Abstract

The IL-36 family of cytokines were identified in the early 2000’s as a new subfamily of the IL-1 cytokine family, and since then, the role of IL-36 cytokines during various inflammatory processes has been characterized. While most of the research has focused on the role of these cytokines in autoimmune skin diseases such as psoriasis and dermatitis, recent studies have also shown the importance of IL-36 cytokines in the lung inflammatory response during infectious and non-infectious diseases. In this review, we discuss the biology of IL-36 cytokines in terms of how they are produced and activated, as well as their effects on myeloid and lymphoid cells during inflammation. We also discuss the role of these cytokines during lung infectious diseases caused by bacteria and influenza virus, as well as other inflammatory conditions in the lungs such as allergic asthma, lung fibrosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cystic fibrosis and cancer. Finally, we discuss the current therapeutic advances that target the IL-36 pathway and the possibility to extend these tools to treat lung inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: interleukin-36 cytokines, IL-1Rrp2, host/microbe proteases, inflammatory response amplification, lung infectious diseases, lung inflammation

Historical Perspective of IL-36 Cytokines Discovery and Functional Studies

IL-36 cytokines are members of the IL-1 cytokine family and encompass the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-36α, IL-36β and IL-36γ, as well as the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-36Ra (1). Each of the IL-36 cytokines is encoded by individual genes, which in humans are located on chromosome 2 in between the il1b and il1br loci (2–4), and share sequence and structural homology. All members of the IL-36 subfamily were identified and partly characterized in the early 2000’s by different research groups, and consequently, they were initially referred to by different names (5–8) ( Table 1 ). To avoid confusion, a new nomenclature system was adopted in 2001 (10). In this system, the IL-36 cytokines were designated as IL-1F5, IL-1F6, IL-1F8 and IL-1F9 based on their relationship to the IL-1 cytokine family and the order of their date of publication (10) ( Table 1 ). In 2010, the current nomenclature was adopted, from which IL-1F5 was designated as IL-36Ra, IL-1F6 was designated as IL-36α, IL-1F8 was designated as IL-36β, and IL-1F9 was designated as IL-36γ (9) ( Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Current and former nomenclature of IL-36 cytokines.

| Current nomenclature (9) | First unified nomenclature (10) | IL-1 extended nomenclature (8) | Family of IL-1 (FIL1) based nomenclature (7) | IL-1-related protein (IL1RP) based nomenclature (6) | IL-1 homologues (IL-1H) based nomenclature (5) | Role in inflammation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-36α | IL1-F6 | FIL1ϵ | Pro-inflammatory | |||

| IL-36β | IL1-F8 | FIL1η | IL-1H2 | Pro-inflammatory | ||

| IL-36γ | IL1-F9 | IL-1ϵ | IL-1RP2 | IL-1H1 | Pro-inflammatory | |

| IL-36Ra | IL1-F5 | IL-1δ | FIL-1δ | IL-1RP3 | IL-1H3 | Anti-inflammatory |

After the discovery of this subfamily of cytokines, functional studies, aimed to understand the biology of IL-36 cytokines, as well as their role in inflammation were performed using in vitro platforms. The first functional analysis was restricted to IL-36γ (initially referred to as IL-1ϵ) and IL-36Ra (referred to as IL-1δ) (8). This first study determined that IL-36γ enhances the activation of Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) signaling through the orphan receptor IL-1 Receptor-Related protein 2 (IL-1Rrp2) – a receptor that is highly expressed in epithelial cells and in embryonic tissue. However, IL-36Ra inhibits NF-κB activation induced by IL-36γ (8). Subsequently, it was shown that the activation of the NF-κB pathway mediated by IL-36γ requires the accessory protein Interleukin-1 receptor accessory protein (IL-1RAcP) (11), which is vital for IL-1 signaling (12). The requirement of IL-36R and IL-1RAcP for NF-κB activation was later described also for IL-36α and IL-36β (11). These initial studies also provided the first mechanistic insights regarding the antagonist effect of IL-36Ra, which competes with IL-36α, IL-36β, and IL-36γ for the IL-1Rrp2 binding pocket without inducing the recruitment of IL-1RAcP and therefore preventing NF-κB signaling (8). Mechanistically, this inhibitory process is similar to the inhibition of IL-1 signaling mediated by IL-1Ra (13) that is discussed in detail in the following sections.

Despite the ability of IL-36 cytokines to activate NF-κB signaling through IL-1Rrp2/IL-1RAcP, controversy existed regarding their biological functions during physiological processes. This was due, in part, to the fact that the concentration of IL-36γ required to observe a biological effect in vitro varied considerably among reports (50 ng/ml in Debets et al., 2001 vs 500 ng/ml in Towne et al., 2004), and because the antagonistic effects of IL-36Ra could not be uniformly reproduced (8, 11). It is now established that, unlike other IL-1 family members that possess caspase cleavage sites, the IL-36 cytokines do not (1) and require post-translational processing at the N-terminal region in order to be fully active (14). N-terminal processing of IL-36α, IL-36β, IL-36γ and IL-36Ra proximal to K6, R5, S18 and V2, respectively, leads to the enhancement of their biological activity (1,000-10,000 fold) (14). The N-terminal processing of IL-36 cytokines provided a logical explanation for some of the earlier controversies regarding IL-36 cytokine function and highlights the complexity of their biology.

As IL-1Rrp2 is highly expressed in the skin, considerable research has focused on understanding the role of IL-36 cytokines in the context of skin diseases, such as psoriasis and dermatitis (11, 15). However, IL-1Rrp2 and IL-36 cytokines are present in other tissues, including the lungs (16), which is an organ continuously exposed to a wide variety of pathogens, antigens and noxious agents that can lead to unwarranted inflammation if not properly regulated. In this review, we describe the factors that trigger the production and activation of IL-36 cytokines, as well as the inflammatory effects of IL-36 cytokines in immune cells. We then discuss the central role of IL-36 cytokines in regulating the host immune response during lung infection and other inflammatory diseases, and finally conclude with current therapeutic tools in clinical trials designed to target the IL-36 pathway and their potential use during lung inflammation.

Production of IL-36 Cytokines Is Mediated by Toll-Like Receptor and Pro-Inflammatory Cytokine Signaling

Several studies have provided insights regarding the cellular sources ( Figure 1 ) and signals ( Figure 2 ) that induce the production of IL-36 cytokines, particularly IL-36α and IL-36γ. Like other pro-inflammatory cytokines, the production and activity of IL-36 cytokines during inflammatory processes are tightly regulated. Signaling through a variety of toll-like receptors (TLRs) has been shown to induce IL-36 production ( Figure 2A ). For example, an in vivo model of acute skin injury demonstrated that TLR-3 signaling is required for IL-36γ expression by keratinocytes. The induction of IL-36γ by TLR-3 is mediated by TRIF and involves the activation of the transcription factor SLUG and the subsequent inhibition of the vitamin D receptor (VRD) (17).

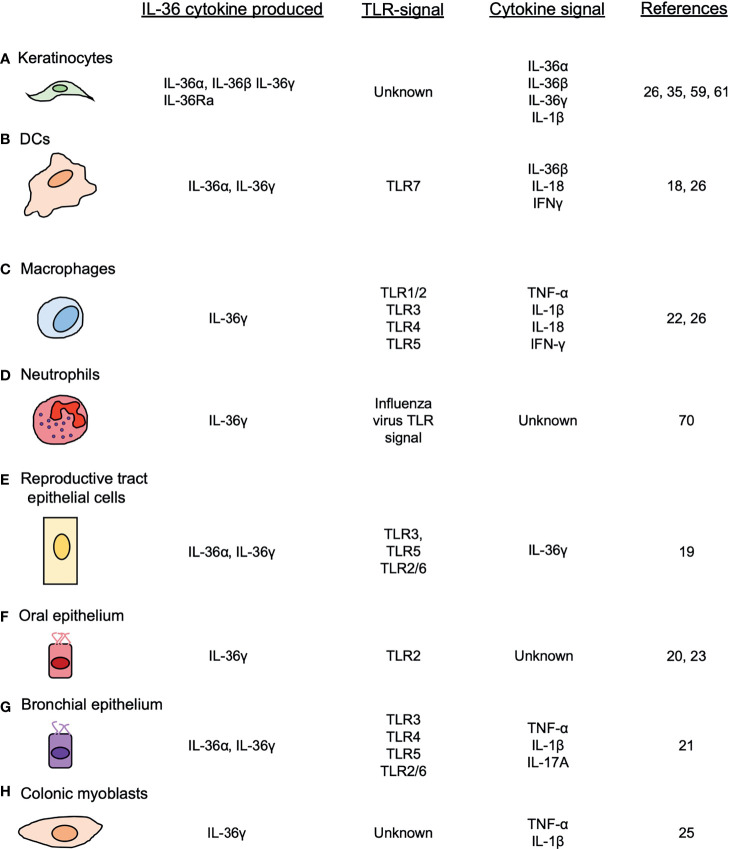

Figure 1.

Cellular sources of IL-36 cytokines. IL-36 cytokines are produced by different cell types, such as (A) keratinocytes, (B) DCs, (C) macrophages (D) neutrophils, (E) female reproductive epithelial cells, (F) oral epithelial cells (G) bronchial epithelial cells and (H) colonic myoblasts, after the induction of TLRs and other pro-inflammatory cytokines.

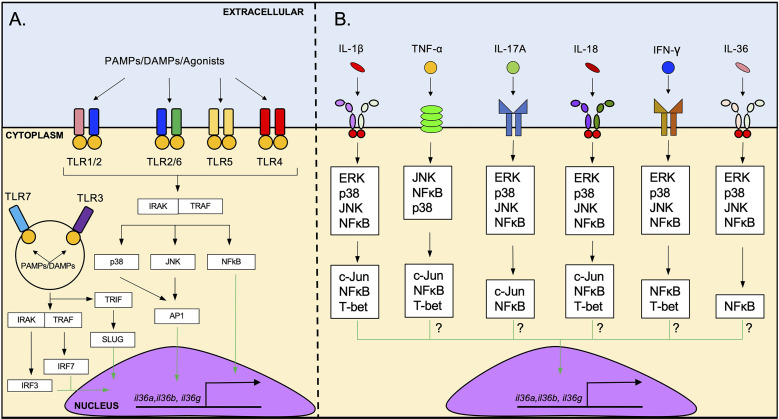

Figure 2.

