Abstract

A 14-year-old boy with a skeletal Class II malocclusion and open bite whose chief complaint was a posterior crossbite showed a canted occlusal plane with asymmetric gummy smile and mandibular deviation at clinical examination. The treatment with miniscrews focused on the bilateral intrusion of the maxillary posterior teeth and, after resolving the open bite, a new biomechanical technique involving joined miniscrews was applied for an en masse intrusion of the left side. This treatment strategy achieved optimal occlusion with improvements to the sagittal, vertical, and transverse relationships and achieved a harmonious smile.

Keywords: Miniscrews, Occlusal plane, Canting

INTRODUCTION

A skeletal anterior open bite has been long considered one of the most difficult malocclusions to treat. It has multiple etiologies: an unfavorable growth pattern; increased anterior dentoalveolar height1; an increased lower anterior and a decreased posterior facial height; clockwise rotation of the mandibular plane2; increased gonial angle; narrow maxillary arch3; habits, such as thumb sucking or abnormal tongue behavior4; and respiratory problems, such as enlarged adenoids or other airway obstructions.5

In addition, an open bite is often characterized by excessive growth of maxillary and mandibular posterior dentoalveolar heights, which is difficult to reduce. Orthopedic devices—such as high-pull headgears,6 vertical elastics, functional appliances to help eliminate habits or bite blocks to stop growth in the posterior sectors—have frequently been used to treat such cases, although their effectiveness is often limited by the absence of patient cooperation. Temporary bone anchorage devices7–13 may be good treatment alternatives since they obviate the need for the patient's cooperation.

The purpose of this case report is to describe the treatment of a patient using miniscrews with a double purpose: to correct an anterior open bite and as a new approach for treating a canted occlusal plane with asymmetric gummy smile.

