Abstract

Background:

Evidence-based interventions addressing loneliness and social isolation are needed, including among low-income, community-dwelling older adults of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. Our objective was to assess the effect of a peer intervention in addressing loneliness, isolation, and behavioral health needs in this population.

Methods:

We conducted a mixed-methods, two-year longitudinal study of a peer-outreach intervention in 74 low-income older adults recruited via an urban senior center in San Francisco. Structured participant surveys were conducted at baseline and every 6 months for up to 2 years. Outcomes included loneliness (3-item UCLA loneliness scale), social interaction (10-item Duke index), self-perceived socializing barriers (Range: 0-10), and depression (PHQ-2 screen). Data were analyzed using mixed-effects linear and logistic regression adjusted for age and gender. Qualitative, semi-structured interviews with participants (n=15) and peers (n=6) were conducted in English and Spanish and analyzed thematically.

Results:

Participants were on average 71 years old (Range: 59-96 years), with 58% male, 15% LGBT, 18% African American, 19% Latinx, 8% Asian, 86% living alone, and 36% with an ADL impairment. On average, 43 contact visits (IQR: 31-97 visits) between participants and peers occurred over the first year. Loneliness scores decreased by, on average, 0.8 points over 24 months (p=0.015). Participants reported reduced depression (38% to 16%, p<0.001) and fewer barriers to socializing (1.5 fewer, p<0.001). Because of the longitudinal relationship and matching of characteristics of peers to participants, participants reported strong feelings of kinship, motivations to reach out in other areas of life, and improved mood.

Conclusion:

Diverse older adults in an urban setting participating in a longitudinal peer program experienced reduced loneliness, depression, and barriers to socializing. Matching by shared backgrounds facilitated rapport and bonding between participants and peers.

Keywords: Loneliness, Social Isolation, LGBT, Peer, older adults, low-income

INTRODUCTION

Loneliness and social isolation among older adults are associated with higher rates of depression and elder suicide,1 acute health care use,2 loss of independence,3 and an elevated risk of mortality.4, 5 Following a 2016 report estimating that 10-20% of all San Francisco seniors are at risk for “objective” social isolation and “subjective” feelings of loneliness,6 the San Francisco Department of Aging and Adult Services (DAAS) designated these conditions as a high public health priority.7 Despite growing interest in addressing these social risk factors, a 2020 National Academy of Sciences (NAS) report found weak evidence for interventions in general, and even weaker evidence among under-represented and low-income communities.8, 9 Consequently, a core recommendation from the NAS report was to develop partnerships between health care systems and community-based programs to support practical, real-world interventions leveraging local resources and expertise.8

Peer outreach is a potential strategy to address loneliness and social isolation, and involves matching a peer and a client by age and shared experiences to establish a supportive relationship. Peers have successfully supported individuals with depression10 and in cancer survivorship,11 and aided in chronic disease management.12 However, implementing peer outreach among low-income, diverse older adults poses several challenges. Peers may find it difficult to effectively facilitate relationships with older adults who are racially and ethnically dissimilar from themselves. Social needs can be complex, and it is unclear how effective peers might be at addressing multiple barriers that often co-occur (e.g., disability, depression, low finances, and other barriers). Furthermore, it is unclear how to scale a potentially resource-intensive program to efficiently utilize limited community resources.

To address the needs among this priority population in San Francisco, investigators at the University of California, San Francisco partnered with the non-profit Curry Senior Center, located in the socioeconomically and racially/ethnically diverse Tenderloin neighborhood to evaluate the delivery of a peer outreach intervention. Our objectives were to understand the effects of the intervention on the social well-being of participants over a 2-year period, the resources needed to ensure feasibility of the program, and lessons learned on a local level that might inform broader implementation and scale.

METHODS

Participants and Recruitment

Participants were recruited via the non-profit Curry Senior Center affiliated with the San Francisco Department of Public Health (SFDPH) between April of 2015 and August of 2019. Given the known challenges with recruiting lonely or isolated older adults from diverse socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds, recruitment of participants occurred through a “real-world” multi-modal strategy. Strategies included program staff going to locations where seniors gather (e.g. dining halls, senior centers), and presentations to partners (e.g. public health clinics, community centers, building managers of local housing units) who might be aware of isolated older adults confined to their homes. Notably, recruitment by flyer had limited success, and staff stopped using the terms “loneliness” and “social isolation” due to the stigma associated with these terms. The program was instead likened to a friendly visitor program with no formal agenda, where peers might visit, attend social gatherings, run errands, or help connect participants with services if needed. The primary languages spoken by participants included English, Spanish, Mandarin, Cantonese, and Russian.

