Abstract

Background

Little is known about the underlying mechanisms through which early palliative care (EPC) improves multiple outcomes in patients with cancer and their caregivers. The aim of this study was to qualitatively and quantitatively analyze patients’ and caregivers’ thoughts and emotional and cognitive perceptions about the disease prior to and during the EPC intervention, and in the end of life, following the exposure to EPC.

Materials and Methods

Seventy‐seven patients with advanced cancer and 48 caregivers from two cancer centers participated in semistructured interviews. Their reports were qualitatively and quantitatively analyzed by the means of the grounded theory and a text‐analysis program.

Results

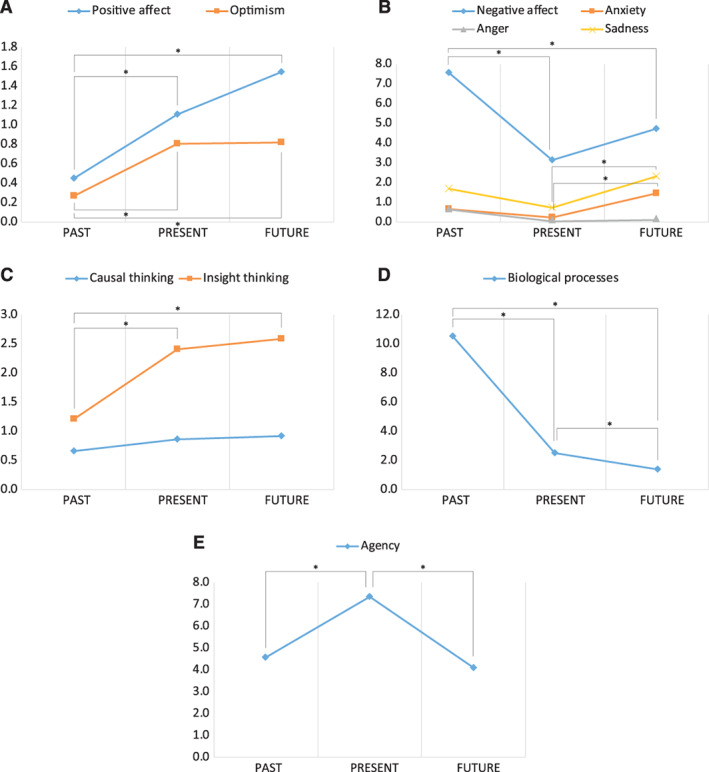

Participants reported their past as overwhelmed by unmanaged symptoms, with detrimental physical and psychosocial consequences. The EPC intervention allowed a prompt resolution of symptoms and of their consequences and empowerment, an appreciation of its multidimensional approach, its focus on the person and its environment, and the need for EPC for oncologic populations. Patients reported that conversations with the EPC team increased their acceptance of end of life and their expectation of a painless future. Quantitative analysis revealed higher use of Negative Affects (p < .001) and Biological Processes words (p < .001) when discussing the past; Agency words when discussing the present (p < .001); Positive Affects (p < .001), Optimism (p = .002), and Insight Thinking words (p < .001) when discussing the present and the future; and Anxiety (p = .002) and Sadness words (p = .003) when discussing the future.

Conclusion

Overall, participants perceived EPC to be beneficial. Our findings suggest that emotional and cognitive processes centered on communication underlie the benefits experienced by participants on EPC.

Implications for Practice

By qualitative and quantitative analyses of the emotional and cognitive perceptions of cancer patients and their caregivers about their experiences before and during EPC interventions, this study may help physicians/nurses to focus on the disease perception by patients/caregivers and the benefits of EPC, as a standard practice. The analysis of words used by patients/caregivers provides a proxy for their psychological condition and support in tailoring an EPC intervention, based on individual needs. This study highlights that the relationship of the triad EPC team/patients/caregivers may rise as a therapeutic tool, allowing increasing awareness and progressive acceptance of the idea of death.

Keywords: Early palliative care, Patients, Caregivers, Qualitative research, Pain, Quantitative tool

Short abstract

Early palliative care can improve experiences and outcomes for patients with advanced cancer. This article analyzes disease perceptions of cancer patients and their caregivers before and after early palliative care intervention.

Introduction

In the last decade, increased awareness has emerged about the benefits of integrating early palliative care (EPC) into standard care (SC) for patients with cancer and their caregivers [1, 2, 3]. Specifically, EPC has been shown to improve quality of life (QoL) [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8], mood [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8], prognostic awareness [9, 10], and symptom control [11], as well as reduce the risk of severe pain [1, 4], decrease chemotherapy use near death [3, 6, 11, 12], reduce aggressiveness of therapy [3, 6, 11, 12], increase enrollments in hospice care [3, 6, 11, 12], and improve survival [3, 13]. Benefits from EPC were also found for caregivers of patients with cancer in randomized clinical trials [14]. They reported lower depression and caregiver burden [5, 15, 16], improvements in coping strategies [5], and greater satisfaction with care [17]. Few recent reports have also indicated benefits of EPC for patients with hematologic diseases [5, 18, 19].

However, questions remain about how the EPC model achieves these valuable outcomes [20, 21, 22, 23, 24]. Previous qualitative research has addressed this issue by analyzing electronic health records [25] and interviews with oncologists and palliative care (PC) physicians [20, 26]. Other investigators have collected opinions of patients and caregivers who participated in EPC trials, identifying perceived benefits and differences compared with SC [3, 21, 27]. Specifically, patients and caregivers reported enhanced problem‐solving skills, coping strategies, and feelings of empowerment, guidance, and reassurance, through personalized symptom management and holistic support [21, 27]. The comparison between reports from participants receiving EPC and those from participants receiving oncology SC showed that EPC focuses on the person rather than the disease, and is based on a more flexible, less time‐constrained delivery model, mainly led by the patient instead of the physician [3].

In our experience of EPC [1, 4], we have observed changes in patients’ and caregivers’ language during their weekly appointments. In the current study, patients and caregivers, followed during a routine EPC practice in a real‐life, outpatient setting, were invited to participate in semistructured interviews to discuss their thoughts and feelings about the disease and treatment at different moments of their clinical course (prior to and during the EPC intervention) and to reflect on the future, including the end of life, following the exposure to EPC.

Our primary objective was to qualitatively analyze patients’ and caregivers’ reports and to describe emerging themes from a temporal perspective (past, present, and future). Our secondary objective was to apply a psycholinguistic quantitative approach to investigate how patients’ and caregivers’ cognitive and emotional processes may change along the disease trajectory, when an intervention of EPC is provided, and whether these changes mirror the main themes identified through the qualitative analysis.

Materials and Methods

Participants

This study was embedded within the outpatient Oncology and Palliative Care Unit, Civil Hospital Carpi, USL, and the outpatient Palliative Care Unit, Section of Hematology, Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria di Modena, both located in Modena, Italy. Seventy‐seven patients with advanced cancer under EPC were consecutively enrolled between July 2020 and June 2021. Patients were asked to identify their primary caregiver/s, who was/were then also invited to participate to the study; caregiver refusal did not prevent patient participation. Forty‐eight caregivers participated in the study. Patient and caregiver eligibility required willingness to complete the interview and age ≥ 18 years. All participants provided written informed consent prior to data collection.

The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Modena (N. 0026448/20).

