Abstract

Objectives:

To examine factors associated with treatment outcome satisfaction in a group of adolescent patients.

Materials and Methods:

One hundred and twenty patients (60 girls and 60 boys; mean age, 14.3 years; standard deviation [SD], 1.73 years) were consecutively recruited. The inclusion criteria for all patients were as follows: adolescents with a permanent dentition in need of orthodontic treatment and a treatment plan involving extractions (two or four premolars) followed by fixed appliances in both jaws. Questionnaire 1, concerning treatment motivation and expectations, was assessed prior to treatment start. Questionnaire 2 was assessed after active treatment and included questions about satisfaction with treatment outcome, quality of care and attention, and perceived pain and discomfort during active treatment.

Results:

One hundred and ten patients completed the trial (54 boys and 56 girls; mean age, 16.9 years; SD, 1.78 years). Median values for satisfaction with treatment outcome were generally high. There was a clear correlation (P ≤ .001) between satisfaction with treatment outcome and patients' perception of how well they had been informed and cared for during treatment. Pain and discomfort during treatment also strongly affected treatment satisfaction. Sex, treatment time, and Peer Assessment Rating index pre- and posttreatment as well as expectations for future treatment showed no correlation with treatment satisfaction.

Conclusions:

Care and attention was the variable showing the highest correlation with satisfaction with treatment outcome. Patients' perceptions of pain and discomfort during treatment had an overall negative correlation with treatment satisfaction. Satisfaction with treatment outcome is a complex issue and requires further exploration in future research.

Keywords: Adolescents, Orthodontic treatment, Questionnaire, Treatment outcome satisfaction

INTRODUCTION

The number of adolescents receiving orthodontic treatment worldwide has increased considerably, and as a consequence, different techniques and morphological treatment results have frequently been studied. Nonetheless, exceptionally few research projects have looked at patient satisfaction with treatment outcome and the factors contributing to satisfaction. Levels of patient satisfaction in previous studies range between 34%1 and 95%,2 and one likely reason for this wide range is the difficulty associated with finding relevant tools that reflect patient satisfaction and health benefits. The fact that different questionnaires and methods of statistical analysis have been used makes cross-study comparisons complicated.

We know that girls are more concerned about their malocclusions than are boys and that they more often ask for treatment,3,4 but thus far no correlations have been found between sex and satisfaction with treatment outcome. Correlations between treatment satisfaction and other background factors such as age, pretreatment need, severity of malocclusion, and objective treatment outcome have also not been found.1,5 Previous studies,6 however, have revealed correlations between personality traits and treatment satisfaction, such that higher neuroticism scores were associated with lower levels of satisfaction. According to several previous articles,7–9 quality of care and attention (ie, to treat patients with respect and include them in treatment discussions) positively affects satisfaction with treatment.

A systematic review10 regarding the long-time stability of orthodontic treatment and patient satisfaction concluded that this question had only been sparsely covered in the literature and that most of the articles were lacking in scientific evidence. No conclusions could therefore be made about long-term treatment outcome satisfaction.

The aim of the present study was to identify patient and treatment factors associated with patient satisfaction in a group of adolescent patients. Specifically, background factors (such as age, sex, treatment time, objective treatment outcome, etc), motivation and expectations prior to treatment, experiences of pain and discomfort during treatment, and quality of care and attention were of interest. It was hypothesized that there will be significant correlations among treatment outcome satisfaction and treatment time, quality of treatment, and low levels of pain and discomfort.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

One hundred and twenty patients (60 girls and 60 boys; mean age, 14.3 years; standard deviation [SD], 1.73 years) were consecutively recruited from the Orthodontic Clinic at the Public Dental Service, Gävleborg County Council, Gävle, Sweden. The inclusion criteria for all patients were as follows: adolescents with a permanent dentition in need of orthodontic treatment and a treatment plan involving premolar extractions (two or four bicuspids) followed by fixed appliances in both jaws and additional anchorage on the maxillary molars. Patients with experiences from other dental care systems or patients with previous orthodontic treatment were excluded, as it was important to avoid bias resulting from earlier dental care. The ethics committee of Uppsala University (Uppsala, Sweden), which follows the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, approved the informed consent form and the study protocol.