Participants were given baseline and 6-month interval paper-based follow-up surveys that were returned directly to study coordinators; they received $10 gift cards for each returned survey. Analysis was limited to surveys collected before the start of San Francisco’s March 16, 2020 COVID-19 pandemic shelter-in-place orders, which limited in-person interaction. This analysis includes older adults who participated from a minimum of 6 months up to a 24-month study period (6-months of data: n=74; 12-months: n=58; 24-months: n=20). Reasons for not reaching the full 24-month study period included loss to follow-up (n=22), COVID-19 shelter-in-place orders (n=19), and other documented reasons (n=13) (Supplementary Figure 1).

Peer Recruitment and Training

Peers (n=8) were recruited through local employment agencies and hired as part-time staff through support from the Mental Health Services Act of California and SFDPH which continues to provide annual funding for the program. Peers had shared life experiences with participants in that they were older adults, had histories of isolation, were consumers of the San Francisco Behavioral Health System, were residents of the Tenderloin neighborhood, or had experienced homelessness. During the course of the intervention peers were recruited to match identified needs in the community (e.g., transgender peer, peers fluent in Spanish and Cantonese). The program purposefully utilized an employment model rather than volunteers given the need for consistent contact with participants, the needed time commitment, more ability to recruit peers of shared background to participants, and the higher level of training required to meet the needs of participants.

Each Peer completed a 2-week training program, a mental health certificate program, and monthly trainings on subjects focused on professional development, setting boundaries, wellness, and resilience. Additionally, peers met once a week as a group to discuss outreach challenges, success stories, and coordination of social agendas, and had weekly one-on-one meetings with the program supervisor. This study was determined to be quality improvement by the University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board.

Intervention

At the core of the peer intervention was an intention to cultivate trusting relationships and promote socialization. Peers were matched to participants based on demographics and social interests (e.g, music, food, etc.) and were given flexibility to develop relationships driven by participants’ health needs and social interests. The number of visits was dependent on the participant interest, perceived degree of loneliness, or social isolation. Peers began with a “soft approach” of home visits, providing companionship for simple errands, or connecting individuals to city services (medical or mental health providers, substance use treatment, or housing specialists). As rapport grew, social activities might include shared meals, group activities, art programs, or walks around the city. Peers occasionally arranged larger monthly activities involving multiple participants in cultural events held at the senior center and in other community venues. Completed visits and missed connections (attempted, but unsuccessful contacts) were logged, along with types of activities conducted in each visit.

Psychosocial Measures

Several measures of emotional well-being and social connections were included. First, we measured loneliness using the validated UCLA 3-item loneliness scale (Range: 0-6 points).13 We examined loneliness as a continuous measure and used a cut-off of 3+ points on the scale to identify “high” levels of loneliness.14, 15 Second, we used the validated 10-item Duke Social Support Index (DSSI) to measure social interaction and social support.16, 17 Third, we measured perceived barriers to socializing based on previously recognized barriers to socialization.7 The 10 identified barriers included physical ability, bodily functions (e.g., incontinence), safety, finances, mood, substance use, distance, homelessness, language barriers, or cultural distances. Barriers were summed to create a 10-point scale (Cronbach alpha = 0.62) and examined individually. Fourth, we measured depression using the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) (Range 0-6 points), using 3+ points as a positive screen for depression.18

Demographic and Health Measures

Measured sociodemographic characteristics included self-reported age, sex, sexuality (straight, gay, lesbian, bisexual, other), race/ethnicity, primary language spoken, marital status, living situation (living alone, available housing), and education. Health measures included self-reported medical conditions (depression, anxiety, diabetes, lung disease, heart disease, prior stroke, cancer, or hypertension). Participants were asked about conditions for which they receive disability benefits for (vision, hearing, physical disability, speech, cognition, or health condition). In addition, individuals reported any functional impairment with bathing, dressing, walking, incontinence, eating, and toileting.

Semi-structured Interview Procedures

Curry Senior Center staff identified participants (n=15) and peers (n=6) willing to engage in semi-structured interviews in English or Spanish; willing participants and peers were then contacted by the interviewers (SF and JM) to discuss the study and provide informed consent. Only one individual declined due to scheduling conflicts. Qualitative interviews with participants and peers were conducted between March and June 2020. Given the March 2020 COVID-19 precautions, all interviews were conducted via telephone, audio-recorded, and transcribed verbatim. For Spanish-speakers, interviews were conducted in Spanish by a native speaker, transcripts were translated to English, and analysis occurred in English. Interviews lasted approximately 45 minutes and followed a semi-structured interview guide that allowed interviewers to add, drop, and re-order questions as needed. Participants received a $20 gift card for participation and peers did not receive an incentive to participate. The interviewers wrote field notes after each interview to document emerging themes and any contextual information that would not be captured through the transcript.

Analysis

We assessed the change over time of each psychosocial measure using mixed-effects linear or logistic regression models with a random effect for each subject to account for repeated measures within individuals and missed follow-up surveys. Analyses included 228 individual encounters nested within 74 participants over the 24 month timeframe. We conducted a sensitivity analysis restricting our timeframe to the first 12 months when missing data was less pronounced. All models were adjusted for age and gender as potential confounders, and we present adjusted model-based probabilities at each time point. Analyses were conducted using Stata 15.1.

