Abstract

Meta-analysis of >87,000 patients demonstrates that patients with invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast are far less likely to achieve pCR of the breast or axilla compared to their ductal counterparts, receive less BCS and more frequently return positive margins.

Background

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) facilitates tumour downstaging, increases breast conserving surgery (BCS) and assesses tumour chemosensitivity. Despite clinicopathological differences in Invasive Ductal Carcinoma (IDC) and Invasive Lobular Carcinoma (ILC), decision making surrounding the use NACT does not take account of histological differences.

Aim

To determine the impact NACT on pathological complete response (pCR), breast conserving surgery (BCS), margin status and axillary pCR in ILC and IDC.

Methods

A systematic review was performed in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines. Studies reporting outcomes among ILC and IDCs following NACT were identified. Dichotomous variables were pooled as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals_(CI) using the Mantel-Haenszel method. P-values <0.05 were statistically significant.

Results

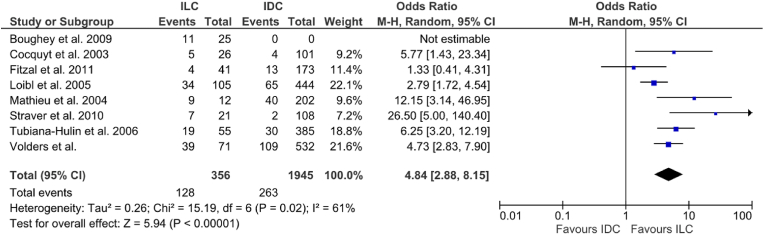

40 studies including 87,303 (7596 ILC [8.7%]and 79,708 IDC [91.3%]) patients were available for analysis. Mean age at diagnosis was 54.9 vs. 50.9 years for ILC and IDC, respectively. IDCs were significantly more likely to achieve pCR (22.1% v 7.4%, OR: 3.03 [95% CI 2.5–3.68] p < 0.00001), axillary pCR (23.6% vs. 13.4%, OR: 2.01 [95% CI 1.77–2.28] p < 0.00001) and receive BCS (45.7% vs. 33.3%, OR 2.14 [95% CI 1.87–2.45] p < 0.00001) versus ILCs. ILCs were significantly more likely to have positive margins at the time of surgery (36% vs 13.5%, OR 4.84 [95% CI 2.88–8.15] p < 0.00001).

Conclusion

This is the largest study comparing the impact of NACT among ILC and IDC with respect to pCR and BCS. ILC has different outcomes to IDC following NACT and incorporate it into treatment decisions and future clinical guidelines.

Highlights

-

•

Ductal cancers (IDC) achieved higher rates of pCR (22% v 7%, Odds Ratio (OR): 3.03).

-

•

Breast conservation surgery was more common in IDC (46% v 33%, OR: 2.14).

-

•

Lobular cancers had higher margin positivity rates at surgery (36% vs 14%, OR 4.84).

-

•

These findings should be considered in treatment decisions for future ILC patients.

1. Introduction

Invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) is the second most common histological subtype of breast cancer, accounting for approximately 5–15% of diagnoses worldwide [[1], [2], [3]]. In spite of representing a minority share among breast cancers, the incidence of ILC is comparable to malignant melanoma or ovarian cancers, indicating that it as a significant contributor to the global cancer burden [4]. ILCs have distinct clinicopathological characteristics; they have the tendency to be large, multifocal, slow growing tumours, which are often mammographically occult. They are almost exclusively hormone sensitive tumours and present in older patients [5]. ILCs infiltrate the affected breast widely, by radiating through the surrounding stroma in a linear pattern of single cells. This growth pattern avoids the anatomical disruption seen in invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) and an attenuated stromal reaction fails to produce the classic breast ‘lump’, making clinical and radiological detection challenging to the surgical oncologist [1].

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) is now a well-established component of breast cancer treatment involving the administration of cytotoxic chemotherapy in the preoperative setting. Advantages to NACT include tumour downstaging in the setting of locally-advanced stage IIB/III disease, or cases where women hope to achieve BCS, despite not currently being a suitable candidate due to increased tumour to breast ratio [6], and international guidelines now recommend NACT administration in the aforementioned scenarios [7,8]. At present, no guidelines provide physicians with advice in relation to the optimal approach to cytotoxic chemotherapy prescription specifically in lobular histology. Surgery remains the most important single intervention in breast cancer management. In the era of multi-disciplinary management, the selection of the right operation for the right patient can be significantly impacted by the use of NACT.

Despite considerable heterogeneity in the spectrum of breast carcinoma [9], the modern paradigm rarely includes histopathological tumour subtype in therapeutic decision making when considering conventional chemotherapy prescription [10]. Patients with both ILC and IDC histology are equally likely to be indicated to undergo NACT, despite ILC being renowned for de novo chemoresistance, with very few achieving pathological complete response (pCR) [11,12]. Furthermore, data suggest ILC are less likely to successfully downstage to achieve BCS [13,14]. Despite this, NACT remains a fundamental therapeutic option for treating ILC.

While previous studies focus upon the ascertainment of pCR and conversion to BCS as primary analytical endpoints [15], recent large volume data suggests updated pooled analyses should be performed comparing the clinical value of NACT in ILC versus IDC. Accordingly, the aim of the current systematic review and meta-analysis was to determine rates of breast and axillary pCR as well as successful BCS rates following NACT in patients with ILC and IDC and how those outcomes may influence surgical decision making within the context of multi-disciplinary care.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy

A systematic review was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist and Meta-Analyses of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines [16,17]. A comprehensive, electronic search was conducted of the SCOPUS, EMBASE, PUBMED and Web of Science databases, along with the Cochrane Library on the October 8, 2020. Studies were considered for analysis if the following search terms were identified in their titles or abstracts; “Lobular” AND “Ductal” AND “Breast” AND “Neoadjuvant”. Secondary referencing was conducted through manually reviewing the reference lists of potentially eligible studies. Studies were not limited according to their year or language of publication. Initial screening was conducted of all titles with subsequent assessment of abstracts. Studies deemed appropriate had their full text reviewed. In studies where the data was potentially derived from the same patient population, the study with the most relevant outcomes was included in the analysis.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were considered for inclusion if the following inclusion criteria were met [1]: included patients with a diagnosis of invasive lobular or invasive ductal carcinoma [2], patients were administered chemotherapy prior to surgical intervention (neoadjuvant chemotherapy) [3], patient outcome data was reported on any of the following; (a) pCR to NACT in breast, (b) surgical intervention undertaken following completion of chemotherapy, (c) pCR to NACT within the axillary nodes, (d) margin status following the index surgical procedure, (e) the surgical management of the axilla. Studies were excluded from the analysis if any of the following criteria were met [1]: Studies reporting outcomes not within the remit of the current study [2] Data not specified according to histological subtype [3], review articles [4], case reports or studies with less than 10 patients [5], editorials or [6] conference abstracts without a published full text.