Induction of IL-36 cytokine expression by TLR agonists and pro-inflammatory cytokines. (A) il36 transcription is triggered by the activation of several cell surface TLRs such as TLR1/2, TLR2/6, TLR5 and TLR4. The possible intracellular pathway that induces il36 transcription downstream of TLRs activation involves signaling via IRAK/TRAF and p38/JNK/NFκB, followed by the translocation of AP1 and NFκB to the nucleus. Intracellular TLRs such as TLR3 and TLR7 can also induce il36 transcription. These receptors can activate IRF3/7 which may induce the transcription of il36. (B) il36 expression is induced by several pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-17A, IL-18, IFN-γ and IL-36 cytokines. IL-1β-mediated induction of il36 expression via IL1R-IL1AcP involves the ERK/p38/JNK/NFκB signaling and subsequent activation of the transcription factors c-Jun, T-bet and NFκB. The exact pathway via which other cytokines induce il36 transcription has not been determined yet but likely involves similar intracellular signaling molecules.

The TLR7 agonist Imiquimod is a potent inducer of IL-36α and IL-36γ in bone-marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) in vitro and in a model of dermatitis in vivo (18). In this study, Imiquimod induced the in vitro production of IL-36α and IL-36γ by BMDCs and the specific depletion of CD11c cells ameliorated the cutaneous pathology in vivo (18). Another study showed that cultured human female reproductive tract epithelial cells produced IL-36γ after treatment with different TLR ligands, including Poly(I:C) (TLR3), Flagellin (TLR5) and FSL-1 (TLR2/6) (19). Others have reported that nasal epithelial cells produce IL-36γ via TLR2/IRAK/IRF6 in response to the Gram-negative bacterium Porphyromonas gingivalis (20). Relevant to the lungs, in vitro studies using primary cells and cell lines have shown that both pulmonary macrophages and bronchial epithelial cells produce IL-36α and IL-36γ, but not IL-36β or IL-36Ra in response to different TLR agonists (21, 22). Interestingly, whereas PAM3CSK4 (TLR1/2), Poly(I:C) (TLR3), LPS (TLR4) and Flagellin (TLR5) were shown to induce il36g expression in pulmonary macrophages (22), dsRNA (TLR3), LPS (TLR4), Flagellin (TLR5) and FSL-1 (TLR2/6) induced the expression of il36a and il36g in cultured human bronchial epithelial cells. These data show that TLR ligands induce the expression of il36 genes in different cell types, although it also suggests that the induction of specific il36 genes varies depending on the ligand as well as the cellular context (21).

During Candida albicans infection, IL-36 cytokines production by human oral epithelial cells (TR146 cells) is dependent upon p38, NF-κB and PI3K signaling, as their inhibition, significantly diminished the expression of Il36a and Il36g (23). Although this study did not provide insights regarding which TLR triggers the production of IL-36 by these cells, TLR2 and TLR4 signaling may induce the production of IL-36 cytokines in this model (24).

Besides TLR signaling, several pro-inflammatory cytokines can induce IL-36 cytokine production through the activation of their cognate receptors ( Figure 2B ). For example, IL-1β and TNF-α have been identified as potent inducers of IL-36γ in human colonic myoblasts (25) and in mouse pulmonary macrophages (22). IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-17A are potent inducers of IL-36α and IL-36γ in human bronchial epithelial cells, acting synergistically with each other to induce a robust response (21). IL-18 and IFN-γ induce the production of IL-36γ in the cell line KG-1 – that resembles human dendritic cells (DCs) – and primary human DCs and macrophages (26). In addition to these cytokines, several reports have also described the ability of IL-36 cytokines to enhance their own expression. For example, BMDCs stimulated with IL-36β increased expression of il36a and il36g (18). Similarly, treatment of HaCat cells (human immortalized keratinocytes) with IL-36γ has been shown to increase il36g expression (26), and IL-36γ treatment of vaginal and endocervical epithelial cells leads to increased IL-36γ production in vitro (19). Mechanistically, the induction of IL-36γ by IL-1β appears to involve ERK1/2, JNK1/2, p38, c-Jun and NF-κB signaling, as inhibition of these signaling pathways reduced il36g expression in human colonic myoblasts (25) ( Figure 2B ). TNF-α (27), IL-17A (28), IL-18 (29, 30), IFN-γ (31) and IL-36 cytokines (29, 30) are known to activate MAPK signaling and NF-κB signaling ( Figure 2B ), suggesting that these cytokines may trigger IL-36 production in a similar fashion as IL-1β.

The transcription factor T-bet has been shown to be positively involved in il36g expression in myeloid cells, by binding to a T-box motif present in the position -500 of the il36g promoter (26). T-bet knockdown significantly reduced the expression of il36g in response to IFN-γ, IL-1β and TNF-α in these cells (26). T-bet is expressed in lymphoid and myeloid cells (32). In T cells, T-bet expression is required for the development of a Th1 response (33). Mechanistically, T-bet induces a Th1 response through the recruitment of the super elongation complex (SEC), positive transcription elongation factor (P-TEFb) and the multiprotein complex called “Mediator”, all of which are required for transcription of Th1 genes (34). NF-κB has also been reported to recruit this same complex, albeit through a different molecular mechanism than T-bet (34). Whether NF-κB and T-bet cooperate with each other to induce the transcription of il36g and potentially other IL-36 cytokines in myeloid cells is unknown and requires further study. Another transcription factor involved in il36g expression is Nuclear factor erythroid 2 (Nrf2). Specifically, Nrf2 overexpression increased il36g gene expression and IL-36γ protein production in the epidermis in a murine model. The pharmacological activation of Nrf2 on murine immortalized keratinocytes (MIKs) and HaCaT cells treated with tert-butylhydroquinone (tBHQ) also increased the expression of il36g (35). Mechanistically, this study found that Nrf2 binds to three Antioxidant Response Elements (ARE) enhancers located upstream to the putative transcriptional start site of il36g, thereby inducing il36g expression (35).

The identification of the intracellular adaptors involved in the induction of IL-36 cytokines by IL-1β (25) provides a logical framework for understanding the downstream signaling pathways involved in the induction of IL-36 cytokines by other pro-inflammatory cytokines. For example, the downstream signaling pathways activated by IL-18 and IL-36 cytokines, both members of the IL-1 family, are similar to the ones activated by IL-1β (29, 30) ( Figure 2B ). TNF-α, IL-17A and IFN-γ signaling also share important downstream signaling pathways with IL-1β signaling that mediate the induction of IL-36 cytokines, including JNK, ERK, p38 and NF-κB (27, 28, 31) ( Figure 2B ). These observations suggest overlap of the different signaling pathways and some redundancy in the system that mediate the production of IL-36 cytokines in response to different cytokine signals ( Figure 2B ).

Neutrophil, Macrophage/Epithelial and Microbe-Derived Proteases Process IL-36 Cytokines

In order to be fully active, IL-36 cytokines undergoes N-terminal processing by proteases (14). It was unclear for some time which proteases were responsible for processing and activating IL-36 cytokines. However, in 2016, a study showed that the supernatant of PMA-activated neutrophils cleaved IL-36α, IL-36β and IL-36γ, and induced the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in IL-1Rrp2-transfected HeLa cells (36). These observations suggested that neutrophil-derived proteases can cleave and activate IL-36 cytokines. The incubation of different recombinant neutrophil-derived proteases with each IL-36 cytokine and the subsequent incubation of the cleaved products with IL-1Rrp2-transfected HeLa cells led to the identification of different neutrophil-derived proteases that can post-translationally process IL-36 cytokines. Whereas IL-36α is cleaved proximal to A4 and L5 by Cathepsin G (CatG) and neutrophil elastase (NE), respectively (36, 37) ( Figure 3A ), IL-36β is cleaved proximal to E6 by CatG ( Figure 3B ), and IL-36γ can be cleaved proximal to Y16 by either NE and proteinase-3 (P3) (36, 37) ( Figure 3C ). In these cases, cleavage leads to increased biological activity of the IL-36 cytokine in IL-1Rrp2 transfected HeLa cells and in primary keratinocytes, although possible differences in the activity of each of these cleaved products have not been evaluated (36). Like the pro-inflammatory IL-36 cytokines, the activity of the anti-inflammatory IL-36Ra is also regulated by proteolytic processing (38). IL-36Ra can be activated following cleavage proximal to V2 by NE or through cleavage proximal to S4 by CatG and P3 (38) ( Figure 3D ). Importantly, the activation of IL-36 cytokines does not appear to be limited to neutrophil proteases. Cathepsin S (CatS) cleaves IL-36γ proximal to S18 and the cleavage product has been described as the most bioactive form of IL-36γ (39) ( Figure 3C ). In this study, CatS, expressed by keratinocytes and fibroblasts, was highly upregulated in response to treatment with various pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-17 and IL-22 (39). This study showed that the Y16 isoform produced by NE failed to induce the production of IL-8 in HaCaT cells in vitro when compared to the S18 isoform (39). However, this study also demonstrated that the incubation of full-length IL-36γ in the presence of increasing molar concentrations of neutrophil proteases, increased IL-8 secretion by HaCaT cells albeit to a lesser effect when compared to CatS (39). While the IL-36γ cleaved just proximal to Y16 does not display the same bioactivity as IL-36γ cleaved proximal to S18 in vitro, neutrophil elastase appears to induce the production of IL-8 in HaCaT cells when co-incubated with full length IL-36γ. This conclusion is supported by at least three studies that show that neutrophil serine proteases cleave and increase the bioactivity of IL-36 cytokines (36, 37, 40). In these studies, full-length IL-36α, IL-36β and IL-36γ induced IL-6, IL-8 and CXCL1 production by transfected IL-36R+ Hela cells when supernatant from PMA-activated neutrophils was added, and this effect was diminished when cathepsin G and elastase inhibitors were included (36, 37, 40). Further in vitro studies using purified cathepsin-G, neutrophil elastase and proteinase-3 determined that neutrophil proteases induce the bioactivity of the different IL-36 cytokines as well as identification of the cleaved isoforms. Importantly, none of the studies that have determined the N-terminal processing by neutrophil proteases (36, 37, 39–41) have identified the S18 isoform of IL-36γ as a cleaved product. Further in vivo studies that capture the complexity of the biology surrounding the production and activation of IL-36 cytokines are required to accurately conclude whether IL-36 isoforms generated by neutrophil proteases amplify inflammation in in vivo models.

