Abstract

Background

Trimethylamine N‐oxide (TMAO) is a gut microbiota‐dependent metabolite of dietary choline, L‐carnitine, and phosphatidylcholine‐rich foods. On the basis of experimental studies and patients with prevalent disease, elevated plasma TMAO may increase risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). TMAO is also renally cleared and may interact with and causally contribute to renal dysfunction. Yet, how serial TMAO levels relate to incident and recurrent ASCVD in community‐based populations and the potential mediating or modifying role of renal function are not established.

Methods and Results

We investigated associations of serial measures of plasma TMAO, assessed at baseline and 7 years, with incident and recurrent ASCVD in a community‐based cohort of 4131 (incident) and 1449 (recurrent) older US adults. TMAO was measured using stable isotope dilution liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (laboratory coefficient of variation, <6%). Incident ASCVD (myocardial infarction, fatal coronary heart disease, stroke, sudden cardiac death, or other atherosclerotic death) was centrally adjudicated using medical records. Risk was assessed by multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression, including time‐varying demographics, lifestyle factors, medical history, laboratory measures, and dietary habits. Potential mediating effects and interaction by estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) were assessed. During prospective follow‐up, 1766 incident and 897 recurrent ASCVD events occurred. After multivariable adjustment, higher levels of TMAO were associated with a higher risk of incident ASCVD, with extreme quintile hazard ratio (HR) compared with the lowest quintile=1.21 (95% CI, 1.02–1.42; P‐trend=0.029). This relationship appeared mediated or confounded by eGFR (eGFR‐adjusted HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.90–1.27), as well as modified by eGFR (P‐interaction <0.001). High levels of TMAO were associated with higher incidence of ASCVD in the presence of impaired renal function (eGFR <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2: HR, 1.56 [95% CI, 1.13–2.14]; P‐trend=0.007), but not normal or mildly reduced renal function (eGFR ≥60 mL/min per 1.73 m2: HR, 1.03 [95% CI, 0.85–1.25]; P‐trend=0.668). Among individuals with prior ASCVD, TMAO associated with higher risk of recurrent ASCVD (HR, 1.25 [95% CI, 1.01–1.56]; P‐trend=0.009), without significant modification by eGFR.

Conclusions

In this large community‐based cohort of older US adults, serial measures of TMAO were associated with higher risk of incident ASCVD, with apparent modification by presence of impaired renal function and with higher risk of recurrent ASCVD.

Keywords: animal food, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, renal function, trimethylamine N‐oxide

Subject Categories: Cardiovascular Disease, Diet and Nutrition, Epidemiology

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CHS

Cardiovascular Health Study

- TMAO

trimethylamine N‐oxide

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Long‐term elevated levels of trimethylamine N‐oxide were positively associated with increased incident atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in older US adults with impaired renal function or with documented atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Serial measurements of trimethylamine N‐oxide can be used as a marker of (recurrent) cardiovascular disease risk in those with impaired renal function or with prior atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

If these associations prove to be causal, trimethylamine N‐oxide could be targeted to reduce risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Trimethylamine N‐oxide (TMAO) is a gut microbiota‐dependent metabolite of dietary choline, L‐carnitine, and phosphatidylcholine‐rich animal foods (eg, red meat, eggs, fish, and poultry) and endogenously produced γ‐butyrobetaine and crotonobetaine. 1 , 2 , 3 TMAO, a small (75.1‐Dalton) amine compound, is cleared by the kidneys (>95% clearance in healthy individuals) 4 and, independently, causes renal damage and elevated cystatin C in animal models. 5 Experimental studies support a causal role of TMAO in development and progression of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) via multiple mechanisms, including decreased reverse cholesterol efflux, altered bile acid biosynthesis, increased accumulation of cholesterol in macrophages, foam cell formation in artery walls, stimulation of vascular inflammation, platelet aggregation and thrombosis, and renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis and dysfunction. 1 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 In humans, higher plasma TMAO levels have been associated with risk of ASCVD events 1 , 6 , 10 and chronic kidney disease. 5 , 11 , 12 , 13 However, such studies have generally been performed in patients with prevalent disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease) referred to tertiary medical centers, 10 , 11 , 12 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 where reverse causation and selection bias may be problematic. A relationship between plasma TMAO and incident or recurrent ASCVD in community‐based populations has not been established. In addition, given TMAO’s renal clearance and impacts on renal dysfunction, the potential mediating or modifying roles of renal function on these relationships are uncertain. Given the health burdens of ASCVD, accounting for 17.8 million annual deaths worldwide, 18 it is crucial to understand the potential interplay between TMAO, renal function, and incident and recurrent ASCVD, which may be leveraged for novel prevention and treatment efforts.

Plasma TMAO levels can also vary over time caused by shifts in dietary intake, microbiome composition, and/or metabolism. Yet, prior studies of clinical events used a single measurement of TMAO or change in TMAO at baseline, rather than serial measures with time‐varying updating, which reduces measurement error and misclassification over time. To address these key gaps in knowledge, we prospectively investigated the associations of serial measures of TMAO with incident and recurrent ASCVD in a community‐based population of older US adults, including the potential mediating or modifying role of renal function. We hypothesized that higher long‐term levels of TMAO would be associated with increased risk of incident and recurrent ASCVD, and the association would be modified by presence of impaired renal function.

Methods

Data, analytical methods, and study materials will not be made available to other researchers for the purpose of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure. The authors are not authorized to share CHS (Cardiovascular Health Study) data.

Study Population

The CHS is a prospective multicenter community‐based cohort study to identify risk factors and consequences of cardiovascular diseases in older adults. A total of 5888 participants were randomly selected and enrolled from Medicare eligibility lists in 4 US communities (Sacramento County, California; Washington County, Maryland; Forsyth County, North Carolina; and Allegheny County, Pennsylvania). Details of the study design and recruitment have been reported. 19 , 20 In brief, 5201 men and women were recruited in 1989 to 1990, with an additional 687 predominantly Black participants added in 1992 to 1993. Eligibility criteria included being aged ≥65 years, noninstitutionalized, expected to remain in their current community for >3 years, and not under active hospice or cancer treatment. Each center’s institutional review committee approved the study protocols, and all participants gave written informed consent. Participants were followed up by means of annual clinic visits through 1999 with interim 6‐month telephone contacts; and regular 6‐month telephone contacts thereafter. At each annual study visit, participants underwent comprehensive clinic examinations, including a standardized interview, physical examination, laboratory assessment, and diagnostic tests. Information on medical history, alcohol consumption, smoking, and other lifestyle risk factors was also regularly collected (see below). 19

