To the Editor

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), caused by novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), rapidly spread worldwide becoming a pandemic.1,2 Whereas most clinical manifestations of COVID-19 are related to respiratory distress, cardiovascular involvement has been reported, showing association with worse outcome and higher mortality.3–5

Given consistent limitations and risks for echocardiography in COVID-19, both American and European echocardiography societies released recommendations to limit systematic echocardiography examination to problem-tailored and time-limited examination, also known as ‘point-of-care ultrasound’ (POCUS).6,7 We aimed to describe cardiac POCUS findings in COVID-19 patients admitted to a tertiary Italian university hospital, stratified according to respiratory distress grade, and to assess the association of cardiac POCUS findings with outcome.

Methods

All laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 patients admitted to our hospital, San Martino Hospital, Genoa, Italy, between 1 March 2020 and 30 April 2020 who underwent cardiac POCUS during hospital stay were analysed. According to the respiratory distress degree,8 patients were classified into mild, moderate, and severe respiratory distress grade.

All methods were extensively described in Supplemental Digital Content S1.

Results

The final population included 138 patients. Table 1 depicts the patients’ characteristics and findings.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical features, point-of-care ultrasound findings, and outcome

| Respiratory distress grade | |||||

| Variable | Overall (n = 138) | Mild (n = 38) | Moderate (n = 35) | Severe (n = 65) | P value |

| Baseline clinical features | |||||

| Age | 65.5 (12.9) | 69.3 (16.2) | 67.1 (11.1) | 62.5 (10.8) | 0.022 |

| Sex (male) | 100 (72.5) | 21 (55.3) | 24 (68.6) | 55 (84.6) | 0.005 |

| Caucasian | 125 (90.6) | 34 (89.5) | 30 (85.7) | 61 (93.8) | 0.399 |

| Hypertension | 74 (53.6) | 21 (55.3) | 22 (62.9) | 31 (47.7) | 0.340 |

| Diabetes | 23 (16.7) | 7 (18.4) | 9 (25.7) | 7 (10.8) | 0.151 |

| Respiratory disease | 23 (16.7) | 8 (21.1) | 5 (14.3) | 10 (15.4) | 0.689 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 21 (15.2) | 7 (18.4) | 10 (28.6) | 4 (6.2) | 0.010 |

| Inflammatory disease | 22 (15.9) | 4 (10.5) | 11 (31.4) | 7 (10.8) | 0.015 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 21 (15.2) | 10 (26.3) | 8 (22.9) | 3 (4.6) | 0.004 |

| Previous LV dysfunction | 10 (7.2) | 5 (13.2) | 5 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.008 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 16 (11.6) | 10 (26.3) | 4 (11.4) | 2 (3.1) | 0.002 |

| D-dimer (μg/l) | 2108.0 (1246.8–6914.8) | 1424.00 (858.0–2688.3) | 1757.0 (1359.5–3619.5) | 4406.0 (1673.0–13553.0) | <0.001 |

| CRP (mg/l) | 90.0 (36.0–177.0) | 46.0 (11.8–73.9) | 80.0 (51.4–143.0) | 136.0 (62.5–262.5) | <0.001 |

| Troponin (μg/l) | 0.02 (0.01–0.12) | 0.01 (0.01–0.08) | 0.01 (0.01–0.06) | 0.03 (0.01–0.15) | 0.001 |

| NT-proBNP (ng/l) | 674.0 (166.0–2036.0) | 904.5 (221.0–2786.5) | 369.0 (114.3–2114.5) | 674.0 (168.0–1396.0) | 0.344 |

| POCUS findings | |||||

| LV dilatation | 7 (5.1) | 2 (5.3) | 2 (5.7) | 3 (4.6) | 0.550 |

| LV hypertrophy | 53 (38.4) | 8 (21.1) | 15 (42.9) | 30 (46.1) | 0.026 |

| EF | 0.188 | ||||

| Normal | 120 (87.0) | 33 (86.8) | 30 (85.7) | 57 (87.7) | |

| Mild dysfunction | 12 (8.7) | 3 (7.9) | 5 (14.3) | 4 (6.2) | |

| Moderate dysfunction | 3 (2.2) | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.1) | |

| Severe dysfunction | 3 (2.2) | 1 (2.6) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (1.5) | |

| LV regional dysfunction | 17 (12.3) | 6 (15.8) | 6 (17.1) | 5 (7.7) | 0.339 |

| Prosthesis valve | 6 (4.3) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (5.7) | 3 (4.6) | 0.799 |

