Abstract

Introduction

This article explores one mental health company's urgent response to the global COVID‐19 pandemic, and the multifaceted implications of quickly transitioning to telehealth services.

Objectives

The purpose of this article is to share information with interdisciplinary professionals about the planning, implementation, and results of transitioning to telehealth services during a pandemic.

Procedures

We compiled practice‐related data regarding company attendance rates and customer and employee satisfaction with telehealth. Data include feedback from more than 40 clinicians and 60 families.

Results

The data suggest there are both benefits and limitations to engaging in telehealth services within a mental health company. Attendance rates increased dramatically, engagement improved with adolescents but proved challenging with the younger children. Telehealth helped overcome many typical barriers to mental health treatment. Concerns remain regarding confidentiality, assessment of abuse and neglect, and ability to read nonverbal social cues.

Conclusion

Families and practitioners experienced the convenience and benefits of telehealth but also expressed concerns over certain limitations. Finding a responsible way to incorporate telehealth into practice postpandemic is a priority for mental health practitioners, both now and in the immediate future.

Keywords: Covid‐19, outpatient mental health, telehealth

INTRODUCTION

As the Chief Executive Officer and founder of Cooperative Counseling Services (CCS), a child and adolescent mental health company in New Jersey and an emerging scholar pursuing my PhD in Family Science, I am respectfully sharing our company's experience with our recent and expedited transition to telehealth services in response to COVID‐19 pandemic. Despite the need to provide essential, uninterrupted mental health care during a global pandemic, we were concerned about providing on‐site, in‐person clinical services due to the potential impact of COVID‐19 on the health of our clients, their families, and our staff. Providing services through telehealth seemed our most prudent choice. However, there were several important considerations and challenges, including our lack of experience with telehealth services and existing state and federal restrictions on the use of telehealth. This Lesson From the Field is based on our experience transitioning our mental health services to telehealth under extreme circumstances. Included is our team's initial response to COVID‐19, reflections on the implications of telehealth on service delivery, and lessons learned from our experiences.

BACKGROUND

Theoretical framework

At CCS, relational developmental systems (RDS) theory informs our conceptualization of our clients, their families, and how we deliver services. RDS's emphasis on the mutually influential relations between the individual, family, and the larger environment exemplifies our approach to the therapeutic process (Overton, 2013). Understanding the individual in the context of their environment, their potential for change, and the recognition of the diversity of intraindividual change and interindividual differences is a fundamental part of our approach to the therapeutic relationship (Lerner, 2006). Additionally, a bioecological model framework allows us to understand our clients in the context of their proximal processes, the characteristics of their developing person, within their immediate and remote environmental contexts and the unique time period within which their proximal processes occur (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006).

Program description

CCS is a privately owned child and adolescent mental health care provider in New Jersey and provides outpatient mental health services in two urban clinic settings licensed by the New Jersey Department of Health. Outpatient services consist of biopsychosocial clinical intake assessments, individual and family sessions, psychiatric evaluations, and medication management. CCS also offers intensive in‐community (IIC) services for New Jersey's Children's System of Care in an effort to stabilize children in their home environment and decrease hospitalizations and out‐of‐home placements. IIC services are conducted primarily in the home and use clinical strategies to stabilize the child in the home environment. CCS serves children and adolescents from ages 3 to 21 years in both programs, and our clients present with a wide range of psychosocial challenges and mental health diagnoses. Currently, CCS is providing clinical services to approximately 1000 children and adolescents, and their families.

Client demographics

Approximately 15% of New Jersey's children under 18 years of age live below the poverty level, and more than 18% report an emotional, behavioral, or developmental condition (Kids Count Data Center, 2020a, 2020b). Sixteen percent of New Jersey's children have reported two or more adverse experiences, including frequent economic hardship, parental divorce or separation, parental death, parental incarceration, family violence, neighborhood violence, living with a mentally ill or suicidal family member, or living with someone who uses substances (Kids Count Data Center, 2020c). Annually, approximately 77,000 of New Jersey's children were subject to a substantiated or indicated maltreatment report (Kids Count Data Center, 2020d).

