Abstract

Objective

To evaluate relationships between coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)–related stress and work intentions in a sample of US health care workers.

Patients and Methods

Between July 1 and December 31, 2020, health care workers were surveyed for fear of viral exposure or transmission, COVID-19–related anxiety or depression, work overload, burnout, and intentions to reduce hours or leave their jobs.

Results

Among 20,665 respondents at 124 institutions (median organizational response rate, 34%), intention to reduce hours was highest among nurses (33.7%; n=776), physicians (31.4%; n=2914), and advanced practice providers (APPs; 28.9%; n=608) while lowest among clerical staff (13.6%; n=242) and administrators (6.8%; n=50; all P<.001). Burnout (odds ratio [OR], 2.15; 95% CI, 1.93 to 2.38), fear of exposure, COVID-19–related anxiety/depression, and workload were independently related to intent to reduce work hours within 12 months (all P<.01). Intention to leave one’s practice within 2 years was highest among nurses (40.0%; n=921), APPs (33.0%; n=694), other clinical staff (29.4%; n=718), and physicians (23.8%; n=2204) while lowest among administrators (12.6%; n=93; all P<.001). Burnout (OR, 2.57; 95% CI, 2.29 to 2.88), fear of exposure, COVID-19–related anxiety/depression, and workload were predictors of intent to leave. Feeling valued by one’s organization was protective of reducing hours (OR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.59 to 0.72) and intending to leave (OR, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.36 to 0.45; all P<.01).

Conclusion

Approximately 1 in 3 physicians, APPs, and nurses surveyed intend to reduce work hours. One in 5 physicians and 2 in 5 nurses intend to leave their practice altogether. Reducing burnout and improving a sense of feeling valued may allow health care organizations to better maintain their workforces postpandemic.

Abbreviations and Acronyms: AMA, American Medical Association; APP, advanced practice provider; IRB, Institutional Review Board; MAR/MCAR, missing at random vs missing completely at random; OR, odds ratio

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic placed unprecedented stresses on health care workers with work overload, job insecurity, worries about personal and family safety, and exposure to patients dying at unaccustomed rates. Early reports regarding physicians and/or nurses in Wuhan, China,1,2 Israel,3 Italy,4,5 and the United States6, 7, 8, 9 reported high levels of anxiety, depression, and/or sleep disturbances. A single-institution study of frontline workers found that 39% had symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and/or anxiety.8 Still, there is scarce knowledge about the consequences of COVID-19 for maintenance of the health care workforce.

Unlike many previous crises, the COVID-19 pandemic has persisted for more than a year, raising concerns about the impact of the pandemic on occupational stress (burnout), mental health (anxiety and depression), and work intentions of US health care workers. A study of physicians in 2017 demonstrated that burnout is associated with higher rates of intention to reduce clinical effort, leave current practice, or leave medicine altogether.10 Longitudinal studies have found that burnout among physicians is associated with 1.5 to 2 times the likelihood of leaving an organization within 2 years.11, 12, 13, 14 It is estimated that turnover and reduced clinical hours due to physician burnout in the United States cost $4.6 billion annually.15,16 Nurses with symptoms of burnout have been found to have greater absenteeism and poor work performance.17 Stressful work environments and burnout are among the top 5 reasons nurses give for leaving their jobs.18 It is thus timely to study work intentions of clinicians as we are well into the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The aim of our study is to evaluate the work intentions of US health care workers, including physicians, advanced practice providers (APPs), nurses, and other clinical role types, along with clerical workers, housekeepers, and administrators. We hypothesized that stress, burnout, and the factors that could lead to them (anxiety and depressive symptoms, fear of exposure or transmission, and work overload) would be associated with greater intention to reduce work hours or leave current practice. Additionally, we sought to determine factors associated with lower rates of intention to reduce hours or leave, including feeling valued by one’s organization, and an enhanced sense of meaning and purpose.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

The Coping With COVID study has been described in detail elsewhere.9 In brief, a survey of health care workers in both clinical and nonclinical roles was administered by multiple health care organizations across 30 states in both rural and urban settings at no cost beginning April 2020. Approximately 100 organizations, many of which had previously worked on well-being initiatives with the American Medical Association, were initially invited to participate. Others learned of the survey through American Medical Association news stories or academic presentations. Registration was available at a publicly available website and open to any organization with more than 100 physicians. The current study includes data collected between July 1, 2020, and December 31, 2020.