| Valve disease | 20 (14.5) | 6 (15.8) | 5 (14.3) | 9 (13.8) | 0.073 |

| LA enlargement | 20 (14.5) | 9 (23.7) | 6 (17.1) | 5 (7.7) | 0.150 |

| RV dilatation | 37 (26.8) | 5 (13.2) | 6 (17.1) | 26 (40.0) | 0.004 |

| RV dysfunction | 7 (5.1) | 1 (2.6) | 1 (2.9) | 5 (7.7) | 0.404 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation | 0.500 | ||||

| Moderate | 14 (10.1) | 4 (10.5) | 3 (8.5) | 7 (10.7) | |

| Severe | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.8) | 1 (1.5) | |

| Augmented sPAP | 32 (23.1) | 9 (23.7) | 5 (14.3) | 18 (27.6) | 0.305 |

| Pericardial effusion | 50 (36.2) | 13 (34.2) | 12 (34.3) | 25 (38.5) | 0.622 |

| Mild | 48 (35.6) | 13 (34.2) | 12 (34.3) | 23 (35.4) | |

| Moderate | 2 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.1) | |

| Severe | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Tamponade | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Intracardiac thrombosis | 2 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.1) | 0.340 |

| Outcomes | |||||

| All-cause death | 37 (26.8) | 5 (13.2) | 6 (17.1) | 26 (40.0) | 0.171 |

| Myocardial injury | 51 (37.0) | 10 (26.3) | 11 (31.4) | 30 (46.2) | 0.001 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 37 (26.8) | 6 (15.8) | 8 (22.9) | 23 (35.4) | 0.029 |

| Macro | 22 (15.9) | 4 (10.5) | 6 (17.1) | 12 (18.5) | |

| Micro | 15 (10.9) | 2 (5.3) | 2 (5.7) | 11 (16.9) | |

| Venous thromboembolism | 4 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.9) | 3 (4.6) | 0.053 |

| Thrombolysis | 6 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (9.2) | 0.032 |

| Myocardial infarction | 4 (2.9) | 1 (2.6) | 1 (1.9) | 2 (3.1) | 0.308 |

| New onset LV dysfunction | 5 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (7.7) | 0.056 |

| Arrhythmia | 15 (10.9) | 2 (5.3) | 2 (5.7) | 11 (16.9) | 0.292 |

| Atrial | 14 (10.1) | 2 (5.3) | 2 (5.7) | 10 (15.4) | |

| Ventricular | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5) | |

| Myocarditis | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5) | 0.405 |

| Pericarditis | 1 (0.7) | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.308 |

All measures expressed as n (%), mean (SD) or median with IQR (quartile 1 to quartile 3). CRP, C-reactive protein; EF, ejection fraction; LV, left ventricular; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; POCUS, point-of-care ultrasound; RV, right ventricular; sPAP, systolic pulmonary artery pressure.

Bold face reports significant p values (<0.05).

