Abstract

Aim

To evaluate clinicians' perspectives on the impact of ‘lockdown’ during the COVID‐19 pandemic for children and young people with severe physical neurodisability and their families.

Method

Framework analysis of comments from families during a recent service review was used to code the themes discussed according to the World Health Organization International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) and interpreted into emergent themes to summarize the impact of lockdown (Stage 1). They were presented to a clinician focus group for discussion (consultants and physiotherapists working in a specialist motor disorders service, [Stage 2]).

Results

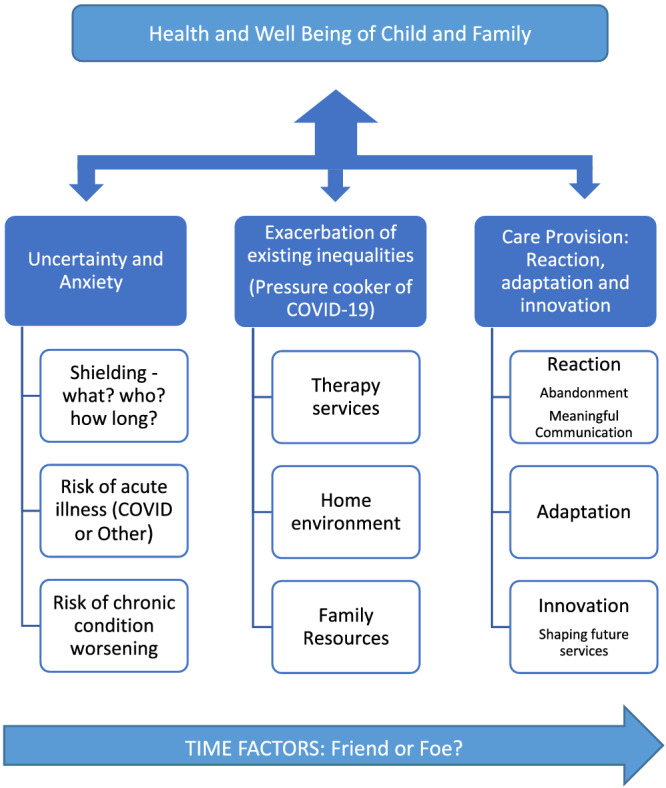

Three overarching themes ‘Uncertainty and Anxiety’, ‘Exacerbation of Existing Inequalities’ and ‘Care Provision: Reaction, Adaptation, and Innovation’ summed up the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on health and well‐being in children and young people with neurodisability and their families. All themes were influenced by time.

Interpretation

This study reflects clinician's perceptions of family experiences of the pandemic and lockdown. Significant impact is apparent in the entire U.K. population, but the complexity of care needs for children with physical neurodisability exacerbates this. Lobbying for government policy is vital to ensure that all children, and in particular those with significant health and social care needs, are protected and continue to access services. During the restoration and recovery phase of the pandemic, there is a need for service reconfiguration that utilizes what we have learned and is adaptive to individual family circumstances.

Keywords: cerebral palsy, child disability, COVID‐19, qualitative

Key messages.

The COVID‐19 pandemic itself, local service delivery and national response all resulted in significant anxiety for children and young people with physical disability and their families.

Meaningful communication with trusted, responsive professionals was essential to reduce anxiety for families, requiring holistic oversight from local paediatric services with tertiary support.

Both the pandemic and our response to it exacerbated existing inequalities in health needs and service provision, particularly for families of lower socio‐economic status. Lobbying for government policy is vital to ensure that all children, and in particular those with significant health and social care needs, are protected and continue to access services.

Only hindsight and long‐term epidemiological studies will be able to assess the full impact of the pandemic on health outcomes for the population of children with severe physical disability.

1. INTRODUCTION

The COVID‐19 pandemic has represented an unprecedented societal and healthcare emergency, rapidly emerging and spreading worldwide. Whilst national approaches to testing and contact tracing have differed greatly, a major component of the approach to limit spread was a period of ‘lockdown’ comprising restrictive social distancing and isolation. In the United Kingdom, the initial lockdown began for the whole population on 23 March 2020, with additional instructions for specific groups deemed to be clinically vulnerable to stay ‘shielded’ in their homes for a total of 12 weeks. Although considered essential to reduce rates of infection and mortality, lockdown measures are associated with adverse consequences on household finances, child and family psychological well‐being, general health and access to health and social care services (Fegert et al., 2020). Further, the pandemic has changed public perceptions of health and social care provision in the United Kingdom (Ipsos MORI, June 2020).

The rapid spread of infection, coupled with the acute and severe nature of the disease disproportionately affecting specific subpopulations (e.g. the elderly, those with some chronic medical conditions and ethnic minority groups [Price‐Haywood et al., 2020; Stokes et al., 2020]), led to unparalleled strain on healthcare resources including saturation of intensive care facilities and overwhelmed clinical staff with many redeployed from usual roles to directly assist in the care of COVID‐19 patients. As a consequence, to enable further prioritization of critical care services and reduce risk of cross‐infection, the majority of elective hospital admissions and procedures were cancelled or postponed across the United Kingdom. Most scheduled outpatient appointments (both in community and hospital settings) were either reorganized as virtual consultations or cancelled (Stevens & Pritchard, 2020).

