Abstract

Introduction

Diabetes is the most common cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD). For patients with diabetes and CKD, the underlying cause of their kidney disease is often assumed to be a consequence of their diabetes. Without histopathological confirmation, however, the underlying cause of their disease is unclear. Recent studies have shown that next-generation sequencing (NGS) provides a promising avenue toward uncovering and establishing precise genetic diagnoses in various forms of kidney disease.

Methods

Here, we set out to investigate the genetic basis of disease in non-diabetic kidney disease (NDKD) and diabetic kidney disease (DKD) patients by performing targeted NGS using a custom panel comprised of 345 kidney disease-related genes.

Results

Our analysis identified rare diagnostic variants based on ACMG-AMP guidelines that were consistent with the clinical diagnosis of 19% of the NDKD patients included in this study. Similarly, 22% of DKD patients were found to carry rare pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants in kidney disease-related genes included on our panel. Genetic variants suggestive of NDKD were detected in 3% of the diabetic patients included in this study.

Discussion/Conclusion

Our findings suggest that rare variants in kidney disease-related genes in a diabetic background may play a role in the pathogenesis of DKD and NDKD in patients with diabetes.

Keywords: Targeted sequencing, diabetic kidney disease, genetics

Introduction

Diabetes is the most common cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD) [1]. Continued increase in the world-wide prevalence of diabetes has led to an increase in the global prevalence of diabetic kidney disease (DKD), also known as diabetic nephropathy [2]. For patients with diabetes and CKD, the underlying cause of their kidney disease is often assumed to be a consequence of their diabetes. However, without histopathological evidence, it’s unclear whether such patients have true DKD, non-diabetic kidney disease (NDKD), or concomitant DKD and NDKD.

The only way to truly determine whether CKD in patients with diabetes is a consequence of diabetes is to perform kidney biopsies. Unfortunately, kidney biopsies are not clinically indicated in the diagnosis of DKD. Interestingly, recent investigations of kidney biopsies from patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D) or type 2 diabetes (T2D) and CKD have shown that as many as 30–83% of patients diagnosed with DKD actually had kidney disease attributed to non-diabetic causes [3–5]. Familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), followed by hypertensive nephropathy, acute tubular necrosis, and IgA nephropathy were the most common diagnoses observed in diabetic patients found to have NDKD [6]. Importantly, accurately identifying a patient’s primary cause of CKD is a crucial component of its proper classification, prognosis, and management.

Recent studies conducted primarily in patients with NDKD have shown that next-generation sequencing (NGS) provides a promising avenue toward uncovering and establishing precise genetic diagnoses in various forms of kidney disease [7–12]. The diagnostic yield from these studies range from approximately 10–40% and are highest among patients with congenital or cystic kidney disease. While these studies all show the utility of NGS in providing a molecular diagnosis for patients with heritable forms of kidney disease, whether this technology could also aid in the genetic diagnosis of patients with DKD is unclear. Importantly, improved understanding of the underlying disease process in DKD could have major implications in terms of patient care and monitoring as well as for research studies in this field. To date, no study has examined the distribution of rare variants in known kidney disease-related genes in unrelated patients with DKD. To address this, we performed targeted NGS using a custom gene panel comprised of 345 kidney disease-related genes to interrogate variations between identified NDKD and DKD to identify underlying causes of kidney complications in these patients.

Methods

Study Participants

A total of 222 patients with CKD, including 98 non-diabetic patients (NDKD) and 124 diabetic (DKD) patients, were recruited to the Utah Kidney Study from participating nephrology and dialysis centers in the University of Utah Health Center (UUHSC) network between January 1, 2017 and December 31, 2018. All patients provided detailed medical and family history information through patient questionnaires. All diabetic patients included in this study had a diagnosis of diabetes that predated their CKD diagnosis and reported diabetes as the primary cause of their CKD. Additional medical information, including CKD-related diagnoses, diabetes status, and measures of kidney function, were obtained for all patients included in this study through the UUHSC’s electronical medical records (EMRs). Blood and urine samples were obtained at time of recruitment. Serum creatinine measurements, determined at ARUP Laboratories (Salt Lake City, UT) by standard enzymatic methods, and the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) [13] were used to estimated GFR at the time of recruitment. Genomic DNA was isolated from blood samples using a standard phenol:chloroform DNA extraction protocol.

Kidney Disease-related Gene Panel and Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing

A custom gene panel was designed for simultaneous interrogation of genetic variation across 345 kidney disease-related genes (Supplemental Table 1). Kidney disease-related genes were selected using the Human Genome Database (www.hgmd.com), Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM; www.omim.org) and a comprehensive literature review. Genomic positions of the coding sequence of all 345 genes were obtained from the Consensus Coding Sequence database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/CCDS.CcdsBrowse.cgi, Release 20). The coding region and all exon-intron boundaries of these genes were captured using a custom capture assay (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). The targeted sub-genome spanned a total of 972,494 basepairs. Samples were fragmented using a Covaris S2 ultrasonicator (Covaris, Woburn, MA) and prepared for sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq2500 using a custom DNA library preparation protocol based on the method described by Rohland et al. [14].

Following sequencing, the resulting reads were aligned to the human reference genome (hg19) with Sentieon BWA (Sentieon, Mountain View, CA). Evaluation of the aligned reads and variant calling was performed using the Sentieon DNAseq pipeline. Six samples were excluded from variant calling and downstream analysis due to insufficient read depth. The average read depth across the 216 remaining samples was 309X with 98.1% of bases above 15X coverage. We then inferred family relationships among these patients using ~9,000 informative SNPs from the targeted sequencing data and the Kinship-based INference for Gwas (KING) software [15]. We identified 10 first-degree relative pairs (kinship coefficient > 0.125; Supplemental Table 2). Following removal of one member from each of these relative pairs, the final NDKD and DKD cohorts included 97 and 109 patients, respectively. Clinical characteristics for these patients are presented in Table 1.

