Abstract

Objectives: It is reported that inflammation- and nutrition-related indicators have a prognostic impact on multiple cancers. Here we aimed to identify a prognostic nomogram model for prediction of overall survival (OS) in surgical patients with tongue squamous cell carcinoma (TSCC). Methods: The retrospective data of 172 TSCC patients were charted from the Cancer Hospital of Shantou University Medical College between 2008 and 2019. A Cox regression analysis was performed to determine prognostic factors to establish a nomogram and predict OS. The predictive accuracy of the model was analyzed by the calibration curves and the concordance index (C-index). The difference of OS was analyzed by Kaplan–Meier survival analysis. Results: Multivariate analysis showed age, tumor node metastasis (TNM) stage, red blood cell, platelets, and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio were independent prognostic factors for OS, which were used to build the prognostic nomogram model. The C-index of the model for OS was 0.794 (95% CI = 0.729-0.860), which was higher than that of TNM stage 0.685 (95% CI = 0.605-0.765). In addition, decision curve analysis also showed the nomogram model had improved predictive accuracy and discriminatory performance for OS, compared to the TNM stage. According to the prognostic model risk score, patients in the high-risk subgroup had a lower 5-year OS rate than that in a low-risk subgroup (23% vs 49%, P < .0001). Conclusions: The nomogram model based on clinicopathological features inflammation- and nutrition-related indicators represents a promising tool that might complement the TNM stage in the prognosis of TSCC.

Keywords: tongue squamous cell carcinoma, clinical features, nutrition, inflammation, prognosis

Introduction

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is a serious problem in many countries of the world, which is expected to account for around 35 130 cases of incident cancer in the United States in 2019, and tongue squamous cell carcinoma (TSCC) is the most common type of OSCC, with an increasing incidence in many European countries.1,2 The incidence and mortality trends of oral and oropharyngeal cancers in China show an increasing trend. 3 It was estimated that 285 857 new cases and 132 698 deaths were associated to oral and oropharyngeal cancers in China between 2005 and 2013, and tongue cancers being one of the most frequently diagnosed and the leading causes of death among all oral and oropharyngeal cancers. 4 In the past decades, the poor survival of TSCC patients have not been obviously improved, mostly attributing to regional recurrence and the metastasis of cervical lymph node, bloodstream, and distant organs.5,6 Although tumor node metastasis (TNM) stage system is the primary basis in estimating the prognosis of TSCC, it is based fully on the anatomical range of the disease, which has limitations for survival analysis of TSCC patients. 7 Therefore, there is still a lack of more effective approaches to assess TSCC patient's prognosis.

It is known that systemic inflammation- and nutrition-related markers play important role in both the development and the spread of human cancers.8,9 For example, some studies demonstrated that white blood cell count (WBC) was a predictor for cancer. 10 WBCs are mainly composed of neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes. Compelling evidence suggests that these leukocytes may be closely related to patients with different cancers. More recently, evidences have suggested that a high pretreatment neutrophil count (NC) and monocyte count (MC) levels in the blood are associated with poor outcomes in many cancer types,11–14 including tongue cancer. 15 In contrast, a higher preoperative lymphocyte count (LC) appears to be associated with favorable outcomes for several types of cancers.16,17 In addition, nutritional indexes, like red blood cell (RBC) and hemoglobin (HGB), have been also reported to be associated with cancer prognosis.9,18 For example, low RBC count was a risk factor of deep myometrial invasion in endometrioid endometrial carcinoma (EEC), 9 and preoperative anemia predicts poor survival outcomes in patients with endometrial cancer. 19 Preoperative low RBC count showed a negative association with tumor size in oral cancer. 20 The bloodstream is a major pathway for the dissemination of cancer cells, especially in patients with tongue cancer. Circulating platelets (PLT) play a role in vascular thrombosis, atherosclerosis, and inflammation. On the other hand, platelets mediate activation of coagulation and fibrinolytic systems in the causation and metastasis of cancers.21,22 Interestingly, tumor cell can induce platelet aggregation, which leads to tumor cell adhesion to vascular endothelium and facilitate tumor cell growth and invasion. 23 Increasing evidence indicates that elevated preoperative platelet count may be a predictive factor of poorer prognosis and unfavorable clinicopathological parameters for cancer patients. 24 platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) is a known inflammatory marker of a derivative index of platelet and lymphocyte, which is considered as a potential marker of the diagnosis and prognosis of cancers in a variety of studies.25–28 Patients with high pretreatment blood PLR levels have poorer overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) in various solid tumors.29,30 Although inflammation- and nutrition-related indexes have been studied as prognostic factors in head and neck cancers, there is an insufficient study on hematological prognostic markers in TSCC.

In the present study, we established a nomogram based on the evaluation of the value of age, tumor node metastasis (TNM) stage, pretreatment RBC count, leukocyte and platelet indices to predict the prognosis of patients with TSCC after surgery, thus providing an additional parameter to help guide the management of TSCC patients.

Methods and Materials

Study Population and Data Collection

We designed a retrospective observational study by retrieving data of 172 patients who underwent surgery with TSCC, from the Cancer Hospital of Shantou University Medical College from July 2008 to January 2019. Patients were enrolled in the analysis with the following criteria: (1) they were diagnosed as TSCC by histopathology; (2) they did not suffer from any cancer diseases before TSCC diagnosis or undergo any anti-cancer treatments; (3) patients with a history of chemoradiotherapy and neoadjuvant therapies were excluded; (4) they had complete baseline clinical information and complete follow-up data. This study was approved by the Hospital Ethics Committee in the Cancer Hospital of Shantou University Medical College in China (approval number 2020054) and verbal informed consents were attained from all participants for the retrospective study of their clinical data. All work was conformed to the principles of the Helsinki Declaration.

