Abstract

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) restrictions, including national lockdown, social distancing, compulsory quarantine, and organizational measures of remote working, are imposed in many countries and organizations to combat the coronavirus. The various restrictions have caused different impacts on the employees' mental health worldwide. The purpose of this mini-review is to investigate the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on employees' mental health across the world. We searched articles in Web of Science and Google Scholar, selecting literature focusing on employees' mental health conditions under COVID-19 restrictions. The findings reveal that the psychological impacts of teleworking are associated with employees' various perceptions of its pros and cons. The national lockdown, quarantine, and resuming to work can cause mild to severe mental health issues, whereas the capability to practice social distancing is positively related to employees' mental health. Generally, employees in developed countries have experienced the same negative and positive impacts on mental health, whereas, in developing countries, employees have reported a more negative effect of the restrictions. One explanation is that the unevenly distributed mental health resources and assistances in developed and developing countries.

Keywords: COVID-19 restrictions, work-related mental health, employees, developing and developed countries, social distancing, remote working

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised dramatic changes in the working landscape worldwide. The governments and organizations have implemented a series of emergency packages, such as mandatory lockdown, social distancing, and quarantine, to curb the coronavirus from further spreading and emergency measures on physically resuming to work after the lockdown. Besides, a vast majority of employees have also switched immediately to working from home, known as “teleworking,” “remote working,” or “smart working” (1), responding to the directives of their organizations. Working under these restrictions produces unprecedented challenges to employees, among which is to adapt to the abrupt shifts in working conditions quickly. Even though they are, to a large extent, physically protected, concerns about their mental health have sharply arisen in the extant literature (2).

The phenomenon of implementing COVID-19 restrictions is novel to the research disciplines of both organization studies and public health. Notably, as a containment strategy to prevent employees from physical harm, the implementation of COVID-19 restrictions unexpectedly brings up mental health issues on them. For example, some employees are found experiencing higher psychological distress (e.g., a negative dimension of mental health) following the work-from-home (WFH) guidelines of their organizations (3, 4). However, the complex impact of applying COVID-19 restrictions on work-related mental health is largely understudied compared to the vast majority of literature focusing on the impact of the outbreak of COVID-19 (5). Besides, in contrast to the tremendous psychological problems derived from the COVID-19 pandemic (6), the psychological impact of COVID-19 restrictions remains unclear. Extant literature presents mixed findings on the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on mental well-being (7). Even though the COVID-19 restrictions have placed strain on different cohorts (8), we suggest paying more attention to employees—a representative group experienced both national and organizational restrictions during the pandemic. The restriction-induced job insecurity and financial hardship add more challenges and are likely to escalate some psychological symptoms further (9). Consequently, our research is concerned about how the responses of governments and organizations to the COVID-19 pandemic affect employees' mental health.

The purpose of this mini-review is to examine the psychological impact of the various epidemic-related restrictions on employees. To this end, we systematically select the studies regarding employees' mental health under national-level restrictions, such as mandatory lockdown, quarantine, social distancing, resuming to work, and teleworking guidelines of companies or public organizations (e.g., public schools). The various restrictions may lead to different psychological impacts due to their inherent differences. The review identifies the variety of COVID-19 restrictions and the associated psychological impact on employees. In contrast to the primary concentration on healthcare workers or general populations, we argue that employees should be a chief concern as their mental well-being is strongly associated with economic development and labor cost to society (10).

The review contributes to understanding the impact of emergency measures (e.g., COVID-19 restrictions) on work-related mental health. Chiefly, we categorize various COVID-19 restrictions and their psychological impact on employees. In doing so, the review straightforwardly presents the consequences of the various restrictions on the work-related mental health of employees. Additionally, the review documents evidence from diverse countries to track the influence of specific restrictions on employees' mental health and statistically analyses the variations on each epidemic-related restriction's impact in developed and developing countries. The review responds to the call for attention on employees' mental well-being associated with the health emergencies at the workplace during the COVID-19 pandemic (11). More importantly, the review suggests practitioners (e.g., managers, policymakers) fully consider the complexity and consequences of applying COVID-19 restrictions. Timely mental health support is urgently needed to assist employees who have been psychologically struggling under the ongoing implementation of COVID-19 restrictions.