2.3. Data extraction and quality assessment

The literature search was conducted independently by the first and second authors (DO’C and MGD) using the predefined search strategy. This predetermined search strategy was designed by the senior author (MJK). Duplicates were removed and manuscripts were retrieved in accordance with the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria as detailed above. The following data was extracted from full text manuscripts [1]; First author name [2], year of publication [3], type of study [4], total number of patients and number within each subtype [5], clinicopathological features of enrolled subjects [6] NACT regimen and number of cycles [7], type of surgery performed; index operation and any reoperations required [8], proportion of patients achieving breast pCR and/or axillary pCR. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale was employed to assess study bias and methodology quality [18]. In all cases a consensus was achieved between the first and second author. The senior author (MJK) reviewed any case where a consensus could not be achieved. Studies publishing data thought to be from the same source were assessed for the potential overlap of patient data. Where a risk of overlap was identified, one study was selected for inclusion based on relevance.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Comparisons between the ILC and IDC cohorts were assessed as dichotomous data using the Mantel-Haenszel methods. Results were expressed as odds ratios (OR) and 95% Confidence intervals. I2 statistics were used to assess heterogeneity between studies and where indicated, a random-effects model was used in this analysis. Categorical variables were assessed by Chi-squared test (χ2). Statistical significance was considered to be a p value of <0.05 and statistical analysis was performed using Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.4.1.

3. Results

3.1. Literature search

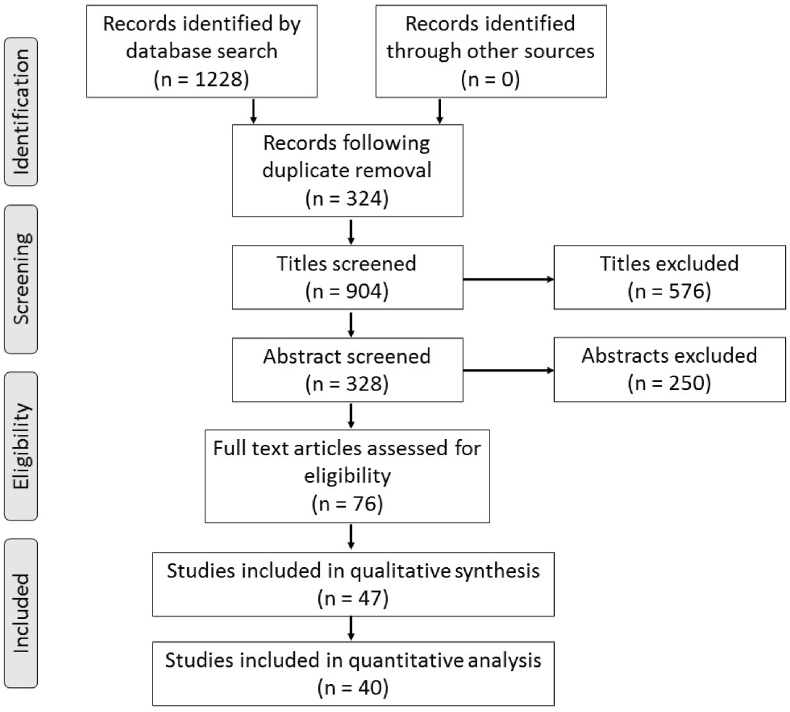

Employing our search strategy across the 5 databases identified 1228 records for potential inclusion. Of these, 324 duplicate records were removed, leaving 904 titles to be screened for relevance. Screening of titles and their associated abstracts resulted in 76 full text articles to be reviewed, of which, 47 and 40 were included in the qualitative and quantitative analysis respectively [[19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58]]. The process of study selection is summarised in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the study selection process.

3.2. Study characteristics

In total, this analysis included 87,303 patients who received NACT for ILC or IDC. Of these, 7596 received NACT for ILC (8.7%) and 79,708 for IDC (91.3%). The mean age at diagnosis was 51.1 years and the mean age of ILC cases was 4 years older than IDC (54.9 vs. 50.9 years). Included in the meta-analysis were 4 randomised controlled trials, 13 prospective studies and 19 retrospective studies. Included studies were of moderate to good quality with Newcastle-Ottawa scores ranging from 5 to 7. Overall, 31 studies reported pCR rates following NACT (Table 1a) and 4 studies reported rates of axillary pCR (Table 1b). There were 18 studies reporting BCS rates following NACT (Table 2a) and 7 studies included data on the margin status of the surgical specimen (Table 2b).

Table 1a.

Studies included in the assessment of pCR.

| Author/Year | Type of study | No. pts. (ILC vs IDC) | Inclusion criteria (TNM and subtype) | Neoadjuvant regime | No. of cycles | pCR definition | Newcastle – Ottawa Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alamgeer et al., 2014 | Randomised Controlled Trial | 11 vs. 108 | T1-3, N0-3, M0 Mixed | FEC and Docetaxel | 4 and 4 | No invasive in breast or axilla | 7 |

| Boidot et al., 2009 | Prospective Cohort | 1 vs. 28 | T1-3, N0-3, M0 Mixed | FEC, Docetaxel and Epirubicin | 6 and 6 | No invasive in breast or axilla | 6 |

| Bollet et al., 2008 | Retrospective Cohort | 68 vs. 672 | T2-3, N0-1, M0 Mixed | Anthracycline | 1–6 | N/a | 6 |

| Chan et al., 2011 | Prospective Cohort | 6 vs. 42 | T3/4, T1-4 N1–3, M0 Mixed | TAC | 6 | No invasive in breast or axilla | 5 |

| Cocquyt et al., 2003 | Prospective Cohort | 26 vs. 101 | >3 cm Mixed | CMF and CAF | 3 | No invasive in breast | 7 |

| Cristofanilli et al., 2005 | Retrospective Cohort | 122 vs. 912 | T1-3, N0-2, M0 Mixed | CVAP, CAF and taxane | 4–8 | No invasive in breast or axilla | 6 |

| Dave et al., 2017 | Prospective Cohort | 20 vs. 223 | T1-3, N0-2 Mixed | Epirubicin, cyclophosphamide and docetaxel/paclitaxel | 6 | No invasive in breast | 7 |

| De Los Santos et al., 2013 | Retrospective Cohort | 61 vs. 637 | T1-3, N0-3 Mixed | AC-T, Carboplatin, Bevacizumab, Trastuzumab | Varied | No invasive or in situ in breast | 7 |

| Delpech et al., 2013 | Retrospective Cohort | 177 vs. 1718 | T1-4, N0-1, M0 ER+, HER2 ± | Anthracycline, Taxane, Trastuzumab | Varied | No invasive in breast or axilla | 6 |

| Fisher et al., 2012 | Retrospective Cohort | 7 vs. 120 | T1-4, N0-3 TNBC | Adriamycin, Taxane | Varied | No invasive in breast | 6 |

| Fitzal et al., 2011 | Retrospective Cohort | 67 vs. 258 | T1-4, N0-1, M0 Mixed | CMF, ED, EDC, pegfilgastrim | Varied | No invasive in breast or axilla | 7 |

| Gahlaut et al., 2016 | Prospective Cohort | 12 vs. 180 | T1-4, N0-1, M0 Mixed | Anthracycline, Taxane, Trastuzumab | 6 | No invasive in breast | 6 |

| Gentile et al., 2017 | Prospective Cohort | 22 vs. 276 | T4, T1-4 and N1-3, M0 Mixed | AC-T, Trastuzumab and Pertuzumab | Varied | No invasive in breast or axilla | 7 |

| Goldstein et al., 2007 | Retrospective Cohort | 3 vs. 65 | T1-3 and N0-3 Mixed | Anthracycline, 5-FU, Taxane, Trastuzumab | Varied | No invasive in breast | 6 |

