Abstract

The COVID‐19 pandemic had a severe impact on medical care. Our study aims to investigate the impact of COVID‐19 on advanced melanoma care in the Netherlands. We selected patients diagnosed with irresectable stage IIIc and IV melanoma during the first and second COVID‐19 wave and compared them with patients diagnosed within the same time frame in 2018 and 2019. Patients were divided into three geographical regions. We investigated baseline characteristics, time from diagnosis until start of systemic therapy and postponement of anti‐PD‐1 courses. During both waves, fewer patients were diagnosed compared to the control groups. During the first wave, time between diagnosis and start of treatment was significantly longer in the southern region compared to other regions (33 vs 9 and 15 days, P‐value <.05). Anti‐PD‐1 courses were postponed in 20.0% vs 3.0% of patients in the first wave compared to the control period. Significantly more patients had courses postponed in the south during the first wave compared to other regions (34.8% vs 11.5% vs 22.3%, P‐value <.001). Significantly more patients diagnosed during the second wave had brain metastases and worse performance status compared to the control period. In conclusion, advanced melanoma care in the Netherlands was severely affected by the COVID‐19 pandemic. In the south, the start of systemic treatment for advanced melanoma was more often delayed, and treatment courses were more frequently postponed. During the second wave, patients were diagnosed with poorer patient and tumor characteristics. Longer follow‐up is needed to establish the impact on patient outcomes.

Keywords: advanced melanoma, clinical outcomes, COVID‐19, nationwide registry, systemic therapy

Short abstract

What's new?

Little is known about the effects of COVID‐19 on advanced melanoma care. In this study, the authors examined several quality indicators of care. They observed a worsening in baseline characteristics, longer time between diagnosis and start of treatment and more postponed anti‐PD‐1 antibody courses with differences between the northern, middle and southern regions. Future studies are necessary to assess the long‐term consequences of our observed changes in advanced melanoma care.

Abbreviations

- AJCC

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- DMTR

Dutch Melanoma Treatment Registry

- ECOG PS

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status

- ICI

immune checkpoint inhibitor

- ICU

intensive care unit

- IQR

interquartile range

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- NICE

National Intensive Care Evaluation

- NVMO

Nederlandse Vereniging voor Medische Oncologie (Dutch Association for Medical Oncology)

- PALGA

Pathologisch‐Anatomisch Landelijk Geautomatiseerd Archief (Dutch Registry of Histopathology and Cytopathology)

1. INTRODUCTION

The SARS‐CoV‐2 virus has been unprecedentedly disruptive to societies worldwide, infecting over 200 million people, with over 4 million people having died from the virus at the time of writing. 1

Like health care systems in other parts of the world, Dutch healthcare was flooded by the care for COVID‐19 patients. Due to the possible exhaustion of the Dutch healthcare system, diagnostics and care for other diagnoses were in some cases postponed or canceled. In addition, oncological care including advanced melanoma care was affected by fear of potential adverse effects of immunosuppressive oncological treatment and checkpoint inhibition on the course of a COVID‐19 infection. 2 Research indeed showed cancer patients to be at increased risk from COVID‐19 related fatality, 3 although the use of checkpoint inhibitors did not seem to affect this risk as much as initially anticipated. 4

Early studies reported a decrease in melanoma diagnoses during the lockdown and an increase in Breslow thickness in patients diagnosed postlockdown as a result of delaying melanoma care. 5 , 6 Yet, effects on systemic melanoma treatment such as treatment delays, discontinuations, or switches during lockdowns are largely unknown.

