While ozone increases rapidly in wildfire plumes, downwind its production rate slows dramatically as nitrogen oxide levels decline.

Abstract

Wildfires are a substantial but poorly quantified source of tropospheric ozone (O3). Here, to investigate the highly variable O3 chemistry in wildfire plumes, we exploit the in situ chemical characterization of western wildfires during the FIREX-AQ flight campaign and show that O3 production can be predicted as a function of experimentally constrained OH exposure, volatile organic compound (VOC) reactivity, and the fate of peroxy radicals. The O3 chemistry exhibits rapid transition in chemical regimes. Within a few daylight hours, the O3 formation substantially slows and is largely limited by the abundance of nitrogen oxides (NOx). This finding supports previous observations that O3 formation is enhanced when VOC-rich wildfire smoke mixes into NOx-rich urban plumes, thereby deteriorating urban air quality. Last, we relate O3 chemistry to the underlying fire characteristics, enabling a more accurate representation of wildfire chemistry in atmospheric models that are used to study air quality and predict climate.

INTRODUCTION

Wildfires emit large quantities of reactive trace species to the atmosphere, including primary pollutants, as well as precursors for the production of O3 and particulate matter (1, 2). The number and size of wildfires are predicted to increase as a result of historical fire suppression practices and ongoing climate change (3). This threatens to offset some of the improvements in air quality in the United States over the past few decades, particularly during fire season (4).

O3 formation depends on the mix of initial emissions and the postemission atmospheric processing, both of which are highly variable (Fig. 1). As a result, O3 formation observed in previous field studies exhibits substantial fire-to-fire variability (5). Numerous studies have investigated O3 chemistry in wildfire plumes using atmospheric models of different dynamical and chemical complexity (6–11), but accurate simulation of wildfire chemistry has proved challenging. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the model deficiencies, such as uncertain emission inventories, inaccurate description of oxidation chemistry, and difficulties in modeling plume dispersion. O3 production from wildfire emissions remains as a major uncertainty in assessing the tropospheric O3 burden (12).

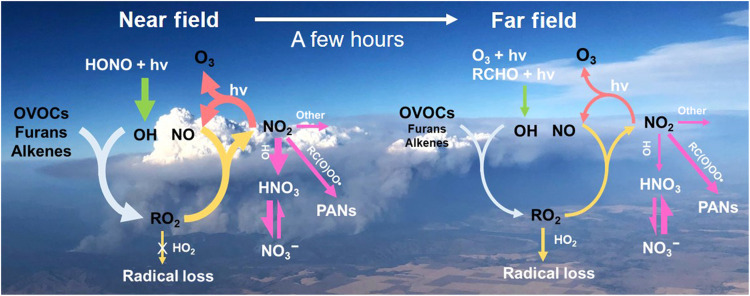

Fig. 1. Simplified scheme to illustrate the factors influencing O3 formation in wildfire plumes.

Wildfires emit oxidant precursors, NOx, and an enormous diversity of VOCs. In the near field, OH produced via photolysis of HONO initiates VOC oxidation, which proceeds in the presence of NOx and leads to efficient O3 formation. After a few hours, the HONO has been consumed and NOx has been both diluted sufficiently and converted to PANs and such that the O3 formation slows by several orders of magnitude. In this simplified scheme, the width of arrows having the same color represents the relative importance of competing pathways.

The in situ observations of a suite of trace species made during the Fire Influence on Regional to Global Environments and Air Quality (FIREX-AQ) campaign (Supplementary Materials, section S1) enable a detailed diagnosis of key variables controlling O3 formation, including oxidant sources, volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions, and the chemistry of NOx and peroxy radicals (RO2; the sum of hydroperoxy radical and organic peroxy radical) (Fig. 1). These variables depend on fire conditions, undergo rapid transitions in chemical regimes, and hence profoundly influence the O3 chemistry during smoke transport. Building upon our systematic evaluation of O3 chemistry, we provide a parameterization to estimate the O3 formation from temperate wildfires.

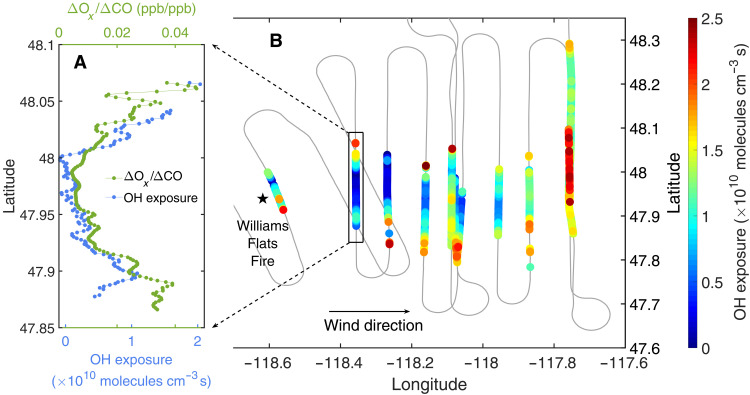

During FIREX-AQ, the NASA DC-8 aircraft sampled fires representative of those in the major ecosystems in the western United States in July and August 2019. Figure 2B shows one example flight track that involves multiple crosswind transects of a fire plume at different distances downwind. Previous analyses of aircraft-based observations typically studied the plume evolution in a pseudo-Lagrangian framework. Such analysis is often complicated by the fact that fire conditions change over time and by aircraft navigation artifacts, such as missing the dense plume in some crosswind transects (Supplementary Materials, section S1). Here, to investigate the O3 chemistry in a way that mitigates some of the challenges associated with fluctuations in fire emissions, we apply single transect analysis (STA) that examines the differences in the plume composition across each crosswind transect. Because of the high aerosol optical extinction in the center of large smoke plumes, the center experiences substantially lower actinic flux and photolysis rates than the edges at a given altitude. This provides a different extent of photochemical processing and, in particular, a range of time-integrated exposure of emissions to hydroxyl radicals (i.e., OH exposure) between the plume center and edges (Fig. 2A as an example). Since a single transect samples smoke emitted at similar times, the assumption of stationary fire conditions is often better satisfied in STA than traditional pseudo-Lagrangian analysis. Spatial variability in fire emissions and complex plume structure can still complicate the STA, so transects suitable for the STA are scrutinized by a set of stringent criteria (Supplementary Materials, section S4).

Fig. 2. Single transect analysis (STA) examines the differences in plume composition across individual transects of the wildfire plumes.

In (B), the flight track on 3 August 2019 is colored by OH exposure, which is lower in plume center than edges, as a result of high aerosol optical extinction in plume center. In (A), the dilution-corrected Ox formation (i.e., ΔOx/ΔCO) is illustrated in one near-field transect.

The STA is combined with a conceptual model (fig. S13 and Supplementary Materials, section S5) to investigate the daytime chemical closure of odd oxygen [Ox = O3 + NO2 + HNO3 + particulate nitrate + peroxyacylnitrates (PANs)]. Ox accounts for the interconversion between O3 and other Ox species (13). The instantaneous production rate of Ox can be expressed by the product of three terms: VOC reactivity (VOCR), OH concentration, and the fraction of peroxy radicals that react with NO (fRO2 + NO) (i.e., Eq. 1). VOCR is a condensed parameter summarizing several properties of individual VOCs (Eq.2), including the VOC concentration ([VOCi]), the reaction rate coefficient of the VOC with OH (kOH + VOCi), the number of peroxy radicals produced from the oxidization of each VOCi molecule to its first-generation closed-shell products (γi), and the alkylnitrate branching fraction of the VOCi-derived RO2 + NO reaction (αi). More details about VOCR are described in the Supplementary Materials, section S7.