| Keskin et al., 2011 | Retrospective Cohort | 24 vs. 294 | T1-4,N0-3, M0 Mixed | Anthracycline | Varied | No invasive or in situ breast or axilla | 6 |

| Lips et al., 2011 | Prospective Cohort | 46 vs. 157 | T1-4, N0-3 Mixed | AC and CD | 6 | No invasive in breast or axilla | 7 |

| Lips et al., 2012 | Prospective Cohort | 75 vs. 601 | T1-4, N0-3, M0 Mixed | AC, ACT and Trastuzumab | 6 | No invasive in breast or axilla | 6 |

| Mathieu et al., 2004 | Prospective Cohort | 38 vs. 419 | T2-4, N0-2, M0 Mixed | AVCMF, CAF and FEC | 3 or 4 | No invasive in breast | 7 |

| Nagao et al., 2011 | Retrospective Cohort | 29 vs. 500 | T2-4, N0-2 Mixed | FEC, AC, AT, wPTX and Trastuzumab | 4 and 12 | No invasive in breast | 7 |

| Petruola et al., 2017 | Retrospective Cohort | 91 vs. 310 | T1-4, N0-3 ER/PR + HER2- | NA | NA | No invasive or in suite in breast or axilla | 6 |

| Pu et al., 2005 | Prospective Cohort | 3 vs. 41 | T1-4, N0-3, M0 Mixed | Doxorubicin and Docetaxel | 4 | No invasive in breast | 6 |

| Reitsamer et al., 2005 | Randomised Controlled Trial | 7 vs. 38 | T1-4, N0-3, M0 Mixed | Epidoxorubicin and Docetaxel | 3 or 6 | No invasive in breast | 7 |

| Riba et al., 2018 | Retrospective Cohort | 2417 vs. 47,697 | T1-4, N0-3, M0 Mixed | Varied | Varied | No invasive in breast | 7 |

| Sinn et al., 1994 | Randomised Controlled Trial | 11 vs. 35 | NA | Epirubicin and Cyclophosphamide | NA | No invasive or in situ in breast | 6 |

| Straver et al., 2010 | Retrospective Cohort | 37 vs. 197 | T1-3, N0-1, M0 Mixed | AC, CD, PTC, AD | 6 and 3 | No invasive in breast or axilla | 7 |

| Sullivan et al., 2009 | Retrospective Cohort | 9 vs. 40 | T1-4, N0-3 Mixed | CD, AC, ADC, ACP | Varied | No invasive in the breast or axilla | 6 |

| Tubiana-Hulin et al., 2006 | Retrospective Cohort | 118 vs. 742 | T2-4, N0-2, M0 Mixed | Anthracycline based Varied | Varied | No invasive in breast or axilla | 6 |

| Untch et al., 2011 | Prospective Cohort | 13 vs. 189 | T1-4, N0-3, M0 HER2+ | Epirubicin/Cyclophosphamide and Paclitaxel/Trastuzumab | 3 and 3 | No invasive in breast or axilla | 6 |

| Vugts et al., 2017 | Retrospective Cohort | 39 vs. 279 | T1-4, N0-3, M0 Mixed | TAC, AC-T ± Trastuzumab | NA | No invasive or in situ in the breast | 6 |

| Wenzel et al., 2007 | Prospective Cohort | 37 vs. 124 | T0-3, N0-3, M0 Mixed | Epidoxorubicin and Docetaxel | NA | No invasive in breast | 7 |

FEC: 5-FU, Epirubicin and Cyclophosphamide, AC-T: Doxorubicin, Cyclophosphamide and Taxane, TAC: Docetaxel, Doxorubicin and Cyclophosphamide, CMF: Cyclophosphamide, Methotrexate and 5-FU, CAF: Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin and 5-FU, CVAP: Cyclophosphamide, Vincristine, Doxorubicin and Prednisalone, ED: Epirubicin, Docetaxel, EDC: Epirubicin, Docetaxel and Capecitabine, EC-D: Epirubicin, Docetaxel and Cyclophosphamide, AC: Doxorubicin and Cyclophosphamide, AVCMF: Doxorubicin, Vincristine, Cyclophosphamide, Methotrexate and 5-FU, AT: Doxorubicin and Paclitaxel, wPTX: Paclitaxel, PTC: Paclitaxel, Traztusumab and Carboplatin, AD: Doxorubicin and Docetaxel, ACP: Doxorubicin, Cyclophosphamide and Paclitaxel, CD: Cyclophosphamide and Doxorubicin, ADC: Doxorubicin, Docetaxel and Cyclophosphamide.

Table 1b.

Studies included in the assessment of axillary pCR.

| Author/Year | Type of Study | N. pts. (ILC vs. IDC) | Inclusion criteria (TNM and subtype) | Definition of axillary pCR | No. Axillary pCR | Newcastle – Ottawa Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tubiana-Hulin et al., 2006 | Retrospective Cohort | 118 vs. 742 | T2-4, N0-2, M0 Mixed | No invasive in axillary nodes | 304 | 6 |

| Petruola et al., 2017 | Retrospective Cohort | 91 vs. 310 | T1-4, N0-3 ER/PR + HER2- | No invasive or in situ in axillary nodes | 44 | 6 |

| Vugts et al., 2017 | Retrospective Cohort | 39 vs. 279 | T1-4, N0-3, M0 Mixed | No micro/macro-metastases in nodes | 59 | 6 |

| Zeidman et al., 2020 | Retrospective Cohort | 3718 vs. 21,397 | T1-4, N0-3, M0 ER/PR + HER- | No invasive in axillary nodes | 3537 | 7 |

Table 2a.

Studies included in assessment BCS vs. Non BCS.

| Author/Year | Type of study | No. pts. (ILC vs IDC) | Inclusion criteria (TNM and subtype) | % Receiving BCS | % Not Receiving BCS | Newcastle – Ottawa Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bollet et al., 2008 | Retrospective Cohort | 68 vs. 672 | T2-3, N0-1, M0 Mixed | 57% | 43% | 6 |

| Boughey et al., 2009 | Retrospective Cohort | 84 (ILC only) | T1-4, N0-3, M0 | 30% | 70% | 6 |

| Cho et al., 2013 | Retrospective Cohort | 6 vs. 407 | T1-3, N0-3, M0 Mixed | 28% | 72% | 7 |

| Cocquyt et al., 2003 | Prospective Cohort | 26 vs. 101 | >3 cm Mixed | 47% | 53% | 7 |

| Cristofanilli et al., 2005 | Retrospective Cohort | 122 vs. 912 | T1-3, N0-2, M0 Mixed | 31% | 69% | 6 |

| Delpech et al., 2013 | Retrospective Cohort | 177 vs. 1718 | T1-4, N0-1, M0 ER+, HER2 ± | 33% | 67% | 6 |

| Fitzal et al., 2011 | Retrospective Cohort | 67 vs. 258 | T1-4, N0-1, M0 Mixed | 66% | 33% | 7 |

| Grover et al., 2017 | Retrospective Cohort | 130 vs. 4251 | T1-3, N1-3, M0 Mixed | 42% | 58% | 7 |

| Gusic et al., 2018 | Retrospective Cohort | 17 vs. 133 | T1-4, N0-3, M0 Mixed | 68% | 32% | 6 |

| Lips et al., 2012 | Prospective Cohort | 75 vs. 601 | T1-4, N0-3, M0 Mixed | 45% | 55% | 6 |