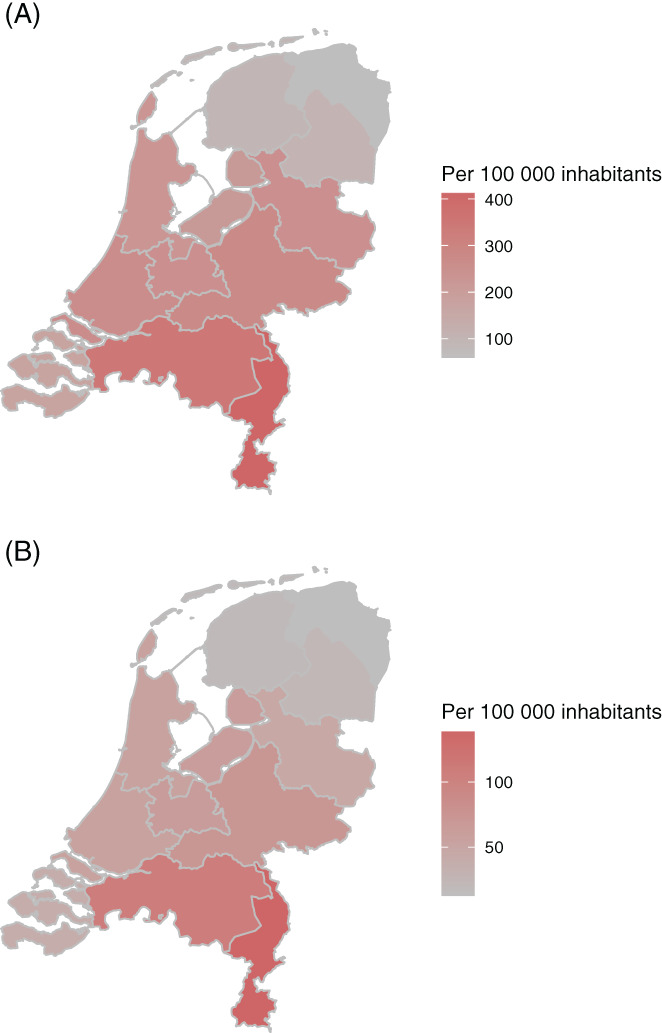

The first case of COVID‐19 in the Netherlands was diagnosed on 27 February 2020, in the southern part of the Netherlands. 7 The first COVID‐19 wave lasted from March until May 2020 and affected the midsouthern region the heaviest (Figure 1A,B). The number of new COVID‐19 cases declined during the summer but showed a substantial increase from October till December 2020. This increase resulted in the second COVID‐19 wave. 8

FIGURE 1.

(A) Cumulative number of patients with a positive test for SARS‐CoV‐2 in the Netherlands per 100 000 inhabitants at the end of the first wave (24 May 2020). (B) Cumulative number of COVID‐19 patients admitted in the hospital in the Netherlands per 100 000 inhabitants at the end of the first wave (24 May 2020). Data used for this figure are publicly available from the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

So far, no reports have investigated the influence of COVID‐19 on advanced melanoma care nationwide. Our study aims to investigate the impact of the first year of COVID‐19 on the care for stage IIIc and IV advanced melanoma patients in the Netherlands.

2. METHODS

2.1. Patients

For our study, we used data from the Dutch Melanoma Treatment Registry (DMTR) and the Dutch National Intensive Care Evaluation (NICE). The DMTR prospectively registers data of all unresectable stage III and IV melanoma patients in the Netherlands since 2012. A detailed description of the DMTR setup has been published by Jochems et al. 9 For our study, we divided patients in the Netherlands into four groups over time based on the COVID‐related pressure on the healthcare system. To determine the healthcare system's burden throughout the country, we used data from the Dutch NICE on the number of hospital beds occupied by COVID‐19 patients. 10 , 11 The starting point of the first COVID‐19 wave, 16 March, was determined based on the moment in time when COVID‐19 patients occupied more than 500 hospital beds or more than 200 beds on the intensive care unit (ICU) in the Netherlands. On 24 May 2020, fewer than 200 ICU beds were occupied, marking the endpoint of the first COVID‐19 wave. The second COVID‐19 wave started on 21 September 2020. December 27 was marked as the endpoint of the second wave in this article, since baseline data registration was complete until this date.

Based on these numbers, we divided patients 18 years and older diagnosed with irresectable stage IIIc and IV advanced melanoma into four groups: (a) patients who had their first visit to a melanoma center during the first wave, (b) patients who had their first visit in the period between the first and the second wave between 25 May and 20 September (between‐wave period), (c) patients who had their first visit during the second wave between 21 September and 27 December 2020 and (d) for these groups, controls in the same periods in 2018 and 2019 were selected. For the second wave, most patients' outcomes are not yet available due to limited follow‐up. We, therefore, only report on the baseline characteristics of these patients.

We further divided patients into three geographic regions based on the maximum number of hospital admissions for COVID‐19 patients during the first wave. In the Netherlands, the southern region was the first region to be affected by a large number of COVID‐19 patients. The middle region of the Netherlands has the highest population density and was moderately affected by COVID‐19 due to the spread from the south. During the first wave, the northern region was the least affected, assisting in care for COVID‐19 patients from the south but without many inhabitants from their own region being affected. 12 Patients were assigned to the melanoma center where they were first seen by a medical oncologist.

For our study, the dataset cut‐off date was 7 April 2021.

2.2. Patient characteristics

For the time periods and regions, the following patient and tumor characteristics were described at diagnosis: age, gender (male, female), baseline Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) (0‐1, ≥2), baseline lactate dehydrogenase levels (LDH; normal, 250‐500 U/L, >500 U/L), organs with distant metastases (<3 organ sites, ≥3 organ sites involved), brain metastases (none, asymptomatic and symptomatic), liver metastases (yes, no), stage according to American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 8th edition and BRAFV600 mutational status (wild‐type, mutant).