Diagnosis and Etiology

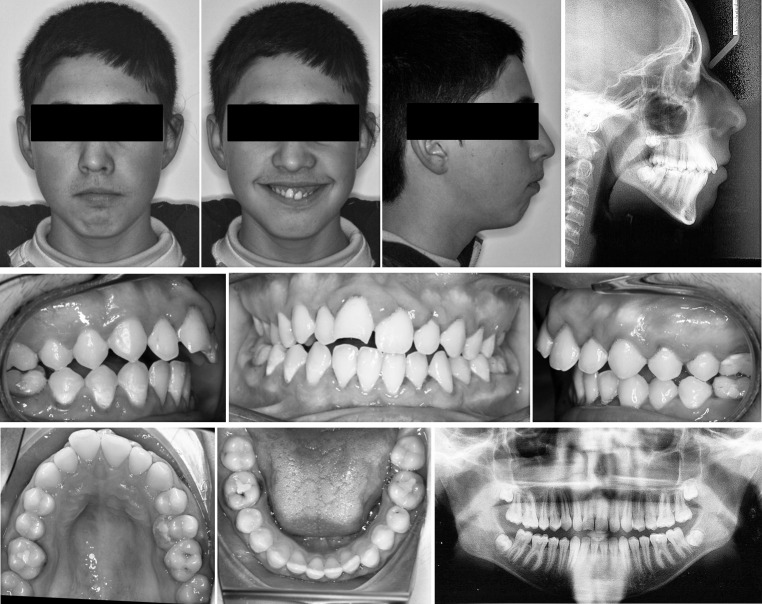

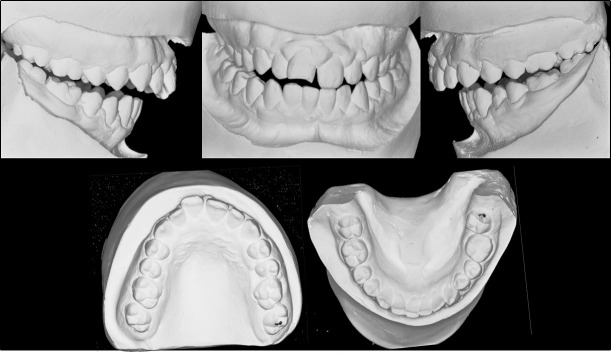

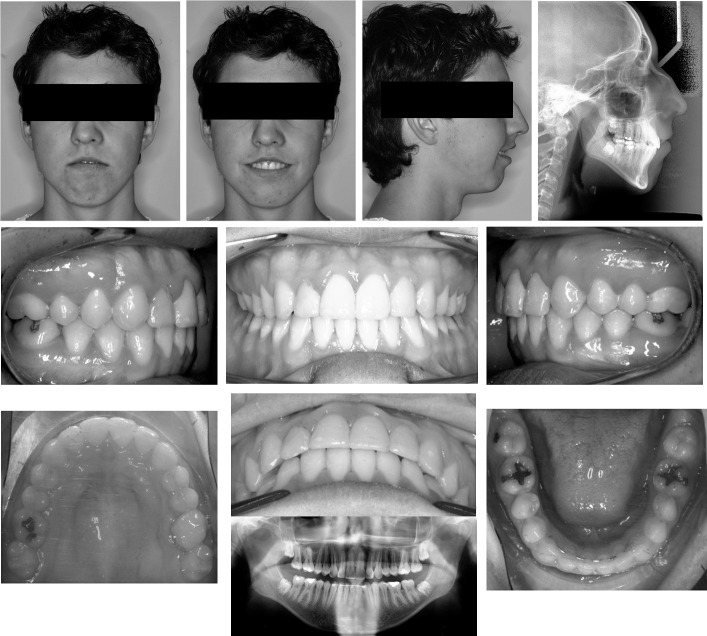

A 14-year-old boy visited the Orthodontic Department of our School of Dentistry (University of Seville, Seville, Spain). The mother's main complaint was the posterior crossbite and the anterior open bite of her son, which their family dentist had explained to her (Figure 1). The boy was a mouth breather and had a convex profile due to mandibular retrusion accentuated by clockwise mandibular rotation (Figure 1). He had a 7-mm overjet, with bilateral Angle Class I molars and Class II canines. Crowding was not severe and there were no signs of temporomandibular problems. The facial midlines did not coincide at the menton, and the anterior and lateral open bites, as well as the posterior crossbite, suggested that the centric relationship be checked and the first point of contact be determined. Dental casts were mounted in centric relation on an articulator (Figure 2). At this point, the sagittal and vertical relationships worsened, with a fulcrum between the second left molars. The dental midlines and the posterior crossbite were maintained, which indicated that the deviation was not functional.

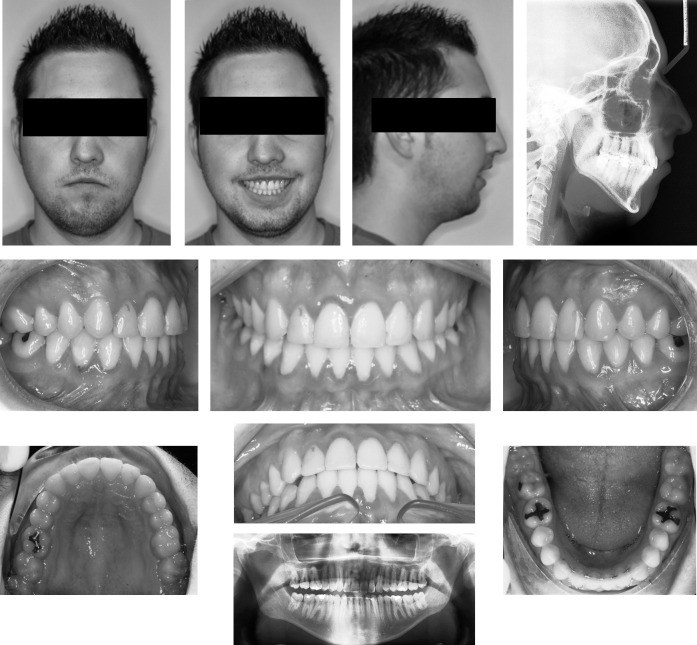

Figure 1.

Pretreatment facial and intraoral photographs.

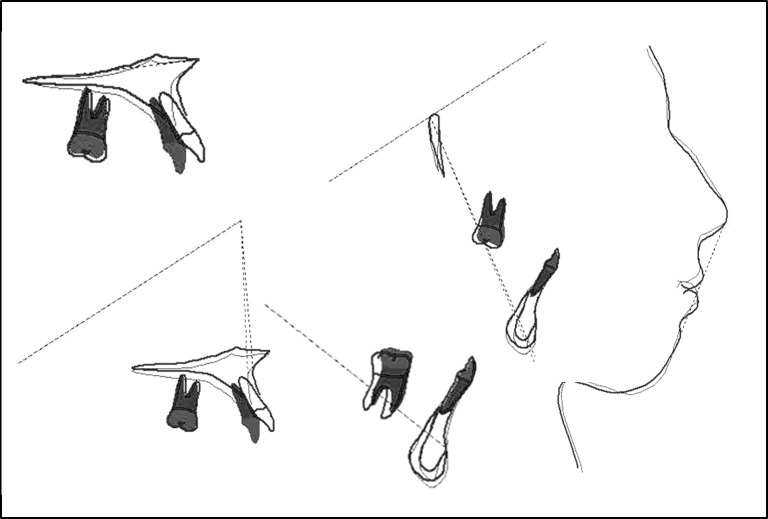

Figure 2.

Pretreatment dental casts mounted in centric relation on the articulator.

