Abstract

Background

Gas gangrene is a rapidly progressive and severe disease that results from bacterial infection, usually as the result of an injury; it has a high incidence of amputation and a poor prognosis. It requires early diagnosis and comprehensive treatments, which may involve immediate wound debridement, antibiotic treatment, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, Chinese herbal medicine, systemic support, and other interventions. The efficacy and safety of many of the available therapies have not been confirmed.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of potential interventions in the treatment of gas gangrene compared with alternative interventions or no interventions.

Search methods

In March 2015 we searched: The Cochrane Wounds Group Specialized Register, The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library), Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, EBSCO CINAHL, Science Citation Index, the China Biological Medicine Database (CBM‐disc), the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), and the Chinese scientific periodical database of VIP INFORMATION (VIP) for relevant trials. We also searched reference lists of all identified trials and relevant reviews and four trials registries for eligible research. There were no restrictions with respect to language, date of publication or study setting.

Selection criteria

We selected randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs that compared one treatment for gas gangrene with another treatment, or with no treatment.

Data collection and analysis

Independently, two review authors selected potentially eligible studies by reviewing their titles, abstracts and full‐texts. The two review authors extracted data using a pre‐designed extraction form and assessed the risk of bias of each included study. Any disagreement in this process was solved by the third reviewer via consensus. We could not perform a meta‐analysis due to the small number of studies included in the review and the substantial clinical heterogeneity between them, so we produced a narrative review instead.

Main results

We included two RCTs with a total of 90 participants. Both RCTs assessed the effect of interventions on the 'cure rate' of gas gangrene; 'cure rate' was defined differently in each study, and differently to the way we defined it in this review.

One trial compared the addition of Chinese herbs to standard treatment (debridement and antibiotic treatment; 26 participants) against standard treatment alone (20 participants). At the end of the trial the estimated risk ratio (RR) of 3.08 (95% confidence intervals (CI) 1.00 to 9.46) favoured Chinese herbs. The other trial compared standard treatment (debridement and antibiotic treatment) plus topical hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT; 21 participants) with standard treatment plus systemic HBOT (23 participants). There was no evidence of difference between the two groups; RR of 1.10 (95% CI 0.25 to 4.84). For both comparisons the GRADE assessment was very low quality evidence due to risk of bias and imprecision so further trials are needed to confirm these results.

Neither trial reported on this review's primary outcomes of quality of life, and amputation and death due to gas gangrene, or on adverse events. Trials that addressed other therapies such as immediate debridement, antibiotic treatment, systemic support, and other possible treatments were not available.

Authors' conclusions

Re‐analysis of the cure rate based on the definition used in our review did not show beneficial effects of additional use of Chinese herbs or topical HBOT on treating gas gangrene. The absence of robust evidence meant we could not determine which interventions are safe and effective for treating gas gangrene. Further rigorous RCTs with appropriate randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding, which focus on cornerstone treatments and the most important clinical outcomes, are required to provide useful evidence in this area.

Plain language summary

Interventions for treating gas gangrene

Background

Gas gangrene is a serious and intense infection that may lead to amputation of a limb and even death; it is a medical emergency. It usually occurs when an injury caused by trauma or accident becomes infected, or as the result of a postoperative infection, although it can also arise without obvious injury. Gas gangrene is caused by bacteria (especially Clostridium species), which can live and grow in wounds where there is a low concentration of oxygen. The bacteria release toxins that cause substantial damage to the tissue around the wound, and can cause fatal deterioration of the whole body. Successful management of the infection requires early diagnosis and effective treatments.

A variety of treatments are used to treat gas gangrene. The main ones are debridement (removal of dead and foreign matter, and collections of blood, from the wound) and antibiotics to kill the bacteria. Other treatments that can be added to these essential treatments include hyperbaric oxygen therapy (in which oxygen is supplied at a high pressure), and Chinese herbal medicine, as well as other interventions that address the symptoms of gas gangrene.

Review question

We investigated which interventions are effective and safe for the treatment of gas gangrene.

What we found

In March 2015 we searched a wide range of medical databases and registers of medical trials to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs; these produce the most reliable results) that compared one treatment of gas gangrene with another treatment, or with no treatment. We identified two relevant RCTs with a total of 90 participants with gas gangrene.

One RCT (46 participants) compared standard treatment plus treatment with Chinese herbs to standard treatment alone (debridement and antibiotics). This RCT showed a higher cure rate in the group of participants treated with the Chinese herbs than in the group that had standard treatment alone (21/26 versus 9/20 participants respectively). The definition of 'cure' used in the trial was the proportion of participants who were cured or improved. When we restricted the definition of 'cure' to those participants who were cured (and left out those who were 'improved'), the difference in cure rate between the Chinese herb group (12/26 participants) and the standard treatment group (3/20 participants) was slightly smaller.

The other RCT (44 participants) compared standard treatment plus topical hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT; applied at the wound surface) against standard treatment plus systemic HBOT that was given to the whole body. The cure rate was higher in the group of participants who had topical HBOT than in the group that had systemic HBOT (19/21 versus 11/23 participants respectively). The definition of 'cure' used in the trial was the proportion of participants who were cured or significantly improved. When we restricted the definition of 'cure' to those participants who were cured (and left out those who were 'significantly improved'), there was little difference between the topical HBOT group (3/21 participants) and the systemic HBOT group (3/23 participants).

The quality of the evidence for both comparisons on the outcome of cure rate was very low. Neither trial reported on quality of life, amputation or death attributable to gas gangrene or harmful effects of treatment. We did not find trials that investigated any other treatments for gas gangrene.

Conclusions

The benefits and harms of different treatments for gas gangrene remain unclear as the available trials do not provide high quality evidence, due to low sample numbers and a number of problems with the way the trials were conducted that can introduce bias to the results. Further trials or observational studies with appropriate study design, that focus on the main treatments for gas gangrene and that report on quality of life, amputation and death due to gas gangrene, and harms that may be caused by treatment are needed.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Gas gangrene

Gas gangrene is an acute, severe, painful infection in which the muscles and subcutaneous tissues become filled with gas and serosanguineous exudate (i.e. blood serum that appears pink because it contains a small number of red blood cells; see Glossary Appendix 1; Anderson 2007). It is the result of infection by specific bacteria that invade muscle tissue, and produce exotoxins (potent toxins secreted by the micro‐organism; Appendix 1), particularly one called 'alpha toxin' ‐ a membrane‐disrupting toxin with phospholipase C activity ‐ that causes tissue necrosis (death; Appendix 1) and gas production (Stevens 1988). Gas gangrene is also called 'clostridial myonecrosis' because Clostridium species are the most common cause of the infection.

Pathogens and etiology

Gas gangrene can be grouped into clostridial and non‐clostridial forms, depending on the type of bacteria causing the infection.

Clostridium species are Gram‐positive, spore‐forming, anaerobic bacilli commonly found in soil, and dust, that are also found in the gastrointestinal tract, vagina and on the skin of humans (Xiao 2008). The most common subtype of Clostridium that causes clostridial gas gangrene isClostridium perfringens, previously known as C welchii. Other Clostridium species, including C novyi, C septicum, C histolyticum, C bifermentans and C fallax, are also responsible for the infection (De 2003).

Non‐clostridial species of bacteria are able to produce gas and have also been implicated in causing gas gangrene. These non‐clostridial organisms are mainly aerobic and Gram‐negative, and include Escherichia coli, Proteus species, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterococcus species, and Bacteroides species (Bessman 1975; Hart 1983; De 2003).

