Abstract

Background:

Previous research demonstrated an increase in the reporting of schizophrenia diagnoses among nursing home (NH) residents after the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care. Given known health and healthcare disparities among Black NH residents, we examined how race and Alzheimer’s and related dementia (ADRD) status influenced the rate of schizophrenia diagnoses among NH residents following the partnership.

Methods:

We used a quasi-experimental difference-in-differences design to study the quarterly prevalence of schizophrenia among US long-stay NH residents aged 65 years and older, by Black race and ADRD status. Using 2011–2015 Minimum Data Set 3.0 assessments, our analysis controlled for age, sex, measures of function and frailty (activities of daily living [ADL] and Changes in Health, End-stage disease and Symptoms and Signs scores) and behavioral expressions.

Results:

There were over 1.2 million older long-stay NH residents, annually. Schizophrenia diagnoses were highest among residents with ADRD. Among residents without ADRD, Black residents had higher rates of schizophrenia diagnoses compared to their nonblack counterparts prior to the partnership. Following the partnership, Black residents with ADRD had a significant increase of 1.7% in schizophrenia as compared to nonblack residents with ADRD who had a decrease of 1.7% (p = 0.007).

Conclusions:

Following the partnership, Black NH residents with ADRD were more likely to have a schizophrenia diagnosis documented on their MDS assessments, and schizophrenia rates increased for Black NH residents with ADRD only. Further work is needed to examine the impact of “colorblind” policies such as the partnership and to determine if schizophrenia diagnoses are appropriately applied in NH practice, particularly for black Americans with ADRD.

Keywords: ADRD, dementia quality of care, nursing home, racial disparities, schizophrenia

INTRODUCTION

Racial and ethnic disparities in the quality of care across nursing homes (NHs) have been well documented.1 Black NH residents are more likely to reside in lower quality2 and extremely segregated NHs as compared to their White counterparts.3 Compared to White NH residents, Black NH residents also have a higher risk of receiving antipsychotics and are more likely to be physically restrained, have a catheter, and use feeding tubes.4,5 Furthermore, when compared to White residents, Black residents are less likely to receive vaccines or have their pain treated appropriately.6–8 With higher rates of comorbidities, including Alzheimer’s and related dementias (ADRD) and the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, Black residents experience greater vulnerability to poorer health outcomes as compared to their White counterparts.9,10

Race is socially constructed, and, therefore, the observed health(care) racial disparities do not result from biological processes; on the contrary, the fundamental cause may be racism.11,12 Structural and institutional racism are oftentimes legalized systems of policies, practices, and norms that inherently lead to an uneven distribution of power and resources. This uneven distribution of resources advantages White populations, while disadvantaging Black populations and other populations of color.13 Historically, overt racism such as the Jim Crow laws and residential segregation through the use of redlining were the most prevalent forms of racism. Nowadays, scholars argue that one new form of racism is “colorblind racism.”14 Colorblind racism can be depicted through the creation of long-term care policies that do not account for the potential unintended consequences that these policies may have on older adults of color. Crafting new policies and failing to acknowledge the historic structures that have disadvantaged Black NH residents may result in the new policies, further disadvantaging the most vulnerable communities. Long-term care researchers have raised concern that some major quality improvement initiatives have had the unintended consequences of exacerbating disparities within the long-term care setting.15

In March 2012, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) implemented an initiative to improve quality across NHs and for residents with ADRD, known as the National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes (hereafter, partnership). The partnership was a federal response to the continued potentially inappropriate use of antipsychotics in NHs that intentionally directed facilities toward nonpharmacologic, person-centered care.16,17 Antipsychotics have been potentially used inappropriately in NHs to treat residents with the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia associated with ADRD, despite a lack of proven efficacy and two Food and Drug Administration Black Box Warnings issued against such antipsychotic use.18–20 In the calculation of the quality measure used by the partnership, NH residents with specific conditions (schizophrenia, Tourette’s, or Huntington’s) are expressly excluded, exposing a possible unintentional outcome: an increase in the reporting of the exclusionary conditions. While potentially inappropriate antipsychotic use has continued to decline,17,21,22 the partnership may have unintentionally contributed to an increase in schizophrenia diagnoses.23

Winter et al. found that schizophrenia diagnoses nearly doubled between 2011 and 2013 for long-stay NH residents enrolled in Virginia Medicaid.23 These researchers posited that as much as 20% of the reduction in potentially inappropriate antipsychotics could have been explained by increased reporting of exclusionary diagnoses, for example, schizophrenia, rather than true reduction in medication use.23 In fact, a qualitative study reported that following the partnership physicians changed their documentation practices to match approved indications for antipsychotic use.24 For the purpose of this article, it was important to understand if racial disparities existed within schizophrenia diagnoses following the partnership.