Resident physicians were excluded from this analysis because their clinical hours and likelihood of leaving current practice are largely determined by progression through their training program. The APPs, including nurse practitioners and physician assistants, were included; these are clinicians who practice alongside physicians, with more limited training and oftentimes with a more limited scope of care. Prior articles have addressed 2373 physicians surveyed April 4 to May 27, 2020,9 and 20,947 health care workers surveyed between May and October 202019 but have not addressed intent to leave or reduce work hours, questions that were added to our survey June 24, 2020.

Each institution determined the frequency of reminder emails. Responses were returned to a databank at Forward Health Group, in Madison, Wisconsin. The Hennepin Healthcare Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the University of Illinois-Chicago IRB both deemed this study a quality improvement/program evaluation project that was exempt from IRB requirements.

Survey

The Coping With COVID survey, reported elsewhere,9 includes demographic items (race/ethnicity, sex, years in practice, outpatient vs inpatient physician, and work role) and single-item questions on overall stress (referred to as COVID stress), burnout, fear of infection and transmission, perceived anxiety or depression, work overload, sense of meaning and purpose, and feeling valued by one’s organization. These are included in the Supplemental Appendix (available online at https://mcpiqojournal.org) and were scored on 5-point scales with the top 2 categories considered as “high stress” or “high fear.”

Burnout was assessed using the Mini Z single-item burnout measure, which has been validated against the emotional exhaustion subscale of the Maslach Burnout Inventory.20, 21, 22 Construct validity was assessed with internal consistency measures and with correlations with the validated burnout score. Items from a previous national physician survey10 were modified for use to assess work intentions as follows: “What is the likelihood that you will reduce the number of hours you devote to clinical care over the next 12 months?” and “What is the likelihood that you would leave your practice within 2 years?,” with response options of “none,” “slight,” “moderate,” “likely,” and “definitely.” Responses of “moderately," “likely,” and “definitely” were considered likely to reduce hours or leave practice. This is concordant with definitions used in many,11,23,24 although not all,10 prior articles.

The COVID-19 load was measured by the daily new cases per 100,000 people (7-day moving average) per organization location by county obtained from July 1 to December 31, 2020.25

Statistical Analyses

Initially, descriptive statistics were run on all variables, and missing data were analyzed for MAR/MCAR (missing at random vs missing completely at random). A 2-level (respondents nested in organizations) multiple logistic regression analysis was performed on the subsample of physicians, APPs, and nurses (n=11,306) to identify variables associated with intent to reduce clinical work in the next 12 months and/or leave their current practice position in the next 24 months. We used mixed-effects logistic regression for modeling observations in the same organizations because they share common cluster-level random effects. Variables measured on 4-point Likert scales were treated as binary, with responses of “moderately” and “to a great extent” considered positive. Three adjusting covariates were also included in the models: (1) COVID-19 load, described previously, was treated as a continuous variable; (2) sex, as a binary variable, to use only males and females; and (3) a binary variable for persons of color, including African Americans, Latinx, Asian, Native American, and those endorsing “other” vs Caucasian. Analyses were performed using Stata, version 17 (StataCorp; 2021).

Results

A total of 3% missing data for the entire sample was detected. Based on Little’s test for MCAR26 on the outcome and predictor variables, we were able to accept the assumption of MCAR (missing completely at random) in the data; χ2=35.46 (df=26); P=.1019. Due to MCAR and the large sample size, imputation was not considered and listwise deletion was used.

The median organizational response rate was 34%. The demographic characteristics of health care workers in our sample of 124 institutions are shown in Table 1. Of the 20,665 respondents, 60.41% (n=12,484) were women and 31.01% (n=6408) were men, with 8.37% (n=1730) preferring not to identify sex and 0.21% (n=43) identifying as nonbinary. Race/ethnicity distribution was 69.83% (n=14,431) white, 10.86% (n=2245) Asian/Pacific Islander, 2.04% (n=422) black, 3.3% (n=681) Hispanic, and 11.98% (n=2475) preferring not to identify their race or ethnicity. Physicians represented 44.84% (n=9266) of respondents; nurses, 11.14% (n=2302); APPs, 10.17% (n=2101); other clinical roles such as medical and nursing assistants, social workers, respiratory therapists, and physical therapists, 11.83% (n=2445); and administrators, 3.57% (n=738); with a small proportion represented by housekeeping and food service (0.53%; n=110).

Table 1.

