Abstract

Telehealth has always held great promise to increase access to mental health care, never more so than in the age of COVID-19, when clients can’t or won’t come to the clinician’s physical location. A feasible and effective alternative to traditional in-person care, telemental health requires that clinicians adopt new strategies to build and maintain communication and the therapeutic relationship. This can be particularly troublesome for clinicians new to the modality, who may feel the loss of the “in-session” experience more acutely. As an evidence-based practice that is transtheoretical and transdiagnostic, telemental health measurement-based care (tMBC) is the ideal complement to enhance systematic ongoing monitoring, treatment engagement, and therapeutic alliance in the context of the virtual encounter. While tMBC mechanisms of actions are still being explored, there is promising evidence that tMBC improves clinician responsivity to acute client concerns. By using client-reported measures, tMBC provides an important pathway for clients to systematically communicate with their clinicians, which can guide therapeutic actions and contribute to shared understanding. This brief report summarizes the evidence for tMBC as a patient-centered communication tool and provides recommendations for evidence-based and practice-informed strategies to integrate tMBC into telehealth solutions, with suggestions for monitoring new concerns related to the COVID-19 crisis.

Keywords: Measurement-based care, telehealth, treatment engagement, therapeutic alliance, COVID-19

In addition to coping with the stresses of a global pandemic, mental health clinicians have had to rapidly transition to telemental health (TMH) services to protect themselves and their clients. TMH is a feasible and effective alternative to traditional in-person care, and has some unique benefits, such as opportunities for enhanced ecological validity of treatment that happens in the client’s “real world” settings (Comer, 2015). This new way of working together, however, presents a significant change in communication with the loss of the physical intimacy of face-to-face therapy. While TMH does not appear to be a barrier to building the therapeutic relationship, and may even afford opportunities for improved therapeutic alliance and empathy (see Comer & Timmons, in press), it does require new strategies for the clinician in order to maintain that relationship (Chakrabarti, 2015; Grondin et al., in press; Hilty et al., 2019). In addition, given the increased risk that vulnerable clients may deteriorate due to the stresses of the COVID-19 outbreak (e.g., social isolation, financial stress), strong communication and engagement in treatment is more important than ever. Telemental health measurement-based care (tMBC) is an ideal complement to enhance ongoing monitoring, shared understanding, and treatment engagement in the context of the virtual encounter. MBC is founded upon the premise that high-quality and continuous feedback will improve clinician competency and enhance client outcomes (Claiborn & Goodyear, 2005). In the shifting landscape of the COVID-19 crisis, and with the sudden transition to TMH, tMBC can be a crucial part of boosting confidence and competence as clinicians adjust to the new normal of technology-enabled mental health care.

tMBC is a Patient-Centered Communication Tool

Operationalized as the systematic collection of assessment data, typically before or during sessions, to monitor treatment progress and inform clinical decision-making (Scott & Lewis, 2015), MBC is considered an evidence-based practice that is transtheoretical and transdiagnostic, with broad applicability across mental health settings, treatment types, and populations (American Psychological Association, 2006). Lewis and colleagues (2019) recently summarized the results of nine systematic reviews and meta-analyses and concluded that MBC leads to improved client outcomes, particularly for those identified as not responding to treatment.

The foundation of MBC is client- and/or caregiver-reported measures of symptoms, but the utility of MBC may be enhanced with other measures, such as the therapeutic alliance (Goldberg et al., 2019) or skill confidence and use (Hooke & Page, 2017). When MBC is delivered on a web-based platform, the interpreted assessment feedback can be viewed in real time by clinicians, allowing them to tailor care in the moment based on any unexpected developments or lack of progress. As a form of patient-centered communication (Carlier et al., 2012), MBC feedback reports provide a concrete, visual pathway to promote shared understanding.

While the mechanisms of action of MBC have not been clearly demonstrated empirically, it likely influences care at the client, clinician, and organizational levels. At the client level, therapeutic assessment theory (Finn & Tonsager, 1997) posits that assessment and feedback enhance outcomes by improving the client’s understanding of their problems, their treatment engagement, and the therapeutic alliance. At the clinician level, the contextual feedback intervention theory (Riemer & Bickman, 2011) proposes that the recognition of a discrepancy between treatment goals and client status leads to cognitive dissonance, which then prompts the clinician to take action. For example, MBC has been found to contribute to greater speed and responsivity of clinician’s addressing acute client and/or caregiver problems (Douglas et al., 2015). MBC feedback also informs case conceptualization and supervision. At the organizational level, MBC can support continuous quality improvement by providing a “golden thread” of client-level data aggregated from the bottom up throughout the agency to inform organizational decision-making (Douglas et al., 2016).