Our study examined the CMS National Partnership as a “colorblind” policy to assess if there was a possible unintended consequence for Black NH residents with respect to schizophrenia diagnoses. The purpose of this work was to examine the possible effects of the partnership on the rate of schizophrenia diagnoses among long-stay NH residents while considering the intersections between ADRD and Black race. We hypothesized that following the partnership, Black NH residents would experience greater increases in schizophrenia diagnoses as compared to their nonblack counterparts, and residents with ADRD would have higher rates of schizophrenia.

STUDY DATA AND METHODS

Data

Using 2011–2015 Minimum Data Set (MDS) 3.0 resident assessment and care screening data, we conducted our analyses using all quarterly and/or yearly assessments.

Sample

We used the quarterly and yearly MDS assessments to identify long-stay residents aged 65 years and older. In each year, we analyzed about 4 million assessments from approximately 1.2 million long-stay NH residents across 15,804 NHs.

Dependent variables

The main outcome variable was the presence of schizophrenia as an MDS-based active diagnosis (I6000). An MDS-based active diagnosis requires a physician-documented diagnosis within the last 60 days along with a direct effect on the patient’s functional status within the last 7 days.

Independent variables

The key independent variables of interest were Black race and the presence of ADRD. The MDS variable for race (A1000) is a dichotomous variable that indicates whether or not an individual is identified as Black or nonblack. Residents with ADRD were identified using the MDS active diagnosis codes.

Control variables

We included several covariates to account for NH resident age, sex, functional and frailty status, and behavioral expressions of dementia. As a measure of functional status, we used the Activities of Daily Living (ADL) scale score. The ADL score was created by summing seven individual ADL items on a scale from 0–4 (with 0 = complete independence and 4 = total dependence for each item) and ranged from 0–28.25 To measure frailty, we used the Changes in Health, End-stage disease and Symptoms and Signs (CHESS) score variable that ranges from 0 (most stable) to 5 (least stable) and is a strong predictor of long-stay resident mortality at 30 days, 60 days, and 1 year.26 CHESS includes measures that consistently predict death in NHs including clinical signs and symptoms, comorbid conditions, ADL dependency, and cognitive decline and related behaviors. Lastly, to measure the behavioral expressions of dementia, we use the Agitated and Reactive Behavior Scale (ARBS) to evaluate resident agitation and resistance to care.27 The ARBS score ranges from 0 to 12, where 0 represents no behaviors and 12 represents severe behaviors.

Statistical analysis

We examined changes in schizophrenia diagnoses among NH residents from 2011–2015 using a quasi-experimental, difference-in-differences study design. We tested the possible effect of the partnership initiative introduction in March 2012 on schizophrenia diagnoses using difference-in-difference regression analyses. Our analysis included 6 quarters of data prior to the initiative and 14 quarters post. We accounted for repeated measures with individual- and facility-fixed effects and clustered standard errors. In order to conduct the difference-in-difference analysis, we conducted a parallel trends analysis, which confirmed the trends were parallel prior to our intervention quarter, which makes the application of this method appropriate. Our analysis used a triple interaction term to compare Black and nonblack residents with and without ADRD indications, before and after the partnership. To test the robustness of our results, we conducted several sensitivity analyses. Specifically, we compared Black and White residents (excluding other racial/ethnic groups), and we also conducted a falsification test in which we estimated the prevalence of a diabetes diagnosis as a dependent variable. We hypothesized that diabetes diagnoses would not be affected by the partnership, and any relationships observed could be evidence of endogeneity unaccounted for in our models. Statistical analyses for this study were conducted using STATA 14 statistical software package.28

RESULTS

Over the study period, the percent of resident assessments with a schizophrenia diagnosis increased by 1.1 percentage points (Table 1). The average age of long-stay residents over 65 remained approximately 83 years of age across time, the percent of males increased slightly, and the percent of assessments with Black race increased slightly. Over the study period, the mean ADL score remained consistent, as did the CHESS score. The presence of ADRD decreased slightly from 63.3% to 62.6% across the study period while behavioral expressions of dementia as measured by the ARBS decreased from a score of 0.5 to 0.4.

