Abstract

Interruptions are germane to inpatient medical practice but carry the consequences of reduced error prevention, psychological stress, and impaired knowledge consolidation among trainees. In this mixed methods study, we captured 172 task changes via time-motion observations of four residents on a general neurology service and completed semi-structured interviews with the same group. Twenty-five percent of task changes were due to interruptions, the majority via pager communications, and only 2% required urgent clinical attention. Residents reported frustration towards inefficient aspects of the pager system. Given the high rates of interruptions identified, we propose mitigating strategies such as triaging communications by urgency.

Keywords: Graduate medical education, Residency, Learning environment

Background

Interruptions in inpatient medical practice cause compromised clinical decision-making, reduced error processing and prevention, and psychological stress [1]. Relevant studies have focused primarily on nursing staff and emergency department (ED) physicians, leading to mitigating strategies such as “do not disturb” periods for cognitively demanding activities [2] and modification of electronic health record (EHR) systems to facilitate easy resumption of an interrupted task [3]. In contrast, there is limited literature on the nature of disruptions outside of ED settings, particularly among trainees. One notable exception is a study of interruptions among medical residents in an Australian hospital, finding that pager communications frequently interrupted important activities, with only 27% of pages considered appropriate and urgent [4]. The majority led to switches from a more clinically important task such as direct patient care to a less important one.

In this brief mixed methods study, we sought to characterize the nature of interruptions among residents in an American hospital by characterizing the frequency of task changes (defined as any transition from one continuous activity to another of a different type) and the percentage that are secondary to interruptions. We combined time-motion observation studies, in which an external observer captures detailed data on the duration and nature of tasks in a work environment with an aim to improve efficiency, and semi-structured interviews to characterize interruptions experienced by a small group of residents, prioritizing depth of both quantitative and qualitative data over breadth.

Activity

Empirical Setting and Participants

This institution review board-exempt study (H-39305) was conducted on the general neurology service of a 514-bed tertiary care hospital, selected as it was more representative of an average medical service without a high burden of emergencies as handled by the stroke and neurocritical care services within the same department. General neurology teams consist of one post-graduate-year (PGY) 2 resident, one PGY4 neurology resident, an attending neurologist, and non-neurology team members. The senior resident carries a team pager while other trainees carry personal pagers. The team cares for both primary neurology inpatients and patients on other services via non-urgent consultations, with a median census of 12 patients.

Study Design

In December 2019, one observer trained in completing time-motion studies by reviewing similar works [5] with the senior author spent four days shadowing one resident each day during their afternoon shifts, selected randomly based on observer availability. After obtaining their consent to participate in the quality improvement study, the observer recorded their activities with time stamps using a note taking tool on an iPad. Activities were categorized into five groups created a priori using a taxonomy modeled after prior studies [5]. (1) Direct patient care was defined as face-to-face activities with patients, including history taking, examination, and counseling. (2) Indirect patient care was defined as activities that contribute to patient care requiring the expertise of a physician. (3) EHR use was defined as activities during which the resident is primarily engaged with the computer, including documentation, reading electronic notes, and placing orders. (4) Logistical tasks were defined as activities that do not require physician expertise, such as confirming follow-up appointments. (5) “Other” was defined as any activity not captured by the other four groups, including movement between locations and breaks. Following these observations, the activities were graphed against shift time using logged time stamps, generating visual heat maps for each shift. The total time dedicated to each activity type was also summated and graphed.

Immediately following each observation, the external observer engaged the resident in a half-hour semi-structured interview with eight open-ended questions focused on residents’ overall impression of their shift, without explicit questions regarding interruptions. Questions included “Was there anything that frustrated you today?” and “Is there any part of your workflow that you think could be made more efficient?” The observer also conducted an abbreviated interview with the attending physicians on the same teams for a total of six interviews. The interviews were transcribed by the observer. After all interviews were completed, the first and senior authors independently analyzed contents of the first two interviews to identify initial patterns in responses, then consolidated these into three themes, which were then used to analyze the remaining interviews and group responses into these themes.

