Abstract

Background

In the face of unprecedented challenges because of coronavirus disease 2019, interdisciplinary pediatric oncology teams have developed strategies to continue providing high‐quality cancer care. This study explored factors contributing to health care resilience as perceived by childhood cancer providers in all resource level settings.

Methods

This qualitative study consisted of 19 focus groups conducted in 16 countries in 8 languages. Seven factors have been previously defined as important for resilient health care including: 1) in situ practical experience, 2) system design, 3) exposure to diverse views on the patient's situation, 4) protocols and checklists, 5) teamwork, 6) workarounds, and 7) trade‐offs. Rapid turn‐around analysis focused on these factors.

Results

All factors of health care resilience were relevant to groups representing all resource settings. Focus group participants emphasized the importance of teamwork and a flexible and coordinated approach to care. Participants described collaboration within and among institutions, as well as partnerships with governmental, private, and nonprofit organizations. Hierarchies were advantageous to decision‐making and information dissemination. Clinicians were inspired by their patients and explained creative trade‐offs and workarounds used to maintain high‐quality care.

Conclusions

Factors previously described as contributing to resilient health care manifested differently in each institution but were described in all resource settings. These insights can guide pediatric oncology teams worldwide as they provide cancer care during the next phases of the pandemic. Understanding these elements of resilience will also help providers respond to inevitable future stressors on health care systems.

Keywords: COVID‐19, global, pediatric oncology, qualitative research

Short abstract

This multinational, multicenter, qualitative study illustrates how pediatric oncology providers used resilient health care strategies, illuminating creative solutions to mitigate impact, many of which may outlast the pandemic.

Introduction

Health care systems have been overwhelmed by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic. In addition to millions of deaths directly from the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 virus, overburdened health systems contribute to increased morbidity and mortality. 1 Patients with chronic disease, including cancer, are particularly vulnerable. 2 The COVID‐19 pandemic has caused delays accessing cancer care including prompt diagnosis and referrals to tertiary centers, as well as interruptions in ongoing treatment and surveillance. 3 , 4 For children with cancer, these effects are greatest in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs) 5 , 6 where >90% of children with cancer live 7 and where health care systems were already strained. 8

As the pandemic has progressed, qualitative studies have focused on the experiences 9 and individual resilience strategies 10 of health care providers. 11 , 12 Increased use of telehealth 13 and posttraumatic growth 14 emerged as positive outcomes with the potential to outlive the pandemic. However, much of the current literature focuses on high‐income countries and has examined pandemic resilience exclusively in single‐center studies.

Resilient health care focuses on patient safety 15 and emphasizes factors that enable teams, units, and organizations, rather than individuals, to effectively adapt to challenges. Seven factors have been defined as essential to resilient health care: 16 (1) in situ practical experience, in which health care professionals use their knowledge and experience within a system to build resilient behaviors, (2) system design, which considers system factors that contribute to safety and efficiency, (3) exposure to diverse views and perspectives on the patient's situation, which allows providers to understand the patient's perspective and decreases the likelihood of bias, (4) protocols and checklists, to help standardize action in unpredictable situations, (5) teamwork, consisting of effective team meetings, communication, leadership, and teamworking structure, (6) workarounds, which enable staff to adapt to challenges, and (7) trade‐offs, positive solutions developed by clinical staff to resolve stress. This study evaluated how these factors were applied by pediatric oncology teams and institutions in countries of varying resource‐levels to navigate the ongoing COVID‐19 pandemic.

Materials and Methods

The institutional review board (IRB) at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (SJCRH) reviewed and approved the study with SJCRH serving as the coordinating center. Additional approval was obtained as required by local IRBs. Methods are reported using the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research Guidelines. 17

Study Design

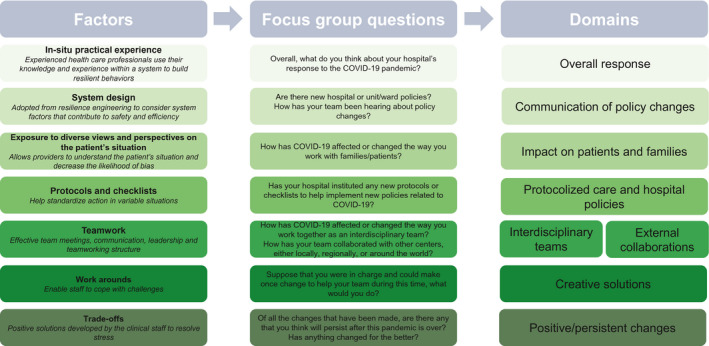

Seven factors previously identified as important to resilient health care 16 were used to frame the study and design focus group questions, which were then transformed into domains used for data analysis (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Resilient health care framework. Seven factors adopted from the literature on resilient framework (left) were used to guide questions used to facilitate focus groups (middle). Eight domains (right) correlating with these factors were derived from the focus group questions and used to guide rapid analysis.