Methods

For a wide-ranging and disciplined collection of the literature on employees' mental health and COVID-19 restrictions, we performed systematic literature searching for the relevant articles. The search scope comprises four factors: time span, keywords, language, and databases. Primarily, we selected articles in the English language, and published between January 2020 and August 2021. The combined terms of “COVID-19 restrictions,” “employees” or “workers,” and “mental health” or “psychological well-being” are used as the keywords searching in the databases “Web of Science” and “Google Scholar.”

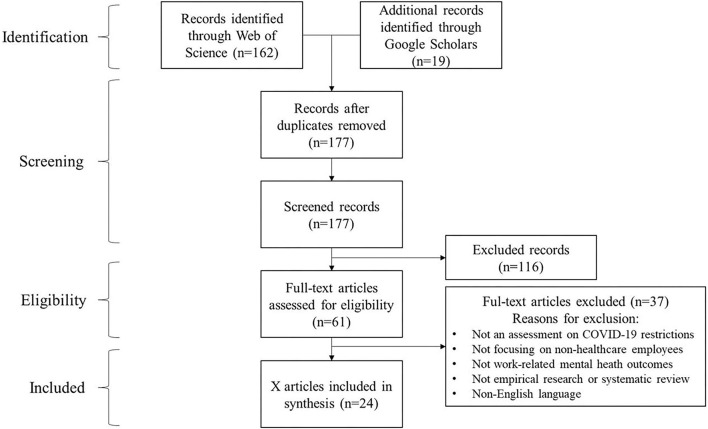

The initial search resulted in the identification of 177 related articles. Article selection was conducted by two authors in an independent manner. The first round of manual screening is based on article title and abstract. We excluded the non-empirical research, narrative literature reviews, and the articles without considering COVID-19 restrictions and employees' mental health. Besides, the research that exclusively focuses on healthcare workers is also excluded. The disputes on the inclusion of each article were jointly discussed and solved with the contribution of all co-authors. The first round of screening resulted in 61 articles. Sequentially, the author proceeds to extensive reading of the introduction and conclusion of these articles. Finally, 37 articles have been excluded from the review because their focuses have no relation to the review topic. In the end, 24 highly relevant research articles have been confirmed. The literature selection strategy was visualized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Literature search strategy, following PRISMA flow diagram (12).

Results

The findings cover four government responses, including national lockdown, resuming to work with approval, social distancing, mandatory quarantine, and a broadly used organization response in many industries—remote working. We separate remote working from other national restrictions for two reasons. Primarily, remote working as an organizational work arrangement has emerged prior to the pandemic (13). Second, remote working does not apply to the general workforce as the other government responses do. For example, grocery retailers, restaurant employees do not apply to the remote working guidelines. It is only workable for certain groups of the workforce who can manage their work flexibly with no restrictions to location.

National-Level Restrictions

COVD-19 restrictions are a series of non-pharmaceutical measures carried out to prevent the spread of the virus. Governments worldwide have declared strict national-level measures to prevent transmission of the coronavirus. The findings reveal that among those country-level health emergencies, mandatory lockdown, quarantine, social distancing, and resuming to work are recognized as highly associated with the psychological impact of employees.

Lockdown

Scholars describe nationwide lockdown as at the forefront of various restrictions, that is, through measures like closing non-essential businesses, limiting public transportation. Lockdown has proven effective in suspending the spread of the coronavirus but at the expense of psychological effects (14).

Both negative and positive psychological impacts of national lockdown are reported in the reviewed studies. Apouey et al. (15) have found that gig economy workers, especially food delivery bikers, are less stressed during the lockdown due to their working conditions, allowing them to keep physical activities and enjoy the beautiful urban view delivering food to customers. In contrast, drivers, also as gig economy workers, show no significant increase in anxiety and stress during the national lockdown in France. Abbas et al. (16) also report reduced stress of employees during the lockdown in Pakistan. Nevertheless, the studies carrying out in developing countries (i.e., Indian) show more negative psychological reactions than positive outcomes. The sudden changes in the routine of working and living lead to employees' psychological stress, social disconnectedness, a sense of loneliness in Indian (17), and depression in Pakistan (18).

