Abstract

The present study aims to demonstrate how biomodels can be used as teaching tools for surgical techniques and training in a medical residency service.

A case series was carried out in our orthopedics and traumatology outpatient facility using three-dimensional (3D) printing for surgical planning to contribute to the surgical teaching and training of resident physicians. Two cases were selected as examples in the present article.

Biomodels enable a better understanding of the surgery by the surgical team and residents, reducing the surgical time and the risks for the patients.

These models can be a good teaching method to plan reconstructions of total hip arthroplasties, evaluate and predict surgical difficulties, and optimize procedures.

Keywords: arthroplasty, replacement, hip; hip/surgery; printing, three-dimensional; models, anatomic

Introduction

Briefly speaking, fast prototyping is a way to physically reproduce virtual three-dimensional (3D) models using various techniques for the deposition of material layer by layer. 1 This physical deposition in layers enables the creation of a wide range of geometric shapes that would be difficult or even impossible to obtain with conventional industrial techniques, such as machining, which are based on material removal. 2 The technique has proven to be very useful to reproduce living organic structures, including tissues and organs, which do not have perfect shapes (that is, they are regular polyhedra), since their architecture is based on cell growth, an individual process related to several genetic and environmental factors. 3 Because the phenotypic diversity in Homo sapiens is very high, competence regarding the medical praxis occurs by intervention/interaction in countless patients who exhibit heterogeneous anatomical characteristics.

The growing search for excellence in the diagnosis and treatment of musculoskeletal disorders has become a major challenge for orthopedists. As such, new technologies in imaging diagnosis and in the planning of advanced therapies, including repair and reconstructive surgery, must be implemented in the medical practice since the beginning of orthopedic training. 3 Mothes et al. 4 used prototyping to study glenohumeral defects when planning shoulder arthroplasties. In his master's dissertation, Marques 5 tested several prototyping models that could be applied in traumatology for implant planning in osteosynthesis.

In the medical field, prototyping biomodels can be obtained from computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. 4 The technique is widespread in the medical practice and in orthopedic and traumatological surgery, and it has been used to facilitate the understanding of bone deformities and failures. 3 In addition, previous structural knowledge can reduce the surgical time and the risks to the patients. 4

Technique Description

The present technical note aims to demonstrate how fast prototyping (3D printing) can be used as a tool to understand surgical techniques and improve staff training in a medical residency service.

For the clinical cases herein presented, surgical training with fast prototyping models was held. Two steps were required to build 3D models. Initially, CT scans of the patients were requested, and their images were processed using the free software InVesalius (CTI Renato Archer, Campinas, SP, Brazil) and MeshMixer (Autodesk, Inc., San Rafael, CA, US). The biomodels were built with a 3D Cliever (Cliever Tecnologia, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil) printer using polylactic acid (PLA) filament.

Both procedures were performed according to the recommended technique, and then, routinely followed-up by the Orthopedics and Traumatology Service. The surgery was performed using the technique planned during training.

The inclusion criteria were patients with major bone defects and deformities and CT scans suitable for 3D measurements. A 3D printed model was made for each case and then compared with the real situation in loco. The entire procedure was thoroughly described.

In addition, the present study considered medical record data, including pre-, peri- and postoperative parameters, along with an evaluation of the imaging findings and of the printed model. The patients were coded to preserve their anonymity. The present study was submitted and approved by the hospital ethics committee.