| Loibl et al., 2006 | RCT | 105 vs. 444 | T2-3, N0-2, M0 Mixed | 75% | 25% | 6 |

| Mathieu et al., 2004 | Prospective Cohort | 38 vs. 419 | T2-4, N0-2, M0 Mixed | 43% | 57% | 7 |

| Nagao et al., 2011 | Retrospective Cohort | 29 vs. 500 | T2-4, N0-2 Mixed | 50% | 50% | 7 |

| Petruola et al., 2017 | Retrospective Cohort | 91 vs. 310 | T1-4, N0-3 ER/PR + HER2- | 41% | 59% | 6 |

| Rouzier et al., 2004 | Retrospective Cohort | 67 vs. 527 | T2-3, N0-2, M0 Mixed | 48% | 52% | 6 |

| Straver et al., 2010 | Retrospective Cohort | 37 vs. 197 | T1-3, N0-1, M0 Mixed | 50% | 50% | 7 |

| Tubiana-Hulin et al., 2006 | Retrospective Cohort | 118 vs. 742 | T2-4, N0-2, M0 Mixed | 51% | 49% | 6 |

| Wenzel et al., 2007 | Prospective Cohort | 37 vs. 124 | T0-3, N0-3, M0 Mixed | 73% | 27% | 7 |

Table 2b.

Studies included in assessment of margin status.

| Author/Year | Type of study | No. pts. (ILC vs IDC) | Inclusion criteria (TNM and subtype) | Definition of clear surgical margin | No. Involved Surgical Margins | No. Clear Surgical Margin | Newcastle – Ottawa Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loibl et al., 2006 | RCT | 105 vs. 444 | T2-3, N0-2, M0 Mixed | No invasive or in situ at surgical margin | 99 | 450 | 6 |

| Fitzal et al., 2011 | Retrospective Cohort | 67 vs. 258 | T1-4, N0-1, M0 Mixed | Tumor margin of >1 mm | 17 | 197 | 7 |

| Tubiana-Hulin et al., 2006 | Retrospective Cohort | 118 vs. 742 | T2-4, N0-2, M0 Mixed | Not provided by authors | 49 | 391 | 6 |

| Straver et al., 2010 | Retrospective Cohort | 37 vs. 197 | T1-3, N0-1, M0 Mixed | Tumor margin of >2 mm | 9 | 120 | 7 |

| Mathieu et al., 2004 | Prospective Cohort | 38 vs. 419 | T2-4, N0-2, M0 Mixed | No invasive at surgical margin | 49 | 165 | 7 |

| Boughey et al., 2009 | Retrospective Cohort | 84 (ILC only) | T1-4, N0-3, M0 | Not provided by authors | 11 | 13 | 6 |

| Volders et al., 2016 | Retrospective Cohort | 71 vs. 532 | Mixed | No invasive at surgical margin | 152 | 474 | 6 |

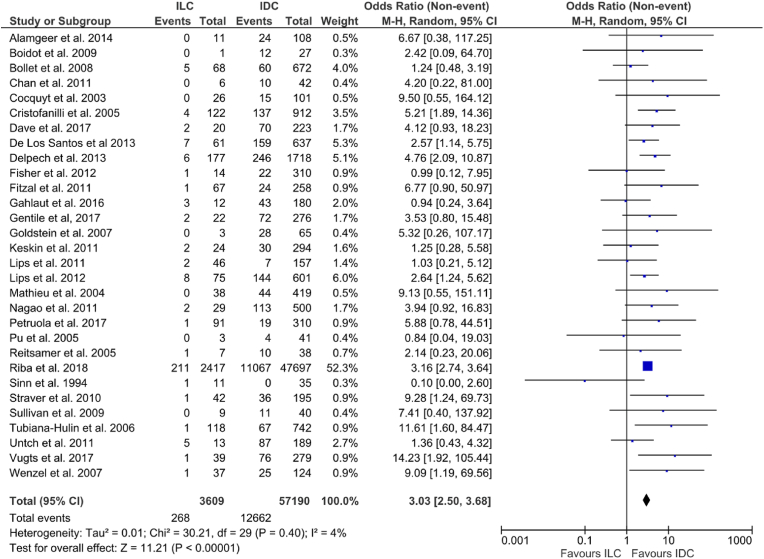

3.3. Breast pathological complete response

Overall, pCR following NACT was 21% across all cases (12,930/60,799). Rates of pCR for ILC ranged from 0 to 38.5% and 0–46% for IDC among included studies. The pooled pCR rate was 7.4% for ILC and 22.1% for IDC. Patients with IDC were more likely to achieve breast pCR (OR: 3.03, 95% CI: 2.5–3.68, p < 0.00001, I2 = 4%) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Forrest plot of odds ratio (OR) and 95% Confidence Interval (CI) for pathological complete response (pCR) in invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) vs. invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) breast cancer patients following neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT).

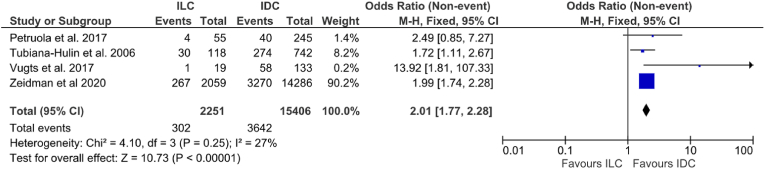

3.4. Axillary pathological complete response

Four studies including 17,657 patients provided data in relation to axillary pCR following NACT:. Overall, axillary pCR was 22.3% among all patients (3944/17,657). Rates of axillary pCR ranged from 5.3% to 25.4% for ILC and 16.3%–43.6% for IDC. Patients with IDC were more likely to achieve breast pCR (13.4% vs. 23.6% [OR: 2.01, 95% CI: 1.77–2.28, p < 0.00001, I2 = 27%] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Forrest plot of odds ratio (OR) and 95% Confidence Interval (CI) for the rates of axillary pathological complete response (pCR) in invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) vs. invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC).

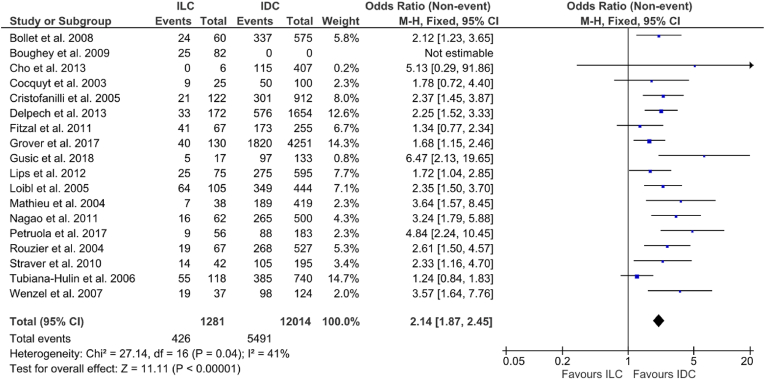

3.5. Breast conserving surgery

Overall, BCS was performed in 44.5% (5917/13,295) of cases. BCS in ILC varied from 0%–61.1% and from 28.2% to 79% in IDC. Patients with IDC were more likely to undergo BCS [33.3% vs. 45.7% (OR: 2.14, 95% CI: 1.87–2.45, p < 0.00001), I2 = 41%] (Fig. 4.) Seven studies including 643 ILCs and 4420 IDCs reported on tumour staging and size; 52.0% of ILCs and 35.3% of IDCs were T3-4 (p < 0.00001, χ2).

