Abstract

The role of a global, substrate-driven, enzyme conformational change in enabling the extraordinarily large rate acceleration for orotidine 5’-monophosphate decarboxylase (OMPDC)-catalyzed decarboxylation of orotidine 5’-monophosphate (OMP) is examined in experiments that focus on the interactions between OMPDC and the ribosyl hydroxyl groups of OMP. The D37 and T100’ side chains of OMPDC interact, respectively, with the C-3’ and C-2’ hydroxyl groups of enzyme-bound OMP. D37G and T100’A substitutions result in 1.4 kcal/mol increases in the activation barrier ΔG‡ for catalysis of decarboxylation of the phosphodianion truncated substrate 1-(β-D-erythrofuranosyl)orotic acid (EO), but in larger 2.1–2.9 kcal/mole increases in ΔG‡ for decarboxylation of OMP, and for phosphite dianion-activated decarboxylation of EO. This shows that these substitutions reduce transition state stabilization by the Q215, Y217 and R235 side chain at the dianion binding site. The D37G and T100’A substitutions result in <1.0 kcal/mol increases in ΔG‡ for activation of OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of the phosphoribofuranosyl truncated substrate FO by phosphite dianion. Experiments to probe the effect of D37 and T100’ substitutions on the kinetic parameters for d-glycerol 3-phosphate and d-erythritol 4-phosphate activators of OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of FO show that ΔG‡ for sugar-phosphate activated reactions is increased by ca 2.5 kcal/mol for each −OH interaction eliminated by D37G or T100’A substitutions. We conclude that the interactions between the D37 and T100’ side chains and ribosyl, or ribosyl-like hydroxyl groups are utilized to activate OMPDC for catalysis of decarboxylation of OMP, EO, and FO.

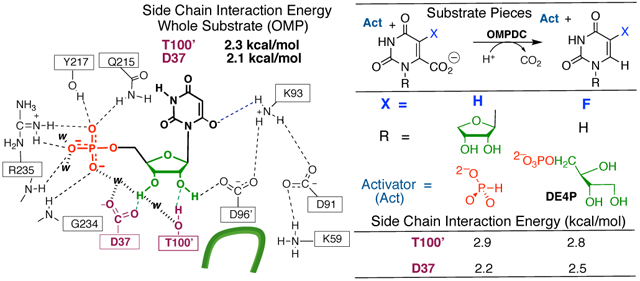

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

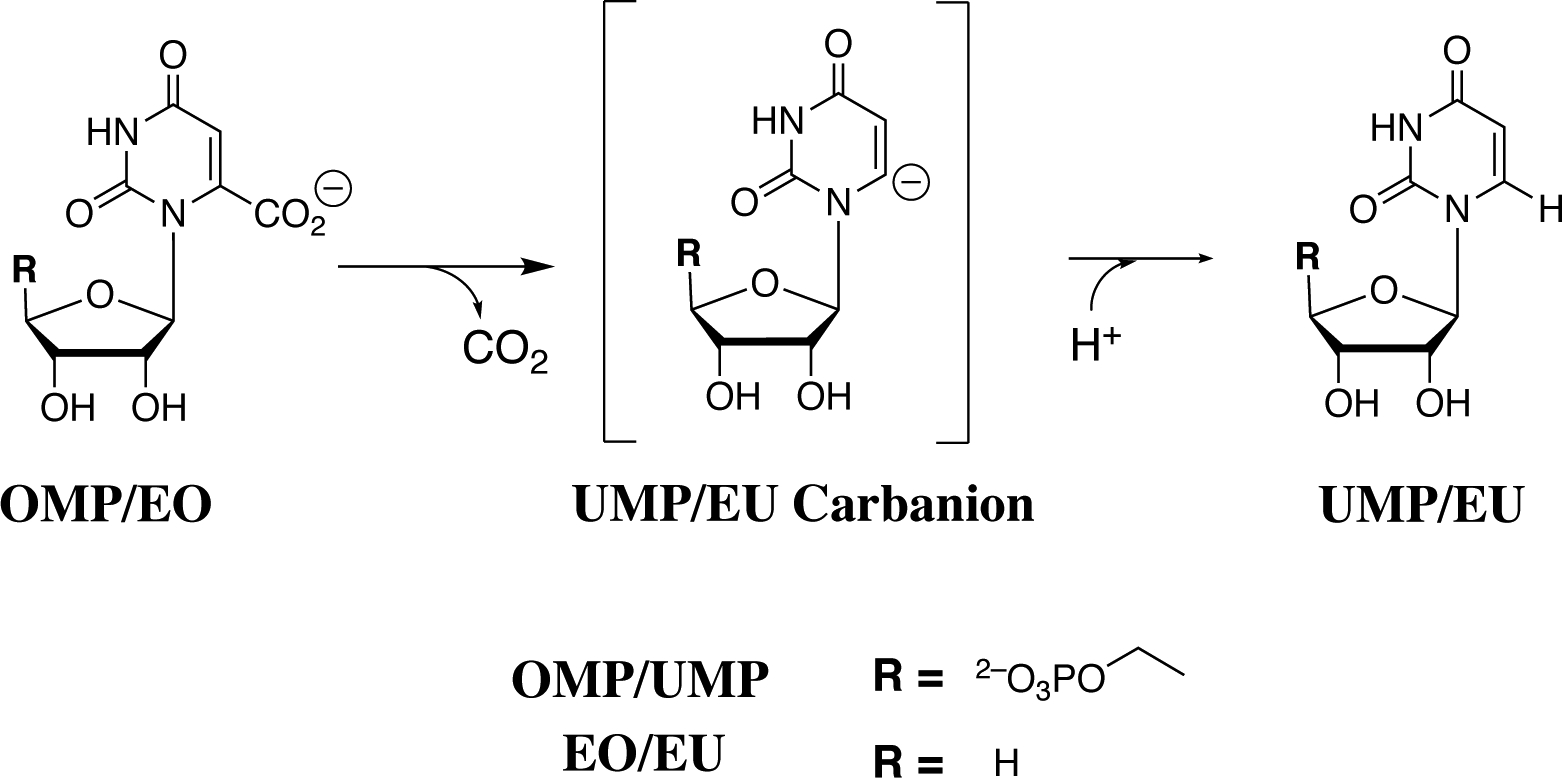

Enzyme catalysis results from stabilization of the enzyme-bound transition state by the protein catalyst.1–3 Interactions between orotidine 5’-monphosphate decarboxylase (OMPDC) and the transition state for enzyme-catalyzed decarboxylation of OMP to form UMP through a UMP-carbanion reaction intermediate (Scheme 1)4, 5 provide a large 31 kcal/mol transition state stabilization,6 but only a modest 8 kcal/mol stabilization of the Michaelis complex to OMP.7 This high specificity in transition state binding is one hallmark of proficient enzymatic catalysis, and is required to avoid tight, effectively irreversible, binding of the substrate/product.2

Scheme 1.

OMPDC-Catalyzed Decarboxylation of OMP or EO to Form UMP or EU, Respectively, through Vinyl Carbanion Reaction Intermediates.

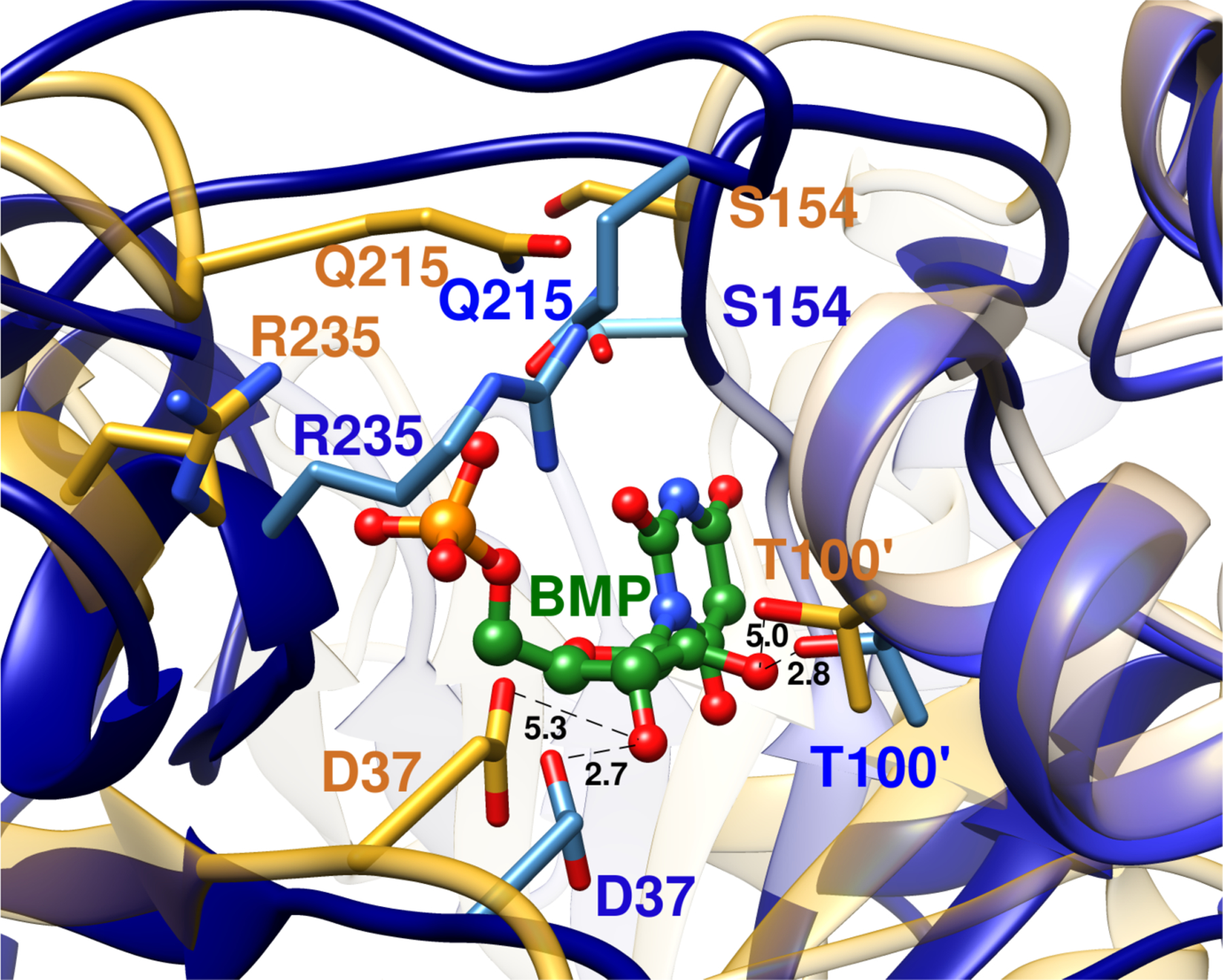

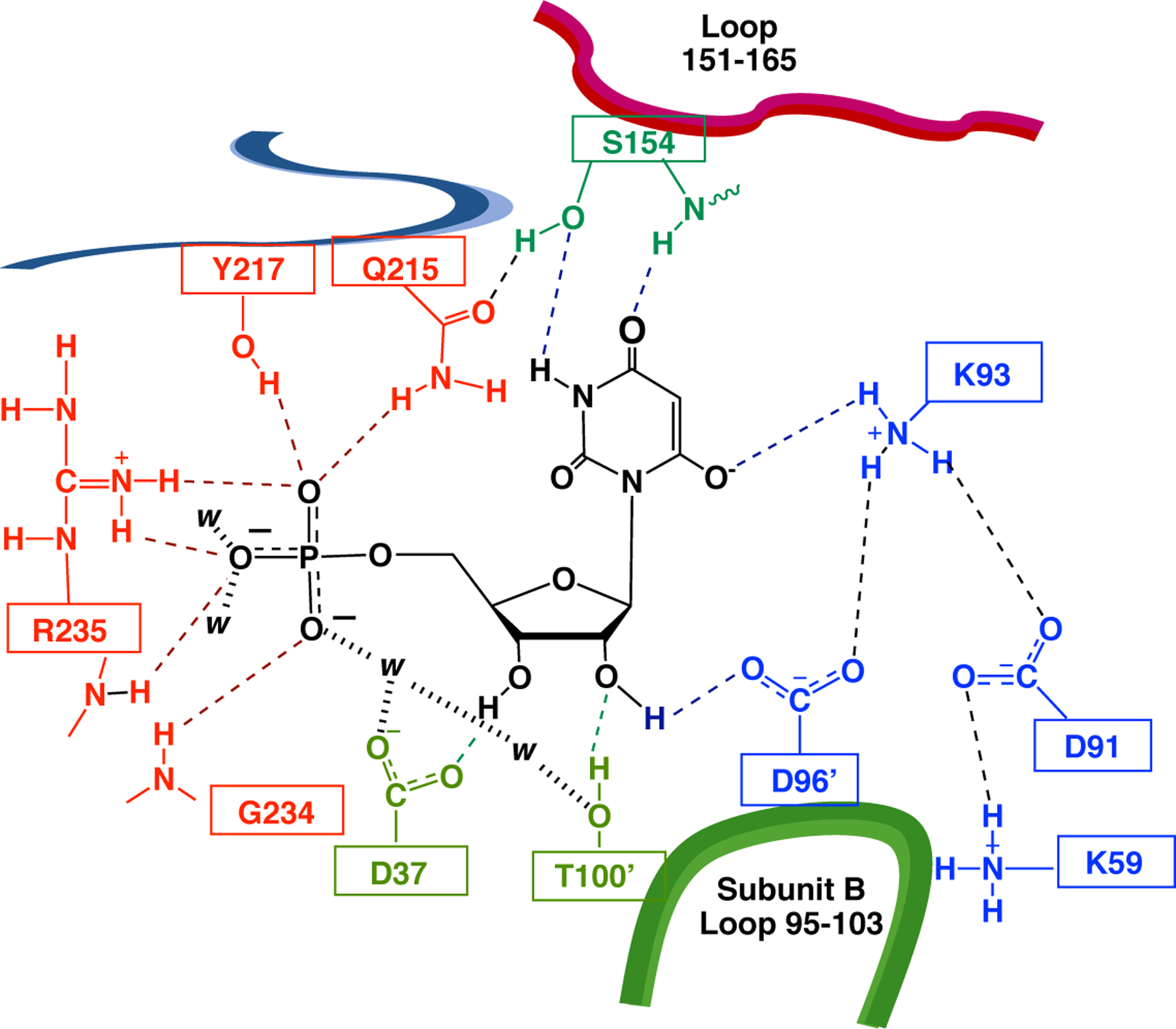

The small fraction of the total ligand binding energy expressed at the Michaelis complex for OMP reflects partly or entirely the large ligand binding energy utilized to drive a complex enzyme conformational change of the flexible open form of OMPDC to a stiff, catalytically active, protein that provides strong stabilization of the decarboxylation transition state.8 Many of the details of this conformational change were revealed in a comparison of the X-ray crystal structure for unliganded yeast OMPDC, with structures for complexes to the intermediate analogs 6-hydroxyuridine 5’-monophosphate (BMP, Figure 1)9 and 6-aza uridine 5’-monophosphate (azaUMP).10 Figure 1 illustrates the following for the protein-BMP complex: (1) The closure of a phosphodianion gripper loop (P202–V220) and a pyrimidine umbrella loop (A151–T165) over the respective phosphodianion and pyrimidine substrate fragments. (2) Stabilization of the closed enzyme by a hydrogen bond between the S154 and Q215 side chains. (3) Movement of the D37 and T100’ protein side chains into position to form hydrogen bonds to the substrate ribosyl hydroxyl groups. (4) The intra-subunit motion of an α-helix (G98’–S106’) towards the substrate ribosyl ring bound at the main subunit.