All patients were treated using a standard straight-wire technique11 with a 0.022-inch slot size designed for continuous light forces (Victory Series, 3M Unitek, Monrovia, Calif). The recommended arch-wire sequence was as follows: 0.016-inch heat-activated nickel-titanium (HANT), 0.018-inch stainless steel (SS), 0.019- × 0.025-inch HANT, and, finally, 0.019- × 0.025-inch SS. Leveling/aligning was achieved with lace-back ligatures, and space closure was carried out using active tie-backs.

In order to avoid treatment bias, a strict study protocol was followed for all patients with an inter-appointment time of 6 weeks. However, since anchorage capacity was the primary outcome measure in a previously published randomized controlled trial (RCT),12 additional anchorage on the maxillary molars was not the same for all patients. The anchorage systems in question were skeletal anchorage (placed in the anterior part of the palate), headgear, and a transpalatal bar.

During the study, all patients received a recommendation to use nonprescription analgesics at their own discretion. Two experienced orthodontists performed the treatments on all patients. One orthodontist, not involved in the study and blind to patient and treatment stage, assessed all study casts using the Peer Assessment Rating (PAR) index.13

Outcome Measures

The main outcome measures to be assessed in the present study were as follows:

Correlation between background factors (such as age, sex, treatment time, overjet, crowding, and treatment outcome) and treatment satisfaction;

Correlation between pretreatment motivation and expectations and treatment satisfaction;

Correlation between perceived pain and discomfort during treatment and treatment satisfaction; and

Correlation between quality of care and attention and treatment satisfaction.

Questionnaires

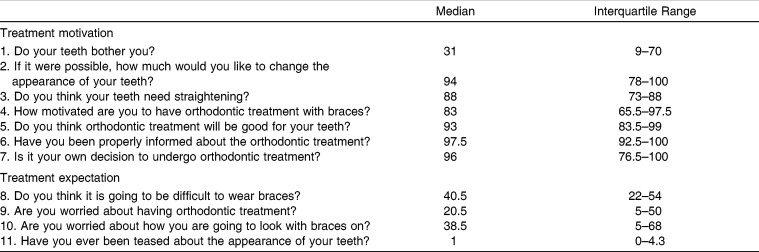

Self-report items from questionnaires previously found to be reliable and valid were used.14 Questionnaire 1 was administrated prior to treatment start and included 11 questions concerning treatment motivation and expectations. All questions were graded on a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) with the end phrases “not at all” and “very much.” The questions, including median values and interquartile range, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Questionnaire Concerning Treatment Motivation and Expectations Assessed on a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) Prior to Treatment Start

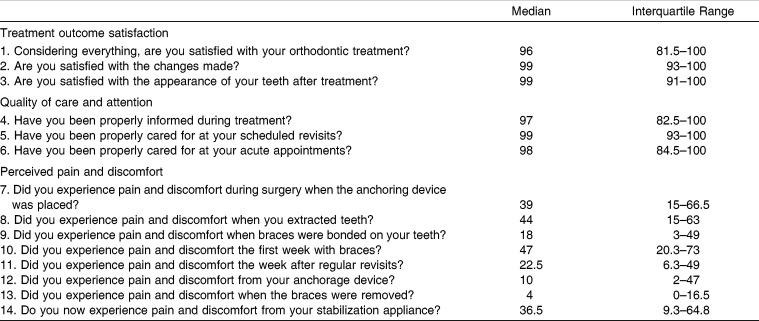

Questionnaire 2 was administrated after active treatment at the first rescheduled visit in the retention phase (after 6 weeks) and included three questions concerning satisfaction with treatment outcome graded on a VAS with the end phrases “not at all” and “very much,” three questions about general quality of care and attention with the end phrases “not at all” and “very much,” and eight questions about perceived pain and discomfort during active treatment with the end phrases “not at all” and “worst imaginable.” The questions, including median values and interquartile range, are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Questionnaire Concerning Satisfaction with Treatment Outcome, Quality of Care and Attention, and Perceived Pain and Discomfort During Treatment

