Abstract

FLT3 internal tandem duplication (FLT3-ITD) is a frequent mutation in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and remains a strong prognostic factor due to high rate of disease recurrence. Several FLT3-targeted agents have been developed, but determinants of variable responses to these agents remain understudied. Here, we investigated the role FLT3-ITD allelic ratio (ITD-AR), ITD length, and associated gene expression signatures on FLT3 inhibitor response in adult AML. We performed fragment analysis, ex vivo drug testing, and next generation sequencing (RNA, exome) to 119 samples from 87 AML patients and 13 healthy bone marrow controls. We found that ex vivo response to FLT3 inhibitors is significantly associated with ITD-AR, but not with ITD length. Interestingly, we found that the HLF gene is overexpressed in FLT3-ITD+ AML and associated with ITD-AR. The retrospective analysis of AML patients treated with FLT3 inhibitor sorafenib showed that patients with high HLF expression and ITD-AR had better clinical response to therapy compared to those with low ITD-AR and HLF expression. Thus, our findings suggest that FLT3 ITD-AR together with increased HLF expression play a role in variable FLT3 inhibitor responses observed in FLT3-ITD+ AML patients.

Subject terms: Cancer, Drug discovery, Molecular biology, Molecular medicine

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 internal tandem duplication (FLT3-ITD) represents a large and heterogeneous group of patients associated with unfavorable prognosis1–4. The recently approved type 1 FLT3 inhibitors have led to improved survival of FLT3-ITD+ AML patients over standard chemotherapy, however, initial responses are often variable and long-term benefits with either monotherapy or combination therapy are rarely achieved5–8. Hence, further studies are needed for identifying molecular biomarkers associated with variable FLT3 inhibitor responses. The aim of this study was to assess whether (i) FLT3-ITD allelic ratio (AR) and ITD mutation length and/or (ii) transcriptomic features, are associated with ex vivo and clinical responses to FLT3 inhibitors in adult AML. To address this topic and build upon our previously published work on FLT3-ITD+ AML patients carrying a co-operative NUP98-NSD1 gene fusion9, we performed a systematic analysis by integrating ex vivo drug sensitivity and resistance testing (DSRT) with FLT3 mutation fragment analysis, and next-generation sequencing (exome and RNA). These analyses were carried out using 119 samples from 87 adult AML patients (Table 1) and 13 healthy donors as specified in the Supplementary file.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Total | FLT3-WT | FLT3-ITD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total, no. (%) | 87 | 49 (56) | 38 (44) |

| Type AML, no. (%) | |||

| De novo | 67 | 37 (55) | 30 (45) |

| Secondary | 20 | 12 (60) | 8 (40) |

| Median age at dg (years) | 62.7 | 64.2 | 58.7 |

| Gender, no. (%) | |||

| Male | 40 | 22 (55) | 18 (45) |

| Female | 47 | 27 (57) | 20 (43) |

| Samples, no. (%) | 119 | 68 (57) | 51 (43) |

| Diagnostic | 57 | 35 (61) | 22 (39) |

| Rel./Ref | 62 | 33 (53) | 29 (47) |

| Median BM blast (%) | 60 | 57.5 | 60 |

We initially characterized ITD-AR (mutant/total FLT3) and ITD lengths from 119 gDNA samples collected from 38 FLT3-ITD+ patients and 49 FLT3-ITD- controls. The analysis identified ITD-AR and ITD lengths from all 38 FLT3-ITD+ patients including 22 samples collected at diagnosis (43%) and 29 at relapsed/refractory (R/R) stage (57%). Altogether 29 unique gain-of-function ITD mutations were found ranging from 17 to 213 bp in length (median 45 bp) with the most frequent size being 21 bp. Five patients (13%) carried two distinct ITD mutations and one had bi-allelic ITD (ITD-AR 1.0). In seven patients ITD mutations either appeared or disappeared during disease progression indicating changes in clonal dominance. In the FLT3-ITD+ cohort, ITD-AR varied between 0.016 and 1.0 (median, 0.338; 95% CI 0.27–0.41) (Supplemental Table 1). Interestingly, 36% of the diagnostic samples (8/22) had high ITD-AR (> 0.338). We found no correlation between ITD-AR and ITD length, however, weak positive correlation existed between ITD-AR and BM blast percentage (Fig. S1). Both ITD-AR and ITD length showed similar frequencies across males and females as well as between AML patients below or above 65 years of age, respectively (Fig. S2). The R/R AML patients (n = 29) had significantly higher ITD-AR (P = 0.024; median: 0.39; 95% CI 0.302–0.478) compared to unmatched diagnostic samples (n = 22) (median: 0.27; 95% CI 0.164–0.369), which indicates that cellular addiction on activated FLT3-signaling increases during disease progression.