For qualitative analysis, all transcripts were reviewed by each analyst (SF and JM) and synthesized into thematic summaries. First, following a process of open coding and reviewing field notes, major conceptual categories were identified in the data. Then, each transcript was summarized to identify themes within major domains (e.g., experiences in the program, perceived impact, recommendations). The summaries were then analyzed using a constant comparative approach to finalize the themes and concepts suggested by the data.

RESULTS

Quantitative Findings

Demographic and health characteristics of our sample are summarized in Table 1. The median age of our participants was 70 years old (IQR: 66-76), and 58% were male, 15% LGBT, 18% African-American, 19% Latinx, 8% Asian, 38% reported a non-English primary language, and 36% reported at least 1 functional impairment. Baseline social characteristics (Table 2) indicated 88% lived alone, 66% had high loneliness, 36% screened positive for depression, and 24% reported DSSI scores. Among the 39 participants (51%) who reported high DSSI scores, 29 (74%) had less than 3x/week in-person contact and 30 (77%) less than 3x/week telephone-based contact with family or friends. Participants, on average, reported 3.8 barriers to socializing, with the most common barriers including physical ability (69%), distance (60%), financial capacity (73%), safety (64%), and mood (53%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants in the Peer Outreach Intervention (N=74)

| Characteristics | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Median (Interquartile Range) | 74 | 70 (66-76) |

| Range | - | 59-96 | |

|

| |||

| Gender | Female | 31 | 41.9 |

| Male | 43 | 58.1 | |

|

| |||

| Sexuality | Gay, Lesbian, or Bisexual | 13 | 17.6 |

| Heterosexual/straight | 56 | 75.7 | |

|

| |||

| Race/Ethnicity | African American | 16 | 21.6 |

| Latino(a) | 13 | 17.6 | |

| Native American | 3 | 4.1 | |

| Asian | 5 | 6.8 | |

| White | 31 | 41.9 | |

| Multi-ethnic | 1 | 1.4 | |

|

| |||

| Primary Language | Chinese | 5 | 6.8 |

| English | 46 | 62.2 | |

| Russian | 1 | 1.4 | |

| Spanish | 13 | 17.6 | |

| Other, Non-English | 3 | 4.1 | |

|

| |||

| Education | <High school | 15 | 20.3 |

| High school/GED | 19 | 25.7 | |

| Some college | 21 | 28.4 | |

| College graduate or more | 9 | 12.2 | |

| No formal education | 3 | 4.1 | |

|

| |||

| Veteran | Yes | 8 | 10.8 |

| Characteristics | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Conditions | Depression | 41 | 55.4 |

| Anxiety | 32 | 43.2 | |

| Hypertension | 24 | 32.4 | |

| Diabetes | 22 | 29.7 | |

| Cancer | 14 | 18.9 | |

| Lung disease | 8 | 10.8 | |

| Heart disease | 11 | 14.9 | |

| Prior Stroke | 7 | 9.5 | |

|

| |||

| Disability Benefits | Yes | 37 | 50.0 |

| No | 22 | 29.7 | |

| Declined answer | 15 | 20.3 | |

|

| |||

| Disability Diagnosis | Vision | 22 | 29.7 |

| Hearing | 13 | 17.6 | |

| Speech | 10 | 13.5 | |

| Cognitive | 6 | 8.1 | |

| Mobility | 36 | 48.6 | |

| Health condition | 15 | 20.3 | |

|

| |||

| Disability in Activities of Daily Living | Bathing | 22 | 29.7 |

| Dressing | 12 | 16.2 | |

| Toilet | 7 | 9.5 | |

| Moving | 7 | 9.5 | |

| Incontinence | 12 | 16.2 | |

| Eating | 6 | 8.1 | |

Table 2.

Baseline Psychosocial Characteristics of Participants (N=74)

| Characteristics | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Available Housing | 71 | 95.9 | |

|

| |||

| Live Alone | 65 | 87.8 | |

|

| |||

| Married/Partnered | 10 | 13.5 | |

|

| |||

| Currently employed | 2 | 2.7 | |

|

| |||

| Barriers to Socializing | Mean (SD) | 3.8 (1.9) | |

| Mood | 39 | 52.7 | |

| Physical Ability | 51 | 68.9 | |

| Safety | 47 | 63.5 | |

| Financial | 54 | 73.0 | |

| Physical Distance | 44 | 59.5 | |

| Substance Use | 6 | 8.1 | |

| Incontinence | 12 | 16.2 | |

| Homelessness | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Language | 11 | 14.9 | |

| Culture | 15 | 20.3 | |

|

| |||

| Loneliness (Range: 0-6) | None (0 points) | 9 | 12.2 |

| Moderate (1-2 pts) | 14 | 18.9 | |

| High (3-6 pts) | 49 | 66.2 | |

|

| |||

| Duke Social Support Index (Range: 0-20 points) | Low (0-5 points) | 17 | 23.0 |

