Abstract

This study examines parental intention to vaccinate children against COVID-19 and related sociodemographic factors in a national sample of US parents.

In September 2021, one-fourth of the COVID-19 cases in the US were among children.1 Vaccinating children against COVID-19 is the most effective way to reduce disease burden and ensure safe return to in-person schooling and other social activities. National surveys show hesitancy among parents to vaccinate children,2,3 even when they are vaccinated themselves.4 We measured parental intention to vaccinate children and related sociodemographic factors in a national sample of US parents.

Methods

The CHASING COVID study, a nationwide cohort study, was launched in March 2020 to understand how the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has affected communities in the US.5 US residents 18 years or older were recruited and consented online. The cohort captures longitudinal information on COVID-related exposures, outcomes, vaccine uptake, and other behavioral factors. Responses from the June 2021 survey round were analyzed. The study was approved by the City University of New York Institutional Review Board.

Parents of children aged 2 to 17 years were asked if they would immediately vaccinate their children when eligible (yes/no). Additionally, parents of children aged 12 to 17 years were asked about each child’s vaccination status (vaccinated/unvaccinated). The vaccine hesitancy status of parents was dichotomized as “vaccine hesitant” (responded they would delay or never get the COVID-19 vaccine) and “vaccine willing/vaccinated” (vaccinated or willing to vaccinate immediately). Responses from previous survey rounds for parental vaccine hesitancy were used to replace missing values in the June 2021 survey.

χ2 Tests were used to compare intention to vaccinate children immediately between vaccine-willing and vaccine-hesitant parents, with statistical significance defined as 2-sided P < .05. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to assess sociodemographic and behavioral correlates of intention to vaccinate children.

Results

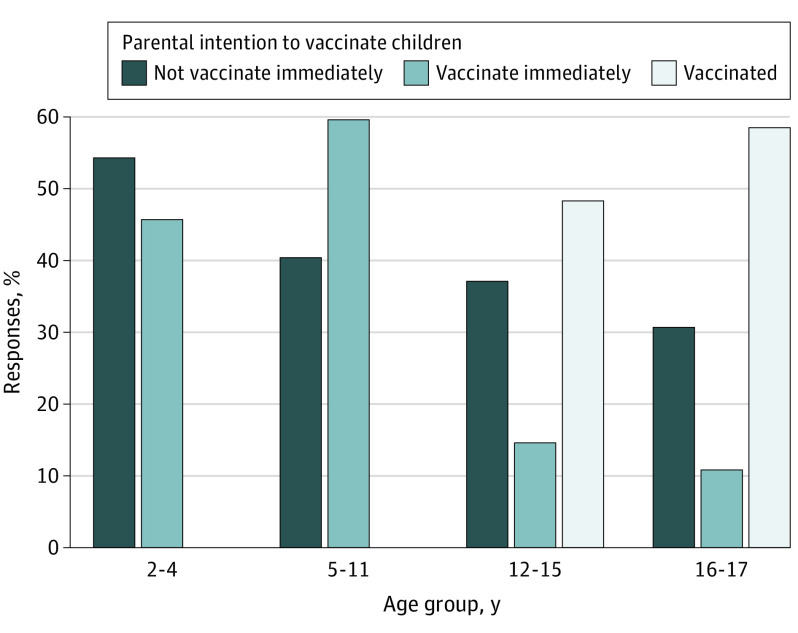

The analysis included 1162 parents (mean [SD] age, 40.6 [15.3] years) with 1651 children aged 2 to 17 years. In June 2021, 842 parents (74.4%) were already vaccinated/vaccine-willing, while 298 (25.6%) were vaccine hesitant. A total of 212 children (48%) aged 12 to 15 years and 135 (58%) aged 16 to 17 years reportedly received at least 1 dose of the COVID-19 vaccine (Figure). Vaccine-willing/vaccinated parents were more likely to have already vaccinated their eligible children or intended to immediately vaccinate them when they become eligible, compared with vaccine-hesitant parents (64.9% vs 8.3% for children aged 2-4 years; 77.6% vs 12.1% for those aged 5-11 years; 81.3% vs 13.9% for those aged 12-15 years; and 86.4% vs 12.7% for those aged 16-17 years; all P < .001). Among vaccine-willing/vaccinated parents, 10% would not immediately vaccinate their children. The most common reason for hesitancy was concern about vaccine-related long-term adverse effects in children.

Figure. Parents’ Intention to Vaccinate Children Aged 2 to 17 Years as of June 2021 in the CHASING COVID Cohort.

