Abstract

Avian coccidiosis is a major parasitic disorder in chickens resulting from the intracellular apicomplexan protozoa Eimeria that target the intestinal tract leading to a devastating disease. Eimeria life cycle is complex and consists of intra- and extracellular stages inducing a potent inflammatory response that results in tissue damage associated with oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation, diarrheal hemorrhage, poor growth, increased susceptibility to other disease agents, and in severe cases, mortality. Various anticoccidial drugs and vaccines have been used to prevent and control this disorder; however, many drawbacks have been reported. Drug residues concerning the consumers have directed research toward natural, safe, and effective alternative compounds. Phytochemical/herbal medicine is one of these natural alternatives to anticoccidial drugs, which is considered an attractive way to combat coccidiosis in compliance with the “anticoccidial chemical-free” regulations. The anticoccidial properties of several natural herbal products (or their extracts) have been reported. The effect of herbal additives on avian coccidiosis is based on diminishing the oocyst output through inhibition or impairment of the invasion, replication, and development of Eimeria species in the gut tissues of chickens; lowering oocyst counts due to the presence of phenolic compounds in herbal extracts which reacts with cytoplasmic membranes causing coccidial cell death; ameliorating the degree of intestinal lipid peroxidation; facilitating the repair of epithelial injuries; and decreasing the intestinal permeability induced by Eimeria species through the upregulation of epithelial turnover. This current review highlights the anticoccidial activity of several herbal products, and their other beneficial effects.

Key words: chicken, coccidiosis, control, Eimeria, herbs

INTRODUCTION

The poultry industry is under tremendous pressure due to parasitic disorders named “hidden enemies” as they gradually results in chronic losses without external symptoms. Annually, the poultry industry spends about £7.7 to £13.0 billion (at 2016 prices) in only seven countries on prophylaxis, treatment, and production losses due to avian coccidiosis (Blake et al., 2020). These losses are caused by seven Eimeria spp. The species grow in specific locations within the broiler digestive system (Blake et al., 2020).

Many factors facilitates the development of coccidiosis, including a direct life cycle, fecal-oral transmission, presence of resistant oocysts, absence of cross-protection between Eimeria species, high oocyst reproductive potential, high stocking density, and suitable environmental conditions for infectivity (sporulation). The most significant problem is the subclinical coccidiosis representing nearly three-quarters of the total economic costs. This is characterized by suboptimal flock performance due to increased feed intake and reduced body weight gain (BWG) (Remmal et al., 2011).

Several chemicals and ionophore anticoccidial feed additives have been used widely since 1939 to fight these parasites which are potentially dangerous for poultry (Nogueira et al., 2009). However, drug resistance has emerged (Abbas et al., 2011), and there are hazardous effects for consumers through drug residues in poultry products. Fortunately, the long-lasting and robust immunity produced by infections with Eimeria makes vaccination an effective alternative to anticoccidial drugs for control (Allen et al., 2005; Chapman et al., 2005). However, these vaccines can trigger severe hemorrhagic reactions or malabsorptive coccidiosis where poor management affects flocks' performance and uniformity (Chapman et al., 2002; Shirley et al., 2005).

Microbial infections negatively affect the production of poultry as they occupy the digestive system and have adverse effects on the final body weight, gut health, and meat quality of broiler (Abd El-Hack et al., 2021a; Swelum et al., 2021; Yaqoob et al., 2021). Therefore, antibiotics effectively suppressed and inhibited bacteria until the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (Alagawany et al., 2021a,b; Reda et al., 2021). The tendency to use phytogenic compounds solves this problem, such as phenolic compounds in herbal extracts (Abou-Kassem et al., 2021; El-Saadony et al., 2021a; Saad et al., 2021a,b). In addition, peptides and essential oils also act as a powerful antimicrobial agent against Gram negative and/or Gram positive bacteria (El-Saadony et al., 2020, 2021b,c; Saad et al., 2020, 2021c; El-Tarabily et al., 2021). The antimicrobial mechanism of these compounds is represented in their electrostatic interaction with specific compounds in the bacterial cell wall, which disrupted and allowed the additives' entry and changes the behavior of DNA in the bacterial cell causing cell death (Abd El-Hack et al., 2021b,c,d).

Recently there is an international interest in using herbal products as safe alternatives to control various diseases with a lower risk of resistance development (Abd El-Hack et al., 2020a,b; Abdelnour et al., 2020; Ashour et al., 2020). Over 1200 plants had been reported to have antiprotozoal activity (Willcox and Bodeker, 2004; Muthamilselvan et al., 2016). Some of these herbal remedies are used in poultry diets due to their growth-promoting and natural immuno-stimulating effects.

This review discusses the etiology, factors affecting the clinical outcomes of poultry coccidiosis as well as the up-to-date known different types of herbal medicine of coccidiosis, and highlights their beneficial effects to pay much more attention for their use in the poultry industry.

ETIOLOGY OF POULTRY COCCIDIOSIS

Poultry coccidiosis affects all domestic and wild bird species and is caused by the protozoan Eimeria (phylum Apicomplexa). The protozoa replicates with a 4 to 6-d fecal-oral life cycle depending on species (Figure 1). Their replication includes both asexual (merogony or schizogony) and sexual (gametogenic) stages inside the host's intestinal cells, during which high numbers of oocysts are produced. The oocysts are then excreted with feces, sporulate in the environment, and become infective. Inside each oocyst are four sporocysts, each including 2 sporozoites (Shirley et al., 2005).

Figure 1.

Eimeria life cycle. Birds get infected by fecal matter, and the protozoan reproduction occurs in the intestinal cells, resulting in damage to the intestinal wall.

Seven Eimeria species are the most precious parasites infecting ∼60 billion chickens annually worldwide; E. acervulina, E. maxima, E. brunette, E. praecox, E. mitis, E. tenella, and E. necatrix, each with variable pathogenicity (Shirley et al., 2005) (Table 1).

Table 1.

The degree of pathogenicity and immunization of avian Eimeria species.

| Species | Localization in the intestine | Pathogenicity* | Immunization⁎⁎ | No. of exposure (life cycles) to achieve immunity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. acervulina | Duodenum, jejunum | ++ | ++ | 2-3 |

| E. maxima | Duodenum, jejunum, ileum | ++ | +++ | 1 |

| E. brunetti | Ileum, rectum | +++ | +++ | 1-2 |

| E. tenella | Caeca | ++++ | + | 3-4 |

| E. necatrix | Jejunum, caeca | ++++ | + | 4-5 |

| E. praecox | Duodenum, jejunum | + | +++ | 1 |

| E. mitis | Duodenum, jejunum | + | ++ | 2-3 |

+ low pathogenic; ++ moderately pathogenic; +++ moderately to highly pathogenic; ++++ highly pathogenic.

+ low immunogenic; ++ moderately immunogenic; +++ highly immunogenic.

Concurrent infection with at least 6 species is widespread in a single flock causing independent, distinct, and recognizable diseases leading to the subclinical enteric infection to sub-acute mortality (McDougald, 2003).

FACTORS AFFECTING THE OUTCOME OF COCCIDIOSIS INFECTION

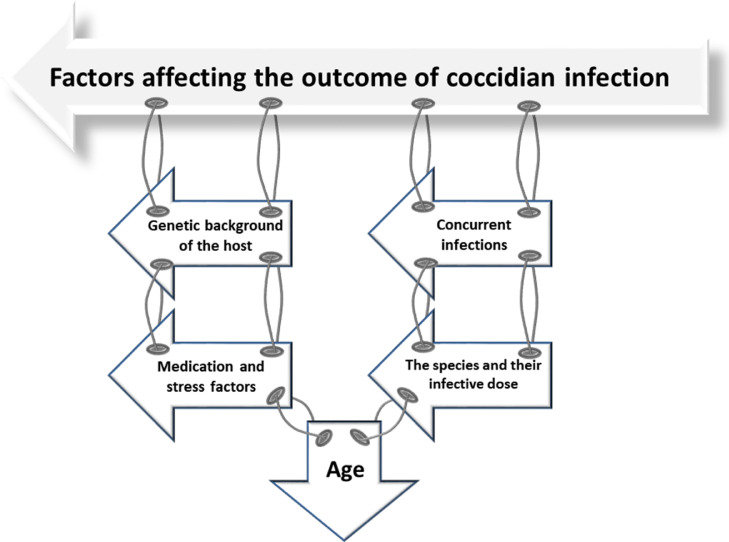

Factors affecting the outcome of coccidiosis infection are discussed below and illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Factors affecting the outcome of coccidian infection.

Effect of Age on the Outcome of Infection

Many studies reported that infection prevalence increased among the younger chicks (McDougald, 2003), while older chickens were relatively resistant to infection (Lillehoj, 1998). Gardiner (1955) demonstrated that chicks at 4-wk old are more susceptible to cecal coccidiosis, while at 2-wk old, they are more resistant than at any other time during the first 6 wk, which may be due to the difference in inherent resistance of the host, or variations in the virulence of the inocula used.

Most Eimeria species affects birds between 3 and 18 wk age; however, higher mortality rates appeared obviously in young chicks (Razmi and Kalideri, 2000; Al-Natour et al., 2002). The incidence of caecal coccidiosis in White Leghorn chickens was found to be 69% in chickens <45-d old and 29.58% >20-wk old. Bachaya et al. (2012) showed a high infection rate among younger chicks (60%) compared to older chickens (37%). Ola-Fadunsin (2017) reported a 52.7% of young birds and 21.1% of adult (sexually mature) birds were positive for coccidiosis. Subclinical coccidiosis was more frequently found >4 to 5 wk in broilers (Razmi and Kalideri, 2000).

Genetic Background of the Host

The chickens' genetic background influences the development of the parasites, affects BWG and the severity of lesions and is potentially correlated with immunity to infection (Clare et al., 1985). For instance, the susceptibility to coccidiosis was observed frequently in layers more than in broilers (Williams and Catchpole, 2000). Lillehoj et al., (1986) showed that different lines of chickens displayed a different susceptibility to the same Eimeria infections as shown by oocyst production, lesion score, and clinical signs.

