To date, studies on anti‐severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) vaccine efficacy in blood cancers show that different responses may be observed according to the haematological malignancy diagnosis, stage of disease and ongoing treatment. Immune responses are often lower compared to healthy controls, second doses appear to be crucial, and most of the evidence rely on tests of neutralising antibody response, not the full range of immune response or clinical outcomes. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 We do not know how long immunity lasts in such patients, and there is uncertainty about the most reliable serological tests and cut‐off values by which to identify the responders and track the putatively neutralising antibodies’ titres.

To address some of these questions, we prospectively analysed the anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 spike (S) protein immunoglobulin G (IgG) titres over multiple time‐points (TPs), and monitored clinical outcomes [asymptomatic infections and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19)], after two doses of 30 µg 3 weeks apart of BNT162b2 in 182 consecutive patients with different malignancies [chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML), n = 20; myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN), n = 42; multiple myeloma (MM), n = 50; and B‐cell non‐Hodgkin lymphoma (B‐NHL), n = 70] enrolled in an observational monocentric study. At vaccination, patients with CML, MPN and MM were on active treatment, while patients with B‐NHL were on active therapy or within 6 months from the end of such therapy, all negative for a previous SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. The present report is the first one focussing on 12‐week serological kinetics in different blood cancers. The present study was controlled by a cohort of 36 subjects aged >80 years without cancer and approved by the Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico (IRCCS) Central Ethical Committee of Regione Lazio in January 2021 (Prot. N‐1463/21). Anti‐S IgG titres were measured before the first dose (TP0), after 3 weeks on the occasion of the second dose (TP1), and after 5 (TP2) and 12 weeks (TP3) from the first dose by a chemiluminescent immunoassay (Diasorin, Saluggia, Italy). 11 At TP3, neutralising antibodies were also evaluated by angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE2)‐receptor binding domain (RBD) neutralisation assay (Dia.pro, Milan, Italy). 12 Nasopharyngeal swabs for real‐time polymerase chain reaction testing (Anatolia geneworks, Istanbul, Turkey) 13 were taken at TP0, TP1, and in all the cases of clinical suspicion of COVID‐19 or hospital access.

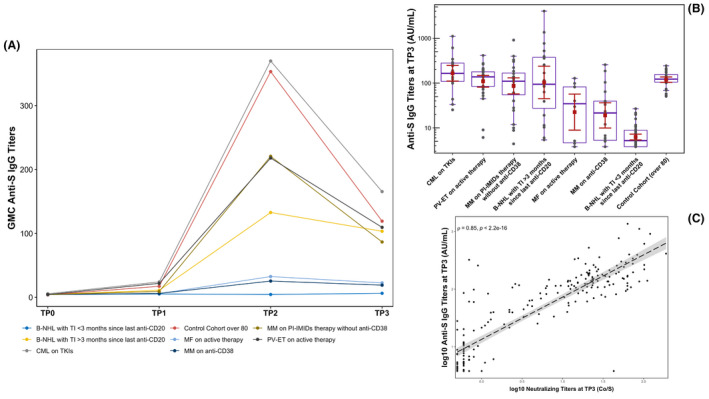

The 182 patients and 36 controls characteristics and immunogenicity data at TP2 have already been published for the MM, CML and MPN subsets 7 , 8 and are unpublished for B‐NHL. Among the patients with B‐NHL the median age was 68 years, with a slight prevalence of indolent lymphomas and patients on induction or maintenance systemic therapy. Based on the prediction of serological response to BNT162b2 at TP2, cohorts of MM, MPN and B‐NHL were split according to treatment with or without an anti‐cluster of differentiation (CD)38 monoclonal antibody (moAb), diagnosis of myelofibrosis (MF) or polycythaemia vera (PV)/essential thrombocythaemia (ET), and time interval (TI) since last anti‐CD20 moAb administration to vaccination within or beyond 3 months respectively. In this way, seven different cohorts were identified (Table I; Fig 1A), the first four responsive, the last three weakly responsive or not responsive at all to vaccination: CML on tyrosine kinase inhibitors (first cohort, n = 20), PV and ET on active therapy grouped together (second cohort, n = 32), MM on proteasome inhibitors and/or immunomodulatory imide drugs without anti‐CD38 moAb (third cohort, n = 32), B‐NHL with TI >3 months since last anti‐CD20 administration (fourth cohort, n = 19), MF on active therapy (fifth cohort, n = 10), MM on anti‐CD38 moAb (sixth cohort, n = 18), B‐NHL with TI <3 months since last anti‐CD20 administration (seventh cohort, n = 51).

