Abstract

Purpose

Hope has been identified as a protective factor that contributes to achieving a better quality to life, especially in patients with chronic disease. The purpose of this review was to synthesize current knowledge about the relationship between hope and quality of life among adolescents living with chronic illnesses.

Methods

We searched major English-language databases (PsycINFO, PubMed, and CINAHL) for studies from January 1, 2002 to July 12, 2019. Studies were included if they provided data on hope and its relationship with quality of life among adolescents with chronic diseases.

Results

In total, five articles were selected from the 336 studies that were retrieved. All five studies reported a positive correlation between hope and quality of life, such that people with a higher level of hope had a better quality of life. Hope was found to have direct and indirect effects on quality of life in adolescents with chronic diseases.

Conclusion

Healthcare professionals should make more efforts to enhance hope in adolescents with chronic diseases in order to improve their quality of life. Future studies exploring how hope develops in adolescents with chronic diseases and the long-term impact of hope on quality of life are necessary.

Keywords: Adolescent, Chronic disease, Hope, Quality of life, Review

INTRODUCTION

More adolescents with chronic illnesses are living longer than was previously the case due to advances in scientific knowledge and medical technology. However, being diagnosed with a chronic disease could have long-term and ongoing impacts on adolescents' psychological, socio-spiritual, and emotional function [1]. Studies have reported that chronic diseases affected sexual maturity in adolescents, disturbed school life, and led to the development of mental health issues [2]. Adolescents with chronic illnesses experienced a higher dependency on family, as well as ambivalence and uncertainty about the future [3]. Evidence on adults with chronic diseases, such as HIV and cancer, has shown that hope is an important therapeutic factor in healing from and surviving illness [4,5].

Hope has been considered to be a positive attribute for achieving a better quality to life, especially in patients with chronic disease [6]. Previous research has reported that hope was associated with health indicators, such as coping, self-esteem, and quality of life [7-9]. It has been proposed that hope should be considered to be a central component of nursing responsibilities, with the goal of maintaining and improving patients' quality of life. Despite extensive research, there are still significant gaps in researchers' understanding of the association between hope and quality of life among chronically ill adolescents. To date, only two integrative reviews of research addressing hope in adolescents have been published [10,11]. Obtaining further knowledge of the association between hope and quality of life in adolescents with chronic illnesses will provide better insights into ways of optimizing care for those working with chronically ill adolescent patients. The purpose of this review was to synthesize current knowledge on the relationship between hope and quality of life among adolescents living with chronic illnesses.

METHODS

1. Literature Search and Retrieval Processes

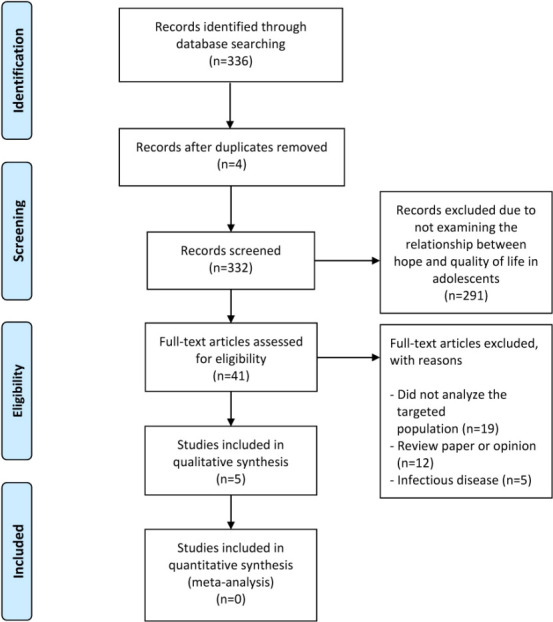

Relevant studies were identified through searches of PsycINFO, PubMed, and CINAHL for citations from January 1, 2002 to July 12, 2019. The search aimed to identify studies reporting data on the relationship between hope and quality of life in adolescents with chronic diseases. The key words used in the search were as follows: “hope,” “hopeful,” “hopefulness,” “quality of life,” “QOL,” “health-related quality of life,” “HRQOL,” and “adolescent,” “young adult,” and “ chronic disease.” Some word truncations were used according to each database. The search strategy is shown in Figure 1. A search on Google Scholar was also conducted, but no new findings resulted. Reference lists were also scanned by hand for all known articles.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The following inclusion criteria were applied: (1) papers in which the participants were adolescents (ranging in age from 10 to 25 years old) diagnosed with a chronic disease (a longterm illness requiring interventions and treatments [11] or cancer) or children with sickle cell disease; and (2) papers that provided data on hope and its relationships with quality of life among adolescents with chronic diseases. The search was limited to articles with the full-text version available in English or Bahasa Indonesia. We excluded papers unrelated to hope and quality of life in adolescents, books, and review papers.

