Purpose of review

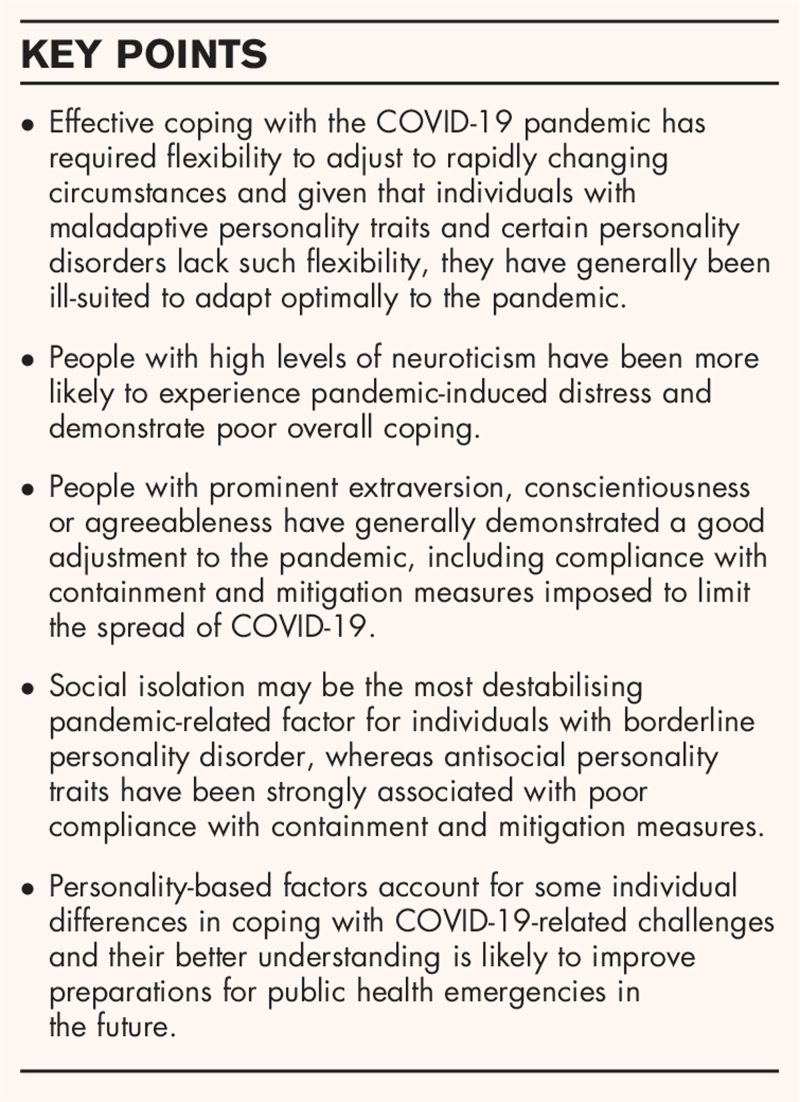

The COVID-19 pandemic has tested people's coping and resilience. This article reviews research and scholarly work aiming to shed more light on personality-based factors that account for adjustment to the pandemic situation.

Recent findings

Most studies relied on a cross-sectional design and were conducted using personality dimensions based on the Big Five personality model. Findings suggest that high levels of neuroticism constitute a risk for pandemic-induced distress and poor overall coping. People with prominent extraversion, conscientiousness or agreeableness have generally demonstrated a good adjustment to the pandemic, including compliance with containment and mitigation measures imposed by the authorities to limit the spread of COVID-19. A few studies of individuals with borderline personality disorder identified social isolation as the most destabilising factor for them. Poor compliance with containment and mitigation measures has been strongly associated with various antisocial personality traits.

Summary

Personality-based factors account for some individual differences in coping with both COVID-19-related threat and distress and requirements to comply with containment and mitigation measures. Better understanding of these factors could contribute to a more effective adjustment to the challenges of future public health crises.

Keywords: coping, COVID-19, personality, personality dimensions, personality disorders

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a challenging event for governments and people around the world. Not only has the illness directly threatened the population globally, but the measures put in place to control the pandemic and mitigate its effects (e.g., physical distancing rules and lockdowns) have often been met with bewilderment, disapproval or active resistance. Therefore, coping with the COVID-19 pandemic has entailed addressing both various COVID-19-related fears and concerns and responding to containment and mitigation measures.

