Abstract

Objective

Many companies in Japan have been increasingly interested in “health and productivity management (H&PM).” In terms of H&PM, we hypothesized that companies can enhance their employees’ perceived workplace health support (PWHS) by supporting workers’ lively working and healthy living. This could then improve their health‐related quality of life (HRQOL) by increasing PWHS. Consequently, this study explored the relationship between PWHS and HRQOL.

Methods

In December 2020, during the COVID‐19 pandemic, we conducted an Internet‐based nationwide health survey of Japanese workers (CORoNaWork study). A database of 27 036 participants was created. The intensity of PWHS was measured using a four‐point Likert scale. We used multilevel ordered logistic regression to analyze the relationship between PWHS intensity and the four domains of the Centers for Disease Control's HRQOL‐4 (self‐rated health, number of poor physical health days, number of poor mental health days, and activity limitation days during the past 30 days).

Results

In the sex‐ and age‐adjusted and multivariate models, the intensity of PWHS significantly affected self‐rated health and the three domains of unhealthy days (physical, mental, and activity limitation). There was also a trend toward worse HRQOL scores as the PWHS decreased.

Conclusions

We found that the higher the PWHS of Japanese workers, the higher their self‐rated health and the fewer their unhealthy days. Companies need to assess workers’ PWHS and HRQOL and promote H&PM. H&PM is also necessary to maintain and promote the health of workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Keywords: COVID‐19, health and productivity management, health‐related quality of life, perceived workplace health support

1. INTRODUCTION

Japan is facing a decline in workers, an aging population, and reduced productivity. 1 To solve these problems, companies should be proactively involved in maintaining and promoting the health of their employees. In recent years, many companies have become more interested in “health and productivity management” (H&PM), an employee health management approach from a corporate management perspective, and have strategically promoted it. 2 , 3 , 4

To promote H&PM, companies should both reinforce workplace health support and consider how workers perceive their efforts. The concept of perceived organizational support (POS) is known as workers’ expression of evaluations and perceptions of the organization. POS was proposed by Eisenberger et al. in 1986 and is defined as "global beliefs concerning the extent to which the organization values their contributions and cares about their well‐being." 4 , 5 In terms of H&PM, we believe that companies can enhance their employees’ perceived workplace health support (PWHS) by providing support for workers’ lively working and healthy living. Prior studies have reported that PWHS can be measured by employees’ POS for ensuring healthy living and engagement in physical activity. 6

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic has had a greater impact on workers’ physical and mental health due to changes in work practices, including infection prevention, than the acute respiratory symptoms caused by the infection. 7 , 8 During the COVID‐19 pandemic, a high proportion of people have experienced mental and emotional deterioration, and these adverse psychological effects are associated with physical and social inactivity, poor sleep quality, and unhealthy eating habits. 9 , 10 These effects will be reflected in their Quality of life (QOL), which usually includes subjective evaluations of positive and negative aspects of life. 11 The current COVID‐19 pandemic may be negatively impacting workers’ QOL in the health‐related domain and reduce their productivity at work. Maintaining or improving health‐related QOL (HRQOL) through workplace health support may be important.

Few studies have focused on PWHS, and none have examined the relationship between PWHS and HRQOL. We focused on these to clarify the relationship between PWHS and workers’ health status by using a large‐scale internet survey of workers conducted during the COVID‐19 pandemic (December 2020).

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and setting

The research group from the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan, conducted a prospective cohort study called Collaborative Online Research on Novel‐coronavirus and Work study (CORoNaWork study). This study was a self‐administrated questionnaire survey conducted by a Japanese online survey company (Cross Marketing Inc. Tokyo), and a baseline survey was conducted from December 22 to 25, 2020. This study design is a cross‐sectional study using a part of a baseline survey of the CORoNaWork study. Fujino et al. 12 introduced the details of this study protocol.