3. Data Extraction

Two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts who has been mutually trained by the senior researched regarding searching articles in different database. In the first stage of the search process, a standard form and guideline were created to summarize the search results, including the title, number of articles included or excluded (and the reason for exclusion), and unclear articles (with the ultimate decision). If there was a disagreement between the two reviewers, the decision was made by discussion with all researchers. In the next stage, information regarding the included studies was obtained using a standard form, including the author, publication year, place of study, study, sample size and technique, instrument, and main findings. All reviewers were provided with specific instructions for data extraction.

4. Quality Appraisal

Quality was independently assessed by two reviewers. Disagreements between the two reviewers were discussed through panel review. Two criteria were used to assess quality (methodological rigor and relevance) using a 2-point scale (high=2 or low=1) [12]. The criteria for appraisal of observational studies included the sampling method, sample size, participants and setting, measurements and validity, the method of statistical analysis, and confounding.

RESULTS

1. Search Results

Figure 1 summarizes the process for searching and selecting the articles. A total of 336 papers were identified in the initial search. Forty-one papers were identified as potential articles for further screening based on the inclusion criteria. Finally, five papers that met the inclusion criteria were included in this review.

2. Characteristics of Included Studies

These five papers evaluated the relationship between hope and quality of life in adolescents with different types of chronic diseases, in various countries, languages, and settings. A summary of each of the five articles is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Included Studies (N=5)

| Authors, year | Country | Study design and setting | Sample | Instrument | Results | Rigor/relevance (H or L) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim, Kim, & Kim, 2018 | South Korea | · | Cross-sectional, descriptive correlational design | · | N=220 (aged 10~18 years) diagnosed with a chronic disease at least 6 months and receiving medical therapy | · | Hope: the Herth Hope Index | · | Hope showed a significant positive correlation with quality of life (r=.41; p<.001) | H/H |

| · | Hospital for outpatient care | · | A convenience sample | · | Quality of life: the PedsQLTM 4.0 Generic Core Scale | · | Hope had significant direct effects and total effects on quality of life | |||

| Martins et al., 2018 | Portugal | · | Cross-sectional | · | N=211 children and adolescents diagnosed with malignant cancer, onor off-treatment status— < 5 years since the end of treatment; and without developmental disorders (e.g., Down syndrome) | · | The Children's Hope Scale | · | Children's hope was positively associated with quality of life | H/H |

| · | The oncology wards of two Portuguese public hospitals | · | 99.5% response rate | · | Short version of the DCGM-12 self-report questionnaire | · | Anxiety mediated the relation between hope and quality of life (point estimate=0.10; CI=0.06~0.16); the R2 for QOL was 0.24 in each group. | |||

| Rosenberg et al., 2018 | United States | · | Multi-center, prospective, longitudinal, mixed-methods study | · | N=37 | · | Relational hope, namely sub-scores for "agency" (capacity to create a path to one's objectives) and "pathway" (capacity to undertake and sustain actions to achieve those objectives) | · | Hope alone was associated with later QOL (Beta=0.3, 95% CI=0.10~0.60, p=.020) | H/H |

| · | Two places (Seattle Children’s Hospital and Dana-Farber/Boston Children's Hospital) | · | Ages 14~25 with newly diagnosed with non-central nervous cancer and under chemotherapy | · | Cancer-related QOL (PedsQL 3.0 Cancer Module) | |||||

| Santos et al., 2015 | Portugal | · | Cross-sectional | · | N=224 (aged 13~20 years) with cancer | · | Portuguese version of the Children's Hope Scale | · | Hope was associated with QOL (95% CI=0.01~0.07, p<.001) | H/H |

| · | Three Portuguese public hospitals | · | N=165 (aged 8~12 years) with cancer | · | Portuguese version of PedsQLTM 3.0 Cancer Module | |||||

| · | Consecutive sampling | |||||||||

| Ziadni et al., 2011 | United States | · | Cross-sectional | · | N=44 (aged 12~18) children with sickle cell disease | · | Children's Hope Scale | · | Family's total annual income was associated with hope (r=.33, p=.043). | H/H |

| · | Marian Anderson Sickle Cell Center at StChristopher's Hospital for Children | · | MPQLQ | · | Higher levels of hope and better QOL were associated with higher adaptive behaviour | |||||

CI=Confidence interval; DCGM=DISABKIDS chronic generic module; H=High; L=Low; MPQLQ= Miami pediatric quality of life questionnaire; PedsQL= Pediatric quality of life; PedsQLTM=Pediatric quality of life inventory; QOL=Quality of life.