Quantification of Plasma TMAO

Plasma TMAO concentrations were serially measured in all CHS participants with available stored blood samples at baseline (1989–1990 for the main cohort [n=4407; 84.7% of living participants]; 1992–1993 for the minority cohort [n=612; 89.1%]) and in 1996 to 1997 (n=3393; 76.9%). At these visits, 12‐hour fasting plasma blood samples were collected using EDTA tubes, and immediately processed and stored at −80 ℃ until analysis. Detailed description of quantification of plasma TMAO has been reported. 21 Briefly, we used stable isotope dilution liquid chromatography with online LC–MS/MS on a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (LCMS‐8050; Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner Research Institute using d9(trimethyl)TMAO as internal standards. TMAO and d9(trimethyl)TMAO were monitored using electrospray ionization in positive‐ion mode with multiple reaction monitoring of parent and characteristic daughter ion transitions: m/z 76→58 and 85→66, respectively. Laboratory coefficients of variation were <6% for TMAO at baseline and 1996 to 1997, lower than typical coefficients of variation (6.1%–15.6%) for TMAO measurements performed as part of multiplex ‘omics assays. 15 , 22 , 23 , 24

Ascertainment of ASCVD

Consistent with American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines, 25 ASCVD was defined as myocardial infarction (MI) (fatal and nonfatal), fatal coronary heart disease, stroke (fatal and nonfatal), sudden cardiac death, and other atherosclerotic death. The standardized CHS definitions of incident MI, stroke, and sudden cardiac death have been previously described in detail. 26 , 27 , 28 Incident ASCVD events were identified from annual clinic visits, interim 6‐month telephone contacts, hospital records, and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and National Death Index data; with centralized adjudication by committees of physicians using standardized criteria based on data from participants, proxy interviews, medical records, physician questionnaires, death certificates, medical examiner forms, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services hospitalizations, the National Death Index, and available brain imaging. 29

We followed up 4131 participants for incident ASCVD, after excluding 470 participants without TMAO measurements and 1287 participants with prevalent cardiovascular disease (prevalent angina, coronary revascularization, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke) at the time of their first TMAO measurement (Figure S1). We followed up 1449 participants for recurrent ASCVD, including 522 with prevalent angina or coronary revascularization at baseline (participants with nonfatal MI or nonfatal stroke at baseline were not followed up for recurrent nonfatal MI or stroke in CHS) and 927 who had experienced a new onset of angina, coronary revascularization, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke by 1996 to 1997 and who entered the analysis at that time point, and excluding 125 others without TMAO measures.

Covariates

At each annual visit, medical history was obtained, including smoking status (current, former, or never; lifetime pack‐years; and years since quitting in former smokers) and usual frequency and types of alcohol intake. Physical activity was assessed at baseline (1989–1990 or 1992–1993) and in 1996 to 1997 using a modified Minnesota Leisure‐Time Activities questionnaire. 30 Usual dietary habits were assessed in 1989 to 1990 31 using a 99‐item validated food frequency questionnaire (National Cancer Institute) and in 1996 to 1997 32 using a validated 131‐item food frequency questionnaire (Willet et al). 33 Fasting blood high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglyceride levels were measured using standardized methods, 34 , 35 with low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol calculated by Friedewald equation, excluding individuals with hypertriglyceridemia. CRP (C‐reactive protein) was measured by using a high‐sensitivity ELISA. 36 Serum creatinine was measured using a colorimetric method (Ektachem 700; Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) and calibrated to isotope dilution mass spectrometry. 37 Cystatin C was measured from frozen samples using a BNII nephelometer (Siemens, Deerfield, IL). 38 Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration creatinine–cystatin C equation that has greater precision and accuracy (calculated as the percentage of estimates that differed from measured eGFR) than equations based on creatinine or cystatin C alone. 39

Statistical Analysis

Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) of time to first (first recurrent) ASCVD event associated with TMAO. Time to censoring was derived as the earliest of death, lost to follow‐up, and June 30, 2015. The Cox proportional hazards assumption was evaluated using a test based on Schoenfeld residuals. 40 We found no evidence of violation of the proportional hazard assumption. To leverage serial TMAO measures and evaluate habitual exposure, we used time‐varying cumulative averaging: TMAO measures at baseline were related to risk of ASCVD until 1996 to 1997; and the average of levels at baseline and 1996 to 1997 to risk after 1996 to 1997. For participants with missing TMAO levels at the second time point (19.7%), baseline measurements were carried forward. For participants entering the analysis at the second time point for analyses of recurrent ASCVD, only the second TMAO measure was used, as the first TMAO measure occurred before their initial event. TMAO levels were evaluated categorically in quintiles as indicator variables, with quintile cut points based on cohort baseline measures. To assess linear trends, quintiles were assessed as linear variables after assigning participants the median value in each quintile.

To minimize potential confounding, we considered prespecified covariates based on biologic interest, risk factors for ASCVD in older adults, or associations with TMAO or ASCVD. Covariates included sex, race, enrollment site, education, income, and time‐varying risk factors, including age, self‐reported health status, smoking status, physical activity, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, prevalent diabetes mellitus, alcohol intake, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, CRP, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, use of lipid‐lowering medication, use of antihypertensive medication, use of antibiotics in the past 2 weeks of TMAO measurement, and habitual diet, including intakes of animal source foods (the sum of unprocessed red meat, processed meat, eggs, chicken, and fish), fruits, vegetables, and dietary fiber. We further adjusted for eGFR as a potential mediator or confounder. Missing covariate data (0.1%–19.5% at baseline; 1.7%–20.2% in 1996–1997) were imputed using multiple demographic and risk variables using single multivariable imputation, which prior analyses in CHS have shown produces similar results as multiple imputation. 41

Potential effect modification of the relationship between TMAO and ASCVD was explored for eGFR (≥60 or <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2) as well as age (≤71 or >71 years), sex (men/women), and BMI (kg/m2). Statistical significance of each multiplicative interaction term was assessed using the Wald test, with P values for these exploratory analyses. Bonferroni adjusted for multiple comparisons (α=0.05/4=0.0125). Potential nonlinear associations of log‐transformed TMAO with ASCVD were explored using restricted cubic splines. Sensitivity analyses were conducted: (1) excluding participants who had taken antibiotics in the 2 weeks before TMAO measurement; (2) excluding early events (within the first 2 years) to minimize any effect of preexisting subclinical disease leading to changes in TMAO levels; (3) excluding those who self‐reported their general health as poor at study entry; and (4) assessing the relationship between TMAO and ASCVD by simple updating (plasma TMAO levels at baseline were related to risk of ASCVD until 1996–1997, and plasma TMAO levels in 1996–1997 were related to risk of ASCVD after 1996–1997). Analyses used a 2‐tailed α of 0.05 and were performed using Stata 14.2 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