Fig. 4.

Forrest plot of odds ratio (OR) and 95% Confidence Interval (CI) for the rates of breast conserving surgery (BCS) in invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) vs. invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC).

3.6. Positive surgical margins following excision

Eight studies provided information on 2301 patients regarding the success of the index operation following NACT, either by reporting the margin status directly or the proportion of cases requiring re-operation for incomplete excision. Of the included studies, there was an overall margin positivity rate of 17% (391/2301). Among the individual studies margin positivity ranged from 9.8% to 75% in ILC vs. 4%–19.8% in IDCs. Patients with ILC were more likely to have positive margins [36% vs.13.5% (OR: 4.84, 95% CI 2.88–8.15, p < 0.00001) I2 = 61%] (Fig. 5). No further analysis was made on the distinction between the type of index operation (BCS vs. mastectomy) or reoperation (Re-excision of involved margins vs. completion mastectomy).

Fig. 5.

Forrest plot of odds ratio (OR) and 95% Confidence Interval (CI) for the rates of positive margins post resection in invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) vs. invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC).

3.7. Molecular subtype

Expression of ER, PR and HER2 receptor is of paramount importance when considering the response of IDC and ILC to NACT. Among the included studies 6 studies provided detail of hormone and HER2 receptor status among their included patients [25,29,31,39,42,47]. Receptor status was not reported consistently across all 6 studies and outcomes of were not stratified according to ILC and IDC molecular subtypes. As such, a pooled analysis was not possible from the available data. Among individual studies, IDC had a greater proportion of HER2 enriched and triple negative breast cancer, while ILC had a greater proportion of hormone sensitive tumours (Supplementary Table 1.)

4. Discussion

This is the largest study of its kind, including a number of large, recent studies not yet incorporated into a meta-analysis such as this [19,28,32,33,35,44,47,54,55,57,58]. The additional studies have enabled the authors to refine inclusion criteria, disregarding conference abstracts in favour of peer reviewed articles only, a discretion not afforded previous authors [15]. This analysis updates pCR and BCS rates while adding additional outcomes (i.e.: margin status and axillary pCR), in our appraisal of the oncological and surgical outcomes following NACT prescription in cases of ILC versus IDC.

In this analysis, overall pCR rates were more likely in IDC patients in receipt of NACT than their ILC counterparts (OR: 3.03, 95% CI: 2.50–3.68). pCR following NACT is a renowned biomarker of prognosis [45,47,59,60], with those achieving pCR having an increased recurrence free survival of 20% versus those with residual disease [47]. Although the objective of the current analysis was not to quantify pCR as a surrogate of enhanced survival, comparisons in pCR within histological subtype and survival poses questions of interest to the oncologist, particularly when data from the current analysis illustrates a 3-fold discrepancy in expected pCR rates (7.4% for ILC vs. 22.1% for IDC). This data suggests achieving pCR to be an unlikely outcome in ILC following NACT. Given the strong hormone receptor expression in ILC, these patients may be better served with neoadjuvant endocrine therapy in an attempt to achieve tumour downstaging [61], while sparing the toxicities associated with NACT [62].

In patients with axillary involvement, axillary pCR has been demonstrated in previous analyses to be a more accurate prognostic biomarker than breast pCR [39,56,60,[63], [64], [65]]. For patients with node positive disease, our analysis illustrates patients with IDC are twice as likely to achieve axillary pCR than their ILC counterparts which may facilitate less invasive axillary surgery consequently. Nevertheless, there is significant evidence that patients with ILC and nodal involvement are more likely to achieve axillary pCR than overall pCR (ILC rate of axillary pCR – 22.3%, ILC overall pCR rate – 7.4%) This may indicate that the attainment of pCR in the axilla alone is more achievable due to a relatively lower burden of disease in this location [66], but may also indicate an important molecular distinction between the primary tumour and the axillary metastasis.

When considering pCR of the breast or axilla, breast cancer histological subtype should not be taken in isolation. ILC have the overwhelming tendency to express strong estrogen receptor positivity and assume the luminal A breast cancer (LABC) molecular subtype (90–95% of ILC cases). In contrast, only 50% of ductal cancers manifest the LABC phenotype [[67], [68], [69], [70]]. LABC is considered classically to be chemoresistant disease [[71], [72], [73]], indicating cancer molecular subtyping must be assessed for included patients. Six studies provided details of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PgR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) status among both cohorts: IDC were associated with triple negative and HER2 enriched molecular subtypes, while luminal disease was associated with ILC [25,29,31,40,42,47]. This data implicates molecular subtyping as a confounding factor in analyses comparing the respective responses of ILC and IDC, which must be considered before attributing oncological and surgical outcomes, such as pCR and BCS rates, to histological subtyping alone. Therefore, when determining the ‘true’ impact of histological subtype on pCR, future translational research must focus on matching ILC and IDC cases based on ER, PgR and HER2 status, mitigating molecular subtyping as a confounder. Furthermore, clinicopathological data which contribute to NACT response, such as tumour grade [74] and Ki-67 proliferation indices [75,76] must be considered in order to truly appraise the variability in outcomes between ILC and IDC.

The current analysis of post-NACT BCS comparing ILC and IDC is the largest performed in medico-oncological literature, and includes data on an additional 4495 patients not available to previous authors [15]. Findings in this study are consistent with the previous analysis, with BCS rates following NACT twice as likely in patients with IDC versus those with ILC. However we must acknowledge further confounding data; results from 7 included studies provided data in relation to tumour staging, with 52.0% of ILCs being T3/4 versus 36.0% of IDCs [21,29,31,40,44,52,56]. In reiteration of our recommendations in relation to pCR and immunohistochemical data, more selective matching of clinicopathological features of ILC and IDC cases is warranted in future to yield more meaningful results. While ILC disease tend to be large cancers requiring mastectomy [66] reliance upon NACT to facilitate BCS serves as a poorer strategy of tumour downstaging compared to in IDC disease. The relative failure of the NACT to achieve BCS in ILC is demonstrated in our findings illustrating that margin positivity rates were significantly higher in ILC post NACT than in IDC. This finding is confounded by the higher prevalence of large tumour size as outlined above. In considering the clinical significance of these findings however, it should be noted that with the use of radiotherapy, the decision to treat a patient with BCS or mastectomy result in similar breast cancer specific survival as outlined by Fodor et al. [77].

