Blood transfusion is among the most frequently performed medical procedures in the USA, 1 yet the history of this life‐saving practice is mired in controversy, beginning with the barring of African‐Americans from donating blood. 2 , 3 , 4 Following criticism of this policy, the American Red Cross (ARC) instead began segregating and labelling blood such that the product could be easily identifiable as being from an African‐American blood donor. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 The ARC anticipated that recipients would refuse blood transfusions from African‐American donors, as their blood was deemed infectious and the medium through which diseases such as sickle cell anaemia were transmitted, despite a consensus that this disease is genetic. 5 , 6 Even after the official de‐segregation of the nation’s blood supply, several states passed legislation requiring hospitals and physicians to inform blood transfusion recipients of the blood donor’s race. 3 , 7

To encourage blood donation during the mid‐twentieth century, a controversial advertisement by the US National Blood Program depicted blood moving from white women to white men. 3 This ensured that gender, race, and sexuality would not influence the transfusion process and assuaged recipients’ fears of receiving blood from a same‐sex donor or a donor with a different sexual orientation. 3 In the 1980s, the AIDS pandemic resulted in laws prohibiting specific populations from donating blood, 8 as many considered this to be a disease exclusive to members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) community. Several of these laws have only recently begun to change, despite the blood supply in the USA being completely voluntary, anonymous, and safer than it has ever been.

Although major improvements in blood donation and transfusion have been accomplished, individual and societal views of blood transfusion remain controversial in the USA. As physicians, we are involved in consenting patients who might require blood transfusion as part of their medical care. This consent process involves safe and effective communication, the provision of factual, evidence‐based information, and a clear explanation of the risks, benefits, and alternatives, including the right to blood refusal. This refusal of blood can lead to a delicate bioethics debate, as individuals may refuse blood for any number of reasons, including those based on personal religious or moral beliefs. These discussions and therapeutic dilemmas have contributed to advancements in bloodless surgery, patient blood management, and evidence‐based transfusion guidelines. However, as history has illustrated, a subset of individuals representing a specific patient population may refuse blood based on misconceptions and misinformation, or even overt bigotry, prejudice, or discrimination.