| Moderate (6-10 pts) | 18 | 24.3 | |

| High (11+ points) | 39 | 52.7 | |

|

| |||

| Frequency Meeting up in last week with family/friends (Range 0-7+) | None | 15 | 20.3 |

| Once | 6 | 8.1 | |

| Twice | 40 | 55.6 | |

| Three or more | 11 | 15.2 | |

|

| |||

| Frequency Talking in last week with family or friends (Range 0-7+) | None | 17 | 23.0 |

| Once | 9 | 12.2 | |

| Twice | 35 | 48.0 | |

| Three or more | 12 | 16.4 | |

|

| |||

| How often can you talk about your deepest problems with family or friends? | Hardly Ever | 24 | 32.4 |

| Some of the Time | 25 | 33.8 | |

| Most of the Time | 20 | 27.0 | |

|

| |||

| Depression Screen (PHQ-2) | Positive screen | 27 | 36.5 |

Participants received a median of 43 visits (IQR: 31-97) from their peers over the first 12 months in the program (Supplementary Table 1). While peers often initially accompanied participants to health visits, the vast majority of subsequent visits were to social activities. Participants reported high satisfaction with peers and the program overall (Supplementary Table 2).

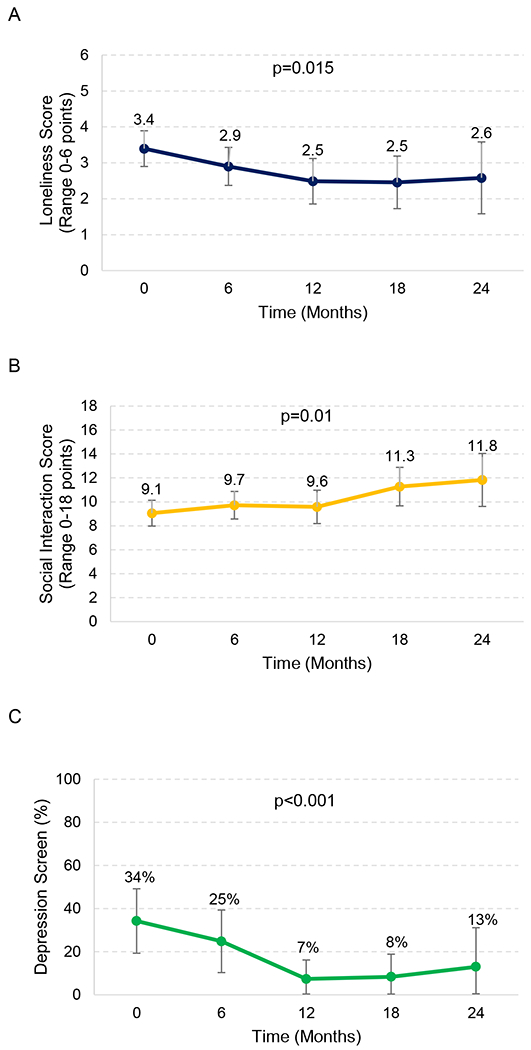

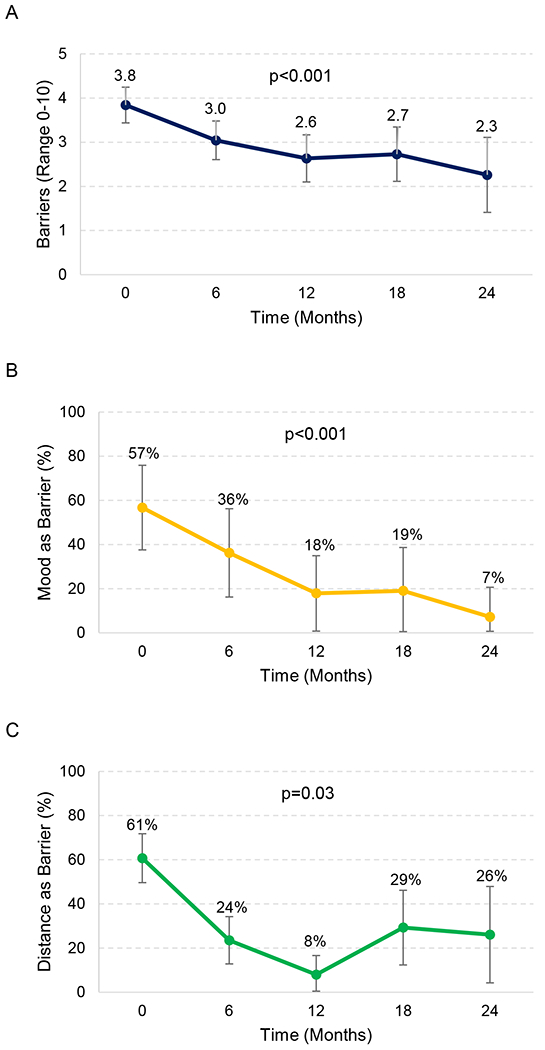

Changes in social measures were observed over time. Loneliness scores decreased by 0.8 points on average (p=0.015), with most of the change occurring in the first 12 months, and sustained at 24 months (Figure 1A). DSSI scores increased (9 points to 12 points, p=0.01), with most gains occurring in the 12-24-month portion of the study period (Figure 1B). The proportion of individuals screening positive for depression decreased from 38% to 13% (p<0.001) (Figure 1C). Individuals reported 1.5 fewer barriers to socializing over the study period (p<0.001) with the greatest reductions occurring for mood (57% to 7%, p<0.001) and distance (60% to 26%, p=0.03) (Figure 2). We conducted a sensitivity analysis restricting our timeframe to the first 12 months of follow-up which yielded similar results, except for DSSI scores where there was no significant difference.

Figure 1.

Change in A) Loneliness, B) Social interaction, and C) Depression over time. Results represent adjusted marginal estimates derived from mixed effects regression models, adjusted for age and gender. Loneliness was defined using the UCLA 3-item Loneliness Scale (Range: 0-6 points). Social interaction scores were derived from the 10-item Duke Social Support Index (Range 0-30 points). Depression was defined as a positive screen (3+ points) on the 2-item Patient Health Questionnaire Depression Screen (PHQ-2). Bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 2.

Change in self-perceived barriers to socializing over time, including A) Overall number of self-perceived barriers, B) Frequency reporting mood as a barrier, and C) Frequency reporting distance as a barrier. Results represent adjusted marginal estimates derived from mixed effects regression models, adjusted for age and gender. Bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Qualitative Findings