Table 1:

Clinical Characteristics of NDKD and DKD Cohorts

| Characteristic | NDKD | DKD |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| N | 97 (47.1) | 109 (52.9) |

| Men | 38 (39.2) | 67 (61.5) |

| Race/Ethnicity*: | ||

| White | 73 (75.3) | 72 (66.1) |

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | 3 (3.1) | 5 (4.6) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 3 (3.1) | 5 (4.6) |

| Black or African American | 2 (2.1) | 2 (1.8) |

| Asian | 3 (3.1) | 1 (0.9) |

| Multiple | 9 (9.3) | 11 (10.1) |

| Unknown | 4 (4.1) | 13 (11.9) |

| 28.0 (22.8, 34.1) | 31.4 (25.7, 36.0) | |

| BMI | ||

| CKD Clinical Diagnosis: | ||

| Congenital Kidney Disease | 5 (5.2) | --- |

| Cystic Kidney Disease | 20 (20.6) | --- |

| Glomerulopathy | 55 (56.7) | --- |

| Tubulointerstitial Disease | 4 (4.1) | --- |

| Diabetic Nephropathy | --- | 109 (100.0) |

| Other | 13 (13.4) | --- |

| 17 (17.5)† | 88 (80.7) | |

| Type 2 Diabetes | ||

| 7.7 (6.5, 8.4) | 7.0 (6.4, 8.2) | |

| HbA1c (%) | ||

| 0 (0.0) | 83 (76.1) | |

| Treatment with Insulin | ||

| Duration of Diabetes Prior to Kidney Disease Diagnosis (years) | --- | 17.0 (10.0, 25.5) |

| 27.0 (10.0, 53.0) | 10.0 (10.0, 37.0) | |

| eGFR at Exam (mL/min/1.73 m2) | ||

| CKD Stage at Exam: | ||

| CKD 1 (eGFR ≥ 90 mL/min/1.73 m2) | 9 (9.3) | 1 (0.9) |

| CKD 2 (eGFR 60–89 mL/min/1.73 m2) | 14 (14.4) | 7 (6.4) |

| CKD 3 (eGFR 30–59 mL/min/1.73 m2) | 22 (22.7) | 25 (22.9) |

| CKD 4 (eGFR 15–29 mL/min/1.73 m2) | 11 (11.3) | 3 (2.8) |

| CKD 5 (eGFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2) | 41 (42.3) | 73 (67.0) |

| First Degree Relative with Kidney Disease | 37 (38.1) | 37 (33.9) |

Data are presented as n (%) or median (1st, 3rd quartile). HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; CKD, chronic kidney disease; BMI, body mass index; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Self-reported race/ethnicity.

17 NDKD patients were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes after developing CKD.

Variant Analysis

The resulting variant call format (VCF) file was annotated using ANNOVAR [16] and filtered based on variant function (nonsynonymous, stop gain/loss, splicing, frameshift insertion/deletion, and in-frame insertion/deletion variants) and minor allele frequencies (MAF; < 0.1% global population MAF) in the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) [17], a population-level database of genomic variant frequencies derived from large-scale exome and genome sequencing data. The clinical significance of these candidate rare, functional variants was interpreted using InterVar [18] following the 2015 American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology (ACMG-AMP) standards and guidelines [19]. Variants classified as ‘pathogenic’ or ‘likely pathogenic’ according to these guidelines and that followed the inheritance pattern (dominant or recessive) associated with disease were considered to be diagnostic variants causal of the patient’s nephropathy. Although phasing information was not available, we considered individuals with at least 2 rare (MAF < 0.1%) heterozygous genotypes in a single gene to be putative compound heterozygous carriers under a recessive model. In addition, multiple computational prediction algorithms, including SIFT [20], Polyphen2 (Polyphen2_HDIV and Polyphen2_HVAR) [21], MutationTaster [22], M-CAP [23] and LRT [24], were utilized to aid in the interpretation of nonsynonymous variants classified as ‘variants of unknown significance’ (VUSs) by the ACMG-AMP guidelines. In line with these guidelines, supportive evidence of pathogenicity was considered for VUSs predicted to be damaging by at least 5 of these 6 prediction methods.

Additionally, we performed copy-number variant (CNV) analysis using Atlas-CNV, a method for detecting and prioritizing high-confidence CNVs in targeted NGS data [25]. As recommended by the developers of this program, CNVs with a log2 score −0.6 (losses) and 0.4 (gains), corresponding to confidence scores (C-scores) of −7.49 and 5.01, respectively, were called. All prioritized CNVs were visualized using the Integrative Genomics Viewer software program [26] and inspected manually.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous data are presented as the median (1st, 3rd quartile). Dichotomous data are shown as n (percentage). Differences between the NDKD and DKD groups were assessed using χ2 tests and Fisher’s Exact Test (or Test for Trend) for dichotomous variables and unpaired t tests for continuous data comparisons using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Gene-based rare variant association burden testing of identified variants using the SNP-set (Sequence) Kernel Association Test (SKAT) [27]. Two-tailed p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Study Cohorts

Two hundred and six patients with CKD, including 97 NDKD patients and 109 DKD patients, from the Utah Kidney Study were successfully sequenced using a custom gene panel (Table 1). The median ages of NDKD and DKD patients included in this study were 47.9 and 62.0, respectively. The majority of patients in our NDKD cohort (56.7%) had a clinical diagnosis of glomerulopathy, 20.6% had cystic kidney disease, 5.2% had congenital kidney disease, and 4.1% had tubulointerstitial disease. Approximately 13% of these patients had other forms of NDKD. All diabetic patients included in this study had a diagnosis of diabetes that predated their CKD diagnosis and had diabetes listed as the primary cause of their CKD in their EMRs. Among these patients, 80.7% had a diagnosis of T2D and 76.1% were being treated with insulin at the time of their enrollment to the Utah Kidney Study. Thirty-eight percent of NDKD patients and nearly 34% of DKD patients reported that they had a first degree relative with kidney disease.