At baseline, mean (SD) age was 72.2 (5.3) years, 64% of participants were women, and 16% were black people race (Table 1). Most (80%) reported good, very good, or excellent general health, 40% were former smokers, and 12% were current smokers. Mean BMI (SD) was 26.7 (4.8) kg/m2, and 11% had prevalent diabetes mellitus. Only 3% had taken antibiotics within the prior 2 weeks. Among those with prevalent cardiovascular disease, most (73%) reported fair or poor general health and about two thirds (60%) were taking hypertension medication.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Older US Men and Women With Plasma TMAO Measurements in the CHS

| Characteristics | Participants free of prevalent cardiovascular disease (n=4131) | Participants with prevalent cardiovascular disease (n=1287) | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| TMAO, median (IQR), µmol/L | 4.72 (3.19–7.69) | 5.43 (3.57–8.74) | <0.001 |

| Demographics | |||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 72.2 (5.3) | 73.6 (5.8) | <0.001 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 2623 (64) | 603 (47) | <0.001 |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 3470 (84) | 1055 (82) | 0.087 |

| Education, n (%) | |||

| <High school | 1121 (27) | 427 (33) | 0.001 |

| High school | 1189 (29) | 338 (26) | |

| Some college | 959 (23) | 277 (22) | |

| College graduate | 862 (21) | 245 (19) | |

| Income group, n (%) | |||

| <$11 999 | 996 (24) | 374 (29) | <0.001 |

| $12 000–$24 999 | 1486 (36) | 483 (38) | |

| $25 000–$49 999 | 1106 (27) | 302 (23) | |

| >$50 000 | 543 (13) | 128 (10) | |

| Lifestyle and risk factors | |||

| Self‐reported health status, n (%) | |||

| Excellent/very good | 1751 (42) | 281 (22) | <0.001 |

| Good | 1562 (38) | 475 (37) | |

| Fair/poor | 818 (20) | 531 (41) | |

| Smoking, n (%) | |||

| Never smoked | 1979 (48) | 559 (43) | <0.001 |

| Former smoker | 1639 (40) | 595 (46) | |

| Current smoker | 513 (12) | 133 (10) | |

| Physical activity, mean (SD), kcal | 1150 (1533) | 1143 (1603) | 0.405 |

| Alcohol, mean (SD), drinks/wk | 1.1 (1.6) | 1.0 (1.5) | 0.003 |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 26.7 (4.8) | 26.8 (4.7) | 0.481 |

| Waist circumference, mean (SD), cm | 94.0 (13.5) | 96.1 (12.8) | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | 136 (21) | 137 (23) | 0.124 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | 71 (11) | 70 (12) | <0.001 |

| Biochemical variables | |||

| HDL cholesterol, mean (SD), mg/dL | 56 (16) | 50 (15) | <0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol, mean (SD), mg/dL | 130 (35) | 131 (36) | 0.163 |

| Triglycerides, mean (SD), mg/dL | 136 (72) | 148 (79) | <0.001 |

| CRP, median (IQR), mg/L | 2.4 (1.2–4.4) | 3.0 (1.5–5.6) | <0.001 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate, mean (SD), mL/min per 1.73 m2 † | 70.1 (16.2) | 63.8 (17.9) | <0.001 |

| Medical history, n (%) | |||

| Prevalent diabetes mellitus | 439 (11) | 167 (13) | 0.02 |

| Lipid‐lowering medication | 196 (5) | 115 (9) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension medication | 1649 (40) | 902 (70) | <0.001 |

| Antibiotics in past 2 wk | 116 (3) | 46 (4) | 0.12 |

| Dietary habits, mean (SD) | |||

| Fruits, servings/d | 2.1 (1.1) | 2.2 (1.0) | 0.216 |

| Vegetables, servings/d | 2.6 (1.4) | 2.4 (1.3) | 0.018 |

| Fiber, g/d | 29.3 (11.8) | 29.8 (12.4) | 0.683 |

| Total animal product, servings/wk ‡ | 1.7 (1.0) | 1.7 (1.0) | 0.503 |

Values represent mean (SD) for continuous variables and frequency (percentage) for categorical variables, unless otherwise stated. For analyses of incident cardiovascular disease, 3877 participants entered the study at baseline (1989–1990 for main cohort; 1992–1993 for minority cohort) and 254 participants entered in 1996 to 1997, the time of their first TMAO measure. BMI indicates body mass index; CHS, Cardiovascular Health Study; CRP, C‐reactive protein; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; IQR, interquartile range (25th–75th percentile); LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; and TMAO, trimethylamine N‐oxide.

For continuous variables, independent t‐test was performed; and for TMAO and CRP, Mann–Whitney U test was performed because of the distribution of data. For indicator variables, the χ 2 test was performed.

Estimated glomerular filtration rate (mL/min per 1.73 m2) is calculated on the basis of the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration creatinine–cystatin C equation. 39

Total animal source food is the sum of intakes of unprocessed red meat, processed meat, fish, chicken, and eggs.

The median (interquartile range) concentration of TMAO was 4.7 (3.2–7.7) µmol/L at baseline. In crude (unadjusted) analyses, participants with higher TMAO levels were more likely to be White race, report poor self‐reported health, have lower high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol and higher triglyceride levels, and be taking hypertension medication (Table S1). In addition, eGFR was lower, whereas dietary intake of total animal products was higher, in those with higher levels of TMAO. TMAO levels were not significantly associated with BMI, physical activity, alcohol consumption, blood pressure, or CRP. The Spearman correlation for repeated within‐individual measures of TMAO over 7 years (4 years for the minority cohort) was 0.254 (Table S2).

Plasma TMAO and Risk of Incident ASCVD

During 54 447 person‐years of follow‐up (median, 15 years; maximum, 26 years), 1766 ASCVD events occurred. After multivariable adjustment for ASCVD, demographics, and lifestyle risk factors, higher TMAO levels were positively associated with risk of incident ASCVD (extreme‐quintile HR [95% CI]: 1.21 [1.02–1.42]; P‐trend=0.029; Table 2). Further adjustment for dietary factors had little effect (HR [95% CI]: 1.21 [1.02–1.43]; P‐trend=0.028). In contrast, after additional adjustment for eGFR, which could be either a mediator or confounder of TMAO’s effects, the HR was attenuated, with an extreme quintile HR of 1.07 (95% CI, 0.90–1.27; P‐trend=0.516).

Table 2.

Risk of Incident ASCVD Associated With Long‐Term Levels of Plasma TMAO Among 4131 Older Adults in the CHS, Stratified by Renal Function

| Variable | Quintiles of plasma TMAO | P‐trend | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quintile 1 | Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 4 | Quintile 5 | ||

| Overall individuals (n=4131) | ||||||

| Median TMAO, µmol/L | 2.3 | 3.5 | 4.7 | 6.8 | 13.2 | |

| Cases/total | 251/826 | 324/827 | 408/825 | 426/827 | 357/826 | |

| Person‐years | 9587 | 11 217 | 11 589 | 12 092 | 9963 | |

| Age, sex adjusted | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.03 (0.87–1.21) | 1.20 (1.03–1.41) | 1.18 (1.01–1.38) | 1.22 (1.04–1.44) | 0.015 |

| Multivariable* | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.01 (0.86–1.19) | 1.21 (1.03–1.42) | 1.14 (0.97–1.33) | 1.21 (1.02–1.42) | 0.029 |

| Multivariable and diet † | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.01 (0.86–1.19) | 1.20 (1.03–1.41) | 1.13 (0.96–1.32) | 1.21 (1.02–1.43) | 0.028 |

| Multivariable, diet, and continuous eGFR (confounder or mediator) ‡ | 1.00 (Reference) | 0.97 (0.82–1.15) | 1.13 (0.96–1.33) | 1.03 (0.88–1.22) | 1.07 (0.90–1.27) | 0.516 |