Table I.

Geometric mean concentrations of anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 IgG and response rates according to seven different cohorts of haematological malignancy patients compared to a control cohort at 5 and 12 weeks after BNT162b2 vaccination.

| Control cohort (aged >80 years) |

First cohort CML on TKIs |

Second cohort PV‐ET on active therapy@ |

Third cohort MM on PI‐IMIDs therapy without anti‐CD38 |

Fourth cohort B‐NHL with TI >3 months since last anti‐CD20 |

Fifth cohort MF on active therapy@ |

Sixth cohort MM on anti‐CD38 |

Seventh cohort B‐NHL with TI < 3 months since last anti‐CD20 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP2: Fifth week from the first dose of BNT162b2 vaccine | ||||||||

| Patients’ number | 36 | 20 | 32 | 32 | 19 | 10 | 18 | 51 |

| GMC (95% CI), au/ml [P] | 353·3 (261·7–459·8) | 369·8 (225·0–558·7) [P = 0·720] | 217·9 (131·7–337·1) [P = 0·158] | 220·7 (122·4–386·9) [P = 0·320] | 132·7 (48·5–345·9) [P = 0·068] | 32·4 (11·3–92·0) [P < 0·001] | 25·4 (14·5–43·8) [P < 0·001] | 4·7 (4·0–5·8) [P < 0·001] |

| Responders at the cut‐off value ≥ 15 au/ml, n (%) [P] # | 36 (100) | 20 (100)* | 30 (93·8) [P = 0·218] | 30 (93·8) [P = 0·218] | 15 (78·9) [P = 0·011] | 6 (60) [P = 0·001] | 10 (55·6) [P < 0·001] | 1 (2·0) [P < 0·001] |

| Responders at the cut‐off value ≥ 80 au/ml, n (%) [P] # | 35 (97·2) | 19 (95) [P = 1] | 29 (90·6) [P = 0·336] | 23 (71·9) [P = 0·005] | 13 (68·4) [P = 0·005] | 4 (40) [P < 0·001] | 5 (27·8) [P < 0·001] | 0 (0) [P < 0·001] |

| TP3: 12th week from the first dose of BNT162b2 vaccine | ||||||||

| Patients’ number (dropouts versus TP2) | 28 (8) | 20 (0) | 32 (0) | 32 (0) | 19 (0) | 10 (0) | 17 (1) | 50 (1)** |

| GMC (95% CI), au/ml [P] | 119·1 (102·2–138·2) | 165·4 (111·2–243·2) [P = 0·075] | 109·4 (79·6‐145·2) [P = 0·684] | 86.5 (56·1–128·3) [P = 0·382] | 103·3 (46·7–231·7) [P = 0·712] | 22·5 (8·6–58·1) [P < 0·001] | 18·9 (10·0–38·0) [P < 0·001] | 6·2 (5·4–7·3) [P < 0·001] |

| Responders at the cut‐off value ≥ 15 au/ml, n (%) [P] # | 28 (100) | 20 (100)* | 30 (93·8) [P = 0·494] | 28 (87·5) [P = 0·116] | 15 (78·9) [P = 0·022] | 6 (60) [P = 0·003] | 9 (52·9) [P < 0·001] | 5 (10·0) [P < 0·001] |

| Responders at the cut‐off value ≥ 80 au/ml, n (%) [P] # | 22 (78·6) | 17 (85) [P = 0·716] | 24 (75) [P = 0·770] | 22 (68·8) [P = 0·559] | 12 (63·2) [P = 0·324] | 4 (40) [P = 0·045] | 3 (17·6) [P < 0·001] | 0 (0) [P < 0·001] |

| Responders with putative protection at the ratio Co/S > 10, n (%) [P] ## | 22 (78·6) | 17 (85) [P = 0·716] | 26 (81·3) [P = 1] | 20 (62·5) [P = 0·259] | 9 (47·4) [P = 0·034] | 1 (11·9) [P = 0·001] ^ | 2 (11·8) [P < 0·001] | 0 (0) [P < 0·001] |

Statistics: cohorts were compared using Fisher’s exact test for categorical data and the Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables. The geometric mean values were calculated as exp mean{[log(value)]}. CIs for GMCs were calculated based on logarithm of titres. All P values were two‐sided, and those < 0·05 were considered statistically significant. Analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS®, version 20; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

au, artificial units; B‐NHL, B‐cell non‐Hodgkin lymphoma; CI, confidence interval; CML, chronic myeloid leukaemia; ET, essential thrombocythemia; GMC, geometric mean concentration; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IMIDs, immunomodulatory imide drugs; MM, multiple myeloma; PI, proteasome inhibitor; PV, polycythaemia vera; SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2; TI, time interval; TKIs, tyrosine kinase inhibitors; TP, time‐point; MF, myelofibrosis; @ hydroxycarbamide, ruxolitinib, interferon α, anagrelide.