The underlying reasons for employees' mental health issues are primarily due to the lockdown-induced fear of job insecurity (16), financial losses (17), and excessive exposure to misinformation while using social media to keep social connections (18). Therefore, scholars suggest several practical interventions, such as social support, timely and sufficient mental health assistance, to mitigate the emerged psychological symptoms during the lockdown period (16, 17).

Resuming to Work

Due to effective control of the pandemic, a growing number of employees in many countries have been physically attending to the workplace. In China, part of the workforce has resumed work after seeking approval from the government since the ending of an extended nationwide lockdown on February 10, 2020 (19). By June 2020, many states in the U.S. also allowed restaurants to reopen and employees resuming work (20). Around the same time in Bangladesh, some financial institutions are permitted to operate with limited hours (21).

Surprisingly, the easing restrictions are more associated with adverse psychological reactions. Employees show psychological symptoms, including psychological distress (3, 21, 22), depression, anxiety, stress, worries, insomnia, somatization (19, 20, 23), and emotional reactions (24). Scholars have found that the fear of contracting the coronavirus is the chief concern of employees, especially those who cannot avoid face-to-face interactions during work (e.g., bank employees, restaurant workers, teachers) (3).

Nevertheless, workplace measures, such as workplace hygiene and indoor mask mandates (19, 22, 23), are important to influence employees' mental health conditions. Scholars report strong evidence that the deficiency of workplace measures is associated with higher stress levels of employees (23), especially for the frontline workforce, including bank employees (21), school teachers (24), and restaurant workers (3). On the contrary, sufficient and clear workplace guidelines can vastly reduce the psychological distress of the workforce (19, 22). Besides, social support is also essential to release employees' worry about unemployment (20). Bufquin et al. (3) report that furloughed or unemployed individuals has experienced a lower level of psychological distress than working employees in the restaurant industry in the U.S. because they received social support (e.g., financial compensation, tax credits) from the federal government.

Employees' mental health conditions show more negative than positive consequences under the easing of restrictions. Studies carried out in developed countries (i.e., USA, Demark, Japan) show two adverse outcomes (2/7 articles) and one positive outcome (1/7 articles); in contrast, studies in developing countries (i.e., China, Bangladesh) show three adverse outcomes (3/7 articles) and one positive outcome (1/7 articles).

Social Distancing

Social distancing is also a national measure to avoid gathering among people during the pandemic. Scholars suggest that social distancing has generated net social benefits of $5.16 trillion to curb coronavirus transmission in the U.S. (25). Scholars also call attention to the psychological effect of implementing social distancing nationwide (26). In a recent study, Lan et al. (27) report that social distancing can ease the depression and anxiety of employees in the grocery retail industry, where the likelihood of close contact with other people is high.

Quarantine

Governments worldwide have imposed various quarantine restrictions for different groups of individuals during the pandemic. For example, individuals with positive COVID-19 tests are isolated in hospitals (28); international travelers are compulsorily quarantined in designated hotels for 14 days after entry to a country (29). Most quarantine-related studies are concerned about the psychological impact on vulnerable groups, including healthcare workers, children and older adults (30). Teng et al. (31) investigate the employees who are working in the designated hotels for quarantine accommodation, finding that that the quarantine hotel employees have experienced mental health burden due to the augmented risk of contact guests suspected to have or infected by COVID-19 and the increased workload of operating a quarantined hotel.

Organizational-Level Restrictions

Apart from the government mandates, teleworking, as a prominent measure initiated by many companies and organizations, also places strain upon employees' mental well-being (32).

Remote Working

Remote working is not a new phenomenon for employees and companies (13). As a working practice for some professionals to voluntary work offsite from the office, remote working initially attempts to provide flexible work-life arrangements (7). Compared to conventional telework, pandemic-induced remote working is mandatory in nature (33), and companies and organizations have never before enforced employees to work full time at home simultaneously in a global range (32). On the one hand, using telecommunication devices to complete work has significantly minimized the risk of spreading the virus through regular close contact with others (4). On the other hand, as a growing phenomenon, employees' psychological reactions to remote working emerge as a fundamental problem (4).