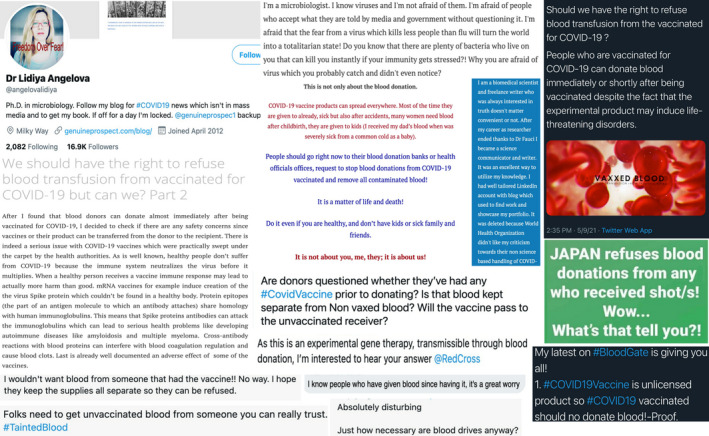

Unfortunately, in the USA we have recently begun to encounter patients refusing blood based solely on the COVID‐19 vaccination status or COVID‐19 infection history of the blood donor. These patients have adamantly demanded that physicians disclose details of the donor from whom they may potentially receive blood, including whether the donor received a COVID‐19 vaccine. These same patients, some of whom are likely to imminently require blood, have refused to consent to transfusion unless they can be assured that the blood donor did not receive a COVID‐19 vaccine, regardless of the risk of morbidity and mortality. Prevailing thought processes among this population include concerns of becoming infected with COVID‐19 or developing long‐term effects from the vaccine itself via the blood transfusion, beliefs that the vaccine is a device created for genetic modification by those with ulterior motives, or that people who choose to receive a vaccine are in some way inferior. 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 While these ideologies appear to be most prevalent in North America, particularly in the USA, they are not isolated to a single hospital or specific geographic region of the country, as physicians from multiple institutions across the USA have been approached by patients directly, or consulted by other physicians questioning how to best address these concerns. These occurrences have become an issue to such extent that the AABB (formerly the American Association of Blood Banks) 14 and Canadian Blood Services 15 have issued guidance on how to address circumstances in which patients requiring blood transfusion request blood from unvaccinated donors. This underscores the magnitude of this alarming trend of misinformation regarding COVID‐19 vaccination and blood safety, influenced by intentionally misleading or blatantly false discussions, particularly on social media, e.g. Fig 1. This inaccurate information may harm patients in need of blood, but who refuse it based on false beliefs or conspicuous prejudice. Despite this, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and many of the largest blood donor organizations in the USA, including the ARC, New York Blood Center, and OneBlood, have not published easily accessible information refuting this false information.

Fig 1.

Examples of images, posts, and discussions from social media websites regarding COVID‐19 vaccinated blood donors and blood transfusions. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Currently, there are varying deferral periods for blood donors who received a COVID‐19 vaccine, 16 but these timeframes are organization‐ and vaccine‐dependent, ranging from no deferral to 28 days (Table I). Despite the variation in deferral policies, there is no evidence that blood donations from COVID‐19‐vaccinated donors pose any risk to recipients, and blood transfusions from donors who received a COVID‐19 vaccination or previously had COVID‐19 are not associated with a risk of COVID‐19 infection. 14 Therefore, there are no requirements to collect or share the vaccination status of the blood donor, and hospitals are not made aware of or required to inform patients of the vaccination status of the blood donor. Blood product labels contain only the necessary information relevant to appropriate and safe use of the blood product, such as the blood type, and do not report the vaccination status of any donor, nor do they contain information pertaining to race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, or other demographic factors.

Table 1.

Recommended blood donation deferral periods.

| Organization | Non‐live vaccine | Live vaccine | Indeterminate |

|---|---|---|---|

| WHO 24 |

|

|

|

| US FDA 25 |

|

|

|

| AABB 26 |

|

|

|

| Canadian Blood Services 15 |

|

||

| Joint United Kingdom Blood Transfusion and Tissue Transplantation Services Professional Advisory Committee 27 |

|

|

|

| European Centre for Disease Prevention Control 28 |

|

|

|

WHO, World Health Organization; US FDA, United States Food and Drug Administration; AABB, formerly the American Association of Blood Banks.

Protection of blood donors and the blood supply is vitally important, and thus donor anonymity must be maintained. To protect donors, donation facilities, and blood banks from liability in the absence of negligence, blood shield statutes have been enacted throughout the USA. 17 Established in the 1950s and 1960s, these laws specify that blood donation and blood products are a service and not a sale, and therefore blood donors cannot be prosecuted and held liable if the blood transfusion results in injury. 17 , 18 The intention of these legal statues is to preserve the health and welfare of the population by ensuring an adequate supply of blood for all those who may require it, 17 and therefore serve as the legal basis for protection and anonymity of donors. The importance of donor anonymity is recognized by numerous organizations, and is crucial for maintenance of the relationship between volunteer blood donors and blood transfusion services, and to prevent stigma and discrimination of the blood donor. This right to privacy, confidentiality, and anonymity is one of the foundational principles of the medical code of ethics. 19