The relevant clinicopathological features and hematological data were collected for each patient at the time of diagnosis and before any clinical treatment. Specifically, demographic details such as age and gender, smoking behavior, drinking behavior, and pathologic factors such as pT and pN status, TNM stage, and tumor size were charted. In this study, the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM stage manual was adopted. The potential blood-based prognostic factors included WBC, RBC, HGB, PLT, NC, LC, MC, CRP, ALB. Lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR), PLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte (NLR), C-reactive protein/albumin ratio (CAR), immune-inflammation score (SII), systemic inflammation score (SIS), and prognostic nutritional index (PNI) were further derived from these blood indices.31–33 LMR was calculated as the ratio of the absolute LC to MC. The PLR was calculated as the ratio of the absolute peripheral platelet count to LC, and the NLR was calculated as the ratio of the absolute count of NC to LC. CAR was the ratio of CRP to ALB ratio; SII was calculated by using a formula (SII = NE × LY/PLT); The SIS was defined as follows: patients with Alb level < 40 g/L and LMR < 4.44 were classified as 2; patients with either Alb level ≥ 40 g/L or LMR ≥ 4.44 were classified as 1, and patients with both Alb level ≥ 40 g/L and LMR ≥ 4.44 were classified 0. The PNI was calculated according to the formula: Alb (g/L) + 5 × lymphocyte count (×109/L). In this study, continuous variables were transformed into categorical variables by the X-tile, and then the best cut-off values were obtained.

Patients Follow-Up

The follow-up of patients’ survival data was acquired by retrieving medical records, email, and direct communication by mobile phone. All patients were followed up until death or June 2019. In this study, the terminal point was OS, which was defined from the time of receiving surgery to any form of death and the data were censored for patients who were alive at the date of the last follow-up of June 2019.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed by SPSS software, version 22.0 (SPSS Inc.) and R (version 3.6.1) for Windows. The OS of patients was calculated by the Kaplan–Meier method, and the differences between the survival curves were evaluated with the log-rank test. Univariate analysis was performed to evaluate the importance of potential prognostic factors. Variables with a significant level of P ≤ .05 (2 tailed) in univariate analysis were brought forward to a multivariate analysis by a backward stepwise procedure. The univariate and multivariate Cox regression models were used to calculate the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) to evaluate the impacts of prognostic variables for OS. A predictive nomogram model was established using all variables with a P-value of less than .05 in multivariate Cox regression model by the package of rms in R. In the predictive nomogram model, the prognostic factors of the 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS were analyzed. In addition, the associated calibration curves with bootstrapping (1000 bootstrap resamples) were used to evaluate the predictive ability of 1-, 3- and 5 years OS for the nomograms model. The predictive accuracy and discriminative ability of the prognostic factors were assessed by C-index and decision curve, and were compared with the TNM stage system by using the “survcomp” package. For subsequent analysis, patients were divided into high- and low-risk subgroups according to the optimal cut-off value of the nomogram model risk score. The difference of OS between 2 groups was analyzed by Kaplan–Meier survival analysis. All statistical tests were 2-sided, and P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient Characteristics

The median age for 172 eligible patients were enrolled in this study was 69 years (range: 25-88 years), of which 96 (55.8%) were males and 76 (44.2%) were females. The numbers of patients of I-II and III-IV stages were 121 (70.4%) and 51(20.6%), respectively. At the time of the last follow-up, the median OS was 65 months. In addition, the detailed patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics were summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 96 | 55.8 |