Statistical Analysis

Means and SDs were calculated for age, treatment time, and PAR index scores. Median and interquartile range were calculated for variables assessed on a VAS (ordinal data). Differences in treatment satisfaction between boys and girls, between patients with different anchorage systems, and between patients with different treating orthodontists were tested using the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney tests. For assessments of the correlation between patient satisfaction and all other variables, the Spearman rank correlation was utilized. The level of statistical significance was set at P < .05. Twenty randomly selected study casts were assessed twice for PAR index scores. No significant mean differences between the two series were found using paired t-tests.

RESULTS

One hundred and ten patients completed the trial, 54 boys and 56 girls (mean age, 16.9 years; SD, 1.78 years). Six patients never started orthodontic treatment, one patient dropped out of the trial after leveling/aligning due to poor oral hygiene, and three patients did not complete Questionnaire 2. The response rate for each item varied between 90% and 100%. Treatment time was, on average, 25.3 months (SD, 5.73 months), and PAR index scores improved by 88% during treatment. The mean pretreatment PAR index score was 38, compared to a score of 5 posttreatment.

Type of Anchorage

All patients followed the same study protocol but had different anchorage (skeletal anchorage, headgear, or transpalatal bar) on the maxillary molars. There were no significant differences between type of anchorage and overall satisfaction with orthodontic treatment (P = .951), satisfaction with changes made (P = .756), and satisfaction with the appearance of the teeth (P = .383). In this respect, the patients could therefore be considered to form one homogeneous group.

Background Factors

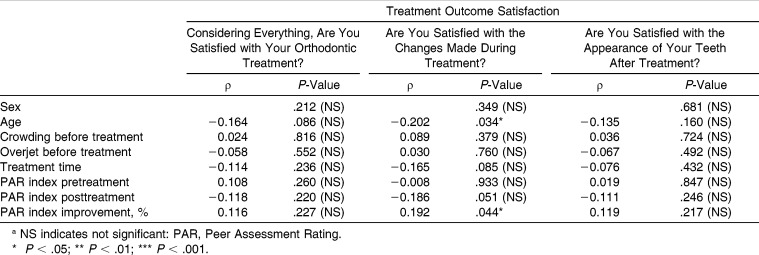

Age, sex, treatment time, pre- and posttreatment PAR index scores, overjet, and crowding pretreatment were generally not correlated with treatment outcome satisfaction. However, there was a small, statistically significant correlation between satisfaction with changes made and young age (P = .034) and satisfaction with changes made and PAR index improvement during treatment (P = .044) (Table 3). There was also no difference in satisfaction between patients with different treating orthodontists.

Table 3.

Correlations Between Treatment Outcome Satisfaction and Background Factorsa

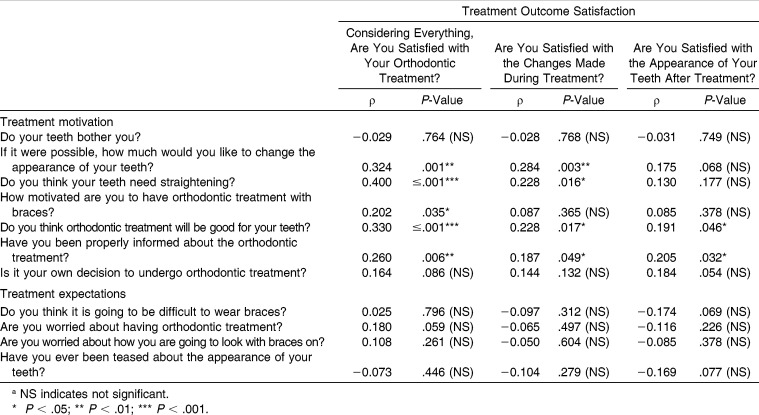

Treatment Motivation and Expectations

There was a tendency toward significant correlations between treatment motivation and overall satisfaction with treatment (Table 4), although correlations between treatment motivation and satisfaction with changes made and satisfaction with one's appearance posttreatment were more fragmented. No correlation was found between the patient's own decision to start treatment and satisfaction with treatment outcome. Expectations and worries for future treatment did not correlate with treatment satisfaction (Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlations Between Treatment Outcome Satisfaction and Motivation and Expectations Prior to Treatmenta