| Individuals with eGFR <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (n=1104) | ||||||

| Median TMAO, µmol/L | 3.1 | 4.7 | 6.4 | 9.2 | 17.7 | |

| Cases/total | 67/220 | 99/221 | 109/221 | 103/222 | 115/220 | |

| Person‐years | 2124 | 2485 | 2336 | 2308 | 2135 | |

| Age, sex adjusted | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.12 (0.82–1.53) | 1.34 (0.99–1.82) | 1.27 (0.93–1.72) | 1.57 (1.16–2.13) | 0.003 |

| Multivariable* | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.16 (0.84–1.59) | 1.30 (0.95–1.77) | 1.25 (0.91–1.71) | 1.56 (1.13–2.14) | 0.007 |

| Multivariable and diet † | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.15 (0.84–1.58) | 1.27 (0.93–1.75) | 1.24 (0.90–1.70) | 1.53 (1.11–2.10) | 0.011 |

| Multivariable, diet, and continuous eGFR (confounder or mediator) ‡ | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.12 (0.82–1.55) | 1.22 (0.89–1.68) | 1.14 (0.83–1.58) | 1.37 (0.98–1.90) | 0.084 |

| Individuals with eGFR ≥60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (n=3027) | ||||||

| Median TMAO, µmol/L | 2.1 | 3.2 | 4.2 | 5.9 | 11.5 | |

| Cases/total | 181/604 | 233/607 | 296/606 | 307/605 | 256/605 | |

| Person‐years | 6804 | 8586 | 9326 | 9659 | 8684 | |

| Age, sex adjusted | 1.00 (Reference) | 0.92 (0.76–1.12) | 1.02 (0.85–1.23) | 1.02 (0.85–1.22) | 0.96 (0.79–1.16) | 0.836 |

| Multivariable* | 1.00 (Reference) | 0.95 (0.78–1.15) | 1.08 (0.89–1.30) | 1.05 (0.87–1.27) | 1.03 (0.85–1.25) | 0.668 |

| Multivariable and diet † | 1.00 (Reference) | 0.95 (0.78–1.16) | 1.08 (0.90–1.30) | 1.05 (0.87–1.26) | 1.03 (0.84–1.25) | 0.733 |

| Multivariable, diet, and continuous eGFR (confounder or mediator) ‡ | 1.00 (Reference) | 0.94 (0.77–1.14) | 1.05 (0.87–1.27) | 1.01 (0.84–1.23) | 0.98 (0.80–1.20) | 0.903 |

ASCVD indicates atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CHS, Cardiovascular Health Study; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; and TMAO, trimethylamine N‐oxide.

Multivariable adjustments include sex (men/women), race (White/black people), study site (Bowman Gray, Davis, Hopkins, or Pittsburgh), education (<high school, high school, some college, or college graduate), income (<$11 999, $12 000–$24 999, $25 000–$49 999, or >$50 000/y), and time‐varying risk factors, including age (65–74, 75–84, or ≥85 years), self‐reported health status (excellent, very good, or good/fair/poor), smoking status (never, former, or current), alcohol intake (0, <1, 1–2.49, 2.5–7.49, 7.5–14.49, or >14.5 drinks/wk), physical activity (<500, 500–1000, 1000–1500, or >1500 kcal/wk), body mass index (<18.5, 18.5–25, 25.1–30, or >30 kg/m2), waist circumference (cm), lipid‐lowering medication (yes/no), antihypertensive medication (yes/no), antibiotics (yes/no), prevalent diabetes mellitus (yes/no), high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL), low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL), triglycerides (mg/dL), CRP (C‐reactive protein) (mg/L), systolic blood pressure (mm Hg), and diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg).

Diet adjustments include fruits (servings/d), vegetables (servings/d), fiber (g/d), and total animal source food (servings/wk).

Further adjusted for eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2), given experimental evidence that TMAO causes renal dysfunction and reduced clearance. eGFR could represent a confounder or mediator (ie, in the causal pathway of effect) for the association between TMAO and ASCVD.

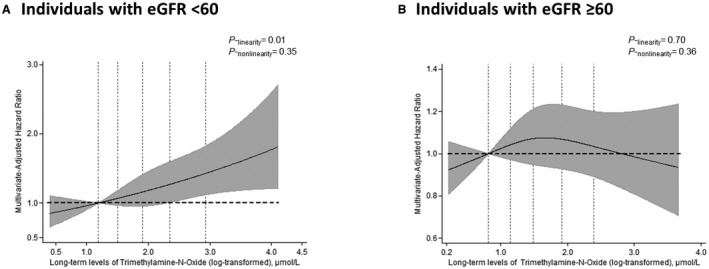

When stratified by baseline eGFR (≥60 or <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2), higher plasma TMAO was associated with higher incidence of ASCVD among individuals with impaired renal function (eGFR <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2) (extreme‐quintile HR [95% CI]: 1.56 [1.13–2.14]; P‐trend=0.007; Table 2), but not with normal or mildly reduced renal function (eGFR ≥60 mL/min per 1.73 m2) (HR [95% CI], 1.03 [0.85–1.25]; P‐trend=0.668). This interaction was statistically significant (P‐interaction <0.001). Further adjustment for eGFR attenuated the association in those with impaired renal function (HR [95% CI], 1.37 [0.98–1.90]; P‐trend=0.084). There was little evidence for differential associations between TMAO and incident ASCVD by age, sex, or BMI (Table S3). There was also little evidence for nonlinear associations between log‐transformed TMAO and ASCVD (Figure).

Figure 1. Multivariable‐adjusted relationship of long‐term levels of log‐transformed trimethylamine N‐oxide with risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease by renal function, with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (A) or eGFR ≥60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (B).

The solid lines and shaded area represent the central risk estimate and 95% CI, respectively. The dotted vertical lines correspond to the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentiles. The top and bottom 1% of participants were omitted as outliers to provide better visualization. P values for linear associations are presented. Evidence for nonlinearity was calculated by performing a likelihood ratio test between a multivariable model with all spline terms vs a multivariable model with only the linear term. Significant linearity was found in individuals with eGFR <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (P‐linearity=0.01). Estimates were adjusted for potential confounders (see the footnote in Table 2).

Plasma TMAO and Risk of Recurrent ASCVD

Among 1449 individuals with prevalent cardiovascular disease, a total of 897 recurrent ASCVD events occurred during 14 118 person‐years of follow‐up. After multivariable adjustment, plasma TMAO levels were associated with higher recurrence of ASCVD, with an extreme‐quintile HR of 1.25 (95% CI, 1.01–1.56; P‐trend=0.009; Table 3). Further adjustment for dietary factors did not appreciably alter these results. As seen for incident ASCVD, further adjustment for eGFR as a mediator or confounder attenuated the association (HR [95% CI], 1.10 [0.87–1.39]; P‐trend=0.179). No statistically significant effect modification was identified for the relationship between plasma TMAO and recurrent ASCVD by differences in eGFR (P‐interaction=0.021).

Table 3.