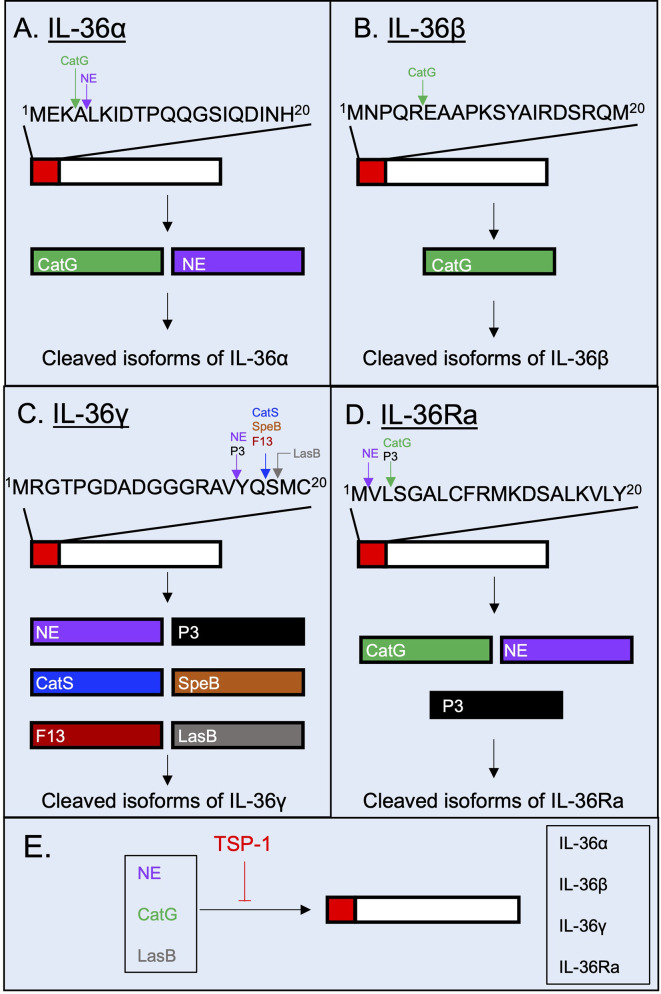

Figure 3.

Post-translational processing of human IL-36 cytokines by extracellular proteases. Human IL-36 cytokines are selectively cleaved and potentially activated by proteases. (A) IL-36α is cleaved extracellularly by neutrophil proteases Cathepsin G (CatG) and Neutrophil Elastase (NE). (B) IL-36β has been described to be N-terminally processed by CatG. (C) IL-36γ is selectively cleaved by Proteinase-3 (P3), NE, Cathepsin S (CatS), the Streptococcus pyogenes-derived protease SpeB, the Aspergillus fumigatus-derived protease F13 and the Pseudomonas aeruginosa-derived protease LasB. (D) IL-36Ra is cleaved and potentially activated by NE, CatG and P3. (E) The proteolytic cleavage of IL-36 cytokines can be regulated by the host glycoprotein thrombospondin-1, which has been shown to possess inhibitory properties against the host proteases NE and CatG, and against the bacterial protease LasB.

CatS is not only expressed by keratinocytes, but also by lung epithelial cells (42), intestinal epithelial cells (43) and human monocytic THP-1 cell line (44). Importantly, a recent study has demonstrated that pathogen-derived proteases secreted by Streptococcus pyogenes (SpeB), Aspergillus fumigatus (Aspergillus factor 13 – F13), as well as unknown proteases produced by Staphylococcus aureus and Trichophyton rubrum can process IL-36γ proximal to S18 ( Figure 3C ) (45). Moreover, in a recent study, we demonstrated that the Pseudomonas aeruginosa elastase B (LasB), cleaves IL-36γ proximal to M19, just one residue after S18 which is the site of cleavage mediated by CatS, SpeB and F13 (41) ( Figure 3C ). In silico docking analysis predicted similar binding of the M19 isoform to the IL-1Rrp2/IL-1RacP heterodimer compared to the S18 isoform, although the biological activity of M19 isoform remains to be experimentally confirmed (41). Our work also showed that extracellular processing of IL-36 cytokines is counter-balanced by protease inhibitors released by a variety of cells during inflammatory processes such as the host matricellular glycoprotein thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) which regulates the proteolytic activity of NE, CatG and LasB, and thereby dampening IL-36γ-mediated inflammation (41, 46, 47) ( Figure 3E ).

IL-36 Cytokines Are Recognized by IL-1Rrp2/IL-1RAcP and Trigger Several Inflammatory Processes That Amplify Host Inflammation

IL-1Rrp2 Expression, Receptor-Ligand Interactions and Intracellular Signaling

Once IL-36 cytokines are cleaved and fully activated, they bind to IL-1Rrp2 and transduce a complex signaling cascade that turns on an inflammatory response (48). In humans, IL-1Rrp2 is widely expressed in keratinocytes in the skin and the esophagus but poorly expressed in other organs like reproductive organs, lymph nodes or lungs (16). Various immune cells also express IL-1Rrp2 (49–52). One report showed that circulating DCs and monocytes, but not CD3+ T cells express IL-1Rrp2 on their surface and respond to IL-36 cytokines in vitro (49). A subsequent study showed that CD19+ B cells and CD8+ T cells express IL-1Rrp2 on their surface but CD4+ T cells expressed high amounts of IL-1Rrp2 in the cytoplasm (50). Human neutrophils do not express IL-1Rrp2 at baseline (51), but during chronic rhinosinusitis where IL-36 cytokines are locally upregulated, neutrophils were found to be the main cell type expressing IL-1Rrp2 in nasal polyps, but not in the bloodstream (51). This finding suggests that the microenvironment can induce the expression of IL-1Rrp2 in neutrophils that normally do not express this receptor. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that peripheral blood neutrophils, which do not express IL-1Rrp2 under basal conditions, expressed IL-1Rrp2 after incubation with the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-1β (51). In mice, the expression of IL-1Rrp2 in immune cells follows a similar pattern as in humans with some notable differences. BMDCs, generated from bone marrow precursors in presence of GM-CSF, and CD4+ T cells express IL-1Rrp2 and can respond to IL-36 agonists in the absence of any other stimuli (52). Neutrophils and macrophages derived from the bone marrow (BMDMs), on the other hand, do not significantly express IL-1Rrp2 at baseline (52).

The molecular mechanism by which IL-36 cytokines bind to IL-1Rrp2 is similar to the mechanism described for IL-1/IL-1R (53). The IL-36 receptor heterodimer is comprised of IL1-Rrp2 and the accessory protein IL-1RAcP (54). When agonistic IL-36 cytokines bind to IL-1Rrp2 on the cell surface, IL-1RAcP is recruited to the IL-36 receptor-ligand complex (54). Once the complex is complete, TIR domains present within the intracellular region of IL-1Rrp2 and IL-1RAcP recruit MyD88 and IL-1R associated kinase (IRAK), which in turn trigger NF-κB and MAPK activation to promote the expression of pro-inflammatory genes ( Figure 4A ).

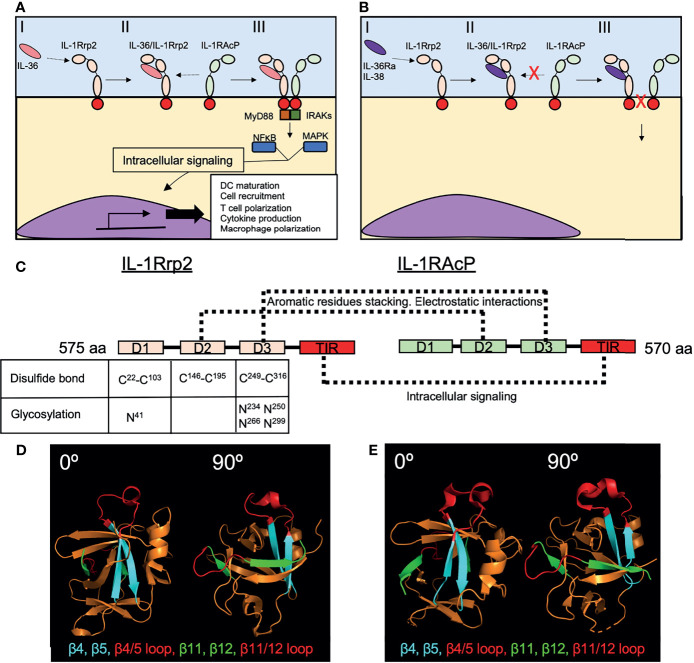

Figure 4.

Recognition of IL-36 cytokines by the IL-1Rrp2/IL-1RAcP complex. (A) The initial recognition of IL-36 agonists by IL-1Rrp2 on the surface of the cell (I), triggers the recruitment of IL-1RAcP to the receptor-ligand complex (II), initiating an intracellular pathway characterized by the activation of MyD88 and IRAKs and then NFκB and MAPK that will induce the transcription of several genes involved in DC maturation, T cell and macrophage polarization and cytokine production (III). (B) IL-36Ra and IL-38 also bind IL-1Rrp2 (I) but this binding does not recruit IL-1RAcP (II), thus inhibiting the inflammatory response triggered by IL-36 agonists (III). (C) IL-1Rrp2 and IL-1RAcP are composed of three extracellular domains (D1-D3) and one TIR intracellular domain. Disulfide bonds and N glycosylation found in D1, D2 and D3 of IL-1Rrp2 are critical for IL-1Rrp2/IL-36 binding. Direct interactions between IL-1Rrp2 and IL-1RAcP through their respective D2s and D3s have been identified in absence of IL-36 agonists. (D) Loops between β4/β5 and β11/β12 present in human IL-36γ (PDB 4IZE) mediate interaction with IL-1RAcP. (E) Mouse IL-36Ra (PBD 4P0L) has similar loops in these regions with a slightly different structural conformation that avoid the interaction with IL-1RAcP. Crystal structures were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org) and modeled in PyMOL (2.3.3).

The anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-36Ra (K D =5.8nM) binds with a higher affinity to IL-1Rrp2 compared to N-terminally processed K6-IL-36α (K D =480nM) and S18-IL-36γ (K D =1800nM) (54). A previous study analyzed the affinity of the IL-36 cytokines that bind to the IL-1Rrp2/IL-1RAcP heterodimer. This study found that K6-IL-36α (K D =0.021nM), R5-IL-36β (K D =0.007nM) and S18-IL-36γ (KD=0.147nM) bound to the IL-1Rrp2/IL-1RAcP heterodimer with higher affinity than V2-IL-36Ra (KD=10.2nM) (14). From a biological standpoint, IL-36 agonists initially bind to IL-1Rrp2, promoting the recruitment of IL-1RAcP that leads to subsequent signaling. Whereas the first study showed that the dominant pathway of IL-36 activation is through agonist-ILRrp2 complex formation and subsequent recruitment of IL-1RAcP, IL-1RAcP does not bind IL-1Rrp2 when no agonist is present (54). In contrast to agonist IL-36 cytokines, the binding of IL-36Ra to IL-1Rrp2 does not result in the recruitment IL-1RAcP, thus preventing the induction of downstream signaling (54) ( Figure 4B ). While the Towne et al., 2011 findings show that the affinity of processed IL-36 agonists are in orders of magnitude higher than IL-36Ra, the findings focused on binding affinity to the heterodimer which is restricted to the agonists and not IL-36Ra. In other words, IL-36Ra does not bind the heterodimer but just binds to IL-1Rrp2.

IL-38, another cytokine from the IL-1 family, also binds to IL-36R and suppresses the pro-inflammatory activity of IL-36 cytokines through a similar mechanism as IL-36Ra (55) ( Figure 4B ). Although the crystal structure of IL-36R has not been resolved, biochemical and in silico approaches have provided important insights regarding IL-1Rrp2-ligand interactions (54, 56, 57). IL-1Rrp2 consist of three extracellular structural domains (D1-D3) and one intracellular TIR domain that triggers downstream signaling ( Figure 4C ). The three extracellular domains are part of the ligand-binding pocket, where D1 conforms to the upper part of the pocket, D2 the backside and D3 the bottom part (56). D2 of IL-1Rrp2 is also important for the interaction with IL-1RAcP (56). Disulfide bonds between Cysteine residues C22/C103, C146/C195 and C249/C316 in D1, D2 and D3 respectively as well as Asparagine (N) linked glycosylation of IL-1Rrp2 at positions N41 (D1), N234, N250, N266, N299 (D3) of the extracellular domains are required for the intracellular signaling and trafficking to the cell surface of IL-1Rrp2 ( Figure 4C ). Molecular modeling predicted the relevance of these IL-1Rrp2 sites and confirmed biochemically after mutating each cysteine or asparagine to alanine. Each of these substitutions impaired IL-1Rrp2/IL-1RAcP signaling in response to agonist (56).

Different residues within the structural domains were found to be crucial for IL-36α, IL-36β and IL-36γ to bind and induce signaling via IL-1Rrp2/IL-1RAcP, suggesting that each IL-36 cytokine is recognized differently by IL-1Rrp2 (56). This hypothesis has been corroborated by testing the role of specific amino acids (N41, C42 and C118) of IL-1Rrp2 in response to each IL-36 cytokine (56). Whereas substitution of N41 by A impaired IL-1Rrp2-mediated signaling in response to the three pro-inflammatory IL-36 cytokines, C42 substitution highly impaired the response to IL-36α but did not affect the IL-36β response and only mildly affected the response to IL-36γ. Similarly, substitution of C118 highly affected IL-36α-responsiveness, but not IL-36γ responsiveness and only mildly affected IL-36β-responsiveness (56). Regarding why the binding of pro-inflammatory IL-36 cytokines to IL-1Rrp2 induces the recruitment of IL-1ARcP whereas the ligation of IL-36Ra to IL-1Rrp2 does not, one report identified the existence of two structural loops present in human IL-36γ – one between β-strands 11 and 12 and one between β-strands 4-5 – that appear to be involved in the recruitment of IL-1RAcP to the IL-1Rrp2/IL-36γ complex and the consequent induction of downstream signaling ( Figure 4D ) (57). Similar loops are also present within IL-36Ra, but these loops slightly differ in structure from those observed in IL-36γ ( Figure 4E ). Interestingly, the exchange of these loops between IL-36γ and IL-36Ra inverted the ability of these cytokines to bind IL-1RAcP (57), indicating that these structural regions are crucial for the recruitment of IL-1RAcP to the receptor-ligand complex. IL-36γ directly interacts with both IL-1Rrp2 and IL-1RAcP (56), and thus, IL-36γ may facilitate the recruitment of IL-1RAcP to the IL-36 receptor-ligand complex. However, molecular modeling and biochemical approaches also established a direct interaction between IL-1Rrp2 and IL-1RAcP in the absence of a ligand (56). This interaction involves aromatic residues stacking and electrostatic interactions between D2-D2 and D3-D3 interactions of both receptors (56) ( Figure 4C ).

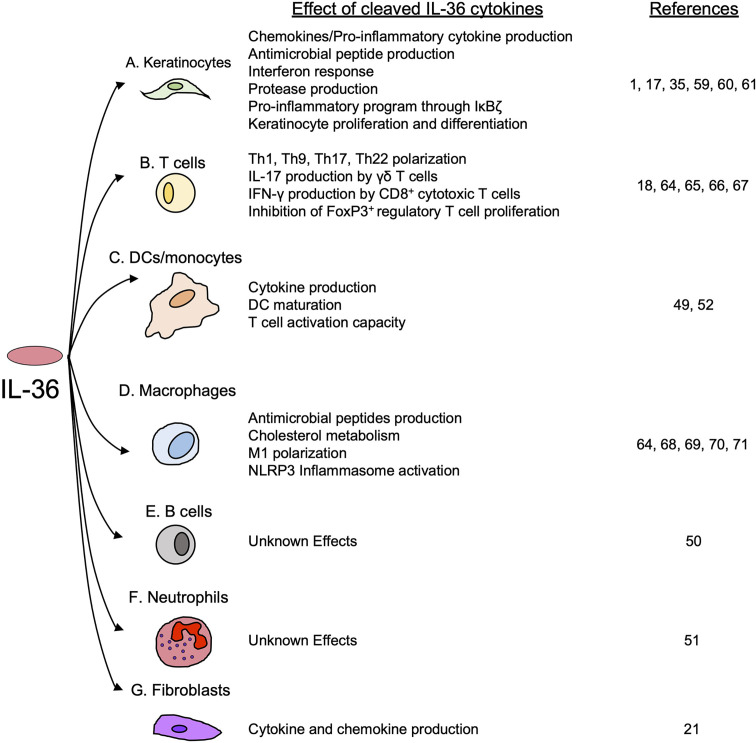

Pro-Inflammatory Effects of IL-36 Signal in Lymphoid and Myeloid Cells

Even though IL-36 cytokines are not directly chemotactic to inflammatory/immune cells, they strongly triggers pro-inflammatory cytokine/chemokine production via MAPK- and NF-κB-signaling in a variety of cells and tissues (58). As IL-1Rrp2 is highly expressed in keratinocytes, many studies investigating the biological effects of IL-36 cytokines have initially focused on their role during skin inflammatory disorders such as psoriasis and dermatitis. In keratinocytes, IL-36 cytokines enhance the production of a variety of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including CXCL-8, IL-23A, IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α, as well as antimicrobial peptides such as β-defensins 2 and 3, the human cathelicidin LL37 and the antimicrobial psoriasin S10047 (1, 59, 60) ( Figure 5A ). It has been shown that, in keratinocytes, IL-36 cytokines enhance their own production in an autocrine manner (35, 61). Interestingly, in keratinocytes, IL-36 cytokines also induce the production of IL-36Ra (59), which may be a crucial negative feedback mechanism to regulate the inflammatory effects of IL-36 cytokines.

Figure 5.

The effects of cleaved IL-36 cytokines on keratinocytes and immune cells. IL-36 cytokines trigger the activation of several inflammatory processes in (A) keratinocytes and various immune cells, including (B) T cells, (C) DCs and monocytes and (D) macrophages. (E) B cells and (F) neutrophils are known to express IL-1Rrp2, but the effects of IL-36 cytokines on their function have not yet been determined. Finally, IL-36 cytokines have shown to induce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in (G) fibroblasts.

Of particular interest is the observation that IL-36α and IL-36γ induce the expression of NF-κB inhibitor zeta (IκBζ) in keratinocytes (60). IκBζ is a transcription factor that regulates some NF-κB target genes in response to IL-36α and IL-36γ (60). In primary keratinocytes and HaCaT cells, IκBζ is essential for IL-36-induced inflammation, and in the context of IL-36 stimulation, its silencing downregulates several genes involved in a variety of processes, including neutrophil chemotaxis, IL-6 response factors, STAT phosphorylation, leukocyte adhesion and differentiation, T cell-activation, innate immunity and leukocyte activation (60) ( Figure 5A ). Moreover, it has been described that during injury, IL-36γ induces keratinocyte differentiation and proliferation through the induction of Reg3A (17) ( Figure 5A ).

Although IL-1Rrp2 expression is generally highest in the skin compared to other organs and tissues (16), IL-36 cytokines also exert important inflammatory effects in other tissues. In the intestine, it has been described that IL-36 cytokines induce and amplify the expression of the IL-23/IL-22 axis (62), as IL-36R-/- mice with DSS-induced colitis present with reduced expression of IL-23 and IL-22 in the intestine compared to WT mice (62). Ex vivo analysis of colonic explants from DSS treated mice showed that IL-36γ induced the expression of IL-23 in DCs through a Notch2-dependent mechanism. The induction of IL-23 by IL-36γ was found to be mediated by NF-κB and promoted the recovery of colonic damage induced by DSS via the induction of IL-22 responses (62). This IL-36/IL-23/IL-22 axis has been recently proven to be important in host defense against the enteropathogenic bacteria Citrobacter rodentium (63). In this model of infection, IL-36γ induces the production of IL-22 in CD4+ T cells in the presence of DCs, a response that is mediated by the transcription factor Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) and by the production of IL-6 (63). Here, the activity of IL-36γ is protective against C. rodentium infection, as IL-36R-/- mice not only showed impaired bacterial clearance and higher intestinal damage, but also impaired survival compared to WT mice (63).