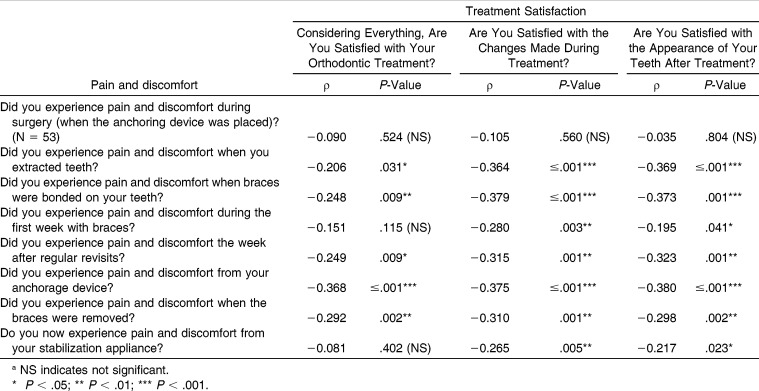

Perceived Pain and Discomfort

There was an overall negative significant correlation between the patients' perceptions of pain and discomfort during treatment and satisfaction with treatment (Table 5), although pain and discomfort during the first week with braces (P = .115) and pain and discomfort from the stabilization appliance (P = .402) did not correlate with overall treatment satisfaction. Pain and discomfort during surgical placement of a skeletal anchoring device did not correlate with any of the treatment satisfaction items.

Table 5.

Correlations Between Treatment Outcome Satisfaction and Perceived Pain and Discomfort During Treatmenta

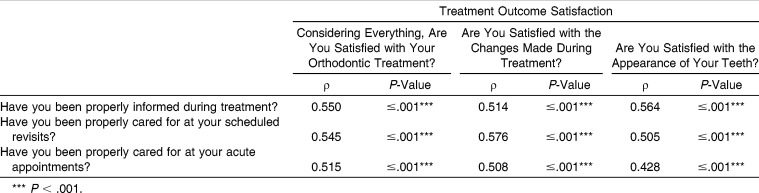

Quality of Care and Attention

There was a strong correlation between treatment satisfaction and patients' ratings of how well they had been informed during treatment and how well they had been cared for during scheduled and acute visits (Table 6). There were no differences between the two treating orthodontists regarding this factor.

Table 6.

Correlations Between Treatment Outcome Satisfaction and Quality of Care and Attention

DISCUSSION

In the present study, quality of care and attention was the factor most highly correlated with treatment outcome satisfaction. This is also in agreement with the findings of previous studies7–9 in which quality of care and attention has been described in terms of patients being well informed, included in discussions, and treated with respect.

The most important and surprising finding in the present study, however, was that the patients' general perceptions of pain and discomfort during treatment were negatively correlated with treatment outcome satisfaction. The more perceived pain and discomfort was associated with procedures or treatment phases, the less satisfaction there was with regard to treatment outcome. This is new information, and, therefore, a thorough analysis is required.

A previous study,15 in which pain and discomfort associated with premolar extractions and palatal placement of a skeletal anchorage device were evaluated, found that these two procedures were fairly comparable. When the patients evaluated their memory of perceived pain during treatment, median values in the present study (Questionnaire 2) indicated the same ratio between premolar extraction and surgical placement of an anchorage device (Medians 44 and 39, respectively), but the two procedures affected treatment satisfaction in different ways. While pain and discomfort associated with premolar extractions correlated with lower treatment satisfaction, pain and discomfort from surgical placement of the anchoring device showed no such correlation. One possible explanation could be that the patients who were randomized to receive a skeletal anchorage device felt chosen and special and therefore associated perceived pain and discomfort with something relatively positive and necessary for their treatment outcome (the Hawthorne effect).