2.3. Outcomes

We defined several outcome measures to assess the influence of COVID‐19 on the diagnosis and treatment of advanced melanoma patients during the first wave. First, we calculated the time between the diagnosis of advanced melanoma and the start of systemic therapy. Second, we analyzed the number and percentage of patients who received local and/or systemic treatment, the ratio of local and systemic treatment and the type of systemic therapies (anti‐PD‐1 antibodies, ipilimumab‐nivolumab, BRAF/MEK inhibitors and ipilimumab monotherapy). Local therapy consisted of radiotherapy, radio frequency ablation, hyperthermia or surgery. Third, we investigated the number and percentage of patients switching therapeutic agents and the number of patients with postponed treatment courses. The numbers and percentage of patients are based on patients actively being treated during the predefined time periods. Last, we evaluated the number of radiologic examinations performed for diagnosing and staging of the melanoma (CT scans, PET‐CT scans and MRI scans).

2.4. Statistical analysis

Baseline patient characteristics were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Pearson's chi‐squared test was used to compare categorical variables. The t‐test was used to compare numeric data. Comparisons were considered statistically significant for two‐sided P‐values <.05. Data handling and statistical analyses were performed using R studio (version 4.0.2), 13 packages tidyverse, 14 tableone, 15 survival 16 and survminer. 17

3. RESULTS

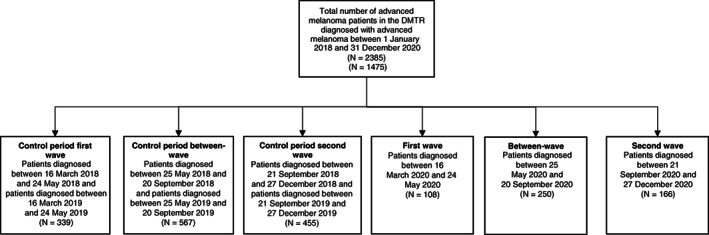

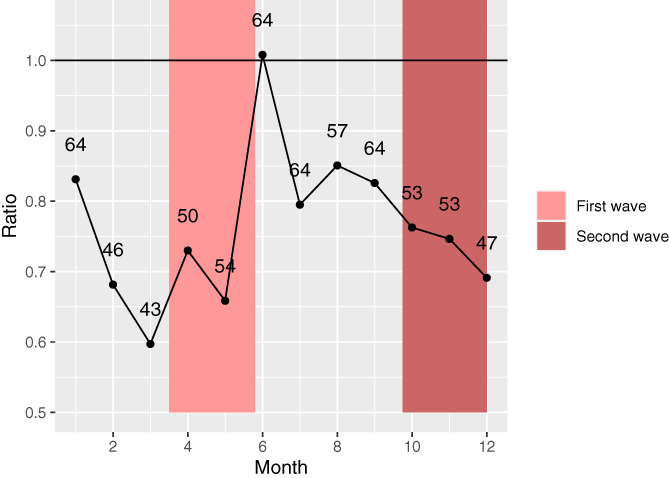

During the first wave, a total of 108 patients (47 per month) with unresectable stage IIIc or stage IV melanoma were registered in the DMTR (Figures 2 and 3). In the control period of the first wave, a combined number of 339 patients were diagnosed (74 per month). In the between‐wave period (May‐September), 250 patients were diagnosed (63 per month). During the second wave, 166 patients were diagnosed (52 per month) compared to 455 patients in the control period (71 per month). An observed/expected ratio of the number of newly diagnosed patients is shown in Figure 3. Based on 2018 and 2019, we would have expected 205 more patients to be diagnosed with advanced melanoma in 2020.

FIGURE 2.

Flow chart of patients included in our study

FIGURE 3.

Observed/expected ratio of registered advanced melanoma patients per month. The ratio was calculated as: (number of patients 2020)/(number of patients ([2018 + 2019])/2) per month. The number of observed newly diagnosed patients are presented in the graph as numbers [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Patient characteristics at baseline are shown in Table 1. Comparison of baseline patient and tumor characteristics in the first and second wave vs control periods are shown in Appendix S1. Baseline patient and tumor characteristics of the three regions are shown in Appendix S1. During the second wave, a worsening of baseline characteristics of advanced melanoma patients in the Netherlands was observed. Forty‐one percent of patients who had their first visit after the start of the second wave presented with brain metastases, compared to 29% in the control group (P = .016). Patients also had a worse ECOG PS (≥2) in 28% vs 16% of patients (P = .002). The percentage of patients who received systemic therapy as a first‐line therapy did not vary between the first wave and the control period; 72% (N = 78) vs 76% (N = 256), respectively.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics (periods)

| Baseline variable | First wave | Between‐wave | Second wave | Control period first wave | Control period second wave |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 108) | (N = 250) | (N = 166) | (N = 339) | (N = 455) | |

| Age, median (range) | 69 (36‐94) | 68 (22‐91) | 68 (27‐91) | 68 (21‐92) | 66 (24‐92) |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 60 (55.6) | 148 (59.2) | 97 (58.4) | 199 (58.7) | 269 (59.1) |