Integrating Eq. 1 from the fresh (i.e., lowest OH exposure) to the aged portion (i.e., highest OH exposure) across each plume transect (i.e., Eq. 3) reflects the predicted Ox formation based on the observationally constrained VOCR, OH exposure, and RO2 chemistry. To account for dilution and background contributions, excess mixing ratios (i.e., the difference between smoke and background air, denoted as Δ in Eq. 3) were normalized to Δ[CO], which is a stable plume tracer. The predicted Ox production can be compared to the direct measurement of the same transect (i.e., left hand side of Eq. 3), providing a diagnostic of chemical closure, enabling constraints on the sources and sinks of Ox. This analysis is denoted as Ox chemical closure analysis.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

RESULTS

Variables influencing Ox formation

OH exposure

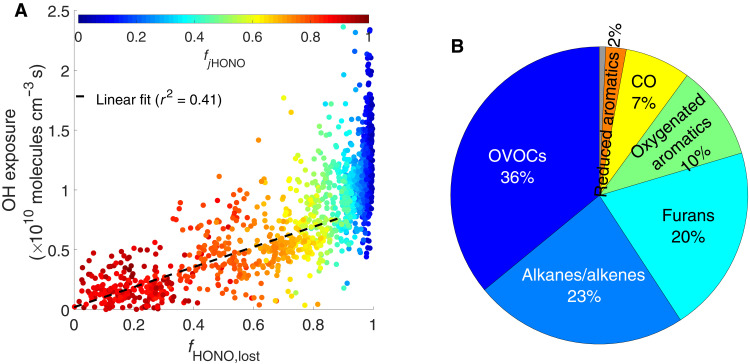

The OH exposure is estimated from the observed ratio of phenol to benzene (eq. S6 and Supplementary Materials, section S3), both of which are emitted in high yields in wildfires. Phenol reacts with OH ∼20 times faster than benzene, so their ratio serves as a measurement of photochemical processing in the absence of other substantial sinks or sources. The OH exposure is highly correlated with the nitrous acid (HONO) loss. Figure 3A shows the measurements on the 3 August 2019 flight as an example. Before 90% of HONO is lost, the OH exposure correlates with the lost HONO whose photolysis accounts for >50% of the total HOx production rate (Supplementary Materials, section S3). HONO photolysis is thus a critical OH source in wildfire plumes, consistent with a recent study by Peng et al. (14). After HONO is depleted, the OH exposure continues to increase because of the photolysis of O3 and aldehydes, albeit at a much slower rate, indicating lower [OH] (figs. S5 and S6).

Fig. 3. Production and fate of OH.

(A) shows that the OH exposure correlates with the amount of HONO loss [fHONO,lost = 1 − (ΔHONO/ΔCO)/(ΔHONO/ΔCO)max] for the 3 August 2019 Williams Flats Fire. The correlation indicates that OH is produced mainly by HONO photolysis in the near field. The color represents the relative contribution of HONO photolysis to total HOx production rate (denoted as fjHONO). (B) shows that OVOCs, alkanes/alkenes, and furans are the major contributors to total VOCR based on the average of transects included in the Ox chemical closure analysis.

VOC reactivity

The approximately 80 quantified VOCs are classified into seven structural categories. Figure 3B shows the relative contribution to total VOCR of each category averaged from transects included in the Ox chemical closure analysis. On average, oxygenated VOCs (OVOCs) are the largest contributor, together accounting for about one-third of VOCR. The OVOCs are predominantly small aldehydes, including formaldehyde and acetaldehyde (fig. S21). Alkanes and alkenes are the second largest contributors to VOCR. The historically overlooked furans also play an important role in wildfire plumes, contributing about one-fifth of VOCR, consistent with recent findings from lab studies (10, 15). While oxygenated aromatics, primarily guaiacol, catechol, and creosols, account for only one-tenth of total VOCR, their oxidation contributes a much larger fraction of the secondary organic aerosol (SOA) formed [∼60% as found in (16, 17)].

The relative importance of each VOC category to total VOCR changes with OH exposure. An example transect is shown in fig. S22. Many of the primary emissions, including alkenes, furans, and oxygenated aromatics, are rapidly oxidized, and their importance decreases with increasing OH exposure. In contrast, small aldehydes have substantial secondary sources, and, as a result, their contribution to the total VOCR increases over time. The VOCR of longer lived compounds, such as CO, remains relatively constant.

RO2 chemistry

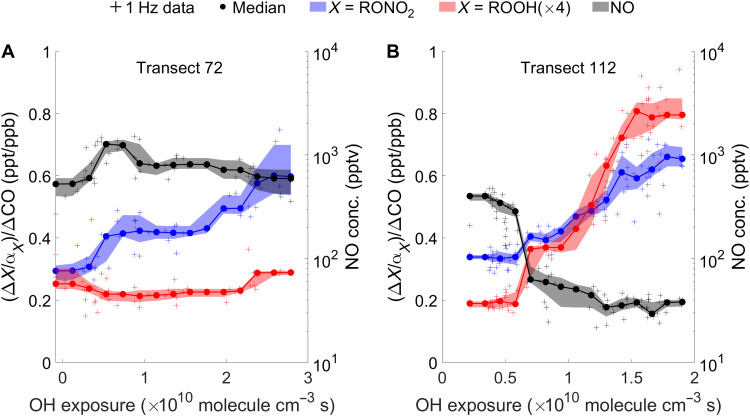

O3 is produced via the reaction of RO2 with NO. There are, however, a number of processes that can compete with this reaction. Thus, to understand Ox formation in wildfire plumes, knowing the RO2 fate is critical. With direct measurements of organic hydroperoxides (ROOH) and hydroxynitrates (RONO2) from the OH-initiated oxidation of small alkenes (i.e., ethene and propene), we are able to provide the first experimental constraint on RO2 fate in wildfire plumes. We probe the competition between RO2 + NO and RO2 + HO2 reactions and thereby estimate the fraction of RO2 that reacts with NO (fRO2 + NO). Figure 4 shows the evolution of propene-derived ROOH and RONO2 in two transects with different NO levels. In the transect shown in Fig. 4A, where [NO] is above 500 parts per trillion by volume (pptv), only RONO2 is produced, as the RO2 + NO reaction outruns the RO2 + HO2 reaction. In the transect shown in Fig. 4B, [NO] is below 500 pptv and reaches as low as 50 pptv. As a result of the low [NO], both ROOH and RONO2 are produced, suggesting that RO2 + HO2 and RO2 + NO reactions are competitive. H2O2, which is a product of HO2 + HO2 reaction, shows a similar trend as ROOH in these two transects (fig. S24).

Fig. 4. The measurements of ROOH and RONO2 from propene oxidation are used to diagnose the RO2 fate.

The ROOH is not produced in the transect with high [NO] (A) but produced in the transect with low [NO] (B). The signals of both RONO2 and ROOH are divided by the branching ratio of the corresponding RO2 reaction (i.e., α). The ROOH signal is multiplied by a factor of 4 to be shown in the same scale as RONO2. The shaded area represents the 25th to 75th percentile. ppb, parts per billion.

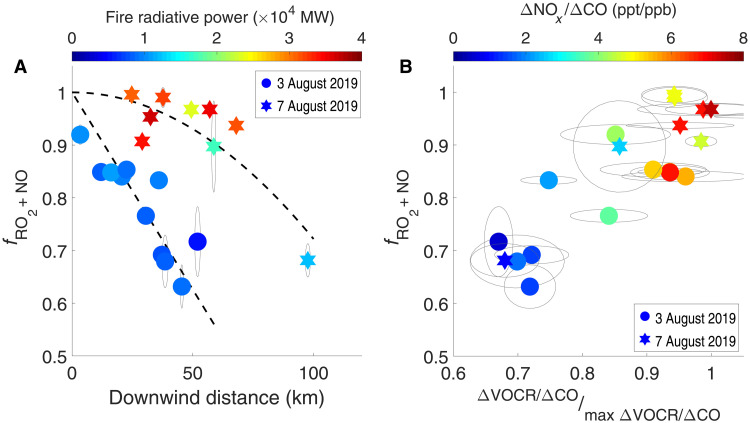

Measurement imprecision precludes the estimate of a pointwise fRO2 + NO across each transect, so we apply Eq. 4 to calculate transect-averaged fRO2 + NO using the transect-integrated production of RONO2 (i.e., PRONO2; eq. S29) and ROOH (i.e., PROOH; eq. S30). fRO2 + NO is calculated from both ethene and propene systems, and they are consistent within 10% (fig. S25). Figure 5A shows the evolution of fRO2 + NO for the Williams Flats Fire sampled on two different days. On both days, the fRO2 + NO decreases with downwind distance, illustrating the transition of RO2 fate from an RO2 + NO–dominated regime to a mixed regime with increasing importance of RO2 + HO2. The change rate of fRO2 + NO varies between fires. On 7 August 2019, the fRO2 + NO decreases from 1 to 0.7 after the smoke travels from 25 to 100 km. On 3 August 2019, the fRO2 + NO decreases more rapidly with downwind distance, and it reaches ∼60% at 45 km (estimated transport time ∼3 hours). Such difference is likely caused by fire strength and fuel consumption. The fire on 7 August 2019 is the most intense fire sampled during FIREX-AQ, with the fire radiative power (FRP) up to 4.4 × 104 MW and 72.3 km2 daily area burned. The fire on 3 August 2019 has lower intensity (i.e., peak FRP ∼1.5 × 104 MW) and smaller daily burned area (43.2 km2). It takes more time for the NOx concentration in intense fires to decline to a level where RO2 + HO2 reactions can become competitive. Note that over 90% of fires around the world have FRP <100 MW (18), so that the transition of fRO2 + NO can occur rapidly. More importantly, a large fraction of wildfire VOCs is oxidized in the mixed regime. As shown in Fig. 5B, for both fires, ∼70% of the VOCR remains when fRO2 + NO decreases to 0.6

| (4) |

Fig. 5. The RO2 fate transitions from an RO2 + NO–dominated regime to a mixed regime with increasing importance of RO2 + HO2.