Ninety‐eight percent of CCS clients are Medicaid recipients and are living at or below the poverty level. More than half of the families served have current or prior Child Protection and Permanency involvement. The majority of our clients speak English, but approximately 25% of the families require Spanish‐ or Portuguese‐speaking clinicians. CCS provides weekly individual and family clinical sessions. When medication is prescribed, in addition to medication management sessions, clinical therapy is a recommended component of care. Due to the age of our population CCS underscores the importance of family engagement and family therapy is conducted in conjunction with individual therapy in most instances.

Many of the children who are referred to CCS for outpatient mental health services have complex needs that span beyond their individual mental health needs. In addition to living in poverty, and experiencing maltreatment, subsequent investigations and interventions with Child Protection and Permanency, some children struggle in school, combat racism, experience anxiety due to the legal status of their family members and have parents with significant mental health needs. The impact of these additional stressors on their mental health informs CCS' clinical strategies and interventions throughout treatment.

Community mental health challenges

Families living in poverty have a significantly higher likelihood of experiencing crises, and poverty continues to be the greatest threat to child well‐being and the best predictor of abuse and neglect (Martin & Citrin, 2014). Childhood abuse and neglect influence mental health and the association with maltreatment is well established and seen for several disorders across the life course, including childhood behavioral disorders, adult mood and anxiety disorders, and suicidality (Geoffroy et al., 2016). Many of our families live with toxic stress that can cause lasting damage to the developing brain and lead to lifelong problems in learning, behavior, and physical and mental health (Shonkoff & Bales, 2011).

Mental health treatment is a vital intervention designed to provide support, clinical care and healing from adverse circumstances and events. However, both community‐based therapists and caregivers identify barriers to engagement such as caregivers' attitudes and beliefs about treatment, complex needs of parents and children, caregivers' feeling blamed or ignored, and caregiver mental health problems (Haine‐Schlagel et al., 2017). Traditionally research focuses on two areas of client engagement: (a) structural barriers, such as transportation, insurance, and childcare, and (b) attitudes, beliefs, and perceptions about mental health services (Olin et al., 2010). Additionally, using an ecological perspective, family contextual factors, such as parental stress and social support, influence whether families engage in treatment or benefit from treatment over time (Olin et al., 2010).

The influence of our client's environmental context on their mental health and their response to clinical interventions informs our approach to providing mental health treatment. We attempt to improve family engagement by employing a diverse and clinically astute team that practices with cultural humility. We also identify barriers to engagement with the family and work together to alleviate the challenges. This comprehensive approach helped us prepare and respond to the complexities of planning for the local arrival of a global pandemic.

Considerations and planning for COVID‐19 pandemic telehealth transition

In February 2020, as we learned more about the global impact of COVID‐19 pandemic and its impending arrival in the United States, CCS leadership met regularly to strategically plan our response to mitigate risk to our employees and clients. We had existing crisis and business interruption plans, but most of our scenarios dealt with the loss of electricity or Wi‐Fi due to our experiences with Hurricane Sandy in 2012 when we lost power for almost 2 weeks. At the start of the COVID‐19 pandemic, our immediate concern was how to provide needed mental health services while considering the safety of our employees and our clients. We were also concerned about our ability to keep the company in a financially viable position with the continuing threat of reduced revenue and subsequent financial uncertainty. The rates of clients keeping appointments steadily declined throughout February and the beginning of March as people became increasingly fearful to leave their homes due to the then unknown risks associated with COVID‐19 virus.

