Abstract

Aggression issues experienced on the workplace has been globally recognized as a public health issue. Nurses are exposed to a very high risk of becoming victims of workplace aggression.

Objective

The study describes this phenomenon from nurses perspective in two units resulted to be the more exposed to aggressive behaviour at San Raffaele Hospital in Milan.

Method

We applied a semi-structured interview to volunteer staff members of the rehabilitative psychiatric and neurological wards of San Raffaele Hospital in Milan. We collected general data on 55 workers, their previous experiences of suffered or witnessed aggression, locations and timing of attacks, methods used to report attacks, subjective opinion about drives, management modalities of aggressive phenomena and any physical and/or psychological impacts.

Results

85% suffered and 80% witnessed aggressions, especially non-physical, mostly in the corridor at 7.00-8.00 pm. The 78.7% reported no emotional trauma whereas the 21.3% reported physical injury. Aggressive behaviours linked to the patient’s pathology were more easily tolerated. According to participants opinion, the interaction between psychopathological aspects and environmental features increase the risk of an aggressive behaviour. The 81% of interviewed reported to be able to manage patients’ aggressiveness considering their previous experiences more helpful than training.

Discussion

We confirm literature data about high percentage of witnessed and suffered aggression and the well-known healthworkers tendency to consider violent and aggressive behaviours as “part of the job” . Professional figures need to be formed with specific trainings focused on early identification, communication strategies, and de-escalation techniques.

Keywords: healthworkers, aggression, rehabilitation, psychiatry, neurology

Introduction

Aggression and violence issues experienced on the workplace has been globally recognized as a public health issue. Workplace aggression has been defined as all the situations where people suffer abuse, threats, or aggression in contexts related to their job, including transportation to and from work, which involves an explicit or implicit threat to their work, safety, their well-being and their health (Cashmore, Indig, Hampton, Hegney, & Jalaludin, 2012; Park, Cho, & Hong, 2015).

However, there are some methodological issues in the identification and the detection of aggression: indeed, some studies just show aggressions which lead to physical injuries or threats of aggression, some others consider the subjective perception of threats or verbal abuses. Moreover, the entity and frequency of aggressions are not properly documented, both because of the lack of an internationally known standard to measure violence and aggression, and for the stigma tied to victims of violence. When aggression is reported, results vary due to the difference among the phenomenon definition and because of the heterogeneous measurement tools adopted (O’Leary-Kelly, Griffin, & Glew, 1996; Rippon, 2000).

Healthcare workers, especially nurses, are exposed to a very high risk of becoming victims of workplace violence. Indeed, according to the literature, nurses run a sixteen-times bigger risk than any other worker, due to the direct contact with the patients and their caregivers (Elliot & Church, 1997; El-Gilany, El-Wehady, & Amr, 2010; Kitaneh & Hamdan, 2012; Lanza, Zeiss, & Rierdan, 2006; Nan, & Heo, 2007; O’Connell, Young, Brooks, Hutchings, & Lofthouse, 2000; Papalia & Magnavita, 2003; Winstanley & Whittington, 2002; Zoni, Lucchini, & Alessio, 2010).

In literature, the estimates of the frequency of physical attacks in a year vary between 3% and over 70% (Kamchuchat, Chongsuvivatwong, Oncheunjit, & Sangthong, 2008; Magnavita & Heponiemi, 2012). Additionally, even more difficult appears to evaluate the frequency of non-physical aggression, which accounts for around 38% to 90% of aggression against workers (Gascón et al., 2009; Gerberich et al., 2004; Kamchuchat et al., 2008; Roche, Diers, Duffield, & Catling‐Paull, 2010; Zampieron, Galeazzo, Turra, & Buja, 2010).

According to literature data nurses operating in acute psychiatric units refer to have suffered of episodes of aggression in a percentage ranged from 25% to 80% (Hesketh et al., 2003; Jonker, Goossens, Steenhuis, & Oud, 2008; Moylan & Cullinan, 2011). In this area, principal risk factors which may contribute to the onset of the phenomenon are related to clinical conditions, i.e. substance abuse, mental confusion, psychotic states, or organizational problems, i.e. waiting list, health care workers’ attitude (Hahn et al., 2012; Hodge & Marshall, 2007; Jenkins, Rocke, McNicholl, & Hughes, 1998; National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, 2002; Rintoul, Wynaden, & McGowan, 2009).

