Abstract

Objective

In recent years, the gap between research into family therapy and clinical practice in the field has been growing larger. In the Italian context, a major issue concerns the lack of any single instrument that can be used to assess a range of different family functions. In order to fill this research gap, the present paper aims to validate the Italian version of the “Cuestionario de Evaluación de las Relaciones Familiares Básicas” (CERFB), a questionnaire that evaluates family relations by measuring conjugal and parenting functions. This validation will be carried out by testing the instrument’s factorial structure, reliability and construct validity using an Italian non-clinical sample.

Method

For this study, 114 couples as family units (228 participants) were recruited from the general population (mean age: 51.70, SD: 6.04). The 25-item CERFB, the six Domains of FACES IV, the FCS and the FSS were administered.

Results

Results from confirmatory factor analysis supported the original two-factor structure regarding conjugal and parenting functions. Furthermore, results supported excellent internal consistency and construct validity with conceptually related family measures. Finally, normative scores were calculated in order to explain clinical results.

Conclusions

The Italian version of the CERFB shows good psychometric properties and can be considered a valid and reliable measure for assessing both conjugal and parenting functions. It can be used in research and for clinical purposes as an innovative instrument applied to prevent risks to the health of children and to carry out and evaluate family interventions.

Keywords: family relations, prevention, psychometrics, assessment, health family

Introduction

Conjugal and parenting functions have long been the focus of widespread study in the field of family therapy and assessment, beginning with the earliest groundbreaking work that approached this field from a systemic perspective. In Europe, Italy was among the earliest adopters of this systemic model, and the model is still in frequent use there today (Linares 2012). As the field of family therapy has developed, many have pointed to a corresponding widening of the gap between research and practice, a disparity that has persisted despite the a consensus as to the need to unify the field (Sprenkle and Piercy 2005). One possible strategy would be to create a questionnaire and inventory that is useful in both clinical and research practice. To this end, Baiocco et al. (2012) have highlighted the importance of instruments with documented reliability and validity in family assessment in order to help prevent health risks.

Some instruments are already in use in the Italian context to assess general family functioning or specific family functions. For instance, the Italian version of the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scale (FACES IV; Olson 2011), validated by Baiocco et al. (2012), provides a general evaluation of family functioning through six independent dimensions. FACES IV consists of 42 items and, in the original version, is divided into six scales. Two balanced scales, Cohesion and Flexibility, assess central-moderate areas, while four unbalanced scales, Enmeshed, Disengaged, Chaotic and Rigid, assess the lower and the upper ends of Cohesion and Flexibility. The results of an exploratory factor analysis of the Italian version suggested a model with five factors, in contrast with the original six-factor version, because the items for Cohesion and Flexibility loaded in a single factor. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the dimensions ranged from 0.63 to 0.73. Finally, no confirmatory factor analysis was performed in order to support the results of the exploratory factorial analysis. For the purposes of assessing conjugal function only, the Italian

adaptation by Gentili et al. (2002) of the Dyadic Adjuntament Scale (DAS; Spanier 1976) is sometimes used. The DAS consists of 32 items and measures conjugal adjustment through four subscales: dyadic satisfaction, dyadic cohesion, dyadic consensus and affectional expression. The results of the exploratory factor analysis of the Italian version of DAS showed the same four factors as in the original version. Cronbach’s alpha for the general factor was .93, indicating good reliability. The vast majority of existing Italian instruments are designed to evaluate parenting practices in the immediate environment, focusing either on parents’ educational style or on parenting functions (Bessi et al. 2009). For example, the Italian version of the Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI; Scinto et al. 1999) consists of 25 items and measures parental style as reported by the children, using two factors (care and protection). Although the Italian version of the PBI showed the same factorial structure as the original and displayed a good degree of reliability, it was tested only for its ability to assess children’s perceptions of their parents’ parental style. As such, it cannot measure how the members of the couple experience their own parental roles. There is also an abbreviated version of the Parenting Stress Index (PSI; Guarino et al. 2008), consisting of 36 items and measuring the level of parenting stress in the parent/child relationship through three subscales: parental distress, parent-child dysfunctional interaction, and difficult child. Although the shortened Italian version of the PSI showed the same factorial structure as the original and a good degree of reliability, the underlying theoretical model is mainly focused on difficulties faced by parents in performing their parental roles. Finally, the Parent-Adolescent Communication Scale (PACS; Lanz 1997) consists of 20 items and measures the quality of communication between parents and children.