There were competing concerns about providing essential mental health services to our clients and managing our teams' anxiety regarding their potential exposure to the virus, and tensions were high among our staff. The week before New Jersey's stay‐at‐home order, we began daily conference calls with all employees to discuss their concerns, our plans, and to provide direction regarding next steps. Conversations regarding the meaning of “essential” workers became the norm, and we continued to negotiate and balance the needs of our business, ensuring safe service delivery, and keeping our employees and clients safe. As medical hospitals worked to flatten the curve of anticipated transmission and hospitalizations due to the COVID 19 virus, we recognized that terminating outpatient and IIC services with our vulnerable population would create a strain on acute mental health care services that were already at capacity and would place our clients at greater risk for mental health crises.

As a Medicaid provider, our profit margins are low, and our concerns related to financial well‐being for the company were legitimate. We began projections for how long we could maintain payroll and how long it would take us to recover and pay back any loans, if required. Unemployment rates began to skyrocket, and we desperately wanted to keep our team employed. The situation was dire, so we began to discuss our capability to transition to telehealth. In the past, we had discussed possibly providing telehealth to help improve engagement and access to care. However, due to restrictive state and federal regulations, we tabled the discussion as an area to explore for future expansion. Fortunately, we had worked hard over the years to create a paperless environment, electronic health records, and a robust electronic policy and procedure manual on a shared HIPAA‐compliant Internet network. We met around the clock to determine how we would transition to provide administrative support to our clients and staff while moving to remote mental health services through telehealth platforms.

Telehealth regulations pre– and post–COVID‐19 pandemic response

Before COVID‐19, CCS did not provide telehealth services. Although New Jersey supported telehealth initiatives before the pandemic, the emphasis was on the provision of emergency mental health screening for rural areas in hospital‐based networks (New Jersey Department of Health, 2019). Telehealth was highly regulated, had unique billing codes and reimbursement rates, and was difficult to implement in a community‐based mental health clinic. Four days before Governor Phil Murphy's order approving telehealth, we ceased on‐site mental health services in our outpatient clinics due to mounting concerns from our direct service providers. Our IIC providers reported increased cancellations, but many continued with their scheduled visits because of overriding concerns for their client's mental health. School districts were transitioned to distance learning, and our clients and their families were adapting to new demands for technology, loss of employment, and fear of the unknown. We called families, cancelled sessions, and surveyed technology needs. Our management team was investigating HIPAA‐compliant platforms, developing instruction manuals for our clinicians and our clients, and planning for the transition to a work‐from‐home environment. Our frontline workers were noticeably relieved by this course of action and began rolling up their sleeves to prepare for the transition to telehealth.

We planned for what we assumed would be a coordinated state and federal response to waive telehealth restrictions, but we heard very little from our government leaders during this time. We emailed our state senators, assemblymen and women, and our U.S. representatives imploring them to take action. Our business was at risk of closing, and we did not want to contribute to the unemployment rates or abandon our employees or clientele. We applied for the Payroll Protection Program (PPP) but knew PPP money was running out quickly. The mounting risk to our already‐vulnerable population was weighing heavily on our hearts and minds. We understood that increased stress, isolation, and anxiety are triggers for existing trauma and mental health symptoms and contribute to increases in domestic violence and child maltreatment. Additionally, we were keenly aware that the urban communities were disproportionately represented in rates of contracting the COVID‐19 virus and rates of COVID‐19–related deaths.

As we provided resources, inventoried our clients' technology needs, and developed training and tips for telehealth, our clinicians kept in touch with their clients and their families by phone. On March 18, 2020, all employees were transitioned to their homes with laptops, training, and resources. On March 19, 2020, as anticipated, Governor Murphy signed an executive order to expand telehealth services in response to COVID‐19 pandemic stay‐at‐home orders. This order increased flexibility in technological platforms used to deliver services, waived site of service requirements for telehealth allowing providers to deliver services via telehealth platforms, provided mechanisms for clients to receive services from any location, and provided reimbursement for telehealth services at the same rate as face‐to‐face services. With this executive order, we formally began our telehealth response (New Jersey Department of Human Services, 2020).

