Abstract

Acute heart failure (AHF) affects millions of people worldwide, and it is a potentially life‐threatening condition for which the cardiologist is more often brought into play. It is crucial to rapidly identify, among patients presenting with dyspnoea, those with AHF and to accurately stratify their risk, in order to define the appropriate setting of care, especially nowadays due to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) outbreak. Furthermore, with physical examination being limited by personal protective equipment, the use of new alternative diagnostic and prognostic tools could be of extreme importance. In this regard, usage of biomarkers, especially when combined (a multimarker approach) is beneficial for establishment of an accurate diagnosis, risk stratification and post‐discharge monitoring. This review highlights the use of both traditional biomarkers such as natriuretic peptides (NP) and troponin, and emerging biomarkers such as soluble suppression of tumourigenicity (sST2) and galectin‐3 (Gal‐3), from patients' emergency admission to discharge and follow‐up, to improve risk stratification and outcomes in terms of mortality and rehospitalization.

Keywords: Acute heart failure, Biomarkers, Diagnosis, Risk stratification, Mortality, Follow‐up

Introduction

Heart Failure (HF) affects approximately 64 million people worldwide, with acute heart failure (AHF) being the leading cause of emergency hospitalization. 1 , 2

COVID‐19 outbreak has put the healthcare systems under an enormous stress worldwide, contributing to excess deaths from other causes, particularly attributable to cardiometabolic conditions. Indeed, a substantial reorganization of healthcare delivery occurred, with a higher risk of poor outcomes from HF and other cardiovascular diseases, because of a dramatic reduction of clinic activities and hospital admissions. 3

When dealing with AHF in the emergency setting, there are two main challenges clinicians have to face: the differential diagnosis and the identification of the optimal setting of care for the patients, whereby the latter one is often confounded by limited resources and patients' willingness to be hospitalized. Regarding the diagnosis of AHF, one of the major issues is the commonality of AHF with other conditions. The key symptom of AHF is dyspnoea, which is common among Emergency Department (ED), especially in the COVID‐19 era. Therefore, it becomes of vital importance for clinicians to rapidly confirm or exclude its cardiac origin. Once the diagnosis has been made, an appropriate risk stratification is essential for the optimization of patients' management and to define the appropriate setting of care, especially today with intensive care units overwhelmed by COVID‐19 patients.

In addition, thanks to their ability to report on a multitude of deleterious pathophysiological processes associated with unwanted remodelling of the heart, biomarkers allow clinicians to gain insight into the current condition of a given patient even remotely. Point‐of‐care tests have proven to be immensely useful in measuring biomarker levels at home, thus enabling the physician to establish remote diagnostics and appropriate risk stratification. The whole concept of point‐of‐care tests is to provide results in a short period of time at home or near patients' location. 4 Therefore, at this specific time when hospital visits are limited due to the pandemic, it is possible to achieve a good assessment of the clinical evaluation thanks to biomarkers.

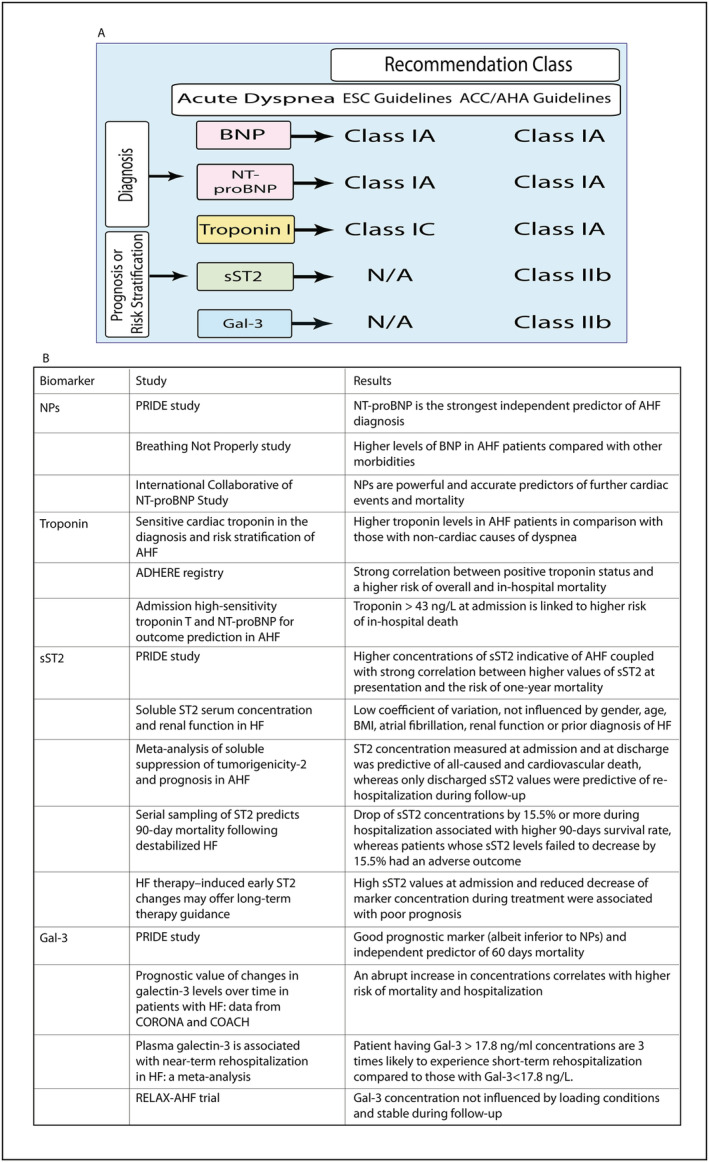

The latest European HF guidelines already suggest the use of natriuretic peptides (NPs) both in the diagnostic algorithm of AHF and to optimize patients' risk stratification (Figure 1 A ). On the other hand, the American College of Cardiology guidelines besides a strong recommendation of the use of NPs, suggest a multimarker approach composed of additional biomarkers that could be used in the combination with the already renowned NPs and high‐sensitivity troponin, such as soluble suppression of tumourigenicity (sST2) and galectin‐3 (Gal‐3), for the ability these biomarkers to provide additional information besides NPs in the prediction of patients' hospitalization and mortality risk. 5 , 6

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic representation of European HF guidelines and The American College of Cardiology guidelines regarding biomarkers coupled with classes of recommendations and level of evidence; (B) studies involving the biomarkers. AHF, acute heart failure; ADHERE, Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry; ACC/AHA, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association; BNP, B‐type or brain natriuretic peptide; CORONA, Controlled Rosuvastatin Multinational Trial in Heart Failure; COACH, Coordinating Study Evaluating Outcomes of Advising and Counselling Failure; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; Gal‐3, galectin‐3; HF, heart failure; NP, natriuretic peptides; N/A, not applicable; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro B‐type natriuretic peptide; PRIDE study, Pro‐Brain Natriuretic Peptide Investigation of Dyspnoea in the Emergency Department; sST2, soluble suppression of tumourigenicity; RELAX‐AHF trial, Relaxin in Acute Heart Failure trial.

Furthermore, in the context of a more personalized patients' management, the information provided by cardioverter‐defibrillators (ICDs), cardiac resynchronization therapy and defibrillator (CRT‐D), in cooperation with algorithms capable of assessing different aspects of HF, allows clinicians to monitor patients with cardiac disease continuously and even remotely. 7 The usefulness of the information emanating from these HF diagnostic devices together with CPT codes (current terminological procedure) has proven to be of the utmost importance for personal or remote monitoring of patients at monthly intervals. 7 Moreover, a recent study introduced a new HeartLogic algorithm to provide an alert index by combining signals obtained from HF diagnostic devices. 8 By integrating the information derived from electronic devices or HeartLogic index with those derived from biomarkers could further improve patients' assessment and stratification.

The aim of this review is to critically summarize the most recent findings in the area of AHF biomarkers currently used in clinical practice.

Traditional biomarkers

Natriuretic peptides

The most studied and widely accepted biomarkers in the diagnosis of AHF are NPs, which help in distinguishing patients with cardiac dyspnoea from those with non‐cardiac disease, 9 thanks to their high negative predictive value.

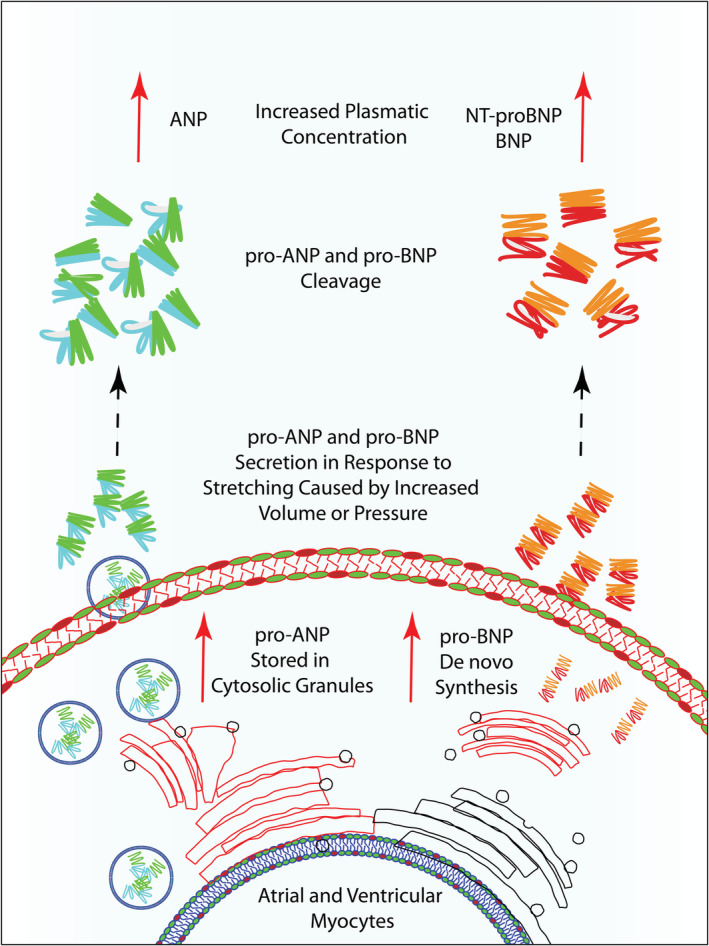

The NPs include atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), B‐type or brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), inactive form of BNP, N‐terminal pro B‐type natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP), C‐type and D‐type natriuretic peptides (Figure 2 ). 9 , 10 The ANP and BNP are secreted by atrial and ventricular myocytes respectively as a direct response to stretching caused by volume or pressure. 9 , 10 , 11

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of NPs upon myocyte stretching. ANP, atrial natriuretic peptide; BNP, B‐type or brain natriuretic peptide; NP, natriuretic peptides; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro B‐type natriuretic peptide.