From this brief description, it is clear that, although all the Italian versions of these instruments were based on solid theoretical models, they face some limitations in their practical application. Some of these limitations have to do with methodological reasons (for example for FACES IV, confirmatory factorial analysis is missing), while others are connected to the fact that the instruments measure only certain family functions (for example, PACS only measures the communication, and PSI measures only parental style). This means that more than a single scale has to be administered in order to simultaneously measure both conjugal and parenting functions, and consequently that participants in clinical or research assessments in the field are forced to respond to a larger number of items. Furthermore, as described, different scales are founded on different theoretical models. Therefore, there is a need for an Italian validation of a questionnaire that is based on a solid theory and is able to concurrently measure a range of basic family relations, i.e. conjugal and parenting functions.

Recently, Ibáñez et al. (2012) created the Cuestionario de Evaluación de las Relaciones Familiares Básicas (CERFB), which is the first theoretically developed, built and adapted measure to evaluate the family by examining both conjugal and parenting functions, based on Linares’s basic family relations theory (1996, 2012). Linares (2002) contends that in contemporary families gender is no longer a determining factor in the structure of couples, nor is the presence of biological or adopted children or offspring conceived through artificial fertilization techniques. The central role is played by the existence of two functions: Conjugal and parenting. Conjugal functions refer to the relationship between the partners forming a couple, while parenting functions refer to the relationship between both parents and their children. Linares (2002) believes them to be two independent functions with bipolar dimensions: Conjugal functions range from harmony to disharmony and parenting functions from their primary preservation to deterioration. However, they converge at the family’s capacity for relational nurturing, a determining factor in the development of the child’s personality and mental health (Linares, 1996, 2006, 2007, 2012). The combination of the two functions when preserved gives rise to the optimal conditions for the generation of fully satisfactory relational nurturing, but when one or both of the functions is deteriorated it can result in the creation on any of three dysfunctional relational modalities, all which are related to psychopathology.

The original version of the CERFB consists of 25 items. The original validation study was carried out on a non-clinical Spanish sample made up of 442 participants (221 couples as family units). In accordance with Linares’ theory, the exploratory factorial analysis, through principal component analysis, resulted in two factors: the conjugal factor, which refers to how the members of the parenting couple interact with each other, and the parenting factor, which represents how the parents treat their children. Both scales in the original Spanish version achieved good reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha figures of over .90 for both the conjugal and parenting factors. Therefore, the CERFB may be considered a good questionnaire that simultaneously assesses conjugal and parenting functions and distinguishes between couples with harmonic and disharmonic relationships and between the competent and inadequate exercise of parenting functions (Ibáñez et al. 2012).

The aim of the present study, then, was to develop an Italian version of the CERFB by translating and cross-culturally adapting the original version. Additionally, the aim was to replicate the original two-factor structure of the CERFB for the Italian version through confirmatory factorial analyses. Finally, the present study sought to investigate the CERFB’s reliability indices and examine convergent validity with other family instruments and to provide normative data.

Method

Procedure

In line with the suggestions of the American Educational Research Association, the American Psychological Association and National Council on Measurement in Education (2014) as to the to provide empirical evidence of the psychometric properties of an instrument in the specific population in which it is to be used, the present study aimed to validate an Italian version of the CERFB. This study takes the view that the development of an instrument is an ongoing process: a new translation and adaptation needs to be empirically tested in order to justify its application (Gudmundsson 2009).

The Italian version of the CERFB was developed following the International Test Commission’s (ITC) guidelines (Byrne 2016) involving forward and back translation procedures, as originally described by Brislin (1970). The work was done with the original authors’ consent and collaboration.