Targeted NGS of Kidney Disease-related Genes

Using our targeted sequencing panel, we identified 1,259 rare, functional variants (i.e., nonsynonymous, stop gain/loss, splicing, frameshift insertion/deletion, and in-frame insertion/deletion variants) in 345 kidney disease-related genes (Supplemental Table 1) among the 206 patients included in this study (Supplemental Table 3 and Supplemental Table 4). Of these variants, 63 (5.0%) were classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic using the ACMG-AMP guidelines; the remaining variants were classified as ‘variants of unknown significance’ (VUSs) (n=1,024; 81.3%) or benign/likely benign variants (n=172; 13.7%).

Diagnostic Variants in Kidney Disease-related Genes in NDKD Patients

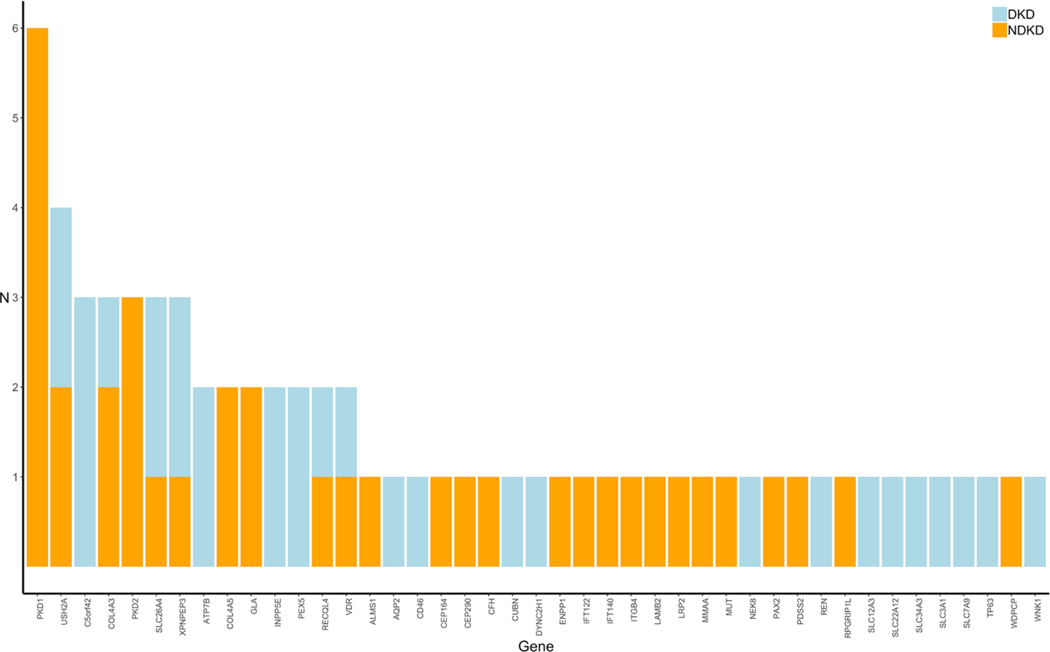

In total, pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants were identified in 35 of the 97 NDKD patients (36%) included in our study (Supplemental Table 5). We identified 17 diagnostic variants (i.e., pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants consistent with the inheritance pattern associated with the patient’s clinical diagnosis), including 13 novel variants (76.5%) not present in the gnomAD database, in 18 NDKD patients (18.6%) included in our study (Table 2A and Table 3). These pathogenic or likely pathogenic single nucleotide and insertion/deletion variants were detected in 7 genes (CFH, COL4A3, COL4A5, GLA, PAX2, PDK1, and PDK2). PKD1 and PKD2 were the genes with the highest burden of candidate diagnostic variants (Fig. 1).

Table 2:

Summary of Diagnostic Variants Identified in NDKD Patients and Pathogenic/Likely Pathogenic Variants Identified in DKD Patients

| Table 2A. Diagnostic Variants Identified in NDKD Patients | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Patient | Clinical Diagnosis | CKD Stage at Exam | Gene | Consensus Transcript | Variant | dbSNP RefSNP ID | ACMG-AMP Classification | gnomAD MAF |

|

| ||||||||

| NDKD-1 | Alport Syndrome | 3 | COL4A5 | NM_000495 | p.G1060X | rs104886217 | Pathogenic | ---- |

| NDKD-2 | Alport Syndrome | 1 | COL4A5 | NM_000495 | p.L1649R | rs104886303 | Likely pathogenic | ---- |

| NDKD-3 | Fabry Disease | 4 | GLA | NM_000169 | p.N215S | rs28935197 | Likely pathogenic | 5.5×10−6 |

| NDKD-4 | IgA Nephropathy | 5 | CFH | NM_000186 | p.S212Sfs*13 | Likely pathogenic | ---- | |

| NDKD-5 | Polycystic Kidney Disease | 5 | PKD1 | NM_000296 | p.Y528X | Likely pathogenic | ---- | |

| NDKD-6 | Polycystic Kidney Disease | 1 | PKD1 | NM_000296 | p.C933Wfs*167 | Likely pathogenic | ---- | |

| NDKD-7 | Polycystic Kidney Disease | 5 | PKD1 | NM_000296 | p.Q1975X | Pathogenic | ---- | |

| NDKD-8 | Polycystic Kidney Disease | 3 | PKD1 | NM_000296 | p.E2864X | Likely pathogenic | ---- | |

| NDKD-9 | Polycystic Kidney Disease | 4 | PKD1 | NM_000296 | p.W3841X | Pathogenic | ---- | |

| NDKD-10 | Polycystic Kidney Disease | 4 | PKD1 | NM_000296 | p.E4077Tfs*117 | Likely pathogenic | ---- | |

| NDKD-11 | Polycystic Kidney Disease | 2 | PKD2 | NM_000297 | c.844–2A>G | Pathogenic | ---- | |

| NDKD-12 | Polycystic Kidney Disease | 3 | PKD2 | NM_000297 | p.N720Kfs*5 | rs757757289 | Likely pathogenic | 7.9×10−6 |

| NDKD-13 | Polycystic Kidney Disease | 4 | PKD2 | NM_000297 | p.Y762X | Likely pathogenic | ---- | |

| NDKD-14 | Renal Hypoplasia | 5 | PAX2 | NM_000278 | p.P161Pfs*113 | Likely pathogenic | ---- | |

