Alzheimer’s Disease and other dementias are progressive and terminal conditions that create immeasurable suffering for those it afflicts and their loved ones. Finding effective treatments that prevent, delay, or reverse dementia is a holy grail that we all yearn for. Unfortunately, Aducanumab (Aduhelm, Biogen), which was recently approved by the FDA recently for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, is not that Holy Grail. The evidence to support Aducanumab’s clinical effectiveness is marginal at best, and may boil down to a statistical fluke at worst.1 Many have raised alarm over its approval, especially concerns over its hefty price tag: upwards of $50,000 per patient annually.2–4 Even with the FDA’s recent backtracking, adjusting the labeling of Aducanumab to limit to only people with mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia, many millions of people will still be eligible. Costs to Medicare, taxpayers, and patients could range in the tens of billions of dollars. Meanwhile, Medicare and Medicaid do not reimburse for health care delivery programs and non-pharmacological interventions with long track records of improving the quality of life for people living with dementia and their caregivers. Instead of spending money on a drug that offers only false hope, the healthcare system should pay for care that alleviates suffering. To do otherwise is an ethical failure.

For those of us who work in this field, we are heartbroken at the opportunity cost that may result from spending of limited resources on Aducanumab versus the many ways we could help people living with dementia. While others have already suggested some ideas for how this money could be better spent,5 here we expand on several specific approaches that we believe could have the highest yield in improving care for people living with dementia (PLWD) and their caregivers.

Home-Based Personal Care Services.

Getting help with personal care, such as bathing, dressing, and toileting, is often the most pressing need for PLWD and their caregivers. Yet, Medicare rarely provides coverage of home-based personal care services and Medicaid, which does offer some coverage, falls far short of meeting the actual need and varies dramatically from state to state. The average cost of a trained personal care aide costs is $20 per hour,6 so $20 billion—which is on the low end of estimates for annual spending on Aducanumab—would get you 1 billion hours of personal care, or 166 hours per person per year, or about 2 to 3 visits per week. Not only would this hands-on care help an overwhelmed caregiver who is often doing these backbreaking tasks alone7, but it would also create over a half a million caregiver jobs. Alternatively, these funds on home-based personal care services could be used to compensate family caregivers for the estimated $257 billion worth of free labor they currently provide.8 Much of this labor is provided by women and people of color, who often reduce their paid working hours or drop out of the labor market completely to care for a spouse, parent, or other relative. Dementia caregiving has been shown to increase the risk of poverty and exacerbates inequities for already vulnerable populations.6 Providing payments to these caregivers would compensate individuals for the services they provide and at the same time could help disrupt the relationship between dementia caregiving and poverty.

Comprehensive Dementia Care Programs.

Comprehensive dementia care programs are care models centered on meeting the needs of the caregiver-PLWD dyad, with the major focus on relieving the day-to-day burden of dementia. They achieve this by providing care coordination, caregiver support, medication management, and continuous monitoring and assessment, both of the PLWD and their caregivers. An example of this model is the Care Ecosystem9, which leverages non-licensed care team navigators supervised by a clinical team to provide cost-effective care primarily via telehealth to patients and caregivers who might find it difficult to make the trek into a physician’s office, such as people living in rural areas. In multiple studies over 25 years, innovative programs such as the Care Ecosystem have repeatedly been shown to improve quality of life and other outcomes for both patients and caregivers. Not only that, but they actually save money for payors through reduced spending on Emergency Department visits and hospitalizations, which are often burdensome and of questionable clinical benefit for PLWD.10 The evidence for the effectiveness of these programs far exceeds the evidence for Aducanumab—plus they save money rather than costing payors. Yet, our health system still has no way to pay to pay for these programs, which makes them very difficult to implement on a national scale.11,12

Community-Based Palliative Care.

Most people are familiar with the Medicare Hospice Benefit, which includes comprehensive services to alleviate symptoms and provide support for Medicare beneficiaries with a six-month prognosis. Community-based palliative care is a model that provides similar services as hospice and is available to all people with a serious-life limiting illness regardless of prognosis. The problem with hospice for PLWD is that dementia has an unpredictable prognosis, leading to challenges in the appropriate timing of referral to hospice.13 This has resulted in a mismatch between the trajectory of PLWD and the constraints of the hospice model. PLWD often have long stays in hospice, which frequently end in disenrollment because they no longer meet hospice eligibility criteria.14,15 Alarmed at the growing costs of hospice related to long hospice stays, Medicare has been implementing measures to disincentivize the enrollment of PLWD into hospice. This means that PLWD—who comprise 30% of all decedents 65 and older in the U.S.—have limited access to a service that evidence shows is beneficial for PLWD, improving the quality of end-of-life care and reducing burdensome treatments.16 As an alternative or bridge to hospice, community-based palliative care could be a better fit for the end-of-life course of PLWD, leading to improved end-of-life care quality and reduced Medicare spending.17 Although recent efforts—such as a U.S. Senate Bill to fund a demonstration project of community-based palliative care—represent progress, there is no current mechanism to pay for community-based palliative care, and its availability remains very limited.