Organization of the EPC Units

Our outpatient PC oncology and hematology units were established in 2006 and 2012, respectively, and integrate primary oncology and hematology specialists with a palliative/supportive care team composed of one physician assistant, one fellow, and one nurse with specialized PC training and expertise, to provide comprehensive symptom management and psychosocial, spiritual, and emotional support to patients with cancer and their families, from the time of diagnosis to advanced/metastatic disease according to established guidelines [1, 4]. Patients with an advanced/metastatic cancer diagnosis (with distant metastases, in case of solid tumors, late‐stage disease, and/or a prognosis of 6–24 months) with high symptom burden are electively referred by the oncologists to receive an EPC intervention. The EPC team follows on average 20–30 patients/week and each patient on a regular basis, 1–2 times/week. Outpatients’ EPC interventions are integrated with both specialized nurse home care services and hospices [1, 4, 27].

Data Collection

Patients completed an anonymous, self‐administered pen‐and‐paper semistructured interview during their appointments at the Units. Caregivers completed the same task at home. Participants were asked to report their thoughts and feelings about their experience with the disease prior to the EPC intervention (henceforth, their past), about their experience during the EPC intervention (henceforth, their present), and about possible changes in the perception and expectations of their future, including at the end of life, following the exposure to EPC (henceforth, their future). The semistructured interview ended by a fourth, open question, allowing participants to openly express their thoughts (supplemental online Table 1). The sample characteristics were collected with the support of our database and chart reviews.

Statistical Analysis

Qualitative Analysis

Qualitative analysis was based on the grounded theory with the support of NVivo software (Burlington, MA), similar to the methodology adopted by Hannon et al. [3, 21]. Grounded theory involves the simultaneous collection and analysis of data in a systematic yet flexible way to build a theory grounded on participants’ views [28, 29]. Through a gradual, line‐by‐line coding process, we first identified elements in the reports and chose those that required closer analysis, based on their prevalence and importance; we then analyzed and discussed their relationships and produced theoretical codes to capture the process. Two PC physicians and one psycholinguist developed the coding system individually and refined it through periodic meetings and discussions.

Quantitative Analysis

Quantitative analysis was performed on the questions about the past, present, and future, by the means of the Italian version of the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count software [30]. This is an automated, text‐analysis program that measures the percentage of use of theoretically defined categories of words in either text or speech [31]. We coded 10 categories and subcategories of interest that allowed us to investigate participants’ emotional and cognitive processes, biological processes, and agency (i.e., the perceived capacity of a subject to produce an effect [32]) (supplemental online Table 2).

Shapiro‐Wilk tests and Q‐Q plots visual inspection revealed a non‐normal distribution of the variables of interest. Therefore, nonparametric Friedman tests were performed on each one, with the factor Time (past vs. present vs. future) as an independent variable, to test differences in the use of these word categories within the two groups of participants. If any significant effect was detected, Conover's post hoc Bonferroni‐corrected pairwise comparisons were conducted to identify the specific differences. We included education level as a covariate since it provides a proxy for the width of vocabulary skills [33].

Results

One hundred thirty‐five new patients were referred to the EPC units during the recruiting process. Thirty‐five patients with 1–2 visits were considered either referred too late during the disease trajectory or undergoing interim evaluations before being referred to hospice or home care, and thus were not eligible for this study, as they were considered end‐of‐life patients. Of the remaining 100 eligible patients, 23 refused to participate because of feeling uncomfortable or not being interested, resulting in a patient response rate of 77%. Eighty caregivers were identified by patients, of whom 32 refused to participate because of feeling uncomfortable or not being interested, resulting in a caregiver response rate of 60%.

The mean age of the 77 patients enrolled was 67.4 years. Sixty‐six were diagnosed with solid cancer, whereas 11 had a hematologic malignancy. The mean time receiving EPC was 11.9 months. Thirteen patients began EPC treatment within 90 days from advanced/metastatic cancer diagnosis.

The mean age of the 48 caregivers was 55.9 years, of whom 34 cared for patients with solid cancer and 14 for patients with hematologic cancer.

Additional details are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical/caregiving characteristics of the sample (n = 125)

| Characteristics | Patients (n = 77) | Caregivers (n = 48) |

|---|---|---|

| Age at interview, yr | ||

| Mean (SD) | 67.4 (12.4) | 55.9 (14.1) |

| Range | 35–87 | 26–81 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 35 (45.5) | 33 (68.75) |

| Male | 42 (54.5) | 15 (31.25) |

| Education, n (%) | ||

| Primary school | 7 (9.1) | 3 (6.3) |

| Secondary school | 25 (32.5) | 10 (20.8) |

| College | 34 (44.2) | 18 (37.5) |

| Bachelor's degree | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Graduate degree | 5 (6.5) | 12 (25) |

| Missing data | 6 (7.8) | 5 (10.4) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White | 66 (85.7) | 42 (87.5) |

| Arabian | 3 (3.9) | 0 (0) |

| Missing data | 8 (10.4) | 6 (12.5) |

| Religion, n (%) | ||

| Catholic | 45 (58.4) | 33 (68.8) |

| Muslim | 3 (3.9) | 0 (0) |

| Evangelical | 1 (1.3) | 1 (2.1) |

| Jehovah's Witness | 1 (1.3) | 1 (2.1) |

| Atheist | 20 (26) | 8 (16.7) |

| Missing data | 7 (9.1) | 5 (10.4) |

| Cancer diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| Solid | 66 (85.7) | 34 (70.8) |

| Head, neck, larynx | 5 (6.5) | — |

| Rectum, sigma | 1 (1.3) | — |

| Colon | 8 (10.4) | — |

| Gastric | 9 (11.7) | — |

| Pancreas | 5 (6.5) | — |

| Breast | 12 (15.6) | — |

| Lung | 8 (10.4) | — |

| Genitourinary (kidney, testis, prostate, ovary) | 11 (14.3) | — |

| Skin | 2 (2.6) | — |

| Sarcoma | 3 (3.9) | — |

| Missing data | 2 (2.6) | — |

| Hematologic | 11 (14.3) | 14 (29.2) |

| Time since first EPC consult, mo | ||

| Mean (SD) | 11.9 (16.6) | 12.6 (13.1) |

| Range | 2–96 | 2–48 |

| KPS score at first EPC consult, median (IQR) | ||

| 0–100 | 60 (50–60) | — |

| NRS pain score at first EPC consult, median (IQR) | ||

| 0–10 | 7 (6–8) | — |

| Active CT at first EPC consult, n (%) | 52 (72.2) | — |

| Relationship to patient, n (%) | ||

| Parent | — | 1 (2.1) |

| Spouse/partner | — | 22 (45.8) |

| Daughter/son | — | 19 (39.6) |

| Sister/brother | — | 2 (4.2) |

| Other family | — | 2 (4.2) |

| Missing data | — | 2 (4.2) |

Abbreviations: —, no data; CT, chemotherapy; EPC, early palliative care; IQR, interquartile range; KPS, Karnofsky Performance Status; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale.

Qualitative Analysis on Patients’ and Caregivers’ Perceptions

Emerging themes about the past, the present, and the future and the open question are reported in Tables 2, 3, 4, 5 with illustrative quotations.

Table 2.