These procedural challenges are particularly relevant for children and young people with chronic physical disability. For example, those with cerebral palsy (CP), who represent 0.3% of the population, disproportionately account for 1.6% of all hospital admissions and outpatient appointments (Carter et al., 2020). The increased healthcare interaction is further related to the functional level of the individual with CP, with the most dependent (Gross Motor Function Classification Scale [GMFCS] level V, Palisano et al., 1997) children being 10 times more likely to require hospital admission compared with those less severely involved (Carter et al., 2020).

Carers of children with CP have been shown to have both reduced quality of life and higher rates of physical and mental health difficulties than the wider population (Eunson, 2015; Ketelaar et al., 2008; Parkes et al., 2011; Raina et al., 2005). Specific challenges relating to family finances and accessing support from local services also negatively impact their psychological wellbeing (Davis et al., 2010). Clinicians are often the first point of contact for many of these issues that families face.

Following a service review related to the impact of COVID‐19 (Arichi et al., n.d.), clinicians gained significant insight into the impact of lockdown on the children and families they supported. Therefore, we aimed to explore clinicians' interpretations of the impact of the initial lockdown on children and young people with severe physical neurodisability (with a known history of recurrent respiratory tract difficulties) and their families.

2. METHODS

2.1. Research team and reflexivity

Author JG (PhD; a female research associate with extensive qualitative research experience) conducted the focus group. A relationship between JG and all other researchers was established prior to study through previous research collaboration. All other authors are consultants and physiotherapists with significant clinical and research experience in paediatric physical neurodisability. They work within the specialist paediatric neurodisability and movement disorder service at the Evelina London Children's Hospital (Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK). This is part of a tertiary Neuroscience team supporting children and adolescents across South East England (population over 11.8 million) and providing highly specialist input for children across the United Kingdom. Authors were conscious of their biases throughout all stages of the research, whilst acknowledging that this expertise allowed rich exploration of the data.

2.2. Study design

This study was informed by the Framework Method (Ritchie & Spencer, 1994), which is not aligned with a particular epistemological or philosophical approach and thus allows for systematic data analysis. Based on the Health Research Authority decision‐making tool (http://www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk/ethics/), ethical approval was not required. However, verbal parental consent was attained for the service evaluation (Stage 1), which was Trust approved. The participant selection, setting and data collection are outlined below.

2.3. Service evaluation to inform the current study

As part of a service evaluation, we used a self‐designed questionnaire to explore the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic and lockdown on children/young people with severe physical neurodisability and their families, across 5 of the 7 NHS England regions (see Supporting Information); 108 families with a child or young person up to 25 years of age known to the paediatric neurodisability and movement disorder services at the Evelina London Children's Hospital (Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK) were contacted via the telephone or video link over a 4‐week period in May 2020 (Weeks 6–10 into the U.K. lockdown period). Each child or young person had severe physical neurodisability and a known history of recurrent respiratory tract difficulties (e.g. long‐term ventilation, tracheostomy dependency, recurrent chest infections, upper airway structural abnormalities, bulbar dysfunction or a history of chronic lung disease). Most were on the NHS England vulnerable patient‐shielding list. The majority (79.6%) were children with an underlying diagnosis of CP, GMFCS levels IV and V, with a smaller proportion known to have severe physical disabilities due to other diagnoses (e.g. Lesch Nyhan Syndrome, CLN3 [Batten's] disease). The questionnaire was aimed to guide future regional clinical pathway management, particularly if there was a subsequent lockdown period and also to understand the impact of the lockdown period on the child and family's mental, functional and physical well‐being, care, socio‐economic and social factors. Families were interviewed as part of a routine virtual clinic consultation over 30–60 min. A significant proportion of families reported missing hospital appointments and routine therapy, with subsequent worsening of symptoms and function. Additional wider effects on the family were also identified with many describing worsening stress and anxiety during the pandemic.

2.4. Stage 1: Qualitative data analysis to inform the current study

During the service evaluation, clinicians recorded over 500 free text comments about the impact of COVID‐19 on these families, transcribed by the clinician who completed the questionnaire as additional text whilst completing the questionnaire with the patient and family. These comments were then anonymized and saved into a separate database.

We used a deductive–inductive approach: Author JC completed initial coding, which was sense checked by the rest of the author team. Any discrepancies were resolved through robust discussion with the authors. Certain themes and codes were preselected based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF; World Health Organization, 2007), a recognized framework for examining the impact of a therapeutic intervention on individual health‐related functioning. It comprises five components: body structures and functions (anatomical parts of the body and physiological functions); participation and activities (involvement and execution of tasks); environmental; and personal factors (external and internal influences on functioning, such as physical environment or coping strategies). There were several comments that were relevant to more than one ICF domain. These were highlighted and themes from the overlaps discussed. All comments were summarized and presented for discussion in a clinician focus group.