An in-depth study of the workplace aggression phenomenon in Italy is relatively recent. The questionnaire “Violent Incident Form” (VIF) was administered to 987 nurses belonging to various hospitals and emergency services of Modena. The 74% of respondents have suffered at least one episode of violence in the last 3 years, with the highest percentage in psychiatric area (84%), mostly physical (40%) or physical and verbal (33%) (Ferri, Reggiani, & Di Lorenzo, 2011).

Physical and moral violence against the workers of a local public health unit in Italy was perspectively studied in the period 2005-2011. The prevalence of the phenomenon was constant in the period under review: each year a worker in ten is physically assaulted, and one in five is subjected to verbal abuse. The professional groups most exposed to violence are nurses and doctors and the areas at greatest risk are the psychiatric care (35.4%) and emergency and first aid (15.9%) (Magnavita & Heponiemi, 2012).

Therefore, due to the under-reporting and the lack of preventive measures, workplace violence could be even more frequent than what statistics suggest (Barling, Duprè, & Kelloway, 2009; Gacki-Smith et al., 2009; Magnavita & Heponiemi , 2012).

The current study aims to describe the prevalence of this phenomenon in the rehabilitative psychiatric and neurological wards of San Raffaele Hospital in Milan.

Method

The present study was conducted from May to July 2019 on a voluntary basis, among the nursing staff belonging to two rehabilitative units, the Mood Disorder Rehabilitation Unit and the Specialized Neurological Rehabilitation Unit of San Raffaele Hospital in Milan. According to the internal record of our organization, these two units resulted to be the more exposed to aggressive behaviour even if inpatients are not in acute phase and in theory less prone to aggressive acts.

The Mood Disorder Unit houses 48 inpatients and Specialized Neurological Rehabilitation houses 17 inpatients.

The purpose of the present investigation was to describe the phenomenon of aggressive behaviors as perceived by the staff using a semi-structured interview. The duration of interview was variable with an average of fifteen minutes and the following information will be collected: general data on the workers (i.e. the occupation type and how long it has been carried out); previous experiences in the workplace of suffered aggression (SA) or witnessed aggression (WA); locations and timing of attacks; methods used to report attacks. Moreover, personal opinion about drives, management modalities of violent phenomena and physical and/or psychological impacts were asked.

Results

The sample consisted of 55 participants: 14 males (25.45%) and 41 females (74.55%) whose average age is 40.05 ± 10.6 (min 23, max 63). The 63.6% were recruited in the psychiatric ward and the 36.4% in the neurological ward, with a career in same department of 98 ± 77.6 weeks (mean ± SD): 69% (38) were hired as professional nurses, 11% (6) as healthcare assistant, 7.3% (4) as residents, 7.3% (4) as social educators and finally 5.4% (3) as head nurses .

According to staff answers the 84.5% (47/55) suffered aggression and the 80% (44/55) witnessed an aggression. Among them, the 78.7% reported no emotional trauma related to the experience of aggression, whereas the 21.3% reported physical injury.

Most suffered aggressions consisted of shouting (87%), and offenses (85%); most witnessed aggressions consisted in offenses (93.2%) and intimidations (75%) (table 1).

Table 1.

Type of aggressive behaviours

| Type of aggression | Suffered: 85.4% (N=47/55) | Witnessed: 80% (N=44/55) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shouting | 87% | N=41/47 | 50% | N=22/44 |

| Offences | 85% | N=40/47 | 93.2% | N=41/44 |

| Intimidations | 48.9% | N=23/47 | 75% | N=33/44 |

| Damage to furniture | 53.2% | N=25/47 | 59% | N=26/44 |

| Kicks | 38.3% | N= 18/47 | 57% | N=25/44 |

| Drags | 31.9% | N=15/47 | 43.2% | N=19/44 |

| Shoves | 23.4% | N=11/47 | 52.3% | N=23/44 |

| Throwing objects | 19.1% | N=9/47 | 34.1% | N=15/44 |

| Threats | 34% | N=16/47 | 57% | N=25/44 |

| Spitting | 44.7% | N=21/47 | 41% | N=18/44 |

| Sexual harassment | 46.8% | N=22/47 | 57% | N=25/44 |

During the interviews it emerged that places were aggressive behaviours mostly occurred were: the corridor (31.8%); the hospital room (20.5 %), the common room (15.9%), the TV room (11.4%), the garden and the medical office (4.5%).