Participants and Setting

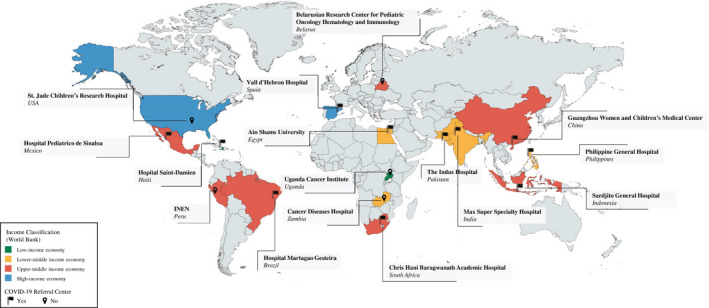

This was the second component of a cross‐sectional exploratory sequential mixed‐methods study designed to investigate the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on the care of children with cancer. Participants for the qualitative sample were purposefully selected 18 from participants in a cross‐sectional survey 19 to include institutions representing all income groups as defined by the World Bank 20 and all world regions as defined by the World Health Organization. 21 Survey results were used to sample institutions caring for a large number of pediatric oncology patients and that experienced substantial impact from the COVID‐19 pandemic. Ultimately, 16 different institutions in 16 countries were selected (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Focus group institutions. Colors indicate income classification of each country as defined by the World Bank.

At each institution, a principal investigator (PI) identified focus group participants including multidisciplinary frontline providers and stakeholders who were directly involved in pandemic institutional response including administrators, parent representatives, and directors of nonprofit foundations supporting childhood cancer (Supporting material 1). At 3 institutions (United States, Philippines, and Spain), based on local PI preference, 2 focus groups were held, separating hospital administrators from bedside providers. Each focus group was conducted in the official language of the participating country.

Data Collection

A semi‐structured focus group guide (Supporting material 2) was created based on the 7 factors for resilient health care and iteratively revised after piloting. This guide was developed in English, translated into 7 other languages, and back‐translated or reviewed by bilingual members of the research team. 22 All focus groups were conducted virtually using an online video‐conferencing platform. Each focus group was moderated by 2 bilingual facilitators. Audio recordings of virtual focus groups were professionally transcribed and translated into English. Translated transcripts were de‐identified, reviewed, and compared to audio recordings by bilingual members of the research team to ensure clarity and accuracy of translation.

Data Analysis

This qualitative study leveraged rapid turnaround analysis 23 to provide timely results during an ongoing pandemic. Rapid turnaround analysis yield results consistent with traditional qualitative analysis 24 and is considered an efficient approach for conducting qualitative research during the evolving COVID‐19 pandemic. 25 Analysis was structured by a previously published health care resilience framework, 16 with domains defined based on revision of the original framework and influenced by transcript review. Through this process, “teamwork” was split into 2 domains: “interdisciplinary teams,” exploring relationships and interactions between providers in the institution, and “external collaborations,” exploring cooperative work between institutions or hospitals and the private or public sector. The other 6 factors were mapped directly to domains through questions from the focus group guide (Fig. 1). Domains were applied consistently across transcripts. Four researchers (D.E.G., E.S., A.A., and D.C.M.) analyzed transcripts using a summary template based on the 8 domains (Supporting material 3). Results from this analysis were compiled into matrices to review as study findings. 26

Results

Nineteen focus groups were conducted at 16 institutions, including publicly and privately funded hospitals serving diverse populations, with some designated as COVID‐19 referral centers (Supporting material 4). All 7 factors of resilient health care were relevant to all teams during the COVID‐19 pandemic response, regardless of the country income level. Representative excerpts illustrating each domain are included in Tables 1, 2, and 3.

TABLE 1.

Focus Group Excerpts Regarding 4 Domains: In Situ Practical Experience, System Design, Exposure to Diverse Views on Patient Experience, and Protocols and Checklists

| Factor | Excerpts |

|---|---|

| In situ practical experience | “Under the leadership of our director they made the most amazing plan of how we were going to handle the pandemic. So, I think we had many challenges on the way and that plan had to be revised, but I think it was a brilliant plan.” (South Africa) |

| “As the head of a department I have reflected on whether there were any deficiencies in the early days, from the end of January to March. It is far from a perfect job, with flaws on work force allocation to the patient administration…there cannot be a one‐size‐fits all approach.” (China) | |

| “I think we responded pretty operationally effectively, since we started preparing for it before, the strain was registered in the system database, before the first case of Coronavirus. When we found out that the virus had entered our country, we were already ready for it.” (Belarus) | |

| “I think St. Jude did a really good job and I was very pleased to see that as things evolved, St. Jude changed with those. So, you know, it was the land of the unknown and I think that they responded very well.” (United States) | |

| “I think…many of the hospitals ‐‐ actually tried to emulate the practices in Philippine General Hospital, even our infographics got disseminated to the other hospitals and…even our decisions such as which PPE we choose to recommend for our staff, people are really paying attention.” (Philippines) | |

| System design | “In the beginning most orders came from the health ministry. Next, the centers made key decisions. Then, the hospitals determined, adapted, and implemented the recommendation based on the local statistics. Every department head then implemented these recommendations, and the teams followed suit.” (Belarus) |