Two studies were conducted in the United States, two studies in Portugal, and one study in South Korea. All studies were hospital-based. Four studies were conducted using a cross-sectional design and one study had a prospective design. The majority of studies included participants ranging in age from 10 to 18 years, with a mixture of children and adolescents. The number of participants in the studies ranged from 37 to 224, and most used convenience sampling. Hope was measured using the Children’s Hope Scale [13-15] and the Herth Hope Index [16]. The PedsQLTM 4.0 Generic Core Scale, PedsQL 3.0 Cancer Module, Miami Pediatric Quality of Life Questionnaire, and the short version of the DISABKIDS Chronic Generic Measure self-report questionnaire were used to measure quality of life.

3. Quality of Studies

Quality was analyzed based on the risk of bias in the sampling, sample size, and the use of appropriate analytical methods. All studies had high rigor and high relevance (Table 1).

4. Main Findings

All five studies reported a positive correlation between hope and quality of life, meaning that people with higher levels of hope had a better quality of life. One study reported that hope had significant direct and indirect effects on quality of life [16], while another study reported that anxiety mediated the relationship between hope and quality of life [13]. One study also reported that hope was a mediator in the relationship between quality of life and adaptive behavior [15]. Interestingly, Santos et al. [14] highlighted that as children and parents revealed higher rates of family activities, they also expressed higher family cohesion and higher hope, which was linked to better quality of life.

The main differences in these five articles were as follows. Kim et al. [16] analyzed the relationship between hope and quality of life using the adolescent resilience model as a theoretical framework, which places resilience as a mediator in the relationship between hope and quality of life. Santos et al. [14] explored mutual dyadic correlations of how parental perceptions influence those of children, and conversely. Their study emphasized family rituals as an important aspect of promoting quality of life in pediatric cancer patients, as moderated by hope and family cohesion in regard to parent-child interactions. Ziadni et al. [15] highlighted that higher hope was correlated to better quality of life, and that good adaptive behavior was linked to better health-related quality of life (and viceversa for lower adaptive behavior). In contrast, Martins et al. [13] explored the difference between pediatric cancer patients on and off treatment and revealed that children and adolescents on treatment had higher quality of life compared to those who were off treatment. Hope was positively associated with quality of life, both directly and indirectly via anxiety reduction. In addition, a longitudinal study conducted by Rosenberg et al. [17] found that initial distress predicted future distress and that initial hope predicted future hope. However, only the combination of hope/distress scores predicted future quality of life.

DISCUSSION

This review highlighted that adolescents with chronic diseases who had higher levels of hope had a better quality of life. This study also emphasized that hope functioned as an indirect and direct determinant of quality of life for children and adolescents with chronic illnesses. Quality of life is a widely accepted as an important outcome measure to evaluate the success of treatments and interventions in children or adolescents with chronic diseases. Quality of life is a concept that helps healthcare professionals understand the impact of a disease or a treatment on a patient's life. Adolescents with chronic diseases may suffer from chronic pain, which could affect their quality of life [3]. Hope is a coping strategy that helps individuals face critical conditions during stressful life events [18]. Therefore, hope is considered to be a protective factor that contributes to improving quality of life in adolescents and young adults with cancer [19]. Addressing hope in adolescents with chronic health problems improves their quality of life in all domains, encompassing physical, mental, social, and academic functioning [20]. However, the included studies explored hope in participants with a wide age range, from 8 to 25 years old (i.e., with a mixture of children and adolescents). Therefore, a topic for further research is how hope develops through the stages of adolescence (early, middle, and late), because such a nuanced perspective would help provide tailored interventions to increase hope and to improve quality of life.

Hope has various definitions in health care research, and has been approached from multidimensional perspectives. For adolescents with chronic diseases, hope is not an abstract state of mind, but an important personal capacity to consider one's position and future problems and prepare oneself to cope positively. Only two tools were used to measure hope in the included studies: the Children's Hope Scale and the Herth Hope Index. There are a few choices of hope measurement tools for use in adolescents with chronic diseases, but the operationalization of the concept of hope should continue to be refined to explore the essence of hope in this population. Furthermore, most of the included studies were conducted using a cross-sectional design. However, hope may change depending on the situation; therefore, exploring how hope develops in adolescents through longitudinal follow-up may be needed to explore dynamic changes in hope and its impact on quality of life over time.