In most cases of gas gangrene, pathogens invade the tissues through trauma wounds, while the remainder arise spontaneously or from surgical procedures (Hart 1990). Spontaneous gas gangrene is often caused by the haematogenous spread (i.e. through the blood; Appendix 1) of C septicum, which is relatively aerotolerant (tolerates oxygen), and thus more capable of initiating infection in the absence of obvious damage to tissues. The portal of entry to the blood stream is believed to be mucosal ulceration, or, in patients with colon disease, perforation of the gastrointestinal tract (Leung 1981; Stevens 1990). The usual manifestation is a necrotising infection in an extremity or in the abdominal wall, accompanied by hypotension (low blood pressure) and renal failure (Gerding 2011). When tissue is damaged in people who have undergone trauma or had surgery, the vascular supply may be compromised, which leads to a lowering of the oxygen tension within the tissues, thus providing circumstances in which micro‐organisms multiply readily. Under conditions of low oxygen these organisms produce and release a variety of exotoxins, including lecithinase, collagenase, hyaluronidase, fibrinolysin and haemagglutinin, which can lead to local and systemic (whole body) changes in the affected patients. Alpha‐toxin, a C‐lecithinase, which is a major lethal toxin in gas gangrene, leads to necrosis and haemolysis (breakdown of blood) that can subsequently cause anaemia, jaundice and even renal failure. Other exotoxins also play an important role in destroying and liquefying healthy tissue, and in the rapid spread of infection (Hart 1990).

Epidemiology

Historically, gas gangrene has been a complication of battlefield injuries. The incidence associated with war wounds was 5% in World War I, 0.7% in World War II, 0.2% in the Korean War, and 0.02% in the Vietnam War (Bartlett 2007). These days battlefield gas gangrene is not a major cause for concern (Titball 2005), but in civilian practice, gas gangrene remains a considerable risk due to lack of prevention of the infection, an absence of standard treatment away from the battlefield environment, and an increasing prevalence in elderly people and people with diabetes (Brown 1974; Titball 2005). The estimated number of cases in the USA is about 1000 per year (Gerding 2011). Injuries resulting from earthquake may suddenly increase the number of people suffering from gas gangrene (Pu 2008; Wang 2010). Several cases of gas gangrene have been also reported in injecting drug users in Scotland (McGuigan 2002), and patients undergoing liposuction in Germany (Lehnhardt 2008).

Traumatic injuries account for about 50% of civilian cases of gas gangrene, with vehicular accidents accounting for the majority (about 70%); the remaining cases develop in people after crush injuries, industrial accidents, gunshot wounds, and burns. Postoperative complications account for about 30% of cases, and are most frequently associated with surgery on the appendix, biliary tract, or intestine. Approximately 20% are spontaneous and associated with an occult (apparently symptom‐free, so 'hidden', and not known about) colonic malignancy (Bartlett 2007; Gerding 2011).

Gas gangrene carries a high fatality rate that ranges from 25% in those with trauma, to nearly 100% in those who do not receive treatment (Melville 2006; Gerding 2011). Inadequate treatment, advanced age, location of the infection on the trunk, severe underlying diseases, and shock are factors that increase the risk of a poor prognosis with gas gangrene (Gerding 2011). There is no indication from current studies that gender or race differences have an effect on the prognosis.

Diagnosis

Early diagnosis is the most crucial part of successful management of gas gangrene.

A diagnosis of gas gangrene can be suspected, until proven otherwise, when the following features are present: history of prior trauma or surgery, muscle swelling, severe pain, oedema (swelling due to accumulation of fluid), wound discolouration, watery discharge, haemorrhagic bullae (elevated blisters, usually exceeding 5 mm in diameter, filled with blood; Appendix 1), malodour (unpleasant smell; Appendix 1) and crepitus (a crackling sound; Appendix 1; Altemeier 1971; Hart 1990). A Gram‐stain of wound exudate is considered to be the most rapid means of confirming the suspected diagnosis (Hart 1990). Diagnosis should also involve histopathologic examination of the lesion for myonecrosis (necrotic damage) without polymorphonuclear leukocytes (a type of white blood cell), and imaging methods that find gas in the tissue (Gerding 2011). Anaerobic (oxygen‐free) cultures should be taken when the wound is debrided (trimmed of dead material; Appendix 1) to confirm the identity of the pathogens, but treatment should be initiated before the findings are available, because it usually takes 48 to 72 hours for Clostridium species to grow in culture media and a 24‐hour delay in treatment can be fatal to patients with gas gangrene (Altemeier 1971; Hart 1990). Spontaneous gas gangrene with the culture of C septicum should be carefully investigated, as it may have metastasised from the site of a gastrointestinal malignancy (Hart 1990).

Description of the intervention

Treating gas gangrene involves complex interventions encompassing immediate debridement, antibiotic treatment, hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) and systemic support treatment (Schwartz 1978; Stevens 2005). A combination of these interventions is necessary (Hart 1990; Brook 2008; Chen 2011). In addition, Chinese herbal medicine is sometimes used as an adjunct treatment (Zhao 2004; Liu 2011).

How the intervention might work

Immediate debridement

Surgical debridement is considered to be the cornerstone of treatment for gas gangrene. Once gas gangrene is suspected, an aggressive debridement of all tissues involved should be carried out immediately for early diagnosis and treatment (Schwartz 1978; Brook 2008; Chen 2011). Early surgical intervention with multiple incisions and fasciotomy (incisions that are left open to relieve underlying pressure in the tissues) involves the removal of all compromised tissue, foreign material and haematoma (collections of blood) to allow decompression and drainage (Brook 2008). Leaving the wounds wide open is necessary for aeration (oxygenation; Hart 1990).

While myositis (inflammation of muscle; Appendix 1) is still relatively localised, radical decompression of the fascial compartments involved (by free longitudinal incisions and excisions of the infected muscle) usually arrests the process, and eliminates the need for amputation in order to conserve a functional limb. Without timely debridement, gas gangrene may progress to the extremities, which may result in amputation (Altemeier 1971; Brook 2008). Though amputation does not apply to gas gangrene of the trunk, which has a much poorer prognosis, the aggressive debridement of compromised skin, muscle and fascia in that area is still necessary (Morgan 1971).

Antibiotic treatment

Antibiotics are as important in the treatment of gas gangrene as surgical debridement (Hart 1983).

Studies in animals have shown that prompt treatment with antibiotics can significantly improve survival rates (Marrie 1981; Stevens 1987a). Several types of antibiotics, including penicillin, clindamycin, rifampin, metronidazole, chloramphenicol, tetracycline, and erythromycin have been shown to be effective in vitro or in animal studies (Stevens 1987a; Stevens 1987b; Oda 2008). These antibiotics provide a diverse array of mechanisms of action, including inhibition of: cell wall synthesis (penicillin), protein synthesis (chloramphenicol, tetracycline, and clindamycin), RNA synthesis (rifampin), electron transport (metronidazole; Stevens 1987b), and release of the induced toxin (erythromycin; Oda 2008).

Historically in humans, penicillin G has been recommended in doses of between 10 and 24 million units per day (Holland 1975; Laflin 1976; Hart 1983). Currently, a combination of penicillin and clindamycin is widely used for treating clostridial gas gangrene (Stevens 2005). The rationale for using penicillin in combination with clindamycin is that some strains of Clostridium are resistant to clindamycin but susceptible to penicillin. Clindamycin is thought to be the superior drug for reducing toxin formation (Gerding 2011). In clinical practice, other antibiotics commonly used with penicillin G for treating gas gangrene include ceftriaxone and erythromycin (Headley 2003).

Other, non‐clostridial bacteria are frequently found in gas gangrene tissue cultures, so treatment that is active against Gram‐positive (e.g. penicillin or cephalosporin), Gram‐negative (e.g. aminoglycoside, cephalosporin, or ciprofloxacin), and anaerobic organisms (e.g. clindamycin or metronidazole) should be combined in the antibiotic therapy until the results of bacteriological culture are known (Folstad 2004; Trott 2005).