2.2. Participants

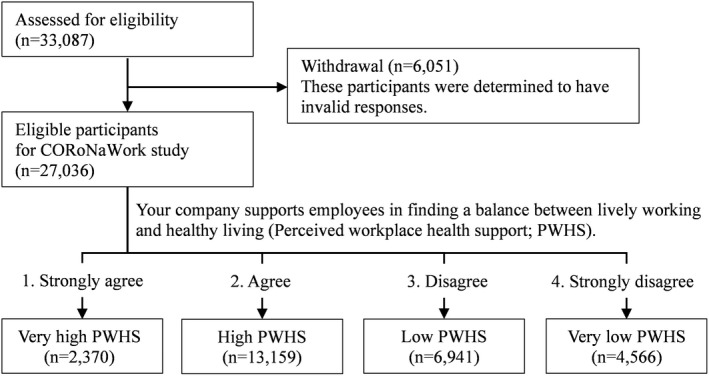

During the baseline survey, participants were between 20 and 65 years of age and working. A total of 33 087 participants, stratified by sex, age, region, and occupation using cluster sampling, participated in the CORoNaWork study. A database of 27 036 participants was created by excluding 6051 participants with invalid responses (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of this study population selection

2.3. Questionnaires

The questionnaire items used in this study are described in detail by Fujino et al. 12 We used data on sex, age, educational background, presence of illnesses that require hospital treatment, employment status, size of the company where the participants work, working hours per day, and work‐related data.

One measure of HRQOL is the HRQOL‐4 developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; hereafter CDC HRQOL‐4). 13 , 14 It collects self‐rated health status by asking about the following four domains: (a) self‐rated health (five‐Point Likert Scale: 1. excellent; 2. very good; 3. good; 4. fair; 5. poor), (b) the number of physically unhealthy days in the past 30 days, (c) the number of mentally unhealthy days in the past 30 days, and (d) the number of days with activity limitation in the past 30 days. 13 The CDC HRQOL‐4 instrument is free for public use, is not copyrighted and does not require permission for use or licensing fees. The CDC HRQOL‐4 tool was translated from English into Japanese by a Japanese epidemiologist and an occupational physician. A Japanese version of the CDC HRQOL‐4 has also been developed, and several previous studies have been conducted on Japanese workers using the same tool. 15 , 16 Previous studies have reported that the Japanese version of the HRQOL shows good concurrent validity with the Short Form‐8, a widely used indicator of HRQOL in Japan, and the work functioning impairment scale (WFun), an indicator of the worker's functional disability at work due to health problems that has good construct validity among Japanese workers. 15 The forward translations were reconciled. After that, the back translation was performed by a native English‐speaking researcher to ensure the equivalence between the original English version and the Japanese translated version. No conceptual or contextual differences from the original English version were found. 11 HRQOL is very simple and can be evaluated with only four questions, so it is easy for participants to answer. 15 Because the questions can be administered within one minute, this tool is very useful, especially for Internet surveys. In terms of reliability, Cronbach's alpha for three of the four CDC HRQOL‐4 items in the present sample was .84, which is greater than the minimal standard (.70) recommended for internal consistency reliability. 17 In this study, we used this tool to investigate the relationship between PWSH HRQOL.

The original question regarding the intensity of PWHS, "Your company supports lively working and healthy living for employees," was asked to participants using a four‐point Likert scale: strongly agree (very high PWHS), agree (high PWHS), disagree (low PWHS), and strongly disagree (very low PWHS).

2.4. Variables

The self‐rated health score, the number of physically unhealthy days in the past 30 days, the number of mentally unhealthy days in the past 30 days, and the number of days with activity limitation in the past 30 days collected using CDC HRQOL‐4 were used as outcome variables.

According to the intensity of PWHS, we divided the participants into four groups: very high, high, low, and very low (Figure 1). These variables were used as exposure variables.

The following items, surveyed using a questionnaire, were used as confounding factors. Sex, age (20–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, and ≥60 years), educational background (junior or senior high school, junior college or vocational school, university or graduate school), and presence of illnesses that require hospital treatment were personal characteristics. Employment status (regular employees, managers, executives, public service workers, temporary workers, freelancers or professionals, others), size of the company where the participants work (≤9 employees, 10–49, 50–99, 100–499, 500–999, 1000–9999, ≥10 000), and working hours per day (<8 h/day, 8≤ and <9 h/day, 9≤ and <11 h/day, ≥11 h/day) were used as work‐related factors.