Although it is not yet known whether Medicare will cover Aducanumab,18 the possibility that it will raises bigger ethical questions of why is that it’s acceptable for payors like Medicare to spend vast amounts on a medication with virtually no evidence for relieving clinical symptoms, whereas these other services and programs we’ve described, which are proven to reduce burden on PLWD and caregivers, are not?

The answer in part is the result of our current fee-for-service payment models, which incentivize and provide a mechanism for paying for medications, devices, and procedures such as the infusions necessary to administer Aducanumab.19 Value-based care, on the other hand, rewards integrated and coordinated care that improves quality of life and avoids high-cost spending that is often of limited clinical benefit. As if we needed more impetus to move away from fee-for-service towards value-based care payment models,20 the ethical quandary made apparent by the opportunity costs of Aducanumab adds even more support to these arguments.

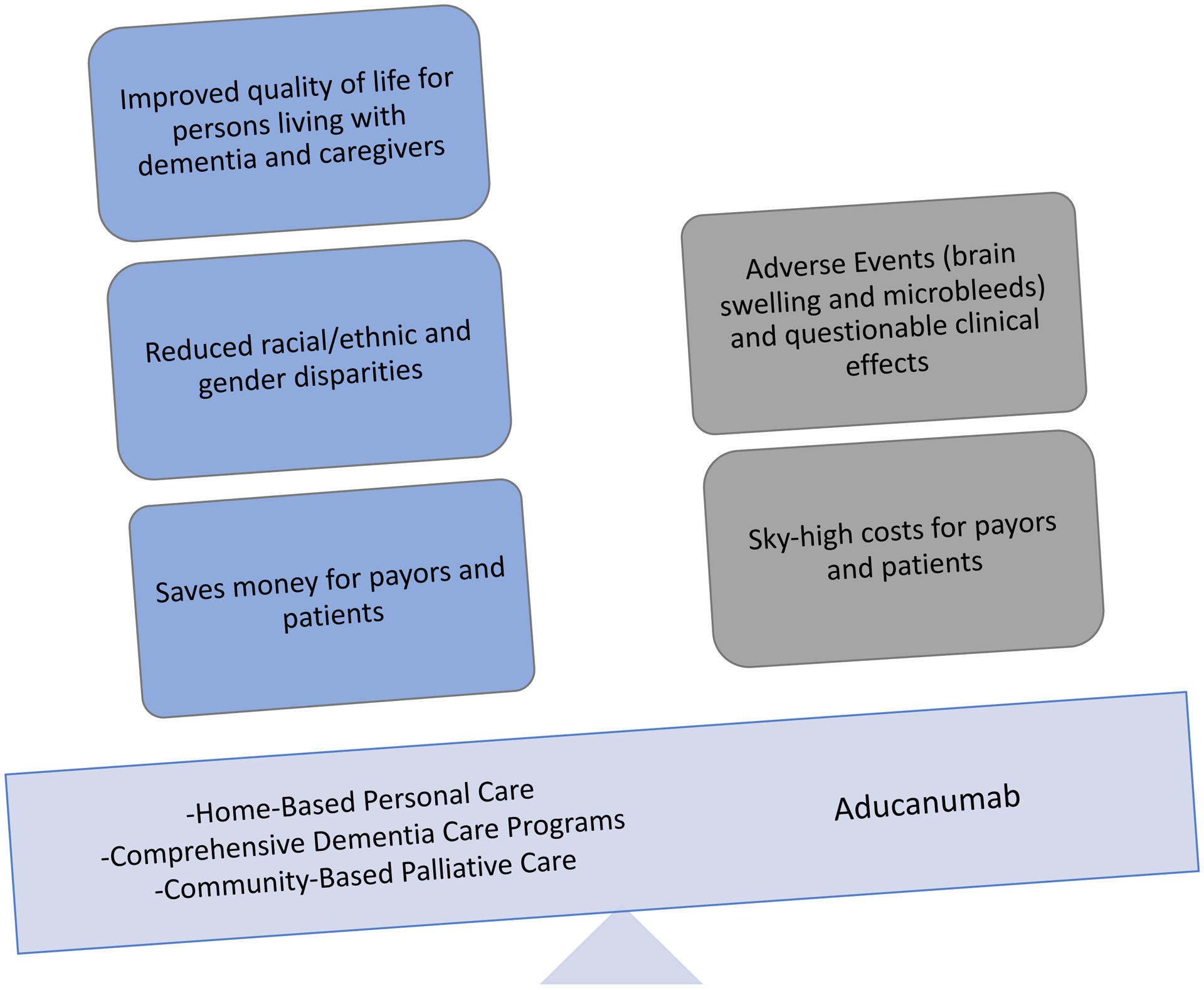

It is understandable that people want something to hope for in the face of dementia, and the direct-to-consumer advertising Biogen has already launched may succeed in convincing patients and families that Aducanumab is an elixir that provides hope in a bottle. Nobody wants to endure the pain and suffering that dementia inflicts. But in weighing up the alternatives (Figure 1), spending money on a drug with unproven efficacy when there are clinically proven programs that improve quality of life for people living with dementia and their caregivers, makes no sense at all. Instead, we should support programs and services that actually help reduce suffering of people living with dementia and their caregivers.

Figure 1.

Weighing the costs and benefits of Aducanumab compared to services proven to benefit people living with dementia and their caregivers.

Acknowledgments

Sponsor’s Role:No sponsors had any role in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Disclosures:

Dr. Lauren Hunt: National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the NIH (KL2TR001870)

Dr. Krista Harrison: NIH/NIA K01AG059831

Dr. Kenneth Covinsky: NIH/NIA P30AG044281

References

- 1.fda.gov. https://www.fda.gov/media/143505/download. Published 2020. Accessed June 18, 2021.

- 2.Crosson FJ, Covinsky K, Redberg RF. Medicare and the Shocking US Food and Drug Administration Approval of Aducanumab: Crisis or Opportunity? JAMA internal medicine. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knopman DS, Perlmutter JS. Prescribing Aducanumab in the Face of Meager Efficacy and Real Risks. Neurology. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walsh S, Merrick R, Milne R, Brayne C. Aducanumab for Alzheimer’s disease? BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2021;374:n1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graham J Paying Billions for Controversial Alzheimer’s Drug? How About Funding This Instead? Kaiser Health News 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelley AS, McGarry K, Gorges R, Skinner JS. The burden of health care costs for patients with dementia in the last 5 years of life. Annals of internal medicine. 