Additional therapy

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT)

HBOT is the medical use of oxygen at a pressure higher than atmospheric pressure. It produces a significant increase in the partial pressure of oxygen in body tissues, which suppresses the growth of anaerobic bacteria (Hart 1983). Another important role of HBOT is to relieve the hypoxic (oxygen‐poor) environment of surrounding ischaemic tissue, which limits the extent of necrosis (Hart 1990). Evidence derived from in vitro experiments and animal models indicated that HBOT can enhance survival, and exert a direct bactericidal effect on most Clostridium species by inhibiting alpha‐toxin production (Kaye 1967; Demello 1973; Hart 1983; Hirn 1993; Stevens 1993). HBOT has even been recommended before initial debridement on the basis of experimental evidence and the results of favourable clinical experience (Holland 1975).

The recommended pressure used in HBOT ranges from 2 to 3 atmospheres absolute pressure (ATA), and the exposure time ranges from 90 minutes, with 100% oxygen, to between five and 12 hours with periodic air breaks (Hart 1990). Clinical and experimental evidence has suggested that patients treated with 3 ATA for 90 minutes benefit from more conservative surgery and less extensive amputation, and that treatment with this regimen may be preferred (Tibbles 1996). Patients may tolerate exposure to oxygen pressures of up to 3 ATA for a maximum duration of 120 minutes (Tibbles 1996).

The recommendation, however, seems to lack sufficient supporting clinical evidence. A systematic review that evaluated the efficacy of HBOT for treating hypoxic wounds concluded that the therapeutic effect of HBOT is still unclear due to an absence of high‐quality trials (Wang 2003). As well as having questionable efficacy, HBOT may increase the risk of some adverse events including oxygen toxicity, barotrauma (damage caused by pressure differences between air spaces and fluids within the body; Appendix 1), decompression sickness, and pulmonary damage, most of which, however, seem to be reversible and self‐limiting (Hart 1990; Tibbles 1996).

Chinese herbal medicine

Results from case series suggest oral and topical (surface) use of Chinese herbs accompanied with debridement and antibiotic therapy may reduce fatalities caused by gas gangrene (Zhao 2004; Liu 2011). Typically, Chinese herbal medicine consists of complex prescriptions of a combination of several herbal components. The mechanism of action of the herbal medicines is reported to involve haemostasis (prevention of bleeding), detumescence (subsidence of swelling; Appendix 1) and antibacterial activity (Hou 2010).

Systemic support treatment

Supportive measures are an essential part of the treatment for gas gangrene, and include careful medical management and prompt therapy for complications of clostridial bacteraemia (bacteria in the blood; Appendix 1; Schwartz 1978).

Management of gas gangrene frequently involves volume expansion (of the blood) within the patient, with the addition of intravenous fluid, plasma and blood. A high level of calories, protein and vitamins should be also administered (Xiao 2008). Shock is a frequent complication of gas gangrene, and rapid volume expansion may be required to deal with it. Monitoring central venous pressure (Appendix 1) or pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (Appendix 1) may be valuable in severely ill patients. Additionally, careful monitoring of electrolytes and packed cell volume (of blood; Appendix 1) may also be necessary (Schwartz 1978; Hart 1990).

Other treatments

Hydrogen peroxide or potassium permanganate solution (both are antiseptic and oxidizing agents; Appendix 1) can be used to clean the wound site repeatedly, which may help to disinfect and improve the hypoxic condition (Chen 2011; Hu 2015).

Animal studies have shown that ozone (oxygen molecules with three atoms, rather than the normal two), which inactivates most bacterial species, may have some effect on treating gas gangrene (Rotter 1974; Stanek 1976).

Antitoxins, which are antibodies with the ability to neutralise a specific toxin, have been used to alleviate the poisoning symptoms, but the use of these is not recommended because of the risk of increasing hypersensitivity (undesirable reactions caused by the immune system; Appendix 1; Schwartz 1978).

Why it is important to do this review

Gas gangrene is a severe infection with a high fatality rate. Although it occurs less frequently than other wound infections, when it does occur, delay in diagnosis and treatment, or inadequate deployment of interventions may result in amputation, permanent disability or even death. Resolute and effective measures are needed to ensure favourable prognoses in people with gas gangrene. This review is intended to summarize current evidence of the efficacy and safety of possible interventions for treating gas gangrene, and to highlight gaps in the relevant research.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of potential interventions in the treatment of gas gangrene compared with alternative interventions or no interventions.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in which people, rather than limbs or wounds, were randomly allocated into different treatments. We also considered quasi‐randomised controlled trials (qRCTs), a study design that is considered secondary to RCTs in terms of the evaluation of efficacy. We excluded any other types of study.

Types of participants

Eligible studies in the review involved patients with gas gangrene irrespective of age, gender, etiology and severity. A diagnosis of gas gangrene depended on a history of serious trauma or surgery, with clinical presentation including wounds with unusual swelling and pain, and symptoms of systemic poisoning. We considered anaerobic bacterial culture and tissue biopsy as the gold standard for diagnosis. We accepted different authors' definitions of gas gangrene, but considered them critically.

Types of interventions

In this review, we considered all types of interventions for the treatment of gas gangrene. Interventions of interest included (but were not limited to) surgical debridement, antibiotic treatment, HBOT, Chinese herbal medicine, systemic support therapy, wound irrigation, ozone and antitoxin therapy. We included studies that compared one regimen or treatment with another regimen, or treatment with no treatment. We did not consider studies in which an individual might receive different comparative treatments to different limbs or wounds simultaneously.

Types of outcome measures

We analyzed end of treatment outcomes.

Primary outcomes

Amputation due to gas gangrene.

Infection‐related fatality attributed to gas gangrene.

Quality of life: measured by a standardised generic questionnaire such as EQ‐5D, SF‐36, or SF‐6, or SF‐12.

Secondary outcomes

All‐cause fatality.

Cure rate in a specified period of time. Cure was defined as disappearance of both clinical presentations and abnormal laboratory findings. Cure rate was defined as the proportion of patients being cured.

Time to complete healing during the trial period (at a patient level).

Severe adverse events or complications including, but not limited to: anaphylaxis (allergic reaction that may cause death), liver injury, gastrointestinal symptoms (caused by antibiotics), oxygen toxicity, barotrauma, decompression sickness, pulmonary damage (caused by HBOT), shock, renal failure and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases to identify reports of relevant clinical trials:

The Cochrane Wounds Group Specialized Register (searched 25 March 2015);

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2015, Issue 2);

Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to 24 March 2015);

Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations) (24 March 2015);

Ovid EMBASE (1974 to 24 March 2015);

EBSCO CINAHL (1982 to 25 March 2015);

Science Citation Index (1981 to March 2015);

China Biological Medicine Database (CBM‐disc; 1979 to March 2015);

China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI; 1979 to March 2015);

Chinese scientific periodical database of VIP INFORMATION (VIP; 1989 to March 2015).

We used the following search strategy in The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL):

#1 MeSH descriptor Gas Gangrene explode all trees #2 gas* NEXT gangrene:ti,ab,kw #3 clostridi* NEXT myonecrosis:ti,ab,kw #4 ((nonclostridi* OR non‐clostridi*) NEXT myonecrosis):ti,ab,kw #5 (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4)

The search strategies for Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE and EBSCO CINAHL can be found in Appendix 2. We combined the Ovid MEDLINE search with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomised trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐ and precision‐maximising version (2008 revision) (Lefebvre 2011). We combined the EMBASE search with the Ovid EMBASE trial filter terms developed by the UK Cochrane Centre (Lefebvre 2011). We combined the CINAHL search with the trial filters developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN 2015). Search strategies for the three databases of publications in Chinese are listed in Table 3.There were no restrictions with respect to language, date of publication or study setting.