Both ANP and BNP are synthesized as precursor propeptide pro‐ANP and pro‐BNP. The pro‐ANP is deposited in a reservoir of cytosolic granules and is released on demand whereas pro‐BNP is synthesized de novo as a response to ventricular stretching. Cleavage of pro‐ANP and pro‐BNP produces biologically active ANP and BNP and residual inactive N‐terminal fragments. 9 , 12 For diagnostic and prognostic purposes, the inactive terminal fragments are equally important as the active biological forms of NP. 12

It is indisputable that in the diagnostic sense, when referring to available markers, NPs represent irreplaceable biomarkers. In Breathing Not Properly study, it has been demonstrated that the concentration of BNP was higher in patients diagnosed with AHF compared with those who were not (Figure 1 B ). 13 Further, the PRIDE study (Pro‐Brain Natriuretic Peptide Investigation of Dyspnoea in the Emergency Department) showed that NT‐proBNP is the strongest independent predictor of AHF diagnosis, both alone or in combination with clinical judgement. Suggested cut‐off concentrations for diagnostic purposes by Januzzi et al. are for BNP above 100 pg/mL and for NT‐proBNP above 300 pg/mL. 14 , 15 Noteworthy, given that NT‐proBNP concentrations increase with age, age‐based cut‐points have been established, thereby, the optimal cut‐points for patients younger than 50 years are 450 and 900 pg/mL for the older ones. 16

Furthermore, BNP levels are higher in patients with HF treated with sacubitril, whose usage has become increasingly frequent in recent years, thus being NT‐proBNP more reliable in these patients, because its concentration is not influenced by these drugs. 9

Apart from diagnostic values, higher values of BNP and NT‐proBNP have been proven to be powerful and accurate predictors of further cardiac events and mortality. 16

The main drawback of NPs is their low specificity and high individual variability, because elevated NPs values could be the result of different factors such as age, body mass index, or other morbidities such as pulmonary or renal diseases. Moreover, approximately 20% of patients fall into a category characterized by intermediate or ‘grey zone’ NP values for which AHF cannot be excluded. 14 , 17 A possible condition where NPs leave space for misinterpretation is HF with preserved ejection fraction, where BNP values are in the 400–500 pg/mL range, making diagnosis and patients' management challenging. Those patients have a higher risk of morbidity and mortality, even though the BNP levels were low. 18 , 19

Last, it is worth noting a recent study by Aspromonte et al., which indicate that patients with low concentration level of BNP (<250 pg/mL) do not have to adhere regular visits 6 months after hospital discharge due to lower adverse events rate. These data are of extreme importance due to the current COVID‐19 pandemic situation, reducing the numbers of unnecessary exposure of the patients to the virus in hospitals. 20

Troponins

Troponin values can also be helpful in the diagnostic process of AHF because high plasma concentration of this biomarker suggests the presence of myocardial damage. Even if CK has been long used for identifying myocardial ischaemia, troponin is now the gold standard in the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction due to its higher sensitivity and specificity in acute setting, thus identifying even small myocardial damage. 9 , 21 , 22 In this context, troponin is released through different mechanisms, beyond the ischaemic aetiology of the disease. 9 Data from several studies show that elevated levels of troponin are strongly associated with left ventricular hypertrophy, as well as with poor outcome in AHF. 23 , 24 , 25 , 26

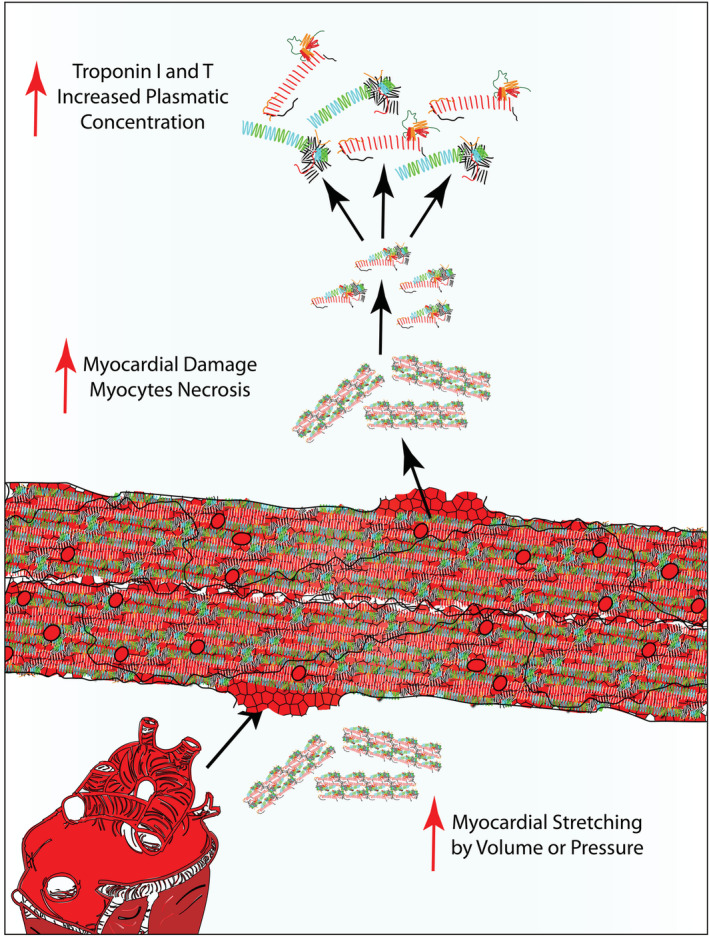

Troponin complex consists of three subunits I, T, and C, and it is one of the thin filament regulatory proteins involved in skeletal and cardiac muscle contraction and relaxation controlling the Ca2+ concentration (Figure 3 ). Troponin C is expressed in both cardiac and skeletal muscle, while troponin I and T are exclusively expressed only in cardiac myocytes and are released into the circulation upon myocyte necrosis. 27 , 28 This dissimilarity is used as an advantage in the development of rapid assays with the aim to detect elevated levels of cardiac troponin.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of troponin I and T release into the circulation upon myocyte necrosis or damage.

Troponin is usually undetectable or it is present at very low levels in patients with non‐AHF‐related dyspnoea. 9 , 22 , 26 In clinical practice, the detection of troponin relies on instrumental analytical sensitivity, which is currently guaranteed by high sensitivity assays. 25 , 29 , 30 New high sensitivity tests for troponin can detect low levels of circulating troponin with better accuracy than conventional ones. 31 However, troponin concentration levels could be influenced by different factors. Specifically, troponin I levels are significantly affected by age, sex, body mass index and systolic pressure, while troponin T by diabetes mellitus. 23 , 24 , 25 , 32 , 33 Many point‐of‐care devices for troponin measurement have been developed both as high sensitivity and non‐high sensitivity, which found their utility in ED. 29 , 30 However, there are concerns about their diagnostic accuracy. In fact, while some clinicians have reported high accuracy level, others have reported some interference with other pathologies, as previously mentioned. 23 , 24 , 25 , 32 , 33 , 34 It is worth noting that some troponin assays could, unfortunately, detect troponin C and therefore give false troponin‐positive results. However, along with technological advances, the troponin assays performance has been improved by eliminating heparin interference or cross‐reactivity with skeletal muscle. 35

Given that troponin levels are directly related to myocardial damage, they provide valuable information regarding risk stratification in patients with AHF. Not surprisingly, data from the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE), including 67 924 patients, demonstrated a strong correlation between positive troponin status and higher in‐hospital mortality. Moreover, when considering troponin concentration as a continuous variable, higher values were directly linked to higher risk of mortality. 36

Similarly, Arenja et al. performed troponin measurement in 667 patients presenting in ED with acute dyspnoea, demonstrating that troponin levels were higher in AHF patients in comparison with those with non‐cardiac causes of dyspnoea (P < 0.001). Particularly, in AHF patients with higher levels of troponin (≥28 ng/L), in‐hospital mortality increased up to 14% (P < 0.001), showing an association between troponin levels and fatal outcome. 37

In a more recent multi‐centre study including 1449 AHF subjects, Aimo et al. demonstrated that patients with troponin values above the median cut‐off of 43 ng/L at admission were at higher risk of in‐hospital death (P < 0.001). In addition, the risk was 2.7‐fold higher in patients having also NT‐proBNP levels higher than the median value of 5660 ng/L (relative risk (RR) 2.7, 95% CI 1.7‐4.5). Nevertheless, when assessing the prognostic value of both biomarkers in a multivariate model, only troponin levels ≥43 ng/L at admission were an independent predictor of all‐cause mortality at 6, 12, and 24 months after discharge. 38

Taken together, cardiac troponin measurement represents an useful marker for risk assessment of patients with AHF. 39 Nevertheless, troponin testing has some overall limitations. First, troponin elevation does not provide information regarding the pathophysiological process which leads to the myocardial injury. 40 Second, nonspecific troponin elevations are described in a variety of medical conditions which go beyond the cardiovascular system, including sepsis, stroke, severe pulmonary infections, and renal failure. 41 This can result in substantial issues of misinterpretation, raising the risk of inappropriate consultations with the cardiologist and pointless exams. Finally, in rare cases, there may be false positive results of troponin testing attributable to the presence in the bloodstream of heterophilic antibodies, rheumatoid factor or alkaline phosphatase, which can interfere with the high‐sensitivity troponin I dosage. 42 Consequently, patients affected by systemic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and mixed cryoglobulinemia who present to the ED with non‐cardiac chest pain or dyspnoea may be wrongly admitted to the Intensive Cardiac Care Unit, at times undergoing invasive exams, on the basis of falsely elevated values of troponin deriving from some modern immunoassays. 43