| “The hospital administration reported to us and we were communicating it to everyone in charge of their work…. we created a WhatsApp group with the head of the department and all staff, hematology and oncology units, each head of hematology, oncology, or pediatric unit…any decision or any notification is shared via the WhatsApp group. Then it is officially shared in the general departments of the hospitals. Then each department manager shares it to his staff members in his unit.” (Egypt) | |

| “In the oncology department there was always a doctor… in the morning, he would have a small meeting with the staff available on site to see the effect of the pandemic from the data published by the Ministry of Public Health; and then we would talk about the statistics of Saint Damien Hospital, because we also have a bulletin at the hospital on COVID made by [Infection Control leads] that we publish every week, and we would talk about it, we would discuss for 10 minutes and then the message we were getting across; so the nurse educator and the nurse would meet with the parents, the patients, to sensitize them, to educate them.” (Haiti) | |

| “Just now, we discussed how the information is conveyed. We share accurate scientific knowledge and guidelines from official channels or We Media through WeChat groups.” (China) | |

| Exposure to diverse views on the patient's situation | “We decreased our outpatient visitors…we postponed their visits and called them…we made a WhatsApp group on which patients used to get their CBC done at a nearby laboratory…Similarly our blood bank had a mobile blood bank services and they used to visit different places in the city and used to collect the blood at their doorstep…. |

| In terms of our psychosocial services what we did was we started tele‐counseling for the patients…we were able to contact them on‐call and talk to them and their families…one of our services is that we have a school for our oncology patients…what we started was a distance learning program.” (Pakistan) | |

| “It seems it's going to be a long way until they can give this support again, which was a support to caregivers, to propose activities to children, to offer this fresh air, this connection with the healthiest part of the child…all that totally stopped. I think this part, the most playful one that is very particular to pediatric patients, in this case oncology, and all the help to caregivers who have a baby, an older boy but they cannot leave anyone in charge as they did before… this entire part has been seriously affected.” (Spain) | |

| “Before COVID‐19, these waiting homes used to be full because cancer patients who live far away from the hospital would stay there. Since COVID‐19, however, residents living around the waiting homes became hesitant to have patients in those homes. Everything about the hospital, especially Sardjito Hospital, became a source of fear.” (Indonesia) | |

| “We had these wards full to the capacity in that when we talk of distancing, we had no distance in between, since they're more than crowded…Though these days it is improving but still we are still crowded because most of the time hostels are full. We try to work with them, we work with them. When there's space, we find space for those who can go to hostel.” (Uganda) | |

| Protocols and checklists | “We've had charts put around the wards on the use of personal protective equipment by staff. There has been training specifically…and there is a plan and duty rosters at various service provision points for swapping of the outpatients as well as inpatient [staff].” (Zambia) |

| “We had changed our way of working, not everyone comes at the same time, we do shifts where the doctors work four consecutive days after going into quarantine for 10 days. We also made changes with groups and the way people work, we made arrangements for isolation, we only used masks, caps, and we made signs all over the hospital…these are protective measures we must have: checking the temperature before entering the hospital and before leaving each department.” (Haiti) | |

| “I worked for two weeks in the COVID isolation; I was following this protocol. It facilitates the work, it's like a flowchart to make things clear.” (Egypt) | |

| “But now, we already have the flowcharts, more protection equipment, we feel more secure, even though there are still several things to improve.” (Peru) | |

| “I have to say every single thing is an algorithm. So, there's nothing it's left chance. We realized that if you have algorithms in place then it's much easier to import policies and it also makes more sense, it also makes it easier for people to follow the algorithms.” (Philippines) | |

| “There have been a lot of modifications and a lot of algorithms, management pathways and things were like formatted. The good thing was our team was constantly meeting, discussing, improvising, learning, and trying to incorporate the day‐to‐day basis research which was guiding us which way to go.” (Pakistan) |

Abbreviations: CBC, complete blood count; COVID, coronavirus disease; COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019; PPE, personal protective equipment.

TABLE 2.

Focus Group Excerpts: Teamwork

| Domain | Excerpts |

|---|---|

| Interdisciplinary teams | “I think the interdisciplinary work has been improving …I think the main characters in the decision making for [COVID] patients, especially in the infectious disease department, pulmonology, and ICU…all of that was improved in order to optimize the resources and the patient care… they were always open to debate or discuss about certain cases, especially oncology patients.” (Mexico) |

| “I think that in a context like this obviously the interaction with all the specialties has increased… In our service, for example, we have much more interaction with the infectious diseases service, we hold more meetings with surgery, I think this is something that this pandemic implies.” (Spain) | |

| “We were all pretty nervous at first and so we texted each other constantly. It was like we had this group chat going on 24 hours a day for probably the first couple of weeks because we were all like really nervous. And we shared every bit of information and discussed every article that came out and we were kind of all over it.” (United States) | |

| “I think I will have to say that for pediatric oncology I think we are working better because all the multidisciplinary team meetings are in via Zoom, so the attendance has improved like 100%.” (Philippines) | |