Risk of Recurrent ASCVD Associated With Long‐Term Levels of Plasma TMAO in the CHS Among 1449 Older Adults With Prevalent CVD at Baseline

| Variable | Quintiles of plasma TMAO | P‐trend | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quintile 1 | Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 4 | Quintile 5 | ||

| Median TMAO, µmol/L | 2.4 | 3.7 | 5.3 | 7.5 | 14.5 | |

| Cases/total | 156/291 | 178/288 | 181/290 | 191/290 | 191/290 | |

| Person‐years | 2767 | 2999 | 2998 | 2810 | 2544 | |

| Age, sex adjusted | 1.00 (Reference) | 0.98 (0.79–1.22) | 0.99 (0.80–1.23) | 1.09 (0.88–1.34) | 1.23 (1.00–1.53) | 0.012 |

| Multivariable* | 1.00 (Reference) | 0.98 (0.79–1.22) | 0.98 (0.79–1.22) | 1.07 (0.86–1.33) | 1.25 (1.01–1.56) | 0.009 |

| Multivariable and diet † | 1.00 (Reference) | 0.99 (0.80–1.23) | 0.99 (0.79–1.23) | 1.09 (0.88–1.36) | 1.26 (1.01–1.57) | 0.008 |

| Multivariable, diet, and continuous eGFR (confounder or mediator) ‡ | 1.00 (Reference) | 0.95 (0.76–1.18) | 0.93 (0.74–1.16) | 0.98 (0.78–1.23) | 1.10 (0.87–1.39) | 0.179 |

Included individuals with prevalent CVD, including angina or coronary revascularization, at baseline (n=522) and those who had a new onset of CVD (new angina, coronary revascularization, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke) between baseline and 1996 to 1997 and who entered the analysis in 1996 to 1997 (n=927). Individuals were followed up for recurrent ASCVD (myocardial infarction, fatal coronary heart disease, stroke, sudden cardiac death, or other atherosclerotic death), whichever occurred first. ASCVD indicates atherosclerotic CVD; CHS, Cardiovascular Health Study; CVD, cardiovascular disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; and TMAO, trimethylamine N‐oxide.

Multivariable adjustments include sex (male/female), race (White/black people), study site (Bowman Gray, Davis, Hopkins, or Pittsburgh), education (<high school, high school, some college, or college graduate), annual income (<$11 999, $12 000–$24 999, $25 000–$49 999, or >$50 000), and time‐varying risk factors, including age (65–74, 75–84, or ≥85 years), self‐reported health status (excellent, very good, or good/fair/poor), smoking status (never, former, or current), alcohol intake (0, <1, 1–2.49, 2.5–7.49, 7.5–14.49, or >14.5 drinks/wk), physical activity (<500, 500–1000, 1000–1500, or >1500 kcal/wk), body mass index (<18.5, 18.5–25, 25.1–30, or >30 kg/m2), waist circumference (cm), lipid‐lowering medication (yes/no), antihypertensive medication (yes/no), antibiotics (yes/no), prevalent diabetes mellitus (yes/no), high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL), low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL), triglycerides (mg/dL), CRP (C‐reactive protein) (mg/L), systolic blood pressure (mm Hg), and diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg).

Diet adjustments include fruits (servings/d), vegetables (servings/d), fiber (g/d), and total animal source food (servings/wk).

Further adjusted for eGFR (mL/min per 1.73 m2), given experimental evidence that TMAO causes renal dysfunction and reduced clearance. eGFR could represent a confounder or mediator (ie, in the causal pathway of effect) for the association between TMAO and ASCVD.

Sensitivity Analyses

Findings were similar excluding participants who had taken antibiotics in the past 2 weeks before the study entry, excluding early events in the first 2 years of follow‐up, excluding individuals with poor self‐reported general health, and using simple updated (recently measured) rather than cumulative updated TMAO levels (Tables S6 and S7).

Discussion

In this large, community‐based prospective cohort of older US adults, habitual levels of plasma TMAO were positively associated with incident ASCVD. This relationship was modified by renal function, with significantly higher risk only among individuals with impaired renal function (eGFR <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2), but not among those with normal or mildly reduced renal function (eGFR ≥60 mL/min per 1.73 m2). Plasma TMAO was also associated with higher risk of recurrent ASCVD. Renal function also appeared to be an important mediator or confounder of these relationships. To our knowledge, this is the first community‐based study to prospectively assess the associations of habitual levels of TMAO, a gut microbiota metabolite of certain animal source foods, with onset of ASCVD; and the first study to focus on older adults, the general population at highest risk.

TMAO is an intriguing molecule representing the interplay between diet, the microbiome, and endogenous metabolism. In humans, intestinal microbiota metabolize choline, phosphatidylcholine, and carnitine into trimethylamine, which is further oxidized by the liver to TMAO by hepatic flavin‐containing monooxygenase isoform 3. 42 Endogenously produced γ‐butyrobetaine and crotonobetaine, gut microbiota metabolites of L‐carnitine, are converted to trimethylamine and further oxidized to TMAO. 3 , 43 Mechanistic studies support proatherosclerotic effects of plasma TMAO, including experimental accumulation of cholesterol in macrophages and foam cell formation in artery walls by increasing cell surface expression of proatherogenic scavenger receptors (cluster of differentiation 36 and scavenger receptor A) 1 , 44 , 45 ; reduced reverse cholesterol efflux and bile acid biosynthesis 6 ; increased vascular inflammation via signaling of mitogen‐activated protein kinase and nuclear factor‐kB 8 , 46 ; and enhanced platelet reactivity and thrombosis via increased Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. 7 Together, these processes could collectively influence the development, incidence, and recurrence of clinical ASCVD.

In addition, plasma TMAO appears influenced by and to directly affect renal function. Experimentally, elevated plasma TMAO induces renal fibrosis, reduces renal filtration, and increases plasma cystatin C levels. 5 In a circular manner, impaired kidney function leads to higher levels of plasma TMAO and potentially greater atherosclerotic effects, 5 , 47 supported by findings from our present and prior observational studies 22 , 48 that plasma TMAO inversely associates with glomerular filtration rate (r=−0.62 to −0.31). The design of our investigation cannot disentangle the extent to which eGFR is a mediator or confounder of the association between plasma TMAO levels and incident or recurrent ASCVD. For example, it is possible that normal renal filtration of TMAO helps protect against adverse effects of its dietary‐microbiome production, clearing this molecule from the plasma before it can cause clinically relevant harm. Conversely, when renal function is reduced, higher plasma TMAO is not rapidly cleared, leading to increasing levels that both damage the cardiovascular system and reduce kidney function over time. Our novel results support the need for further investigation of the potential interplay between diet, the microbiome, renal function, and ASCVD in experimental and interventional models.