Scholars report psychological symptoms induced by remote working during the pandemic ranging from stress, emotional distress, emotional exhaustion, and anxiety to depression (4, 32, 34). Employees' mental health issues are associated with their perceptions of the pros and cons of telework. The acknowledged advantages of teleworking include saved commuting time, flexible working conditions, and lower risk of COVID-19 infection, whereas the dark sides are technical issues, blurred work-life boundaries, distractions, and social disconnection (7, 35). In contrast to the general employees, some groups of employees are more easily to develop negative perceptions than positive ones, such as autistic employees (35), teachers, and university employees (7, 36), due to the challenges of adaptation to teleworking.

On top of that, the strict management control and monitor (32), deteriorated work engagement (37), and excessive job demand (34) can aggravate employees' mental health psychological symptoms during remote working. Also, employees in developed countries (i.e., Italy, Finland, Germany, U.S., Canada, Norway, U.K., and Australia) report similar positive (4/11 articles) and negative (3/11 articles) psychological impacts. In contrast, those in developing countries (i.e., Israel, Egypt, Indonesia, Chile) show more negative (3/11 articles) psychological impacts of remote working.

A more specific description of these included articles is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of included articles.

| Level of COVID-19 restrictions | COVID-19 restrictions | Work-related mental health | Country | Factors considered | Main results | Methods | Population setting/N (if available) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational level | Remote working | Emotional distress | Israel | Perceived advantage/ disadvantage of telework | Autistic employees show a marginally significant deterioration in their mental health because they are more vulnerable to the disadvantages of remote working than the advantages | Mixed methods (survey and qualitative interview) | Autistic employees (disadvantaged population in the workforce)/N = 23 (quant), N = 10 (qual) |

Goldfarb et al. (35) |

| Occupational stress | Italy | Perceived advantage/ disadvantage of telework | The mobile workers show reduced stress due to saved commuting time, flexibility, and work-life balance in teleworking | Cross sectional/phone survey | Mobile workers/N = 51 | Moretti et al. (1) | ||

| stress | Italy | Management control | Remote working causes a sudden shift of management controls, including the increased number of digital meetings, more demanding from supervisors and clients, and constraining control, which increases the stress levels of the PSF employees | Field study/interview | PSF employees/N = 15 | Delfino and van der Kolk (32) | ||

| Perceived stress | Italy | Perceived advantage/ disadvantage of telework | Teachers are affected most in their mental health comparing the other three professional categories due to the less perceived benefits of teleworking | Cross sectional/online survey | Professional employees (practitioners, managers, executive employees, teachers)/N = 628 | Mari et al. (38) | ||

| Emotional exhaustion, psychological well-being | Egypt | Perceived advantage/ disadvantage of telework | Employees developing positive perceptions of remote working have better psychological well-being. In contrast, employees who have negative perceptions of telework show emotional exhaustion | Cross sectional/online survey | Employees/N = 318 | Mostafa (7) | ||

| The Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale | Indonesia | Reduced pandemic-related uncertainty | Employees show minimal to slight acute depression (18.4%), anxiety (46.5%), and stress (13.1%) during remote working | Cross sectional/online survey | Employees/N = 472 | Sutarto et al. (4) | ||

| Psychological distress | Finland | Work engagement | Remote working leads to an increase of psychological distress due to the deterioration in work engagement | Longitudinal/online survey | General employees/N = 965 | Oksa et al. (37) | ||

| Emotional exhaustion | Germany and USA | Excessive job demand | Excessive job demands in telework lead to employees' emotional exhaustion through the increased number of unfinished tasks | Online survey | Employees in Germany/N = 168 | Koch and Schermuly (34) | ||

| Employee in the USA/N = 292 | ||||||||

| Stress | Canada | Perceived advantage/ disadvantage of telework | Employees' stress level is lower due to the reduced risk of exposure to the virus in teleworking | Cross sectional/online survey | General employees/N = 459 | Parent-Lamarche and Boulet (39) | ||

| Distress, psychosocial well-being, quality of life, loneliness | Norway, UK, USA, and Australia | Perceived advantage/ disadvantage of telework | The remote working employees show better mental health conditions than those who were unemployed across the four countries. Employees from Norway show better mental health conditions than those in UK, USA, and Australia due to their preference for teleworking | Cross sectional/online survey | Individuals that were 18 years of age and over/N = 3,810 | Ruffolo et al. (40) | ||

| Psychological distress (i.e., depression, anxiety, stress) | Chile | Perceived advantage/ disadvantage of telework | A majority of university employees have experienced a high level of stress due to the challenges of adaptation to remote working | Cross sectional/online survey | University employees/N = 192 | Gutierrez and Gallardo (36) | ||