| “One thing that the pandemic has brought us and that I like very much is that we now do a multidisciplinary work. We all get together and we share our opinions debating how we can do things. We're now united, we have reached unity… We've learned to be united to achieve a common goal. Not everything in the pandemic is bad, we've achieved unity.” (Peru) | |

| “It makes a huge difference when you look right, and you look left and everyone has got their sleeves rolled up and are doing the work and I think that makes a huge difference and that's a testament to everyone that we work with. There was no one that shied away from work or used this as an excuse to do less work or to stay at home or to not come to work or –yeah I thought everyone from that point of view, it was‐‐ yeah it's been great.” (South Africa) | |

| “The support and encouragement of each other, because when a person gets tired and they have no more enthusiasm, it's easy to give up and say, “I can't do this anymore.” But when you see a colleague, who try in some sense to share the work, and help each other, then you get extra strength. Well, we of course try to encourage each other, in the sense of oversight of each other, and gave advice to each other, helped each other, because we all have families and other people we come in contact with, so we try to give advice to each other, when we are exhausted, or when there is something in the throat, then we talk and seek advice with each other about what to do, and that's how we support each other.” (Belarus) | |

| External collaborations | “Thankfully we all [oncologists and NGOs] coordinated together…to get the children into the hospital and make sure they all…are being taken care of and the treatment is being provided.” (India) |

| “We had a collaboration group of several oncologists…some came to us to share the experience, not only here in Brazil but we received several emails from people outside of Brazil asking how to treat, since we had many cases of oncology (patients) with positive (COVID tests).” (Brazil) | |

| “We have relied heavily on other centers that are credited to do the SARS‐CoV‐2 testing… But also, the reverse is that we have been supporting the COVID treatment unit with laboratory testing for the critical laboratory diagnostics.” (Uganda) | |

| “Patients that are COVID positive who we could not accommodate were sent to [another institution]. This is because of the understanding that we had developed with them. This helped us a lot also. That that we could send patients to institute that we knew would take care of them.” (Pakistan) |

Abbreviations: COVID, coronavirus disease; ICU, intensive care unit; NGO, nongovernmental organization; SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 virus.

TABLE 3.

Focus Group Excerpts: Workarounds and Trade‐Offs

| Workarounds | ||

|---|---|---|

| Creative Solution | Excerpts | Country |

| Outdoor rounds | “Previously we used to do grand ward rounds at the bedside, so with all the oncologist fellows nursing staff and so through this time we haven't done them at the bedside, but we have done them socially distanced either outside or in reception area.” | South Africa |

| Decorating masks | “The masks children wore were decorated with toys, shapes and colors. Actually, at first, the patient was putting on a mask. He was the only one in family to wear a mask… They see everyone wearing masks, which encourage them to wear masks. It was bothering for them to wear masks alone. At first, it was challenging. Now everyone wears the mask, and it is familiar.” | Egypt |

| “Internet hospital” | “Nowadays, we introduce the e‐hospital for consultation of the patient or offering some medical services and assistance. In our e‐hospital, we give support and consulting online. Due to reduced patients, some guidelines are accessible in our e‐hospital when some doctors work from home. We encourage our doctors to give consultation and advice in our e‐ hospitals. It can then reduce the risk of cross‐infection when they come to the hospital and relieve some of their psychological worries.” | China |

| Made hand sanitizer in the hospital | “Fortunately, at the hospital level, at the pharmacy level we already knew how to prepare a hydroalcoholic gel and we just kept on doing it but increasing the quantity to prepare, so our consumption tripled and quadrupled.” | Haiti |

| Laundry and food delivery services for patients | “The leadership allowed them to wash their close at the hospital too, to prevent exposure of the parents if they had to go out and get it done. At the beginning, parents would go downstairs to the laundry service, but we knew the virus moves when people move, so it was decided that parents stayed with their children and the technical staff would recollect their dirty clothes, and return it clean.” | Peru |

| Monthly mental health meetings for patients and families | “She [patient navigator] has been having a monthly mental health meeting with the patients. And through those meetings she has been inviting the patients and through different lectures and as well as updates of how the patients are feeling during this time of pandemic.” | Philippines |

| Child life playrooms turned into “worry free zones” for staff | “So, earlier the area which was used as a play area for the kids we converted it into a worry‐free zone where the nursing staff, the housekeeping staff, the doctor, the residents could come in throughout the day and spend the time and you know, do some art activities. We had like childhood games over there. So, they could come and release their stress in that area.” | Pakistan |

| Scales sent home with patients for weight checks | “Another good thing that came out were, you know, patients were coming back just for weight changes. I mean, for just to check their weight. And so, scales were sent home with families or delivered to housing.” | United States |

| Danced as a greeting instead of hugging | “Personally, what I tried was to replace the hug with a handshake, we say it's an elbow kiss, I did little dances with patients. There was a patient who asked me not to be admitted and then I ended up not admitting her and she was dancing, and I went dancing with her. Trying to keep what we have of bonding but in another way.” | Brazil |