Figure 1.

Superposition of representations of the X-ray crystal structure of the unliganded open form of yeast OMPDC (gold, PDB 1DQW) and of the closed enzyme (blue, PDB 1DQX) complexed to the tight binding inhibitor 6-hydroxyuridine 5’-monophosphate (BMP, green). The inhibitor complex is stabilized by movement of Q215 and R235 side chains towards the ligand phosphodianion, and of the S154 side chain at a pyrimidine umbrella loop into a position to hydrogen bond to the Q215 side chain. The D37 and T100’ side chains are shown in gold for unliganded OMPDC. They are an estimated 5.3 Å and 5.0 Å, respectively, from the C-3’-OH and C-2’-OH ribosyl-OH at the hypothetical BMP ligand, which is superimposed with BMP bound to the closed enzyme. The D37 and T100’ side chains are shown in blue for the closed BMP complex. They lie 2.7 Å and 2.8 Å, respectively, from the C-3’-OH and C-2’-OH groups of the ligand.

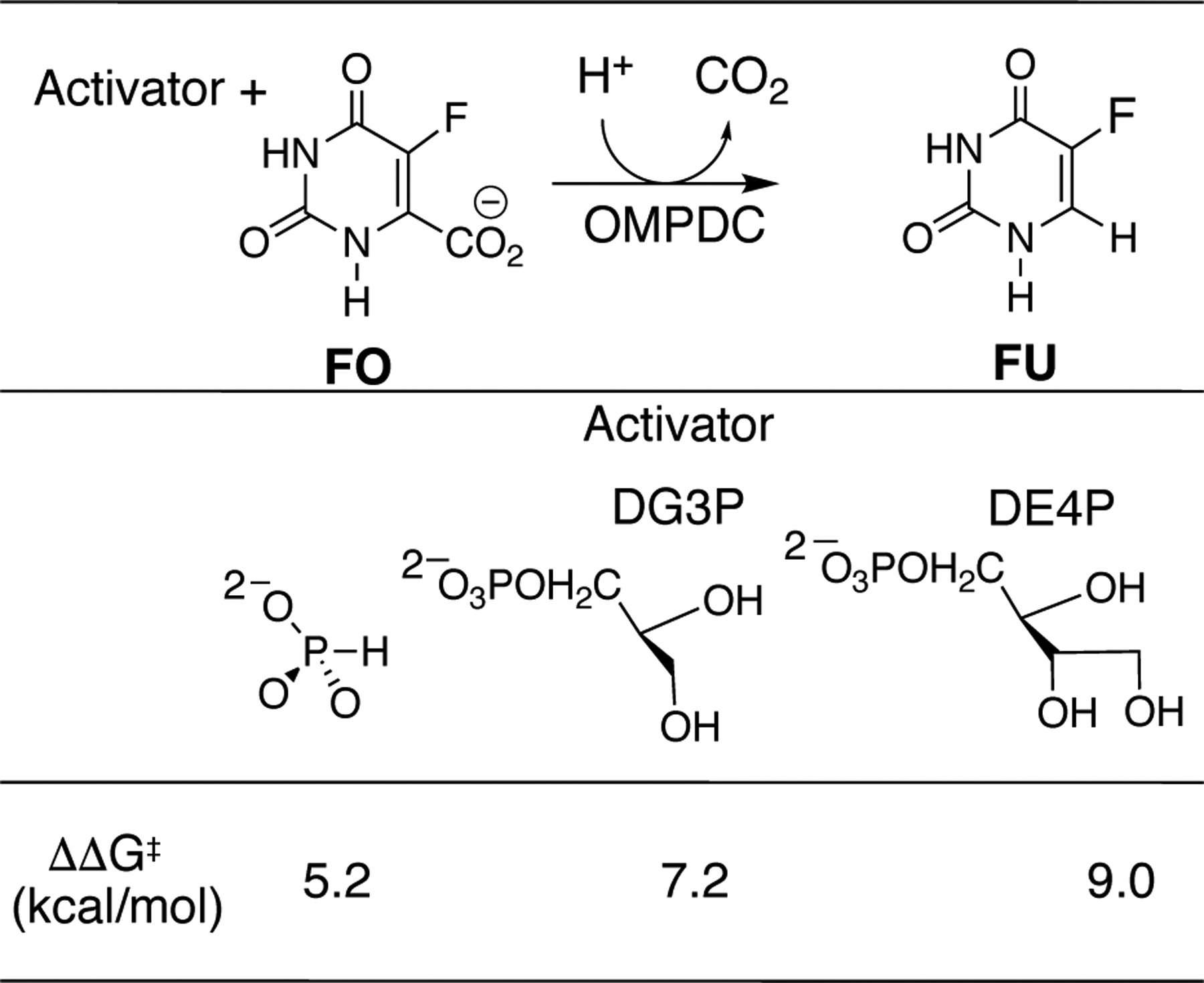

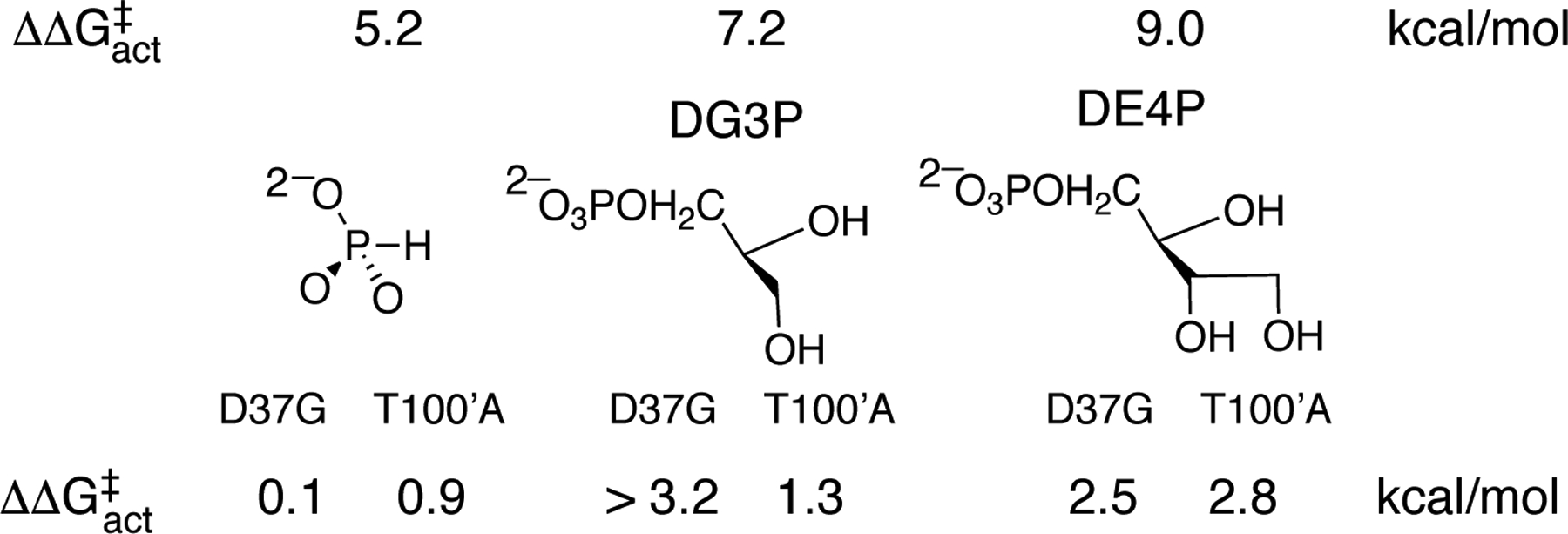

This manuscript will focus on the hypothesis that protein motions, which produce contacts between the D37 and T100’ side chains and the OMP hydroxyl groups, activate OMPDC for catalysis of decarboxylation at the orotate ring.8 The transition state for OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of the phosphoribofuranosyl truncated fragment 5-fluoroorotate (FO) is stabilized by 5.2, 7.2 and 9.0 kcal/mol, respectively, by 1.0 M phosphite dianion, d-glycerol 3-phosphate dianion (DG3P) and d-erythritol 4-phosphate dianion (DE4P) (Chart 1).11 These results show: (i) Phosphite dianion provides strong activation of OMPDC for catalysis of decarboxylation of both the phosphodianion truncated substrate (1-β-D-erythrofuranosyl)orotate (EO) and the phosphoribofuranosyl truncated substrate FO. (ii) Interactions with activator hydroxyls at positions sterically equivalent to the C-2’ and C-3’ hydroxyls of OMP stabilize the transition state for OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of FO by ca 2 kcal/mol/hydroxyl.11

Chart 1.

Stabilization (ΔΔG‡) of the Transition States for OMPDC-Catalyzed Decarboxylation of the Phosphoribofuranosyl Truncated Substrate 5-Fluoroorotate (FO).

The D37 and T100’ side chains lie ca 5 Å from the C-3’ and C-2’ ribosyl-OH, respectively, at the hypothetical complex of the intermediate analog BMP bound to the open form of OMPDC (Figure 1). The side chains move >2 Å upon substrate binding, and form contacts to ribosyl -OH groups that stabilize the active closed enzyme relative to the inactive open form. We report here the results of experiments designed to establish whether protein motion that positions the D37 and T100’ side chains of OMPDC to interact with the ribosyl hydroxyls of OMP play a role in enzyme activation similar to that documented for motion of phosphodianion gripper side chains towards bound dianion.12, 13 We previously reported the effect of D37G/A and T100’G/A substitutions on the kinetic parameters for OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of OMP and FOMP, and on the stability of the active enzyme dimer relative to the inactive monomer.14 We report here the results of experiments to determine the contribution of these side-chain interactions to stabilization of the transition states for the unactivated and small sugar dianion-activated decarboxylation reactions of truncated substrates EO and FO.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials.

The trisodium salt of orotidine 5’-monophosphate (OMP) was prepared by modification of a published enzymatic methods,15 from orotate and phosphoribosylpyrophosphate.16, 17 1-(β-D-erythrofuranosyl)orotate (EO) and 1-(β-D-erythrofuranosyl)uridine (EU) were prepared by published procedures.18 Uridine (99%), 5-fluoroorotic acid (FO, 98%), 5-fluorouracil (FU, ≥ 99%), 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (MOPS, ≥ 99.5%), d-erythritol 4-phosphate (DE4P, lithium salt, ≥ 95%), the lithium salt of l-glycerol 3-phosphate (LG3P, ≥ 95%) and the sodium salt of d,l-glycerol 3-phosphate (DLG3P, ≥ 95%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Formic acid (88% solution), sodium hydroxide (1.0 N), hydrochloric acid (1.0 N), sodium chloride and Amicon® centrifugal filters with 10-kDa molecular weight cutoff were purchased from Fisher. Ammonium acetate (HPLC grade) was purchased from Fluka. Sodium phosphite pentahydrate (Na2HPO3•5H2O) was purchased from Riedel-de Haën. Water was purified using a Milli-Q Academic purification system. All other chemicals were reagent grade or better and were used without further purification. The procedures for the preparation, overexpression and purification of T100’A and D37G variants of orotidine 5’-monophosphate decarboxylase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae were described in an earlier publication.14

Preparation of Solutions.

Solution pH was determined at 25 °C using an Orion Model 720A pH meter equipped with a Radiometer pHC4006–9 combination electrode that was standardized at pH 4.00, 7.00 and 10.00 at 25 °C. Stock solutions of sodium phosphite (pKa = 6.4,19 100 mM, 80% dianion), DE4P (100 mM, 90% dianion)11, LG3P (100 mM, 90% dianion)11 and DLG3P (100 mM, 90% dianion)11 were prepared at pH 7.0 by dissolving the salt in water and adjusting the pH to 7.0. MOPS buffers at pH 7.0 were prepared by addition of measured amounts of 1.0 N NaOH and solid NaCl to give the desired acid/base ratio and ionic strength. A stock solution of ammonium acetate was prepared by dissolving the salt in water and adjusting the pH to 4.2.