Parents’ intention to vaccinate immediately and the percentage of children vaccinated was higher for older children for whom the COVID-19 vaccine is already approved. A COVID-19 vaccine was not yet approved for children younger than 12 years at the time of the survey; hence, no children younger than 12 years has been vaccinated.

Black and Hispanic parents showed lower willingness to immediately vaccinate children compared with parents who were non-Hispanic White, women, younger, and did not have a college education (Table). Parents of school-aged children indicated higher willingness to vaccinate them if they currently attended school partially or fully remotely vs fully in-person. Parents with a prior COVID-19 infection or who knew someone who died of COVID-19 reported higher willingness to vaccinate their children.

Table. Correlates of Intention to Vaccinate Children Immediately Among 1162 Parents of Children Aged 2 to 17 in the USa.

| Parental characteristic | Child age group, y | All age groups | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-4 (n = 317) | 5-11 (n = 659) | 12-15 (n = 443) | 16-17 (n = 232) | |||||||

| aOR (95% CI) | P value | aOR (95% CI) | P value | aOR (95% CI) | P value | aOR (95% CI) | P value | aOR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age group, y | ||||||||||

| 18-29 | 0.3 (0.1-0.6) | <.001 | 0.8 (0.4-1.4) | .44 | 0.9 (0.3-2.5) | .78 | NA | NA | 0.7 (0.5-1.1) | .09 |

| 30-39 | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 40-49 | 1.4 (0.6-3.3) | .37 | 2.0 (1.2-3.4) | <.01 | 2.5 (1.5-4.5) | <.01 | 1.1 (0.4-2.7) | .88 | 1.6 (1.1-2.2) | <.01 |

| 50-59 | 1.9 (0.3-14.3) | .53 | 1.8 (0.6-6.6) | .33 | 1.9 (0.9-4.3) | .10 | 0.9 (0.3-3.0) | .85 | 1.8 (1.1-3.1) | .02 |

| ≥60 | 0.5 (0.01-8.8 | .67 | 1.4 (0.4-7.3) | .61 | 0.7 (0.2-2.7) | .63 | 0.4 (0.1-2.2) | .30 | 0.6 (0.3-1.3) | .20 |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 0.5 (0.2-1.2) | .12 | 1.1 (0.4-2.9) | .89 | 1.9 (0.7-6.1) | .25 | 1.0 (0.2-7.8) | .98 | 1.4 (0.8-2.5) | .20 |

| Hispanic | 0.3 (0.1-0.6) | <.001 | 0.7 (0.5-1.2) | .25 | 1.1 (0.6-1.9) | .85 | 0.4 (0.1-1.0) | .05 | 0.7 (0.5-1.04) | .08 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.3 (0.1-0.9) | .03 | 0.6 (0.3-1.1) | .12 | 0.4 (0.2-0.9) | .02 | 0.1 (0.01-0.2) | <.001 | 0.4 (0.3-0.6) | <.001 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Otherb | 0.3 (0.1-0.9) | .04 | 0.6 (0.2-1.5) | .24 | 1.0 (0.4-3.0) | .90 | 0.4 (0.1-1.9) | .22 | 0.5 (0.3-1.05) | .07 |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Women | 0.4 (0.2-0.8) | .01 | 0.6 (0.4-0.97) | .04 | 0.6 (0.4-1.1) | .11 | 0.7 (0.2-1.7) | .39 | 0.5 (0.3-0.7) | <.001 |

| Men | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Loss of income due to childcare | ||||||||||

| Yes | 0.9 (0.4-1.9) | .80 | 0.6 (0.4-1.04) | .07 | 0.6 (0.3-1.2) | .12 | 0.3 (0.1-0.96) | .04 | 0.7 (0.5-1.01) | .06 |

| No | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Education | ||||||||||

| High school or less | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Some college or graduate school | 2.5 (1.1-6.5) | .04 | 2.5 (1.5-4.3) | <.001 | 2.5 (1.4-4.5) | <.01 | 2.0 (0.7-5.3) | .18 | 2.7 (1.8-3.9) | <.001 |

| School type for all children in household | ||||||||||

| In-person | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Children too young | 1.3 (0.6-2.8) | .51 | 4.0 (1.0-27.4) | .08 | 3.1 (0.4-66.8) | .35 | NA | NA | 0.8 (0.7-1.3) | .50 |

| Attend remotely | 0.8 (0.3-1.9) | .58 | 1.7 (1.0-2.8) | .05 | 2.7 (1.5-5.2) | <.01 | 2.5 (0.9-7.3) | .07 | 1.5 (1.05-2.1) | .02 |