Firstly, the CERFB was independently translated on an item-by-item basis from Spanish into Italian by two bilingual science experts (a family psychotherapist and a methodology expert) in the field of Psychology. Simultaneously, each individual item was adapted, taking into account the role of each as part of the groups of items intended to measure each of the CERFB’s dimensions. The two initial versions of the translation were reviewed and the differences between them discussed in order to arrive at a unanimously accepted version. Secondly, a further round of review of this Italian version was carried out by five native Italian professionals from the psychological and psychiatric sectors, all of whom had systemic family training. They first worked individually through a semi-structured questionnaire to consider the clarity and cultural meaning of the items, and they then discussed their comments together in order to resolve any inconsistencies. Thirdly, the final Italian version was back translated into Spanish by bilingual science experts different from those who had done the translations in the first phase. Finally, the accordance between the original Spanish version of the CERFB and the back-translation version was tested. At this point, a pilot study was conducted to assess the appropriateness of the translated instrument. This pilot questionnaire was presented to 64 Italian participants (32 couples as family units) as a semi-structured questionnaire; this group was asked to answer to questionnaire and to indicate the degree of clarity of each item, using a scale from 1 (completely unclear) to 5 (completely clear). With respect to clarity, the items achieved a mean score between 4.35 and 5, suggesting that no modifications were necessary.

The final Italian version of the CERFB was included in the questionnaire packet. Participation in the study was voluntary and no incentive was offered. The study protocol complied fully with the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (American Psychological Association 2010), and it was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ramon Llull University in Barcelona. Written informed consent was requested after a complete description of the study had been provided to each participant.

Participants

The final sample consisted of 228 participants equally divided by gender (114 couples as family units), aged between 34 and 69 years (M = 51.70, SD = 6.04). Of the 114 couples, 25.8% had just one child, 57.8% had a second child, 14.2% had a third child and 2.2% had a fourth child. The average cohabitation time was 24.04 years (SD = 5.88). In relation to Conjugal status, 96.1% of the couples were married for the first time, 2.6% for the second time and 1.3% were cohabitant partners. Regarding education, 33.20% of the partners had a university degree, 47.10% had a high school degree and the remaining 19.70% had only completed compulsory schooling.

Measures

Cuestionario de Evaluación de las Relaciones Familiares Básicas (CERFB; Ibáñez et al. 2012). This 25-item self-report scale investigates family relations. Items are answered on a 5-point Likert scale of increasing frequency, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The instrument consists of two scales: Conjugal functions (14 items) and Parenting functions (11 items). The Conjugal score ranges from 0 to 70, and the Parenting score from 0 to 55. Higher scores are indicative of greater functionality. Both scales in the original Spanish version in the general population have shown high degrees of reliability: Conjugal function (Cronbach’s alpha = .92) and Parenting function (Cronbach’s alpha = .91).

Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scale (FACES IV; Olson 2011). FACES IV is a self-reported measure of family functioning. It is composed of 42 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale, which ranges from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). It consists of six scales (two balanced and four unbalanced) that measure two dimensions: Cohesion and Flexibility. The balanced scales are Balanced Cohesion and Balanced Flexibility, which assess central-moderate levels. The unbalanced scales are Enmeshed and Disengaged, which assess the high and low extremes of Cohesion, and Rigid and Chaotic, which assess the high and low extremes of Flexibility. Higher scores for the balanced scales and lower scores for the unbalanced scales are indicative of greater functionality. The Italian validation showed an internal consistency of its scales through Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from .63 to .73 (Baiocco et al. 2012).

Family Communication Scale (FCS; Olson and Gorall 2006) assesses communication in families. FCS is made up of 10 items, rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). It is a one-dimensional measure with higher scores being indicative of greater functionality. It has shown good reliability in previous Italian studies (Cronbach’s alpha = .84; Baiocco et al. 2012).

Family Satisfaction Scale (FSS; Olson 1995). The FSS assesses family members’ degree of satisfaction with their family functioning in terms of family cohesion and flexibility. Its 10 items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly unsatisfied) to 5 (strongly satisfied). It is a one-dimensional measure, with higher scores being indicative of greater functionality. It has shown good reliability in previous Italian studies (Cronbach’s alpha = .90; Baiocco et al. 2012).

Results

Preliminary analysis

Firstly, an item analysis was performed in order to investigate the items’ psychometric properties. Item analysis makes it possible to the characteristics (mean, standard deviation, skewness and kurtosis) of each item and to eliminate nondiscriminant items, i.e. those items that show extreme means and nearly zero standard deviation those with skewness and kurtosis higher than |2| (Barbaranelli, 2007).

Results of item analysis (descriptive statistics) are shown in table 1 (see the next page).

Table 1.