2.5. Stage 2: Clinician focus group

The focus group was conducted via video call and lasted 2 h. It was facilitated by JG as an independent non‐clinical observer and comprised a purposive sample: four consultant paediatricians in neurodisability, one consultant paediatric neurologist and three clinical specialist paediatric physiotherapists. All have a special interest in complex physical neurodisability and motor disorders. The anonymized findings of the service review (Stage 1) were presented with comments according to the ICF framework, highlighting areas of overlap between ICF domains. Participants then discussed if this reflected their clinical interpretation of the families' experiences, any areas of diversity or divergence from expectations and what could be learned to improve future clinical services. The discussion was recorded, transcribed, for analysis.

2.6. Analysis and findings

The clinician focus group data were analysed in June 2020. JC, as an expert in paediatric neurodisability coded the focus group discussion, informed by the Framework Method (Ritchie & Spencer, 1994). Table 1 outlines the stages of Framework Analysis, which includes familiarization with the data, coding the focus group, developing a theoretical framework, indexing the transcript and charting by summarizing each category with illustrative quotations. This was done using similar preselected themes and codes based on the ICF (World Health Organization, 2007). A second independent coding was done by JG. Following this, rich discussion with the author team leads to development and finalization of a working analytical framework with themes that described the clinicians' interpretations more richly than the ICF. These themes are described in Section 3 below. Coding was conducted through Microsoft Word to provide a clear audit trail. Participants reviewed and agreed with the findings. Quotations are provided as evidence to illustrate the themes.

TABLE 1.

Stages of framework method analysis

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Verbatim transcription. |

| 2 | Familiarization of data (e.g. reading and rereading transcripts and re‐listening to the audio recording). |

| 3 | Coding as per the ICF‐CY. Although deductive coding was used, some open coding took place at this stage to ensure important aspects of the data were not missed. |

| 4 | Developing a working analytical framework beyond the ICF codes through discussion and definition of labels. |

| 5 | Applying the analytical framework by indexing the transcript using existing codes. |

| 6 | Charting data into the framework matrix. That is, data were summarized by category with illustrative quotations. |

| 7 | Interpreting the data through discussion, reflection and writing up. |

Abbreviation: ICF, International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health.

3. RESULTS

Three overarching themes emerged from the clinician focus group describing the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on the health and well‐being of children and young people with severe physical disability and their families:

‘Uncertainty and Anxiety’,

‘Exacerbation of Existing Inequalities’ and

‘Care Provision: Reaction, Adaptation and Innovation’.

These are summarized in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Summary of themes

All of these themes were influenced by time over the lockdown period, perhaps reflecting the unprecedented and rapidly changing socio‐political challenges associated with the pandemic response. For some, the lockdown provided a unique opportunity to spend prolonged time with each other, in some cases, reducing concern and improving health and development. For others, the uncertain duration of lockdown, increased physical and psychological demands on the parent carers and siblings, limited respite provision and loss of a wider support network had a significant negative impact on health and well‐being. Clinicians also reported a change in family perspective over the duration of the lockdown: encountering initial acceptance with fight response and coping strategies; followed by boredom, frustration, increased anxiety and uncertainty especially regarding duration and exit from lockdown. Several of the families were considered by the clinicians to be at significant risk of ‘burnout’ requiring emergency contact with local clinical and social support networks.

3.1. Uncertainty and anxiety

The COVID‐19 pandemic caused anxiety for children, young people and their families (as well as their clinical teams), mostly related to uncertainties about the direct risks of COVID‐19, and the wider impacts of the pandemic, such as how to manage individual clinical concerns and service provision.

The main areas were confusion around shielding, risk of acute illness, risk of deterioration of chronic condition and what would happen at the end of lockdown when parents went back to work or siblings to school. Conversely, clinicians found it difficult to provide the appropriate support for families when their own concerns were exacerbated by uncertainty of service provision, with redeployment of staff and enforced change in clinical pathways.

3.1.1. Shielding

Confused and disparate guidance about shielding caused confusion and hardship. There was confusion regarding categories of vulnerability, who should be shielding and when shielding should start and finish. This uncertainty of message extended into their healthcare providers, and as a result, some children who did not need to shield were advised to, and others vice versa. Many families made their own decision about shielding, despite formal advice, often isolating well before lockdown. The aforementioned difficulties were further exacerbated by significant delays in many families receiving official shielding letters. In our population, most letters with shielding recommendations arrived 6–7 weeks after lockdown, which meant that a significant proportion of families may not have been shielding as advised and even if there were, did not have access to the appropriate support (e.g. priority supermarket deliveries), which led to heightened anxiety. The message that shielding was advisory rather than mandatory was insufficiently heard, leading to feelings of guilt and blame, particularly in cases where families were physically or financially unable to shield.

Families felt isolated, and despite shielding, parents had to take their child to the supermarket and pharmacy, as they had no letter to provide priority support, they had not heard anything (Physiotherapist).

For families who did shield, their mental health and well‐being were often affected by the uncertainty around how long the pandemic would last and how long shielding would be recommended for. Many parents reported that they felt isolated, anxious and worried about their finances. Several had suffered grief over family bereavement without usual family support networks (e.g. death of a first degree relative.)

A lot of families said to me that they were worried about what's going to happen at the end of lockdown. What's going to happen when they have to go back to work (Consultant Paediatrician in Neurodisability).

The increased care burden meant parents often felt guilty about balancing the needs of the disabled child and their siblings. They also carried a sense of responsibility for doing the right thing.