1. Search strategies for databases in Chinese and trial registries.

| Search strategies |

| China Biological Medicine Database (CBM‐disc) |

| #1 "气性坏疽"[常用字段:智能] #2 "梭菌"[常用字段:智能] #3 "梭状"[常用字段:智能] #4 "肌坏死"[常用字段:智能] #5 "肌炎"[常用字段:智能] #6 (#2) OR (#3) #7 (#4) OR (#5) #8 (#6) AND (#7) #9 (#1) OR (#8) |

| China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) |

| (主题="气性坏疽") OR ((主题="梭菌"+"梭状") AND (主题="肌坏死"+"肌炎")) |

| Chinese scientific periodical database of VIP INFORMATION (VIP) |

| ((题名或关键词=肌坏死 或 文摘=肌坏死 或 题名或关键词=肌炎 或 文摘=肌炎 与 专业=经济管理+图书情报+教育科学+自然科学+农业科学+医药卫生+工程技术+社会科学 与 范围=全部期刊) 与 (题名或关键词=梭状 或 文摘=梭状 或 题名或关键词=梭菌 或 文摘=梭菌 与 专业=经济管理+图书情报+教育科学+自然科学+农业科学+医药卫生+工程技术+社会科学 与 范围=全部期刊)) 或者 (题名或关键词=气性坏疽 或 文摘=气性坏疽 与 专业=经济管理+图书情报+教育科学+自然科学+农业科学+医药卫生+工程技术+社会科学 与 范围=全部期刊) |

| Science Citation Index |

| Gas gangrene or clostridi* myonecrosis |

| ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) |

| "Gas Gangrene"(By topics) |

| Current Controlled Trials (www.controlled‐trials.com) |

| "gas gangrene" or "myonecrosis" |

| WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/trialsearch) |

| gas gangrene or clostridi* myonecrosis or non‐clostridi* myonecrosis or nonclostridi* myonecrosis |

| Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (www.anzctr.org.au) |

| "gas gangrene" or "clostridial myonecrosis" or "non‐clostridial myonecrosis" or "nonclostridial myonecrosis" |

We also searched the following clinical trials registries:

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov);

Current Controlled Trials (http://www.controlled‐trials.com/);

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/);

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (http://www.anzctr.org.au/).

The search strategies for the above registries are listed in Table 3.

Searching other resources

We tried to identify additional studies by searching the reference lists of all relevant trials and reviews we identified.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Independently, two review authors (ZY, JH) selected trials that met the inclusion criteria from all references retrieved by the search. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion between the authors, with adjudication by the third review author (YQ).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (ZY, YQ) independently extracted the details of study population (age, gender, setting, severity, pathogen), characteristics of the study, nature of the interventions and outcomes, using a pre designed data extraction form. We tried to contact the authors of the original studies to obtain more information in the case of missing or unclear data. With differences in data extraction identified, we referred back to the original articles and discussed the differences. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third author (JH) and through consensus.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (ZY, YQ) performed methodological quality assessments independently, using the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreement through discussion with a third review author (SZ).

The Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias includes seven specific domains, namely:

random sequence generation;

allocation concealment;

blinding of participants and personnel;

blinding of outcome assessment;

incomplete outcome data;

selective outcome reporting;

other sources of bias, which were divided into two aspects in our review: confirmed diagnosis of gas gangrene, and comparability of baseline characteristics between groups.

Each criterion was judged as being: 'low' (meaning low risk of bias), 'high' (high risk of bias) or 'unclear' (lack of information or uncertainty about the risk of bias). We present our assessment of risk of bias in a 'Risk of bias' summary figure that displays the quality of all included studies.

Measures of treatment effect

We intended to report quantitative data from individual trials for outcomes listed in the inclusion criteria using risk ratios (RR) for dichotomous outcomes, standardised mean differences (SMD) for continuous outcomes (e.g. quality of life), and hazard ratios (HR) for time‐to‐event outcomes (e.g. time to healing), all with 95% confidence intervals (CI), where appropriate.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis for all outcomes in our review was the individual rather than a limb or a wound. Where the limb or the wound was used as the unit of analysis in studies, we planned to contact the authors to establish whether an individual received only one treatment. If so, we would have asked for the data at individual level; otherwise, we would have excluded these studies.

Dealing with missing data

We tried to contact the authors of the included trials to obtain missing data, but did not receive a response. For time‐to‐event outcomes, if the authors did not report HR and 95% CI in the primary studies, we planned to ask them to provide the summary results or individual patient data. If missing data could not be obtained from the study authors, our plan was to analyse the data that were available, and then to perform sensitivity analyses where we assumed the worst outcome for participants lost to follow‐up.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed studies for clinical heterogeneity by checking the inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, differences in the interventions and in the definition and measurement of outcomes. We also assessed methodological heterogeneity by examining the risk of bias of all included trials. In addition, we planned to calculate the Q statistic and I² values to quantify statistical heterogeneity. We planned to interpret I² values of more than 50%, or a P value of less than 0.10, as representing substantial heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

If sufficient studies had been available, we would have assessed publication bias for primary outcomes by means of a funnel plot. Evidence of asymmetry in funnel plots would have indicated possible publication bias.

Data synthesis

We intended to conduct a head‐to‐head comparison across trials using the statistical package within the Cochrane review‐writing software, Review Manager (RevMan; RevMan 2014). We would have expressed results as RR with 95% CI for dichotomous outcome measures; SMD with 95% CI for continuous outcomes such as quality of life, where different assessment scales may be used in different studies; and HR with 95% CI for time‐to‐event outcomes. We planned to use a fixed‐effect model unless there was evidence of heterogeneity (I² over 25%) that suggested that a random‐effects model would be more appropriate. For time‐to‐event data, we planned to use the inverse variance method on the estimated HR and standard error. If there had been high statistical heterogeneity (I² over 50%), we would not have pooled the results, but presented them in a narrative format.

However, because of the small number of included studies and substantial clinical heterogeneity between them, we did not implement the above plan.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

In the presence of sufficient studies, we would have conducted analyses separately to study the difference in results for the following groups:

etiologies: post‐traumatic, postoperative and spontaneous;

location of gas gangrene: extremity versus trunk;

patient age: children (aged between 0 and 18 years) compared with adults (over 18 years).

Sensitivity analysis

In the presence of a sufficient number of studies, we would also have performed a sensitivity analysis to investigate whether, and how, results might have been affected by studies with missing data or without adequate allocation concealment, blinding, or a clearly specified definition of gas gangrene, by excluding them from the analyses.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The total of 2481 citations identified through our searches included 1600 unique references from the electronic databases, seven unique records from the trial registries and 874 duplicate records, which we removed. Checking the remaining titles and abstracts allowed us to exclude a further 1599 irrelevant records, leaving us with eight references for full‐text assessment. We excluded five references for the reasons outlined in Characteristics of excluded studies. We included two trials and detailed their characteristics in Characteristics of included studies. There is an ongoing trial (NCT02111161), the full text of which requires further assessment for eligibility. Details of the information available for this trial and the reason for it awaiting classification are listed in Characteristics of ongoing studies. The selection flow is shown in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram

Included studies

Two single‐centre RCTs with parallel design met our inclusion criteria for types of studies, participants, and interventions completely (Hou 2010; Li 2001; Characteristics of included studies). Cure rate, which we had defined as a secondary outcome in our review, was the only primary outcome used in both trials. We included the trials since they provided the most relevant evidence available on the topic.

The first trial started in 1980 and was conducted in a general hospital with 400 beds and 1.6 million outpatients per year (Hou 2010). The trialists randomized 46 patients with crepitus around their wounds and X‐rays indicating gas between the muscles in wounds into two groups. Both groups received identical debridement, antibiotics and symptomatic treatments, but the intervention group also received Chinese herbal medicine for dressing and oral use. The herbal medicine was prepared locally with Cirsium setosum (field thistle/Herba Cirsii), Portulaca oleracea (purslane/verdolaga), and Sedum lineare (carpet sedum/needle stonecrop). Information about who prepared and administered the herbal medicine was not available. Treatment duration ranged from two to eight weeks without blinding. Cure rate was the only outcome analyzed in the trial, and was defined as significant improvement in symptoms, signs and laboratory results after one week of treatment, and disappearance of swelling, pain and other symptoms, normal laboratory results, and no amputation after two to five weeks of treatment. Improvement of participants was defined as improvement in symptoms after one week of treatment and normal signs, normal laboratory results and no amputation after two to eight weeks of treatment. Failure was defined as no improvement, or deterioration in symptoms or signs after one week of treatment, or transfer to another hospital for further treatment. Cure rate was defined as the proportion of patients who were cured or improved.