Case 1

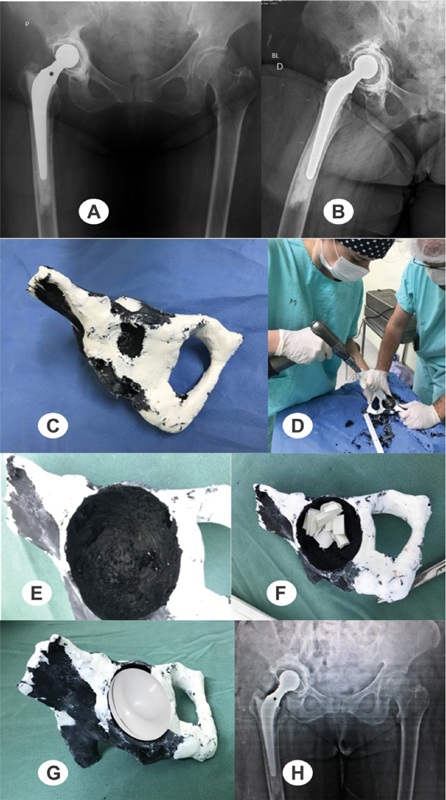

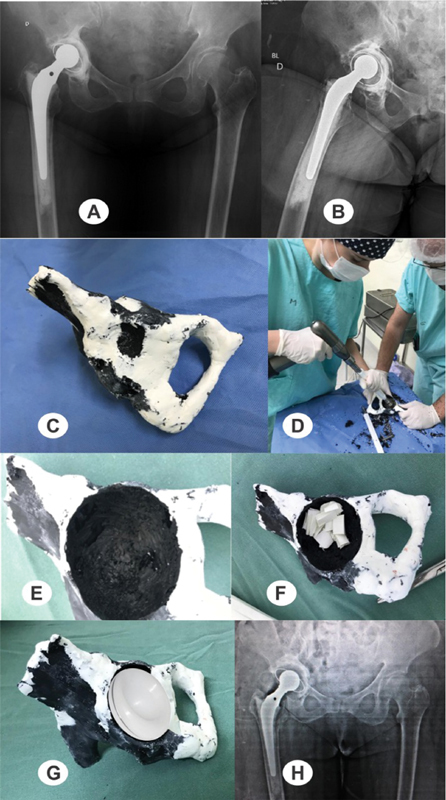

A 77-year-old female patient with a right-sided cemented hip arthroplasty due to primary coxarthrosis. This initial procedure had been performed 17 years ago at our service. The patient complained of pain in the operated hip for 3 years. The outpatient radiological follow-up revealed periacetabular osteolysis, and failure of the acetabular component with loosening and rotation. The femoral component showed no significant changes in comparison to previous imaging studies ( Figure 1A, B ).

Fig. 1.

Preoperative radiographs of the pelvis ( A ) and lateral view of the right hip ( B ) at the time of the review, revealing an important acetabular bone failure with loosening of the components. ( C ) View of the printed prototyping model; ( D ) residents training with prototyping models; ( E ) cavity and ( F ) acetabulum preparation with visualization of the bone defect and its filling with chopped, impacted bone; ( G ) planning of the size and position of the implant; ( H ) postoperative radiograph of the revision of the right total hip arthroplasty.

Figure 1C shows a printed hemipelvis for a better evaluation of the bone defect and for the training of the residents. The diagnostic hypothesis of acetabular failure, probably of aseptic origin, was supported because the patient had no clinical and laboratory signs of infection. As such, revision of the acetabular component was indicated ( Figures 1D, E, F, G ), using chopped bone graft impacted on the acetabular roof and bottom. Figure 1H shows a postoperative pelvic radiograph.