| Colored hospital zones | “These zones are determined by the probability of COVID‐19 happening. There are three zones: green, yellow, and red… And these zones determine the PPE level that we use.” | Indonesia |

| Trade‐Offs (Excerpts) | ||

| “In some respects, the changes have been positive on the patients…when COVID started we're seeing fewer patients and we're spending more time per patient.” (Uganda) | ||

| “I think it is about healthy living habits, wearing masks even though I do not feel so optimistic about [people wearing masks] as much as about hand washing because people feel the benefit of hand washing…. I think this COVID‐19 teaches people that we cannot take illnesses lightly.” (Indonesia) | ||

| “The virtual meetings, even after the return of office meetings. And that's definitely going to make it easier for senior staff. Attending international meetings from their place and costing less. And I also think that the educational part. Very improved for senior staff. And that's one of the things that's going to go on.” (Egypt) | ||

| “On the positive side COVID‐19 has taught people to practice hand hygiene like maybe like when you come in the ward the first thing that you think of is washing hands.” (Zambia) | ||

| “I think that together with the nursing staff we're more alert to detect symptoms not just only associated with COVID, so that makes us be more alert.” (Mexico) | ||

| “COVID has probably taught us, you know, how to manage with the fewer resources. It has probably led us to look for new ways to reduce costs.” (India) | ||

Abbreviations: COVID, coronavirus disease; COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019.

In Situ Practical Experience

Focus group participants included experienced multidisciplinary professionals with deep institutional knowledge. As a factor of resilient health care, “in situ practical experience” refers to the ability of providers to use their knowledge and experience to build resilient behaviors within a system. This was apparent as participants described their institution's overall response to the pandemic, reflecting on the importance of flexibility, triage, preparation, and a coordinated effort with identified team leaders (Table 1). Specifically, participants noted how teams benefited from continuous adaptation and many described their institution's response improving over time. Groups of providers learned from in situ practical experience during the pandemic and adjusted to emphasize successful strategies or pivot when things went poorly. In some hospitals, such as in the Philippines, providers described how their institution was recognized as leading the response by providing national pandemic guidance. In other institutions, preexisting system deficiencies were exposed by further stress during the pandemic. In the United States and Indonesia, providers expressed concern about a lack of transparency in decision‐making. In other institutions, such as in Spain, providers worried that children with cancer were not prioritized during their institution or country's pandemic response.

System Design

National and institutional responses to the pandemic were described by health care providers as “top down.” At some institutions, such as in Belarus, providers described how COVID‐19 policies were developed by ministries of health and communicated to hospital administrators, who determined center‐specific implementation strategies. In other centers, policies were developed by hospital administrators or multidisciplinary COVID‐19 task forces. Hospital administrators communicated new policies to department heads, who subsequently passed the information on to their teams. Providers received many forms of communication including written policies, emails, and electronic messages through applications such as WhatsApp and WeChat. In Haiti, required training sessions were developed around new policy initiatives, and in China, providers had to pass examinations related to COVID‐19. Bedside providers, including nurses and residents, were most often responsible for talking with patients and families, including announcement of policy changes, often through calls or text messages before scheduled appointments. Institutions used public notice boards that included posters and flyers with pictographs to communicate to families with limited literacy. In some locations, volunteer networks (China) or patient navigators (Philippines) helped providers connect with families.

Two different types of communication were described by focus group participants: formal notices and less formal information sharing. In both cases, the method of communication was seen as less important than the process behind policy development. Participants discussed the importance of shared decision‐making and a desire to be included as stakeholders, emphasizing the need for transparency and flexibility. Frequent communication was viewed positively, “I really appreciate it, especially in the early days [the CEO] sending out emails all the time and kind of keeping us updated” (United States). Inconsistencies and discrepancies between governmental and institutional policies were distressing to providers and difficult to relate to families (Table 1).

Exposure to Diverse Views on the Patient's Situation

The experience of patients and families was at the center of focus group discussions (Table 1). Providers at all institutions discussed drastic changes to patient care because of the pandemic. Some described care as less “holistic,” stripped of ancillary services including psychosocial support, child life, and hospital‐based schooling. Cancer care was delayed for patients with COVID‐19 and because of medications shortages, and some patients were unable to attend appointments because of transportation restrictions or financial limitations. Additional restrictions at the hospitals also changed care. Providers described stigma associated with being diagnosed with COVID‐19, and requirements for testing (Zambia) or masks (Haiti) were deterrents to patients seeking care at some centers. Safety precautions also changed interactions between families and providers; “I couldn't hug the patients anymore, I couldn't hold the children in my lap anymore” (Brazil). Visitor restrictions were difficult everywhere but particularly for cultures where extended family members are typically involved in decision‐making: “Often those patients [and parents] would be accompanied by the eldest to the hospital so that the situation can be explained to all of them, and unfortunately that was not possible” (South Africa). Nonessential visits were deferred resulting in providers seeing patients less frequently. Focus group participants understood their patients would prefer to be seen at the cancer center and described families feeling frightened, panicked, and abandoned. Despite this emotional toll, most providers reported families were compliant, gracious, grateful, and understanding of the changes to care delivery. Additional examples of resilience derived from providers' empathizing with the experiences of their patients and families are included in Table 1.