| Female | 48 (44.4) | 102 (40.8) | 69 (41.6) | 140 (41.3) | 186 (40.9) |

| ECOG PS | |||||

| 0–1 | 79 (82.3) | 181 (77.7) | 109 (72.2) | 259 (85.5) | 351 (84.4) |

| ≥2 | 17 (17.7) | 52 (22.3) | 42 (27.8) | 44 (14.5) | 65 (15.6) |

| LDH | |||||

| Not determined/normal | 54 (54.0) | 133 (58.6) | 77 (50.0) | 195 (60.9) | 255 (59.7) |

| 250‐500 U/L | 29 (29.0) | 59 (26.0) | 48 (31.2) | 83 (25.9) | 100 (23.4) |

| >500 U/L | 17 (17.0) | 35 (15.4) | 29 (18.8) | 42 (13.1) | 72 (16.9) |

| Stage (8th edition AJCC) | |||||

| Unresectable IIIc | 13 (12.3) | 29 (11.9) | 9 (5.5) | 34 (10.1) | 49 (10.8) |

| IV‐M1a | 8 (7.5) | 10 (4.1) | 5 (3.1) | 31 (9.2) | 36 (8.0) |

| IV‐M1b | 11 (10.4) | 33 (13.6) | 24 (14.7) | 38 (11.3) | 44 (9.7) |

| IV‐M1c | 39 (36.8) | 96 (39.5) | 59 (36.2) | 133 (39.5) | 196 (43.4) |

| IV‐M1d | 35 (33.0) | 75 (30.9) | 66 (40.5) | 101 (30.0) | 127 (28.1) |

| Brain metastases | |||||

| No | 68 (66.0) | 163 (68.5) | 94 (58.8) | 225 (69.0) | 309 (70.9) |

| Yes, asymptomatic | 13 (12.6) | 34 (14.3) | 29 (18.1) | 36 (11.0) | 62 (14.2) |

| Yes, symptomatic | 22 (21.4) | 41 (17.2) | 37 (23.1) | 65 (19.9) | 65 (14.9) |

| Liver metastases | |||||

| No | 74 (70.5) | 180 (74.1) | 103 (64.0) | 244 (73.5) | 313 (69.7) |

| Yes | 31 (29.5) | 63 (25.9) | 58 (36.0) | 88 (26.5) | 136 (30.3) |

| Organ sites | |||||

| 0‐2 | 64 (59.3) | 140 (56.0) | 94 (56.6) | 200 (59.0) | 258 (56.7) |

| ≥3 | 44 (40.7) | 110 (44.0) | 72 (43.4) | 139 (41.0) | 197 (43.3) |

| BRAFV600‐mutation | |||||

| Wild‐type | 66 (61.1) | 130 (52.0) | 87 (52.4) | 179 (52.8) | 221 (48.6) |

| Mutant | 42 (38.9) | 120 (48.0) | 79 (47.6) | 160 (47.2) | 234 (51.4) |

| Region | |||||

| North | 15 (13.9) | 51 (20.4) | 33 (19.9) | 74 (21.8) | 90 (19.8) |

| Middle | 65 (60.2) | 139 (55.6) | 102 (61.4) | 178 (52.5) | 266 (58.5) |

| South | 28 (25.9) | 60 (24.0) | 31 (18.7) | 87 (25.7) | 98 (21.5) |

Note: Comparison of baseline characteristics of patients diagnosed in the three different period defined in our study. First wave (16 March 2020 until 24 May 2020), between‐wave (25 May 2020 until 20 September 2020), second wave (21 September 2020 until 27 December 2020) and control periods (16 March 2018 until 24 May 2018 and 16 March 2019 until 24 May 2019) for the first wave and (21 September 2018 until 27 December 2018 and 21 September 2019 until 27 December 2019) for the second wave.

3.1. Time from diagnosis until start systemic therapy

The median number of days between diagnosis with unresectable stage IIIc and IV melanoma and the start of a systemic therapy were similar, varying from 14 (IQR 7‐24) days in the control period to 14.5 (IQR 7‐24.5) days during the first wave (P‐value = .745). The median number of days between diagnosis and start of systemic therapy with unresectable stage IIIc and IV melanoma during the first wave varied between 9.5 (IQR 6‐17.5) days in the northern region, 12 (IQR 5.5‐21) days in the middle region and 21 (IQR 16‐39) days in the southern region (P = .010). No significant differences between the time from diagnosis until the start of systemic therapy were seen between the different regions in the control period (P = .316). The types of systemic therapies that were initiated did not vary significantly over the different time periods. The majority of patients received anti‐PD‐1 antibodies and ipilimumab‐nivolumab as first‐line systemic therapy. However, we did see a shift from anti‐PD‐1 treatment towards ipilimumab‐nivolumab in the second wave. Anti‐PD‐1 was given to 45% of patients in the first wave. During the second wave, only 25% of patients received anti‐PD‐1. Forty percent of patients received ipilimumab‐nivolumab during the second wave vs 31% and 32% during the first wave and between‐wave period, respectively. In addition, a larger number of patients received BRAF/MEK inhibition during the second wave (33%) compared to the first wave (23%) and the between‐wave period (28%). All first‐line systemic treatments can be seen in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

