Abstract

Background

The American Medical Association considers health advocacy to be a core aspect of a physician’s responsibility, which has sparked medical schools to institutionalize training. However, there is little information regarding student perspectives on advocacy education.

Purpose

To evaluate medical student opinions on advocacy education and to determine similarities and differences across classes.

Methods

In this qualitative study, four focus groups were conducted with five to eight students from each medical school class. Students were randomly selected from rosters and received an email to participate. Sessions were audiotaped and transcribed, and demographic data was obtained. Investigators reviewed transcripts independently and identified important items in each transcript then consolidated common themes into groups. These themes were integrated into concept map representations.

Results

Of those contacted, 25 (16%) students chose to participate in focus group sessions. All participants who responded to questionnaires (n = 24) identified advocacy in medicine as very important. Definitions of advocacy varied among students and classes. Common themes in all focus groups included feeling overwhelmed by advocacy due to lack of time, lack of perceived prioritization in medical education, feelings of imposter syndrome, and inability to align individual views with healthcare systems. Another common theme was frustration that students learned of advocacy through didactic sessions rather than engagement in advocacy work.

Conclusions

All participating students identified advocacy as an important aspect of medicine, yet students felt inadequately prepared to participate in advocacy work. This reveals an opportunity to improve upon the formal education needed to engage in advocacy.

Keywords: Advocacy, Medical education, Health education, Advocacy training

Introduction

The American Medical Association defines advocacy as a core aspect of a physician’s social responsibility [1]. Health advocacy is broadly considered to be any social, economic, educational, or political change that ameliorates suffering or potential dangers to health and well-being of patients, families, and society [2]. Despite this perceived role for physicians, there is not a clear understanding of what advocacy entails or how to pass this knowledge to learners. Studies have shown advocacy training improves knowledge of community health needs and resources, leading to increased empowerment and engagement [3, 4]. Thus, determining how to best educate medical students as advocates is vital.

To fully prepare medical students to become health advocates, medical schools are institutionalizing training on advocacy [3, 5]. Several medical schools have adjusted their curricula to address social determinants of health, but students have often found these lectures do not prepare them to successfully advocate in their future careers [6]. Without proper training, future healthcare providers will be left without the necessary tools to engage in advocacy work efficiently and effectively [2, 3].

At the University of Kansas School of Medicine, there is currently no formal training in place for health advocacy, making student exposure to information and training variable. In this qualitative study, we aimed to evaluate medical student perceptions of advocacy and training within our institution.

Methods

Data were collected using focus group methodology, utilizing a stratified approach based on a medical school year. Participants were students from the Kansas City campus of the University of Kansas School of Medicine. A cohort of 16 students was selected randomly from each class roster and received a preliminary invitation to participate link via email. This process was repeated until a minimum of 5 (maximum of 8) students per class was achieved. Fourth-year students who had previously completed a required fourth-year course on population health were excluded due to phasing out of the course after the 2019–2020 academic year. Participants were not rewarded monetarily but received snacks/refreshments during the sessions.

Focus groups were held in-person over the course of 2 weeks in February 2020. Preliminary emails were sent to 160 students, and 25 (16%) students agreed to participate. Verbal informed consent was obtained from each individual participant at the beginning of each focus group. Demographic data were collected on hardcopy forms and manually entered by investigators in REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) [7, 8]. REDCap is a secure, web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research studies.

All four focus groups were facilitated by one investigator utilizing a semi-structured moderator’s guide of standardized questions. Focus group discussions reached saturation, and no new information was obtained, so opinions were considered complete. Students for each focus group were assigned a number (1–8) to limit use of personal identifiers. Focus groups were audio and video recorded through Panopto™, and transcripts were created for each group. The transcripts provided through Panopto were assessed and edited for accuracy as needed. The audio recordings and transcripts were then uploaded into the secure REDCap database. Video recording was used to identify speakers. An additional investigator recorded on a mobile device and took notes throughout each session. The following questions were asked in every focus group with modifications as guided by the individual groups and previous focus groups:

What does being a health advocate mean to you?

How has your medical education thus far informed you about health advocacy?

Do you foresee health advocacy being a part of your future practice? If so, how?

Do you see any personal or professional conflicts of interest in regard to health advocacy?