Protocols and Checklists

Some institutions used protocols or checklists to implement policies, whereas others collated centralized guidelines but did not use specific operational algorithms (Table 1). In at least 1 institution, administrators described protocols and implementation aids of which bedside providers were unaware. In all centers, providers emphasized the need to frequently update protocols to respond to emerging knowledge around the virus and changing institutional practices.

Teamwork

Interdisciplinary teams

Providers in all institutions described how changes because of the pandemic initially made interdisciplinary collaboration more difficult. Teams were physically divided, with fewer providers in the hospital. Leaner teams and physical distance made teamwork challenging, but providers adapted (Table 2). Teams met virtually, and many providers felt the virtual space made interdisciplinary meetings more accessible. Providers developed increased respect for disciplines that had been removed from care or transitioned to remote work (eg, psychologists, child‐life specialists, and dieticians). Clinicians expressed a sense of comradery and worked together toward a common goal while connecting personally over shared trauma, protecting one another's physical and mental health: “We really need to work as a team, we need each other. Alone we can't do it” (Brazil).

External collaborations

Various external collaborations were described (Table 2), including hospital collaborations within a country, a region, and around the world. Hospitals cooperated to ensure necessary medications, testing capabilities, and personal protective equipment were available. Providers in countries affected later, such as Haiti, learned from colleagues who had already experienced the pandemic, such as those in China. The care of children with cancer, which historically has relied on tertiary treatment centers, was modified to be as decentralized as possible. Institutions with strong referral pathways leaned on established relationships to facilitate laboratory draws and administer chemotherapy locally to minimize need for travel. In places where referral pathways were not as strong, new collaborations were formed, “We did a lot of work in terms of networking with other hospitals…most of our patients do not actually live within the city…So we have to look for other pediatric oncologists who can take them in…We did a lot of identifying who these oncologists are and…how these patients can go to these oncologists” (Philippines). In addition, hospitals worked with ministries of health, foundations, nongovernmental organizations, and academic institutions to coordinate pediatric cancer care throughout the pandemic.

Workarounds

Providers in every focus group described unique and creative solutions that helped them cope with challenges and eased the impact of the pandemic on patients, families, and health care workers (Table 3). Many of these workarounds focused on humanizing the response to COVID‐19 and optimizing resources.

Trade‐offs

In addition to “workarounds,” participants discussed new skills and ideas that might outlast the pandemic, including how they learned to manage with fewer resources and maximize what they had: “One of the things that we notice is that we have learned to be able to do more with less, less human resources and also less finances as well” (Uganda). The 2 most commonly described positive outcomes were increased awareness of infection control and increased technology usage in patient care, interdisciplinary team meetings, and education: “I would say ‘thank you corona’ because after corona and COVID in Pakistan, we realize that people realize the infection control is very important for our hospital setting” (Pakistan). Telemedicine, as well as local access to labs and chemotherapy, allowed patients to make fewer trips to the cancer center and receive care closer to home. Some participants also described improvements to patient care for patients at the center; because of fewer clinic patients, providers spent more time with each patient and quickly received laboratory results. Several participants also felt that clinician mental health had been prioritized during the pandemic and noticed increased awareness regarding the importance of work‐life balance (Table 3).

Discussion

Interdisciplinary teams included in this study demonstrated resilience while caring for pediatric oncology patients in the face of extraordinary challenges presented by the COVID‐19 pandemic. Providers in settings of various resource levels reflected on the myriad ways they had persevered, demonstrating that factors previously identified as important to resilient health care 16 were both used and perceived to be effective in all settings during pandemic response. These findings are particularly useful because they build on existing literature, predominantly focused on the impact of COVID‐19 2 , 4 or resilience as it relates to individuals, 27 , 28 and provide insight into strategies for resilient health care leveraged by global pediatric oncology teams.

In this global study, more similarities than differences were noted. These findings imply that identified components of resilient health care are relevant regardless of institutional resource‐level or location and may be used to mitigate the unequal impact of the pandemic on low‐ and middle‐income countries. 26 In particular, resilient health care was fostered by experienced teams who reacted to evolving information and worked together within larger health care systems. Participants referenced effective strategies recommended in existing literature including hospital reorganization, the creation of COVID‐free zones, screening programs, and interhospital collaboration 27 and described positive adaptations that may outlast the pandemic. The creativity portrayed by these providers highlights human ingenuity and a consistent drive to find light during a dark time.

