268:296–310. doi: 10.1111/imr.12339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomaras GD, Haynes BF. HIV-1-specific antibody responses during acute and chronic HIV-1 infection. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2009;4:373–379. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32832f00c0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lorenz M, Jung S, Radbruch A. How cytokines control immunoglobulin class switching. Behring Inst Mitt. 1995;96:97–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moens L, Tangye SG. Cytokine-mediated regulation of plasma cell generation: IL-21 takes center stage. Front Immunol. 2014;5:65. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belec L, Tevi-Benissan C, Lu XS, Prazuck T, Pillot J. Local synthesis of IgG antibodies to HIV within the female and male genital tracts during asymptomatic and pre-AIDS stages of HIV infection. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1995;11:719–729. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brandtzaeg P. Mucosal immunity in the female genital tract. J Reprod Immunol. 1997;36:23–50. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0378(97)00061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seaton KE, et al. HIV-1 specific IgA detected in vaginal secretions of HIV uninfected women participating in a microbicide trial in Southern Africa are primarily directed toward gp120 and gp140 specificities. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e101863. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tudor D, et al. HIV-1 gp41-specific monoclonal mucosal IgAs derived from highly exposed but IgG-seronegative individuals block HIV-1 epithelial transcytosis and neutralize CD4(+) cell infection: an IgA gene and functional analysis. Mucosal Immunol. 2009;2:412–426. doi: 10.1038/mi.2009.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirbod T, et al. HIV-neutralizing immunoglobulin A and HIV-specific proliferation are independently associated with reduced HIV acquisition in Kenyan sex workers. AIDS. 2008;22:727–735. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f56b64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lopez Angel CJ, Tomaras GD. Bringing the path toward an HIV-1 vaccine into focus. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16:e1008663. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yates NL, et al. Vaccine-induced Env V1–V2 IgG3 correlates with lower HIV-1 infection risk and declines soon after vaccination. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:228ra239. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vazquez MI, Catalan-Dibene J, Zlotnik A. B cells responses and cytokine production are regulated by their immune microenvironment. Cytokine. 2015;74:318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Avery DT, Bryant VL, Ma CS, de Waal Malefyt R, Tangye SG. IL-21-induced isotype switching to IgG and IgA by human naive B cells is differentially regulated by IL-4. J Immunol. 2008;181:1767–1779. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wren L, et al. Influence of cytokines on HIV-specific antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity activation profile of natural killer cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e38580. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brezski RJ, Jordan RE. Cleavage of IgGs by proteases associated with invasive diseases: an evasion tactic against host immunity? MAbs. 2010;2:212–220. doi: 10.4161/mabs.2.3.11780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pillay T, et al. Semen IgM, IgG1, and IgG3 differentially associate with pro-inflammatory cytokines in HIV-infected men. Front Immunol. 2018;9:3141. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.03141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mansoor LE, et al. Integrated provision of topical pre-exposure prophylaxis in routine family planning services in South Africa: a non-inferiority randomized controlled trial. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22:e25381. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdool Karim Q, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science. 2010;329:1168–1174. doi: 10.1126/science.1193748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bebell LM, et al. Relationship between levels of inflammatory cytokines in the genital tract and CD4+ cell counts in women with acute HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:710–714. doi: 10.1086/590503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stramer SL, et al. Markers of HIV infection prior to IgG antibody seropositivity. JAMA. 1989;262:64–69. doi: 10.1001/jama.1989.03430010076034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Devito C, et al. Human IgM monoclonal antibodies block HIV-transmission to immune cells in cervico-vaginal tissues and across polarized epithelial cells in vitro. Sci Rep. 2018;8:10180. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28242-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lobo PI, et al. Naturally occurring IgM anti-leukocyte autoantibodies (IgM-ALA) inhibit T cell activation and chemotaxis. J Immunol. 2008;180:1780–1791. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lobo PI, et al. Natural IgM anti-leukocyte autoantibodies attenuate excess inflammation mediated by innate and adaptive immune mechanisms involving Th-17. J Immunol. 2012;188:1675–1685. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lobo PI, Schlegel KH, Yuan W, Townsend GC, White JA. Inhibition of HIV-1 infectivity through an innate mechanism involving naturally occurring IgM anti-leukocyte autoantibodies. J Immunol. 