Item descriptive statistics, item analyses (n = 228)

| CERFB | M | SD | SK | KU |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I am sure that my children only think about what they want | 2.58 | 1.07 | .34 | -.28 |

| (Sono sicuro che i miei figli pensano solo ai loro vantaggi) | ||||

| I think that my children have serious defects | 2.37 | .77 | .15 | -.30 |

| (Ritengo che il/i mio/miei figlio/i hanno molti difetti) | ||||

| My partner helps me face everyday problems | 3.78 | 1.13 | -.72 | -.33 |

| (Mio marito/mia moglie mi aiuta ad affrontare i problemi quotidiani) | ||||

| I think that my children are not responsible | 2.22 | 1.03 | .58 | -.31 |

| (Credo che il/i mio/miei figlio/i non hanno il senso della responsabilità) | ||||

| I don’t feel that my children return my affection | 1.75 | 1.06 | 1.61 | 1.05 |

| (Non mi sento corrisposto da mio/miei figlio/i dal punto di vista affettivo) | ||||

| I think my partner does not understand me | 2.33 | 1.08 | .47 | -.41 |

| (Credo che mio marito/mia moglie non mi comprende) | ||||

| My partner spoils things by being indiscreet | 1.95 | 1.05 | 1.11 | .71 |

| (Mio marito/mia moglie rovina tutto con la sua indelicatezza) | ||||

| I can talk calmly with my children | 3.94 | 1.04 | -.85 | .08 |

| (Dialogo tranquillamente con il/i mio/miei figlio/i) | ||||

| My partner listens to other people’s opinions more than mine | 2.23 | 1.15 | .67 | -.42 |

| (Mio marito/mia moglie dà più importanza alle opinioni degli altri, che alle mie) | ||||

| I find it difficult to enjoy being alone with my partner | 1.68 | 1.04 | 1.34 | .58 |

| (Mi rimane difficile essere a mio agio nell’intimità con mio marito/mia moglie) | ||||

| My partner and I make a good team | 3.89 | 1.10 | -.94 | .18 |

| (Io e mio marito/mia moglie facciamo una buona squadra) | ||||

| My partner knows how to treat me | 3.66 | 1.10 | -.69 | -.17 |

| (Mio marito/mia moglie sa come trattarmi) | ||||

| I like to spend my free time with my children | 4.32 | .82 | -1.14 | 1.04 |

| (Mi piace passare il tempo libero con il/i mio/miei figlio/i) | ||||

| My partner does not set aside much time for me | 2.49 | 1.15 | .37 | -.72 |

| (Mio marito/mia moglie mi dedica poco tempo) | ||||

| I usually have to shout at my children to make them obey me | 2.54 | 1.12 | .41 | -.49 |

| (Devo sempre alzare la voce perché il/i mio/miei figlio/i mi obbediscano) | ||||

| My partner knows how to listen to me | 3.69 | 1.02 | -.47 | -.36 |

| (Mio marito/mia moglie mi sa ascoltare) | ||||

| My partner is affectionate with me | 3.58 | 1.21 | -.53 | -.73 |

| (Mio marito/mia moglie si dimostra molto affettuoso/a con me) | ||||

| I think my children do not know how to treat me | 2.48 | 1.18 | .44 | -.70 |

| (Penso che il/i mio/miei figlio/i non sa/sanno come trattarmi) | ||||

| My partner helps me to be stronger | 3.68 | 1.20 | -.57 | -.74 |

| (Mio marito/mia moglie mi aiuta ad essere più forte) | ||||

| I openly acknowledge those times when my children have done the right thing | 4.40 | .87 | -1.70 | 2.01 |

| (Riconosco apertamente quando il/i mio/miei figlio/i fanno le cose per bene) | ||||

| My children often get on my nerves | 2.59 | .89 | .63 | .32 |

| (Sento che il/i mio/miei figlio/i mi fanno innervosire molto spesso) | ||||

| My partner and I row every day about the slightest thing | 2.33 | 1.13 | .59 | -.53 |

| (Mio marito/mia moglie ed io discutiamo ogni giorno su qualsiasi cosa) | ||||

| I am convinced that my children only do as they’re told when they are threatened with punishment | 2.18 | 1.20 | .75 | -.46 |

| (Sono convinto/a che il/i mio/miei figlio/i obbediscono quando li si minaccia di un castigo) | ||||

| I think my partner and I disagree about most things | 2.35 | 1.11 | .67 | -.26 |

| (Penso che io e mio marito/mia moglie siamo in disaccordo su molte cose) | ||||

| My partner and I can talk calmly about anything | 3.81 | 1.04 | -.53 | -.58 |

| (Io e mio marito/mia moglie dialoghiamo tranquillamente su qualsiasi cosa) |

Note: CERFB = Cuestionario de Evaluación de las Relaciones Familiares Básicas: items in English and Italian (in brackets); M = Mean; SD = Standard Deviation; SK = Skewness; KU = Kurtosis.