Practical Recommendations for Telemental Health Measurement-Based Care (tMBC)

Aided by a review of relevant practice guidelines for telemental health (e.g., “Amidst COVID-19,” 2020; Comer & Myers, 2016; Joint Task Force for the Development of Telepsychology Guidelines for Psychologists, 2013; Maheu et al., 2020; Myers et al., 2017), we have compiled several evidence-based and practice-informed strategies to enhance tMBC feasibility and accessibility with specific recommendations for measures and COVID-19. Table 1 provides a summary of tMBC strategies. In addition, supplementary materials including clinician guides, client handouts, and a brief case example video are freely available at https://www.mirah.com/covid-19.

Table 1.

Summary of Evidence-Based and Practice-Informed Recommendations for Telemental Health Measurement-Based Care (tMBC)

| Feasibility and accessibility of tMBC integration into TMH workflow | |

| Introducing tMBC to clients | Present tMBC as an important communication tool |

| Sending links by text message (SMS) or email for clients to complete measures | Sending links increases feasibility and allows data collection to occur between sessions rather than taking up session time. |

| Setting up your screen(s) | If possible, have multiple windows open to facilitate simultaneous viewing of the client, feedback reports, and any other clinical tools |

| Sharing feedback with clients | Screen sharing can be used to share feedback reports directly with clients |

| Billing and reimbursement for MBC |

CPT code 96127 covers brief behavioral or emotional assessments |

| tMBC measures considerations | |

| Brief symptom rating scales | Brief rating scales with established norms facilitate monitoring symptoms and identifying key patterns such as improvement, deterioration, or moving into the non-clinical range. |

| Individualized items | Having clients identify problems or goals in their own words and rate them over time facilitates a tailored and flexible approach to tMBC |

| Monitor risk | Rating scales or individualized items can be used to monitor risk variables such as suicidality or clinical deterioration |

| Treatment process measures | Monitoring variables like the therapeutic alliance increases the “actionability” of tMBC |

| COVID-19 specific suggestions | COVID-19 screening questions can be incorporated into tMBC |

Integrating tMBC into TMH Workflow

Introducing tMBC to clients.

Over the years, we have learned that clinicians who are high users of MBC often introduce it to clients as standard part of care and a vital tool that helps them do their jobs. They stress the communication aspects of MBC and set dual expectations for the client’s role (to complete the measures on the agreed-upon schedule), as well as their own role (they will review the resulting feedback and address in sessions as needed). For TMH, tMBC may also have a key role as part of back-up plans for communication if there are technical difficulties that interfere with or prevent a session so that the client can still be supported (Lopez et al., 2019). Moreover, tMBC affords opportunities for asynchronous, between-session communication that can inform session preparations and expectations for both parties.

Sending links by text message (SMS) or email for clients to complete measures.

MBC approaches vary broadly in how measures are administered and scored, how results are presented to clinicians, etc. For purposes of tMBC, we recommend web-based platforms that at minimum, allow for sending links by text message or email for clients. By clicking on the link, the client will be able to enter their responses within a HIPAA-compliant and encrypted secure platform. Not only does this ensure confidentiality of data per TMH practice guidelines, but it also supports feasibility. Numerous digital MBC platforms exist (Lyon et al., 2016), and many of them have this functionality, including Better Outcomes Now (https://betteroutcomesnow.com/), Mirah (https://www.mirah.com/), OQ Analyst (https://www.oqmeasures.com/), and Owl Insights https://www.owlinsights.com/). Other technology features to look for are integration with electronic health records and/or telemental health platforms, automated scheduling of measures, and the ability to tailor measures to treatments, populations, or contexts of interest. It should be noted that web-based MBC platforms can function on any operating system where an internet browser can be used, so there is no need for special equipment.

Setting up your screen(s).