Inbred lines of chickens (such as White Leghorn) have a high resistance to infection to specific Eimeria species but showed lower infection resistance with other species (Bumstead and Millard, 1992). Lee et al. (2016) compared the resistance of congenic Fayoumi lines to E. tenella infestation and additionally they evaluated the genetic differences regarding Eimeria egression. Chickens were inoculated orally with 5 × 104 E. tenella sporulated oocysts then challenged on the 10th d with 5 × 106 oocysts. The Fayoumi M5.1 line had higher BW gain, lower oocyst shedding, and a higher ratio of B and CD4 (+)/CD8 (+) T cells than the M15.2 chickens. These results suggest that the M5.1 line is least susceptible to E. tenella infection than the M15.2 line.

Additionally, the percentage of sporozoite released from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in the M5.1 line was higher. This suggests that promoted resistance of Fayoumi M5.1 to E. tenella infestation may involve an adaptive immunity resulting in reduced intracellular progress of Eimeria spp. (Lee et al., 2016).

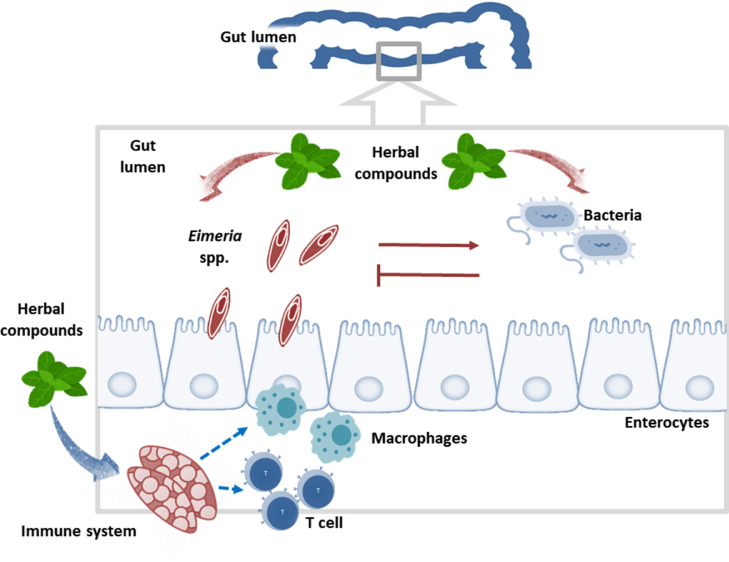

The schematic process of immune response of chickens to herbal anticoccidian compounds is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Gut-associated T cells, macrophages, and the schematic process of immune response of chickens to herbal anticoccidian compounds.

Flock Size and Season

Large farms need more water, feed, litter, and generate higher amounts of feces so that they might act as a potential source of subclinical coccidiosis infection (Razmi and Kalideri, 2000). The prevalence of clinical or subclinical coccidiosis in broilers during spring and winter was higher than in autumn and summer (Razmi and Kalideri, 2000) due to oocysts' survival. Sporulation favors high humidity in litter and increases oocysts spread in chicken farms (Jordan, 1996). Coccidiosis had a low presence in winter (20.29%), while it was most prevalent in autumn at 45.12%, followed by summer (30.84%) and spring (23.81%) (Ahad et al., 2015).

Awais and Akhtar (2012) also recorded the incidence of disease was notably higher in autumn (60.02%) than summer (47.42%), spring (36.92%), and winter (29.89%). The rate and degree of sporulation of released oocysts are crucial factors affecting the infection rate in a flock, influencing the infection's epidemiology. Relative ambient temperature and humidity might be responsible for sporulation and affect the disease's incidence in different seasons (Awais and Akhtar, 2012).

The Species Involved and Their Infective Dose

The severity of infection caused by avian coccidiosis is directly related to the parasite species, the particular isolate or strain involved, and the number of oocysts ingested (Dakpogan et al., 2012). Using a single oocyst isolation technique; variable virulence was obtained from 4 E. tenella strains (Beheira, Kafr El-Sheikh, Gharbia, and Alexandria) from a dose of 25 × 103 oocysts/chick at 2-wk old (Sedeik et al., 2019). The Alexandria strain was the most virulent (60 % mortality and showed a significant reduction in weight gain), while the Beheira strain was second (33.33 % mortality). The Kafr El-Sheikh and Gharbia strains had no mortality. The clinical manifestations of coccidiosis are related to many infective oocysts to which susceptible birds are exposed in their first month (Martins et al., 2012).

The crowding effect means that a maximum infective dose exists, after which the reproductive potency decreases (Williams, 2001). El-Shall (2015) recorded 34.48 and 60% mortality from inoculation of 2-wk old chicks with E. tenella Alex strain using doses of 104 and 25 × 103 oocysts/chick, while E. tenella Behera stain resulted in 0 and 33.33% mortality using doses of 104 and 25 × 103 oocysts/chick. The intensive breeding system is a precious factor in propagating coccidiosis disease (Badran and Lukesova, 2006).

Medications and Other Stress Factors

Suboptimal inclusion or extensive use of anticoccidials in feed creates resistance and poor litter management. The absence of litter disposal and inadequate sterilization could provide optimal temperature (24–28°C) and relative humidity (exceeding 30%) for sporulation of oocysts (Chanie et al., 2009).

The key factors in the epidemiology of coccidiosis are the presence of sporulated oocysts in the environment for long period, bad ventilation, the absence of all-in all-out system, and other stressors (i.e., dietary changes, and immunosuppressive effects) are all possible risk factors associated with the outbreak of coccidiosis (Chanie et al., 2009).

Awadalla (1998) studied the effect of stressors like vaccination and crowding on the pathogenicity of E. tenella in broiler chickens. Each chick was inoculated with 104 sporulated E. tenella oocysts at 3-d old, followed by a challenge with a further 15 × 103 sporulated oocysts on d 28. The results revealed that overstocking chickens elevated corticosterone levels and lowered total proteins, calcium, glucose, and phosphorus levels. The crowded vaccinated group had the highest mortality, oocysts production, caecal indices, and the lowest body, spleen, bursa, and thymus weight (Awadalla, 1998).

In chickens, aflatoxins in the diet act as a precious stress factor, increasing the severity or susceptibility to caecal coccidiosis, inducing impairment of cellular and humoral immune responses resulting in lower resistance to serious infectious diseases including coccidiosis (Bakshi et al., 2000). Shakshouk et al. (1990) reported that aflatoxins at 5 ppm in the feed ration for 2 wk, followed by 2.5 ppm for a further 2 wk, increased the susceptibility of chickens to caecal coccidiosis with 20 × 103 sporulated oocysts/bird. Aflatoxins (200 ppb) in the diet of broiler chickens increased the mortality caused by E. tenella infection and results in a significant loss in BW and a deteriorated food conversion ratio (FCR) in survivors (Allameh et al., 2005; Ellakany et al., 2011).

The effect of heat stress on the pathogenesis of Eimeria maxima in meat‐type chickens was studied by Schneiders et al. (2020), who demonstrated a significant detrimental effect of heat stress on the pathogenesis of E. maxima infection in broilers. They reported a restrictive replication of the parasite in heat-stressed chickens evidenced by significantly reduced oocyst shedding and disruption of the intestinal blood barrier. In addition, there was downregulation of Eimeria species genes related to gamete fusion, oocyst shedding, mitosis, and spermiogenesis which led to the alterations in the cytokine expression that could be related to reduce parasite development in vivo during the exposure to heat stress (Schneiders et al., 2020).

Impact of Routine Vaccines and Concurrent Infections on Susceptibility to Coccidiosis

The clinical signs of Eimeria infection are enhanced by simultaneous infection with several species and interactions with other pathogens such as enteric bacteria and viruses. Coccidia-free chickens exhibit no difference in innate susceptibility to coccidiosis according to age (Pellérdy, 1974). Therefore, exogenous factors that have an immunosuppressive effects such as Marek's disease virus (Rice and Reid, 1973), reticuloendothelial virus (Motha and Egerton, 1984), and reovirus (Ruff and Rosenberger, 1985a,b), increases susceptibility to coccidiosis.

Vaccinations can also increase susceptibility to coccidiosis. For example, the infectious bursal disease (IBD) vaccination increased the severity of caecal coccidiosis due to immunosuppression (McDougald et al., 1979). However, Kabell et al. (2006) showed that coccidiosis did not affect IBD vaccination of chickens, suggesting the promoting effect of concurrent stimulation of the immune system by subclinical coccidiosis and the very virulent infectious bursal disease virus (vvIBDv), activating the distribution, and replication of the vaccine strain in chicken lymphoid tissues (Kabell et al., 2006).

Chickens infected with E. tenella, before and after vaccination with the lentogenic F or the mesogenic Komaroff vaccine strains of Newcastle disease virus (NDV), had significantly lower HI antibody titers and higher mortality after challenge with velogenic strains of NDV suggesting the immunosuppressive effect of E. tenella infection to NDV vaccine response (Mohammed, 1980,1982; Hegazy et al., 1986). Furthermore, coccidiosis incubation and latent disease conditions are known to be hastened and aggravated by NDV vaccination (Anonymous, 1986).

Obasi et al. (2006) reported a natural outbreak in Nigeria of acute coccidiosis in a flock of 250 broilers with 33% mortality over 4 d, which was considered to be induced by NDV vaccination. In disease outbreaks (with field exposure to NDV) on the farm (with subclinical coccidiosis) and with a higher infectious dose and involvement with more virulent strains of NDV, a more severe, sudden, and acute clinical disease (caecal coccidiosis) is expected (Shaban, 2012).