| Attend a hybrid model | 1.4 (0.5-4.0) | .47 | 2.3 (1.3-4.2) | <.01 | 2.5 (1.3-4.7) | <.01 | 2.2 (0.8-6.3) | .13 | 1.8 (1.2-2.7) | <.01 |

| Otherc | 0.6 (0.2-1.8) | .33 | 0.7 (0.4-1.5) | .34 | 0.7 (0.3-1.9) | .52 | 0.8 (0.2-2.8) | .68 | 0.8 (0.5-1.4) | .40 |

| Worry about others getting infected with COVID-19d | ||||||||||

| No | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Yes | 1.6 (0.9-3.0) | .10 | 2.2 (1.5-3.3) | <.001 | 1.0 (0.6-1.6) | .94 | 1.4 (0.7-3.0) | .37 | 1.6 (1.2-2.1) | <.001 |

| Past COVID-19 diagnosise | ||||||||||

| No | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Yes | 3.0 (1.2-7.6) | .01 | 1.1 (0.6-1.9) | .76 | 1.3 (0.6-2.6) | .51 | 2.1 (0.8-6.4) | .16 | 1.5 (1.0-2.3) | .05 |

| Know someone who died of COVID-19f | ||||||||||

| No | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Yes | 1.2 (0.7-2.2) | .48 | 1.8 (1.2-2.7) | <.01 | 1.7 (1.1-2.8) | .03 | 1.0 (0.4-2.1) | .93 | 1.5 (1.2-2.1) | <.01 |

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio; NA, not applicable.

Intention to vaccinate children was measured as a binary variable (immediately vs not immediately). Children aged 12 to 17 years who were already vaccinated were grouped with the “vaccinate immediately” category, assuming that if children were already vaccinated then their parents intended to vaccinate them immediately. In addition to the factors presented in the table, multivariable models were adjusted for occupation and presence of younger siblings in the household.

Participants who chose Native American, other, or unknown.

Includes homeschooling and other.

Coded as yes if participants responded they were “not at all worried” or “not too worried” and no if participants responded that they were “somewhat worried” or “very worried.”

Coded as yes if participants self-reported a laboratory confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis between surveys rounds 1 through 9.

Coded as yes if participants reported that they knew someone who died of COVID-19 between survey rounds 1 through 9.

Discussion

Parental hesitancy to vaccinate children against COVID-19 differs by parental race and ethnicity, gender, education level, and previous experience with COVID-19 and the child's age. Perhaps unsurprisingly, parents who were hesitant to be vaccinated themselves were hesitant to vaccinate their children; however, some vaccinated parents also reported concerns about vaccinating children. Study limitations include social desirability and recall bias due to self-reported responses and limited generalizability to the US population.

Parental vaccine hesitancy is a major issue for schools resuming in-person instruction, potentially requiring regular testing, strict mask wearing, and physical distancing for safe operation.6 Transparent messaging by public health agencies about safety of COVID-19 vaccines among children is critical to increase vaccine uptake and address parents’ concerns about vaccine adverse effects. Future research should focus on changes in vaccination uptake when COVID-19 vaccines receive full approval and younger age groups become eligible for vaccination.

References

- 1.Children and COVID-19: state-level data report.; American Academy of Pediatrics . Accessed September, 23 2021. https://www.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/children-and-covid-19-state-level-data-report/

- 2.Szilagyi PG, Shah MD, Delgado JR, et al. Parents’ intentions and perceptions about COVID-19 vaccination for their children: results from a national survey. Pediatrics. 2021;148(4):e2021052335. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruggiero KM, Wong J, Sweeney CF, et al. Parents’ intentions to vaccinate their children against COVID-19. J Pediatr Health Care. 2021;35(5):509-517. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2021.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teasdale CA, Borrell LN, Kimball S, et al. . Plans to vaccinate children for COVID-19: a survey of United States parents. J Pediatr. 2021;237:292-297. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.07.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robertson MM, Kulkarni SG, Rane M, et al. ; CHASING COVID Cohort Study Team . Cohort profile: a national, community-based prospective cohort study of SARS-CoV-2 pandemic outcomes in the USA-the CHASING COVID Cohort study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(9):e048778. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-048778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jehn M, McCullough JM, Dale AP, et al. Association between K-12 school mask policies and school-associated COVID-19 outbreaks: Maricopa and Pima counties, Arizona, July-August 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(39):1372-1373. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7039e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]