We next assessed the impact of ITD-AR and ITD length on leukocyte and BM blast counts, which are frequently increased in FLT3-ITD+ AML10. In samples divided based on median ITD-AR, the ITD-ARhigh (> 0.338) group had significantly higher blast counts compared to the ITD-ARlow (< 0.338) group (Fig. S2). The ITD length on the contrary impacted both variables. Blast counts were significantly higher in the ITDlong (≥ 45 bp) group compared to the ITDshort (< 45 bp) group (P = 0.0431), while the ITDlong patients also showed elevated blood leukocyte counts (P = 0.0284) compared to ITDshort patients (< 45 bp). No significant difference in overall survival (OS) existed between de novo FLT3-ITD+ patients with either long or short ITD. The survival analysis included both diagnostic and R/R samples, considering that ITD lengths remain unchanged for the majority of patients with FLT3-ITD persistence at disease progression8. Importantly, we found significant difference in OS (P = 0.024) between de novo AML patients having either low or high ITD-AR at diagnosis. The 3-year OS rate was only 17% in ITD-ARhigh compared to 67% in the ITD-ARlow group (Fig. S3). In conclusion, these analyses provide evidence that R/R FLT3-ITD+ samples frequently have higher ITD-AR and blast counts compared to diagnostic samples, whereas patients with long ITD mutations have higher leukocyte counts compared to patients with short ITD (< 45 bp) regardless of disease stage.