Stock solutions of OMP (20 mM) and the HPLC standards uridine, FU and EU were prepared by dissolving the solids in water, and adjusting the solution to the desired pH. The stock solution of EO (20–30 mM) was prepared by dissolving the free acid in water, and adjusting to pH ≈ 6–7 using 1.0 N NaOH. The stock solution of FO (ca 50 mM) was prepared by dissolving the free acid in water, passing this solution through a 0.45 μM sterile filter syringe and adjusting the pH to ≈7.0 using 1.0 N NaOH. The stock solutions of OMP, EO and FO were stored at − 20 °C prior to use. The concentrations of stock solutions of substrates or decarboxylation reaction products in 0.10 M HCl were determined from the absorbance at λmax and using the following extinction coefficients: OMP, λmax = 267 nm and ε = 9430 M−1 cm−1;20 EO, λmax = 267 nm and ε = 9570 M−1 cm−1;13 FO, λmax = 285 nm and ε = 7070 M−1 cm−1;21 uridine, λmax = 262 nm and ε = 10100 M−1 cm−1 and FU, λmax = 265 nm and ε = 7100 M−1 cm−1.21

Stock solutions of T100’A and D37G OMPDC were dialyzed against the MOPS buffer used in the particular experiment. The concentration of variant OMPDC in these stock solutions was determined from the absorbance at 280 nm using an extinction coefficient of 29 900 M−1 cm−1, that was calculated using the ProtParam tool available on the ExPASy server.22,23 The decarboxylation of OMP was monitored, in standard enzyme assays, by following the decrease in absorbance at 279 nm.24

Kinetic Studies.

These studies were at 25 °C and pH 7.0, in solutions that contain 10 mM or 25 mM MOPS buffer. The more rapid reactions were monitored using either a temperature-controlled Cary 3500 Multicell Peltier UV-Vis spectrophotometer or a Cary 3E spectrophotometer equipped with a temperature-controlled Peltier block multicell changer. The nonlinear least squares fit of plots of kinetic data to the appropriate kinetic equations were obtained using Prism 8 for MacOS from GraphPad Software.

Decarboxylation of EO catalyzed by T100’ and D37 variants of OMPDC.

The unactivated decarboxylation of EO, and the reactions activated by 0.5 or 1 mM phosphite dianion were monitored in 200-μL solutions that contained 25 mM MOPS at pH 7.0 (I = 0.14, NaCl), 5–6 mM EO and 0.0045–0.34 mM of the D37G or T100’A variant enzyme. At measured reaction times 20 μL aliquots were withdrawn and the enzyme was quenched by mixing with 180 μL of 2.6 mM formic acid water, which contained 40 μM of the internal standard 5-fluorouracil (FU). The enzyme was removed by ultrafiltration through an Amicon Ultra device (10K molecular weight cutoff) that had been washed 2 to 3 times with 400 μL of water.

The reactions were followed for up to ten hours, during which time ≥ 2% of EO was consumed. Periodic assays showed the enzyme maintained full (>95%) activity during this time. The relative concentrations of reactant EO and product EU present in the resulting filtrate were determined by HPLC analyses, as described in earlier work.18, 24 Initial reaction velocities (vo, M s−1) were determined as the slopes of linear plots of [EU]t against time over the first ca 2% reaction. The observed second-order rate constants (kcat/Km)obs (M−1 s−1) were determined using eq 1.

| (1) |

The phosphite-dianion activated OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of EO was monitored in 1.0 mL solutions that contain 25 mM MOPS at pH 7.0 (I = 0.14, NaCl), either 0.144 mM EO (D37G) or 0.185 mM EO (T100’A), and the following range of concentrations of enzyme and phosphite dianion: T100’A OMPDC, 17–28 μM enzyme and 2–14 mM HPO32−; D37G OMPDC, 15 μM enzyme and 2–10 mM HPO32−. The reactions were initiated by addition of variant OMPDC. The initial reaction velocity vo was determined by monitoring the decrease in absorbance at 279 nm (Δε = −3370 M−1 cm−1) for reactions at [EO] = 0.144 mM or 0.185 mM, over the first 5% reaction. Observed second-order rate constants (kcat/Km)obs (M−1 s−1) for variant-catalyzed decarboxylation were determined using eq 1.

OMPDC-Catalyzed Decarboxylation of FO.

The decarboxylation of FO catalyzed by T100’A and D37G variants of OMPDC was followed by monitoring formation of the product FU in HPLC analyses. Reaction solutions were prepared in a volume of 0.50 mL to contain: 10 mM MOPS at pH 7.0, 5 mM or 10 mM FO, and 0.6–0.9 mM T100’A variant or 0.75–1.0 mM D37G variant OMPDC at I = 0.15 (NaCl). The reactions at 25 °C were monitored for up to 20 days during which time ≤ 0.07% of FO was converted to product FU. The enzyme-activity for catalysis of decarboxylation of OMP was monitored during these reactions, and no significant decrease (≤ 10%) was observed, except for the unactivated reactions of D37G OMPDC, where after seven days there is a >95% decrease in activity.

Reactions in the presence of dianion activators were in 0.50 mL solutions that contained 10 mM MOPS at pH 7.0 and I = 0.15 (NaCl), 5 mM FO and the specified concentrations of dianion activator and variant OMPDC. (1) DE4P (2.5–20 mM) and 0.15 mM T100’A OMPDC or 0.2 mM D37G variant OMPDC. The reactions were followed for 6 days by HPLC analyses during which time up to 0.80% of FO was converted to FU. (2) DLG3P (5–40 mM) and 0.17 mM T100’A variant OMPDC. The reactions were followed for 6 days, during which time up to 0.5% of FO was converted to product FU. (3) Phosphite dianion (2.5–40 mM) and 0.55–0.75 mM T100’A or 0.6–0.8 mM D37G variant OMPDC. The reactions were followed for 6 days, during which time up to 0.2% of FO was converted to product FU. (4) LG3P dianion (5–40 mM) and 0.3 mM T100’A variant OMPDC. The reactions were followed for 5 days, during which time up to 0.2% of FO was converted to product FU. The enzyme-activity was monitored during these reactions, and no significant decrease in activity (≤ 10%) was observed.

HPLC product analysis.

At measured times, 50 μL aliquots were withdrawn from the 0.50 mL solution, and the reaction quenched by mixing with 100 μL or 150 μL of 2.5 mM formic acid in water that contained 10–20 μM of the internal standard uridine. The protein catalyst was removed by ultrafiltration using an Amicon filter unit (10-kDa molecular weight cutoff) that had been prewashed 3–4 times with 400 μL of water. The resulting filtrate was analyzed by HPLC using a Waters Atlantis ΔC18 3 μm (3.9 × 150 mM) with isocratic elution by 10 mM NH4OAc at pH 4.2 for ca. 12 min, with a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min and peak detection at 265 nm.11 The peak areas determined for the FU product were normalized using the observed peak area for the uridine internal standard, and the peak area for uridine determined by direct HPLC analysis of the formic acid/uridine quench solution prior to filtration. This was necessary to correct for a small variable dilution of the sample during its passage through the prewashed filtration device. The concentration of the product FU in the reaction mixture at a given reaction time, [FU]t, was obtained from the normalized product peak area (Anor), by interpolation of a standard curve of peak area against [FU] that was constructed for a standard solution of FU. Initial reaction velocities for variant OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of FO (vo, M s−1) were determined as the slopes of linear plots of [FU]t against time over the first ≤ 2% reaction. Observed second-order rate constants (kcat/Km)obs (M−1 s−1) for the enzymatic reaction were determined using eq 1.