| Female | 76 | 44.2 |

| Age (years) | ||

| <69 | 145 | 84.3 |

| ≥69 | 27 | 15.7 |

| Smoking behavior | ||

| Yes | 73 | 42.4 |

| No | 99 | 57.6 |

| Drinking behavior | ||

| Yes | 38 | 22.1 |

| No | 134 | 77.9 |

| T stage | ||

| T1 + T2 | 150 | 87.2 |

| T3 + T4 | 22 | 12.8 |

| N stage | ||

| N0 | 133 | 77.3 |

| N1 + N2 + N3 | 39 | 22.7 |

| TNM stage a | ||

| I + II | 121 | 70.4 |

| III + IV | 51 | 29.6 |

| Size (cm) b | ||

| <4.20 | 153 | 89.0 |

| ≥4.20 | 19 | 11.0 |

| WBC (109/L) | ||

| <4.95 | 30 | 17.4 |

| ≥4.95 | 142 | 82.6 |

| RBC (109/L) | ||

| <3.96 | 21 | 12.2 |

| ≥3.96 | 152 | 87.8 |

| HGB (g/L) | ||

| <152.00 | 151 | 87.8 |

| ≥152.00 | 21 | 12.2 |

| PLT (109/L) | ||

| <96.00 | 53 | 30.8 |

| ≥96.00 | 119 | 69.2 |

| LC (109/L) | ||

| <1.59 | 50 | 29.1 |

| ≥1.59 | 122 | 70.9 |

| MC (109/L) | ||

| <0.46 | 77 | 44.8 |

| ≥0.46 | 95 | 55.2 |

| NC (109/L) | ||

| <2.85 | 47 | 27.3 |

| ≥2.85 | 125 | 72.7 |

| LMR | ||

| <3.40 | 47 | 27.3 |

| ≥3.40 | 125 | 72.7 |

| PLR | ||

| <177.40 | 149 | 86.6 |

| ≥177.40 | 23 | 13.4 |

| NLR | ||

| <2.85 | 131 | 28.5 |

| ≥2.85 | 41 | 71.5 |

| CRP (mg/L) | ||

| <3.26 | 128 | 74.4 |

| ≥3.26 | 44 | 25.6 |

| ALB (g/L) | ||

| <46.60 | 136 | 79.1 |

| ≥46.60 | 36 | 21.9 |

| CAR | ||

| <90.20 | 146 | 84.9 |

| ≥90.20 | 26 | 15.1 |

| SII | ||

| <20.40 | 153 | 89.0 |

| ≥20.40 | 19 | 11.0 |

| SIS | ||

| 0 | 52 | 30.3 |

| 1 | 100 | 58.1 |

| 2 | 20 | 11.6 |

| PNI | ||

| <47.70 | 21 | 12.2 |

| ≥47.70 | 151 | 87.8 |

Abbreviations: T stage, tumor stage; N stage, lymph node stage; TNM stage, tumor node metastasis stage; WBC, white blood cell; RBC, red blood cell; HGB, hemoglobin; PLT, platelet; LC, lymphocyte count; MC, monocyte count; NC, neutrophil count; LMR, lymphocyte/monocyte ratio; PLR, platelet/lymphocyte ratio; NLR, neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio; CRP, C-reactive protein; ALB, albumin; CAR, C-reactive protein/albumin ratio; SII, immune-inflammation score; SIS, systemic inflammation score; PNI, prognostic nutritional index.

TNM stage was classified according to the AJCC eighth TNM stage system.

The tumor maximum diameter.

The optimal cut-off values for all variables were calculated by X-tile and were showed in follows age (69 years), tumor size (4.20 cm), WBC (4.95 × 109/L), RBC (3.91 × 109/L), HGB (152.00 g/L), PLT (196.00 × 109/L), LC (1.59 × 109/L), MC (0.46 × 109/L), NC (2.85 × 109/L), LMR (3.40), PLR (177.40), NLR (2.85), CRP (3.26 mg/L), ALB (46.60 g/L), CAR (90.20), SII (20.40), PNI (47.70).

Univariate Analysis and Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazards Regression Analysis of OS

Univariate analysis showed that age (P = .049), T stage (P = .005), N stage (P = .002), TNM stage (P < .001), tumor size (P = .006), WBC (P = .024), RBC (P = .019), and PLT (P = .035), LC (P = .029), LMR (P = .041), PLR (P = .016) were associated with OS of TSCC patients. Subsequently, the prognostic factors significantly associated to OS in univariate analysis were brought into in the multivariate Cox proportional risk regression analysis. The results showed age (P = .029, HR = 2.549; 95% CI: 1.103-5.888), TNM stage (P < .001, HR = 4.090; 95% CI: 2.018-8.293), RBC (P = .047, HR = 0.453; 95% CI: 0.207-0.991), PLT (P = .002, HR = 0.276; 95% CI: 0.276-0.611), and PLR (P = .029, HR = 2.874;95% CI: 1.113-7.420) remained significant independent prognostic factors for OS (Table 2). According to multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, the forest plot further demonstrated that age, TNM stage, RBC, PLT, and PLR were significantly associated with OS of TSCC patients (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Univariate and Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazards Regression Analysis for OS.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | Reference | |||||

| Female | 0.925 | 0.479-1.786 | .817 | |||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <69 | Reference | |||||