Our finding of a positive association between TMAO and recurrent ASCVD in this community‐based study is consistent with prior observational studies enrolling patients with preexisting cardiovascular disease seen at tertiary medical centers. 49 , 50 , 51 Mechanistic studies suggest that several pathways of risk for TMAO may be especially problematic among individuals with preexisting vascular disease. This includes, for example, induction by TMAO of platelet hyperresponsiveness and propensity for thrombosis in vivo 7 , 52 , 53 and promotion of vascular inflammation and upregulation of adhesion molecules in the artery wall. 8 , 54 Such effects would be most problematic in the presence of preexisting plaque and vascular disease (and distinct from other pathways that might promote early onset of atherosclerosis). In our investigation, risk was most evident among older adults with modestly reduced eGFR, and among those with preexisting ASCVD (independent of eGFR). These groups represent individuals with clinically evident vascular disease. Our results highlight the need for further experimental assessment of pathways of risk for TMAO among individuals with and without vascular disease.

Prior observational studies of TMAO and ASCVD events generally assessed referred patients with significant underlying health conditions (eg, coronary artery disease, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, and stroke) seen at tertiary medical centers. 17 , 49 , 50 , 51 Such patients would generally have lower eGFR and higher prevalent burdens of atherosclerosis, more similar to the participants in our study followed up for recurrent ASCVD. In 2 prior studies focused on patients with significantly impaired renal function (eg, stage 3b and 4 chronic kidney disease), 16 , 55 positive associations between a single baseline measure of TMAO and risk of all‐cause mortality or ischemic events were attenuated and no longer statistically significant after adjustment for eGFR. Our findings build on and extend these prior results by documenting a significant association between plasma TMAO and recurrent ASCVD, and among those with lower eGFR and incident ASCVD in a community‐based cohort. Our findings also suggest that healthier older adults with lower underlying burdens of atherosclerosis and renal dysfunction may not be similarly affected by plasma TMAO. A recent study among middle‐aged female US nurses found that changes (increases) in TMAO levels over time were associated with a higher risk of subsequent coronary heart disease. 14 This study did not report the association of baseline or habitual TMAO levels with coronary heart disease, nor present data on renal function. It seems possible that increasing TMAO levels in this study of nurses could represent, at least in part, worsening eGFR over time, given the interlinkages between plasma TMAO, renal function, and ASCVD seen in our investigation.

We documented a high within‐individual variability in plasma TMAO levels over 7 years (ρ=0.254), consistent with a prior small study among 100 German subjects over 1 year. 56 This raises the importance of using serial TMAO measures over time to facilitate the investigation of habitual or usual TMAO levels and health outcomes. TMAO levels are influenced by several factors, including consumption of animal products, abundance of trimethylamine‐producing bacteria in the gut, endogenous production of γ‐butyrobetaine and crotonobetaine, enhanced hepatic flavin‐containing monooxygenase isoform 3 enzyme activity, and impaired renal function. 57 Each of these factors also represents potential lifestyle and therapeutic targets to be evaluated in interventions to reduce the TMAO‐associated risk of ASCVD.

Our investigation has several strengths. We used repeated measures of plasma TMAO, reducing misclassification attributable to changes over time. The community‐based recruitment increases generalizability, whereas low loss to follow‐up reduces potential for selection bias. The large sample size and extended follow‐up provided a large number of events and statistical power to detect relevant associations. Information on a wide array of ASCVD risk factors, laboratory measures, demographic characteristics, and lifestyle habits was prospectively measured using standardized methods, 19 , 20 , 37 facilitating multivariable adjustment to reduce confounding. Both creatinine and cystatin C were measured, allowing direct calculation of eGFR. ASCVD outcomes were identified and confirmed by a comprehensive review and centralized adjudication process, reducing the potential for missed or misclassified outcomes.

Potential limitations should be considered. Our study population included older adults, mostly White race; thus, our findings may not be generalizable to younger populations or other races. Because of the observational nature of our study, residual confounding by unknown or unmeasured factors may be present. However, our results were robust to adjustment for multiple risk factors for ASCVD as well as demographics and dietary and other lifestyle habits. Data on factors associated with TMAO production, such as composition of gut microbiota and hepatic flavin‐containing monooxygenase isoform 3 activity, were not collected, which should be considered in future studies. Participants with nonfatal MI or nonfatal stroke at baseline were not followed up for recurrent nonfatal MI or stroke in CHS, which may influence the generalizability of the study result. About 20% of participants had missing TMAO levels at the second time point, for whom baseline measurements were carried forward. Although this may cause some misclassification of TMAO levels during follow‐up, 80% of participants did have serial measures, and our investigation represents by far the largest prospective study using serial measurements of TMAO over time to assess risk of ASCVD.

In conclusion, in this large, community‐based cohort of older US adults, serial measures of TMAO were associated with higher risk of incident ASCVD, with apparent modification by presence of impaired renal function; and with higher risk of recurrent ASCVD. Our findings highlight the need for further experimental and interventional studies to elucidate the interplay between TMAO, renal function, and incident and recurrent ASCVD.

Sources of Funding

The authors received support from the National Institutes of Health grants R01HL135920, P01 HL147823, and R01 HL103866 and a Leducq Foundation Award. CHS was supported by contracts HHSN268201200036C, HHSN268200800007C, HHSN268201800001C, N01HC55222, N01HC85079, N01HC85080, N01HC85081, N01HC85082, N01HC85083, N01HC85086, and grants U01HL080295 and U01HL130114 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, with additional contribution from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Additional support was provided by R01AG023629 from the National Institute on Aging. A full list of principal CHS investigators and institutions can be found at CHS‐NHLBI.org. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures

Dr Mozaffarian reports research funding from the National Institutes of Health, the Gates Foundation, and the Rockefeller Foundation; personal fees from GOED, Bunge, Indigo Agriculture, Motif FoodWorks, Amarin, Acasti Pharma, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, America's Test Kitchen, and Danone; participating on scientific advisory boards of start‐up companies focused on innovations for health, including Brightseed, DayTwo, Elysium Health, Filtricine, Foodome, HumanCo, and Tiny Organics; and chapter royalties from UpToDate. Drs Hazen and Wang report being named as coinventors on pending and issued patents held by the Cleveland Clinic relating to cardiovascular diagnostics and therapeutics. Dr Hazen also reports being a paid consultant for P&G and having received research funds from P&G and Roche Diagnostics; both Drs Hazen and Wang report being eligible to receive royalty payments for inventions or discoveries related to cardiovascular diagnostics or therapeutics from Cleveland HeartLab (a subsidiary of Quest Diagnostics) and P&G. Dr Psaty serves on the Steering Committee of the Yale Open Data Access Project funded by Johnson & Johnson.

Supporting information

Tables S1–S7

Figure S1

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e020646. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.120.020646.)