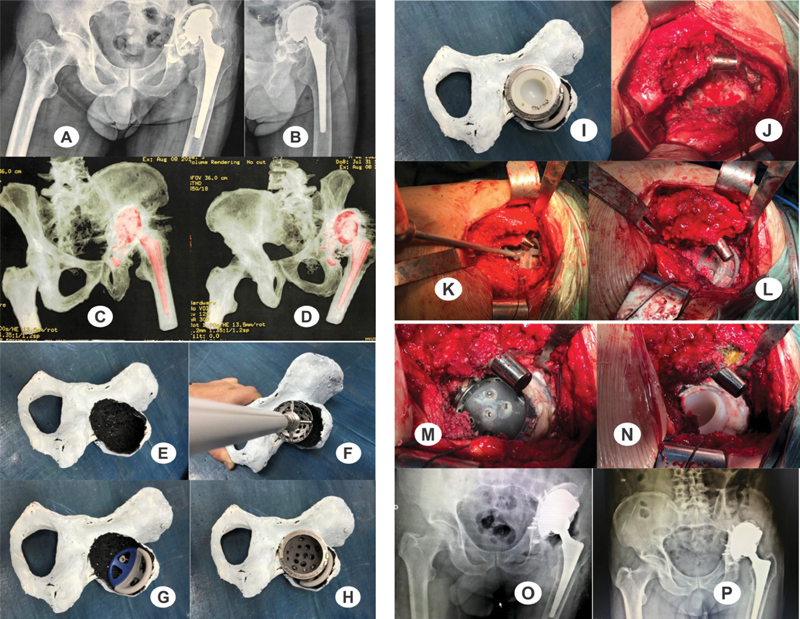

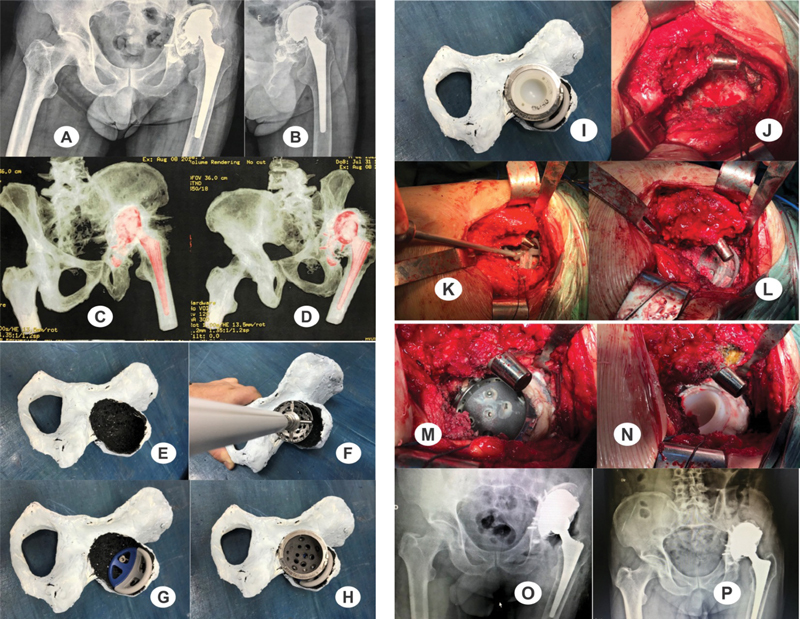

Case 2

A 61-year-old male patient with a history of left-hip arthroplasty performed 18 years ago due to acetabular fracture, with subsequent revision 6 years ago. The patient had reported progressive pain in the left hip associated with significant functional loss for at least 5 years. During this period, the patient consulted with several colleagues who advised on expectant behavior or implant removal, claiming there were no more therapeutic options. Preoperative radiographs revealed that the patient had a total cementless hip prosthesis with a loose acetabular component, extensive acetabular erosion, steel mesh ruptures, and screw fractures ( Figure 2A, B ). There were no significant changes in the femoral component, and the patient did not show clinical or laboratory signs of infection. A CT scan was requested to better assess the bone defect, followed by hip prototyping ( Figures 2C, D, E ). Considering the extensive bone lesion, we initially considered using bone from the Bone Bank, but this service is not available in our city. Next, residents and staff were trained using assemblies with trabecular metal and interspace bone grafting ( Figures 2F, G, H, I ). Given the severity of the injury, we initially considered the two acetabula option proposed by Paprosky, but the circumferences of the cups did not fit properly. Then we thought about a new structural option with two cages and an anchoring system with divergent screws, filled with bone graft, on which the new acetabulum was placed and cemented in the appropriate inclination and anteversion. The surgical procedure occurred exactly as planned, saving a lot of time in a major procedure and with little bleeding ( Figures 2J, K, L, M, N ). The postoperative radiograph was satisfactory ( Figure 2O ), with perfect graft integration and excellent function at a 3-year follow-up ( Figure 2P ). Currently, the patient is asymptomatic and satisfied with the procedure.

Fig. 2.

( A, B ) Preoperative radiographs of the pelvis and lateral view of the left hip; ( C, D ) computed tomography scans; ( E ) visualization of the extensive acetabular lesion; ( F ) study of the situation; ( G ) assembly of a new arrangement with trabeculated metal and study of its anchoring; ( H ) placement of the new acetabulum; ( I ) positioning the cemented polyethylene; ( J ) visualization of the intraoperative lesion (note the virtual absence of the acetabular roof and of the anterior and posterior walls); ( K ) assembly of the trabeculated metal structure; ( L ) placement of divergent screws and chopped, impacted bone graft; ( M ) placement of the trabeculated metal cup after deposition of a thin layer of cement between the metal components to avoid metallic contact; ( N ) acetabulum cementation at the proper position; ( O ) immediate postoperative radiograph; and ( P ) radiograph three years after the procedure (note the graft integration).