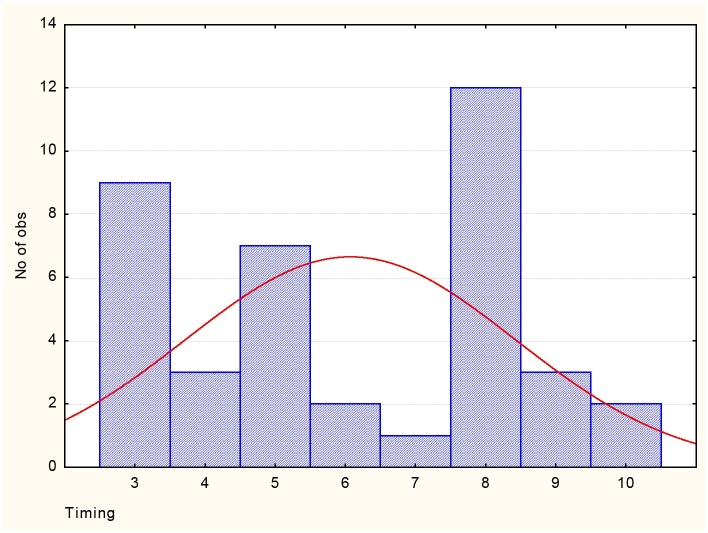

The time slots most involved were 7.00-8.00 pm and 7.00-8.00 am (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Timing of aggressive behaviours

1= before breakfast; 2= breakfast; 3= morning; 4= lunch; 5= afternoon; 6= before dinner; 7= dinner; 8= before evening therapy; 9= night; 10=unknown

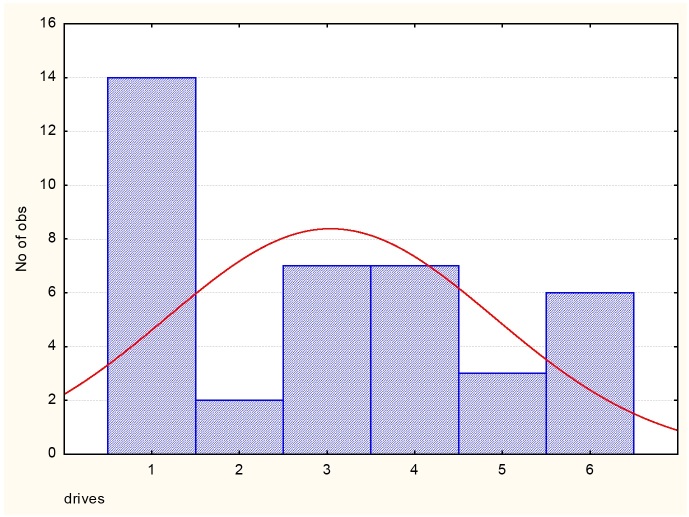

According to participants opinion, psychopathological aspects and environmental features were crucial to the implementation of the aggressive behaviour as described in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Drives of aggressive behaviours

1= symptoms; 2=intrusion; 3= interpersonal reactivity; 4=jealousy; 5= mental confusion; 6=environmental

Table 2 shows the reporting methods used by nurses for suffered and witnessed attacks

Table 2.

Reporting typology

| Types of reporting | SA | WA |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical diary | 37% | 46.9% |

| Nursing record | 28.6% | 25% |

| Equipe | 17.1% | 15.6% |

| Corporate reporting model | 8.6% | 6.25% |

The 81% of interviewed reported to be able to manage the aggressiveness of the patients thanks to their experience considering their previous experience more helpful than training. Moreover the 76.4% of interviewed reported to had been adequately supported after the aggression.

Discussion

The aim of our study was to explore the episodes of aggression in psychiatric and neurological rehabilitative units of San Raffaele Hospital in Milan. The risk of becoming victim of aggression is higher for nurses and health workers and in particular in psychiatric settings. Psychological and verbal attacks are more difficult than physical assaults to identify, but it seems that they afflict between 38% and 90% of workers (Gascón et al., 2009; Gerberich et al., 2004; Kamchuchat et al., 2008; Lin & Liu, 2005; Roche et al., 2010; Zampieron et al., 2010).