Emerging themes and illustrative quotations referred to the past

| Themes | Quotations |

|---|---|

Physical symptoms as an unmet need:

|

“I had bone pain [unmanaged symptoms] and edema in the legs [unmanaged symptoms]” (002‐P‐021) |

| “I was extremely tired, I got nausea [unmanaged symptoms] (002‐P‐021)” | |

| “I had very severe pain [unmanaged symptom], I could not tolerate the chemotherapy, I had nausea, swollen belly [unmanaged symptom],” (002‐P‐038) | |

| “I had severe pain in the arm [unmanaged symptoms]” (002‐P‐038) | |

| “However, the pain [unmanaged symptoms]” (002‐P‐038) | |

| “Because of pain and fatigue [unmanaged symptoms], (002‐P‐043) | |

| “This state of malaise [unmanaged symptoms]” (002‐P‐043) | |

| “I felt bad [unmanaged symptoms],” (002‐P‐023) | |

| “I had bone pain [unmanaged symptoms]” (002‐P‐023) | |

| “I had severe pain [unmanaged symptoms], I was sick [unmanaged symptoms],” (002‐P‐033) | |

| “I had very severe pain in the spine [unmanaged symptoms]” (002‐P‐040) | |

| “I had very severe pain in the bones [unmanaged symptoms] where I have metastases.” (002‐P‐035) | |

| “…that prevented me from walking [impact on physical functioning]” (002‐P‐022) | |

| “…and could no longer lead a normal life [impact on physical functioning].” (002‐P‐022) | |

| “I could not stand [impact on physical functioning]” (002‐P‐038) | |

| “…and I wasn't able to move it [impact on physical functioning]. This greatly limited my ability to lead a "normal" life [impact on physical functioning]. I am young and my wish to live, work and be with others is very present and strong.” (002‐P‐038) | |

| “I couldn't stand up [impact on physical functioning].” (002‐P‐043) | |

| “I couldn't stand up [impact on physical functioning],” (002‐P‐023) | |

| “I had bone pain [unmanaged symptoms] that didn't allow me to walk, breathe [impact on physical functioning],” (002‐P‐023) | |

| “I could no longer do anything [impact on physical functioning/social life].” (002‐P‐033) | |

| “Due to my tumor that prevented me from leading a "normal" life [impact on functioning]; my life had become "absolutely unlivable" [impact on physical functioning/mood/social life], (002‐P‐040) | |

| “I felt very tired [impact on physical functioning], (002‐P‐035) | |

| “However, the pain [unmanaged symptoms] changed me a lot and made me introverted and negative [impact on mood/social life].” (002‐P‐038) | |

| “This state of malaise [unmanaged symptoms] created a great psychological and moral discomfort [impact on mood] and I felt very distressed and alone [impact on mood/social life].” (002‐P‐043) | |

| “I didn't want to put the weight of my condition on the family [impact on social life].” (002‐P‐043) | |

| “I could no longer do anything [impact on physical functioning/social life].” (002‐P‐033) | |

| “My life had become "absolutely unlivable" [impact on physical functioning/mood/social life], (002‐P‐040) | |

| “My quality of life was very bad, I could no longer live and this isolated me very much from any relationships [impact on social life],” (002‐P‐035) | |

| “I don't deny that, recently, the progression of the disease and the ineffectiveness of oncological treatments led me to a deep depression and a great psychological deterioration [impact on mood].” (002‐P‐022) | |

| “I was very dejected and depressed. I wanted to die [impact on mood].” (002‐P‐038) | |

| “However, the pain [unmanaged symptoms] changed me a lot and made me introverted and negative [impact on mood/social life].” (002‐P‐038) | |

| “This state of malaise [unmanaged symptoms] created a great psychological and moral discomfort [impact on mood] and I felt very distressed and alone [impact on mood/social life].” (002‐P‐043) | |

| “I had bone pain [unmanaged symptoms] that didn't allow me to walk, breathe [impact on physical functioning], live [impact on physical mood].” (002‐P‐023) | |

| “I was terrified and distressed [impact on mood].” (002‐P‐023) | |

| “I was depressed [impact on mood].” (002‐P‐033) | |

| “My life had become "absolutely unlivable" [impact on physical functioning/mood/social life], (002‐P‐040) | |

| “I was plunged into the blackest despair [impact on mood].” (002‐P‐040) | |

| “Since my wife got sick, I have lived in symbiosis with her sufferance. In 2013, when she began her calvary with the diagnosis of her tumor, I experienced depression for a long time, I couldn't even get out of bed [impact on mood].” (002‐C‐001). | |

| “…the most terrible thing for me. I was dead [impact on mood].” (002‐P‐035) | |

Pain as the most frequent reason for referral

|

“I was in such pain that I was unable to even get dressed (…). So, the doctor said: ‘First, let's take the pain away from you [pain as the most frequent reason for referral], then you will come back for the ultrasound.’" (002‐P‐003). |

| “I am surprised that [name of hospital], which is considered a center of excellence, does not have a doctor in charge to the management of pain. I can't believe it. What should I think about a hospital that does not plan early palliative care for patients? The oncologist followed my clinical course (…) but he did not take care of my pain. If I hadn't known about this early palliative care unit, I would still be suffering from pain [regrets about not being informed earlier].” (002‐P‐004) | |

| Ineffectiveness of standard therapy as the second reason for referral | “I was referred to the early palliative care unit because at the oncology unit they told me that the most important treatments were over [Ineffectiveness of standard therapy as the second reason for referral].” (002‐P‐010) |

Psychological impact on caregivers:

|

“While seeing my husband deteriorating and suffering, I was very depressed, I felt alone and helpless [seeing the beloved's suffering], because I was trying to face something greater than me.” (002‐C‐037) |

| “I found myself catapulted into a world that was unknown to me [being thrown into the role]; I have never had the dramatic experience of beloveds becoming ill, with rather hard and critical diagnoses, so I was almost unaware of everything that the disease entails and the way a caregiver could approach this path [being thrown into the role].” (002‐C‐019) |

At the end of each quotation, the ID of the participant is reported: the first three numbers indicate the unit (001 for the Hematology Unit, Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Policlinico, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia Azienda Ospedaliera of Modena and 002 for the Oncology and Palliative Care Unit, Civil Hospital Carpi), the letter indicates patient (P) or caregiver (C), and the last three numbers indicate the recruitment progressive number).

Abbreviation: EPC, early palliative care.

Table 3.

Emerging themes and illustrative quotations referred to the present

| Themes | Quotations |

|---|---|

Symptom resolution (first perceived effect):

|

“Now the pain is much better [symptoms resolution].” (002‐P‐039) |

| “Pain immediately eased [symptoms management].” (002‐P‐039) | |

| “This care solved his pain within a few days, and everything improved [symptoms resolution].” (002‐C‐037) | |

| “Palliative team's mantra ‘You must not have pain’ is something that fills my soul [appreciation and endorsement].” (002‐P‐026) | |

| “They solved my problem in two days. Two days [speed].” (002‐P‐004) | |

| “Early palliative care allowed me to have my life back [return to a normal life].” (002‐P‐008) | |

| “It brought me back from death to life [return to a normal life ‐ metaphor].” (002‐P‐017). | |

| “I can enjoy life more, I started doing the things I could no longer do: walking, walking with my dog, seeing people, live [return to a normal life].” (002‐P‐039) | |

| I can enjoy life more, I started doing the things I could no longer do: walking, walking with my dog, seeing people, live [return to a normal life].” (002‐P‐039) | |

| allowing me to resume work, travel, relationships [return to a normal life] (…). I can enjoy life more, I started doing the things I could no longer do: walking, walking with my dog, seeing people, live [return to a normal life].” (002‐P‐039) | |

| “…and I feel now able to live a normal life, with relationships [return to a normal life]. My quality of life has changed.” (002‐P‐035) | |

| “He was more willing to smile, he was more friendly, he had positive thoughts [return to a normal life].” (002‐C‐037) | |