Anti SARS‐CoV‐2 S1/S2 IgG determination was performed by the Liaison® SARS‐CoV‐2 S1/S2 IgG assay (DiaSorin, Saluggia, Italy). 11 This is a quantitative chemiluminescent immunoassay (CLIA), fully automated on the LIAISON XL platform, for the detection of IgG antibodies against the subunits S1 and S2 of SARS‐CoV‐2 Spike protein. The subunits S1 and S2 are responsible for binding and fusion of virus to host cell, respectively, and are both targets of neutralising antibodies. According to the manufacturers’ technical manual, the result of a Liaison SARS‐CoV‐2 S1/S2 IgG test is positive with a signal of ≥15 au/ml, equivocal between 12 and 15 au/ml and negative below 12 au/ml. The cut‐off to discriminate positive and negative results was individuated on the basis of the 94·4% concordance between the Liaison IgG titre of 15 au/ml and the Plaque Reduction Neutralisation Test 90% (PRNT90) at 1:40 ratio. At a Liaison value of 80 au/ml a concordance of 100% with a 1:160 PRNT90 titre was observed. 13

Angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE2)‐receptor‐binding domain (RBD) Neutralising Assay (Dia.pro, Milan, Italy) 12 was used at TP3 to detect neutralising antibodies (NAbs) in an isotype‐independent manner using purified RBD and the host cell receptor ACE2. The test is a surrogate Virus Neutralising Test (sVNT), a method that mimics the virus–host interaction in an enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay platewell. The RBD‐ACE2 interaction can be neutralised by specific NAbs in patient sera. The calculation of inhibition and the quantitative measurement of NAbs was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The results are interpreted as a ratio of the cut‐off value (Co) and the sample OD450 nm/620 nm (S). A Co/S > 10 indicates an efficient immunisation and vaccination effectiveness. 14

No statistics were computed because responders were a constant.

Death from lymphoma progression.

One of the 10 patients with MF was not tested by ACE2‐RBD Neutralising Assay because of sample unavailability.

Fig 1.

(A) Geometric mean concentrations (GMCs) of anti‐severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) spike protein immunoglobulin G (IgG; au/ml) according to seven different cohorts of haematological malignancy patients + control cohort at basal (TP0) and at 3 (TP1), 5 (TP2) and 12 (TP3) weeks after BNT162b2 vaccination (first dose at TP0 and second at TP1). GMC values are reported as points at each TP. (B) Summary distribution of the anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2‐ spike protein IgG levels at TP3 according to seven different cohorts of blood cancer patients + control cohort. Antibody concentrations measured in artificial units per ml (au/ml) in the ordinate axis are depicted on a log‐10 scale to better capture the full range. Values of each sample are shown in dark grey; the red square corresponds to the geometric mean of each cohort and the red whiskers correspond to the relative 95% confidence interval (CI); in purple the relative boxplot of each cohort, with median and 25th and 75th percentiles. In the fourth cohort the inter‐individual variability is related to vaccination timing, with antibody levels progressively higher as vaccination moves away from the last administration of anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody (moAb) starting from 3 months onwards. (C) Correlation between neutralising antibodies (Dia.pro®) and anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 Spike IgG titres (Diasorin®) at TP3 in the whole population. Each value is log‐10 scaled. Correlation analysis is carried out with ‘Spearman’ method and the relative ‘rho’ coefficient is equal to 0·85. A two‐sided statistical test was performed. The dashed line represents the linear regression and the relative CI. CML (chronic myeloid leukaemia) on TKIs (tyrosine kinase inhibitors) (first cohort); PV (polycythaemia vera)‐ET (essential thrombocythaemia) on active therapy grouped together (second cohort); MM (multiple myeloma) on PI (proteasome inhibitors) and/or IMiDs (immunomodulatory imide drugs) without anti‐CD38 moAb (third cohort); B‐NHL (B‐cell non‐Hodgkin lymphoma) with TI (time interval) > 3 months since last anti‐CD20 administration (fourth cohort); MF (myelofibrosis) on active therapy (fifth cohort); MM on anti‐CD38 moAb (sixth cohort); B‐NHL with TI <3 months since last anti‐CD20 administration (seventh cohort); control cohort (aged >80 years with no cancer).