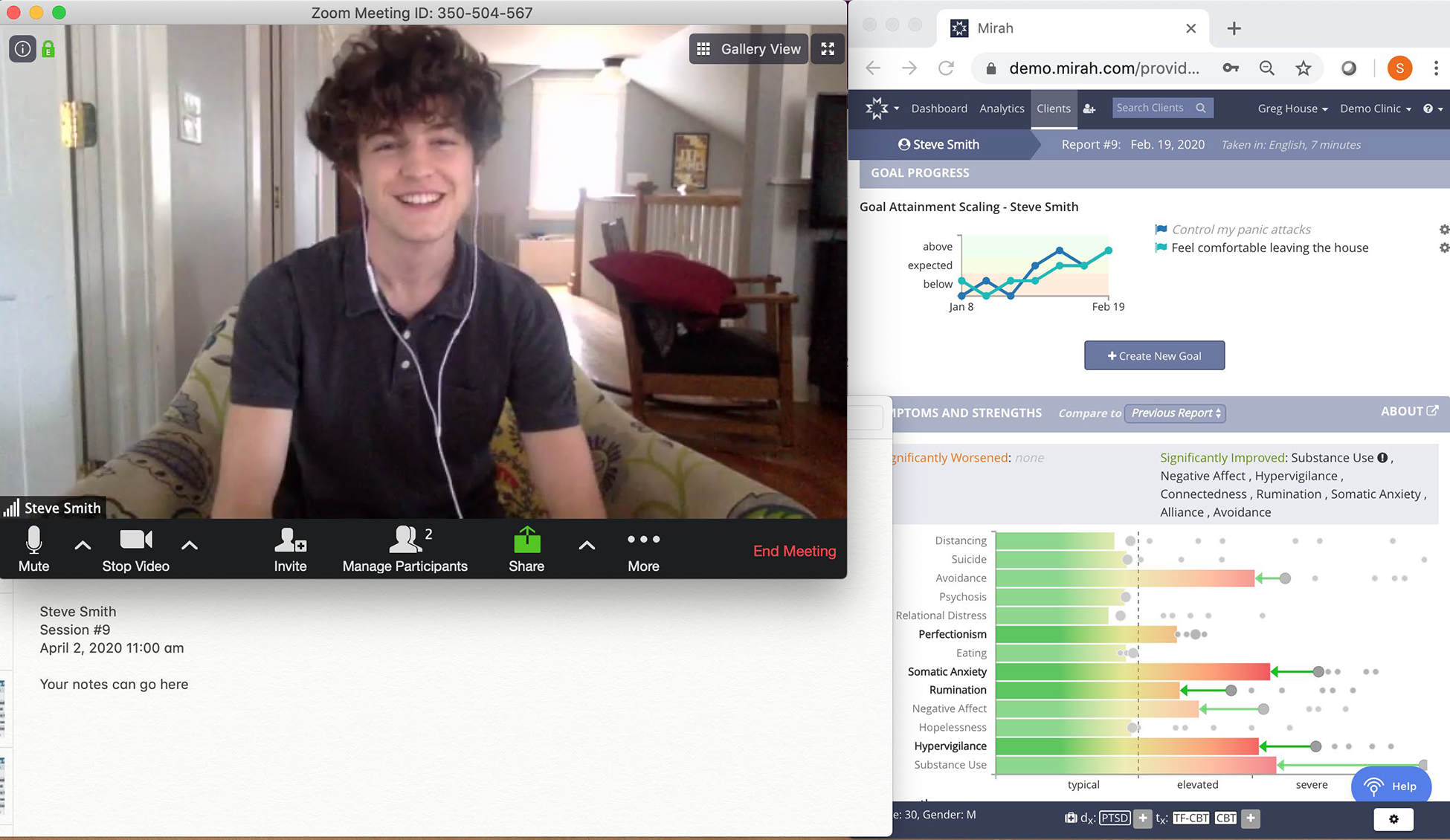

Computer-assisted assessment has always been one of the more difficult aspects to implement within traditional in-person mental health practice, with concerns related to the impact of the technology on the relationship and practical issues, such as keeping track of tablets used for measure completion or placement of a screen within the physical setting of treatment (e.g., Patel et al., 2017). In TMH, the ecological validity of the technology-enabled interaction would likely serve to improve the integration of tMBC as an active part of the treatment encounter, which may improve implementation and outcomes (e.g., Bickman et al., 2016). As shown in Figure 1, it is relatively simple to “size” multiple windows so the clinician can open the most recent MBC feedback report alongside the video of the client. Having multiple monitors makes this even more feasible. In addition, having a third window open to take notes in session rather than hand-writing supports continuous attention to the screen, which may promote better eye contact and comfort for the clinician. However, other clinicians may be more comfortable taking notes by hand as they would do during an in-person session, and clinicians should prioritize setting up their system in a way that feels most natural to them.

Figure 1. Example of a Screen View of Multiple Windows for tMBC.

Note: For this example, we placed the MBC feedback report in a window to the right. On the left is the window containing the image of the client (not a real client). Below the client’s image is a space for notes. The technology that was used for this screenshot was a laptop with a 12-inch screen; a text-based notes application; Zoom videoconferencing software which has an option for HIPAA-compliant telehealth (https://zoom.us/docs/doc/Zoom%20for%20Healthcare.pdf); and Mirah, an MBC platform (https://www.mirah.com).

Sharing feedback with clients.

A core component of MBC’s impact on outcomes is the active use of feedback to inform care. Clinicians should strive to share feedback in sessions, by asking questions about results that were unexpected or addressing treatment gains or lack thereof. The sharing of feedback with clients reinforces their measure completion, but is also considered a mechanism of action for MBC. In traditional in-person settings, we often hear clinicians talk about “turning their screens around,” so both the client and clinician can view aspects of the MBC feedback together. We recommend the same for tMBC, where the clinician would “share” the MBC window using the selected technology, with two caveats. First, the clinician should ensure competency with the TMH technology and practice how to share a selected window but not the whole screen so unintended information is not seen. Second, we advise clinicians that deciding how and what to share from the feedback is a clinical judgment based on their knowledge of the client and the clinical issues at hand. Clinicians may choose to share all or a portion of the screen or simply discuss the feedback in conversation.