Should health advocacy be required for all physicians?

Data analysis followed a grounded theory approach and was conducted with direction from an individual experienced in qualitative analysis [9]. Five investigators independently reviewed all transcripts and identified important items in each transcript in the open coding process. Investigators then collaboratively reviewed the items and categorized them into themes based on subject grouping. Consensus was reached with discussion among investigators, and themes were revised as needed. This iterative approach continued until no new information was identified. Visual concept maps were created for each group based on these themes. The concept maps helped to exemplify relative theme strength and emphases from the four groups of study participants.

Results

Over the course of the study, 25 students from all four medical school years ultimately signed up to join four focus groups. Demographic data from the four groups are presented in Table 1. Notably, the second-year medical students all identified as female, though genders were more equally represented within the other groups. Of the 25 total participants in all four groups, 24 responded to written questions related to the perceived importance of advocacy. All 24 respondents perceived advocacy to be very important in medicine, but when asked about personal interest in advocacy, only half (n = 12) indicated that it was very important to them.

Table 1.

Participant demographics

| MS1 | MS2 | MS3 | MS4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (n = 25) | |||||

| Female | 4 | 6 | 3 | 3 | |

| Male | 4 | 0 | 2 | 3 | |

| Age (n = 25) | |||||

| 22–24 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 0 | |

| 25–27 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 27–29 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| >29 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Specialty interest (n = 24) | |||||

| Anesthesiology | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Dermatology | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Emergency medicine | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Family medicine | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | |

| Internal medicine | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Medicine-pediatrics | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Neurology | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pediatrics | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Radiology | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Surgery | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| Undecided | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hours of extracurricular involvement per week (n = 23) | |||||

| 0–5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 2 | |

| 6–10 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| 11–15 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| >15 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Perceived importance of advocacy in medicine (n = 24) | |||||

| Very important | 8 | 6 | 5 | 6 | |

| Slightly important | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Not important | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Personal interest in advocacy (n = 24) | |||||

| Very important | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| Slightly important | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | |

| Not important | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

MS1 first-year medical student, MS2 second-year medical student, MS3 third-year medical student, MS4 fourth-year medical student

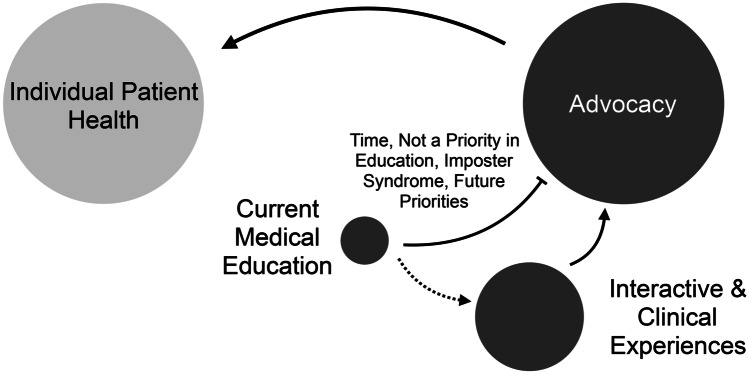

Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4 represent conceptual maps of themes among the four focus groups. Importance of the theme as determined by each group is indicated by size. Within the first-year medical student group, the first theme was that advocacy was believed to be practices that improve the overall health of individual patients. There was a focus on how advocacy affects the health of patients seen directly in practice. The first-year participants identified a second theme that their formal education was limited to didactics on social determinants of health. They acknowledged these lectures occurred early in the curriculum and assumed that training on the tools to apply that knowledge would come during the next three years. The third theme was that students felt overwhelmed by the process of engaging in advocacy. First-year medical students felt there were numerous reasons for this, including lack of time, advocacy not being a priority in education, imposter syndrome as students, and the potential of a trade-off with future priorities. Students believed there would be consequences for providers who chose to advocate for positions that cost money for or differ from that of the healthcare system for which they work. In terms of imposter syndrome, one student described:

I wish there was a roadmap for this stage in my career [on] how to be helpful, because it feels…as a student I’m not. I don’t know…my role in the healthcare system.

Fig. 1.