Pain and discomfort in connection with bonding, debonding, and experiences the first week with braces and during the weeks following appointments were all negatively correlated with treatment satisfaction, though to different degrees. The weakest (although significant) correlation was seen between pain and discomfort the first week with braces and treatment satisfaction, which is interesting because there is general agreement that the level of pain is highest on days 2 through 4 after bonding.16–18

Because almost all patients wore a thermoplastic retainer (Raintree Essix, Los Angeles, Calif) as a retention device in the upper jaw, it is logical that the patients experienced some pain and discomfort. This type of retention is semielastic and can therefore cause tension on newly debonded teeth, which could explain the effect on treatment satisfaction. The median, however, was 36.5, which is quite high, and we can therefore assume that this pain and discomfort were unexpected and also not acceptable.

However, the most interesting question regarding pain and discomfort and its correlation with treatment satisfaction is “What comes first?” Does perception of pain and discomfort dominate patients' overall experience of orthodontic treatment and therefore influence satisfaction with treatment outcome, or does dissatisfaction with treatment outcome lead to an overestimation of the degree of pain and discomfort? Another plausible theory may be that because quality of care and attention was the most important issue for patients, there is a possibility that information about pain and discomfort is generally unsatisfactory. This may also explain the difference in the correlation between surgical placement of an anchoring device and treatment outcome satisfaction and that between premolar extraction and treatment outcome satisfaction, where one possible assumption may be that the information about the surgery was more thorough and detailed than the information about premolar extraction, which is usually considered a routine procedure.

Compared to boys, girls are generally more dissatisfied with their dental appearance3,4,19 and perceive more need for orthodontic treatment, but in the present study there were no correlations between sex and satisfaction with treatment outcome, which is also in agreement with the findings of other studies.1,20 Despite the fact that the age distribution in the present study is rather narrow, there was a weak but significant correlation between satisfaction with changes made and young age. This indication of a correlation between age and satisfaction with treatment is interesting to consider for future research in both children and adults. Other background factors, such as treatment time, overjet, crowding, and PAR index scores, showed no correlations with treatment outcome satisfaction, which is also in accordance with other studies.1,9

Motivation to undergo treatment showed correlations with treatment satisfaction, which is also in agreement with the findings of Anderson et al.,21 who concluded that the more focused the patient was prior to treatment, the more satisfied he/she was with the outcome.

One of the present study's shortcomings is that the questionnaires cover several domains but with only a few questions targeting each domain, which means that some interesting issues are dealt with only superficially. Another possible shortcoming is that the patients' perceptions of pain and discomfort were assessed retrospectively and not with several questionnaires in real time. The intention was, however, to explore the patients' experiences of orthodontic treatment, the different steps and different phases, and the retrospective approach provides information on how the patients remember their treatment and also on how they would describe it to others.

The reliability and validity of a questionnaire are important criteria for making generalizations based on results. The majority of the questions used in the present study were taken from a questionnaire that had been used in a previous study,14 in which the reliability and validity were found to be “good” to “excellent.” The age distribution in the present study was also similar to that in other studies of adolescents undergoing orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances. All patients followed the same standardized treatment protocol, but with different anchorage on the maxillary first molars, which was tested for correlations to treatment satisfaction and found to be negative. In addition, selection bias was avoided because consecutive patients were enrolled into the study.

PAR index score improvement was 88% in the present study, which is considered to be a high standard of treatment result.21 Median values for questions about patients' satisfaction with treatment were consequently high and had limited spread (Table 2), which automatically led to difficulties in detecting strong correlations. Despite this, significant correlations were found, indicating that the sample size was sufficient but that correlations would have been improved with a larger sample size. However, although median values were high, indicating satisfied patients, it is important to understand that not all patients are satisfied with their orthodontic treatment and that we need to better understand why. In future research long-term aspects must also be considered.

CONCLUSIONS

Quality of care and attention was the factor most highly correlated with treatment outcome satisfaction.

Patients' experiences of pain and discomfort during treatment were negatively correlated with treatment outcome satisfaction.