Empowerment (second perceived effect) raising from:

|

“They talk to me, listen to me [active and open listening] and explain things to me, whereas no one explained to me what was happening, during my earlier experience. (002‐P‐050) |

| “Sincerity. Sincerity. Because this is very important, at least it's what I need [sincerity].” (002‐P‐026) | |

| “They did not make me feel either abandoned to myself nor alone with bad thoughts [support], that have been always tightly tied with my pain and suffering.” (002‐P‐047) | |

Empowerment (second perceived effect) that led to:

|

“(…) but they allowed me, through precise and exhaustive explanations, to get a knowledge and the full awareness [awareness] of my symptoms and my state of health, in general.” (002‐P‐030) |

| “Especially, I was able to talk to the EPC physician and confidently decide to stop the chemotherapy [awareness/enhanced problem‐solving skills].” (002‐P‐044) | |

| “Early palliative care allowed me to make the most delicate decisions [enhanced problem‐solving skills]; for example, when I decided to stop cancer therapies, because they were no longer effective [enhanced problem‐solving skills].” (002‐P‐022) | |

| “Especially, I was able to talk to the EPC physician and confidently decide to stop the chemotherapy [awareness/enhanced problem‐solving skills].” (002‐P‐044) | |

| “I know I have a terminal disease, but now I feel more peaceful [improved coping].” (002‐P‐040). | |

| “Now, with no pain, I am less worried. I feel stronger because I think I will be able to face what life has in store for me [improved coping].” (002‐P‐046) | |

|

Components of EPC:

|

“I am happy with the EPC unit, they are very professional, very competent in everything: psychological aspects, more practical issues, everything [holistic/multidisciplinary approach].” (002‐P‐013) |

| “It is not only the drug therapy, but the attempt in supporting me and my needs in any possible ways [holistic/multidisciplinary approach].” (002‐P‐002) | |

| “It is not only the intravenous infusions that helped me [holistic/multidisciplinary approach.” (002‐P‐008) | |

| “What pushed me toward this cure is that they talk to my healthy part [person‐centered].” (002‐P‐026) | |

| “I fully trust doctors at the EPC unit, because they know how to talk to the healthy part of myself [person‐centered].” (002‐P‐043) | |

| They talk to me, they listen to me, and they explain everything to me [person‐centered], whereas, no one explained to me what was happening, during my earlier experience.” (002‐P‐050) | |

| Above all, I feel peaceful, because I know that there are people who take care of me and will not abandon me [person‐centered].” (002‐P‐045) | |

| “The luck is that a beautiful, almost familiar environment has been created [environment].” (002‐P‐004) | |

| “I love the doctor and the nurse, because they make me feel at home [environment]. (002‐P‐050) | |

| “By thinking that I always see the kind and smiling faces welcoming me [environment], when I go to the EPC unit, means a lot. (002‐P‐045) | |

| “…but it was also the environment that made me feel good [environment].” (002‐P‐008) | |

| “I expected a sense of unavoidability inside [the EPC clinic], but after a few visits, I was very surprised by the spontaneity with which the patients talked about their problems. They also began to consider them with greater detachment and even with a certain form of lightness [environment created by other patients]!” (001‐C‐010) | |

| “Here you gain back all the desire to live, because we prepare dinners together, we laugh together, we together overcome the difficulties we face [environment created by other patients], because if, today, I feel sad, all of them take care of me, for example by phone calls. It's definitively amazing. It's a sort of a new community, someone call it sangha [environment created by other patients].” (002‐P‐003) | |

| Caregivers more focused on the end of life | “Early palliative care is the only way to accompany the patient and his family in a relation of truth and awareness, helping to approach the idea of death and death itself, without anguish and denial; my wife was released from pain and I had the chance to prepare myself to say goodbye to my beloved, to say and to do the things, I considered and felt were important to say and to do with her [caregivers more focused on the end of life].” (002‐C‐035) |

| “The way allows you to come to the end of life with serenity and dignity [caregivers more focused on the end of life].” (002‐C‐033) | |

Need of EPC:

|

“I would call this care, the care for life [need of EPC].” (002‐P‐035) |

| “A person, beyond the physical problems that the disease entails, enters a tunnel of fear and insecurity. In this sense, I believe that the early palliative care is fundamental, on various levels [need of EPC].” (002‐C‐001) | |

| “Early palliative care is fundamental as a complement to standard therapy [need of EPC with standard care].” (001‐C‐012) | |

| “Without detracting from the undisputed validity of everything that is important and that I have done, early palliative care is undoubtedly a lifesaver [need of EPC with standard care].” (002‐P‐014) | |

| “Chemotherapy and cancer therapy are good, but without this part of care, in my opinion, they are not useful. This part of care has an incredible relevance [need of EPC with standard care].” (002‐P‐002) | |

| “While chemotherapy helped, serious problems came out, but the early palliative care immediately allowed my husband to feel better, without pain, and to help him to lead a normal and peaceful life. The more time goes by and the more I understand that they are necessary [need of EPC with standard care].” (002‐C‐037) | |

| “I am convinced that the patient under oncological treatment, who has the opportunity to have concomitant palliative care, may experience a sort of oncological treatment at its maximal effectiveness [need of EPC with standard care].” (002‐P‐030) | |

| “I often say that oncology, radiotherapy… they are all important for this disease, but without ePSC they are meaningless [need of EPC with standard care], because if I'm sick and the oncologist gives me chemotherapy, I'm even worse, and I can't see the immediate benefit.” (002‐P‐003) | |

| “(…) an alternative to relentless treatments [need of EPC without standard care]” (002‐C‐021) | |

| “To me early palliative care is fundamental (…). Now, I am no longer undergoing cancer treatments because they made me feel bad [need of EPC without standard care]. Now I'm quiet.” (002‐P‐050) | |

| “Early palliative cares were a salvation, a light. (…) Above all, I was able to talk to the doctor and, calmly, decide to suspend the chemotherapy. While taking such a decision, being aware and confident that such a team will keep taking care of my clinical problems and of myself, as a person, was, truly, a salvation [need of EPC without standard care].” (002‐P‐044) |

At the end of each quotation, the ID of the participant is reported: the first three numbers indicate the unit (001 for the Hematology Unit, Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Policlinico, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia Azienda Ospedaliera of Modena and 002 for the Oncology and Palliative Care Unit, Civil Hospital Carpi), the letter indicates patient (P) or caregiver (C), and the last three numbers indicate the recruitment progressive number).

Abbreviation: EPC, early palliative care.

Table 4.