TABLE 1.

Demographic changes over time for nursing home residents

| Year | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessments, n | 3,960,600 | 3,950,871 | 3,890,268 | 3,910,761 | 3,846,368 |

| Residents, n | 1,272,958 | 1,260,554 | 1,239,831 | 1,237,807 | 1,223,290 |

| Schizophrenia, % | 4.9% | 5.1% | 5.4% | 5.6% | 6.0% |

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 83.8 (8.5) | 83.7 (8.6) | 83.6 (8.7) | 83.5 (8.8) | 83.3 (8.9) |

| Sex, % | |||||

| Female | 73.0 | 72.5 | 72.0 | 71.4 | 70.9 |

| Race, % | |||||

| Black | 12.1 | 12.2 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 12.8 |

| Health-related characteristics | |||||

| ADL Scale Score, mean (SD) | 16.9 (7.5) | 17.1 (7.2) | 17.1 (7.0) | 17.1 (6.8) | 17.1 (6.6) |

| CHESS Scale Score, mean (SD) | 0.8 (1.0) | 0.8 (0.9) | 0.8 (0.9) | 0.8 (0.9) | 0.7 (0.9) |

| ADRD, % | 63.3 | 63.8 | 63.6 | 63.4 | 62.6 |

| Agitated and Reactive Behavior Scale Score, mean (SD) | 0.5 (1.3) | 0.5 (1.3) | 0.5 (1.2) | 0.4 (1.2) | 0.4 (1.1) |

Note: SD, standard deviation. ADL, activities of daily living: A scale score ranging from 0, complete independence to 5, total dependence, created by summing seven ADL items on a scale from 0–4 (with 0 = complete independence and 4 = total dependence for each item).25 CHESS, Changes in Health, End-stage disease and Symptoms and Signs: A predictive scale score ranges from 0, most stable to 5, or least stable.26 To measure the behavioral expressions of dementia, we use the Agitated and Reactive Behavior Scale (ARBS) to evaluate resident agitation and resistance to care.27 The ARBS score ranges from 0 to 12, where 0 represents no behaviors and 12 represents severe behaviors.

There were significant differences in schizophrenia diagnoses by ADRD status and race (Table 2). In the unadjusted model, there was a smaller increase in schizophrenia diagnoses among the assessments without an ADRD diagnosis as compared to those with ADRD diagnoses, but the racial disparity was greater within the sample with ADRD. Before the partnership, 5.7% of the nonblack resident assessments without ADRD diagnoses and 9.3% of the Black resident assessments without ADRD diagnoses had a schizophrenia diagnosis. Following the partnership, 6.1% of nonblack and 10% of Black resident assessments without ADRD had schizophrenia diagnoses. These changes over time represented a 7% and a 7.5% relative increase in schizophrenia diagnoses for the nonblack and Black resident assessments, respectively. Furthermore, among resident assessments with an ADRD diagnosis, the changes over time represented a 15.8% increase in schizophrenia diagnoses for nonblack residents and a 15.6% increase for Black residents (p < 0.001). Among the group without ADRD, Black residents had a 0.5 percentage points (pp) greater increase in schizophrenia and the Black–nonblack gap increased by 0.3 pp, from 3.6 pp in the pre-period to 3.9 pp in the post-period. Among the group with ADRD, Black residents had a 0.2 pp lower increase in schizophrenia, and the Black–nonblack gap increased by 0.6 pp, from 3.9 pp in the pre-period to 4.5 pp in the post-period.

TABLE 2.