Traditionally, NACT was indicated in the setting of locally-advanced stage IIB/III disease, or in patients where a tumour size reduction would improve surgical resectability [6]. In the molecular era, clinical indications for NACT have expanded, such that neoadjuvant strategies are considered in early-stage and operable disease [78,79]. There has been a reported increase in NACT prescription in early breast cancer between 2008 and 2017 (20% vs. 57.7%) [80] and the increased use occurs across all molecular subtypes [81]. While these expansion of indications for NACT may imply progressive practice in the setting of breast carcinoma, clinicians should proceed with caution within the context of ILC disease – the current analysis suggests these patients are not as well served with NACT as global perceptions may believe. The same is also true of the prescription of adjuvant chemotherapy for ILC patients, which has been expertly outlined in a recent meta-analysis by Trapani et al. where a large proportion of patients being treated for ILC experienced poorer outcomes after chemotherapy administration when compared to other histopathological breast cancer subtypes [82]. The authors highlight that ILC should be considered distinct clinical entity to other breast epithelial cancers, such as IDC, possessing several unique oncological and surgical implications when included indistinctly in conventional breast cancer management. The solution for the ILC cohort, which have a strong tendency towards hormone positivity, may be a more widespread use of Neoadjuvant Endocrine Therapy (NET); in their review, Sella et al. reported that NET prescription is underutilised despite its capabilities of achieving tumour downstaging in select cases, indicating that NET may have a more conventional use in prospective HR + breast cancer management [83,84]. Similarly, Davey et al. illustrated the efficacy of NET following low-risk substratification using the 21-gene recurrence score expression assay in the setting of locally advanced estrogen receptor positive breast cancers in their recent meta-analysis [84]. Similar to the results of the current study, these previous authors highlight the value of NET as a modern management strategy of HR + breast cancers, particularly in the setting of double hormone positive (ER+/PR+) lobular disease as has been previously outlined in cases of low-risk disease [85].

In conclusion, as current thresholds for prescribing cytotoxic chemotherapy become lowered even further, histological breast cancer subtype must become incorporated into the paradigm for breast cancer therapeutic decision making, and given similar consideration to other parameters such as molecular subtype, tumour staging and nodal status. The current analysis suggests ILC histology are less likely to derive oncological or surgical benefit from NACT prescription when compared to their counterparts with ductal morphology. In the era of precision medicine, multidisciplinary therapeutic decision making should incorporate these findings into clinical practice to further personalise oncological breast cancer patient care.