Results

Time-Motion Observations

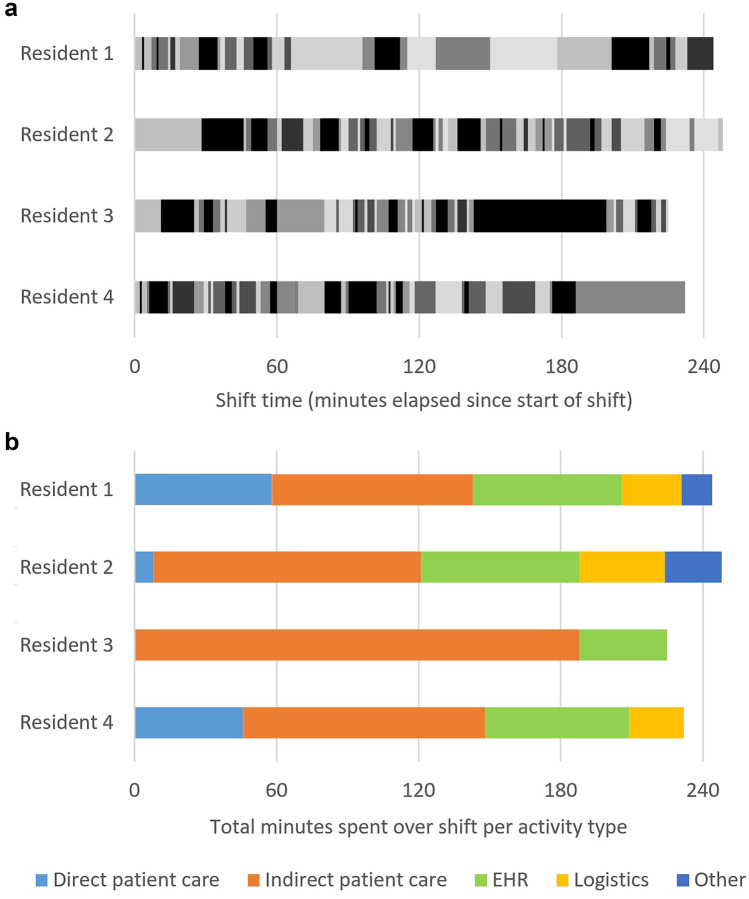

Residents switched tasks 7–13 times per hour, as shown in visual heat maps in Fig. 1a in which each change in grayscale shade represented a change in task. The distribution of total time per activity type is shown in Fig. 1b. A total of 172 task changes for the four shifts were observed, 25% due to interruptions, among which 61% were via pager communications, and the remainder via in-person interactions. Interruptions occurred most frequently while residents were engaged with the EHR (71%). Only 2% of interruptions required urgent medical attention due to a change in a patient’s clinical status.

Fig. 1.

a Heat map visualization of resident activities demonstrating task changes over each shift. Each grayscale shade represents a different task, and each change in shade represents a task switch. b Distribution of total minutes spent collectively on each activity type for each shift. EHR, electronic health record

Semi-Structured Interviews

The interviews revealed three themes. The first was frustration towards logistical inefficiencies of the pager system. One resident stated that pager communications represented the single most frustrating part of his day, while another commented that individual paging communications required brief attention but summated to a large proportion of his day. When asked about frustrations, one resident cited the one-way nature of pager communications:

Trying to be quick about responding to pages and then not being able to get in touch with the person who paged.

Another proposed a better system at a different hospital:

At [another site], the floors in the hallways have a different extension – this would be better; referral to the front desk [at the main hospital] wastes time; the front desk calls the nurse to physically walk over to the phone.

A second theme was stress related to interrupted patient care. One attending physician cited that freedom from carrying a resident pager while providing patient care contributed greatly to her reduced work stress. One resident was explicit in saying that having more continuous time with patients may improve care and communication:

Having more time with patients would let you ask more questions.

A third theme was found incidentally that residents felt they spent too much time on the EHR:

Reducing the amount of time spent on [the EHR system] would reduce burnout.

I spend all day on [the EHR system].

I probably spend 8 out of 12 h on the computer.

Discussion

Although neurology residents were interrupted fewer times per hour than reported for ED physicians [6], the proportion of total task switches triggered by interruptions was alarmingly high. In addition, we found that (1) a vast majority of inpatient paging communications did not require an urgent response, as found in the Australian-based study [4], (2) interruptions frequently distracted from cognitively demanding tasks such as EHR documentation, and (3) interruptions were psychologically stressful. A recent study of interruptions experienced by ED staff argued that ED physicians are a self-selected group that may thrive in disrupted work environments and that distractions are necessary and expected in their workflow [7], neither notion applicable to neurology residents.

Organizational behavior research suggests that reducing distractions in the workplace requires systemic changes rather than individual changes [8]. Given that the majority of interruptions are pager communications, there have been appropriate efforts to reduce paging burden among clinicians, thus far met with mixed results. A recent study compared a novel instant messaging application with the traditional pager system to find that physicians saved 48 min per shift on average [9]. In a second study, staff were encouraged to specify the level of urgency for every pager communication, resulting in a reduction of “difficult to triage” pages by 40% but, as expected, no change in the total volume of communications [10]. In a third study, a web-based communication system resulted in an increase in number of communications received per resident and 233% more interruptions, an unintended consequence of its ease of use [11].