2.5. Statistical method

To analyze the relationship between the four groups of PWHS and the four domains of CDC HRQOL, we used multilevel ordered logistic regression (OLR) with the two models nested in the prefecture of residence as random effects. In the sex‐age‐adjusted model multilevel OLR, we added sex and age as fixed effects. In the multivariate model, we added variables related to educational background, presence of illnesses that require hospital treatment, employment status, size of the company where the participants work, and working hours per day as fixed effects. In all tests, the threshold for significance was set at P < .05. Stata/SE Ver.15.1 (StataCorp LLC) was used for the analysis.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Participants and descriptive data

According to the PWHS scores, there were 2370 participants with very high PWHS, 13 159 with high PWHS, 6941 with low PWHS, and 4566 with very low PWHS (Figure 1).

Male participants had a lower proportion of very high PWHS and a higher proportion of very low PWHS than female participants. In participants of 20–29 years and ≥60 years, the proportion of very high PWHS was high, whereas those of 40–49 years and 50–59 years showed a high proportion of very low PWHS. The proportion of participants with illnesses who required hospital treatment tended to be higher in the group with very low PWHS. For work‐related factors, very high PWHS was high among participants who worked at a company size of ≥10 000 employees and those who worked <8 h/day. In contrast, the proportion of very low PWHS was higher among those who worked at a company size of ≤99 employees and those who worked ≥9 h/day (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Participants’ characteristics by groups according to perceived workplace health support

| Items | Total | Groups according to perceived workplace health support | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very high | High | Low | Very low | ||

| n (%)/Mean (SD) | n (%)/Mean (SD) | n (%)/Mean (SD) | n (%)/Mean (SD) | n (%)/Mean (SD) | |

| N | 27 036 (100.0) | 2370 (100.0) | 13 159 (100.0) | 6941 (100.0) | 4566 (100.0) |

| Sex, male | 13 814 (51.1) | 1100 (46.4) | 6772 (51.5) | 3519 (50.7) | 2423 (53.1) |

| Age | |||||

| 20–29 years | 1905 (7.0) | 217 (9.2) | 993 (7.5) | 482 (6.9) | 213 (4.7) |

| 30–39 years | 4858 (18.0) | 448 (18.9) | 2295 (17.4) | 1328 (19.1) | 787 (17.2) |

| 40–49 years | 8011 (29.6) | 663 (28.0) | 3683 (28.0) | 2192 (31.6) | 1473 (32.3) |

| 50–59 years | 9012 (33.3) | 727 (30.7) | 4441 (33.7) | 2205 (31.8) | 1639 (35.9) |

| ≥60 years | 3250 (12.0) | 315 (13.3) | 1747 (13.3) | 734 (10.6) | 454 (9.9) |

| Educational background | |||||

| Junior or senior high schools | 7321 (27.1) | 593 (25.0) | 3294 (25.0) | 1948 (28.1) | 1486 (32.5) |

| Junior college or vocational school | 6544 (24.2) | 557 (23.5) | 3066 (23.3) | 1727 (24.9) | 1194 (26.1) |

| University or graduate school | 13 171 (48.7) | 1220 (51.5) | 6799 (51.7) | 3266 (47.1) | 1886 (41.3) |

| Presence of illnesses that require hospital treatment | 9510 (35.2) | 789 (33.3) | 4541 (34.5) | 2377 (34.2) | 1803 (39.5) |

| Employment status | |||||

| Regular employees | 12 575 (46.5) | 936 (39.5) | 5772 (43.9) | 3598 (51.8) | 2269 (49.7) |

| Managers | 2541 (9.4) | 217 (9.2) | 1408 (10.7) | 592 (8.5) | 324 (7.1) |

| Executives | 862 (3.2) | 150 (6.3) | 534 (4.1) | 121 (1.7) | 57 (1.2) |

| Public service worker | 2810 (10.4) | 231 (9.7) | 1551 (11.8) | 690 (9.9) | 338 (7.4) |

| Temporary workers | 2894 (10.7) | 196 (8.3) | 1432 (10.9) | 798 (11.5) | 468 (10.2) |

| Freelances or professionals | 4454 (16.5) | 524 (22.1) | 2082 (15.8) | 962 (13.9) | 886 (19.4) |