RESULTS

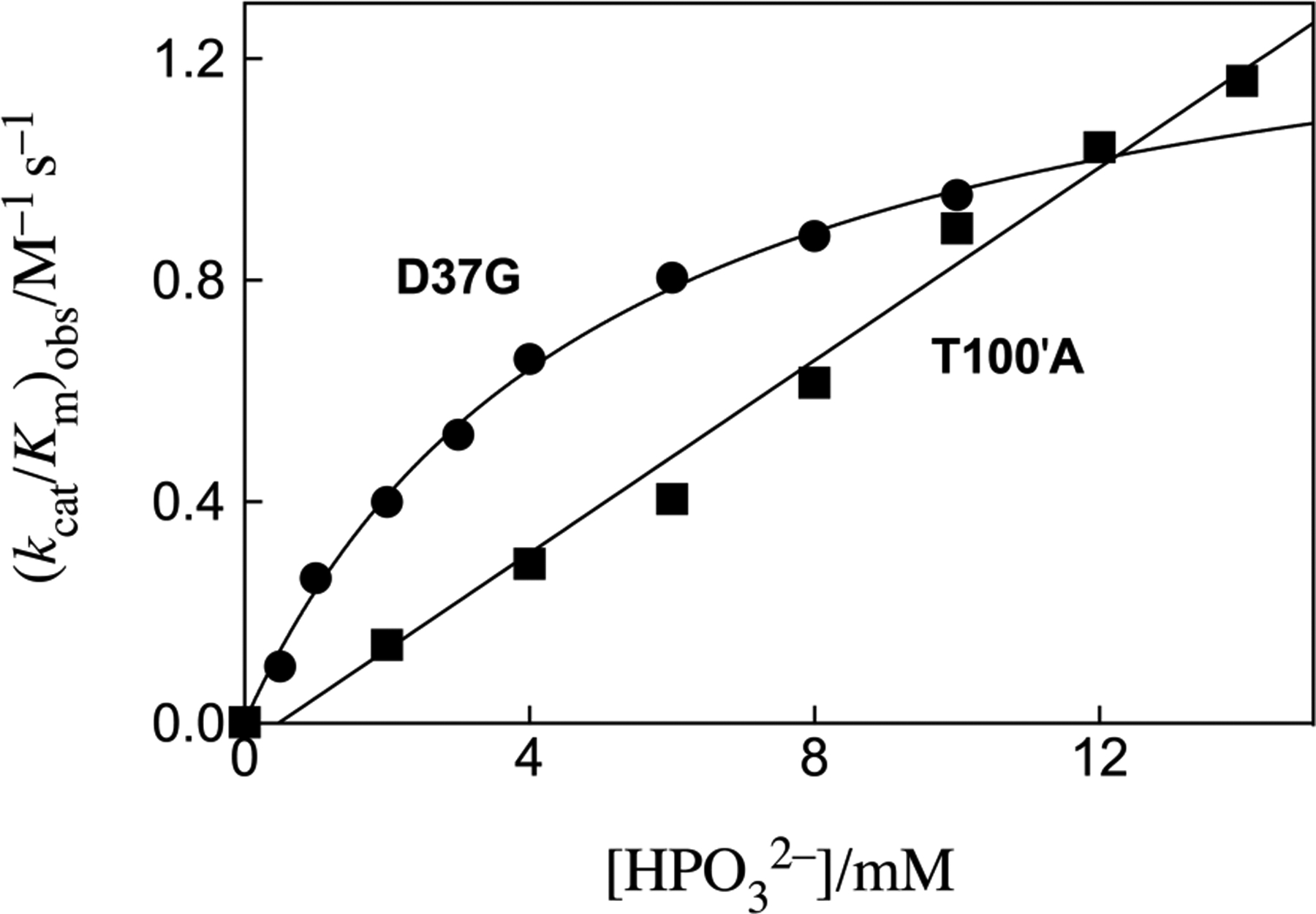

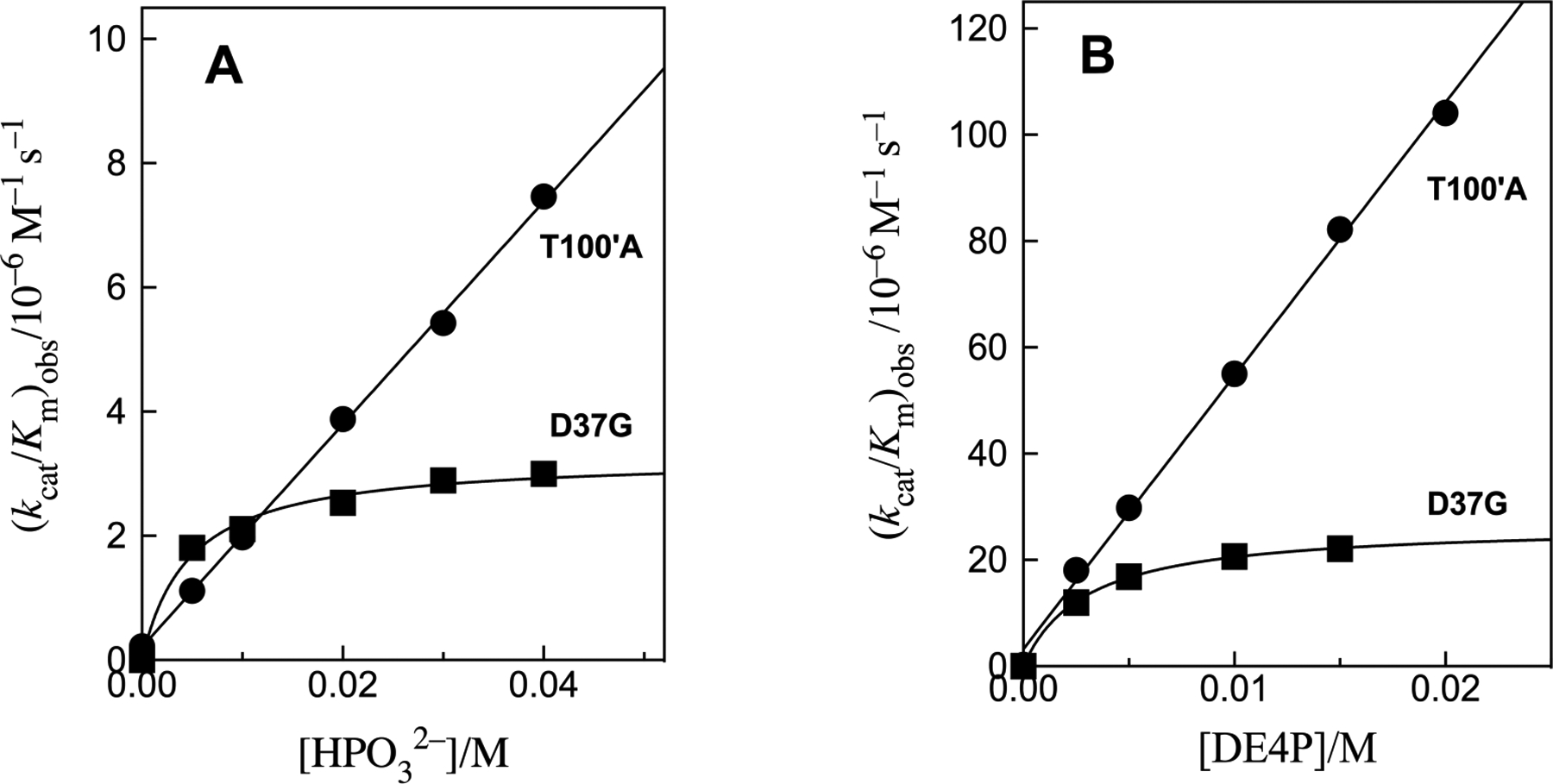

The unactivated variant OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of the phosphodianion truncated substrate EO, and the reactions activated by 0.5 and 1 mM phosphite dianion were followed at 25 °C using a discontinuous HPLC assay to monitor formation of product EU.18, 24 The phosphite dianion activated reactions at > 1 mM phosphite were monitored by UV spectroscopy. Figure S1 and S2 from the Supporting Information (SI) show representative HPLC chromatograms obtained while monitoring the unactivated decarboxylation of EO to form EU for reactions catalyzed, respectively, by the T100’A and D37G variants. Figure S3 shows the increase in [EU]/[E][EO]o with time for these variant-catalyzed decarboxylation reactions. The slopes of these linear correlations are equal to the values of (kcat/Km)E reported in Table 1. Figure 2 shows the dependence of apparent second-order rate constants (kcat/Km)obs for decarboxylation of EO catalyzed by the T100’A and D37G variants of OMPDC on the concentration of [HPO32−] (Scheme 2), where the values of (kcat/Km)obs were determined from the initial velocity (vo) using eq 1. The slope of the linear correlation of data for reactions catalyzed by the T100’A variant is equal to the third order rate constant (kcat/Km)E•HPi/Kd = 85 M−2 s−1 (Scheme 2, Kd ≫ [HPO32−]). The nonlinear least-squares fit of data for D37G variant-catalyzed decarboxylation of EO to eq 2 (Scheme 2, (kcat/Km)E•HPi ≫ (kcat/Km)E) gave values of (kcat/Km)E•HPi = 1.5 M−1 s−1, Kd = 5.1 mM and (kcat/Km)E•HPi/Kd = 290 M−2 s−1 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Kinetic Parameters for Wild Type and Variant OMPDC-Catalyzed Decarboxylation of OMP and EO at 25 °C.

| Enzyme | OMPa | EOb | EO + HPib | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔΔG‡ (kcal/mol)d |

ΔΔG‡ (kcal/mol)d |

ΔΔG‡ (kcal/mol)d |

||||

| WT | 1.1 × 107 | 0.026e | 1.2 × 104 e | |||

| D37G | 3.2 × 105 | 2.1 | (2.7 ± 0.1) × 10−3 f | 1.4 | 290 g | 2.2 |

| T100’A | 2.1 × 105 | 2.3 | (2.3 ± 0.1) × 10−3 f | 1.4 | 85 g | 2.9 |

At pH 7.1 (30 mM MOPS) and I = 0.105 (NaCl).

Rate constant defined in Scheme 2.

Published kinetic parameters.14

The effect of the side chain substitution on the activation barrier for the reaction catalyzed by wild type OMPDC.

Published kinetic parameter.18

Average of two determinations at pH 7.0 (25 mM MOPS) and I = 0.14 (NaCl).

Figure 2.

The effect of increasing concentrations of phosphite dianion on (kcat/Km)obs for decarboxylation of EO catalyzed by variants of OMPDC at pH 7.0, 25 °C and I = 0.14 (NaCl). The solid lines show the fits of the experimental data to eq 2, where Kd ≫ [HPO32−] for dianion activation of the T100’A variant.

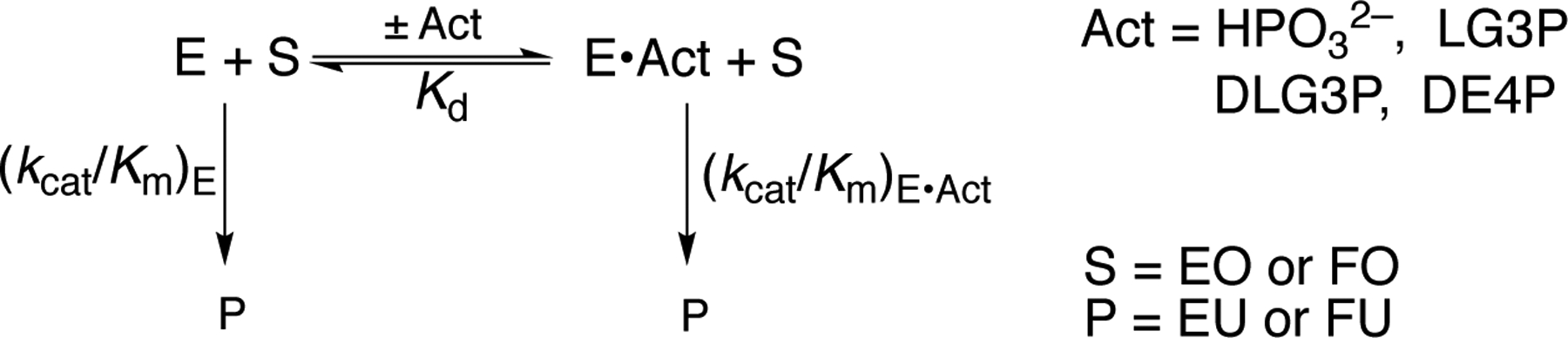

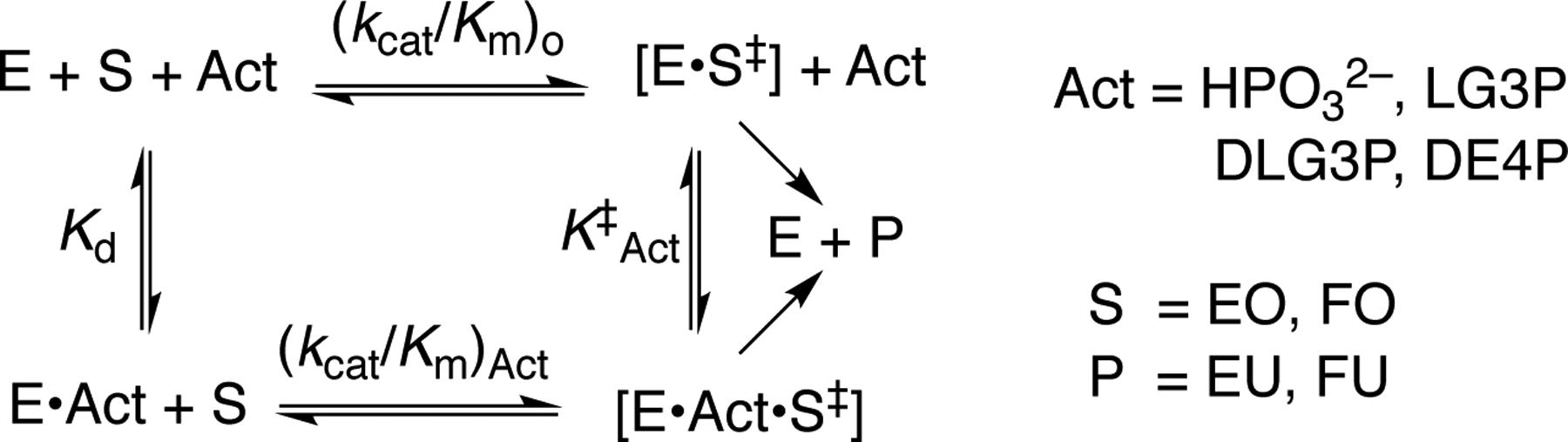

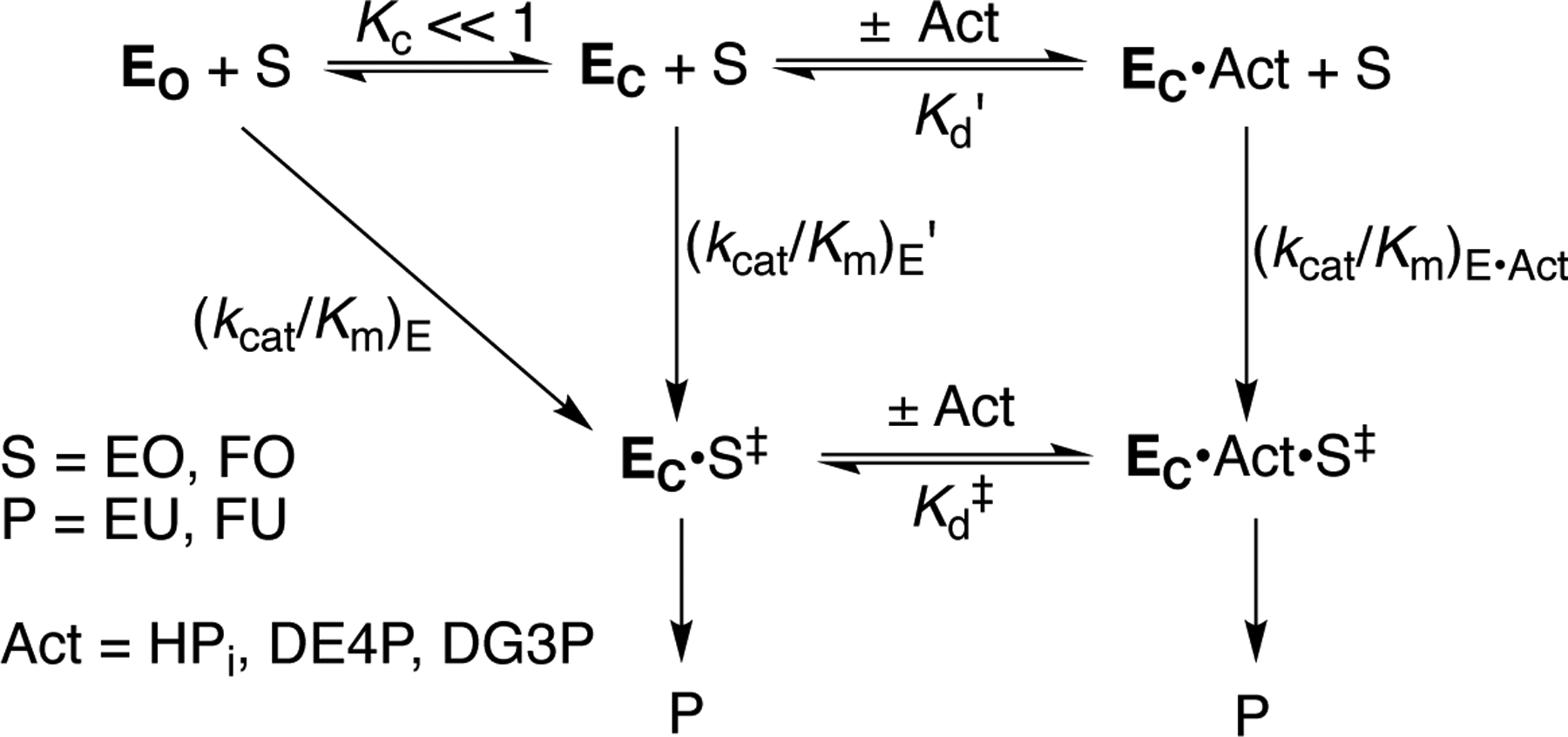

Scheme 2.

The Reactions of Substrate Fragments EO and FO Catalyzed by OMPDC in the Absence or Presence of Dianion Activators (Act).