| ≥69 | 2.206 | 1.003-4.852 | .049 | 2.549 | 1.103-5.888 | .029 |

| Smoking behavior | ||||||

| Yes | Reference | |||||

| No | 0.816 | 0.424-1.570 | .542 | |||

| Drinking behavior | ||||||

| Yes | Reference | |||||

| No | 0.553 | 0.271-1.130 | .104 | |||

| T stage | ||||||

| T1 + T2 | Reference | |||||

| T3 + T4 | 2.821 | 1.358-5.860 | .005 | |||

| N stage | ||||||

| N0 | Reference | |||||

| N1 + 2 + 3 | 2.877 | 1.480-5.590 | .002 | |||

| TNM stage a | ||||||

| I + II | Reference | |||||

| III-IV | 4.452 | 2.272-8.721 | .000 | 4.090 | 2.018-8.293 | .000 |

| Size (cm) b | ||||||

| <4.20 | Reference | |||||

| ≥4.20 | 2.909 | 1.364-2.602 | .006 | |||

| WBC (109/L) | ||||||

| <4.95 | Reference | |||||

| ≥4.95 | 0.428 | 0.205-0.893 | .024 | |||

| RBC (109/L) | ||||||

| <3.96 | Reference | |||||

| ≥3.96 | 2.475 | 1.162-5.270 | .019 | 0.453 | 0.207-0.991 | .047 |

| HGB (g/L) | ||||||

| <152.00 | Reference | |||||

| ≥152.00 | 1.713 | 0.748-3.919 | .203 | |||

| PLT (109/L) | ||||||

| <196.00 | Reference | |||||

| ≥196.00 | 0.488 | 0.251-0.949 | .035 | 0.276 | 0.276-0.611 | .002 |

| LC (109/L) | ||||||

| <1.59 | Reference | |||||

| ≥1.59 | 0.480 | 0.249-0.929 | .029 | |||

| MC (109/L) | ||||||

| <0.46 | Reference | |||||

| ≥0.46 | 0.526 | 0.269-1.029 | .061 | |||

| NC (109/L) | ||||||

| <2.85 | Reference | |||||

| ≥2.85 | 0.758 | 0.379-1.515 | .432 | |||

| LMR | ||||||

| <3.40 | Reference | |||||

| ≥3.40 | 0.501 | 0.258-0.973 | .041 | |||

| PLR | ||||||

| <177.40 | Reference | |||||

| ≥177.40 | 2.644 | 1.201-5.823 | .016 | 2.874 | 1.113-7.420 | .029 |

| NLR | ||||||

| <2.85 | Reference | |||||

| ≥2.85 | 1.729 | 0.864-3.461 | .122 | |||

| CRP (mg/L) | ||||||

| <3.26 | Reference | |||||

| ≥3.26 | 0.590 | 0.288-1.209 | .150 | |||

| ALB (g/L) | ||||||

| <46.60 | Reference | |||||

| ≥46.60 | 1.996 | 0.977-4.077 | .058 | |||

| CAR | ||||||

| <90.20 | Reference | |||||

| ≥90.20 | 1.832 | 0.833-4.028 | .132 | |||

| SII | ||||||

| <20.40 | Reference | |||||

| ≥20.40 | 1.799 | 0.738-4.290 | .199 | |||

| SIS | ||||||

| 0 | Reference | |||||

| 1 | 1.033 | 0.493-2.162 | .932 | |||

| 2 | 0.539 | 0.118-2.460 | .425 | |||

| PNI | ||||||

| <47.70 | Reference | |||||

| ≥47.70 | 0.496 | 0.205-1.201 | .120 | |||

Abbreviations: T stage, tumor stage; N stage, lymph node stage; TNM stage, tumor node metastasis stage; WBC, white blood cell; RBC, red blood cell; HGB, hemoglobin; PLT, platelet; LC, lymphocyte count; MC, monocyte count; NC, neutrophil count; LMR, lymphocyte/monocyte ratio; PLR, platelet/lymphocyte ratio; NLR, neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio; CRP, C-reactive protein; ALB, albumin; CAR, C-reactive protein/albumin ratio; SII, immune-inflammation score; SIS, systemic inflammation score; PNI, prognostic nutritional index.

TNM stage was classified according to the AJCC eighth TNM stage system.

The tumor maximum diameter.

Figure 1.

Forest plot revealed the hazard ratio and 95% confidence interval for OS based on the Cox proportional hazards regression analysis in TSCC patients.

Abbreviations: RBC, red blood cell; PLT, platelet; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; TNM, tumor node metastasis stage; OS, overall survival; TSCC, tongue squamous cell carcinoma.

Nomogram for Prediction of OS

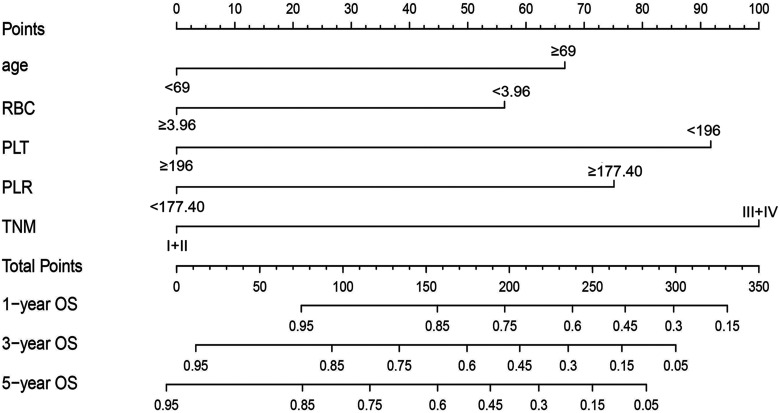

In this study, in order to predict OS, the independent prognostic factors of age, TNM stage, RBC, PLT, and PLR were used to establish a nomogram model for OS probability prediction (Figure 2). A weighted total score calculated from these variables was used to estimate 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS for TSCC patients with surgical treatment (Figure 2). The result showed a close relationship between age, TNM stage, RBC, PLT, and PLR for OS with a 5-year OS less than 15% (Figure 2). In these variables, each factor was assigned a number of risk points, which was obtained by drawing a straight line directly upward to the “points” axis from the corresponding value of the prognostic factor. The process was repeated for each prognostic factor. The points obtained for each covariate were summarized, and “Total Point” axis was located from the sum of the risk points. Finally, a vertical line was drawn directly down to the axis that determined the patient's probability of OS at 1-, 3-, and 5-year. In addition, the calibration plots for the overall survival probability of 1-, 3-, and 5-year revealed a good match between the prediction of OS in the nomogram model and the actual observation (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Nomogram model based on age, RBC, PLT, PLR, and TNM stage in the prediction of 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS probability in TSCC patients. The total points projected on the bottom scales show the probability of 1-, 3-, and 5-y survival.

Abbreviations: RBC, red blood cell; PLT, platelet; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; TNM, tumor node metastasis stage; OS, overall survival; TSCC, tongue squamous cell carcinoma.

Figure 3.

The calibration plot (a)–(c) are used to estimate OS probability for the nomograms at 1-, 3-, 5-year survival rates.