2008;180:1769–1779. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chung AW, et al. Viral control in chronic HIV-1 subtype C infection is associated with enrichment of p24 IgG1 with Fc effector activity. AIDS. 2018;32:1207–1217. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li L, Liu Y, Gorny MK. Association of diverse genotypes and phenotypes of immune cells and immunoglobulins with the course of HIV-1 infection. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2735. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Archary D, et al. Distinct genital tract HIV-specific antibody profiles associated with tenofovir gel. Mucosal Immunol. 2016;9:821–833. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gronwall C, Silverman GJ. Natural IgM: beneficial autoantibodies for the control of inflammatory and autoimmune disease. J Clin Immunol. 2014;34(Suppl 1):S12–21. doi: 10.1007/s10875-014-0025-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kawano Y, Noma T, Kou K, Yoshizawa I, Yata J. Regulation of human IgG subclass production by cytokines: human IgG subclass production enhanced differentially by interleukin-6. Immunology. 1995;84:278–284. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawano Y, Noma T, Yata J. Regulation of human IgG subclass production by cytokines. IFN-gamma and IL-6 act antagonistically in the induction of human IgG1 but additively in the induction of IgG2. J Immunol. 1994;153:4948–4958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Plomp R, et al. Subclass-specific IgG glycosylation is associated with markers of inflammation and metabolic health. Sci Rep. 2017;7:12325. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12495-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nesspor TC, Raju TS, Chin CN, Vafa O, Brezski RJ. Avidity confers FcgammaR binding and immune effector function to aglycosylated immunoglobulin G1. J Mol Recognit. 2012;25:147–154. doi: 10.1002/jmr.2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wada R, Matsui M, Kawasaki N. Influence of N-glycosylation on effector functions and thermal stability of glycoengineered IgG1 monoclonal antibody with homogeneous glycoforms. MAbs. 2019;11:350–372. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2018.1551044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tangye SG, Ferguson A, Avery DT, Ma CS, Hodgkin PD. Isotype switching by human B cells is division-associated and regulated by cytokines. J Immunol. 2002;169:4298–4306. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Punnonen J, de Vries JE. IL-13 induces proliferation, Ig isotype switching, and Ig synthesis by immature human fetal B cells. J Immunol. 1994;152:1094–1102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jeannin P, Delneste Y, Lecoanet-Henchoz S, Gretener D, Bonnefoy JY. Interleukin-7 (IL-7) enhances class switching to IgE and IgG4 in the presence of T cells via IL-9 and sCD23. Blood. 1998;91:1355–1361. doi: 10.1182/blood.V91.4.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kutteh WH, Moldoveanu Z, Mestecky J. Mucosal immunity in the female reproductive tract: correlation of immunoglobulins, cytokines, and reproductive hormones in human cervical mucus around the time of ovulation. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1998;14(Suppl 1):S51–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lu FX, et al. Immunoglobulin concentrations and antigen-specific antibody levels in cervicovaginal lavages of rhesus macaques are influenced by the stage of the menstrual cycle. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6321–6328. doi: 10.1128/IAI.67.12.6321-6328.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Francis SC, et al. Immune activation in the female genital tract: expression profiles of soluble proteins in women at high risk for HIV infection. PLOS ONE. 2016;11:e0143109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anahtar MN, et al. Cervicovaginal bacteria are a major modulator of host inflammatory responses in the female genital tract. Immunity. 2015;42:965–976. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Masson L, et al. Inflammatory cytokine biomarkers to identify women with asymptomatic sexually transmitted infections and bacterial vaginosis who are at high risk of HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect. 2016;92:186–193. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2015-052072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mlisana K, et al. Symptomatic vaginal discharge is a poor predictor of sexually transmitted infections and genital tract inflammation in high-risk women in South Africa. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:6–14. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kawasaki T, Kawai T. Toll-like receptor signalling pathways. Front Immunol. 2014;5:461. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:373–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chan JM, Dillard JP. Attention seeker: production, modification, and release of inflammatory peptidoglycan fragments in Neisseria species. J Bacteriol. 2017;199:e00354–17. doi: 10.1128/jb.00354-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stevens JS, Criss AK. Pathogenesis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the female reproductive tract: neutrophilic host response, sustained infection, and clinical sequelae. Curr Opin Hematol. 2018;25:13–21. doi: 10.1097/moh.0000000000000394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.