| National level | Lockdown | Stress and anxiety | France | Perceived advantage/ disadvantage of the lockdown | Drivers show no significant increase in stress and anxiety levels, and bikers even show lower stress levels during the lockdown compared to other precarious workers. Bikers' lower stress is due to the characteristics of their working conditions, such as physical activities and the chance to enjoy the beauty of the urban view | Mixed method (interviews and longitudinal/online survey) | Gig economy workers (i.e., bikers and drivers) /(qualitative respondents/N = 94; quantitative participants/N = 137) | Apouey et al. (15) |

| Psychological well-being, psychological distress | USA | Social support | Working employees have a higher level of psychological distress than furloughed or laid-off employees due to the heightened likelihood of exposure to the virus. | Cross sectional/online survey | Restaurant employees/N = 585 | Bufquin et al. (3) | ||

| Unemployed individuals show no significant difference in psychological well-being than employed due to the government's social support | ||||||||

| 6-item general health questionnaire | Pakistan | Social support | Job insecurity is adverse to employees' mental health when social support is low | Time-lagged field survey | Hospitality employees/N = 272 | Abbas et al. (16) | ||

| Psychological stress, social disconnectedness, and sense of loneliness | Indian | Mental health assistance | The majority of the respondents have experienced desolation and disconnectedness during the lockdown due to financial losses and blurred work-life boundaries | Qualitative interview | Middle-level employees in private sector organizations/N = 22 | Varshney (17) | ||

| Depression | Pakistan | Social media usage | The excessive social media usage during social distancing of the pandemic lead to employee depression due to overexposure to misinformation | Longitudinal/online survey | University employees and IT employees/N = 267 | Majeed et al. (18) | ||

| Returning to working physically at workplace after lockdown | Psychological distress | Bangladesh | Workplace measures, social support |

A majority of bank employees are likely to experience a moderate to severe level of psychological distress due to the lack of personal protective equipment when they were returning to work after a national lockdown | Cross sectional/online survey | Private commercial bank employees/N = 120 | Rana and Islam (21) | |

| Depression, anxiety, stress, and insomnia | China | Workplace measures | Employees report a low prevalence of mental health issues after returning to work due to workplace measures | Cross sectional/online survey | Employees/N = 1,323 | Tan et al. (19) | ||

| Anxiety, depression, insomnia, and somatization | China | social support, mental health assistance | Employees show a prevalence of anxiety (12.7%), depression (13.5%), insomnia (20.7%) and somatization (6.6%) after returning to work due to the worry about unemployment | Cross sectional/online survey | Employees/N = 709 | Song et al. (20) | ||

| Emotional reactions | Demark | Perceived advantage/ disadvantage of telework | Remote-working teachers show higher levels of worry than those teaching at school when they return to teaching physically at school | Cross sectional/online survey | Public school teachers/N = 2,665 | Nabe-Nielsen et al. (24) | ||

| Psychological distress | Japan | Workplace measures | The number of workplace measures is positively associated with employees' work-related mental health | Cross sectional/online survey | Full-time employees/N = 1,448 | Sasaki et al. (22) | ||

| Stress and worries | Hong Kong, China | Workplace measures | The deficiency of workplace measures has caused an increase in employees' stress levels | Cross sectional/online survey | Employees/N = 1,049 | Ho et al. (23) | ||

| Social distancing | Depression and anxiety | USA | Workplace measures, mental health assistance | Grocery retail employees who can practice social distancing at the workplace have experienced low anxiety and depression | Cross sectional/on site survey | Grocery retail employees/N = 104 | Lan et al. (27) | |

| Quarantine | The Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale | China | Workplace measures, mental health assistance | During the pandemic, the temporary quarantine accommodation restrictions harmed the mental health of quarantine hotel employees in China due to the augmented risk of contact guests suspected to have or infected by COVID-19 and the raised workload of operating a quarantined hotel | Survey | Quarantine hotel employees/N = 170 | Teng et al. (31) |

Discussion

The review aimed to address the influence of the implementation of COVID-19 restrictions on employees' mental health. The results show that COVID-19 restrictions can have both negative and positive psychological impacts on employees. The underlying reason for the increased psychological well-being of employees is primarily associated with the minimized fear of contracting the virus. In contrast, the mild to severe psychological symptoms induced by implementing these restrictions arise due to multiple reasons ranging from individual, practical, to social factors.