Supplementary Material for this article is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.120.020646

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 10.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wang Z, Klipfell E, Bennett BJ, Koeth R, Levison BS, DuGar B, Feldstein AE, Britt EB, Fu X, Chung Y‐M, et al. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2011;472:57–63. DOI: 10.1038/nature09922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang Z, Bergeron N, Levison BS, Li XS, Chiu S, Jia X, Koeth RA, Li L, Wu Y, Tang WHW, et al. Impact of chronic dietary red meat, white meat, or non‐meat protein on trimethylamine N‐oxide metabolism and renal excretion in healthy men and women. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:583–594. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Koeth RA, Levison BS, Culley MK, Buffa JA, Wang Z, Gregory JC, Org E, Wu Y, Li L, Smith JD, et al. Gamma‐butyrobetaine is a proatherogenic intermediate in gut microbial metabolism of L‐carnitine to TMAO. Cell Metab. 2014;20:799–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Al‐Waiz M, Mitchell SC, Idle JR, Smith RL. The metabolism of 14C‐labelled trimethylamine and its N‐oxide in man. Xenobiotica. 1987;17:551–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tang WH, Wang Z, Kennedy DJ, Wu Y, Buffa JA, Agatisa‐Boyle B, Li XS, Levison BS, Hazen SL. Gut microbiota‐dependent trimethylamine N‐oxide (TMAO) pathway contributes to both development of renal insufficiency and mortality risk in chronic kidney disease. Circ Res. 2015;116:448–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Koeth RA, Wang Z, Levison BS, Buffa JA, Org E, Sheehy BT, Britt EB, Fu X, Wu Y, Li L, et al. Intestinal microbiota metabolism of L‐carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2013;19:576–585. DOI: 10.1038/nm.3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhu W, Gregory JC, Org E, Buffa JA, Gupta N, Wang Z, Li L, Fu X, Wu Y, Mehrabian M, et al. Gut microbial metabolite TMAO enhances platelet hyperreactivity and thrombosis risk. Cell. 2016;165:111–124. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Seldin MM, Meng Y, Qi H, Zhu W, Wang Z, Hazen SL, Lusis AJ, Shih DM. Trimethylamine N‐oxide promotes vascular inflammation through signaling of mitogen‐activated protein kinase and nuclear factor‐κβ. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e002767. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gupta N, Buffa JA, Roberts AB, Sangwan N, Skye SM, Li L, Ho KJ, Varga J, DiDonato JA, Tang WHW, et al. Targeted inhibition of gut microbial trimethylamine N‐oxide production reduces renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis and functional impairment in a murine model of chronic kidney disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40:1239–1255. DOI: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.314139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tang WH, Wang Z, Levison BS, Koeth RA, Britt EB, Fu X, Wu Y, Hazen SL. Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1575–1584. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shafi T, Powe NR, Meyer TW, Hwang S, Hai X, Melamed ML, Banerjee T, Coresh J, Hostetter TH. Trimethylamine N‐oxide and cardiovascular events in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:321–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stubbs JR, House JA, Ocque AJ, Zhang S, Johnson C, Kimber C, Schmidt K, Gupta A, Wetmore JB, Nolin TD, et al. Serum trimethylamine‐N‐oxide is elevated in CKD and correlates with coronary atherosclerosis burden. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:305–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rhee EP, Clish CB, Ghorbani A, Larson MG, Elmariah S, McCabe E, Yang Q, Cheng S, Pierce K, Deik A, et al. A combined epidemiologic and metabolomic approach improves CKD prediction. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:1330–1338. DOI: 10.1681/ASN.2012101006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Heianza Y, Ma W, DiDonato JA, Sun Q, Rimm EB, Hu FB, Rexrode KM, Manson JE, Qi L. Long‐term changes in gut microbial metabolite trimethylamine N‐oxide and coronary heart disease risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:763–772. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.11.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stubbs JR, Stedman MR, Liu S, Long J, Franchetti Y, West RE 3rd, Prokopienko AJ, Mahnken JD, Chertow GM, Nolin TD. Trimethylamine N‐oxide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with ESKD receiving maintenance hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14:261–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim RB, Morse BL, Djurdjev O, Tang M, Muirhead N, Barrett B, Holmes DT, Madore F, Clase CM, Rigatto C, et al. Advanced chronic kidney disease populations have elevated trimethylamine N‐oxide levels associated with increased cardiovascular events. Kidney Int. 2016;89:1144–1152. DOI: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tang WH, Wang Z, Li XS, Fan Y, Li DS, Wu Y, Hazen SL. Increased trimethylamine N‐oxide portends high mortality risk independent of glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Chem. 2017;63:297–306. DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2016.263640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Global, regional, and national age‐sex‐specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1736–1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, Furberg CD, Gardin JM, Kronmal RA, Kuller LH, Manolio TA, Mittelmark MB, Newman A, et al. The cardiovascular health study: design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol. 1991;1:263–276. DOI: 10.1016/1047-2797(91)90005-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tell GS, Fried LP, Hermanson B, Manolio TA, Newman AB, Borhani NO. Recruitment of adults 65 years and older as participants in the cardiovascular health study. Ann Epidemiol. 1993;3:358–366. DOI: 10.1016/1047-2797(93)90062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang Z, Levison BS, Hazen JE, Donahue L, Li XM, Hazen SL. Measurement of trimethylamine‐N‐oxide by stable isotope dilution liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 2014;455:35–40. DOI: 10.1016/j.ab.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pelletier CC, Croyal M, Ene L, Aguesse A, Billon‐Crossouard S, Krempf M, Lemoine S, Guebre‐Egziabher F, Juillard L, Soulage CO. Elevation of trimethylamine‐N‐oxide in chronic kidney disease: contribution of decreased glomerular filtration rate. Toxins (Basel). 2019;11:635. DOI: 10.3390/toxins11110635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Meyer KA, Benton TZ, Bennett BJ, Jacobs DR Jr, Lloyd‐Jones DM, Gross MD, Carr JJ, Gordon‐Larsen P, Zeisel SH. Microbiota‐dependent metabolite trimethylamine N‐oxide and coronary artery calcium in the coronary artery risk development in young adults study (CARDIA). J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003970. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fu BC, Hullar MAJ, Randolph TW, Franke AA, Monroe KR, Cheng I, Wilkens LR, Shepherd JA, Madeleine MM, Le Marchand L, et al. Associations of plasma trimethylamine N‐oxide, choline, carnitine, and betaine with inflammatory and cardiometabolic risk biomarkers and the fecal microbiome in the multiethnic cohort adiposity phenotype study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;111:1226–1234. DOI: 10.1093/ajcn/nqaa015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Goff DC Jr, Lloyd‐Jones DM, Bennett G, Coady S, D'Agostino RB Sr, Gibbons R, Greenland P, Lackland DT, Levy D, O'Donnell CJ, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2935–2959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mozaffarian D. Fish and n‐3 fatty acids for the prevention of fatal coronary heart disease and sudden cardiac death. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:1991s–1996s. DOI: 10.1093/ajcn/87.6.1991S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mozaffarian D, Longstreth WT Jr, Lemaitre RN, Manolio TA, Kuller LH, Burke GL, Siscovick DS. Fish consumption and stroke risk in elderly individuals: the cardiovascular health study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:200–206. DOI: 10.1001/archinte.165.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fishman GI, Chugh SS, DiMarco JP, Albert CM, Anderson ME, Bonow RO, Buxton AE, Chen P‐S, Estes M, Jouven X, et al. Sudden cardiac death prediction and prevention: report from a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Heart Rhythm Society Workshop. Circulation. 