TRANSITION TO TELEHEALTH: PRACTICAL AND CLINICAL OBSERVATIONS

Procedures

As a practice, the executive leadership at CCS routinely generates and evaluates data regarding our service delivery. We compile and examine scheduled and attendance rates weekly; we collect customer satisfaction surveys and report on the results quarterly, and we communicate through various channels with our service providers weekly and monthly. In response to COVID‐19 and our expedited transition to telehealth we continued our usual collection and assessment of data and solicited additional information as well. We dedicated more time to hearing from our clinicians and their managers through conference calls and virtual team meetings. Initially we met daily, then weekly as we addressed staff and client challenges and adjusted to the new telehealth format. After a couple of months, we resumed our typical business communications structure of weekly manager–employee meetings and quarterly meetings with executive leadership. The solicitation and compilation of data before and throughout our transition to telehealth informed our decision‐making and these lessons from the field.

Observations

After months of providing telehealth, we have worked through many of the initial challenges; and, overall, our clients, their families, and our staff are highly satisfied with the transition. Through company‐wide conference calls, team meetings, clinical supervision, individual and group discussions, and a response to an invitation for employees and clients to provide feedback, we have learned a great deal about our expedited transition to telehealth. Within the first 2 weeks of providing telehealth services, our clinicians, administrative staff, and management personnel engaged families on the phone to troubleshoot, provide resources and walk‐through downloading applications or software to engage in telehealth services. Most families expressed gratitude and were eager to begin services, very few declined services altogether. Many of the families overcame technology issues, yet for some, concerns remained in relation to spotty‐coverage, last‐minute cancelations, lack of privacy, limited cameras, and general confusion regarding technology.

Client observations

Graduate school interns reached out to clients 6 months after the initiation of telehealth to ask about their satisfaction with telehealth services. This was a practice‐based, quality assurance initiative; it was not conducted as a research study. Fifty calls were completed, and of those, all 50 indicated that they were satisfied with the telehealth transition. Eight caregivers (16%) of the 50 commented that they look forward to returning to the office setting when it was safe but were grateful for telehealth at this time. Twenty‐one caregivers (42%) specifically commented that they preferred telehealth and hoped that it would continue after the pandemic ends. Reasons for their preference included underlying health concerns, not wasting time in traffic, and increased time at home for doing homework, caring for siblings, and cooking dinner.

Psychiatric team's observations

Our advanced practice nurse (APN) psychiatric team is responsible for conducting psychiatric evaluations, prescribing medication when indicated, and providing routine medication management appointments when medication is prescribed. Members of this team have expressed gratitude for the move to telehealth; however, they reported several ways telehealth was lacking functionality compared with in‐person visits. For example, APNs missed the observations of nonverbal cues, eye contact, body language, and facial expressions. They suggested the sessions lacked intimacy, and they were concerned about clients who presented at appointments with higher acuity because it was difficult to triage and determine the need for psychiatric screening or higher level of care through telehealth, especially for new clients where rapport had not been established. The APNs identified observing clients in their own environment as a strength; it also was a limitation if, for example, adolescents were in bed and not fully dressed for their session. Additionally, the APNs worried if their psychiatric evaluations and medication management appointments would run longer because the next patient was waiting virtually and not in a waiting room.

The APNs and clinicians unanimously reported that clients who struggled with school phobia, anxiety, and/or refusal before the pandemic were doing much better because they were no longer under pressure to attend school in person. However, there was a realistic concern about acclimating these children back to school when it was deemed appropriate. Attempts were made to engage the youth and the parents in proactive dialogue regarding the school‐based issues, but many families had minimized the issues now that their children were not in school. Additionally, clinicians identified concerns regarding the educational impact for those students who were now engaging in distance‐learning because some of the youth had impaired cognition or a history of difficulty keeping up academically for various contextual reasons.