The formation of FU from FO in decarboxylation reactions catalyzed by D37G and T100’A variants of OMPDC was monitored by HPLC, following the protocol developed to monitor the wild type OMPDC-catalyzed reaction.11 Representative chromatograms from HPLC analyses of the products of the unactivated decarboxylation of FO catalyzed by the T100’A variant of OMPDC are shown in Figure S4 of the SI. This enzyme-catalyzed decarboxylation reaction of FO (ca.0.9 mM) was followed for up to 0.07% reaction over a period of 20 days, during which time the enzyme maintained > 90% of the initial activity. It was not possible to obtain kinetic parameters for unactivated D37G variant-catalyzed decarboxylation of FO because this variant (ca. 0.9 mM) precipitates from solution and loses ca. 95% of its catalytic activity towards decarboxylation of OMP over a period of seven days.

| (2) |

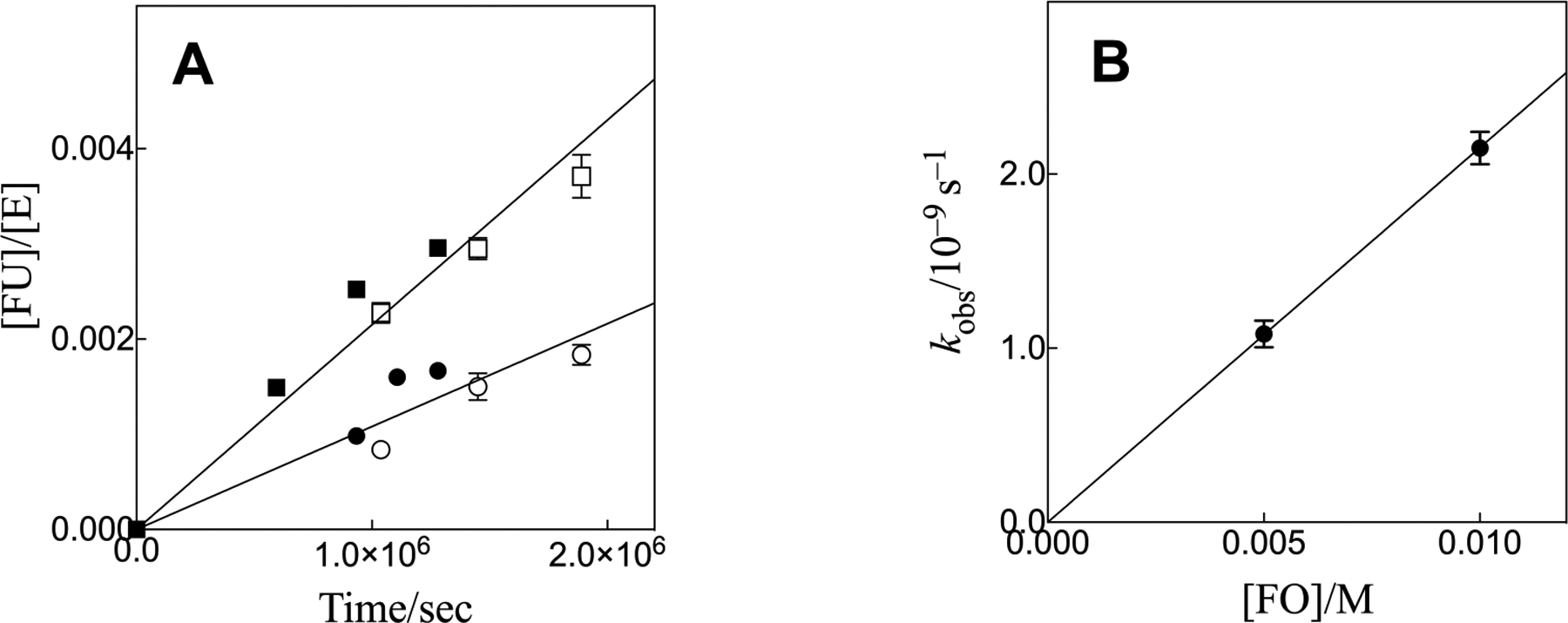

Figure 3A shows the increase in [FU]/[E] against time for T100’A variant OMPDC-catalyzed reactions of [FO]o = 5 mM [●, ○] and [FO]o = 10 mM [■, □], where the open and closed symbols show data from separate experiments carried out with different preparations of the enzyme. The error bars for the open symbols show the range of values of [FU]/[E] obtained for replicate determinations. The slopes of these linear correlations are vo/[E] = kobs. Figure 3B shows the increase in kobs with increasing [FO] determined from the slopes of the linear correlations from Figure 3A. The error bars for Figure 3B show the uncertainty in the values of k obs estimated as the standard deviation for the linear least-squares slopes determined for Figure 3A. The slope of the linear correlation from Figure 3B is equal to the value of (kcat/Km)E (Scheme 2) for the T100’A variant-catalyzed decarboxylation of FO reported in Table 2.

Figure 3.

(A) The increase in [FU]/[E] against time for T100’A variant OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation reaction of FO at pH 7.0 (10 mM MOPS), 25 °C and I = 0.15 (NaCl). The slopes of these linear correlations are equal to kobs for enzyme-catalyzed decarboxylation. Key: (●), 5 mM FO and (■), 10 mM FO. The open and closed symbols show results from separate experiments. (B) The increase in kobs with increasing concentrations of FO, with slope equal to (kcat/Km)E (Scheme 2) for variant-catalyzed decarboxylation of FO.

Table 2.

Kinetic Parameters for Activation of Wild Type and Variant OMPDC-Catalyzed Decarboxylation of FO.a,b

| Activator | Kinetic Parameter | OMPDC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild Typec | T100’A | D37G | ||

| None |

kcat/Km M−1 s−1 |

1.4 × 10−7 | (2.2 ± 0.04) × 10−7 d | Enzyme is unstable |

| HPO32− |

Kd M |

0.18 | Kd >> [HPO32−]e | (4.7 ± 0.8) × 10−3 |

| (kcat/Km)E•Act M−1 s−1 | 1.6 × 10−4 | (3.3 ± 0.1) × 10−6 | ||

| (kcat/Km)E•Act/Kd M−2 s−1 | 8.4 × 10−4 | (1.87 ± 0.03) × 10−4 | (7.0 ± 1.2) × 10−4 | |

| DLG3P |

Kd M |

0.05 | 0.094 ± 0.008 |

kcat/KmKActg < 5 × 10−5 M−2 s−1 |

| (kcat/Km)E•Act M−1 s−1 | 7.0 × 10−4 | (1.6 ± 0.1) × 10−4 | ||

| (kcat/Km)E•Act/Kd M−2 s−1 | 1.3 × 10−2 | (1.7 ± 0.2) × 10−3 | ||

| DG3P | (kcat/Km)E•Act/Kd M−2 s−1 | 2.5 × 10−2 | (2.9 ± 0.3) × 10−3 f | |

| LG3P |

Kd M |

Kd >> [LG3P] | Kd >> [LG3P]e |

kcat/KmKActg < 5 × 10−5 M−2 s−1 |

| (kcat/Km)E•Act M−1 s−1 | ||||

| (kcat/Km)E•Act/Kd M−2 s−1 | 1.0 × 10−3 | (5.3 ± 0.2) × 10−4 | ||

| DE4P |

Kd M |

0.03 | Kd >> (kcat/Km)E•Acte | (3.0 ± 0.1) × 10−3 |

| (kcat/Km)E•Act M−1 s−1 | 1.9 × 10−2 | (2.67 ± 0.03) × 10−5 | ||

| (kcat/Km)E•Act/Kd M−2 s−1 | 6.0 × 10−1 | (5.4 ± 0.1) × 10−3 | (8.9 ± 0.3) × 10−3 | |

For decarboxylation reactions at pH 7.0, 25 °C and I = 0.15 (NaCl).

Rate constants defined in Scheme 2.

Published kinetic parameters.11

The quoted uncertainty in this rate constant is for the calculated slope of the least squares line from Figure 3B. The actual uncertainty is closer to ± 20%, the uncertainty in the product yields from HPLC analyses (Figure 3A).

It was not possible to determine separate values for Kd and (kcat/Km)E•Act from linear plots of (kcat/Km)obs against [Act] (Figures 5A, 5B and 6B).

Calculated from the values of (kAct)DLG3P and (kAct)LG3P using eq 3 from the text.

No reaction was detected; the upper limit for this rate constant is defined by the estimated smallest second-order rate constant detectable in our experiments, (kcat/Km)obs = 1.8 × 10−6 M−1 s−1, and an activator concentration of 0.040 M.

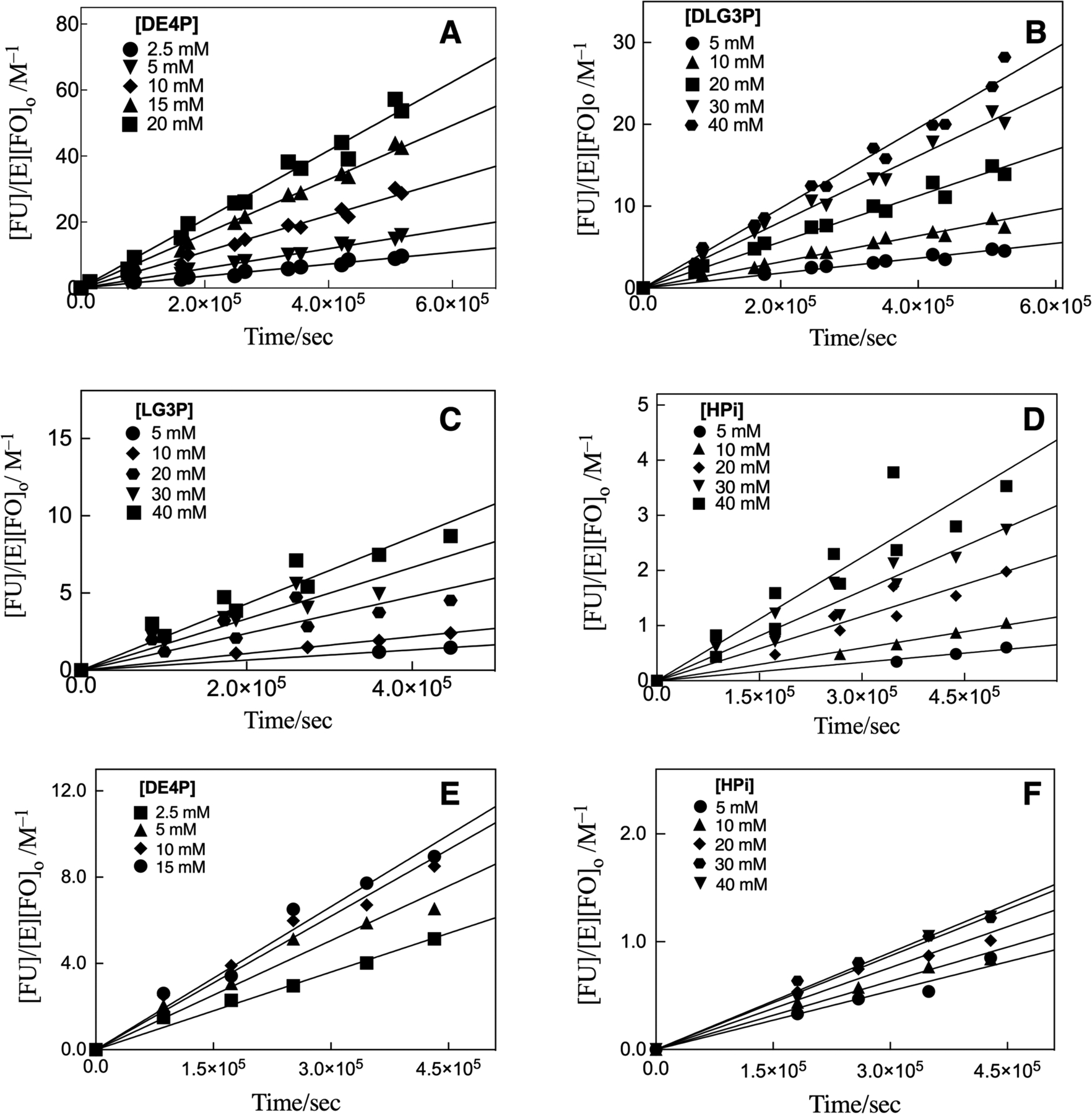

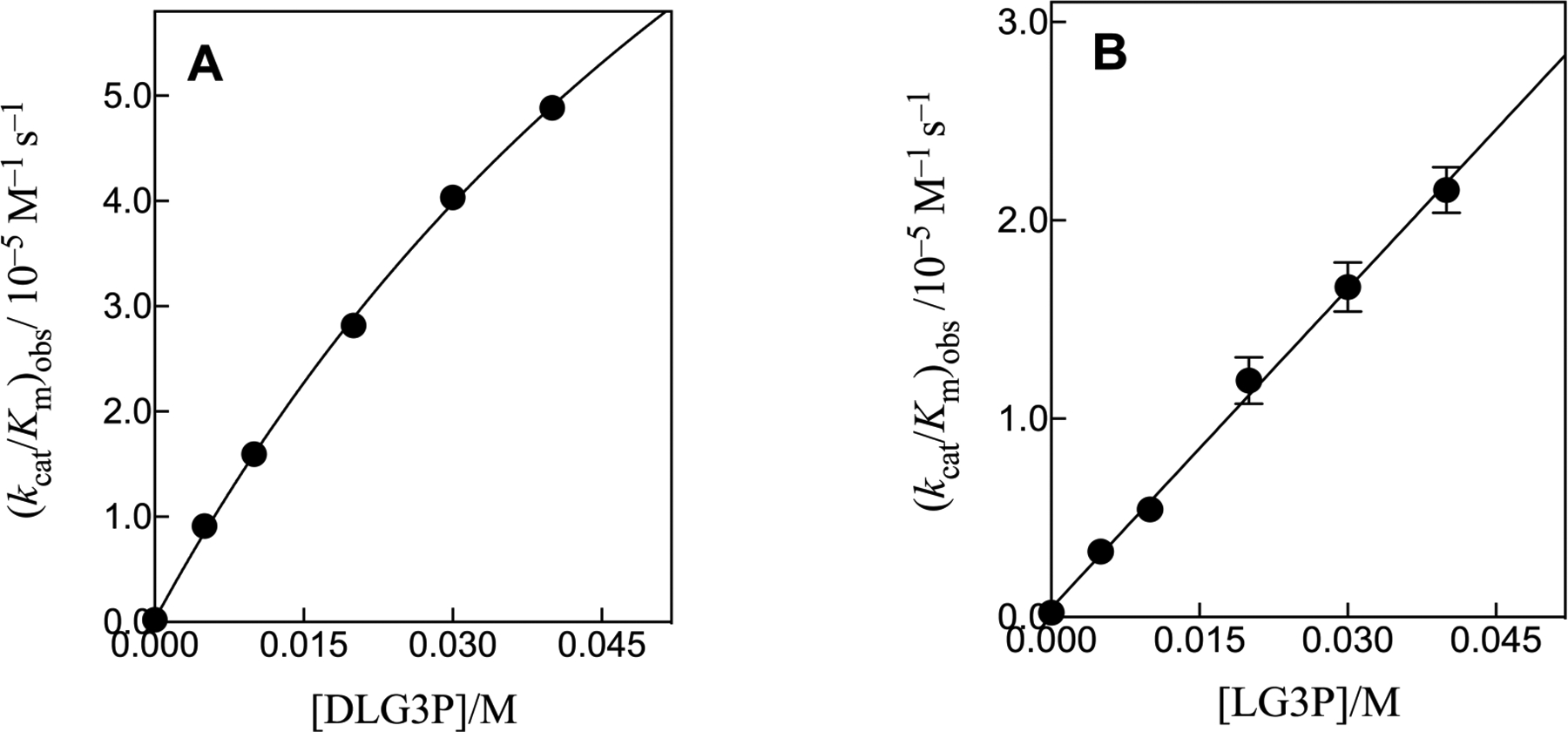

Representative chromatograms from HPLC analyses of the products of d-erythritol 4-phosphate dianion (DE4P)-activated decarboxylation of FO catalyzed by the T100’A variant of OMPDC are shown in Figure S5 of the SI. Figures 4A–4D show the increase in [FU]/[E][FO]o with time for T100’A variant-catalyzed decarboxylation of FO in the presence of increasing concentrations of dianion activators: D-erythritol 4-phosphate dianion (DE4P), Figure 4A; a racemic mixture of d- and l-glycerol 3-phosphate (DLG3P), Figure 4B; l-glycerol 3-phosphate (LG3P), Figure 4C; and, phosphite dianion, (Figure 4D). The slopes of linear correlations from Figure 4 are equal to the second-order rate constants (kcat/Km)obs for the variant-catalyzed reactions at the specified concentration of activator.