The second trial was also conducted in a general hospital with 520 beds and 0.2 million outpatients per year (Li 2001). The trial started in 1995. All 44 participants had a confirmed diagnosis of gas gangrene through anaerobic cultures, 47.7% (21/44) of whom were infected with Clostridium perfringens. Participants in the two groups received debridement and antibiotic treatment, as well as topical or systemic HBOT. Participants were followed up for 10 days. Again, cure rate was the only outcome analyzed in the trial. Cure was defined as disappearance of both the symptoms and purulent excreta within a wound, and formation of granulation tissue or healing by secondary intention. Significant improvement was defined as a significant improvement in symptoms of gas gangrene, reduction in the area of the wound, a significant decrease in purulent excreta within the wound, and formation of granulation tissue. Moderate improvement was defined as improvement in symptoms of gas gangrene, with a clear border to the wound, and a decrease in purulent excreta within the wound. Failure was defined as no improvement in symptoms, with an unclear border to the wound, and no reduction in purulent excreta within the wound. Cure rate was defined as the proportion of participants who were cured or significantly improved.

However, both definitions of cure rate used in these trials differed from that specified in our review (Secondary outcomes).

Excluded studies

We excluded two animal studies (Zhang 1988; Rao 1994), three observational studies (Mou 1985; Luo 1987; Ma 2008), and one systematic review (Raman 2006; Characteristics of excluded studies).

Risk of bias in included studies

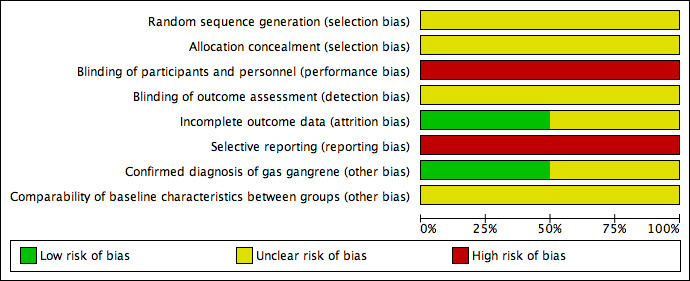

Summaries of the risk of bias are shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Allocation

Both included studies stated that they used a method of randomisation, but neither study detailed the methods of random sequence generation or allocation concealment employed (Li 2001; Hou 2010), so selection bias may exist.

Blinding

Although blinding methods were not specified in either trial (Li 2001; Hou 2010), it seemed impossible to have blinded both the participants and personnel to the allocated treatments. Since placebo was not given to the control group, the participants in Hou 2010 were likely to know whether they received Chinese herbs. As the procedures for delivering topical and systemic HBOT are different, the participants in Li 2001 could also have identified the treatment they received. The personnel in both studies would also be aware of the interventions assigned to the participants. As a result, performance bias seems inevitable.

No information about whether the outcome assessors were aware of grouping information before the measurement of participants' outcomes was available from either trial. Consequently, detection bias may exist.

Incomplete outcome data

Both studies included all randomly allocated participants in their analysis (Li 2001; Hou 2010). The Hou 2010 study may have been subject to attrition bias, because of those participants who transferred to other hospitals, for whom actual outcomes were unavailable other than having been defined by the study authors as failing to improve. There was insufficient information to judge whether the number of transfers were balanced across the two groups. If attrition occurred in different proportions across the groups, this would introduce attrition bias.

Selective reporting

The outcome of cure rate analyzed in both studies was a composite outcome, consisting of several components such as amputation and symptom improvement (Li 2001; Hou 2010). However, the number of amputations or symptom improvements were not specified, which indicates selective reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

Two aspects were considered for other sources of bias: misdiagnosis of gas gangrene and imbalance of baseline characteristics between groups. The Hou 2010 study did not provide results of anaerobic cultures or details of comparisons of baseline characteristics between groups. We could not confirm whether the trial was subjected to either bias. The Li 2001 study confirmed diagnosis of gas gangrene for all the participants through anaerobic culture, but did not report results about the comparison of some important between‐group characteristics at baseline.

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings. Additional Chinese herbs compared with no additional Chinese herbs for treating gas gangrene.

| Additional Chinese herbs compared with no additional Chinese herbs for treating gas gangrene | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with gas gangrene Setting: a general hospital with 400 beds and 1.6 million outpatients per year Intervention: additional Chinese herbs Comparison: no additional Chinese herbs | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no Chinese herbs | Risk with Chinese herbs | |||||

| Cure rate follow up: range 2 weeks to 8 weeks | Study population | RR 3.08 (1.00 to 9.46) | 46 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 | ||

| 150 per 1000 | 462 per 1000 (150 to 1000) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded two levels due to limitations in design; high risk of performance and reporting bias, and unclear risk of bias in other bias sources.

2 Downgraded two levels due to imprecision; only one trial with small sample size and very wide confidence interval that included the possibility of an effect in either direction (crosses line of no effect).

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings. Additional topical HBOT compared with additional systemic HBOT for treating gas gangrene.

| Additional topical HBOT compared with additional systemic HBOT for treating gas gangrene | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with gas gangrene Setting: a general hospital with 520 beds and 0.2 million outpatients per year Intervention: additional topical HBOT Comparison: additional systemic HBOT | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with systemic HBOT | Risk with Topical HBOT | |||||

| Cure rate follow up: mean 10 days | Study population | RR 1.10 (0.25 to 4.84) | 44 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 | ||

| 130 per 1000 | 143 per 1000 (33 to 631) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; HBOT: hyperbaric oxygen therapy. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded two levels due to limitations in design; high risk of performance and reporting bias, and unclear risk of bias in selection and detection bias.

2 Downgraded two levels for imprecision; only one trial with small sample size and very wide confidence interval that included the possibility of an effect in either direction (crosses line of no effect).

We identified two trials that we included in the review. One assessed the efficacy of adjunctive use of Chinese herbs (Hou 2010), and the other the adjunctive use of topical versus systemic HBOT in the treatment of gas gangrene (Li 2001). We did not identify trials that investigated other interventions. See: Table 1 and Table 2. For both trials the GRADE assessment was very low quality evidence due to risk of bias and imprecision.

Chinese herbal medicine

Primary outcomes

The Hou 2010 study did not assess any of the primary outcomes defined in our review.

Secondary outcomes

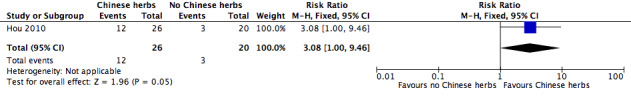

Cure rate at the end of the Hou 2010 study was the only outcome reported. In the group treated with Chinese herbs (26 participants), 12 were cured, 9 were improved and 5 were not improved. The cure rate defined in the trial for this group was 80.8% (21/26), but if the rate was recalculated according to that defined in our review the rate was 46.2% (12/26). In comparison, in the group that did not receive treatment with Chinese herbs (20 participants), three were cured, six were improved and 11 were not improved. The cure rate defined in the trial was 45.0% (9/20), but if the rate was recalculated according to the definition used in this review (Secondary outcomes) it was reduced to 15.0% (3/20). According to the calculation in the trial and our review, the RRs were 1.79 (95% CI 1.07 to 3.02) and 3.08 (95% CI 1.00 to 9.46; Figure 4), respectively, and favoured adjunctive Chinese herbal medicine.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Additional Chinese herbs versus no additional Chinese herbs, outcome: 1.1 Cure rate.