(A) The fRO2 + NO decreases as smoke transports in the William Flats Fire sampled on 2 different days. The data points are colored by the fire radiative power (FRP) measured at the estimated time of smoke emission. (B) A large fraction of VOCs is oxidized in the mixed regime. The max ΔVOCR/ΔCO is represented by the average ΔVOCR/ΔCO of observations with the top 1% [CO] during the fire sample. The downwind distance is estimated on the basis of the aircraft position and the burned area. The dashed lines are provided as a visual aid. The ellipses represent the uncertainty range.

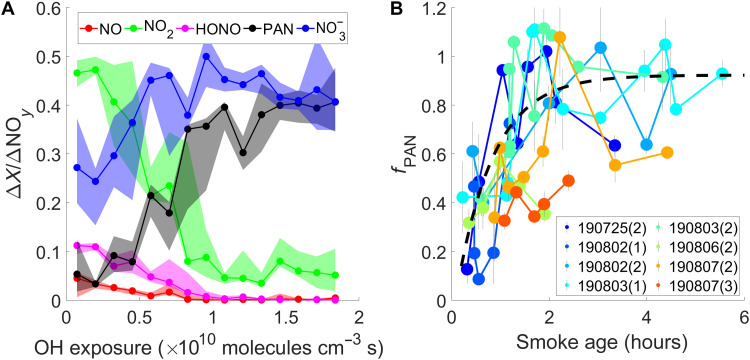

This regime transition is a result of [NOx] decrease, which is caused primarily by dilution with ambient air and by chemical loss of NOx. The major NOx oxidation products are PAN and nitrate ( = HNO3 + particulate nitrate). Together, they account for nearly all of NOx oxidation products, NOz (= NOy − NOx− HONO) (fig. S27). The fractions of PAN and nitrate in total reactive oxidized nitrogen (NOy) increase with OH exposure as a result of NOx conversion (Fig. 6A), consistent with previous studies (6, 19, 20).

Fig. 6. The evolution of the partitioning of NOy species.

(A) shows measurements of the 3 August 2019 Williams Flats Fire. As smoke ages, the NOx and HONO emitted from fires are converted to PAN and NO3−. (B) shows that the fraction of NOx loss to PAN (fPAN) across each transect increases with smoke age, which results from evolving CH3CHO/NO2 as discussed in the text. Each data point represents one transect, and the transects from the same fire sampling patterns have the same color. The black line is provided as a visual aid. The numbers in parentheses represent the index of a set of crosswind transects in a flight.

Because nitrate is a permanent NOx sink but PAN is a temporary NOx reservoir, the NOx loss pathways affect O3 formation in the long-range transport of wildfire plumes. To investigate the competition between NOx loss pathways, we use STA. ΔPAN/ΔCO and ΔNOz/ΔCO correlation slopes (fig. S28) give the relative fraction of NOx loss to PAN (denoted as fPAN) as the smoke chemically evolved from the photochemical condition in plume center to that in plume edge across individual transects. fPAN is different from ΔPAN/ΔNOz, as the latter is an accumulative property that depends on initial emissions and the integral of NOx loss over time. Figure 6B shows fPAN for each transect of several fires as a function of smoke age. Despite fire-to-fire variability, fPAN is 0.2 to 0.4 at a smoke age of 0.5 hour and rapidly increases to 0.8 to 1 at 2 hours. This trend suggests that the major NOx oxidation product transitions from to PAN after ∼2 hours of transport.

This transition is mainly driven by the change in [CH3CHO]/[NO2], which increases with smoke age (fig. S30) and reflects the fact that NO2 is chemically lost to other NOy species, but CH3CHO has substantial production from VOC oxidation. Larger [CH3CHO]/[NO2] favors the PAN formation by producing more acetyl peroxy radical (Supplementary Materials, section S8). Therefore, fire conditions that affect the [CH3CHO]/[NO2], or broadly the [VOCs]/[NOx], alter the partitioning between NOy species and, as a result, downwind O3 formation. Figure S33 shows that the plateau value of ΔPAN/ΔNOy from different fires negatively correlates with the modified combustion efficiency (MCE). This observation is consistent with the finding from STA that higher emission ratios of [CH3CHO]/[NO2] (associated with lower MCE; fig. S38) favors NOx loss to PAN.

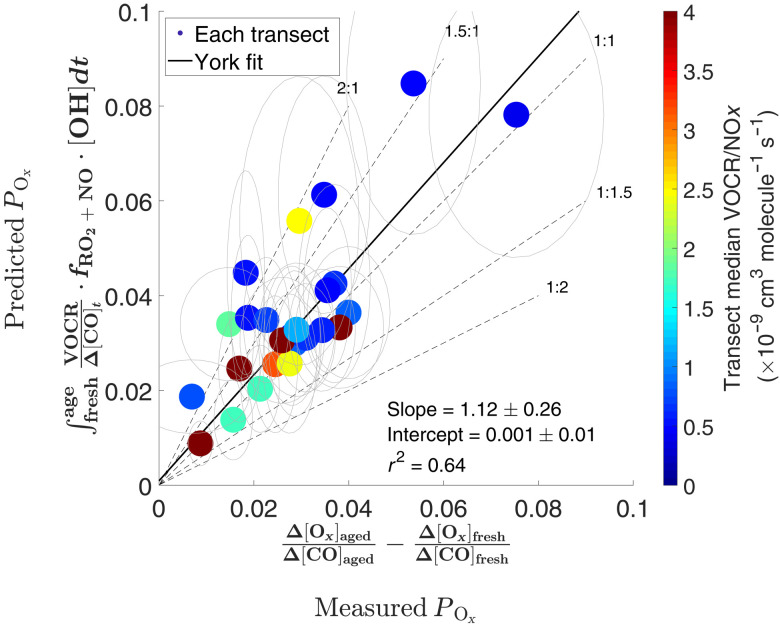

Ox chemical closure analysis

We now return to the conceptual model (Eq.3) to test the chemical closure of Ox in wildfire plumes. The Ox production (denoted as POx) across each transect is predicted on the basis of the three key chemical variables: OH exposure, VOCR, and RO2 fate. Then, this prediction is compared to the measured POx calculated as a sum of the measured individual Ox species (Eq.3). On the basis of a set of stringent criteria (Supplementary Materials, section S4), 25 transects, for which the POx and RO2 fate can be quantified with high confidence, are selected for this comparison. As shown in Fig. 7, the correlation between the observed and predicted POx is quite strong (r2 = 0.64). On average, the predicted POx is higher than the measured POx by 12%, well within the analysis and measurement uncertainties (Supplementary Materials, section S9). Overall, the use of the conceptual model and the comprehensive measurements of VOCs in FIREX-AQ enables remarkably good prediction of Ox production. Such agreement suggests that the majority of VOCs contributing to Ox formation are quantified during FIREX-AQ, at least in the early stage of the wildfire plumes. This provides confidence in the characterization of fire emissions during FIREX-AQ, which will serve as a foundation for future use in chemical transport models (CTMs). Furthermore, as the conceptual model solely based on gas phase chemistry is sufficient to account for the measured Ox production here, we suggest that the role of heterogeneous loss of O3 and HO2 is likely minor in wildfire plumes, a hypothesis often invoked when models overpredict the measured O3 (5, 21).

Fig. 7. The predicted and measured Ox production show reasonable agreement.

The ellipses represent the uncertainty range (Supplementary Materials, section S9). The slope and intercepts are obtained from a York fit.