Clinical team's observations

The clinical team was responsible for conducting biopsychosocial intake evaluations, developing treatment plans with the client and family, and implementing those plans by providing weekly individual and family therapy sessions. The clinical team reported that telehealth with adolescents had proven more effective and they felt that the adolescents were “in their element” and more engaged in sessions. Some clinicians claimed that although some youth were shy on camera, many participated more actively, and some youth had opened up more through messaging features in the telehealth sessions. Many clinicians provided examples of adolescents disclosing or more actively discussing traumatic histories through telehealth, and there were examples of youth exploring sexual identity issues more freely than in person. The clinicians attributed this newfound candor with the adolescents' feeling of safety behind the virtual setting and becoming less guarded and self‐conscious as they might in‐person sessions.

Unfortunately, the team expressed difficulty engaging with children under age 10 years through telehealth, especially those with attention or hyperactivity symptoms. Yet some outpatient clinicians highlighted the fact that they were able to see behaviors at home through telehealth that they were unable to see in the office. Many of these younger children were referred to CCS due to their inability to control their anger, an increase in frequency and duration of temper tantrums, lack of frustration tolerance, and oppositional defiance. However, in the office setting, most children behaved well, enjoyed the one‐on‐one attention and therapeutic games, and often did not display these behaviors.

There was consensus among the clinical team regarding the increased presentation of symptoms of anxiety and depression. Additionally, there was a surge of grief work due to loss of extended family members and loved ones. Some clinicians identified a unique, troubling aspect of working within this context because it was not common for them to simultaneously experience the same stressors or stress response as their clients, yet many of them endured similar anxiety, loss, and fear. The clinical team was encouraged to discuss this parallel process in clinical supervision and during their multidisciplinary team meetings.

Various perspectives were shared by the clinical team regarding the content of sessions and the general perception of whether children and families were making progress in treatment throughout this time period—or were they maintaining the status quo, which, during the pandemic, we perceived as an accomplishment. Some clinicians reported that the clients and families had an increase in “crisis‐of‐the‐week” sessions and the clinicians struggled to address treatment goals in lieu of COVID‐19 pandemic‐related issues. Others reported that because families were home, fewer crises were reported, which allowed for greater concentration on treatment goals. Finally, some clients and families expressed frustration during sessions as they reported nothing new to discuss due to being in the same uneventful routine.

Regarding the frequency, duration, and content of sessions, most clinicians indicated that they “checked in” more frequently and provided shorter sessions, multiple times a week, in contrast to weekly 1‐h sessions. Most clinicians reported a successful learning curve for embracing technology within their sessions, which included sharing screens and online activities, which replaced in‐office therapeutic games, handouts, and activities. Additionally, the clinicians suggested that they were more responsive to their clients' scheduling needs because they had greater flexibility in their schedule as both they and their clients were home. However, this led to discussions regarding boundaries and our concern about the difficulties of turning off their workday and structuring their time. Most staff reported adjusting well after a few weeks and learned how to balance their work and home life while working from home.

The physical space and number of people living in the client's home presented challenges to some clinicians. Although most clinicians generally reported greater privacy, some worried that there was no quiet place to conduct a session, as siblings wandered in and out of the room and there were generally more distractions. Family involvement in sessions increased for the most part because most parents were home due to pandemic restrictions and were eager to engage in sessions. On the other hand, some caregivers were working (in or out of the home), cooking, or caring for siblings and struggled to participate in sessions. The IIC clinicians who typically work in the homes expressed greater difficulty engaging the entire family unit as they were used to interacting with all family members while they were visiting in‐person in the home environment.