Figure 4.

The effect of increasing concentrations of activator dianion on T100’A (Figure 4A–4D) and D37G (Figure 4E–4F) variant OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of FO ([FO]o = 5 mM) to form product FU for reactions at 25 °C, pH 7.0 (10 mM MOPS) at I = 0.15 (NaCl). The slopes of these linear correlations are equal to (kcat/Km)obs (M−1 s−1) for variant-catalyzed decarboxylation at the specified concentration of activator.

The D37 variant maintained >90% of enzyme activity during five day reactions of FO in the presence of DE4P, DLG3P, LG3P and phosphite dianion activators. Figures 4E and 4F show the increase in [FU]/[E][FO]o with time for D37G variant-catalyzed reactions in the presence of increasing [DE4P] (Figure 4E) and [HPO32−] (Figure 4F) activators. The slopes of these linear correlations are equal to the second-order rate constants (kcat/Km)obs for the D37G variant-catalyzed reactions at the specified concentration of activator.

Figure 5 shows the increase in (kcat/Km)obs, with increasing [HPO32−] (Figure 5A) or [DE4P] (Figure 5B) activators for decarboxylation of FO catalyzed by D37G and T100’A variants of OMPDC. Figure 6 shows the increase in (kcat/Km)obs for decarboxylation of FO catalyzed by the T100’A variant in the presence of increasing concentrations of racemic DLG3P (Figure 6A) or LG3P (Figure 6B). The solid lines in Figures 5 and 6 show the least-squares fit of data to eq 2, where (kcat/Km)E•HPi ≫ (kcat/Km)E. The slopes of the linear correlations (Kd ≫ [Act]) are equal to the values of (kcat/Km)E•Act/Kd reported in Table 2. In cases where curvature is observed, the values of (kcat/Km)E•Act and Kd obtained from the fit of the data are also reported. There is good agreement between the values of Kd = 5.1 mM and 4.7 mM, respectively, determined for phosphite dianion activation of D37G variant-catalyzed decarboxylation of EO and FO.

Figure 5.

The increase in (kcat/Km)obs at increasing concentrations of dianion activators for decarboxylation of FO catalyzed by D37G and T100’A variants of OMPDC at pH 7.0, 25 °C and I = 0.15 (NaCl). (A) Activation by phosphite dianion. (B) Activation by DE4P dianion.

Figure 6.

The increase in (kcat/Km)obs at increasing concentrations of dianion activators for decarboxylation of FO catalyzed by the T100’A variant of OMPDC at pH 7.0, 25 °C and I = 0.15 (NaCl). (A) Activation by DLG3P dianion. (B) Activation by LG3P dianion.

We were not able to obtain enantiomerically pure DG3P. This has the same configuration as the C-3 ribosyl carbon of OMP, where the C-3 hydroxyl group is positioned at OMPDC to interact with the D37 side chain (Figure 1). The value of (kcat/Km)E•Act/Kd = (1.7 ± 0.2) × 10−3 M−2 s−1 for activation of T100’A variant-catalyzed decarboxylation of FO by racemic DLG3P is significantly larger than (kcat/Km)E•Act/Kd = (5.3 ± 0.2) × 10−4 M−2 s−1 determined for activation by LG3P (Table 2). This shows that the DG3P is more reactive as an activator than LG3P, presumably because of the interaction with the D37 side chain. The value of (kcat/Km)E•Act/Kd = (2.9 ± 0.3) × 10−3 M−2 s−1 for DG3P-activated decarboxylation of FO catalyzed by the T100’A variant (Table 2) was calculated from the kinetic parameters for activation by the racemic DLG3P mixture and by LG3P alone, using eq 3, where (kAct)XG3P are third-order rate constants (kcat/Km)E•Act/Kd for activation by individual enantiomers of G3P or the racemic mixture.

| (3) |

No products of the D37G variant-catalyzed decarboxylation of FO were observed over a period of 5 days, for reactions in the presence of 0.040 M DLG3P or 0.040 M LG3P. Our experimental methods could have detected a D37 variant-catalyzed decarboxylation reaction with an apparent second-order rate constant of (kcat/Km)obs = 1.8 × 10−6 M−1 s−1. Combining this with 0.040 M, the largest activator concentration used in these experiments, gives an upper limit of (kcat/Km)E•Act/Kd < 5 × 10−5 M−2 s−1 for activation of this variant by DLG3P or LG3P reported in Table 2.

Previous studies on OMPDC have shown that the productive binding of phosphite dianion activator to wild type OMPDC or variant enzymes is weak, (Kd ≈ 0.1 M)18, 24–26 because the strong dianion binding energy is only expressed at the transition state for OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation.3 This is also the case for dianion activation of T100’A variant-catalyzed reactions of EO (Figure 2) and FO (Figures 5 and 6). By comparison, the saturation of the D37G variant by phosphite and DE4P dianions (Figures 2 and 5) is consistent with two binding modes for these activators: (i) Productive binding, similar to that for wild type and T100’A OMPDC, where the activator binding energy is specifically expressed at the decarboxylation transition state. (ii) A nonproductive binding conformation that controls the shape of kinetic plots for the D37G variant. Nonproductive binding, with a higher affinity than for productive binding, will result in decreases in the values of both Kd and (kcat/Km)E•Act (Scheme 2), but will not affect the value of (kcat/Km)E•Act/Kd determined for reactions in the presence of low concentrations of the activator, where the variant enzyme exists mainly in the unliganded form.

DISCUSSION

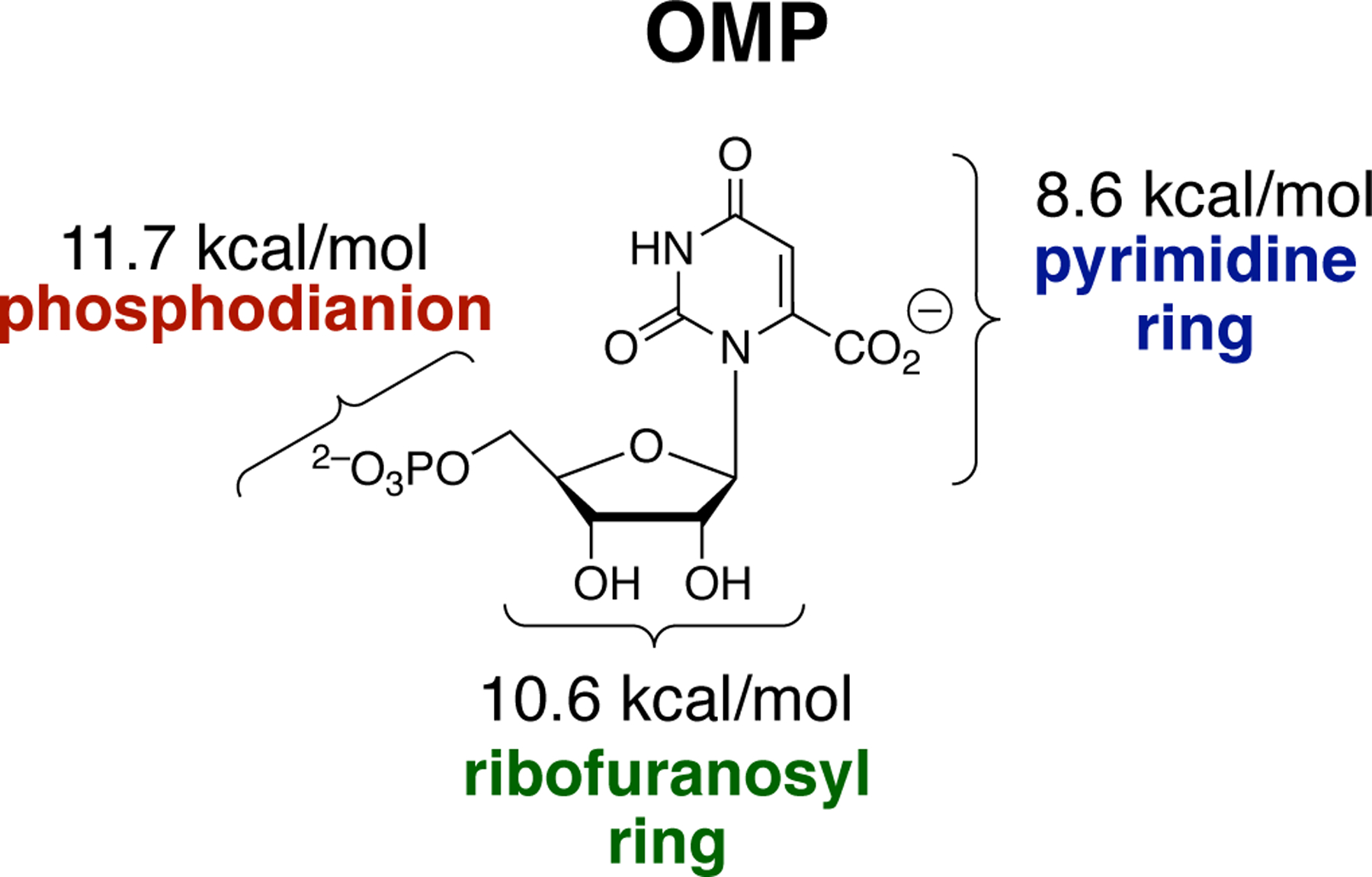

OMPDC provides a 31 kcal/mol stabilization of the decarboxylation transition state that is divided approximately equally between interactions with the three substrate fragments (Figure 7).11 The total transition state stabilization is much larger than the 8 kcal/mol stabilization of the Michaelis complex, and one goal of our studies on this enzyme has been to partition the total binding interactions into interactions expressed at the reaction ground state, and interactions that are only expressed as stabilization of the decarboxylation transition state.

Figure 7.

Contribution of the Substrate Fragments to the Total Intrinsic Substrate Binding Energy for OMPDC-Catalyzed Decarboxylation.

The Q215, Y217 and R235 side chains interact with the phosphodianion of OMP. The side chains are distant from the site of decarboxylation at the orotate ring, yet provide a total 12 kcal/mol stabilization of the transition for OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of OMP,18 an 8 kcal/mol stabilization of the transition state for phosphite dianion activated decarboxylation of EO,12, 18 but no detectable stabilization of the transition state for decarboxylation of EO alone.12,13 These results provide support for a model where ca 4 of the total 12 kcal/mol of dianion interactions are expressed at the ground-state complex, and ca 8 kcal/mol of the dianion interactions are utilized to drive an energetically unfavorable enzyme conformational change, from a floppy inactive open enzyme, to the rigid catalytically active protein cage.8, 27, 28

OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of FO is strongly activated by the binding of small sugar phosphate analogs of the phosphoribofuranosyl truncated substrate piece.11 The mechanism for sugar phosphate activation appears similar to that for phosphite dianion activation of OMPDC for catalysis of decarboxylation of EO, because the binding interactions of dianion gripper (Q217, Y217 and R235) and hydroxyl gripper (D37 and T100’) amino acid side chains are utilized to stabilize a closed conformation of OMPDC (Figure 1).

OMPDC-Catalyzed Decarboxylation of EO Catalyzed by D37 and T100’ Variants.

The D37G and T100’A substitutions at yeast OMPDC cause 2.1 and 2.3 kcal/mol increases, respectively, in ΔG‡ for kcat/Km for decarboxylation of OMP (Table 3), while the D37A and T100’G substitutions result in larger 4 and 5 kcal/mol increases.14 It was concluded that the effects of D37G and T100’A substitutions on ΔG‡ are localized to stabilizing interactions with the substrate phosphoribofuranosyl moiety, and that the larger effects of D37A and T100’G substitutions are due to additional increases in the barrier to a slow, partly rate determining, enzyme conformational change.14 We have focused on the D37G and T100’A substitutions, because their effects are due mainly to the elimination of interactions between OMPDC and the C-3’ (D37G) or C-2’ (T100’A) hydroxyl groups of the substrate OMP. The effects of the T100’A and D37G substitutions on ΔG‡ for OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of the whole substrate OMP and on the substrate pieces EO + phosphite dianion pieces are compared in Table 3. The 2.9 and 2.2 kcal/mol effects, respectively, of the T100’A and D37G substitutions on ΔG‡ of activation for decarboxylation of the substrate pieces are similar to their 2.3 and 2.1 kcal/mol effects on ΔG‡ for decarboxylation of OMP.12, 29

Table 3.