Another major effect of IL-36 cytokines is the activation of the IL-23/IL-17A axis in the skin and in the kidney during inflammation and fibrosis (18, 64). In a model of psoriasiform dermatitis, IL-36 cytokines produced by DCs were shown to induce the recruitment of neutrophils and γδ T cells (18). In this model, lack of IL-1Rrp2 reduces the disease severity and at the same time reduces the production of IL-17A by γδ T cells (18). IL-17A-/- and IL-23-/- mice showed the same phenotype, suggesting that IL-36 cytokines contribute to the severity of experimental psoriasiform dermatitis by inducing the expression of IL-23 and IL-17A (18).

Interestingly, IL-36α expression is also increased in chronic kidney disease in patients with renal tubulointerstitial lesions (64). In a mouse model of unilateral ureteral obstruction that mimics the renal tubulointerstitial lesions observed in humans, IL-36α activated the IL-23/IL-17 axis, and by doing so, IL-36α amplified inflammation and the development of renal lesions (64). Besides upregulating Th17 response, IL-36 cytokines have been implicated in the induction of Th1 and Th9 responses. One study has shown that IL-36 cytokines directly induce proliferation and secretion of IL-2 in naïve CD4+ T cells and IL-36 cytokines act synergically with IL-12 to drive the acquisition of a Th1 phenotype characterized by the production of IFN-γ (65). Moreover, IL-36 cytokines can induce a Th9 response in T cells, which is characterized by the production of IL-9 and inhibits the proliferation of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. Whereas the induction of IL-9 expression by IL-36γ was found to be dependent on IL-2/STAT5 and IL-4/STAT6 signaling, the inhibition of regulatory T cells was mediated through the impairment of the Foxp3 locus acetylation. In conjunction, both effects contributed to colonic inflammation in an experimental oxazolone-induced colitis (66). Finally, in vitro analyses have determined that IL-36γ triggered IFN-γ production in CD8+ T cells previously stimulated with anti-CD3 (67) ( Figure 5B ).

IL-36 cytokines exert direct effects in different myeloid cells, inducing several inflammatory processes, such as pro-inflammatory cytokine production (49, 52), DC maturation (49, 52), antimicrobial peptide production, and inflammasome activation in macrophages (64, 68). The induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines by IL-36 cytokines has been described in human monocytes and DCs, in which IL-36α, IL-36β and IL-36γ upregulated IL-6 at the transcript and protein level (49). In mice, IL-36α, IL-36β and IL-36γ induced the production of IL-6, IL-12p40, IL-12p70, CCL11, CCL4, TNF-α and G-CSF in BMDCs (52). IL-36 cytokines also induced DC maturation and increased the expression of the surface marker CD83 and the co-stimulatory molecule CD86, which are required for T cell activation (49, 52) ( Figure 5C ). In macrophages, IL-36γ induced the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome through TLR4/MyD88 pathway (64) and increased the production of the antimicrobial peptides cathelicidin and β-defensin 2 in a dose-dependent manner (68, 69). In addition, IL-36γ was shown to modulate M1 macrophage polarization (70, 71) ( Figure 5D ). As discussed above, IL-1Rrp2 has been found to be expressed on the surface of neutrophils and B cells (50, 51). However, little is known about the effect of IL-36 cytokines on the function of these cells ( Figures 5E, F ). Since neutrophil proteases cleave and activate IL-36 cytokines, it is speculated that neutrophils may do so to enhance their own activation and antimicrobial activity. However, this has not been elucidated to date.

The Active Role of IL-36 Cytokines During Lung Inflammatory Diseases

The respiratory tract is anatomically compartmentalized into the upper and the lower respiratory tract (72). Both portions are susceptible to bacterial, viral, and fungal infections, although lower respiratory tract infections are associated with higher morbidity and mortality. Even though the baseline expression of IL-1Rrp2 at the transcript level is lower in lung tissue compared to that in the skin, instillation of recombinant cleaved IL-36α (73) and IL-36γ (41, 74) into the lungs of healthy mice results in rapid induction of cytokine production and neutrophil recruitment in the alveolar space, highlighting that IL-36 cytokines exert potent pro-inflammatory effects in the lungs. Numerous studies have described a major protective role for IL-36 cytokines in the host defense against pulmonary infections caused by a wide variety of pathogenic bacteria, including Streptococcus pneumoniae (Spn), Klebsiella pneumoniae (Kpn), Legionella pneumophila (Lpn), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) and Mycobacterium bovis BCG (BCG) (22, 65, 68, 69, 71, 75) ( Table 2 ). In contrast with the protective effects of IL-36 cytokines on the host immune response and survival in most pulmonary bacterial infections, IL-36 cytokines have been reported to be detrimental for the host during infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Pa) (77) ( Table 2 ). Although IL-36 signaling has also been implicated in the host immune response during influenza infection, the role of IL-36γ is controversial between studies and the apparent role of IL-36α or IL-36β has not been explored (70, 78) ( Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Role of IL-36 cytokines during lung bacterial and viral infection and their effect in lung immunity and host survival.

| Pathogen | IL-36 cytokine involved | Cellular source(s) | Effect in host survival | Effect in pathogen clearance | Effect in lung inflammation | Effect in cytokine production | Effect in immune cell recruitment/activation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial | ||||||||

| Strepcococcus pneumoniae | IL-36γ | Lung resident macrophage | Promotes survival | Improves bacterial clearance | Unknown | Induces | Activation of macrophages. No effect in cell recruitment. | (22, 75) |

| IL-12p40 IL-23p19 IL-17 TNF-α | ||||||||

| IP-10 | ||||||||

| IFN-γ | ||||||||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | IL-36γ | Lung resident macrophage | Promotes survival | Improves bacterial clearance | Unknown | Induces | Unknown | (22, 75) |

| IL-12 | ||||||||

| IL-23 | ||||||||

| IFN-γ | ||||||||

| Legionella pneumophila | IL-36α | Unknown | Promote survival | Improve bacterial clearance | Reduce lung injury | Unknown | Enhance neutrophil, monocyte and macrophages recruitment. Enhanced macrophage polarization and activation. | (71) |

| IL-36γ | ||||||||

| Mycobacterium bovis BCG | Unknown | Unknown | None | None | Reduce lung injury | Induce | Unknown | (65, 76) |

| IL-6 | ||||||||

| TNF-α | ||||||||

| IFN-γ | ||||||||

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | IL-36γ | Macrophage | None | Improves bacterial clearance by macrophages in vitro | None | None | Enhances production of antimicrobial peptides by macrophages through LXR pathway. | (68, 69, 76) |

| Lung epithelial cells | ||||||||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | IL-36γ | Lung resident macrophage | Reduces survival | Impairment of bacterial clearance | Increase lung injury | Induces TNF-α IL-6 |

Impairs antimicrobial ability on macrophages through COX-2 activation and PGE2 production. | (77) |

| Alveolar epithelial cells | IL-17 IL-10 |

|||||||

| Viral | ||||||||

| Influenza virus | IL-36α IL-36β IL-36γ |

Alveolar epithelial cells | Opposite results | Impairment of viral clearance | 1.IL-36R-/- mice showed reduced lung injury compared to WT mice | Induce IL-17 |

Enhanced neutrophil infiltration Impaired T cell activation | (70, 78) |

| Neutrophils | 1. L-36R-/- mice improved survival. IL-36γ-/- mice show equivalent survival compared to WT mice | 2. IL-36γ-/- mice showed severe lung injury compared to WT mice | Increased macrophage apoptosis | |||||

| 2. IL-36γ-/- mice showed improved survival compared to WT mice. | CXCL-1 | M1 macrophage polarization. | ||||||

| IP-10 Reduced | ||||||||

| IFN-β Opposite results found in IL-6 |

Role of IL-36 Signaling During Lower Respiratory Tract Infections

The Gram-positive pathogen Spn is the most common cause of community acquired pneumonia worldwide (79) and poses a major threat to public health given its ability to cause pneumococcal invasive diseases and the emergence of multi-drug resistant clones and serotypes not covered in the current vaccines (80–82). Spn has several virulence factors on its surface that impair the action of the host complement system and antibodies, and it also possesses a polysaccharide capsule that allows it to prevent phagocytosis by macrophages and neutrophils (83, 84). During Spn infection, IL-36γ – but not IL-36α or IL-36β – is rapidly produced in the lungs by macrophages, which packages IL-36γ into microparticles and exosomes for its secretion to the extracellular space (22, 75).

The production of IL-36γ has been shown to be essential for host defense against acute pulmonary Spn infection in mice, as both genetic IL-36γ deficiency and antibody-mediated depletion of IL-36γ are associated with impaired lung bacterial clearance, increased bacterial dissemination, and reduced survival (75). Interestingly, IL-36γ deficiency did not affect neutrophil recruitment to the lungs, but instead, diminished the local production of key pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IFN-γ (75), which is well-known to activate macrophages and to enhance their ability to kill bacteria (85). Consistently, ex vivo stimulated macrophages derived from IL-36γ-/- and IL-36R-/- mice exhibited an impaired response to Spn that was characterized by a reduced phagocytic ability and reduced expression of Nos2 (75), which encodes iNOS that is part of the killing machinery of macrophages (86). Importantly, treatment of IL-36γ-/- mice with IL-36γ-loaded microparticles restored the production of IFN-γ, IL-12 and IL-23 in the lungs and improved lung Spn clearance (75). These observations indicate that IL-36γ is essential for the induction of key pro-inflammatory cytokines, including the Th1 cytokine IFN-γ, suggesting that IL-36γ is a key regulator of macrophage activation during Spn infection (75).

A similar role for IL-36γ has been described during pulmonary infection with the Gram-negative bacterium Kpn. The polysaccharide capsule of Kpn is crucial for enabling the bacteria to evade phagocytosis and escape clearance by macrophages and neutrophils (87, 88). As during Spn infection, the absence of IL-36γ during acute pulmonary Kpn infection leads to impaired bacterial clearance in the lungs, higher bacterial dissemination to the bloodstream and increased mortality. The impaired host defense in IL-36γ-/- mice was characterized by impaired production of type-1 cytokines, such as IL-12, IL-23 and IFN-γ at 48 hours post infection (75).