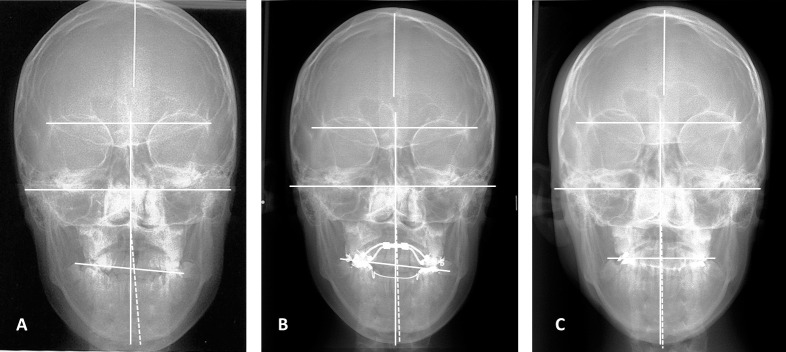

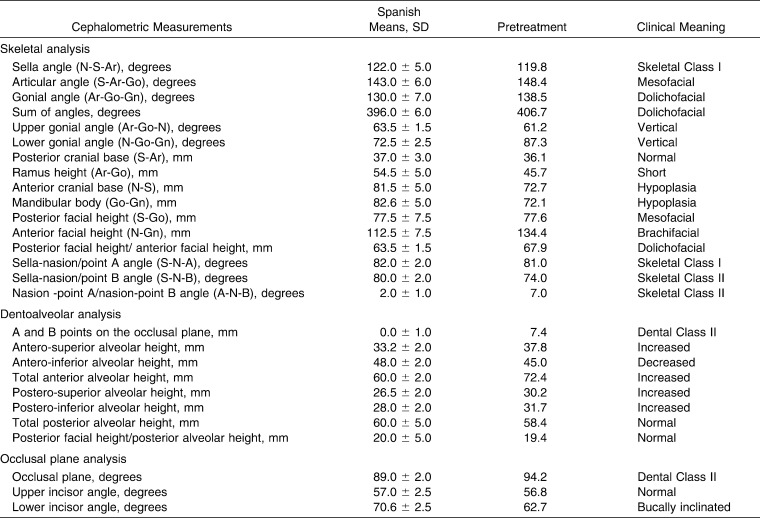

Extraorally, the patient presented a gummy smile, which was accentuated on the left side due to the canted occlusal plane (Figures 1 and 3). A cephalometric analysis (Table 1) showed that the patient was dolichofacial, with a skeletal Class II malocclusion. There was increased upper and lower dentoalveolar height, so that excessive growth of the posterior sector was considered the cause of the open bite.

Figure 3.

Posteroanterior cephalograms. (A) Pretreatment. (B) After rapid maxillary expansion. (C) Posttreatment.

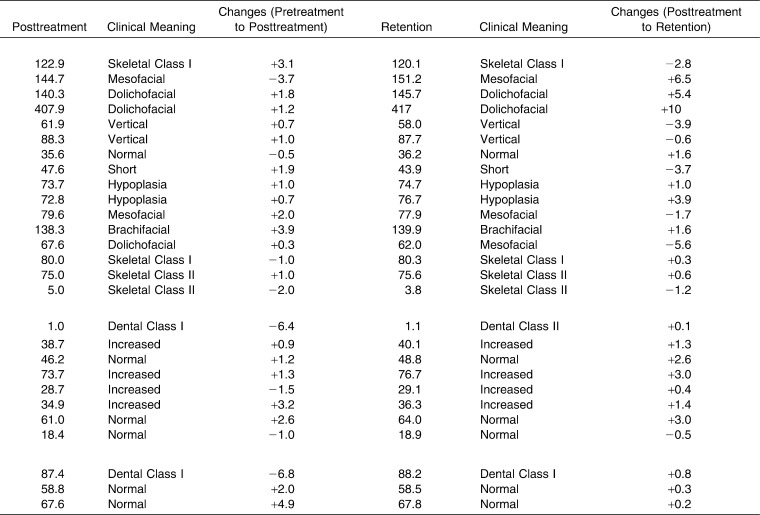

Table 1.

Cephalometric Data of the Pretreatment, Posttreatment, and 4 Years and 6 Months Retention Period

Table 1.

Extended

Treatment Objectives

The treatment objectives were to solve the crossbite, create an ideal overbite and overjet, and achieve Angle Class I molars and Class I canines, with coinciding facial and dental midlines. Since there was an occlusal cant in the frontal plane and the patient presented an asymmetric gummy smile, bilateral posterior intrusion and unilateral anterior intrusion were planned.