Ability to cope with adversity is largely related to personality structure and coping with multiple aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to be related to the specific personality characteristics. This article will focus on the relationships between personality dimensions, traits and disorders on one hand and COVID-19 pandemic-related variables on the other.

Box 1.

no caption available

PERSONALITY DIMENSIONS AND COVID-19 PANDEMIC

Numerous studies have examined the relationships between various personality dimensions and coping with the COVID-19 pandemic. Most research has used the Big Five theoretical model of personality [1], consisting of the following dimensions: extraversion, neuroticism (sometimes referred to as emotional stability or emotional instability), conscientiousness, agreeableness and openness to experience. Some studies also examined facets of these personality dimensions (e.g., the energy level facet of extraversion, the depression facet of neuroticism, the responsibility facet of conscientiousness, the trust facet of agreeableness and the intellectual curiosity facet of openness to experience).

Extraversion

Considering that extraversion is characterised by a high need for social interactions, it is not surprising that studies found associations between higher levels of extraversion and decreased willingness to comply with some of the COVID-19 pandemic-related containment and mitigation measures, especially physical distancing [2] and staying-at-home requirements [3]. Severely limited opportunities for socialising during the pandemic have also contributed to higher levels of distress among extraverted people [4]. However, extraverts have not been necessarily more likely to break the rules as a result of their need for socialising. Indeed, other research painted a more complex picture of the adaptation of extraverted people to the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, Aschwanden et al.[5▪] reported that higher levels of extraversion were related to a more optimistic estimate of the duration of the pandemic along with a greater caution and more preparatory behaviours such as stockpiling of goods deemed necessary during the pandemic. Moreover, another study suggested that greater extraversion signalled a better adaptation to the pandemic, arguably via greater resilience [6]. Overall, individuals with high levels of extraversion may have had a relatively good adjustment to the COVID-19 pandemic if their natural propensity towards social interactions is kept under control to minimise the risk of becoming infected or spreading the infection.

Neuroticism

Neuroticism refers to a tendency to experience a variety of negative emotions and to be more vulnerable to stress. Given the threatening and immensely disruptive nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, people with higher levels of neuroticism were more likely to have greater concerns about the infection [4,5▪,6], perceive themselves as less effective [4], feel more pessimistic when estimating the duration of the pandemic [5▪] and show worse adaptation to the lockdown [6] and less resilience [7]. The findings regarding compliance of individuals with prominent neuroticism with containment and mitigation measures have been somewhat mixed. While some studies reported a relationship between high levels of neuroticism and greater health precautions such as staying-at-home behaviour [3], physical distancing and hygiene behaviours [8,9], one study found associations with fewer precautions and fewer preparatory behaviours, which was largely driven by the depression facet on neuroticism [5▪]. Overall, it appears that individuals with high levels of neuroticism have not only been particularly distressed by the pandemic, but that their coping with the pandemic may not have been optimal.

Conscientiousness

Conscientiousness is a highly relevant personality dimension for the public health emergency situations such as pandemic because of its links with self-control, ability to organise oneself and plan, social responsibility, compliance with social norms and commitment to duty. During the COVID-19 pandemic, high levels of conscientiousness have been associated with the willingness to comply with containment and mitigation measures, i.e., various precautions to avoid the infection [5▪,10,11], including physical distancing and practicing good hygiene [2,8,9], as well as staying-at-home requirement [3]. People with prominent conscientiousness also felt more effective in their efforts to limit the spread of COVID-19 [4]. Findings about the relationship between conscientiousness and preparatory behaviours were mixed. While one study reported that individuals with high levels of conscientiousness tended to stockpile more toilet paper [12], other research demonstrated that they were not likely to engage in preparatory behaviours, possibly as a result of feeling greater responsibility for others and having more concerns about the community [5▪]. Overall, high levels of conscientiousness seem to have had a high adaptive value in the context of the pandemic, especially with regards to various containment and mitigation measures.