Satisfaction with treatment outcome is a complex issue and requires further exploration in future research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Omiri MK, Abu Alhaija ES. Factors affecting patient satisfaction after orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod. 2006;76:422–431. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2006)076[0422:FAPSAO]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birkeland K, Böe OE, Wisth PJ. Relationship between occlusion and satisfaction with dental appearance in orthodontically treated and untreated groups—a longitudinal study. Eur J Orthod. 2000;22:509–518. doi: 10.1093/ejo/22.5.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergius M, Kiliaridis S, Berggren U. Pain in orthodontics—a review and discussion of the literature. J Orofac Orthop/Fortschr Kieferorthop. 2000;61:125–137. doi: 10.1007/BF01300354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheats RD, McGorray SP, Keeling SD, Wheeler TT, King GJ. Occlusal traits and perception of orthodontic need in eighth grade students. Angle Orthod. 1998;68:107–114. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1998)068<0107:OTAPOO>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maia NG, Normando D, Maia FA, Ferreira MA, do Socorra Costa Feitosa Alves M. Factors associated with long-term patient satisfaction. Angle Orthod. 2010;80:1155–1158. doi: 10.2319/120909-708.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barker MJ, Thomson WM, Pouton R. Personality traits in adolescence and satisfaction with orthodontic treatment in young adulthood. Aust J Orthod. 2005;21:87–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bos A, Hoogstraten J, Prahl-Andersen B. Attitudes towards orthodontic treatment: a comparison of treated and untreated subjects. Eur J Orthod. 2005;27:148–154. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjh071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McNair A, Gardiner P, Sandy JR, Williams AC. A qualitative study to develop a tool to examine patients' perceptions of NHS orthodontic treatment. J Orthod. 2006;33:97–106. doi: 10.1179/146531205225021483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keles F, Bos A. Satisfaction with orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod. 2013;83:507–511. doi: 10.2319/092112-754.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bondemark L, Holm AK, Hansen K, et al. Long-term stability of orthodontic treatment and patient satisfaction. Angle Orthod. 2007;77:181–191. doi: 10.2319/011006-16R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLaughlin RP, Bennet J, Trevisi HJ. St. Louis, MO: Mosby International Ltd; 2001. Systemized orthodontic treatment mechanics. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feldmann I, Bondemark L. Anchorage capacity of osseointegrated and conventional anchorage systems—a randomized controlled trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;133:339.e19–339.e28. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richmond S, Shaw WC, Roberts CT, Andrews M. The PAR Index (Peer Assessments Rating): methods to determine outcome of orthodontic treatment in terms of improvement and standards. Eur J Orthod. 1992;14:180–187. doi: 10.1093/ejo/14.3.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feldmann I, List T, John M, Bondemark L. Reliability of a questionnaire assessing experiences of orthodontic treatment in adolescents. Angle Orthod. 2007;77:311–317. doi: 10.2319/0003-3219(2007)077[0311:ROAQAE]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feldmann I, List T, Feldmann H, Bondemark L. Pain intensity and discomfort following surgical installation of orthodontic anchoring units and premolar extraction. Angle Orthod. 2007;77:578–585. doi: 10.2319/062506-257.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scheurer PA, Firestone AR, Burgin WB. Perception of pain as a result of orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances. Eur J Orthod. 1996;18:349–357. doi: 10.1093/ejo/18.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller KB, McGorray SP, Womack R, et al. A comparison of treatment impacts between Invisalign aligner and fixed appliance therapy during the first week of treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;131:302.e1–302.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldmann I, List T, Bondemark L. Orthodontic anchoring techniques and its influence on pain, discomfort and jaw function—a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Orthod. 2012;34:102–108. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjq171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaw WC. Factors influencing the desire for orthodontic treatment. Eur J Orthod. 1981;3:151–162. doi: 10.1093/ejo/3.3.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eberting JJ, Straja SR, Tuncay OC. Treatment time, outcome and patient satisfaction comparisons of Damon and conventional brackets. Clin Orthod Res. 2001;4:228–234. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0544.2001.40407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson LE, Arruda A, Inglehart MR. Adolescent patients' treatment motivation and satisfaction with orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod. 2009;79:821–827. doi: 10.2319/120708-613.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]