Treatment Alternatives

To correct a posterior crossbite, expansion is needed. In children, posterior crossbites are often corrected with slow or rapid maxillary expansion. A removable expansion plate or a fixed appliance, such as the Quad-Helix, provides slow expansion with light forces.14 Rapid maxillary expansion maximizes orthopedic correction of the transverse dimensions with heavier forces and has also been found to lead to increased nasal cavity and nasopharynx volumes.15,16 In patients with a hyperdivergent facial pattern, however, rapid maxillary expansion would worsen the vertical dimension.17–19 Some good recent research, however, has found that rapid maxillary expansion is not a contraindication for the hyperdivergent patient.20 Since the patient was a mouth breather, we chose rapid maxillary expansion for the first phase of treatment to resolve the maxillary compression and the posterior crossbite, and we used a fixed lingual bar to compress the overexpanded lower arch.21

Three treatment alternatives were presented to the patient:

A combined surgical and orthodontic treatment to resolve the open bite, gummy smile, and canted occlusal plane. The profile could be harmonized with an advancement genioplasty, while a sagittal split or intraoral vertical ramus osteotomy could help correct the mandibular deviation. The principal disadvantage was the age of the patient, which determined the postponement of surgical treatment.

A combined headgear-activator Teuscher appliance,22 followed by fixed appliance treatment, utilizing growth modification to reduce sagittal and vertical discrepancies and help correct the gummy smile. However, the results of this treatment option would depend on the patient's collaboration.

Temporary bone anchorage devices, such as miniscrews, combined with a fixed appliance to intrude the maxillary posterior teeth and resolve the open bite. This would create a counterclockwise rotation of the mandible and so help correct the sagittal discrepancy, although it would not correct the profile or the severely retruded mandible. Miniscrews would help resolve the canted occlusal plane and the asymmetric gummy smile.

After explaining the treatment alternatives to the patient and his parents, the last option was selected, with the parents' consent.

Treatment Progress

A hyrax expander appliance23 was attached to the first maxillary molars and first premolars to deal with the crossbite and palatal compression. The required expansion was achieved after 27 days of active expansion treatment at one turn per day (0.25 mm/day), followed by 4 months of expander retention with a lingual arch to compress the lower dental arch (Figure 4).