First, some employees are found more likely to experience deteriorated mental health than others during the restrictions. For example, autistic employees are more vulnerable to the disadvantages of remote working than its advantages (35). Similarly, some frontline workers (except healthcare workers in this review) such as quarantine hotel employees, bank employees, teachers, and university employees show psychological symptoms resuming to work due to the challenges of increased risks of contracting the virus (21, 24, 31). In contrast, gig economy workers, especially food delivery bikers, have lower stress during the lockdown due to the chance to do physical activities and enjoy the beautiful urban view while working (15). These findings suggest that the psychological reactions of vulnerable employees and frontline employees are more intense than others.

Second, this mini-review highlights several practical factors, including workplace measures and management practices, essential to mental health under COVID-19 restrictions. For example, deficiency of workplace measures undermines employees' mental health, leading to psychological symptoms such as stress and worries (23), depression, anxiety, stress, and insomnia (19). In contrast, clear and comprehensive workplace guidelines can reduce employees' psychological distress (22). Similarly, strict management control and excessive job demand during teleworking can lead to emotional exhaustion (34) and stress (32). Also, reduced work engagement during teleworking can cause employees' psychological distress (37).

Besides, in line with other studies (11), this mini-review also presents the importance of social factors in mitigating or exacerbating employees' psychological reactions under implementing COVID-19 restrictions. In this regard, social support, such as financial support programs, can prevent symptoms of psychological distress, especially for furloughed or dismissed employees during the pandemic (3). Similarly, psychological support programs, such as online mental health assistance or counseling, are helpful to alleviate the psychological issues of employees. The review suggests that sufficient social support, both financially and psychologically, plays an essential role in safeguarding employees' mental health during implementing COVID-19 restrictions.

Additionally, the studies reviewed consistently report more adverse impacts on employees' mental health than positive effects. Consistent with Flores et al. (41), our mini-review suggests that regardless of the success of cubing the spread of COVID-19, public health restrictions must be coupled with the efforts to shape proper interventions managing its psychological impacts on employees. The adverse outcomes are evident when it comes to compare and contrast with the data sourced countries. In 24 reviewed articles, studies conducted in developed countries report six negative and positive impacts, respectively, in contrast to 10 adverse outcomes of the research in developing countries. One plausible explanation is the lack of online mental health care resources in developing countries (42).

Conclusion

Despite the recent growth of this field, attention to the psychological impacts of COVID-19 restrictions remains low in contrast to the primary concentration on the effect of the pandemic per se. Most studies are mainly concerned about the general population rather than employees (11), and research exhibiting employees' psychological reactions toward various COVID-19 restrictions is still limited. Based on the available 24 articles focusing on several pandemic restrictions, namely, national lockdown, resuming to work, social distancing, quarantine, and remote working, our mini-review reveals more adverse psychological impacts than positive ones on employees, especially in developing countries. We suggest that proper interventions must be arranged to safeguard employees' mental health.