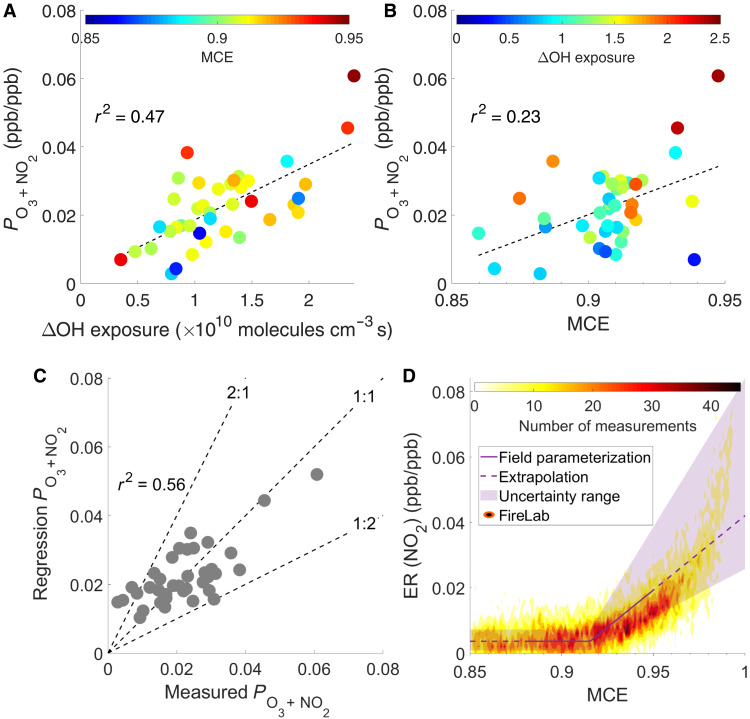

Parameterization of the O3 + NO2 production

The chemistry and dynamics described in this study occur on spatial scales smaller than those used in even modestly high-resolution CTMs. Thus, there is a need to parameterize the near-field chemistry to properly capture the oxidation chemistry. Here, we focus on O3 and NO2, as they are critical air pollutants. The production of O3 and NO2 across individual transects, which is represented by the difference in Δ(O3 + NO2)/ΔCO between aged and fresh smoke, is denoted as PO3 + NO2. PO3 + NO2 ranges from 0 to 0.06 and exhibits a positive relationship with the span of OH exposure (ΔOH exposure) across individual transects (r2 = 0.47; Fig. 8A). This trend implies more O3 + NO2 production as plumes age in the near field, consistent with previous observations (5). In addition to OH exposure, the PO3 + NO2 positively correlates with MCE (r2 = 0.23; Fig. 8B). Higher MCE indicates more flaming combustion, which usually leads to higher NOx emissions and lower VOC emissions, together leading to a higher NOx/VOCR (5, 22, 23). The PO3 + NO2 does increase with NOx/VOCR, as shown in fig. S34. Overall, the positive relationship between PO3 + NO2 and MCE suggests that the formation of O3 + NO2 in fresh wildfires in the western United States is generally NOx limited.

Fig. 8. Parameterization of the O3 + NO2 production.

The measured production of O3 + NO2 (PO3 + NO2) across individual transects exhibits positive correlation with the span of OH exposure (ΔOH exposure) and MCE, as shown in (A) and (B), respectively. Thirty-nine transects are selected for this analysis (Supplementary Materials, section S4). (C) Comparison between predicted and measured PO3 + NO2 for individual transects. (D) The emission ratios (ERs) of NO2 to CO derived from the field [i.e., a + b×max(0,MCE-c)] and measured in the 2016 FIREX FireLab are plotted as a function of MCE.

As the O3 + NO2 formation depends on several variables, we develop a statistical model based on multivariate adaptive regression splines (24) to attribute such dependence (Supplementary Materials, section S10). We examine the relationship between PO3 + NO2 of each transect and a number of variables (MCE, ΔOH exposure, VOCR, NOx/VOCR, and RO2 fate) using stepwise forward selection. The final model form is Eq. 5 [the units of PO3 + NO2 and OH exposure are parts per billion (ppb)/ppb and 1010 molecules cm−3 s, respectively]. The model captures 56% of the measurement variance (Fig. 8C)

| (5) |

The terms a + b × max(0, MCE − c) in Eq. 5 are interpreted as the MCE-dependent primary emission ratio (ER) of NO2 to CO, i.e., ER(NO2), because O3 + NO2 is essentially all NO2 when there is no chemical aging of fire emissions. To examine this interpretation, we compare the field-derived ER(NO2) to that measured in the FIREX FireLab 2016 study, where fuel complexes important for western U.S. ecosystems were burned. Figure 8D compiles the ER(NO2) from lab fuel types that are relevant to FIREX-AQ fires (table S7). The empirical parameterization reasonably predicts the nearly constant ER(NO2) when MCE is <0.92 and slightly overpredicts the rising ER(NO2) as MCE increases above 0.92. One factor that complicates this comparison is the fuel dependence of ER(NO2), which shows larger variability as MCE increases. In comparison to individual fuel types (fig. S36), the empirical parameterization reasonably predicts the ER(NO2) of douglas fir, Engelmann spruce, and subalpine fir, but slightly overpredicts for fuels like ponderosa pine and manzanita. Among all 253 transects in FIREX-AQ, more than 90% of transects have MCE less than 0.92 (fig. S2), a range where the field-derived parameterization performs accurately, and the ER(NO2) is largely independent of fuel type (fig. S36). Therefore, this field-derived parameterization is a reasonable approximation of the subgrid scale O3 + NO2 production for CTMs without an accurate emissions inventory and fuel characteristics.

The other term in Eq. 5 (d × OH exposure) is interpreted as the O3 + NO2 formation during plume aging. This linear dependence of O3 + NO2 production on OH exposure is likely confined to the near field of wildfire plumes (i.e., maximum OH exposure used to constrain the parameterization is 2.5×1010 molecules cm−3 s, which is roughly 7 hours transport time) before the RO2 chemistry transitions to HO2-dominated reactivity. We compile the literature values of ΔO3/ΔCO from boreal and temperate wildfires over a wide range of plume ages in fig. S35 and find that the aircraft-based observations of ΔO3/ΔCO in the free troposphere typically reach a maximum value of 0.1 at 3 to 5 days downwind, which is only about twice the value after 7 hours of aging observed in this study. The ΔO3/ΔCO is relatively constant afterward and even shows a decreasing trend in some plumes that are ∼10 days old. This observation suggests that the major fraction of O3 in wildfire plumes in the free troposphere is produced in the near field, consistent with the analysis above that the wildfire plumes quickly run out of NOx and then the reaction of HO2 with RO2 efficiently competes with NO.

DISCUSSION

Uncertainties in emissions characterization and oxidation chemistry are long-standing challenges in understanding Ox production in wildfire plumes. The agreement between the measured and predicted Ox production in this study indicates that the oxidation of VOCs has been accurately captured by the comprehensive suite of analytical instruments deployed here. This chemical closure provides confidence in diagnosing the key chemical variables influencing Ox formation. These variables undergo rapid transition in chemical regimes. HONO photolysis is the major source of OH in the near field. Once the primary HONO is consumed, the rate of photochemistry in the plume decreases quickly. Ox formation also slows because of the changing fate of RO2 radicals. Given the high VOC/NOx produced in the fire, the RO2 fate transitions within a few hours from an RO2 + NO–dominated regime to a mixed regime with increasing importance of the RO2 + HO2 reaction. A large fraction of VOCs is oxidized in the mixed regime. The changing RO2 fate affects not only Ox formation but also SOA formation. To estimate SOA formation in wildfire plumes, previous studies have used high NOx SOA yields from chamber experiments (16, 17). The SOA yields of aromatics, which are critical SOA precursors in wildfire plumes, are generally higher under low NOx condition than high NOx condition (25, 26). Therefore, the estimated SOA formation in some previous studies may be biased low if the rapid transition to low NOx chemistry is not represented accurately.

The O3 chemistry in temperate wildfire emissions is generally in the NOx-limited regime. Thus, fire conditions that influence the NOx emissions and sinks critically determine the O3 formation. Wildfires with higher MCE have higher emission ratios of HONO and NOx, which tend to increase O3 formation. On the other hand, higher MCE is associated with lower CH3CHO/NOx, which tends to decrease the fraction of PAN in NOy and the downwind O3 production. Given that the high concentrations of VOCs are still present in the aged plumes, O3 formation will be enhanced when the wildfire smoke is provided with additional NOx, either internally from the PAN decomposition when plumes descend to higher temperature (27) or externally from mixing with NOx-rich urban plumes (28) or lightning-derived NOx (29).