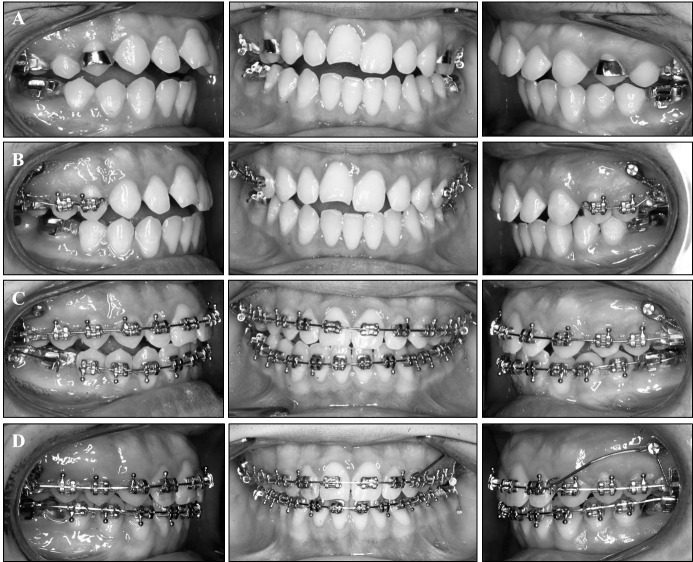

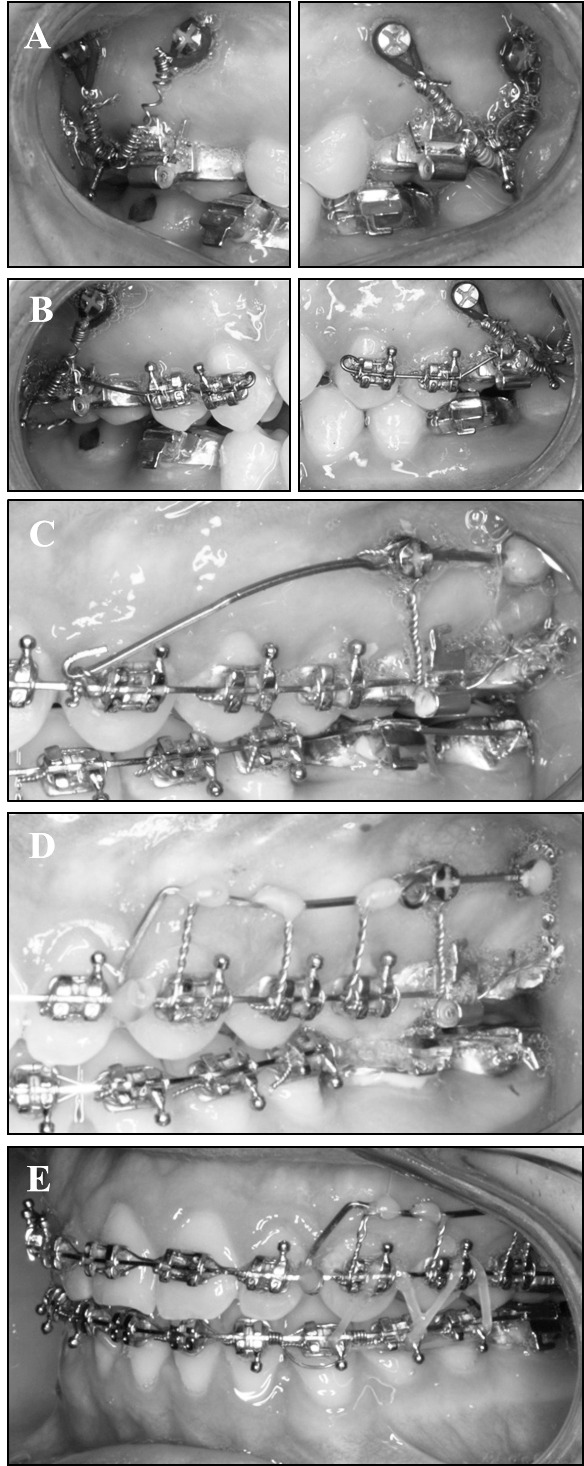

Figure 4.

Intraoral photographs of treatment progress. (A) After rapid maxillary expansion. (B) Progressive intrusion of molar and premolars. (C) Full superior and inferior bonding. (D) Correction of canted occlusal plane with joined miniscrew segmental archwire.

The hyrax expander appliance (Dentaurum, Inc, Newtown, PA) was removed and replaced with two transpalatal bars with bone anchorage for effective intrusion of the first and second molars. Two 1.6 × 8 mm ACR-model (H) miniscrews (Jeil Medical Corp, Seoul, South Korea) were inserted on each side, one between the roots of the maxillary second premolar and the first molar, the second between the roots of the first and second maxillary molars. Two closed Sentalloy coil springs (200 gr, GAC International, Bohemia, NY) were tied between the tubes attached to the molars and the miniscrews, and a 0.016 × 0.022-inch stainless steel segmental archwire was placed (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Intraoral photographs of miniscrew biomechanics. (A) Molar intrusion with miniscrews and two transpalatal bars. (B) Molar and premolar intrusion. (C) First stage of canted occlusal plane correction (superior intrusion). (D) Second stage of occlusal plane correction (superior anchorage). (E) Second stage of canted occlusal plane correction (inferior extrusion).

Brackets were not used in the first stages of treatment, although as intrusion developed, they were progressively fitted (0.018-inch slot brackets, MSE, DM-CEOSA, Madrid, Spain) first to the premolars, then the canines and incisors, using round 0.016-inch nickel-titanium archwire. Sequential nickel-titanium archwires were then used for alignment and leveling. When a 2.5-mm overbite had been achieved, posterior intrusion continued on the left side, leaving the right side inactive. To increase the bone anchorage, a 0.017 × 0.025-inch titanium-molybdenum-alloy (TMA) sectional archwire was passed through the holes of the two left miniscrews together and tied between the left canine and lateral left incisor (Figure 5). The sectional archwire was activated 45° to the occlusal plane to intrude the maxillary left anterior teeth, taking advantage of the increased bone anchorage from the two miniscrews inserted as a single unit, and to correct the canted occlusal plane. The occlusal plane was eventually corrected. The second stage of biomechanics required total bone anchorage to fix the superior left side in the vertical dimension. A 0.0017 × 0.025-inch TMA archwire was inserted, as before, although bent 90° and tied in an inactive way to the superior dental arch (Figure 5). Furthermore, the hemimaxilla was blocked as a single unit by tying stainless steel ties between the interproximal of each tooth and the 0.017 × 0.025-inch segmental archwire. Then, inferior extrusion was performed with vertical elastics and the patient's cooperation.

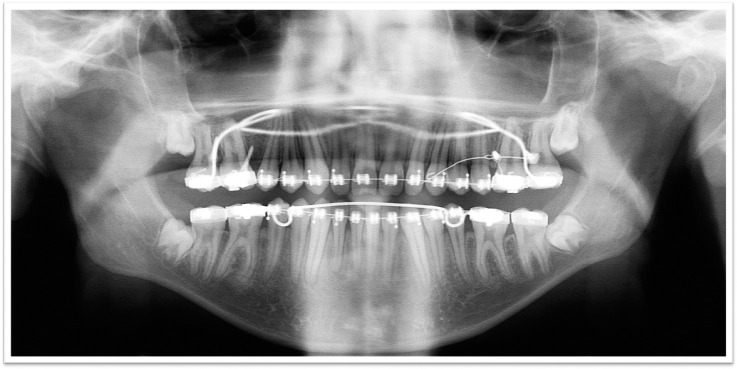

In the lower arch, the lingual bar was removed by the end of the treatment so that the first molars would migrate mesially into the space created between them and the second premolars and to obtain a stable Class I molar relationship (Angle). Root position parallelism was checked with a control orthopantomogram, and those brackets that needed replacing were replaced (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Control orthopantomogram of treatment.