Difference-in-differences regressions with individual- and nursing home–fixed effects to predict schizophrenia reporting among nursing home residents with and without ADRD documentation, pre- and post-partnership, by race Unadjusted (N = 18,944,587)

| Pre-partnership | post-partnership | Relative change | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted (N = 18,944,587) | ||||

| Without ADRD | <0.001 | |||

| Nonblack residents | 5.7% | 6.1% | 7.0% | |

| Black residents | 9.3% | 10.0% | 7.5% | |

| With ADRD | ||||

| Nonblack residents | 3.8% | 4.4% | 15.8% | |

| Black residents | 7.7% | 8.9% | 15.6% | |

| Adjusted (N = 18,749,050) | ||||

| Without ADRD | 0.007 | |||

| Nonblack residents | 5.3% | 5.2% | 1.9% | |

| Black residents | 5.0% | 4.9% | 2.0% | |

| With ADRD | ||||

| Nonblack residents | 5.8% | 5.7% | 1.7% | |

| Black residents | 5.8% | 5.9% | 1.7% |

Note: The fully adjusted model adjusts for age, gender, CHESS, ADL, and behavioral expressions of dementia. ADRD, Alzheimer’s and related dementias. ADL, activities of daily living: A scale score ranging from 0, complete independence to 5, total dependence, created by summing seven ADL items on a scale from 0–4 (with 0 = complete independence and 4 = total dependence for each item).25 CHESS, Changes in Health, End-stage disease and Symptoms and Signs: A predictive scale score ranges from 0, most stable to 5, or least stable.26 To measure the behavioral expressions of dementia, we use the Agitated and Reactive Behavior Scale (ARBS) to evaluate resident agitation and resistance to care. We estimated a difference-in-differences regression model with a triple interaction for race, dementia, and the postpartnership period and present the p-value from the triple interaction coefficient. Pre- and postpartnership predicted values were obtained using predictive margins following the estimation of the model.