|

| ||||||||

| Table 2B. Pathogenic/Likely Pathogenic Variants Identified in DKD Patients | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Patient | Diabetes Type | CKD Stage at Exam | Gene | Consensus Transcript | Variant | dbSNP RefSNP ID | ACMG-AMP Classification | gnomAD MAF |

|

| ||||||||

| DKD-1 | T1D | 2 | CUBN | NM_001081 | P1971Pfs*11 | rs765301342 | Likely pathogenic | 6.5×10−5 |

| DKD-2 | T1D | 2 | INPP5E | NM_001318502 | R378S | rs121918130 | Likely pathogenic | 4.2×10−6 |

| DKD-3 | T1D | 5 | SLC22A12 | NM_001276327 | E321K | rs139140123 | Likely pathogenic | 6.5×10−5 |

| XPNPEP3 | NM_022098 | R415Q | rs79385822 | Likely pathogenic | 7.2×10−4 | |||

| DKD-4 | T1D | 1 | WNK1 | NM_213655 | V724Dfs*47 | Likely pathogenic | ---- | |

| DKD-5 | T2D | 5 | AQP2 | NM_000486 | N220T | rs771414160 | Likely pathogenic | 6.5×10−5 |

| RECQL4 | NM_004260 | H831Rfs*52 | rs752729755 | Pathogenic | 3.2×10−5 | |||

| DKD-6 | T2D | 5 | ATP7B | NM_001005918 | A811V | rs371840514 | Likely pathogenic | 6.0×10−5 |

| DKD-7 | T2D | 5 | ATP7B | NM_001330579 | W695X | rs137853283 | Pathogenic | 4.2×10−5 |

| DKD-8 | T2D | 5 | C5orf42 | NM_023073 | I165Yfs*17 | rs606231259 | Pathogenic | 6.0×10−5 |

| DKD-9 | T2D | 5 | C5orf42 | NM_023073 | V938Efs*27 | rs1169195782 | Likely pathogenic | ---- |

| DKD-10 | T2D | 5 | C5orf42 | NM_023073 | c.8300–1G>C | rs151279194 | Pathogenic | 5.0×10−4 |

| DKD-11 | T2D | 5 | CD46 | NM_002389 | c.286+1G>C | Pathogenic | ---- | |

| SLC26A4 | NM_000441 | S408Sfs*58 | Likely pathogenic | ---- | ||||

| DKD-12 | T2D | 5 | COL4A3 | NM_000091 | R1661C | rs201697532 | Likely pathogenic | 3.6×10−4 |

| SLC34A3 | NM_001177316 | c.1335+2T>A | rs752222200 | Pathogenic | 4.1×10−5 | |||

| DKD-13 | T2D | 5 | DYNC2H1 | NM_001080463 | W179X | Pathogenic | ---- | |

| DKD-14 | T2D | 5 | INPP5E | NM_001318502 | R514Gfs*55 | Likely pathogenic | ---- | |

| DKD-15 | T2D | 5 | NEK8 | NM_178170 | G190Gfs*22 | Likely pathogenic | ---- | |

| T2D | PEX5 | NM_001300789 | P16Rfs*3 | rs775604296 | Likely pathogenic | 1.3×10−4 | ||

| DKD-16 | T2D | 5 | PEX5 | NM_001300789 | P16Rfs*3 | rs775604296 | Likely pathogenic | 1.3×10−4 |

| T2D | SLC12A3 | NM_000339 | R642C | rs200697179 | Likely pathogenic | 1.2×10−4 | ||

| DKD-17 | T2D | 3 | REN | NM_000537 | R49X | rs121917741 | Pathogenic | 5.4×10−5 |

| DKD-18 | T2D | 3 | SLC3A1 | NM_000341 | L285X | rs761094083 | Pathogenic | 3.9×10−6 |

| DKD-19 | T2D | 3 | SLC7A9 | NM_001126335 | K205fs | rs745319034 | Pathogenic | 1.0×10−4 |

| DKD-20 | T2D | 5 | SLC26A4 | NM_000441 | S408Sfs*58 | Likely pathogenic | ---- | |

| DKD-21 | T2D | 3 | TP63 | NM_001329146 | T195M | rs199807776 | Likely pathogenic | 8.1×10−5 |

| DKD-22 | T2D | 5 | USH2A | NM_206933 | I4803Tfs*16 | Likely pathogenic | ---- | |

| DKD-23 | T2D | 3 | VDR | NM_000376 | R74H | Likely pathogenic | ---- | |

| DKD-24 | T2D | 5 | XPNPEP3 | NM_022098 | P103S | rs73885709 | Likely pathogenic | 3.2×10−5 |

Table 3:

Re-classification of Clinical Diagnoses of NDKD and DKD Patients Based on Identified Diagnostic Variants

| Patient | Clinical Diagnosis | Gene | CKD Stage at Exam | Consensus Transcript | Variant (Het./Homo.) | gnomAD MAF | ACMG-AMP Classification | Associated Disease (Inheritance) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| NDKD-15 | ANCA Vasculitis | NPHP1 | 4 | NM_000272 | Gene Deletion (Homo.) | --- | --- | Familial Juvenile Nephronophthisis (Recessive) |

| NDKD-16 | Polycystic Kidney Disease | COL4A3 | 3 | NM_000091 | p.R1661C (Het.) | 3.6×10−4 | Likely pathogenic | TBMN/FSGS/Alport Syndrome (Dominant) |

| NDKD-17 | Congenital Nephrotic Syndrome | COL4A3 | 5 | NM_000091 | p.R1661C (Het.) | 3.6×10−4 | Likely pathogenic | TBMN/FSGS/Alport Syndrome (Dominant) |

| NDKD-18 | Congenital Kidney Disease | GLA | 5 | NM_000169 | p.A143T (Het.) | 5.1×10−4 | Likely pathogenic | Fabry Disease (X-linked) |

| NDKD-19 | IgA Nephropathy | IFT122 | 2 | NM_0529990 | p.R166W (Het.) | 3.3×10−4 | Uncertain Significance* Pathogenic | Cystic Renal Disease (Recessive) |

| p.R779X (Het.) | --- | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| DKD-5 | DKD | AQP2 | 5 | NM_000486 | p.N220T (Het.) | 6.5×10−5 | Likely pathogenic | Nephrogenic Diabetes Insipidus (Dominant) |

| DKD-12 | DKD | COL4A3 | 5 | NM_000091 | p.R1661C (Het.) | 3.6×10−4 | Likely pathogenic | TBMN/FSGS/ Alport Syndrome (Dominant) |

| DKD-17 | DKD | REN | 3 | NM_000537 | p.R49X (Het.) | 5.4×10−5 | Pathogenic | ADTKD (Dominant) |

TBMN, thin basement membrane nephropathy; FSGS, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; ADTKD, autosomal dominant tubulointerstitial kidney disease

Predicted to be damaging by at least 5 of 6 computational prediction methods, considered to have supportive evidence of pathogenicity.