Personal and Professional Characteristics of Responding Health Care Workers

| Personal Characteristic | N=20,665 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 2475 | 12.0 |

| White/Caucasian | 14,431 | 69.8 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 681 | 3.30 |

| Black/African American | 422 | 2.0 |

| Native American or American Indian | 54 | 0.3 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2245 | 10.9 |

| Other (please specify) | 357 | 1.7 |

| Sex | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 1730 | 8.4 |

| Male | 6408 | 31.0 |

| Female | 12,484 | 60.4 |

| Nonbinary/third gender | 43 | 0.2 |

| Years in practice | ||

| 1-5 | 4320 | 20.9 |

| 6-10 | 3639 | 17.6 |

| 11-15 | 3017 | 14.6 |

| 16-20 | 2285 | 11.1 |

| <20 | 5552 | 26.9 |

| APP | 1852 | 9.0 |

| Setting | ||

| Missing | 3415 | 16.5 |

| Inpatient | 9109 | 44.1 |

| Outpatient | 8141 | 39.4 |

| Role type grouping | ||

| Physicians (nonresident) | 9266 | 44.84 |

| APP | 2101 | 10.17 |

| Nurses | 2302 | 11.14 |

| Other clinical (therapists, laboratory technicians, medical assistants, nursing assistants) | 2445 | 11.83 |

| Clerical roles (receptionist/scheduler) | 1778 | 8.60 |

| Administrators (finance, information technology, researcher) | 738 | 3.57 |

| Housekeeping/food service | 110 | 0.53 |

| Other | 1925 | 9.32 |

APP, advanced practice provider.

Rates of high stress, fear of exposure of self or family, increased anxiety/depression related to COVID-19, high workload, feeling burned out, feeling valued by one’s organization, and feeling an enhanced sense of purpose by being a part of the COVID-19 response by role type are reported in Table 2. Burnout was reported in 48% (4438/9266) of physicians and 63% (1451/2301) of nurses. Forty-three percent (1001/2301) of nurses described anxiety or depression, and 56% (n=1288) noted work overload. Feeling valued, a burnout mitigator,9,19 was present about half the time, though in some groups it was closer to one third.

Table 2.

Stress Factors, Mitigators, and Intention to Leave Current Position, by Health Care Worker Rolea

| Stress Factors |

Mitigators |

Outcomes |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Stress, no. (%) | Fear Exposure or Transmission, no. (%) | Anxiety or Depression, no. (%) | High Work Load, no. (%) | Burned Out, no. (%) | Feeling Valued, no. (%) | Enhanced Purpose, no. (%) | Intent to Leave, no. (%)b | Intent to Reduce Hours, no. (%)c | |

| Physician n=9266 (44.8%) | 3125 (33.7) | 5322 (57.4) | 2385 (25.7) | 3670 (39.6) | 4438 (47.9) | 4661 (50.3) | 3300 (35.6) | 2204 (23.8) | 2914 (31.4) |

| Advanced practice provider n=2101 (10.2%) | 685 (32.6) | 1233 (58.7) | 737 (35.1) | 866 (41.2) | 1129 (53.7) | 882 (42.0) | 694 (33.0) | 694 (33.0) | 608 (28.9) |

| Nurse n=2,301 (11.1%) | 861 (37.4) | 1460 (63.4) | 1001 (43.5) | 1288 (56.0) | 1451 (63.1) | 701 (30.5) | 728 (31.6) | 921 (40.0) | 776 (33.7) |

| Other clinical roles n=2445 (11.1%) | 843 (34.5) | 1475 (60.3) | 1035 (42.3) | 1244 (50.9) | 1435 (58.7) | 863 (35.3) | 894 (36.6) | 718 (29.4) | 657 (26.9) |

| Clerical roles n=1778 (8.6%) | 598 (33.6) | 988 (55.6) | 671 (37.7) | 868 (48.8) | 878 (49.4) | 792 (44.5) | 707 (39.8) | 379 (21.3) | 242 (13.6) |

| Administrator n=738 (3.6%) | 193 (26.2) | 394 (53.4) | 249 (33.7) | 287 (38.9) | 323 (43.8) | 372 (50.4) | 194 (26.3) | 93 (12.6) | 50 (6.8) |

| Housekeeper n=110 (0.5%) | 19 (17.3) | 53 (48.2) | 34 (30.9) | 43 (39.1) | 45 (40.9) | 41 (37.3) | 42 (38.2) | 26 (23.6) | 21 (19.0) |

| Other n=1925 (9.3%) | 569 (29.6) | 1065 (55.3) | 666 (34.6) | 787 (40.9) | 892 (46.3) | 810 (42.1) | 648 (33.7) | 474 (24.6) | 347 (18.0) |

N=20,665. Other clinical roles include therapists, laboratory technicians, medical assistants, and nursing assistants. Clerical roles includes receptionists and schedulers.

Percentage of all respondents within a role type who expressed an intention to leave.

Percentage of all respondents within a role type who expressed an intention to reduce work hours.