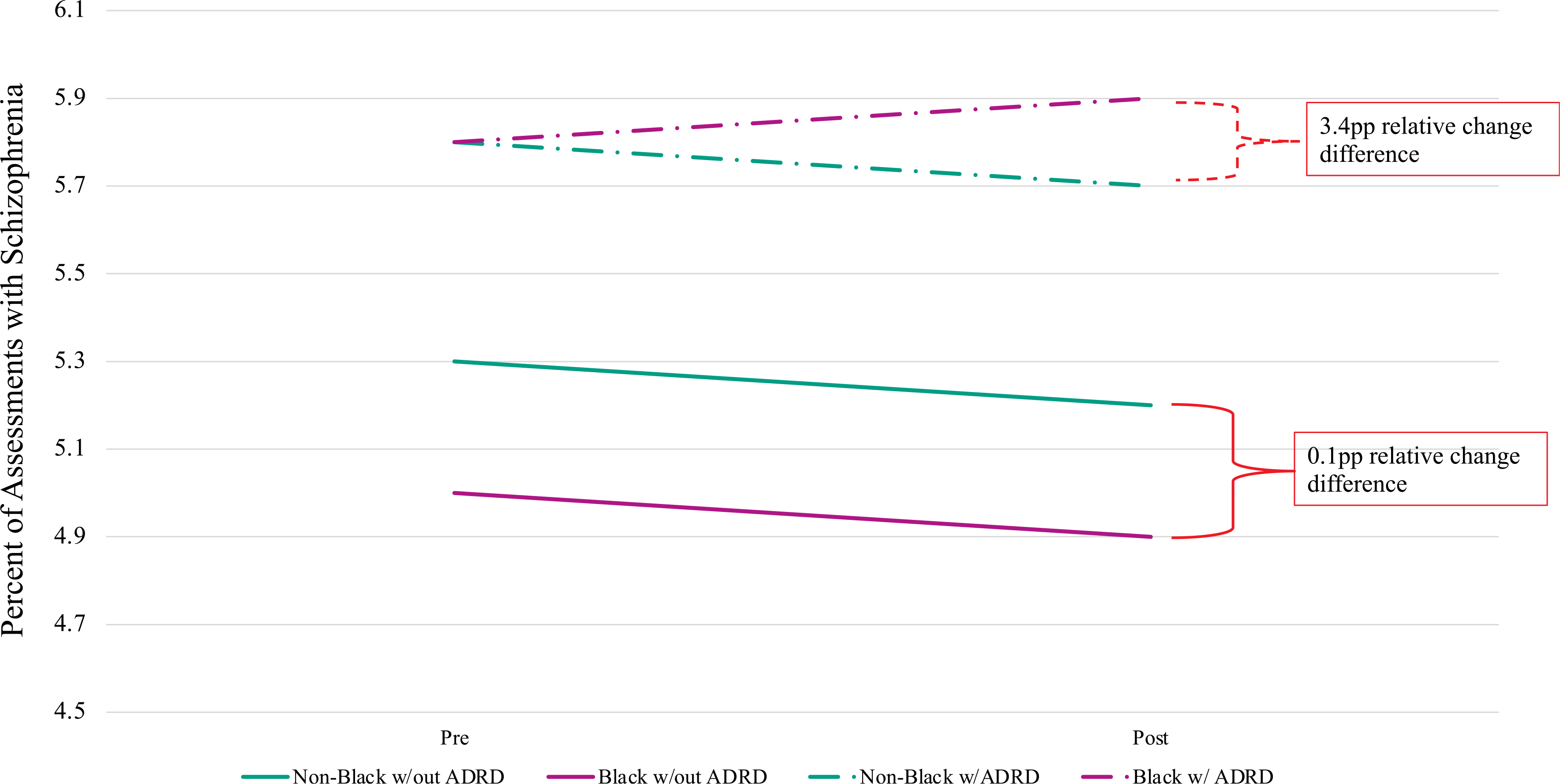

In the fully adjusted model, the magnitude of the change in schizophrenia diagnoses was smaller as compared to the unadjusted model but significant (p = 0.007) (Table 2 and Figure 1). In the population without ADRD diagnoses, the relative change (decrease) in schizophrenia diagnoses was −1.9% for the nonblack resident assessments and −2.0% for the Black resident assessments. Among resident assessments with ADRD, nonblack residents had a 1.7% decline in schizophrenia diagnoses, while Black residents had a 1.7% increase in schizophrenia. The difference between the changes in schizophrenia diagnoses for nonblack and Black resident assessments with ADRD is 3.4 pp, and the Black–nonblack gap increased by 0.2 pp, from no gap in pre-period rates of schizophrenia to a gap of 0.2 pp after the initiative. All sensitivity analysis results can be found in Tables S1–S3. All the observed trends hold when excluding other racial/ethnic groups and only comparing Black and White residents. Furthermore, we did not observe differential changes in documentation of diabetes as we did in the presence of a schizophrenia diagnosis.

FIGURE 1.

Difference-in-difference regressions with individual- and nursing home–fixed effects to predict schizophrenia reporting among nursing home residents with and without ADRD documentation, pre- and post-partnership, by race. This figure is a visual representation of the fully adjusted model in Table 2. The fully adjusted model adjusts for age, gender, CHESS, ADL, and behavioral expressions of dementia. ADRD, Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. ADL, activities of daily living: A scale score ranging from 0, complete independence to 5, total dependence, created by summing seven ADL items on a scale from 0–4 (with 0 = complete independence and 4 = total dependence for each item).25 CHESS, Changes in Health, End-stage disease and Symptoms and Signs: A predictive scale score ranges from 0, most stable to 5, or least stable.26 To measure the behavioral expressions of dementia, we use the Agitated and Reactive Behavior Scale (ARBS) to evaluate resident agitation and resistance to care.27 The ARBS score ranges from 0 to 12, where 0 represents no behaviors and 12 represents severe behaviors. We estimated a difference-in-differences regression model with a triple interaction for race, dementia, and the postpartnership period and present the p-value from the triple interaction coefficient. Pre- and postpartnership predicted values were obtained using predictive margins following the estimation of the model

DISCUSSION

We examined the possible unintended impact of the CMS National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care on the presence of schizophrenia diagnoses among Black and nonblack NH residents. Black NH residents with ADRD were more likely to have schizophrenia documented on their MDS assessments as compared to their nonblack counterparts. Following the partnership, schizophrenia reporting rates increased more for Black NH residents with ADRD than their nonblack peers and those without ADRD. The difference in relative change between Black NH residents and nonblack residents was greatest for those with an ADRD diagnosis.