Fig. 1. Distribution of Rare Pathogenic or Likely Pathogenic Variants in NDKD and DKD Patients. The distribution of rare (MAF<0.1%) pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants identified in NDKD (blue) and DKD (orange) patients. NDKD, non-diabetic kidney disease; DKD, diabetic kidney disease.

The diagnostic yield was highest (9 of 20; 45.0%) in patients diagnosed with cystic kidney disease. A total of 9 patients carried diagnostic variants in PKD1 or PKD2, genes known to be causal of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD); 8 of the identified PKD1/PKD2 variants were absent from population data. Five additional patients with cystic kidney disease had novel VUSs in PKD1 or PKD2 that are predicted to be damaging using computational prediction tools (Supplemental Table 6). Although these variants do not meet strict ACMG-AMP criteria for classifying these as clinically significant, they do have supportive evidence of pathogenicity. Further examination of these variants, including segregation analysis and functional assays, together with this computational support, could further increase the diagnostic yield of genetic screening in the cystic kidney disease patients included in this study.

Additionally, we identified APOL1 risk alleles (G1: p.Ser342Gly and p.Ile384Met and/or G2: p.Asn388_Try389del) in 2 African American NDKD patients with clinical diagnoses of glomerulonephritis (G1/G1 genotype) and hypertensive nephropathy (G1/G2 genotype), respectively [28, 29].

Re-Classification of Kidney Disease Diagnoses in NDKD Patients Based on Genetic Diagnoses

Sequencing of kidney disease-related genes in 4 NDKD patients (4.1%) allowed us to identify variants that are consistent with genetic diagnoses that differed from their documented clinical diagnoses (Table 3). Among these patients, we identified a large homozygous deletion of NPHP1 in a patient diagnosed with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated (ANCA) vasculitis following a kidney biopsy (Supplemental Figure 1). Interestingly, this well-characterized deletion is frequently seen in familial juvenile nephronophthisis (OMIM 256100), accounting for approximately 80% of patients with this disease [30, 31], suggesting that this individual may have two concurrent kidney disorders (i.e., familial juvenile nephronophthisis and ANCA vasculitis). Similarly, 1 patient diagnosed with PKD was found to have a diagnostic variant in COL4A3 (p.R1661C). This same variant, although rare in the population (MAF = 3.6×10−4), was observed in 2 additional patients in our study (a patient with congenital nephrotic syndrome and a patient diagnosed with DKD) and has previously been observed in patients with FSGS [32] and autosomal recessive Alport syndrome (MIM 104200) [33]. For each of these patients, their genetic diagnosis is more consistent with glomerular disease, including thin basement membrane nephropathy (TBMN), FSGS, or Alport syndrome.

Similarly, we identified a rare variant in GLA (p.A143T) in a patient clinically diagnosed with congenital kidney disease; this variant has previously been reported to be pathogenic in patients with Fabry disease (MIM 301500) [34]. Lastly, 1 patient diagnosed with IgA nephropathy was found to carry rare compound heterozygous variants in IFT122 (p.R166W and p.R779X), which are known to contribute to ciliary dysfunction and cystic kidney disease [35].

Rare Variants in Kidney Disease-related Genes in Patients with DKD

Using the ACMG-AMP guidelines to classify variants in these same kidney disease-related genes, pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants were identified in 22.0% (24 of 109) of the DKD patients included in this study (Table 2B). The proportion of variants was similar among both T1D and T2D patients (19% versus 23%, respectively; p-value > 0.05). Although not statistically significant, nearly one-third of DKD patients (27.0%) found to carry a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant reported a family history of kidney disease, compared to only 19.4% of DKD patients without a known family history of kidney disease. In total, 29 pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants were identified in 23 genes in these patients (Fig. 1). C5orf42 (also called CPLANE1 and JBTS17) had the highest burden of pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants among these patients.

Interestingly, 9 DKD patients were found to harbor rare pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in known ciliopathy genes, including DYNC2H1, INPP5E, XPNPEP3, NEK8, and C5orf42. Six of the variants identified in these genes are putative loss-of-function (pLOF) variants that either affect splice sites or introduce premature stop codons (i.e., nonsense variants or frameshift insertion/deletions). Among these patients, 1 had biallelic variants in C5orf42 (p.I165Yfs*17, a pathogenic variant, and p.S123F, a variant with supportive evidence of pathogenicity predicted to be damaging by at least 5 of 6 computational prediction methods), suggesting that this patient is likely a compound heterozygous carrier of damaging variants in this gene.

Rare Diagnostic NDKD Variants Identified in a Subset of DKD Patients

Three DKD patients (2.8%) were found to carry rare variants suggestive that the underlying cause of their kidney disease may not be a consequence of their diabetes (Table 3). A patient with CKD attributed to T2D was found to have a rare diagnostic variant in AQP2 (p.N220T); a gene that causes an autosomal dominant form of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, a condition characterized by severe polyuria [36]. Similarly, a pathogenic REN variant (p.R49X) was identified in a second patient with T2D. Pathogenic variants in REN are associated with autosomal dominant tubulointerstitial kidney disease (ADTKD) [37, 38]. As both of these patients also have a history of diabetic retinopathy, it is possible that they have concomitant DKD and NDKD. Lastly, 1 T2D patient was found to carry a diagnostic variant in COL4A3 (p.R1661C). As mentioned above, this variant has been observed in patients with FSGS [32] and autosomal recessive Alport syndrome [33]. In contrast to the DKD patients with AQP2 and REN variants, despite more than 35 years of diabetes, this patient does not have documented evidence of retinopathy or neuropathy, further suggesting that this patient likely has NDKD.