The current research should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, publication and selection bias could not be eliminated from this study because the criteria for inclusion were restricted to research published in the English language and Bahasa Indonesia, and it excluded conference papers and off-line publications. In addition, the studies were conducted in developed countries, and few were from Asia and Africa, which may have important differences in health care systems, cultures and beliefs. However, we nonetheless believe that the included studies provide valuable descriptions about hope and its association with quality of life in their respective countries.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this review emphasizes the presence of a positive correlation between hope and quality of life in children and adolescents with chronic disease. Hope was also reported to have direct and indirect relationships with quality of life. Healthcare professionals need to make more efforts to enhance hope in adolescents with chronic diseases in order to improve their quality of life. Future studies should explore the development of hope in adolescents with chronic diseases to provide a better understanding of dynamic changes in hope. In addition, tailored interventions should be developed to increase hope according to adolescents' developmental stages.

Footnotes

No existing or potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Venning A, Eliott J, Wilson A, Kettler L. Understanding young peoples' experience of chronic illness: A systematic review. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare. 2008;6(3):321–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-1609.2008.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borgna-Pignatti C, De Stefano P, Zonta L, Vullo C, De Sanctis V, Melevendi C, et al. Growth and sexual maturation in thalassemia major. The Journal of Pediatrics. 1985;106(1):150–155. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(85)80488-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saällfors C, Fasth A, Hallberg LR. Oscillating between hope and despair - A qualitative study. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2002;28(6):495–505. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2002.00300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herth KA. Development and implementation of a hope intervention program. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2001;28(6):1009–1016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schrank B, Stanghellini G, Slade M. Hope in psychiatry: A review of the literature. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2008;118(6):421–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammer K, Mogensen O, Hall EOC. The meaning of hope in nursing research: A meta-synthesis. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2009;23(3):549–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2008.00635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Folkman S. Stress, coping, and hope. Psycho-Oncology. 2010;19(9):901–908. doi: 10.1002/pon.1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cantrell MA, Lupinacci P. Investigating the determinants of health-related quality of life among childhood cancer survivors. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008;64(1):73–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pipe TB, Kelly A, LeBrun G, Schmidt D, Atherton P, Robinson C. A prospective descriptive study exploring hope, spiritual well-being, and quality of life in hospitalized patients. Medsurg Nursing: Official Journal of the Academy of Medical-Surgical Nurses. 2008;17(4):247–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esteves M, Scoloveno RL, Mahat G, Yarcheski A, Scoloveno MA. An integrative review of adolescent hope. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2013;28(2):105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2012.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griggs S, Walker RK. The role of hope for adolescents with a chronic illness: An integrative review. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2016;31(4):404–421. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;52(5):546–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martins AR, Crespo C, Salvador Á, Santos S, Carona C, Canavarro MC. Does hope matter? Associations among self-reported hope, anxiety, and health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with cancer. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2018;25(1):93–103. doi: 10.1007/s10880-018-9547-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santos S, Crespo C, Canavarro MC, Kazak AE. Family rituals and quality of life in children with cancer and their parents: The role of family cohesion and hope. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2015;40(7):664–671. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsv013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ziadni MS, Patterson CA, Pulgarón ER, Robinson MR, Barakat LP. Health-related quality of life and adaptive behaviors of adolescents with sickle cell disease: Stress processing moderators. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2011;18(4):335–344. doi: 10.1007/s10880-011-9254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim M, Kim K, Kim JS. Impact of resilience on the health-related quality of life of adolescents with a chronic health problem: A structural equation approach. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2019;75(4):801–811. doi: 10.1111/jan.13888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenberg AR, Bradford MC, Bona K, Shaffer ML, Wolfe J, Baker KS, et al. Hope, distress, and later quality of life among adolescent and young adults with cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2018;36(2):137–144. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2017.1382646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Umphrey LR, Sherblom JC. The constitutive relationship of listening to hope, emotional intelligence, stress, and life satisfaction. International Journal of Listening. 2018;32(1):24–48. doi: 10.1080/10904018.2017.1297237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haase JE, Heiney SP, Ruccione KS, Stutzer C. Research triangulation to derive meaning-based quality-of-life theory: Adolescent resilience model and instrument development. International Journal of Cancer. 1999;12:125–131. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(1999)83:12+<125::aid-ijc22>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shoshani A, Mifano K, Czamanski-Cohen J. The effects of the Make a Wish intervention on psychiatric symptoms and healthrelated quality of life of children with cancer: A randomised controlled trial. Quality of Life Research. 2016;25(5):1209–1218. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1148-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]