Various laboratory trials suggest that coccidiosis may predispose birds to necrotic enteritis (NE), such as E. acervulina (Shane et al., 1985), E. maxima (Williams et al., 2003), or E. necatrix (Baba et al., 1997). Coccidiosis promotes the onset of NE by supporting Clostridium perfringens growth by inducing the inflammatory reaction, increasing mucous secretions (goblet cells), which is a growth factor for C. perfringens (Collier et al., 2008). However, many coccidiosis cases recorded worldwide without being associated with NE (Kaldhusdal et al., 2001; Répérant and Humbert, 2002).

It is suggested that only severe coccidiosis damages the mucous membrane enough to allow a clostridial infection leading to NE. In addition, the threshold of clostridial infection is necessary for NE to become prominent (Williams, 2005). When Eimeria invasion occurs before Salmonella infection in chickens, there is a more severe and prolonged salmonellosis. The same results were reported in a study with S. typhimurium/E. necatrix (Stephens and Vestal, 1966), S. typhimurium/E. tenella, and S. entritidis/E. tenella (Koinarski et al., 2005). These findings can be explained based on the protozoa's invasive nature against the intestinal epithelium, as they easily bind to parenchymal organs, and allows Salmonella propagation in these organs (Koinarski et al., 2005). It was also noted that infestation with E. tenella increased the severity of Histomonas meleagridis infection in chickens (McDougald and Hu, 2001).

The occurrence of concurrent coccidiosis and mycoplasmosis in chickens starting from 7 wk old in 50% of samples and with colibacillosis in 4 to 6 wk old in 43.33% of samples, while sole infection with coccidiosis was in 37.5% of samples. This indicated that concurrent coccidiosis significantly affects the productivity and health status of birds (Chanie et al., 2009).

PHYTOCHEMICAL (HERBAL) REMEDIES FOR AVIAN COCCIDIOSIS

Prolonged use of anticoccidial chemicals promotes drug resistance and results in tissue residues in chickens; therefore, a healthy anticoccidial treatment based on herbs is important.

Different phytochemical/herbal remedies and/or their extracts; bioactive compounds; specific anticoccidial properties and their effects exerted on poultry and the studied coccidian species are discussed in Table 2. In addition, different herbal mixtures and their bioactive compounds; specific anticoccidial properties and their effects on different coccidian species are also presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

Different phytochemical/herbal remedies and/or their extracts; bioactive compounds; specific anticoccidial properties and their effects exerted on poultry and the studied coccidian species.

| Herbs | Bioactive compounds | Specific anticoccidial effects exerted in poultry | Studied coccidian species | Other beneficial effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acacia concinna | Saponins | Binds to the 4-sterol molecules on Eimeria cell membrane, as they disturbes the lipids in the parasite cell membrane. This affects the enzymatic activity and metabolism leading to cell death. Cell death then induces a toxic effect in mature enterocytes in the intestinal mucosa, causing sporozoite-infected cells to be released before the merozoite phase of the protozoa. | Eimeria tenella, Eimeria acervulina and Eimeria maxima | Enhances the nonspecific immunity. Improves the productive performance (daily body weight gain and reduces feed conversion ratio. Reduces the mortality rate. Decreases the fecal oocyst shedding. Reduces ammonia production. | (Wang et al., 1998; Cheeke, 2000; Alfaro et al., 2007). |

|

Allium sativum (Garlic) Allium tripedale (Nectaroscordum tripedale) |

Sulfur derivatives, allicin, alliin, ajoene, diallyl sulfide, dithiin, and allylcysteine | Hinder sporulation. However, the full anticoccidial mechanism of garlic and its sulfur derivatives are still ambiguous. | Eimeria tenella | Shows broad antimicrobial activity that reduces the deleterious effects of microbial infections. | (El-Khtam et al., 2014; Pourali et al., 2014; Alnassan et al., 2015; Habibi et al., 2016; Udo and Abba, 2018; Ali et al., 2019; Sidiropoulou et al., 2020). |

| Propylthiosulfinate (PTS) and propylthiosulfinate oxide (PTSO) | - | - | Modulates the intestinal immunity through expression levels of 1227 intestinal lymphocytes. Stimulates the NF-B transcription factor, which plays a significant role in regulating the immune response upon infection. Shows antioxidant properties. | (Rose et al., 2005; Ogunlana et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2013b). | |

|

Aloe vera (Gavakava) A. secundiflora A. excelsa A. debrana A. pulcherrima A. excels A. spicata |

Tannins Phlobatannins Saponin Flavonoids Trepenoids carbohydtrates |

Tannins: Penetrates the coccidia's oocyst wall and destroy the cytoplasm, as they probably inactivate the endogenous enzymes responsible for the cycle of sporulation in chickens. Saponins: as mentioned above. Flavonoids and trepenoids: inhibits the invasion and replication of different species of coccidia. Aloe polysaccharide acemannan, bindsto the mannose receptor on macrophages, stimulating them to produce inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 through IL-6 and TNF- and eventually suppress coccidiosis as shown by higher weight gain and lower fecal oocyst counts. |

Eimeria tenella, Eimeria acervulina and Eimeria maxima | Improves body weight gain and reduces mortality. Shows antioxidant and immunostimulatory properties. |

(Molan et al., 2004; Mwale et al., 2006; Yim et al., 2011; Akhtar et al., 2012; Narsih and Wignyanto, 2012; Kheirabadi et al., 2014; Muthamilselvan et al., 2016; Kaingu et al. 2017; Isah et al., 2019; Desalegn and Ahmed 2020). |

| Artemisia annua (A. annua) | Artemisinin (anticoccidial) | Reduces the sporulation rate through minimizing the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase expression in macrogametes. This have a role in calcium homeostasis affecting the wall-forming bodies’ secretion, a calcium-dependent mechanism leading to inhibition of the oocyst wall formation process leading to oocyst defect wall and oocyst death. Expresses the formation of reactive oxygen species through iron-implicated peroxide complex degradation and promotes oxidative stress. Reactive oxygen species inhibits sporulation directly and the formation of the cell wall in Eimeria species, resulting in life cycle interference. Reduces oocyst shedding in broiler chickens. |

Eimeria tenella, Eimeria maxima, and Eimeria acervulina | Improves feed conversion ratio and body weight gain. | (Del Cacho et al., 2010; Drăgan et al., 2010,2014; de Almeida et al., 2014; Kaboutari et al., 2014; Jiao et al., 2018) |

| Leaf powder of A. annua | Protects chickens from pathological symptoms and mortality associated with Eimeria tenella infection and reduces the lesion score, and fecal oocyst output. The leaf powder was more efficient than the essential oil, which could be due to a lack of artemisinin in the oil, and to the greater antioxidant ability of A. annua leaves than the oils. |

Eimeria tenella | (Ferreira et al., 2010) | ||

| Ethanolic extract of A. annua (AE) | Preventive role is better than treatment. | Eimeria acervulina, Eimeria necatrix and Eimeria tenella | Improves body weight gain. | (Fatemi et al., 2017) | |

| The leaf extract was the most effective treatment to decrease the oocysts in chicken feces. Reduces the caecal lesion value. | Eimeria tenella | Keeps the packed cell volume at a regular stage. | (Jamshidi et al., 2014; Wiedosari and Wardhana, 2018) | ||

| Phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and phytochemicals of A. annua | Flavonoids have antioxidant capacity due to their redox activities. Some flavonoids work on the disturbance of protozoan parasites, and others are responsible for host-parasite interactions. | Maintains a healthy microflora and consumes large amounts of nitrogen. Commensal bacteria play an essential role in activating food digestion and nutrients absorption. Improves body weight gain and reduces feed conversion ratio. Promotes acquired and innate immune response in poultry. | (Brisbin et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2012a) |

||

| Artemisia herba-alba | Artemisinin; camphor; 1,8-cineole, tannins, and antioxidant compounds | Artemisinin slows down Eimeria reproduction. It decreases the sporulation and survival capability of the oocysts in the litter. The functional endoperoxide bridge of artemisinin induces oxidative stress by generating a cascade of free radicals (key point in the antiprotozoal activities of artemisinin and subsequently alkylation of proteins and lipid peroxidation). Artemisinin blocks the pro-inflammatory factors activated by the parasite. | Eimeria tenella | Protects infected broiler chickens from mortality and pathological symptoms. Reduces the cecal lesions in infected broiler chickens. Improves the hematological parameters and lowers the intensity of bloody diarrhea. | (Allen 1997; Meshnick, 2002; Del Cacho et al., 2010; Dragan et al., 2010; de Almeida et al., 2012; Zaman et al., 2012; Kaboutari et al., 2014; Kheirabadi et al., 2014; Lu et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020). |

|

Artemisia sieberi A. asiatica |

Artemisinin | Reduces oocyst counts in the infected broiler chickens. | Mixed suspension of Eimeria acervulina, Eimeria tenella, Eimeria necatrix, and Eimeria maxima | Enhances body weight gain and reduces feed intake. | (Kheirabadi et al., 2014). |

| Astragalus membranaceus | Polysaccharides, flavonoids tannins and saponins | Enhances anticoccidial antibodies activity via increase in the cellular and humoral immunity. | Eimeria tenella | Shows anti-inflammatory characteristic and improves intestinal integrity. | (Guo et al., 2004; Abdel-Tawab et al., 2020). |

| Azadirachta indica (Neem) | Salinomycin and bioactive molecules such as azadirachtin limonoids, protolimonoids, tetranortriterpenoids, pentanortiterpenoids, hexanortriterpenoids, some nonterpenoid (anticoccidial) | Shows high efficacy against protozoan parasites (such as coccidian species). |

Eimeria tenella | Shows high efficacy against bacterial, fungal and viral pathogens. Shows antitumor and anti-inflammatory properties. | (Donli and Buahin, 1998; Etuk et al., 2004; Abbas et al., 2006; Koul et al., 2006; Tipu et al., 2006). |

|

Berberis lycium extracts Ageratum conyzoides Linum usitatissimum Vernonia amygdalina |