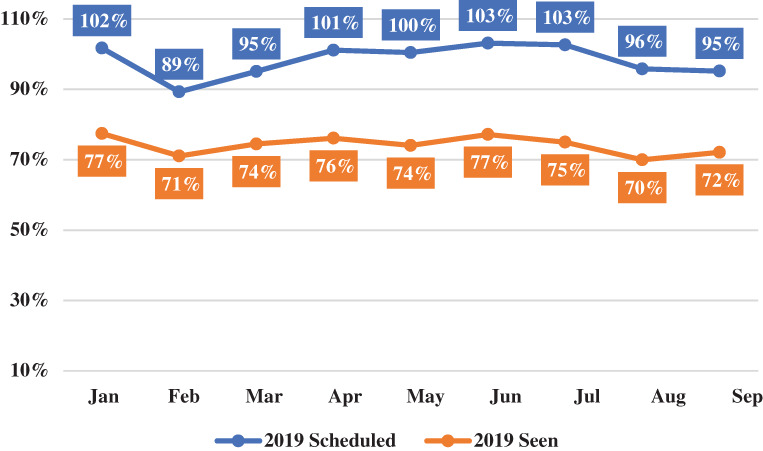

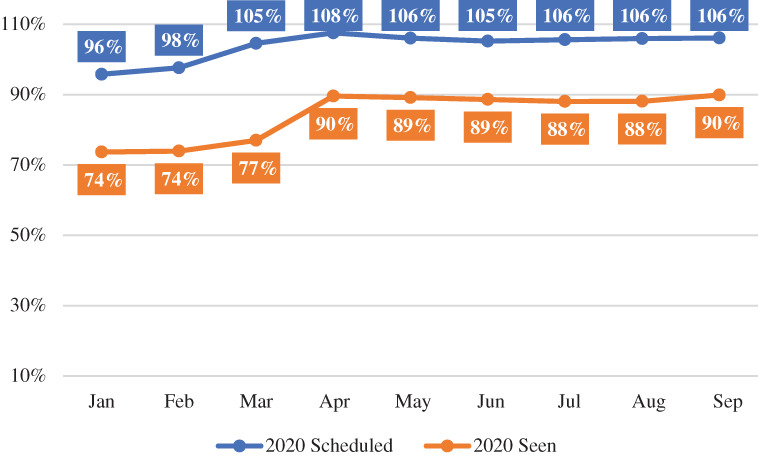

Business operations observations

CCS's leadership team measures and manages our scheduled and rates of attendance for scheduled appointments for our outpatient clinics through both a clinical and business operations lens. Examining engagement numbers allows us to respond to barriers to treatment to ensure our clients receive and benefit from mutually agreed‐on clinical services. Analyzing scheduled and attendance rates from a business perspective allows us to better manage financial projections. Our attendance rates for our outpatient programs have increased through the pandemic and the implementation of telehealth services. Our average attendance rate for January 2019 through September 2019 was 74%. The average attendance rates in months with only telehealth services, attendance rates increased to 89% (see Figures 1 and 2). There were fewer cancellations because there were fewer scheduling conflicts (e.g., school or sports conflicts), and rescheduling cancelled appointments within the same week was easier because the clinician and family had more flexibility using telehealth.

FIGURE 1.

Scheduled versus show rate: 2019

FIGURE 2.

Scheduled versus show rate: 2020

Our IIC clinicians reported more availability to add clients to their caseload because they did not have to account for travel time to and from the client's homes. Additionally, the IIC clinicians were experiencing fewer families not attending scheduled appointments at their own homes because they had to remain home due to the pandemic and stay‐at‐home‐orders. Our clinical and management teams remained available for our clientele because we are keenly aware of the detrimental impact of stress on our population.

TRANSITION TO TELEHEALTH: LESSONS LEARNED

There are lessons learned from the initiation of telehealth that may be useful for the provision of community‐based mental health services moving forward during and after the pandemic. Community‐based needs assessments historically highlight transportation as a primary barrier to mental health treatment for families (Syed et al., 2013) in New Jersey. Whether in an urban or rural area, the ability to easily access mental health services remains a challenge. Many of our outpatient clients' families have expressed relief over no longer needing to use public transportation, unreliable medical transport, or drive‐share services. The families report saving time and money and no longer worrying about childcare for their other children during sessions. Additionally, many families claim they are saving money because they do not need to eat out on the nights they have therapy.

