Abstract

Rotavirus G and P types from 716 children with acute diarrhea in Dijon from 1995 to 1998 and throughout France during the winter of 1997-1998 were analyzed by reverse transcription-PCR. P[8],G1 predominated, followed by P[8],G4, which emerged during the last winter. G9 and P[6] strains were detected at low frequencies.

Group A rotavirus is the major etiologic agent of acute gastroenteritis in children worldwide. The two outer capsid proteins define two different serotype specificities: G types are determined by VP7 (gene 9), and P types are determined by VP4 (gene 4) (6). Genotyping methods are sensitive for strain typing, notably for P typing (11), and epidemiological studies conducted worldwide have shown that the majority of strains were P[8],G1; P[4],G2; P[8],G3; and P[8],G4 (9). However, other G serotypes have now been found to be common in several regions of the world, notably, serotypes G5, G8, and G10 in Brazil (18; V. Gouvea and N. Santos, Letter, Vaccine 17:1291–1292, 1999); G8 in Malawi (4); and G9 in India (16) and in the United States (17). Since the role of heterotypic protection is not yet clear, strain typing is important from the perspective of introducing polyvalent vaccines.

In France, there is no national strain surveillance system, and few data are available concerning rotavirus type circulation. A recent study conducted in one hospital in Paris (7) during a 1-year survey (1997-1998) reported that 98% of 170 rotavirus isolates were G1 to G4, with type G4 predominating (60%). Here, we report strain typing results obtained in one city (Dijon) over a 3-year period (1995 to 1998) and in 15 other cities distributed throughout France during the 1997-1998 rotavirus season. We showed that the P[8],G1 type was predominant and that the P[8],G4 type has emerged during this period to become very common during the winter of 1997-1998. Furthermore, unusual strains such as G9 and P[6] could be detected at low frequencies.

Rotavirus isolates recovered from 218 children with acute gastroenteritis in a previous study in Dijon from December 1995 to February 1998 (3) were first analyzed. In addition, 498 stool specimens, selected randomly among 645 specimens provided by 15 hospital-based laboratories from November 1997 to May 1998, were further typed. These laboratories, recruited for their geographic representativeness, were distributed in five regions: northeastern (three hospitals), northwestern (four), southeastern (three), southwestern-central (three), and Paris (two). To these 498 specimens were added, for analysis of the 1997-1998 rotavirus season, 55 isolates previously typed in Dijon (northeastern region); thus, a total of 553 specimens were included. The goal of the selection was to type about 120 isolates from each region and 60 from Paris. All the samples were from children with community-acquired gastroenteritis, and when hospitalization was required, stool specimens were collected within 48 h to exclude nosocomial infections. Fecal specimens were shipped to our laboratory in dry ice and were stored at −40°C until they were analyzed. Rotavirus RNA was extracted from 10 to 20% fecal suspensions in phosphate-buffered saline using the QIA Amp viral RNA kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. G types were identified by multiplex reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) assay using primers Beg9 and End9 and, for typing, RVG9 and the G1(aBT1), G2(aCT2), G3(aET3), and G4(aDT4) primers (10). Specimens that could not be typed were further assayed with primers G8(aAT8) and G9(aFT9) (10) or G9(9T-9B) (5). P types were identified by multiplex RT-PCR assay using primers con3 and con2 and, for typing, con3 and the P[8](1-T1), P[4](2-T1), and P[6](3-T1) primers (8). The amplified products were detected by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel containing 0.5 μg of ethidium bromide per ml. For specimens not amplified by RT-PCR, a confirmatory enzyme immunoassay (EIA) was done as previously described (15). RNAs extracted from some specimens were resolved on a 10% polyacrylamide discontinuous gel and stained with ethidium bromide. Nucleotide sequencing of gene 9, for some PCR products, was carried out with the ABI Prism BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit on an automated sequencer (model 373A; Perkin-Elmer). Statistical analysis was performed with EPI-INFO version 6.02 software (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga., and World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 1994). Distributions of rotavirus types by geographic area were compared by chi-square test. All tests were two-tailed, and P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

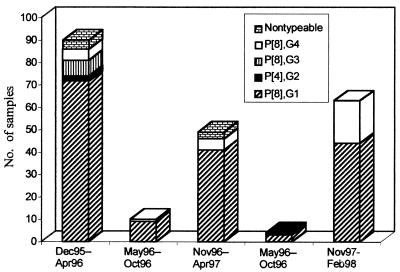

The mean and median ages of the 218 children with acute gastroenteritis in Dijon from December 1995 to February 1998 were 10.2 and 7.5 months, respectively (range, 0.2 to 107.7 months; standard deviation, 11.4). Strain P[8],G1 was predominant (169 of 218 [77.5%]). Among the P[8],G1 isolates, three samples which could not be G typed by RT-PCR were found to be G1 type by gene 9 sequencing (unpublished data). The next most common strain was P[8],G4 (30 of 218 [13.8%]); strains P[8],G3 and P[4],G2 were less common (7 and 3 of 218, respectively [3.2 and 1.4%, respectively]). Dual infections with P[8],G1 and P[8],G4 were found in two specimens (0.9%). Seven isolates (3.2%) were nontypeable; all were antigen positive by EIA, but one could not be amplified and six could not be G typed. The temporal distribution of rotavirus types in Dijon during the 3-year period is represented in Fig. 1. The results show the emergence of the G4 type during the last period of the study (32.1% for the period from December 1997 to February 1998 compared to 3.1 and 3.3% for the same periods in the two preceding years) and the disappearance of the P[8],G3 type since 1996.