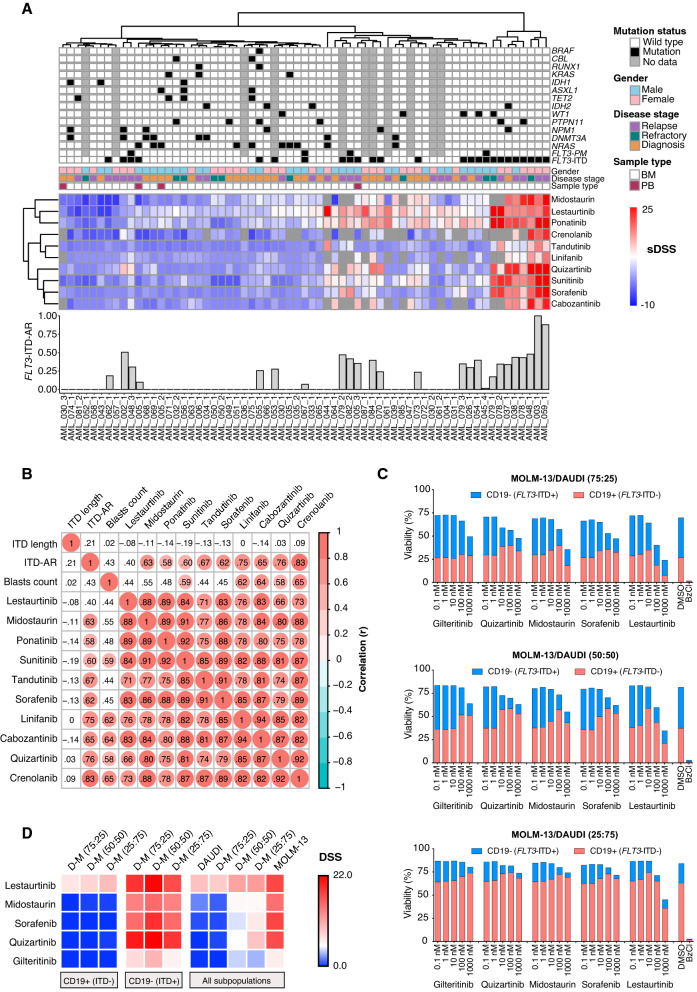

After the initial characterization, we performed ex vivo drug response analysis of BM mononuclear cells from 65 patients (25 FLT3-ITD+ and 40 FLT3-ITD-) using a DSRT-assay9,11. To perform a systematic comparison of FLT3 inhibitors, ten different FLT3 inhibitors with a wide range of selectivity towards FLT3 were included in the analysis (Supplemental Table 2). Cancer cell specific drug responses were quantified as selective drug sensitivity scores (sDSS) (DSS represents a modified area under the curve) for each inhibitor by comparing drug responses of the patients to 13 healthy controls using methods described in the Supplementary information. As expected, all FLT3 inhibitors had significantly higher sDSS showing greater efficacy in FLT3-ITD+ compared to FLT3-ITD- samples. Interestingly, we also found that FLT3 inhibitor sensitivity was higher in the ITD-ARhigh samples compared to the ITD-ARlow samples. Moreover, each FLT3 inhibitor had higher median sDSS in FLT3-ITD+ R/R samples compared to unmatched diagnostic FLT3-ITD+ samples (Fig. 1A, Supplemental Table 3, Fig. S4). The more prominent FLT3 inhibitor responses observed in the ITD-ARhigh subgroup, consisting mostly of R/R samples, indicates clonal dominance of FLT3-ITD+ cells increase during disease progression.

Figure 1.

FLT3-ITD allelic ratio impacts FLT3 inhibitor responses in AML. (A) The top panel shows the presence (black) or absence (white) of recurrent somatic mutations in AML detected by exome sequencing. The FLT3-ITD mutations were detected using fragment analysis. The middle panel shows gender, disease stage, and sample type for the tested samples. The heatmap shows clustering of FLT3 inhibitor responses (sDSS) in AML samples with (N = 25) and without (N = 40) FLT3-ITD compared to healthy controls (N = 13). Blue color indicates resistance and red indicates sensitivity compared to healthy controls. The hierarchical clustering of samples and sDSS was performed using Euclidean distance matrix and complete clustering method. The bar plot below the heatmap shows FLT3-ITD-AR (mutant/total FLT3) in the FLT3-ITD+ samples. (B) The matrix shows correlation between FLT3 inhibitor response, ITD-AR, ITD length, and blast count in 25 FLT3-ITD+ AML samples. The analysis was performed by Pearson correlation. Red circles indicate significant (P < 0.05) correlation with the depth of the color referring to the correlation coefficients. The results show that ITD-AR has the highest correlation with the most specific FLT3 inhibitors (quizartinib and crenolanib), whereas ITD length lacks correlation with FLT3 inhibitor response. (C) Stacked bar-plot representation of viable (Annexin V-) cell counts after 72 h treatment of three different mixtures of FLT3-ITD+ (MOLM-13) and FLT3-ITD- (DAUDI) cell lines with five FLT3 inhibitors as measured by flow cytometry. Each bar shows a percentage of live CD19- (MOLM-13) and CD19 + (DAUDI) cells compared to total number of acquired singlet cells (100%). The percentages were calculated from two repeated measurements. (D) The heatmap displays DSS of five FLT3 inhibitors in CD19 + (FLT3-ITD-), CD19- (FLT3-ITD+), and all viable cells of DAUDI and MOLM-13 cell lines or their co-cultures after the 72 h drug treatment. The DSS was calculated for the inhibitors from modified area under a five-point dose–response curve using % inhibition values at each concentration as described in the online Supplementary file. All experiments were performed in duplicates.