The mesiodistal size of the maxillary lateral and central incisors was smaller than average, so these were reconstructed using composite materials to avoid spaces or unesthetic black triangles that might lead to relapse or create incorrect contact points. The total length of the second stage of treatment was 20 months. After debonding, a fixed canine-to-canine lingual retainer and a removable superior circumferential retainer were placed.

Treatment Results

The patient's treatment ended with the original treatment objectives having been achieved (Figure 7). Functional occlusion and lateral and protrusive jaw movements could be performed effectively and without improper contact with the rest of the teeth (Figure 8). The smile was fuller and more harmonious than before, equal in gingival height and with no black corridors, and the canted occlusal plane had been resolved (Figure 7). The posttreatment extraoral and intraoral photographs (Figure 7) and the frontal radiograph showed coincidence of the dental and facial midlines, and the slight improvement of the mandibular deviation induced by rapid maxillary expansion was completed after the posterior intrusion and correction of the canted occlusal plane (Figure 3). No complications or complaints from the patient were recorded concerning the miniscrews, and no signs of temporomandibular distress or pain were found. After treatment, a cephalometric analysis and the superimposed pretreatment and posttreatment tracings confirmed the changes. Incisor extrusion was minimal and the maxillary molars were intruded by 1.5 mm (Figure 9; Table 1). The posttreatment orthopantomogram showed the teeth to be parallel and with no root resorption (Figure 7). After a posttreatment period of 4 years and 6 months, the clinical results showed good stability (Figure 10). In addition, the cephalometric results appear substantially stable (Figure 11; Table 1).

Figure 7.

Posttreatment facial and intraoral photographs.

Figure 8.

Functional jaw movements, protrusive, left and right laterally, with complete posterior distocclusion.

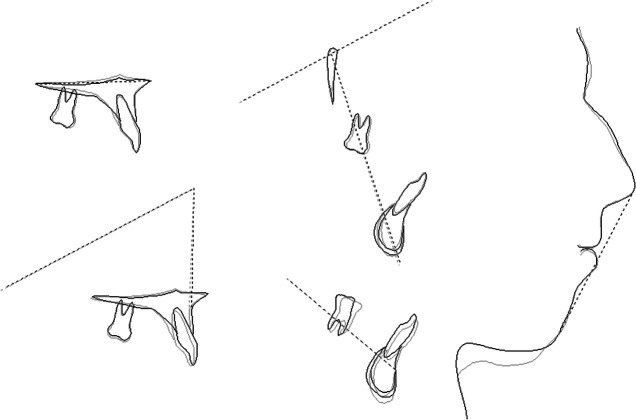

Figure 9.

Superimposed pretreatment (blue) and posttreatment (red) tracings.

Figure 10.

Retention facial and intraoral photographs (4 years and 6 months after treatment).

Figure 11.

Superimposed posttreatment (blue) and retention (4 years and 6 months) (red) tracings.

DISCUSSION

Two different points should be discussed concerning the treatment of this patient: the open bite and the canted occlusal plane with asymmetric gummy smile. With respect to the first point, conventional nonsurgical techniques rely on extrusion of the incisors rather than intrusion of the posterior sectors in order to resolve open bites.24 In this patient, two transpalatal bars and two miniscrews were used on each side, placed between the roots of the maxillary second premolar and the first molar, and between the first and second maxillary molars, so that the effect would be spread equally over both molars. Intrusion of the molars has been reported as being more stable over time than extrusion of the incisors,25 causing occlusal plane change and leading to counterclockwise rotation of the mandible which may improve the profile in skeletal Class II cases. Nevertheless, a conventional orthodontic treatment of an open bite, consisting of vertical elastics which may increase the plane angle26 and the gummy smile,27 generally results in extrusion of the incisors. According to a study performed by Deguchi et al.,28 miniscrews were more effective for absolute molar intrusion and the improvement in esthetics than conventional techniques. They also had an effect on the soft tissues, with more obviously reduced facial convexity in the miniscrew group; the extrusion of the molars arising from conventional techniques may cause a clockwise rotation of the mandible, which is not a desirable outcome in a patient with skeletal Class II malocclusion.

It has also been reported in the literature that miniscrews may achieve molar intrusion between 1 and 3 mm and a counterclockwise rotation of the mandible position of 3°. Xun et al.29 reported intrusion of the maxillary and mandibular molars of 1.8 and 1.2 mm, respectively, and a 2.3° counterclockwise mandibular rotation. In this patient, a 1.5-mm intrusion of the maxillary molars was achieved, enough for a counterclockwise rotation of the occlusal plane from a Class II to a Class I, with a normalized Wits appraisal. Minimal incisor extrusion was observed with this technique.