The appalling circumstances African‐Americans endured relating to the blood supply and segregation during the 20th century in the USA are in no way fully comparable; however, it is impossible to ignore the parallels between this infamous past and the misconceived notions, and sometimes outright prejudice, that individuals are displaying toward those who have been vaccinated for COVID‐19 and are willing to donate today. A precedent may be set that is similar to the stigmatization in the early days of blood donation and transfusion if policies that require blood unit labels to include vaccination status are instituted to appease patients refusing blood from certain individuals. Thus, while the current policy expressed by AABB and similar organizations asserts that blood product labels do not necessitate inclusion of donor COVID‐19 vaccination status, we suggest that additional actions be taken to ensure that donor vaccination status remain anonymous. We implore hospitals and other medical facilities to adopt policies and protocols to address the concerns of patients who refuse blood on these grounds. The implementation of ethics boards and active engagement of these experts during care of these patients can be beneficial. Furthermore, we believe the prevalence of misinformation requires enhanced awareness of this emerging societal issue and believe that blood donation organizations and the US FDA must publicize and promote guidance refuting the misinformation propagating throughout the USA. Additional measures at the local, state, and national level must be taken to dispel these thought processes and ensure appropriate patient care is provided to all persons, while preventing discrimination and the perpetuation of falsehoods. We are in the midst of an historical event, as the COVID‐19 pandemic has resulted in more than 4·2 million deaths and greater than 200 million infections worldwide. 20 However, the impact of this event is not limited to infections or deaths, as COVID‐19 misinformation has influenced and polarized politics, government, science, and media, 21 , 22 , 23 and has created the next controversy in a contentious history of blood transfusion.

References

- 1. Pfuntner A, Wier LM, Stocks C. Most frequent procedures performed in U.S. hospitals, 2010. HCUP Statistical Brief #149. February 2013. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Available from: http://www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb149.pdf. [PubMed]

- 2. American Red Cross . History of Blood Transfusions. Available from: https://www.redcrossblood.org/donate‐blood/blood‐donation‐process/what‐happens‐to‐donated‐blood/blood‐transfusions/history‐blood‐transfusion.html. [Accessed 6 Aug 2021].

- 3. Woo S. When blood won’t tell: integrated transfusions and shifting foundations of race. Am Stud. 2017;56(1):5–28. 10.1353/ams.2017.0000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Guglielmo TA. “Red Cross, double cross”: Race and America s world war II‐era blood donor service. J Am Hist. 2010;97(1):63–90. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jordan J. A war on two fronts: race, citizenship, and the segregation of the blood supply during World War II. Penn History Review. 2018;24(2):32–70. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wailoo K. Genetic marker of segregation: sickle cell anemia, thalassemia, and racial ideology in American medical writing 1920–1950. Hist Philos Life Sci. 1996;18(3):305–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. George R. The Intersection of Race and Blood. The New York Times [Internet]. 14 May 2019; Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/14/well/live/blood‐type‐race‐racial.html [Accessed 10 Aug 2021].

- 8. Karamitros G, Kitsos N, Karamitrou I. The ban on blood donation on men who have sex with men: time to rethink and reassess an outdated policy. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;27:99. 10.11604/pamj.2017.27.99.12891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fact Check‐ It is safe to receive a blood donation from a vaccinated person. Reuters. Available from: https://www.reuters.com/article/factcheck‐blood‐idUSL2N2NC12D. Published 25 May 2021. [Accessed 9 Aug 2021].

- 10. Facebook. Available from: https://m.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=2904966896452751&id=100008184070258 [Accessed 9 Aug 2021].

- 11. Chamberlin AM. No, you can't get the COVID‐19 vaccine from a blood transfusion. verifythis.com. Available from: https://www.verifythis.com/article/news/verify/health‐verify/no‐you‐cant‐get‐the‐covid‐19‐vaccine‐from‐a‐blood‐transfusion/536‐063b7235‐1716‐43b3‐bc4e‐e1a401f7ff38. Published 12 May 2021. [Accessed 9 Aug 2021].

- 12. Angelova DL. We should have the right to refuse blood transfusion from vaccinated for COVID‐19 but can we? Part 4 – Solution. genuineprospect. Available from: https://genuineprospect.com/2021/05/05/we‐should‐have‐the‐right‐to‐refuse‐blood‐transfusion‐from‐vaccinated‐for‐covid‐19‐but‐can‐we‐part‐4‐solution/amp/?__twitter_impression=true. Published 8 May 2021. [Accessed 9 Aug 2021].

- 13. Angelova DL. We should have the right to refuse blood transfusion from vaccinated for COVID‐19 but can we? Part 3. genuineprospect. Available from: https://genuineprospect.com/2021/04/30/we‐should‐have‐the‐right‐to‐refuse‐blood‐transfusion‐from‐vaccinated‐for‐covid‐19‐but‐can‐we‐part‐3/. Published 2 May 2021. [Accessed 10 Aug 2021].