Emerging biomarkers

Soluble suppression of tumourigenicity 2

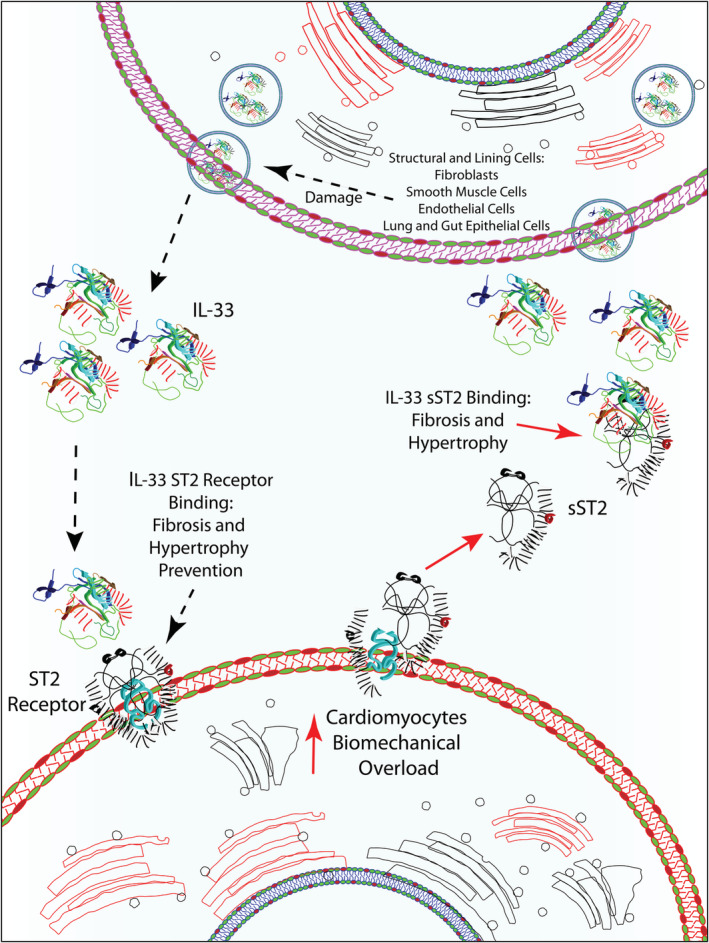

Among emerging biomarkers, sST2 is one of the most promising for clinical use. ST2 is a member of the interleukin (IL) receptor superfamily with transmembrane (ST2L or ST2 receptor) and a soluble isoform (sST2) (Figure 4 ). 44 The transmembrane isoform is the receptor of IL‐33, which is released by structural and lining cells such as fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, endothelial and epithelial cells of the lung and gut upon cell necrosis and damage. 45 , 46 Besides the cytokine role, IL‐33 acts as a nuclear factor and an alarmin. More precisely, IL‐33 is localized in the nucleus and acts as a transcriptional regulator, but upon necrosis or cell injury, it is quickly released from the cell into extracellular space where acts as an alarmin. 47

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of ST2 and sST2 and their involvement in fibrosis and hypertrophy. IL‐33, interleukin‐33; ST2, suppression of tumourigenicity; sST2, soluble suppression of tumourigenicity.

Apart from the role of IL‐33 in immunity and inflammation which has been widely studied, binding ST2, IL‐33 activates several cardioprotective pathways. 44 , 48 More precisely, IL‐33 prevents cardiac fibrosis and hypertrophy through nuclear factor‐κB (NF‐κB), myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88), interleukin‐1 receptor‐associated kinase (IRAK), and extracellular signal‐regulated kinase (ERK) signalling pathways. 44 , 49 , 50 Moreover, IL‐33 suppresses reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation induced by angiotensin II and therefore NF‐κB activation. 44 This pathway represents an adaptive response to mechanical overload in many cardiac diseases. 48

On the other hand, sST2 is a decoy receptor of IL‐33 preventing the interaction between IL‐33 and the ST2 receptor, thereby reducing its cardioprotective effects. Both ST2L and sST2 are overexpressed in cardiomyocytes in response to biomechanical overload; however, elevated concentration of sST2 has been found in various cardiac diseases such as myocardial infarction (MI), severe chronic heart failure (CHF), hypertension, diabetes, and AHF. 44 , 51 , 52 , 53 Therefore, it is suggested that the increase in circulating sST2 levels can be used as an indicator for neurohormonal activation, inflammatory, and haemodynamic stress. 54 , 55 , 56 In addition, higher levels of circulating sST2 were observed in patients with AHF compared with patients with CHF. 57 , 58 Specifically, increased sST2, as a result of myocardial stress, was related to HF severity and poor outcome, higher ventricular dilatation, and systolic dysfunction in people suffering from pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). 55 , 59 Worth mentioning, Ojji et al. demonstrated sST2 could be clinically useful in discriminating hypertensive patients (with and without left ventricular hypertrophy) from hypertensive HF. 60 In addition, the same study showed that sST2 could distinguish within a cohort of hypertensive patients, the individuals that developed left ventricular hypertrophy. The predictive value of sST2 to detect left ventricular hypertrophy, including very early stages of the remodelling process, has been confirmed by Huttin et al. in a recent large‐scale analysis. 61 Furthermore, higher sST2 values correlate with left ventricular concentric geometry phenotype in hypertensive patients. 62

Importantly, the serum concentration of sST2 has a low coefficient of intra‐individual variation, small relative change value, and it is not influenced by gender, age, body mass index, atrial fibrillation, renal function, or prior diagnosis of HF. 48 Although conducted in the CHF setting, Piper et al. first examined the biological variability of sST2 among patients with CHF, taking blood samples at different time points (baseline, 1 hour, 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months), demonstrating significantly lower coefficients of variation and reference change values for sST2 compared with NT‐proBNP. 63

Plasma levels of sST2 have been shown to predict AHF both alone and in association with gold standard biomarkers, such as cardiac troponins and NP, 57 , 64 as well as in long‐term prediction of hospitalization during 1 year follow‐up and death. 65 , 66

First data on the use of sST2 came from the PRIDE study (Pro‐Brain Natriuretic Peptide Investigation of Dyspnoea in the Emergency Department) which evaluated sST2 concentration in 593 patients admitted to the ED with dyspnoea. Even though the study revealed that patients with AHF had significantly higher concentrations of sST2 than those without (P < 0.001), its diagnostic potential in identifying AHF turned out to be inferior in comparison with NPs. 67 However, sST2 has been proven to be a powerful prognostic biomarker with additive value to NPs. In fact, this study reported a strong correlation between higher values of sST2 at presentation and the risk of 1 year mortality for both dyspnoeic patients with and without HF. 14 , 67 , 68 Many subsequent studies and meta‐analyses confirmed the correlation between sST2 concentration and a higher risk of adverse events. 48 , 67 Namely, Aimo et al. performed a meta‐analysis including a population of 4835 patients with AHF from 10 studies with a median follow‐up of 13.5 months. This study demonstrated that sST2 concentration measured at admission and at discharge was predictive of all‐cause and cardiovascular death, whereas only discharged sST2 values were predictive of re‐hospitalization during follow‐up. 65 This latter finding is extremely important because few biomarkers have achieved this goal so far. 69

Furthermore, sST2 levels are highly dynamic over the short‐term period upon admission and given its low biological and analytical variability, it is suitable for serial measurements during in‐hospital observations. 70 Boisot et al. performed serial measurement of sST2 in AHF patients from admission in ED to discharge, showing that changes in sST2 levels were predictive of 90 days all‐cause mortality. A drop of sST2 concentrations by 15.5% or more during hospitalization was linked to a better prognosis over 90 days follow‐up (RR 7%), whereas patients whose sST2 levels failed to decrease by 15.5% had an adverse outcome (RR 33%). 71 In another study, Breidthardt et al. obtained similar results measuring the sST2 concentration among patients with AHF upon presentation to the ED and 48 h after the start of the treatment, proving once again that serial measurements of sST2 are independent predictors of 1 year mortality in acute settings. 72 Specifically, the study showed that a poorer prognosis was associated with higher sST2 values on admission and that the percentage alteration of sST2 during the first 48 hours significantly predicted long‐term mortality as well, both in univariate analysis and after adjustment for several clinical risk factors such as traditional HF biomarkers, markers of inflammation or ADHERE risk factors. 72 Moreover, Van Vark et al. showed that in patients presenting at ED, sST2 values higher than 70 ng/L and maintained over 48–72 h of treatment as well as a decrease of biomarker levels lower than 30% were indicative of worse prognosis. Last, the same study showed that sST2 measurement during the follow‐up of patients has the potential to predict further cardiac deterioration, as increased levels of this biomarker was observed several weeks (approximately 45 days according to the graphic provided in the study) before a cardiac event. 73

Galectin‐3

The last biomarker whose measurement is suggested by the American HF Guidelines is Gal‐3, 6 a member of the galectin family, with an evolutionarily conserved carbohydrate‐recognition domain that specifically binds β‐galactosides. Gal‐3 is ubiquitous and can be found in a variety of cell and tissue types, especially in epithelial and endothelial cells, in all types of immune cells, as well as in sensory neurons. 74 In a cardiac setting, Gal‐3 has been proposed as a useful tool in the diagnosis of AHF because its expression is low in the normally functioning heart, while it increases in the case of HF. In fact, despite Gal‐3 shows anti‐apoptotic and anti‐necrotic function in the healthy heart, its prolonged overexpression in HF is associated with fibrosis, adverse remodelling, atherosclerosis, and inflammation. 75 , 76 , 77

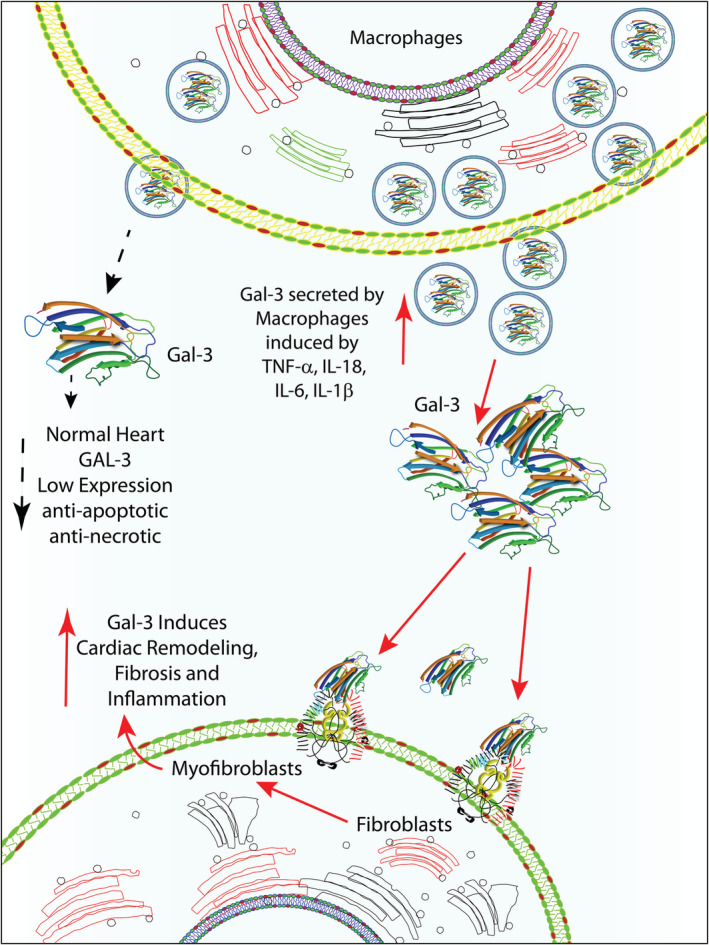

Along with previous facts, it has been observed that during HF, Gal‐3 overexpression in cardiac tissues is associated with increased fibroblast and macrophage activity (Figure 5 ). 78 , 79 It has been established that after myocardial injury, pro‐inflammatory cytokines such as TNF‐α, IL‐18, IL‐6, and IL‐1 β, released by cardiomyocytes, lead to macrophage activation. Thereafter, Gal‐3, produced by stretched macrophages, promotes the differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts both through a transforming growth factor (TGF)‐β1‐dependent and ‐independent pathway. 80 Myofibroblasts, in turn, are responsible for the increased production of extracellular matrix and the imbalance between matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors, favouring the development of systolic and diastolic dysfunction and leading to adverse remodelling of the heart. 80 Noteworthy, even though, Gal‐3 seems mainly involved in fibrosis it has been established that it is also related to the beginning and development of the inflammatory process that accompanies HF, sustaining the inflammatory process via cardiotrophin‐1. 76

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of Gal‐3 role in cardiac remodelling. Gal‐3, galactin‐3.