The rapid transition of O3 chemistry within wildfire plumes highlights a known issue in CTMs, which simulate O3 formation by generally uniformly mixing wildfire emissions into a few large grid cells. This treatment introduces substantial bias in predicting O3 formation. Representing the near-field subgrid plume evolution using a field-constrained parameterization such as that developed here and subsequently diluting the chemically processed emissions into a larger grid cell may be an efficient approach to improve the prediction accuracy of CTMs. The amount of O3 produced in these underresolved plumes can be substantial. For example, using a representative value of Δ(O3 + NO2)/ΔCO in the near field (i.e., 0.045) and the estimated CO flux from wildfires averaged from 2011 to 2015 in the western United States [i.e., 5240 ± 2240 Gg year−1 (30)], we estimate that O3 produced in wildfire plumes can sustain a 3-ppb enhancement in boundary layer O3 concentration over the western United States during fire season (Supplementary Materials, section S10). The episodic nature of wildfires can result in more severe impacts on the occurrence of O3 exceedances (5).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Descriptions of the FIREX-AQ campaign and instrumentation; calculation of OH exposure, VOCR, and RO2 fate; criteria of transect selection for STA; conceptual model to investigate Ox chemistry and associated uncertainty analysis; statistical model to estimate the Ox background level; and parameterization of the O3 + NO2 production can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

We thank P. P. Papin for providing the background picture in Fig. 1 and R. Schwantes and M. Bela for helpful discussions. A.W. acknowledges support from ASAP-FFG-BMVIT and thanks T. Mikoviny and L. Tomsche for field support.

Funding: L.X., K.T.V., H.A., J.D.C., and P.O.W. acknowledge NASA grants 80NSSC18K0660 and 80NSSC21K1704. I.B., M.M.C., G.I.G., A.L., J.A.N., J.P., P.S.R., M.A.R., and C.C.W. acknowledge the NOAA Cooperative Agreement with CIRES, NA17OAR4320101. G.M.W., T.F.H., J.M.S., J. Liao, and R.A.H. acknowledge NASA Tropospheric Composition and NOAA AC4 grant NA17OAR4310004. R.J.Y. and V.S. acknowledge NOAA grant NA16OAR4310100. A.F., D.R., J.W., and P.W. acknowledge NASA grant 80NSSC18K0628. D.A.P. acknowledges NASA grant 80HQTR18T0063. S.R.H. and K.U. acknowledge NASA grant 80NSSC18K0638. A.J.S. and E.M.G. acknowledge NASA grant 80NSSC18K0685. H.G., P.C.-J., and J.L.J. acknowledge NASA grants 80NSSC18K0630 and 80NSSC19K0124. F.P. acknowledges support from the EU (#674911, IMPACT ITN). C.D.H. acknowledges NASA grant 80NSSC18K0625.

Author contributions: L.X. and P.O.W. designed the research. J.H.C., C.W., and D.A.P. designed the flight plans. L.X., J.D.C., K.T.V., H.A., P.O.W., I.B., S.S.B., P.C.-J., M.M.C., J.P.D., G.S.D., A.F., J.B.G., G.I.G., H.G., J.W.H., S.R.H, H.A.H., T.F.H., R.A.H., C.D.H., L.G.H., E.M.G., J.L.J., A.L.,Y.R.L., J. Liao, J. Lindaas, J.A.N., J.B.N., J.P., F.P., D.R., P.S.R., M.A.R., A.W.R., T.B.R., K.S., V.S., T.S., A.J.S., J.M.S., D.J.T., K.U., P.R.V., J.W., C.W., R.A.W., P.W., A.W., G.M.W., and C.C.W. conducted measurements. L.X. analyzed the data. L.X., P.O.W., and J.D.C. wrote the paper. R.J.Y. provided critical context on fire chemistry.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. FIREX-AQ data are available at www-air.larc.nasa.gov/cgi-bin/ArcView/firexaq.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Supplementary Text