Berberine N-3 fatty acids, flavonoids, and vernoside |

Inhibits the Eimeria tenella sporozoites invasion into intestinal epithelial cells in poultry via oxidative stress induction (Reactive nitrogen species and reactive oxygen species production). Oxidative stress is known to induce imbalance in the host of oxidant or antioxidant cells. | Eimeria tenella | Improves the growth of chicken without any toxicity. Shows antimicrobial activity. | (Allen, 1997; Danforth et al., 1997; Allen et al., 1998; Al-Fifi, 2007; Nweze and Obiwulu, 2009; Oyagbemi and Adejinmi, 2012; Malik et al., 2014). |

| Beta vulgaris (Sugar beet) | Betaine | Suppresses Eimeria developmental life cycle in the chicken's intestinal cells before oocysts are released in feces. Decreases Eimeria oocyst excretion and the severity of infection or indirectly by interaction with intestinal microflora blocking proinflammatory factors activated by the parasite. This enhances immunity and the resistance to infection. Decreases the risk of secondary bacterial infections. Reduces the severity of Eimeria infections by ameliorating the degree of intestinal lipid peroxidation. Stabilizes and assists the defense of the epithelial cells in which Eimeria multiply. Acts as osmolyte (maintains the water inside the epithelial cells decreasing diarrhea in coccidial infection). | Eimeria tenella, Eimeria acervulina, and Eimeria maxima | Improves gut health, integrity of cell membrane and increases digestibility. Improves the productive performance (daily body weight gain). Shows anticoccidial potential in dose dependent manner in terms of better feed conversion ratio, reduction in oocysts per gram of feces and lesion scores. | (Allen et al., 1998; Molan et al., 2009; Abbas et al., 2017). |

| Bidens pilosa | Unknown, as this plant is a rich source of phytochemicals, including 70 aliphatics, 60 flavonoids (e.g., (quercetin- 3,3-dimethoxy-7-0-rhamno-glucopyranose), 25 terpenoids, 19 phenylpropanoids, 13 aromatics, 8 porphyrins, and 6 other compounds. | Suppresses oocyst sporulation, sporozoite invasion, and schizonts in the life cycle. | Eimeria tenella | Enhances T cell-mediated immunity. Improves body weight gain, survival rate, fecal oocyst count, gut pathology, and decreases bloody diarrhea. | (Bartolome et al., 2013; Akram et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2015; Chang et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2019) |

| Camellia sinensis (Green tea) extracts | Polyphenolic compounds and selenium | Inhibits the enzymes responsible for coccidian sporulation. | Eimeria tenella, Eimeria acervulina, and Eimeria maxima | Shows antioxidant properties. | (Jang et al., 2007; Ogunlana et al., 2008; Molan and Faraj, 2015). |

| Carica papaya | Papain Vitamin A |

Prevents sporozoite invasion into intestinal epithelial cells. Shows proteolytic destruction of Eimeria by papain. Shows improvement in the intestinal epithelial cells by vitamin A. | Eimeria tenella | - | (Al-Fifi, 2007; Nghonjuyi et al., 2015; Dakpogan et al., 2018; Akhter et al., 2021). |

| Cinnamomum cassia | Cinnamaldehyde | Increases the T-cells and their cytokines inducing immunomodulation against Eimeria. | Eimeria tenella, Eimeria acervulina, and Eimeria maxima | Enhances immunity. Improves body weight gain, survival rate, gut integrity, and decreases diarrhea. | (Lee et al., 2011; Orengo et al., 2012) |

| Commiphora swynnertonii | Phenolic compounds tannins, alkaloids, saponins, anthraquinones, cardiac glycosides, and terpenes | Tannins and saponins shows anticoccidial effect. | Eimeria necarix, Eimeria tenella, and E. mitis | Reduces the mortality rate and oocysts counts. | (Hanuš et al., 2005; Max et al., 2009; Baghdadi and Al-Mathal, 2010; Bakari et al., 2012). |

| Curcuma longa (Turmeric) | Phenolic compounds (Curcumins or diferuloylmethane) | Inhibits the growth of Eimeria species at sporogony (destroy sporozoite) preventing sporozoite invasion into intestinal epithelial cells and merogony stages. Reduces oocyst shedding and gut lesions. | Eimeria tenella, Eimeria acervulina and Eimeria maxima | Increases body weight gain. Shows antioxidative, anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties. | (Allen et al., 1998; Abbas et al., 2010, Abbas et al., 2011; Khalafalla et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2013a; Aljedaie and Al-Malki 2020). |

|

Cyamopsis tetragonoloba (Guar) bean |

Saponins | Inhibits the growth of Eimeria species at sporogony (destroys sporozoite). Prevents sporozoite invasion into intestinal epithelial cells and merogony stages. Reduces oocyst shedding and gut lesions. | Eimeria tenella, Eimeria acervulina and Eimeria maxima | Enhances the nonspecific immunity. Improves the daily body weight gain and reduces feed conversion ratio. Reduces the mortality rate. Decreases the fecal oocyst shedding. Reduces ammonia production. |

(Sánchez-Hernández et al., 2019). |

| Dichroa febrifuga (halofuginone) | Febrifugine is an alkaloid isolated from this plant, and its halogenated derivative, halofuginone | Shows coccidiostatic effect acting only at the early stages, about 0–72 h post inoculation, (sporozoites, schizonts and merozoites) of first and second generation of schizogony stages of E. tenella endogenous development. The halofuginone acts in inhibiting the adherence of the parasites and invasion of host intestinal hypothetical cells but remain unable to kill the parasites directly and thus only delay the development of Eimeria. | Eimeria tenella | Enhances immunity, especially T cell-mediated immunity. Improves body weight gain, survival rate, gut pathology, and decreases bloody diarrhea. | (Youn and Noh, 2001; Lillehoj et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2012a,b; Yang et al., 2015; Muthamilselvan et al., 2016). |

|

Echinacea purpurea E. officinalis |

Chicoric acid and tannins (pedunculagin) | - | Eimeria tenella | Shows an effective humoral immune response against coccidial infection in chickens. | (Allen, 2003; Kaleem et al., 2014). |

| Emblica officinalis | Tannins, akaloids, carbohydrates, polyphenolics, essential amino acids, and vitamins (high concentration of vitamin C), ellagitannin, gallic acid, emblicanin A, emblicanin B, ellagic acid, flavonoids and kaempferol | Shows coccidiocidal or coccidiostatic, in a concentration-dependent. Shows oocysticidal activity and inhibits sporulation. Tannins inhibits the development of the parasites life cycle. | Eimeria acervulina, Eimeria maxima, Eimeria necatrix, and Eimeria tenella | Shows higher daily body weight gain and lowers oocyst shedding. Promotes humoral and cellular immune response. |

(Kaleem et al., 2014; Sharma et al., 2021). |

| Fomitella fraxinea (wood-rotting mushroom) | Fungal lectin. | Strengthens cellular and humoral immune responses of Eimeria species. | Eimeria acervulina | Shows immuno-stimulatory activity. | (Dalloul et al., 2006). |

| Fructus Meliae toosendan | Triterpenoids, steroids and limonoids. | Shows strong inhibitory properties against oocysts sporulation and increases the proportion of degenerated oocysts. | Eimeria tenella | Decreases the degree of bloody diarrhea and the output of oocysts. Enhances the relative weight gain rate and inhibits mortality. Improves the caecum intestinal microflora. Reduces the colonization of secondary bacterial infections or oocysts of E. tenella in the intestinal tract. Enhances the immune function of chickens. | (Wu et al. 2010; Zhang et al., 2010 ; Hu et al., 2011,2018; Yong et al., 2020). |

| Galla rhois powder | Methyl gallate; 3-galloyl-gallic acid; 4-galloyl- gallic acid isomers; 1,2,3,4,6-penta-O-galloyl-β-D-glucose; 2 inactive phenolic compounds, gallic acid methyl ester and gallic acid. |

Stops oocyte shedding and decreases lesion scores. | Eimeria tenella | Improves body weight gain, reduces feed intake. Shows antibacterial and antiviral effect. | (Lee et al., 2012). |

|

Ganoderma applanatum Ganoderma lucidum Pleurotus ostreatus (wild mushrooms) |

Active polysaccharides, glycoproteins, organic acids, resins, glycosides (steroid, triterpenoid and saponins) | Polysaccharides are known to block colonization of the intestine by pathogens. Suppresses oocyst sporulation. | Eimeria tenella | Improves carcass weight. Ameliorates bloody diarrhea. | (Ogbe et al., 2008; Ogbe et al., 2010; Ahad et al., 2016). |

|

Glycyrrhiza glabra, Gypsophila paniculate, Aesculus hippocastanum. |

Saponins | Saponins used in coating the Eimeria antigens in immunostimulation complexes during vaccine preparation. | Eimeria tenella, Eimeria acervulina, and Eimeria maxima | Transports antigens and maintains their activity and stimulates IgG and IgM. | (Berezin et al., 2010). |

| Khaya senegalensis bark | Alkaloids and phenolics | Shows antioxidant properties. Ameliorates the degree of intestinal lipid peroxidation. | Eimeria tenella | Improves body weight gain and reduces feed conversion ratio. Reduces lesion scores and oocysts excretion | (Dakpogan et al., 2019). |

| Lepidium sativum (garden cress) seeds | Tocopherol, carotenoid, oleic acid, and α-linolenic acid. Antioxidant-rich extracts with high n-3 fatty acids (n-3 FA) | Tocopherols are lipid-soluble antioxidants. Have an effect on the intracellular development of the parasites. Reduces the invasion and development in chickens. Induces ultra-structural changes in both the asexual and sexual stages induced by n-3 fatty acids. | Eimeria tenella | Decreases mortality, faecal oocyst shedding and lesion score. | (Allen et al., 1996; Danforth et al., 1997; Diwakar et al. 2010; Adamu and Boonkaewwan, 2014). |