To study whether the observed drug responses are associated with ITD-AR, ITD length, or blast count, we correlated the variables with each FLT3 inhibitor responses (Fig. 1B). As shown in Figs. S5–S7, we found strong positive correlation with ITD-AR and nine FLT3 inhibitors, moderate correlation with blast count and five FLT3 inhibitors, and no correlation between ITD length and FLT3 inhibitor response. The highest correlation with ITD-AR occurred with crenolanib and quizartinib. To examine whether FLT3-ITD allelic burden is directly associated with ex vivo FLT3 inhibitor responses, we performed orthogonal drug testing of FLT3-ITD+ (MOLM-13) and FLT3-ITD- (Daudi) cell lines and their mixtures in varying proportions using a high-throughput flow cytometry-based DSRT-assay with five FLT3 inhibitors. By measuring relative viabilities of CD19 + (Daudi) and CD19- (MOLM-13) cells and their mixtures after 72 h treatment with five FLT3 inhibitors, we generated experimental evidence showing that increasing ITD-AR leads to stronger response to all five FLT3 inhibitors. Moreover, high sensitivity for specific FLT3 inhibitors guides the selection of highly specific or non-specific FLT3 inhibitors (e.g. gilteritinib and midostaurin) based on the FLT3-ITD-AR (Fig. 1C, Fig. S8). In the assay, dose-dependent viability reductions upon FLT3 inhibitor treatment were mainly observed in FLT3-ITD+ cells (CD19-), whereas the relative percentage of viable FLT3-ITD- cells (CD19 +) remained unchanged or increased at higher drug concentrations. The strongest responses were observed for FLT3-ITD heterozygous MOLM-13 cells, whereas FLT3-ITD- Daudi cells showed no response to FLT3 inhibitors other than non-selective multikinase inhibitor lestaurtinib, which showed off-target efficacy in FLT3-ITD- cells (Fig. 1D, Supplemental Table 4). Taken together, our results from two complementary drug testing methods suggest that ITD-AR predicts ex vivo FLT3 inhibitor responses better than blast count or ITD length. The findings are consistent with the Cucchi et al. study reporting that gilteritinib significantly reduces colony-forming capacity of high compared to low ITD-AR or wild type FLT3 AML samples12. Regardless of these findings, we acknowledge that ITD-AR alone cannot solely explain all variation in FLT3 inhibitor response. Few patients within the FLT3-ITD+ cohort lacked response to FLT3 inhibitors regardless of high ITD-AR (Fig. 1A). In our earlier work, we observed that in vitro drug responses of FLT3-ITD transduced BM cells from Balb/C mice are drastically different compared to the same cells co-transduced with FLT3-ITD and NUP98-NSD1 gene fusion9, highlighting that co-occurring mutations also impact FLT3 inhibitor response.