Topical HBOT

Primary outcomes

The Li 2001 study did not assess any of the primary outcomes defined in our review.

Secondary outcomes

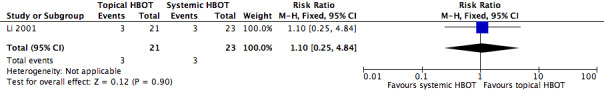

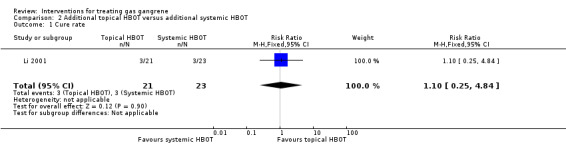

Cure rate after 10 days of treatment was the only outcome reported from the Li 2001 study. In the topical HBOT group (21 participants) 3 participants were cured, 16 were significantly improved and 2 were moderately improved, with a defined cure rate of 90.5% (19/21). By comparison in the systemic HBOT group (23 participants), 3 were cured, 8 were significantly improved, 11 were moderately improved and 1 did not improve, with a defined cure rate of 47.8% (11/23). The RR reported in the study was 1.89 (95% CI 1.21 to 2.96). However, when we used our definition of cure, our calculations provided a cure rate of 14.3% (3/21) in the topical HBOT group and of 13.0% (3/23) in the systemic HBOT group, with an RR of 1.10 (95% CI 0.25 to 4.84; Figure 5; Secondary outcomes).

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Additional topical HBOT versus additional systemic HBOT, outcome: 2.1 Cure rate.

Discussion

Summary of main results

At present, high quality evidence to determine the efficacy and safety of possible interventions for treating gas gangrene is unavailable. Only two RCTs that focused on topical HBOT and adjunctive use of Chinese herbs (Li 2001; Hou 2010) were found and both were at high or unclear risk of bias. Most of the important outcomes were not reported, including all the primary outcomes (Primary outcomes) we had hoped to include in our review; nor were there any reports of adverse events. The only outcome reported was cure rate, which was one of the secondary outcomes we had planned to include in our review, but the measures for this outcome differed between the two trials.The authors' definitions of cure rate, which included patients who were either cured or improved in the calculation (Included studies), differed from our definition. Re‐analysis of the cure rate based on our definition (i.e. only including participants who were cured; Secondary outcomes) showed limited evidence of benefit for the addition of Chinese herbs to standard treatment and no evidence of benefit for topical HBOT over systemic HBOT.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Both studies included all randomized participants in the analysis without reporting the number lost to follow‐up. Participants who transferred to other hospitals may have produced censored data, but in Hou 2010 transfer was considered as an indication of treatment failure, which would tend to generate a misleading estimate, if outcomes were missing in imbalanced proportions across the groups. A higher proportion of transfers in the treatment group probably resulted in a conservative estimate of effect size on cure rate and a higher proportion in the control group probably led to an overestimate of the effect. Durations of follow‐up for each individual that varied from two to eight weeks may also have led to incompleteness in outcome detection in the Hou 2010 study, but specific information about whether and how data were incomplete was not available. Participants in the Li 2001 study were only followed up for 10 days and longer‐term outcomes were not reported.

The applicability of the evidence may have been influenced by the practice settings, patient characteristics, and causative agents. The two trials were conducted in general hospitals in Chinese towns, where healthcare resources and economic levels could not be comparable to those in tertiary hospitals in urban areas. The majority of participants had crepitus around their wounds, and X‐rays indicated gas between muscles in wounds. The duration of gas gangrene at baseline varied from two to 15 days in one study (Hou 2010), and from six hours to two weeks in the other (Li 2001). In the latter study, all the participants were diagnosed with gas gangrene through bacterial culture, but the pathogens varied between participants, with Clostridium perfringens accounting for nearly half of the participants.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence currently available is extremely low (Table 1; Table 2). The trials suffered from a high risk of bias in selective reporting and blinding of the participants and personnel. Some important methodological aspects of the RCTs were unclear, including random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessment and comparability of baseline characteristics. Data on the primary outcomes we hoped to include in our review were not available from the included studies. Cure rate, which we had defined as a secondary outcome for our review, was the only outcome the studies reported. This outcome could not reflect practitioners' and patients' main concerns about amputation, fatality and quality of life, and thus it is difficult to generalise the reported effects on cure rate to more relevant clinical outcomes. Small sample sizes within each study also resulted in low precision of the estimates. The small number of included studies made it impossible to assess consistency across studies with regard to publication bias.

Potential biases in the review process

Although we conducted a thorough review of published studies and ongoing trials, it remains possible that some relevant trials completed before the establishment of trial registries may not have released their results. We tried to contact the authors of the two included trials to obtain missing data, but we did not receive any response.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

In addition to the one included trial that investigated Chinese herbs, we identified several observational studies (Tang 1982; Yu 1986; Ma 1991; Zhao 2004; Liu 2011). These all supported the adjunctive use of Chinese herbs, but their efficacy remains controversial because the studies were all case series without any control group, the herbs differed from study to study, and the sample sizes were small, varying from four to 20 participants.

Wth regard to the effectiveness of HBOT, other clinical evidence focused more on whether adjunctive use of HBOT can improve the prognosis of gas gangrene, but its benefits and harms remains controversial because of inconsistent results. A systematic review suggested a lack of trials to support the HBOT use for gas gangrene (Wang 2010), while the results of two retrospective multicentre studies did not demonstrate a survival advantage with HBOT for major necrotising infections that included gas gangrene (Brown 1994; George 2009). Furthermore, subgroup analysis for clostridial myonecrosis in retrospective comparative effectiveness research that included nearly 46,000 patients with necrotising soft tissue infections indicated that patients who received HBOT did not have a statistically significantly lower risk of mortality or complications (Soh 2012). Similar results have also been reported in some retrospective studies of HBOT added to surgery and antibiotic treatment for gas gangrene (Hart 1983; Shupak 1984; Korhonen 1999).

However, another systematic review concluded that evidence from some high quality observational studies suggested that HBOT may be an effective way to treat gas gangrene (Saunders 2003), but this review did not provide the list of the included studies or sufficient details about their study characteristics to substantiate this conclusion. Another review (Leach 1998), which was based on experimental research and clinical experience, suggested that additional HBOT for the treatment of gas gangrene was supported by strong scientific evidence, however the authors did not draw their conclusions from RCTs, since no trials were identified.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is insufficient robust evidence from RCTs to support the use of adjunctive treatment with Chinese herbal medicine or topical HBOT for gas gangrene in practice. The quality of the available evidence is extremely low. The possibility of the beneficial effects shown in the trials cannot be confirmed due to potential bias, the small number of study participants and variations in outcome definitions. In addition, no clinical trials evaluated the efficacy and safety of other potential treatments for gas gangrene. Consequently, decision‐making for patients with gas gangrene needs to be based on relevant evidence from well‐designed observational studies, professional experience, patients' preference and the availability of healthcare resources.

Implications for research.

Further research needs to include (and classify) patients with gas gangrene (eg.post‐traumatic, postoperative and/or spontaneous), compare cornerstone treatments (e.g. penicillin and clindamycin versus penicillin alone) or controversial treatments (e.g. adjunctive hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) versus no adjunctive HBOT), and to assess the more relevant clinical outcomes (e.g. death, amputation, quality of life and adverse events). Either randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or observational studies could be considered for the assessment.

When designing a RCT, researchers should guarantee high methodological quality by implementing appropriate randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding and sample size calculation based on an important clinical outcome. A double‐blind trial that is currently ongoing aims to assess the efficacy and safety of immunoglobulin for necrotising soft tissue infections including gas gangrene, Fournier gangrene, necrotising fasciitis and other types of infection (NCT02111161). Although the trial does not target gas gangrene specifically, it would be helpful if a subgroup analysis could be conducted separately for those participants with gas gangrene.