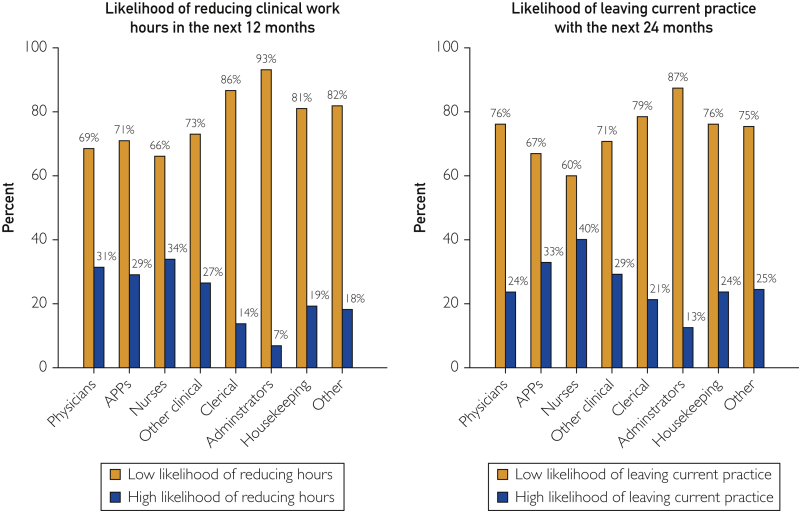

Work plans of surveyed health care workers are portrayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Work intentions of US health care workers by role and presence or absence of burnout (N=20,665). APP, advanced practice provider.

With respect to the likelihood of reducing clinical work hours in the next 12 months, 33.7% (776/2301) of nurses, 31.4% (2914/9266) of physicians, 28.9% (608/2101) of APPs, 13.6% (242/1778) in clerical roles, and 6.8% (50/738) of administrators reported it was “moderately,” “likely,” or “definite” that they would reduce work hours in the next 12 months.

With respect to the likelihood of leaving current practice in the next 24 months, 40.0% (921/2301) of nurses, 33.0% (694/2101) of APPs, 23.8% (2204/9266) of physicians, 21.3% (379/1778) of those in clerical roles, and 12.6% (93/738) of administrators indicated it was “moderately,” “likely,” or “definite” they would leave their current practice within the next 2 years.

Multilevel Multivariable Analyses

In the multilevel (respondents nested within organizations) multiple logistic regression analysis for the subset of physicians, APPs, and nurses, we sought to identify variables associated with intent to reduce work hours or leave current practice (Table 3). After adjusting for COVID-19 exposure,2 respondent race, sex, and years in practice, physicians, APPs, and nurses who were burned out (odds ratio [OR], 2.15; 95% CI, 1.93 to 2.38), in practice more than 20 years (OR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.46 to 1.76), had greater fear of exposure/transmission (OR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.18 to 1.42), had high reported rates of anxiety/depression (OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.13 to 1.39), or endorsed high or very high workload (OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.20 to 1.47) had significantly greater intentions to reduce work hours in the next 12 months. In contrast, those who felt highly valued by their organization (OR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.59 to 0.72) were less likely to intend to reduce work in the next 12 months.

Table 3.

Multivariable Multilevel Analysis of Predictor Variables for Intent to Reduce Work Hours or Leave the Current Practice in Subset of Physicians, APPs, and Nurses

| Intent to Reduce Hours (n=11,306) Organizations = 124 |

Intent to Leave Practice (n=11,306) Organizations = 124 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI |

P | OR | 95% CI |

P | |||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Years | ||||||||

| >20 | 1.60 | 1.46 | 1.76 | <.01 | 2.63 | 2.37 | 2.91 | <.01 |

| Stress | ||||||||

| High | 1.23 | 1.11 | 1.36 | <.01 | 1.37 | 1.22 | 1.53 | <.01 |

| Fear | ||||||||

| High | 1.29 | 1.18 | 1.42 | <.01 | 1.16 | 1.05 | 1.29 | <.01 |

| Anxiety/depression | ||||||||

| High | 1.25 | 1.13 | 1.39 | <.01 | 1.32 | 1.18 | 1.47 | <.01 |

| Workload | ||||||||

| High | 1.33 | 1.20 | 1.47 | <.01 | 1.23 | 1.10 | 1.37 | <.01 |

| Burnout | ||||||||

| High | 2.15 | 1.93 | 2.38 | <.01 | 2.57 | 2.29 | 2.88 | <.01 |

| Valued | ||||||||

| High | 0.65 | 0.59 | 0.72 | <.01 | 0.40 | 0.36 | 0.45 | <.01 |

| Purpose | ||||||||

| High | 0.92 | 0.83 | 1.01 | .08 | 0.85 | 0.77 | 0.95 | <.01 |

| People of color | ||||||||

| People of color | 0.97 | 0.87 | 1.09 | .71 | 0.75 | 0.66 | 0.86 | <.01 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 0.90 | 0.82 | 0.99 | .03 | 0.87 | 0.79 | 0.97 | .01 |

| COVID-19 load | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | .62 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | .62 |

| McKelvey & Zavoina pseudo R2 | 0.14 | 0.27 | ||||||

| Intraclass correlation coefficient | 0.014 | 0.051 | ||||||

APP, advanced practice provider; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; OR, odds ratio.