FIG. 1.

Temporal distribution of rotavirus types in Dijon over the 3-year period from December 1995 to February 1998.

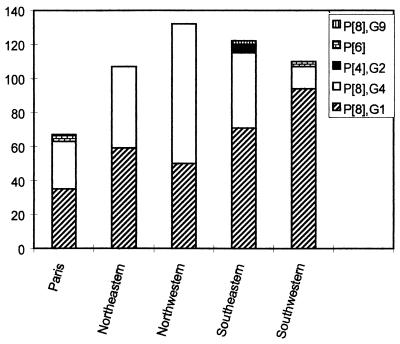

The mean and median ages of the 553 children with acute gastroenteritis throughout France from November 1997 to May 1998 were 11.2 and 9 months, respectively (range, 0.1 to 135.1 months; standard deviation, 12.8). The P[8],G1 strain was predominant (309 of 553 [55.9%]), followed by P[8],G4 (215 of 553 [38.9%]). These two strains represented 94.8% of the isolates. Other strains were detected at low frequencies: P[4],G2, another conventional strain (5 of 553 [0.9%]), and unusual strains (14 of 553 [2.5%]). The latter were distributed as follows: P[4],G1 and P[8],G2 (4 and 1 of 553 [0.7 and 0.2%, respectively]), P[6],G1 and P[6],G2 (4 and 3 of 553, respectively, which gives a total of 7 P[6] strains [1.3%]); and P[8],G9 (2 of 553 [0.4%]). The P[6] strains were detected in three cities: Paris (three G2 strains), Limoges (three G1 strains), and Clermont-Ferrand (one G1 strain). The two G9 strains detected in the same city (St.-Etienne) were amplified not by the G9(FT9) primer (10) but by the G9(9T-9B) primer (5). They had a long electropherotype (data not shown). Nucleotide sequencing of gene 9 for these two isolates showed the same sequence and confirmed the G9 type (unpublished data). Dual infections were found in 0.4% of samples (2 of 553). Finally, eight isolates (1.4%) that were antigen positive by EIA could not be amplified by RT-PCR. Comparison of the distribution of P[8],G1 and P[8],G4 strains according to age showed no statistically significant difference. The geographic distribution of rotavirus types (Fig. 2) showed differences between some regions: the P[8],G1 strain was less frequent in the northwestern region and more frequent in the southwestern-central region than in the other regions; at the opposite extreme, P[8],G4 was more frequent in the northwestern region and less frequent in the southwestern-central region.

FIG. 2.

Geographic distribution of rotavirus types P[8],G1; P[8],G4; P[4],G2; P[6]; and G9 during the 1997-1998 rotavirus season.

The results obtained here showed that P[8],G1 predominated in Dijon from 1995 to 1998, as well as throughout France during the 1997-1998 rotavirus season. This result is consistent with numerous previous studies (9). The next most common type was P[8],G4, and the 3-year survey in Dijon showed clearly that this type emerged during the winter of 1997-1998. The predominance of type G4 has been reported in France in one hospital in Paris during the same period (7). In our study, either P[8],G1 or P[8],G4 was predominant according to the region. A high prevalence of the G4 type has already been found for several other countries in Europe: the United Kingdom (13), Finland (20), Italy (2), and, more recently, Ireland (14), where an increase in the prevalence of G4 isolates was observed during the winter of 1997-1998. The two other conventional strains, P[8],G3 and P[4],G2, were uncommon, and it is notable that P[8],G3 was not detected after 1996. We also identified (at low frequencies) unusual strains, among them the P[8],G9 type detected in two samples from the same city and the P[6] type in seven samples from three different cities, associated with G1 or G2 types. Such strains have now been reported for children with diarrhea in several studies in industrialized countries (1, 12, 17, 19). To our knowledge, G9 strains have not been previously described in Europe, whereas P[6] strains have been reported recently for the first time in Italy (1).

Finally, in addition to the results of strain typing, this study has allowed us to test a national strain surveillance system of collaborating laboratories.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant PHRC 1997 from the Ministry of Health and by the Programme de Recherche Fondamentale en Microbiologie et Maladies Infectieuses et Parasitaires (grant B02179, Ministry of Education and Research).