Emerging themes and illustrative quotations referred to the future

| Themes | Quotations |

|---|---|

|

Acceptance of the end of life:

|

“I am afraid of dying and suffering a lot [not always comfortable].” (002‐P‐034) |

| “I no longer have the fear I had before, I know that these doctors will accompany me and will not make me suffer [absence of suffering].” (002‐P‐048) | |

| “Now, without pain, I am more confident and more hopeful. Now, I can live well for the time that God will give me. Death doesn't scare me; pain and suffering do scare me a lot [absence of suffering].” (002‐P‐042) | |

| “If I don't suffer, but only at this condition, I can accept the idea of my death [absence of suffering]. (002‐P‐040) | |

| In the last months, doctor and I have often addressed these aspects in our conversations, and this is the thing that, personally, I appreciated most [conversations with the team]. Being able to talk about certain things, which is not easy for me (for example with my loved ones), has really helped me in understanding and also in accepting.” (002‐P‐040) | |

|

“I am having good conversations with the early palliative care team on these issues which, I confess, are helping me a lot in understanding and accepting and in getting rid of my fears [conversations with the team].” (002‐P‐043) | |

| “The conversations with the team are very important to me and are helping me to change my attitude [conversations with the team], but I think it will take a long time to accept the idea of death.” (002‐P‐041) | |

| “This care is helping me a lot to talk about my death, to know how long I have left to live, because it is important for me to be aware of. So, I can choose not to undergo further unnecessary chemotherapy programs. While speaking with the doctor and nurse I have opted to stay with my family and then, when the end comes, to go to the hospice [information about end‐of‐life options], to free my son and husband from a too heavy burden.” (002‐P‐027) | |

Caregivers:

|

“To see my sister peaceful is everything to me [acceptance tied to the beloved's acceptance, absence of suffering].” (002‐C‐041) |

| “A thing that I have realized is that death is not acceptable if it is accompanied by great suffering. Before these treatments, my husband's illness was just huge suffering [acceptance tied to the beloved's acceptance, absence of suffering].” (002‐C‐014) | |

| “To me (…) it is important that his life is a decent and pain‐free life [acceptance tied to the beloved's acceptance, absence of suffering].” (002‐C‐035) | |

| “I feel taken by the hand [caregiver not left alone], I don't feel lonely and desperate like I was before coming here.” (002‐C‐040) |

At the end of each quotation, the ID of the participant is reported: the first three numbers indicate the unit (001 for the Hematology Unit, Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Policlinico, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia Azienda Ospedaliera of Modena and 002 for the Oncology and Palliative Care Unit, Civil Hospital Carpi), the letter indicates patient (P) or caregiver (C), and the last three numbers indicate the recruitment progressive number).

Table 5.

Emerging themes and illustrative quotations emerging from the open question

| Themes | Quotations |

|---|---|

Gratitude:

|

“I am grateful for early palliative care [gratitude to EPC model] that is helping me not to suffer and accompanying me, humanly and spiritually, in everything, especially in the awareness of what I am experiencing, step by step.” (002‐P‐030) |

| “I really have to thank the doctors and nurses who take care of me. They are my angels [gratitude to EPC team].” (002‐P‐045) | |

| “Something I'd like to say is thank you (…) to my wife [gratitude to caregivers], who gave me a great support.” (002‐P‐010) | |

| Spreading awareness on EPC | “It is essential to spread the culture of early palliative care [spreading awareness on EPC] that is now denied to most people.” (002‐C‐035) |

| “I wish this model could be taken as an example in other hospitals as well (…) [spreading awareness on EPC]. It is important, because oncology alone is not enough. When I realize that I am sick and I feel pain, every day, with no relief, it is as if I wish I could die. I am more prone to death itself than to life: EPC allows you to understand that it doesn't matter if you live one year or two or three years. You can live with quality. And this is missing. And I would like that even those who don't understand the importance of what has been done in this ambulatory could, eventually, understand it, and they could recognize the importance it deserves, on par with or beyond oncology [spreading awareness on EPC]. Because oncology is everywhere nowadays. I can be cured anywhere. But if it's not combined with this type of cure, it makes no sense. Oncology is pain, without EPC.” (002‐P‐003) | |

| “I want to tell everyone, even those who will come after me, that this unit is our salvation [spreading awareness on EPC].” (002‐P‐011) | |

| Positive thoughts and messages of hope | “I feel I'm lucky, compared with those who suddenly die, because I have had the chance to close, in my remaining time, several pending matters, which I would have continued to neglect if the disease had not hit me [positive thoughts].” (002‐P‐030) “These complementary treatments help me in increasing the hope to live a decent life [messages of hope].” (002‐P‐054) |

At the end of each quotation, the ID of the participant is reported: the first three numbers indicate the unit (001 for the Hematology Unit, Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Policlinico, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia Azienda Ospedaliera of Modena and 002 for the Oncology and Palliative Care Unit, Civil Hospital Carpi), the letter indicates patient (P) or caregiver (C), and the last three numbers indicate the recruitment progressive number).

Abbreviation: EPC, early palliative care.

Past

The main theme emerging from participants’ reports, when talking about their clinical experience prior to EPC, referred to physical symptoms as an unmet need, which heavily impacted on their Karnofsky Performance Status. Pain, due to either the standard therapy or the disease itself, was the most frequently reported symptom. A subtheme linked to the symptoms as unmet needs was its deleterious impact on patients’ physical functioning (including performance of daily activities), mood, and social life. The relationship between the symptoms and these three life spheres—physical functioning, mood, and social life—revealed a recurrent pattern in which physical functioning is impaired by symptoms, whereas mood and social life are impaired both by symptoms and by the inability to perform daily activities.

The most frequent reason for referral to the EPC unit was pain beyond an acceptable threshold. Some patients expressed regrets about not being informed earlier about the opportunity to control symptoms. A second reason for referral was the ineffectiveness of standard therapy.

Another element that emerged from caregivers’ reports was the deleterious psychological impact on caregivers themselves, caused by both seeing the beloved's suffering and being thrown into a difficult role that was unknown and unexpected.

See illustrative quotations in Table 2.

Present

The main emerging themes, when participants talked about their clinical experience on EPC, revolved around the perceived effects of such an intervention, its components, and the imperative need for this type of care by both patients with cancer and their caregivers.

Participants reported two distinct perceived effects. The first was related to the successful symptom management, which was appreciated and endorsed. Participants were astounded by the speed a problem that they had been suffering from, for such a long time, was solved. Symptom management restored physical functioning, mood, and social life, allowing patients to be back to their previous lives, a benefit that was often expressed metaphorically with a return from death to life. The second perceived effect, reported by participants, was empowerment. Empowerment included awareness, enhanced problem‐solving skills, and improved coping and was perceived by participants as the result of an established relationship with the palliative team, which succeeded in growing up with active and open listening, sincerity, and support. Compared with patients, caregivers were more focused on the future, even when talking about the present, and evaluated these two effects with a view to the end of life. Thus, they appreciated the effective symptom management in the perspective of a death without suffering and the empowerment in the perspective of a better, decent acceptance.

Components of the EPC that were highly appreciated by participants were the holistic approach, the focus on the person instead of the patient, and the environment. Interestingly, we also found other patients contributed to a positive and supportive environment, as highlighted by both patients and caregivers.

The theme about the need for the EPC by patients with cancer and caregivers was extremely prevalent among all participants. The importance of EPC was perceived to be discrete and complementary to the role of SC, but also as a “solo” treatment option, when SC is no longer effective.

See illustrative quotations in Table 3.

Future

The main emerging theme, when participants discussed the future, was the acceptance of the end of life. Although not all patients were comfortable with the idea of an impending and inevitable death, most of them highlighted an improved acceptance, as the result of either the awareness that death would be painless thanks to EPC or the deep relief from periodic conversations about the end of life with the palliative team. Moreover, these conversations represented the opportunity to be informed about the range of clinical options and most appropriate places for end‐of‐life care and, importantly, to be prepared for the end of life.

Caregivers’ acceptance seemed to be tied to their beloved's acceptance. Caregivers reported benefit from periodic conversations with the palliative team as well; however, the benefit seemed to be linked to the knowledge that they would not be alone, both in caring for the patient and after the patient's death.

See illustrative quotations in Table 4.

Open Question

The main emerging theme for both patients and caregivers, when responding to the open question, was gratitude. Gratitude was expressed toward the EPC model itself and, often, together with the hope that this model experience can be spread, as much as possible. Gratitude was also expressed to the palliative team and to the caregivers.