Discussion

The present research evaluated different cases of revision of total hip arthroplasty involving 3D printing in the surgical planning and training of orthopedics and traumatology residents. Several authors have endorsed the importance of such technology in preoperative planning. Mothes et al. 4 report the role of prototyping for preoperative planning to treat bone deformities in the shoulder and believe that it minimizes the risk of intraoperative complications while attempting to improve outcomes.

The treatment of a CT scan image takes approximately one shift, since it requires correction and removal of potential artifacts, implants, and volume failures. Printing takes about 16 hours depending on the filling (the density of the material). The average cost of printing each biomodel is 56 reais (around 10 US dollars). It is worth mentioning that the hips are sectioned in the software to print only from the pubic symphysis to the near sacroiliac area.

The use of prototyped models can simplify the 3D visualization of different conditions, facilitate the understanding and planning of complex surgical procedures, and expand anatomical, radiological, and surgical knowledge.

Final Considerations

In the present work, we observed the need to modify the surgical technique by training in a prototype, using a new trabeculated metal arrangement. The inclusion of these technologies in the preceptor's repertoire is critical for the differentiation of future specialists in the job market, since medical education must adapt to train professionals able to meet societal demands. Therefore, fast prototyping combines the convenience of preoperative training with the use of technology in orthopedic surgeries, and it must become widespread in the medical teaching environment. We emphasize that the present study is not only applicable to orthopedics and traumatology, but to all medical areas.

Agradecimentos

Os autores agradecem a Gabriel Severo da Silva por suas contribuições ao presente trabalho, assim como ao Prof. Dr. André Peres, Samuel Werner Wolf, Luis Fernando Marcelino Braga, Andreia Gomes Aires do LIPECIN/UFCSPA, Prof. Charles Leonardo Israel e ao técnico Derli da Rosa da UPF.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Gabriel Severo da Silva for his contributions to the present study, as well as Dr. André Peres, Samuel Werner Wolf, Luis Fernando Marcelino Braga, Andreia Gomes Aires of LIPECIN/ UFCSPA, Dr. Charles Leonardo Israel and the technician Derli da Rosa of UPF.

Funding Statement

Suporte Financeiro Não houve suporte financeiro de fontes públicas, comerciais, ou sem fins lucrativos.

Conflito de Interesses Os autores declaram não haver conflito de interesses.

Trabalho desenvolvido no Serviço de Ortopedia e Traumatologia da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Porto Alegre e na Universidade Federal de Ciências da Saúde de Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, com a colaboração do Laboratório de Bioengenharia, Biomecânica e Biomateriais da Universidade de Passo Fundo, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil.

Study developed at the Orthopedics and Traumatology Service of Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Porto Alegre and at Universidade Federal de Ciências da Saúde de Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, with the collaboration of the Bioengineering, Biomechanics and Biomaterials Laboratory of Universidade de Passo Fundo, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

Referências

- 1.Oliveira M F, Maia I A, Noritomi P Y, Nargi C G. Construção de Scaffolds para engenharia tecidual utilizando prototipagem rápida. Materia (Rio J) 2007;12(02):373–382. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagaria V, Deshpande S, Rasalkar D D, Kuthe A, Paunipagar B K. Use of rapid prototyping and three-dimensional reconstruction modeling in the management of complex fractures. Eur J Radiol. 2011;80(03):814–820. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang S, Leong K F, Du Z, Chua C K. The design of scaffolds for use in tissue engineering. Part II. Rapid prototyping techniques. Tissue Eng. 2002;8(01):1–11. doi: 10.1089/107632702753503009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mothes F C, Britto A, Matsumoto F, Tonding M, Ruaro R. O uso da prototipagem tridimensional para o planejamento do tratamento das deformidades ósseas do úmero proximal. Rev Bras Ortop. 2018;53(05):595–601. doi: 10.1016/j.rboe.2018.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marques T MR. Porto, Portugal: Faculdade de Engenharia da Universidade do Porto, Portugal; 2013. Definição de um modelo de planeamento pré operatório em ortopedia usando imagem digital [dissertação] [Google Scholar]