Regarding IIC services, before the COVID‐19 pandemic, there were difficulties securing clinicians to deliver in‐home services in many of the urban and rural communities. Locating a bilingual clinician or a clinician with a specific specialty for a challenging geographic location was problematic. Telehealth offers a larger network of clinicians to clients and families whose mental health may be decompensating while they wait for a clinician to be located who can provide the needed service in their location. We recognize the potential dangers of convenience outweighing the therapeutic indications; however, if we do not consider these realistic barriers to treatment, children and adolescents may not receive services at all. As with telemedicine, it seems that despite opportunities for improved access to care, telehealth has not been widely explored or implemented (Barney et al., 2020).

Cautions of telemedicine include challenges in reading nonverbal cues through telemedicine platforms. The inability to read these cues may lead to serious implications that may influence proper diagnosing; decrease our ability to recognize important signs and symptoms of abuse, neglect, and domestic violence; and depersonalize a field in which engagement and therapeutic rapport is vital to the process of healing. However, the increased openness, candor, and disclosures by our adolescent clients suggests that there may be more ways to connect with a human being than face‐to‐face in an office setting. Perhaps a hybrid telehealth option will become the preferred therapeutic modality for clients. The provision of mental health services must be considered when the medical field inevitably evaluates the potential risks and benefits to continuing to provide telehealth and its impact on the quality of patient care (Wood et al., 2020).

Our clinical team's prior discomfort and mistrust of technology may have thwarted our exploration of this platform. Before the COVID‐19 pandemic response, most of our team expressed reservations about telehealth and were uncomfortable with the idea of providing services electronically. Since providing telehealth over an extended period of time, the entire team has gained an appreciation for the benefits of telehealth for certain populations and recognize the hidden value in this electronic intervention. Examining CCS's experiences implementing telehealth during a global pandemic aligns with RDS's recognition that the goal of developmental theories should be to reduce or eliminate the challenges to healthy, positive development facing diverse children, families, and communities in the 21st century (Lerner et al., 2015).

Our team supports advocacy for incorporating telehealth into our future practice. We have provided many examples that support using telehealth in the future, including a family waiting at home for a medical transport that does not show; the family could go back inside and conduct a session through telehealth instead of missing a week of care. Or telehealth may benefit a family who cannot obtain childcare for siblings or a bilingual family that needs to travel over an hour each way to find a clinician who speaks their native language. Telehealth may also help clinicians with different abilities or chronic illnesses. Through the use of telehealth, clinicians with physical challenges may see clients from the convenience of their own home. Telehealth will help make us more responsive, inclusive service providers.

However, there is also a need for caution and ensuring the responsible use of telehealth. Unfortunately, the lack of on‐site oversight and the loosening of requirements for signatures regarding service delivery and consent may lead to increased fraud and misuse. At CCS, we have amplified our quality assurance measures and are increasing our outreach to families to verify satisfaction with services. The medical and mental health field has experienced the benefits and limitations of telehealth, and there is no denying it is here to stay. Further research and attention should be given to its ability to address health inequities, and guidelines must be developed for proper decision‐making and use of this technology (Evans et al., 2020). Perhaps now telehealth will become an accepted modality for clients who have stabilized or experience barriers to traditional on‐site, in‐person service delivery.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The author confirmed with the University IRB that the information gathered during our normal course of business and presented for the purposes of this article did not require IRB submission or approval as identifying data was not used and the article is relaying lessons from the field as a subjective experience to reflect and inform practice.