| Others | 900 (3.3) | 116 (4.9) | 380 (2.9) | 180 (2.6) | 224 (4.9) |

| Company size | |||||

| ≤9 employees | 6165 (22.8) | 697 (29.4) | 2841 (21.6) | 1292 (18.6) | 1335 (29.2) |

| 10–49 employees | 4390 (16.2) | 323 (13.6) | 1950 (14.8) | 1254 (18.1) | 863 (18.9) |

| 50–99 employees | 2550 (9.4) | 156 (6.6) | 1144 (8.7) | 754 (10.9) | 496 (10.9) |

| 100–499 employees | 5156 (19.1) | 349 (14.7) | 2514 (19.1) | 1486 (21.4) | 807 (17.7) |

| 500–999 employees | 1997 (7.4) | 167 (7.0) | 991 (7.5) | 557 (8.0) | 282 (6.2) |

| 1000–9999 employees | 4719 (17.5) | 424 (17.9) | 2549 (19.4) | 1167 (16.8) | 579 (12.7) |

| ≥10 000 employees | 2059 (7.6) | 254 (10.7) | 1170 (8.9) | 431 (6.2) | 204 (4.5) |

| Working hours per day | |||||

| <8 h/day | 5334 (19.7) | 589 (24.9) | 2678 (20.4) | 1176 (16.9) | 891 (19.5) |

| 8≤ and <9 h/day | 14 848 (54.9) | 1263 (53.3) | 7344 (55.8) | 3885 (56.0) | 2356 (51.6) |

| 9≤ and <11 h/day | 5541 (20.5) | 413 (17.4) | 2603 (19.8) | 1564 (22.5) | 961 (21.0) |

| ≥11 h/day | 1313 (4.9) | 105 (4.4) | 534 (4.1) | 316 (4.6) | 358 (7.8) |

| CDC‐HRQOL | |||||

| Self‐rated health | 3.48 (0.93) | 2.98 (1.08) | 3.34 (0.87) | 3.65 (0.85) | 3.87 (0.95) |

| Physically unhealthy days (# days) | 4.22 (7.44) | 3.44 (6.89) | 3.28 (6.43) | 4.41 (7.23) | 7.03 (9.67) |

| Mentally unhealthy days (# days) | 4.11 (7.70) | 2.97 (6.75) | 2.87 (6.19) | 4.38 (7.56) | 7.85 (10.55) |

| Days with activity limitation (# days) | 2.37 (5.74) | 1.97 (5.27) | 1.68 (4.54) | 2.43 (5.52) | 4.49 (8.29) |

Abbreviation: CDC HRQOL, Centers for Disease Control's Prevention Health‐Related Quality of Life.

3.2. Score comparison of the CDC HRQOL‐4 (Japanese version) between groups according to PWHS

In the CDC HRQOL‐4, the mean score (SD) of self‐rated health of the very low PWHS group was the highest at 3.87 (0.95), and the very high PWHS group had the lowest score at 2.98 (1.08). The mean score (SD) of each of the number of physically unhealthy days, the number of mentally unhealthy days, and the number of days with activity limitation was the highest for the very low PWHS group at 7.03 (9.67), 7.85 (10.55), and 4.49 (8.29), respectively, and the lowest for the high PWHS group at 3.28 (6.43), 2.87 (6.19), and 1.68 (4.54), respectively (Table 1).

We statistically compared each score of the four CDC HRQOL‐4 domains between the PWHS groups (Table 2). In the sex‐age‐adjusted and multivariate‐adjusted model, the PWHS group significantly affected self‐rated health; specifically, the self‐rated health score was significantly lower (i.e., the participant had a more favorable self‐rated health status) in the groups with higher PWHS.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of the scores of the CDC HRQOL among groups according to perceived workplace health support (PWHS)

| Parameters | Groups according to PWHS | Sex‐age‐adjusted | Multivariate a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | 95% CI | P | Coefficient | 95% CI | P | ||

| Self‐rated health | Very high | 0.15 | 0.13–0.16 | <.01 | 0.15 | 0.13–0.16 | <.01 |

| High | 0.30 | 0.28–0.32 | <.01 | 0.31 | 0.28–0.32 | <.01 | |

| Low | 0.58 | 0.54–0.62 | <.01 | 0.60 | 0.54–0.62 | <.01 | |

| Very low | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Physically unhealthy days (# days) | Very high | 0.39 | 0.35–0.43 | <.01 | 0.41 | 0.35–0.43 | <.01 |