3.1.2. Risk of acute illness (COVID‐19 related or other)

Parents were concerned about accessing healthcare if the child became acutely unwell either through COVID‐19 related illness or other comorbidity. In terms of COVID‐19 itself, parents reported genuine anxiety about how it may directly affect their child if they were to be infected and their possible need for, or even whether they would be allowed, intensive care. They were especially troubled about their child's level of vulnerability to COVID‐19 and how the virus would affect children with disability. This anxiety extended beyond the child's health, encompassing wider issues around their ongoing care. A common concern for parents was:

Who would care for their child if they were to become ill? They have that concern anyway, but COVID‐19 has exacerbated it (Physiotherapist).

Nearly all of the families interviewed chose to take their child out of school before initial lockdown, having weighed up the risks and benefits of home schooling versus risk of infection. However, as that lockdown eased, some families still had no choice: as many schools could not support return to school for children with complex needs.

Risk assessments in schools said children could not go in, even in families who did not need to shield (Consultant Paediatrician in Neurodisability).

3.1.3. Risk of chronic condition worsening

Many parents were anxious about missed healthcare appointments and the implications for their child's ongoing health, from routine outpatient consultations to delayed botulinum toxin injections for muscle tone and secretions, to delayed orthopaedic and other surgery. These challenges continue through the restoration phase for services. Concerns voiced by clinicians on a sense that this would lead to a cumulative backlog of interventions have proven correct with longer‐term impact than just an initial reduction in face‐to‐face care.

We are all concerned regarding the cumulative effect of multiple missed appointments and reduced provision for a group of highly complex children with physical acute and chronic conditions and additional neurodevelopmental needs (Consultant paediatrician in Neurodisability).

Deterioration in comorbidities was often reported by parents. This particularly regarded difficulties relating to pain, tone, epilepsy, gastrointestinal (GI) function (reflux, constipation and vomiting) and nutrition. Unavailability of medicine or specific formulation impacted several clinical areas, notably foregut dysmotility with lack of ranitidine and liquid omeprazole, with other preparations blocking gastrostomy tubes. Respiratory concerns, particularly sleep apnoea, and secretion management were highlighted. The majority of the pain was musculoskeletal in origin and related to poor tone control. Issues of dental pain and GI discomfort were also frequently raised.

Some families reported clinical benefits of lockdown, particularly reduced respiratory illnesses (limited exposure to other pathogens), as well as sometimes improvements in feeding, constipation or sleep:

‘… feeding better at home because they are with their parent‐carers, especially in families where there are concerns regarding feeding at school or with other carers’, and with sleep some were reported to be more settled at night. ‘I saw sleep in line with the anxiety level, of the child and family, lots also struggled with nutrition and constipation, although this improved in some who had got that balance sorted out’ (Consultant Paediatrician in Neurodisability).

Flexibility in routine also resulted in some positive developmental changes. For example, one young person started stepping and walking with the constant focus of both parents.

3.2. Exacerbation of existing inequalities (pressure cooker of COVID‐19)

The COVID‐19 pandemic highlighted and heightened inequitable baseline service provision. Various factors such as the child's age and socio‐economic status impacted on their access to services, their health and well‐being.

3.2.1. Therapy services

Services tend to focus on and emphasize the importance of early intervention following diagnosis; therefore, when teams became unavailable in lockdown, parents of younger children were worried about missed ‘golden’ developmental opportunities due to lack of targeted therapeutic support.

My patients are quite young (less than 5 years), all the parents are very concerned about the lack of face to face appointments and hands on therapies, it's probably my fault as I have always discussed that this is a key time in their child's development, and that they must engage with professionals and how important this is for their ongoing care (Consultant Paediatrician in Neurodisability).

However, many parents of teenagers and young adults reported therapy input was no different during lockdown as they did not have access to therapy normally. This is a long‐standing issue of resource limitation, particularly for older children, and this inequity of access to existing services is a source of significant concern for families, advocacy groups and clinicians.

Many families reported functional deterioration due to changes in tone, mobility and posture during lockdown. Partly this was due to lack of home equipment and adaptations (e.g., reduced mobility due to difficulties with manual handling). Other parents felt empowered to do therapy during lockdown but were unable to access wheelchair services, orthotics, equipment and adaptations (in particular planned reviews/repairs), which adversely affected the child's participation. Supporting communication was especially difficult if families did not have help with using communication equipment in the home, impacting communication with household members, peers and their wider social circle.

Many families were not aware that the services they needed to access were still available during lockdown. Some had assumed they could not get support during the pandemic, they did not want to feel a burden to the NHS and therefore did not contact teams:

There were families that were having trouble … for example one of them the spinal brace was a big problem … the child was lying on the floor and could not tolerate their wheelchair … I asked ‘well have you contacted the spinal team?’ No! ‘Do you know how to contact the spinal team?’ Yes! … So there was a reluctance to contact because they thought the answer would be no, rather than actually contacting and getting the answer no (Consultant Paediatrician in Neurodisability).

Access to therapy services was reduced. Within the multidisciplinary teams, around half of physiotherapists had made contact but only a quarter of other therapists. Some families had access to private therapy. Sessions delivered via video calls were deemed to be most helpful.