First‐line systemic treatment (periods)

| First wave | Between‐wave | Second wave | Control period first wave | Control period second wave | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 78 | N = 204 | N = 114 | N = 256 | N = 377 | |

| Anti‐PD‐1 | 35 (44.9) | 66 (32.4) | 28 (24.6) | 101 (39.5) | 157 (41.6) |

| BRAF/MEK inhibitors | 18 (23.1) | 58 (28.4) | 37 (32.5) | 79 (30.9) | 95 (25.2) |

| BRAF‐inhibitors | 1 (1.3) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.1) |

| Ipilimumab | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Ipilimumab‐nivolumab | 24 (30.8) | 65 (31.9) | 45 (39.5) | 60 (23.4) | 97 (25.7) |

| Chemotherapy | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Other treatment | 0 (0.0) | 7 (3.4) | 4 (3.5) | 9 (3.5) | 14 (3.7) |

| T‐VEC | 0 (0.0) | 5 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (2.7) | 9 (2.4) |

Note: Type of first‐line systemic therapy between the three different periods.

3.2. Postponement of checkpoint inhibitor courses

Compared to the control period, significantly more courses of anti‐PD‐1 were postponed in patients on treatment during the first wave (N = 30 [3.0%] vs N = 173 [20.0%], P‐value <.001). This percentage of postponed courses varied between the three regions. Significantly more patients diagnosed in one of the southern centers (34.8%, N = 89) had their anti‐PD‐1 antibodies treatment postponed during the first wave compared to patients diagnosed in the middle (11.5%, N = 55) and northern centers (22.3%, N = 29, P‐value <.001). Of the 173 postponed courses, 26.0% (N = 45) was postponed within 3 months of starting anti‐PD‐1 therapy, 23.7% (N = 41) was postponed within 3 to 6 months of starting anti‐PD‐1 therapy and 53.0% (N = 87) was postponed >6 months after starting anti‐PD‐1 therapy. Only nine courses of either ipilimumab or nivolumab in the induction phase were postponed during the first wave.

3.3. Other outcomes

The number of patients that discontinued a systemic therapy during the first wave did not differ significantly from the control period (N = 285 vs N = 565). Imaging of the brain at baseline was performed in a slightly higher percentage of patients during the first wave compared to the control period (84.8% vs 76.7%, P‐value = .108). A PET/CT‐scan or CT‐scan at baseline for diagnosis and staging was performed in 96.3% of patients diagnosed during the first wave and 97.6% of the patients diagnosed during the control period (P‐value = .586). The number of patients treated with local therapy (radiotherapy, radio frequent ablation, hypothermia or surgery) as first treatment was significantly lower for patients diagnosed during the first wave compared to the control period (18.5% vs 30.3%, P‐value <.001).

4. DISCUSSION

Our study, based on a nationwide prospective registry of advanced melanoma patients, describes the effects of the COVID‐19 outbreak on advanced melanoma care in the Netherlands. We observed a significantly longer time from diagnosis of advanced melanoma to start of systemic therapy in the most severely affected southern regions compared to the middle and northern regions (median of 21 days vs 12 days vs 9.5 days). This delay between diagnosis and start of systemic therapy is probably caused by the downscale of oncological care during the COVID‐19 pandemic as southern regions had the highest COVID‐19 rates. Downscaling of outpatient clinical care and patients' fear for hospital visits resulted in less patients visiting their oncologist. Additionally, the fear for a COVID‐19 induced cytokine storm resulted in significantly more postponed anti‐PD‐1 courses in the more heavily affected southern regions compared to the northern and middle regions (35% vs 12% vs 23%). During the second wave, patients presented with more brain metastases and a worse ECOG PS, compared to the control period.

The findings of our study remain relevant since new upcoming COVID‐19 mutations could cause a third COVID‐19 wave in 2021, with these mutations being deemed more contagious than the original SARS‐CoV‐2 virus. 18 At the time of writing, the third wave is declining. It is too early to report on the consequences of the second and third wave. Based on studies reporting a decrease in cancer diagnoses and the reduction in patient referrals 19 and our findings of a decrease in new advanced melanoma diagnoses during the first COVID‐19 wave, which has not been caught up during the between‐wave period, one can understand the worsening of baseline characteristics our study observed. These poorer baseline characteristics can also explain the shift in the type of systemic treatments used. During the first wave, first‐line anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy was the most frequently administered drug. During the second wave, ipilimumab‐nivolumab was most often administered, followed by BRAF/MEK‐inhibitors. This increase in patients receiving ipilimumab‐nivolumab could be the result of the increase in the number of patients with brain metastases at baseline. Ipilimumab‐nivolumab was introduced in the Netherlands in 2016 and is frequently administered in advanced melanoma patients with brain metastases due to the limited efficacy of anti‐PD‐1 in this setting. 20 The increase of BRAF/MEK inhibitors can be explained by the fact that they can be orally administered, reducing the need for hospital visits.