Several themes interconnected components of resilient health care. These included the importance of frequent and transparent communication as well as a dynamic institutional pandemic response that evolved and adapted to new knowledge and changing circumstances. System agility 29 and coordinated multisystem responses 30 were previously highlighted as COVID‐19 resilience strategies in both high‐ and low‐income countries. The importance of communication, however, has been underemphasized. Previous work depicted technology as an efficient and productive method of communication during the pandemic; 13 however, our study demonstrates that the method of communication used by leadership during the pandemic was not as important as its content and frequency. In particular, participants described the importance of being included as stakeholders and being consistently informed of changing policies. Communication contributed to resilient health care by allowing coordination within and among teams, empowering them to respond to frequent changes in care delivery.

As with all qualitative studies, our findings are not meant to be explicitly generalizable, but rather to describe in‐depth the perspectives of included participants. However, by including multidisciplinary providers from a range of settings, we captured varied opinions and found many shared experiences that provide valuable insights to a diverse audience. It is possible that the heterogenous nature of our focus groups created hesitancy among certain participants to speak up (eg, nurses voicing their opinions in front of physicians or administrators). To mitigate this concern, we engaged a multidisciplinary research team, and each site was offered the opportunity to host separate focus groups for bedside providers and hospital leadership. Ultimately, our study included nurses as site leads for certain institutions, and nurses actively participated in all focus groups. Although there are limits to the depth of rapid analysis, we felt this methodology was appropriate given the urgency to share study results and previous work demonstrating consistency between rapid and in‐depth techniques. 24 Multilingual qualitative research is complex and risks loss of meaning during the translation process. To address this, we engaged a large multilingual team including local investigators with bilingual review during data collection and analysis. Finally, focus groups were conducted during a 2‐month period, when providers in different countries were experiencing different stages of the pandemic. However, sufficient time had passed since the beginning of the pandemic to enable meaningful data collection, and inclusion of sites in different regions allowed for comparative analysis and identification of shared experiences.

Much of the existing health systems literature on COVID‐19 has focused on impact of the virus, including studies specifically dedicated to the impact on children with cancer. 5 , 6 This is appropriate for work conducted during an ongoing pandemic, and although our study was structured around resilient health care, the impact on health care teams was palpable. However, as we move into the next phase of this pandemic, one characterized by recovery and emergence, it is imperative to emphasize resilient health care. The impact of this pandemic has been experienced and studied at multiple levels including the patient, provider, and health system, and so too should resilience. Qualitative research conducted during prior pandemics has been useful in illustrating and guiding appropriate response strategies. 25 Our study focused on resilient health care and illustrates strategies for providing high‐quality pediatric cancer care in both high and low‐resource settings. Although individual resiliency 31 , 32 is distinct from that of health care systems, they are intimately related. Further research is necessary to explore the connection between individual coping strategies and the overall resilience of health care as it applies to teams and institutions. In addition, future studies evaluating the effectiveness of specific adaptation and mitigation strategies are warranted. We hope that insights provided by this work are useful to teams globally as they continue to provide high‐quality pediatric cancer care, under the current threat of COVID‐19 and whatever comes next.

Funding Support

This work was supported in part by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

Asya Agulnik received a Global Oncology Young Investigator Award (paid to St. Jude) from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. Carlos Rodriguez‐Galindo has received a grant or contract from the National Cancer Institute. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Dylan E. Graetz: Conceptualization, writing–original draft, and prepared the tables and figures. Carlos Rodriguez‐Galindo: Conceptualization. Asya Agulnik: Conceptualization. Daniel C. Moreira: Conceptualization. Elizabeth Sniderman: Prepared the tables and figures. All authors contributed to data collection, interpretation of the findings, editing of the article, and approval of the final submitted version.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

Graetz DE, Sniderman E, Villegas CA, Kaye EC, Ragab I, Laptsevich A, Maliti B, Naidu G, Huang H, Gassant PY, Nunes Silva L, Arce D, Montoya Vasquez J, Arora RS, Alcasabas AP, Rusmawatiningtyas D, Raza MR, Velasco P, Kambugu J, Vinitsky A, Rodriguez‐Galindo C, Agulnik A, Moreira DC; for the COVIMPACT Study Group . Resilient health care in global pediatric oncology during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Cancer.2022. 10.1002/cncr.34007

See editorial on pages 651‐653, this issue.

The last 2 authors contributed equally to this article.

The members of the COVIMPACT Study Group include the following (all from St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, Tennessee): Nancy S. Bolous, MD; Cyrine E. Haidar, PharmD; Laure Bihannic, PhD; Diana Sa da Bandeira, PhD; Jade Xiaoqing Wang, PhD; Dongfang Li, PhD; Flavia Graca, PhD; Aksana Vasilyeva, PhD; and Harry Lesmana, MD.