2010;122:2335–2348. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.976092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ives DG, Fitzpatrick AL, Bild DE, Psaty BM, Kuller LH, Crowley PM, Cruise RG, Theroux S. Surveillance and ascertainment of cardiovascular events: the cardiovascular health study. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5:278–285. DOI: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)00093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Taylor HL, Jacobs DR Jr, Schucker B, Knudsen J, Leon AS, Debacker G. A questionnaire for the assessment of leisure time physical activities. J Chronic Dis. 1978;31:741–755. DOI: 10.1016/0021-9681(78)90058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kumanyika SK, Tell GS, Shemanski L, Martel J, Chinchilli VM. Dietary assessment using a picture‐sort approach. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65:1123s–1129s. DOI: 10.1093/ajcn/65.4.1123S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Feskanich D, Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Litin LB, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of food intake measurements from a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. J Am Diet Assoc. 1993;93:790–796. DOI: 10.1016/0002-8223(93)91754-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Willett WC, Sampson L, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Bain C, Witschi J, Hennekens CH, Speizer FE. Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;122:51–65. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497–509. DOI: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)64849-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lepage G, Roy CC. Direct transesterification of all classes of lipids in a one‐step reaction. J Lipid Res. 1986;27:114–120. DOI: 10.1016/S0022-2275(20)38861-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hussein AA, Gottdiener JS, Bartz TM, Sotoodehnia N, DeFilippi C, See V, Deo R, Siscovick D, Stein PK, Lloyd‐Jones D. Inflammation and sudden cardiac death in a community‐based population of older adults: the cardiovascular health study. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10:1425–1432. DOI: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cushman M, Cornell ES, Howard PR, Bovill EG, Tracy RP. Laboratory methods and quality assurance in the cardiovascular health study. Clin Chem. 1995;41:264–270. DOI: 10.1093/clinchem/41.2.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shlipak MG, Katz R, Kestenbaum B, Fried LF, Newman AB, Siscovick DS, Stevens L, Sarnak MJ. Rate of kidney function decline in older adults: a comparison using creatinine and cystatin C. Am J Nephrol. 2009;30:171–178. DOI: 10.1159/000212381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Inker LA, Schmid CH, Tighiouart H, Eckfeldt JH, Feldman HI, Greene T, Kusek JW, Manzi J, Van Lente F, Zhang YL, et al. Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:20–29. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1114248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81:515–526. DOI: 10.1093/biomet/81.3.515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Arnold AM, Kronmal RA. Multiple imputation of baseline data in the cardiovascular health study. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:74–84. DOI: 10.1093/aje/kwf156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Taesuwan S, Cho CE, Malysheva OV, Bender E, King JH, Yan J, Thalacker‐Mercer AE, Caudill MA. The metabolic fate of isotopically labeled trimethylamine‐N‐oxide (TMAO) in humans. J Nutr Biochem. 2017;45:77–82. DOI: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2017.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Koeth R, Culley M, Wang Z, Nemet I, Kirsop J, Org E, Buffa J, Li X, Levison B, Bartlett D, et al. Crotonobetaine is a proatherogenic gut microbiota metabolite of l‐carnitine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:14. DOI: 10.1016/S0735-1097(19)30623-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Febbraio M, Podrez EA, Smith JD, Hajjar DP, Hazen SL, Hoff HF, Sharma K, Silverstein RL. Targeted disruption of the class B scavenger receptor CD36 protects against atherosclerotic lesion development in mice. J Clin Investig. 2000;105:1049–1056. DOI: 10.1172/JCI9259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Suzuki H, Kurihara Y, Takeya M, Kamada N, Kataoka M, Jishage K, Ueda O, Sakaguchi H, Higashi T, Suzuki T, et al. A role for macrophage scavenger receptors in atherosclerosis and susceptibility to infection. Nature. 1997;386:292–296. DOI: 10.1038/386292a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chen ML, Zhu XH, Ran L, Lang HD, Yi L, Mi MT. Trimethylamine‐N‐oxide induces vascular inflammation by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome through the SIRT3‐SOD2‐mtROS signaling pathway. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e006347. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mueller DM, Allenspach M, Othman A, Saely CH, Muendlein A, Vonbank A, Drexel H, von Eckardstein A. Plasma levels of trimethylamine‐N‐oxide are confounded by impaired kidney function and poor metabolic control. Atherosclerosis. 2015;243:638–644. DOI: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.10.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Suzuki T, Heaney LM, Bhandari SS, Jones DJ, Ng LL. Trimethylamine N‐oxide and prognosis in acute heart failure. Heart. 2016;102:841–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tang WH, Wang Z, Fan Y, Levison B, Hazen JE, Donahue LM, Wu Y, Hazen SL. Prognostic value of elevated levels of intestinal microbe‐generated metabolite trimethylamine‐N‐oxide in patients with heart failure: refining the gut hypothesis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:1908–1914. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.02.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Senthong V, Wang Z, Li XS, Fan Y, Wu Y, Tang WH, Hazen SL. Intestinal microbiota‐generated metabolite trimethylamine‐N‐oxide and 5‐year mortality risk in stable coronary artery disease: the contributory role of intestinal microbiota in a courage‐like patient cohort. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e002816. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Haghikia A, Li XS, Liman TG, Bledau N, Schmidt D, Zimmermann F, Krankel N, Widera C, Sonnenschein K, Haghikia A, et al. Gut microbiota‐dependent trimethylamine N‐oxide predicts risk of cardiovascular events in patients with stroke and is related to proinflammatory monocytes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38:2225–2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Roberts AB, Gu X, Buffa JA, Hurd AG, Wang Z, Zhu W, Gupta N, Skye SM, Cody DB, Levison BS, et al. Development of a gut microbe‐targeted nonlethal therapeutic to inhibit thrombosis potential. Nat Med. 2018;24:1407–1417. DOI: 10.1038/s41591-018-0128-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Skye SM, Zhu W, Romano KA, Guo C‐J, Wang Z, Jia X, Kirsop J, Haag B, Lang JM, DiDonato JA, et al. Microbial transplantation with human gut commensals containing CuTC is sufficient to transmit enhanced platelet reactivity and thrombosis potential. Circ Res. 2018;123:1164–1176. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Boini KM, Hussain T, Li PL, Koka S. Trimethylamine‐N‐oxide instigates NLRP3 inflammasome activation and endothelial dysfunction. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;44:152–162. DOI: 10.1159/000484623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gruppen EG, Garcia E, Connelly MA, Jeyarajah EJ, Otvos JD, Bakker SJL, Dullaart RPF. Tmao is associated with mortality: impact of modestly impaired renal function. Sci Rep. 2017;7:13781. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-017-13739-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kühn T, Rohrmann S, Sookthai D, Johnson T, Katzke V, Kaaks R, von Eckardstein A, Müller D. Intra‐individual variation of plasma trimethylamine‐N‐oxide (TMAO), betaine and choline over 1 year. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2017;55:261–268. DOI: 10.1515/cclm-2016-0374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Velasquez MT, Ramezani A, Manal A, Raj DS. Trimethylamine N‐oxide: the good, the bad and the unknown. Toxins (Basel). 2016;8:326. DOI: 10.3390/toxins8110326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1–S7

Figure S1