The Effect of T100’A and D37G Substitution on the Activation Barriers to OMPDC-Catalyzed Decarboxylation Reactions.a

For OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation reactions at pH 7.0, 25 °C and I = 0.105 (NaCl, OMP) or I = 0.14 (NaCl, EO).

Calculated from data reported in Table 1.

Table 3 shows that the 2.3 and 2.1 kcal/mol effects, respectively, of T100’A and D37G substitutions on ΔG‡ for decarboxylation of OMP may be partitioned into a 1.4 kcal/mol increase in ΔG‡ decarboxylation of EO, due to loss of an interaction with a substrate ribofuranosyl hydroxyl, and 0.9 and 0.7 kcal/mol decreases in transition state stabilization by protein interactions with the substrate dianion. This corresponds to a 5–10% reduction in transition state stabilization from interactions with the phosphodianion of OMP [intrinsic dianion binding energy].2 The intrinsic dianion binding energy, calculated from the ratio of values of kcat/Km for wild type and variant OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of OMP and EO (Table 1), decreases from 11.7 kcal/mol for wild type OMPDC12, 18 to 10.8 and 11.0 kcal/mol respectively, for T100’A and D37G variants. Removal of the ribosyl ring from EO results in a related 2.5 kcal/mol decrease in ΔG‡act (eq 4 and Scheme 4) for stabilization of the decarboxylation transition state by phosphite dianion, from 7.7 kcal/mol for decarboxylation of EO,18 to 5.2 kcal/mol for decarboxylation of FO (Chart 1).11

Scheme 4.

Activation of OMPDC-Catalyzed Reactions of Truncated Substrates by Phosphite Dianion and Small Sugar Phosphates.

These results show that ribosyl hydroxyl groups are required for the observation of optimal stabilizing interactions between OMPDC and enzyme-bound dianions. They are consistent with an interaction between the phosphodianion and ribosyl binding sites. There is a chain of two water molecules that connect the substrate phosphodianion and the T100’ side chain (Figure 8). We suggest that this chain is essential to optimize protein-dianion interactions, and that perturbation of the chain by the T100’A and D37G substitutions has the effect of weakening stabilizing protein-dianion interactions.

| (4) |

Figure 8.

A pancake representation of yeast OMPDC complexed with an intermediate analog 6-hydroxyuridine 5’-monophosphate (BMP) adapted from PDB 1DQX. The representation shows contacts between the protein and the ligand phosphate group (red dashed lines), ribose ring (green dashed lines), and pyrimidine ring (blue dashed lines). The D37 and T100’ side chains form hydrogen bonds to the C-3’ and C-2’ ribosyl hydroxyls, respectively, and interact with one another and the phosphodianion through a chain of two water molecules.

OMPDC-Catalyzed Decarboxylation of FO by D37G and T100’A Variants.

Chart 2 compares the effect of D37G and T100’A substitutions on ΔG‡act for dianion activated OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of FO, calculated from data in Table 2. The substitution of the T100’ side chain has little effect on the activation barrier to decarboxylation of FO (Table 2), because this side chain does not interact with the decarboxylation transition state.

Chart 2.

The Effect of D37G and T100’A Substitutions on ΔG‡act for the Interaction of the Transition State for OMPDC-Catalyzed Decarboxylation of FO with Dianion Activators (Scheme 4).

The D37 side chain interacts with the C-3 ribofuranosyl hydroxyl of OMP, which binds to OMPDC in the same orientation of the C-3 hydroxyl of DG3P. The larger effect of the D37G (> 3.2 kcal/mol) compared to T100’A (1.3 kcal/mol) substitution on ΔG‡act for DG3P-activated decarboxylation of FO (Chart 2) shows that these substitutions eliminate the side chain-activator interactions with D37 but not T100’. There are no direct interactions of the T100’ side chain with either phosphite dianion or DG3P activators, so that the 0.9 and 1.3 kcal/mol effect, respectively, of the T100’A substitution on ΔG‡act (Chart 2) are consistent with a role for the T100’ side chain in optimizing transition state stabilization by interaction with dianion activators, as discussed above.

The D37G and T100’A substitutions result in 2.5 and 2.8 kcal/mol increases, respectively, in ΔG‡act for DE4P-activated decarboxylation of FO (Chart 2), consistent with similar stabilizing side chain interactions with the C-3 and C-2 activator hydroxyls, respectively. These effects of D37G and T100’A substitutions on ΔG‡act are similar to their effects on ΔG‡ for decarboxylation of the whole substrate OMP and the substrate piece EO + phosphite dianion (Table 3). We conclude that these side chains exhibit similar stabilizing interactions with the transition states for OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of OMP (Table 3), for phosphite dianion activated decarboxylation of EO (Table 3), and for DE4P activated decarboxylation of FO (Chart 2). The results support the conclusion that the side chains function to hold OMPDC in the closed conformation that provides effective catalysis of decarboxylation of the orotate rings at OMP, EO and FO.

The Enzyme-Activating Conformational Change.

Scheme 5 was proposed to rationalize activation of OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of the truncated substrate EO by phosphite dianion.7 This Scheme is essentially the same as for Koshland’s induced fit model.30, 31 Unliganded EO is inactive, because the catalytic side chains are poorly positioned to interact with the enzyme-bound transition state; and, the active enzyme EC is present in exceedingly low concentrations (KC ≪ 1). Phosphite dianion activates OMPDC for catalysis of decarboxylation by causing an increase in the concentration of active enzyme EC. The observed binding affinity of phosphite dianion (Kd ≈ 0.1 M) is much weaker than the affinity of the dianion for the active enzyme EC,18 because most of the dianion binding energy is used to drive the activating enzyme conformational change from EO to EC [(Kd)obs = Kd’/Kc, Scheme 5)

Scheme 5.

Activation of the Unliganded of OMPDC (EO) for Catalysis of the Reaction of Truncated Substrates by Stabilization of an Organized Closed Enzyme (EC).

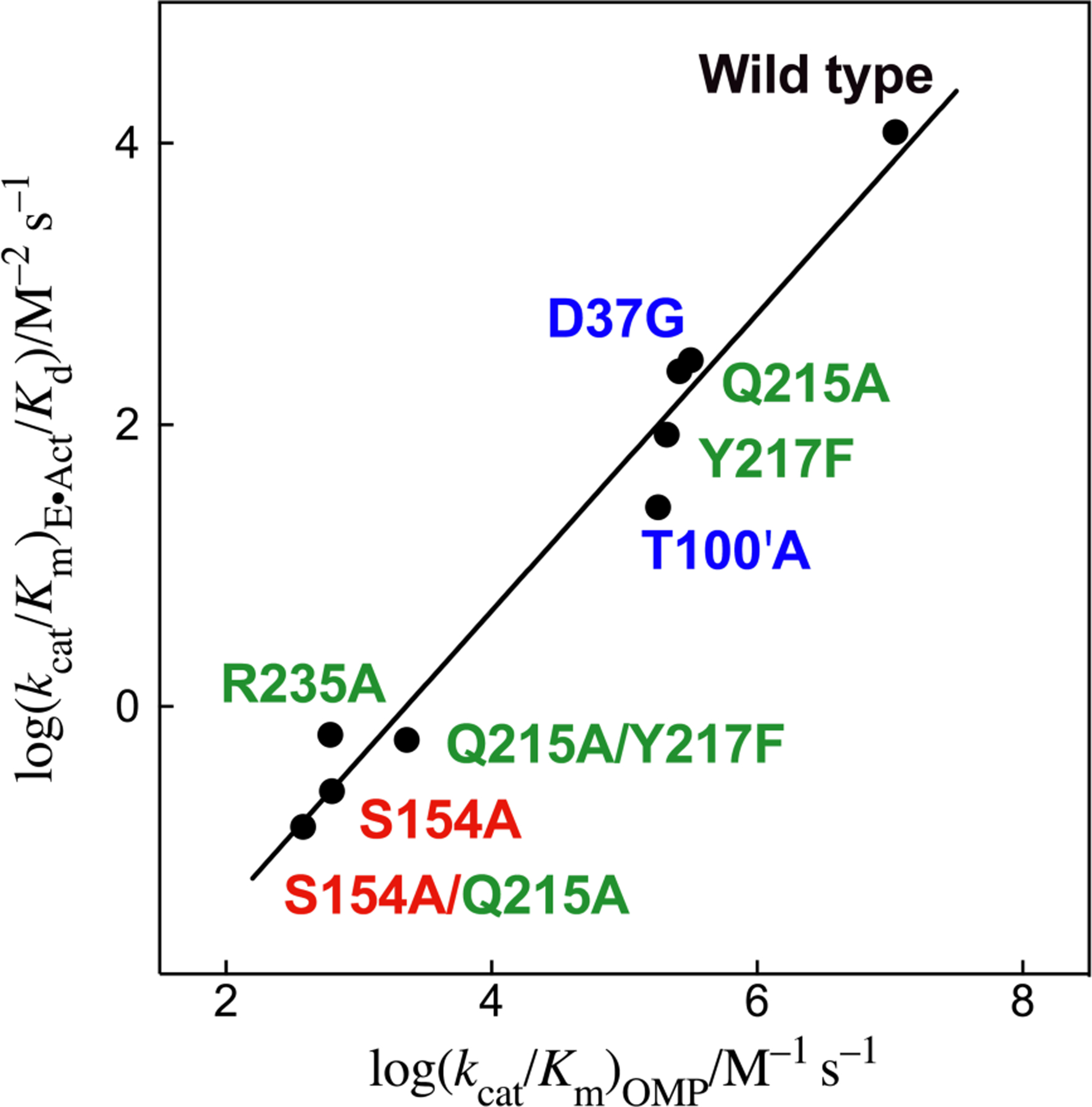

Figure 1 shows that the side chains of OMPDC that interact with the substrate phosphodianion and the ribosyl ring are positioned to drive the expansive activating conformational change from EO to active EC. We have examined nine variants of OMPDC, prepared by single or pairwise substitutions of six side chains that interact with either the substrate phosphodianion (Q215, Y217 and R235),12, 13, 32, 33 the Q215 side chain and substrate pyrimidine ring (S154),24 or a ribosyl -OH (D37 and T100’) (Table 3). Figure 9 shows a linear logarithmic correlation, with slope 1.05 ± 0.07, of rate constants (kcat/Km)OMP for direct decarboxylation of OMP and (kcat/Km)E•Act/Kd for phosphite dianion activation of the reaction of EO (Scheme 2) for reactions catalyzed by wild type OMPDC and these variants. This linear correlation shows that the transition states for the enzyme-catalyzed reactions of whole substrate OMP and the phosphite dianion activated reaction of EO are stabilized by essentially the same interactions with the substituted protein side chains. They are rationalized by Scheme 5, where the binding interactions of each of these six side chain are utilized to hold OMPDC in the active closed conformation EC, which shows the same catalytic activity for decarboxylation of the whole substrate OMP and the HPi + EO substrate pieces.12, 27, 29, 34, 35

Figure 9.

Linear free energy relationship, with slope 1.05 ± 0.07, between second-order rate constants (kcat/Km)OMP for wild type and variant OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of OMP and third-order rate constants (kcat/Km)E•Act/Kd for the OMPDC-catalyzed reactions of the substrate pieces HPi + EO (Scheme 2). The side chains that interact with the phosphodianion and pyrimidine ring are shown using green and red print, respectively. Literature data are used for reactions catalyzed by S154A and S154A/Q215A variants,24 and by Q215A, Y217F, Q215A/Y217F and R235A variants.12, 13

Imperatives for Enzyme-Activating Conformational Changes.

The results of our studies on OMPDC,18 TIM,36 and GPDH19 and several glycolytic enzymes,37, 38 have shown that the binding energy of their substrate phosphodianions is utilized to mold these catalysts into catalytically active forms (Scheme 5). The present work shows that the global enzyme-activating conformational change for OMPDC involves interactions of the protein with both the substrate phosphodianion and ribosyl hydroxyl groups, where the interactions between these fragments provide a 22 kcal/mol stabilization of the transition state. One difficult challenge met during the evolution of OMPDC was the coordination of motions of the several mobile protein structural elements that interact with phosphodianion and ribosyl hydroxyl groups of OMP at the closed enzyme. This includes the α-helix (G98’–S106’), which lies at a second protein subunit. The identification of amino acid sequences capable of undergoing such activating protein conformational changes represents a difficult challenge for those occupied with the design of proteins that show enzyme-like activity.

We note at least three imperatives that propelled the evolution of enzyme catalysts that conform to Scheme 5.

The primary advantage to catalysis at cages, where the protein surrounds the substrate, is that these active sites provide for optimal stabilizing protein-ligand interactions.39 However, trapping the substrate in a protein cage precludes formation of the Michaelis complex by the direct binding and release of the ligand. Therefore, the substrate first binds to an exposed enzyme active site, and the large ligand binding energy is then used to mold the flexible protein structure into the more rigid protein cage.40 A large fraction of this ligand binding energy is specifically expressed at the decarboxylation transition state, and results in the observed high specificity in transition state binding.