| High | 0.44 | 0.41–0.47 | <.01 | 0.46 | 0.41–0.47 | <.01 | |

| Low | 0.64 | 0.59–0.68 | <.01 | 0.67 | 0.59–0.68 | <.01 | |

| Very low | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Mentally unhealthy days (# days) | Very high | 0.28 | 0.25–0.30 | <.01 | 0.29 | 0.25–0.30 | <.01 |

| High | 0.34 | 0.32–0.36 | <.01 | 0.35 | 0.32–0.36 | <.01 | |

| Low | 0.54 | 0.50–0.58 | <.01 | 0.56 | 0.50–0.58 | <.01 | |

| Very low | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Days with activity limitation (# days) | Very high | 0.42 | 0.38–0.47 | <.01 | 0.44 | 0.38–0.47 | <.01 |

| High | 0.45 | 0.41–0.47 | <.01 | 0.46 | 0.41–0.47 | <.01 | |

| Low | 0.65 | 0.60–0.70 | <.01 | 0.67 | 0.60–0.70 | <.01 | |

| Very low | Reference | Reference | |||||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; PWHS, perceived workplace health support.

The multivariate model was adjusted for sex, age, educational background, presence of illnesses that require hospital treatment, employment status, company size, and working hours per day.

In the sex‐age‐adjusted and multivariate‐adjusted model, the PWHS groups were significantly affected in each of the three domains of the number of physically unhealthy days, the number of mentally unhealthy days, and the number of days with activity limitation (Table 2). The very low PWHS group had considerably higher values in the three domains of unhealthy days than the other three groups (P < .01). We observed that the values of the three domains of unhealthy days of the low PWHS group tended to be higher than those of the very high and high PWHS groups.

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we analyzed the relationship between PWHS and HRQOL. We found that PWHS considerably impacted the following four domains of CDC HRQOL‐4: self‐rated health, the number of physically unhealthy days, the number of mentally unhealthy days, and the number of days with activity limitation. In particular, the impact tended to be stronger in the group with lower PWHS. Absenteeism (the absence of a worker from work due to health problems) and presenteeism (there are several definitions, but the two main are sickness presenteeism, which is working while sick and productivity loss that stems from being at work while ill, and decreasing performance) are well‐known indicators of the health status of workers. 18 , 19 Regarding the relationship between PWHS and indicators of absenteeism and presenteeism on productivity loss, Chen et al. have reported that presenteeism differs substantially by PWHS level. People with lower PWHS had higher presenteeism than those with higher PWHS, and higher PWHS was independently associated with higher work productivity. 6 In contrast, another study stated that PWHS, as a workplace culture fostering a healthy lifestyle and physical activity, was found to influence absenteeism and presenteeism through the mediation of anxiety and depressive symptoms. 20 This study is consistent with previous reports and found that, with a decrease in PWHS, self‐rated health status worsens and unhealthy days increase.

In this study, the group with very low PWHS had a higher proportion of participants with illnesses who required hospital treatment and those who had working hours of ≥9 h/day than the other three groups. The companies committed to H&PM could implement workplace health promotion programs for primary prevention 21 or proper working hour management to prevent various diseases associated with long working hours. 22 Workplace elements such as environmental and policy support may be associated with a marginally significant lower lifestyle risk. 23 We believe that PWHS must be improved by promoting H&PM, as low PWHS may hinder workers’ health. As for the relationship between actual health support at the company and employees’ perception of it, previous studies have shown that a short exercise program during breaks improves work engagement and WFun "vitality" values. 24 Furthermore, employees who had undergone a stress check program in Japan followed by improvements to the work environment showed improvements in their psychological stress response. 25 When companies actively provide health support, the employees’ PWSH and HRQOL improve. Therefore, we believe that strong organizational support from companies is necessary to improve HRQOL.