Participants also answered this question by describing positive thoughts and giving messages of hope. Interestingly, a caregiver highlighted how mere scientific knowledge is not enough to build up a satisfactory patient‐physician relationship: “Unfortunately, even scientific knowledge competence is not enough. An undisputed role in a successful relationship is played by empathy. In our past experience, we met doctors with high and excellent competences but without empathy. Palliative care provides both.” (002‐C‐001).

See illustrative quotations in Table 5.

Quantitative Analysis on Patients’ and Caregivers’ Perceptions

Descriptive statistics on patients’ and caregivers’ word categories are reported in Table 6.

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics of patients’ and caregivers’ word categories

| Word categories | Past | Present | Future | χ2(2) | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (%) | SD | Mean (%) | SD | Mean (%) | SD | |||

| Patients | ||||||||

| Positive affect | 0.45 | 1.76 | 1.11 | 1.83 | 1.55 | 2.57 | 14.598 | <.001 |

| Optimism | 0.27 | 1.36 | 0.81 | 1.52 | 0.82 | 1.27 | 12.876 | .002 |

| Negative affect | 7.58 | 9.33 | 3.15 | 2.76 | 4.73 | 4.97 | 20.456 | <.001 |

| Anxiety | 0.67 | 1.51 | 0.23 | 0.92 | 1.46 | 2.91 | 12.392 | .002 |

| Anger | 0.67 | 1.57 | 0.12 | 0.42 | 0.19 | 0.62 | 4.795 | .091 |

| Sadness | 1.71 | 3.65 | 0.75 | 1.38 | 2.32 | 2.77 | 11.789 | .003 |

| Causal thinking | 0.66 | 2.01 | 0.87 | 1.41 | 0.92 | 2.16 | 1.931 | .381 |

| Insight thinking | 1.21 | 2.83 | 2.41 | 3 | 2.59 | 2.76 | 16.363 | <.001 |

| Biological processes | 10.53 | 10.25 | 2.54 | 1.96 | 1.39 | 1.69 | 67.602 | <.001 |

| Agency | 4.57 | 3.9 | 7.36 | 4.53 | 4.1 | 3.31 | 13.981 | <.001 |

| Caregivers | ||||||||

| Positive affect | 0.06 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 2.77 | 0.55 | 1.28 | 10.293 | .006 |

| Optimism | 0.53 | 1.54 | 1.16 | 2.1 | 0.61 | 1.04 | 3.174 | .205 |

| Negative affect | 5.34 | 6.39 | 2.5 | 2.58 | 3.48 | 4.15 | 3.265 | .195 |

| Anxiety | 0.88 | 2.4 | 0.23 | 0.69 | 1.11 | 2.53 | 1.938 | .380 |

| Anger | 0.45 | 1.61 | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.16 | 0.77 | 0.500 | .779 |

| Sadness | 1.41 | 2.09 | 1.49 | 1.85 | 1.88 | 2.39 | 1.000 | .607 |

| Causal thinking | 2.45 | 7.02 | 0.98 | 1.56 | 0.84 | 1.75 | 0.792 | .673 |

| Insight thinking | 2.39 | 7.06 | 1.76 | 2.06 | 3.28 | 3.31 | 12.758 | .002 |

| Biological processes | .06 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 2.77 | 0.55 | 1.28 | 10.293 | .006 |

| Agency | 1.87 | 2.85 | 3.07 | 2.93 | 3.83 | 3.94 | 3.270 | .195 |

Past

When talking about the past, patients used more Negative Affects (e.g., pain, loneliness, problem) and Biological Processes words (e.g., medical, treatment, to eat, to sleep) than the present and the future (Negative Affects words: p < .001 and p = .006, respectively; Biological Processes words: p < .001 and p < .001, respectively).

Present

When talking about the present, patients used more Positive Affects (e.g., good, peaceful, reassurance) and Optimism words (e.g., improvement, hope, positive) than the past (p = .045 and p = .005, respectively). Compared with the past, there was also an increase in the use of Insight Thinking (e.g., how, thus, yet) and Agency words (e.g., I, my, me) (p = .004 and p = .009, respectively).

Caregivers used more Positive Affects words (p = .006) but also more Biological Processes words (p = .006) when talking about the present than the past.

Future

When talking about the future, patients’ use of Positive Affects, Optimism, and Insight Thinking words remained higher than the past (p < .001, p = .008, and p = .001, respectively). Compared with the present, there was an increase in the use of Anxiety (e.g., anxiety, frightened, terrible) and Sadness words (e.g., surrender, depression, emptiness) (p = .002 and p = .003, respectively), a further decrease in the use of Biological Processes words (p = .022), and a decrease in the use of Agency words (p = .003).

Caregivers used more Insight Thinking words when talking about the future than the past (p = .002).

Overall, the beginning of EPC introduced several changes in the patients’ reports: an increase in Positive Affects and Optimism words (Fig. 1A); a decrease in Negative Affects words (Fig. 1B); an increase in Anxiety and Sadness words, but only when talking about the future (Fig. 1B); an increase in Insight Thinking words (Fig. 1C); a decrease in Biological Processes words (Fig. 1D); and, finally, a temporary increase in Agency words when talking about the present but not the future (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1.

Trends in patients’ use of (A) Positive Affects and Optimism words, (B) Negative Affects, Anxiety, Anger, and Sadness words, (C) Causal Thinking and Insight Thinking words, (D) Biological Processes words, and (E) Agency words when talking about their past, present, and future. *, p < .01.

Discussion

In this study, patients and caregivers were asked to talk about their clinical experience prior to and during an EPC intervention and to describe possible changes in the perception and expectations of their future, including at the end of life, following the exposure to EPC.

A qualitative analysis of the most relevant and frequent emerging themes confirmed and extended the results from randomized trials by Maloney et al. [27] and Hannon et al. [3, 21]. Our study differed from these studies in that it was conducted with a wider and demographically different population, followed in the real‐life context of a standard practice of EPC. Moreover, the temporal perspective adopted in our study provides the first dynamic description of the benefits the patients can experience and the sequential changes in their thoughts and feelings, following an EPC intervention.

When referring to the clinical experience prior to EPC, patients reported being overwhelmed by unmanaged symptoms. Indeed, without a communication that enables symptom control, the benefits typical of EPC cannot be obtained [34]. The focus on the unmanaged symptoms is in keeping with study findings by Hannon et al. [3], who documented that participants reported the role of the standard oncologist as focused on the disease more than on symptom management. In our study, untreated symptoms, especially severe pain, emerged as the first and main trigger for cascading effects on physical functioning and performance of the daily routine (in the short term) and on mood and social life (later on), dragging patients in a downward spiral. Similarly to Hannon et al. [21], regrets about missed opportunities to have symptoms controlled before receiving the EPC were deep and recurrent. Consistent with this, 78.3% of our patients were referred to the EPC service later than 90 days from diagnosis. Despite calls for an integrated EPC, this still occurs late or not at all for many patients with cancer worldwide [2].

Caregivers were also impacted by these cascading effects, though with a different temporal sequence. Indeed, they experienced psychological issues in the short term and eventually an impact on physical functioning later on, mainly due to the burden of their responsibility. Thus, first‐instance interventions on caregivers should aim at decreasing the perceived burden of responsibility, by providing them practical resources and ad hoc training to face their new role, as highlighted by McDonald et al. [35] and Mohammed et al. [36].