Billing and reimbursement for MBC.

An important consideration to increase feasibility of tMBC is billing for remote care. Passed in March 2020, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act (HR 748) provided funding for broadband services, expanded Medicare coverage, and created new allowances for telehealth at federally-qualified health centers (FQHCs) and rural health clinics (RHCs). Importantly, the CARES Act encouraged the use of remote patient monitoring for home health services, which is a core role for MBC in monitoring mental health symptoms. In January 2015, the mental health parity provisions of the Affordable Care Act made the American Medical Association’s CPT code 96127 available for use to report administration of brief behavioral or emotional assessments, with scoring and documentation, using standardized instruments (American Medical Association, 2019)

tMBC Measures Considerations

The ideal measures for MBC are brief, sensitive to change, clinically actionable, and relevant to key stakeholders (e.g., clients, caregivers, etc., Douglas Kelley & Bickman, 2009). The good news is that there are numerous free, brief symptom rating scales that are suitable for MBC (Becker-Haimes et al., 2020; Beidas et al., 2015). Rating scales offer a number of benefits, including the ability to compare client data to norms, and they are a central feature of most MBC systems. It can be useful, however, to also track individualized items tailored to the client’s goals or problems. These items, where clients identify problems and goals in their own words and rate them over time, may be more sensitive to change, and may also promote client engagement by focusing on topics most important to them (Jensen-Doss et al., 2018). Particularly under uncertain circumstances like the COVID-19 crisis, these items can provide flexibility around tracking unique challenges that may not traditionally appear in rating scales (e.g., stresses of remote working, social isolation, etc.).

Either rating scales or individualized items can also be used to monitor client risk, such as increased suicidality or child abuse. MBC involving such items of course raises ethical needs to monitor client responses, and some tMBC platforms have the ability to send alerts to clinicians when risk items are endorsed. Many tMBC systems also have algorithms to alert clinicians when clients’ symptoms are deteriorating, which can be extremely helpful in times of crisis.