On 22 March 2020, the Dutch Association for Medical Oncology (NVMO) published a document containing advice for dealing with COVID‐19 and oncologic patients. 21 At the time, little to no scientific evidence existed on the influence of oncologic treatment on a SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. 22 Driven by the concern of a more severe course of COVID‐19 infection in patients simultaneously treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI), caution concerning ICI use was advised, together with the advice to consider postponing ICI or offer alternative treatment (such as targeted therapy). This advice from the NVMO has possibly contributed to our finding that for significantly more patients anti‐PD‐1 courses were postponed during the first wave. The regional differences in the number of patients postponing anti‐PD‐1 courses can be related to the regional differences in the number of COVID‐19 infections. As previously mentioned, the southern regions of the Netherlands were affected most severely by COVID. This would explain our finding that during the first wave significantly more anti‐PD‐1 courses were postponed in the southern regions than in the northern or middle regions. In line with the NVMO‐advice, we observed that most patients with postponed treatment courses started treatment more than 6 months before postponement. We did not observe a significant difference in the number of patients switching from ICIs to BRAF/MEK inhibitors in the absence of disease progression or severe toxicity.

For a study in Italy by Ottaviano et al, 23 a survey was sent to 75 medical oncologists. This survey focused on the adaptations during the COVID‐19 pandemic in the management of patients with solid tumors eligible for or receiving ICIs. This survey showed that 73.7% of the oncologists preferred a more extended ICI schedule during the COVID‐19 pandemic, compared to 47.4% before the pandemic. Ürün et al 24 surveyed 343 oncologists from 28 countries. They reported that around 50% of oncologists would increase the interval between treatments when prescribing ICIs compared to their practice before the COVID‐19 pandemic. De Joode et al 25 investigated the perspective on oncological care from Dutch cancer patients using an online survey of 5302 patients. Overall, for 30% of patients consequences for oncological treatment or follow‐up were reported. Immunotherapy was found to be the most frequently adjusted (32%), postponed (39%) and canceled (33%). According to the survey recipients, 12% of patients receiving systemic treatment had their treatment postponed. In our data, we found that 20% of anti‐PD‐1 courses were postponed. The results of these surveys are in line with our clinical findings that courses of immunotherapy were more often postponed during the COVID‐19 pandemic compared to the control period.

The first report on the numbers of cancer diagnoses in the Netherlands during the COVID‐pandemic was published by Dinmohamed et al. 26 They reported fewer cancer diagnoses between 6 January and 12 April 2020. Uyl‐de Groot et al 27 used data from the Netherlands Cancer Registry and the Dutch registry of histopathology and cytopathology (PALGA) to evaluate the magnitude of underdiagnosis. They observed a 20% to 40% decrease in the number of cancer diagnoses from the week of the first COVID‐19 diagnosis in the Netherlands, compared to the same period in 2019. The most significant reduction was found in the diagnosis of breast cancer and skin cancer. This research illustrates the importance of patient‐education and adapted melanoma screening campaigns to prevent delay in melanoma diagnosis and management during the COVID‐19 pandemic. 28 In line with our research, the southern parts of the Netherlands had the largest difference in cancer diagnoses in 2020 compared to 2019. Although we noticed a significantly smaller number of newly diagnosed advanced melanoma patients during the first COVID‐19 wave compared to the control period, we did not observe an increase in advanced melanoma diagnoses in the subsequent between‐wave period. This suggests that advanced melanoma is less commonly diagnosed throughout the pandemic which might be due to less frequent follow‐up or imaging by referring physicians and seems to result in more advanced disease in subsequently presenting patients. Another explanation might be the introduction of adjuvant therapy for stage III melanoma patients causing less stage migration to stage IV disease. Also, patients with mild symptoms might have presented themselves later while the patients with severe symptoms remained to visit the melanoma centers.

Until now, no study has described the effects of the COVID‐19 pandemic on advanced melanoma care. Our study shows the added value of a nationwide quality registry that enables monitoring differences in care between distinct time periods. Data in the DMTR are prospectively registered by data managers, who are trained annually. The online registration survey warns data managers if data are incomplete or inconsistent. All data are checked and confirmed by the patients' treating physicians. Therefore, we consider the data of the DMTR to be of high quality.