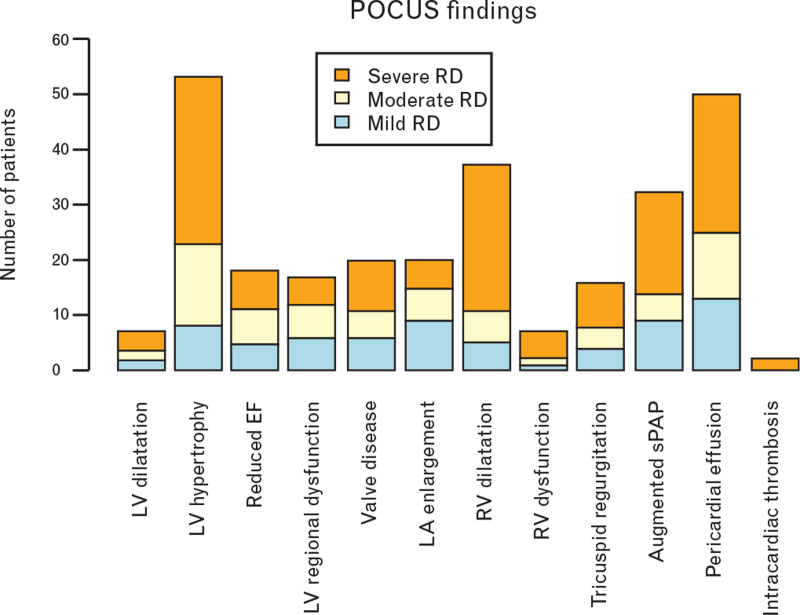

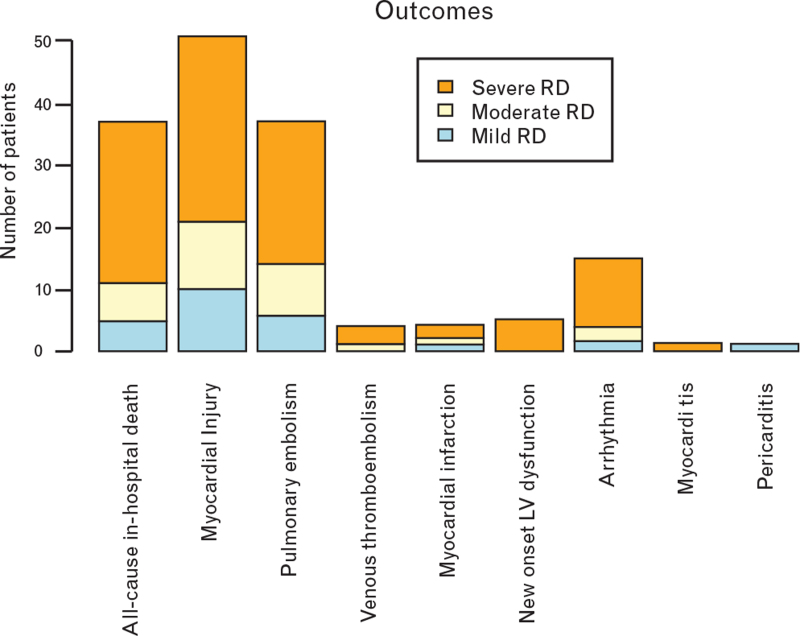

POCUS findings are described in Fig. 1, and outcomes are described in Fig. 2, both stratified according to respiratory distress grade at time of POCUS execution.

Fig. 1.

Point-of-care ultrasound findings according to respiratory distress grade. EF, ejection fraction; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RD, respiratory distress; RV, right ventricle; sPAP, systolic pulmonary artery pressure.

Fig. 2.

Outcomes according to respiratory distress grade. LV, left ventricle; RD, respiratory distress.

At multivariate logistic regression analysis, left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy (P = 0.030) was significantly associated with severe respiratory distress and right ventricular (RV) dilatation (P = 0.036) was significantly associated with longer in-hospital stay. No cardiac POCUS parameter was associated with cardiovascular outcomes (all P > 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate logistic regression models for severe respiratory distress and length of hospital stay (adjusted for age and sex); Cox regression model for all-cause in-hospital death (adjusted for age and sex)

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value |

| Severe respiratory distress | ||||||

| Age | 0.96 | 0.94–0.99 | 0.010 | 0.96 | 0.92–0.99 | 0.041 |

| Sex (male) | 3.42 | 1.54–8.10 | 0.003 | – | – | – |

| D-dimer | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | 0.055 | – | – | – |

| CRP | 1.01 | 1.01–1.02 | <0.001 | 1.02 | 1.01–1.04 | <0.001 |

| Myocardial injury | 8.20 | 3.69–19.66 | <0.001 | 2.49 | 1.77–9.19 | 0.024 |

| Previous ischemic heart disease | 0.15 | 0.03–0.47 | 0.003 | 0.35 | 0.13–0.91 | 0.012 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.13 | 0.02–0.51 | 0.010 | 0.18 | 0.06–0.52 | 0.005 |

| RV dilatation | 3.76 | 1.71–8.74 | 0.001 | – | – | – |

| LV hypertrophy | 3.18 | 1.38–8.09 | 0.010 | 3.59 | 1.20–12.40 | 0.030 |

| Length of hospital stay | ||||||

| Age | 1.03 | 1.00–1.05 | 0.027 | 1.03 | 1.01–1.12 | 0.038 |

| Sex (male) | 1.34 | 0.63–2.86 | 0.447 | |||

| Respiratory failure of severe grade | 2.26 | 1.14–4.56 | 0.020 | 2.83 | 1.22–6.79 | 0.027 |

| D-Dimer | 1.01 | 1.01–1.02 | 0.024 | – | – | – |

| Troponin elevation | 3.65 | 1.59–8.23 | 0.004 | – | – | – |

| RV dilatation | 5.22 | 3.14–27.05 | 0.038 | 2.80 | 1.43–24.06 | 0.036 |

| LV regional dysfunction | 5.23 | 1.82–8.52 | 0.038 | |||

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value |

| All-cause in-hospital death | ||||||

| Age | 1.06 | 1.02–1.11 | 0.004 | 1.03 | 1.01–1.07 | 0.029 |

| Sex (male) | 1.25 | 0.48–3.69 | 0.662 | – | – | – |

| D-Dimer | 1.01 | 1.01–1.02 | 0.024 | – | – | – |

| Troponin elevation | 2.97 | 1.45–6.07 | 0.003 | 2.61 | 1.26–5.41 | 0.010 |

| New onset arrythmia | 2.73 | 1.23–6.06 | 0.014 | – | – | – |

CI, confidence interval; CRP, C-reactive protein; HR, hazard ratio; LV, left ventricle; OR, odds ratio; RV, right ventricle.