Our results are in line with these literature data with a percentage of witnessed and suffered aggression respectively of 80 and 85.4% consisting mostly in verbal attacks and intimidations.

None of the operators interviewed suffered psychological and emotional effects due to the aggression. The reasons why the number of complaints are so low seems to be in line with founds in other countries and it could be related to a well-known tendency to consider episodes of violence as an integral part of the work among health workers in psychiatric units. This habit could be the reason why studies carried out by psychiatric nurses reaffirm that violent behaviours is underestimated, mostly in the psychiatric health departments (Calabrò, 2016). In fact, workers often consider violent and aggressive behaviours as “part of the job” and, for this reason, they do not report what happened (Nachreiner, Gerberich, Ryan, & McGovern, 2007). The same results were found in a recent paper conducted into an Italian population of 51 health workers with a diffuse belief that workplace violence is a normal part of the work. Interestingly, in our sample, also subjects working at the neurology unit seemed to share the same reasons, considering psychopathological conditions the first drive for aggressive behaviours (Cannavò, Colaiuda, Rescigno, & Fioravanti, 2017).

In addition to psychopathological aspects, our interviewed considered possibly drives for aggressive behaviours other contextual factors, such as the intrusion in the private space such as the bedroom, wrong interpretation of sentences or behaviours among patients, jealousy and intrusive behaviours in shared spaces. In fact according to our results sites and time-slots where aggressions were those in which interaction were more probable.

This is in line with literature data suggesting that aggressive and violent behaviours must be considerate in all their aspects: both the mental pathology of the patient and the environmental conditions of the department can be configured as a triggers for aggressive behaviours (Angland, Dowling, & Casey, 2014; Gacki-Smith et al., 2009; Ramacciati, Ceccagnoli, & Addey, 2015).

The present study confirms that nurses dealing with psychiatric and neurologic patients are exposed to violence phenomena on workplace. Moreover, since the professionals are aware of such risk as an intrinsic characteristic of psychiatric and neurological setting, they seem not to develop signs of suffering, neither psychological, nor professional. On the contrary, it looks like the continuous exposure to such aggression may have tempered the healthcare workers, allowing them to build a specific capacity to recognize those signs preceding the acting out. Moreover, it emerged that the employees would feel more safe and confident if they could carry out a specific training to know how to handle this kind of events.

It was highlighted by our interviewed who were victims of an aggressive behavior that they have had the possibility to be supported and this had represented an instrument to face this kind of situations.

In order to deal with episodes of violence and to reduce them, it is essential for healthcare workers to have an adequate organization, through the use of guidelines, context-based protocols, training courses and a continuous cooperation of the whole equipe. Additionally, it is very important for the workers to have the possibility to have access to psychological support.

The current study presented some limitations. First of all, this is a preliminary study and therefore is not exhaustively explaining the observed phenomenon. Moreover, a larger sample and a more accurate statistical analysis in future researches is required. In addition, using a semi-structured interview, the investigated elements are based on memories which can be distorted due to the relation to a highly involving episode, such as aggression. Anyway, thanks to the employment of a semi-structured interview based on ad hoc questions, we were able to evaluate personal considerations of the workers.

From the obtained results it is important to highlight that in a study of violent and aggressive behavior a multidisciplinary approach is required. Indeed, an awareness of the level of aggressiveness present in the workplace is necessary, in order to correctly recognize and manage it. The possession of specific knowledges and skills contributes to a good level of job satisfaction (Van Saane, Sluiter, Verbeek, & Frings‐Dresen, 2003). Moreover, our results underlined the need for the professional figures involved to be formed in the best way with specific trainings focused on early identification, communication strategies, and deescalation techniques: in this way, if they are correctly prepared, they will know how to handle the situation, in order not only to reduce the burnout risk, but also to increase the safety in hospitals and medical structures (Alexander, Fraser, & Hoeth, 2004; Astrom et al., 2004; Carlini et al., 2016; Estryn-Behar et al., 2008; Ito, Eisen, Sederer, Yamada, & Tachimori, 2001).