Abbreviations: RBC: red blood cell, PLT, platelet; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; TNM, tumor node metastasis stage; OS, overall survival.

Assessment of Performance Between Prognostic Model and Conventional Staging Systems

The assessment of the predictive accuracy and the discrimination performance between the prognostic model and traditional staging systems were done using C-index and decision curve analysis. As shown in Table 3, the C-index for the prognostic model was 0.794 (95% CI: 0.729-0.860), which was higher than that of TNM staging 0.685 (95% CI: 0.605-0.765, P = .040). The results of time-dependent C-index curve analysis for the predictive accuracy of the prognostic model and TNM stage showed that the model was higher than that of the TNM stage alone (Figure 4). In addition, the analysis of the decision curves for 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS (Figure 5) showed that the model seemed to have higher overall benefit than the traditional TNM stage systems alone in the majority of the range of threshold probabilities. Taken together, these results indicate the prognostic model had a better net benefit and predictive accuracy to predict survival outcomes when compared to the traditional TNM stage systems.

Table 3.

The C-Index of RBC, PLT, PLR, TNM Stage and Prognostic Model for Prediction of OS in TSCC.

| Factors | C-index (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.559 (0.484-0.634) | |

| RBC | 0.570 (0.498-0.641) | |

| PLT | 0.579 (0.493-0.664) | |

| PLR | 0.556 (0.489-0.623) | |

| TNM stage | 0.685 (0.605-0.765) | |

| Prognostic model | 0.794 (0.729-0.860) | |

| Age vs TNM stage | .013 | |

| RBC vs TNM stage | .012 | |

| PLT vs TNM stage | .019 | |

| PLR vs TNM stage | .005 | |

| Prognostic model vs TNM stage | .040 |

Abbreviations: C-index, concordance index; CI, confidence interval; RBC, red blood cell; PLT, platelet; PLR, platelet/lymphocyte ratio; TNM stage, tumor node metastasis stage; TSCC, tongue squamous cell carcinoma; OS, overall survival.

P-values are calculated based on normal approximation using function rcorrp.cens in Hmisc package.

Figure 4.

Comparison of predictive accuracy between prognostic model, RBC, PLT, PLR, age, and TNM stage using time-dependent C-index curve analysis.

Abbreviations: RBC, red blood cell; PLT, platelet; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; TNM, tumor node metastasis stage.

Figure 5.

Decision curve analysis the predictive accuracy of model in TSCC patients. The decision curve of 1- (a), 3- (b), and 5- (c) year OS. The y-axis represents the net benefit, which is calculated by summing the benefits (true positive results) and subtracting the harms (false positive results). The horizontal line represents the assumption that no deaths happen.

Abbreviations: OS, overall survival; TSCC, tongue squamous cell carcinoma.

Risk Stratification Based on the Nomogram Risk Score

Based on optimum cutoff values of the risk score determined by the X-tile program, we subdivided patients into low- and high-risk subgroups. Subsequently, the stratified subgroups were analyzed by Kaplan–Meier survival analysis to assess their OS, and the result indicated that the high-risk group had shorter OS than the low-risk group (23% vs 49%, P < .0001), and the median OS of patients was less than 8 years (Figure 6). This stratification demonstrated that the prognostic model could effectively separate those patients into the 2 risk subgroups with significant differences in OS.

Figure 6.

Kaplan–Meier analyses of OS according to the prognostic nomogram model risk score in subgroups of TSCC patients.

Abbreviations: OS, overall survival; TSCC, tongue squamous cell carcinoma.

Discussion

In recent years, with the characteristic of increasing incidence and the poor prognosis, an increasing number of studies have focused on TSCC. Clinically, it is a dilemma to identify those cases of TSCC who will suffer an aggressive behavior with a poor prognosis and would benefit from surgical resection and/or neck dissection. Therefore, there is an urgent need to find an effective and low-cost method to predict outcomes and help guide clinical treatments. In the current study, we successfully established a prognostic model to predict OS for TSCC by combining clinicopathological features and pretreatment inflammation- and nutrition-related indicators based on the survival analysis approach, including age, TNM stage, RBC, PLT, and PLR. Our model showed better prognostic accuracy and discriminative ability in surgical patients with TSCC when compared with the conventional TNM staging system. The prognostic model successfully divided those patients into high- and low-risk subgroups with significant differences for OS.

Cancer patients frequently present with anemia that may result from the tumor progression, which includes direct and indirect effects of the tumor that lead to decreased red cell production or increased red cell destruction. 34 In tongue cancer, preoperative RBC level was found to be associated to tumor size and histopathological grading.20,35 RBC is an important nutrition-related prognostic factor for cancers and decreased RBC has been found to associate with poor survival in breast cancer and colorectal cancer.36,37 In the present study, we also revealed that a reduced preoperative RBC level was an independent prognostic factor in TSCC.