Bold face reports significant p values (<0.05).

Comment

Our study has the following main findings: most common cardiac POCUS abnormalities in COVID-19 patients were LV hypertrophy, mild pericardial effusion and RV dilatation, with LV and RV systolic functions mostly preserved; LV hypertrophy was independently associated with severe respiratory distress; RV dilatation was independently associated with longer hospital stay; no cardiac POCUS parameter was associated with in-hospital mortality.

Arterial hypertension, highly prevalent within our cohort (53.6%), is the most common cause for LV hypertrophy.9 Hypertensive heart disease is characterized by cardiac fibrosis, increased myocardial stiffness, microvascular dysfunction, abnormal ventricular--vascular interactions and progressive diastolic dysfunction.10 Diastolic dysfunction was demonstrated as a major predictor of mortality in patients with sepsis and septic shock,11 and recent reports showed a higher degree of diastolic dysfunction associated with poorer prognosis in COVID-19 patients.12,13

Multiple extracardiac mechanisms may induce RV dilatation in COVID-19 patients: extensive lung damage, hypoxic vasoconstriction, excessive positive end-expiratory pressure, high-pressure mechanical ventilation, pulmonary vascular diseases, and pulmonary embolism.

Whereas RV dilatation was a common finding, RV dysfunction was infrequent (5.1%) in our cohort. Although our results are in contrast to previous reports, conventional RV functional parameters (TAPSE, Tei index and RV S’ velocity) resulted within normal ranges both by Szekely et al.13 and Li et al.,14 for which RV dysfunction was determined by short pulmonary acceleration time and reduced RV strain, respectively. These results suggest that RV dysfunction in COVID-19 patients is generally modest and that conventional RV function parameters may be insufficient for risk stratification in this population.

Left ventricle dysfunction was uncommon (13%) and the vast majority of patients had only mild LV dysfunction (66.6%), similar to D’Andrea et al.'s15 findings. Moreover, whereas myocardial injury was frequent and independently associated with in-hospital mortality, most patients had minimal troponin I increase.

Limitations to our study are principally related to the particular situation in which we were operating: the retrospective design, the potential selection bias as only selected COVID-19 patients underwent cardiac POCUS, the lack of prior echocardiographic data for comparison, the lack of systematic diastole assessment, the small sample size, and the large confidence intervals of the estimates.