References

- Alexander, C., Fraser, J., & Hoeth, R. (2004). Occupational violence in an Australian healthcare setting: implications for managers. Journal of Healthcare Management, 49(6), 377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angland, S., Dowling, M., & Casey, D. (2014). Nurses’ perceptions of the factors which cause violence and aggression in the emergency department: a qualitative study. International emergency nursing, 22(3), 134-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Åström, S., Karlsson, S., Sandvide, Å., Bucht, G., Eisemann, M., Norberg, A., & Saveman, B. I. (2004). Staff’s experience of and the management of violent incidents in elderly care. Scandinavian journal of caring sciences, 18(4), 410-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barling, J, Duprè, K. E., & Kelloway, E. K. (2009). Predicting workplace aggression and violence. Annu. Rev Psychol 60, 671-92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrò, A. (2016). La violenza verso gli infermieri in psichiatria: un’indagine multicentrica. Rivista L’Infermiere 1, 39-43. [Google Scholar]

- Cannavò, M., Fusaro, N., Colaiuda, F., Rescigno, M., & Fioravanti, M. (2017). Studio preliminare sulla presenza e la rilevanza della violenza nei confronti del personale sanitario dell’emergenza. Clin Ter, 168(2), 99-112. [Google Scholar]

- Carlini, L., Fidenzi, L., Gualtieri, G., Nucci, G., Fagiolini, A., Coluccia, A., & Gabbrielli, M. (2016). Burnout syndrome. Legal medicine: analysis and evaluation INAIL protection in cases of suicide induced by burnout within the helping professions. Rivista di Psichiatria, 51(3), 87-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashmore, A. W., Indig, D., Hampton, S. E., Hegney, D. G., & Jalaludin, B. B. (2012). Workplace violence in a large correctional health service in New South Wales, Australia: a retrospective review of incident management records. BMC Health Services Research, 12(1), 245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Gilany, A. H., El-Wehady, A., & Amr, M. (2010). Violence against primary health care workers in Al-Hassa, Saudi Arabia. Journal of interpersonal violence, 25(4), 716-734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot, A. J., & Church, M. A. (1997). A hierarchical model of approach and avoidance achievement motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(1), 218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estryn-Behar, M., Van Der Heijden, B., Camerino, D., Fry, C., Le Nezet, O., Conway, P. M., & Hasselhorn, H. M. (2008). Violence risks in nursing—results from the European “NEXT” Study. Occupational medicine, 58(2), 107-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferri, P., Reggiani, F., & Di Lorenzo, R. (2011). I comportamenti aggressivi nei confronti dello staff infermieristico in tre differenti aree sanitarie. Professioni Infermieristiche, 64 (3), 143-150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gacki-Smith, J., Juarez, A. M., Boyett, L., Homeyer, C., Robinson, L., & MacLean, S. L. (2009). Violence against nurses working in US emergency departments. Journal of Nursing Administration, 39(7/8), 340-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gascón, S., Martínez-Jarreta, B., González-Andrade, J. F., Santed, M. Á., Casalod, Y., & Rueda, M. Á. (2009). Aggression towards health care workers in Spain: a multifacility study to evaluate the distribution of growing violence among professionals, health facilities and departments. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health, 15(1), 29-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerberich, S. G., Church, T. R., McGovern, P. M., Hansen, H. E., Nachreiner, N. M., Geisser, M. S., & Watt, G. D. (2004). An epidemiological study of the magnitude and consequences of work related violence: the Minnesota Nurses’ Study. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 61(6), 495-503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn S., Muller M., Hantikainen V., Kok G., Dassen T., Halfens R. J. G., (2012). Risk factors associated with patient and visitor violence in general hospitals: Results of a multiple regression analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 1-12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hesketh, K. L., Duncan, S. M., Estabrooks, C. A., Reimer, M. A., Giovannetti, P., Hyndman, K., & Acorn, S. (2003). Workplace violence in Alberta and British Columbia hospitals. Health policy, 63(3), 311-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge, A. N., & Marshall, A. P. (2007). Violence and aggression in the emergency department: a critical care perspective. Australian Critical Care, 20(2), 61-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito, H., Eisen, S. V., Sederer, L. I., Yamada, O., & Tachimori, H. (2001). Factors affecting psychiatric nurses’ intention to leave their current job. Psychiatric services, 52(2), 232-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, M. G., Rocke, L. G., McNicholl, B. P., & Hughes, D. M. (1998). Violence and verbal abuse against staff in accident and emergency departments: a survey of consultants in the UK and the Republic of Ireland. Emergency Medicine Journal, 15(4), 262-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonker, E. J., Goossens, P. J. J., Steenhuis, I. H. M., & Oud, N. E. (2008). Patient aggression in clinical psychiatry: perceptions of mental health nurses. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 15(6), 492-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamchuchat, C., Chongsuvivatwong, V., Oncheunjit, S., Yip, T. W., & Sangthong, R. (2008). Workplace violence directed at nursing staff at a general hospital in southern Thailand. Journal of Occupational Health, 50(2), 201-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitaneh, M., & Hamdan, M. (2012). Workplace violence against physicians and nurses in Palestinian public hospitals: a cross-sectional study. BMC health services research, 12(1), 469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza, M.L., Zeiss, R., & Rierdan, J. (2006). Violence against psychiatric nurses: sensitive research as science and intervention. Contemporary Nurse, 21(1), 71-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y. H., & Liu, H. E. (2005). The impact of workplace violence on nurses in South Taiwan. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 42(7), 773-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnavita, N., & Heponiemi, T. (2012). Violence towards health care workers in a public health care facility in Italy: a repeated cross-sectional study. BMC health services research, 12(1), 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moylan, L. B., & Cullinan, M. (2011). Frequency of assault and severity of injury of psychiatric nurses in relation to the nurses’ decision to restrain. Journal of psychiatric and mental health nursing, 18(6), 526-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachreiner, N. M., Gerberich, S. G., Ryan, A. D., & McGovern, P. M. (2007). Minnesota nurses’ study: perceptions of violence and the work environment. Industrial Health, 45(5), 672-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nan, X., & Heo, K. (2007). Consumer responses to corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives: Examining the role of brand-cause fit in cause-related marketing. Journal of Advertising, 36(2), 63-74. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell, B., Young, J., Brooks, J., Hutchings, J., & Lofthouse, J. (2000). Nurses’ perceptions of the nature and frequency of aggression in general ward settings and high dependency areas. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 9(4), 602-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary-Kelly, A. M., Griffin, R. W., & Glew, D. J. (1996). Organization-motivated aggression: A research framework. Academy of management review, 21(1), 225-253. [Google Scholar]