REFERENCES

- 1.Arista S, Vizzi E, Alaimo C, Palermo D, Cascio A. Identification of human rotavirus strains with the P[14] genotype by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2706–2708. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2706-2708.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arista S, Vizzi E, Ferraro D, Cascio A, Di Stefano R. Distribution of VP7 serotypes and VP4 genotypes among rotavirus strains recovered from Italian children with diarrhea. Arch Virol. 1997;142:2065–2071. doi: 10.1007/s007050050224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bon F, Fascia P, Dauvergne M, Tenenbaum D, Planson H, Petion A, Pothier P, Kohli E. Prevalence of group A rotavirus, human calicivirus, astrovirus, and adenovirus type 40 and 41 infections among children with acute gastroenteritis in Dijon, France. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3055–3058. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.9.3055-3058.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunliffe N A, Gondwe J S, Broadhead R L, Molyneux M E, Woods P A, Bresee J S, Glass R I, Gentsch J R, Hart C A. Rotavirus G and P types in children with acute diarrhea in Blantyre, Malawi, from 1997 to 1998: predominance of novel P[6]G8 strains. J Med Virol. 1999;57:308–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Das B K, Gentsch J R, Cicirello H G, Woods P A, Gupta A, Ramachandran M, Kumar R, Bhan M K, Glass R I. Characterization of rotavirus strains from newborns in New Delhi, India. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1820–1822. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.7.1820-1822.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Estes M K. Rotaviruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 1625–1655. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gault E, Chikhi-Brachet R, Delon S, Schnepf N, Albiges L, Grimprel E, Girardet J P, Begue P, Garbarg-Chenon A. Distribution of human rotavirus G types circulating in Paris, France, during the 1997-1998 epidemic: high prevalence of type G4. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2373–2375. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.7.2373-2375.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gentsch J R, Glass R I, Woods P, Gouvea V, Gorziglia M, Flores J, Das B K, Bhan M K. Identification of group A rotavirus gene 4 types by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1365–1373. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.6.1365-1373.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gentsch J R, Woods P A, Ramachandran M, Das B K, Leite J P, Alfieri A, Kumar R, Bhan M K, Glass R I. Review of G and P typing results from a global collection of rotavirus strains: implications for vaccine development. J Infect Dis. 1996;174(Suppl. 1):S30–S36. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.supplement_1.s30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gouvea V, Glass R I, Woods P, Taniguchi K, Clark H F, Forrester B, Fang Z Y. Polymerase chain reaction amplification and typing of rotavirus nucleic acid from stool specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:276–282. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.2.276-282.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masendycz P J, Palombo E A, Gorrell R J, Bishop R F. Comparison of enzyme immunoassay, PCR, and type-specific cDNA probe techniques for identification of group A rotavirus gene 4 types (P types) J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:3104–3108. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.12.3104-3108.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakagomi T, Horie Y, Koshimura Y, Greenberg H B, Nakagomi O. Isolation of a human rotavirus strain with a super-short RNA pattern and a new P2 subtype. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1213–1216. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.4.1213-1216.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noel J S, Beards G M, Cubitt W D. Epidemiological survey of human rotavirus serotypes and electropherotypes in young children admitted to two children's hospitals in northeast London from 1984 to 1990. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2213–2219. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.10.2213-2219.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Mahony J, Foley B, Morgan S, Morgan J G, Hill C. VP4 and VP7 genotyping of rotavirus samples recovered from infected children in Ireland over a 3-year period. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1699–1703. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1699-1703.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pothier P, Drouet E. Development and evaluation of a rapid one-step ELISA for rotavirus detection in stool specimens using monoclonal antibodies. Ann Virol Inst Pasteur. 1987;13:285–295. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramachandran M, Das B K, Vij A, Kumar R, Bhambal S S, Kesari N, Rawat H, Bahl L, Thakur S, Woods P A, Glass R I, Bhan M K, Gentsch J R. Unusual diversity of human rotavirus G and P genotypes in India. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:436–439. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.2.436-439.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramachandran M, Gentsch J R, Parashar U D, Jin S, Woods P A, Holmes J L, Kirkwood C D, Bishop R F, Greenberg H B, Urasawa S, Gerna G, Coulson B S, Taniguchi K, Bresee J S, Glass R I. Detection and characterization of novel rotavirus strains in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3223–3229. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3223-3229.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santos N, Lima R C, Pereira C F, Gouvea V. Detection of rotavirus types G8 and G10 among Brazilian children with diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2727–2729. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2727-2729.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santos N, Riepenhoff-Talty M, Clark H F, Offit P, Gouvea V. VP4 genotyping of human rotavirus in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:205–208. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.1.205-208.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vesikari T, Rautanen T, Von Bonsdorff C H. Rotavirus gastroenteritis in Finland: burden of disease and epidemiological features. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 1999;88:24–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1999.tb14322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]