As for sST2, the first data on the use of Gal‐3 in the setting of AHF come from the PRIDE study, where Gal‐3 proved to be complementary to the information provided by NPs in the diagnostic process. 14 , 81 Gal‐3 was found to be a good predictor of 60 days mortality even after adjustment at multivariate analysis. 81 In a meta‐analysis by de Boer et al., HF patients with Gal‐3 levels above 17.8 ng/mL, turned out to be nearly 3 times as likely to experience short‐term rehospitalization as compared with those with Gal‐3 levels lower than 17.8 ng/L. Similar results were found regarding mortality. 82 Furthermore, an abrupt increase in Gal‐3 concentrations have been found to correlate with an increased risk of mortality and hospitalization. 83

In a recent investigation conducted to assess the ability of Gal‐3 and other serum biomarkers to detect patients with preclinical left ventricular remodelling and diastolic dysfunction, Huttin et al. have found that Gal‐3 should represent an accurate predictive tool for HF with preserved ejection fraction. Indeed, in a large population‐based cohort, Gal‐3 showed the highest discrimination value for preclinical diastolic dysfunction compared with BNP and sST2. 61

However, it is important to mention that Gal‐3 in combination with other established biomarkers have a higher prognostic value than taken into consideration alone. Gal‐3 in combination with NT‐proBNP significantly improved discrimination and reclassification when predicting all‐cause mortality. Further, sST2 and Gal‐3 together provide a better risk stratification value identifying systemic fibrosis in AHF patients. 84

In addition, plasma Gal‐3 levels correlate with age, body mass index, sex, renal dysfunction, diabetes and hypertension. 85 Wu et al., performed serial measurement of sST2 and Gal‐3 at different time points (every 2 weeks for sST2 and hourly for Gal‐3), with the aim to evaluate their analytical, intraindividual and interindividual variation, demonstrated that reference change of sST2 was lower in comparison with Gal‐3 and other biomarkers such as BNP, NT‐proBNP, troponin I and T (Table 1 ). 70 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 Moreover, the same group concluded that sST2 might be suitable for long‐term monitoring of patients with HF, while Gal‐3 for the diagnostic of heart remodelling. 70 Furthermore, Gal‐3 has low biological variability in both healthy individuals and patients with HF. 90 , 91 In a recent study, Demissei et al. performed a serial measurement of several biomarkers including NT‐proBNP, troponin, sST2 and Gal‐3 at different time points (baseline, day 2, day 5, day 14, and day 60) among patients with AHF, proving that only Gal‐3 values were constant over time. 91 Therefore, alterations in Gal‐3 levels are an indicator of underlying pathophysiological processes that could lead to a poor prognosis. Thus, elevated Gal‐3 levels, together with clinical and instrumental data could support more aggressive therapeutic strategies, including heart transplantation or ventricular assist device (VAD).

Table 1.

Biological variability of biomarkers

| Biomarker | Duration | Intraindividual variance | Interindividual variance | Reference change | Reference no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NT‐proBNP | 2 months | 33% | 36% | 92% | 86 |

| BNP | 2 months | 50% | 28% | 138% | 86 |

| Troponin T | 1 months | 31% | 32% | 87% | 87 |

| Troponin I | 2 months | 28% | 71% | 73% | 88 |

| sST2 | 1,5 months | 10.5% | 46,4% | 30% | 89 |

| sST2 | 2 months | 11% | 46% | 30% | 70 |

| Gal‐3 | Hourly | 16% | 16% | 39% | 70 |

| Gal‐3 | 2 months | 20% | 23% | 61% | 70 |

BNP, B‐type or brain natriuretic peptide;Gal‐3, galactin‐3; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro B‐type natriuretic peptide; sST2, soluble suppression of tumourigenicity.

Other promising biomarkers in acute heart failure

In addition, there are several promising diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers that are paving their way in the cardiovascular field such as growth‐differentiation factor 15 (GDF‐15), plasma midregional proadrenomedullin (MR‐ProADM), cystatin C, and neutrophil gelatinase‐associated lipocalin (NGAL). 92

GDF‐15 is a member of the transforming growth factor β (TGF‐β) cytokine family that is associated with an inflammatory state. 93 In AHF settings, elevated GDF‐15 levels are related to higher risk of adverse outcome. 94 In a recent study, Bettencourt et al. demonstrated in a cohort of 158 patients with AHF that increased values of GDF‐15 correlated with higher mortality risk independently of BNP. Furthermore, the mortality risk was four‐fold higher in patients with elevated levels of both biomarkers, GDF‐15 and BNP in comparison with those without. 95

In the same context, another biomarker whose prognostic ability is independent of NPs is MR‐ProADM. MP‐ProADM is a stable fragment of pro‐adrenomedullin, the precursor of adrenomedullin (ADM), a hormone with natriuretic, vasodilatory, and hypotensive role whose alter concentrations are associated with hypertension and HF, as well as renal disease. 96 In fact, the evaluation of MP‐ProADM levels in serum corresponds to the ADM concentration because its direct measurement is not possible due to the short half‐live. 96 , 97 Biomarkers in Acute Heart Failure (BACH) trial which involved 568 patients with AHF showed that MP‐ProADM concentration levels were superior to NPs in predicting worse outcome within 14 days, as well as that biomarker concentration had additive value to NPs in predicting adverse outcome within 90 days. 96

Cystatin C is a marker of renal function, representing an emerging biomarker in the cardiovascular field. Its prognostic potential in AHF settings has been evaluated for the first time in a study by Lassus et al., which included 480 patients with AHF, demonstrating a strong prognostic value of cystatin C in terms of in‐hospital mortality and during follow‐up. Furthermore, the study showed that the risk stratification of the patient improved when considering cystatin C and NT‐proBNP levels jointly. 98 A recent study by Breidthardt et al. confirmed the prognostic potential of cystatin C as a biomarker in acute settings independent of BNP, although providing additive prognostic information to BNP. 99

Lastly, NGAL is a marker of acute renal tubular injury, which is frequent among patients with AHF and is associated with morbidity and mortality. 100 , 101 In a study including 91 AHF patients, Aghel et al. demonstrated that elevated levels of NGAL at admission were associated with a high risk of worsening renal function. 100 Furthermore, a more recent study showed that higher NGAL values were independent predictors of all‐cause mortality at 12 months follow‐up. 101

Usefulness of point of care biomarker testing and remote monitoring during the follow‐up

Once the patient has been stabilized and discharged, the main task is to plan an adequate follow‐up along with prevention of new exacerbations of AHF. Recent evidences suggest that the use of biomarkers can help clinicians also in these settings, suggesting that periodical measurement of biomarkers during regular medical visit should be mandatory.

Noteworthy, interpretation of NPs must be undertaken with care due to their low specificity which means elevated NPs values levels could be the result of other morbidities. 14 , 17 On the other hand, troponin provides useful information regarding myocardial necrosis and AHF patients with positive troponin status are associated with worse outcomes. 36 Among these new biomarkers, sST2 and Gal‐3 showed strong correlation with patients' outcome because they reflect pathophysiological processes linked to an adverse cardiac remodelling such are inflammation and fibrosis. Given their lower biological variation compared with NPs, sST2, and Gal‐3 might be better markers for patient follow‐up and to guide therapy. 48 , 63 , 90

Usefulness of point‐of‐care tests

The clinical application of point‐of‐care tests have proven to be very successful in remote monitoring of patients. Therefore, point‐of‐care tests could be especially beneficial during COVID‐19 pandemic when self‐isolation is recommended. Many point‐of‐care tests nowadays rely on biosensors devices that allow the measurement of BNP, NT‐proBNP and troponin in a few minutes. Because traditional biomarkers are extremely important in AHF, it is not surprising that several biosensors have already been tested and widely used in clinical practice. For instance, RAMP Cardiac Troponin I Test and Ramp NT‐proBNP Test (Response Biomedical, BC, Canada) evaluate concentrations levels of troponin I and NT‐proBNP in 15 min, whereas portable Cobas h232 POC system (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) allows assessment of several biomarkers as well, among them troponin T and NT‐ proBNP in a whole blood in 12 min. 102

As far as sST2 measurements are concerned, the PRESAGE ST2 and ASPECT‐PLUS ST2 tests (Critical Diagnostics, San Diego, CA, USA) are currently widely used due to their accuracy. 103 ASPECT‐PLUS ST2 and the ASPECT reader have proven to be very useful in rapidly measuring sST2 in human plasma, as it takes only 35 minutes to prepare a sample and interpret the results. 104 The disadvantage of both tests is the reliance on laboratory equipment. In addition, there is the Aspect‐LF test (Life Biomedical, Cambridge, UK) made as a disposable cartridge, which uses whole blood from a finger to rapidly measure sST2 concentration for home use. 105

In same context, several Gal‐3 tests, such as ARCHITECT Galectin‐3 (Abbott Diagnostics, IL, USA) and BGM Galectin‐3TM (BG Medicine, MA, USA), have been shown to be useful in medical practice. 106 , 107 However, reliance on blood samples limits its use at home. In a recent study, Zhang et al. showed that Gal‐3 concentrations measured in saliva have prognostic potential and might be an option for a noninvasive sampling method. However, also in this context, more studies are needed to confirm these results. 107

In practice, patients in possession of point‐of‐care devices, especially those in the form of a cartridge that are easy to use, are able to independently measure and communicate results to the clinician via telephone. This approach would be very beneficial during the COVID‐19 pandemic when self‐isolation is advised. However, in some cases, unfortunately, because point‐of care tests are not accessible to everyone or need a specific training to be employed, a nurse could visit the patients on a physician's demand to perform point‐of‐care test or collect blood/saliva samples for tests requiring laboratory equipment (such as ELISA).