The relatively nonpolar environment of protein cages, compared to aqueous solution, strongly promotes catalysis of many reactions, such as enzyme-catalyzed reactions that proceed through radical intermediates which do not form at an appreciable rate in water.41, 42 It also holds for OMPDC, where hydrophobic F89, I183 and I232 side chains line the carboxylate anion binding pocket. These side chains provide a local hydrophobic environment, that interacts favorably with nascent CO2 at the late decarboxylation transition state.4, 43, 44

One requirement for efficient catalysis by enzymes, which show very strong stabilizing interactions with their protein bound transition states, is that the ligand binding energy not be fully expressed at the reaction ground state. This avoids tight and effectively irreversible ligand binding.2, 3 The use of substrate binding energy to drive protein conformational changes, in turn, avoids the full expression at the Michaelis complex of the large binding energies required for effective transition state stabilization. This substrate-induced induction of strain into protein catalysts represents a readily generalizable mechanism for obtaining specificity in transition state binding.2

The binding energy of the adenosyl groups of substrates ATP and AMP is utilized to drive a large change in the conformation of adenylate kinase from EO to EC (Scheme 5).45 The interactions between the adenosyl group of AMP and adenylate kinase stabilize the transition state for enzyme-catalyzed phosphoryl transfer from ATP by ≥14.7 kcal/mole, while interactions with the substrate piece (1-β-D-erythrofuranosyl)adenine stabilize the transition state for phosphoryl transfer from ATP to phosphite dianion by ≥8.7 kcal/mole.46 There are many other enzyme conformational changes that occur upon substrate binding, which may facilitate catalysis by stabilizing the structure for a catalytically active closed form of the catalyst, relative to the open form that binds substrate. These include: (i) The conformational changes driven by protein interactions with the coenzyme A fragment of thioester substrates, such as for the reaction catalyzed by coenzyme A transferase.47 (ii) The conformational change driven by interactions with the adenosyl groups of adenine nucleotide substrates for other enzyme-catalyzed phosphoryl transfer reactions. (iii) The conformational change driven by interactions with the ADP-ribosyl fragment of the NAD cofactor for the hydride transfer reaction catalyzed by alcohol dehydrogenase.48

In conclusion, these results add to the body evidence that enzyme-activation by binding interactions of proteins with remote substrate pieces is the result of utilization of the intrinsic substrate binding energy to drive protein conformational changes that stabilize active closed forms of enzyme catalysts. In other words, the difference between the intrinsic and observed substrate binding energies is the binding energy utilized to drive the conformational change that generates the catalytically active enzyme.2, 3 The failure to develop computational models for this important role for protein conformational changes in enzyme catalysis is due, in part, to the difficulty in calculating ligand binding energies, when ligand binding is coupled to a large protein conformational change. The development of these protocols is necessary to model substrate binding, in cases such as OMPDC where a large fraction of the intrinsic binding energy is used to drive an extensive protein conformational change.

Supplementary Material

FUNDING.

We acknowledge the National Institutes of Health Grants GM116921 and GM134881 for generous support of this work.

ABBREVIATIONS.

- OMPDC

orotidine 5’-monophosphate decarboxylase

- OMP

orotidine 5’-monophosphate

- UMP

uridine 5’-monophosphate

- EO

1-(β-D-erythrofuranosyl)orotic acid

- EU

1-(α-D-erythrofuranosyl)uracil

- FO

5-fluoroorotic acid

- FU

5-fluorouracil

- MOPS

3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid

- DE4P

d-erythritol 4-phosphate

- DLG3P

d,l-glycerol 3-phosphate

- DG3P

d-glycerol 3-phosphate

- LG3P

l-glycerol 3-phosphate

- Act

Activator

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION.

Figures S1 and S2 show representative HPLC chromatograms, obtained at several reaction times, in experiments to monitor the products of decarboxylation of EO catalyzed by D37G (Figure S1) and T100’A (Figure S2) variants of OMPDC. Figure S3 shows the increase in [EU]/[E][EO]o with time for T100’A and D37G variant-catalyzed decarboxylation of EO. Figures S4 and S5 show representative HPLC chromatograms, obtained at several reaction times, in experiments to monitor the products of decarboxylation of FO catalyzed by the T100’A variant of OMPDC (Figure S4) and T100’A variant-catalyzed decarboxylation of FO activated by DE4P (Figure S5). The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Accession Codes

Yeast Orotidine 5’-Monophosphate Decarboxylase - P03962

REFERENCES

- 1.Pauling L, The nature of forces between large molecules of biological interest. Nature 1948, 161, 707–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jencks WP, Binding energy, specificity, and enzymic catalysis: the Circe effect. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol 1975, 43, 219–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amyes TL; Richard JP, Specificity in transition state binding: The Pauling model revisited. Biochemistry 2013, 52 (12), 2021–2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsang W-Y; Wood BM; Wong FM; Wu W; Gerlt JA; Amyes TL; Richard JP, Proton Transfer from C-6 of Uridine 5’-Monophosphate Catalyzed by Orotidine 5’-Monophosphate Decarboxylase: Formation and Stability of a Vinyl Carbanion Intermediate and the Effect of a 5-Fluoro Substituent. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 14580–14594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amyes TL; Wood BM; Chan K; Gerlt JA; Richard JP, Formation and Stability of a Vinyl Carbanion at the Active Site of Orotidine 5’-Monophosphate Decarboxylase: pKa of the C-6 Proton of Enzyme-Bound UMP. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130 (5), 1574–1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Radzicka A; Wolfenden R, A proficient enzyme. Science 1995, 267 (5194), 90–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richard JP; Amyes TL; Reyes AC, Orotidine 5’-Monophosphate Decarboxylase: Probing the Limits of the Possible for Enzyme Catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res 2018, 51 (4), 960–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richard JP, Protein Flexibility and Stiffness Enable Efficient Enzymatic Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141 (8), 3320–3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller BG; Hassell AM; Wolfenden R; Milburn MV; Short SA, Anatomy of a proficient enzyme: the structure of orotidine 5’-monophosphate decarboxylase in the presence and absence of a potential transition state analog. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci 2000, 97 (5), 2011–2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan KK; Wood BM; Fedorov AA; Fedorov EV; Imker HJ; Amyes TL; Richard JP; Almo SC; Gerlt JA, Mechanism of the Orotidine 5’-Monophosphate Decarboxylase-Catalyzed Reaction: Evidence for Substrate Destabilization. Biochemistry 2009, 48 (24), 5518–5531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reyes AC; Amyes TL; Richard J, Enzyme Architecture: Erection of Active Orotidine 5’-Monophosphate Decarboxylase by Substrate-Induced Conformational Changes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 16048–16051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldman LM; Amyes TL; Goryanova B; Gerlt JA; Richard JP, Enzyme Architecture: Deconstruction of the Enzyme-Activating Phosphodianion Interactions of Orotidine 5’-Monophosphate Decarboxylase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136 (28), 10156–10165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amyes TL; Ming SA; Goldman LM; Wood BM; Desai BJ; Gerlt JA; Richard JP, Orotidine 5’-monophosphate decarboxylase: Transition state stabilization from remote protein-phosphodianion interactions. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 4630–4632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brandão TAS; Richard JP, Orotidine 5’-Monophosphate Decarboxylase: The Operation of Active Site Chains Within and Across Protein Subunits. Biochemistry 2020, 59 (21), 2032–2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Vleet JL; Reinhardt LA; Miller BG; Sievers A; Cleland WW, Carbon isotope effect study on orotidine 5’-monophosphate decarboxylase: support for an anionic intermediate. Biochemistry 2008, 47 (2), 798–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gross A; Abril O; Lewis JM; Geresh S; Whitesides GM, Practical synthesis of 5-phospho-D-ribosyl α-1-pyrophosphate (PRPP): enzymatic routes from ribose 5-phosphate or ribose. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 105 (25), 7428–7435. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goryanova B; Goldman LM; Amyes TL; Gerlt JA; Richard JP, Role of a Guanidinium Cation–Phosphodianion Pair in Stabilizing the Vinyl Carbanion Intermediate of Orotidine 5’-Phosphate Decarboxylase-Catalyzed Reactions. Biochemistry 2013, 52 (42), 7500–7511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amyes TL; Richard JP; Tait JJ, Activation of orotidine 5’-monophosphate decarboxylase by phosphite dianion: The whole substrate is the sum of two parts. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127 (45), 15708–15709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsang W-Y; Amyes TL; Richard JP, A Substrate in Pieces: Allosteric Activation of Glycerol 3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (NAD+) by Phosphite Dianion. Biochemistry 2008, 47 (16), 4575–4582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moffatt JG, The synthesis of orotidine 5’-phosphate. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1963, 85, 1118–1123. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duschinsky R; Pleven E; Heidelberger C, The Synthesis of 5-Fluoropyrimidines. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1957, 79 (16), 4559–4560. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gasteiger E; Hoogland C; Gattiker A; Duvaud A; Wilkins MR; Appel RD; Bairoch A, Protein Identification and Analysis Tools on the ExPASy Server. Proteomics Protocols Handbook 2005, 571–607. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gasteiger E; Gattiker A; Hoogland C; Ivanyi I; Appel RD; Bairoch A, ExPASy: The proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nuc. Acids Res 2003, 31 (13), 3784–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barnett SA; Amyes TL; Wood BM; Gerlt JA; Richard JP, Dissecting the Total Transition State Stabilization Provided by Amino Acid Side Chains at Orotidine 5’-Monophosphate Decarboxylase: A Two-Part Substrate Approach. Biochemistry 2008, 47 (30), 7785–7787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goryanova B; Amyes TL; Gerlt JA; Richard JP, OMP Decarboxylase: Phosphodianion Binding Energy Is Used To Stabilize a Vinyl Carbanion Intermediate. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133 (17), 6545–6548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goryanova B; Spong K; Amyes TL; Richard JP, Catalysis by Orotidine 5’-Monophosphate Decarboxylase: Effect of 5-Fluoro and 4’-Substituents on the Decarboxylation of Two-Part Substrates. Biochemistry 2013, 52 (3), 537–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amyes TL; Malabanan MM; Zhai X; Reyes AC; Richard JP, Enzyme activation through the utilization of intrinsic dianion binding energy. Prot. Eng. Des. Sel 2017, 30 (3), 157–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richard JP; Amyes TL; Goryanova B; Zhai X, Enzyme architecture: on the importance of being in a protein cage. Cur. Opin. Chem. Biol 2014, 21 (0), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richard JP; Cristobal JR; Amyes TL, Linear Free Energy Relationships for Enzymatic Reactions: Fresh Insight from a Venerable Probe. Acc. Chem. Res 2021, 54 (10), 2532–2542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas JA; Koshland DE Jr., Competitive inhibition by substrate during enzyme action. Evidence for the induced-fit theory. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1960, 82, 3329–33. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koshland DE Jr., Application of a Theory of Enzyme Specificity to Protein Synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 1958, 44, 98–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reyes AC; Plache DC; Koudelka AP; Amyes TL; Gerlt JA; Richard JP, Enzyme Architecture: Breaking Down the Catalytic Cage that Activates Orotidine 5′-Monophosphate Decarboxylase for Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 17580–17590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goryanova B; Goldman LM; Ming S; Amyes TL; Gerlt JA; Richard JP, Rate and Equilibrium Constants for an Enzyme Conformational Change during Catalysis by Orotidine 5’-Monophosphate Decarboxylase. Biochemistry 2015, 54 (29), 4555–4564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhai X; Amyes TL; Richard JP, Role of Loop-Clamping Side Chains in Catalysis by Triosephosphate Isomerase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137 (48), 15185–15197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhai X; Amyes TL; Richard JP, Enzyme Architecture: Remarkably Similar Transition States for Triosephosphate Isomerase-Catalyzed Reactions of the Whole Substrate and the Substrate in Pieces. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 4145–4148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amyes TL; Richard JP, Enzymatic catalysis of proton transfer at carbon: activation of triosephosphate isomerase by phosphite dianion. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 5841–5854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fernandez PL; Nagorski RW; Cristobal JR; Amyes TL; Richard JP, Phosphodianion Activation of Enzymes for Catalysis of Central Metabolic Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2021, 143, 2694–2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ray WJ Jr.; Long JW; Owens JD, An analysis of the substrate-induced rate effect in the phosphoglucomutase system. Biochemistry 1976, 15 (18), 4006–4017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolfenden R, Enzyme catalysis. Conflicting requirements of substrate access and transition state affinity. Mol. Cell. Biochem 1974, 3 (3), 207–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malabanan MM; Amyes TL; Richard JP, A role for flexible loops in enzyme catalysis. Cur. Opin. Struct. Biol 2010, 20 (6), 702–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Greene BL; Taguchi AT; Stubbe J; Nocera DG, Conformationally Dynamic Radical Transfer within Ribonucleotide Reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139 (46), 16657–16665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ge J; Yu G; Ator MA; Stubbe J, Pre-Steady-State and Steady-State Kinetic Analysis of E. coli Class I Ribonucleotide Reductase. Biochemistry 2003, 42 (34), 10071–10083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wittmann JG; Heinrich D; Gasow K; Frey A; Diederichsen U; Rudolph MG, Structures of the human orotidine-5’-monophosphate decarboxylase support a covalent mechanism and provide a framework for drug design. Structure 2008, 16 (1), 82–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goryanova B; Amyes TL; Richard JP, Role of the Carboxylate in Enzyme-Catalyzed Decarboxylation of Orotidine 5'-Monophosphate: Transition State Stabilization Dominates Over Ground State Destabilization. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141 (34), 13468–13478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kerns SJ; Agafonov RV; Cho Y-J; Pontiggia F; Otten R; Pachov DV; Kutter S; Phung LA; Murphy PN; Thai V; Alber T; Hagan MF; Kern D, The energy landscape of adenylate kinase during catalysis. Nature 2015, 22 (2), 124–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fernandez PL; Richard JP, Adenylate Kinase-Catalyzed Reaction of AMP in Pieces: Enzyme Activation for Phosphoryl Transfer to Phosphite Dianion. Biochemistry 2021, 60, doi/ 10.1021/acs.biochem.1c00535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mullins EA; Kappock TJ, Crystal Structures of Acetobacter aceti Succinyl-Coenzyme A (CoA):Acetate CoA-Transferase Reveal Specificity Determinants and Illustrate the Mechanism Used by Class I CoA-Transferases. Biochemistry 2012, 51 (42), 8422–8434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Plapp BV; Charlier HA Jr.; Ramaswamy S, Mechanistic implications from structures of yeast alcohol dehydrogenase complexed with coenzyme and an alcohol. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 2016, 591, 35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.