Chronic inflammation has been identified as an accelerator in cancer development through cytotoxic reaction, abnormal tissue repair, cell proliferative responses, invasion, and metastasis.38,39 Platelets have been considered to mediate activation of coagulation and fibrinolytic systems. Tumor-induced platelets activation and coagulation not only increase the risk of thrombosis, but also are conductive to tumor progression by promoting critical processes such as angiogenesis and metastasis. 21 In addition, as one of the inflammation factors, platelets regulate the immune system to attune cancer-associated inflammation milieu by changing the activation status of the endothelium and by recruiting leukocytes to primary and metastatic tumor sites. 40 Therefore, some researchers support the point of view that the role of platelet-leukocyte interactions may play an important role in the development and progression of cancer. 41 PLR, as another inflammation-associated marker, was included in our model. According to the literatures, an elevated PLR has been identified as a prognostic biomarker in various malignancies, including gastric cancer, 28 tongue cancer, 42 lung cancer, 31 colorectal cancer, 43 and other solid cancers. 29 These studies showed that an increased PLR was correlated to a poor OS or DFS, which was also confirmed in our study. We found that a high PLR could serve as an independent prognostic factor to predict OS in surgical patients with TSCC. On the other hand, it is a fact that PLT or PLR level is easily affected by medication, chemotherapy, and acute inflammation. In the current study, the PLT or PLR level was all evaluated at baseline, and thus could reduce the impact of the relevant aspects. We believed that PLT and PLR might be associated with the clinical outcomes of tongue cancer patients, but the clinical application of such markers for long-term outcome of TSCC patients still needs to be verified repeatedly.

Most studies reported a single blood-based indicator served as an independent prognostic factor for survival prediction of patients with tongue cancer, such as CRP, 44 NLR,45,46 and LMR. 47 However, the prognostic value of the detection of a single marker seems to be limited for tongue cancer. Ozturk et al 48 found that multiple blood-based indicators including NLR, PLR, and N × PLR improved prognostic efficacy, which were related to local recurrence and poor survival of patients with early-stage tongue cancer. On the other hand, recent publications indicated that nomogram based on patients’ demographics and clinicopathological parameters, such as age, gender, and depth of tumor invasion, might also have predictive ability for the prognosis of TSCC patients.49–52 In this study, to increase the prognostic accuracy, many potential blood-based indicators and patients’ demographics and clinicopathological features were included and evaluated together to establish a multivariate prognostic nomogram model for OS prediction. Moreover, we found that our prognostic nomogram based on integrating age, TNM stage, RBC, PLT, and PLR was more accurate in predicting OS than that of the conventional TNM stage system alone. Similarly, Lu et al 53 also established a nomogram model based on the combination of patients’ clinicopathological parameters with an inflammation-related biomarker to predicting OS for patients with TSCC. But the indicators they included in the nomogram were age, lymph node density, and SII, which were different from ours. Furthermore, in the study from Lu et al SII serves as a significant independent prognostic factor for OS and DFS of patients with TSCC. This result was inconsistent with our findings. We noted that SII was not a significant prognostic factor for OS in the current study (Table 2). This may be due to the different sources of patients included. Although their data were validated in an independent cohort, the total number of patients they included was similar to ours (170 cases vs 172 cases). Thus, whether SII is a marker for predicting the survival of patients with TSCC needs to be verified in more extensive studies.

In general, our model might be used as a potential tool for clinicians to select and plan treatment strategies for TSCC patients, and our model offers a convenient and low-cost method to predict outcomes for surgical patients with TSCC, as the blood-based indicators are easy to obtain from routine admission laboratory tests. However, some limitations of our study should be taken into account. Firstly, this is a retrospective study, and thus, the retrospective character of this study cannot completely exclude all potential biases. Secondly, patients’ data used to identify the prognostic factors were obtained from a single cancer center. In the future, it is necessary to obtain a large-scale sample from other research institutions to conduct multicenter validation of the results. Moreover, the increased value for outcome prediction, even if confirmed, may not be of clinical benefit. Because the discovery, validation, and clinical application of a prognostic model is a complex and long process. Nonetheless, our study may have an enlightening effect on exploiting serum inflammation- and nutrition-related markers for prognostic prediction of TSCC patients in the future. Although the above-mentioned shortcomings existed, our prognostic model might serve as a useful tool for clinicians to estimate individualized outcomes and help make treatment strategies for TSCC patients.

Conclusions

In summary, we established a multiparametric prognostic model derived from clinicopathological features and pretreatment blood-based inflammation- and nutrition-related indicators that presented favorable performance when compared to the traditional TNM stage for OS prediction in surgical patients with TSCC. Therefore, it is appealing to imagine that in the case of TSCC, if further validation in multicenter and large-scale samples could be completed, this convenient, low-cost, and simple tool may help clinicians in consulting patients and estimating prognosis for TSCC patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the reviewers for their critical comments.

Abbreviations

- AJCC

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- C-index

the concordance index

- CI

confidence intervals

- DFS

disease-free survival

- EEC

endometrioid endometrial carcinoma

- HR

hazard ratio

- HGB

hemoglobin

- LC

lymphocyte count

- LMR

lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio

- MC

monocyte count

- NC

neutrophil count

- NLR

neutrophil-to-lymphocyte

- OS

overall survival

- OSCC

oral squamous cell carcinoma

- PLT

platelet

- PLR

platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio

- RBC

red blood cell

- TSCC

tongue squamous cell carcinoma

- WBC

white blood cell count.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: LFW designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript; HPG designed the study, provided patient samples and clinical data, and wrote the manuscript; XCH analyzed and interpreted the clinical data; YWL, YL, and TYD collected patient samples and clinical data, and analyzed the data; CTL and LYC collected patient samples and clinical data; YHP, YWX, and HPG conceptualized and designed the study, supervised the project, and revised the paper. All authors have approved the final version and agreed to publish the manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Hospital Ethics Committee in the Cancer Hospital of Shantou University Medical College (Guangdong, Shantou, China, number: 2020054).