Author Contributions

WL, YX, and DM wrote the initial drafts, reviewed the manuscript, and provided comments and feedback. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1.Moretti A, Menna F, Aulicino M, Paoletta M, Liguori S, Iolascon G. Characterization of home working population during COVID-19 emergency: a cross-sectional analysis. Int J Env Res Pub Health. (2020) 17:6284. 10.3390/ijerph17176284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamouche S. COVID-19, Physical distancing in the workplace and employees' mental health: implications and insights for organizational interventions-narrative review. Psychiat Danub. (2021) 33:202–8. 10.24869/psyd.2021.202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bufquin D, Park JY, Back RM, de Souza Meira JV, Hight SK. Employee work status, mental health, substance use, and career turnover intentions: an examination of restaurant employees during COVID-19. Int J Hosp Manag. (2021) 93:102764. 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sutarto AP, Wardaningsih S, Putri WH. Work from home: Indonesian employees' mental well-being and productivity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Workplace Health Manag. (2021) 14:386–408. 10.1108/IJWHM-08-2020-0152 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giorgi G, Lecca LI, Alessio F, Finstad GL, Bondanini G, Lulli LG, et al. COVID-19-related mental health effects in the workplace: a narrative review. Int J Env Res Pub Health. (2020) 17:7857. 10.3390/ijerph17217857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torales J, O'Higgins M, Castaldelli-Maia JM, Ventriglio A. The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. Int J Soc Psychiatr. (2020) 66:317–20. 10.1177/0020764020915212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mostafa BA. The effect of remote working on employees wellbeing and work-life integration during pandemic in Egypt. Int Bus Res. (2021) 14:41–52. 10.5539/ibr.v14n3p41 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan KS, Mamun MA, Griffiths MD, Ullah I. The mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic across different cohorts. Int J Ment Health Ad. (2020) 2020:1–7. 10.1007/s11469-020-00367-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson JM, Lee J, Fitzgerald HN, Oosterhoff B, Sevi B, Shook NJ. Job insecurity and financial concern during the COVID-19 pandemic are associated with worse mental health. J Occup Environ Med. (2020) 62:686–91. 10.1097/jom.0000000000001962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson A, Dey S, Nguyen H, Groth M, Joyce S, Tan L, et al. review and agenda for examining how technology-driven changes at work will impact workplace mental health and employee well-being. Aust J Manage. (2020) 45:402–24. 10.1177/0312896220922292 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phugat N, Chitranshi J. The effect of COVID-19 over employees' mental health—a review. J Pharm Res Int. (2021) 33:104–10. 10.9734/jpri/2021/v33i37B32027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. PRISMA group preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. (2009) 6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martínez-Sánchez A, Pérez-Pérez M, De-Luis-Carnicer P, Vela-Jiménez MJ. Telework, human resource flexibility and firm performance. New Tech Work Employment. (2007) 22:208–23. 10.1111/j.1468-005X.2007.00195.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atalan A. Is the lockdown important to prevent the COVID-19 pandemic? Effects on psychology, environment and economy-perspective. Ann Med Surg. (2020) 56:38–42. 10.1016/j.amsu.2020.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Apouey B, Roulet A, Solal I, Stabile M. Gig workers during the COVID-19 crisis in France: financial precarity and mental well-being. J Urban Health. (2020) 97:776–95. 10.1007/s11524-020-00480-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abbas M, Malik M, Sarwat N. Consequences of job insecurity for hospitality workers amid COVID-19 pandemic: does social support help?. J Hosp Market Manag. (2021) 2021:1–25. 10.1080/19368623.2021.1926036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Varshney D. How about the psychological pandemic? Perceptions of COVID-19 and work–life of private sector employees—a qualitative study. Psychol Stud. (2021) 66:337–46. 10.1007/s12646-021-00605-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Majeed M, Irshad M, Fatima T, Khan J, Hassan MM. Relationship between problematic social media usage and employee depression: a moderated mediation model of mindfulness and fear of COVID-19. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:3368. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.557987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tan W, Hao F, McIntyre RS, Jiang L, Jiang X, Zhang L, et al. Is returning to work during the COVID-19 pandemic stressful? A study on immediate mental health status and psychoneuroimmunity prevention measures of Chinese workforce. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 87:84–92. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song L, Wang Y, Li Z, Yang Y, Li H. Mental health and work attitudes among people resuming work during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study in China. Int J Env Res Pub Health. (2020) 17:5059. 10.3390/ijerph17145059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rana RH, Islam A. Psychological impact of COVID-19 among frontline financial services workers in Bangladesh. J Workplace Behav Health. (2021) 2021:1–12. 10.1080/15555240.2021.1930021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sasaki N, Kuroda R, Tsuno K, Kawakami N. Workplace responses to COVID-19 associated with mental health and work performance of employees in Japan. J Occup Health. (2020) 62:1–6. 