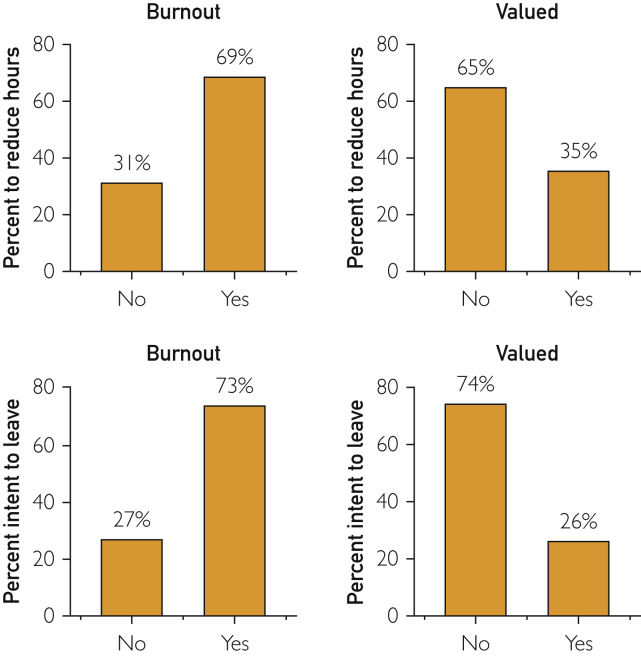

Similarly, physicians, APPs, and nurses who were in practice more than 20 years (OR, 2.63; 95% CI, 2.37 to 2.91), burned out (OR, 2.57; 95% CI, 2.29 to 2.88), had high fear of exposure/transmission (OR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.29), had high anxiety/depression (OR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.18 to 1.47), or endorsed high workload (OR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.10 to 1.37) or COVID-related stress (OR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.22 to 1.53) were more likely to intend to leave their practice within the next 24 months. In contrast, those who felt highly valued by their organization (OR, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.36 to 0.45) or a strong sense of meaning and purpose in their work (OR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.77 to 0.95) were less likely to intend to leave their practice within the next 24 months (Table 3). As shown in Figure 2, burnout and feeling valued are both strongly related to work intentions, in opposite directions.

Figure 2.

Relationship between burnout, feeling valued by one’s organization, and work intentions of US physicians, advanced practice providers (APPs), and nurses (N = 11,306). No burnout = “enjoy my work, no symptoms of burnout,” “under stress, less energy, but I don’t feel burned out.” Yes burnout = “beginning to burn out,” symptoms won’t go away,” “completely burned out.” No “feeling valued” = “not at all” or “somewhat.” Yes “feeling valued” = “moderately” or “to a great extent.”

COVID-19 load was not associated with intention to reduce clinical hours or leave the practice. Female workers (physicians, APPs, or RNs) were significantly less likely to intend to reduce hours or leave the practice, whereas persons of color were significantly less likely to leave the practice but not reduce hours. The overall pseudo R2 or percent of variance explained by the model to predict intent to reduce work hours was 14%, and for intent to leave practice, was 27%.

Discussion

In this national study of 20,655 health care workers across multiple role types, we found that approximately one-third of physicians, APPs, and nurses intend to reduce work hours in the next 12 months. Furthermore, 1 of 5 physicians and 2 of 5 nurses are moderately likely or higher to leave their current practice within 2 years. Because multiple studies have demonstrated that intent to leave among physicians correlates with actual departures,27, 28, 29 these findings are of concern. Costs of replacing health care workers are also substantial. Replacing a nurse may cost up to 1.2 to 1.3 times their annual salary.30,31 Replacing physicians may cost $250,000 to more than $1.0 million per physician.15,23,32 The aggregate cost of physicians reducing or cutting back attributable to burnout alone is estimated at $4.6 billion annually in the United States.15 Additional excessive health care costs are borne by payers in the first year after patients lose their primary care physicians for any reason.16

Higher levels of burnout, stress, workload, fear of infection, anxiety/depression due to COVID-19, and years in practice are each associated with greater intention to reduce work hours and leave one’s current practice. In contrast, feeling highly valued by one’s organization is associated with lower such intentions. To our surprise, COVID-19 load by county was not associated with intent to reduce work hours or leave current practice, although individual exposure to COVID-19 was not determined in the current study.