Qualitative interviews were conducted with 10 men (66%), 5 women (33%), including 2 transgender women, and included 5 individuals identifying as non-Hispanic White, 5 as Latinx, 2 African American, and 3 as unknown. Interviews revealed strong endorsement of the program from both the peers and participants (see Table 3). Participants described tangible benefits from peers prior to COVID-19 shelter-in-place orders, such as connections to medical and psychosocial services and accompaniment on errands. However, the overarching theme was the intrinsic value of having someone they felt emotionally and socially connected to consistently checking in on them over an extended period of time. Similarly, peers felt good about their work, that they were making a difference, and that the structure of the program facilitated trust. Both participants and peers noted these relationships helped to buffer the impact of COVID-19, which limited in-person interactions.

Table 3:

Key Themes from Qualitative Interviews of Participants and Peers

| Theme | Quote |

|---|---|

| 1. Peer as a friend (not just a job) | It’s just like having a friendship. A lot of folks I don’t really want to be friends with. You know what I’m saying? It’s nice to have someone who you can talk to who doesn’t look down on you, who doesn’t find fault in anything you say or do, and just looks at you as a person. Like I said, I don’t have much out here. My family lives in different areas in different states. I’m basically here by myself. It’s nice to have someone you can be personal with… – Participant, 65-year old woman What I enjoy is when I interact with them, we’re kind of on the same level. There’s no one talking down to them. We’re on the same level. And I’ve been through my own trials and tribulations just like they have, like everybody has. And it’s easier to communicate that and to break the ice and to get through. It’s like I can say, “I know what you feel like. I’ve been there. And I’m not a doctor talking down to you, like, oh, you need this and that and here’s your problem because I say so.” – Peer |

| 2. Positive effect on mood | Well, sometimes I feel kind of sad, because nobody visits me. And, then he appears and I’m already happy. – Participant, 64-year-old man “He’s like a mentor to me and we talk a lot. I’ve been telling him about my struggle with my addiction. Because I’m doing so much better. When I first met him, there was a period where I got back on track and I wasn’t using anything until COVID-19. I don’t go to my support group anymore, and it’s gotten bad. I just got my [new] peer worker within the last month or so. We’re planning on once this is over, that we’ll go for walks and stuff… He has lifted my self-esteem… I’m looking forward to when this - get to know each other better. I’ve only met him once.” -- Participant, 63 year-old man “I think you really have a chance to touch someone and to connect with them on however deep level you can. And establish a trusting relationship, which I think … really heals people.” – Peer “I’ve noticed that a lot of the depression … that’s started to lift. One in particular. We went in and we fixed up her apartment, or her SRO [single room occupancy]. … And we … got a TV. And this was the one who was trying to quit drinking. And she just was on fire. All of a sudden, she had this interest about setting up her apartment …. She had an interest in things again.” – Peer |