First-year medical student focus group concept map

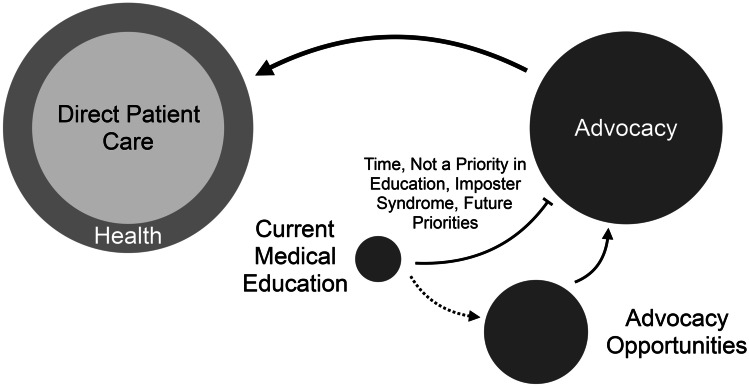

Fig. 2.

Second-year medical student focus group concept map

Fig. 3.

Third-year medical student focus group concept map

Fig. 4.

Fourth-year medical student focus group concept map

Finally, the fourth theme was that students valued advocacy training through interactive or clinical experiences. Again, first-year students assumed that this training would occur later in their medical education.

Among the second-year medical student group, the first theme was that advocacy was seen as using one’s voice to empower patients. Students believed their unique voices as medical professionals should be used to achieve their patients’ goals. Second-year students shared the same second and third theme as MS1s that formal education was limited to didactics on social determinants of health and that students felt overwhelmed by the process of engaging in advocacy. They echoed that there were numerous barriers that kept them from aggressively pursuing advocacy efforts at this stage in their education. The fourth theme was that there is a need to incentivize advocacy training within medical education. Students thought the creation of incentives, such as receiving a grade for a dedicated course, may make advocacy more of a priority compared to test scores, which they felt were the current priority in medical education.

For third-year medical students, the first theme was that advocacy was seen as promoting health beyond direct patient care. This group outlined a distinction between care for their individual patients and overall public health. Students identified a second theme that there was a lack of formal education on training of advocacy. They felt that there was general education on advocacy topics but that they did not have the tools to move beyond that knowledge. Like the previous groups, the third theme of the third-year group was that students felt overwhelmed by the process of engaging in advocacy. As one student stated:

If you don’t know anything about [advocacy], it can seem so big. You can’t do anything. But the more you learn, you realize what things can be done.

The final theme identified by third-year students was that there is importance in intentionally creating opportunities to align with student passions. Multiple students stated that it may be difficult to standardize advocacy training due to the variety of specialties and specific opportunities within those. However, as students begin to identify their passions, they can choose to engage in opportunities that may align with their future practice.

Within the fourth-year medical student group, there were many similarities with previous groups. The first theme was that advocacy was viewed as practices that improve the overall health of individual patients, which was the same as the first-year group. However, like the third-year students, their second theme was that there was a lack of formal education on training of advocacy. There was again the perception that their medical education did not involve the active training for various avenues of advocacy. One fourth year expressed:

We all want to be advocates…but [do not have]…the actual skills to do so.

Fourth-year students identified a third theme that there would be value in intentionally creating opportunities to align with student passions, which was the same as the third-year students. They reiterated several times that students may not be enthusiastic about training that does not apply to their future career goals but believed that general training to gain tools was important for any medical professional. Those tools could then be incorporated in existing opportunities within chosen specialties for students. This tied in with the fourth theme that there would also be utility in concrete education or examples of advocacy. Students believed that the combination of these examples with future opportunities would be more useful within the curriculum than current electives. Some suggestions for these concrete examples included pairing with physician mentors and enrichment week activities.

Discussion

This study uncovered several common themes among the four focus groups. The most consistent theme across the four classes was feeling overwhelmed by the process of engaging in advocacy. There were a multitude of sub-themes or barriers causing students to feel overwhelmed by engaging in advocacy, with the sub-theme echoed the most being a lack of time to devote to advocacy work or learning. This idea ties into another barrier that students identified, which was that advocacy was not a perceived priority in current medical education. Other barriers included student’s belief that as learners they were inadequate or illegitimate and the fear of their advocacy work not aligning with the healthcare system in which they work. Many students believed there would be repercussions by employers for providers who participated in advocacy work. Though none of the four groups gave concrete examples, they all echoed that there would be fear of losing their jobs if their employers or the larger health system within which they worked were to disagree with their advocacy efforts.