The partnership specifically called for a reduction in antipsychotic medication use among NH residents with ADRD after studies established higher adverse risks for older adults with dementia.29 Understanding how schizophrenia diagnoses have changed relative to the CMS National Partnership has important implications for how we ultimately measure the trend in inappropriate antipsychotic use. Initial reports assessing the Partnership’s impact suggest that NHs were increasingly reporting schizophrenia diagnoses among residents, potentially as a means to skirt the intent of the initiative (curtail antipsychotic use) and allow NH staff to manage “challenging” behaviors with antipsychotic medications under the guise of schizophrenia.23,24 According to our analyses, schizophrenia diagnoses documented in the MDS significantly increased after the Partnership, which may be clinically meaningful in some facilities, but clinical significance/meaningfulness is an issue for further study. Our findings were congruent with past studies,23 in part, and suggest that either schizophrenia prevalence was increasing in the NH22,30 or providers were increasing their documentation of schizophrenia24 but disproportionately for Black NH residents with ADRD as compared to all other NH residents. Further work is needed to validate the latter suggested findings and to link schizophrenia to appropriate psychiatric evaluation, especially for Black NH residents with ADRD.

The inequitable increase in schizophrenia among Black residents with ADRD could reflect racial disparities in schizophrenia diagnoses, differences in quality of care among Black versus nonblack NH residents, staff perceptions of how to manage challenging behaviors, or structural racism manifesting through the potential unintended consequences of a colorblind policy such as the Partnership, as discussed in the introduction. Consistent with our unadjusted analysis, prior research has established that Black NH residents have higher rates of schizophrenia in the MDS as compared to other NH residents30; however, when adjusting for demographics, function, and frailty, we only observe an increase in schizophrenia for Black residents with ADRD. Research shows that Black older adults are more likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia than White older adults, even when such a diagnosis is not justified for various reasons.31 In addition, with behavioral expressions of dementia being more common in Black NH residents,9,10 NHs may be using schizophrenia labeling to allow them to use antipsychotics to manage Black residents with neuropsychiatric symptoms. Congruently, Black NH residents have historically had higher rates of antipsychotic use than other residents4,5; however, more recent rates of antipsychotic use have not been examined by race (i.e., racial differences in antipsychotic prevalence following the Partnership). Further analyses are needed to better articulate the mechanism(s) for the emerging disparity in schizophrenia reporting. Future work should look at the initial diagnoses of schizophrenia to determine if it occurs during or prior to the NH stay and observe if these trends differ based on antipsychotic use. Furthermore, Black NH residents are more likely to receive care in lower quality NHs,2 and although we controlled for the facility, differing quality of care across facilities may be contributing to differential labeling.32

There are some limitations of our study to note. There are inherent variations and limitations when using assessment data. NH staff complete the MDS assessments that serve as the source of data for schizophrenia and ADRD documentation. They are expected to review residents’ medical records to determine whether the diagnoses have direct relationships with the resident’s current status. We assume that NH staff have valid information on both schizophrenia and ADRD, both of which could be misclassified. For this reason, it may be more appropriate to use the terms “report,” “document,” or “label,” recognizing that the “diagnoses” reported in the MDS may be true diagnoses or they may be labels. This distinction is a matter for further study. We also recognize that our study only compares Black residents to “nonblack” residents, that the reporting or race may be inaccurate and that the grouping “nonblack” residents ignores variation within the group. Future work should disaggregate the “nonblack” group; however, better data will be required as the MDS A1000 race variable does a poor job of identifying nonblack and nonwhite racial/ethnic groups.33 Lastly, this study does not consider Huntington’s disease or Tourette syndrome; however, the percent of residents with either conditions reported was extremely small (<1%) in our study as well as others.23