Our study does have some limitations. The observational nature of the DMTR could have introduced bias. Due to the limited follow‐up time, we could not assess outcomes of patients diagnosed during the second wave and progression‐free survival and overall survival of patients diagnosed in the first and second wave. Secondly, as most COVID‐tests are performed outside of the hospital, the DMTR does not contain reliable data about COVID‐19 infection in individual patients.

In conclusion, during the first COVID‐19 wave, we observed a decrease in patients diagnosed with advanced melanoma, a longer time between diagnosis and start of systemic therapy and a higher number of postponed anti‐PD‐1 courses. During the second COVID‐19 wave, we noticed a worsening of baseline characteristics, with more patients presenting with brain metastases and poorer performance status. Future studies are necessary to assess the long‐term consequences of our observed changes in advanced melanoma care.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Olivier J. Van Not, Jesper van Breeschoten, Doranne L. Hilarius, Melissa M. De Meza, Franchette W.P.J. van den Berkmortel, Jan Willem B. de Groot, Rawa K. Ismail, Ellen Kapiteijn, Djura Piersma, Rozemarijn S. van Rijn, Marion A.M. Stevense‐den Boer, Gerard Vreugdenhil, Marye J. Boers‐Sonderen, Willeke A.M. Blokx, Michel W.J.M. Wouters have declared no conflicts of interest. Alfonsus J.M. van den Eertwegh has advisory relationships Bristol Myers Squibb, MSD Oncology, Amgen, Roche, Novartis, Sanofi, Pfizer, Ipsen, Merck and Pierre Fabre and has received research study grants not related to this article from Sanofi, Roche, Bristol Myers Squibb, TEVA and Idera and has received travel expenses from MSD Oncology, Roche, Pfizer and Sanofi and has received speaker honoraria from Bristol Myers Squibb and Novartis. John B. Haanen has advisory relationships/consultancy work with or research grants not related to this article from BMS, Ipsen, Merck Serono, Molecular Partners, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sonofi, TRV and has advisory board honoraria from Achilles Therapeutics, BioNTech, Godeyo, Immunocore, Instil Bio, PokeAcell, T‐knife, Neogene Therapeutics and Asher Bio. All grants were paid to the institutions. Christian U. Blank has advisory relationships paid to the institute with BMS, MSD, Roche, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Astra Zenica, Pfizer, Lilly, GenMab, Pierre Fabre, advisory relationship with Third Rock Ventures, received research funding not related to this article from BMS, MSD, 4SC, Novartis and NanoString, holds stock ownership in Uniti Cars and is co‐founder of Immagene BV. Maureen J.B. Aarts has advisory board/consultancy honoraria from Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, MSD‐Merck, Merck‐Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Sanofi, Astellas, Bayer. Research grants Merck‐Pfizer. Not related to current work and paid to institute. Geke A.P. Hospers has consultancy/advisory relationships with Amgen, Roche, MSD, BMS, Novartis and Pierre Fabre and has received research grants not related to this article from BMS and Seerave. All grants were paid to the institutions. Astrid A.M. van der Veldt has consultancy relationships paid to the institution with Eisai, BMS, MSD, Merck, Roche, Novartis, Ipsen, Pfizer, Sanofi, Pierre Fabre. Karijn P.M. Suijkerbuijk has advisory relationships with Bristol Myers Squibb, Roche, Novartis, MSD, Pierre Fabre, AbbVie and received honoraria from Novartis and Roche. The funders had no role in the writing of this article or decision to submit it for publication.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The DMTR was approved by the medical ethical committee and was not deemed subject to the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act In compliance with Dutch regulations.

Supporting information

Appendix S1 Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For the Dutch Melanoma Treatment Registry (DMTR), the Dutch Institute for Clinical Auditing foundation received a start‐up grant from governmental organization The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMW, project number 836002002). The DMTR is structurally funded by Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Novartis and Roche Pharma. Roche Pharma stopped funding in 2019, and Pierre Fabre started funding the DMTR in 2019. For this work, no funding was granted.

van Not OJ, van Breeschoten J, van den Eertwegh AJM, et al. The unfavorable effects of COVID‐19 on Dutch advanced melanoma care. Int. J. Cancer. 2022;150(5):816‐824. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33833

Olivier J. Van Not and Jesper van Breeschoten contributed equally to this study.

Funding information The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMW), Grant/Award Number: 836002002; Bristol Myers Squibb; Les Laboratories Pierre Fabre; Merck Sharp and Dohme; Novartis Pharma; Roche Pharma

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of our study are available on request from the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. An interactive web‐based dashboard to track COVID‐19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(5):533‐534. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Burki TK. Cancer guidelines during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(5):629‐630. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30217-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mehta V, Goel S, Kabarriti R, et al. Case fatality rate of cancer patients with COVID‐19 in a New York Hospital System. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(7):935‐941. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rogiers A, Da Silva IP, Tentori C, et al. Clinical impact of COVID‐19 on patients with cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibition. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9(1):1‐11. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Villani A, Fabbrocini G, Scalvenzi M. The reduction in the detection of melanoma during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic in a melanoma center of South Italy. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1818674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ricci F, Fania L, Paradisi A, et al. Delayed melanoma diagnosis in the COVID‐19 era: increased breslow thickness in primary melanomas seen after the COVID‐19 lockdown. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(12):e778‐e779. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ministry of Health Welfare and Sport Man Diagnosed with Coronavirus (COVID‐19) in the Netherlands.; 2020. https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/kamerstukken/2020/02/27/kamerbrief‐eerste‐covid‐19‐patient‐in‐nederland. Accessed June 1, 2021.