Genetic Burden of Rare Variants in Kidney Disease-related Genes in NDKD and DKD Patients

We performed gene-based burden association tests to compare the rate of rare variants between NDKD and DKD patients aggregated within each gene. As expected, the most significant enrichment of rare pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants was observed in PKD1 among NDKD patients (p-value = 0.008; Supplemental Table 7). Similarly, although not statistically significant (p-value >0.05), enrichment of rare pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants was also observed in PKD2 among NDKD patients. Conversely, an excess of rare variants in C5orf42 was seen in DKD patients.

As variants classified as VUSs using ACMG-AMP guideline cannot be ruled out as benign, and likely include pathogenic variants, we expanded our gene-based burden analyses to include rare variants with supportive evidence of pathogenicity based on computational prediction methods. As seen in our analysis of rare pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants alone, we observed an excess burden of rare variants in both PKD1 (p-value = 0.01) and PKD2 (p-value = 0.04) in NDKD patients. Rare variants in COL4A5 (p-value = 0.008) were also significantly enriched in NDKD compared to DKD patients. Interestingly, in addition to strengthening the association seen in DKD patients with rare variants in C5orf42 (p-value = 0.04), this analysis detected enrichment of rare variants in DKD patients in both ACE (p-value = 0.008) and NEK8 (p-value = 0.04).

Discussion/Conclusion

The goal of this study was to investigate the utility of NGS in understanding the molecular basis of kidney disease in patients with and without diabetes. While genetic testing has been shown to aid in providing more accurate diagnoses in patients with heritable forms of kidney disease, including ADPKD, Alport Syndrome, and Fabry Disease, its application to patients with DKD, and its utility in identifying unsuspected kidney disease in patients diagnosed with DKD, has been limited [39, 40]. To further investigate this, we successfully performed targeted NGS in a total of 206 patients with CKD, including 97 NDKD and 109 DKD patients, using a custom gene panel comprised of 345 kidney disease-related genes. Our analysis identified diagnostic variants that were consistent with the clinical diagnosis of approximately 19% of the NDKD patients included in this study. While one-third of NDKD patients were found to carry pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants, as classified by the ACMG-AMP guidelines, more than 20% of the DKD patients included in this study carried similarly classified variants (i.e., pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants) in these same kidney disease-related genes. We detected genetic variants suggestive of NDKD in approximately 3% of the diabetic patients included in this study.

Several of the genes found to carry pathogenic variants in DKD patients, including CUBN, PEX5, VDR, and COL4A3, have previously been implicated in diabetic nephropathy [41–44]. Coding variants in CUBN, a gene expressed in the apical brush border of proximal tubule cells [45], are known to be associated with albuminuria [43, 46]. A recent exome-wide association study identified a rare coding variant in CUBN that was independent of previously identified common variants in this gene and that had greater than a 3.5-fold stronger effect in patients with diabetes relative to those without diabetes [43]. Similarly, a multi-omics systems biology analysis by Saito et al. found that PEX5, a peroxisomal biogenesis marker, is associated with diabetic nephropathy via peroxisomal dysfunction and plays a role in the down-regulation of peroxisome-related metabolites [42]. More recently, as part of the largest genome-wide association study on DKD to date, the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation’s Diabetic Nephropathy Collaborative Research Initiative identified 16 genome-wide significance loci associated with DKD; interestingly, 2 of the top signals from this study are in known kidney disease-related genes (COL4A3 and BMP7) [44]. COL4A3 encodes a major structural component of the glomerular basement membrane and is associated with heritable nephropathies, including Alport syndrome, FSGS, and TBMN. The rare COL4A3 variant identified in 3 patients included in our study (1 DKD and 2 NDKD patients) has previously been observed in a family with biopsy proven FSGS [32], suggesting that this variant may contribute to kidney disease independent of diabetes status.

In the presence of hyperglycemia, defects in cilia structure or function cause structural and functional alterations in the kidney, including podocyte effacement, interstitial inflammation, and proteinuria [47]. Interestingly, 25% of DKD patients positive for pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants were found to carry rare variants in known ciliopathy-associated genes, including 3 patients found to harbor rare pLOF variants in C5orf42, a gene that is associated with rare autosomal recessive ciliopathies characterized by cystic kidney disease [48–50]. Similarly, we identified rare, likely pathogenic variants in XPNPEP3 in 2 DKD patients with ESRD; defects in XPNPEP3 cause nephronophthisis-like nephropathy, a cystic kidney disease that leads to ESRD [51]. Taken together, these data suggest that variants in kidney disease-related genes in the context of diabetic pathophysiology play a role in the pathogenesis of kidney disease in patients with diabetes.

Previous studies examining the diagnostic utility of genetic testing in CKD found the overall diagnostic yield to be approximately 10% [7–12, 52]. Among patients with a clinical diagnosis of diabetic nephropathy, however, this was much lower (1.6%) [11]. In contrast, we found that as many as 22% of DKD patients included in our study carry pathogenic or likely pathogenic in the kidney disease-related genes included on our gene panel. While the reason behind this discrepancy is unclear, it should be noted that nearly 70% of those found to have variants in our study had ESRD, suggesting that these variants may predispose diabetic patients to more severe kidney disease.

In line with data from previous studies, our study highlights the effectiveness of genetic testing in identifying the underlying molecular cause of disease in patients with various forms of NDKD. In addition to assigning genetic diagnoses that corroborated several NDKD patients’ clinical diagnoses, in a subset of patients, we were able to identify rare variants that suggested re-evaluation of their diagnoses is warranted. For these patients, genetic analysis may have aided in detecting unrecognized clinical symptoms and better informed the management of their care.