Agreeableness

People with high levels of agreeableness usually cooperate well with others and get along with them because of their general tendency to trust people and empathise with them, while genuinely taking into account their views. Not surprisingly, agreeableness was a predictor of favourable responses to the COVID-19 pandemic [13▪▪] and in one study it was the only Big Five personality dimension that was associated with greater compliance with containment and mitigation measures [14]. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, a combination of prominent agreeableness and high level of conscientiousness has been found to result in a socially desirable behaviour from a public health perspective, fostering compliance with various containment and mitigation measures [3,9]. However, one study showed a negative association between agreeableness and physical distancing [8], possibly because a strong positive orientation to relationships was not compatible with a pandemic-imposed requirement to (temporarily) maintain distance from others. Overall, high levels of agreeableness may have promoted a good adjustment to the pandemic, especially in those domains that require working together with others to control the spread of the infection.

Openness to experience

Openness to experience is also relevant for pandemics because people with high levels of this personality dimension tend to be inquisitive and sceptical, espouse unusual ideas, exhibit unconventional behaviours and may be more prone to risk taking. As such, they are generally nonconformist and not ideally suited to following public health orders and complying with containment and mitigation measures during pandemics. However, high levels of openness to experience were associated with general compliance with containment and mitigation measures during the COVID-19 pandemic [9–11,13▪▪]. This may be due to different strengths of the relationships that various facets of openness to experience have with different indicators of adaptation to the pandemic. For example, the intellectual curiosity facet of openness to experience may relate differently to the willingness to comply with containment and mitigation measures from the creative imagination facet. Overall, preliminary evidence suggests that high levels of openness to experience have not interfered with adaption to the pandemic, especially with regards to compliance with containment and mitigation measures.

HOW MUCH OF COPING WITH THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC IS EXPLAINED BY PERSONALITY DIMENSIONS?

Various personality dimensions do not exist in isolation; rather, they interact with each other and with other variables, which may determine the overall adaptation to the pandemic. Therefore, it is important to have a better picture of the role played by personality in the adjustment to the COVID-19 pandemic and ascertain to what extent personality variables can explain behaviour during the pandemic and coping with it.

A study from Germany conducted in a large and representative sample has directly addressed the role of personality as a predictor of coping with the COVID-19 pandemic [13▪▪]. This study avoided some shortcomings of previous research by using a prospective design and assessing four distinct responses to the pandemic: perception of the risk of becoming infected, behavioural changes designed to prevent the spread of the infection (i.e., containment and mitigation measures), beliefs in the effectiveness of containment and mitigation measures and trust in the authorities and institutions responsible for implementation of these measures. The findings suggested that personality variables accounted only for a small portion of the variance (0.6--3.8%) in these four responses to the pandemic. Despite this, the overall predictive ability of the personality was still considered relevant, especially because other variables (sex, educational level and risk-group membership) explained a similar portion of the variance [13▪▪].

Another German study found greater effects of personality dimensions on COVID-19-related variables compared to the effects of demographic factors such as gender and age [15]. Similarly, a Canadian study reported that almost all demographic factors were only indirectly linked to pandemic coping variables via personality dimensions [16]. A British study involving almost 380,000 people found medium-size associations between personality traits and measures of mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which was lower than associations reported for age, occupation and home and work circumstances [17▪▪]. Regardless of the exact size of their impact, personality-level differences in response to the pandemic seem to be important, calling for further research.

PERSONALITY DISORDERS AND COVID-19 PANDEMIC

Personality disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic have received much less attention than personality dimensions. This is somewhat surprising, considering a large number of studies examining the relationships between various other aspects of psychopathology and coping with the COVID-19 pandemic. However, a greater emphasis on personality dimensions may reflect a general move away from personality disorders as categorical constructs to personality dimensions.

A paper by Preti et al.[18▪] provided hypotheses about the ways in which pandemics in general might affect people with various personality disorders and suggested that responses by these people might depend on the specific type of personality disorder. Thus, individuals with the DSM Cluster A personality disorders, especially those with paranoid personality disorder, might be more likely to espouse various COVID-19-related conspiracy theories and thereby interfere with efforts to effectively cope with the pandemic. People with the DSM Cluster B personality disorders might demonstrate risky behaviours and lack of compliance with containment and mitigation measures due to their impulsivity, while those with the DSM Cluster C personality disorders might react with more anxiety and distress and perhaps be more likely to comply with containment and mitigation measures and potentially experience heightened interpersonal difficulties as a result of their rigidity or excessive reliance on others. These hypotheses have not been tested during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A few studies have focused on the changes experienced by individuals with borderline personality disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic. One naturalistic, exploratory study of 55 patients with borderline personality disorder from Spain reported that living alone was the ‘most relevant’ predictor of a poorer clinical course over a period of 2.5 months during the pandemic [19]. The authors speculated that an imposed social isolation during the pandemic combined with the feeling of loneliness and sensitivity to feeling abandoned as one of the hallmarks of borderline personality disorder made it more difficult for borderline individuals to be on their own and cope with the challenges of the pandemic. Similarly, a case report of a Malaysian patient with borderline personality disorder during the pandemic identified a heightened fear of abandonment, along with a more prominent feeling of emptiness, as emotionally most destabilising factors [20].