IL-36 cytokines have also been shown to be important in host defense against infection with the Gram-negative bacterium Legionella pneumophila (Lpn). Lpn is the cause of Legionnaires’ disease, which can cause a severe form of pneumonia that is increasing in incidence in the United States and Europe, with an associated mortality of around 10% (89–91). A key characteristic of Lpn is the secretion of virulence factors via a type 4 secretion system. These secreted virulence factors prevent phagosome maturation and acidification, which allows Lpn to escape phagocytic killing by macrophages (92). In a murine model of lung Lpn infection, the expression of IL-36α and IL-36γ, but not IL-36β, is rapidly induced in the lungs following infection (71). In contrast to Spn and Kpn infection, where exclusively IL-36γ exerted the main protective effect, during Lpn infection, the combined effect of IL-36α and IL-36γ were required to protect the host and promote survival (71). The lack of IL-36 signaling was associated with reduced production of chemokines and pro-inflammatory cytokines, leading to impaired recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes into the broncho-alveolar space and to impaired lung Lpn clearance (71). In addition, ex vivo studies performed in alveolar macrophages showed that IL-36 signaling is crucial for macrophage polarization during Lpn infection, as macrophages lacking IL-1Rrp2 showed reduced expression of iNOS (M1 marker), increased expression of Arg-1 (M2 marker) and reduced production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, TNF-α and IFN-γ (71).

The protective role of IL-36 cytokines has also been described in an experimental model of lung BCG infection and in Mtb infection in vivo and in vitro (65, 68, 69, 76). In the case of BCG infection, IL36R-/- mice showed similar host survival (76), but resulted in excessive recruitment of immune cells and excessive lung inflammation compared to WT mice (65, 76). Moreover, isolated splenocytes from IL-36R-/- mice produced lower amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines involved in type 1 responses, such as IFN-γ, IL-6 and TNF-α after stimulation with BCG-antigen or viable bacterium in vitro (65). Finally, IL-36β was shown to act synergistically with IL-2 and IL-12 to promote Th1 polarization in vitro and to also enhance Th1 immune response in vivo during BCG infection (65).

Several cell types such as human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), human monocytes-derived macrophages, THP-1 macrophages, murine bone marrow-derived macrophages and, to a lesser extent, A549 human lung epithelial cell line, produced IL-36γ in response to live Mtb in vitro. This IL-36γ production was shown to depend on recognition of Mtb PAMPs via TLR2 and TLR4 and subsequent signaling via MyD88. In addition, inflammasome-dependent production of active IL-1β and IL-18 was shown to further enhance late-stage IL-36γ production in response to Mtb (68). In Mtb-infected macrophages, IL-36γ induces the activation of Liver X Receptor (LXR) (69), which actively contribute to Mtb immunity in mice by improving bacterial clearance and reducing lung inflammation (93). Mechanistically, LXR induction by IL-36γ triggered the production of antimicrobial peptides such as Cathelicidin, β-defensin 1 and β-defensin 2 (68, 69), improving Mtb clearance by macrophages. These in vitro findings suggest a protective role of the LXR/IL-36γ axis in response to Mtb. However, in vivo mouse models demonstrated that the lack of IL-36 signaling did not significantly affect host defense, lung inflammation or host survival during a pulmonary Mtb infection. This finding indicates that IL-36 signaling possess a limited contribution in the immunity against Mtb in the lungs (76).

In contrast to the beneficial effects of IL-36 cytokines in host defense against the majority of the reported bacterial infections in the lungs thus far, the effects of IL-36 cytokines are detrimental during pulmonary infection with Pa (77). Pa is a Gram-negative pathogenic bacterium that causes acute lower respiratory tract infections in the ICU (94) and chronic infections in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients. Pa pneumonia is characterized by excessive lung inflammation as a consequence of the large number of toxins and virulent factors produced and released by this pathogen to the alveolar lumen (95). Murine alveolar macrophages and alveolar epithelial cells rapidly produce high levels of IL-36α and IL-36γ within the first 24 hours following Pa infection (41, 77). The early production of IL-36γ, but not IL-36α, induces excessive production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-17 (77). IL-36γ-/- and IL-36R-/- mice display reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine production, reduced lung damage, and improved bacterial clearance following Pa infection compared to WT mice, suggesting that the excessive inflammation caused by IL-36γ during PA infection impairs bacterial clearance and exacerbates lung injury (77). Consistent with this finding, IL-36γ-/- and IL-36R-/- mice showed increased survival compared to WT mice (77). Mechanistically, IL-36γ induced the expression of COX-2 and the production of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in alveolar macrophages, which impaired the clearance of Pa by these cells (77). This observation shows that IL-36γ impairs bacterial clearance in a PGE2-dependent manner and is in line with previous studies that describe the immunosuppressive properties of PGE2 in the context of Pa infection (96, 97). Despite this observation, it is unclear why IL-36γ production is detrimental during acute lung Pa infection. One possibility is that Pa secretes proteases such as LasB, known to trigger endogenous host neutrophil proteases such as NE and CatG, that may result in excessive cleavage and activation of IL-36γ during Pa infection leading to uncontrolled inflammation and negatively impacting host survival (41). Further studies analyzing the role of IL-36γ examining clinical isolates with high and low proteolytic activity would provide useful insights regarding this hypothesis.

IL-36 cytokines are also important players in the lung immune response against influenza virus, although their exact function in this context remains uncertain. While one study indicates that IL-36 signaling (IL-36R-/- mice) exerts detrimental effects for the host and increases mortality following infection (78), a later study indicates that IL-36γ enhances host survival (70). Using IL-36R-/- mice, the first study showed that IL-36 signaling exerts a pathogenic response during pulmonary influenza virus infection, which is characterized by severe lung injury and higher mortality compared to WT mice and IL-36γ-/- mice, (78). Absence of IL-36 signaling improved host survival and reduced the infiltration of neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages, reduced the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines involved in neutrophilic inflammation such as IL-6, IL-17A, CXCL-1 at day 6 post infection and limited lung inflammation and injury. Interestingly, IL-36R-/- mice showed increased viral burden in the lungs, indicating that the increased resistance of IL-36R-/- mice to influenza virus is determined by their ability to temper the immune response and prevent lung injury rather than due to enhanced viral clearance (78). This study did not detect a survival difference between WT and IL-36γ-/- mice and suggested that the detrimental effects of IL-36 signaling in influenza virus are driven by IL-36α or IL-36β and not IL-36γ.

In contrast, another study reported that IL-36γ-/- mice display a higher mortality following an acute pulmonary influenza infection and impaired viral clearance at day 6 post infection, suggesting that IL-36γ is required for an effective host defense against influenza virus (70). Interestingly, whereas no major differences in innate cell infiltration to the lungs between IL-36γ-/- and WT mice were identified during the first 6 days of infection, a surprising difference was that IL-36γ-/- mice showed massive apoptosis of alveolar macrophages, leading to a rapid reduction of alveolar macrophages in the lungs of these mice (70). The increased apoptosis of alveolar macrophages observed in IL-36γ-/- mice was thought to be due to enhanced M2 macrophage polarization, as macrophages from IL-36γ-/- mice showed higher expression of M2 markers such as CD206, CD200R in the surface, as well as Retnla transcript. Importantly, the transfer of WT alveolar macrophages to IL-36γ-/- mice improved the survival of these mice in response to influenza to a similar level as in WT mice. Overall, these findings suggest that IL-36γ modulates alveolar macrophage polarization, thereby enhancing macrophage survival and host defense during influenza infection (70). Taken together, these two studies show that IL-36 signaling has a major role in host defense and lung inflammation during influenza infection, although the specific role of each IL-36 cytokine in host defense and lung inflammation, their differential cellular source and how their kinetic production influences the host antiviral response remains to fully understood.

Role of IL-36 Cytokines in Non-Infectious Lung Inflammatory Diseases

The role of IL-36 cytokines in the lungs is not restricted to infectious diseases. Studies have described a potentially important role of the IL-36 pathway in asthma (98, 99), idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (21, 100), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (101, 102), cystic fibrosis (103) and cancer (104). During asthma, the levels of the anti-inflammatory IL36Ra in the serum and sputum of asthmatic patients are reduced compared to healthy controls (98). In vitro data from the same study showed that IL36Ra inhibits the production of various cytokines known to be important drivers of asthmatic inflammation, such as IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and IL-17A in PMBCs and in sputum mononuclear cells (SMNCs) isolated from asthmatic patients pre-stimulated with LPS, that are presumably induced by IL-36 cytokines (98). In addition, using an experimental asthma model of OVA-sensitized mice, it was established that intravenous administration of recombinant IL-36Ra (rIL-36Ra) alleviated the severity of experimental asthma by reducing airway hyper-responsiveness, alveolar inflammation and eosinophil, neutrophil, macrophage, and lymphocyte recruitment. The protective effects of rIL-36Ra were not observed in IL-36R-/- mice, showing that the mechanism by which rIL-36Ra protected the lungs in sensitized mice was through the IL-36 receptor pathway (98).

The in vivo administration of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-38, which also inhibits IL-36R-signaling (55), was shown to reduce the severity of house dust mite (HDM)-induced asthma (99). Specifically, IL-38 administration decreased airway hyper-responsiveness of HDM-treated mice to baseline levels, reduced lung inflammation, BALF eosinophilic recruitment and limited the production of IL-4, IL-5, IL-6 in the lungs. Importantly, IL-38 administration also inhibited the proliferation of Th2 and Th17 cells, prevented the recruitment of ILC2 cells and promoted the proliferation of Treg cells (99). IL-36γ has been found to be upregulated during HDM-induced asthma, triggering a strong inflammatory response in the lungs of sensitized mice (74).