Focussing on TP3, two cohorts’ clusters may be observed (Table I; Fig 1A,B). The first cluster is represented by still largely serologically immunocompetent patients from the first four cohorts, in which the antibody decay kinetics varies by magnitude among the cohorts determining, regardless of the zenith reached, their close grouping alongside the control cohort, with an average loss of around 50–65% in terms of geometric mean concentrations (GMCs) of anti‐S antibodies and putative seroprotection rates ranging from 50% to 85%. The second cluster is represented by heavily immunocompromised patients from the last three cohorts, who display flat kinetics, with seroprotection rates of around 0–10% at 12 weeks. Booster vaccinations will likely be required based on kinetics, although the most appropriate timing remains currently unknown and probably different depending on the membership in one or the other cluster. Longitudinal assessments of the two mRNA vaccines with and without prior SARS‐CoV‐2 infection using quantitative enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) of anti‐RBD antibodies in the general population demonstrate that the titres wane with kinetics very similar to that seen after mild natural infection, resulting in an average of ∼90% loss within 90 days. 14 The discrepancy between these results and ours at 3 months could be related to the different assays used.

The titres of anti‐S IgG and neutralising antibodies were significantly correlated in the whole study population (Spearman’ rho = 0·85, P < 0·001; Fig 1C), with protection rates calculated at the cut‐off value ≥80 artificial units/ml (au/ml) for the anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 S1/S2 IgG assay (DiaSorin) and at the ratio Co/S >10 for the ACE2‐RBD neutralising assay (Dia.pro) rather superimposable (Table I). This reproducibility of results between the two assays we used appears comforting for the purposes of the widest possible serological monitoring of these patients. The choice of the reference cut‐off appears fundamental to discriminate patients hypothetically protected by adequate levels of putatively neutralising antibodies.

An asymptomatic SARS‐CoV‐2 infection was documented in two patients belonging to the third and seventh cohort when nasopharyngeal swabs were taken as surveillance before their hospital access on 9 July 2021. Genomes were analysed by next‐generation sequencing with the Illumina COVIDSeq Test on a Nextseq 500, Illumina Inc.® 15 (San Diego, CA, USA). The lineage assigned by the Phylogenetic Assignment of Named Global Outbreak Lineages (PANGOLIN) web‐based software was B.1.617.2 in both cases, with genome coverage of 92·48% and 91·42% respectively (Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Dataset ID: EPI_ISL_2983378 and EPI_ISL_2983377). No cases of COVID‐19 were reported. To date, the contagion has remained low despite the wide viral circulation due to the Delta variant. It would be important to correlate the humoral immunity data with those of cellular immunity, in order to verify whether also serologically unresponsive patients develop an efficient post‐vaccine adaptive immunity.

Author contributions

Francesco Marchesi had a major contribution in constructing the dataset, interpreting the data and writing the manuscript. Fulvia Pimpinelli implemented the laboratory platforms to carry out the study, performed all serological and molecular tests, validated, and interpreted the results and signed the reports. Eleonora Sperandio carried out the statistical analysis. Elena Papa and Paolo Falcucci collected the signed informed consents and clinical data for the construction of the dataset. Martina Pontone contributed by performing serological and molecular tests. Simona di Martino and Luisa de Latouliere were in charge of preservation of serum at the biological bank. Giulia Orlandi performed the next‐generation sequencing. Aldo Morrone conceived and developed the study. Gennaro Ciliberto conceived and developed the study. Andrea Mengarelli contributed to develop the study, construct the dataset, interpret the data, perform the statistical analysis and write the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding information

No special funds were used. Diagnostic tests were part of the diagnostic routine.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to all the I. F. O.‐COVID‐19‐Team: Ilaria Cavallo, Andrea Cazzani, Ilaria Celesti, Ludovica Ciuffreda, Giovanna D’agosto, Francesca De Nicola, Martina Diano, Sara Donzelli, Antonio Federico, Fulvia Fraticelli, Lorenzo Furzi, Frauke Inger Karen Goeman, Alessia Lauretti, Francesca Maione, Alice Massacci, Arianna Mastrofrancesco, Carla Mottini, Francisco Obregon, Matteo Pallocca, Silvia Paluzzi, Sara Petrolo, Grazia Prignano, Valentina Ricca, Serena Salvo, Eleonora Sperandio, Elisabetta Trento.