The items have been translated into English through a mixed forward – and back-translation procedure. The scale is available for further validation studies free of charge from any of the authors.

The results showed that no item had extreme means or a standard deviation close to zero. Furthermore, skewness and kurtosis were below |2|. Therefore, no item was deleted.

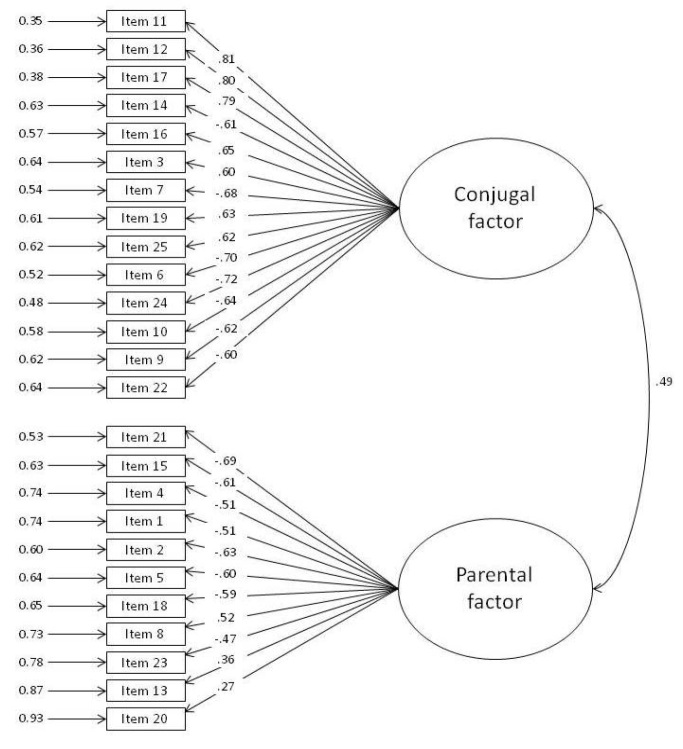

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

In line with the basic family relations theory of Linares (1996, 2002, 2007, 2012), we used CFA through structural equation modelling (SEM; Worthington and Whittaker 2006) via LISREL 8.54 (Jöreskog and Sörbom 2001) in order to replicate the original factor structure. The model consists of two latent factors that represent two latent variables: Conjugal and parenting functions, which are correlated. The 25 items are considered as observed variables: 14 explain the Conjugal factor (items 3, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 16, 17, 19, 22, 24 and 25) and 11 the Parenting factor (items 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 13, 15, 18, 20, 21 and 23). The sample size (N = 228) exceeds the classical conservative recommendations of a minimum of between 5 and 10 cases per variable, of 5 cases per estimated parameter or about 200 cases in absolute terms (Worthington and Whittaker 2006; Kline 2011). Data preparation also included analysis and treatment of missing data and univariate and multivariate normality (Callea et al. 2016).

The hypothesized model was tested using the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) method on the variance-covariance matrix of the CERFB items (Hair et al. 2006). Goodness-of-fit was assessed with the χ2 to degrees of freedom ratio (χ2/df < 3), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA < .80) and its confidence interval (RMSEA CI; lower limit of 0 and upper limit of .80), the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR < .80) and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI ≥ .95; Hooper et al. 2008). However, CFI value between 0.90 and 0.95 should be considered acceptable (Chirumbolo et al. 2017).

As presented in figure 1, the CFA results support the two-factor model because the fit indices meet the criteria for adequacy of fit: χ2/df is 2.59 (710.7/274), RMSEA is .08 [90% CI = .07, .09], SRMR is .07 and CFI is .92.

Figure 1.

Results of confirmatory factorial analysis

Reliability and Convergent Validity

The analysis of the CERFB’s internal consistency in the Italian general population shows homogeneity among the items of each scale: Conjugal (α = .92) and Parenting (α = .80). Therefore, the two factors achieved good internal consistency.