Private therapists can do zoom calls, and this was better for the families, than NHS therapists, just making phone calls and … just checking in (Paediatric Neurologist).

Parents were also worried that missed appointments and surgeries would mean that they would now be placed on the bottom of the priority list. This was particularly distressing, as many parents felt as though they had struggled to get to that point on the pathway.

A parent told me, that they think now, that the surgeon may be relieved that they can delay the operation … and they are concerned that we will have to start all of the investigations, all over again (Paediatric Neurologist).

3.2.2. Home environment

Equipment access in the home environment was a source of inequity for families' health and well‐being. Due to uncertainty about cross‐infection, some equipment was not transferred to patient homes from school, and even when access was facilitated, parents' knowledge and experience to use the equipment was variable. Physical space for equipment caused concern for some. Conversely, others reported some positive effects such as finding more time than normal for therapy and equipment use without the demands of the classroom, and with both parents at home, there was more time to engage in these activities.

Many parents who previously stayed at home prior to lockdown found no impact on their socio‐economic status or caring duties, whereas others experienced significant change. As stated, some were positive about the additional time they were able to spend with their children, but some were stressed, partly due to the uncertainty of how long the pandemic would last and their future financial prospects. All clinicians emphasized the importance of acknowledging caring for a disabled child as a full‐time occupation.

Home technology for entertainment and social contact had positive influence on well‐being. This was particularly helpful when family members, especially grandparents, engaged with children (e.g. reading a story over video call) in order to provide some respite.

3.3. Care provision: Reaction of health services

3.3.1. Abandonment

Many families reported a lack of communication from health providers during initial lockdown. There was a clear sense that they felt abandoned. Many had received no contact from local service providers; or contact was delayed until late in the lockdown period. This increased perceived inequality: Parent carers who knew their way around care‐service pathways in advocating for their child managed to do so during the lockdown. Those who were uncertain of the process or did not actively seek contact with health services felt the impact further.

Many families reported that they felt it was their duty to muddle on and did not want to bother professionals, who they assumed were under significant pressure or re‐deployed. Other families neither understood about professional re‐deployment, nor the wider service pressures within the NHS England, so felt let down by professionals that they trusted.

There was a lot of dissatisfaction with contact, some families said only contact was they got a letter saying we are sorry we are being redeployed we will not be in contact, some did not know that their team had been re‐deployed (Physiotherapist).

Families also reported that specialist services had been much more responsive that local ones, perhaps because more of the community teams were re‐deployed into other roles, compared with tertiary ones.

Families reported a tsunami of contact from tertiary specialists, but limited contact from local clinicians, for holistic support, which is what they wanted (Consultant Paediatrician in Neurodisability).

The delay, or lack of receipt of shielding advice, as discussed in the uncertainty and anxiety section above, was seen, by clinicians and families alike, as a significant health service process failing, and had a negative effect on family well‐being. Some clinicians felt guilty that they had not (or could not) do more to support these families, particularly when they learned that some were literally at starvation point: Prioritization for deliveries from many supermarkets was impossible for many without formal shielding letters.

3.3.2. Meaningful communication

The lack of communication was not universal. Many virtual appointments had been offered, but families found the value of these variable. Whilst some parents reported that these were very helpful, reducing the need to travel long distances for simple follow up (such as medication reviews), others felt that they were insufficient to meet their needs, especially if it was a first contact. In particular, some families reported that a phone call (rather than video contact) was of little practical help to them:

Families thought virtual contact was not meaningful. Unless they are seeing someone face‐to‐face they do not really seem to think it is very valuable, and they seemed ungrateful (Consultant Paediatrician in Neurodisability).

The perception of a responsive service known to the families was important with regards to trust:

The family felt they need people to be responsive … they do not mind a bit of contact … but then if they … have not had any follow up from that, or do not know how to get back in touch they find that quite difficult (Consultant Paediatrician in Neurodisability).

These challenges were similar for the professionals. Although most of the clinicians in this study knew the patients, sometimes they were doing consultations on behalf of named colleagues in the wider team. Problems were particularly apparent during phone calls: All of the clinicians reported they felt uncomfortable calling parents they had not met previously.

It was scary for some of them and then they were harsh, in some cases I felt this family does not want to talk to me (Consultant Paediatrician in Neurodisability).

However, clinicians noted that it was possible to win families over and have valuable conversations via telephone, even if the family was not known to them. Also, meaningful communication meant clinicians had to try to avoid assumptions. For example, some parents seemed completely in control, but when questioned directly, it was revealed that the family needed support:

It's like a swan … they are managing on the surface and then underneath it all their feet are paddling away like mad … a family that I thought were financially secure said they were worried about finance. Unless you ask those questions, assumptions that all is okay are not always correct (Consultant Paediatrician in Neurodisability).

3.3.3. Adaptation

Lockdown led to challenge in health services across all levels. Sourcing medication was often a source of worry, particularly enforced changes in prescriptions.

Families had cheaper formulations prescribed by General Practitioners (GPs) … normal stocks ran out and then the GPs were getting very cross about having to give named rather than generic forms. Liquid omeprazole stopped and Ranitidine wasn't available (Consultant Paediatrician in Neurodisability).