When participants discussed the present, the most pervasive theme was related to the resolution of symptoms through the EPC. Accordingly, prompt symptom management was confirmed to be the major responsibility of PC physicians [3, 21]. This is in keeping with a previous study from our group [11], indicating an association between EPC and a significant reduction in pain severity and improvement in functional status, as early as in the first week, stressing the notion that an early integration of PC in the oncology wards may contribute to better cancer pain management. After a diagnosis of advanced cancer, the patient and caregiver face two challenges: a worsening of QoL, due to the effects of the disease and treatments, and the idea of death. Prompt symptom management limits the impact of these adverse effects, leading to a higher availability of psychological resources for coping with the new situation. By managing symptoms, the EPC improved functional status and served as a “bridge” to the discussion of psychological issues and the end of life [20].

Patients and caregivers also require empowerment to face an uncertain future. In that vein, a pervasive reported theme that emerged when discussing the present was empowerment as a consequence of EPC. A similar result was reported by the study by Maloney et al. [27], where participants perceived enhanced problem‐solving skills, better coping, feeling empowered, and feeling supported or reassured as benefits deriving from an EPC trial participation. An optimal relationship enabling the EPC team, the patient, and the caregiver to engage with one another enables empowerment and should be the ultimate goal, which may be realized only with a longstanding EPC intervention [37, 38, 39, 40]. Yoong et al. [25] found that in the EPC setting, discussion of psychosocial aspects of cancer was prominent throughout all EPC visits, compared with other physical needs that were addressed during the initial visits.

Both successful symptom management and empowerment were associated with the EPC holistic approach that emerged from participants’ reports as a plus of this intervention, together with the focus on the person and the environment. The holistic approach and the focus on the person were also identified as appreciated EPC components in the study from Hannon et al. [3, 21]. In addition, our participants reported the positive effects arising from the environment represented by the other patients and caregivers.

EPC was presented not only as a discrete and complementary intervention to SC, as in Hannon et al. [3], but also as a “solo” treatment, when SC was no longer effective, and as a care that can maximize the effects of the standard therapy. Only one patient reported to have had the initial perception of PC as a hopeless approach to the end‐of‐life comfort care, as found by Zimmermann et al. [41]. This might have been because participants were not asked specifically about their perception of the meaning of the term “palliative care” or because all were participating in the EPC service.

When asked to talk about the perception and expectations of their future, following the exposure to EPC, participants appreciated the opportunity for an increasing awareness and progressive acceptance of the idea of their end of life. This acceptance arose progressively from the perspective of a painless future and was developed further, following periodic conversations with the EPC team. None of the participants reported discomfort during conversations about their future and death. Instead, they were described as of utmost value and significance in building a deep and trusting relationship. Patients appreciated being able to discuss end‐of‐life issues openly and take the time they need to normalize a topic often described as “the elephant in the room” [42].

The quantitative analyses provided additional support to the themes revealed by the qualitative data and unveiled psychological processes that were prominent during the disease trajectory and EPC intervention. In patients’ reports on the past, there were significantly higher rates of words representing Negative Affects, which decreased and were replaced by Positive Affects and Optimism words once symptoms were controlled. The significantly higher use of words representing Biological Processes, when talking about the past, underlines how psychological resources are used and even wasted, in the attempt to overcome and survive symptoms, instead of being deployed to focus on empowerment and resilience. Several previous studies have found an association between negative affect and the ability to find benefits in negative experiences [43, 44].

When talking about their present, our participants were able to list positive aspects of their experience. Thus, being able to see things in a positive light might be a critical benefit of having a relationship with the EPC team [45]. Consistently, once symptoms were lessened, there was a significant increase in the use of Insight Thinking and Agency words. Agency words may reflect intentional causation, degree of autonomy, and manner of autonomy [46, 47]. Insight Thinking words have been associated with a drop in intrusive thinking about negative events [44] and are often observed together with Positive Affects words, representing a positive reappraisal of events that requires cognitive broadening [45].

Interestingly, when talking about the future, words associated with Agency, but not with Insight Thinking, decreased significantly. Moreover, the rate of Anxiety and Sadness words, but not Negative Affects words, increased. It is possible that the positive reappraisal of events continued, while contemplating the future, as shown by the use of the Insight Thinking words. Therefore, communication about the end of life might have led patients and caregivers to face inner, unavoidable feelings associated with the idea of death, representing a transition to acceptance.

Our study has important limitations. First, a control group of patients and caregivers who did not receive an integrated EPC intervention was absent. Second, the study generalizability is limited by the under‐representation of non‐White populations. Third, there is lack of data about personality differences among participants; however, no studies have considered the role of this variable in the context of EPC. Strengths of the study include the large number of the samples and the integrated use of qualitative and quantitative analyses of the language used by patients and caregivers on EPC, when talking about their clinical experience. The fact that this intervention represents a longstanding standard clinical practice may lend further credit to its feasibility as SC for patients with cancer.

Conclusion

Overall, our findings emphasize the benefits of a routine EPC intervention in the setting of advanced cancer. PC teams provide these benefits through a unique focus on whole‐person care, appropriate symptom management, and open communication. Audiotaping PC consultations in future studies can help to further elucidate the mechanisms by which EPC communication leads to improved coping and acceptance of the future. Importantly, to broaden the reach and impact of EPC for patients and their caregivers, we need more communication skills training for clinicians and policies focused on growing the EPC workforce [48, 49, 50].

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Eleonora Borelli, Sarah Bigi, Leonardo Potenza, Oreofe Odejide, Cristina Cacciari, Carlo Adolfo Porro, Camilla Zimmermann, Fabio Efficace, Eduardo Bruera, Mario Luppi, Elena Bandieri

Provision of study material or patients: Leonardo Potenza, Sonia Eliardo, Fabrizio Artioli, Claudia Mucciarini, Luca Cottafavi, Katia Cagossi, Giorgia Razzini, Massimiliano Cruciani, Alessandra Pietramaggiori, Valeria Fantuzzi, Laura Lombardo, Umberto Ferrari, Mario Luppi, Elena Bandieri

Collection and/or assembly of data: Eleonora Borelli, Leonardo Potenza, Sonia Eliardo, Fabrizio Artioli, Claudia Mucciarini, Luca Cottafavi, Katia Cagossi, Giorgia Razzini, Massimiliano Cruciani, Alessandra Pietramaggiori, Valeria Fantuzzi, Laura Lombardo, Umberto Ferrari, Vittorio Ganfi, Elena Bandieri

Data analysis and interpretation: Eleonora Borelli, Sarah Bigi, Leonardo Potenza, Fausta Lui, Oreofe Odejide, Cristina Cacciari, Carlo Adolfo Porro, Camilla Zimmermann, Fabio Efficace, Eduardo Bruera, Mario Luppi, Elena Bandieri

Manuscript writing: Eleonora Borelli, Sarah Bigi, Leonardo Potenza, Sonia Eliardo, Fabrizio Artioli, Claudia Mucciarini, Luca Cottafavi, Katia Cagossi, Giorgia Razzini, Massimiliano Cruciani, Alessandra Pietramaggiori, Valeria Fantuzzi, Laura Lombardo, Umberto Ferrari, Vittorio Ganfi, Fausta Lui, Oreofe Odejide, Cristina Cacciari, Carlo Adolfo Porro, Camilla Zimmermann, Fabio Efficace, Eduardo Bruera, Mario Luppi, Elena Bandieri

Final approval of manuscript: Eleonora Borelli, Sarah Bigi, Leonardo Potenza, Sonia Eliardo, Fabrizio Artioli, Claudia Mucciarini, Luca Cottafavi, Katia Cagossi, Giorgia Razzini, Massimiliano Cruciani, Alessandra Pietramaggiori, Valeria Fantuzzi, Laura Lombardo, Umberto Ferrari, Vittorio Ganfi, Fausta Lui, Oreofe Odejide, Cristina Cacciari, Carlo Adolfo Porro, Camilla Zimmermann, Fabio Efficace, Eduardo Bruera, Mario Luppi, Elena Bandieri

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

Supporting information

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Table S1 Questions of the semi structured interviews for patients and caregivers.