Worth mentioning, given the proven value of biomarkers in stratifying patients' risk, there is of utmost necessity to adjust clinical predictive score with biomarkers' levels, especially in cases when many clinical features of AHF (such as dyspnoea) could be worsened or misinterpreted in the setting of severe acute respiratory syndrome (e.g. SARS‐CoV‐2).

Usefulness of the HeartLogic alert index coupled with biomarker measurements

A promising role in the field of home monitoring belongs to cardiac devices, particularly nowadays with remote monitoring being sometimes the only solution due to the overload of hospitals with COVID‐19 patients. In fact, because non‐invasive methods, such as scheduled phone calls, have failed to impact on hard outcomes, it was suggested that ICDs, CRTs, and pacemakers, collectively called cardiac implantable electrical devices (CIEDs), 108 could be useful for this purpose. However, numerous clinical trials assessing the impact of CIEDs in the management and early detection of HF turned out to be inconclusive. This was largely due to the fact that the extraction of data was episodic and that these data were affected by numerous variables. 109 , 110 For instance, the OptiVol system by Medtronic, which was developed to monitor intrathoracic impedance in patients with InSync Sentrycardiac resynchronization therapy‐defibrillator, Concerto cardiac resynchronization therapy‐defibrillator, and Virtuoso implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator devices, aimed at recognizing early signs of fluid retention before the appearance of symptoms, has shown to be very sensitive but lacked specificity. 111 , 112 , 113

Recently, new multisensory algorithms associated to CIEDs have been introduced. These new algorithms constantly monitor physiological parameters using a multiplicity of sensors and have been demonstrated to be helpful in predicting HF patients' hospitalization needs. 7 , 114 , 115 , 116 In the recent MultiSENSE study (Multisensor Chronic Evaluation in Ambulatory Heart Failure Patients study), a novel algorithm for HF monitoring, called HeartLogic (Boston Scientific), was provided. This is a composite alert index which combines data from CIEDs' sensors chosen to target the different aspects of HF pathophysiology. In fact, through monitoring heart sounds, respiration, thoracic impedance, heart rate, and global patient activity, the HeartLogic index has proved to detect HF events with high sensitivity and earliness. 8 , 116 , 117 Because the specificity of these devices is still not optimal, we suggested that information derived from biomarkers' levels during follow‐up could be combined with those derived from multisensory algorithm associated to CIEDs in order to improve patients' risk stratification.

A post hoc analysis from the MultiSENSE study showed that HeartLogic alerts notably increased the predictive power of NT‐proBNP levels for the early notification of worsening heart failure. 8 Finally, in a direct comparison, HeartLogic demonstrated similar diagnostic accuracy of NT‐proBNP to rule out AHF in acute settings. 118

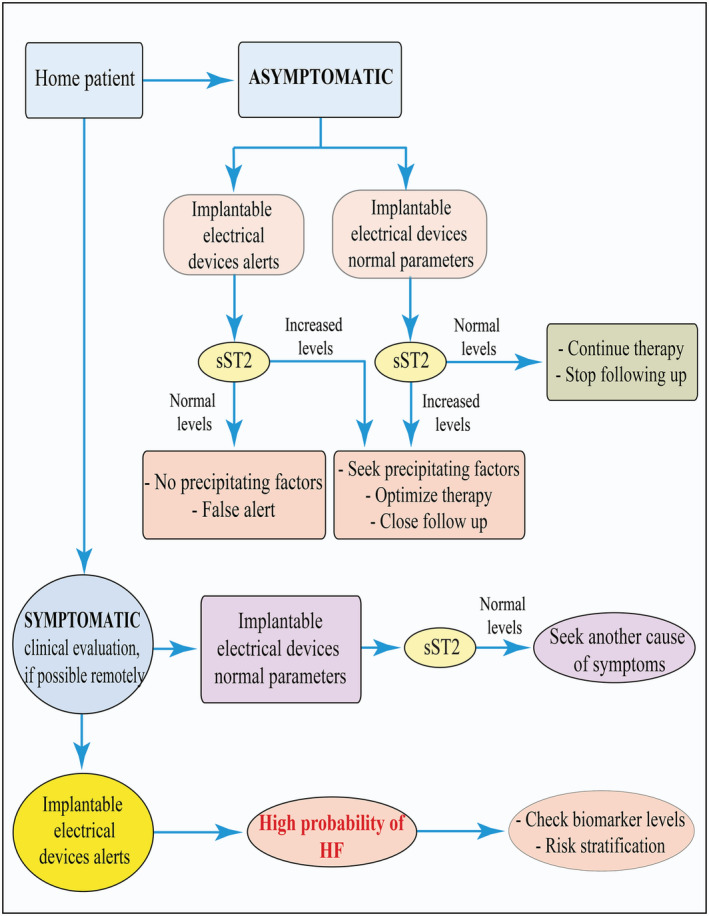

In practice, for instance, if a patient is totally asymptomatic and HeartLogic device shows normal parameters, the detection of normal levels of biomarkers could reassure the physician on patient's stability, so that the time between one visit and the other can be prolonged and the therapy left unchanged. However, if in the same asymptomatic patient with normal HeartLogic parameters high level of sST2 is detected, this should raise concerns. The physician should empower the therapy and plan a closer follow‐up, because, as mentioned earlier, it was shown that sST2 has the potential to predict cardiac deterioration as increased levels of this biomarker are observed several weeks before a cardiac event. 84 Furthermore, the detection of high levels of sST2 together with a decrease in thoracic impedance or other HeartLogic parameters associated with worsening HF increases the positive predictive value of these tools and should lead the clinician to investigate if there are any specific precipitating factors to be promptly addressed and to adjust the therapy, even if the patient is still asymptomatic. 118 Conversely, the detection of normal sST2 levels in an asymptomatic patient whose HeartLogic device shows abnormal parameters reduces the probability of a real worsening of HF and suggests a false alert. In the case of a patient reporting symptoms of worsening HF data deriving from both HeartLogic and cardiac biomarkers could help the clinicians to decide, after a first clinical assessment, when possible remote, whether the patient can be managed remotely or needs a visit. In Figure 6 , we suggest a possible algorithm for a remote combining the use of HeartLogic device and biomarkers, although further clinical studies are needed to validate this approach.

Figure 6.

Flow diagram demonstrating remote monitoring and controlling for in‐home patients with HF risks. HF, heart failure; sST2, soluble suppression of tumourigenicity.

Therefore, by implementing information derived from HeartLogic together with those of biomarkers would increase the accuracy of the remote follow‐up possibly leading to a reduction of hospital accesses and an early prediction of HF reactivation, even before symptom onset. This would be of extreme importance especially in the COVID‐19 era that is characterized by a strong limitation of regular hospital visits. Organized in‐home visits by nurses with the aim to draw blood and measure sST2 would be an amazing improvement in follow‐up as well. However, being to date the use of these algorithms limited among patients, this approach may be applied only in a limited number of cases. In addition, the HeartLogic‐based telemonitoring is available only for patients implanted with Boston Scientific devices, thus further limiting its use in daily clinical practice.

Other implantable devices which proved to be promising in the management of HF patients are those monitoring pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) changes, being a rise in ventricular filling pressure the key pathophysiological mechanism of acute decompensated HF. Among these devices the one which proved to be more successful is CardioMEMS, a wireless pressure sensitive device which is implanted in the distal pulmonary artery and monitors changes in PAP. This device demonstrated to be a useful guide in the management of HF, leading to a reduction in hospitalization rates. The advantage monitoring PAP relies in the evidence that its changes precede the changes in thoracic impedance by several days. Based on reliable data from the CHAMPION trial, 119 CardioMEMS HF System is the only device to have been added to the ESC guidelines (class of recommendation IIb) as a telemonitoring and guiding‐therapy tool for HF patients.

Despite the first optimistic data about CardioMEMS, its use is limited and, especially due to the current cost of the device, it must be implanted in selected patients. Furthermore, there are ongoing studies aimed at establishing the reproducibility and long‐term validity of earlier results. 120 , 121 , 122

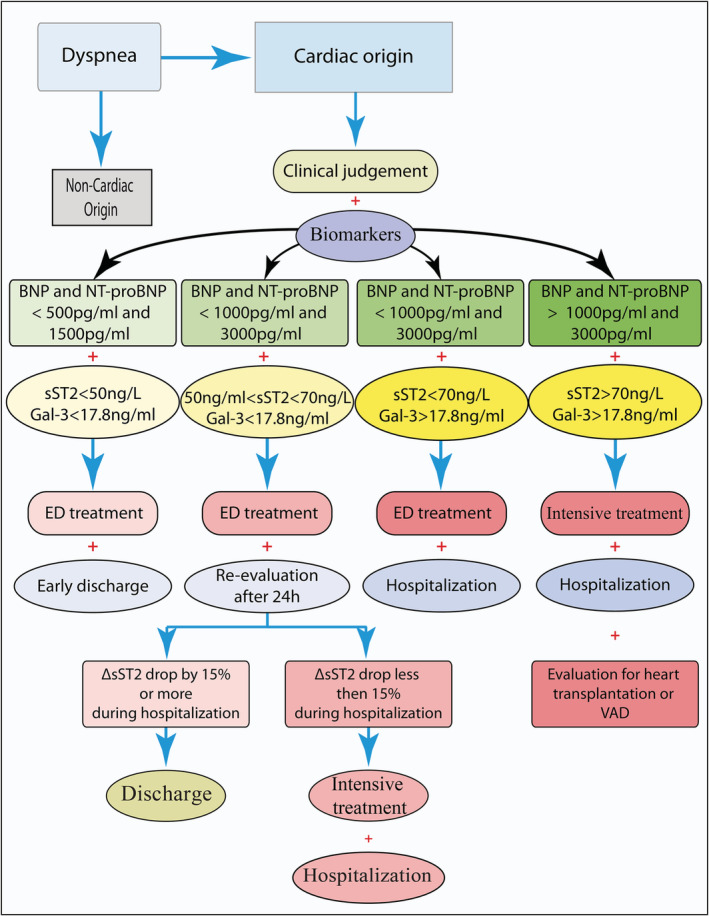

Putting all together

In the setting of AHF the main goals in patient management are a rapid diagnosis and a precise stratification. Sublimating all of the aforementioned information and in an effort for better use of the available data, we propose a standard operating procedure flowchart schematized in Figure 7 .

Figure 7.