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic lung disease characterized by the progressive loss of lung function. Interestingly, IL-38 is highly expressed in type II pneumocytes in patients with IPF but not in healthy controls (100). Moreover, normal human lung fibroblasts express IL-1Rrp2 at baseline and produce several pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-8, CXCL3, G-CSF and CCL20 in response to IL-36γ (21) ( Figure 5G ). Currently, it is not clear which factors induce IL-38 expression in IPF patients and what the role of this cytokine is in IPF progression. However, as lung fibroblasts respond to IL-36γ and IL-1Rrp2 neutralization has protective effects during intestinal fibrosis (105), it can be speculated that the IL-36 pathway may be a major pathway during lung fibrosis.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a chronic lung inflammatory disease characterized by airflow obstruction. Promising data regarding the role of IL-36 cytokines in the development and severity of COPD has emerged in the last years. Studies have demonstrated that normal human bronchial epithelial cells and primary human bronchial epithelial cells express high amounts of IL-36α, IL-36β, IL-36γ and IL-36Ra after being treated with cigarette smoke components – a causative agent of COPD – in vitro (101, 102). Moreover, smokers with and without COPD presented with elevated levels of IL-36α, and IL-36γ in plasma and BALF at baseline, although no differences in IL-36 cytokines levels were found between non-COPD smokers and COPD smokers (102). Another study showed that IL-36α, and IL-36γ were increased in the sputum of neutrophilic COPD patients, compared to eosinophilic COPD, and were associated with the amount of neutrophils in the sputum (106). Despite the emergence of novel data regarding the role of IL-36 cytokines in COPD, more studies are needed to accurately understand the possible pathogenic role of IL-36 cytokines during COPD.

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a chronic lung disorder caused by genetic mutations leading to functional defects in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), a chloride channel that regulates the flow of chloride ions in epithelial cells (107). CF is characterized by the excessive production of sticky mucus and lung inflammation caused by neutrophilic inflammation and chronic bacterial infection (107). The role of IL-36 cytokines in lung inflammation during CF remains relatively unexplored. However, CF patients usually present with a neutrophil-predominant inflammatory response in sputum supernatants, and massive release of neutrophil elastase (108), and therefore it is highly possible that IL-36 cytokines play a role in lung inflammation and injury in CF. An RNA-seq analysis of bronchial brushings obtained from CF patients and healthy controls showed that IL-36γ gene expression is upregulated in the airways of CF patients (4-fold) compared to healthy controls (103). The expression of IL-36α did not differ between CF patients and healthy controls, while the expression of IL-36β and the anti-inflammatory IL-36Ra were downregulated in CF patients (103). These data suggest that, during CF, IL-36γ but no other members of the IL-36 family may be contributing to the pro-inflammatory environment. Additional studies are needed to corroborate this hypothesis.

A potential protective role of IL-36 signaling has been identified in different types of cancer in mice and humans. In mice, IL-36γ has been shown to promote a Th1 response in a tumor model of B16 cells (67). This anti-tumor response elicited by IL-36γ was characterized by increased production of IFN-γ by CD4+ cells, CD8+ cells, NK cells and γδ T cells, which ultimately resulted in the reduction of tumor size and higher survival (67). In humans, IL-36α expression in the liver of hepatocellular carcinoma patients was found to be negatively correlated with tumor size and vascularization, while IL-36α expression was positively correlated with CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and patient survival (109). Finally, the production of IL-36γ was found to be reduced in late stages of lung squamous cell carcinoma compared to early stages (67). Although more research is needed to elucidate the exact role of IL-36 signaling during lung cancer, altogether these data suggest that IL-36 cytokines may trigger a pro-inflammatory response in the tumor microenvironment, exhibiting anti-tumoral effects in a context where pro-inflammatory signals versus immunosuppressive mechanisms determine tumor elimination or survival.

Potential Therapeutic Modulation of IL-36 Pathway During Lung Inflammation

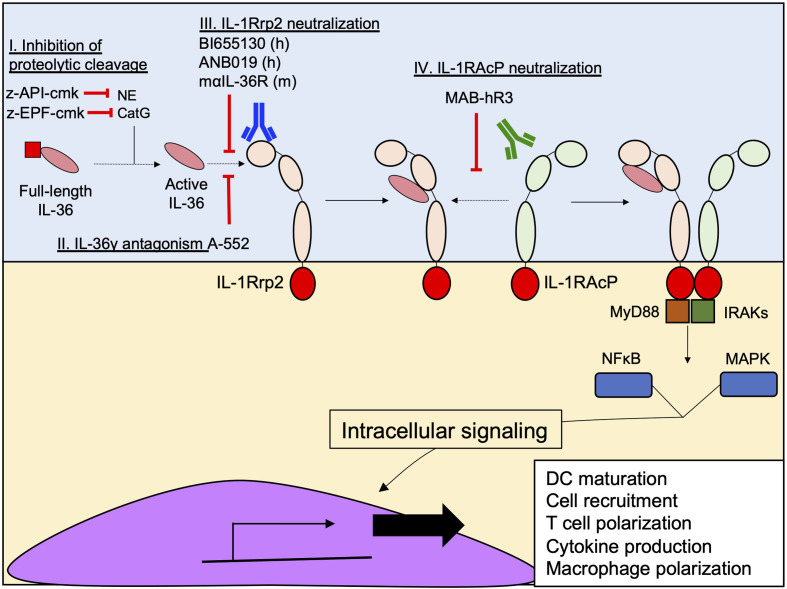

The initial findings regarding the pathogenic effect of IL-36 cytokines in skin psoriasis attracted the attention of scientists to therapeutically exploit the IL-36 pathway to prevent excessive inflammation ( Figure 6 ) (110, 111). Indeed, a neutralizing antibody targeting IL-1Rrp2 (BI655130), designed for the treatment of generalized pustular psoriasis, was evaluated in a phase I clinical trial (NCT02978690) and showed promising results, including no adverse effects and a total pustular clearance in 6 out of 7 patients in 2 weeks of treatment (111). In addition, a second monoclonal antibody (ANB019) designed for the treatment of palmoplantar pustulosis psoriasis and generalized pustular psoriasis is currently in phase II clinical trial (NCT03633396). In addition, a monoclonal rat anti-IL-36R that recognizes the murine version of IL-1Rrp2 has been developed and characterized in mice, in terms of routes of administration, pharmacokinetics, biodistribution and excretion patterns (112). The development of this antibody opens an important window for the therapeutic potential of the IL-36 pathway in pre-clinical studies during different diseases, such as infections and non-infectious lung diseases, in which IL-36 cytokines have been identified as important effectors of inflammation.

Figure 6.

Current therapeutic strategies designed to inhibit IL-36 signaling. Several approaches have been designed to prevent the interaction between IL-36 cytokines and IL-1Rrp2, inhibiting their signaling. (I) Z-EPF-cmk and z-API-cmk Inhibit the proteolytic cleavage of IL-36 by the neutrophil proteases CatG and NE by respectively. (II) Inhibition of IL-36g-IL-1Rrp2 interaction using the small molecule A-552. (III) Monoclonal antibody-mediated neutralization of IL-1Rrp2 by human (BI655130 and ANB019) and murine (maIL-36R) antibodies; and (IV) Neutralization of IL-1RAcP using the monoclonal antibody MAB-hR3.

As discussed in the previous sections, once IL-36 cytokines bind to IL-1Rrp2, a second accessory protein, IL-1RAcP is recruited and triggers downstream inflammatory pathways ( Figure 4A ). One research group has developed a neutralizing monoclonal antibody called MAB-hR3, a humanized IgG1 Fc-LALA monoclonal antibody, – with L234A/L235A substitutions designed to prevent FcγR triggering (113) – produced in albino Zika rabbits. MAB-hR3 targets and neutralizes IL-1RAcP, blocking the IL-36γ-mediated signal in vitro (114). Because MAB-hR3 disrupts the recruitment of IL-1RAcP, other inflammatory signals mediated by IL-1α, IL-1β and IL-33 were also disrupted in vitro and in vivo models of local and systemic inflammation models in mice such as peritonitis, OVA-induced airway allergy and Imiquimod-induced psoriasis (114). Although the neutralization of IL-1RAcP affects the pathway induced by IL-1α, IL-1β and IL-33, its administration has positive effects in the control of the inflammation in OVA-induced allergic airway inflammation and Imiquimod-induced psoriasis. In both cases, MAB-hR3 reduced the infiltration of granulocytes and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-22), reducing the intensity of the inflammation in both diseases (114).

The neutralization strategies against IL-36 signaling have not been restricted to neutralizing antibodies against IL-1Rrp2 or IL-1RAcP. The small molecule, A-552, analogue of the endothelin receptor A antagonist (Ambrisentan), has proved to be a potent antagonist of human and murine IL-36γ, but not IL-36α or IL-36β (115). The inhibitory mechanism of A-552 consists of the ability of A-552 to directly interact with the residues R121 and K123 of IL-36γ through hydrogen bonds, preventing the binding of IL-36γ to IL-1Rrp2 (115). The lack of inhibitory activity of A-552 against IL-36α or IL-36β may be explained by the inability of A-552 to establish hydrogen bonds with IL-36α and IL-36β residues (115). As previously discussed, IL-36 cytokines need to be processed in the N-terminal sequence to be fully active. This proteolytic step is critical for enhancing IL-36 activity and at least one group has taken advantage of this process through the design of peptides pseudo-substrates that specifically inhibit the proteolytic cleavage of IL-36 cytokines in vitro by Cathepsin G (z-EPF-cmk) and Elastase (z-API-cmk) (40). These two peptides were highly efficient in inhibiting the downstream inflammatory activity triggered by each IL-36 cytokine in transfected HeLa IL-36R+ cells and, in combination, completely abrogated the inflammatory effect of these cytokines (40). While targeting neutrophil proteases might seem attractive as a strategy to block IL-36 activity, targeting just neutrophil proteases may prove challenging given that other non-neutrophil proteases are capable of activating IL-36 cytokines. In vivo studies are needed to accurately establish the efficacy of these approaches in different inflammatory disorders.

Conclusions and Future Perspective

IL-36 cytokines are key regulators of the host inflammatory response in infectious and non-infectious lung diseases. Several pro-inflammatory cytokines as well as various PAMPs and DAMPs trigger the expression of il36 genes in epithelial and immune cells. When IL-36 cytokines are released into the extracellular space, these cytokines are N-terminally processed by host proteases such as cathepsin S, neutrophil elastase, cathepsin G and proteinase-3 selectively, as well as, pathogen proteases such as LasB, SpeB and Asp F13 presumably enabling more efficient binding to IL-1Rrp2. IL-1Rrp2/IL-1RAcP heterodimer downstream signaling regulates a variety of inflammatory processes in epithelial and immune cells, including cytokine production, DC maturation, T cell activation, and macrophage polarization. Whereas IL-36α and IL-36γ have been shown to be protective during lung infections with bacteria such as K. pneumoniae, S. pneumoniae and L. pneumophilia, IL-36 cytokines are deleterious during P. aeruginosa infection. Importantly, during influenza infection the role of IL-36 signaling in host defense and survival is controversial and requires further study. The role of IL-36 cytokines during coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) remains to be established. Interestingly, IL36B gene expression in bronchoalveolar lavage cells of asthma patients was recently shown to correlate with bronchial epithelial cell expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2) – an enzyme that mediates the entry of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) into host cells (116, 117).