CONCLUSION

In the early years following the partnership, Black NH residents with ADRD were more likely to have schizophrenia documented on their MDS assessments. Further work is needed to determine if schizophrenia diagnoses are appropriately employed in NH practice, particularly for Black residents with ADRD indications. As proposed in the introduction of this study, these disparities may be a direct result of structural racism as a fundamental cause of disparities.11,15 Our findings illustrate the need for more work to understand the impact of colorblind policies and for policy analyses that examine the impact of reforms while stratifying by race and other intersections. For research, policy, and practices that focus on older adults with ADRD, this study highlights the need for an intersectional lens that examines how ADRD status interacts with race in terms of quality, access, and outcomes in long-term care settings.34 As suggested by this work, policies have the potential to impart disparate impacts by race and ADRD status. More work needs to be done to create a method that adjusts for the potential increased coding of schizophrenia while measuring changes in antipsychotic use to evaluate the impact of the Partnership. Future work should also consider the impact of the public reporting, for example, star ratings for antipsychotic use, that followed this Partnership.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Difference-in-differences regressions with individual and nursing home-fixed effects to predict schizophrenia reporting among nursing home residents with and without ADRD documentation, pre- and post-partnership, by White and Black race only.

Table S2. Difference-in-differences regressions with individual and nursing home-fixed effects to predict schizophrenia reporting among nursing home residents with and without ADRD documentation, pre- and post-partnership, by Hispanic ethnicity.

Table S3. Difference-in-differences regressions with individual and nursing home-fixed effects to predict diabetes reporting among nursing home residents with and without ADRD documentation, pre- and post-partnership, by race.

Key Points.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) National Partnership was associated with increases in schizophrenia diagnoses, especially among Black nursing home residents with dementia.

Why Does this Paper Matter?

Nursing home regulatory initiatives may have unintended consequences for the most vulnerable nursing home residents.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The corresponding author affirms that they have listed everyone who has contributed significantly.

Funding information

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Grant/Award Number: 4T32 HS000011; National Institute on Aging, Grant/Award Number: 2P01AG027296-11; Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service, Grant/Award Number: CDA 14-422

SPONSOR’S ROLE

The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Authors Shekinah Fashaw-Walters, Ellen McCreedy, Julie P. W. Bynum, Kali Thomas, and Theresa I. Shireman have no potential conflicts of interest to declare.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of the article at the publisher’s website.

REFERENCES

- 1.Konetzka RT, Werner RM. Review: disparities in long-term care. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(5):491–521. 10.1177/1077558709331813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mor V, Zinn J, Angelelli J, Teno JM, Miller SC. Driven to tiers: socioeconomic and racial disparities in the quality of nursing home care. Milbank Q. 2004;82(2):227–256. 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00309.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahman M, Foster AD. Racial segregation and quality of care disparity in US nursing homes. J Health Econ. 2015;39:1–16. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller SC, Papandonatos G, Fennell M, Mor V. Facility and county effects on racial differences in nursing home quality indicators. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(12):3046–3059. 10.1016/J.SOCSCIMED.2006.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grabowski DC, McGuire TG. Black-white disparities in care in nursing homes. Atl Econ J. 2009;37(3):299–314. 10.1007/s11293-009-9185-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cai S, Feng Z, Fennell ML, Mor V. Despite small improvement, black nursing home residents remain less likely than whites to receive flu vaccine. Health Aff. 2011;30(10):1939–1946. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo H, Zhang X, Cook B, Wu B, Wilson MR. Racial/ethnic disparities in preventive care practice among U.S. Nursing home residents. J Aging Health. 2014;26(4):519–539. 10.1177/0898264314524436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunnicutt JN, Ulbricht CM, Tjia J, Lapane KL. Pain and pharmacologic pain management in long-stay nursing home residents. Pain. 2017;158(6):1091–1099. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnes LL, Bennett DA. Alzheimer’s disease in African Americans: risk factors and challenges for the future. Health Aff(Millwood). 2014;33(4):580–586. 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sink KM, Covinsky KE, Newcomer R, Yaffe K. Ethnic differences in the prevalence and pattern of dementia-related behaviors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(8):1277–1283. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52356.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phelan JC, Link BG. Is racism a fundamental cause of inequalities in health? Annu Rev Sociol. 2015;41:311–330. 10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gee GC, Ford CL. Structural racism and health inequities: old issues, new directions. Du Bois Rev. 2011;8(1):115–132. 10.1017/S1742058X11000130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1212–1215. 10.2105/AJPH.90.8.1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonilla-Silva E The structure of racism in color-blind, “post-racial” America. Am Behav Sci. 2015;59(11):1358–1376. 10.1177/0002764215586826 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Konetzka RT, Werner RM. Disparities in long-term care: building equity into market-based reforms. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(5):491–521. 10.1177/1077558709331813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.CMS Announces Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes j CMS. Published 2012. Accessed May 27, 2019. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-announces-partnership-improve-dementia-care-nursing-homes