| 3. Importance of longitudinal relationship and shared background – facilitates bonding and benefits both participants and peers | “She’s been in the same road I’ve been in. Like she’s been in a shelter before. So that was something common.” – Participant, 70 year-old woman “I read on the flyer or the job description and thought, “Hey, you know what? This sounds like just me.” They’re looking for isolated seniors who don’t leave their apartments very much and who were depressed and down and isolated. You know I was that once until I started getting out and joining men’s groups. So it just took a little encouragement to get me out my shell. And the job helped me. By helping the clients, it helps me just as much because the way I was, I was isolated, so I understand what they’re going through and what they’ve gone through when it comes to isolation.” – Peer “As I’ve gotten to know her better, we can discuss our backgrounds easier…where each other comes from, you know, and that type of thing and talk about, you know, movies, things of that nature… It’s nice to have someone to discuss those things with… Because there aren’t a lot of trans people, you know, I mean in comparison to everybody else, we’re a pretty small number, it’s nice to talk to somebody that’s the same way like you.” – Participant, transwoman “[Many of our clients are LGBT and living with HIV or AIDS]… I can relate to them and understand some of the things they’re going through. I mean, I can’t really be in their shoes because everybody has different experiences, but I can basically understand how hard it is. And they’ve been around since the 70s and 60s, so they have a lot of discrimination and stuff they went through. They went through a lot of hard times. Especially during the 80s with the AIDS epidemic was. And we survived, you know? We survived, and it’s something to celebrate.” – Peer |

| 4. Flexibility of the program and service delivery (including during COVID-19) | “I just like the flexibility of actually - I guess I don’t know what to call it -it’s very free flowing. For example, tomorrow is one of my participant’s birthdays, so I haven’t planned anything, and he probably thinks that I forgot his birthday. So he’s going to have a big surprise when I show up at the door. Yeah, I’m just going to get like an Italian fizzy drink and maybe a cupcake or something. And I have one of my guitars at his place because I don’t like to carry it around. And I have a little amplifier, and we’re probably going to have a little jam session. He plays harmonica, and he’s bedridden. So I mean we have a lot of fun. And one time one of the doctors from Curry just happened to come in because she had an appointment. I can’t really say that I have appointments. I just show up. And there we were, playing guitar. And she goes, “Wow, you guys are having fun!” And we were.” – Peer “A phone call makes a lot of difference to them. So, I call them about twice a week, each client, and we chat. We talk about when the shelter-in-place thing is lifted; then I can visit them and get to know them face-to-face.” – Peer “I have one client I talk to twice a week, and we watch the Jerry Springer show because that’s what he likes. He likes the Jerry Springer show. So, I have my phone, and I watch on my TV, and he’s on his phone and watches his TV, and then we make fun, laugh, and joke about Jerry’s guests. That makes him happy, he says, so I like to do that with him. Then we have our own chat after the show is over. We chat and talk about the show and talk about small stuff just to keep the conversation going.” – Peer |

Ages were removed in situations where this information could be identifying to the peer or participant

When asked to describe their experiences with the peer, most participants noted the peer was a friend, and that the peer did not treat them as simply part of their jobs:

It’s just like having a friendship. A lot of folks I don’t really want to be friends with. … It’s nice to have someone who you can talk to who doesn’t look down on you, who doesn’t find fault in anything you say or do, and just looks at you as a person. – Participant, 65-year-old woman

Most participant-interviewees described limited social support networks, and many had decreased mobility that made it difficult for them to leave their homes and to socialize, even prior to the COVID-19 outbreak. Thus, having ongoing support from the peer helped to fill an emotional need for companionship and boost mood. Additionally, the peers observed how clients’ moods would lift and how they would become more active and interested in activities (Table 3).

Peers and participants described that it typically took a few visits to build trust and rapport. Trusted resulted from spending time together, actively listening, and bonding over shared interests and experiences. Being matched based on shared experiences – both past and present - further facilitated trust:

“As I’ve gotten to know her better, we can discuss our backgrounds easier…where each other comes from … and talk about, you know, movies, things of that nature… Because there aren’t a lot of trans-people, you know, I mean in comparison to everybody else, we’re a pretty small number, it’s nice to talk to somebody that’s the same way like you.” – Participant, transwoman

Peers also had flexibility to meet on a schedule that worked best for the participants, with many having contact by phone or in-person on a weekly basis. The flexibility of the program’s design promoted genuine connection and camaraderie.

I just like the flexibility … it’s very free flowing… One time one of the doctors from [Health Center] just happened to come in because she had an appointment. I can’t really say that I have appointments. I just show up. And there we were, playing guitar. And she goes, “Wow, you guys are having fun!” And we were. – Peer

The flexibility of the program also allowed the peers to find creative ways to support clients under the shelter-in-place restrictions. Where peers may have been seeing clients in person once a week prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, they reported calling clients more frequently to check in with them. One peer described how, since he could no longer watch TV shows with his clients in-person, they would now do so over the phone together (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate the successful implementation of a peer program to address loneliness and isolation among diverse, low-income older adults, many of whom are from traditionally marginalized groups. Over a 2-year period, the program was associated with sustained improvements in socialization, and reduced feelings of loneliness and depression. The longitudinal relationships and shared background described in qualitative interviews were central to the building of trust, rapport, and friendships and contributed to overall satisfaction.