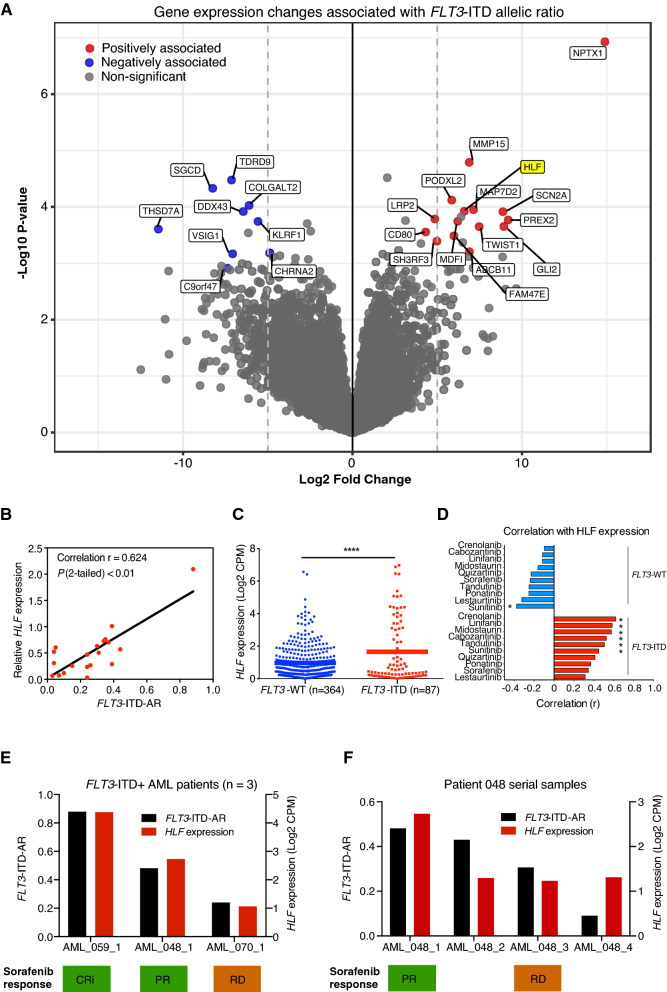

To identify additional factors associated with ITD-AR and FLT3 inhibitor response, we next analyzed RNA-Seq gene expression data from 31 FLT3-ITD+ samples using methods described in the supplemental data and previously13. Linear regression analysis revealed 24 genes significantly associated with ITD-AR (FDR < 0.1 and log2 fold change > ± 4). Positive association with ITD-AR was found for 15 genes and negative association for nine genes (Fig. 2A, Supplemental Table 5). To further support these findings, quantitative-PCR validation was performed on four of the associated genes, namely HLF, KLRP1, MDFIC, and NPTX1, using total RNA from 20 FLT3-ITD+ AML patients. The analysis confirmed significant association between Hepatic Leukemia Factor (HLF) and ITD-AR (r = 0.624, P < 0.01) (Fig. 2B), while no association with the other genes was observed (Supplemental Tables 6–7). As the validation cohort was unbalanced (14 diagnostic, 6 R/R), the same analysis was repeated for diagnostic samples only and showed comparable results. ITD-AR associated with HLF expression (r = 0.667, 95% CI 0.195–0.888, P = 0.011), but not with KLRP1, MDFIC, or NPTX1 (Supplemental Table 7). We next compared HLF expression between FLT3-ITD+ (n = 87) and FLT3 WT (n = 364) AML samples from the BeatAML dataset and found significantly (P < 0.0001) higher expression in the FLT3-ITD+ samples (Fig. 2C)14. HLF encodes a transcription factor that modulates fate of the hematopoietic lineage and was recently shown to regulate leukemic stem cells in triple-mutant AML with FLT3-ITD+, NPM1, and DNMT3A15,16. However, as our cohort included only one patient with the triple-mutant genotype, we could not study the exact mechanism of HLF mediated leukemic stem cell regulation in this subgroup of AML. The FLT3-ITD+ samples included in the gene expression analysis showed significant association between HLF expression and ex vivo response to crenolanib, midostaurin, sunitinib, tandutinib, cabozantinib, and linifanib, while FLT3 WT samples showed no correlation (Fig. 2D, Supplemental Table 8). This finding suggests that ITD-AR together with associated HLF expression can predict ex vivo FLT3 inhibitor responses better compared to ITD-AR or HLF alone.

Figure 2.