2015;163(10):729–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ornstein KA, Wolff JL, Bollens-Lund E, Rahman OK, Kelley AS. Spousal Caregivers Are Caregiving Alone In The Last Years Of Life. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2019;38(6):964–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2021;17(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Possin KL, Merrilees JJ, Dulaney S, et al. Effect of Collaborative Dementia Care via Telephone and Internet on Quality of Life, Caregiver Well-being, and Health Care Use: The Care Ecosystem Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA internal medicine. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jennings LA, Turner M, Keebler C, et al. The Effect of a Comprehensive Dementia Care Management Program on End-of-Life Care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2019;67(3):443–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Callahan CM, Unroe KT. How Do We Make Comprehensive Dementia Care a Benefit? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2020;68(11):2486–2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lees Haggerty K, Epstein-Lubow G, Spragens LH, et al. Recommendations to Improve Payment Policies for Comprehensive Dementia Care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2020;68(11):2478–2485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell SL, Miller SC, Teno JM, Kiely DK, Davis RB, Shaffer ML. Prediction of 6-month survival of nursing home residents with advanced dementia using ADEPT vs hospice eligibility guidelines. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;304(17):1929–1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Vleminck A, Morrison RS, Meier DE, Aldridge MD. Hospice Care for Patients With Dementia in the United States: A Longitudinal Cohort Study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2018;19(7):633–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunt LJ, Harrison KL. Live discharge from hospice for people living with dementia isn’t “graduating”-It’s getting expelled. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2021;69(6):1457–1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Lee IC, et al. Does hospice improve quality of care for persons dying from dementia? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2011;59(8):1531–1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrison KL, Hunt LJ, Ritchie CS, Yaffe K. Dying With Dementia: Underrecognized and Stigmatized. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2019;67(8):1548–1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schulman KA, Greicius MD, Richman B. Will CMS Find Aducanumab Reasonable and Necessary for Alzheimer Disease After FDA Approval? JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emanuel EJ. The Real Cost of the US Health Care System. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2018;319(10):983–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnston KJ, Hockenberry JM, Joynt Maddox KE. Building a Better Clinician Value-Based Payment Program in Medicare. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2021;325(2):129–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]