Regarding the role of IL-36 cytokines in non-infectious lung disorders, the importance of IL-36 cytokines as a driver of inflammatory diseases such as psoriasis is well established and has generated significant interest in the development of therapeutic approaches to inhibit IL-36 signaling. The antitumoral effects of IL-36α and IL-36γ in different types of cancer further exemplify the importance of the IL-36 pathway in enhancing host immune responses, while the strong ability of IL-36γ to induce lung inflammation in the context of asthma, as well as in COPD, emphasizes that the IL-36 pathway needs to be tightly regulated to avoid excessive pathological inflammatory responses. Although IL-36 cytokines have been shown to be upregulated in the lungs of CF patients, further research is needed to establish whether IL-36 signaling plays a protective or deleterious role in the context of CF.

The differential roles of IL-36α, IL-36β and IL-36γ in models of lung inflammation suggest a degree of specificity regarding the responses mediated by the individual IL-36 cytokine in the lungs. How such specificity is achieved is currently not known. Although the recognition of each IL-36 cytokine by IL-1Rrp2 is unique in terms of affinity and specific aminoacidic interactions (54, 56), all the IL-36 family members – except for the antagonistic IL-36Ra – appear to activate similar intracellular pathways that involve MYD88/IRAK and MAPK/NF-kB signaling. Moreover, a recent study showed that whereas isolated murine macrophages and fibroblasts express high levels of IL-36γ in response to heat-killed Kpn, type II alveolar epithelial cells expressed higher levels of IL-36α compared to IL-36γ (102). Finally, given that there is significant overlap in the proteases by which each IL-36 cytokines are activated, we speculate that the distinct roles for individual IL-36 cytokines are influenced by the local milieu. Considering this, we previously reported that Pa protease drives the activity of endogenous host proteases such as NE (47). In addition, LasB cleaves IL-36γ proximal to M19, and in silico docking analyses predict that the M19 and bioactive S18 isoforms bind IL-1Rrp2 similarly (41). Also, specific proteases from S. pyogenes (SpeB) and Aspergillus fumigatus (Asp F13) process IL-36γ to generate the bioactive isoform S18 in vitro (45). Finally, unidentified proteases from S. aureus and T. rubrum were also found to generate the S18 isoform of IL-36γ in vitro (45). Therefore, distinct pathogens generate a local inflammatory and proteolytic environment favoring the induction of and processing of IL-36γ over IL-36α and IL-36β.

Since the discovery of IL-36 cytokines two decades ago, research has provided extensive information about IL-36 cytokine biology and their role in inflammation, putting IL-36 cytokines forward as central effectors of lung inflammation. The IL-36 pathway may be a promising target for therapeutic strategies that focus on modulating the host inflammatory response during inflammatory disorders in the lungs. Therefore, there is a clear need to continue to elucidate the complex regulation of IL-36 cytokines, and biology of IL-36 cytokines in infectious and non-infectious lung diseases.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the University of Pittsburgh Vascular Medicine Institute, the Hemophilia Center of Western Pennsylvania, and the Institute for Transfusion Medicine (HP), the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers; P01 HL114453, R01 HL136143, R01 HL142084, K24 HL143285 (JL), R01 HL123515 (TS).

Author Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or any other sponsoring agency.

Conflict of Interest

JL discloses a paid consultantship with Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc. that is unrelated to the work presented in this manuscript.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Glossary

| AbR | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor |

| ACE-2 | Angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 |

| ARE | Antioxidant Response Elements |

| Arg-1 | Arginase-1 |

| BALF | Broncho-alveolar lavage fluid |

| BCG | Mycobacterium bovis BCG |

| BMDCs | bone-marrow-derived dendritic cells |

| BMDMs | Bone marrow derived macrophages |

| CatG | Cathepsin G |

| CatS | Cathepsin S |

| CCL4 | C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 4 |

| CCL11 | C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 11 |

| CCL20 | C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 20 |

| CF | Cystic fibrosis |

| CFTR | Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| CXCL3 | C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 3 |

| CXCL-8 | C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 8 |

| DCs | dendritic cells |

| dsRNA | Double strain RNA |

| DSS | Dextran Sulfate Sodium |

| ERK1/2 | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase ½ |

| F13 | Aspergillus factor 13 |

| FcγR | Fc gamma receptors |

| FoxP3 | Forkhead box P3 |

| FSL-1 | Trifluoroacetate salt |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| G-CSF | Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor |

| HDM | House dust mite |

| IκBζ | NF-κB inhibitor zeta |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| IFN-γ | Interferon gamma |

| iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| IL-1F5 | Interleukin-1 family member 5 |

| IL-1F6 | Interleukin-1 family member 6 |

| IL-1F8 | Interleukin-1 family member 8 |

| IL-1F9 | Interleukin-1 family member 9 |

| IL-1α | Interleukin-1 alpha |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-1Rrp2 | IL-1 Receptor-Related protein 2 |

| IL-1RAcP | Interleukin-1 receptor accessory protein |

| IL-2 | Interleukin-2 |

| IL-4 | Interleukin-4 |

| IL-5 | Interleukin-5 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-8 | Interleukin-8 |

| IL-9 | Interleukin-9 |

| IL-12 | Interleukin-12 |

| IL-13 | Interleukin-13 |

| IL-17A | Interleukin-17A |

| IL-17F | Interleukin-17F |

| IL-18 | Interleukin-18 |

| IL-22 | Interleukin-22 |

| IL-23A | Interleukin-23A |

| IL-33 | Interleukin-33 |

| IL-36α | Interleukin-36 alpha |

| IL-36β | Interleukin-36 beta |

| IL-36γ | Interleukin-36 gamma |

| IL-36Ra | Interleukin-36 receptor antagonist |

| ILC2 | Type 2 innate lymphoid cells |

| IPF | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis |

| IRAK | Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase |

| IRF6 | Interferon response factor 6 |

| JNK1/2 | c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase 1/2 |

| Kpn | Klebsiella pneumoniae |

| LasB | Elastase B |

| Lpn | Legionella pneumophila |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharides |

| LXR | Liver X Receptor |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MIKs | immortalized keratinocytes |

| Mtb | Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

| MyD88 | Myeloid differentiation primary response 88 |

| NE | Neutrophil elastase |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| Notch2 | Neurogenic locus notch homolog protein 2 |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2 |

| OVA | Ovalbumin |

| P3 | Proteinase-3 |

| P-TEFb | Positive transcription elongation factor |

| Pa | Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| PAM3CSK4 | N-Palmitoyl-S-[2,3-bis(palmitoyloxy)-(2RS)-propyl]- [R]-cysteinyl-[S]-seryl-[S]-lysyl-[S]-lysyl-[S]-lysyl-[S]-lysine |

| PAMPs | Pathogen-associated molecular patterns |

| PBMCs | Peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| PMA | Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate |

| Poly I:C | Polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid |

| Retnla | Resistin-like alpha transcript |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| SEC | Super elongation complex |

| SMNCs | Sputum mononuclear cells |

| SpeB | Streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin B |

| Spn | Streptococcus pneumoniae |

| STAT | Signal transducer and activator of transcription |

| T-bet | T-box transcription factor TBX21 |

| tBHQ | tert-butylhydroquinone |

| TIR | Toll/interleukin-1 receptor |

| Th1 | T helper cell type 1 |

| Th2 | T helper cell type 2 |

| Th9 | T helper cell type 9 |

| Th17 | T helper cell type 17 |

| TLR | Toll-like receptor |

| TNF-α | Tumour necrosis factor alpha |

| TRIF | TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β |

| VDR | Vitamin D receptor |

References

- 1. Bassoy EY, Towne JE, Gabay C. Regulation and Function of Interleukin-36 Cytokines. Immunol Rev (2018) 281(1):169–78. doi: 10.1111/imr.12610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dunn E, Sims JE, Nicklin MJ, O’Neill LA. Annotating Genes With Potential Roles in the Immune System: Six New Members of the IL-1 Family. Trends Immunol (2001) 22(10):533–6. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02034-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nicklin MJ, Barton JL, Nguyen M, FitzGerald MG, Duff GW, Kornman K. A Sequence-Based Map of the Nine Genes of the Human Interleukin-1 Cluster. Genomics (2002) 79(5):718–25. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.6751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Taylor SL, Renshaw BR, Garka KE, Smith DE, Sims JE. Genomic Organization of the Interleukin-1 Locus. Genomics (2002) 79(5):726–33. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.6752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kumar S, McDonnell PC, Lehr R, Tierney L, Tzimas MN, Griswold DE, et al. Identification and Initial Characterization of Four Novel Members of the Interleukin-1 Family. J Biol Chem (2000) 275(14):10308–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.10308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Busfield SJ, Comrack CA, Yu G, Chickering TW, Smutko JS, Zhou H, et al. Identification and Gene Organization of Three Novel Members of the IL-1 Family on Human Chromosome 2. Genomics (2000) 66(2):213–6. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smith DE, Renshaw BR, Ketchem RR, Kubin M, Garka KE, Sims JE. Four New Members Expand the Interleukin-1 Superfamily. J Biol Chem (2000) 275(2):1169–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Debets R, Timans JC, Homey B, Zurawski S, Sana TR, Lo S, et al. Two Novel IL-1 Family Members, IL-1 Delta and IL-1 Epsilon, Function as an Antagonist and Agonist of NF-Kappa B Activation Through the Orphan IL-1 Receptor-Related Protein 2. J Immunol (2001) 167(3):1440–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dinarello C, Arend W, Sims J, Smith D, Blumberg H, O’Neill L, et al. IL-1 Family Nomenclature. Nat Immunol (2010) 11(11):973. doi: 10.1038/ni1110-973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sims JE, Nicklin MJ, Bazan JF, Barton JL, Busfield SJ, Ford JE, et al. A New Nomenclature for IL-1-Family Genes. Trends Immunol (2001) 22(10):536–7. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02040-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]