MBC becomes more “actionable” if it also includes measures of therapy processes, and evidence suggests that a broader assessment battery can be used to turn care around when clients are not responding to treatment (Lambert, 2015). As a potential key mechanism of action for MBC, therapeutic alliance can be particularly useful to monitor. Within the context of telehealth, where it can be more difficult for the clinician to read nonverbal cues about the alliance, systematically measuring therapeutic alliance in tMBC presents clinicians with the opportunity to identify and address any alliance ruptures more quickly. Unique aspects of the TMH therapy process to measure include satisfaction with the technology, environment distractions, etc.

Finally, there are opportunities for novel applications of tMBC specific to the COVID-19 crisis. For example, all health care organizations have been recommended to screen for risk of possible virus transmission as part of all in-person visits (e.g., U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-criteria.html). If desired and possible with the tMBC platform, a COVID-19 screen for symptoms and exposure could be added to MBC protocols.

Conclusions

The field is witnessing a transition to telemental health (TMH) on a massive scale in response to the COVID-19 crisis, consistent with the suggestion that one of its most relevant applications is during or after a crisis when in-person interactions are not possible (Augusterfer et al., 2018). The “silver lining,” or opportunity to be found in this crisis, may be that the surge leads to greater acceptability and ongoing use of TMH after the global pandemic subsides. As an evidence-based and transtheoretical practice, tMBC promotes patient-centered communication and holds substantial promise to enhance treatment engagement and alliance when used to complement TMH. Clinical trials that have incorporated tMBC into TMH treatment have already shown initial success for this model of care, with some evidence that such services can at times even outperform traditional office-based care (Comer et al., 2017). The feedback resulting from systematic and ongoing assessment of client symptoms and therapy processes provides a strong foundation for improving clinician competency. The ability to visually share tMBC feedback between client and clinician provides an ecologically valid and creative strategy to optimize communication and co-create shared understanding within the telemental health context.

CLINICAL IMPACT STATEMENT:

This brief report suggests practical strategies to integrate measurement-based care into telemental health services. With a focus on feasibility, recommendations address clinical workflow and considerations for measures selection. COVID-19 specific information related to reimbursement and measures is provided.

Acknowledgments

Susan Douglas and Amanda Jensen-Doss were supported in this work by the National Institute of Mental Health (R34 MH118316). Susan Douglas reported receipt of compensation related to the Peabody Treatment Progress Battery and a financial relationship with Mirah; there is a management plan to ensure that this conflict does not jeopardize the objectivity of her research.

No other disclosures were reported.

References

- American Medical Association. (2019). CPT Professional 2020 (Revised edition). Optuminsight Inc. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2006). Evidence-based practice in psychology. American Psychologist, 61, 271–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amidst COVID-19 outbreak, what resources can you use. (2020, April 21). Retrieved from https://www.nationalregister.org/coronavirus-resources/

- Augusterfer EF, Mollica RF, & Lavelle J (2018). Leveraging Technology in Post-Disaster Settings: The Role of Digital Health/Telemental Health. Current Psychiatry Reports, 20(10), 88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker-Haimes EM, Tabachnick AR, Last BS, Stewart RE, Hasan-Granier A, & Beidas RS (2020). Evidence Base Update for Brief, Free, and Accessible Youth Mental Health Measures. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 49(1), 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Stewart RE, Walsh L, Lucas S, Downey MM, Jackson K, Fernandez T, & Mandell DS (2015). Free, Brief, and Validated: Standardized Instruments for Low-Resource Mental Health Settings. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(1), 5–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickman L, Douglas S, De Andrade AR, Vides, Tomlinson M, Gleacher A, Olin S, & Hoagwood K (2016). Implementing a Measurement Feedback System: A Tale of Two Sites. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43, 410–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlier IVE, Meuldijk D, Van Vliet IM, Van Fenema E, Van der Wee NJA, & Zitman FG (2012). Routine outcome monitoring and feedback on physical or mental health status: Evidence and theory. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 18, 104–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti S (2015). Usefulness of telepsychiatry: A critical evaluation of videoconferencing-based approaches. World Journal of Psychiatry, 5(3), 286–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claiborn CD, & Goodyear RK (2005). Feedback in psychotherapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(2), 209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer JS (2015). Introduction to the special series: Applying new technologies to extend the scope and accessibility of mental health care. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(3), 253–257. [Google Scholar]