Moorman, L. K. (2022). COVID‐19 pandemic‐related transition to telehealth in child and adolescent mental health. Family Relations, 71(1), 7–17. 10.1111/fare.12588

references

- Barney, A. , Buckelew, S. , Mesheriakova, V. , & Raymond‐Flesch, M. (2020). The COVID‐19 pandemic and rapid implementation of adolescent and young adult telemedicine: Challenges and opportunities for innovation. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(2), 164–171. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. , & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In Lerner R. M. & Damon W. (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (pp. 793–828). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Y. N. , Golub, S. , Sequeira, G. M. , Eisenstein, E. , & North, S. (2020). Using telemedicine to reach adolescents during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(4), 469–471. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geoffroy, M. , Pereira, S. , Li, L. , & Power, C. (2016). Child neglect and maltreatment and childhood‐to‐adulthood cognition and mental health in a prospective birth cohort. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(1), 33–40e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haine‐Schlagel, R. , Mechammil, M. , & Brookman‐Frazee, L. (2017). Stakeholder perspectives on a toolkit to enhance caregiver participation in community‐based child mental health services. Psychological Services, 14(3), 373–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kids Count Data Center . (2020a). Children in poverty by age group. The Annie E. Casey Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Kids Count Data Center . (2020b). Children who have one or more emotional, behavioral, or developmental conditions. The Annie E. Casey Foundation. https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data#NewJersey/2/27/28,29,30,31,32,34,33/char/0

- Kids Count Data Center . (2020c). Children who have experienced adverse experiences in New Jersey. The Annie E. Casey Foundation. https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/9709-children-who-have-experienced-two-or-more-adverse-experiences?loc=32&loct=2#detailed/2/32/false/1603/any/18961,18962

- Kids Count Data Center . (2020d). Children who are subjected to an investigated report in New Jersey. The Annie E. Casey Foundation. https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/6220-children-who-are-subject-to-an-investigated-report?loc=32&loct=2#detailed/2/32/false/37,871,870,573,869,36,868,867,133,38/any/12940,12955

- Lerner, R. M. (2006). Developmental science, developmental systems, and contemporary theories of human development. In Lerner R. M. & Damon W. (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (pp. 1–17). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, R. M. , Johnson, S. K. , & Buckingham, M. H. (2015). Relational developmental systems‐based theories and the study of children and families: Lerner and Spanier (1978) revisited. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 7(2), 83–104. 10.1111/jftr.12067 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, M. & Citrin, A. (2014). Prevent, protect & provide: How child welfare can better support low‐income families. Center for the Study of Social Policy. https://cssp.org/resource/prevent-protect-and-provide-how-child-welfare-can-better-support-low-income-families/

- New Jersey Department of Health . (2019). New Jersey Department of Health awarded $2.3 million to enhance pediatric mental health care through telehealth [Press release]. https://www.NewJersey.gov/health/news/2019/approved/20190110a.shtml

- New Jersey Department of Human Services . (2020). Governor Murphy announces departmental actions to expand access to telehealth and tele‐mental health services in response to COVID‐19 [Press release]. https://www.NewJersey.gov/humanservices/news/pressreleases/2020/approved/20200323.html

- Olin, S. , Hoagwood, K. , Rodriguez, J. , Ramos, B. , Burton, G. , Penn, M. , Crowe, M. , Radigan, M. , & Jensen, P. (2010). The application of behavior change theory to family‐based services: Improving parent empowerment in children's mental health. Journal of Child Family Studies, 19(4), 462–470. 10.1007/s10826-009-931-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overton, W. (2013). Relationism and relational developmental systems: A paradigm for developmental science in the post‐Cartesian era. Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 44, 21–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff, J. , & Bales, S. N. (2011). Science does not speak for itself: Translating child development research for the public and its policymakers. Child Development, 82(1), 17–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed, S. T. , Gerber, B. S. , & Sharp, L. K. (2013). Traveling towards disease: Transportation barriers to health care access. Journal of Community Health, 38(5), 976–993. 10.1007/s10900-013-9681-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood, S. M. , White, K. , Peebles, R. , Pickel, J. , Alausa, M. , Mehringer, J. , & Dowshen, N. (2020). Outcomes of a rapid adolescent telehealth scale‐up during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(2), 172–178. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]