Loneliness became a more prominent problem for both 40 patients with borderline personality disorder and 30 patients with avoidant personality disorder during the first several months of the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway [21]. In addition, these borderline patients exhibited more self-injurious behaviours, higher use of emergency services, more aggression and more substance use, when compared to patients with avoidant personality disorder. Interestingly, a proportion of borderline patients exhibited the opposite pattern during the pandemic, reporting fewer symptoms and more energy [21].

An online Polish study of 720 individuals from the general population examined people who did not believe in the existence of COVID-19 and found that these ‘nonbelievers’ were more likely to show characteristics of borderline personality organisation and use maladaptive defence mechanisms, especially splitting [22].

Antisocial personality disorder, antisocial personality traits and antisocial behaviours have received some research attention during the COVID-19 pandemic, mainly because of the concern that such personality constellation might interfere with efforts to limit the spread of the infection. Indeed, a study from Brazil involving 1578 participants found that some of the key traits of antisocial personality disorder, such as low levels of empathy and high levels of callousness, deceitfulness and risk-taking were strongly and directly associated with decreased compliance with COVID-19 containment and mitigation measures [23]. Similarly, an online study of 131 individuals from the United States reported that those with prominent antisocial traits engaged in behaviours that had a potential to enhance the spread of COVID-19, i.e., they were less likely to follow physical distancing rules [24].

A few studies have investigated the relationships between compliance with COVID-19 containment and mitigation measures and the Dark Triad personality traits, which are conceptually related to antisocial personality disorder and more broadly, the DSM Cluster B personality disorders. The Dark Triad comprises psychopathy (e.g., callousness and remorselessness), Machiavellianism (e.g., manipulativeness and exploitation of others) and narcissism (e.g., grandiosity and lack of empathy). Predictably, all or some components of the Dark Triad have been strongly associated with a decreased willingness to comply with efforts to limit the spread of COVID-19 largely because of the requirement to accept personal restrictions [9,11,14], although some findings were equivocal in this regard [15].

CONCLUSION

Coping with the COVID-19 pandemic has required both an adequate appraisal of the threat posed by COVID-19 itself and working together with other members of the society to limit the spread of the infection. These efforts largely depend on people's flexibility to adjust to rapidly changing circumstances. Given their general lack of flexibility, especially in an interpersonal domain, individuals with certain personality disorders and those with prominent maladaptive personality dimensions such as neuroticism may have a particular difficulty adapting to the pandemic. Studies conducted to date have supported this notion, notwithstanding their methodological limitations and a paucity of research focused on personality disorders. Further investigations of personality variables and personality disorders during public health crises are important because they are likely to improve our understanding of the specific personality-based liabilities for coping with such crises. Ultimately, this knowledge could have relevance for public health policy and contribute to more effective ways of preparing for public health emergencies in the future.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

▪ of special interest

▪▪ of outstanding interest

REFERENCES

- 1.McCrae RR, Costa PT. Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. J Pers Soc Psychol 1987; 52:81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carvalho LF, Pianowski G, Gonçalves AP. Personality differences and COVID-19: are extroversion and conscientiousness personality traits associated with engagement with containment measures? Trends Psychiatry Psychother 2020; 42:179–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Götz FM, Gvirtz A, Galinsky AD, et al. How personality and policy predict pandemic behavior: understanding sheltering-in-place in 55 countries at the onset of COVID-19. Am Psychol 2021; 76:39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu S, Lithopoulos A, Zhang C-Q, et al. Personality and perceived stress during COVID-19 pandemic: testing the mediating role of perceived threat and efficacy. Pers Individ Differ 2021; 168:110351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5▪.Aschwanden D, Strickhouser JE, Sesker AA, et al. Psychological and behavioural responses to coronavirus disease 2019: the role of personality. Eur J Person 2021; 35:51–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study assessed personality dimensions before and during the COVID-19 pandemic and investigated the relationships between these dimensions and various responses to the pandemic.