- Comer JS, Furr JM, Miguel EM, Cooper-Vince CE, Carpenter AL, Elkins RM, Kerns CE, Cornacchio D, Chou T, & Coxe S (2017). Remotely delivering real-time parent training to the home: An initial randomized trial of Internet-delivered parent–child interaction therapy (I-PCIT). Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(9), 909–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer JS, & Myers K (2016). Future directions in the use of telemental health to improve the accessibility and quality of children’s mental health services. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 26(3), 296–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer JS, & Timmons AC (in press). The other side of the coin: Computer-mediated interactions may afford opportunities for enhanced empathy in clinical practice. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas Kelley S, & Bickman L (2009). Beyond outcomes monitoring: Measurement feedback systems in child and adolescent clinical practice. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 22(4), 363–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas S, Button S, & Casey SE (2016). Implementing for sustainability: Promoting use of a measurement feedback system for innovation and quality improvement. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(3), 286–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas S, Jonghyuk B, Andrade A. R. V. de, Tomlinson MM, Hargraves RP, & Bickman L (2015). Feedback mechanisms of change: How problem alerts reported by youth clients and their caregivers impact clinician-reported session content. Psychotherapy Research, 25(6), 678–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn SE, & Tonsager ME (1997). Information-gathering and therapeutic models of assessment: Complementary paradigms. Psychological Assessment, 9(4), 374–385. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg SB, Rowe G, Malte CA, Ruan H, Owen JJ, & Miller SD (2019). Routine monitoring of therapeutic alliance to predict treatment engagement in a Veterans Affairs substance use disorders clinic. Psychological Services. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grondin F, Lomanowska AM, & Jackson PL (in press). Empathy in computer-mediated interactions: A conceptual framework for research and clinical practice. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. [Google Scholar]

- Hilty D, Randhawa K, Maheu M, McKean A, Pantera R (2019). Therapeutic relationship of telepsychiatry and telebehavioral health: Ideas from research on telepresence, virtual reality and augmented reality. Psychology and Cognitive Sciences, 5(1), 14–29. doi: 10.17140/PCSOJ-5-145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hooke GR, & Page AC (2017, June). Tailored progress conitoring questions that respond to patient responses dynamically: How does this inform clinicians, how does this assist patient treatment? International Meeting of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, Toronto, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen-Doss A, Smith AM, Becker-Haimes EM, Ringle V, Walsh L, Nanda M, Walsh S, Maxwell CA, & Lyon AR (2018). Individualized Progress Measures Are More Acceptable to Clinicians Than Standardized Measures: Results of a National Survey. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 45(3), 392–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint Task Force for the Development of Telepsychology Guidelines for Psychologists. (2013). Guidelines for the practice of telepsychology. American Psychologist, 68(9), 791–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MJ (2015). Progress feedback and the OQ-system: The past and the future. Psychotherapy, 52(4), 381–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis CC, Boyd M, Puspitasari A, Navarro E, Howard J, Kassab H, Hoffman M, Scott K, Lyon A, Douglas S, Simon G, & Kroenke K (2019). Implementing Measurement-Based Care in Behavioral Health: A Review. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(3), 324–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez A, Schwenk S, Schneck CD, Griffin RJ, & Mishkind MC (2019). Technology-Based Mental Health Treatment and the Impact on the Therapeutic Alliance. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(8), 76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maheu MM, Drude KP, Hertlein KM et al. (2020). Correction to: An interprofessional framework for telebehavioral health competencies. Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science, 5, 79–111. 10.1007/s41347-019-00113-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Myers K, Nelson E-L, Rabinowitz T, Hilty D, Baker D, Barnwell SS, Boyce G, Bufka LF, Cain S, & Chui L (2017). American telemedicine association practice guidelines for telemental health with children and adolescents. Telemedicine and E-Health, 23(10), 779–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel MR, Vichich J, Lang I, Lin J, & Zheng K (2017). Developing an evidence base of best practices for integrating computerized systems into the exam room: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 24(e1), e207–e215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemer M, & Bickman L (2011). Using program theory to link social psychology and program evaluation. (pp. 102–139). Guilford Press; (New York, NY, US: ). [Google Scholar]

- Scott K, & Lewis CC (2015). Using measurement-based care to enhance any treatment. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(1), 49–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]