| Morinda lucida Benth (Rubiaceae), Morinda cordifolia, M. citrifolia, Myrianthus arboreus. | Acetone leaf extract contains alkaloids, anthraquinones, anthraquinols | Inhibits fecal oocyst, and reduces fecal oocyst score. | Eimeria tenella, Eimeria acervulina and Eimeria maxima | Improves body weight gain, and hematological parameters. Shows antioxidant properties. | (Ola-Fadunsin and Ademola, 2014; Rakhmani et al., 2014). |

| Saponins | Inhibits fecal oocyst, and reduces fecal oocyst score. | ||||

| Moringa oleifera | Ascorbic acid, flavonoids, phenolics, carotenoid, zeatin, quercetin, β - sitosterol, caffeoylquinic acid and kaempferol. Protein, vitamins (C, A), amino acids and various phenolics. | Shows antioxidant properties. Ameliorates the degree of intestinal lipid peroxidation. | Eimeria tenella, Eimeria acervulina, Eimeria necatrix, Eimeria maxima and Eimeria brunetti | Inhibits oocyst output. Decreases fecal score, mortality and improves body weight gain. | (Ola-Fadunsin and Ademola, 2013). |

| Musa paradisiaca (banana roots) | Pectin and several flavonoids (Leucocyanidin, quercetin and its 3-O- galactoside, 3-O-glucoside, and 3-O-rhamnosyl glucoside) | Prevents coccidial developments and reduces its reproduction. | Eimeria tenella | Decreases the infection severity and oocyst shedding in a dose-dependent manner (1 g/kg body weight). | (Anosa and Okoro, 2011) |

| Nauclea diderichii | Ursolic and betulinic acids | Destroys the sporulated oocysts. | Eimeria tenella | Improves body weight gain, and hematological parameters. | (Ibrahim, 2016). |

| Olea europaea (Olive tree) | Maslinic acid, large concentrations of polyphenolic or biophenols (cynarosid/luteolin-7-O-glucoside; tyrosololeuropein quercetinisohamnetin; neobavaisoflavone 2, 3-dihydro-amentoflavone quercetin-3-O-rutinosidechlorogenic acid, isorhamnetin 3-O-(6”-O-feruloyl)-glucoside), diligustilide quercetin-o-(o-galloyl)-hexoside) |

Shows destructive effect on sporulated oocysts. |

Eimeria tenella; Eimeria acervulina, Eimeria tenella, Eimeria mitis, Eimeria brunetti and Eimeria maxima |

Improves lesion index, the oocyst index, and the anticoccidial index. | (De Pablos et al., 2010; Debbou-Iouknane et al., 2021). |

| Origanum vulgare (Oregano oil) | Phenols (thymol and carvacrol) | Phenols (thymol and carvacrol) interacts with the cytoplasmic membrane by changing its permeability for cations, (H+ and K+). The dissipation of ion gradients leads to impairment of essential processes in the cell. This allows leakage of cellular constituents, resulting in water unbalance, the collapse of the membrane potential and inhibition of ATP synthesis, and finally, cell death. Have a toxic effect on the upper layer of mature enterocytes of the intestinal mucosa. This is due to carvacrol's hydrophobicity, which accelerates the natural renewal process, therefor sporozoite infected cells are shed before the merozoite phase. | Eimeria tenella, Eimeria acervulina, and Eimeria maxima | Increases body weight gain and reduces feed conversion ratio. | (Weber and de Bont, 1996; Ultee et al., 2002; Giannenas et al., 2003; Tsinas et al. 2011; Mohiti-Asli and Ghanaatparast-Rashti, 2015; Sidiropoulou et al., 2020). |

| Parkia biglobosa (Bark root) | Phenolic compounds (tannins, saponins and flavonoids) | Reduces the oocyte count. | Eimeria tenella | Improves carcass weight, stopped mortality. Reduces blood droppings. | (Mertz et al., 2001; Maikai et al., 2007; Ugwuoke and Pewan, 2020). |

| Pimpinella anisum | Anethole, methylchavicol, eugenol, anisaldehyde and estragole | Reduces the oocyte number in broiler chickens only in case of combination with A. annua. | Eimeria tenella | Enhances performance (better body weight gain and reduces feed conversion ratio. | (Drăgan et al., 2010). |

| Pinus radiata (Pine bark) | Tannins | Penetrates the coccidia's oocyst wall and destroys the cytoplasm. Inactivates the endogenous enzymes responsible for the sporulation in chickens. | Eimeria tenella, Eimeria acervulina, and Eimeria maxima | Enhances performance (better body weight gain and reduces feed conversion ratio. | (Jang et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2008; Molan et al., 2009; Nweze and Obiwulu, 2009; Muthamilselvan et al., 2016). |

|

Prunus domestica Prunus salicina (Plums fruit powder) |

High levels of phenolic compounds, including flavonoids (anthocyanins) | Lowers fecal oocysts shedding. | Eimeria acervulina | Increases body weight gain and increases the IFN-gamma and IL-15 transcription and the proliferation of splenocytes. Improves the immune response to coccidiosis. Shows antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. | (Lee et al., 2008; Ogunlana et al. 2008; Jaiswal et al., 2013; Igwe and Charlton, 2016; Muthamilselvan et al., 2016). |

| Psidium guajava (guava) | Tannins, phenols, triterpenes, flavonoids, essential oils, saponins, carotenoids, lectins, vitamins (A, C and B complex), fiber and fatty acids and pectin | Psidium guajava extract inhibits sporulation process of Eimeria oocysts by inhibiting or inactivating the enzymes responsible for the sporulation. Penetrates the wall of the oocysts affecting the internal and external morphology of oocysts. | Eimeria tenella | Shows anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antioxidants properties. | (Ahmed et al., 2018). |

| Punica granatum | Casuarinin, corilagin, granatin-A, tellimagrandin-I, punicalin, punicalagin, terminalin/gallayldilacton, ellagic acid | Recuses oocyst output. | Eimeria tenella | Improves intestinal lesions and enhances body weight gain and reduces feed conversion ratio. | (Dkhil, 2013; Ahad et al., 2018). |

|

Saccharum officinarum (sugarcane) |

Phenolic compounds like flavones (luteolin, apigenin and tricin derivatives), caffeic, hydroxycinnamic and sinapic acids (laborious methanolic extraction method) | Shows in vitro inhibitory potential on sporulation of coccidian oocysts. | Eimeria tenella, Eimeria necatrix, Eimeria mitis, Eimeria brunetti | Shows anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antistress, antiviral, antibacterial and immunomodulatory activities. | (Fornazier et al., 2002; Abbas et al., 2015). |

| Salvadora persica (Arak roots) | Phytochemicals like vitamin C, salvadorine, salvadourea, alkaloids, trimethylamine, cyanogenic glycosides, tannins, saponins and salts, mostly as chlorides | Diminishes oocyst output through inhibition or impairment of the invasion, replication and development of Eimeria parasite species in the gut tissues of chickens. Reacts with cytoplasmic membranes and modifys their cation absorption, leading to damage of vital activities in coccidial cells leading to coccidial cell death. Stimulates antioxidative stress enzymes and neutralizing reactive oxygen species. This may have beneficial effects in treating coccidial infections ameliorating the degree of intestinal lipid peroxidation. | Eimeria tenella, Eimeria acervulina and Eimeria. maxima | Shows anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. Inhibits stress-induced abnormalities in hematological parameters, demonstrating its defensive effect against stress. | (Ramadan and Alshamrani, 2015; Thagfan et al., 2017; Aljedaie and Al-Malki 2020). |

| Senna siamea leaves (cassia) | Alkaloids called cassiarin emodin and upoleole | Shows antioxidant properties by ameliorating the degree of intestinal lipid peroxidation. | Eimeria tenella | Enhances body weight gain and decreases feed conversion ratio. Reduces lesion scores and oocysts excretion. Shows antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. | (Dakpogan et al., 2019). |

| Tannic acid extract | Tannic acid | Decreases oocyte numbers. | Eimeria tenella, Eimeria acervulina, and Eimeria maxima | Decreases feed conversion ratio. | (Tonda et al., 2018). |

| Trachyspermum ammi (Ajwain) | Thymol and carvacrol | Shows in vitro anticoccidial effect by affecting sporulation (%) of Eimeria oocysts in dose dependent manner. Damages the morphology of oocysts in terms of shape, size and number of sporocysts. Stops the sporulation process and damages the morphology of Eimeria oocysts in dose dependent manner. Such higher in vitro anticoccidial potential of T. ammi extract might be due to action of its antioxidant compounds of T. ammi against Eimeria. | Eimeria tenella, Eimeria brunetti, Eimeria necatrix and Eimeria mitis | Enhances body weight gain and reduces feed conversion ratio. | (Abbas et al., 2019). |

| Tulbaghia violacea Harv | Antioxidant compounds as S -(methylthiomethyl) cysteine sulfoxide (marasmine), bis[(methylthio)methyl] disulfide and various derivatives |

Decreases the oocyst production in the birds. Induces host cell destruction associated with oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation and the ability to neutralize reactive oxygen species. | Eimeria tenella, Eimeria acervulina, and Eimeria maxima | Shows antioxidant activity. Improves gut pathology, body weight gain. |

(Naidoo et al., 2008). |

|

Vitis vinifera (Grape) seed extract |

Proanthocyanidins [monomeric flavanols (catechin and epicatechin), dimeric, trimeric, and polymeric procyanidins, and phenolic acids (gallic acid and ellagic acid)] | Grape seed proanthocyanidin extract diminishes coccidiosis via the downregulation of oxidative stress (strong antioxidant). Damages the morphology of oocysts in terms of shape, size and number of sporocysts. |

Eimeria tenella Eimeria tenella, Eimeria necatrix, Eimeria brunetti and Eimeria mitis |

Shows antioxidant activity. Improves gut pathology, and body weight gain. | (Yilmaz and Toledo, 2004; Naidoo et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2008; Abbas et al., 2020). |

| Yucca schidigera | Saponins | Diminishes coccidiosis via the downregulation of oxidative stress (strong antioxidant). Damages the morphology of oocysts in terms of shape, size and number of sporocysts. | Eimeria tenella, Eimeria acervulina and Eimeria maxima | Enhances the nonspecific immunity. Improves the productive performance (daily body weight gain and feed conversion ratio). Reduces the mortality rate. Decreases the faecal oocyst shedding. Reduces ammonia production. | (Hassan et al. 2008; Mohiti-Asli and Ghanaatparast-Rashti, 2015). |

| Zingiber officinale (Ginger) | Phenol derivative as oleoresin and gingerol | Degenerates schizonts in the glandular epithelium. Interacts with parasite through an adsorption involving hydrogen bonding. Low levels of phenol interact with proteins and formd a phenol protein complex. The free phenol infiltrates into the parasite, causing precipitation and protein denaturation. The high levels of phenol cause the coagulation of proteins and lysis of the cell membrane. | Eimeria tenella, Eimeria acervulina and Eimeria maxima | Increases body weight gain. Shows antioxidative, anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties. | (Ali et al., 2019; Aljedaie and Al-Malki 2020). |

Table 3.