The second key point of treatment was the canted occlusal plane and asymmetric gummy smile.

In terms of etiology, the patient was characterized by a hyperdivergent facial pattern, and presented a skeletal30,31 asymmetric gummy smile, caused by excessive vertical maxillary growth due to a canted occlusal plane. Also, a slight mandibular deviation was found prior to treatment. In adults, this combination of problems generally requires orthognathic surgery,32,33 which also improves the sagittal position of the mandible. However, since the child was 14 years old—and after carefully balancing the costs and risks—the parents decided not to pursue that option at that time, although they were warned that if the result was not satisfactory, the child would be observed until he had finished growing so that a combined surgical-orthodontic course of treatment could be initiated. The satisfactory outcome of the treatment we selected leads us to think that this will not be necessary.

For this patient, orthodontic treatment reinforced by skeletal anchorage was used to resolve the asymmetric gummy smile caused by the canted occlusal plane and the slight mandibular deviation. Thus, skeletal anchorage had a twofold objective since it had been previously used to correct the open bite by intrusion of the molars. There are several reports about correcting a canted occlusal plane using miniscrews with and without orthognathic surgery, and miniscrews have also been used to treat a gummy smile in patients with Class II division 1 malocclusion.34 As far as we know, however, there are no reports of miniscrews being used to treat both a canted occlusal plane and an asymmetric gummy smile.

The biomechanical system we developed worked in two different phases: superior intrusion and inferior extrusion with total superior vertical anchorage. For the first stage of differential left side intrusion, the right-side miniscrews were inactivated by replacing the coils with 0.012-inch steel ties. On the left side, posterior intrusion was maintained with the coils, while a 0.017 × 0 .025-inch TMA segmental archwire joining the two miniscrews together effected the anterior intrusion. In this way, the increased anchorage unit applied a heavier, more constant and continuous force to the anterior sector, with minimal loss of reciprocal force in the posterior sector. The archwire is easy to bend and the system as a whole easy to apply. The only precaution is that the miniscrew holes should be aligned before the wire is inserted.

In the second stage, once superior left intrusion has been achieved, it is necessary to convert the superior left side into one anchorage unit. So, the earlier segmental archwire must be replaced with 0.017 × 0.025-inch TMA segmental archwire, bent 90°, as before, but inactive and interproximally tied to join all the teeth on the superior left side into a single anchorage unit and proceed to inferior extrusion with vertical elastics. The use of elastics requires the cooperation of the patient, and this is the main disadvantage of the biomechanical system. Other types of miniscrew placement in the inferior arch, such as the rhythmic wire system,34 can solve this problem, although the costs and risks of another miniscrew insertion vs cooperation in using elastics were weighed by both parents and child, and they decided on the latter.

The total treatment outcome using these biomechanics was satisfactory, both intraorally and extraorally. However, in spite of the improvement to the patient's profile, the mandible remained retrusive, although residual mandibular growth is to be expected in male patients of this age.

CONCLUSIONS

Miniscrews provided effective bone anchorage and the satisfactory correction of an open bite and canted occlusal plane with an asymmetric gummy smile in a 14-year-old male patient with Class II malocclusion.