- 8. National Institute for Public Health and the Environment . Ontwikkeling COVID‐19 in grafieken. 2021. https://www.rivm.nl/coronavirus-covid-19/grafieken. Accessed August 2, 2021.

- 9. Jochems A, Schouwenburg MG, Leeneman B, et al. Dutch melanoma treatment registry: quality assurance in the care of patients with metastatic melanoma in The Netherlands. Eur J Cancer. 2017;72:156‐165. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. STICHTING NICE . Total number of patients with proven of suspected COVID‐19 infection in the hospital; 2021. https://www.stichting-nice.nl/covid-19-op-de-zkh.jsp. Accessed August 16, 2021.

- 11. STICHTING NICE . Total number of patients with proven or suspected COVID‐19 infection on the Intensive Care Unit; 2021. https://www.stichting-nice.nl/covid-19-op-de-ic.jsp. Accessed August 16, 2021.

- 12. Ministry of Health Welfare and Sport . Kamerbrief over COVID‐19 nieuw maatregelen advies afstemmingsoverleg en internationale ontwikkelingen; 2020. https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/kamerstukken/2020/03/10/kamerbrief‐over‐covid‐19‐nieuwe‐maatregelen‐advies‐bestuurlijk‐afstemmingsoverleg‐en‐internationale‐ontwikkelingen. Accessed June 1, 2021.

- 13. R Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Core Team; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wickham H, Averick M, Bryan J, et al. Welcome to the {tidyverse}. J Open Source Softw. 2019;4(43):1686. doi: 10.21105/joss.01686 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yoshida K, Bartel A. Tableone: Create “Table 1” to Describe Baseline Characteristics with or without Propensity Score Weights; 2020. https://cran.rproject.org/package=tableone. Accessed March 1, 2021.

- 16. Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model. New York: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kassambra A, Kosinski M, Biecek P. Survminer: drawing survival curves using ggplot2, R package version 0.3 1; 2020.

- 18. Korber B, Fischer WM, Gnanakaran S, et al. Tracking changes in SARS‐CoV‐2 spike: evidence that D614G increases infectivity of the COVID‐19 virus. Cell. 2020;182(4):812‐827.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dutch Healthcare Authority . Analyse van de Gevolgen van de Coronacrisis Voor Verwijzingen Naar de Medisch Specialistische Zorg; 2020. https://puc.overheid.nl/nza/doc/PUC_623269_22/1/. Accessed June 1, 2021.

- 20. Long GV, Atkinson V, Lo S, et al. Combination nivolumab and ipilimumab or nivolumab alone in melanoma brain metastases: a multicentre randomised phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(5):672‐681. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30139-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Haanen JBAG. Indien mogelijk geen checkpointremmers. Med Oncol. 2020;2:50‐53. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Conforti C, Giuffrida R, Di Meo N, Zalaudek I. Management of advanced melanoma in the COVID‐19 era. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(4):13444. doi: 10.1111/dth.13444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ottaviano M, Curvietto M, Rescigno P, et al. Impact of COVID‐19 outbreak on cancer immunotherapy in Italy: a survey of young oncologists. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(2). doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ürün Y, Hussain SA, Bakouny Z, et al. Survey of the impact of COVID‐19 on Oncologists' decision making in cancer. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:1248‐1257. doi: 10.1200/go.20.00300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. De Joode K, Dumoulin DW, Engelen V, et al. Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on cancer treatment: the patients' perspective. Eur J Cancer. 2020;136:132‐139. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.06.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Avinash G, Dinmohamed OV, Verhoeven RHA, et al. Fewer cancer diagnoses during the COVID‐19 epidemic in The Netherlands. Lancet Oncol. 2020;4(6):750‐751. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30265-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Uyl‐de Groot CA, Schuurman MS, Huijgens PC, Praagman J. Fewer cancer diagnoses during the COVID‐19 epidemic according to diagnosis, age and region. TSG. 2020;99(1):1‐8. doi: 10.1007/s12508-020-00289-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Villani A, Fabbrocini G, Costa C, Scalvenzi M. Melanoma screening days during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic: strategies to adopt. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10(4):525‐527. doi: 10.1007/s13555-020-00402-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1 Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of our study are available on request from the corresponding author.