Although time consuming and expensive, RCTs need to be multicentred and conducted over a long period to ensure an adequate sample size because of the rarity and critical nature of gas gangrene (Soh 2012). Observational studies may be an alternative way to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of treatments, but methodology should be rigorous, and sufficient power should be secured. A variety of confounders, such as etiology, pathogen, wound location, adjunctive treatments and so on, needs to be measured and controlled.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks also to peer referees (Elizabeth McInnes, Mark Rodgers, Marialena Trivella, Dirk Ubbink, Uwe Wollina, Gillian Ray‐Barruel, and Durhane Wong‐Rieger, Bestun Ahmed) and copy‐editor Elizabeth Royle.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Glossary

Antitoxin: antibody produced in response to a toxin of bacterial, animal, or plant origin (the origin in this text refers to the clostridial bacteria causing gas gangrene) with the ability to neutralise the effects of the toxin.

Barotrauma: physical damage to body tissues caused by a difference in pressure between an air space inside or beside the body and the surrounding fluid. Damage occurs in the tissues around the body's air spaces because gases are compressible and the tissues are not. During increases in external pressure, the internal air space provides the surrounding tissues with little support to resist the higher pressure. During decreases in external pressure, the higher pressure of gas trapped inside air spaces within the body causes damage to the surrounding tissues.

Central venous pressure: the venous pressure as measured at the right atrium, one of the two blood collection chambers of the heart. The pressure can be measured by means of a catheter (tube) introduced through the median cubital vein, a superficial vein of the upper limb, to the superior vena cava, one of the veins that carry blood to the heart's right atriums.

Clostridial bacteraemia: the presence of clostridial bacteria in the blood. Since the blood is normally a sterile environment, the detection of bacteria in the blood (most commonly with blood cultures) is always abnormal.

Crepitus: a sound or feeling that resembles the crackling noise heard when rubbing hair between the fingers or throwing salt on an open fire. In gas gangrene, crepitus is caused by rubbing of bone fragments and air in superficial tissues.

Debridement: surgical removal of foreign material and dead tissue from a wound in order to promote healing and prevent infection.

Detumescence: reduction of swelling or the subsidence of anything swollen.

Exotoxins: potent toxins secreted by micro‐organisms and released into their surroundings. These can cause damage to people by destroying cells or disrupting normal cellular metabolism. Exotoxins are proteins and so can be destroyed by heat, or detoxified by treatment with formaldehyde. Bacteria of the genus Clostridium are one of the most frequent producers of exotoxins.

Haematogenous spread: the term given to the dissemination of Clostridium through the blood stream, usually to an extremity or abdominal wall, causing necrotising infection.

Haemorrhagic bulla: a fluid‐containing, elevated lesion of the skin, usually more than 5 mm in diameter and characterised by bleeding beneath the skin, with a very clear boundary.

Hydrogen peroxide: an unstable compound of hydrogen and oxygen that is easily broken down into water and oxygen. A 3% solution is used as a mild antiseptic for the skin and mucous membranes.

Hypersensitivity: a state in which the body reacts with an exaggerated immune response to something it perceives to be a foreign substance.

Malodour: gangrene is accompanied by a distinctive odour that is offensively unpleasant.

Myositis: inflammation of a muscle, especially a skeletal muscle which is used to move bones, characterised by pain, tenderness, and sometimes spasm in the affected area.

Necrosis: the death of cells or tissues from severe injury or disease, especially in a localised area of the body. Causes of necrosis include inadequate blood supply (as in infarcted tissue), bacterial infection, traumatic injury, and hyperthermia (being too hot).

Packed cell volume: the ratio of the volume occupied by packed red blood cells to the volume of the whole blood.

Potassium permanganate: a dark purple crystalline compound used as a disinfectant in medicine.

Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure: an indirect measure of the pressure in the leftatrium, one of the two blood collection chambers of the heart. The pressure can be obtained by wedging a catheter (tube) into a small pulmonary artery (artery which carries blood from the heart to the lungs) tightly enough to block flow from behind and thus to sample the pressure beyond.

Serosanguinous exudate: the liquid that drains from open wounds in the human body. Exudate is made up of the serum around inflamed and damaged tissue. One type of exudate, called serosanguinous exudate, appears pink due to a small number of blood cells mixing with the fluid that is draining out.

Appendix 2. Search strategies

Ovid MEDLINE

1 exp Gas Gangrene/ 2 (gas* adj gangrene).tw. 3 (clostridi* adj myonecrosis).tw. 4 ((nonclostridi* or non‐clostridi*) adj myonecrosis).tw. 5 or/1‐4 6 randomized controlled trial.pt. 7 controlled clinical trial.pt. 8 randomized.ab. 9 placebo.ab. 10 clinical trials as topic.sh. 11 randomly.ab. 12 trial.ti. 13 or/6‐12 14 (animals not (humans and animals)).sh. 15 13 not 14 16 5 and 15

Ovid EMBASE

1 exp gas gangrene/ 2 (gas* adj gangrene).tw. 3 (clostridi* adj myonecrosis).tw. 4 ((nonclostridi* or non‐clostridi*) adj myonecrosis).tw. 5 or/1‐4 6 Randomized controlled trials/ 7 Single‐Blind Method/ 8 Double‐Blind Method/ 9 Crossover Procedure/ 10 (random$ or factorial$ or crossover$ or cross over$ or cross‐over$ or placebo$ or assign$ or allocat$ or volunteer$).ti,ab. 11 (doubl$ adj blind$).ti,ab. 12 (singl$ adj blind$).ti,ab. 13 or/6‐12 14 exp animals/ or exp invertebrate/ or animal experiment/ or animal model/ or animal tissue/ or animal cell/ or nonhuman/ 15 human/ or human cell/ 16 and/14‐15 17 14 not 16 18 13 not 17 19 5 and 18

EBSCO CINAHL

S18 S5 AND S17 S17 S6 or S7 or S8 or S9 or S10 or S11 or S12 or S13 or S14 or S15 or S16 S16 MH "Quantitative Studies" S15 TI placebo* or AB placebo* S14 MH "Placebos" S13 TI random* allocat* or AB random* allocat* S12 MH "Random Assignment" S11 TI randomi?ed control* trial* or AB randomi?ed control* trial* S10 AB ( singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl* ) and AB ( blind* or mask* ) S9 TI ( singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl* ) and TI ( blind* or mask* ) S8 TI clinic* N1 trial* or AB clinic* N1 trial* S7 PT Clinical trial S6 MH "Clinical Trials+" S5 S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 S4 TI ( (nonclostridi* or non‐clostridi*) N1 myonecrosis ) OR AB ( (nonclostridi* or non‐clostridi*) N1 myonecrosis ) S3 AB clostridi* N1 myonecrosis OR TI clostridi* N1 myonecrosis S2 AB gas* N1 gangrene OR TI gas* N1 gangrene S1 (MH "Gas Gangrene")

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Additional Chinese herbs versus no additional Chinese herbs.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Cure rate | 1 | 46 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.08 [1.00, 9.46] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Additional Chinese herbs versus no additional Chinese herbs, Outcome 1 Cure rate.