- 17.Lucas JA, Bowblis JR. CMS strategies to reduce antipsychotic drug use in nursing home patients with dementia show some progress. Health Aff. 2017;36(7):1299–1308. 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maher AR, Maglione M, Bagley S, et al. Efficacy and comparative effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic medications for off-label uses in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2011;306(12):1359–1369. 10.1001/jama.2011.1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia. JAMA. 2005; 294(15):1934–1943. 10.1001/jama.294.15.1934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sink KM, Holden KF, Yaffe K. Pharmacological treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. JAMA. 2005;293(5): 596–608. 10.1001/jama.293.5.596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bowblis JR, Lucas JA, Brunt CS. The effects of antipsychotic quality reporting on antipsychotic and psychoactive medication use. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(4):1069–1087. 10.1111/1475-6773.12281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fashaw SA, Thomas KS, McCreedy E, Mor V. Thirty-year trends in nursing home composition and quality since the passage of the Omnibus Reconciliation Act. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;21:233–239. 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winter JD, Kerns JW, Winter KM, Sabo RT. Increased reporting of exclusionary diagnoses inflate apparent reductions in long-stay antipsychotic prescribing. Clin Gerontol. 2017;42:1–5. 10.1080/07317115.2017.1395378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kerns JW, Winter JD, Winter KM, Boyd T, Etz RS. Primary care physician perspectives about antipsychotics and other medications for symptoms of dementia. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(1):9–21. 10.3122/jabfm.2018.01.170230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wysocki A, Thomas KS, Mor V. Functional improvement among short-stay nursing home residents in the MDS 3.0. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(6):470–474. 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogarek JA, McCreedy EM, Thomas KS, Teno JM, Gozalo PL. Minimum data set changes in health, end-stage disease and symptoms and signs scale: a revised measure to predict mortality in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(5): 976–981. 10.1111/jgs.15305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCreedy E, Ogarek JA, Thomas KS, Mor V. The minimum data set agitated and reactive behavior scale: measuring behaviors in nursing home residents with dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(12):1548–1552. 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.08.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP. Published 2015. Accessed November 30, 2018. https://www.stata.com/support/faqs/resources/citing-software-documentation-faqs/ [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steinberg M, Lyketsos CG. Atypical antipsychotic use in patients with dementia: managing safety concerns. Am J Psychiatry. 2012; 169(9):900–906. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12030342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fullerton CA, McGuire T, Feng Z, Mor V, Grabowski D. Trends in mental health admissions to nursing homes, 1999–2005. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(7):965–971. 10.1176/appi.ps.60.7.965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwartz RC. Racial disparities in psychotic disorder diagnosis: a review of empirical literature. World J Psychiatry. 2014;4(4): 133–140. 10.5498/wjp.v4.i4.133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Y, Cai X, Cram P. Are patients with serious mental illness more likely to be admitted to nursing homes with more deficiencies in care? Med Care. 2011;49(4):397–405. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318202ac10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jarrín OF, Nyandege AN, Grafova IB, Dong X, Lin H. Validity of race and ethnicity codes in Medicare administrative data compared with gold-standard self-reported race collected during routine home health care visits. Med Care. 2020;58(1):E1–E8. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bowleg L The problem with the phrase women and minorities: intersectionality-an important theoretical framework for public health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1267–1273. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Difference-in-differences regressions with individual and nursing home-fixed effects to predict schizophrenia reporting among nursing home residents with and without ADRD documentation, pre- and post-partnership, by White and Black race only.

Table S2. Difference-in-differences regressions with individual and nursing home-fixed effects to predict schizophrenia reporting among nursing home residents with and without ADRD documentation, pre- and post-partnership, by Hispanic ethnicity.

Table S3. Difference-in-differences regressions with individual and nursing home-fixed effects to predict diabetes reporting among nursing home residents with and without ADRD documentation, pre- and post-partnership, by race.