Our study has limitations that should be acknowledged. First, our study included only 206 patients. Despite its modest samples size, it is the first to comprehensively investigate the burden of rare variants in kidney disease-related genes in DKD. Not only did we find that 22% of these DKD patients carry rare variants in these genes but, for some, we identified a genetic diagnosis suggestive that their kidney disease was likely not a consequence of their diabetes and, thereby, highlighting the value of genetic screening in uncovering precise molecular diagnoses. Second, although we were able to detect both coding variants and structural rearrangements using targeted sequencing, variants in non-coding regions, that potentially impact RNA expression and/or processing (e.g., those that affect transcriptional repression, exon skipping, and intron inclusion), were not evaluated. As our custom capture assay was restricted to the coding region and exon-intron boundaries of the genes include on our panel, any variants outside of these regions, including those in the promoter regions and other noncoding or regulatory regions, could not be detected using this assay. Third, in order to increase specificity, we adhered to the ACMG-AMP standards and guidelines for variant interpretation and, as such, many of the variants identified in our study were labeled as VUSs and not correlated with clinical phenotypes. As VUSs cannot fully be ruled out as benign, this may have impacted the sensitivity of our study. Computational prediction algorithms coupled with support from functional studies could help to better understand the pathogenicity of VUSs and prioritize these for further study.

Our goal was to leverage NGS technology to better understand the genetic underpinnings of kidney disease in patients with diabetes. Although most diabetic patients included in our study were not found to have pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants in kidney disease-related genes, a nontrivial proportion (more than 20%) were found to carry variants that we suspect contribute to their disease. Our findings suggest that rare variants in genes not previously linked to DKD (e.g., ciliopathy genes) may contribute to DKD susceptibility and that genetic screening in patients with DKD can help provide a molecular diagnosis that could translate to improved precision diagnostics and aid in the prognosis and long-term management of their kidney disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge grant support from the National Kidney Foundation (MGP) and the Larry H. and Gail Miller Family Foundation Diabetes Initiative (MGP).

Funding Sources

This study was funded in part by the National Kidney Foundation of Utah and Idaho (MGP) and the Larry H. and Gail Miller Family Foundation Diabetes Initiative (MGP).