Comparison 2. Additional topical HBOT versus additional systemic HBOT.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Cure rate | 1 | 44 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.25, 4.84] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Additional topical HBOT versus additional systemic HBOT, Outcome 1 Cure rate.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Hou 2010.

| Methods | Single‐centre RCT with parallel design | |

| Participants | 46 participants with crepitus around their wounds and X‐rays indicating gas between muscles in wounds were recruited. Recruitment commenced in 1980 Intervention group: 26 participants, 21 male and 5 female. Their ages ranged from 23 to 68 years, with an average age of 41 years. Duration of gas gangrene varied from 2 to 13 days, and body temperature varied from 37.8 ℃ to 40.1 ℃. According to laboratory tests, 16 participants had leukocytosis, 3 had lowered haemoglobin, 1 had high fasting glucose, 2 had an increase in blood urea nitrogen, 2 had elevated transaminase levels, and 4 an electrolyte disorder. X‐rays showed that none had fractures Control group: 20 participants, 18 male and 2 female. Their ages ranged from 16 to 72 years, with an average age of 43 years. Duration of gas gangrene varied from 2 to 15 days, and body temperature varied from 38.1 ℃ to 41.1 ℃. According to laboratory tests, 11 participants had leukocytosis, 4 had lowered haemoglobin, 3 had high fasting glucose, 4 had an increase of blood urea nitrogen, 3 had elevated transaminase levels, and 3 had an electrolyte disorder. It was unclear whether some had fractures, as no related information was explicitly reported |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention group: debrided with multiple incisions, all compromised tissue removed, washed with hydrogen peroxide; antibiotic treatment consisting of penicillin 2.4 g iv 4 times daily and tinidazole 0.4 g iv twice daily; traditional Chinese medicine dressing with mashed Cirsium setosum (field thistle/Herba Cirsii), Portulaca oleracea (purslane/verdolaga), and Sedum lineare (carpet sedum/needle stonecrop), 30 g of each herb; oral medication with 50ml squeezed juice of the same Chinese herbs, 20 g for each herb, 4 times daily; symptomatic treatment. Control group: the same debridement, antibiotics and symptomatic treatment as those in the intervention group, but without traditional Chinese medicine dressing or oral medication |

|

| Outcomes | The only outcome reported from the study was cure rate. 'Cure' was defined as significant improvement in symptoms, signs and laboratory tests after 1 week of treatment, and limb salvage with disappearance of swelling, pain and other symptoms and after 2 to 5 weeks of treatment. 'Improved' was defined as improvement in symptoms after 1 week of treatment and limb salvage with normal signs and laboratory tests after 2 to 8 weeks of treatment. 'No improvement' was defined as no improvement or deterioration in symptoms and signs after 1 week of treatment or being transferred to other hospitals for further treatment. 'Cure rate' was defined as the proportion of patients who were cured or improved | |

| Notes | We defined cure rate as the proportion of patients being cured and re‐calculated it, using this definition, in this review. Both the results of the trial and our review are shown in Effects of interventions. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Although the authors stated randomisation was used for allocation, information about the methods of random sequence generation was not available |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Information about allocation concealment was not available |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Comment: The lack of placebo treatment for the control group probably informed participants of their treatment group |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: Information about blinding was not available |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: Participants who transferred to other hospitals were regarded as treatment failures, but it was unclear how many were transferred, and whether they were lost to follow‐up as a result of the transfer |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Comment: Information about important outcomes was not available |

| Confirmed diagnosis of gas gangrene (other bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Information about anaerobic cultures was not available |

| Comparability of baseline characteristics between groups (other bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Although the authors stated that there were no significant differences in age and infection severity, the definition of infection severity was unclear, and information that would have permitted comparison in age and infection severity between the 2 treatment groups was not available |

Li 2001.

| Methods | Single‐centre RCT with parallel design | |

| Participants | 44 participants with gas gangrene confirmed through anaerobic cultures were recruited. Recruitment started in 1995 Anaerobic bacteria identified included: 21 cases of Clostridium perfringens, 17 cases of Bacillus bellonesis, 8 cases of B septicus, and 7 cases of B histolyticus. Combinations of the above anaerobic bacteria and other purulent bacteria were found in 42 cases Intervention group: 21 participants, 14 male and 7 female. Their ages ranged from 12 to 43 years, and duration of gas gangrene varied from 6 hours to 1 week. Open fracture was found in 10 cases, muscle contusion in 6 cases, foreign bodies in wounds in 4 cases, and amputation in 1 case. X‐rays identified gas between muscles in wounds in 17 cases Control group: 23 participants, with 15 male and 8 female. Their ages varied from 13 to 46 years, and duration of gas gangrene varied from 8 hours to 2 weeks. Open fracture was found in 9 cases, muscle contusion in 6 cases, foreign bodies in wounds in 7 cases, and amputation in 1 case. X‐rays identified gas between muscles in wounds in 18 cases |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention group: topical use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) in combination with debridement and antibiotic treatment. The wound was placed in a therapy chamber and exposed to a high level of oxygen 3 times daily for 2 hours each time. Oxygen was pumped in at a velocity of 2 to 4 L/min, and pressure of 2.7 to 3.7kPa Control group: systemic use of hyperbaric oxygenation in combination with debridement and antibiotics treatment. A traditional method called "three days seven times" was used for the HBOT. The participants treated with this method inhaled high concentrations of oxygen 3 times on the first day after debridement, twice on the second and the third days, and once daily thereafter |

|

| Outcomes | The only outcome reported in the study was cure rate. 'Cure' was defined as the disappearance of the symptoms of gas gangrene, significant decrease in purulent excreta within a wound, and formation of granulation tissue within a wound or the healing of a wound by secondary intention. 'Significant improvement' was defined as a significant improvement in symptoms of gas gangrene, reduction in the area of a wound, significant decrease in purulent excreta within a wound, and formation of granulation tissue. 'Moderate improvement' was defined as an improvement in symptoms of gas gangrene, with a clear border to the wound, and a decrease in purulent excreta within a wound. 'No improvement' was defined as no improvement in symptoms, with an unclear border to a wound, and an increase in purulent excreta within a wound. Cure rate was defined as the proportion of participants who were cured or significantly improved | |

| Notes | It was unclear how systemic HBOT was given to the control group and whether the 2 groups received the same treatments with the exception of HBOT, because further details about interventions, such as the duration and pressure of HBOT in the control group and the types of antibiotics in both groups, were not available We defined cure rate as the proportion of patients who were cured and recalculated it, using this definition, in this review. Both the results of the trial and our review are shown in Effects of interventions |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Although the authors stated that randomisation was used for allocation, information about the methods of random sequence generation was not available |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Information about allocation concealment was not available |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Comment: Blinding seems to have been impossible because the interventions compared differed in their delivery method |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: Information about blinding was not available |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Comment: All the randomized participants were included in the analysis and no information indicated that any participant was lost to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Comment: Information about important outcomes was not available |

| Confirmed diagnosis of gas gangrene (other bias) | Low risk | Comment: All included participants with clinical presentations of gas gangrene were swabbed and the swabs cultured to confirm infection by anaerobic bacteria. Information about the proportion of each bacterial type was presented |

| Comparability of baseline characteristics between groups (other bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Information that would have permitted comparison of characteristics between the 2 groups at baseline was not available |

Abbreviations

HBOT: hyperbaric oxygen therapy iv: intravascular RCT: randomized controlled trial

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Luo 1987 | Observational study |

| Ma 2008 | Observational study |

| Mou 1985 | Observational study |

| Raman 2006 | Systematic review |

| Rao 1994 | Animal study |

| Zhang 1988 | Animal study |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

NCT02111161.

| Trial name or title | Immunoglobulin for necrotizing soft tissue infections: a randomised controlled trial |

| Methods | Double‐blinded phase 2 RCT with parallel design |

| Participants | Adult patients with NSTI based on surgical findings who were admitted to or planned to be admitted to the ICU at Rigshospitalet. Targeted population includes those with gas gangrene, Fournier gangrene, necrotising fasciitis and other NSTIs. |

| Interventions |

Intervention group: IVIG (Privigen) plus basic treatments Control group: saline 0.9% plus basic treatments |

| Outcomes |

Primary outcomes: Physical Component Summary Score of Short‐Form 36 in the sixth month after randomisation Secondary outcomes

|

| Starting date | April 2014 |

| Contact information | Principal Investigator: Professor Anders Perner; Email: anders.perner@regionh.dk |