10.1002/1348-9585.12134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ho KFW, Ho KF, Wong SY, Cheung AW, Yeoh E. Workplace safety and coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic: survey of employees. Bull World Health Organ. [Preprint]. (2020). 10.2471/BLT.20.255893 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nabe-Nielsen K, Fuglsang NV, Larsen I, Nilsson CJ. COVID-19 Risk management and emotional reactions to COVID-19 among school teachers in Denmark: results from the CLASS study. J Occup Environ Med. (2021) 63:357–62. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thunström L, Newbold SC, Finnoff D, Ashworth M, Shogren JF. The benefits and costs of using social distancing to flatten the curve for COVID-19. J Benefit-Cost Anal. (2020) 11:179–95. 10.1017/bca.2020.1230886898 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Venkatesh A. Edirappuli S. Social distancing in covid-19: what are the mental health implications? BMJ-Brit Med J. (2020) 369:m1379. 10.1136/bmj.m1379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lan FY, Suharlim C, Kales SN, Yang J. Association between SARS-CoV-2 infection, exposure risk and mental health among a cohort of essential retail workers in the USA. Occup Environ Med. (2021) 78:237–43. 10.1136/oemed-2020-106774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu S, Wu Y, Zhu CY, Hong WC Yu ZX, Chen ZK, Chen ZL, et al. The immediate mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic among people with or without quarantine managements. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 87:56–8. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goh E, Baum T. Job perceptions of Generation Z hotel employees towards working in Covid-19 quarantine hotels: the role of meaningful work. Int J Contemp Hosp Manage. (2021) 33:1688–710. 10.1108/IJCHM-11-2020-1295 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, Shi L, Que J, Lu Q, Liu L, Lu Z, et al. The impact of quarantine on mental health status among general population in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mol Psychiatr. (2021) 2021:1–19. 10.1038/s41380-021-01019-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teng YM, Wu KS, Xu D. The association between fear of Coronavirus Disease 2019, mental health, and turnover intention among quarantine hotel employees in China. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:668774. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.668774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delfino GF, van der Kolk B. Remote working, management control changes and employee responses during the COVID-19 crisis. Account Audit Accoun. (2021) 34:1376–87. 10.1108/AAAJ-06-2020-4657 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carillo K, Cachat-Rosset G, Marsan J, Saba T, Klarsfeld A. Adjusting to epidemic-induced telework: empirical insights from teleworkers in France. Eur J Inform Syst. (2021) 30:69–88. 10.1080/0960085X.2020.1829512 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koch J, Schermuly CC. Managing the crisis: how COVID-19 demands interact with agile project management in predicting employee exhaustion. Brit J Manage. (2021) 2021:1–19. 10.1111/1467-8551.12536 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldfarb Y, Gal E, Golan O. Implications of employment changes caused by COVID-19 on mental health and work-related psychological need satisfaction of autistic employees: a mixed-methods longitudinal study. J Autism Dev Disord. (in press). 10.1007/s10803-021-04902-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gutierrez RJ. Gallardo FH. Mental health in officials of a Chilean university: challenges in the context of COVID-19. Rev Dig Investig Doc Univ-Ridu. (2020) 14:e1310. 10.19083/ridu.2020.1310 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oksa R, Kaakinen M, Savela N, Hakanen JJ, Oksanen A. Professional social media usage and work engagement among professionals in Finland before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: four-wave follow-up study. J Med Internet Res. (2021) 23:e29036. 10.2196/29036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mari E, Lausi G, Fraschetti A, Pizzo A, Baldi M, Quaglieri A, et al. Teaching during the pandemic: a comparison in psychological wellbeing among smart working professions. Sustainability-Basel. (2021) 13:4850. 10.3390/su13094850 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parent-Lamarche A, Boulet M. Workers' stress during the first lockdown: consequences on job performance analyzed with a mediation model. J Occup Environ Med. (2021) 63:469–75. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruffolo M, Price D, Schoultz M, Leung J, Bonsaksen T, Thygesen H, et al. Employment uncertainty and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic initial social distancing implementation: a cross-national study. Global Soc Welf. (2021) 8:141–50. 10.1007/s40609-020-00201-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Flores M, Murchland A, Espinosa-Tamez P, Jaen J, Brochier M, Bautista-Arredondo S, Lamadrid-Figueroa H, Lajous M, Koenen K. Prevalence and correlates of mental health outcomes during the SARS-Cov-2 epidemic in Mexico City and their association with non-adherence to stay-at-home directives, June 2020. Int J Public Health. (2021) 66:620825. 10.3389/ijph.2021.620825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rojas G, Martínez V, Martínez P, Franco P, Jiménez-Molina Á. Improving mental health care in developing countries through digital technologies: a mini narrative review of the Chilean case. Front Public Health. (2019) 7:391. 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]