Another theme with overlap between classes was tied to current education on advocacy. Both first-year and second-year students believed formal education was limited solely to lectures on the social determinants of health. These first and second years both had assumptions they would receive specific education and training on skills to become advocates in the third and fourth-year curriculum. One such skill as described by a second-year student was how to prepare to speak with legislators about medical topics and related patient experiences. Interestingly, third- and fourth-year students nearing the end of their respective years believed they still did not receive training nor possess the skills to advocate effectively in the future.

These findings highlight a need for curricula to include more robust and concrete advocacy education and training. As the attitude towards board exam scores shifts within medical education, there is a unique opportunity to focus attention on other important tools that students deem valuable [10–12]. Students expressed interest in experienced-based learning, including pairing with engaged physician mentors and enrichment week activities, to gain these tools. If these experiences were included within curricula and tied to credit, students believed that they would be incentivized to participate. They also felt that opportunities should grow as students become more focused on their specialty of choice. Rather than subjecting all students to the same opportunities and projects, students should engage where they feel compelled. However, without specific electives or projects, students may still feel overwhelmed and stifled by a lack of guidance.

One strength of this study was the qualitative nature. Having a qualitative approach with focus groups allowed the investigators to understand attitudes and beliefs better than what a survey may have provided. Focus groups also gave investigators an opportunity to clarify opinions and ideas at the time of discussion.

Limitations of this study include possible self-selection bias. Students were randomly selected to participate, but those that signed up may have been more interested in advocacy compared to their classmates. Additionally, the sample size was small compared to overall class sizes, especially within the fourth-year class due to exclusion criteria, and thus, results may not reflect opinions of the entire student body. Future studies may further investigate opportunities that students find valuable and how those can be implemented into existing curricula.

Our study highlights the perceived importance of advocacy in medicine among medical students and several barriers in place that prevent students from seeking opportunities for advocacy. By implementing specific and intentional curricula on advocacy topics and tools, medical schools may better prepare students to tackle the challenges that they may face as physicians and help create meaningful change for patients.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Rana Aliani, upon reasonable request.

Code Availability

No software was used in the iterative open coding process.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

The Institutional Review Board at the University of Kansas Medical Center confirmed no approval was required for this study.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study. All students who participated in this study signaled their verbal agreement to participate prior to the start of each focus group. Participation was voluntary.

Consent for Publication

Participants provided consent for publication during the verbal consent process.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.American Medical Association. Declaration of professional responsibility. American Medical Association Web site. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/ama-declaration-professional-responsibility. Accessed 28 May 2020.

- 2.Luft L. The essential role of physician as advocate: how and why we pass it on. Can Med Educ J. 2017;8(3):e109–e116. doi: 10.36834/cmej.36925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belkowitz J, Sanders L, Zhang C, Agarwal G, Lichtstein D, Mechaber A, Chung E. Teaching health advocacy to medical students: a comparison study. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2014;20(6):E10–E19. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Croft D, Jay S, Meslin E, Gaffney M, Odell J. Perspective: is it time for advocacy training in medical education? Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1165–1170. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31826232bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Douglas A, Mak D, Bulsara C, Macey D, Samarawickrema I. The teaching and learning of health advocacy in an Australian medical school. Int J Med Educ. 2018;9:26–34. doi: 10.5116/ijme.5a4b.6a15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhate TD, Loh LC. Building a generation of physician advocates: the case for including mandatory training in advocacy in Canadian medical school curricula. Acad Med. 2015;90(12):1602–1606. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, McLeod L, Delacqua G, Delacqua F, Kirby J, Duda SN. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charmaz, K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. 2006.

- 10.Desai A, Hegde A, Das D. Change in reporting of USMLE Step 1 scores and potential implications for international medical graduates. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2015–2016. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaudhry HJ, Katsufrakis PJ, Tallia AF. The USMLE Step 1 decision: an opportunity for medical education and training. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2017–2018. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crane MA, Chang HA, Azamfirei R. Medical education takes a step in the right direction: where does that leave students? JAMA. 2020;323(20):2013–2014. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Rana Aliani, upon reasonable request.

No software was used in the iterative open coding process.