Flow diagram demonstrating the usefulness of multimarker approach for finer patient's management and decision‐making process in the ED. BNP, B‐type or brain natriuretic peptide; ED, emergency department; Gal‐3, galectin‐3; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro B‐type natriuretic peptide; sST2, soluble suppression of tumourigenicity; VAD, ventricular assist device.

When facing a patient presenting to the ED with acute dyspnoea, the first challenge is to rapidly establish the underlying cause. Medical history and physical examination, in addition to bio‐humoral tests, can lead to the correct diagnosis, often revealing a cardiac origin of the respiratory symptoms. In addition, ultrasonography has proved useful for the emergency diagnosis of AHF, especially with respect to heart ultrasound. Nonetheless, echocardiography often requires dedicated and time‐dependent training, being a prerogative of cardiologists. On the contrary, lung ultrasound is a quick, reproducible and easy‐to‐use exam for every physician working in the emergency setting. 123 This powerful tool provides an accurate pulmonary congestion assessment in AHF patients, essentially quantifying sonographic B‐lines. Furthermore, lung ultrasound helps to stratify prognosis of AHF patients, thus its systematic use should be strongly encouraged. 124

The most useful biomarkers in the diagnostic phase are doubtlessly NPs which can rule out a cardiac condition when negative. Once the diagnosis has been made, other biomarkers contribute to define the severity of the clinical pattern, helping the clinician to indicate the adequate setting of treatment for each patient. Particularly, patients with NT‐proBNP, BNP, sST2 values above 3000 pg/mL, 1000 pg/mL, 70 ng/L, respectively, which remains constantly elevated even after 72 hours of treatment, as well as those with Gal‐3 levels above 17.8 ng/mL have to be considered at high risk and hospitalized in order to perform further analysis for an accurate diagnosis and monitor the patients in person. In fact, high levels of Gal‐3, alone or in association with other biomarkers, are highly indicative of an irreversible worsening of patient's condition for whom an immediate hospitalization should be considered. For this reason, elevated levels of these biomarkers could also lead (together with other factors) the clinician to consider invasive therapies such as heart transplantation or VAD, both as a bridge to heart transplantation or as a ‘destination therapy’.

Finally, patients in a ‘grey zone’ with intermediate levels of NPs (higher‐than‐normal but below 1000 pg/mL for BNP and 3000 pg/mL for NT‐proBNP) and sST2 values between 35‐70 ng/mL should be observed in ED and re‐evaluated after 24 h. Lastly, whenever values of all biomarkers are under the mentioned thresholds, patients are identified as ‘low risk’. For these, after the initial stabilization an early discharge should be considered.

In addition, during chronic follow‐up a gradual increase of sST2 concentration or/and an increase of more than 15% in Gal‐3 values should prompt medical attention because it predicts a worsening of patients' conditions. Also, in these settings, these parameters may influence the clinician's decision towards invasive therapies such as VAD or heart transplantation (both as a ‘bridge’ or ‘destination’ therapy), as mentioned earlier.

COVID‐19 infection and cardiac biomarkers

In addition to the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on the care of uninfected patients with HF, two other aspects must be considered. First, HF patients as well as those with other cardiovascular comorbidities have been found to be at increased risk for severe COVID 19 disease and complications of infection, 125 and worse outcome. 126 Specifically, in a recent comparative risk assessment analysis from the USA, nearly two‐thirds of COVID‐19‐related hospitalizations among US adults were estimated to be attributable to four major cardiometabolic conditions, including HF. 127

Second, myocardial injury is frequent in patients with severe COVID‐19, presenting a multifactorial origin. Severe hypoxia in the context of respiratory distress syndrome, 128 pre‐existing coronary plaque disruption, 129 microvascular thrombosis, 130 and direct virus‐induced cytotoxicity 131 appear the most important underlying pathophysiological factors. Accordingly, the development of HF represents a shared consequence of these mechanisms, with a negative impact on patients' prognosis. 132 , 133 , 134 From this point of view, cardiac biomarkers have been suggested to play a major role in predicting the prognosis of patients with COVID‐19 infection, thus indicating the need for more intensive monitoring and more aggressive treatment. A large retrospective study demonstrated an association between elevation of cardiac biomarkers (troponin, creatine kinase‐MB (CK‐MB), NT‐proBNP or myoglobin) and both increased risk of 28 day all‐cause mortality and more severe symptoms and disease progression. 135 In another recently published article, high concentrations of CK‐MP, procalcitonin, NT‐proBNP, BNP, troponin, and D‐dimers have been shown to predict severity and survival for patients with COVID‐19 as well. 136 Several other studies have confirmed the relationship between high troponin values and a worse prognosis in patients with COVID‐19 infection. 126 , 137 , 138 , 139 It is still not clear whether this relationship is due to a more severe form of COVID‐19 or to a more extensive cardiac damage or both. 135 Troponin elevation during SARS‐COV‐2 infection can be underpinned by several causes. Despite myocarditis, stress cardiomyopathy, and myocardial infarction are well‐recognized mechanisms, the largest percentage of myocardial injury appears attributable to primary noncardiac conditions, such as pulmonary embolism, critical illness, and sepsis. 132

At the same time, no established therapies exist for myocardial injury associated with COVID‐19; however, dosing these biomarkers is a useful tool to stratify patients' risk and therefore predict a more severe course of the disease and the need for a more aggressive approach such as invasive mechanical ventilation. 137 , 138 In addition, Yuan et al. conducted a study involving patients with COVID‐19 infection with the aim of investigating whether biomarkers may indicate safe delay in transthoracic echocardiography until the risk of infection recedes. The study proved that troponin and BNP levels were highly correlated with urgent need for transthoracic echocardiography. 140

Concerning emerging biomarkers, it has been shown that MR‐ProADM, GDF‐15, and Cystatin‐C are strong predictors of COVID‐19 outcome, further reinforcing their potential usefulness in the clinical arena.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the use of biomarkers in the cardiovascular field has increased tremendously in the last decades. Given their ability to reflect pathophysiological events coupled with a strong predictive value, biomarkers are on the way to become essential tools in diagnosis and risk stratification of patients with cardiovascular diseases. In the setting of AHF, when a rapid assessment of the patients is mandatory, readily available biomarkers, with clear and fixed cut offs, able to confirm the diagnosis and to stratify patients' risk, are of great help for the physicians. The choice of when and which biomarker to dose depends on the information needed by clinicians. Biomarkers are not a substitute of patients' clinical assessment but provide important information thanks to their ability to reflect different pathophysiological processes and therefore paving the way to precision medicine.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

This work was supported by Regione Friuli Venezia Giulia (grant for the project ‘Lo scompenso cardiaco quale morbo di Alzheimer del cuore: opportunità diagnostiche e terapeutiche—HEARTzheimer’).

Aleksova, A. , Sinagra, G. , Beltrami, A. P. , Pierri, A. , Ferro, F. , Janjusevic, M. , and Gagno, G. (2021) Biomarkers in the management of acute heart failure: state of the art and role in COVID‐19 era. ESC Heart Failure, 8: 4465–4483. 10.1002/ehf2.13595.

Milijana Janjusevic and Giulia Gagno contributed equally to the study.

References

- 1. Lippi G, Sanchis‐Gomar F. Global epidemiology and future trends of heart failure. AME Med J. 2020; 5: 15. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Farmakis D, Papingiotis G, Parissis J. Acute heart failure: epidemiology and socioeconomic burden. Contin Cardiol Educ. 2017; 3: 88–92. [Google Scholar]