Our findings have implications for the adequacy of the US health care workforce. Nurses, physicians, and APPs are at highest risk for intention to reduce clinical work hours or leave their current practice. Prior literature has shown that approximately 25% to 35% of physicians who express intention to leave carry out that intention within 2 to 3 years.11,28,29 It would be challenging during ordinary times and even more so were there to be further COVID-19 surges, if a substantial portion of the 40.0% (921/2301) of nurses and 23.8% (2204/9266) of physicians who expressed an intention to leave left their positions.

A recent post in the management sphere33 predicts a “tsunami” of workers leaving their roles when the pandemic ends. In their survey of non–health care workers, one half are seeking other jobs and 25% say they will quit their jobs. They refer to this as “pent-up turnover.” The US health care system may face a similar workforce shortage post–COVID-19 due to such pent-up intentions.

Our study provides health care leaders guidance as they consider interventions to improve workforce retention. To meet the societal need for medical care in the future, it will be necessary not only to train new health care workers but also to address attrition in the current health care workforce.34 A comprehensive approach by national policy makers and health care delivery institutions will be necessary to address this challenge.35, 36, 37, 38, 39 Here, we briefly mention potential approaches for some of the key factors associated with intent to reduce hours or leave.

-

1.

Stress and burnout: leaders can focus on providing adequate personal protective equipmen, creating supportive environments,40,41 ensuring access to confidential services for mental health, and reducing work overload through better teamwork.42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47 Applying a syst0ems approach to interventions, aimed at improving organizational culture35,48 and practice efficiency,45,49, 50, 51, 52 will be most successful at reducing burnout.

-

2.

Feeling valued by one’s organization: this was associated with less intent to reduce hours or leave one’s job. Mechanisms to enhance health care workers' sense of value are needed. Transparent communication, support for child care, and rapid training to support deployment to unfamiliar units may demonstrate organizational appreciation to workers.53, 54, 55, 56

Our cross-sectional study is subject to a number of limitations, including inability to determine cause and effect. The median organizational response rate was 34%. Test-retest reliability is not known for the Coping With COVID survey. Because organizations surveyed their own health care workforces, we do not have information on response rates by role. Many survey items were single-item measures that are typically not as robust psychometrically as multi-item measures. We do not know how many health care workers who indicate an intent to cut back or leave current practice will carry out these intentions. Our sample is a convenience sample and to the extent that it may be overrepresented by organizations that had been active in addressing system factors that affect well-being pre-pandemic, we may be underestimating the scope of the problem with health care workers’ intent to leave or cut back. Finally, without a measure of individual COVID-19 exposure, we may be underestimating the impact of exposure when we controlled for COVID-19 load.

Conclusion

Approximately one-third of physicians of physicians and nurses intend to reduce work hours in the next 12 months. Furthermore, 1 in 5 physicians and 2 in 5 nurses intend to leave their current practice within 2 years. If these clinicians follow through on these intentions, this has significant implications for the future health care workforce. Burnout, workload, and COVID-19–associated stresses were associated with intent to reduce hours or leave, whereas feeling valued was strongly associated with lower odds of reducing hours or leaving. Future research should investigate whether addressing predictors of burnout and emphasizing mitigators such as positive organizational cultures and making workers feel valued could avert a potential health care workforce crisis in the wake of COVID-19.

Footnotes

Grant Support:American Medical Association.

Potential Competing Interests: Dr Linzer is supported through Hennepin Healthcare for training and research in physician burnout prevention by the American Medical Association (AMA), American College of Physicians, American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation, the Optum Office for Provider Advancement, and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. He is also supported by National Institutes of Health and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and consults on a grant for Harvard University on work conditions and diagnostic accuracy. Dr Stillman is supported through Hennepin Healthcare by the AMA and the Optum Office for Provider Advancement for work on burnout prevention. Dr Sinsky is employed by the AMA. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and should not be interpreted as AMA policy.

Supplemental material can be found online at https://mcpiqojournal.org. Supplemental material attached to journal articles has not been edited, and the authors take responsibility for the accuracy of all data.