This study was conducted in December 2020, during the COVID‐19 pandemic; consequently, the psychological impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic may have worsened the health status of individuals. This study suggests that efforts to improve PWHS in companies could help reduce health deterioration even during the pandemic because of the relationship between PWHS and self‐rated health or unhealthy days. In a study on occupational health, safety policies, and the perceived support from the organization, supervisors, and coworkers in a petrochemical company, perceived supervisor support was reported to have significantly influenced workers’ compliance behavior. 26 We speculate that, by increasing PWHS, workers’ awareness of preventive behaviors against COVID‐19 infection can be improved.

As mentioned above, PWHS is related to the health status of workers, so H&PM with higher PWHS must be promoted. We believe that assessing the PWHS of workers is effective in confirming the degree of H&PM promotion. Additionally, HRQOL‐4 may be a plausible tool for health management in the workplace.

4.1. Limitation

This study has three limitations. First, this is an Internet‐based survey, so the generalizability of the results is uncertain. However, to reduce sampling bias, sampling was conducted across sex, generation, personal characteristics, and occupation. Second, because this was a cross‐sectional study, causality between PWHS and HRQOL could not be confirmed. However, based on previous studies reporting that lower PWHS affects presenteeism, 6 , 20 we believe that it is likely that lower PWHS leads to lower HRQOL. Third, because this study was conducted during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Japan, the participants’ awareness of PWHS and HRQOL differed between the present and regular times. Therefore, because of the possible health concerns associated with the COVID‐19 pandemic, further studies are needed.

5. CONCLUSION

In this study, we investigated the relationship between PWHS and HRQOL. We found that the higher the PWHS of Japanese workers, the higher their self‐rated health and the fewer their unhealthy days. We believe that it is significant for companies to assess the PWHS and HRQOL of their workers to promote H&PM, as it is vital for maintaining and promoting workers’ health during the COVID‐19 epidemic.

DISCLOSURE

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan (reference No. R2‐079). Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained in the form of the website. Registry and the registration no. of the study/trial: N/A. Animal studies: N/A. Conflict of interest: Authors declare no conflicts of interest for this study.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Kazushirou Kurogi wrote the manuscript and analyzed the data; Kazunori Ikegami reviewed the manuscript, created the questionnaire, analyzed the data, and provided advice on interpretation; Akira Ogami reviewed the manuscript, analyzed the data, and provided advice on interpretation; Hisashi Eguchi, Mayumi Tsuji, Seiichiro Tateishi, Tomohisa Nagata, Shinya Matsuda reviewed the manuscript; Yoshihisa Fujino reviewed the manuscript and contributed to the overall survey planning, creating the questionnaire, and securing funding for research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The current members of the CORoNaWork Project, in alphabetical order, are as follows: Dr. Yoshihisa Fujino (present chairperson of the study group), Dr. Akira Ogami, Dr. Arisa Harada, Dr. Ayako Hino, Dr. Hajime Ando, Dr. Hisashi Eguchi, Dr. Kazunori Ikegami, Dr. Kei Tokutsu, Dr. Keiji Muramatsu, Dr. Koji Mori, Dr. Kosuke Mafune, Dr. Kyoko Kitagawa, Dr. Masako Nagata, Dr. Mayumi Tsuji, Ms. Ning Liu, Dr. Rie Tanaka, Dr. Ryutaro Matsugaki, Dr. Seiichiro Tateishi, Dr. Shinya Matsuda, Dr. Tomohiro Ishimaru, and Dr. Tomohisa Nagata. All members are affiliated with the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan. This study was supported and partly funded by the research grant from the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan (no grant number); Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (H30‐josei‐ippan‐002, H30‐roudou‐ippan‐007, 19JA1004, 20JA1006, 210301‐1, and 20HB1004); Anshin Zaidan (no grant number), the Collabo‐Health Study Group (no grant number), and Hitachi Systems Ltd (no grant number) and scholarship donations from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd (no grant number).

Kurogi K, Ikegami K, Eguchi H, et al; CORoNaWork Project . A cross‐sectional study on perceived workplace health support and health‐related quality of life. J Occup Health. 2021;63:e12302. doi: 10.1002/1348-9585.12302

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Due to the nature of this research, the participants of this study did not agree to their data being publicly shared, and hence, supporting data were not available.