Different herbal mixtures; bioactive compounds; specific anticoccidial properties and their effects exerted on poultry and the studied coccidian species.

| Herbal mixtures | Bioactive compounds | Specific anticoccidial effects exerted in poultry | Studied coccidian species | Other beneficial effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Herbal essential oils (Eos) of Oreganum compactum, A. absinthium, Rosmarinus officinalis, Anredera cordifolia, Morinda citrifolia, Malvaviscus arboreus, Syzygium aromaticum (eugenol), Melaleuca alternifolia, Citrus sinensis, Curcuma zanthorrhiza (curcumin), Piper nigrum (piperin) and Thymus vulgaris (Thymol) | - | The EOs β thujone 1,8-cineol and p-cymene from A. absinthium prevents Eimeria oocyst development, while cineol, α-pinene and bornyl acetate from R. ofcinalis acts as antioxidants. Limonene and linalool from C. sinensis, and thymol and p-cymene from T. vulgaris destroys Eimeria oocysts. |

Eimeria tenella, Eimeria acervulina, and Eimeria maxima | Reduces the total intestinal lesion score. Improves the zootechnical performance body weight gain and feed conversion ratio. | (Cox et al., 2000; Oviedo-Rondón et al., 2006; Reisinger et al., 2011; Remmal et al., 2011; Abbas et al., 2012a,b; Arczewska-Włosek and Świątkiewicz, 2013; Bozkurt et al., 2013; Quiroz-Castañeda and Dantán-González, 2015). |

|

Sophora flavescens Aiton, Pulsatilla koreana, Sinomenium acutum, Ulmus macrocarpa, Quisqualis indica |

Phenolic compounds as flavonoids, tannins, terpenoids and essential oils, alkaloids, and saponins | The EOs β thujone 1,8-cineol and p-cymene from A. absinthium prevents Eimeria oocyst development, while cineol, α-pinene and bornyl acetate from R. ofcinalis acts as antioxidants. Limonene and linalool from C. sinensis, and thymol and p-cymene from T. vulgaris destroys Eimeria oocysts. |

Eimeria tenella | Decreases bloody diarrhea. Increases body weight gain and reduces feed conversion ratio. |

(Youn and Noh, 2001). |

| Agrimonia eupatoria, Echinacea angustifolia, Ribes nigrum, Cinchona succirubra (Apacox) | - | Decreases the number of Eimeria tenella oocytes in chickens. | Eimeria tenella | Decreases bloody diarrhea and increases body weight gain and reduces feed conversion ratio. |

(Christaki et al., 2004). |

| Uncariae ramulus cum Uncaria stem and thorn) Agrimoniae herba (agrimony) Sanguisorbae radix (sanguisorba root) Eclipta prostrata (Yetbadetajo Hert) Rehmanniae radix (rehmannia root) Pulsatillae radix (Chinese Pulsatilla root) Sophora flavescens (flavescent sophorae root) Radix glycyrrhizae (liocerice root) |

Uncaria alkaloids such as rhyncopyline and isorhnchophyline, etc. Agrimonine, agrimonolide, organic acids phenols, agrimol A, B, C and D, etc. b-Sitosterol, pomolic acid, suavissimoside F1 Saponins such as eclalbasaponin I, II, III and XII, etc. Saponins such as rehmaglutins A, B, C and D, acteoside, glutinosides A, B and C Triterpenoid glycosides Alkaloids such as matrine, sophoridine and isomatrine, etc., flavanoids such as isoanhydroicartin, isoxanthohumol, etc. Glycyrrhizin, flavanoids such as licochacone A, isoglycycoumarin |

Shows direct inhibiting effect on the maturing of unsporulated and killing effect on the sporulated oocysts. |

Eimeria tenella | Decreases intestinal lesions and increased body weight gain. | (Du and Hu, 2004). |

| Polysaccharides from Astragalus membranaceus , Carthamus tinctorius, Lentinus edodes, and Tremella fuciformis | - | Polysaccharides enhances anticoccidial antibodies and antigen-specific cell proliferation in splenocytes via cellular and humoral immunity to E. tenella in chickens | Eimeria tenella | - | (Guo et al., 2004). |

| Curcuma longa, Capsicum annuum, and shiitake mushroom | Mixture of curcuma/capsicum/lentinus | Increases antibodies and decreases the number of oocytes in feces. | Eimeria acervulina | Enhances the local innate immunity (Transcriptional levels of local cytokines for IL- IL-, IL-, and IFN-). | (Lee et al., 2009). |

| Prebiotics or oligosaccharides (oligofructose) derived from chicory, onion, garlic, asparagus, artichoke, leek, bananas, tomatoes, wheat | Pyrodextrin, Inulin |

- | - | Enhances immune defense against infection and reduces the mortality rate. Increases the gut microbiota and growth performance. | (Janardhana et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2011; Nabizadeh, 2012; Al-Sheraji et al., 2013; Sugiharto, 2014). |

| Capsicum oleoresin Turmeric oleoresin |

- | Shows increases in NK cells, macrophages, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and their cytokines (IFN- and IL-6). Decreases the TNFSF15 and IL-17F, leading to induction and elevation of host immunity which kills Eimeria tenella in chickens | Eimeria tenella | Increases body weight gain. Lowers feed conversion ratio and mortality. | (Lee et al., 2011). |

| Carvacrol, 1.8-cineole, camphor, and thymol extracted from oregano, bay leaves, and lavender |

- | Reduces oocyst number and shedding in a dose-dependent manner (oocysticidal action). |

Eimeria tenella, Eimeria maxima, Eimeria acervuline, Eimeria necatrix and Eimeria mitis | Improves performance of birds. | (Remmal et al., 2011,2013; Bozkurt et al., 2012). |

| Isopulegol, carvacrol, carvone, eugenol, cineol, cinnamaldehyde, carveol and thymol | Reduces oocyst number and shedding in a dose-dependent manner (oocysticidal action). |

Eimeria tenella, Eimeria maxima, Eimeria acervuline, Eimeria necatrix and Eimeria mitis | Improves performance of birds. | (Remmal et al., 2011,2013; Bozkurt et al., 2012). | |

| Mixture of leaves of Azadirachta indica A. Juss and Nicotiana tabacum L.; flowers of Calotropis procera Ait. F. and seeds of Trachyspermum ammi L. | Phytochemicals of 4 plants discussed above can be broadly divided into phenols flavonoids, tannins, terpenoids and essential oils, alkaloids, and saponins. Nicotiana tabacum contains alkaloids, mainly nicotine. Calotropis procera is rich in alkaloids, carbohydrates, glycosides, phenolic compounds/tannins, proteins and amino acids, proteolytic enzymes, flavonoids, saponins, sterols and/or triterpenes, acidic compounds and resins. Azadirachta indica and Trachyspermum ammi mentioned above |

Shows a concentration-dependent anticoccidial activity. | Eimeria tenella | Shows anti-tumor, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antiproliferative, antibacterial, antiviral, and anti-parasitic properties. | (Zaman et al., 2012). |

| Allium sativum, Urtica dioica, Inula helenium, Glycyrrhiza glabra, R. officinalis, Chelidonium majus, Thymus serpyllum, Tanacetum vulgare, and Coriandrum sativum. Salvia libonitica decoction, Eucalyptus EO, Peppermint EO, and saponin | - | - | Eimeria tenella, Eimeria acervulina, and Eimeria maxima | Reduces the total intestinal lesion score and improves the zootechnical performance. | (Oviedo-Rondón et al., 2006; Pop et al., 2019; Sultan et al., 2019). |

| Herbal mixture of Allium sativum, Urtica dioica, Inula helenium, Glycyrrhiza glabra, Rosmarinus officinalis, Chelidonium majus, Thymus serpyllum, Tanacetum vulgare, Coriandrum sativum | Flavonoids, tannins or saponins, polyphenols. Chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid and luteolin. | Alters the process of oocyst wall formation. Inhibits sporulation by destroying the sporozoites. Alleviates the damage to the intestinal tissue during parasite invasion by reducing the cytotoxic effects caused by the reactive oxygen species and thus the lowers the lesion score. | Eimeria maxi | Reduces the coccidian multiplication rate. Reduces the severity of intestinal lesions. Shows immunomodulatory effects. | (Pop et al., 2019). |

| Herbal powder (Shi Yin Zi) consists of: Cnidium monnieri (L.) Cuss, Taraxacum mongolicum Hand.-Mazz., and sodium chloride |

Osthole Chlorogenic acid and caffeic acid |

Inhibits coccidian oocyst sporulation. | Eimeria tenella | Alleviates the histopathological changes of the cecum, and the number of oocysts and mucosa cell necrocytosis. Improves body weight gain. | (Song et al., 2020). |

CONCLUSION

In domestic fowl, each of the 7 Eimeria species developing inside the chick's digestive tract in a particular location inducing everything from subclinical enteric infection to subacute mortality. Eimeria species, strains and their infective dose, host genetics, flock size, environmental and stress factors, and concurrent infection could influence the clinical outcome of coccidial infection. Recently herbal products have received more attention for their use in prophylaxis or therapy for avian coccidiosis. Here, we summarized the research findings of phytogenic compounds, which showed preventive, therapeutic, or immuno-modulating effects against coccidiosis. These herbal treatments are characterized by the absence of coccidial resistance development (up till now).