References

- 1. Monin L, Laing AG, Muñoz‐Ruiz M, McKenzie DR, del Molino del Barrio I, Alaguthurai T, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of one versus two doses of the COVID‐19 vaccine BNT162b2 for patients with cancer: interim analysis of a prospective observational study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:765–78. 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00213-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bird S, Panopoulou A, Shea RL, Tsui M, Saso R, Sud A, et al. Response to first vaccination against SARS‐CoV‐2 in patients with multiple myeloma. Lancet Haematol. 2021;8:e389–e392. 10.1016/S2352-3026(21)00110-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harrington P, Doores KJ, Radia D, O'Reilly A, Lam HP, Seow J, et al. Single dose of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) induces neutralising antibody and polyfunctional T‐cell responses in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2021. [Online ahead of print]. 10.1111/bjh.17568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Harrington P, de Lavallade H, Doores KJ, O’Reilly A, Seow J, Graham C, et al. Single dose of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine against SARS‐CoV‐2 induces high frequency of neutralizing antibody and polyfunctional T‐cell responses in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2021. [Online ahead of print]. 10.1038/s41375-021-01300-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Herishanu Y, Avivi I, Aharon A, Shefer G, Levi S, Bronstein Y, et al. Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID‐19 vaccine in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2021;137:3165–73. 10.1182/blood.2021011568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roeker LE, Knorr DA, Thompson MC, Nivar M, Lebowitz S, Peters N, et al. COVID‐19 vaccine efficacy in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2021. [Online ahead of print]. 10.1038/s41375-021-01270-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pimpinelli F, Marchesi F, Piaggio G, Giannarelli D, Papa E, Falcucci P, et al. Fifth‐week‐immunogenicity and safety of anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 BNT162b2 vaccine in patients with multiple myeloma and myeloproliferative malignancies on active treatment: preliminary data from a single Institution. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14:81. 10.1186/s13045-021-01090-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pimpinelli F, Marchesi F, Piaggio G, Giannarelli D, Papa E, Falcucci P, et al. Lower response to BNT162b2 vaccine in patients with myelofibrosis compared to polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14:119. 10.1186/s13045-021-01130-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Van Oekelen O, Gleason CR, Agte S, Srivastava K, Beach KF, Aleman A, et al. Highly variable SARS‐CoV‐2 spike antibody responses to two doses of COVID‐19 RNA vaccination in patients with multiple myeloma. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:1028–30. 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ghione P, Gu JJ, Attwood K, Torka P, Goel S, Sundaram S, et al. Impaired humoral responses to COVID‐19 vaccination in patients with lymphoma receiving B‐cell directed therapies. Blood. 2021. [Online ahead of print]. 10.1182/blood.2021012443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Diasorin (Saluggia, Italy) . DiaSorin’s LIAISON® SARS‐CoV‐2 diagnostic solutions. 2021. [cited 2021 July 28]. Available from: https://www.diasorin.com/en/immunodiagnostic‐solutions/clinical‐areas/infectious‐diseases/covid‐19

- 12. Dia.pro (Milan, Italy) . COVID‐19 – ELISA. 2021. [cited 2021 July 28]. Available from: https://www.diapro.it/products/ace2‐rbd‐neutralization‐assay‐elisa

- 13. Anatolia geneworks, (Istanbul, Turkey) . Novel coronavirus (2019‐nCoV) & variant detection kits. 2021. [cited 2021 July 28]. Available from: http://www.anatoliageneworks.com/en/kits/novel‐coronavirus‐2019‐ncov‐detection‐kits

- 14. Ibarrondo FJ, Hofmann C, Fulcher JA, Goodman‐Meza D, Mu W, Hausner MA, et al. Primary, recall, and decay kinetics of SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine antibody responses. ACS Nano. 2021;15:11180–91. 10.1021/acsnano.1c03972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Illumina Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA) . Illumina COVIDSeq test. 2021. [cited 2021 July 28].Available from: https://emea.illumina.com/products/by‐type/ivd‐products/covidseq.html