Supplemental Online Material

References

- 1.Lai J., Ma S., Wang Y., et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li W., Frank E., Zhao Z., et al. Mental health of young physicians in China during the novel coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6):e2010705. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mosheva M., Hertz-Palmor N., Dorman Ilan S., et al. Anxiety, pandemic-related stress and resilience among physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37(10):965–971. doi: 10.1002/da.23085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Girolamo G., Cerveri G., Clerici M., et al. Mental health in the coronavirus disease 2019 emergency—the Italian response. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(9):974–976. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossi R., Socci V., Pacitti F., et al. Mental health outcomes among frontline and second-line health care workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Italy. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5):e2010185. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez R.M., Medak A.J., Baumann B.M., et al. Academic emergency medicine physicians' anxiety levels, stressors, and potential stress mitigation measures during the acceleration phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(8):700–707. doi: 10.1111/acem.14065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delaney R.K., Locke A., Pershing M.L., et al. Experiences of a health system’s faculty, staff, and trainees’ career development, work culture, and childcare needs during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4):e213997. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.3997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feingold J.H., Peccoralo L., Chan C.C., et al. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on frontline health care workers during the pandemic surge in New York City. Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks) 2021;5 doi: 10.1177/2470547020977891. 2470547020977891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linzer M., Stillman M., Brown R., et al. Preliminary report: US physician stress during the early days of the COVID 19 pandemic. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2021;5(1):127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2021.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sinsky C.A., Dyrbye L.N., West C.P., Satele D., Tutty M., Shanafelt T.D. Professional satisfaction and the career plans of US physicians. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2017;92(11):1625–1635. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamidi M.S., Bohman B., Sandborg C., et al. Estimating institutional physician turnover attributable to self-reported burnout and associated financial burden: a case study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):851. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3663-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shanafelt T.D., Mungo M., Schmitgen J., et al. Longitudinal study evaluating the association between physician burnout and changes in professional work effort. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(4):422–431. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willard-Grace R., Knox M., Huang B., Hammer H., Kivlahan C., Grumbach K. Burnout and health care workforce turnover. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(1):36–41. doi: 10.1370/afm.2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Windover A.K., Martinez K., Mercer M.B., Neuendorf K., Boissy A., Rothberg M.B. Correlates and outcomes of physician burnout within a large academic medical center. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(6):856–858. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han S., Shanafelt T.D., Sinsky C.A., et al. Estimating the attributable cost of physician burnout in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(11):784–790. doi: 10.7326/M18-1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sabety A.H., Jena A.B., Barnett M.L. Changes in health care use and outcomes after turnover in primary care. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;181(2):186–194. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.6288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dyrbye L.N., Shanafelt T.D., Johnson P.O., Johnson L.A., Satele D., West C.P. A cross-sectional study exploring the relationship between burnout, absenteeism, and job performance among American nurses. BMC Nurs. 2019;18:57. doi: 10.1186/s12912-019-0382-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah M.K., Gandrakota N., Cimiotti J.P., Ghose N., Moore M., Ali M.K. Prevalence of and factors associated with nurse burnout in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2036469. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prasad K., McLoughlin C., Stillman M., et al. Prevalence and correlates of stress and burnout among U.S. healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national cross-sectional survey study. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;35:100879. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brady K.J.S., Ni P., Carlasare L., et al. Establishing crosswalks between common measures of burnout in US physicians. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06661-4 J Gen Intern Med. Published online March 31, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Olson K., Sinsky C., Rinne S.T., et al. Cross-sectional survey of workplace stressors associated with physician burnout measured by the Mini-Z and the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Stress Health. 2018;35(2):157–175. doi: 10.1002/smi.2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rohland B.M., Kruse G.R., Rohrer J.E. Validation of a single-item measure of burnout against the Maslach Burnout Inventory among physicians. Stress Health. 2004;20(2):75–79. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buchbinder S.B., Wilson M., Melick C.F., Powe N.R. Estimates of costs of primary care physician turnover. Am J Manag Care. 1999;5(11):1431–1438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linzer M., Manwell L.B., Williams E.S., et al. MEMO (Minimizing Error, Maximizing Outcome) Investigators. Working conditions in primary care: physician reactions and care quality. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(1):28–36. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-1-200907070-00006. W26-W29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Health BUSoP COVID-19 risk levels by county. 2020. https://globalepidemics.org/key-metrics-for-covid-suppression/