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Abu Dhabi Award for Research Excellence-Department of Education and Knowledge (Grant #: 21S105) to Khaled A. El-Tarabily. Thanks also extended to the library at Murdoch University, Australia for the valuable online resources and comprehensive databases.

Author contribution: All authors were equally contributed in writing this review article. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

DISCLOSURES

Authors declare no conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

- Abbas R.Z., Abbas A., Iqbal Z., Raza M., Hussain K., Ahmed T., Shafi M. In vitro anticoccidial activity of Vitis vinifera extract on oocysts of different Eimeria species of broiler chicken. J. Hell. Vet. Med. Soc. 2020;71:2267–2272. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas R.Z., Abbas A., Raza M.A., Khan M.K., Saleemi M.K., Saeed Z. In vitro anticoccidial activity of Trachyspermum ammi (Ajwain) extract on oocysts of Eimeria species of Chicken. Adv. Life Sci. 2019;7:44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas R.Z., Colwell D., Gilleard J. Botanicals: an alternative approach for the control of avian coccidiosis. Worlds Poult. Sci. J. 2012;68:203–215. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas A., Iqbal Z., Abbas R.Z., Khan M.K., Khan J.A. In vitro anticoccidial potential of Saccharum officinarum extract against Eimeria oocysts. Boletín Latinoamericano y del Caribe de Plantas Medicinales y Aromáticas. 2015;14:456–461. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas A., Iqbal Z., Abbas R.Z., Khan M.K., Khan J.A., Sindhu Z.D., Mahmood M.S., Saleem M.K. In vivo anticoccidial effects of Beta vulgaris (sugar beet) in broiler chickens. Microb. Pathog. 2017;111:139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbas R.Z., Iqbal Z., Akhtar M.S., Khan M.N., Jabbar A., Sandhu Z. Anticoccidial screening of Azadirachta indica (Neem) in broilers. Pharmacologyonline. 2006;3:365–371. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas R.Z., Iqbal Z., Blake D., Khan M., Saleemi M. Anticoccidial drug resistance in fowl coccidia: the state of play revisited. Worlds Poult. Sci. J. 2011;67:337–350. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas R.Z., Iqbal Z., Khan A., Sindhu Z.U.D., Khan J.A., Khan M.N., Raza A. Options for integrated strategies for the control of avian coccidiosis. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2012;14:1014–1020. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas R.Z., Iqbal Z., Khan M.N., Zafar M.A., Zia M.A. Anticoccidial activity of Curcuma longa L. in broiler chickens. Brazil Arch. Biol. Technol. 2010;53:63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Hack M.E., El-Saadony M.T., Shafi M.E., Alshahrani O.A., Saghir S.A., Al-Wajeeh A.S., Al-Shargi O.Y., Taha A.E., Mesalam N.M., Abdel-Moneim A.-M.E. Prebiotics can restrict Salmonella populations in poultry: a review. Anim. Biotechnol. 2021;19:1–10. doi: 10.1080/10495398.2021.1883637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Hack M.E., El-Saadony M.T., Shafi M.E., Qattan S.Y., Batiha G.E., Khafaga A.F., Abdel-Moneim A.M.E., Alagawany M. Probiotics in poultry feed: a comprehensive review. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2020;104:1835–1850. doi: 10.1111/jpn.13454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Hack M.E., El-Saadony M.T., Shafi M.E., Zabermawi N.M., Arif M., Batiha G.E., Khafaga A.F., Abd El-Hakim Y.M., Al-Sagheer A.A. Antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of chitosan and its derivatives and their applications: a review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;164:2726–2744. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.08.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Hack M.E., El-Saadony M.T., Shehata A.M., Arif M., Paswan V.K., Batiha G.E., Khafaga A.F., Elbestawy A.R. Approaches to prevent and control Campylobacter spp. colonization in broiler chickens: a review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021;28:4989–5004. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-11747-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Hack M.E., El-Saadony M.T., Swelum A.A., Arif M., Abo Ghanima M.M., Shukry M., Noreldin A., Taha A.E., El-Tarabily K.A. Curcumin, the active substance of turmeric: its effects on health and ways to improve its bioavailability. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021;101:5747–5762. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.11372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Hack M.E., Mohamed E., Alaidaroos B.A., Farsi R.M., Abou-Kassem D.E., El-Saadony M.T., Saad A.M., Shafi M.E., Albaqami N.M., Taha A.E., Ashour E.A. Impacts of supplementing broiler diets with biological curcumin, zinc nanoparticles and Bacillus licheniformis on growth, carcass traits, blood indices, meat quality and cecal microbial load. Animals. 2021;11:1878. doi: 10.3390/ani11071878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelnour S.A., Swelum A.A., Salama A., Al-Ghadi M.Q., Qattan S.Y., Abd El-Hack M.E., Khafaga A.F., Alhimaidi A.R., Almutairi B.O., Ammari A.A., El-Saadony M.T. The beneficial impacts of dietary phycocyanin supplementation on growing rabbits under high ambient temperature. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2020;19:1046–1056. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Tawab H., Abdel-Baki A.S., El-Mallah A.M., Al-Quraishy S., Abdel-Haleem H.M. In vivo and in vitro anticoccidial efficacy of Astragalus membranaceus against Eimeria papillata infection. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2020;32:2269–2275. [Google Scholar]

- Abou-Kassem D.E., Mahrose K.M., El-Samahy R.A., Shafi M.E., El-Saadony M.T., Abd El-Hack M.E., Emam M., El-Sharnouby M., Taha A.E., Ashour E.A. Influences of dietary herbal blend and feed restriction on growth, carcass characteristics and gut microbiota of growing rabbits. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2021;1:896–910. [Google Scholar]

- Adamu M., Boonkaewwan C. Effect of Lepidium sativum L.(garden cress) seed and its extract on experimental Eimeria tenella infection in broiler chickens. Agric. Nat. Resour. 2014;48:28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ahad S., Tanveer S., Malik T.A. Seasonal impact on the prevalence of coccidian infection in broiler chicks across poultry farms in the Kashmir valley. J. Parasit. Dis. 2015;39:736–740. doi: 10.1007/s12639-014-0434-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahad S., Tanveer S., Malik T.A. Anticoccidial activity of aqueous extract of a wild mushroom (Ganoderma applanatum) during experimentally induced coccidial infection in broiler chicken. J. Parasit. Dis. 2016;40:408–414. doi: 10.1007/s12639-014-0518-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahad S., Tanveer S., Malik T.A., Nawchoo I.A. Anticoccidial activity of fruit peel of Punica granatum L. Microb. Pathog. 2018;116:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed A.I., Sulieman M.M., Istifanus W.A., Panda S.M. In vivo anticoccidial activity of crude leaf powder of Psidium guajava in broiler chickens. Sch. Acad. J. Pharm. 2018;7:464–469. [Google Scholar]

- Akhter M.J., Aziz F.B., Hasan M.M., Islam R., Parvez M.M., Sarkar S., Meher M.M. Comparative effect of papaya (Carica papaya) leaves’ extract and toltrazuril on growth performance, hematological parameter, and protozoal load in Sonali chickens infected by mixed Eimeria spp. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2021;8:91–100. doi: 10.5455/javar.2021.h490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar M., Hai A., Awais M.M., Iqbal Z., Muhammad F., Ulhaq A., Anwar M.I. Immunostimulatory and protective effects of Aloe vera against coccidiosis in industrial broiler chickens. Vet. Parasitol. 2012;186:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akram M., Hamid A., Khalil A., Ghaffar A., Tayyaba N., Saeed A., Ali M., Naveed A. Review on medicinal uses, pharmacological, phytochemistry and immunomodulatory activity of plants. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2014;27:313–319. doi: 10.1177/039463201402700301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alagawany M., El-Saadony M.T., Elnesr S., Farahat M., Attia G., Madkour M., Reda F. Use of lemongrass essential oil as a feed additive in quail's nutrition: its effect on growth, carcass, blood biochemistry, antioxidant and immunological indices, digestive enzymes and intestinal microbiota. Poult. Sci. 2021;100 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2021.101172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alagawany M., Madkour M., El-Saadony M.T., Reda F.M. Paenibacillus polymyxa (LM31) as a new feed additive: antioxidant and antimicrobial activity and its effects on growth, blood biochemistry, and intestinal bacterial populations of growing Japanese quail. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2021;276 [Google Scholar]

- Alfaro D.M., Silva A.V.F., Borges S.A., Maiorka F.A., Vargas S., Santin E. Use of Yucca schidigera extract in broiler diets and its effects on performance results obtained with different coccidiosis control methods. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2007;16:248–254. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Fifi Z. Effect of leaves extract of Carica papaya, Vernonia amigdalina and Azadiratcha indica on the coccidiosis in free-range chickens. Asian J. Anim. Sci. 2007;1:26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ali M., Chand N., Khan R.U., Naz S., Gul S. Anticoccidial effect of garlic (Allium sativum) and ginger (Zingiber officinale) against experimentally induced coccidiosis in broiler chickens. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2019;47:79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Aljedaie M.M., Al-Malki E.S. Anticoccidial activities of Salvadora persica (arak), Zingiber officinale (ginger) and Curcuma longa (turmeric) extracts on the control of chicken coccidiosis. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2020;32:2810–2817. [Google Scholar]

- Allameh A., Safamehr A., Mirhadi S.A., Shivazad M., Razzaghi-Abyaneh M., Afshar-Naderi A. Evaluation of biochemical and production parameters of broiler chicks fed ammonia treated aflatoxin contaminated maize grains. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2005;122:289–301. [Google Scholar]