Figs. S1 to S38

Tables S1 to S7

References

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Akagi S. K., Yokelson R. J., Wiedinmyer C., Alvarado M. J., Reid J. S., Karl T., Crounse J. D., Wennberg P. O., Emission factors for open and domestic biomass burning for use in atmospheric models. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 4039–4072 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreae M. O., Emission of trace gases and aerosols from biomass burning–An updated assessment. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 8523–8546 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Y., Mickley L. J., Liu P., Kaplan J. O., Trends and spatial shifts in lightning fires and smoke concentrations in response to 21st century climate over the national forests and parks of the western United States. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 8827–8838 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaffe D. A., O’Neill S. M., Larkin N. K., Holder A. L., Peterson D. L., Halofsky J. E., Rappold A. G., Wildfire and prescribed burning impacts on air quality in the United States. J. Air Waste Manage. Assoc. 70, 583–615 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaffe D. A., Wigder N. L., Ozone production from wildfires: A critical review. Atmos. Environ. 51, 1–10 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akagi S. K., Craven J. S., Taylor J. W., McMeeking G. R., Yokelson R. J., Burling I. R., Urbanski S. P., Wold C. E., Seinfeld J. H., Coe H., Alvarado M. J., Weise D. R., Evolution of trace gases and particles emitted by a chaparral fire in California. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 1397–1421 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alvarado M. J., Prinn R. G., Formation of ozone and growth of aerosols in young smoke plumes from biomass burning: 1. Lagrangian parcel studies. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 114, D09306 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alvarado M. J., Wang C., Prinn R. G., Formation of ozone and growth of aerosols in young smoke plumes from biomass burning: 2. Three-dimensional Eulerian studies. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 114, (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Müller M., Anderson B. E., Beyersdorf A. J., Crawford J. H., Diskin G. S., Eichler P., Fried A., Keutsch F. N., Mikoviny T., Thornhill K. L., Walega J. G., Weinheimer A. J., Yang M., Yokelson R. J., Wisthaler A., In situ measurements and modeling of reactive trace gases in a small biomass burning plume. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 3813–3824 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coggon M. M., Lim C. Y., Koss A. R., Sekimoto K., Yuan B., Gilman J. B., Hagan D. H., Selimovic V., Zarzana K. J., Brown S. S., Roberts J. M., Müller M., Yokelson R., Wisthaler A., Krechmer J. E., Jimenez J. L., Cappa C., Kroll J. H., de Gouw J., Warneke C., OH chemistry of non-methane organic gases (NMOGs) emitted from laboratory and ambient biomass burning smoke: Evaluating the influence of furans and oxygenated aromatics on ozone and secondary NMOG formation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 14875–14899 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robinson M. A., Decker Z. C. J., Barsanti K. C., Coggon M. M., Flocke F. M., Franchin A., Fredrickson C. D., Gilman J. B., Gkatzelis G. I., Holmes C. D., Lamplugh A., Lavi A., Middlebrook A. M., Montzka D. M., Palm B. B., Peischl J., Pierce B., Schwantes R. H., Sekimoto K., Selimovic V., Tyndall G. S., Thornton J. A., van Rooy P., Warneke C., Weinheimer A. J., Brown S. S., Variability and time of day dependence of ozone photochemistry in western wildfire plumes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 10280–10290 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young P. J., Naik V., Fiore A. M., Gaudel A., Guo J., Lin M. Y., Neu J. L., Parrish D. D., Rieder H. E., Schnell J. L., Tilmes S., Wild O., Zhang L., Ziemke J., Brandt J., Delcloo A., Doherty R. M., Geels C., Hegglin M. I., Hu L., Im U., Kumar R., Luhar A., Murray L., Plummer D., Rodriguez J., Saiz-Lopez A., Schultz M. G., Woodhouse M. T., Zeng G., Tropospheric Ozone Assessment Report: Assessment of global-scale model performance for global and regional ozone distributions, variability, and trends. Elementa 6, 10 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y., Logan J. A., Jacob D. J., Global simulation of tropospheric O3-NOx-hydrocarbon chemistry: 2. Model evaluation and global ozone budget. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 103, 10727–10755 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peng Q., Palm B. B., Melander K. E., Lee B. H., Hall S. R., Ullmann K., Campos T., Weinheimer A. J., Apel E. C., Hornbrook R. S., Hills A. J., Montzka D. D., Flocke F., Hu L., Permar W., Wielgasz C., Lindaas J., Pollack I. B., Fischer E. V., Bertram T. H., Thornton J. A., HONO emissions from western U.S. wildfires provide dominant radical source in fresh wildfire smoke. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 5954–5963 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koss A. R., Sekimoto K., Gilman J. B., Selimovic V., Coggon M. M., Zarzana K. J., Yuan B., Lerner B. M., Brown S. S., Jimenez J. L., Krechmer J., Roberts J. M., Warneke C., Yokelson R. J., de Gouw J., Non-methane organic gas emissions from biomass burning: Identification, quantification, and emission factors from PTR-ToF during the FIREX 2016 laboratory experiment. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 3299–3319 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akherati A., He Y., Coggon M. M., Koss A. R., Hodshire A. L., Sekimoto K., Warneke C., de Gouw J., Yee L., Seinfeld J. H., Onasch T. B., Herndon S. C., Knighton W. B., Cappa C. D., Kleeman M. J., Lim C. Y., Kroll J. H., Pierce J. R., Jathar S. H., Oxygenated aromatic compounds are important precursors of secondary organic aerosol in biomass-burning emissions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 8568–8579 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palm B. B., Peng Q., Fredrickson C. D., Lee B. H., Garofalo L. A., Pothier M. A., Kreidenweis S. M., Farmer D. K., Pokhrel R. P., Shen Y., Murphy S. M., Permar W., Hu L., Campos T. L., Hall S. R., Ullmann K., Zhang X., Flocke F., Fischer E. V., Thornton J. A., Quantification of organic aerosol and brown carbon evolution in fresh wildfire plumes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117, 29469–29477 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ichoku C., Giglio L., Wooster M. J., Remer L. A., Global characterization of biomass-burning patterns using satellite measurements of fire radiative energy. Remote Sens. Environ. 112, 2950–2962 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Juncosa Calahorrano J. F., Lindaas J., O’Dell K., Palm B. B., Peng Q., Flocke F., Pollack I. B., Garofalo L. A., Farmer D. K., Pierce J. R., Collett J. L. Jr., Weinheimer A., Campos T., Hornbrook R. S., Hall S. R., Ullmann K., Pothier M. A., Apel E. C., Permar W., Hu L., Hills A. J., Montzka D., Tyndall G., Thornton J. A., Fischer E. V., Daytime oxidized reactive nitrogen partitioning in western U.S. wildfire smoke plumes. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126, e2020JD033484 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alvarado M. J., Logan J. A., Mao J., Apel E., Riemer D., Blake D., Cohen R. C., Min K. E., Perring A. E., Browne E. C., Wooldridge P. J., Diskin G. S., Sachse G. W., Fuelberg H., Sessions W. R., Harrigan D. L., Huey G., Liao J., Case-Hanks A., Jimenez J. L., Cubison M. J., Vay S. A., Weinheimer A. J., Knapp D. J., Montzka D. D., Flocke F. M., Pollack I. B., Wennberg P. O., Kurten A., Crounse J., Clair J. M. S., Wisthaler A., Mikoviny T., Yantosca R. M., Carouge C. C., le Sager P., Nitrogen oxides and PAN in plumes from boreal fires during ARCTAS-B and their impact on ozone: An integrated analysis of aircraft and satellite observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 9739–9760 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Konovalov I. B., Beekmann M., D’Anna B., George C., Significant light induced ozone loss on biomass burning aerosol: Evidence from chemistry-transport modeling based on new laboratory studies. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L17807 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yokelson R. J., Christian T. J., Karl T. G., Guenther A., The tropical forest and fire emissions experiment: Laboratory fire measurements and synthesis of campaign data. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 8, 3509–3527 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roberts J. M., Stockwell C. E., Yokelson R. J., de Gouw J., Liu Y., Selimovic V., Koss A. R., Sekimoto K., Coggon M. M., Yuan B., Zarzana K. J., Brown S. S., Santin C., Doerr S. H., Warneke C., The nitrogen budget of laboratory-simulated western US wildfires during the FIREX 2016 FireLab study. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 8807–8826 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedman J. H., Multivariate adaptive regression splines. Ann. Stat. 19, 1–67 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ng N. L., Kroll J. H., Chan A. W. H., Chhabra P. S., Flagan R. C., Seinfeld J. H., Secondary organic aerosol formation from m-xylene, toluene, and benzene. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 7, 3909–3922 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yee L. D., Kautzman K. E., Loza C. L., Schilling K. A., Coggon M. M., Chhabra P. S., Chan M. N., Chan A. W. H., Hersey S. P., Crounse J. D., Wennberg P. O., Flagan R. C., Seinfeld J. H., Secondary organic aerosol formation from biomass burning intermediates: Phenol and methoxyphenols. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 8019–8043 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Val Martín M., Honrath R. E., Owen R. C., Pfister G., Fialho P., Barata F., Significant enhancements of nitrogen oxides, black carbon, and ozone in the North Atlantic lower free troposphere resulting from North American boreal wildfires. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 111, D23S60 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brey S. J., Fischer E. V., Smoke in the city: How often and where does smoke impact summertime ozone in the United States? Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 1288–1294 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Apel E. C., Hornbrook R. S., Hills A. J., Blake N. J., Barth M. C., Weinheimer A., Cantrell C., Rutledge S. A., Basarab B., Crawford J., Diskin G., Homeyer C. R., Campos T., Flocke F., Fried A., Blake D. R., Brune W., Pollack I., Peischl J., Ryerson T., Wennberg P. O., Crounse J. D., Wisthaler A., Mikoviny T., Huey G., Heikes B., O’Sullivan D., Riemer D. D., Upper tropospheric ozone production from lightning NOx-impacted convection: Smoke ingestion case study from the DC3 campaign. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 120, 2505–2523 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu X., Huey L. G., Yokelson R. J., Selimovic V., Simpson I. J., Müller M., Jimenez J. L., Campuzano-Jost P., Beyersdorf A. J., Blake D. R., Butterfield Z., Choi Y., Crounse J. D., Day D. A., Diskin G. S., Dubey M. K., Fortner E., Hanisco T. F., Hu W., King L. E., Kleinman L., Meinardi S., Mikoviny T., Onasch T. B., Palm B. B., Peischl J., Pollack I. B., Ryerson T. B., Sachse G. W., Sedlacek A. J., Shilling J. E., Springston S., St. Clair J. M., Tanner D. J., Teng A. P., Wennberg P. O., Wisthaler A., Wolfe G. M., Airborne measurements of western U.S. wildfire emissions: Comparison with prescribed burning and air quality implications. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 122, 6108–6129 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wiggins E. B., Soja A. J., Gargulinski E., Halliday H. S., Pierce R. B., Schmidt C. C., Nowak J. B., Di Gangi J. P., Diskin G. S., Katich J. M., Perring A. E., Schwarz J. P., Anderson B. E., Chen G., Crosbie E. C., Jordan C., Robinson C. E., Sanchez K. J., Shingler T. J., Shook M., Thornhill K. L., Winstead E. L., Ziemba L. D., Moore R. H., High temporal resolution satellite observations of fire radiative power reveal link between fire behavior and aerosol and gas emissions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL090707 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garofalo L. A., Pothier M. A., Levin E. J. T., Campos T., Kreidenweis S. M., Farmer D. K., Emission and evolution of submicron organic aerosol in smoke from wildfires in the western United States. ACS Earth Space Chem. 3, 1237–1247 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ryerson T. B., Huey L. G., Knapp K., Neuman J. A., Parrish D. D., Sueper D. T., Fehsenfeld F. C., Design and initial characterization of an inlet for gas-phase NOymeasurements from aircraft. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 104, 5483–5492 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luria M., Valente R. J., Tanner R. L., Gillani N. V., Imhoff R. E., F. Mueller S., Olszyna K. J., Meagher J. F., The evolution of photochemical smog in a power plant plume. Atmos. Environ. 33, 3023–3036 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ryerson T. B., Trainer M., Holloway J. S., Parrish D. D., Huey L. G., Sueper D. T., Frost G. J., Donnelly S. G., Schauffler S., Atlas E. L., Kuster W. C., Goldan P. D., Hübler G., Meagher J. F., Fehsenfeld F. C., Observations of ozone formation in power plant plumes and implications for ozone control strategies. Science 292, 719–723 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Selimovic V., Yokelson R. J., Warneke C., Roberts J. M., de Gouw J., Reardon J., Griffith D. W. T., Aerosol optical properties and trace gas emissions by PAX and OP-FTIR for laboratory-simulated western US wildfires during FIREX. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 2929–2948 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stein A. F., Draxler R. R., Rolph G. D., Stunder B. J. B., Cohen M. D., Ngan F., NOAA’s HYSPLIT atmospheric transport and dispersion modeling system. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 96, 2059–2077 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rollins A. W., Rickly P. S., Gao R. S., Ryerson T. B., Brown S. S., Peischl J., Bourgeois I., Single-photon laser-induced fluorescence detection of nitric oxide at sub-parts-per-trillion mixing ratios. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 13, 2425–2439 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 39.St. Clair J. M., Swanson A. K., Bailey S. A., Hanisco T. F., CAFE: A new, improved nonresonant laser-induced fluorescence instrument for airborne in situ measurement of formaldehyde. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 12, 4581–4590 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Min K. E., Washenfelder R. A., Dubé W. P., Langford A. O., Edwards P. M., Zarzana K. J., Stutz J., Lu K., Rohrer F., Zhang Y., Brown S. S., A broadband cavity enhanced absorption spectrometer for aircraft measurements of glyoxal, methylglyoxal, nitrous acid, nitrogen dioxide, and water vapor. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 9, 423–440 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Veres P. R., Neuman J. A., Bertram T. H., Assaf E., Wolfe G. M., Williamson C. J., Weinzierl B., Tilmes S., Thompson C. R., Thames A. B., Schroder J. C., Saiz-Lopez A., Rollins A. W., Roberts J. M., Price D., Peischl J., Nault B. A., Møller K. H., Miller D. O., Meinardi S., Li Q., Lamarque J. F., Kupc A., Kjaergaard H. G., Kinnison D., Jimenez J. L., Jernigan C. M., Hornbrook R. S., Hills A., Dollner M., Day D. A., Cuevas C. A., Campuzano-Jost P., Burkholder J., Bui T. P., Brune W. H., Brown S. S., Brock C. A., Bourgeois I., Blake D. R., Apel E. C., Ryerson T. B., Global airborne sampling reveals a previously unobserved dimethyl sulfide oxidation mechanism in the marine atmosphere. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 4505–4510 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cazorla M., Wolfe G. M., Bailey S. A., Swanson A. K., Arkinson H. L., Hanisco T. F., A new airborne laser-induced fluorescence instrument for in situ detection of formaldehyde throughout the troposphere and lower stratosphere. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 8, 541–552 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Richter D., Weibring P., Walega J. G., Fried A., Spuler S. M., Taubman M. S., Compact highly sensitive multi-species airborne mid-IR spectrometer. Appl. Phys. B 119, 119–131 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liao J., Wolfe G. M., Hannun R. A., St. Clair J. M., Hanisco T. F., Gilman J. B., Lamplugh A., Selimovic V., Diskin G. S., Nowak J. B., Halliday H. S., DiGangi J. P., Hall S. R., Ullmann K., Holmes C. D., Fite C. H., Agastra A., Ryerson T. B., Peischl J., Bourgeois I., Warneke C., Coggon M. M., Gkatzelis G. I., Sekimoto K., Fried A., Richter D., Weibring P., Apel E. C., Hornbrook R. S., Brown S. S., Womack C. C., Robinson M. A., Washenfelder R. A., Veres P. R., Neuman J. A., Formaldehyde evolution in U.S. wildfire plumes during FIREX-AQ. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 2021, 1–38 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crounse J. D., McKinney K. A., Kwan A. J., Wennberg P. O., Measurement of gas-phase hydroperoxides by chemical ionization mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 78, 6726–6732 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huey L. G., Measurement of trace atmospheric species by chemical ionization mass spectrometry: Speciation of reactive nitrogen and future directions. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 26, 166–184 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.DeCarlo P. F., Kimmel J. R., Trimborn A., Northway M. J., Jayne J. T., Aiken A. C., Gonin M., Fuhrer K., Horvath T., Docherty K. S., Worsnop D. R., Jimenez J. L., Field-deployable, high-resolution, time-of-flight aerosol mass spectrometer. Anal. Chem. 78, 8281–8289 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Canagaratna M. R., Jayne J. T., Jimenez J. L., Allan J. D., Alfarra M. R., Zhang Q., Onasch T. B., Drewnick F., Coe H., Middlebrook A., Delia A., Williams L. R., Trimborn A. M., Northway M. J., DeCarlo P. F., Kolb C. E., Davidovits P., Worsnop D. R., Chemical and microphysical characterization of ambient aerosols with the aerodyne aerosol mass spectrometer. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 26, 185–222 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guo H., Campuzano-Jost P., Nault B. A., Day D. A., Schroder J. C., Kim D., Dibb J. E., Dollner M., Weinzierl B., Jimenez J. L., The importance of size ranges in aerosol instrument intercomparisons: a case study for the Atmospheric Tomography Mission. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 14, 3631–3655 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lerner B. M., Gilman J. B., Aikin K. C., Atlas E. L., Goldan P. D., Graus M., Hendershot R., Isaacman-VanWertz G. A., Koss A., Kuster W. C., Lueb R. A., McLaughlin R. J., Peischl J., Sueper D., Ryerson T. B., Tokarek T. W., Warneke C., Yuan B., de Gouw J. A., An improved, automated whole air sampler and gas chromatography mass spectrometry analysis system for volatile organic compounds in the atmosphere. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 10, 291–313 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Gouw J., Warneke C., Measurements of volatile organic compounds in the earth's atmosphere using proton-transfer-reaction mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 26, 223–257 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Müller M., Mikoviny T., Feil S., Haidacher S., Hanel G., Hartungen E., Jordan A., Märk L., Mutschlechner P., Schottkowsky R., Sulzer P., Crawford J. H., Wisthaler A., A compact PTR-ToF-MS instrument for airborne measurements of volatile organic compounds at high spatiotemporal resolution. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 7, 3763–3772 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sachse G. W., Hill G. F., Wade L. O., Perry M. G., Fast-response, high-precision carbon monoxide sensor using a tunable diode laser absorption technique. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 92, 2071 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shetter R. E., Müller M., Photolysis frequency measurements using actinic flux spectroradiometry during the PEM-Tropics mission: Instrumentation description and some results. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 104, 5647–5661 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 55.G. Diskin, J. Podolske, G. Sachse, T. Slate, Open-path airborne tunable diode laser hygrometer, vol. 4817 of International Symposium on Optical Science and Technology (SPIE, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parrish D. D., Stohl A., Forster C., Atlas E. L., Blake D. R., Goldan P. D., Kuster W. C., de Gouw J. A., Effects of mixing on evolution of hydrocarbon ratios in the troposphere. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 112, D10S34 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 57.McKeen S. A., Liu S. C., Hydrocarbon ratios and photochemical history of air masses. Geophys. Res. Lett. 20, 2363–2366 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Gouw J. A., Brock C. A., Atlas E. L., Bates T. S., Fehsenfeld F. C., Goldan P. D., Holloway J. S., Kuster W. C., Lerner B. M., Matthew B. M., Middlebrook A. M., Onasch T. B., Peltier R. E., Quinn P. K., Senff C. J., Stohl A., Sullivan A. P., Trainer M., Warneke C., Weber R. J., Williams E. J., Sources of particulate matter in the northeastern United States in summer: 1. Direct emissions and secondary formation of organic matter in urban plumes. J. Geophys. Res. 113, D08301 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Decker Z. C. J., Robinson M. A., Barsanti K. C., Bourgeois I., Coggon M. M., DiGangi J. P., Diskin G. S., Flocke F. M., Franchin A., Fredrickson C. D., Gkatzelis G. I., Hall S. R., Halliday H., Holmes C. D., Huey L. G., Lee Y. R., Lindaas J., Middlebrook A. M., Montzka D. D., Moore R., Neuman J. A., Nowak J. B., Palm B. B., Peischl J., Piel F., Rickly P. S., Rollins A. W., Ryerson T. B., Schwantes R. H., Sekimoto K., Thornhill L., Thornton J. A., Tyndall G. S., Ullmann K., Van Rooy P., Veres P. R., Warneke C., Washenfelder R. A., Weinheimer A. J., Wiggins E., Winstead E., Womack C., Brown S. S., Nighttime and daytime dark oxidation chemistry in wildfire plumes: an observation and model analysis of FIREX-AQ aircraft data. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 16293–16317 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu L., Møller K. H., Crounse J. D., Kjaergaard H. G., Wennberg P. O., New insights into the radical chemistry and product distribution in the OH-initiated oxidation of benzene. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 13467–13477 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hodshire A. L., Akherati A., Alvarado M. J., Brown-Steiner B., Jathar S. H., Jimenez J. L., Kreidenweis S. M., Lonsdale C. R., Onasch T. B., Ortega A. M., Pierce J. R., Aging effects on biomass burning aerosol mass and composition: A critical review of field and laboratory studies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 10007–10022 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Singh H. B., Cai C., Kaduwela A., Weinheimer A., Wisthaler A., Interactions of fire emissions and urban pollution over California: Ozone formation and air quality simulations. Atmos. Environ. 56, 45–51 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Womack C. C., McDuffie E. E., Edwards P. M., Bares R., Gouw J. A., Docherty K. S., Dubé W. P., Fibiger D. L., Franchin A., Gilman J. B., Goldberger L., Lee B. H., Lin J. C., Long R., Middlebrook A. M., Millet D. B., Moravek A., Murphy J. G., Quinn P. K., Riedel T. P., Roberts J. M., Thornton J. A., Valin L. C., Veres P. R., Whitehill A. R., Wild R. J., Warneke C., Yuan B., Baasandorj M., Brown S. S., An odd oxygen framework for wintertime ammonium nitrate aerosol pollution in urban areas: NOx and VOC control as mitigation strategies. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 4971–4979 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lakey P. S. J., George I. J., Whalley L. K., Baeza-Romero M. T., Heard D. E., Measurements of the HO2 uptake coefficients onto single component organic aerosols. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 4878–4885 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yokelson R. J., Andreae M. O., Akagi S. K., Pitfalls with the use of enhancement ratios or normalized excess mixing ratios measured in plumes to characterize pollution sources and aging. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 6, 2155–2158 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Atkinson R., Arey J., Atmospheric degradation of volatile organic compounds. Chem. Rev. 103, 4605–4638 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu X., Zhang Y., Huey L. G., Yokelson R. J., Wang Y., Jimenez J. L., Campuzano-Jost P., Beyersdorf A. J., Blake D. R., Choi Y., St. Clair J. M., Crounse J. D., Day D. A., Diskin G. S., Fried A., Hall S. R., Hanisco T. F., King L. E., Meinardi S., Mikoviny T., Palm B. B., Peischl J., Perring A. E., Pollack I. B., Ryerson T. B., Sachse G., Schwarz J. P., Simpson I. J., Tanner D. J., Thornhill K. L., Ullmann K., Weber R. J., Wennberg P. O., Wisthaler A., Wolfe G. M., Ziemba L. D., Agricultural fires in the southeastern U.S. during SEAC4RS: Emissions of trace gases and particles and evolution of ozone, reactive nitrogen, and organic aerosol. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 121, 7383–7414 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Trentmann J., Yokelson R. J., Hobbs P. V., Winterrath T., Christian T. J., Andreae M. O., Mason S. A., An analysis of the chemical processes in the smoke plume from a savanna fire. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 110, D12 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hobbs P. V., Sinha P., Yokelson R. J., Christian T. J., Blake D. R., Gao S., Kirchstetter T. W., Novakov T., Pilewskie P., Evolution of gases and particles from a savanna fire in South Africa. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 108, (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rosen R. S., Wood E. C., Wooldridge P. J., Thornton J. A., Day D. A., Kuster W., Williams E. J., Jobson B. T., Cohen R. C., Observations of total alkyl nitrates during Texas Air Quality Field Study 2000: Implications for O3 and alkyl nitrate photochemistry. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 109, D07303 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Teng A. P., Crounse J. D., Lee L., St. Clair J. M., Cohen R. C., Wennberg P. O., Hydroxy nitrate production in the OH-initiated oxidation of alkenes. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 4297–4316 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wennberg P. O., Bates K. H., Crounse J. D., Dodson L. G., McVay R. C., Mertens L. A., Nguyen T. B., Praske E., Schwantes R. H., Smarte M. D., St Clair J. M., Teng A. P., Zhang X., Seinfeld J. H., Gas-phase reactions of isoprene and its major oxidation products. Chem. Rev. 118, 3337–3390 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nehr S., Bohn B., Wahner A., Prompt HO2 formation following the reaction of OH with aromatic compounds under atmospheric conditions. Chem. A Eur. J. 116, 6015–6026 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yuan Y., Zhao X., Wang S., Wang L., Atmospheric oxidation of furan and methyl-substituted furans initiated by hydroxyl radicals. Chem. A Eur. J. 121, 9306–9319 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhao X., Wang L., Atmospheric oxidation mechanism of furfural initiated by hydroxyl radicals. Chem. A Eur. J. 121, 3247–3253 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Atkinson R., Aschmann S. M., Carter W. P. L., Winer A. M., Pitts J. N., Alkyl nitrate formation from the nitrogen oxide (NOx)-air photooxidations of C2-C8 n-alkanes. J. Phys. Chem. 86, 4563–4569 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Honrath R. E., Owen R. C., Martín M. V., Reid J. S., Lapina K., Fialho P., Dziobak M. P., Kleissl J., Westphal D. L., Regional and hemispheric impacts of anthropogenic and biomass burning emissions on summertime CO and O3 in the North Atlantic lower free troposphere. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 109, D24310 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wofsy S. C., Sachse G. W., Gregory G. L., Blake D. R., Bradshaw J. D., Sandholm S. T., Singh H. B., Barrick J. A., Harriss R. C., Talbot R. W., Shipham M. A., Browell E. V., Jacob D. J., Logan J. A., Atmospheric chemistry in the Arctic and subarctic: Influence of natural fires, industrial emissions, and stratospheric inputs. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 97, 16731 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mauzerall D. L., Jacob D. J., Fan S. M., Bradshaw J. D., Gregory G. L., Sachse G. W., Blake D. R., Origin of tropospheric ozone at remote high northern latitudes in summer. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 101, 4175–4188 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wotawa G., Trainer M., The influence of Canadian forest fires on pollutant concentrations in the United States. Science 288, 324–328 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.DeBell L. J., Talbot R. W., Dibb J. E., Munger J. W., Fischer E. V., Frolking S. E., A major regional air pollution event in the northeastern United States caused by extensive forest fires in Quebec, Canada. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 109, (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bertschi I. T., Jaffe D. A., Long-range transport of ozone, carbon monoxide, and aerosols to the NE Pacific troposphere during the summer of 2003: Observations of smoke plumes from Asian boreal fires. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 110, D05303 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bertschi I. T., Jaffe D. A., Jaeglé L., Price H. U., Dennison J. B., PHOBEA/ITCT 2002 airborne observations of transpacific transport of ozone, CO, volatile organic compounds, and aerosols to the northeast Pacific: Impacts of Asian anthropogenic and Siberian boreal fire emissions. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 109, D23S12 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pfister G. G., Emmons L. K., Hess P. G., Honrath R., Lamarque J.-F., Martin M. V., Owen R. C., Avery M. A., Browell E. V., Holloway J. S., Nedelec P., Purvis R., Ryerson T. B., Sachse G. W., Schlager H., Ozone production from the 2004 North American boreal fires. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 111, D24S07 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 85.Real E., Law K. S., Weinzierl B., Fiebig M., Petzold A., Wild O., Methven J., Arnold S., Stohl A., Huntrieser H., Roiger A., Schlager H., Stewart D., Avery M., Sachse G., Browell E., Ferrare R., Blake D., Processes influencing ozone levels in Alaskan forest fire plumes during long-range transport over the North Atlantic. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 112, (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tanimoto H., Matsumoto K., Uematsu M., Ozone-CO correlations in Siberian wildfire plumes observed at Rishiri Island. SOLA 4, 65–68 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 87.Paris J. D., Stohl A., Nédélec P., Arshinov M. Y., Panchenko M. V., Shmargunov V. P., Law K. S., Belan B. D., Ciais P., Wildfire smoke in the Siberian Arctic in summer: Source characterization and plume evolution from airborne measurements. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 9315–9327 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 88.Singh H. B., Anderson B. E., Brune W. H., Cai C., Cohen R. C., Crawford J. H., Cubison M. J., Czech E. P., Emmons L., Fuelberg H. E., Pollution influences on atmospheric composition and chemistry at high northern latitudes: Boreal and California forest fire emissions. Atmos. Environ. 44, 4553–4564 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 89.Baylon P., Jaffe D. A., Wigder N. L., Gao H., Hee J., Ozone enhancement in western US wildfire plumes at the Mt. Bachelor Observatory: The role of NOx. Atmos. Environ. 109, 297–304 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 90.Teakles A. D., So R., Ainslie B., Nissen R., Schiller C., Vingarzan R., McKendry I., Macdonald A. M., Jaffe D. A., Bertram A. K., Strawbridge K. B., Leaitch W. R., Hanna S., Toom D., Baik J., Huang L., Impacts of the July 2012 Siberian fire plume on air quality in the Pacific Northwest. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 2593–2611 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wiedinmyer C., Neff J. C., Estimates of CO2 from fires in the United States: Implications for carbon management. Carbon Balance Manag. 2, 10 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Val Martin M., Kahn R. A., Tosca M. G., A global analysis of wildfire smoke injection heights derived from space-based multi-angle imaging. Remote Sens. 10, 1609 (2018). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Text

Figs. S1 to S38

Tables S1 to S7

References