Our findings are consistent with prior literature that show the potential for peers to address complex, intersecting health and social needs. A Canada-based study of nursing home residents found that structured, weekly peer intervention in a group format was associated with a 30% reduction in depression and 12% reduction in loneliness, along with increased socialization in facility-based activities.19 In addition, a small, 8-week intervention among primarily African American (n=27) involving weekly joint meetings with peers and mental health providers found reductions in depression.10

Our study substantially differed from prior work in several ways, which may explain why this one-to-one intervention was more successful than prior attempts using telephone-based support, gatekeepers, or clinical case managers.9 First, peers in our intervention worked independently of medical providers. Consequently, peers may have provided a social experience rather than a treatment which facilitated trusting relationships.10 Second, the flexibility accorded peers regarding the number, frequency, and goal of visits, allowed peers to tailor the experience to the needs of participants and encouraged multiple opportunities for engagement. This impact may have been more apparent over the 2 years of follow-up time compared to other studies with shorter follow-up.20 Third, peers received training in topics such as motivational interviewing, and peers provided companionship to promote safety, including to potentially targeted groups in the LGBT community. This may explain the reduction in self-reported barriers to socializing among participants, particularly mood and distance to social events. Fourth, by focusing on the unique needs of participants, for example by pairing peers and participants by language or shared life experiences, and by encouraging activities proposed by the peers and participants themselves, the program ensured that the intervention was inclusive of diverse backgrounds. This strategy may have further addressed maladaptive social cognition by helping participants gain confidence in socializing with people who shared similar interests prior to group activities.21

The effect of COVID-19 shelter-in-place orders on the program and participants was profound. Peers switched from in-person visits to twice weekly phone calls. Phone calls included conversations, guided meditation, stretching exercises, reading poetry, emotional support, education about COVID-19, and in some cases facilitating contact to health providers. Peers also connected program participants to technology (free tablets), technology support, and delivered care packages. Despite these efforts, the program lost approximately 19% of participants due to lack of phones, discomfort with phones, or lack of interest. Taken together, peers were able to support many participants because of previously established rapport, but financial and digital divides among participants amplified the effect of COVID-19 restrictions and limited the ability of peers to provide support for many.

Our study provides several lessons for scaling and implementing peer interventions in San Francisco and in other urban areas, which directly build on the recent National Academy of Sciences recommendations.8 The study’s broad inclusion criteria for older adults (e.g., asking if older adults would like help connecting with others) allowed the program to be pragmatic and reduced process barriers in recruitment. Additionally, the program’s flexibility in the number, frequency, and goals of visits helped distinguish the program from standard interventions that are offered from doctors’ offices (e.g., connection to case managers, or behavioral health). Finally, having funding from the local jurisdiction contributed to the sustainability of the program and encouraged coordination with other city programs and health providers. These partnerships allowed participants to access several city and health services that they would not have otherwise utilized. While not a specific focus of our study, peers reported the work was highly fulfilling both because of client relationships and professional development. Cities might consider peer outreach as part of publicly supported employment programs.

Research findings provide support for efforts to improve clinicians’ use of “social prescribing” between health systems and local community programs. Non-pharmacologic approaches like peer outreach to improve social and mental well-being might be used in combination with, or as a stand-alone strategy to avoid, psychoactive medications. Future research might explore strategies to improve health system partnerships with community-based programs. For example, integrating a clinical member (e.g. “link workers”) into the peer outreach team may allow for stronger partnerships, with shared records to monitor and evaluate health and health service outcomes.23

Our study has limitations. First, the design did not include a control group which limits our ability to draw causal conclusions as to the efficacy of the program. Our mixed-methods findings can inform the design of a future randomized controlled trial. Second, the strong relationships fostered between peers and participants may have led to social desirability bias. We attempted to mitigate this bias through paper-based surveys returned to study coordinators (rather than peers) and by using external evaluators. Third, qualitative interviews were conducted in English and Spanish, and may not represent experiences of participants speaking other languages. Fourth, we did not specifically target older adults who were socially isolated or lonely, and instead used a recruitment strategy focused on older adults who desired more social connection, which affects the generalizability of findings.24 Fifth, our study did not include nursing home or assisted living facility residents, who might require different program structure to align with the different social experiences of a congregate living situation as compared with community-dwelling older adults.

In conclusion, diverse, low-income older adults actively participated in a novel peer outreach program and experienced reductions in loneliness, self-perceived barriers to socializing, and depression. Such interventions represent a non-pharmacologic approach to improving psychosocial well-being among older adults and could form the basis for stronger partnerships between health systems and community programs. Lessons learned from this program can inform larger efficacy studies and further implementation of community-driven programs involving peers to address the intersecting health and social needs of older adults.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Study follow-up data flow chart.