Gene expression profiles associated with FLT3-ITD-AR and FLT3 inhibitor response. (A) The volcano plot depicts protein coding genes (N = 14 141) with positive (red) or negative (blue) association with the ITD-AR identified by linear regression analysis of FLT3-ITD+ samples (N = 31). The genes with FDR < 0.1 and log2 fold change > 5 were considered significant. (B) qPCR validation experiment with 20 FLT3-ITD+ RNA samples confirmed association of HLF with ITD-AR. The figure shows correlation analysis of relative HLF quantity and ITD-AR levels. The HLF expression was normalized against four reference genes (EIF4B, RPL19, SH3D19, and NACA) with uniform expression across samples. (C) Expression of HLF was compared between FLT3-ITD+ and FLT3-WT patients using the BeatAML dataset. (D) The waterfall plot shows Pearson correlation coefficients between HLF gene expression (Log2 CPM) and selective FLT3 inhibitor responses in FLT3-WT and FLT3-ITD+ samples. Response to six inhibitors were associated (P < 0.05) with HLF expression. Significant associations are denoted with an asterisk (*, P < 0.05). (E, F) FLT3 inhibitor sorafenib was selected for the treatment of three chemorefractory AML patients based on ex vivo DSRT and molecular profiling. ITD-AR and HLF expression were retrospectively correlated with clinical response to sorafenib. The treatment outcomes were defined as complete remission with incomplete hematological recovery (CRi), partial remission (PR) and resistant disease (RD) evaluated based on ELN 2017 criteria.

Our cohort included four chemorefractory AML patients treated with sorafenib based on DSRT results under off-label compassionate usage as part of a leukemia precision medicine program. Three patients had high ITD-AR and HLF expression whereas one had low ITD-AR (Supplemental Table 9). Clinical responses to sorafenib were observed in the patients with high ITD-AR and HLF expression, while the low ITD-AR and HLF expressing patient lacked response (Fig. 2E). Further analysis of ITD-AR and HLF expression in serial samples collected at different time points from patient 048 showed consistent results suggesting that ITD-AR associates with FLT3 inhibitor responses in vivo (Fig. 2F).

Taken together, the preliminary analyses of FLT3 inhibitor treated patients support that ITD-AR and associated HLF gene expression changes can improve the prediction FLT3 inhibitor efficacy in adult FLT3-ITD+ AML. The ex vivo results suggest that highly selective FLT3 inhibitors have more prominent responses in FLT3-ITD+ AML patients with high ITD-AR regardless of disease stage, while patients with low ITD-AR show stronger responses to non-selective kinase inhibitors targeting FLT3 (e.g. midostaurin). Based on the preclinical data, FLT3-ITD+ AML patients with high ITD-AR at diagnosis may respond well to gilteritinib, which currently lacks regulatory approval for newly diagnosed AML with FLT3 mutation. We suggest that HLF expression together with ITD-AR should be evaluated further as a potential dual-biomarker approach for treatment selection of FLT3-ITD+ AML.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was performed with the approval of Helsinki University Hospital Ethics Committee (permit numbers: 239/13/03/00/2010 and 303/13/03/01/2011) and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. A written informed consent was acquired from all patients before sample collection.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patients for taking part in this study. We also thank Minna Suvela and Siv Knaappila for their excellent technical support. We are grateful for staff at the FIMM Technology Center High-Throughput Biomedicine Unit and Sequencing Laboratory for their help with DSRT and sequencing experiments, respectively.

Abbreviations

- AML

Acute myeloid leukemia

- AR

Allelic ratio

- BM

Bone marrow

- CI

Confidence interval

- DSRT

Drug sensitivity and resistance testing

- DSS

Drug sensitivity score

- FDR

False discovery rate

- FLT3

FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3

- HLF

Hepatic leukemia factor

- ITD

Internal tandem duplication

- qPCR

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- R/R

Relapsed or refractory

- sDSS

Selective drug sensitivity score

- WT

Wild type

Author contributions

J.K., D.M., and A.K. designed the study, analyzed data, prepared figures, and wrote the first draft. J.K. performed FLT3-ITD fragment analysis and high-throughput flow cytometry. A.K. analyzed RNA- and exome-sequencing data. A.P. performed qPCR. M.K. provided patient samples and clinical information. O.K. and C.A.H. provided infrastructure for the work. C.A.H. supervised the work. All authors contributed to manuscript preparation and approved the final version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Cancer Society of Finland, Sigrid Jusélius Foundation, and Finnish Funding Agency for Technology and Innovation (grant number 40336/09). Personal grant support was received from Cancer Society of Finland (JK, AK, DM), Finnish Hematology Association (JK, AK, DM), Finnish Cultural Foundation (JK, DM), Ida Montin Foundation (AK, DM), Maud Kuistila Foundation (DM), Biomedicum Foundation (DM), K. Albin Johansson Foundation (DM), Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation (DM), and Sigrid Jusélius Foundation (JK).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Jarno Kivioja and Disha Malani.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-03010-7.