- 3. DeFilippis EM, Reza N, Donald E, Givertz MM, Lindenfeld J, Jessup M. Considerations for Heart Failure Care During the COVID‐19 Pandemic. JACC Heart Fail. 2020; 8: 681–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Luppa PB, Muller C, Schlichtiger A, Schlebusch H. Point‐of‐care testing (POCT): Current techniques and future perspectives. Trends Analyt Chem. 2011; 30: 887–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JG, Coats AJ, Falk V, González‐Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GMC, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer P. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016; 18: 891–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Colvin MM, Drazner MH, Filippatos GS, Fonarow GC, Givertz MM, Hollenberg SM. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; 70: 776–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Whellan DJ, Ousdigian KT, Al‐Khatib SM, Pu W, Sarkar S, Porter CB, Pavri BB, O'Connor CM, PARTNERS Study Investigators . Combined heart failure device diagnostics identify patients at higher risk of subsequent heart failure hospitalizations: results from PARTNERS HF (Program to Access and Review Trending Information and Evaluate Correlation to Symptoms in Patients With Heart Failure) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010; 55: 1803–1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gardner RS, Singh JP, Stancak B, Nair DG, Cao M, Schulze C, Thakur PH, An Q, Wehrenberg S, Hammill EF, Zhang Y. HeartLogic multisensor algorithm identifies patients during periods of significantly increased risk of heart failure events: results from the MultiSENSE study. Circulation: Heart Fail. 2018; 11: e004669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mallick A, Januzzi JL Jr. Biomarkers in acute heart failure. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2015; 68: 514–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Choudhary R, Di Somma S, Maisel AS. Biomarkers for Diagnosis and prognosis of acute heart failure. Curr Emergency Hosp Med Rep. 2013; 1: 133–140. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mukoyama M, Nakao K, Hosoda K, Suga S, Saito Y, Ogawa Y, Shirakami G, Jougasaki M, Obata K, Yasue H. Brain natriuretic peptide as a novel cardiac hormone in humans ‐ evidence for an exquisite dual natriuretic peptide system, atrial‐natriuretic‐peptide and brain natriuretic peptide. J Clin Invest. 1991; 87: 1402–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Levin ER, Gardner DG, Samson WK. Natriuretic peptides. N Engl J Med. 1998; 339: 321–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Maisel AS, McCord J, Nowak RM, Hollander JE, Wu AHB, Duc P, Omland T, Storrow AB, Krishnaswamy P, Abraham WT, Clopton P. Bedside B‐type natriuretic peptide in the emergency diagnosis of heart failure with reduced or preserved ejection fraction ‐ Results from the breathing not properly multinational study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003; 41: 2010–2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Januzzi JL Jr, Camargo CA, Anwaruddin S, Baggish AL, Chen AA, Krauser DG, Tung R, Cameron R, Nagurney JT, Chae CU, Lloyd‐Jones DM. The N‐terminal Pro‐BNP investigation of dyspnea in the emergency department (PRIDE) study. Am J Cardiol. 2005; 95: 948–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Menosi Gualandro D, Twerenbold R, Boeddinghaus J, Nestelberger T, Puelacher C, Müller C. Biomarkers in cardiovascular medicine: towards precision medicine. Swiss Med Weekly. 2019; 149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Januzzi JL, van Kimmenade R, Lainchbury J, Bayes‐Genis A, Ordonez‐Llanos J, Santalo‐Bel M, Pinto YM, Richards M. NT‐proBNP testing for diagnosis and short‐term prognosis in acute destabilized heart failure: an international pooled analysis of 1256 patients: the International Collaborative of NT‐proBNP Study. Eur Heart J. 2006; 27: 330–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. van Kimmenade RR, Pinto YM, Januzzi JL Jr. Importance and interpretation of intermediate (gray zone) amino‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide concentrations. Am J Cardiol. 2008; 101: 39–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tate S, Griem A, Durbin‐Johnson B, Watt C, Schaefer S. Marked elevation of B‐type natriuretic peptide in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. J Biomed Res. 2014; 28: 255–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tanase DM, Radu S, Al Shurbaji S, Baroi GL, Florida Costea C, Turliuc MD, Ouatu A, Floria M. Natriuretic peptides in heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: from molecular evidences to clinical implications. Int J Mol Sci. 2019; 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Aspromonte N, Cappannoli L, Scicchitano P, Massari F, Pantano I, Massetti M, Crea F, Valle R. Stay home! stay safe! first post‐discharge cardiologic evaluation of low‐risk–low‐BNP heart failure patients in COVID‐19 era. J Clin Med. 2021; 10: 2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Latini R, Masson S, Anand IS, Missov E, Carlson M, Vago T, Angelici L, Barlera S, Parrinello G, Maggioni AP, Tognoni G. Prognostic value of very low plasma concentrations of troponin T in patients with stable chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2007; 116: 1242–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wu Y‐W, Ho SK, Tseng W‐K, Yeh H‐I, Leu H‐B, Yin W‐H, Lin TH, Chang KC, Wang JH, Wu CC, Chen JW. Potential impacts of high‐sensitivity creatine kinase‐MB on long‐term clinical outcomes in patients with stable coronary heart disease. Sci Rep. 2020; 10: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Drazner MH, Rame JE, Marino EK, Gottdiener JS, Kitzman DW, Gardin JM, Manolio TA, Dries DL, Siscovick DS. Increased left ventricular mass is a risk factor for the development of a depressed left ventricular ejection fraction within five years: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004; 43: 2207–2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shemisa K, Bhatt A, Cheeran D, Neeland IJ. Novel biomarkers of subclinical cardiac dysfunction in the general population. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2017; 14: 301–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Farmakis D, Mueller C, Apple FS. High‐sensitivity cardiac troponin assays for cardiovascular risk stratification in the general population. Eur Heart J. 2020; 41: 4050–4056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Berge K, Lyngbakken MN, Myhre PL, Brynildsen J, Røysland R, Strand H, Christensen G, Høiseth AD, Omland T, Røsjø H. High‐sensitivity cardiac troponin T and N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide in acute heart failure: Data from the ACE 2 study. Clin Biochem. 2021; 88: 30–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gomes AV, Potter JD, Szczesna‐Cordary D. The role of troponins in muscle contraction. IUBMB Life. 2002; 54: 323–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Daubert MA, Jeremias A. The utility of troponin measurement to detect myocardial infarction: review of the current findings. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2010; 6: 691–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ivandic BT, Spanuth E, Giannitsis E. Performance of the AQT90 Flex cTnI point‐of‐care assay for the rapid diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in the emergency room. Clin Lab. 2014; 60: 903–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Amundson BE, Apple FS. Cardiac troponin assays: a review of quantitative point‐of‐care devices and their efficacy in the diagnosis of myocardial infarction. Clin Chem Lab Med (CCLM). 2015; 53: 665–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ammirati E, Dobrev D. Conventional Troponin‐I versus high‐sensitivity troponin‐T: Performance and incremental prognostic value in non‐ST‐elevation acute myocardial infarction patients with negative CK‐MB based on a real‐world multicenter cohort. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasculature. 2018; 20: 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Welsh P, Preiss D, Shah AS, McAllister D, Briggs A, Boachie C, McConnachie A, Hayward C, Padmanabhan S, Welsh C, Woodward M. Comparison between high‐sensitivity cardiac troponin T and cardiac troponin I in a large general population cohort. Clin Chem. 2018; 64: 1607–1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Clerico A, Padoan A, Zaninotto M, Passino C, Plebani M. Clinical relevance of biological variation of cardiac troponins. Clin Chem Lab Med (CCLM) 2020; 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jaffe AS, Vasile VC, Milone M, Saenger AK, Olson KN, Apple FS. Diseased skeletal muscle: a noncardiac source of increased circulating concentrations of cardiac troponin T. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 58: 1819–1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Korff S, Katus HA, Giannitsis E. Differential diagnosis of elevated troponins. Heart. 2006; 92: 987–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Peacock WF IV, De Marco T, Fonarow GC, Diercks D, Wynne J, Apple FS, Wu AH. Cardiac troponin and outcome in acute heart failure. N Eng J Med. 2008; 358: 2117–2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Arenja N, Reichlin T, Drexler B, Oshima S, Denhaerynck K, Haaf P, Potocki M, Breidthardt T, Noveanu M, Stelzig C, Heinisch C. Sensitive cardiac troponin in the diagnosis and risk stratification of acute heart failure. J Intern Med. 2012; 271: 598–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Aimo A, Januzzi JL Jr, Mueller C, Miro O, Pascual Figal DA, Jacob J, Herrero‐Puente P, Llorens P, Wussler D, Kozhuharov N, Sabti Z. Admission high‐sensitivity troponin T and NT‐proBNP for outcome prediction in acute heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2019; 293: 137–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pourafkari L, Tajlil A, Nader ND. Biomarkers in diagnosing and treatment of acute heart failure. Biomark Med. 2019; 13: 1235–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tanindi A, Cemri M. Troponin elevation in conditions other than acute coronary syndromes. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2011; 7: 597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Alcalai R, Planer D, Culhaoglu A, Osman A, Pollak A, Lotan C. Acute coronary syndrome vs nonspecific troponin elevation: clinical predictors and survival analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2007; 167: 276–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Apple FS, Sandoval Y, Jaffe AS, Ordonez‐Llanos J. Cardiac troponin assays: guide to understanding analytical characteristics and their impact on clinical care. Clin Chem. 2017; 63: 73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Macchiusi A, Marino G, Vitillo M, Colivicchi F. Marked increase in high‐sensitivity troponin I without evidence of acute coronary syndrome. Giornale Italiano di Cardiologia 2006 2021; 22: 149–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sanada S, Hakuno D, Higgins LJ, Schreiter ER, McKenzie AN, Lee RT. IL‐33 and ST2 comprise a critical biomechanically induced and cardioprotective signaling system. J Clin Invest. 2007; 117: 1538–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Demyanets S, Kaun C, Pentz R, Krychtiuk KA, Rauscher S, Pfaffenberger S, Zuckermann A, Aliabadi A, Gröger M, Maurer G, Huber K. Components of the interleukin‐33/ST2 system are differentially expressed and regulated in human cardiac cells and in cells of the cardiac vasculature. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013; 60: 16–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chan BCL, Lam CWK, Tam LS, Wong CK. IL33: Roles in Allergic Inflammation and Therapeutic Perspectives. Front Immunol. 2019; 10: 364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Larsen KM, Minaya MK, Vaish V, Pena MMO. The Role of IL‐33/ST2 Pathway in Tumorigenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2018; 19: 2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Aleksova A, Paldino A, Beltrami AP, Padoan L, Iacoviello M, Sinagra G, Emdin M, Maisel AS. Cardiac biomarkers in the emergency department: the role of soluble ST2 (sST2) in acute heart failure and acute coronary syndrome‐there is meat on the bone. J Clin Med. 2019; 8: 270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hirotani S, Otsu K, Nishida K, Higuchi Y, Morita T, Nakayama H, Yamaguchi O, Mano T, Matsumura Y, Ueno H, Tada M. Involvement of nuclear factor‐?B and apoptosis signal‐regulating kinase 1 in G‐protein–coupled receptor agonist–induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Circulation. 2002; 105: 509–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Brint EK, Xu D, Liu H, Dunne A, McKenzie AN, O'Neill LA, Liew FY. ST2 is an inhibitor of interleukin 1 receptor and Toll‐like receptor 4 signaling and maintains endotoxin tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2004; 5: 373–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Weinberg EO, Shimpo M, De Keulenaer GW, MacGillivray C, Tominaga S, Solomon SD, Rouleau JL, Lee RT. Expression and regulation of ST2, an interleukin‐1 receptor family member, in cardiomyocytes and myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2002; 106: 2961–2966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Weinberg EO, Shimpo M, Hurwitz S, Tominaga S, Rouleau JL, Lee RT. Identification of serum soluble ST2 receptor as a novel heart failure biomarker. Circulation. 2003; 107: 721–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Coglianese EE, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Ho JE, Ghorbani A, McCabe EL, Cheng S, Fradley MG, Kretschman D, Gao W, O'Connor G. Distribution and clinical correlates of the interleukin receptor family member soluble ST2 in the Framingham Heart Study. Clin Chem. 2012; 58: 1673–1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bartunek J, Delrue L, Van Durme F, Muller O, Casselman F, De Wiest B, Croes R, Verstreken S, Goethals M, de Raedt H, Sarma J. Nonmyocardial production of ST2 protein in human hypertrophy and failure is related to diastolic load. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008; 52: 2166–2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ghali R, Altara R, Louch WE, Cataliotti A, Mallat Z, Kaplan A, Zouein FA, Booz GW. IL‐33 (interleukin 33)/sST2 axis in hypertension and heart failure. Hypertension. 2018; 72: 818–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Miftode R‐S, Petriș AO, Onofrei Aursulesei V, Cianga C, Costache I‐I, Mitu O, Miftode IL, Șerban IL. The novel perspectives opened by st2 in the pandemic: A review of its role in the diagnosis and prognosis of patients with heart failure and COVID‐19. Diagnostics. 2021; 11: 175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tang WW, Wu Y, Grodin JL, Hsu AP, Hernandez AF, Butler J, Metra M, Voors AA, Felker GM, Troughton RW, Mills RM. Prognostic value of baseline and changes in circulating soluble ST2 levels and the effects of nesiritide in acute decompensated heart failure. JACC. Heart Fail. 2016; 4: 68–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. McCarthy CP, Januzzi JL. Soluble ST2 in heart failure. Heart Fail Clin. 2018; 14: 41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Carlomagno G, Messalli G, Melillo RM, Stanziola AA, Visciano C, Mercurio V, Imbriaco M, Ghio S, Sofia M, Bonaduce D, Fazio S. Serum soluble ST2 and interleukin‐33 levels in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Int J Cardiol. 2013; 168: 1545–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ojji DB, Opie LH, Lecour S, Lacerda L, Adeyemi OM, Sliwa K. The effect of left ventricular remodelling on soluble ST2 in a cohort of hypertensive subjects. J Hum Hypertens. 2014; 28: 432–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Huttin O, Kobayashi M, Ferreira JP, Coiro S, Bozec E, Selton‐Suty C, Filipetti L, Lamiral Z, Rossignol P, Zannad F, Girerd N. Circulating multimarker approach to identify patients with preclinical left ventricular remodelling and/or diastolic dysfunction. ESC Heart Fail. 2021; 8: 1700–1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ojji DB, Opie LH, Lecour S, Lacerda L, Adeyemi O, Sliwa K. Relationship between left ventricular geometry and soluble ST 2 in a cohort of hypertensive patients. J Clin Hyper. 2013; 15: 899–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Piper S, deCourcey J, Sherwood R, Amin‐Youssef G, McDonagh T. Biologic variability of soluble ST2 in patients with stable chronic heart failure and implications for monitoring. Am J Cardiol. 2016; 118: 95–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Manzano‐Fernández S, Mueller T, Pascual‐Figal D, Truong QA, Januzzi JL. Usefulness of soluble concentrations of interleukin family member ST2 as predictor of mortality in patients with acutely decompensated heart failure relative to left ventricular ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol. 2011; 107: 259–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Aimo A, Vergaro G, Ripoli A, Bayes‐Genis A, Pascual Figal DA, de Boer RA, Lassus J, Mebazaa A, Gayat E, Breidthardt T, Sabti Z. Meta‐Analysis of Soluble Suppression of Tumorigenicity‐2 and Prognosis in Acute Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2017; 5: 287–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Boulogne M, Sadoune M, Launay J, Baudet M, Cohen‐Solal A, Logeart D. Inflammation versus mechanical stretch biomarkers over time in acutely decompensated heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Int J Cardiol. 2017; 226: 53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Januzzi JL Jr, Peacock WF, Maisel AS, Chae CU, Jesse RL, Baggish AL, O’Donoghue M, Sakhuja R, Chen AA, van Kimmenade RR, Lewandrowski KB. Measurement of the interleukin family member ST2 in patients with acute dyspnea: results from the PRIDE (Pro‐Brain Natriuretic Peptide Investigation of Dyspnea in the Emergency Department) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007; 50: 607–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Januzzi JL, Mebazaa A, Di Somma S. ST2 and prognosis in acutely decompensated heart failure: the International ST2 Consensus Panel. Am J Cardiol. 2015; 115: 26B–31B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Demissei BG, Valente MA, Cleland JG, O'Connor CM, Metra M, Ponikowski P, Teerlink JR, Cotter G, Davison B, Givertz MM, Bloomfield DM. Optimizing clinical use of biomarkers in high‐risk acute heart failure patients. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016; 18: 269–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wu AH, Wians F, Jaffe A. Biological variation of galectin‐3 and soluble ST2 for chronic heart failure: implication on interpretation of test results. Am Heart J. 2013; 165: 995–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Boisot S, Beede J, Isakson S, Chiu A, Clopton P, Januzzi J, Maisel AS, Fitzgerald RL. Serial sampling of ST2 predicts 90‐day mortality following destabilized heart failure. J Card Fail. 2008; 14: 732–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Breidthardt T, Balmelli C, Twerenbold R, Mosimann T, Espinola J, Haaf P, Thalmann G, Moehring B, Mueller M, Meller B, Reichlin T. Heart failure therapy‐induced early ST2 changes may offer long‐term therapy guidance. J Card Fail. 2013; 19: 821–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. van Vark LC, Lesman‐Leegte I, Baart SJ, Postmus D, Pinto YM, Orsel JG, Westenbrink BD, Brunner‐la Rocca HP, van Miltenburg AJ, Boersma E, Hillege HL. Prognostic value of serial ST2 measurements in patients with acute heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; 70: 2378–2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Dong R, Zhang M, Hu Q, Zheng S, Soh A, Zheng Y, Yuan H. Galectin‐3 as a novel biomarker for disease diagnosis and a target for therapy. Int J Mol Med. 2018; 41: 599–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Suthahar N, Meijers WC, Sillje HHW, Ho JE, Liu FT, de Boer RA. Galectin‐3 activation and inhibition in heart failure and cardiovascular disease: an update. Theranostics. 2018; 8: 593–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Martinez‐Martinez E, Brugnolaro C, Ibarrola J, Ravassa S, Buonafine M, Lopez B, Fernández‐Celis A, Querejeta R, Santamaria E, Fernández‐Irigoyen J, Rábago G. CT‐1 (Cardiotrophin‐1)‐Gal‐3 (Galectin‐3) axis in cardiac fibrosis and inflammation. Hypertension. 2019; 73: 602–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Blanda V, Bracale UM, Di Taranto MD, Fortunato G. Galectin‐3 in Cardiovascular Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2020; 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. de Boer RA, Voors AA, Muntendam P, van Gilst WH, van Veldhuisen DJ. Galectin‐3: a novel mediator of heart failure development and progression. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009; 11: 811–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Li LC, Li J, Gao J. Functions of galectin‐3 and its role in fibrotic diseases. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2014; 351: 336–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Li M, Yuan Y, Guo K, Lao Y, Huang X, Feng L. Value of Galectin‐3 in acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 2020; 20: 333–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. van Kimmenade RR, Januzzi JL Jr, Ellinor PT, Sharma UC, Bakker JA, Low AF, Martinez A, Crijns HJ, MacRae CA, Menheere PP, Pinto YM. Utility of amino‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide, galectin‐3, and apelin for the evaluation of patients with acute heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 48: 1217–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. de Boer RA, van Veldhuisen DJ, deFilippi C, Muntendam P, Adourian AS, Guo Y, Januzzi JL. Plasma galectin‐3 is associated with near‐term rehospitalization in heart failure: a meta‐analysis. J Cardiac Fail 2011; 17: S93. [Google Scholar]