The new biomechanical joined-miniscrew system could become a new treatment strategy for increasing bone anchorage with several purposes.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cinsar A, Alagha AR, Akyalçin S. Skeletal open bite correction with rapid molar intruder appliance in growing individuals. Angle Orthod. 2007;77:632–639. doi: 10.2319/071406-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cangialosi TJ. Skeletal morphologic features of anterior open bite. Am J Orthod. 1984;85:28–36. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(84)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takeuchi M, Tanaka E, Nonoyama D, Aoyama J, Tanne K. An adult case of skeletal open bite with a severely narrowed maxillary dental arch. Angle Orthod. 2002;72:362–370. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2002)072<0362:AACOSO>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nielsen IL. Vertical malocclusions: etiology, development, diagnosis and some aspects of treatment. Angle Orthod. 1991;61:247–260. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1991)061<0247:VMEDDA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buschang PH, Sankey W, English JD. Early treatment of hyperdivergent open-bite malocclusions. Semin Orthod. 2002;8:130–140. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saito I, Yamaki M, Hanada K. Nonsurgical treatment of adult open bite using edgewise appliance combined with high-pull headgear and Class III elastics. Angle Orthod. 2005;75:277–283. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2005)075<0273:NTOAOB>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts WE, Engen DW, Schneider PM, Hohlt WF. Implant-anchored orthodontics for partially edentulous malocclusions in children and adults. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004;126:302–304. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sherwood KH, Burch JG, Thompson WJ. Closing anterior open bites by intruding molars with titanium miniplate anchorage. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2002;122:593–600. doi: 10.1067/mod.2002.128641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wehrbein H, Merz BR. Aspects of the use of endosseous palatal implants in orthodontic therapy. J Esthet Dent. 1998;10:315–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.1998.tb00510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JS, Kim DH, Park YC, Kyung SH, Kim TK. The efficient use of midpalatal miniscrew implants. Angle Orthod. 2004;74:711–714. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2004)074<0711:TEUOMM>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park YC, Lee SY, Kim DH, Jee SH. Intrusion of posterior teeth using mini-screw implants. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;123:690–694. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(03)00047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deguchi T, Takano-Yamamoto T, Kanomi R, Hartsfield JK, Roberts WE, Garetto LP. The use of small titanium screws for orthodontic anchorage. J Dent Res. 2003;82:377–381. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim TW, Kim H, Lee SJ. Correction of deep overbite and gummy smile by using a mini-implant with a segmented wire in a growing Class II Division 2 patient. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;130:676–685. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corbridge JK, Campbell PM, Taylor R, Ceen RF, Buschang PH. Transverse dentoalveolar changes after slow maxillary expansion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;140:317–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2010.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith T, Ghoneima A, Stewart K, et al. Three-dimensional computed tomography analysis of airway volume changes after rapid maxillary expansion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2012;141:618–626. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oliveira De Felippe NL, Da Silveira AC, Viana G, Kusnoto B, Smith B, Evans CA. Relationship between rapid maxillary expansion and nasal cavity size and airway resistance: short- and long-term effects. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;134:370–382. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wertz RA. Skeletal and dental changes accompanying rapid midpalatal suture opening. Am J Orthod. 1970;58:41–66. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(70)90127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wertz R, Dreskin M. Midpalatal suture opening: a normative study. Am J Orthod. 1977;71:367–381. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(77)90241-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung CH, Font B. Skeletal and dental changes in the sagittal, vertical, and transverse dimensions after rapid palatal expansion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004;126:569–575. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2003.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lineberger MW, McNamara JA, Baccetti T, Herberger T, Franchi L. Effects of rapid maxillary expansion in hyperdivergent patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2012;142:60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2012.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu R, Xiaoqing M, Wamalwa P, Zou SJ. Nonsurgical treatment of an adult patient with bilateral posterior crossbite. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;140:106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teuscher U. A growth-related concept for skeletal class II treatment. Am J Orthod. 1978;74:258–275. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(78)90202-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weissheimer A, de Menezes LM, Mezomo M, Dias DM, de Lima EM, Rizzatto SM. Immediate effects of rapid maxillary expansion with Haas-type and hyrax-type expanders: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;140:366–376. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2010.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuroda S, Sakai Y, Tamamura N, Deguchi T, Takano-Yamamoto T. Treatment of severe anterior open bite with skeletal anchorage in adults: comparison with orthognathic surgery outcomes. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;132:599–605. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ng CS, Wong WK, Hagg U. Orthodontic treatment of anterior open bite. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2008;18:78–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2007.00877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Küçükkeles N, Acar A, Demirkaya AA, Evrenol B, Enacar A. Cephalometric evaluation of open bite treatment with NiTi arch wires and anterior elastics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1999;116:555–562. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(99)70189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sugawara J, Baik UB, Umemori M, et al. et al. Treatment and posttreatment dentoalveolar changes following intrusion of mandibular molars with application of a skeletal anchorage system (SAS) for open bite correction. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 2002;17:243–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deguchi T, Kurosaka H, Oikawa H, et al. Comparison of orthodontic treatment outcomes in adults with skeletal open bite between conventional edgewise treatment and implant-anchored orthodontics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;139:S60–S68. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xun C, Zeng X, Wang X. Microscrew anchorage in skeletal anterior open-bite treatment. Angle Orthod. 2007;77:47–56. doi: 10.2319/010906-14R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim TW, Freitas BV. Orthodontic treatment of gummy smile by using mini-implants (part I): treatment of vertical growth of upper anterior dentoalveolar complex. Dental Press J Orthod. 2010;15:42.e1–e9. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silberberg N, Goldstein M, Smidt A. Excessive gingival display—etiology, diagnosis, and treatment modalities. Quintessence Int. 2009;40:809–818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Proffit WR, White RP, Jr, Sarver DM. Contemporary Treatment of Dentofacial Deformity. St Louis, Mo: Mosby; 2003. pp. 111, 500–506. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kokich V. Esthetic and anterior tooth position: an orthodontic perspective. Part II: vertical position. J Esthet Dent. 1993;5:200–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.1993.tb00781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shu R, Huang L, Bai D. Adult Class II Division 1 patient with severe gummy smile treated with temporary anchorage devices. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;140:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]