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by funding from the Natural Science Foundation of China (81972801), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2019A1515011873), the Guangdong Esophageal Cancer Institute Science and Technology Program (Q201906), the Medical Project of Science and Technology Planning of Shantou (200605115266724 and 190413105262902); and the 2020 Li Ka Shing Foundation Cross-Disciplinary Research Grant (2020LKSFG01B).

ORCID iDs: Ling-Yu Chu https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4682-0931

Yi-Wei Xu https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8670-592X

References

- 1.Warnakulasuriya S. Global epidemiology of oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2009;45(4–5):309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7-34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):115-132. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang LW, Li J, Cong X, et al. Incidence and mortality trends in oral and oropharyngeal cancers in China, 2005–2013. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018;57:120-126. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2018.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Upadhyay P, Gardi N, Desai S, et al. Genomic characterization of tobacco/nut chewing HPV-negative early stage tongue tumors identify MMP10 as a candidate to predict metastases. Oral Oncol. 2017;73:56-64. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2017.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim SC, Zhang S, Ishii G, et al. Predictive markers for late cervical metastasis in stage I and II invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue. Clin. Cancer Res: Official J Am Association for Cancer Res. 2004;10(1 Pt 1):166-172. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0533-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ebrahimi A, Gil Z, Amit M, et al. Comparison of the American Joint Committee on Cancer N1 versus N2a nodal categories for predicting survival and recurrence in patients with oral cancer: time to acknowledge an arbitrary distinction and modify the system. Head Neck. 2016;38(1):135-139. doi: 10.1002/hed.23871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weitzman SA, Gordon LI. Inflammation and cancer: role of phagocyte-generated oxidants in carcinogenesis. Blood. 1990;76(4):655-663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tong Y, Xie X, Mao X, Lei H, Chen Y, Sun P. Low Red blood cell count as an early indicator for myometrial invasion in women with endometrioid endometrial carcinoma with metabolic syndrome. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:10849-10859. doi: 10.2147/cmar.S271078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee YJ, Lee HR, Nam CM, Hwang UK, Jee SH. White blood cell count and the risk of colon cancer. Yonsei Med J. 2006;47(5):646-656. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2006.47.5.646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.An X, Ding PR, Wang FH, Jiang WQ, Li YH. Elevated neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts poor prognosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Tumour Biol: J Int Soc Oncodevelopmental Biol Med. 2011;32(2):317-324. doi: 10.1007/s13277-010-0124-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donskov F. Immunomonitoring and prognostic relevance of neutrophils in clinical trials. Semin Cancer Biol. 2013;23(3):200-207. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He JR, Shen GP, Ren ZF, et al. Pretreatment levels of peripheral neutrophils and lymphocytes as independent prognostic factors in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck. 2012;34(12):1769-1776. doi: 10.1002/hed.22008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trellakis S, Bruderek K, Dumitru CA, et al. Polymorphonuclear granulocytes in human head and neck cancer: enhanced inflammatory activity, modulation by cancer cells and expansion in advanced disease. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(9):2183-2193. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsai YD, Wang CP, Chen CY, et al. Pretreatment circulating monocyte count associated with poor prognosis in patients with oral cavity cancer. Head Neck. 2014;36(7):947-953. doi: 10.1002/hed.23400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark EJ, Connor S, Taylor MA, Madhavan KK, Garden OJ, Parks RW. Preoperative lymphocyte count as a prognostic factor in resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. HPB (Oxford). 2007;9(6):456-460. doi: 10.1080/13651820701774891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitayama J, Yasuda K, Kawai K, Sunami E, Nagawa H. Circulating lymphocyte is an important determinant of the effectiveness of preoperative radiotherapy in advanced rectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang B, Jiang XW, Tian DL, Zhou N, Geng W. Combination of haemoglobin and prognostic nutritional Index predicts the prognosis of postoperative radiotherapy for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:8589-8597. doi: 10.2147/cmar.S266821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abu-Zaid A, Alomar O, Abuzaid M, Baradwan S, Salem H, Al-Badawi IA. Preoperative anemia predicts poor prognosis in patients with endometrial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;258:382-390. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2021.01.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhattathiri VN. Relation of erythrocyte and iron indices to oral cancer growth. Radiother Oncol. 2001;59(2):221-226. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(01)00326-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loreto MF, De Martinis M, Corsi MP, Modesti M, Ginaldi L. Coagulation and cancer: implications for diagnosis and management. Pathol Oncol Res. 2000;6(4):301-312. doi: 10.1007/bf03187336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lip GY, Chin BS, Blann AD. Cancer and the prothrombotic state. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3(1):27-34. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(01)00619-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Honn KV, Tang DG, Chen YQ. Platelets and cancer metastasis: more than an epiphenomenon. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1992;18(4):392-415. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1002578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou Q, Huang F, He Z, Zuo MZ. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of platelet count in patients with ovarian cancer. Climacteric. 2018;21(1):60-68. doi: 10.1080/13697137.2017.1406911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Russo A, Russano M, Franchina T, et al. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), and outcomes with nivolumab in pretreated non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a large retrospective multicenter study. Adv Ther. 2020;37(3):1145-1155. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01229-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fang T, Wang Y, Yin X, et al. Diagnostic sensitivity of NLR and PLR in early diagnosis of gastric cancer. J Immunol Res. 2020;2020:9146042. doi: 10.1155/2020/9146042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu C, Bai Y, Li J, et al. Prognostic value of systemic inflammatory factors NLR, LMR, PLR and LDH in penile cancer. BMC Urol. 2020;20(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s12894-020-00628-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang X, Zhao W, Yu Y, et al. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of platelet-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) in gastric cancer: an updated meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2020;18(1):191. doi: 10.1186/s12957-020-01952-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Templeton AJ, Ace O, McNamara MG, et al. Prognostic role of platelet to lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(7):1204-1212. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-14-0146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li B, Zhou P, Liu Y, et al. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in advanced cancer: review and meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2018;483:48-56. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2018.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diem S, Schmid S, Krapf M, et al. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) as prognostic markers in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with nivolumab. Lung Cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2017;111:176-181. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deng TB, Zhang J, Zhou YZ, Li WM. The prognostic value of C-reactive protein to albumin ratio in patients with lung cancer. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(50):e13505. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000013505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin JX, Lin JP, Xie JW, et al. Prognostic importance of the preoperative modified systemic inflammation score for patients with gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2019;22(2):403-412. doi: 10.1007/s10120-018-0854-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ibrahim UA, Yusuf AA, Ahmed SG. The pathophysiologic basis of anaemia in patients with malignant diseases. Gulf J Oncolog. 2016;1(22):80-89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anees Ahmed RA, Ganvir SM, Hazarey VK. Relation of erythrocyte indices and serum iron level with clinical and histological progression of oral squamous cell carcinoma in central India. J Investig Clin Dent. 2014;5(1):65-71. doi: 10.1111/jicd.12021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raza U, Sheikh A, Jamali SN, Turab M, Zaidi SA, Jawaid H. Post-treatment hematological variations and the role of hemoglobin as a predictor of disease-free survival in stage 2 breast cancer patients. Cureus. 2020;12(3):e7259. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Y, Wu H, Xing C, et al. Prognostic evaluation of colorectal cancer using three new comprehensive indexes related to infection, anemia and coagulation derived from peripheral blood. J Cancer. 2020;11(13):3834-3845. doi: 10.7150/jca.42409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Philip M, Rowley DA, Schreiber H. Inflammation as a tumor promoter in cancer induction. Semin Cancer Biol. 2004;14(6):433-439. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2004.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elinav E, Nowarski R, Thaiss CA, Hu B, Jin C, Flavell RA. Inflammation-induced cancer: crosstalk between tumours, immune cells and microorganisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(11):759-771. doi: 10.1038/nrc3611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olsson AK, Cedervall J. The pro-inflammatory role of platelets in cancer. Platelets. 2018;29(6):569-573. doi: 10.1080/09537104.2018.1453059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stoiber D, Assinger A. Platelet-Leukocyte interplay in cancer development and progression. Cells. 2020;9(4):855. doi: 10.3390/cells9040855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ong HS, Gokavarapu S, Wang LZ, Tian Z, Zhang CP. Low pretreatment lymphocyte-monocyte ratio and high platelet-lymphocyte ratio indicate poor cancer outcome in early tongue cancer. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;75(8):1762-1774. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2016.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peng HX, Lin K, He BS, et al. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio could be a promising prognostic biomarker for survival of colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. FEBS Open Bio. 2016;6(7):742-750. doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.12083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Graupp M, Schaffer K, Wolf A, et al. C-reactive protein is an independent prognostic marker in patients with tongue carcinoma – A retrospective study. Clin Otolaryngol. 2018;43(4):1050‐1056. doi: 10.1111/coa.13102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu CN, Chuang HC, Lin YT, Fang FM, Li SH, Chien CY. Prognosis of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in clinical early-stage tongue (cT1/T2N0) cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:3917-3924. doi: 10.2147/ott.S140800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abbate V, Dell’Aversana Orabona G, Salzano G, et al. Pre-treatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a predictor for occult cervical metastasis in early stage (T1-T2 cN0) squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue. Surg Oncol. 2018;27(3):503-507. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2018.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Furukawa K, Kawasaki G, Naruse T, Umeda M. Prognostic significance of pretreatment lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in patients with tongue cancer. Anticancer Res. 2019;39(1):405-412. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ozturk K, Akyildiz NS, Uslu M, Gode S, Uluoz U. The effect of preoperative neutrophil, platelet and lymphocyte counts on local recurrence and survival in early-stage tongue cancer. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273(12):4425-4429. doi: 10.1007/s00405-016-4098-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jiang Q, Tang A, Long S, et al. Development and validation of a nomogram to predict the risk of occult cervical lymph node metastases in cN0 squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;57(10):1092-1097. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2019.09.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li Y, Zhao Z, Liu X, et al. Nomograms to estimate long-term overall survival and tongue cancer-specific survival of patients with tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2017;6(5):1002-1013. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mascitti M, Zhurakivska K, Togni L, et al. Addition of the tumour-stroma ratio to the 8th edition American joint committee on cancer staging system improves survival prediction for patients with oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Histopathology. 2020;77(5):810-822. doi: 10.1111/his.14202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chang B, He W, Ouyang H, et al. A prognostic nomogram incorporating depth of tumor invasion to predict long-term overall survival for tongue squamous cell carcinoma with R0 resection. J Cancer. 2018;9(12):2107-2115. doi: 10.7150/jca.24530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lu Z, Yan W, Liang J, et al. Nomogram based on systemic immune-inflammation Index to predict survival of tongue cancer patients Who underwent cervical dissection. Front Oncol. 2020;10:341. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]