3.3.4. Respite and homecare support reduced

Some families reported that during initial lockdown without adequate respite, either from regular carers, outside activities or school, they were concerned about their own mental health and coping strategies. Many parents had to weigh up the risk of COVID‐19 against their child's care needs by allowing staff into the home. There was often a lack of adequate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) provision by agencies for carers, and many families provided their own. The uncertainty about the duration of lockdown was an important factor, creating concern about how long families could sustain additional caring pressures. Many families relied on extended family to provide respite, which became impossible with lockdown, shielding and self‐isolation. In several cases, one parent moved out of the home shielding bubble to continue working.

Schools generally had been very understanding and proactive in engaging children: They offered activities (e.g., online music groups), physical and emotional support and zoom calls for families. One family reported that their child who had free school lunches got home packed lunches delivered, which was invaluable to them.

However, in contrast, some families felt that schools were less supportive, especially when they were unwilling to accommodate a vulnerable child, despite the families wanting the child to go to school. There was also concern about lockdown exit and future school arrangements regarding social distancing, leading to families worrying that their child may not be welcome to return to school.

Some families feel that school do not want them back … they said … this is an excuse for school not to want my child (Physiotherapist).

Comments regarding home schooling were variable, and some reported that it had been beneficial for their child particularly in terms of mental health and well‐being for the whole family. Some young people had made life choices to leave college or school, and some families were thinking of continued home schooling in preference to re‐integration into school.

3.3.5. Innovation—Shaping future services

The adjustments during initial lockdown gave parents, clinicians and managers insight into how family preference and feedback could shape future services. In the event of another lockdown, clinicians noted how they could better anticipate issues to ensure families had appropriate support, and this feedback has led to services being maintained in second lockdown:

I would not redeploy the epilepsy nurse specialist ‐ a couple of children really ran into trouble with seizures and just did not have anyone to contact … that's such a key relationship … (Consultant Paediatrician in Neurodisability).

A regular comment was that a later start in the school day would be helpful:

Our children, they have got really complex needs and we know they have to be ready for a taxi at 7:30–8 am in the morning and spend two hours in transport … the families were saying that it's lovely we can get up when they are ready … we get up and have breakfast and are more relaxed (Consultant Paediatrician in Neurodisability).

Clinicians felt they would like to advocate for this flexibility of school start times in future. They spoke of changing their practice in terms of supporting Education Health and Care Plans and felt more confident advocating for children to start school later in the day to allow adequate sleep, breakfast, medications and preparation for the day.

4. DISCUSSION

The initial lockdown over Spring and Summer 2020 in response to the COVID‐19 pandemic significantly impacted on the well‐being of children, young people with severe physical neurodisability and their families. Anxiety and mental health issues were common concerns expressed by the parents to clinicians and were further exacerbated by the clinical, financial and social uncertainties of lockdown. Clinicians were concerned about the cumulative effect of multiple missed appointments and reduced local and regional healthcare services. Each individual missed appointment may not have massive impact, but with uncertain duration of the pandemic and lockdown periods, the effect of multiple missed health, education and social care encounters is likely to have profound effect on long term outcomes for children, young people and their families (Fegert et al., 2020; Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, 2020b). The burden of health and care needs of children with severe physical neurodisability is significant, and families are at an increasingly high risk of burnout (Ketelaar et al., 2008; Raina et al., 2005).

During the recovery and restoration phase of the pandemic, our findings highlight that despite significant service re‐configuration, there remains an ongoing need for further change. The rapid development of technology for virtual appointments has facilitated opportunity for easier access to tertiary support for families and access to joint multidisciplinary working across primary, secondary and tertiary services. However, face‐to‐face clinical reviews remain essential, and practical hands‐on support in the child's environment, at home and school, remains challenging. More so than ever before, clinical services are required to be adaptive to individual family circumstances. We have learnt much from this reflection, and the impact of the second lockdown on clinical service pathways, processes and waiting list is markedly reduced. Data metrics shows services have been maintained and communication improved.

The uncertainty regarding the definition of vulnerability and those children who should be shielded still remains, but the regularly reviewed guidance from the U.K. Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) is welcomed. Interpretation of the guidance, however, remains challenging, with many of our population having conditions in the RCPCH category B.

Conditions listed in the categories below will require a case‐by‐case discussion … This decision will depend on the severity of the condition and knowledge that the secondary and tertiary care clinical teams have of the particular circumstances of the child (Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, 2020a).

This study of experienced clinician experiences is reflected in contemporaneous studies and published work from others (e.g., Cerebral Palsy Scotland, 2020). Health, education and third sector professional organizations have provided evidence that lobbying for government policy is vital to ensure that all children, and in particular those with significant health and social care needs, are protected and continue to access services (British Academy of Childhood Disability, 2020; Royal College of Occupational Therapists, 2020; Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, 2020c).