Furthermore, this study examined Pearson’s correlations between the scales of the CERFB and those of other measures used in clinical and research contexts to assess the family, in order to investigate of the CERFB’s convergent and divergent validity. The results showed that Conjugal and Parenting factors are positively and significantly correlated with FACES IV’s balanced scales, Cohesion and Flexibility, Family Communication and Family Satisfaction, whereas they are negatively and significantly correlated with FACES IV’s unbalanced scales, Chaotic and Disengaged. No significant correlations were shown between the Conjugal and Parenting functions on the one hand and the FACES IV Rigid and Enmeshed scales on the other.

Cronbach’s alpha and Pearson correlations between the CERFB’s scales and those of the FACES IV, the FCS and the FSS are shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Cronbach’s alpha and correlations of the scales of the CERFB, FACES IV, FCS and FSS

| Scales | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Conjugal | .92 | |||||||||

| 2. | Parenting | .41** | .80 | ||||||||

| 3. | Cohesion | .64** | .42** | .82 | |||||||

| 4. | Flexibility | .53** | .20** | .61** | .83 | ||||||

| 5. | Rigid | .08 | -.07 | -.03 | .27** | .58 | |||||

| 6. | Chaotic | -.21** | -.20** | -.27** | -.30** | .15* | .55 | ||||

| 7. | Enmeshed | -.05 | -.15 | -.05 | .13 | .43** | .34** | .66 | |||

| 8. | Disengaged | -.48** | -.31** | -.54** | -.18* | .24** | .49** | .42** | .74 | ||

| 9. | FCS | .60** | .34** | .65** | .62** | .04 | -.11 | .10 | -.26** | .87 | |

| 10. | FSS | .61** | .33** | .67** | .65** | .05 | -.12 | .10 | -.28** | .76** | .92 |

Note. Values along main diagonal are coefficient alphas for each variable.

* p < .05; ** p < .01

Normative Data

Finally, the normative scores for the Conjugal and Parenting CERFB scales in the Italian general population were obtained: direct, base 10 and typified total scores were scaled in percentiles (table 3).

Table 3.

Mean, median and percentiles of the CERFB’s factors direct, base 10 and typified scores in Italian general population

| Percentile | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale | scores Total | M (SD) | Median | IQR | 5th | 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 90th | 95th |

| Conjugal | Direct | 52.89 (10.85) | 55.00 | 15.00 | 31.00 | 37.00 | 46.00 | 55.00 | 61.00 | 65.00 | 69.00 |

| Base 10 | 6.50 (2.21) | 6.93 | 3.06 | 2.04 | 3.26 | 5.10 | 6.93 | 8.16 | 8.97 | 9.79 | |

| Typified | 50.00 (10.00) | 51.94 | 13.81 | 29.83 | 35.36 | 43.65 | 51.94 | 57.46 | 61.15 | 64.83 | |

| Parenting | Direct | 39.55 (5.35) | 40.00 | 6.00 | 30.85 | 32.70 | 37.00 | 40.00 | 43.00 | 46.00 | 48.00 |

| Base 10 | 6.26 (1.91) | 6.42 | 2.15 | 3.16 | 3.82 | 5.35 | 6.42 | 7.50 | 8.57 | 9.28 | |

| Typified | 50.00 (10.00) | 50.84 | 11.21 | 33.75 | 37.21 | 45.23 | 50.84 | 56.44 | 62.04 | 65.77 | |

Note. IQR = Inter-Quartile Range.

Discussion and conclusions

Some authors (e.g., Sprenkle and Piercy 2005) have pointed out the gap between research and clinical practice in the family therapy field, while others have called attention to the lack of an instrument that at the same time assesses different family functions in the Italian context (Baiocco et al. 2012). Therefore, the present paper proposed the validation of the Italian version of the “Cuestionario de Evaluación de las Relaciones Familiares Básicas” (CERFB), a questionnaire that evaluates family relations by measuring Conjugal and parenting functions. The Italian version of the CERFB can be considered valid and reliable because it meets adequacy criteria for its use (Gudmundsson 2009).

In fact, the CERFB maintains adequate psychometric properties in its first international version. In particular, CFA supported the same two-factor structure as that of the EFA of the original version of the CERFB; a Conjugal factor with 14 items and a Parenting factor with 11 items (Ibáñez et al. 2012). These results are in accordance with the two functions described in the basic family relations theory of Linares (1996, 2002, 2006, 2007, 2012), providing further support to theoretical model. Furthermore, the Italian version of the CERFB showed good reliability; specifically, the internal consistency analysis showed adequate homogeneity among the items of each scale, with the Cronbach’s alphas for the Conjugal scale and the Parenting scale very similar to those of the original version.