Footnotes

Statement of Ethics

This study was approved by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board (IRB_00098113 and IRB_00109765). All participants provided written and informed consent prior to their inclusion in this study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.U.S. Renal Data System. USRDS 2018 Annual Data Report: Atlas of End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. In: NIH, editor. Bethesda: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anders HJ, Huber TB, Isermann B, Schiffer M. CKD in diabetes: diabetic kidney disease versus nondiabetic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14(6):361–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haider DG, Peric S, Friedl A, Fuhrmann V, Wolzt M, Horl WH, et al. Kidney biopsy in patients with diabetes mellitus. Clin Nephrol. 2011;76(3):180–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma SG, Bomback AS, Radhakrishnan J, Herlitz LC, Stokes MB, Markowitz GS, et al. The modern spectrum of renal biopsy findings in patients with diabetes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(10):1718–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhuo L, Ren W, Li W, Zou G, Lu J. Evaluation of renal biopsies in type 2 diabetic patients with kidney disease: a clinicopathological study of 216 cases. Int Urol Nephrol. 2013;45(1):173–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman NS, Canetta PA, Bomback AS. Glomerular Diseases in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus: An Underappreciated Epidemic. Kidney 360. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mallett AJ, McCarthy HJ, Ho G, Holman K, Farnsworth E, Patel C, et al. Massively parallel sequencing and targeted exomes in familial kidney disease can diagnose underlying genetic disorders. Kidney Int. 2017;92(6):1493–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bullich G, Domingo-Gallego A, Vargas I, Ruiz P, Lorente-Grandoso L, Furlano M, et al. A kidney-disease gene panel allows a comprehensive genetic diagnosis of cystic and glomerular inherited kidney diseases. Kidney Int. 2018;94(2):363–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lata S, Marasa M, Li Y, Fasel DA, Groopman E, Jobanputra V, et al. Whole-Exome Sequencing in Adults With Chronic Kidney Disease: A Pilot Study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(2):100–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Connaughton DM, Kennedy C, Shril S, Mann N, Murray SL, Williams PA, et al. Monogenic causes of chronic kidney disease in adults. Kidney Int. 2019;95(4):914–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Groopman EE, Marasa M, Cameron-Christie S, Petrovski S, Aggarwal VS, Milo-Rasouly H, et al. Diagnostic Utility of Exome Sequencing for Kidney Disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(2):142–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang M, Chun J, Genovese G, Knob AU, Benjamin A, Wilkins MS, et al. Contributions of Rare Gene Variants to Familial and Sporadic FSGS. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30(9):1625–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rohland N, Reich D. Cost-effective, high-throughput DNA sequencing libraries for multiplexed target capture. Genome Res. 2012;22(5):939–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manichaikul A, Mychaleckyj JC, Rich SS, Daly K, Sale M, Chen WM. Robust relationship inference in genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(22):2867–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(16):e164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karczewski KJ, Francioli LC, Tiao G, Cummings BB, Alföldi J, Wang Q, et al. Variation across 141,456 human exomes and genomes reveals the spectrum of loss-of-function intolerance across human protein-coding genes. bioRxiv. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Q, Wang K. InterVar: Clinical Interpretation of Genetic Variants by the 2015 ACMG-AMP Guidelines. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;100(2):267–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sim NL, Kumar P, Hu J, Henikoff S, Schneider G, Ng PC. SIFT web server: predicting effects of amino acid substitutions on proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Web Server issue):W452–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7(4):248–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwarz JM, Rodelsperger C, Schuelke M, Seelow D. MutationTaster evaluates disease-causing potential of sequence alterations. Nat Methods. 2010;7(8):575–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jagadeesh KA, Wenger AM, Berger MJ, Guturu H, Stenson PD, Cooper DN, et al. M-CAP eliminates a majority of variants of uncertain significance in clinical exomes at high sensitivity. Nat Genet. 2016;48(12):1581–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chun S, Fay JC. Identification of deleterious mutations within three human genomes. Genome Res. 2009;19(9):1553–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chiang T, Liu X, Wu TJ, Hu J, Sedlazeck FJ, White S, et al. Atlas-CNV: a validated approach to call single-exon CNVs in the eMERGESeq gene panel. Genet Med. 2019;21(9):2135–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdottir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(1):24–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee S, Emond MJ, Bamshad MJ, Barnes KC, Rieder MJ, Nickerson DA, et al. Optimal unified approach for rare-variant association testing with application to small-sample case-control whole-exome sequencing studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91(2):224–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Genovese G, Friedman DJ, Ross MD, Lecordier L, Uzureau P, Freedman BI, et al. Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science. 2010;329(5993):841–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tzur S, Rosset S, Shemer R, Yudkovsky G, Selig S, Tarekegn A, et al. Missense mutations in the APOL1 gene are highly associated with end stage kidney disease risk previously attributed to the MYH9 gene. Hum Genet. 2010;128(3):345–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Konrad M, Saunier S, Heidet L, Silbermann F, Benessy F, Calado J, et al. Large homozygous deletions of the 2q13 region are a major cause of juvenile nephronophthisis. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5(3):367–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saunier S, Calado J, Benessy F, Silbermann F, Heilig R, Weissenbach J, et al. Characterization of the NPHP1 locus: mutational mechanism involved in deletions in familial juvenile nephronophthisis. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66(3):778–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malone AF, Phelan PJ, Hall G, Cetincelik U, Homstad A, Alonso AS, et al. Rare hereditary COL4A3/COL4A4 variants may be mistaken for familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2014;86(6):1253–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heidet L, Arrondel C, Forestier L, Cohen-Solal L, Mollet G, Gutierrez B, et al. Structure of the human type IV collagen gene COL4A3 and mutations in autosomal Alport syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12(1):97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Terryn W, Vanholder R, Hemelsoet D, Leroy BP, Van Biesen W, De Schoenmakere G, et al. Questioning the Pathogenic Role of the GLA p.Ala143Thr “Mutation” in Fabry Disease: Implications for Screening Studies and ERT. JIMD Rep. 2013;8:101–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takahara M, Katoh Y, Nakamura K, Hirano T, Sugawa M, Tsurumi Y, et al. Ciliopathy-associated mutations of IFT122 impair ciliary protein trafficking but not ciliogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2018;27(3):516–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loonen AJ, Knoers NV, van Os CH, Deen PM. Aquaporin 2 mutations in nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Semin Nephrol. 2008;28(3):252–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zivna M, Hulkova H, Matignon M, Hodanova K, Vylet’al P, Kalbacova M, et al. Dominant renin gene mutations associated with early-onset hyperuricemia, anemia, and chronic kidney failure. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85(2):204–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schaeffer C, Izzi C, Vettori A, Pasqualetto E, Cittaro D, Lazarevic D, et al. Autosomal Dominant Tubulointerstitial Kidney Disease with Adult Onset due to a Novel Renin Mutation Mapping in the Mature Protein. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):11601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guan M, Ma J, Keaton JM, Dimitrov L, Mudgal P, Stromberg M, et al. Association of kidney structure-related gene variants with type 2 diabetes-attributed end-stage kidney disease in African Americans. Hum Genet. 2016;135(11):1251–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guan M, Keaton JM, Dimitrov L, Hicks PJ, Xu J, Palmer ND, et al. An Exome-wide Association Study for Type 2 Diabetes-Attributed End-Stage Kidney Disease in African Americans. Kidney Int Rep. 2018;3(4):867–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanchez-Nino MD, Bozic M, Cordoba-Lanus E, Valcheva P, Gracia O, Ibarz M, et al. Beyond proteinuria: VDR activation reduces renal inflammation in experimental diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;302(6):F647–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saito R, Rocanin-Arjo A, You YH, Darshi M, Van Espen B, Miyamoto S, et al. Systems biology analysis reveals role of MDM2 in diabetic nephropathy. JCI Insight. 2016;1(17):e87877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ahluwalia TS, Schulz CA, Waage J, Skaaby T, Sandholm N, van Zuydam N, et al. A novel rare CUBN variant and three additional genes identified in Europeans with and without diabetes: results from an exome-wide association study of albuminuria. Diabetologia. 2019;62(2):292–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salem RM, Todd JN, Sandholm N, Cole JB, Chen WM, Andrews D, et al. Genome-Wide Association Study of Diabetic Kidney Disease Highlights Biology Involved in Glomerular Basement Membrane Collagen. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30(10):2000–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amsellem S, Gburek J, Hamard G, Nielsen R, Willnow TE, Devuyst O, et al. Cubilin is essential for albumin reabsorption in the renal proximal tubule. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(11):1859–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boger CA, Chen MH, Tin A, Olden M, Kottgen A, de Boer IH, et al. CUBN is a gene locus for albuminuria. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(3):555–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sas KM, Yin H, Fitzgibbon WR, Baicu CF, Zile MR, Steele SL, et al. Hyperglycemia in the absence of cilia accelerates cystogenesis and induces renal damage. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2015;309(1):F79–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Romani M, Mancini F, Micalizzi A, Poretti A, Miccinilli E, Accorsi P, et al. Oral-facial-digital syndrome type VI: is C5orf42 really the major gene? Hum Genet. 2015;134(1):123–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wentzensen IM, Johnston JJ, Keppler-Noreuil K, Acrich K, David K, Johnson KD, et al. Exome sequencing identifies novel mutations in C5orf42 in patients with Joubert syndrome with oral-facial-digital anomalies. Hum Genome Var. 2015;2:15045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fleming LR, Doherty DA, Parisi MA, Glass IA, Bryant J, Fischer R, et al. Prospective Evaluation of Kidney Disease in Joubert Syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(12):1962–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O’Toole JF, Liu Y, Davis EE, Westlake CJ, Attanasio M, Otto EA, et al. Individuals with mutations in XPNPEP3, which encodes a mitochondrial protein, develop a nephronophthisis-like nephropathy. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(3):791–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Renkema KY, Stokman MF, Giles RH, Knoers NV. Next-generation sequencing for research and diagnostics in kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014;10(8):433–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.