References

- 1. Tanne JH, Hayasaki E, Zastrow M, Pulla P, Smith P, Rada AG. Covid‐19: How doctors and healthcare systems are tackling coronavirus worldwide. BMJ. 2020;368:m1090. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Raymond E, Thieblemont C, Alran S, Faivre S. Impact of the COVID‐19 outbreak on the management of patients with cancer. Target Oncol. 2020;15:249‐259. doi: 10.1007/s11523-020-00721-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jazieh AR, Akbulut H, Curigliano G, et al. Impact of the COVID‐19 Pandemic on cancer care: A global collaborative study. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:1428‐1438. doi: 10.1200/go.20.00351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mayor S. COVID‐19: Impact on cancer workforce and delivery of care. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:633. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30240-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vasquez L, Sampor C, Villanueva G, et al. Early impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on pediatric cancer care in Latin America. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:753‐755. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30280-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Saab R, Obeid A, Gachi F, et al. Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic on pediatric oncology care in the Middle East, North Africa, and West Asia region: A report from the Pediatric Oncology East and Mediterranean (POEM) group. Cancer. 2020;126:4235‐4245. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ward ZJ, Yeh JM, Bhakta N, Frazier AL, Atun R. Estimating the total incidence of global childhood cancer: A simulation‐based analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:483‐493. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30909-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rodriguez‐Galindo C, Friedrich P, Morrissey L, Frazier L. Global challenges in pediatric oncology. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2013;25:3‐15. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32835c1cbe [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sterling MR, Tseng E, Poon A, et al. Experiences of home health care workers in New York City during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: A qualitative analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;10021:1453‐1459. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Heath C, Sommerfield A, von Ungern‐Sternberg BS. Resilience strategies to manage psychological distress among healthcare workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic: A narrative review. Anaesthesia. 2020;75:1364‐1371. doi: 10.1111/anae.15180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dhandapani M, Jose S, Cyriac MC. Burnout and resilience among frontline nurses during COVID‐19 pandemic: A cross‐sectional study in the emergency department of a tertiary care center, North India. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2020;24:1081‐1088. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Balay‐odao EM, Alquwez N, Inocian EP, Alotaibi RS. Hospital preparedness, resilience, and psychological burden among clinical nurses in addressing the COVID‐19 crisis in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Front Public Heal. 2021;8:1‐11. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.573932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wosik J, Fudim M, Cameron B, et al. Telehealth transformation: COVID‐19 and the rise of virtual care. J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2020;27:957‐962. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kalaitzaki AE, Tamiolaki A, Rovithis M. The healthcare professionals amidst COVID‐19 pandemic: A perspective of resilience and posttraumatic growth. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;52. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hollnagel E. Delivering Resilient Health Care. Routledge; 2018. doi: 10.4324/9780429469695 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Iflaifel M, Lim RH, Ryan K, Crowley C. Resilient health care: A systematic review of conceptualisations, study methods and factors that develop resilience. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:324. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05208-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32‐item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2007;19:349‐357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, et al. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42:533‐544. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y.Purposeful [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Graetz D, Agulnik A, Ranadive R, et al. Global effect of the COVID‐19 pandemic on pediatric cancer care: A cross‐sectional study. Lancet Child Adolesc Heal. 2021;5:332‐340. doi: 10.1016/s2352-4642(21)00031-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. World Bank Country and Lending Groups . World Bank Data Help Desk. Accessed November 21, 2019. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519‐world‐bank‐country‐and‐lending‐groups

- 21. World Health Organization . Definition of regional groupings. World Health Organization; 2017. Accessed November 19, 2020. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/definition_regions/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 22. Squires A. Methodological challenges in cross‐language qualitative research: A research review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46:277‐287. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. US Department of Veterans Affairs . Qualitative Methods in Rapid Turn‐Around Health Services Research; 2013. Accessed August 2, 2020. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/video_archive.cfm?SessionID=780

- 24. Gale RC, Wu J, Erhardt T, et al. Comparison of rapid vs in‐depth qualitative analytic methods from a process evaluation of academic detailing in the Veterans Health Administration. Implement Sci. 2019;14:11. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0853-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vindrola‐Padros C, Chisnall G, Cooper S, et al. Carrying out rapid qualitative research during a pandemic: Emerging lessons from COVID‐19. Qual Health Res. 2020;30:43‐45. doi: 10.1177/1049732320951526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Averill JB. Matrix analysis as a complementary analytic strategy in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res. 2002;12:855‐866. doi: 10.1177/104973230201200611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gámez AS. Resilience and COVID‐19. Rev Colomb Obstet Ginecol. 2020;71:7‐8. doi: 10.18597/RCOG.3531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Barzilay R, Moore TM, Greenberg DM, et al. Resilience, COVID‐19‐related stress, anxiety and depression during the pandemic in a large population enriched for healthcare providers. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10:291. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-00982-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Clay‐Williams R, Plumb J, Luscombe GM, et al. Improving teamwork and patient outcomes with daily structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds: A multimethod evaluation. J Hosp Med. 2018;13:311‐317. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Etteh CC, Adoga MP, Ogbaga CC. COVID‐19 response in Nigeria: Health system preparedness and lessons for future epidemics in Africa. Ethics Med Public Health. 2020;15:100580. doi: 10.1016/j.jemep.2020.100580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jacelon CS. The trait and process of resilience. J Adv Nurs. 1997;25:123‐129. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025123.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jackson D, Firtko A, Edenborough M. Personal resilience as a strategy for surviving and thriving in the face of workplace adversity: A literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2007;60:1‐9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04412.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material