- 83. van der Velde AR, Gullestad L, Ueland T, Aukrust P, Guo Y, Adourian A, Muntendam P, van Veldhuisen DJ, de Boer RA. Prognostic value of changes in galectin‐3 levels over time in patients with heart failure: data from CORONA and COACH. Circ Heart Fail. 2013; 6: 219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Dong R, Zhang M, Hu Q, Zheng S, Soh A, Zheng Y, Yuan H. Galectin‐3 as a novel biomarker for disease diagnosis and a target for therapy (Review). Int J Mol Med. 2018; 41: 599–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Sciacchitano S, Lavra L, Morgante A, Ulivieri A, Magi F, De Francesco GP, Bellotti C, Salehi LB, Ricci A. Galectin‐3: One molecule for an alphabet of diseases, from A to Z. Int J Mol Sci. 2018; 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Wu AH, Smith A, Wieczorek S, Mather JF, Duncan B, White CM, McGill C, Katten D, Heller G. Biological variation for N‐terminal pro‐and B‐type natriuretic peptides and implications for therapeutic monitoring of patients with congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2003; 92: 628–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Wu AH, Lu QA, Todd J, Moecks J, Wians F. Short‐and long‐term biological variation in cardiac troponin I measured with a high‐sensitivity assay: implications for clinical practice. Clin Chem 2009; 55: 52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Dieplinger B, Januzzi JL Jr, Steinmair M, Gabriel C, Poelz W, Haltmayer M, Mueller T. Analytical and clinical evaluation of a novel high‐sensitivity assay for measurement of soluble ST2 in human plasma—The Presage™ ST2 assay. Clin Chim Acta. 2009; 409: 33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Frankenstein L, Wu AH, Hallermayer K, Wians FH Jr, Giannitsis E, Katus HA. Biological variation and reference change value of high‐sensitivity troponin T in healthy individuals during short and intermediate follow‐up periods. Clin Chem. 2011; 57: 1068–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Schindler EI, Szymanski JJ, Hock KG, Geltman EM, Scott MG. Short‐ and Long‐term Biologic Variability of Galectin‐3 and Other Cardiac Biomarkers in Patients with Stable Heart Failure and Healthy Adults. Clin Chem. 2016; 62: 360–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Demissei BG, Cotter G, Prescott MF, Felker GM, Filippatos G, Greenberg BH, Pang PS, Ponikowski P, Severin TM, Wang Y, Qian M. A multimarker multi‐time point‐based risk stratification strategy in acute heart failure: results from the RELAX‐AHF trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017; 19: 1001–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Castiglione V, Aimo A, Vergaro G, Saccaro L, Passino C, Emdin M. Biomarkers for the diagnosis and management of heart failure. Heart Fail Rev 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. George M, Jena A, Srivatsan V, Muthukumar R, Dhandapani VE. GDF 15‐A Novel Biomarker in the Offing for Heart Failure. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2016; 12: 37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Cotter G, Voors AA, Prescott MF, Felker GM, Filippatos G, Greenberg BH, Pang PS, Ponikowski P, Milo O, Hua TA, Qian M. Growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF‐15) in patients admitted for acute heart failure: results from the RELAX‐AHF study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015; 17: 1133–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Bettencourt P, Ferreira‐Coimbra J, Rodrigues P, Marques P, Moreira H, Pinto MJ, Guimarães JT, Lourenço P. Towards a multi‐marker prognostic strategy in acute heart failure: a role for GDF‐15. ESC Heart Fail. 2018; 5: 1017–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Peacock WF. Novel biomarkers in acute heart failure: MR‐pro‐adrenomedullin. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2014; 52: 1433–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Morbach C, Marx A, Kaspar M, Guder G, Brenner S, Feldmann C, Stoerk S, Vollert JO, Ertl G, Angermann CE, INH Study Group and the Competence Network Heart Failure . Prognostic potential of midregional pro‐adrenomedullin following decompensation for systolic heart failure: comparison with cardiac natriuretic peptides. Eur J Heart Fail 2017; 19: 1166–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Lassus J, Harjola VP, Sund R, Siirila‐Waris K, Melin J, Peuhkurinen K, Pulkki K, Nieminen MS. Prognostic value of cystatin C in acute heart failure in relation to other markers of renal function and NT‐proBNP. Eur Heart J. 2007; 28: 1841–1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Breidthardt T, Sabti Z, Ziller R, Rassouli F, Twerenbold R, Kozhuharov N, Gayat E, Shrestha S, Barata S, Badertscher P, Boeddinghaus J. Diagnostic and prognostic value of cystatin C in acute heart failure. Clin Biochem. 2017; 50: 1007–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Aghel A, Shrestha K, Mullens W, Borowski A, Tang WH. Serum neutrophil gelatinase‐associated lipocalin (NGAL) in predicting worsening renal function in acute decompensated heart failure. J Card Fail. 2010; 16: 49–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]