Since preparation and submission of this manuscript, there has been significant further understanding of the impact of the pandemic and subsequent lockdown on the health and well‐being of all children and young people. There has been concerning and significant impact on the physical and mental health of typically developing children and young people (Heyman et al., 2021; Public Health England, 2021), children with neurodevelopmental disorders (Nonweiler et al., 2020) and disabled children (Council for Disabled Children, 2021; Couper‐Kenney & Riddell, 2021). These publications add validity to the authors' observations and fears at the time of this study and reflect the other published early concerns regarding the potential collateral damage to children in the United Kingdom as a result of lockdown and social distancing (Crawley et al., 2020).

Moving forwards as we hopefully exit the COVID‐19 pandemic, re‐integration of children into school, respite provision and accessing healthcare remains challenging, particularly with respect to those who require daily health interventions, such as those who have a tracheostomy, and require suction, oxygen or non‐invasive ventilation (aerosol generating procedures). A recent study has demonstrated that 24% of disabled children have not returned to school fulltime following the lockdown due to child anxiety, school guidance (not safe to return) and lack of school support (Disabled Children's Partnership, 2020). Helpful guidance has been produced for providers (Council for Disabled Children, 2020; Department of Education Government of the United Kingdom, 2020), but implementation is not always straightforward and may differ depending on the availability of local resources.

4.1. Limitations

The primary limitation of this study is that it involves clinicians from a single department and is based on a service review of vulnerable patients from one tertiary service. Although the patient population was derived from 5 of 7 NHS England regions, our findings may not generalize to other centres or regions. Furthermore, due to the way the service evaluation was structured, it did not directly capture the anxiety of children and young people with learning and or communication difficulties. This is important as although this subgroup may have increased anxiety due to COVID‐19, they may not always have the capacity to understand or express concerns about the future. As a result, the clinicians occasionally believed that parents may have given responses that they thought the clinicians wanted to hear rather than what was reality, especially regarding questions around challenges of service provision.

The qualitative analysis of the parent's comments and clinician focus group provided a unique perspective on the service evaluation. Future studies would benefit from including the young person's perspective more directly, particularly capturing the experience of young people with learning and communication challenges. Whilst the current study did not specifically examine other populations of children (e.g. other chronic clinical conditions or children with specific behavioural challenges as a primary phenotype), it is likely that the health and social themes identified would be similar; however, there will be different personal factors that affect the experience. All children in the United Kingdom were and remain subjected to reduced activity and participation during uncertain times (Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, 2020b). Despite these limitations, this study provides insight into the health and care of children and young people with severe physical neurodisability and their families during COVID‐19.

4.2. Conclusion

This study reflects the clinicians' perspective of the diversity of family experience of the COVID‐19 pandemic and lockdown, both positive and negative, in the early stages of the pandemic. Significant impact has now been seen in the entire U.K. population, but the complexity of care needs for children with severe physical needs amplifies this. The authors are reassured by approaches in the second and subsequent waves of the pandemic that aim to maintain education provision and protect children's health and social care services; these include recommendations to prevent re‐deployment of allied health professionals. However, the longevity of the ongoing pandemic and impact on related health, economic and psychosocial outcomes for children, young people and their families remains uncertain. Only hindsight and long‐term epidemiological studies can adequately assess the impact for this population.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors (JC, JG, TA, AP, ST, SB, AM, DL and CF) made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article and final approval of the version to be published.

Supporting information

Data S1. Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We acknowledge the support of the Maria Marina Foundation in supporting our work.

Cadwgan, J. , Goodwin, J. , Arichi, T. , Patel, A. , Turner, S. , Barkey, S. , McDonald, A. , Lumsden, D. E. , & Fairhurst, C. (2021). Care in COVID: A qualitative analysis of the impact of COVID‐19 on the health and care of children and young people with severe physical neurodisability and their families. Child: Care, Health and Development, 1–11. 10.1111/cch.12925

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Authors elect to not share data due to its identifiable nature.

REFERENCES

- Arichi, T. , Cadwgan, J. , McDonald, A. , Patel, A. , Turner, S. , Barkey, S. , & Fairhurst, C. (n.d., under review). Care in the time of COVID‐19: Impact on complex neurodisability. Child: Care, Health and Development. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- British Academy of Childhood Disability . (2020). BACD Position Statement: Services for children and young people with disabilities during COVID‐19. https://www.bacdis.org.uk/posts/166-bacd-position-statement-services-for-children-and-young-people-with-disabilities-during-covid-19

- Carter, B. , Bennett, C. V. , Jones, H. , Bethel, J. , Perra, O. , Wang, T. , & Kemp, A. (2020). Healthcare use by children and young adults with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 63, 75–80. 10.1111/dmcn.14536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerebral Palsy Scotland . (2020). Life after lockdown – Survey Results. https://cerebralpalsyscotland.org.uk/life-after-lockdown-survey-results/

- Council for Disabled Children . (2020). The Department for Education has published updated guidance for for full opening of special schools and other specialist settings. https://councilfordisabledchildren.org.uk/news-opinion/news/department-education-has-published-updated-guidance-full-opening-special-schools-and-other

- Council for Disabled Children . (2021). Lessons Learnt From Lockdown: The highs and lows of the pandemic's impact on disabled children and young people. https://councilfordisabledchildren.org.uk/resources/all-resources/filter/inclusion-send/lessons-learnt-lockdown-highs-and-lows-pandemics