- 26.Little R.J.A. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J Am Stat Assoc. 1988;83(404):1198–1202. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buchbinder S.B., Wilson M., Melick C.F., Powe N.R. Primary care physician job satisfaction and turnover. Am J Manag Care. 2001;7(7):701–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hann M., Reeves D., Sibbald B. Relationships between job satisfaction, intentions to leave family practice and actually leaving among family physicians in England. Eur J Public Health. 2010;21(4):499–503. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckq005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rittenhouse D.R., Mertz E., Keane D., Grumbach K. No exit: an evaluation of measures of physician attrition. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(5):1571–1588. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones C.B. The costs of nurse turnover, part 2: application of the Nursing Turnover Cost Calculation Methodology. J Nurs Admin. 2005;35(1):41–49. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200501000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones C.B. Revisiting nurse turnover costs: adjusting for inflation. J Nurs Admin. 2008;38(1):11–18. doi: 10.1097/01.NNA.0000295636.03216.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fibuch E., Ahmed A. Physician turnover: a costly problem. Physician Leadersh J. 2015;2(3):22–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maurer R. Turnover “tsunami’ expected once pandemic ends. SHRM Better Workplaces Better World. March 12, 2021. https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/hr-topics/talent-acquisition/pages/turnover-tsunami-expected-once-pandemic-ends.aspx

- 34.Shipman S.A., Sinsky C.A. Expanding primary care capacity by reducing waste and improving the efficiency of care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(11):1990–1997. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shanafelt T., Trockel M., Rodriguez A., Logan D. Wellness-centered leadership: equipping health care leaders to cultivate physician well-being and professional fulfillment. Acad Med. 2021;96(5):641–651. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shanafelt T.D., Dyrbye L.N., West C.P. Addressing physician burnout: the way forward. JAMA. 2017;317(9):901–902. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shanafelt T.D., Noseworthy J.H. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129–146. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sinsky C.A., Daugherty Biddison L., Mallick A., et al. National Academy of Medicine; Washington, DC: 2020. Organizational Evidence-Based and Promising Practices for Improving Clinician Well-being. NAM Perspectives Discussion Paper. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sinsky C., Linzer M. Practice and policy reset post-COVID-19: reversion, transition, or transformation? Health Aff (Millwood) 2020;39(8):1405–1411. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greenawald M.A. PeerRxMED. www.peerrxmed.com

- 41.Shapiro J. 2020. Building a Peer Support Program for Physicians.https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2767766?resultClick=1&bypassSolrId=J_2767766 American Medical Association Steps Forward online resources. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Funk K.A., Davis M. Enhancing the role of the nurse in primary care: the RN “co-visit” model. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(12):1871–1873. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3456-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lyon C., English A.F., Chabot Smith P. A team-based care model that improves job satisfaction. Fam Pract Manag. 2018;25(2):6–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Misra-Hebert A.D., Rabovsky A., Yan C., Hu B., Rothberg M.B. A team-based model of primary care delivery and physician-patient interaction. Am J Med. 2015;128(9):1025–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sinsky C.A., Bodenheimer T. Powering-up primary care teams: advanced team care with in-room support. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(4):367–371. doi: 10.1370/afm.2422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith P.C., Lyon C., English A.F., Conry C. Practice transformation under the University of Colorado’s primary care redesign model. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(suppl 1):S24–S32. doi: 10.1370/afm.2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reuben D.B., Knudsen J., Senelick W., Glazier E., Koretz B.K. The effect of a physician partner program on physician efficiency and patient satisfaction. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1190–1193. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.West C.P., Dyrbye L.N., Rabatin J.T., et al. Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):527–533. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ashton M. Getting rid of stupid stuff. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(19):1789–1791. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1809698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Helfrich C.D., Dolan E.D., Simonetti J., et al. Elements of team-based care in a patient-centered medical home are associated with lower burnout among VA primary care employees. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(suppl 2):S659–S666. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2702-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sieja A., Markley K., Pell J., et al. Optimization sprints: improving clinician satisfaction and teamwork by rapidly reducing electronic health record burden. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(5):793–802. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Linzer M., Poplau S., Grossman E., et al. A cluster randomized trial of interventions to improve work conditions and clinician burnout in primary care: results from the Healthy Work Place (HWP) Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(8):1105–1111. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3235-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shanafelt T., Ripp J., Brown M.T., Sinsky C.A. Creating a resilient organization: caring for healthcare workers during crisis. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2779438?resultClick=1&bypassSolrId=J_2779438

- 54.Shanafelt T., Ripp J., Trockel M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2133–2134. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shanafelt T.D., Ripp J.A., Brown M.T., et al. Caring for the Health Care Workforce During Crisis. American Medical Association Steps Forward online resources. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2768609 Published July 23, 2020.

- 56.Rotenstein L, Braunfields D, Sliwka D. Six principles to ensure clinician well-being: lessons from COVID-19’s darkest days for a new way of working. Health Affairs Blog. March 29, 2021. https://www.centerfordigitalhealthinnovation.org/posts/six-principles-to-ensure-clinician-well-being-lessons-from-covid-19s-darkest-days-for-a-new-way-of-working. Accessed April 20, 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.