Supplementary Table 1. Log of visits, missed connections, and connections to activities over 12 months among participants (N=74)

Supplementary Table 2. Participant Satisfaction with program (n=55)

KEY POINTS:

Among low-income diverse older adults, a peer outreach intervention to enhance social connection resulted in reduced loneliness and depression, and high satisfaction.

Why does this matter?

Peer outreach is a promising approach to improve psychosocial well-being in older adults.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the participants and peers for their participation in this program evaluation.

Funding:

Dr. Ashwin Kotwal’s effort on this project was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (K23AG065438; R03AG064323), the NIA Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30AG044281), the National Palliative Care Research Center Kornfield Scholar’s Award, and the Hellman Foundation Award for Early-Career Faculty. The Peer Intervention was supported by innovation funds from the San Francisco Mental Health Services Act Oversight and Accountability Commission awarded to the Curry Senior Center.

Sponsor’s Role:

The sponsor had no role in the design, methods, data collection, analysis, or preparation of the paper.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: All authors report no conflicts of interest.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary materials for A Peer Intervention Reduces Loneliness and Improves Social Well-Being in Low-Income Older Adults: A Mixed-Methods Study, include:

REFERENCES

- 1.Cacioppo JT, Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA. Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychology and aging 2006;21:140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaw JG, Farid M, Noel-Miller C, et al. Social isolation and Medicare spending: Among older adults, objective isolation increases expenditures while loneliness does not. Journal of aging and health 2017;29:1119–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerst-Emerson K, Jayawardhana J. Loneliness as a public health issue: the impact of loneliness on health care utilization among older adults. American journal of public health 2015;105:1013–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science 2015;10:227–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoogendijk EO, Smit AP, van Dam C, et al. Frailty combined with loneliness or social isolation: an elevated risk for mortality in later life. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2020;68:2587–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perissinotto C, Holt-Lunstad J, Periyakoil VS, Covinsky K. A practical approach to assessing and mitigating loneliness and isolation in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2019;67:657–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DAAS. Assessment of the Needs of San Francisco Seniors and Adults with Disabilities Part II: Analysis of Needs and Services. San Francisco: Department of Aging and Adult Services; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.NAS. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System; 2020. [PubMed]

- 9.Findlay RA. Interventions to reduce social isolation amongst older people: where is the evidence? Ageing & Society 2003;23:647–58. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joo JH, Hwang S, Abu H, Gallo JJ. An innovative model of depression care delivery: peer mentors in collaboration with a mental health professional to relieve depression in older adults. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2016;24:407–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu Q, You J, Man J, Loh A, Young L. Evaluating a culturally tailored peer-mentoring and education pilot intervention among Chinese breast cancer survivors using a mixed-methods approach. In: Oncology nursing forum; 2014: NIH Public Access; 2014. p. 629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Long JA, Jahnle EC, Richardson DM, Loewenstein G, Volpp KG. Peer mentoring and financial incentives to improve glucose control in African American veterans: a randomized trial. Annals of internal medicine 2012;156:416–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. Research on aging 2004;26:655–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steptoe A, Shankar A, Demakakos P, Wardle J. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2013;110:5797–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu T, Lu S, Leung DK, et al. Adapting the UCLA 3-item loneliness scale for community-based depressive symptoms screening interview among older Chinese: a cross-sectional study. BMJ open 2020;10:e041921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Powers J, Goodger B, Byles J. Duke Social Support Index. In: ALSWH Data Dictionary Supplement; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pachana NA, Smith N, Watson M, McLaughlin D, Dobson A. Responsiveness of the Duke Social Support sub-scales in older women. Age and ageing 2008;37:666–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F, Crengle S, et al. Validation of PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 to screen for major depression in the primary care population. The Annals of Family Medicine 2010;8:348–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Theurer KA, Stone RI, Suto MJ, Timonen V, Brown SG, Mortenson WB. The Impact of Peer Mentoring on Loneliness, Depression, and Social Engagement in Long-Term Care. Journal of Applied Gerontology 2020:0733464820910939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veazie S, Gilbert J, Winchell K, Paynter R, Guise J-M. Social Isolation and Loneliness Definitions and Measures. In: Addressing Social Isolation To Improve the Health of Older Adults: A Rapid Review [Internet]: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; (US: ); 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Masi CM, Chen H-Y, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Review 2011;15:219–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Savage RD, Stall NM, Rochon PA. Looking Before We Leap: Building the Evidence for Social Prescribing for Lonely Older Adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2020;68:429–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mulligan K, Bhatti S, Rayner J, Hsiung S. Social Prescribing: Creating Pathways Towards Better Health and Wellness. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2020;68:426–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dickens AP, Richards SH, Greaves CJ, Campbell JL. Interventions targeting social isolation in older people: a systematic review. BMC public health 2011;11:1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Study follow-up data flow chart.

Supplementary Table 1. Log of visits, missed connections, and connections to activities over 12 months among participants (N=74)

Supplementary Table 2. Participant Satisfaction with program (n=55)