- Allen P.C. Nitric oxide production during Eimeria tenella infections in chickens. Poult. Sci. J. 1997;76:810–813. doi: 10.1093/ps/76.6.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen P.C. Dietary supplementation with echinacea and development of immunity to challenge infection with coccidia. Parasitol. Res. 2003;91:74–78. doi: 10.1007/s00436-003-0938-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen P.C., Danforth H.D., Augustine P.C. Dietary modulation of avian coccidiosis. Int. J. Parasitol. 1998;28:1131–1140. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(98)00029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen P.C., Danforth H.D., Levander O.A. Diets high in n-3 fatty acids reduce cecal lesion scores in chickens infected with Eimeria tenella. Poult. Sci. 1996;75:179–185. doi: 10.3382/ps.0750179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen P.C., Jenkins M.C., Miska K.B. Cross protection studies with Eimeria maxima strains. Parasitol. Res. 2005;97:179–185. doi: 10.1007/s00436-005-1423-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alnassan A.A., Thabet A., Daugschies A., Bangoura B. In vitro efficacy of allicin on chicken Eimeria tenella sporozoites. Parasitol. Res. 2015;114:3913–3915. doi: 10.1007/s00436-015-4637-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Natour M.Q., Suleiman M.M., Abo-Shehada M.N. Flock-level prevalence of Eimeria species among broiler chicks in northern Jorda. Prev. Vet. Med. 2002;53:305–310. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5877(01)00281-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sheraji S.H., Ismail A., Manap M.Y., Mustafa S., Yusof R.M., Hassan F.A. Prebiotics as functional foods: a review. J. Funct. Foods. 2013;5:1542–1553. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. 6th ed. The Merck and Co. Inc.; RoadKenilworth, NJ, USA: 1986. The Merck Veterinary Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Anosa G.N., Okoro O.J. Anticoccidial activity of the methanolic extract of Musa paradisiaca root in chickens. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2011;43:245–248. doi: 10.1007/s11250-010-9684-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arczewska-Włosek A., Świątkiewicz S. Improved performance due to dietary supplementation with selected herbal extracts of broiler chickens infected with Eimeria spp. J. Anim. Feed Sci. 2013;22:257–263. [Google Scholar]

- Ashour E.A., Abd El-Hack M.E., Shafi M.E., Alghamdi W.Y., Taha A.E., Swelum A.A., Tufarelli V., Mulla Z.S., El-Ghareeb W.R., El-Saadony M.T. Impacts of green coffee powder supplementation on growth performance, carcass characteristics, blood indices, meat quality and gut microbial load in broilers. Agriculture. 2020;10:457. [Google Scholar]

- Awadalla S. Effect of some stressors on pathogenicity of Eimeria tenella in broiler chicken. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 1998;28:683–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awais M.M., Akhtar M. Evaluation of some sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.) extracts for immunostimulatory and growth promoting effects in industrial broiler chickens. Pak. Vet. J. 2012;32:398–402. [Google Scholar]

- Baba E., Ikemoto T., Fukata T., Sasai K., Arakawa A., McDougald L. Clostridial population and the intestinal lesions in chickens infected with Clostridium perfringens and Eimeria necatrix. Vet. Microbiol. 1997;54:301–308. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(96)01289-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachaya H., Raza M., Khan M., Iqbal Z., Abbas R., Murtaza S., Badar N. Predominance and detection of different Eimeria species causing coccidiosis in layer chickens. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2012;22:597–600. [Google Scholar]

- Badran I., Lukesova D. Control of coccidiosis and different coccidia of chicken in selected technologies used in tropics and subtropics. Agricultura Tropica Et Subtropica. 2006;39:39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Baghdadi H.B., Al-Mathal E.M. Anticoccidial effect of Commiphora molmol in the domestic rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus domesticus L.) J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 2010;40:653–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakari G.G., Max R.A., Mdegela R.H., Phiri E.C., Mtambo M.M. Effect of resinous extract from Commiphora swynnertonii (Burrt) on experimental coccidial infection in chickens. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2012;45:455–459. doi: 10.1007/s11250-012-0239-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakshi C.S., Sikdar A., Johari T., Meenakshi M., Singh R. Effect of graded dietary levels of aflatoxin on humoral immune response in commercial broilers. Indian J. Comp. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. Dis. 2000;21:163–164. [Google Scholar]

- Bartolome A.P., Villaseñor I.M., Yang W.C. Bidens pilosa L. (Asteraceae): botanical properties, traditional uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacology. Evid-Based Compl. Alt. Med. 2013;2013:1–51. doi: 10.1155/2013/340215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezin V., Bogoyavlenskyi A., Khudiakova S., Alexuk P., Omirtaeva E., Zaitceva I., Tustikbaeva G., Barfield R., Fetterer R. Immunostimulatory complexes containing Eimeria tenella antigens and low toxicity plant saponins induce antibody response and provide protection from challenge in broiler chickens. Vet. Parasitol. 2010;167:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake D.P., Knox J., Dehaeck B., Huntington B., Rathinam T., Ravipati V., Ayoade S., Gilbert W., Adebambo A.O., Jatau I.D., Raman M., Parker D., Rushton J., Tomley F.M. Re-calculating the cost of coccidiosis in chickens. Vet. Res. 2020;51:115. doi: 10.1186/s13567-020-00837-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozkurt M., Giannenas I., Küçükyilmaz K., Christaki E., Florou-Paneri P. An update on approaches to controlling coccidia in poultry using botanical extracts. Br. Poult. Sci. 2013;54:713–727. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2013.849795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozkurt M., Selek N., Küçükyilmaz K., Eren H., Güven E., Çatli A., Çinar M. Effects of dietary supplementation with a herbal extract on the performance of broilers infected with a mixture of Eimeria species. Br. Poult. Sci. 2012;53:325–332. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2012.699673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisbin J.T., Gong J., Sharif S. Interactions between commensal bacteria and the gut-associated immune system of the chicken. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2008;9:101–110. doi: 10.1017/S146625230800145X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumstead N., Millard B. Variation in susceptibility of inbred lines of chickens to seven species of Eimeria. Parasitology. 1992;104:407–413. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000063654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C.T., Yang C.Y., Muthamilselvan T., Yang W.C. Field trial of medicinal plant, Bidens pilosa, against eimeriosis in broilers. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:24692. doi: 10.1038/srep24692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanie M., Negash T., Tilahun S.B. Occurrence of concurrent infectious diseases in broiler chickens is a threat to commercial poultry farms in central Ethiopia. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2009;41:1309–1317. doi: 10.1007/s11250-009-9316-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman H., Cherry T., Danforth H., Richards G., Shirley M., Williams R. Sustainable coccidiosis control in poultry production: the role of live vaccines. Int. J. Parasitol. 2002;32:617–629. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00362-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman H., Roberts B., Shirley M., Williams R. Guidelines for evaluating the efficacy and safety of live anticoccidial vaccines, and obtaining approval for their use in chickens and turkeys. Avian Pathol. 2005;34:279–290. doi: 10.1080/03079450500178378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeke P.R. In: Pages 241-254 in Saponins in Food, Feedstuffs and Medicinal Plants. Proceedings of the Phythochemical Society of Europe. Oleszek W., Marston A., editors. Proceedings of the Phythochemical Society of Europe, Springer; Dordrecht, Netherlands: 2000. Actual and potential applications of Yucca Schidigera and Quillaja Saponaria saponins in human and animal nutrition. [Google Scholar]

- Christaki E., Florou-Paneri P., Giannenas I., Papazahariadou M., Botsoglou N.A., Spais A.B. Effect of a mixture of herbal extracts on broiler chickens infected with Eimeria tenella. Anim. Res. 2004;53:137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Clare R.A., Strout R.G., Taylor R.L., Jr, Collins W.M., Briles W.E. Major histocompatibility (B) complex effects on acquired immunity to cecal coccidiosis. Immunogenetics. 1985;22:593–599. doi: 10.1007/BF00430307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier C., Hofacre C., Payne A., Anderson D., Kaiser P., Mackie R., Gaskins H. Coccidia-induced mucogenesis promotes the onset of necrotic enteritis by supporting Clostridium perfringens growth. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2008;122:104–115. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox S., Mann C., Markham J., Bell H.C., Gustafson J., Warmington J., Wyllie S.G. The mode of antimicrobial action of the essential oil of Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree oil) J. Appl. Microbiol. 2000;88:170–175. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dakpogan H.B., Gandaho C.S., Houndonougbo P.V., Dossa L.H., Houndonougbo M.F., Chrysostome C. Anticoccidial activity of Khaya senegalensis, Senna siamea and Chamaecrista rotundifolia in chicken (Gallus gallus) Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2019;13:2121–2128. [Google Scholar]

- Dakpogan H.B., Mensah S., Attindehou S., Chysostome C., Aboh A., Naciri M., Salifou S., Mensah G.A. Anticoccidial activity of Carica papaya and Vernonia amygdalina extract. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2018;12:2101–2108. [Google Scholar]

- Dakpogan H.B., Salifou S., Mensah G.A., Gbangbotche A., Youssao I., Naciri M., Sakiti N. Problem of the control and prevention of coccidiosis in chickens. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2012;6:6088–6105. [Google Scholar]

- Dalloul R., Lillehoj H., Lee J., Lee S., Chung K. Immunopotentiating effect of a Fomitella fraxinea-derived lectin on chicken immunity and resistance to coccidiosis. Poult. Sci. J. 2006;85:446–451. doi: 10.1093/ps/85.3.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danforth H.D., Allen P.C., Levander O.A. The effect of high n-3 fatty acids diets on the ultrastructural development of Eimeria tenella. Parasitol. Res. 1997;83:440–444. doi: 10.1007/s004360050277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida G.F., Horsted K., Thamsborg S.M., Kyvsgaard N.C., Ferreira J.F., Hermansen J.E. Use of Artemisia annua as a natural coccidiostat in free-range broilers and its effects on infection dynamics and performance. Vet. Parasitol. 2012;186:178–187. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]