- 6.Morales-Vives F, Dueñas J-M, Vigil-Colet A, et al. Psychological variables related to adaptation to the COVID-19 lockdown in Spain. Front Psychol 2020; 11:565634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kocjan GZ, Kavčič T, Avsec A. Resilience matters: explaining the association between personality and psychological functioning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Clin Health Psychol 2021; 21:100198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdelrahman M. Personality traits, risk perception, and protective behaviors of Arab residents of Qatar during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Ment Health Addict 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blagov PS. Adaptive and dark personality in the COVID-19 pandemic: predicting health-behavior endorsement and the appeal of public-health messages. Soc Psychol Personal Sci 2021; 12:697–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bogg T, Milad E. Demographic, personality, and social cognition correlates of coronavirus guideline adherence in a U.S. sample. Health Psychol 2020; 39:1026–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zettler I, Schild C, Lilleholt L, et al. The role of personality in COVID-19-related perceptions, evaluations, and behaviors: findings across five samples, nine traits, and 17 criteria. Soc Psychol Personal Sci 2021; 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garbe L, Rau R, Toppe T. Influence of perceived threat of Covid-19 and HEXACO personality traits on toilet paper stockpiling. PLoS ONE 2020; 15:e0234232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13▪▪.Rammstedt B, Lechner CM, Weiß B. Does personality predict responses to the COVID-19 crisis? Evidence from a prospective large-scale study. Eur J Person 2021; 1–14. [Google Scholar]; This study, conducted in a large and representative sample of the general population, used a prospective design to investigate the role of personality dimensions as predictors of distinct responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- 14.Zajenkowski M, Jonason PK, Leniarska M, et al. Who complies with the restrictions to reduce the spread of COVID-19? Personality and perceptions of the COVID-19 situation. Pers Individ Differ 2020; 166:110199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Modersitzki N, Phan LV, Kuper N, et al. Who is impacted? Personality predicts individual differences in psychological consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. Soc Psychol Personal Sci 2021; 12:1110–1130. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Volk AA, Brazil KJ, Franklin-Luther P, et al. The influence of demographics and personality on COVID-19 coping in young adults. Pers Individ Differ 2021; 168:110398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17▪▪.Hampshire A, Hellyer PJ, Soreq E, et al. Associations between dimensions of behaviour, personality traits, and mental-health during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom. Nat Commun 2021; 12:4111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is a very large study that investigated comprehensively a variety of factors, including personality traits, which have had an impact on mental health aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- 18▪.Preti E, Di Pierro R, Fanti E, et al. Personality disorders in time of pandemic. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2020; 22:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article provides important theoretical perspectives on coping by people with personality disorders with pandemics in general.

- 19.Alvaro F, Navarro S, Palma C, et al. Clinical course and predictors in patients with borderline personality disorder during the COVID-19 outbreak: a 2.5-month naturalistic exploratory study in Spain. Psychiatry Res 2020; 292:113306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chong SC. Psychological impact of coronavirus outbreak on borderline personality disorder from the perspective of mentalizing model: a case report. As J Psychiatry 2020; 52:102130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zahl K-E, Pedersen G, Eikenaes Ultveit-Moe I, et al. Patients with borderline and avoidant personality disorders in the pandemic and their mental distress during the Covid-19 crisis in Norway. Res Square 2021; 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zajenkowska A, Nowakowska I, Bodecka-Zych M, et al. Defense mechanisms and borderline personality organization among COVID-19 believers and nonbelievers during complete lock-down. Front Psychiatry 2021; 12:700774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miguel FK, Machado GM, Pianowski G, et al. Compliance with containment measures to the COVID-19 pandemic over time: do antisocial traits matter? Pers Individ Differ 2021; 168:110346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Connell K, Berluti K, Rhoads SA, et al. Reduced social distancing early in the COVID-19 pandemic is associated with antisocial behaviors in an online United States sample. PLoS ONE 2021; 16:e0244974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]