Our findings suggest that in addition to triaging urgency, alerts for non-urgent communications should be delayed. For example, urgent communications as determined by the sender may sound an immediate alert (e.g., patient’s change in clinical status requiring bedside evaluation); semi-urgent communications are logged and an hourly alert reminds residents to check interim communications (e.g., medication request for non-urgent medical issue such as constipation); and non-urgent communications are checked at the end of the day for which an hour is budgeted (e.g., request to fix documentation error for recently discharged patient). This stratified alert system may apply to communication systems other than pagers, such as smartphones. Other mitigating strategies may be promoted systemically, such as standardizing scheduled communications between the clinician team, nursing, and ancillary staff to reduce the need for ad hoc communications.

Our finding of perceived EHR overuse is a subject of active investigation among medical education and informatics experts [12, 13] beyond the scope of this article. Its corollary of reduced direct patient care time is under equal scrutiny [14]. However, we note that interruptions may lead to both the overestimation of and true increase in time spent on the EHR, with time and cognitive bandwidth wasted in the process of resuming a previously interrupted task. As such, future works focused on EHR overuse in medical training or in medical practice should take workflow interruptions into account.

Our study has several limitations, first of which is the small sample size of trainees observed at a single-institution, as we had prioritized depth of data combining quantitative time-motion observations and qualitative interviews over breadth. Generalizability is obviously limited by inter-institutional variations in workflow and communication systems, necessitating larger multicenter studies on interruptions among trainees. Second, although the taxonomy of clinical activities was modeled after prior studies, the lack of a validated classification system makes miscategorization possible. Third, although the observer was external to program leadership, resident behavior may be affected by the Hawthorne effect. Finally, we examined the nature of interruptions associated with aforementioned consequences such as clinical errors but did not study these consequences directly, which may represent the basis of a future study. In terms of other next steps, it would be important to study the effects of mitigating strategies via future time-motion observation–based studies complemented by qualitative data. For example, our service had adopted the use of smartphones since the conclusion of the study.

Our brief mixed methods study characterized the nature of interruptions experienced by residents on a non-emergency medical service, highlighting high rates of unnecessary task switches, especially from cognitive demanding tasks, and the associated stress of distractions. It suggests the feasibility of similar efforts at other institutions to first understand workflow disruptions specific to their systems followed by identifying potential solutions. Given recent attention on physician burnout particularly among trainees, a close examination of modifiable sources of workplace stress represents a worthy endeavor.

Author Contribution

All the authors met the journal criteria for authorship.

Availability of Data and Material

Data available upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

Institutional IRB exemption was obtained.

Consent to Participate

N/A

Consent for Publication

N/A

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Morrison JB, Rudolph JW. Learning from accident and error: avoiding the hazards of workload, stress, and routine interruptions in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(12):1246–1254. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01231.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Myers RA, Parikh PJ. Nurses’ work with interruptions: an objective model for testing interventions. Health Care Manag Sci. 2019;22(1):1–15. doi: 10.1007/s10729-017-9417-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ratwani RM, Fong A, Puthumana JS, Hettinger AZ. Emergency physician use of cognitive strategies to manage interruptions. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;70(5):683–687. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ly T, Korb-Wells CS, Sumpton D, et al. Nature and impact of interruptions on clinical workflow of medical residents in the inpatient setting. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(2):232–237. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00040.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mamykina L, Vawdrey DK, Hripcsak G. How do residents spend their shift time? A time and motion study with a particular focus on the use of computers. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2016;91(6):827–832. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blocker RC, Heaton HA, Forsyth KL, et al. Physician, interrupted: workflow interruptions and patient care in the Emergency Department. J Emerg Med. 2017;53(6):798–804. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2017.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fong A, Ratwani RM. Understanding emergency medicine physicians multitasking behaviors around interruptions. Acad Emerg Med Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med. 2018;25(10):1164–1168. doi: 10.1111/acem.13496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen J, LaRue C, Cohen H. Attention interrupted: cognitive distraction & workplace safety. Prof Saf. 2017;62(11):28–34. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menon R, Rivett C. Time-motion analysis examining of the impact of Medic Bleep, an instant messaging platform, versus the traditional pager: a prospective pilot study. Digital Health. 2019;5:2055207619831812. doi: 10.1177/2055207619831812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cawkwell PB, O’Neill M, Hill EL, et al. Improving communication between nursing staff and on-call residents via a standardized paging protocol. Academic psychiatry : the journal of the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training and the Association for Academic Psychiatry. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Quan SD, Wu RC, Rossos PG, et al. It’s not about pager replacement: an in-depth look at the interprofessional nature of communication in healthcare. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(3):137–143. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gagliardi JP, Turner DA. The electronic health record and education: rethinking optimization. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(3):325–327. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-15-00275.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robertson SL, Robinson MD, Reid A. Electronic health record effects on work-life balance and burnout within the I(3) population collaborative. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(4):479–484. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00123.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joukes E, Abu-Hanna A, Cornet R, de Keizer NF. Time spent on dedicated patient care and documentation tasks before and after the introduction of a structured and standardized electronic health record. Appl Clin Inform. 2018;9(1):46–53. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1615747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon reasonable request.