Acknowledgements

GECOVID-19 Study group: Anna Alessandrini; Marco Camera; Emanuele Delfino; Andrea De Maria; Chiara Dentone; Antonio Di Biagio; Ferdinando Dodi; Antonio Ferrazin; Giovanni Mazzarello; Malgorzata Mikulska; Laura Nicolini; Federica Toscanini; Daniele Roberto Giacobbe; Antonio Vena; Lucia Taramasso; Elisa Balletto; Federica Portunato; Eva Schenone; Nirmala Rosseti; Federico Baldi; Marco Berruti; Federica Briano; Silvia Dettori; Laura Labate; Laura Magnasco; Michele Mirabella; Rachele Pincino; Chiara russo; Giovanni Sarteschi; Chiara sepulcri; Stefania Tutino (Clinica di Malattie Infettive); Roberto Pontremoli; Valentina Beccati; Salvatore Casciaro; Massimo Casu; Francesco Gavaudan; Maria Ghinatti; Elisa Gualco; Giovanna Leoncini; Paola Pitto; Kassem salam (Clinica di Medicina interna 2); Angelo Gratarola; Mattia Bixio; Annalisa Amelia; Andrea Balestra; Paola Ballarino; Nicholas Bardi; Roberto Boccafogli; Francesca Caserza; Elisa Calzolari; Marta Castelli; Elisabetta Cenni; Paolo Cortese; Giuseppe Cuttone; Sara Feltrin; Stefano Giovinazzo; Patrizia Giuntini; Letizia Natale; Davide Orsi; Matteo Pastorino; Tommaso Perazzo; Fabio Pescetelli; Federico Schenone; Maria Grazia Serra; Marco Sottano (Anestesia e Rianimazione; Emergenza Covid padiglione 64 ‘Fagiolone’); Iole Brunetti; Maurizio Loconte; Lorenzo Ball; Denise Battaglini; Chiara Robba; Nicolo’ Patroniti (Anestesiologia e Terapia Intensiva); Roberto Tallone; Massimo Amelotti; Marie Jeanne Majabò; Massimo Merlini; Federica Perazzo (Cure intermedie); Nidal Ahamd; Paolo Barbera; Marta Bovio; Paola Campodonico; Andrea Collidà; Ombretta Cutuli; Agnese Lomeo; Francesca Fezza Nicola Gentilucci; Nadia Hussein; Emanuele Malvezzi; Laura Massobrio; Giulia Motta; Laura Pastorino; Nicoletta Pollicardo; Stefano Sartini; Paola Vacca Valentina Virga (Dipartimento di Emergenza ed accettazione); Italo Porto; Gian Paolo Bezante; Roberta Della Bona; Giovanni La Malfa; Alberto Valbusa; Vered Gil Ad (Clinica Malattie Cardiovascolari); Emanuela Barisione; Michele Bellotti; Aloe’ Teresita; Alessandro Blanco; Marco Grosso; Maria Grazia Piroddi; Maria Grazia Piroddi (Pneumologia ad Indirizzo Interventistico); Paolo Moscatelli; Paola Ballarino; Matteo Caiti; Elisabetta Cenni; Patrizia Giuntini; Ottavia Magnani (Medicine d’Urgenza); Samir Sukkar; Ludovica Cogorno; Raffaella Gradaschi; Erica Guiddo; Eleonora Martino; Livia Pisciotta (Dietetica e nutrizione clinica); Bruno Cavagliere; Rossi Cristina; Farina Francesca (Direzione delle Professioni sanitarie); Giacomo Garibotto; Pasquale Esposito (clinica nefrologica; dialisi e trapianto); Giovanni Passalacqua; Diego Bagnasco; Fulvio Braido; Annamaria Riccio; Elena Tagliabue (Clinica Malattie Respiratorie ed Allergologia); Claudio Gustavino; Antonella Ferraiolo (Ostetricia e Ginecologia); Salvatore Giuffrida; Nicola Rosso (Direzione Amministrativa); Alessandra Morando; Riccardo Papalia; Donata Passerini; Gabriella Tiberio (Direzione di presidio); Giovanni Orengo; Alberto Battaglini (Gestione del rischio clinico); Silvano Ruffoni; Sergio Caglieris.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

The names of members of the GECOVID-19 Study group are mentioned in the Acknowledgements section.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Coronavirus pandemic declaration. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet 2020; 395:470–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clerkin KJ, Fried JA, Raikhelkar J, et al. COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2020; 141:1648–1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shi S, Qin M, Cai Y, et al. Characteristics and clinical significance of myocardial injury in patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019. Eur Heart J 2020; 41:2070–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol 2020; 5:802–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skulstad H, Cosyns B, Popescu BA, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and cardiac imaging: EACVI recommendations on precautions, indications, prioritization, and protection for patients and healthcare personnel. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2020; 21:592–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang G, Vengerovsky A, Morris A, Town J, Carlbom D, Kwon Y. Development of a COVID-19 point-of-care ultrasound protocol. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2020; 33:903–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zayed Y, Askari R. Respiratory distress syndrome. Treasure Island, Florida: StatPearls; 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mancia G, Rea F, Ludergnani M, Apolone G, Corrao G. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockers and the risk of covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:2431–2440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lazzeroni D, Rimoldi O, Camici PG. From left ventricular hypertrophy to dysfunction and failure. Circ J 2016; 80:555–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landesberg G, Gilon D, Meroz Y, et al. Diastolic dysfunction and mortality in severe sepsis and septic shock. Eur Heart J 2012; 33:895–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giustino G, Croft LB, Stefanini GG, et al. Characterization of myocardial injury in patients with COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020; 76:2043–2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szekely Y, Lichter Y, Taieb P, et al. The spectrum of cardiac manifestations in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) – a systematic echocardiographic study. Circulation 2020; 142:342–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Y, Li H, Li M, Zhang L, Xie M. The prevalence, risk factors and outcome of cardiac dysfunction in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Intensive Care Med 2020; 46:2096–2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Andrea A, Scarafile R, Riegler L, et al. Right ventricular function and pulmonary pressures as independent predictors of survival in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2020; 13:2467–2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.