- Papalia, F., & Magnavita, N. (2003). Unknown occupational risk: physical violence at the workplace. Giornale Italiano di Medicina del Lavoro ed Ergonomia, 25(3), 176- 177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, M., Cho, S. H., & Hong, H. J. (2015). Prevalence and perpetrators of workplace violence by nursing unit and the relationship between violence and the perceived work environment. Journal of nursing scholarship, 47(1), 87-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramacciati, N., Ceccagnoli, A., & Addey, B. (2015). Violence against nurses in the triage area: an Italian qualitative study. International Emergency Nursing, 23(4), 274-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rintoul, Y., Wynaden, D., & McGowan, S. (2009). Managing aggression in the emergency department: promoting an interdisciplinary approach. International emergency nursing, 17(2), 122-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rippon, T. J. (2000). Aggression and violence in health care professions. Journal of advanced nursing, 31(2), 452-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche, M., Diers, D., Duffield, C., & Catling‐Paull, C. (2010). Violence toward nurses, the work environment, and patient outcomes. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 42(1), 13-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Saane, N., Sluiter, J. K., Verbeek, J. H. A. M., & Frings‐Dresen, M. H. W. (2003). Reliability and validity of instruments measuring job satisfaction—a systematic review. Occupational Medicine, 53(3), 191-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstanley, S., & Whittington, R. (2002). Anxiety, burnout and coping styles in general hospital staff exposed to workplace aggression: a cyclical model of burnout and vulnerability to aggression. Work & Stress, 16(4), 302-315. [Google Scholar]

- Zampieron, A., Galeazzo, M., Turra, S., & Buja, A. (2010). Perceived aggression towards nurses: study in two Italian health institutions. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19(15‐16), 2329-2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoni, S., Lucchini, R., & Alessio, L. (2010). L’integrazione di indicatori oggettivi e soggettivi per la valutazione dei fattori di rischio stress-correlati nel settore sanitario. Giornale Italiano di Medicina del Lavoro ed Ergonomia, 32(3), 332-336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]