Funding

DJO’C and MGD received funding from National Breast Cancer Research Institute, Ireland.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2021.11.017.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.The world health organization histological typing of breast tumors--second edition. The world organization. Am J Clin Pathol. 1982 -12;78(6):806–816. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/78.6.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li C.I., Anderson B.O., Daling J.R., Moe R.E. Trends in incidence rates of invasive lobular and ductal breast carcinoma. J Am Med Assoc. 2003 -03-19;289(11):1421–1424. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.11.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dossus L., Benusiglio P.R. Lobular breast cancer: incidence and genetic and non-genetic risk factors. Breast Cancer Res. 2015 -03-13;17:37. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0546-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cancer Today - estimated number of new cases in. 2020. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/online-analysis-table?v=2020&mode=cancer&mode_population=continents&population=900&populations=900&key=asr&sex=0&cancer=39&type=0&statistic=5&prevalence=0&population_group=0&ages_group%5B%5D=0&ages_group%5B%5D=17&group_cancer=1&include_nmsc=1&include_nmsc_other=1 worldwide, both sexes, all ages [Internet]. [cited Jan 26, 2021]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Z., Yang J., Li S., Lv M., Shen Y., Wang B., et al. Invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast: a special histological type compared with invasive ductal carcinoma. PLoS One. 2017;12(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schott A.F., Hayes D.F. Defining the benefits of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Orthod. 2012 April 16;30(15):1747–1749. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.3161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmes D., Colfry A., Czerniecki B., Dickson-Witmer D., Francisco Espinel C., Feldman E., et al. Performance and practice guideline for the use of neoadjuvant systemic therapy in the management of breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015 -10;22(10):3184–3190. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4753-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute for Care and Health Excellence . 2018 July 18. Early and locally advanced breast cancer: diagnosis and management NICE guideline [NG101] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Testa U., Castelli G., Pelosi E. Breast cancer: a molecularly heterogenous disease needing subtype-specific treatments. Med Sci. 2020 -03-23;8(1) doi: 10.3390/medsci8010018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shenoy H.G., Peter M.B., Masannat Y.A., Dall B.J.G., Dodwell D., Horgan K. Practical advice on clinical decision making during neoadjuvant chemotherapy for primary breast cancer. Surg Oncol. 2009 -03;18(1):65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Özkurt E., Sakai T., Wong S.M., Tukenmez M., Golshan M. Survival outcomes for patients with clinical complete response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: is omitting surgery an option? Ann Surg Oncol. 2019 -10;26(10):3260–3268. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-07534-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Killelea B.K., Yang V.Q., Wang S., Hayse B., Mougalian S., Horowitz N.R., et al. Racial differences in the use and outcome of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: results from the national cancer data base. J Clin Oncol. 2015 -12-20;33(36):4267–4276. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.7801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christgen M., Steinemann D., Kühnle E., Länger F., Gluz O., Harbeck N., et al. Lobular breast cancer: clinical, molecular and morphological characteristics. Pathol Res Pract. 2016 -07;212(7):583–597. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devane L.A., Baban C.K., O'Doherty A., Quinn C., McDermott E.W., Prichard R.S. The impact of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on margin Re-excision in breast-conserving surgery. World J Surg. 2020 -05;44(5):1547–1551. doi: 10.1007/s00268-020-05383-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petrelli F., Barni S. Response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in ductal compared to lobular carcinoma of the breast: a meta-analysis of published trials including 1,764 lobular breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013 -11;142(2):227–235. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2751-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009 -07-21;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stroup D.F., Berlin J.A., Morton S.C., Olkin I., Williamson G.D., Rennie D., et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. J Am Med Assoc. 2000 -04-19;283(15):2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wells GA Shea, B O'Connell D Peterson, Welch J., Losos V., M Tugwell P. 2019. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alamgeer M., Ganju V., Kumar B., Fox J., Hart S., White M., et al. Changes in aldehyde dehydrogenase-1 expression during neoadjuvant chemotherapy predict outcome in locally advanced breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2014 -04-24;16(2):R44. doi: 10.1186/bcr3648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boidot R., Vegran F., Soubeyrand M., Fumoleau P., Coudert B., Lizard-Nacol S. Variations in gene expression and response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast carcinoma. Cancer Invest. 2009 -06;27(5):521–528. doi: 10.1080/07357900802298096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bollet M.A., Savignoni A., Pierga J.-, Lae M., Fourchotte V., Kirova Y.M., et al. High rates of breast conservation for large ductal and lobular invasive carcinomas combining multimodality strategies. Br J Cancer. 2008 -02-26;98(4):734–741. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boughey J.C., Wagner J., Garrett B.J., Harker L., Middleton L.P., Babiera G.V., et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in invasive lobular carcinoma may not improve rates of breast conservation. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009 -06;16(6):1606–1611. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0402-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan A., Willsher P.C., Hastrich D.J., Anderson J., Barham T., Latham B., et al. Preoperative taxane-based chemotherapy in a standardized protocol for locally advanced breast cancer. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2012 -03;8(1):62–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-7563.2011.01489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho J.H., Park J.M., Park H.S., Park S., Kim S.I., Park B. Oncologic safety of breast-conserving surgery compared to mastectomy in patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced breast cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2013 -12;108(8):531–536. doi: 10.1002/jso.23439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cocquyt V.F., Blondeel P.N., Depypere H.T., Praet M.M., Schelfhout V.R., Silva O.E., et al. Different responses to preoperative chemotherapy for invasive lobular and invasive ductal breast carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2003 -05;29(4):361–367. doi: 10.1053/ejso.2002.1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cristofanilli M., Gonzalez-Angulo A., Sneige N., Kau S., Broglio K., Theriault R.L., et al. Invasive lobular carcinoma classic type: response to primary chemotherapy and survival outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2005 -01-01;23(1):41–48. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dave R.V., Millican-Slater R., Dodwell D., Horgan K., Sharma N. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with MRI monitoring for breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2017 -08;104(9):1177–1187. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Los Santos, Jennifer F., Cantor A., Amos K.D., Forero A., Golshan M., Horton J.K., et al. Magnetic resonance imaging as a predictor of pathologic response in patients treated with neoadjuvant systemic treatment for operable breast cancer. Translational Breast Cancer Research Consortium trial 017. Cancer. 2013 -05-15;119(10):1776–1783. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delpech Y., Coutant C., Hsu L., Barranger E., Iwamoto T., Barcenas C.H., et al. Clinical benefit from neoadjuvant chemotherapy in oestrogen receptor-positive invasive ductal and lobular carcinomas. Br J Cancer. 2013 -02-05;108(2):285–291. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fisher C.S., Ma C.X., Gillanders W.E., Aft R.L., Eberlein T.J., Gao F., et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is associated with improved survival compared with adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with triple-negative breast cancer only after complete pathologic response. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012 -01;19(1):253–258. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1877-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fitzal F., Mittlboeck M., Steger G., Bartsch R., Rudas M., Dubsky P., et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy increases the rate of breast conservation in lobular-type breast cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012 -02;19(2):519–526. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1879-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gahlaut R., Bennett A., Fatayer H., Dall B.J., Sharma N., Velikova G., et al. Effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on breast cancer phenotype, ER/PR and HER2 expression - implications for the practising oncologist. Eur J Cancer. 2016 -06;60:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gentile L.F., Plitas G., Zabor E.C., Stempel M., Morrow M., Barrio A.V. Tumor biology predicts pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients presenting with locally advanced breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017 -12;24(13):3896–3902. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-6085-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldstein N.S., Decker D., Severson D., Schell S., Vicini F., Margolis J., et al. Molecular classification system identifies invasive breast carcinoma patients who are most likely and those who are least likely to achieve a complete pathologic response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer. 2007 -10-15;110(8):1687–1696. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Groheux D., Martineau A., Teixeira L., Espié M., de Cremoux P., Bertheau P., et al. 18FDG-PET/CT for predicting the outcome in ER+/HER2- breast cancer patients: comparison of clinicopathological parameters and PET image-derived indices including tumor texture analysis. Breast Cancer Res. 2017 -01-05;19(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s13058-016-0793-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grover S., Grover S., Badiyan S., Badiyan S., Trifiletti D., Trifiletti D., et al. Regional nodal irradiation following pathologic complete response in the axilla to neoadjuvant chemotherapy: patterns of treatment. J Radiat Oncol. 2017 Mar;6(1):81–92. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gusic L.H., Walsh K., Flippo-Morton T., Sarantou T., Boselli D., White R.L. Rationale for mastectomy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Am Surg. 2018 -01-01;84(1):126–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keskin S., Muslumanoglu M., Saip P., Karanlık H., Guveli M., Pehlivan E., et al. Clinical and pathological features of breast cancer associated with the pathological complete response to anthracycline-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Oncology. 2011;81(1):30–38. doi: 10.1159/000330766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lips E.H., Mulder L., de Ronde J.J., Mandjes IaM., Vincent A., Vrancken Peeters M.T.F.D., et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in ER+ HER2- breast cancer: response prediction based on immunohistochemical and molecular characteristics. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012 -02;131(3):827–836. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1488-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lips E.H., Mukhtar R.A., Yau C., de Ronde J.J., Livasy C., Carey L.A., et al. Lobular histology and response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012 -11;136(1):35–43. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2233-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Loibl S., von Minckwitz G., Raab G., Blohmer J., Dan Costa S., Gerber B., et al. Surgical procedures after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in operable breast cancer: results of the GEPARDUO trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006 -11;13(11):1434–1442. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mathieu M.-, Rouzier R., Llombart-Cussac A., Sideris L., Koscielny S., Travagli J.P., et al. The poor responsiveness of infiltrating lobular breast carcinomas to neoadjuvant chemotherapy can be explained by their biological profile. Eur J Cancer. 2004 -02;40(3):342–351. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2003.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nagao T., Kinoshita T., Hojo T., Tsuda H., Tamura K., Fujiwara Y. The differences in the histological types of breast cancer and the response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy: the relationship between the outcome and the clinicopathological characteristics. Breast. 2012 -06;21(3):289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petruolo O.A., Pilewskie M., Patil S., Barrio A.V., Stempel M., Wen H.Y., et al. Standard pathologic features can Be used to identify a subset of estrogen receptor-positive, HER2 negative patients likely to benefit from neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017 -09;24(9):2556–2562. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-5898-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pu R.T., Schott A.F., Sturtz D.E., Griffith K.A., Kleer C.G. Pathologic features of breast cancer associated with complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy: importance of tumor necrosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005 -03;29(3):354–358. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000152138.89395.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reitsamer R., Peintinger F., Prokop E., Hitzl W. Pathological complete response rates comparing 3 versus 6 cycles of epidoxorubicin and docetaxel in the neoadjuvant setting of patients with stage II and III breast cancer. Anti Cancer Drugs. 2005 -09;16(8):867–870. doi: 10.1097/01.cad.0000173475.59616.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Riba L.A., Russell T., Alapati A., Davis R.B., James T.A. Characterizing response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in invasive lobular breast carcinoma. J Surg Res. 2019 -01;233:436–443. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2018.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rouzier R., Mathieu M., Sideris L., Youmsi E., Rajan R., Garbay J., et al. Breast-conserving surgery after neoadjuvant anthracycline-based chemotherapy for large breast tumors. Cancer. 2004 -09-01;101(5):918–925. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sinn H.P., Schmid H., Junkermann H., Huober J., Leppien G., Kaufmann M., et al. [Histologic regression of breast cancer after primary (neoadjuvant) chemotherapy] Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 1994 -10;54(10):552–558. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1022338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Straver M.E., Rutgers E.J.T., Rodenhuis S., Linn S.C., Loo C.E., Wesseling J., et al. The relevance of breast cancer subtypes in the outcome of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010 -09;17(9):2411–2418. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1008-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sullivan P.S., Apple S.K. Should histologic type be taken into account when considering neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast carcinoma? Breast J. 2009 Mar-Apr;15(2):146–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2009.00689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tubiana-Hulin M., Stevens D., Lasry S., Guinebretière J.M., Bouita L., Cohen-Solal C., et al. Response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in lobular and ductal breast carcinomas: a retrospective study on 860 patients from one institution. Ann Oncol. 2006 -08;17(8):1228–1233. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Untch M., Fasching P.A., Konecny G.E., Hasmüller S., Lebeau A., Kreienberg R., et al. Pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus trastuzumab predicts favorable survival in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-overexpressing breast cancer: results from the TECHNO trial of the AGO and GBG study groups. J Clin Oncol. 2011 -09-01;29(25):3351–3357. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.4930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Volders J.H., Haloua M.H., Krekel N.M.A., Negenborn V.L., Barbé E., Sietses C., et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast-conserving surgery - consequences on margin status and excision volumes: a nationwide pathology study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016 -07;42(7):986–993. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.02.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vugts G., Van den Heuvel F., Maaskant-Braat A.J.G., Voogd A.C., Van Warmerdam, Laurence J.C., Nieuwenhuijzen G.A.P., et al. Predicting breast and axillary response after neoadjuvant treatment for breast cancer: the role of histology vs receptor status. Breast J. 2018 -11;24(6):894–901. doi: 10.1111/tbj.13085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wenzel C., Bartsch R., Hussian D., Pluschnig U., Altorjai G., Zielinski C.C., et al. Invasive ductal carcinoma and invasive lobular carcinoma of breast differ in response following neoadjuvant therapy with epidoxorubicin and docetaxel + G-CSF. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007 -07;104(1):109–114. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9397-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yamazaki N., Wada N., Yamauchi C., Yoneyama K. High expression of post-treatment Ki-67 status is a risk factor for locoregional recurrence following breast-conserving surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015 -05;41(5):617–624. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zeidman M., Alberty-Oller J.J., Ru M., Pisapati K.V., Moshier E., Ahn S., et al. Use of neoadjuvant versus adjuvant chemotherapy for hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: a National Cancer Database (NCDB) study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020 -11;184(1):203–212. doi: 10.1007/s10549-020-05809-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fisher B., Bryant J., Wolmark N., Mamounas E., Brown A., Fisher E.R., et al. Effect of preoperative chemotherapy on the outcome of women with operable breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998 -08;16(8):2672–2685. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.8.2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cortazar P., Zhang L., Untch M., Mehta K., Costantino J.P., Wolmark N., et al. Pathological complete response and long-term clinical benefit in breast cancer: the CTNeoBC pooled analysis. Lancet. 2014 -07-12;384(9938):164–172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62422-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thornton M.J., Williamson H.V., Westbrook K.E., Greenup R.A., Plichta J.K., Rosenberger L.H., et al. Neoadjuvant endocrine therapy versus neoadjuvant chemotherapy in node-positive invasive lobular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019 -10;26(10):3166–3177. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-07564-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Azim H.A., de Azambuja E., Colozza M., Bines J., Piccart M.J. Long-term toxic effects of adjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2011 -09;22(9):1939–1947. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rouzier R., Extra J., Klijanienko J., Falcou M., Asselain B., Vincent-Salomon A., et al. Incidence and prognostic significance of complete axillary downstaging after primary chemotherapy in breast cancer patients with T1 to T3 tumors and cytologically proven axillary metastatic lymph nodes. J Clin Oncol. 2002 -03-01;20(5):1304–1310. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.5.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hennessy B.T., Hortobagyi G.N., Rouzier R., Kuerer H., Sneige N., Buzdar A.U., et al. Outcome after pathologic complete eradication of cytologically proven breast cancer axillary node metastases following primary chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005 -12-20;23(36):9304–9311. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.5023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kantor O., Sipsy L.M., Yao K., James T.A. A predictive model for axillary node pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018 -05;25(5):1304–1311. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6345-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Arpino G., Bardou V.J., Clark G.M., Elledge R.M. Infiltrating lobular carcinoma of the breast: tumor characteristics and clinical outcome. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6(3):149. doi: 10.1186/bcr767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Braunstein L.Z., Brock J.E., Chen Y., Truong L., Russo A.L., Arvold N.D., et al. Invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast: local recurrence after breast-conserving therapy by subtype approximation and surgical margin. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015 -01;149(2):555–564. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3273-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reed A.E.M., Kutasovic J.R., Lakhani S.R., Simpson P.T. Invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast: morphology, biomarkers and ’omics. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17(1) doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0519-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jung S., Jeong J., Shin S., Kwon Y., Kim E., Ko K.L., et al. The invasive lobular carcinoma as a prototype luminal A breast cancer: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2010 -12-03;10:664. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Orvieto E., Maiorano E., Bottiglieri L., Maisonneuve P., Rotmensz N., Galimberti V., et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics of invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast: results of an analysis of 530 cases from a single institution. Cancer. 2008 -10-01;113(7):1511–1520. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Collins P.M., Brennan M.J., Elliott J.A., Abd Elwahab S., Barry K., Sweeney K., et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for luminal a breast cancer: factors predictive of histopathologic response and oncologic outcome. Am J Surg. 2020 December 9 doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim H.S., Yoo T.K., Park W.C., Chae B.J. Potential benefits of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in clinically node-positive luminal Subtype− breast cancer. J Breast Cancer. 2019;22(3):412–424. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2019.22.e35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Davey M.G., Ryan É.J., McAnena P.F., Boland M.R., Barry M.K., Sweeney K.J., et al. Disease recurrence and oncological outcome of patients treated surgically with curative intent for estrogen receptor positive, lymph node negative breast cancer. Surg Oncol. 2021 -01-31;37:101531. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2021.101531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kurozumi S., Inoue K., Takei H., Matsumoto H., Kurosumi M., Horiguchi J., , PgR Ki67, p27(Kip1), and histological grade as predictors of pathological complete response in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy using taxanes followed by fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide concomitant with trastuzumab. BMC Cancer. 2015 -09-07;15:622. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1641-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Alba E., Lluch A., Ribelles N., Anton-Torres A., Sanchez-Rovira P., Albanell J., et al. High proliferation predicts pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in early breast cancer. Oncol. 2016 -02;21(2):150–155. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sueta A., Yamamoto Y., Hayashi M., Yamamoto S., Inao T., Ibusuki M., et al. Clinical significance of pretherapeutic Ki67 as a predictive parameter for response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer: is it equally useful across tumor subtypes? Surgery. 2014 -05;155(5):927–935. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fodor J., Major T., Tóth J., Sulyok Z., Polgár C. Comparison of mastectomy with breast-conserving surgery in invasive lobular carcinoma: 15-Year results. Rep Practical Oncol Radiother. 2011;16(6):227–231. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Senkus E., Kyriakides S., Ohno S., Penault-Llorca F., Poortmans P., Rutgers E., et al. Primary breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2015 -09;26(Suppl 5):8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Thill M., Liedtke C. AGO recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with advanced and metastatic breast cancer: update 2016. Breast Care. 2016 -6;11(3):216–222. doi: 10.1159/000447030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Riedel F., Hoffmann A.S., Moderow M., Heublein S., Deutsch T.M., Golatta M., et al. Time trends of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for early breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2020 -12-01;147(11):3049–3058. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hennigs A., Riedel F., Marmé F., Sinn P., Lindel K., Gondos A., et al. Changes in chemotherapy usage and outcome of early breast cancer patients in the last decade. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016 -12;160(3):491–499. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-4016-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Trapani D., Gandini S., Corti C., Crimini E., Bellerba F., Minchella I., et al. Benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with lobular breast cancer: a systematic review of the literature and metanalysis. Cancer Treat Rev. 2021;97:102205. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2021.102205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sella T., Weiss A., Mittendorf E.A., King T.A., Pilewskie M., Giuliano A.E., et al. Neoadjuvant endocrine therapy in clinical practice: a review. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(11):1700–1708. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Davey M.G., Ryan É J., Boland M.R., Barry M.K., Lowery A.J., Kerin M.J. Clinical utility of the 21-gene assay in predicting response to neoadjuvant endocrine therapy in breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast. 2021;58:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2021.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Davey M.G., Ryan É J., Abd Elwahab S., Elliott J.A., McAnena P.F., Sweeney K.J., et al. Clinicopathological correlates, oncological impact, and validation of oncotype DX™ in a European tertiary referral centre. Breast J. 2021;27(6):521–528. doi: 10.1111/tbj.14217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.