- Couper‐Kenney, F. , & Riddell, S. (2021). The impact of COVID‐19 on children with additional support needs and disabilities in Scotland. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 36(1), 20–34. 10.1080/08856257.2021.1872844 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley, E. , Loades, M. , Feder, G. , Logan, S. , Redwood, S. , & Macleod, J. (2020). Wider collateral damage to children in the UK because of the social distancing measures designed to reduce the impact of COVID‐19 in adults. BMJ Paediatrics Open, 4(1), e000701. 10.1136/bmjpo-2020-000701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, E. , Shelly, A. , Waters, E. , Boyd, R. , Cook, K. , & Davern, M. (2010). The impact of caring for a child with cerebral palsy: Quality of life for mothers and fathers. Child: Care, Health and Development, 36(1), 63–73. 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00989.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Education Government of the United Kingdom . (2020). What specific steps should be taken to care for children with complex medical needs, such as tracheostomies? https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/safe-working-in-education-childcare-and-childrens-social-care/safe-working-in-education-childcare-and-childrens-social-care-settings-including-the-use-of-personal-protective-equipment-ppe#what-specific-steps-should-be-taken-to-care-for-children-with-complex-medical-needs-such-as-tracheostomies

- Disabled Children's Partnership . (2020). The return to school for disabled children after lockdown. https://disabledchildrenspartnership.org.uk/back-to-school-poll/

- Eunson, P. (2015). The long‐term health, social, and financial burden of hypoxic‐ischaemic encephalopathy. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 57(Suppl 3), 48–50. 10.1111/dmcn.12727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fegert, J. M. , Vitiello, B. , Plener, P. L. , & Clemens, V. (2020). Challenges and burden of the coronavirus 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: A narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 14(1), 20. 10.1186/s13034-020-00329-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman, I. , Liang, H. , & Hedderly, T. (2021). COVID‐19 related increase in childhood tics and tic‐like attacks. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 106, 420–421. 10.1136/archdischild-2021-321748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ipsos MORI . (June 2020). The Health Foundation COVID‐19 Survey: A Report of Survey Findings Ipsos MORI

- Ketelaar, M. , Volman, M. J. M. , Gorter, J. W. , & Vermeer, A. (2008). Stress in parents of children with cerebral palsy: What sources of stress are we talking about? Child: Care, Health and Development, 34(6), 825–829. 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00876.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonweiler, J. , Rattray, F. , Baulcomb, J. , Happé, F. , & Absoud, M. (2020). Prevalence and associated factors of emotional and Behavioural difficulties during COVID‐19 pandemic in children with neurodevelopmental disorders. Children (Basel), 7(9), 128. 10.3390/children7090128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palisano, R. , Rosenbaum, P. , Walter, S. , Russell, D. , Wood, E. , & Galuppi, B. (1997). Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 39(4), 214–223. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1997.tb07414.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkes, J. , Caravale, B. , Marcelli, M. , Franco, F. , & Colver, A. (2011). Parenting stress and children with cerebral palsy: A European cross‐sectional survey. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 53(9), 815–821. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.04014.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price‐Haywood, E. G. , Burton, J. , Fort, D. , & Seoane, L. (2020). Hospitalization and mortality among black patients and white patients with Covid‐19. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(26), 2534–2543. 10.1056/NEJMsa2011686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health England (2021). COVID‐19 mental health and wellbeing surveillance: Report. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-mental-health-and-wellbeing-surveillance-report/7-children-and-young-people

- Raina, P. , O'Donnell, M. , Rosenbaum, P. , Brehaut, J. , Walter, S. D. , Russell, D. , Swinton, M. , Zhu, B. , & Wood, E. (2005). The health and well‐being of caregivers of children with cerebral palsy. Pediatrics, 115(6), e626–e636. 10.1542/peds.2004-1689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, J. , & Spencer, L. (1994). Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In Bryman A. & Burgess R. G. (Eds.), Analyzing Qualitative Data (pp. 173–194). Routledge. 10.4324/9780203413081_chapter_9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Occupational Therapists . (2020). Coronavirus (COVID‐19). https://www.rcot.co.uk/coronavirus-covid-19-0

- Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health . (2020a). COVID‐19—'shielding' guidance for children and young people. https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/sites/default/files/generated-pdf/document/COVID-19---%2527shielding%2527-guidance-for-children-and-young-people.pdf

- Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health . (2020b). [Open letter from UK paediatricians about the return of children to schools].

- Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health . (2020c). Restoring children's health services, COVID‐19 and winter planning ‐ position statement. https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/restoring-childrens-health-services-covid-19-winter-planning-position-statement

- Stevens, S. , & Pritchard, A. (2020, 17/3/2020). [Important and Urgent—Next Steps on NHS Response to COVID‐19].

- Stokes, E. K. , Zambrano, L. D. , Anderson, K. N. , Marder, E. P. , Raz, K. M. , Felix, S. E. B. , Tie, Y. , & Fullerton, K. E. (2020). Coronavirus Disease 2019 Case Surveillance—United States, January 22–May 30, 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69, 759–765. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6924e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2007). International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health: Children & Youth Version: ICF‐CY. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

Authors elect to not share data due to its identifiable nature.