References

- 1.Chen F, Sun J, Yin C, Cheng J, Ni J, Jiang L, et al. Impact of FLT3-ITD allele ratio and ITD length on therapeutic outcome in cytogenetically normal AML patients without NPM1 mutation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Dohner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, Amadori S, Appelbaum FR, Buchner T, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood. 2017;129(4):424–447. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-08-733196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu SB, Dong HJ, Bao XB, Qiu QC, Li HZ, Shen HJ, et al. Impact of FLT3-ITD length on prognosis of acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2019;104(1):e9–e12. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2018.191809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Papaemmanuil E, Dohner H, Campbell PJ. Genomic classification in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl. J. Med. 2016;375(9):900–901. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1608739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stone RM, Mandrekar SJ, Sanford BL, Laumann K, Geyer S, Bloomfield CD, et al. Midostaurin plus chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia with a FLT3 mutation. N Engl. J. Med. 2017;377(5):454–464. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perl AE, Martinelli G, Cortes JE, Neubauer A, Berman E, Paolini S, et al. Gilteritinib or chemotherapy for relapsed or refractory FLT3-mutated AML. N Engl. J. Med. 2019;381(18):1728–1740. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1902688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daver N, Schlenk RF, Russell NH, Levis MJ. Targeting FLT3 mutations in AML: review of Current knowledge and evidence. Leukemia. 2019;33(2):299–312. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0357-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmalbrock LK, Dolnik A, Cocciardi S, Strang E, Theis F, Jahn N, et al. Clonal evolution of acute myeloid leukemia with FLT3-ITD mutation under treatment with midostaurin. Blood. 2021;137(22):3093–3104. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020007626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kivioja JL, Thanasopoulou A, Kumar A, Kontro M, Yadav B, Majumder MM, et al. Dasatinib and navitoclax act synergistically to target NUP98-NSD1(+)/FLT3-ITD(+) acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Kiyoi H, Naoe T. Biology, clinical relevance, and molecularly targeted therapy in acute leukemia with FLT3 mutation. Int. J. Hematol. 2006;83(4):301–308. doi: 10.1532/IJH97.06071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malani D, Yadav B, Kumar A, Potdar S, Kontro M, Kankainen M, et al. KIT pathway upregulation predicts dasatinib efficacy in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2020;34(10):2780–2784. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-0978-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cucchi DGJ, Denys B, Kaspers GJL, Janssen J, Ossenkoppele GJ, de Haas V, et al. RNA-based FLT3-ITD allelic ratio is associated with outcome and ex vivo response to FLT3 inhibitors in pediatric AML. Blood. 2018;131(22):2485–2489. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-12-819508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar A, Kankainen M, Parsons A, Kallioniemi O, Mattila P, Heckman CA. The impact of RNA sequence library construction protocols on transcriptomic profiling of leukemia. BMC Genom. 2017;18(1):629. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-4039-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tyner JW, Tognon CE, Bottomly D, Wilmot B, Kurtz SE, Savage SL, et al. Functional genomic landscape of acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2018;562(7728):526–531. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0623-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wahlestedt M, Ladopoulos V, Hidalgo I, Sanchez Castillo M, Hannah R, Sawen P, et al. Critical modulation of hematopoietic lineage fate by hepatic leukemia factor. Cell Rep. 2017;21(8):2251–2263. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.10.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garg S, Reyes-Palomares A, He L, Bergeron A, Lavallee VP, Lemieux S, et al. Hepatic leukemia factor is a novel leukemic stem cell regulator in DNMT3A, NPM1, and FLT3-ITD triple-mutated AML. Blood. 2019;134(3):263–276. doi: 10.1182/blood.2018862383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.