The set of correlational results of the CERFB with the other three family measures complement the construct validity of both scales first suggested by the factor analysis (Keszei et al. 2010). The Conjugal factor was positively related to Cohesion and Flexibility, Family Communication and Family Satisfaction, and it was negatively related to Chaotic and Disengaged. The Parenting factor showed the same pattern of correlations. These results suggest that Conjugal and Parenting functions could be considered two basic family relations, in line with Linares’s Theory. As a matter of fact, our results suggest that when a family displays high levels of Conjugal and Parenting functions, the other positive characteristics of a family (i.e. the capacity of a family to communicate and to adapt correctly to members’ needs, family cohesion and the satisfaction) will tend to increase. Conversely, when two functions are low, problematic family relations (i.e., the family rigidity or enmeshed relationship) will tend to increase. These results may be particularly useful in clinical applications. Therefore, the correlations’ results support the convergent and divergent validity of the CERFB.

Overall, the Italian version of the CERFB presents good psychometric properties and can be considered a useful tool in simultaneously assessing basic family relations through Conjugal and parenting functions, as described by Linares (1996, 2012) and discriminating these functions. More importantly, it is simple and can be administered quickly. Therefore, in order to interpret the CERFB’s scores in the Italian general population, a reference scale is offered based on the data from the sample of this study.

There are some limitations to this study. The sample (N = 228), although sufficient for a validation (Worthington and Whittaker 2006, Kline 2011), was recruited from central and southern of Italy; in further studies, it would be desirable to increase the number of participants and to recruit participants from a greater variety of places of origin to obtain greater representativeness. There is a second limitation with regard to the difficulty experienced in finding validated Italian measures that assess family relationships to complete the validity analysis. However, this second limitation is connected to the main strength of the present study, in that it aims to fill this research gap. A third limitation stems from the fact that reliability was tested only with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, because just one administration of the instrument was carried out; in further studies, it would be desirable to further test the stability of the CERFB’s results via additional administrations of the instrument and the calculation of its test-retest reliability.

Considering the findings of the present study, an important aim of future research should be the validation of the CERFB in the Italian clinical population (Colombo and Barbini 2005, Gudmundsson 2009, American Educational Research Association 2014). Following this line of investigation, it could become a useful tool for empirical relational discriminative diagnosis between non-clinical and different groups of clinical families, for the purposes of prescribing suitable interventions and to designing prevention programs for each family. The Spanish version has already shown satisfactory results in this regard (Campreciós et al. 2014, Campreciós 2016). Another future line of investigation would be related to the adaptation of the test to new family forms, thus expanding its use (Linares 2002).

The findings of this study as part of the overall validation project of the CERFB have clear implications for clinical practice. The time-efficient and convenient use of the instrument makes the CERFB valuable. In light of the importance of family relationships, the instrument is worthy of consideration for future inclusion in the protocols and guidelines for promotion, prevention and treatment within the mental health field, thanks to the role it can play in fostering holistic assessment.

In conclusion, the CERFB can enable us to better understand basic family relations in the Italian population via the assessment of Conjugal and parenting functions, which is relevant for the improvement of the effectiveness of psychological prevention and intervention.

References

- American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, and National Council on Measurement in Education (2014). The standards for educational and psychological testing. American Educational Research Association, Washington. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association (2010). Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct. http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/principles.pdf.

- Baiocco R, Cacioppo M, Laghi F, Tafa M (2012). Factorial and construct validity of FACES IV among Italian adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies 22, 962-970. [Google Scholar]

- Barbaranelli C (2007). Analisi dei dati. LED, Milano. [Google Scholar]

- Bessi B, Chistolini M, Cirillo S, Colombari M, Diano D, Vizziello GMF, Verardo M (2009). Buone pratiche per la valutazione della genitorialità: raccomandazioni per gli psicologi. Pendragon, Bologna. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin RW (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 1, 185-216. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM (2016). Adaptation of assessment scales in cross-national research: Issues, guidelines, and caveats. International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation 5, 51-65. [Google Scholar]