- 14. AABB . AABB vaccination and blood donation. Available from: https://www.AABB.org/docs/default‐source/default‐document‐library/regulatory/aabb‐vaccination‐and‐blood‐donation‐flyer.pdf?sfvrsn=1043750c_0 [Accessed 6 Aug 2021].

- 15. Canadian Blood Services . COVID‐19 vaccines and blood donation. Available from: https://www.blood.ca/en/covid19/vaccines‐and‐blood‐donation [Accessed 9 Aug 2021].

- 16. Gupta AM, Jain P. Blood donor deferral periods after COVID‐19 vaccination. Transfus Apher Sci. 2021;103179. Online ahead of print. 10.1016/j.transci.2021.103179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Williams JL. Patient safety or profit: what incentives are blood shield laws and FDA regulations creating for the tissue banking industry? Indiana Health Law Rev. 2005;2(1):295–328. 10.18060/16461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shu‐Acquaye F. Human blood and its transfusion: the twist and turns of legal thinking. Quinnipiac Health L J. 2005;9(1):33–68. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Blood Donor Counselling: Implementation Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. 4, Ethical and legal considerations in blood donor counselling. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK310579/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. WHO Coronavirus (COVID‐19) Dashboard . World Health Organization. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/ [Accessed 10 Aug 2021].

- 21. Loomba S, de Figueiredo A, Piatek SJ, de Graaf K, Larson HJ. Measuring the impact of COVID‐19 vaccine misinformation on vaccination intent in the UK and USA. Nat Hum Behav. 2021;5(3):337–48. 10.1038/s41562-021-01056-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Agley J, Xiao Y. Misinformation about COVID‐19: evidence for differential latent profiles and a strong association with trust in science. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):89. 10.1186/s12889-020-10103-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Roozenbeek J, Schneider CR, Dryhurst S, Kerr J, Freeman ALJ, Recchia G, et al. Susceptibility to misinformation about COVID‐19 around the world. R Soc Open Sci. 2020;7: 1–15. 10.1098/rsos.201199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. World Health Organization . Maintaining a safe and adequate blood supply and collecting convalescent plasma in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic. World Health Organization. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO‐2019‐nCoV‐BloodSupply‐2021‐1. Published 17 Feb 2021. [Accessed 10 Aug 2021].

- 25. Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research . Updated Information for Blood Establishments Regarding COVID‐19. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines‐blood‐biologics/safety‐availability‐biologics/updated‐information‐blood‐establishments‐regarding‐covid‐19‐pandemic‐and‐blood‐donation?utm_medium=email&utm_source. Published 19 Jan 2021. [Accessed 10 Aug 2021].

- 26. AABB . Updated Information from FDA on Donation of CCP, Blood Components and HCT/Ps, Including Information on COVID‐19 Vaccines, Treatment with CCP or Monoclonals. Available from: https://www.AABB.org/docs/default‐source/default‐document‐library/regulatory/summary‐of‐blood‐donor‐deferral‐following‐covid‐19‐vaccine‐and‐ccp‐transfusion.pdf?sfvrsn=91eddb5d_. Published 14 Apr 2021. [Accessed 9 Aug 2021].

- 27. Joint United Kingdom (UK) Blood Transfusion and Tissue Transplantation Services Professional Advisory Committee . JPAC ‐ Transfusion Guidelines – Coronavirus Vaccination. Available from: https://www.transfusionguidelines.org/dsg/ctd/guidelines/coronavirus‐vaccination [Accessed 10 Aug 2021].

- 28. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . Suspected adverse reactions to COVID‐ 19 vaccination and the safety of substances of human origin. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Suspected‐adverse‐reactions‐to‐COVID‐19‐vaccination‐and‐safety‐of‐SoHO‐final‐with‐erratum.pdf. Published 3 Jun 2021. [Accessed 9 Aug 2021].