Table S2. LIWC's categories and subcategories analyzed in participants’ reports. Examples 6 are reported for each of them.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants to M.L. from the “Progetto di Eccellenza Dipartimento MIUR 2017”; the “Charity Dinner Initiative” in memory of Alberto Fontana for Associazione Italiana Lotta alle Leucemie, Linfoma e Mieloma (AIL) — Sezione ‘Luciano Pavarotti’ — Modena‐ONLUS; and the Fondazione IRIS CERAMICA GROUP.

Open Access Funding provided by Universita degli Studi di Modena e Reggio Emilia within the CRUI‐CARE Agreement.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Disclosures of potential conflicts of interest may be found at the end of this article.

References

- 1. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hui D, Bruera E. Models of palliative care delivery for patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:852–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hannon B, Swami N, Pope A et al. Early palliative care and its role in oncology: A qualitative study. The Oncologist 2016;21:1387–1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bandieri E, Sichetti D, Romero M et al. Impact of early access to a palliative/supportive care intervention on pain management in patients with cancer. Ann Oncol 2012;23:2016–2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. El‐Jawahri A, LeBlanc T, VanDusen H et al. Effect of inpatient palliative care on quality of life 2 weeks after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016;316:2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maltoni M, Scarpi E, Dall'Agata M et al. Systematic versus on‐demand early palliative care: Results from a multicentre, randomised clinical trial. Eur J Cancer 2016;65:61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vanbutsele G, Pardon K, Van Belle S et al. Effect of early and systematic integration of palliative care in patients with advanced cancer: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:394–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A cluster‐randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014;383:1721–1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S et al. Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non–small‐cell lung cancer: Results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:2319–2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Temel JS, Greer JA, El‐Jawahri A et al. Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung and GI cancer: A randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:834–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bandieri E, Banchelli F, Artioli F et al. Early versus delayed palliative/supportive care in advanced cancer: An observational study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2020;10:e32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Greer JA, Pirl WF, Jackson VA et al. Effect of early palliative care on chemotherapy use and end‐of‐life care in patients with metastatic non–small‐cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z et al. Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: Patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:1438–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alam S, Hannon B, Zimmermann C. Palliative care for family caregivers. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:926–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dionne‐Odom JN, Azuero A, Lyons KD et al. Benefits of early versus delayed palliative care to informal family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: Outcomes from the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:1446–1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. El‐Jawahri A, Greer JA, Pirl WF et al. Effects of early integrated palliative care on caregivers of patients with lung and gastrointestinal cancer: A randomized clinical trial. The Oncologist 2017;22:1528–1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McDonald J, Swami N, Hannon B et al. Impact of early palliative care on caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: Cluster randomised trial. Ann Oncol 2017;28:163–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. El‐Jawahri A, Traeger L, Greer JA et al. Effect of inpatient palliative care during hematopoietic stem‐cell transplant on psychological distress 6 months after transplant: Results of a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:3714–3721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. El‐Jawahri A, LeBlanc TW, Kavanaugh A et al. Effectiveness of integrated palliative and oncology care for patients with acute myeloid leukemia: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2021;7:238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Back AL, Park ER, Greer JA et al. Clinician roles in early integrated palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A qualitative study. J Palliat Med 2014;17:1244–1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hannon B, Swami N, Rodin G et al. Experiences of patients and caregivers with early palliative care: A qualitative study. Palliat Med 2017;31:72–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D et al. Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA 2016;316:2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thomas TH, Jackson VA, Carlson H et al. Communication differences between oncologists and palliative care clinicians: A qualitative analysis of early, integrated palliative care in patients with advanced cancer. J Palliat Med 2019;22:41–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zimmermann C, Riechelmann R, Krzyzanowska M et al. Effectiveness of specialized palliative care: A systematic review. JAMA 2008;299:1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yoong J, Park ER, Greer JA et al. Early palliative care in advanced lung cancer: A qualitative study. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:283–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT et al. Oncologists’ perspectives on concurrent palliative care in a National Cancer Institute‐designated comprehensive cancer center. Palliat Support Care 2013;11:415–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maloney C, Lyons KD, Li Z et al. Patient perspectives on participation in the ENABLE II randomized controlled trial of a concurrent oncology palliative care intervention: Benefits and burdens. Palliat Med 2013;27:375–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Corbin J, Strauss S. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. London: SAGE, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pennebaker JW, Booth RJ, Boyd RL et al. Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count: LIWC 2015. Austin, TX: Pennebaker Conglomerates Inc., 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tausczik YR, Pennebaker JW. The psychological meaning of words: LIWC and computerized text analysis methods. J Lang Soc Psychol 2010;29:24–54. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Konopasky AW, Sheridan KM. Towards a diagnostic toolkit for the language of agency. Mind Cult Act 2016;23:108–123. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vine V, Boyd RL, Pennebaker JW. Natural emotion vocabularies as windows on distress and well‐being. Nat Commun 2020;11:4525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Back AL. Patient‐clinician communication issues in palliative care for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:866–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McDonald J, Swami N, Pope A et al. Caregiver quality of life in advanced cancer: Qualitative results from a trial of early palliative care. Palliat Med 2018;32:69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mohammed S, Swami N, Pope A et al. “I didn't want to be in charge and yet I was”: Bereaved caregivers’ accounts of providing home care for family members with advanced cancer. Psychooncology 2018;27:1229–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: The integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:880–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hui D, Bansal S, Strasser F et al. Indicators of integration of oncology and palliative care programs: An international consensus. Ann Oncol 2015;26:1953–1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;302:741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S et al. Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:96–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M et al. Perceptions of palliative care among patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. CMAJ 2016;188:E217–E227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. El‐Jawahri A, LeBlanc TW, Burns LJ et al. What do transplant physicians think about palliative care? A national survey study. Cancer 2018;124:4556–4566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pennebaker JW, Chung CK. Expressive Writing: Connections to Physical and Mental Health. In: Friedman HS, ed. The Oxford Handbook of Health Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Affleck G, Tennen H. Construing benefits from adversity: Adaptational significance and dispositional underpinnings. J Pers 1996;64:899–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kleiner N, Zambrano SC, Eychmüller S et al. Early palliative care integration trial: Consultation content and interaction dynamics. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2021. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pacherie E. Sense of agency. In: Metcalfe J, Terrace HS, eds. Agency and Joint Attention. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013:321–346. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gallagher S. The natural philosophy of agency. Philos Compass 2007;2:347–357. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sedhom R, Gupta A, Roenn JV et al. The case for focused palliative care education in oncology training. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:2366–2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hui D, Bruera E. Models of palliative care delivery for patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:852–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Meier DE. Increased access to palliative care and hospice services: opportunities to improve value in health care. Milbank Q 2011. Sep;89:343–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Table S1 Questions of the semi structured interviews for patients and caregivers.

Table S2. LIWC's categories and subcategories analyzed in participants’ reports. Examples 6 are reported for each of them.