- Callea A, Cacioppo M, Lucchetti F, Caretti V (2016). Internet use and psychosocial well-being in an italian adult sample. Clinical Neuropsychiatry 13, 1, 3-6. [Google Scholar]

- Campreciós M (2016). Validation and clinical applicability of the Cuestionario de Evaluación de las Relaciones Familiares Básicas (CERFB) in eating disorders. Doctoral dissertation. http://hdl.handle.net/10803/352474. [PubMed]

- Campreciós M, Vilaregut A, Virgili C, Mercadal L, Ibáñez N (2014). Relaciones familiares básicas en familias con un hijo con trastorno de la conducta alimentaria. The UB Journal of Psychology 44, 311-326. http://www.ub.edu/psicologia/castellano/anuario-de-psicologia. [Google Scholar]

- Chirumbolo A, Urbini F, Callea A, Lo Presti A, Talamo A (2017). Occupations at Risk and Organizational Well-Being: An Empirical Test of a Job Insecurity Integrated Model. Frontiers in Psychology 8, 2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo C, Barbini B (2005). The importance of assessment. Clinical Neuropsychiatry 2, 3, 135-136. [Google Scholar]

- Gentili P, Contreras L, Cassaniti M, D’Arista F (2002). La Dyadic Adjustment Scale. Una misura dell’adattamento di coppia. Minerva Psichiatrica 43, 107-116. [Google Scholar]

- Guarino A, Di Blasio P, D’Alessio M, Camisasca E, Serantoni G (2008). Parenting Stress Index Short Form: Adattamento italiano. Giunti, Firenze. [Google Scholar]

- Gudmundsson E (2009). Guidelines for translating and adapting psychological instruments. Nordic Psychology 61, 29-45. [Google Scholar]

- Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE, Tatham RL (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6ª ed.). Pearson Education, New Jersey. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper D, Coughlan J, Mullen MR (2008). Structural equation modelling: guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 6, 53-60. http://www.ejbrm.com [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez N, Linares JL, Vilaregut A, Virgili C, Campreciós M (2012). Propiedades psicométricas del Cuestionario de Evaluación de las Relaciones Familiares Básicas (CERFB). Psicothema 24, 489-494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D (2001). LISREL 8.5 for Windows. Scientific Software International, Skokie. [Google Scholar]

- Keszei AP, Novak M, Streiner DL (2010). Introduction to health measurement scales. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 68, 319-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). Guilford Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Lanz M (1997). Parent-Offspring Communication Scale: Applicazione ad un campione italiano. Bollettino di Psicologia Applicata 224, 33-38. [Google Scholar]

- Linares JL (1996). Identidad y narrativa. La terapia familiar en la práctica clínica. Paidós, Barcelona. [Google Scholar]

- Linares JL (2002). Del abuso y otros desmanes. El maltrato familiar, entre la terapia y el control. Paidós, Barcelona. [Google Scholar]

- Linares JL (2006). Complex love as relational nurturing: An integrating ultramodern concept. Family Process 45, 101-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linares JL (2007). La personalidad y sus trastornos desde una perspectiva sistémica. Clínica y Salud 18, 381-399. [Google Scholar]

- Linares JL (2012). Terapia familiar ultramoderna. La inteligencia terapéutica. Barcelona, Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Olson DH (1995). Family satisfaction scale. Life Innovations, Minneapolis. [Google Scholar]

- Olson DH (2011). FACES IV and the circumplex model: Validation study. Journal of Conjugal and Family Therapy 3, 64-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson DH, Gorall DM (2006). FACES IV and the circumplex model. Life Innovations, Minneapolis. [Google Scholar]

- Poli A, Melli G, Bulli F, Carraresi C, Gelli S (2016). Development and validation of the Self-Directed Moral Disgust Scale in a large Italian non-clinical sample. Clinical Neuropsychiatry 13, 6, 115-121. [Google Scholar]

- Scinto A, Marinangeli MG, Kalyvoka A, Daneluzzo E, Rossi A (1999). The use of the Italian version of the Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI) in a clinical sample and in a student group: An exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis study. Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale 8, 276-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanier GB (1976). Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and Family 38, 15-28. [Google Scholar]

- Sprenkle DH, Piercy FP (2005). Research methods in family therapy (2nd ed). Guilford, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Worthington RL, Whittaker TA (2006). Scale development research: a content analysis and recommendations for best practices. The Counseling Psychologis 34, 806-838. [Google Scholar]