REFERENCES

- 1. Statistics Bureau of Japan . Statistical Handbook of Japan 2019. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/handbook/c0117.html [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry . Enhancing health and productivity management. Accessed April 21, 2021. https://www.meti.go.jp/policy/mono_info_service/healthcare/downloadfiles/180717health‐and‐productivity‐management.pdf

- 3. Mori K, Nagata T, Nagata M, et al. Development, success factors, and challenges of government‐led health and productivity management initiatives in japan. J Occup Environ Med. 2021;63(1):18‐26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eisenberger R, Huntington R, Hutchison S, Sowa D. Perceived organizational support. J Appl Psychol. 1986;71(3):500. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Allen DG, Shore LM, Griffeth RW. The role of perceived organizational support and supportive human resource practices in the turnover process. J Management. 2003;29(1):99‐118. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen L, Hannon PA, Laing SS, et al. Perceived workplace health support is associated with employee productivity. Am J Health Promot. 2015;29(3):139‐146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vindegaard N, Benros ME. COVID‐19 pandemic and mental health consequences: systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;89:531‐542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Giorgi G, Lecca LI, Alessio F, et al. COVID‐19‐related mental health effects in the workplace: a narrative review. Int J Env Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):7857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ammar A, Trabelsi K, Brach M, et al. Effects of home confinement on mental health and lifestyle behaviours during the COVID‐19 outbreak: insights from the ECLB‐COVID19 multicentre study. Biol Sport. 2021;38(1):9‐21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ammar A, Brach M, Trabelsi K, et al. Effects of COVID‐19 home confinement on eating behaviour and physical activity: results of the ECLB‐COVID19 international online survey. Nutrients. 2020;12(6):1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Whoqol Group . The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(10):1403‐1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fujino Y, Ishimaru T, Eguchi H, et al. Protocol for a nationwide internet‐based health survey of workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic in 2020. J UOEH. 2021;43(2):217‐225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Measuring healthy days. Accessed April 23, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/methods.htm

- 14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Measuring healthy days. Accessed May 19, 2021. http://www.cdc.gov/hrqol

- 15. Chimed‐Ochir O, Mine Y, Okawara M, Ibayashi K, Miyake F, Fujino Y. Validation of the Japanese version of the CDC HRQOL‐4 in workers. J Occup Health. 2020;62(1):e12152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chimed‐Ochir O, Mine Y, Fujino Y. Pain, unhealthy days and poor perceived health among Japanese workers. J Occup Health. 2020;62(1):e12092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bland JM, Altman DG. Cronbach’s alpha (statistics notes). Br Med J. 1997;314:572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gosselin E, Lemyre L, Corneil W. Presenteeism and absenteeism: differentiated understanding of related phenomena. J Occup Health Psychol. 2013;18(1):75‐86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Johns G. Presenteeism in the workplace: a review and research agenda. J Organ Behavior. 2010;31(4):519‐542. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Laing SS, Jones SM. Anxiety and depression mediate the relationship between perceived workplace health support and presenteeism: a cross‐sectional analysis. J Occup Environ Med. 2016;58(11):1144‐1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Goetzel RZ, Ozminkowski RJ. Health and productivity management: emerging opportunities for health promotion professionals for the 21st century. Am J Health Promot. 2000;14(4):211‐214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bannai A, Tamakoshi A. The association between long working hours and health: a systematic review of epidemiological evidence. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2014;40(1):5‐18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Payne J, Cluff L, Lang J, Matson‐Koffman D, Morgan‐Lopez A. Elements of a workplace culture of health, perceived organizational support for health, and lifestyle risk. Am J Health Promot. 2018;32(7):1555‐1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Michishita R, Jiang Y, Ariyoshi D, et al. The introduction of an active rest program by workplace units improved the workplace vigor and presenteeism among workers: a randomized controlled trial. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(12):1140‐1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Imamura K, Asai Y, Watanabe K, et al. Effect of the National Stress Check Program on mental health among workers in Japan: a 1‐year retrospective cohort study. J Occup Health. 2018;60(4):298‐306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Puah LN, Ong LD, Chong WY. The effects of perceived organizational support, perceived supervisor support and perceived co‐worker support on safety and health compliance. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2016;22(3):333‐339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the nature of this research, the participants of this study did not agree to their data being publicly shared, and hence, supporting data were not available.